Abstract

Background

Though social determinants are the primary drivers of health, few studies of people living with HIV focus on non-clinical correlates of insecure and/or fragmented connections with the care system. Our team uses linked clinical and multisector non‐clinical data to study how residential mobility and connection to social services influence the HIV care continuum. We engage a diverse group of individuals living with HIV and other invested community members to guide and inform this research. Our objective is to generate consultant-informed, research-based interventions that are relevant to the community, and to share our engagement approach and findings so that other researchers can do the same.

Methods

Our research team partnered with the Indiana Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute’s Research Jam to develop and implement a human-centered design research plan to engage individuals with experience relevant to our research. We recruited a panel of consultants composed of people living with HIV and/or clinicians and individuals from agencies that provide medical and non-medical services to people living with HIV in Marion County, Indiana. To date, we have used a variety of human-centered design tools and activities to engage individuals during six sessions, with results informing our future engagement and research activities.

Results

Since the inception of the project, 48 consultants have joined the panel. Thirty-five continue to be actively engaged and have participated in one or more of the six sessions conducted to date. Consultants have helped guide and prioritize analyses, aided in identification of data missing from our ecosystem, helped interpret results, provided feedback on future interventions, and co-presented with us at a local health equity conference.

Conclusions

We utilize community engagement to expand the scope of our research and find that the process provides value to both consultants and the research team. Human-centered design enhances this partnership by keeping it person-centered, developing empathy and trust between consultants and researchers, increasing consultant retention, and empowering consultants to collaborate meaningfully with the research team. The use of these methods is essential to conduct relevant, impactful, and sustainable research. We anticipate that these methods will be important for academic and public health researchers wishing to engage with and integrate the ideas of community consultants.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40900-024-00657-0.

Keywords: HIV, Community engagement, Community-based research, Stakeholder engagement, Patient engagement, Community advisory board, Human-centered design, Design thinking

Plain language summary

According to the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, many people living with HIV do not get the care they need to stay healthy. They may face many problems that make it hard for them to access or afford medical services. They may also have barriers such as mental health or substance use disorders, unstable housing, or unreliable access to transportation. We want to understand how these factors influence the health of people living with HIV and find ways to help them overcome these barriers and improve their health. We use information from many sources, including records from health and social service agencies, to measure services received and health outcomes. We also work with a group of people living with HIV and/or who provide support or care to people living with HIV in our community. They help us understand what is important to them, what information we need, what the results mean, and what solutions we should try. To date, there are 48 people in this group. We have hosted six meetings where we shared and discussed our findings and asked for their input. We think that involving people living with HIV and those who seek to serve them is critical to our research. These individuals with lived experience relevant to our research have given us valuable feedback and suggestions that we can use to help guide our research, making it more relevant, useful, and impactful. It can also benefit the people who participate in the community-engaged process, with the consultants learning from each other and from us.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40900-024-00657-0.

Background

Despite significant advances, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) continues to be a major public health issue in the United States, with an estimated 1.2 million residents 13 years of age and older living with HIV [1]. Inconsistent engagement in HIV care contributes to poor outcomes and, at least in part, to an estimated 32,000 new HIV acquisitions in the United States annually [1, 2]. Despite decades of medical and public health programming meant to improve HIV outcomes and decrease disparities, one in four people living with HIV received no HIV care in 2021, and only one-third were virally suppressed [1]. These dismal statistics highlight the need for different approaches.

Most research into correlates of the HIV care continuum has focused on clinical data, leaving much to learn about non-clinical correlates among people living with HIV who have insecure and/or fragmented connections to the continuum of care. Non-clinical correlates of care are structural factors, including health inequities, that many people living with HIV experience. Health inequities are differences in health status caused by social determinants of health (SDOH) [3]. SDOH are conditions into which one is born, grows, or lives (e.g., education, income, race) [3, 4], and they play a critical role in determining health outcomes by creating conditions that either support or hinder health [5]. Understanding and addressing the interaction between SDOH and the risk factors created by them is essential for improving health outcomes among people living with HIV. For example, research has shown that poverty, lack of access to education, stigma and discrimination, and limited access to high-quality healthcare significantly influence the likelihood of HIV acquisition, access to and engagement with HIV care, and the ability to become virally suppressed [4, 6, 7]. Individuals evicted from their homes may lose their social support structure and access to medical care, and then may have poor health outcomes. By incorporating SDOH risk factors, and a consideration of the social services intended to mitigate them, into HIV research, investigators can better understand the barriers to HIV prevention and care, develop more targeted interventions, and improve health outcomes for people living with HIV.

To enhance understanding of the impact of SDOH and social services utilization on HIV outcomes, it is essential to involve community members with a vested interest in the issue being researched. Engaging these individuals as consultants, particularly those living with HIV, healthcare providers, agency representatives, and community leaders, ensures that research is grounded in the realities of those affected by HIV [8–10]. This approach enhances identification of relevant risk factors, the mitigation effects of social services, the development of interventions that are culturally and contextually appropriate, and the implementation of strategies that are more likely to be effective and sustainable. Consultant involvement can also facilitate dissemination and uptake of research findings by ensuring that interventions reach those in need and are integrated into practice and policy [9, 10]. By collaborating with consultants throughout the research process, researchers can gain insights into the complexities of risk factors for poor HIV health outcomes, co-design studies that address pressing needs, and contribute to the development of comprehensive strategies that improve HIV outcomes and promote health equity [9, 10]. Engaging consultants in HIV research is not only a methodological imperative but also an ethical one, ensuring that research contributes to meaningful change for individuals and communities directly affected by HIV. Community engagement is essential for conducting relevant, impactful, and sustainable research [9, 10]. It has been utilized in HIV research since the early 1990s [11, 12] and is a cornerstone of Ending the HIV Epidemic: A Plan for America [13]. Community engagement is also recognized as a beneficial tool for needs assessments and community planning. For example, the Ryan White Part A Indianapolis Transitional Grant Area (TGA) utilizes a Planning Council, designed as a community advisory board, to guide prioritization and allocations of Part A funding in Central Indiana. This design has been demonstrated to be effective. For this reason, it is legislatively mandated for Part A recipients [14].

Human-centered design (HCD) is community-engaged research that is qualitative, person-centered, and collaborative [15, 16]. It offers a framework for developing solutions that are deeply rooted in understanding the needs, behaviors, values, and experiences of community-based research consultants. HCD maximizes consultant retention and generates interventions that are more relevant to the community [15, 16]; it also establishes a reciprocal relationship between researchers and consultants in which positions are well-articulated, needs are clarified, and everyone’s capabilities are utilized to co‐create contextually appropriate projects. Applying HCD principles to non-clinical HIV research allows for development of interventions and strategies that are not only scientifically sound, but also resonate with the lived experiences of people affected by HIV. While people living with HIV have historically been included in programs to reduce the burden of HIV, most HCD research involving HIV has focused on clinical trials rather than on correlates of engagement in the continuum of care. For this reason, many non-clinical researchers lack information necessary to employ HCD for their projects.

We apply HCD methods to engage consultants for a project entitled Getting to Zero. Consultants include people living with HIV, HIV clinicians, and individuals providing non-medical services to people living with HIV in Marion County, Indiana, an area selected for the Ending the HIV Epidemic project due to its HIV prevalence [13]. With a 2022 population of 971.7 thousand [17], the HIV prevalence rate in Marion County is 642 people living with HIV per 100,000 residents [18]. This is nearly three times Indiana’s rate (223 per 100,000), and more than 1.5 times the national rate (388 per 100,000) [18]. Among all people living with HIV in Marion County, only 79% received any HIV medical care during the year; 62% were virally suppressed; and less than half (48%) were retained in care (two quantitative viral load or CD4 counts in a year ≥ 90 days) [19].

