Abstract

Rationale:

Corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) plays an integral role in mediating stress responses and anxiety. However, little is known regarding the role of CRF in ethanol consumption, a behavior often associated with stress and anxiety in humans.

Objective:

The present study sought to determine the role of CRF in ethanol consumption, locomotor sensitivity and reward by examining these behaviors in C57BL/6J × 129S mice with a targeted disruption in the gene encoding the CRF prohormone.

Methods:

Male wild-type and CRF-deficient mice were given concurrent access to ethanol and water in both limited and unlimited-access two-bottle choice paradigms. Taste reactivity (saccharin or quinine vs water) was examined in a similar manner under continuous-access conditions. Blood ethanol levels and clearance were measured following limited ethanol access as well as a 4-g/kg i.p. injection of ethanol. Locomotor stimulant effects of ethanol were measured in an open-field testing chamber, and the rewarding effects of ethanol were examined using the conditioned place preference paradigm.

Results:

CRF-deficient mice displayed normal body weight, total fluid intake, taste reactivity and blood ethanol clearance, but consumed approximately twice as much ethanol as wild types in both continuous- and limited-access paradigms. CRF-deficient mice failed to demonstrate a locomotor stimulant effect following acute administration of ethanol (2 g/kg i.p.), and also failed to demonstrate a conditioned place preference to ethanol at 2 g/kg i.p., but did display such a preference at 3 g/kg i.p.

Conclusions:

CRF deficiency may lead to excessive ethanol consumption by reducing sensitivity to the locomotor stimulant and rewarding effects of ethanol.

Keywords: Corticotropin releasing factor, Knockout mouse, Ethanol, Conditioned place preference, Locomotor activity

Introduction

Corticotropin releasing factor (CRF) is a 41-amino acid neuropeptide that is widely distributed throughout the brain and is involved in numerous physiological processes. Hypothalamic CRF systems induce the release of adrenocorticotropin-releasing hormone (ACTH) from anterior pituitary corticotrophs, which in turn enter the circulatory system and increase the release of glucocorticoids from the adrenal gland (Vale et al. 1981; Rivier and Plotsky 1986). CRF systems in the hypothalamus also negatively influence energy balance and food intake (Heinrichs and Richard 1999). Meanwhile, extrahypothalamic (i.e., cortical, limbic, and brainstem) CRF systems are involved in anxiety-like behaviors, arousal, and autonomic responses to stress (Dunn and Berridge 1990; Koob and Heinrichs 1999). Thus, CRF systems in the central nervous system appear to be involved in many biological processes associated with stress, anxiety, and consummatory behaviors.

Alcohol abuse and alcoholism are often associated with stress and stress-related disorders (Brown et al. 1995; Brady and Sonne 1999). In addition, it has been hypothesized that alcoholism may manifest itself as a dysregulated form of ingestive behavior (Samson and Hodge 1996; Orford 2001). Thus, given the involvement of CRF systems in both stress and consummatory-related behaviors, excessive ethanol consumption may involve altered functioning of central CRF systems.

Recently, a mouse model of CRF deficiency has been developed as an important tool for investigating the physiological function of CRF (Muglia et al. 1995; Venihaki and Majzoub 1999). The present study was conducted to determine the effect of deletion of the CRF prohormone gene on patterns of voluntary ethanol consumption patterns and acute behavioral responses to ethanol. We also sought to determine whether CRF-deficient mice would demonstrate an altered conditioned preference for an ethanol-paired environment, a widely used measure of the rewarding effects of abused sub-stances.

Materials and methods

Animals

All mice were bred and genotyped by Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, Me.). The CRF prohormone mutation (Crhtm1Maj) was made in D3 embryonic stem cells derived from 129S2/SvPas mice and injected into blastocysts from C57BL/6J mice (Muglia et al. 1995). Carriers of the null mutation backcrossed to C57BL/6J mice for two generations to yield CRF-deficient mice on an F2 hybrid C57BL/6J × 129S background. CRF-deficient mice (n=45 total) used in the present study were from F5–F8 sibling mating generations.

Since mice heterozygous for the CRF prohormone mutation were mated with homozygous mice, wild-type littermates were not available for use as controls. In addition, Jackson Laboratories does not maintain a 129S2/SvPas mouse colony. Therefore, age-matched F2 hybrids derived from the mating of C57BL/6J and 129S1/SvImJ parentals were used as wild-type controls (stock no. 101045, n=48 total) to provide an approximate genetic background match to the CRF-deficient mice.

Mice were received at 6–8 weeks of age and housed individually in standard Plexiglas cages with food and water available ad libitum throughout all experiments, except where noted. The colony room was maintained on a 12-h:12-h light/dark cycle with lights on at 0600 hours. Mice were between the ages of 2 months and 6 months at the time of testing. Animal care and handling procedures were in accordance with institutional guidelines and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Research Council 1996). All experiments were conducted on experimentally naive mice, except where noted.

Alcohol consumption

Oral alcohol consumption patterns and preference were examined in experimentally naive mice (3–4 months of age) using a two-bottle choice protocol (Hodge et al. 1999; Koenig and Olive 2002). Wild-type and CRF-deficient mice were tested in parallel. Prior to testing, mice were given at least 1 week to acclimatize to individual housing conditions and handling. During this period, water was the only fluid available.

For 23-h, continuous-access procedures, mice were given a choice between concurrently available ethanol (2% v/v) and water. Two-bottle drinking sessions were conducted 23 h per day, 7 days per week. During the course of the exposure period, the ethanol concentration was increased from 2% to 10% (i.e., 2, 4, 8, and 10% v/v) with 4 days of access at each concentration. Each day, mice were weighed and placed in individual holding chambers while the fluids were placed in the home cage. Fluid levels were recorded at the beginning and end of each 23-h fluid-access period. The position (left or right) of each solution was alternated daily to control for side preferences. Ethanol, water, and total fluid intake (ml) and body weight (g) were recorded daily.

