Abstract

Introduction

When a childhas suffered, or is at risk of suffering, significant harm from parents or caregivers, the local authority may issue Section 31 (s.31) Care andSupervision proceedings under the Children Act (1989).

Objectives

We compared the healthcare use of infants less than one year old subject to s.31 proceedings in Wales (n = 1, 332), to that of a comparison group of infants not subject to s.31 proceedings (n = 204, 417), between January 2011 and February 2020.

Methods

Population-based e-cohort study utilising data held in the Secure Anonymised Information Linkage (SAIL) Databank. Infants in s.31 proceedings were identified using the Children and Family Court Advisory and Support Service dataset. This was linked to demographic and healthcare datasets, to identify General Practice (GP) visits, emergency department (ED) attendances, and hospital admissions (emergency and elective); before the study end date or the child’s first birthday for the comparison group, orbefore the s.31 application date. Regression analysis calculated event rate ratios [RR] and incidence rate ratios [IRR] for healthcare events, adjusting for widerdeterminants of health (e.g. perinatal factors, maternal mental health, deprivation), and investigated reasons for healthcare use.

Results

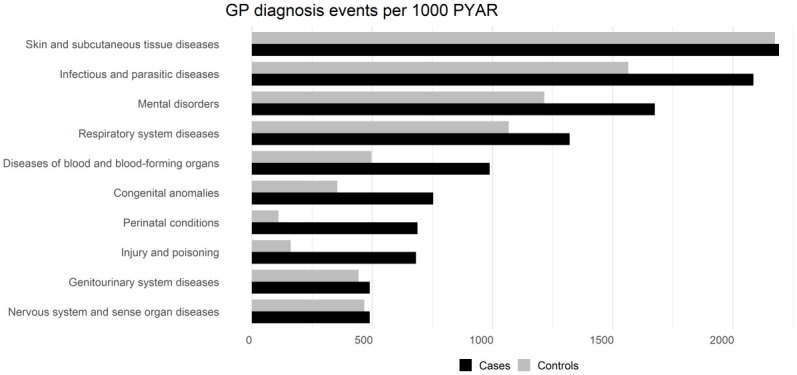

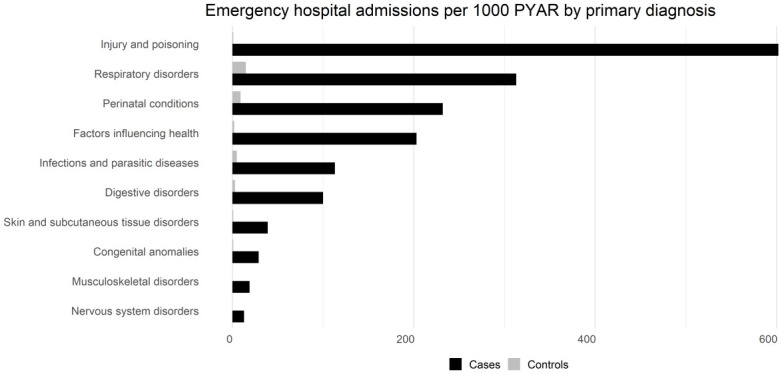

Infants in s.31 proceedings had ahigher number and incidence of healthcare events compared with the comparison group, across all healthcare settings. Differences were greatest for emergency hospital admissions (IRR = 4.03, 95, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 3.53–4.59; RR = 4.60, CI = 3.90–5.41). “Injury and poisoning” was the main reason for emergency admissions amongst infants in s.31 proceedings. For ED presentations, emergency hospital admissions, and GP visits, there were proportionally more events for these infants across all top ten reasons for healthcare.

Conclusions

Findings highlight greater healthcare utilisation for infants involved in s.31 proceedings in Wales, helping to build a better understanding of their needs and vulnerabilities.

Keywords: administrative data, data linkage, care proceedings, health service use

Introduction

When a child is identified as having suffered, or is at risk of suffering, significant harm from a parent or caregiver, the local authority may issue care proceedings under Section 31 (s.31) of the Children Act 1989. Increasing numbers of infants are subject to such family justice care proceedings in Wales and there is, therefore, a rising need for more preventative action to support families involved [1].

Children in care (those ‘looked after’) are reported to have poorer mental and physical health, increased behavioural problems, and increased self-harm and mortality compared to their peers [2–6]. However, most of the evidence to date has reported on small sample sizes or lacked comparison with children who have not been in care. Growth in the use of population-wide linkage of administrative health and social care data provides capacity to derive clearer answers at the population level. Record linkage work in Scotland [7] examining health outcomes in 4 to 18-year-olds reports greater hospitalisation, mortality, and treatment for specific conditions including epilepsy, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, depression, and neurodevelopmental multi-morbidities amongst children looked after compared with their peers. Other large-scale data linkage studies have reported similar disparities between children in care and their peers [8, 9]. However, whether these poorer outcomes are related to characteristics of the care system, or are due to pre-care factors, such as prior ill-health, adverse childhood events, and/or parental vulnerabilities, is unclear.

Recent data linkage work has highlighted health vulnerabilities experienced by mothers and fathers prior to their involvement in s.31 care proceedings in Wales, including higher use of both routine and emergency healthcare when compared to a matched comparison group [10, 11]. Indeed, parents involved in care proceedings were also more likely to experience poor mental health, substance use, and injuries. In turn, household adult mental illness and household substance misuse is associated with greater risk of emergency admissions in children for injuries and external causes [12] as well as broader social care needs [13]. Infants are more at risk of injury given their absolute dependence on caregivers, so where parents are struggling with their own difficulties, they will most likely receive a lower level of supervision – or less consistent supervision – resulting in the possibility of accidents. For adolescents involved in such proceedings, heightened health service utilisation is also reported, with these children experiencing higher rates of hospital admissions and emergency department (ED) attendances for mental health conditions and injuries [14]. However, there is little evidence on the health service use of younger children involved in care proceedings.

Appropriate and effective health and social support could potentially prevent some of the need for care proceedings [15, 16]; however, a joined-up response from health and social care agencies does require greater knowledge about the health and healthcare needs of both the children involved, and their parents. The aim of this population-based study was, therefore, to investigate the health service use of infants younger than one year of age prior to s.31 care proceedings in Wales, compared to a comparison group of infants who were not involved with the family justice system.