Our objectives are to: (1) better understand non-clinical correlates of insecure and/or fragmented connections with the HIV care system; (2) generate consultant-informed, research-based interventions that are more relevant to the community; and (3) share our engagement approach, tools, and findings so that other researchers can do the same. Our approach promises to yield unique insights from the community as we co-design solutions with them that are both innovative and deeply relevant, including interventions that are acceptable, non‐stigmatizing, and appropriately weigh and address ethical and legal considerations that may be identified [16, 20]. As this article will describe, the process has already led us all to appreciate the value and power of community engagement further, which included its co-authorship.

Methods

Consultant panel

We recruited consultants through individuals and organizations with which our team has strong, established partnerships, including infectious disease clinics, HIV/AIDS service organizations, and the Indianapolis TGA’s Ryan White Part A Planning Council. These organizations provided prospective consultants with basic information about our study and told them how to enroll if interested. These agencies were not compensated for their time because of the risk of introducing a conflict of interest. The enrollment process was conducted via an online survey. Survey data was stored on a secure, password protected server behind Indiana University’s firewall. Survey contents were restricted to eligibility questions such as if the respondent was 18-years of age or older; if the respondent lived and/or worked in Marion County; if the respondent was an individual with lived HIV experience or works with individuals living with HIV; and contact information. Indiana University’s recruitment specialists–clinical research coordinators trained in human participant research ethics, confidentiality, and requirements of the U.S. Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–then reached out to describe the consultant panel’s purpose in more detail, including the expected time commitment (three-hour sessions, biannually, for up to five years), and answered questions. For example, some potential consultants were unsure if they would be a good fit for the panel. The recruitment specialists described the type of activities we would be doing and how their specific expertise would be valuable to the project. Risks and benefits of participation were discussed. Recruitment specialists emphasized potential consultants’ critical role as experts in the lived experience of a person living with HIV, a clinician, or an agency representative (not mutually exclusive categories), and that their involvement would bridge that of consultant and collaborator. Prospective consultants were sent a secure link from which they could read the informed consent form and could agree to participate if they wanted to do so. Consultants continue to have the ability and opportunity to reach out to research team members to discuss additional questions or concerns and/or to withdraw from the study at any time. To date, we have recruited a pool of 48 consultants, including: people living with HIV (N = 14), clinical providers serving people living with HIV (N = 11), and representatives of agencies serving people living with HIV (N = 23). Consultants can belong to more than one group (e.g., person living with HIV and representing an agency serving others living with HIV). The role assigned represents the primary role in which each identified. Our study design called for 50 consultants with diversity of group represented, age, race/ethnicity, and gender. Our intention was to mirror the demographic breakdown of people living with HIV in Marion County. We have not yet achieved our goal in terms of total number or diversity. For this reason, we have enrolled all potential consultants who met eligibility criteria.

Black residents bear the burden of HIV in Marion County. While accounting for only 27% of the population, they account for 51% of people living with HIV in the county [17, 18]. However, the consultant panel is only one-third Black (Table 1), slightly more than the overall population of all Black residents. Remaining HIV prevalence in the county is 30% White, 12% Hispanic, and 7% other [17, 18]. Hispanic and individuals of other races/ethnicities are underrepresented among consultants, at only 8% and 4%, respectively, while white consultants are overrepresented, at 48%. Three (6%) consultants did not disclose their race/ethnicity. We do not require disclosure of demographic information beyond confirmation that consultants are at least 18 years old and will not assign a race based on our own perception. By age, the consultant panel roughly mirrors that of Marion County residents living with HIV. Among Marion County residents living with HIV who are 13-years and older, only 4% are 13–24 years old, 87% are 25–64 years old, and 9% are ≥ 65 years old [18]. Comparatively, 77% of consultants are 25–64 years old and 13% are ≥ 65 years old. No consultants listed their age as 18–24 years; however, it is possible that this group is represented because 10% of consultants did not disclose their age. Three of four individuals (76%) living with HIV in Marion County are male, while 22.5% are female and 1.5% are transgender [19]. Only about half (52%) of consultants are male, while 44% are female and 4% are either non-binary or did not disclose their gender (Table 1). While we suspect that transgender representation among consultants exceeds the 1.5% prevalence of this group found in Marion County, most transgender individuals identify as male or female (versus transgender) and that is how we report them.

Table 1.

Getting to zero community engagement panel, by race and gender (N = 48)

| Female | Male | Non-Binary or Undisclosed | Total by Race/Ethnicity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race/Ethnicity | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 7 | 14.6% | 9 | 18.8% | 0 | 0.0% | 16 | 33.3% |

| Non-Hispanic White | 11 | 22.9% | 12 | 25.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 23 | 47.9% |

| Non-Hispanic Other | 1 | 2.1% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 2.1% | 2 | 4.2% |

| Hispanic/Latine | 1 | 2.1% | 3 | 6.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 4 | 8.3% |

| Undisclosed | 1 | 2.1% | 1 | 2.1% | 1 | 2.1% | 3 | 6.3% |

| Total by Gender | 21 | 43.8% | 25 | 52.1% | 2 | 4.2% | 48 | 100.0% |

Recruitment specialists review the consultant panel annually to confirm each individual’s continued interest. We also continue recruitment efforts in case additional individuals wish to join the consultant panel. This increases consultant participation and enables us to maintain good representation of people living with HIV, clinical providers, and agency representatives throughout our ongoing study. Consultants are compensated $150 for completed activities, each of which takes about three hours. The study was reviewed and approved by the Indiana University Institutional Review Board.

Engagement team

Our research team has extensive experience working with individuals seeking and/or receiving clinical care and community consultants to address a variety of research barriers [15, 21–24]. In addition, our work with the consultants is guided by HIV experts. One is a clinician-scientist who has worked in HIV prevention and treatment since 1987. Another has expertise in population-level HIV data and epidemiology. She has also been affiliated with the Marion County Public Health Department’s (MCPHD) Ryan White HIV Services Program (RWHSP) and the Part A Planning Council for 12 years. These relationships facilitate trust-building and guide topics for consultant panel activities. Their experience and relationships contribute to an impactful and sustainable project that is relevant to the needs of the public health community and the people living with HIV who are served by it. Our team also includes an expert in bioethics and law. This allows us to work with consultants to explore the balance between implementing novel, health-maximizing interventions while carefully considering issues such as responsible data stewardship, communication, confidentiality, cultural responsiveness, safety, trust, reciprocity, stigma, and facilitation of care‐seeking behavior.

Our research team partners with the Indiana Clinical and Translational Science Institute’s Research Jam (RJ). RJ is a multi-disciplinary team of eight members: two scientific directors, an associate director of operations, a project coordinator, and four designers with expertise in HCD, health services research, communication, and visual design. This team has experience with research on many topics, including a project to improve peer mentoring to decrease vertical HIV transmission in Kenya. RJ serves as translators to bridge communication between researchers and consultants. RJ uses an HCD approach to engage with consultants to learn their experiences, concerns, and ideas regarding the study. Their engagement helps guide analyses throughout the study (i.e., to identify additional measures and interpret findings), as well as to anticipate and address potential issues with application of the study’s findings.

Engagement activities

Consultants attend virtual or in-person workshop-like sessions, known as Jams, to discuss the project, facilitate identification and exploration of concerns and challenges they face both in pursuit and receipt of services, and to develop, interpret, and disseminate community-informed proposals for alleviating such concerns and challenges. RJ uses the HCD approach and tools (discussed later in this section) to put and keep consultants in the center of discussion, to develop empathy and trust with them, to empower them to externalize ideas and collaborate meaningfully, and to be comfortable with ambiguity in solutions during the development stage [25].To further increase comfort and sharing among consultants, anonymity is maintained, as much as possible, during Jams. Consultants and team members wear name tags with only their first name, and there is no requirement that it be their real name. Last names are never used during Jams, even by our own team members. While some consultants know one another from community activities, RJ discourages disclosure of such information during Jams to limit identification and/or discomfort among consultants. During Jams, all feedback is considered equally, with no concern of whether it comes from a provider or someone living with HIV. With only a couple of exceptions in which consultants have self-disclosed their HIV status to other consultants and the research team, that information is unknown to others.