For limited-access procedures, experimentally naive mice were fluid restricted for 22 h per day and then allowed 2 h concurrent access to 10% v/v ethanol and water for three consecutive days. Body weights were measured prior to each 2-h access period, and fluid levels were recorded at the beginning and end of this period. During the first 2 days, the animals were allowed to habituate to the limited-access procedures, and data from these sessions were not used for analysis. On the third day, blood was collected from the tail vein and assayed for ethanol content at various time points following the 2-h access period (see below).

Consummatory behavior and taste reactivity

One month after the continuous-access ethanol self-administration procedures, the same mice were tested for saccharin (sweet) and quinine (bitter) intake and preference in an order-balanced experimental design that can detect taste neophobias (Hodge et al. 1999). Saccharin sodium salt (0.033% and 0.066% w/v) and quinine hemisulphate salt (0.015 mM and 0.033 mM) were purchased from Sigma Chemicals (St. Louis, Mo.), dissolved in tap water, and presented for 4 days at each concentration. These solutions are used for their strong tastes, lack of caloric value and absence of confounding pharmacological effects.

Locomotor activity

A separate group of experimentally naive wild-type and CRF-deficient mice were (age 3–4 months) tested for spontaneous and ethanol-induced locomotor activity in Plexiglas chambers (43×43 cm, Med Associates, Lafayette, Ind.). Chambers were located in sound-attenuating cubicles equipped with exhaust fans that masked external noise as well as a 2.8-W house light. Two sets of 16 pulse-modulated infrared photobeams were placed on opposite walls at 2.5-cm centers to record x–y ambulatory movements. Activity chambers were computer interfaced for data sampling at 100-ms resolution. On the first day of testing, animals were allowed a 60-min habituation period prior to the i.p. administration of saline. Animals were then immediately returned to the locomotor testing chambers for an additional 60 min of activity monitoring. This process was repeated on the next day, except that animals received a 2 g/kg i.p. injection of ethanol instead of saline. Horizontal distance traveled (cm) was recorded in 10-min intervals.

Loss of righting reflex

Approximately 1 month following locomotor activity testing, mice (age 5–6 months) were administered ethanol (4 g/kg i.p.) and intermittently placed on their backs and tested for loss of righting reflex. Loss of righting reflex was defined as the inability to complete a righting reflex three times within a 30-s interval. Latency was defined as the time interval between injection and loss of righting reflex, and duration was defined as the time interval between loss and return of the righting reflex.

Blood ethanol concentrations

Approximately 3 weeks following the loss-of-righting reflex assays, blood ethanol concentrations were measured by drawing a 20-μl blood sample from the tail vein into a heparin-coated borosilicate glass capillary at 10, 30, 60, 120, and 180 min following a 4 g/kg i.p. injection of ethanol. Blood plasma was extracted with trichloroacetic acid, and plasma ethanol content was measured using a Sigma Alcohol Diagnostic kit.

For measurement of blood ethanol following limited ethanol access, a 20-μl blood sample from the tail vein was collected at 10, 30, and 60 min following the 2-h, two-bottle access session on the third day of restricted access. Plasma ethanol content was measured as described above.

Conditioned place preference testing

The rewarding effects of ethanol were assessed using a conditioned place preference paradigm (Cunningham and Prather 1992; Cunningham et al. 2000). All mice used in the place preference procedures were experimentally naive and aged 4–6 months. The testing apparatus consisted of two 16.8×12.7×12.7-cm (L × W × H) conditioning compartments with distinct visual and tactile cues (i.e., one with white-colored walls and stainless-steel mesh flooring, the other with black-colored walls and flooring consisting of stainless-steel rods placed on 8-mm centers; Med Associates). The conditioning compartments were connected by a 7.2×12.7×12.7-cm (L × W × H) center compartment with gray walls and solid plastic flooring. Each chamber was equipped with a 2.8-W house light centered above the compartment. The center compartment was equipped with two computer-controlled guillotine doors that provided access to one or both of the conditioning compartments. On the first day of testing (habituation session), all mice were given access to both conditioning compartments for 5 min. Initial preference for one of the two chambers was not recorded, as we have previously observed that experimentally naive mice do not show an initial preference for either conditioning chamber. Over the next 8 days (conditioning sessions), animals received alternating administrations of either saline or ethanol (2 g/kg or 3 g/kg i.p.) and then given access to alternating conditioning compartments for 5 min. A two-day conditioning-free period was allowed after the first 4 days of conditioning. Saline- and ethanol-paired environments were counterbalanced within each group as well as across genotypes. All injections were given immediately prior to the beginning of the conditioning sessions. The pairing of ethanol with either of the conditioning chambers was randomly assigned. On the final (test) day, animals were placed in the center chamber and given access to both compartments for 30 min, and the amount of time spent in the ethanol- and saline-paired compartments was measured electronically by photobeams placed 1.2 cm apart in the conditioning compartments. Locomotor activity (photobeam crosses) was also measured during the test session. Place preference was determined by subtracting the time spent in the saline-paired compartment from the time spent in the ethanol-paired compartment. A conditioned place preference was defined as an animal spending significantly more time in the ethanol-paired compartment than the saline-paired compartment on the test day.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean±SEM and were analyzed using a one- or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a Neuman-Keuls post-hoc test. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant for all tests.