Method

Study design and data sources

This was a population-based retrospective cohort study using linked routine data. Data were accessed via the Secure Anonymised Information Linkage (SAIL) Databank [17–19], a trusted research environment that hosts extensive individual-level anonymised health and administrative data for the population of Wales. General practices (GPs) opt-in to providing data to SAIL; currently, SAIL contains primary care data for over 80% of the Welsh population, and the available data are representative of the entire Welsh population with respect to age, sex and deprivation [20]. Data are anonymised using a split-file process, which has been described in detail elsewhere [18–20]. During the anonymisation process, individuals are assigned unique identifier fields, including an Anonymous Linking Field (ALF) and a Residential Anonymous Linking Field (RALF) [19–22] for data linkage at both individual and residential levels, respectively. We used these to link multiple datasets in this study (Table 1). The SAIL Databank was interrogated using DB2 Structured Query Language.

Table 1: Datasets included in this study.

| Dataset | Description |

| The Children and Family Court Advisory and Support Service (Cafcass Cymru) dataset | Cafcass Cymru is a Welsh government organisation that represents children’s best interests in family justice proceedings in Wales. The dataset contains details about family justice cases, legal outcomes, and relevant dates. We included all instances of s.31 care proceedings initiated between the beginning of January 2011 and the end of February 2020. Further details about the Cafcass data are available elsewhere [23, 24] |

| Welsh Demographic Service Dataset (WDSD) | A register containing demographic information about all individuals registered at a Welsh General Practice (GP). Approximately 80% of the Welsh population are included. |

| Welsh Index of Multiple Deprivation 2014 (WIMD 2014) | A dataset containing deprivation scores corresponding to all Lower Super Output Areas (LSOAs; geographic units comprised of around 1,600 individuals) in Wales. |

| National Community Child Health Database (NCCHD) | A register of children born in Wales, containing data collected at birth and information on infant and child health. This dataset also contains a maternal ALF, which we used to link children with their biological mothers. |

| Emergency Department Dataset (EDDS) | A dataset containing information about attendances to emergency departments. |

| Patient Episode Database for Wales (PEDW) | A dataset containing attendance and clinical information for all hospital admissions in Wales, including elective admissions (planned care) and emergency admissions (unplanned urgent care). The episode admission method code defined elective and emergency admissions (codes 11-15, 21-28 respectively). Admission date was used to count the number of infant admissions, and International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) codes were used to investigate reasons for admission [25]. |

| Welsh Longitudinal General Practice (WLGP) dataset | A dataset containing attendance and clinical information for all GP interactions including symptoms, diagnoses, and prescriptions. This dataset was used to calculate GP registration duration, count diagnosis and procedure events, and investigate further reasons for the GP events. |

Study population

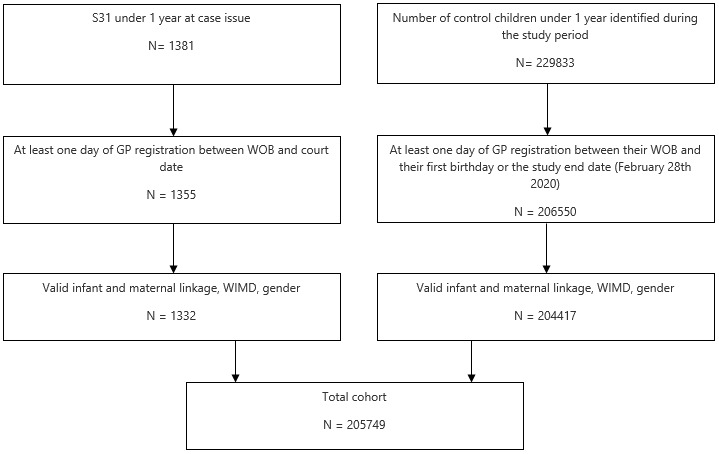

All infants (children younger than 1 year of age before study end date) in the study were born between 1st January 2011 and 28th February 2020. Infants involved in s.31 care proceedings (s.31 infants) in Wales during this period were identified from the Cafcass Cymru dataset. In contrast, the comparison group consisted of infants who were not involved in care proceedings. A child’s NHS number is sometimes changed as a result of court outcomes, for privacy protection reasons. This means that s.31 infants cannot be reliably followed up until their first birthday. Therefore, to be included in the study, s.31 infants had to have at least one day of GP registration between their week of birth (WOB) and the start of proceedings. Comparison group infants needed at least one day of GP registration from birth to the earliest of their first birthday or the study end date, 28th February 2020. This enabled the calculation of person-years at risk (PYAR), to offset the number of events by the number of days the infant was registered with a GP in Wales. Infants’ biological mothers were identified using the maternal ALF, facilitating linkage to the mother’s health records. For valid linkage, individuals were required to have either an exact match on National Health Service (NHS) number or demographics (name, date of birth, gender code, and postcode) or a probabilistic match of 90% or greater [19]. The total cohort comprised 205,749 infants, with 1,332 s.31 infants and 204,417 infants in the comparison group (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Identifying s.31 infants and comparison group in the study period.

Measures

Infant and maternal demographic characteristics

Infant sex was taken from the WDSD. Maternal age at birth was taken from the NCCHD. Lower-layer super output area (LSOA) codes were derived from the WDSD based on the infant’s most recent RALF before their first birthday for the comparison group, or their RALF at the time of court proceedings, for s.31 infants. LSOAs are geographic units designed for the reporting of small area statistics. LSOA codes were used to ascertain deprivation quintiles by linking to the Welsh Index of Multiple Deprivation (WIMD) 2014 dataset [26]. WIMD was coded so that the first quintile was the least deprived and the 5th quintile was the most deprived.

Perinatal health indicators

Perinatal health indicators including gestational age, birth weight, maternal smoking status, total number of births (e.g., twins), and parity (number of previous live births) were obtained from the NCCHD. Apgar score was also used from this dataset. This test is carried out 1 and 5 minutes after birth and checks a baby’s muscle tone, pulse rate, blood flow, and breathing. We used the average of these tests as a single measure in this study.

Maternal mental health and substance use conditions

The maternal ALF was used to link to mothers’ emergency department, hospital inpatient, and GP records to identify the presence of clinical codes indicating GP contacts or hospital admissions for mental health conditions at any time before the child’s birth. Code lists for these were developed and provided by the Adolescent Mental Health Data Platform [27]. Further, maternal health records were analysed for clinical codes indicating substance use indicative of problem, harmful or hazardous use of alcohol and/or illicit drugs at any time in the mother’s history before the child’s birth [28].

