Abstract

Objective

This study compared the differences in the rates of maltreatment and homicide deaths between children and young adults with and without a life-limiting condition (LLC) and determined whether this affects the likelihood of receiving specialised palliative care (SPC) services before death.

Design

A nationwide retrospective observational study.

Setting

Taiwan.

Patients

Children and young adults aged 0–25 years with LLCs and maltreatment were identified within the Health and Welfare Data Science Centre by International Classification of Diseases codes. Deaths were included within the Multiple Causes of Death Data if they occurred between 2016 and 2017.

Main outcome measures

Rates of maltreatment, homicide deaths and SPC referrals.

Results

Children and young adults with underlying LLCs experienced a similar rate of maltreatment (2.2 per 10 000 vs 3.1 per 10 000) and had a 68% decrease in the odds of homicide death (19.7% vs 80.3%, OR, 0.32; 95% CI 0.18 to 0.56) than those without such conditions. Among those with LLCs who experienced maltreatment, 14.3% (2 out of 14) had received SPC at least 3 days before death. There was no significant difference in SPC referrals between those who experienced maltreatment and those who did not.

Conclusions

The likelihood of being referred to SPC was low with no significant statistical differences observed between children and young adults with maltreatment and without. These findings suggest a need for integrating SPC and child protection services to ensure human rights are upheld.

Keywords: Palliative Care, Child Abuse, Mortality

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

For children and young adults with life-limiting conditions (LLCs), having special needs that may increase caregiver burdens increases the likelihood of maltreatment.

The integration of a palliative care approach that incorporates a potentially criminal family member is a challenge for healthcare professionals.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

This study found no evidence that children and young adults with LLCs had higher rates of maltreatment or homicide deaths compared with those without.

Those who had experienced maltreatment showed no difference in specialised palliative care referrals.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

Understanding the challenges and barriers faced by professionals initiating palliative care is needed for potentially maltreated children and young adults.

High-quality information on characteristics of maltreated children and young adults with LLCs and quality of death would help improve future aggregation of evidence in this area.

Introduction

Children and young adults with life-limiting conditions (LLCs) may die early.1 Advancements in high medical technology increase their lifespan, yet physical and cognitive decline may happen which impacts their development into adulthood. Heavy caregiving burden falls on their parents, grandparents and siblings leading to physical and psychological distress, worsening communication, marital discord and financial concerns.2 3 Therefore, the WHO suggests that these children and young adults’ healthcare should be integrated with specialised palliative care (SPC), especially at the end of life.4 However, a previous study in Taiwan found that when a patient is suspected to be maltreated or neglected by their family, paediatric healthcare professionals become concerned about initiating SPC because trusting the family becomes difficult and honouring their preferences and goals becomes problematic.4

There are five common types of violence against children in Taiwan: Violence exposure; physical abuse; emotional or psychological abuse; physical, emotional or psychological neglect; and sexual abuse. Exposure to violence is most prevalent in Taiwan.5 Research has shown that certain factors increase the likelihood of maltreatment in children and young adults, particularly those under 4 years old or adolescents. These factors include having uncommon physical features, suffering from intellectual disabilities or neurological disorders, not meeting parental expectations and having special needs that add to the caregiver’s burden.6 Moreover, children and young adults with LLCs or disabilities are at a higher risk for neglect as their increased care requirements can overwhelm caregivers. In some cases, these situations may even lead to homicides or maltreatment-related deaths.7 Frederick et al proposed six main theories to explain the increased risk of maltreatment: Caregiver stress, altruistic intentions, lack of bonding between the caregiver and child, challenging behaviours exhibited by the child, cultural beliefs regarding disabled children and evolutionary factors. Additionally, the deterioration of a child’s illness can make it difficult for caregivers and professionals to identify instances of abuse and maltreatment.8 SPC and withdrawing life-sustaining treatments may not be the priority for abuse cases from paediatric healthcare professionals’ perspective, even if family members request them.4 Therefore, children and young adults with LLCs who potentially experience maltreatment may be the most vulnerable and understudied populations regarding access to SPC.9

We hypothesised that children and young adults with LLCs faced greater risks of maltreatment and homicide death. Additionally, those with LLCs who reported maltreatment had less access to SPC. Thus, this study compared the differences in the proportions of maltreatment and manner of death between children and young adults with and without LLC and determined whether a history of maltreatment influences the likelihood of receiving SPC referrals.