Results

Continuous- and limited-access ethanol consumption

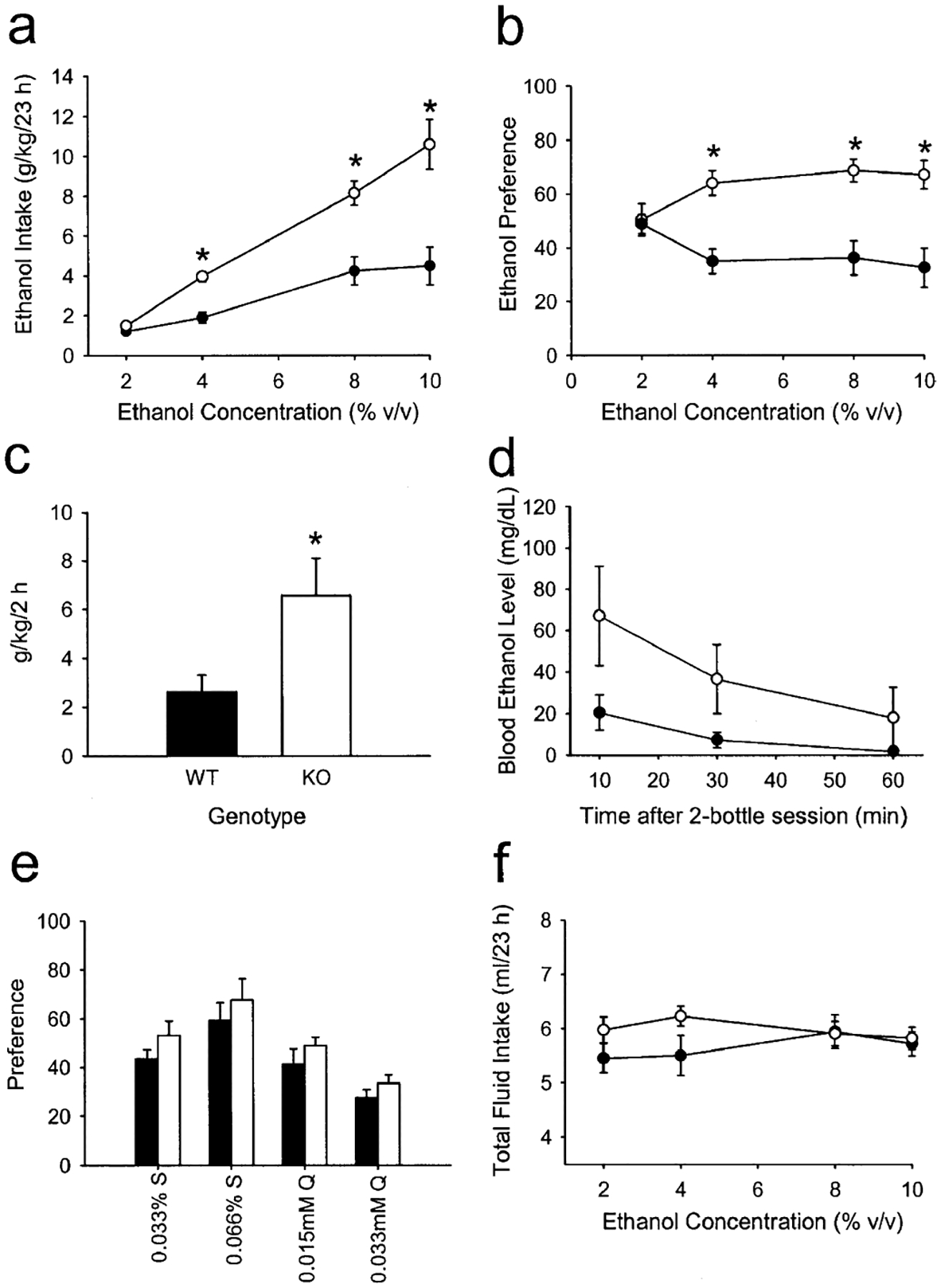

During the daily (23 h) ethanol consumption procedures, there was a significant effect of genotype on ethanol consumption (F1,17=24.74, P<0.001) as well as a significant interaction between genotype and ethanol concentration (F3,51=9.78, P<0.001). As shown in Fig. 1a, CRF-deficient mice demonstrated an average increase of 112% in daily ethanol consumption relative to wild types at the 4, 8, and 10% v/v concentrations. A significant effect of genotype on ethanol preference was also observed (F1,17=20.88, P<0.001), as well as a significant interaction between genotype and ethanol concentration (F3,51=5.92, P=0.002). Ethanol preference was increased by an average of 93% in CRF-deficient mice at the 4, 8, and 10% v/v concentrations (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1a–f.

Increased ethanol intake and preference in wild-type (filled circles and filled bars) and corticotropin releasing factor (CRF)-deficient (open circle and open bars) mice. a Voluntary 23-h ethanol intake (g/kg) plotted as a function of ethanol concentration in a two-bottle, continuous-access paradigm. *P<0.001 vs wild types at the corresponding ethanol concentration. b Ethanol preference (%) relative to total fluid intake, calculated as milliliters ethanol consumed divided by total milliliters consumed ×100. *P<0.001 vs wild types at the corresponding ethanol concentration. c Voluntary ethanol intake during the limited-access (2 h), two-bottle choice paradigm. WT wildtype, KO CRF deficient. *P<0.05 vs wild types. d Blood ethanol levels at various time points following the 2-h, two-bottle, limited-access session. e Preference (%) relative to total fluid intake for saccharin- (S) and quinine- (Q) containing solutions at two different concentrations. f Total fluid intake during the two-bottle, continuous-access procedures. a, b, e, f n=11–12 per group; c, d n=5–6 per group

When access to fluid was restricted to 2 h per day, CRF-deficient mice exhibited significantly greater ethanol intake increase (F1,12=5.28, P<0.05) in ethanol intake during the 2-h access period relative to wild types (Fig. 1c), resulting in a trend toward higher blood ethanol levels, although this comparison just failed to reach statistical significance (F1,11=4.45, P=0.059; Fig. 1d).

Taste reactivity and total fluid intake

Since alterations in ethanol intake and preference can also result from differences in taste reactivity, mice were tested for saccharin (sweet) or quinine (bitter) taste preferences using an order-balanced, two-bottle choice procedure (Hodge et al. 1999). There were no differences between genotypes in average saccharin or quinine preference relative to water intake (P>0.05, Fig. 1e). In addition, mean body weight did not differ between the genotypes during the continuous-access, two-bottle procedures (32.2±1.1 g for CRF-deficient mice, 31.5±0.5 g for wild types, P>0.05), nor did daily fluid intake (P>0.05, Fig. 1f).