Infant healthcare use

Health records (WLGP, EDDS and PEDW) were used to count GP visits, emergency department attendances, and hospital admissions, respectively. Hospital admissions were categorised into emergency or elective. Only events within the GP registration period were counted to ensure residence within Wales, and because the GP registration period was used to calculate PYAR.

Infant health conditions

To investigate the reasons for hospital admissions, ED attendances, and GP events, we used a broad categorisation of health conditions grouped according to the chapter level of the International Classification of Disease version 10 (ICD-10) an accepted official diagnostic classification system [25]. For hospital admissions, all diagnostic codes in primary diagnostic code positions were included. Any primary care diagnoses codes within the GP Read classification system were included, with codes mapped to approximations of ICD-10 chapters (Supplementary Tabe 1). Read codes are a hierarchical terminology system that encode clinical, diagnostic and therapeutic patient information and enable data entry of patient care information following a primary care consultation. We further grouped the broad categories ‘head injury’, ‘wound’ and ‘fracture’ into an overarching ‘injury and poisoning’ category. In addition, ‘respiratory conditions’ and ‘respiratory disorders’ were grouped together.

Data analysis

Key outcomes were the number of ED attendances, elective and emergency hospital admissions, and GP attendances for infants, from the GP registration start date to the court date for s.31 infants, and either the study end date or the child’s first birthday for the comparison group. An infant’s likelihood of experiencing a healthcare event that appears in their health records is dependent on the duration the infant is present in the data. Therefore, models were adjusted for PYAR. This was calculated as the total GP registration duration in the study period, which adjusts for instances where the infant could have moved into or out of Wales.

Negative binomial regression was used to analyse the data. This technique is used for modelling count variables and does not assume equally dispersed data, so is suitable for real world data. Models sequentially included group (s.31 infant or comparison infant), maternal mental health and substance use, demographic variables (sex, WIMD), and perinatal health indicators (gestational age, birth weight, Apgar score, total birth number, smoking status, and parity). Rate ratios (RR) for incidence (IRR) and events were calculated. Incidence RR counts new events, whereas the event RR looks at all events in a period; birth to court case for s.31 infants or first birthday/study end date for the comparison group. These models were offset by PYAR. The reasons for hospital admissions, ED attendances, and GP events were also investigated and described. Differences in demographic characteristics were calculated using t-tests for parametric continuous variables, Wilcoxon tests for non-parametric continuous variables, and chi-square tests of independence for categorical variables. Data analysis was conducted in R version 1.4.3 [29].

Results

Cohort

Overall, there were 205,749 children included in the analyses. Of these, 1,332 were s.31 infants and 204,417 were in the comparison group (Table 2). There were slightly more males than females in the s.31 infants than in the comparison group (53% vs. 51%). Compared to the comparison group, a greater proportion of s.31 infants lived in the most deprived quintile in Wales (37% vs. 28%), were born before full term (15% vs. 7%) and were of low birthweight (17% vs. 7%).

Table 2: Cohort demographics and perinatal factors.

|

s.31 infants,

N = 1,332 |

Comparison group,

N = 204,417 |

p | |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 626 (47.0%) | 99,965 (48.9%) | |

| Male | 706 (53.0%) | 104,452 (51.1%) | |

| Deprivation Quintile | ∗ ∗ ∗ | ||

| 1 Least deprived | 129 (9.7%) | 33,790 (16.5%) | |

| 2 | 175 (13.1%) | 31,799 (15.6%) | |

| 3 | 239 (17.9%) | 38,713 (18.9%) | |

| 4 | 299 (22.4%) | 43,691 (21.4%) | |

| 5 Most deprived | 490 (36.8%) | 56,424 (27.6%) | |

| Birth weight category | ∗ ∗ ∗ | ||

| Normal (2.5–4.0kg) | 1,028 (77.2%) | 165,535 (81.0%) | |

| Very or extremely low (<1.5kg) | 29 (2.2%) | 1,850 (0.9%) | |

| Low (1.5–2.5kg) | 198 (14.9%) | 12,141 (5.9%) | |

| High (4–4.5kg) | 59 (4.4%) | 19,479 (9.5%) | |

| Very or extremely high (>4.5kg) | 10 (0.8%) | 3,370 (1.6%) | |

| Missing | 8 (0.6%) | 2,042 (1.0%) | |

| Maternal age at birth* | 25.6 (6.3) | 29.3 (5.7) | ∗ ∗ ∗ |

| Gestational age category | ∗ ∗ ∗ | ||

| Term (37–41 weeks) | 1,085 (81.5%) | 178,610 (87.4%) | |

| Very or extremely pre-term (<31 weeks) | 29 (2.2%) | 2080 (1.0%) | |

| Pre-term (32–36 weeks) | 170 (12.8%) | 12,629 (6.2%) | |

| Late term (42–44 weeks) | 38 (2.9%) | 8,449 (4.1%) | |

| Missing | 10 (0.8%) | 2,649 (1.3%) | |

| Total birth number | |||

| 1 | 1,281 (96.2%) | 19,8624 (97.2%) | |

| 2+ | 51 (3.8%) | 5631 (2.8%) | |

| Previous live births (parity) | ∗ ∗ ∗ | ||

| 0 | 453 (34%) | 78,276 (34.7%) | |

| 1 | 276 (20.7%) | 59,733 (26.5%) | |

| 2 | 198 (14.9%) | 23,204 (10.3%) | |

| 3+ | 239 (17.9%) | 34,620 (15.4%) | |

| Missing | 166 (12.5%) | 29,688 (13.2%) | |

| Apgar score | ∗ ∗ ∗ | ||

| 10 | 746 (63.8%) | 121,920 (65.9%) | |

| 9 | 335. (28.6%) | 54,093 (29.2%) | |

| <9 | 89 (7.7%) | 9063 (4.9%) | |

| Missing | 162 (12%) | 19,341 (9%) | |

| Known smoker | 309 (23%) | 16,774 (8.2%) | ∗ ∗ ∗ |

| Missing | 845 (62%) | 131,292 (63%) | |

| Maternal substance use | ∗ ∗ ∗ | ||

| Alcohol | 296 (22%) | 6,692 (3%) | |

| Substance use | 189 (14%) | 3,010 (1%) | |

| Any maternal mental health record | 1,005 (75%) | 62,872 (31%) | ∗ ∗ ∗ |

Note: shows n and (%) unless otherwise indicated; Maternal substance use and mental health is based on any maternal event recorded before the child’s birth; Variables: *Mean (standard deviation, SD); p-value: *** = < 0.001, ** < 0.01.