Methods

This population-based observational study used administrative data from the Health and Welfare Data Science Centre (No. H108169) in Taiwan. These data include all inpatient, outpatient and/or emergency care episode records from approximately 93% of hospitals, clinics and long-term care facilities included in the National Health Insurance System in Taiwan.10 These data were linked to Multiple Causes of Death Data (MCDD) if the child died. Moreover, population records from Taiwan’s Department of Household Registration, Ministry of the Interior were used.

Data collection

The data collection was separated into three phases: (1) Phase 1: Comparing the proportion of maltreatment between children and young adults who had documented LLCs in 2015 and those who did not from January 2016 to December 2017, (2) Phase 2: Comparing the manner of death between deceased children and young adults with LLCs and those without LLCs from January 2016 to December 2017, (3) Phase 3: Comparing SPC referral rates for children and young adults aged 1–25 with LLCs and documented maltreatment 1 year before their death against those without documented maltreatment during the period from January 2009 to December 2017.

Phase 1

We identified children and young adults (aged 0–25 years) who were documented as having an LLC in 2015 and who experienced maltreatment between 1 January 2016 and 31 December 2017. This approach ensures that we are considering individuals who still require medical care and are currently suffering from LLCs while facing maltreatment. Cases with documented maltreatment were identified using the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 9th and 10th revision for definite maltreatment codes (995.5 child maltreatment syndrome; T74.12 child physical abuse, confirmed; T74.92 unspecified child maltreatment, confirmed; Y09, assaulted by unspecified means) and probable maltreatment codes (T76.12, child physical abuse, suspected; T76.92, unspecified child maltreatment, suspected; Z04.72, examination and observation following alleged physical abuse).11 LLCs were identified by matching diagnoses based on Fraser’s ICD-10 coding dictionary framework.11 This framework was converted into the ICD-9 using the 2014 list of ICD-9-CM 2001 version developed by the National Cheng Kung University Research Centre for Health Data as ICD-9 was not replaced in use by ICD-10 until 2016 in Taiwan.12 13

Phase 2

Data collected by the MCDD were linked to the administrative data from the Health and Welfare Data Science Centre to compare the manner of deaths between 1 January 2016 and 31 December 2017. Manner of death was categorised into four groups: Natural, unnatural (accidental, suicide and homicide).

Phase 3

To compare SPC referral rates, we included all children and young adults aged 1–25 with a diagnosis of an LLC who died in Taiwan between January 2009 and December 2017. Infants under 1 year of age and those diagnosed only with perinatal diseases were excluded from the study because they occupied the highest proportion of LLC cases but their ICD codes were not eligible for SPC services coverage under Taiwan’s National Health Insurance.13 We compared SPC referral rates for individuals with LLCs who had documented maltreatment 1 year prior to their death with those who had no documented maltreatment during the period from January 2008 to December 2017. We defined SPC as at least one documented inpatient or outpatient SPC service code for at least 3 days before death from 2009 to 2017. These services include family consultations (P5407C, 02020B), shared care (P4401B-03B), inpatient hospice (05601K, 05602A, 05603B, 05604K, 05605A, 05606B) and physician (05312C, 05323C, 05336C, 05337C, 05362C-65C) or nurse visits (05313C, 05314C, 05324C-27C, 05338C-41C, 05366C-73C) to the home or to a long-term care facility for providing SPC.13

Statistical analyses

To compare the proportion of maltreatment (phase 1), proportions of the manner of death between groups (phase 2) and SPC referral rates between groups (phase 3), χ² or t-test was used. Effect estimates were summarised by using an univariable ORs. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences software (SPSS V.25, SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA) was used for the statistical analyses. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in this study.