Locomotor effects of ethanol

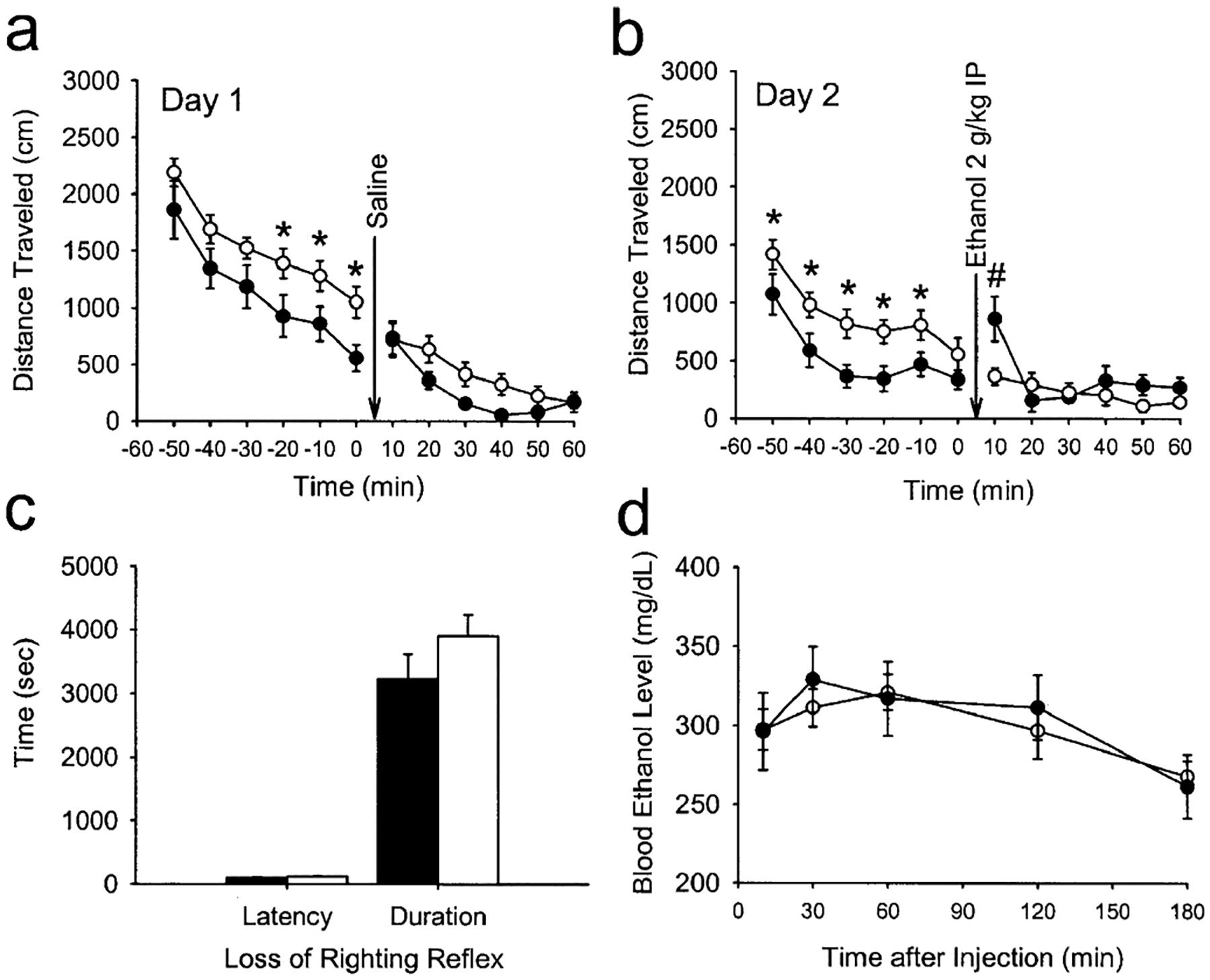

During the first 60 min following placement into the open-field activity chambers, there were significant effects of genotype on basal locomotor activity at various time points relative to wild types on both days of testing (F1,25=5.23, P<0.05; Fig. 2a,b). However, CRF-deficient mice failed to demonstrate an increase in locomotor activity (relative to the time point immediately preceding the injection) following acute administration of ethanol (2 g/kg i.p.), whereas wild-type mice displayed a significant increase in locomotor activity following the same dose of ethanol (Fig. 2b). The acute administration of saline had no effect on locomotor activity in either genotype (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2a–d.

Locomotor activity and acute responses to ethanol in wild-type (filled circles and filled bars) and corticotropin releasing factor (CRF)-deficient mice (open circles and open bars). a Spontaneous locomotor behavior and effects of an acute injection of saline (given at arrow) on the first day of open field testing. *P<0.001 vs wild types at the corresponding time point. b Spontaneous locomotor behavior and effects of an acute injection of ethanol (2 g/kg i.p., given at arrow) on the second day of testing. *P<0.001 vs wild types at the corresponding time point. #P<0.05 compared with pre-injection measurements of wild-type mice at time 0. c Latency to and duration of the loss of righting reflex produced by acute administration of ethanol (4 g/kg i.p.). d Blood ethanol clearance after acute administration of ethanol (4 g/kg i.p.). a, b n=13–14 per group; c, d n=8 per group

Loss of righting reflex and blood ethanol clearance following a high dose of ethanol

When injected with a high (i.e., sedating) dose of ethanol (4 g/kg i.p.), no genotypic differences were observed in either the latency to or duration of the loss-of-righting reflex (P>0.05; Fig. 2c). In addition, when blood ethanol concentrations were measured 10–180 min following a separate injection of ethanol 4 g/kg i.p., no differences between genotypes were observed (Fig. 2d).