In terms of the mothers’ characteristics, we found differences between the mothers of s.31 infants and the mothers of infants in the comparison group. Specifically, a history of smoking was more prevalent in mothers of s.31 infants (23% vs 8%). Compared to mothers of infants in the comparison group, a greater proportion of mothers of s.31 infants had a history of problematic alcohol use (22% vs. 3%) and a history of substance use (14% vs. 1%).

The average maternal age at birth was lower for s.31 infants (s.31 infants = 25.6 years, SD = 6.3 comparison group = 29.3 years, SD = 5.7). Three quarters of s.31 infants had mothers with a history of at least one mental health illness event (n = 1,005, 75%, comparison group: n = 62,872, 31%). This means the s.31 mothers were younger in general but had a greater proportion of mental health events than the comparison group. The most common mental illnesses across groups were depression and anxiety. However, depression and anxiety were over twice as common in mothers of s.31 infants (s.31 infants: n = 934, 70%; comparison group: n = 61,621, 30%).

Volume of healthcare use

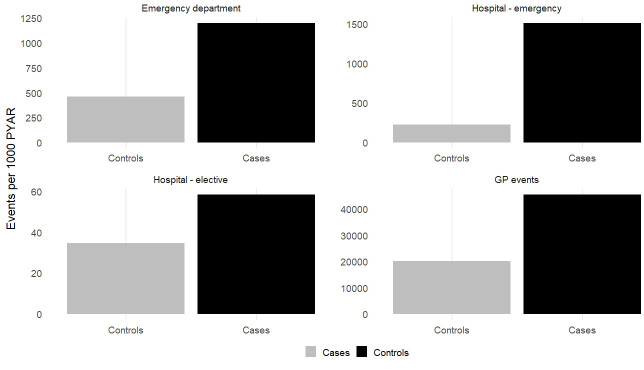

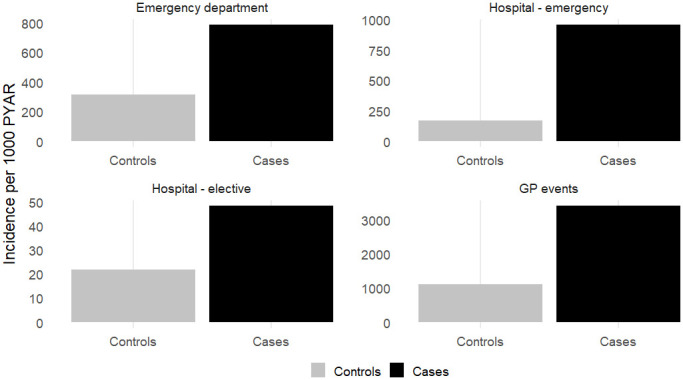

Figure 2 shows the event rate per 1,000 PYAR for each healthcare setting, by s.31 infants and the comparison group, while Figure 3 shows the incidence of events per 1,000 PYAR for each healthcare setting, by s.31 infants and the comparison group. As shown, infants in s.31 proceedings had a greater number of events and a higher incidence of events across all healthcare settings, suggesting greater healthcare needs than infants who were not involved in care and supervision proceedings.

Figure 2: Events per 1000 PYAR, for each healthcare setting.

Figure 3: Incidence per 1000 PYAR, for each healthcare setting.

Fully adjusted models showed that the incidence of ED attendance was 93% (incidence rate ratio (IRR) =1.93, CI= 1.67–2.22, p < 0.001) greater for s.31 infants than the comparison group (Table 3), and the event rate was 83% greater (event rate ratio (RR) =1.83, CI = 1.57–2.12, p < 0.001). The incidence of emergency hospital admissions was over four times greater for s.31 infants (IRR = 4.03, CI = 3.53–4.55, p < 0.001) and the event rate of emergency hospital admissions was also over four times greater for s.31 infants (RR = 4.6, CI = 3.90–5.41, p < 0.001). Finally, the incidence of GP visits was three times greater for s.31 infants (IRR = 3.09, CI = 2.89–3.31, p < 0.001), and the event rate of GP visits for s.31 infants was double that of the comparison group (RR = 2.02, CI = 1.94–2.11, p <0.001). There was no difference evident for the event rate of elective hospital admissions (RR 1.93 (0.94–3.9), although s.31 infants had a 94% higher incidence of elective hospital admissions compared to the comparison group (IRR = 1.94, CI = 1.07–3.22), p = 0.017. This means that s.31 infants were more likely to receive healthcare of any type at least once. Except for elective admissions, the number of events they experienced was also significantly greater.

Table 3: Healthcare use incidence and event rate ratio for s.31 infants.

| Events | Incidence | ||||

| Unadjusted RR (CI) | Adjusted□ RR (CI) | Unadjusted IRR (CI) | Adjusted□ IRR (CI) | ||

| Emergency department attendances | |||||

| s.31 Infants | 2.60 (2.28–3.27)** | 1.83 (1.57–2.12)** | 2.49 (2.19–2.82)** | 1.93 (1.67–2.22)** | |

| Emergency hospital admissions | |||||

| s.31 Infants | 6.63 (5.71–7.70)** | 4.60 (3.90–5.41)** | 5.60 (4.98–6.26)** | 4.03 (3.53–4.55)** | |

| Elective hospital admissions | |||||

| s.31 Infants | 1.68 (0.86–3.25) | 1.93 (0.94–3.94) | 2.18 (1.25–3.49) * | 1.94 (1.07–3.22) * | |

| GP attendances | |||||

| s.31 Infants | 2.26 (2.17–2.34)** | 2.02 (1.94–2.11)** | 3.06 (2.88–3.24)** | 3.09 (2.89–3.31)** | |

□Adjusted for maternal mental health, substance use, smoking status, age, and parity, as well as deprivation quintile, child sex, birthweight, total birth number (e.g., twins), gestational age and Apgar score. RR = Event rate ratios, IRR = Incidence rate ratios, CI = Confidence interval.

p-value **p < 0.001, *p < 0.05.