Results

Proportion of maltreatment

In 2015, among a population of 6 623 926 aged 0–25 in Taiwan, 45 655 individuals (68.9 per 10 000) had underlying records of LLC. Of these 45 655 individuals, 11 (2.4 per 10 000) had a documented maltreatment diagnosis between January 2016 and December 2017. In total, 2039 children and young adults, both with and without an underlying LLC, were identified as having experienced maltreatment based on ICD-10 codes between January 2016 and December 2017. Prevalence of maltreatment in this time frame has no significant difference between individuals with LLCs (2.2 per 10 000; 95% CI 1.2 to 3.9) and without LLCs (3.1 per 10 000; 95% CI 3.0 to 3.3) (p=0.23).

Unnatural deaths

There were 344 275 individual patients who died between 2016 and 2017 registered on the MCDD. Of these, 4957 were children aged 0–25 years with 2036 deaths (41.1%) due to unnatural causes. There were 10.1% (218/2151) of children and young adults with LLCs died of unnatural causes while approximately two-thirds of those without LLCs died due to external factors (1818/2806). The distribution of the manner of unnatural death for patients with LLCs was as follows: Accidental (79.8%), suicide (13.3%) and homicide (6.9%). Individuals with LLCs had a 68% decrease in the odds of dying from homicide (OR, 0.32; 95% CI 0.18 to 0.56) (table 1).

Table 1. Univariable analyses of the associations of life-limiting conditions status and manner of death among children and young adults aged 0–25, 2016–2017.

| Total | Non-LLC | LLC | |||||

| Manner of death | n | n | % | n | % | OR (95% CI) | P value |

| Natural | 2921 | 988 | 33.8 | 1933 | 66.2 | 16.32 (13.90 to19.15) | <0.001 |

| Unnatural | 2036 | 1818 | 89.3 | 218 | 10.7 | ||

| Accidental | 1463 | 1289 | 88.1 | 174 | 11.9 | 0.10 (0.09 to0.12) | <0.001 |

| Suicide | 497 | 468 | 94.2 | 29 | 5.8 | 0.07 (0.05 to0.10) | <0.001 |

| Homicide | 76 | 61 | 80.3 | 15 | 19.7 | 0.32 (0.18 to0.56) | <0.001 |

| Total | 4957 | 2806 | 56.6 | 2151 | 43.4 | ||

Values in bold are statistically significant.