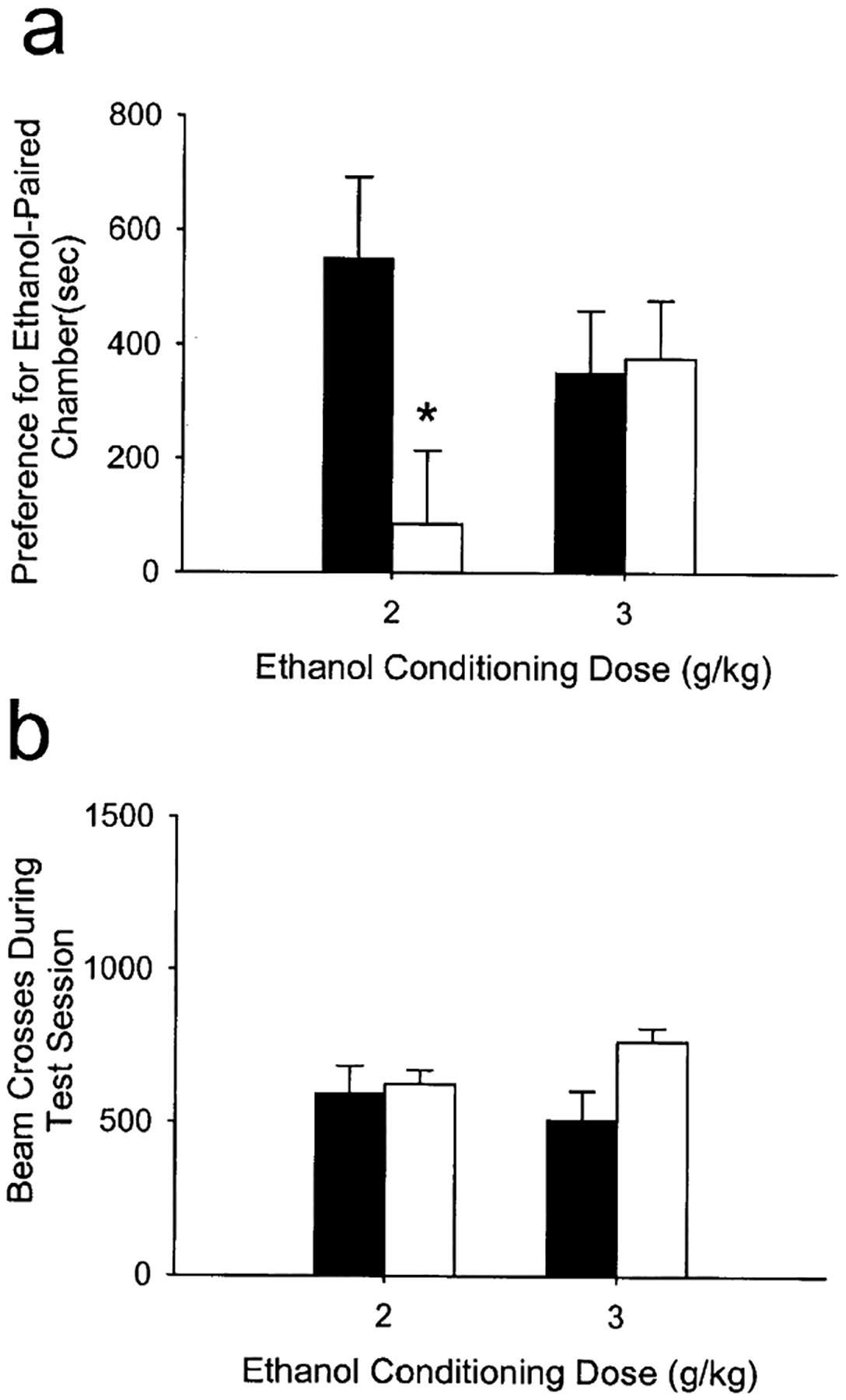

Conditioned place preference

Wild-type mice displayed a significant preference for the ethanol-paired environment when ethanol 2 g/kg was used as the conditioning dose (F1,20=10.00, P<0.01). However, CRF-deficient mice failed to display a significant preference for the ethanol-paired environment at this dose (P>0.05), and overall preference was significantly lower than wild-type mice (F1,20=5.95, P<0.05; Fig. 3a). However, both genotypes displayed a significant preference for the ethanol-paired environment when 3 g/kg ethanol was used as the conditioning dose (Fig. 3a), with no differences observed between genotypes. In addition, locomotor activity (as assessed by the number of photobeam crossings) during the test session did not differ between genotypes (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

a Conditioned place preference for an ethanol-paired environment in wild-type and corticotropin releasing factor (CRF)-deficient mice. Preference was determined as the time spent in the ethanol-paired environment minus the time spent in the saline-paired environment on the test day. n=11–12 per group for 2-g/kg conditioning dose, n=5–6 per group for 3-g/kg conditioning dose. *P<0.01 vs wild types. b Locomotor activity (photobeam breaks) during the 30-min place preference test session

Discussion

In the present study we have shown that mice lacking CRF exhibit increased ethanol consumption in both continuous- and limited-access paradigms. However, one potential limitation of these findings is the fact that the mice used in the present study were from a mixed C57BL/6J × 129S genetic background. Many behavioral phenotypes, including ethanol consumption patterns, of mice with targeted embryonic gene deletions can depend largely on the genetic background of the strain used (Gerlai 1996; Bowers et al. 1999; Phillips et al. 1999). In the present study, CRF-deficient mice consumed approximately the same amount of ethanol as wild-type mice from a pure C57BL/6J background under identical experimental conditions (Koenig and Olive 2002). Although the CRF-deficient mice had the same amount of C57BL/6J genetic background as controls (see Materials and methods), it remains to be determined whether deletion of the CRF prohormone results in increased ethanol intake in mice with more homogeneous genetic backgrounds, particularly those with higher ethanol preferences such as C57BL/6 (Belknap et al. 1993).