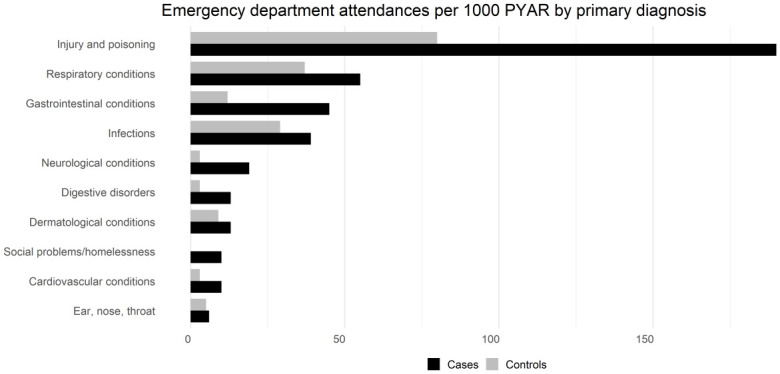

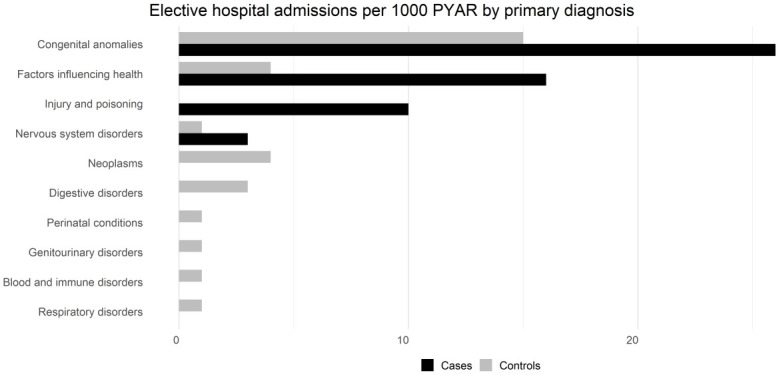

Reasons for healthcare events

The top ten known reasons for healthcare events across each healthcare setting are shown below as the number of events as a proportion per one thousand years at risk (Figure 4a–4d). Injury and poisoning were the main reasons for unplanned care, i.e. emergency department attendances (Figure 4a) or emergency hospital admissions (Figure 4b), with s.31 infants having proportionally more unplanned care events for injury and poisoning than the comparison group. For ED presentations, emergency hospital admissions, and GP visits, there were proportionally more events for .s.31 infants than the comparison group across all top ten reasons for healthcare, but for elective admissions this was only the case for congenital anomalies, factors influencing health (potential health hazards related to socioeconomic and psychosocial circumstances), injury and poisoning, and nervous system disorders. The ten most frequent diagnosis events accounted for over 80% of events for cases (emergency department = 91%, n = 347; emergency hospital admissions = 99%, n = 492; elective hospital admissions = 99%, n = 303; GP events = 83%, n = 3528), and controls (emergency department = 91%, n = 347; emergency hospital admissions = 99%, n = 492; elective hospital admissions = 99%, n = 303; GP events = 83%, n = 3528).

Figure 4a: Emergency department attendances.

Figure 4d: GP diagnosis events.

Figure 4b: Emergency hospital admissions.

Figure 4c: Elective hospital admissions.

Discussion

Summary of main findings

The findings of this study show that infants involved in s.31 care and supervision proceedings have higher healthcare use than infants in the general population in Wales, UK, even after adjusting for demographic, maternal, and child characteristics. This association was most marked for emergency hospital admissions. The main reasons for health service use varied between infants involved in s.31 proceedings and infants in the general population. The much higher proportion of infants in s.31 proceedings requiring emergency hospital admissions to be treated for injury and poisoning suggests that when these children suffer injuries, they are more severe. In this study, we present infants’ healthcare use and the primary diagnosis of these events. A benefit of this is the consistency in data recording; primary diagnosis is relatively well recorded across these events. However, this means that drawing conclusions about the causes of the infants’ injuries is challenging, and indeed beyond the scope of the current study. On the basis of published literature [10] and what is known about infants in s.31 care proceedings [30], most infants are at risk of abuse or neglect, and accidental injury or accidental intake of harmful substances is part of the picture. In addition, it is known that a proportion of infants will suffer non-accidental injury, although distinguishing between causes of injury in routine data is often challenging [31]. Similarly, respiratory condition events were proportionally higher for infants involved in s.31 care and supervision proceedings. There are a range of factors that may influence this, some of which may be environmental such as housing conditions. It is also relevant to note here that s.31 infants were three times more likely to have been born to a mother who smoked.

Comparison of research findings with previous literature

To date, there is little evidence based on large-scale data linkage studies of the health care use of infants involved in care and supervision court proceedings, although our findings are in line with those from the Children’s Health in Care in Scotland (CHiCS) study [10] which show the heightened healthcare needs of older children involved in care proceedings. The CHiCS study demonstrates that children who have experienced care have more hospital admissions, and that reasons for attendance differ between care experienced children and the general population. They found that mental, sexual, and reproductive health events were more common in the care-experienced children. They also found that injuries and poisoning events were twice as prevalent in care experienced children compared to the general population. However, there are important differences between our study and the CHiCs study, which should be noted when drawing comparisons. The CHiCS study investigated school age children in Scotland, whereas our study concentrated on infants (aged less than 1 year old) in Wales; and the CHiCS study examined the health needs of children with experience of care (i.e. following a care order), whereas our study looks at health service use for children before care or supervision order proceedings commenced.

Similar to the CHiCS study, another study explored risk factors for children aged less than 16 years old entering public care [30]. They reported a range of differences between those entering care and the general population, including maternal or child mental illness, maternal substance use, and hospital admissions. Crucially, these studies focussed on older children rather than the infants we investigated in our study.

Our study also provides support to other work that shows the important relationship between child household environment and healthcare utilisation. Particularly, parental depression [32] and maternal mental illness [33] are established markers of increased risk of child emergency health contacts. Similarly, household adult mental illness and household substance misuse is associated with greater risk of emergency admissions in children for injuries and external causes [12]. In our study, we found that infants in care and supervision court proceedings were more likely to have a mother with mental illness and/or substance misuse health events and that these factors predicted greater healthcare needs for infants. While our findings corroborate established research, our study also shows, for the first time, the heightened levels of health service utilisation for infants preceding s.31 court proceedings.