RJ frames agendas to reflect emerging and evolving findings from our research using an overarching question (e.g., How might we understand reasons for insecure care connections among people living with HIV? How might we mitigate risks associated with migration?). Each session begins with a warmup activity, followed by one to four interactive, generative activities. These range from ‘explore’ activities that are directly in response to findings or ‘create’ activities in which consultants help to develop prototype solutions [26–28].

Originally, we planned to conduct biannual in-person Jams; however, the first Jam was in October of 2020, at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. For this reason, we moved to a virtual setting, with the first four (Oct. 2020-May 2022) Jams conducted via group or individual Zoom calls. To recreate what would have happened in person, RJ mailed consultants Jam kits with materials, worksheets, and supplies for use during each session (Fig. 1). After activities were complete, consultants shared their creations by video and emailed pictures to RJ. To date, we have engaged consultants in six Jams (Table 2), co-presented a panel discussion at a local health equity conference, and co-authored this manuscript.

Fig. 1.

Jam supplies mailed to consultants in advance

Table 2.

Getting to zero Jam Session summaries, Marion County, Indiana: 2020–2023

| Jam | Date | Virtual (Y/N) | Consultants (N) |

Composition | Focus Area | Activities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Oct-20 | Y | 10 | Person living with HIV, 2 | Meeting; building rapport; investigating consultant needs and expectations | Hopes, Fears, and Ideals |

| Clinicians, 2 | ||||||

| Agency, 6 | ||||||

| 2 | May-21 | Y | 10 | Person living with HIV, 3 | Risk and protective factors of a residential move; harmful and advantageous neighborhood characteristics | Collage; Personas (interpreting and creating); Mind maps; |

| Clinicians, 3 | ||||||

| Agency, 4 | ||||||

| 3 | Oct-21 | Y | 5 | Person living with HIV, 3 | Data events useful to prompt alerts useful for case managers to check in with their clients living with HIV | Red Flag Game; Card Sorting Game; Decision Tree |

| Clinicians, 1 | ||||||

| Agency, 1 | ||||||

| 4 | May-22 | Y | 12 | Inactive consultants | Ideas to increase jam session engagement | Interviews |

| 5 | Nov-22 | N | 17 | Person living with HIV, 6 | HIV care engagement; residential mobility; Medicaid; arrest; comorbid mental health diagnosis; spatial relationships | Information-Sharing Stations |

| Clinicians, 1 | ||||||

| Agency, 9 | ||||||

| 6 | Apr-23 | N | 12 | Person living with HIV, 6 | Needs and available resources in the categories: Medical, Mental Health, Transportation, Housing, Social, Financial, and Other | Brainstorming; Resource Mapping |

| Clinicians, 1 | ||||||

| Agency, 5 |

We have utilized several activities to successfully engage and, at one point, to re-engage consultants.

Hopes, fears, and ideals

RJ began with an explore activity to become acquainted, build rapport, and investigate the needs and expectations of consultants. The HCD activity ‘Hopes and Fears’ [29] was modified to reflect ‘Hopes, Fears, and Ideals’. During this activity, consultants were asked to verbally list their hopes, fears, and ideals regarding the consultant panel, allowing us to reflect with them on ways to help it succeed.

Collage

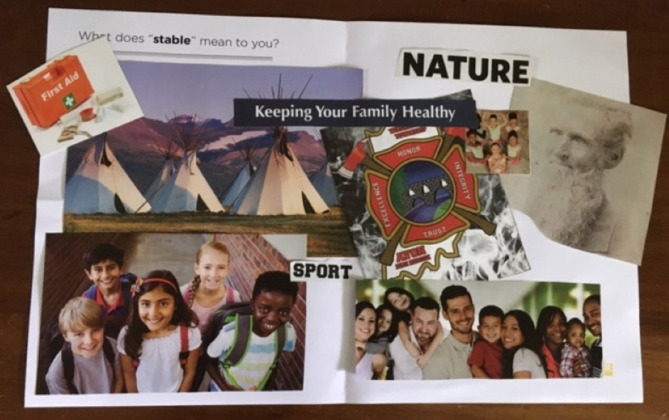

To explore consultants’ perspectives on risk and protective factors associated with a residential move, including harmful and advantageous neighborhood characteristics, RJ utilized three activities. The first was another explore activity called collage [30], during which consultants glued magazine clippings to a piece of paper to answer a prompt (Fig. 2). The prompt used during the Jam was: “What does ‘stable’ mean to you?” Consultants explained their collage to the larger group which led to in-depth discussion.

Fig. 2.

Jam 2 collage example

Personas

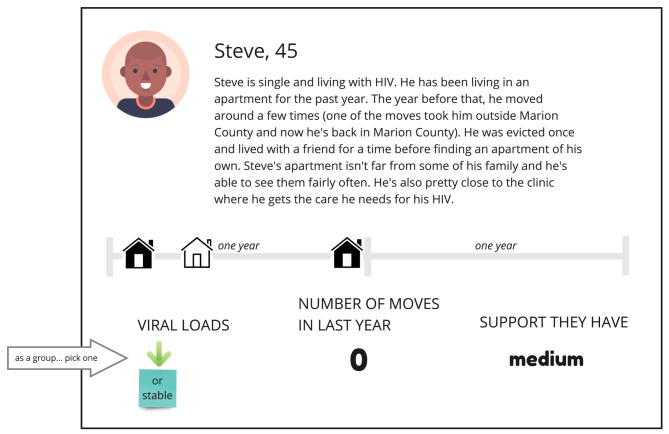

RJ used a create activity called Personas [31], during which they used fictional characters to depict traits and behaviors of the social group being designed for, and in this case, designed with (Fig. 3), to get consultants’ input on where the character could go for aid. RJ then asked consultants to create personas to allow them to tell a story that reflected either a person who is “stable” or a person who is at “high risk” in terms of receiving appropriate HIV care.

Fig. 3.

Jam 2 persona example

Mind maps

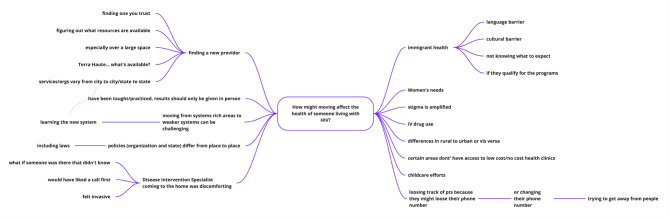

RJ utilized mind mapping, during which a diagram was designed around a central concept using associated ideas brought to life by earlier activities to build upon the ideas posed (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Jam 2 mind map example

Red flag game

RJ used a game called ‘Red Flag’ to identify whether consultants perceived an event as concerning in terms of health outcomes for people living with HIV, and to identify events that might precede HIV-related health getting better or worse. RJ designed the ‘Red Flag’ game to explore when and for what reason(s) consultants would advocate for reaching out to a patient or client based on data sources available to the research team. Consultants assigned red flags to those events they felt might lead to poor health outcomes (Additional file 1. Jam 3 Red Flag Game Example). These items were placed onto virtual cards, and consultants discussed the components of the data on each and were asked to decide whether they would reach out to the patient and to share the reason(s) for their answer.

Card sorting game

RJ organized the Red Flag cards into frequencies, locations (e.g., rural area), and data events (e.g., arrest). Consultants then sorted the cards according to their perceived level of concern and discussed under what circumstances case managers should check in with a client (Additional file 2: Jam 3 Card Sorting Game Example).

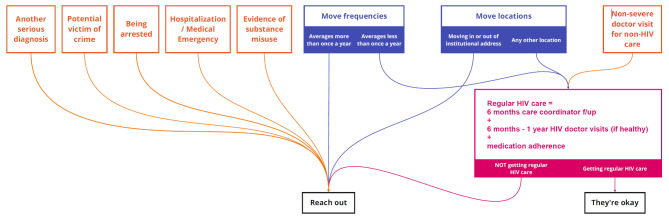

Decision tree

RJ worked with consultants to create a reaching out decision tree (Fig. 5) based on findings from the Red Flag and Card Sorting games.