Another potential limitation of the present study was the use of non-littermate wild-type mice as controls. Because CRF-deficient mice were generated from heterozygous × homozygous matings at Jackson Laboratories, wild-type littermate controls were unavailable to us. The wild-type controls used in the present study were obtained from a separate C57BL/6J × 129SvImJ colony, and only provided an approximate genetic match to the CRF-deficient mice. Despite these differences, we have previously observed ethanol consumption patterns in wild-type mice on a hybrid C57BL/6J × 129SvJae background (Hodge et al. 1999) that were similar to the C57BL/6J × 129SvImJ wild types used in the present study. Thus, although subtle genetic differences among 129 substrains have been observed (Simpson et al. 1997), it is unlikely that these differences alter ethanol consumption patterns.

Since CRF-deficient mice displayed normal body weight, fluid intake, bitter/sweet taste preferences, and blood ethanol clearance, it is unlikely that observed differences in ethanol intake are a result of altered consummatory behavior, taste reactivity, or ethanol metabolism. At the 10% v/v concentration of ethanol, CRF-deficient mice consumed approximately 10 g/kg per day compared with 4 g/kg per day in wild-type mice. These high levels of daily ethanol intake exhibited by CRF-deficient mice are similar to those obtained during continuous access in other ethanol-preferring strains of mice such as C57BL/6 (Crabbe et al. 1994) and high alcohol preferring (HAP) mice (Grahame et al. 1999), as well as mice lacking neuropeptide Y (Thiele et al. 1998) or the delta opioid receptor (Roberts et al. 2001). In the present study we also demonstrated that CRF-deficient mice display increased ethanol intake during a limited (2 h) access period, and obtain higher blood ethanol levels. The blood ethanol levels obtained by CRF-deficient mice following limited access (67±24 mg/dl) are similar to those obtained by mice lacking the delta opioid receptor (Roberts et al. 2001), as well as those observed following a 1-g/kg i.p. injection in rats (Morse et al. 2000) and are, thus, likely to be pharmacologically relevant.

Our observation that CRF-deficient mice consume more ethanol than wild types suggests an inverse relationship between endogenous CRF levels and ethanol intake. Consistent with this notion, it has been demonstrated that alcohol-preferring (P) rats have lower CRF levels in various brain regions than non-preferring (NP) rats (Ehlers et al. 1992) and that human alcoholics have lower CSF levels of CRF than normal volunteers (Geracioti et al. 1994). In addition, microinjections of CRF into the 3rd ventricle selectively reduce ethanol but not water self-administration in rats (Bell et al. 1998). Taken together, these data suggest that the brain CRF system may be an important inhibitory modulator of voluntary ethanol intake. Further ethanol consumption studies in animals over-expressing CRF are needed, as well as investigations into the specific neural circuits (i.e., hypothalamic versus extrahypothalamic pathways) where CRF may exert modulatory control over ethanol intake.

CRF-deficient mice failed to display a locomotor stimulant response to ethanol at 2 g/kg, a dose commonly used to elicit increased locomotor activity in mice (Frye and Breese 1981; Hodge et al. 1999). Since CRF-deficient mice display normal behavioral responses to stressors (Dunn and Swiergiel 1999; Weninger et al. 1999a), it is unlikely that these effects are a result of an absence of a sensitized response to the stress of the injection procedure. Our data are in agreement with several reports suggesting an inverse relationship between initial ethanol sensitivity (using various behavioral measures) and ethanol consumption patterns in gene knockout mice. For example, mice that carry a null mutation for the 5-HT1B receptor (Crabbe et al. 1996), the epsilon isoform of protein kinase C (Hodge et al. 1999), and neuropeptide Y (Thiele et al. 1998) show a negative correlation between initial acute sensitivity and ethanol intake. Not all studies, however, have demonstrated this inverse relationship. Mice lacking the dopamine D2 receptor are less sensitive to the initial effects of ethanol yet consume less ethanol than wild types (Phillips et al. 1998). Strains of mice that have been selectively bred for differential ethanol sensitivity (Elmer et al. 1990) or withdrawal severity (Harris et al. 1984) also show no consistent relationship between initial ethanol sensitivity and ethanol intake. In addition, it is possible that CRF-deficient mice might display a locomotor stimulant effect to a higher (3 g/kg) dose of ethanol doses, although these doses in wild type mice do not tend to produce robust locomotor stimulant effects (Frye and Breese 1981). Thus, the precise relationship between acute ethanol sensitivity and consumption patterns remains to be clarified.

CRF-deficient mice also failed to display a conditioned place preference to an environment paired with a moderate (2 g/kg) but not a higher (3 g/kg) dose of ethanol. The failure of CRF-deficient mice to demonstrate an ethanol conditioned place preference at the 2-g/kg dose of ethanol is not likely due to the observed increase in basal locomotor activity, as photobeam crosses in the conditioning compartments did not differ across genotypes during the place preference test session. Thus, it appears that the rewarding effects of ethanol are diminished in CRF-deficient mice and that higher doses of ethanol are needed in order to produce its motivational effects in these animals.

Adult CRF-deficient mice have been reported to exhibit lower basal and stress-induced increases in plasma corticosterone levels (Muglia et al. 1995; Jacobson et al. 2000), and it could be argued that lower circulating levels of corticosterone in CRF-deficient mice played a significant role in the increases in ethanol consumption and reduced ethanol reward observed in these mice. However, previous studies have shown that experimental inhibition of glucocorticoid synthesis or secretion does not alter the acquisition or expression of a conditioned place preference to ethanol (Chester and Cunningham 1998) and actually decreases ethanol intake in rodents (Morin and Forger 1982; Fahlke et al. 1994). Based on these data, the lower plasma levels of corticosterone in CRF-deficient mice are not likely to contribute to the increased ethanol consumption or reduced ethanol reward observed in the present study.

Despite the well-established role of CRF in stress, anxiety and consummatory behaviors, mice lacking CRF have been described as having normal anxiety-like behaviors and behavioral responses to stressors (Dunn and Swiergiel 1999; Swiergiel and Dunn 1999; Weninger et al. 1999a, 1999b), providing evidence for a profound degree of plasticity in the neural substrates underlying these behaviors. In addition, CRF-deficient mice have behavioral and neuroendocrine responses to exogenous CRF administration that are indistinguishable from those of wild-type mice (Weninger et al. 1999a; Muglia et al. 2000), arguing against a compensatory up-regulation of CRF receptors in CRF-deficient mice.