Study strengths and limitations

The availability of individual-level electronic health data for the population of children in Wales, along with rich data containing information on family justice proceedings, allows for comparison of the general population with vulnerable groups. To our knowledge this is the first population-scale study to have examined healthcare use of infants prior to their involvement in s.31 court proceedings. Further, gaining insight into health service utilisation using both primary and secondary records is also novel, enabled through access to data held within the SAIL Databank [17, 18]. Our study limitations include the scope and quality of administrative data available for research purposes, collected primarily for administrative rather than research purposes [23]. Studies using secondary data are dependent on the quality of data to derive meaningful conclusions and effort was made to ensure this through ensuring the validity of linkage. However, an absence of diagnosis could reflect a lack of recording or health contact. Therefore, our findings may underestimate healthcare needs. We looked at reasons for healthcare by looking specifically at diagnosis codes. There are many GP events where the event code is not attributed to a diagnosis (e.g. prescription events) and these events were not included in this analysis.

It is also worth noting that Cafcass data does not include out-of-court arrangements, so this study looked specifically at those infants in cases which were court mandated, although other datasets capture this; for example, where voluntary care arrangements have been instated [35]. The SAIL Databank continues to work closely with data providers to improve coverage, quality, and quantity of its data sources.

We have only been able to report on health events both known to the healthcare practitioners and coded in patient records within the study period. We found that the study population were more likely to have mothers with mental health or substance abuse healthcare history, corroborating previous research using population data [35]. However, parental mental health or substance abuse can be a barrier to children receiving adequate healthcare. This may be because of lack of awareness of healthcare providers or difficulty navigating the healthcare system, financial barriers, time constraints, or stigma [37, 38]. Additionally, a potential negative consequence of seeking medical attention for the infant may be that it would exacerbate the parent’s case for retaining custody of their child. However, this is not clear cut. Seeking support and using services can demonstrate that caregivers are competent, for example in pre-proceedings. Therefore, this might explain the higher volume of activity for the s.31 infants. However, the differences in type of activity between the groups suggests a difference in the way that these services are sought. Mental health or substance abuse can knowingly or unknowingly lead to neglect, where healthcare is not sought for the infant when it is required [36]. The figures described in our study therefore represent only clinical presentation and are expected to be an underestimate of health need.

We acknowledge the possibility of some selection bias, which can occur if the records of certain groups of individuals have different linkage rates to other groups [40]. Our flow diagram demonstrates numbers lost due to the study inclusion criteria. However, the number of infants lost due to linkage was less than 5%, so we are confident that the cohort is representative of infants involved in care proceedings across Wales. Finally, the infants in care proceedings differed from the broader population by measures that might influence their healthcare journeys, notably their gestation and deprivation profiles. However, while residual confounding may exist, we saw little to suggest a change in the point estimates between the unadjusted and adjusted models, particularly for emergency hospital admissions.

Recommendations for policy and practice

Based on the high disparity between s.31 infants and the comparison group for emergency hospital admissions, the study underscores the need for effective family support, of sufficient intensity, to reduce the likelihood of harm to infants at risk of/or subject to care proceedings, particularly where parents are suffering with their own difficulties of mental health or substance misuse. Recent evidence from the Independent Care Review [41] from families themselves, is that such help is not consistently provided, which parents themselves acknowledge reduces their ability to care for children. Parents have complained that help in the form of monitoring or ‘paper-work’ does not assist in their ability to provide safe and consistent care for children.

Injury prevention in this age group is a priority because it was the top cause of emergency care in both s.31 infants and the comparison group; however, for children at risk of care proceedings, this needs to focus on prevention of both accidental injuries and safeguarding children from intentional harm. Early identification and assessment within healthcare settings to identify infants and families at risk is important, especially for those previously unknown to social services. Continued development of guidelines to help healthcare professionals recognise signs of potential harm or adverse circumstances early may help to reduce the emergency admissions identified in this work.

There is a clear demand for multidisciplinary services to address this. These collaborations are required due to the complexity of health and social issues, such as maternal mental health concerns [41]. However, despite these complex cases, women involved in care proceedings make less use of perinatal services than do mothers in the general population (10). One reason for this is that perinatal services are limited and often not available to mothers whose children are in and out of care [39]. Addressing this need may prevent health utilisations in infants by implementing early preventative measures.

The specialist role of the perinatal metal health nurse is to "promote and enhance the developing parent-infant relationship and optimise development" [42]. As such, meeting the demand for these services should ease the challenge of improving access, and improve pathways to referrals. By working together, those delivering interventions or support can be aware of mothers who are already known to social services and then enable them to form tailored delivery plans [43]. Critically, developing this support may help reduce healthcare use by infants. More generally, supporting parents to develop positive parenting skills and create safe home environments, it is important to expand the availability of evidence-based parenting programs. These programs should focus on building healthy relationships and can be offered in healthcare or community settings or through home visiting services. Home visiting programs, facilitated by skilled professionals like health visitors or social workers, can provide regular guidance to families facing challenges, including advice on child safety and access to necessary resources and services.

Further work

We found that infants in care and supervision cases were more likely to have mothers with mental health or substance misuse concern and we adjusted models based on these predictors of healthcare need. However, there are other maternal health characteristics that might also affect the infants’ healthcare need [41]. The risk that poor maternal health and health-related habits places on child health is established [34, 44]. Therefore, associations between poor maternal physical health (for example chronic conditions) and health-related habits with child health and development can be explored to understand this relationship in greater detail. Characteristics of others within the households such as fathers or other carers could also be explored. Social norms dictate that mothers are mainly responsible for the care and protection of their children, meaning that there is a tendency of practitioners and researchers to focus on mothers [45]. However, understanding and challenging such stereotypes including those of gender and age are a crucial part of improving child protection [45]. Similarly, there are other demographic factors that may help describe the parental and infant environment such as ethnicity, asylum seeker status, and employment status. Understanding these factors may inform interventions which are tailored to needs.

Future work should explore the nature of the infants’ injuries, investigating suspected intentionality (intentional and non-intentional nature of injury codes), as well as severity. A potential linked data study could examine court and social care outcomes for children whose injuries are coded as abusive compared with non-abusive in their health records, for example using validated child maltreatment codes [29]. Investigations into the potential protective effect of social services involvement is warranted and is now possible with linked children’s social care administrative data now available within SAIL. For example, the level of support being received and how, such as those on the Child Protection Register, and how this may act as a protective factor against the adverse health consequences of mental health or substance misuse within the household.