Fig. 5.

Jam 3 reaching out decision tree

Targeted interviews

Despite nearing our recruitment goals, participation was limited to only 16 consultants through the first four Jams. For this reason, we interviewed a sample (N = 12) of inactive consultants with the aim of understanding why so many had not attended and to hear ideas about improving engagement.

Information-sharing stations

Guided by interview responses and COVID-19 guidelines at that time, we convened our next Jam in person. After an icebreaker (Fig. 6) consultants rotated through five information-sharing stations, each hosted by research team members presenting a different topic (Fig. 7). This format offered consultants an opportunity to learn about our findings and to answer additional research team questions (i.e., What’s missing? How would you use this information?).

Fig. 6.

Jam 5 icebreaker

Fig. 7.

Research team member sharing information at a Jam 5 sharing station

Brainstorming

RJ facilitated a brainstorming activity, prompting consultants to list as many needs of people living with HIV as they could in several categories: medical, mental health, transportation, housing, social, financial, and other. Breakout groups then discussed resources available to address these needs and added ideas to bring resources together or to make them more accessible. They provided context by framing why some resources are more anticipated than others in terms of availability. For example, access to non-medical case management is readily available because Marion County is included in the Ryan White Part A TGA, whereas finding shelter when at risk of homelessness may prove challenging.

Resource mapping

Following the brainstorming activity, consultants participated in an exercise in which they noted local resources directly onto county maps (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Jam 6 resource mapping

Microsoft teams

With the dual purpose of sharing session findings with those not in attendance and building upon previous sessions, RJ made session insights available to consultants online via Microsoft Teams, with opportunities for between-session discussion and discovery among all consultants.

Analysis

RJ assembled and analyzed Jam data using an online collaboration platform called Miro [32]. Data were separated into ‘snippets,’ putting individual thoughts or concepts on separate virtual sticky notes for analysis and synthesis. Separating data into snippets allowed for easy handling during the theming and analysis process [33]. Data were analyzed by 2–3 designers from the RJ team who worked collaboratively as they found themes and patterns with snippets. Ideas were externalized into affinity diagrams [29] and models to more easily discuss findings and to find consensus between designers. When building affinity diagrams, the designers were able to show patterns of, and the relationship between, data (Additional file 3: Affinity Diagram Example). Synthesis took the designers beyond the data, as solutions and recommendations were explored and developed. RJ focused on the abstract concept of ‘what could be’ as opposed to analyzing the abstract concept of ‘what is’ [34]. While moving beyond the data, the designers diverged on solution concepts as they rapidly prototyped how a solution may look. Diverging without constraints brought the designers to ‘blue sky’ solutions, where anything is possible, that were then critiqued and brought back within scope as the designers converged on final solutions and recommendations. RJ continued to use affinity diagrams and modeling during synthesis to develop solutions and recommendations, as well as other rapid prototyping methods, before meeting with the research team to discuss how the information might be used to guide or complement their research. During synthesis, designers sometimes worked individually, then came together for discussion and collaborative development of proposed solutions.

Results

Consultant thoughts about serving on the panel

Consultants expressed hopes of increased collaboration between clinicians, agency representatives, and people living with HIV, and felt that their participation in the project might lead to increased resources for people living with HIV (Table 3).

Table 3.

Hopes, fears, and ideals of the getting to zero community engagement consultant panel

| Hopes | Fears | Ideals |

|---|---|---|

| Collaboration | Delays interfering with progress | Ways of working |

| Shared space, ideas, | COVID and time between | Thinking outside the box |

| expertise | meetings | Better collaboration |

| Increased resources | Who makes up the panel | Panel outcomes |

| More funding | Lack of diversity | Reduce stigma |

| Personal development | ‘Same player’ burn-out | Influence policy |

| Capitalize on increased | Not comfortable sharing thoughts | Increase services |

| awareness due to COVID | Bias affecting the panel | Retain people in HIV care |

| Panel outcomes | Panel outcomes | Improve patient |

| Use time wisely | Results not disseminated quickly | communication |

| Meaningful participation | No new solutions emerge | Connect agencies with |

| Meaningful outcomes |

Panel not heard by researchers Known barriers unchanged |

resources (i.e., funding, guidance with vulnerable populations) |

In fact, their participation did seem to lead to these benefits. Consultants later noted that Jams enabled easy information flow, providing everyone involved with a broad range of information. Multiple consultants asked to photograph Jam output/products and asked us to share meeting notes so that they could use the information for their own agency-related work.

Consultant fears centered on the impact that COVID-19 might have on meaningful collaboration, as well as other delays that might interfere with the consultant panel’s progress. Indeed, virtual versus in-person meetings did limit the participation of many consultants. We averaged 14.5 consultants in attendance during our two in-person Jams (17 and 12, respectively) (Table 2), whereas attendance during our first four Jams averaged only 9.25 consultants. Lack of panel diversity was also a concern, as was a fear of poor panel outcomes (e.g., non-dissemination, barriers unchanged). Consultants offered ideas for working together for better collaboration and ‘outside the box’ thinking, with ideal outcomes to include reduced stigma, policy changes, and increased resources.

When interviewing inactive consultants, they expressed their desire to attend sessions but stated that their schedules made it difficult. They suggested more advanced notice of upcoming Jams, with frequent reminders in a variety of formats (e.g., email, text, and mailers). Interviewees also said that in-person meetings and more clarity about the amount of compensation, as well as when it would be received, might increase motivation to attend. In response, RJ now sends early and frequent Jam reminders that include a clear statement of the compensation to be provided. Consultants’ preferred meeting locations were within proximity to downtown and to bus lines. As such, each of our in-person meetings met these criteria. Importantly, consultants expressed keen interest in learning about our findings to date, including how we responded to their prior feedback. They expressed an appreciation for the research team’s “teachability” and receptiveness to feedback, suggesting that we continue to listen, ask questions, and take their feedback seriously. This feedback, in addition to revised COVID-19 guidelines, led us to host our first in-person Jam, during which the research team shared findings back to consultants and solicited additional feedback.

Consultants conveyed concern that their panel was missing individuals with newly acquired HIV. The concern was that bias may result from having a subgroup of people living with HIV, all of whom were diagnosed five-plus years ago. They suggested that recruiting these newly diagnosed individuals might be difficult due to fear of participation (e.g., being ‘outed’), internal stigma, or being unable to participate due to excess time spent searching for resources.

Concerns also included ‘same player’ burnout, because so many of the consultants participate in other HIV prevention and treatment efforts. Consultants did not offer tangible solutions as to how this can be addressed but, rather, wanted to ensure that we were aware of the issue. These concerns led to discussion of methods our team can use to increase diversity of the consultant panel. Despite our attempts to ensure a diverse panel, in terms of member type and reflection of the demographics of HIV prevalence in the county, consultants reported concern that the panel does not represent the “cultural mentality” held by various people living with HIV. The mentality surrounding poverty was discussed in depth. For example, consultants offered that a person living with HIV in poverty and lacking resources may engage differently than someone who has never, or at least not recently, experienced poverty. Early (childhood) trauma was also suggested as a mechanism behind insecurity and a reluctance to request assistance or to trust others. Racial/ethnic culture, including family and spirituality, were also discussed, as some cultures are less open about discussing physical and/or mental health, or display more stigma toward people living with HIV.