LLClife-limiting condition

SPC access

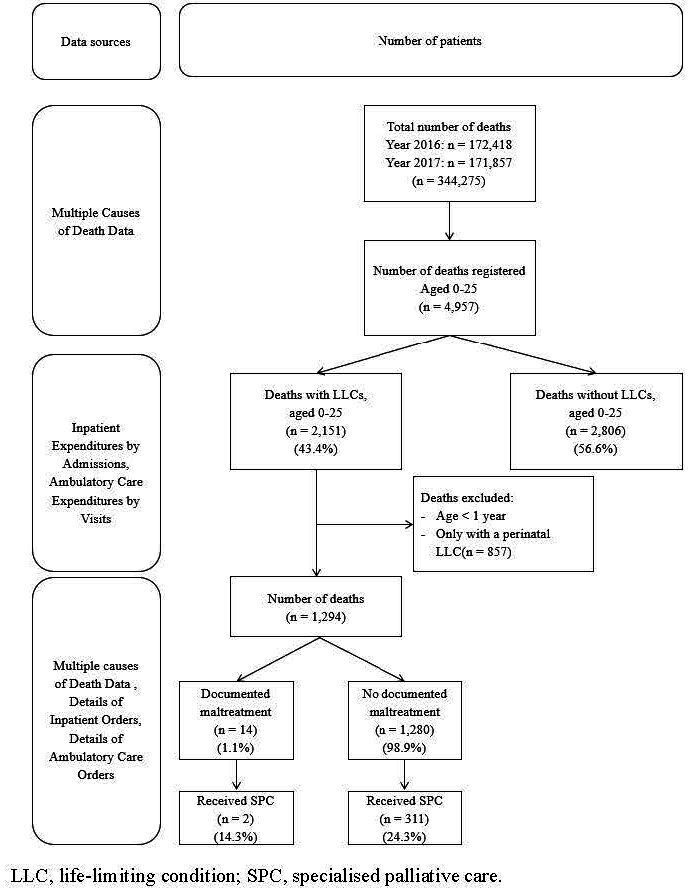

Of the 2151 deceased children and young adults aged 1–25 years who had LLCs, 1294 remained after exclusion criteria were applied (figure 1). Patients with a maltreatment code were accounted for 1.1% (n=14) of deaths (aged 1–25). 14.3% (2 out of 14) of children and young adults with a maltreatment code in the last year of life had received SPC. There was no significant difference in referrals to SPC at least 3 days before death between those with and without a maltreatment code (14.3% vs 24.3%, OR 0.52; 95% CI 0.12 to 2.33, p=0.39).

Figure 1. Study flowchart.

Discussion

Compared with healthy children and young adults, patients who had underlying LLCs had a similar rate of maltreatment (p=0.23) and had a 68% decrease in the odds of dying from homicide (19.7% vs 80.3%, OR, 0.32; 95% CI 0.18 to 0.56) than those without such conditions. There was no significant difference in referrals to SPC at least 3 days before death between those with and without a maltreatment code (OR 0.52; 95% CI 0.12 to 2.33, p=0.39).

Our findings show that the majority of unnatural deaths among children and young adults with LLCs were due to accidents. However, individuals with LLCs had at least a 90% lower likelihood of death from accidents and suicide compared with those without LLCs. The lower rates of accidents and suicides among this population are not unexpected. Many of these individuals rely heavily on their caregivers and tend to be less physically mobile. This dependence may explain the lower incidence of accidents and suicides as both typically require a degree of independence. Moreover, research indicates that many deaths classified as accidental should also be regarded as instances of child maltreatment.14 For example, a parent experiencing burnout drives under the influence of drugs while caring for a child with LLCs. Additionally, studies have shown that children and young adults with LLCs experience higher rates of anxiety and depression compared with those with no long-term conditions.15 However, it is still unclear which specific characteristics of children and young adults with LLCs contribute to their increased risk of suicide. Previous research suggests that children with disabilities who are non-verbal or hearing-impaired are at a higher risk of experiencing neglect.16 One reason for our findings indicating a high rate of natural deaths may be the under-detection of preventable medical-related harm such as severe pressure ulcers and injuries associated with medical devices. These physical injuries may arise from inadequate care or neglect by caregivers which requires additional monitoring, treatment or hospitalisation and can ultimately result in death.17 The deterioration of health conditions in those with LLCs can further complicate the detection of abuse and neglect by caregivers and professionals.8 When death occurs in these cases, these conditions may be classified as ‘natural’ deaths. Future research should employ structured retrospective reviews of medical records to identify cases where deaths were due to such harm.

This study has demonstrated that the referral rates for SPC in children and young adults with an LLC are similarly low compared with those without such conditions. Previous research indicates that the majority of children and young adults either do not receive any SPC or only begin such care within the last 3 days of life.13 Key barriers to the access and use of SPC may be related to lack of awareness by professionals in acute care, perceived stigma and discrimination from professionals and lack of continuity of care because of social disparities. The underlying life-limiting illness in maltreated children and young adults may not reach the terminal stage yet. Misperceptions regarding SPC still exist among healthcare professionals who connect such services with abandoning treatment or as a service reserved for those near death.4 Moreover, the integration of a palliative care approach that incorporates a family member who is potentially criminal is a challenge when considering that the protection of children is paramount. Healthcare professionals may largely focus on implementing strict visitation policies for family members with suspected crimes. A previous study reported that professionals become personally detached from maltreated cases, fearing violence, if they have to testify to domestic violence cases in court.18 Finally, disparities in social support leading to a higher risk of child maltreatment may also create disparities in SPC access.19