However, these studies do raise the possibility that additional CRF-like ligands may be involved in CRF signaling in the brain in the absence of endogenous CRF and may contribute to the altered ethanol consumption and reward behaviors observed in CRF-deficient mice. Recently, three neuropeptides (urocortin I, II and III) have been discovered and characterized as having high affinity for the CRF type-2 receptor. These peptides are found in high concentrations in the hypothalamus and limbic system (Vaughan et al. 1995; Lewis et al. 2001; Reyes et al. 2001; Li et al. 2002) and may be up-regulated in the absence of endogenous CRF (Weninger et al. 2000), thereby influencing the changes in ethanol consumption and reward observed in the present study. Further investigations into the roles of CRF and urocortins in ethanol reward, sensitivity and consumption are clearly needed.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funds provided by the State of California for medical research on alcohol and substance abuse through the University of California at San Francisco, and grant AA11874 to C.W.H. from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. The authors wish to thank Laura Trepanier of Jackson Laboratories for helpful discussions.

Contributor Information

M. Foster Olive, Ernest Gallo Clinic and Research Center, University of California at San Francisco, 5858 Horton Street, Suite 200, Emeryville, CA 94608, USA.

Kristin K. Mehmert, Ernest Gallo Clinic and Research Center, University of California at San Francisco, 5858 Horton Street, Suite 200, Emeryville, CA 94608, USA

Heather N. Koenig, Ernest Gallo Clinic and Research Center, University of California at San Francisco, 5858 Horton Street, Suite 200, Emeryville, CA 94608, USA

Rosana Camarini, Ernest Gallo Clinic and Research Center, University of California at San Francisco, 5858 Horton Street, Suite 200, Emeryville, CA 94608, USA.

Joseph A. Kim, Ernest Gallo Clinic and Research Center, University of California at San Francisco, 5858 Horton Street, Suite 200, Emeryville, CA 94608, USA

Michelle A. Nannini, Ernest Gallo Clinic and Research Center, University of California at San Francisco, 5858 Horton Street, Suite 200, Emeryville, CA 94608, USA

Christine J. Ou, Ernest Gallo Clinic and Research Center, University of California at San Francisco, 5858 Horton Street, Suite 200, Emeryville, CA 94608, USA

Clyde W. Hodge, Department of Psychiatry, Bowles Center for Alcohol Studies, School of Medicine CB #7178, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7178, USA