Findings informing HIV research

Mobility/migration

Consultants agreed that people living with HIV seek appropriate services, even moving long distances to access them, but that they often need to live near bus lines to access care. Several factors may push people living with HIV from their homes. These factors may include stigma or violence, financial struggles or eviction, an inability to safely navigate one’s home, or a change in relationship status. These and similar reasons for a move equated to ‘forced mobility,’ which was unanimously seen as a risk factor for poor engagement in HIV care. Consultants agreed that a move might also serve as a protective factor for engagement in care, and that it depends on the reason for moving, financial status, and how well the move was planned. For instance, when a move results in enhanced social support, better access to healthcare, or safer or more stable housing, a move was seen as a protective factor. Regardless of the reason for a move, consultants agreed that researching access to medical and support services when planning a move could prevent lapses in care, and that the amount of time one had lived with HIV was a crucial factor based on established relationships with providers and knowledge of navigating the system of care. Information gleaned from consultants led us to expand some data sources, to explore the acquisition of others, and to more deeply examine the contexts contributing to mobility and migration, including reasons for forced mobility. Specifically, we expanded to statewide Medicaid data, leveraged access to Enhanced HIV/AIDS Reporting System (eHARS) data for the full 10-county Ryan White Part A TGA, are integrating newly acquired Indiana eviction data, and are exploring the use of unemployment data. The newly added data and prioritization of the contexts surrounding a move led to a need to hire a new data analyst. When doing so, we prioritized experience in geographic data and research. We are also considering time elements for future mobility analyses, including time since diagnosis, time spent retained in care prior to the move (a proxy for system navigation experience), and date of last HIV healthcare received (a proxy for last provider contact).

Neighborhood characteristics and spatial relationships

Consultants agreed that crime, residing in a neighborhood where people experience more negative impacts of SDOH (e.g., unemployment, eviction), and lack of access to nutritious food and healthcare were among the harmful characteristics of a neighborhood (Table 4).

Table 4.

Harmful and advantageous neighborhood characteristics identified by the getting to zero consultant panel

| Harmful characteristics | Advantageous characteristics |

|---|---|

| High crime, drug use, domestic violence | Care centers/clinics |

| High number of immigrants | Church pantries |

| High prevalence of mental health issues | Churches |

| Lacking convenient access to healthcare | HIV care |

| Lacking convenient access to nutritious foods | Mental health treatment centers |

| Lacking reliable public transportation | Pantries |

| Low access to childcare | Progressive policies (ex. Reproductive health care) |

| Low car and/or phone ownership | Public transportation |

| Low income/High unemployment | Public transportation for healthcare needs |

| Low or no use of available services | Ryan White supportive services |

| Low provider follow-up | Shopping centers |

| Neighborhoods that are declining | Small malls |

| Neighborhoods with high evictions/mobility | |

| Rural areas |

Advantageous characteristics included access to medical care, social and spiritual support, public transportation, and more. The importance of in-person healthcare was discussed, with distance and poor public transportation cited as reasons that some people living with HIV are not retained in care. The idea of moving to access such services re-emerged. Access to a good social support system was also important for the prevention of isolation. This was a particular concern for older people living with HIV who had a distinct experience with HIV, with concern that some even discontinue medications due to isolation and loneliness. We worked with consultants to identify the physical locations of resources needed by people living with HIV throughout Marion County. Going forward, the research team will integrate neighborhood characteristics and resources into studies of mobility, migration, healthcare utilization, and HIV outcomes.

Social services

Consultants reviewed preliminary findings of Medicaid enrollment continuity and health outcomes among people living with HIV. Consultants agreed that continuous Medicaid enrollment improves access to care but said this often requires assistance with applying and/or recertifying for coverage. Several consultants relayed firsthand experience of coverage gaps caused by a missed application deadline due to illness and/or the convoluted and confusing application process. Consultants encouraged us to consider people with “emergency services only” enrollment as separate from those with another enrollment type, because these individuals are effectively uninsured. This feedback informed the methods we used in recent research on the impact of Medicaid enrollment discontinuity on HIV outcomes [35].

Consultants encouraged us to consider social services data not already utilized by our team. Access to Ryan White services was prioritized, as were programs to assist people living with HIV who are unable to work. As a result, we are exploring options to access Ryan White CAREWare data to evaluate the interaction of Parts A/B/C coverage with other correlates of HIV health outcomes. We are also exploring unemployment data for inclusion in future analyses. Consultants identified housing assistance, food pantries, medical transportation, and help obtaining Americans with Disabilities Act-approved accessibility equipment as important to people living with HIV. For this reason, we are exploring sources of housing assistance data. Food pantries and medical transportation are fragmented in Central Indiana; however, we are considering CAREWare as a source of this data for those enrolled in the Ryan White Part A program that provides these services.

Behavioral health care and/or incarceration

Consultants were surprised to learn that an arrest and comorbid mental health diagnosis led to better health outcomes compared to people living with HIV without an arrest or mental health diagnosis [36]. Their surprise dissipated upon learning that these findings were explained by increased care utilization, likely from accessibility to various correctional system programs (e.g., Behavioral Court). Consultants suggested that incarceration alone can improve HIV outcomes due to increased access to structured care. Mental health and substance use disorders became key points of discussion. There was overwhelming agreement that behavioral health is highly impactful to HIV care outcomes, while also grossly underdiagnosed and therefore under-treated. Some people living with HIV do not seek out behavioral health services, while others seek care from private providers who may not communicate with an individual’s other providers and/or feed data into larger systems (i.e., health information exchange). Consultant suggestions included improving care coordination between HIV medical and behavioral healthcare providers and agency workers. They also suggested evaluation of the timing of behavioral health diagnoses and/or incarceration in relation to HIV diagnosis or care outcomes of interest.

Local resources

Consultants identified needs and available resources in three broad areas. First, important sources of information to help people living with HIV find and research medical and behavioral health needs included libraries, internet and social media, support people and in-person support groups, and churches. Second, physical resources important for people living with HIV were food pantries and delivery services, transportation and housing services, help obtaining Americans with Disabilities Act-approved accessibility equipment, education providers (e.g., academic institutions, back-to-work programs), and organizations providing second-hand items (e.g., clothing, household goods). Third, healthcare resources included medical transportation, help navigating medical needs, access to medical and substance use treatment providers, insurance navigation, telehealth, identifying HIV/AIDS service organizations, and Ryan White services. We plan to integrate these resources and other neighborhood characteristics identified during the mapping exercise into future studies to evaluate their impact on HIV care outcomes.

Case manager alerts

We asked consultants to explore when, and for what reason(s), they would advocate for having case managers reach out to a client based on elements of data used in our research, including electronic health records, Medicaid claims, eHARS, incarceration, and address data. Whether an individual was receiving regular HIV care was the most important consideration; however, because not all HIV providers report to the state’s health information exchange, the use of electronic health records prevents comprehensive provision of alerts. Public health use of eHARS was considered the most straightforward for alerts because it contains a complete record of HIV labs, and because MCPHD’s RWHSP already employs personnel who conduct outreach to people living with HIV who are not retained in care. We learned from consultants who work in the RWHSP, as well as others from that organization, that outreach sometimes occurs months after an individual is no longer retained in care, because of the retrospective method of reporting retention in care that is currently in use. We also learned that some people living with HIV identified for outreach are healthy individuals with undetectable viral loads whose physicians only require them to receive one viral load test per year. This leads to time wasted by outreach personnel. Because one of our research team members has extensive eHARS expertise and a trusted relationship with the RWHSP, and the RWHSP director is one of our active consultants, we were able to engage in an implementation project to leverage eHARS data to proactively generate alerts to identify people living with HIV who do not have a recent undetectable viral load and who are within 30–60 days of falling out care.

Consultants also identified additional data sources that could be useful in alerting case managers to situations of concern, including a mental health or substance use disorder (i.e., Indiana’s Data Assessment Registry for Mental Health & Addiction), data indicating whether HIV medication is taken as prescribed (i.e., CAREWare), and data indicating a forced move (i.e., eviction data).