The existing empirical evidence on family-centred paediatric palliative care for family-committed maltreated children and young adults is insufficient. Family caregivers may hide their conditions or dispositions from other professionals thus their mental health should also be assessed and managed.20 Early initiation of SPC to support families in finding strength, resilience and love may help prevent maltreatment.21 Furthermore, conducting subgroup analyses is essential to understand the risks of maltreatment and homicide among children and young adults with various LLCs such as those facing inevitable premature death which may involve extended periods of intensive treatment as well as those with irreversible but non-progressive LLCs that result in severe disabilities. Providing respite opportunities can be vital for enabling family members of children and young adults with LLCs to continue their caregiving roles effectively.7 Incorporating a palliative care approach into child protection offers an opportunity for child protection workers and society to expand their perspectives. Rather than viewing palliative care as just passive support for abused children and young adults or seeing family members through a punitive lens, we can embrace a more compassionate and proactive strategy. This shift allows us to provide better support to those in need and encourages healthier family dynamics and community engagement. Further research is needed to understand the challenges and barriers faced by professionals initiating SPC for potentially maltreated children and young adults with LLCs. Exploring reasons for underutilisation or non-access to SPC services and experiences that deter or facilitate such use by maltreated children and young adults is imperative to improve their care. Training healthcare professionals for the early detection of maltreatment in children and young adults with LLC, providing access to counsellors and gaining knowledge of referral agencies are critical in enhancing palliative care competency.

Strengths and limitations

This study has limitations. First, while converting Fraser’s definition of LLCs ICD-10 codes11 to ICD-9 codes, approximately 10% of the diagnoses of LLCs were excluded due to a lack of corresponding ICD-9 codes. Second, identification of maltreatment was dependent solely on hospital diagnoses of maltreatment as coded presumably by hospital staff. This presumably does not include children and young adults whose maltreatment was identified outside the hospital such as through police reports or social services who did not seek formal medical care. Additionally, it did not account for cases identified outside of the research time frame. Consequently, the actual number of children and young adults experiencing maltreatment is likely underestimated. The small sample size limited our ability to account for possible confounding factors related to SPC referrals such as age at death, sex, diagnosis and socioeconomic status.13

Despite limitations, our study has several strengths. First, data sources were from national data sets; therefore, there was a strong backup for mortality tracking, uploaded demographic information and reliable diagnostic information. In addition, a wide variety of diagnostic LLC groups12 was included to generalise the results to children and young adults with both malignant and non-malignant diseases.

Conclusions

This study found no evidence that children and young adults with LLCs experienced higher rates of maltreatment. However, they had lower odds of homicide deaths compared with those without LLCs. The referral rates for SPC among children and young adults with maltreatment were similar to those without. Future prospective research is needed to identify which characteristics of children and young adults with LLCs are associated with a higher risk of accidents and suicides. Additionally, future studies should focus on collecting high-quality data regarding the characteristics of maltreated children and young adults with LLCs as well as the quality of their deaths. These findings indicate a need to integrate SPC services with child protection services to ensure that the human rights of maltreated children and young adults are upheld.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by the National Tainan Junior College of Nursing grant number 11009003. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Tainan Junior College of Nursing.

Data availability free text: Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Ethics approval: The Research Ethics Committee of the National Cheng Kung University Hospital, Taiwan, reviewed and approved the study (No. A-ER-108-217). The requirement for informed consent was waived because only deidentified secondary data was used.

Contributor Information

Shih-Chun Lin, Email: ladylin4u@gmail.com.

Hsin-Yi Chang, Email: zaqwerfan@gmail.com.