There is also a need to understand more about outcomes following care proceedings, including understanding links between outcomes of court proceedings (different court orders and placement types) and children’s progress and health [46, 47]. It is also valuable to understand the length of time the case is open, and frequency of re-entering proceedings. These prolonged stressors could indicate more complex cases which may be associated with higher infant or maternal health needs. This stress could contribute to poor health of the infant or mother, or the complexity of the case might reflect health needs. However, this is limited for the s.31 population due to anonymisation processes that occur when children are adopted, which affects the ability to follow up individual children. Nevertheless, some adoption datasets are currently used within services, and have been linked for specific purposes.

Conclusion

Infants involved in s.31 care proceedings in Wales experience higher healthcare utilisation, particularly emergency hospital admissions for injuries and poisoning. To prevent accidental injuries and to safeguard children from intentional harm, early identification of, and support for children at risk, or those living with vulnerable parents is required. Further, strengthening available support within the community and a joined-up approach across health, social care and family justice agencies is needed. These activities will enable better outcomes, reducing the need for care proceedings, and promoting a safe environment for these young children.

Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

All authors are part of the Family Justice Data Partnership (FJDP) - a collaboration between Lancaster University and Swansea University. We would also like to thank the following for their support with this study: L Harker, Director, Nuffield Family Justice Observatory; Cafcass Cymru; Administrative Data Research Centre Wales; and Welsh government. The authors would like to acknowledge all the data providers who make data available for research, and the Adolescent Mental Health Data Platform for providing the substance use and mental health clinical codes used within this study.

Funding

Nuffield Family Justice Observatory (Nuffield FJO) aims to support the best possible decisions for children by improving the use of data and research evidence in the family justice system in England and Wales. Covering both public and private law, Nuffield FJO provides accessible analysis and research for professionals working in the family courts.

Nuffield FJO was established by the Nuffield Foundation, an independent charitable trust with a mission to advance social well-being. The Foundation funds research that informs social policy, primarily in education, welfare, and justice. It also funds student programmes for young people to develop skills and confidence in quantitative and scientific methods. The Nuffield Foundation is the founder and co-funder of the Ada Lovelace Institute and the Nuffield Council on Bioethics.

Nuffield FJO has funded this project (FJO/43766), but the views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of Nuffield FJO or the Foundation.

Authors’ contributions

IF and LJG conceptualised the study. IF performed the analysis, with IF, LC and LJG interpreting the results. IF, LJG, and LC drafted the first iteration of the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript, provided important intellectual input, approved the final version and agreed to be accountable for their contributions.

Ethics statement

The project proposal was reviewed by an independent Information Governance Review Panel (IGRP) at Swansea University. This panel ensures that work complies with information governance principles and represents an appropriate use of data in the public interest. The IGRP includes representatives of professional and regulatory bodies, data providers and the public. Approval for the project was granted by the IGRP under SAIL project 0929. Cafcass Cymru (the data owner of the family courts data) also approved use of the data for this project. The agency considered the public interest value of the study, benefits to the agency itself, as well as general standards for safe use of administrative data.

Data availability statement

The SAIL Databank (https://saildatabank.com/) was used to access all data for this study. The data is accessible via a two-stage application process consisting of scoping and governance review to assess user and project approvals.

References

- 1.Alrouh B, Broadhurst K, Cusworth L, Griffiths L, Johnson RD, Akbari A, et al. Born into care: newborns and infants in care proceedings in Wales. 2019. [cited 2023. Jul 1]; www.nuffieldfjo.org

- 2.Murray ET, Lacey R, Maughan B, Sacker A. Non-parental care in childhood and health up to 30 years later: ONS Longitudinal Study 1971-2011. Eur J Public Health. 2020. Dec 1 [cited 2023. Jul 1];30(6):1121–7. 10.1093/eurpub/ckaa113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ford T, Vostanis P, Meltzer H, Goodman R. Psychiatric disorder among British children looked after by local authorities: comparison with children living in private households. Br J Psychiatry. 2007. 319–25. 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.025023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baldwin H, Biehal N, Cusworth L, Wade J, Allgar V, Vostanis P. Disentangling the effect of out-of-home care on child mental health. Child Abuse Negl. 2019. 88:189–200. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McSherry D, Malet MF, McLaughlin K, Adams C, O’Neill N, Cole J, et al. Mind Your Health: The physical and mental health of looked after children and young people in Northern Ireland. Queens University Belfast; 2015. https://pure.qub.ac.uk/en/publications/mind-your-health-the-physical-and-mental-health-of-looked-after-c.

- 6.Croft GA. Meeting the physical health needs of our looked after children. Arch Dis Child. 2014. 99(2):99–100. 10.1136/archdischild-2013-304857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fleming M, McLay JS, Clark D, King A, MacKay DF, Minnis H, et al. Educational and health outcomes of schoolchildren in local authority care in Scotland: A retrospective record linkage study. PLoS Med. 2021;18(11):1–20. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allik M, Brown D, Taylor C, Lūka B, Macintyre C, Leyland AH, et al. Cohort profile: The “Children’s Health in Care in Scotland” (CHiCS) study-a longitudinal dataset to compare health outcomes for care experienced children and general population children. BMJ Open. 2021; 11:54664. 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-054664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mc Grath-Lone L, Libuy N, Harron K, Jay MA, Wijlaars L, Etoori D, et al. Data Resource Profile: The Education and Child Health Insights from Linked Data (ECHILD) Database. Int J Epidemiol. 2022. Feb 1;51(1):17-17F. 10.1093/ije/dyab149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Griffiths LJ, Johnson RD, Broadhurst K, Bedston S, Cusworth L, Alrouh B, et al. Maternal health, pregnancy and birth outcomes for women involved in care proceedings in Wales: a linked data study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020. Dec 1;20(1). 10.1186/s12884-020-03370-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson RD, Akbari A, Thompson S, Grifths LJ. Health vulnerabilities of parents in care proceedings in Wales. 2021; www.nuffieldfjo.org.uk