Dissemination

In November 2023, we collaborated with consultants to develop and co-present our engagement methods at the Analysis to Action Health Equity Symposium [37]. This is a two-day conference designed to communicate to Indiana’s health professionals the best practices in health equity principles and learning health system research. We shared information about why we work with consultants, how we recruited them, our HCD approach, and how consultant input has enriched and changed our research. Three of our consultants attended the symposium and shared their experiences during a panel discussion. The audience was engaged during the session, asking questions of the research team and consultants. Attendees were most interested in the consultants’ experiences and in how we recruited and engaged nearly 50 consultants for a five-year project. This manuscript is an expansion of that presentation. Consultants worked with us to develop the content of, and to co-author, this manuscript, leading to robust discussion of the strengths and limitations of our work together.

Discussion

We utilize HCD and work with a diverse group of consultants impacted by HIV, as well as those who serve them, to better understand non-clinical correlates of insecure and/or fragmented connections with the healthcare system and to generate consultant-informed, research-based interventions that are more relevant to the community.

The consultant panel is comprised of 48 individuals, 35 of whom remain actively engaged after four years. Recruiting a large, engaged panel of consultants for a five-year commitment required much effort, including building and leveraging trusted relationships with infectious disease clinics, HIV/AIDS service organizations, MCPHD, and the TGA’s Ryan White Part A Planning Council. Considerations for how to maintain privacy between and among consultants and researchers is critical. Exploring consultants’ hopes, fears, and ideals about participation was also important for engagement. Their ‘outside the box’ thinking and fear that results might not be disseminated led us to collaborate outside of the planned Jams, leading to a collaborative conference presentation and co-authorship of this manuscript. When participation waned, we turned to inactive consultants to learn why. Their feedback led us to send earlier and more frequent reminders of Jam sessions, to offer more clarity on compensation, to host in-person meetings in a central location near a bus line, and to share findings with them. These changes were successful in increasing and maintaining consultant engagement.

The consultant panel has helped guide and prioritize our analyses, aided in identification of data missing from our ecosystem, highlighted life-altering events that may lead to fragmented connections to care, helped interpret results, and suggested future interventions. This partnership has been effective in meeting each of the aims of our Getting to Zero project, with consultants having made a substantial impact in each area.

Aim 1: Analyze patterns in social services utilization among people living with HIV to understand correlates of poor HIV outcomes. Consultant input informed the methods we used in a recent manuscript on the impact of Medicaid enrollment discontinuity on HIV outcomes [35]. We knew to examine discontinuity by enrollment type and were able to share information on antecedents to discontinuous enrollment based on consultants’ firsthand experiences. This information is important to clinicians and case managers who become aware of difficulties faced by people living with HIV in the confusing and high-stakes process of applying and/or recertifying for this coverage.

Aim 2a: Determine if mobility or migration affects HIV care outcomes. Based on lessons learned from consultants regarding mobility and migration, we expanded Medicaid data to statewide coverage and leveraged our access to eHARS data for the 10-county Ryan White Part A TGA. These changes increased our cohort size, geographic diversity, and the strength of our findings.

Aim 2b: Identify demographic, socioeconomic, life course (e.g., pregnancy, incarceration), and contextual factors associated with HIV outcomes and migration. As a result of consultant feedback on “forced mobility” and neighborhood characteristics that might lead to poor HIV health outcomes, we are exploring use of unemployment and housing assistance data, incorporating statewide eviction data, and integrating neighborhood characteristics (e.g., crime, income, public transit) into our studies. We are also searching out new sources of data to identify causes of mobility and migration and their interaction with other correlates of HIV outcomes. Also based on consultant feedback, our team will include time elements into future mobility analyses, including time since diagnosis, time spent retained in care prior to a move, and date of last HIV health care.

Aim 3: Extend the utility of eHARS for longitudinal research and public health practice. Working with consultants, we have engaged in an implementation project to leverage eHARS data, on MCPHD’s server, to proactively generate alerts to appropriately identify people living with HIV in need of outreach 30–60 days before they are no longer retained in care. Once this program is implemented, we will evaluate and publish outcomes and will make the program freely available to other state and local health departments. Future work will include other ideas gleaned from the consultant panel, such as working with the Indiana Health Information Exchange or with Indiana’s Family and Social Services Administration to generate alerts to case managers based on those data sources.

Perhaps the most profound way in which our research team and projects were impacted was by the shared trust and rapport with consultants, adding faces, firsthand experiences, and context to the data behind our work. This changed the research team’s attitudes toward the value of consultant engagement based on the experiences and relationships formed.

Consultants shared that they also benefitted from participation. Jams enabled easy flow of information between consultants, many of whom left with pictures of Jam products and asked us to share meeting notes so they could use the information for their own agency-related work. RJ made session insights available to consultants online via a Microsoft Teams platform with opportunities for between-session discussion and discovery; however, many of the consultants did not use this platform. When asked why, consultants cited: (1) being too busy to participate off-session; (2) difficulty with technology; and (3) negative experiences with off-session communication in other groups of this type. Consultants living with HIV shared that playing a role on the panel served as a means of social support. One person emotionally shared that, “It felt good to be able to be our authentic selves,” and went on to share the difference he felt as he moved from feeling alone in his diagnosis to participating with others to improve care for people living with HIV.

Our use of the consultant panel was not without limitations and challenges. We were initially funded for this work before the COVID-19 pandemic, the onset of which notably shifted our approach. We did not meet consultants face-to-face until the fall of 2022. Related, at least in part, was an initial hesitancy of some consultants, particularly those living with HIV and/or from historically stigmatized backgrounds, to trust RJ or the research team enough to begin an open conversation about their personal experiences. Our interviews with consultants that did not participate in the virtual sessions did, in fact, confirm their preference to meet in person. Our initial inability to do so reduced our ability to build trusted relationships with consultants and slowed the flow of information.

Jams were also inclusive meetings with all three group types represented. This might have led to hesitancy toward attendance and/or open discussion, particularly among those living with HIV. In future work with consultants, we will host initial Jams with disaggregated groups (i.e., only clinicians, or only people living with HIV), and then slowly build consensus between groups by bringing them together over time, to share and compare their viewpoints in mutually respectful ways, to build greater trust and understanding.

We worked with consultants to identify other panel limitations. Consultants were concerned that the panel was missing individuals newly HIV diagnosed, and suggested placing someone with whom they could relate into a leadership role to increase recruitment and encourage active participation. The local Ryan White Part A Planning Council conducts business in this manner, with experienced leaders mentoring younger up-and-coming leaders, and it works well for them. While this might not work for short-term projects, we will consider this model for future projects in which we will work with consultants for three or more years.

Consultants also expressed that the panel does not represent the racial/ethnic and/or experiential diversity of people living with HIV. We know that consultants do not represent the demographics of HIV in the county and that SDOH and cultural differences are a factor in one’s willingness to ask for assistance. In future projects, we will revise recruitment methods to limit the impact of this weakness. For instance, we can work with minority health agencies, cultural centers, and free medical clinics to identify consultants with more diversity.

Translating findings to practice presents ethical and legal complexities. Expanded data access leads to new opportunities to discover and refine beneficial interventions [38]. For example, our work will alert public health practitioners to individuals at risk of not being retained in care before it happens, and social services data (e.g., eviction, Medicaid enrollment) could, in the future, be integrated into these alerts to make case managers aware of the need for social services navigation and/or wraparound services that can maintain good health among their clients. That being said, public health decisions based on insights identified through integration of ‘big data’ must balance the opportunity to intercede with obligations to minimize potential harms to the autonomy, dignity, trust, privacy, and confidentiality of affected individuals [39]. The consultants’ considerations and engagement were of great importance in this area. Our discussions on the balance of privacy and health led to the Reaching Out Decision Tree (Fig. 5). We utilized this information when implementing the retention in care alert program with MCPHD. Future efforts will focus on expanding that program to the state level. We will also hope to work with the Indiana Department of Health and Indiana Family and Social Services Administration to enable linkage of Medicaid with CAREWare databases so that Medicaid disenrollment alerts can be sent to case managers who can reach out to clients to help them reestablish coverage or confirm other insurance.