References

- Belknap JK, Crabbe JC, Young ER (1993) Voluntary consumption of ethanol in 15 inbred mouse strains. Psychopharmacology 112:503–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell SM, Reynolds JG, Thiele TE, Gan J, Figlewicz DP, Woods SC (1998) Effects of third intracerebroventricular injections of corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) on ethanol drinking and food intake. Psychopharmacology 139:128–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers BJ, Owen EH, Collins AC, Abeliovich A, Tonegawa S, Wehner JS (1999) Decreased ethanol sensitivity and tolerance development in g-protein kinase C null mutant mice is dependent on genetic background. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 23:387–397 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady KT, Sonne SC (1999) The role of stress in alcohol use, alcoholism treatment, and relapse. Alcohol Res Health 23:263–271 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA, Vik PW, Patterson TL, Grant I, Schuckit MA (1995) Stress, vulnerability and adult alcohol relapse. J Stud Alcohol 56:538–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chester JA, Cunningham CL (1998) Modulation of corticosterone does not affect the acquisition or expression of ethanol-induced conditioned place preference in DBA/2 J mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 59:67–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabbe JC, Belknap JK, Buck KJ (1994) Genetic animal models of alcohol and drug abuse. Science 264:1715–1723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabbe JC, Phillips TJ, Feller DJ, Hen R, Wenger CD, Lessov CN, Schafer GL (1996) Elevated alcohol consumption in null mutant mice lacking 5-HT1B serotonin receptors. Nat Genet 14:98–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CL, Prather LK (1992) Conditioning trial duration affects ethanol-induced conditioned place preference in mice. Animal Learn Behav 20:187–194 [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CL, Howard MA, Gill SJ, Rubinstein M, Low MJ, Grandy DK (2000) Ethanol-conditioned place preference is reduced in dopamine D2 receptor-deficient mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 67:693–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn AJ, Berridge CW (1990) Physiological and behavioral responses to corticotropin-releasing factor administration: is CRF a mediator of anxiety or stress responses? Brain Res Rev 15:71–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn AJ, Swiergiel AH (1999) Behavioral responses to stress are intact in CRF-deficient mice. Brain Res 845:14–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers CL, Chaplin RI, Wall TL, Lumeng L, Li TK, Owens MJ, Nemeroff CB (1992) Corticotropin releasing factor (CRF): studies in alcohol preferring and non-preferring rats. Psychopharmacology 106:359–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmer GI, Meisch RA, Goldberg SR, George FR (1990) Ethanol self-administration in long sleep and short sleep mice indicates reinforcement is not inversely related to neurosensitivity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 254:1054–1062 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahlke C, Hard E, Thomasson R, Engel JA, Hansen S (1994) Metyrapone-induced suppression of corticosterone synthesis reduces ethanol consumption in high-preferring rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 48:977–981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye GD, Breese GR (1981) An evaluation of the locomotor stimulating action of ethanol in rats and mice. Psychopharmacology 75:372–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geracioti TD Jr, Loosen PT, Ebert MH, Ekhator NN, Burns D, Nicholson WE, Orth DN (1994) Concentrations of corticotropin-releasing hormone, norepinephrine, MHPG, 5-hydroxyin-doleacetic acid, and tryptophan in the cerebrospinal fluid of alcoholic patients: serial sampling studies. Neuroendocrinology 60:635–642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlai R (1996) Gene-targeting studies of mammalian behavior: is it the mutation or the background genotype? Trends Neurosci 19:177–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grahame NJ, Li T-K, Lumeng L (1999) Selective breeding for high and low alcohol preference in mice. Behav Genet 29:47–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris RA, Crabbe JC, McSwigan JD (1984) Relationship of membrane physical properties to alcohol dependence in mice selected for genetic differences in alcohol withdrawal. Life Sci 35:2601–2608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrichs SC, Richard D (1999) The role of corticotropin-releasing factor and urocortin in the modulation of ingestive behavior. Neuropeptides 33:350–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge CW, Mehmert KK, Kelley SP, McMahon T, Haywood A, Olive MF, Wang D, Sanchez-Perez AM, Messing RO (1999) Supersensitivity to allosteric GABAA receptor modulators and alcohol in mice lacking PKCɛ. Nat Neurosci 2:997–1002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson L, Muglia LJ, Weninger SC, Pacak K, Majzoub JA (2000) CRH deficiency impairs but does not block pituitary-adrenal responses to diverse stressors. Neuroendocrinology 71:79–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HN, Olive MF (2002) Ethanol consumption patterns and conditioned place preference in mice lacking preproenkephalin. Neurosci Lett 325:75–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Heinrichs SC (1999) A role for corticotropin releasing factor and urocortin in behavioral responses to stressors. Brain Res 848:141–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis K, Li C, Perrin MH, Blount A, Kunitake K, Donaldson C, Vaughan J, Reyes TM, Gulyas J, Fischer W, Bilezikjian L, Rivier J, Sawchenko PE, Vale WW (2001) Identification of urocortin III, an additional member of the corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) family with high affinity for the CRF2 receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:7570–7575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Vaughan J, Sawchenko PE, Vale WW (2002) Urocortin III-immunoreactive projections in rat brain: partial overlap with sites of type 2 corticotrophin-releasing factor receptor expression. J Neurosci 22:991–1001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin LP, Forger NG (1982) Endocrine control of ethanol intake by rats or hamsters: relative contributions of the ovaries, adrenals and steroids. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 17:529–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse AC, Schulteis G, Holloway FA, Koob GF (2000) Conditioned place aversion to the “hangover” phase of acute ethanol administration in the rat. Alcohol 22:19–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muglia L, Jacobson L, Dikkes P, Majzoub JA (1995) Corticotropin-releasing hormone deficiency reveals major fetal but not adult glucocorticoid need. Nature 373:427–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muglia LJ, Bethin KE, Jacobson L, Vogt SK, Majzoub JA (2000) Pituitary-adrenal axis regulation in CRH-deficient mice. Endocr Res 26:1057–1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orford J (2001) Addiction as excessive appetite. Addiction 96:15–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips TJ, Brown KJ, Burkhart-Kasch S, Wenger CD, Kelly MA, Rubinstein M, Grandy DK, Low MJ (1998) Alcohol preference and sensitivity are markedly reduced in mice lacking dopamine D2 receptors. Nat Neurosci 1:610–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips TJ, Hen R, Crabbe JC (1999) Complications associated with genetic background effects in research using knockout mice. Psychopharmacology 147:5–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes TM, Lewis K, Perrin MH, Kunitake KS, Vaughan J, Arias CA, Hogenesch JB, Gulyas J, Rivier J, Vale WW, Sawchenko PE (2001) Urocortin II: a member of the corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) neuropeptide family that is selectively bound by type 2 CRF receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:2843–2848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivier CL, Plotsky PM (1986) Mediation by corticotropin releasing factor (CRF) of adenohypophysial hormone secretion. Annu Rev Physiol 48:475–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AJ, Gold LH, Polis I, McDonald JS, Filliol D, Kieffer BL, Koob GF (2001) Increased ethanol self-administration in d-opioid receptor knockout mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 25:1249–1256 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson HH, Hodge CW (1996) Neurobehavioral regulation of ethanol intake. In: Deitrich RA, Erwin VG (eds) Pharmacological effects of ethanol on the nervous system. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, pp 203–226 [Google Scholar]

- Simpson EM, Linder CC, Sargent EE, Davisson MT, Mobraaten LE, Sharp JJ (1997) Genetic variation among 129 substrains and its importance for targeted mutagenesis in mice. Nat Genet 16:19–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swiergiel AH, Dunn AJ (1999) CRF-deficient mice respond like wild-type mice to hypophagic stimuli. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 64:59–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiele TE, Marsh DJ, Ste. Marie L, Bernstein IL, Palmiter RD (1998) Ethanol consumption and resistance are inversely related to neuropeptide Y levels. Nature 396:366–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vale W, Spiess J, Rivier C, Rivier J (1981) Characterization of a 41-residue ovine hypothalamic peptide that stimulates secretion of corticotropin and beta-endorphin. Science 213:1394–1397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan J, Donaldson C, Bittencourt J, Perrin MH, Lewis K, Sutton S, Chan R, Turnbull AV, Lovejoy D, Rivier C, Rivier J, Sawchenko PE, Vale W (1995) Urocortin, a mammalian neuropeptide related to fish urotensin I and to corticotropin-releasing factor. Nature 378:287–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venihaki M, Majzoub JA (1999) Animal models of CRH deficiency. Front Neuroendocrinol 20:122–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weninger SC, Dunn AJ, Muglia LJ, Dikkes P, Miczek KA, Swiergiel AH, Berridge CW, Majzoub JA (1999a) Stress-induced behaviors require the corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) receptor, but not CRH. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96:8283–8288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weninger SC, Muglia LJ, Jacobson L, Majzoub JA (1999b) CRH-deficient mice have a normal anorectic response to chronic stress. Regul Peptide 84:69–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weninger SC, Peters LL, Majzoub JA (2000) Urocortin expression in the Edinger-Westphal nucleus is up-regulated by stress and CRH deficiency. Endocrinology 141:256–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]