Mei-Chih Huang, Email: meay@mail.ncku.edu.tw.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References

- 1.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . United Kingdom: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2017. End of life care for infants, children and young people: quality standard (qs160)https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs160/resources/end-of-life-care-for-infants-children-and-young-people-pdf-75545593722565 Available. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hooghe A, Rosenblatt PC, Vercruysse T, et al. “It’s Hard to Talk When Your Child Has a Life Threatening Illness”: A Qualitative Study of Couples Whose Child Is Diagnosed With Cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2020;37:398–407. doi: 10.1177/1043454220944125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moffatt C, Aubeeluck A, Stasi E, et al. A Study to Explore the Parental Impact and Challenges of Self-Management in Children and Adolescents Suffering with Lymphedema. Lymphat Res Biol. 2019;17:245–52. doi: 10.1089/lrb.2018.0077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin SC, Chang KL, Huang MC. When and how do healthcare professionals introduce specialist palliative care to the families of children with life-threatening conditions in Taiwan? A qualitative study. J Pediatr Nurs. 2022;64:e136–44. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2021.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ministry of Health and Welfare . Taiwan: Ministry of Health and Welfare; 2023. Statistics of children and youths protection.https://dep.mohw.gov.tw/DOPS/lp-1303-105-xCat-cat04.html Available. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . United States: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2022. Child abuse and neglect: risk and protective factors.https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childabuseandneglect/riskprotectivefactors.html Available. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frederick J, Devaney J, Alisic E. Homicides and Maltreatment‐related Deaths of Disabled Children: A Systematic Review. Child Abuse Rev. 2019;28:321–38. doi: 10.1002/car.2574. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manders JE, Stoneman Z. Children with disabilities in the child protective services system: an analog study of investigation and case management. Child Abuse Negl. 2009;33:229–37. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cleveland RW, Ullrich C, Slingsby B, et al. Children at the Intersection of Pediatric Palliative Care and Child Maltreatment: A Vulnerable and Understudied Population. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021;62:91–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Health Insurance Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare . 2017-2018 National Health Insurance in Taiwan Annual Report (Bilingual) Taipei: National Health Insurance, Ministry of Health and Welfare; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hughes Garza H, Piper KE, Barczyk AN, et al. Accuracy of ICD-10-CM coding for physical child abuse in a paediatric level I trauma centre. Inj Prev. 2021;27:i71–4. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2019-043513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fraser LK, Gibson-Smith D, Jarvis S, et al. Estimating the current and future prevalence of life-limiting conditions in children in England. Palliat Med. 2021;35:1641–51. doi: 10.1177/0269216320975308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin SC, Huang MC. Prevalence, trends, and specialized palliative care utilization in Taiwanese children and young adults with life-limiting conditions between 2008 and 2017: a nationwide population-based study. Arch Public Health. 2024;82:99. doi: 10.1186/s13690-024-01315-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palusci VJ, Schnitzer PG, Collier A. Social and demographic characteristics of child maltreatment fatalities among children ages 5-17 years. Child Abuse Negl. 2023;136:106002. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2022.106002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barker MM, Beresford B, Fraser LK. Incidence of anxiety and depression in children and young people with life-limiting conditions. Pediatr Res. 2023;93:2081–90. doi: 10.1038/s41390-022-02370-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Legano LA, Desch LW, Messner SA, et al. Maltreatment of Children With Disabilities. Pediatrics. 2021;147:e2021050920. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-050920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rutberg H, Borgstedt Risberg M, Sjödahl R, et al. Characterisations of adverse events detected in a university hospital: a 4-year study using the Global Trigger Tool method. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e004879. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-004879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miranda RB, Lange S. Domestic violence and social norms in Norway and Brazil: A preliminary, qualitative study of attitudes and practices of health workers and criminal justice professionals. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0243352. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0243352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Putnam-Hornstein E, Prindle JJ, Rebbe R. Community disadvantage, family socioeconomic status, and racial/ethnic differences in maltreatment reporting risk during infancy. Child Abuse Negl. 2022;130:105446. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gear C, Koziol-McLain J, Eppel E. Engaging with Uncertainty and Complexity: A Secondary Analysis of Primary Care Responses to Intimate Partner Violence. Glob Qual Nurs Res. 2021;8:2333393621995164. doi: 10.1177/2333393621995164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goswami J, Baxter J, Schiltz BM, et al. Optimizing resource utilization: palliative care consultations in critically ill pediatric trauma patients. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open. 2023;8:e001143. doi: 10.1136/tsaco-2023-001143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]