Conclusions

Community engagement expanded the scope of our research and provided value to both consultants and research team members. HCD enhanced this partnership by keeping it person-centered, developing empathy and trust, increasing consultant retention, and empowering consultants to externalize ideas and collaborate meaningfully with the research team. We recommend that consultant and community engagement, particularly using HCD methods, is essential to conducting relevant, impactful, and sustainable projects outside the realm of clinically focused research. It can play a key role in any research that uses existing social, programmatic, and clinical data. We encourage readers to contact RJ (https://researchjam.org/) for information regarding the HCD tools described in this manuscript. We anticipate that these methods will be important for academic and public health researchers wishing to engage with, and integrate the ideas of, community consultants.

List of named organizations

| Organization Name | Role |

|---|---|

| Getting to Zero Community Engagement Panel | The consultant panel described in this manuscript |

| Indiana Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute | A statewide partnership among Indiana’s top research universities including Indiana University, Purdue University, and the University of Notre Dame, as well as the Regenstrief Institute. |

| Indiana Department of Health | State health department with jurisdiction across Indiana |

| Indiana Family and Social Services Administration | Oversees Medicaid coverage among Indiana members |

| Indiana University School of Medicine | School of medicine in Indianapolis, Indiana, and the home base of the core research team |

| Marion County Public Health Department | Local health department with jurisdiction across Marion County |

| Medicaid | Medical insurance for some people with limited income and resources |

| Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine | Affiliated university for one of the core research team’s co-investigators |

| Research Jam | Multi-disciplinary team of experts in HCD, health services research, communication, and visual design |

| Ryan White HIV Services Program | The Ryan White program at the Marion County Public Health Department |

| Ryan White Part A Planning Council | Legislatively mandated planning council that oversees prioritization and allocations for Ryan White Part A funding |

| Temple University College of Public Health | Affiliated university for one of the core research team’s co-investigators |

| United States Preventive Services Task Force | An independent, volunteer panel of national experts in disease prevention and evidence-based medicine working to improve the health of people nationwide by making evidence-based recommendations about clinical preventive services. |

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1: Jam 3 Red Flag Game Example (PNG), Example of Red Flag Game output.

Supplementary Material 2: Jam 3 Card Sorting Game Example (PNG), Example of Card Sorting Game output.

Supplementary Material 3: Affinity Diagram Example (PNG), Example section of a project affinity diagram.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express deep appreciation for the Getting to Zero consultant panel for their contributions to this research. We also wish to take this opportunity to address widespread use of the word stakeholder. The word stakeholder does imply a personal stake and is often used with community-engaged research, including by many professional journals, educational institutions, and grantors. The word holds a vastly different historical significance. During colonial times in North America, stakeholders were individuals who drove stakes into the ground to claim land already settled by Indigenous people. For this reason, we call individuals in our community-engaged research consultants. We hope that sharing this information will lead others to consider closely the use of a word that holds negative connotations for Indigenous persons.

Abbreviations

- eHARS

Enhanced HIV/AIDS Reporting System

- HCD

Human-centered design

- HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus

- MCPHD

Marion County Public Health Department

- RJ

Research Jam

- RWHSP

Ryan White HIV Services Program

- SDOH

Social determinants of health

- TGA

Transitional grant area

- USPSTF

United States Preventive Services Task Force

Author contributions

Dr. Wiehe conceptualized the study, provided feedback on research questions and the analysis plan, took part in Jam sessions, helped interpret consultant feedback, and assisted with writing. Ms. Nelson helped conceptualize the study, assisted with consultant recruitment, provided feedback on research questions and the analysis plan, took part in Jam sessions, helped interpret consultant feedback, and drafted the manuscript. Ms. Hawryluk employed the use of human-centered design tools, planned and executed Jam sessions, compiled and interpreted consultant feedback, and assisted with writing. Mr. Miguel Andres assisted with consultant recruitment efforts, took part in Jam sessions, provided feedback on research questions and the analysis plan, helped interpret consultant feedback, and assisted with writing. Drs. Aalsma, Rosenman, and Fortenberry helped conceptualize the study, took part in Jam sessions, provided feedback on research questions and the analysis plan, and helped interpret consultant feedback. Mr. Butler, Ms. Harris, Mr. Moore, and Mr. Scott were consultants who helped develop and co-author the content of this manuscript. Mr. Gharbi took part in Jam sessions and curated data presented back to consultants. Ms. Parks employed the use of human-centered design tools, helped plan and execute Jam sessions, helped compile and interpret consultant feedback, and managed the consultant panel and communication. Mr. Lynch helped plan and execute Jam sessions, produced graphics used during the Jams, and helped to compile and illustrate consultant feedback. Dr. Silverman ensured that the legal and ethical approaches of the study were sound, took part in Jam sessions, provided feedback on research questions and the analysis plan, and assisted with writing. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content, approved the final manuscript as submitted, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (R01AI114435), the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (R01HD098013). The preparation of this article was also supported in part by Research Jam: Indiana Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute’s Patient Engagement Core (PEC) through an award from the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Clinical and Translational Sciences Award (UM1TR004402).

Data availability

We encourage readers to contact Indiana Clinical and Translation Sciences’ Research Jam (https://researchjam.org/) for additional information about the human-centered design tools described in this manuscript. Data generated and/or analyzed using these tools throughout the course of this project are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study received exempt review approval by the Indiana University Institutional Review Board, protocol 2007804959, entitled Getting to Zero People Living with HIV-Participant Engagement. We obtained informed consent from all consultants and contact each annually to ensure their continued interest in participating.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication was obtained from all consultants. That said, consultant images were rendered unidentifiable and there are no details about individuals reported within this manuscript. The only identifiable image (Fig. 7) in the manuscript is that of a co-investigator.

Competing interests

Dr. Sarah Wiehe is a member of the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). This article does not necessarily represent the views and policies of the USPSTF. There are no other competing interests to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Data, Trends US, Statistics, U.S. Rockville, MD:. 2023. https://www.hiv.gov/hiv-basics/overview/data-and-trends/statistics/

- 2.The White House, National, HIV/AIDS Strategy for the United States. 2022–2025. Washington, DC. 2021. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/National-HIV-AIDS-Strategy.pdf

- 3.World Health Organization. Health Inequities and Their Causes 2018 [updated Feb. 22. 2018.] https://www.who.int/news-room/facts-in-pictures/detail/health-inequities-and-their-causes

- 4.World Health Organization. COVID-19 and the Social Determinants of Health and Health Equity: Evidence Brief. Geneva. 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240038387

- 5.Marmot M, Allen JJ. Social Determinants of Health Equity. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(S4):S517–9. 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braveman P, Egerter S, Williams DR. The Social Determinants of Health: coming of Age. Annu Rev Public Health. 2011;32(1):381–98. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yates-Doerr E. Reworking the Social Determinants of Health: responding to Material‐Semiotic Indeterminacy in Public Health interventions. Med Anthropol Q. 2020;34(3):378–97. 10.1111/maq.12586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kindig D, Stoddart G. What is Population Health? Am J Public Health. 2003;93(3):380–3. 10.2105/AJPH.93.3.380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: assessing Partnership approaches to improve Public Health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19(1):173–202. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Viswanathan M, Ammerman A, Eng E, Garlehner G, Lohr KN, Griffith D et al. Community-based Participatory Research: assessing the evidence. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ). 2004(99):1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Weinstein ER, Herrera CM, Serrano LP, Kring EM, Harkness A. Promoting Health Equity in HIV Prevention and Treatment Research: a practical guide to establishing, implementing, and sustaining Community Advisory boards. Ther Adv Infect Dis. 2023(10): 20499361231151508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Namiba A, Orza L, Bewley S, Crone ET, Vazquez M, Welbourn A, Ethical. Strategic and meaningful involvement of women living with HIV starts at the beginning. J Virus Erad. 2016(2):110–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.National Institutes of Health. NIH Bolsters Funding for HIV Implementation Research in High-Burden U.S, Areas. Bethesda MD. Department of Health and Human Services; 2019. https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/nih-bolsters-funding-hiv-implementation-research-high-burden-us-areas

- 14.U.S. Health Resources & Services Administration. Part A: Grants to Eligible Metropolitan and Transitional Areas. https://ryanwhite.hrsa.gov/about/parts-and-initiatives/part-a#:~:text=What’s%20the%20role%20of%20HIV,a%20PC%20if%20one %20exists.

- 15.Sanematsu H, Wiehe S. How do you do? Design Research Methods and the ‘Hows’ of Community Based Participatory Research. In: McTavis L B-MP, editor. Insight 2: Engaging the Health Humanities. Alberta, CA: University of Alberta Department of Art & Design. 2013. https://www.academia.edu/8811657/InSight_2_Engaging_the_Health_ Humanities.

- 16.Sanematsu H, Wiehe S. Learning to look: design in Health Services Research. Touchpoint: J Service Des. 2014;6(2):84–7. [Google Scholar]

- 17.U.S. Census Bureau. Decennial Census. 2020. Table P8. https://data.census.gov/table/DECENNIALDHC2020.P8?g=050XX00US18097

- 18.Emory University Rollins School of Public Health. AIDSVu: Understanding the Current HIV Epidemic. https://map.aidsvu.org/profiles/county/marion-county-in-indiana/overview

- 19.Gumns T. Epidemiology of HIV in the Indianapolis Transitional Grant Area: 2023: Supplemental Document. Available from Marion County Public Health Department, https://ryanwhiteindy.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Epidemiology-of-HIV-in-the-Indianapolis-Transitional-Grant-Area-Supplemental-Info-2023.pdf

- 20.Buchbinder M, Blue C, Rennie S, Juengst E, Brinkley-Rubinstein L, Rosen DL. Practical and ethical concerns in implementing enhanced surveillance methods to improve continuity of HIV Care: qualitative Expert Stakeholder Study. JMIR Public Health Surveillance. 2020;6(3):e19891. 10.2196/19891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tucker Edmonds B, Hoffman S, Lynch D, Jeffries E, Wiehe S, Bauer N et al. Creation of a Decision Support Tool for Expectant Parents Facing Threatened Periviable Delivery: Application of a User-Centered Design Approach. Patient. 2019;12(3):327 – 37. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40271-018-0348-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Hannon TS, Moore CM, Cheng ER, Lynch DO, Yazel-Smith LG, Claxton GE, et al. Codesigned Shared decision-making Diabetes Management Plan Tool for adolescents with type 1 diabetes Mellitus and their parents: Prototype Development and Pilot Test. J Particip Med. 2018;10(2):e8. 10.2196/jopm.9652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hullmann S, Keller S, Lynch D, Jenkins K, Moore C, Cockrum B, et al. Phase I of the detecting and evaluating childhood anxiety and Depression effectively in subspecialties (DECADES) study: development of an Integrated Mental Health Care Model for Pediatric Gastroenterology. J Particip Med. 2018;10(3):e10655. 10.2196/10655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilkinson TA, Hawryluk B, Moore C, Peipert JF, Carroll AE, Wiehe S, et al. Developing a Youth Contraception Navigator Program: a human-centered Design Approach. J Adolesc Health. 2022;71(2):217–25. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2022.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.IDEO.org. The Field Guide to Human-Centered Design: Design Kit. New York, NY. 2015. https://www.designkit.org/resources/1.html

- 26.Quattlebaum P. Guide to Experience Mapping San Francisco and Austin. Adaptive Path. https://medium.com/capitalonedesign/download-our-guide-to-experience-mapping-624ae7dffb54

- 27.Martin B, Hanington B. Universal Methods of Design: 100 Ways to Research Complex Problems, Develop Innovative Ideas, and Design Effective Solutions. Beverly, MA: Rockport Publishers; 2012 Feb 1, 2012. 208 p.

- 28.Sanders EB, Brandt E, Binder T. A Framework for Organizing the Tools and Techniques of Participatory Design. Participatory Design Conference; Sydney, Australia. 2010.

- 29.Yahyaoui S. The Design Thinking Toolkit: 100 + Method Cards to Create Innovative Products: Medium; [updated Apr 13, 2020]. https://uxplanet.org/the-design-thinking-toolbox-100-tools-to-create-innovative-products-50ede1f5e3c1

- 30.Hassi L, Laakso M. Making Sense of Design Thinking. IDBM, Papers IDBM, Program, Aalto University., Miko-Laakso. /publication/274066130_Making_sense_ of_ design_thinking/links/551397ce0cf2e https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Miko-Laakso/publication/274066130_Making_sense_of_design_thinking/links/551397ce0cf2eda0df3026f0/Making-sense-of-design-thinking.pdf?_tp=eyJjb250ZXh0Ijp7ImZpcnN0UGFnZSI6InB1YmxpY2F0aW9uIiwicGFnZSI6InB1YmxpY2F0aW9uIn19.

- 31.Tassi R. Service Design Tools: Communication Methods Supporting Design Processes. 2009. http://www.servicedesigntools.org/

- 32.Miro. What is Miro: Product overview 2024. https://miro.com/product-overview/

- 33.Kolko J. Exposing the magic of design: a practitioner’s guide to the methods and theory of synthesis. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dubberly H, Evenson S. On modeling: the analysis-synthesis Bridge Model. Interactions. 2008;15(2):57–61. 10.1145/1340961.1340976. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wiehe SE, Nelson TL, Aalsma MC, Gharbi S, Miguel Andres U, Fortenberry JD, et al. Healthcare on hold: assessing the effects of Medicaid Enrollment disruption on HIV Care outcomes [In manuscript]. Indianapolis: Indiana University School of Medicine; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wiehe SE, Nelson TL, Aalsma MC, Rosenman MB, Gharbi S, Fortenberry JD. JAIDS. 2023;94(5):403–11. 10.1097/qai.0000000000003296. HIV Care Continuum Among People Living With HIV and History of Arrest and Mental Health Diagnosis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Hawryluk B, Wiehe SE, Nelson TL, Silverman R, Miguel Andres U, Cuevas E. Unlocking Success: Community Engagement for Enhanced HIV Care Outcomes. Health Equity Advancing through Learning Health System Research’s From Analysis to Action Symposium; Nov. 9, 2023; Indianapolis.

- 38.Wiehe SE, Rosenman MB, Chartash D, Lipscomb ER, Nelson TL, Magee LA, et al. eGEMs. 2018;6(1):1–9. 10.5334/egems.236. A Solutions-Based Approach to Building Data-Sharing Partnerships. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Salerno J, Knoppers BM, Lee LM, Hlaing WM, Goodman KW. Ethics, big data and computing in epidemiology and public health. Ann Epidemiol. 2017;27(5):297–301. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2017.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Wiehe SE, Nelson TL, Aalsma MC, Rosenman MB, Gharbi S, Fortenberry JD. JAIDS. 2023;94(5):403–11. 10.1097/qai.0000000000003296. HIV Care Continuum Among People Living With HIV and History of Arrest and Mental Health Diagnosis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wiehe SE, Rosenman MB, Chartash D, Lipscomb ER, Nelson TL, Magee LA, et al. eGEMs. 2018;6(1):1–9. 10.5334/egems.236. A Solutions-Based Approach to Building Data-Sharing Partnerships. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material 1: Jam 3 Red Flag Game Example (PNG), Example of Red Flag Game output.

Supplementary Material 2: Jam 3 Card Sorting Game Example (PNG), Example of Card Sorting Game output.

Supplementary Material 3: Affinity Diagram Example (PNG), Example section of a project affinity diagram.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage readers to contact Indiana Clinical and Translation Sciences’ Research Jam (https://researchjam.org/) for additional information about the human-centered design tools described in this manuscript. Data generated and/or analyzed using these tools throughout the course of this project are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.