- 12.Dreyer K, Williamson RAP, Hargreaves DS, Rosen R, Deeny SR. Associations between parental mental health and other family factors and healthcare utilisation among children and young people: a retrospective, cross-sectional study of linked healthcare data. BMJ Paediatr open. 2018;2(1). 10.1136/bmjpo-2018-000266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roy, J. (2021). Children living with parental substance misuse: A cross-sectional profile of children and families referred to children’s social care. Child and Family Social Work, 26(1), 122–131. 10.1111/CFS.12795 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The health of older children and young people subject to care proceedings in Wales - Nuffield Family Justice Observatory. 2021; https://www.nuffieldfjo.org.uk/resource/health-young-people-care-wales

- 15.Cox P, McPherson S, Mason C, Ryan M, Baxter V. Reducing Recurrent Care Proceedings: Building a Local Evidence Base in England. Soc 2020, Vol 10, Page 88. https://www.mdpi.com/2075-4698/10/4/88/htm [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mccracken K, Priest S, Fitzsimons A, Bracewell K, Torchia K, Parry W. Children’s Social Care Innovation Programme Evaluation Report 49 Evaluation of Pause. 2017.

- 17.Jones KH, Ford DV, Thompson S, Lyons R. A Profile of the SAIL Databank on the UK Secure Research Platform. Int J Popul Data Sci. 2019;4(2). 10.23889/ijpds.v4i2.1134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ford D V., Jones KH, Verplancke JP, Lyons RA, John G, Brown G, et al. The SAIL Databank: Building a national architecture for e-health research and evaluation. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9, 3889. 10.1186/1472-6963-9-157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lyons RA, Jones KH, John G, Brooks CJ, Verplancke JP, Ford D V., et al. The SAIL databank: Linking multiple health and social care datasets. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2009;9(1). 10.1186/1472-6947-9-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodgers SE, Lyons RA, Dsilva R, Jones KH, Brooks CJ, Ford D V., et al. Residential Anonymous Linking Fields (RALFs): A novel information infrastructure to study the interaction between the environment and individuals’ health. J Public Health (Bangkok). 2009; 31(4):582–8. 10.1093/pubmed/fdp041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schnier C, Wilkinson T, Akbari A, Orton C, Sleegers K, Gallacher J, et al. The Secure Anonymised Information Linkage databank Dementia e-cohort (SAIL-DeC). Int J Popul data Sci. 2020. Jan 30;5(1). 10.23889/ijpds.v5i1.1121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson RD, Griffiths LJ, Hollinghurst JP, Akbari A, Lee A, Thompson DA, et al. Deriving household composition using population-scale electronic health record data—A reproducible methodology. PLoS One. 2021;16(3):e0248195. 10.1371/journal.pone.0248195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson RD, Ford D V., Broadhurst K, Cusworth L, Jones KH, Akbari A, et al. Data Resource: population level family justice administrative data with opportunities for data linkage. Int J Popul Data Sci. 2020;5(1). 10.23889/ijpds.v5i1.1339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bedston SJ, Pearson RJ, Jay MA, Broadhurst K, Gilbert R, Wijlaars L. Data Resource: Children and Family Court Advisory and Support Service (Cafcass) public family law administrative records in England. Int J Popul Data Sci. 2020;5(1). 10.23889/ijpds.v5i1.1159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.ICD-10 Version:2010. https://icd.who.int/browse10/2010/en.

- 26.Welsh Government. Welsh Index of Multiple Deprivation. 2023; https://www.gov.wales/welsh-index-multiple-deprivation.

- 27.Adolescent Mental Health Data Platform. https://adolescentmentalhealth.uk/Platform.

- 28.Rees S, Watkins A, Keauffling J, John A. Incidence, Mortality and Survival in Young People with Co-Occurring Mental Disorders and Substance Use: A Retrospective Linked Routine Data Study in Wales. Clin Epidemiol. 2022;14:21–38. 10.2147/CLEP.S325235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.R: The R Project for Statistical Computing. https://www.r-project.org/.

- 30.Rehill, J. and Roe, A. (2021). What do we know about children in the family justice system? Supplementary guidance note on infographic data sources. London: Nuffield Family Justice Observatory [Google Scholar]

- 31.John A, Mcgregor J, Marchant A, Delpozo-Baños M, Farr I, Nurmatov U, et al. An external validation of coding for childhood maltreatment in routinely collected primary and secondary care data. Scientific. 2023;13. 10.1038/s41598-023-34011-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simkiss DE, Spencer NJ, Stallard N, Thorogood M. Health service use in families where children enter public care: A nested case control study using the General Practice Research Database. BMC Health Services Research. 2012;12(1):1–12. 10.1186/1472-6963-12-65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hope H, Osam CS, Kontopantelis E, Hughes S, Munford L, Ashcroft DM, et al. The healthcare resource impact of maternal mental illness on children and adolescents: UK retrospective cohort study. Br J Psychiatry. 2021. Sep 1 [cited 2023. May 26];219(3):515–22. 10.1192/bjp.2021.65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paranjothy S, Evans A, Bandyopadhyay A, Fone D, Schofield B, John A, et al. Risk of emergency hospital admission in children associated with mental disorders and alcohol misuse in the household: an electronic birth cohort study. Lancet Public Heal. 2018. Jun 1;3(6):e279–88. 10.1016/S2468-2667(18)30069-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Allnatt G, Lee A, Scourfield J, Elliott M, Broadhurst K, Griffiths L. Data resource profile: children looked after administrative records in Wales. Int J Popul Data Sci. 2022. Aug 2;7(1):1752. 10.23889/ijpds.v7i1.1752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heuckendorff S, Johansen MN, Johnsen SP, Overgaard C, Fonager K. Parental mental health conditions and use of healthcare services in children the first year of life– a register-based, nationwide study. BMC Public Health. 2021. Dec 1 [cited 2023. May 16];21(1):1–12. 10.1186/s12889-021-10625-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anderson CM, Robins CS, Greeno CG, Cahalane H, Copeland VC, Andrews RM. Why lower income mothers do not engage with the formal mental health care system: perceived barriers to care. Qual Health Res. 2006;16(7):926–43. 10.1186/s12889-021-10625-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stone R. Pregnant women and substance use: fear, stigma, and barriers to care. Heal Justice 2015. 31. 2015. Feb 12;3(1):1–15. 10.1186/s40352-015-0015-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dandona A. The Impact of Parental Substance Abuse on Children. Identifying, Treating, and Preventing Childhood Trauma in Rural Communities (pp.30-42)Publisher: IGI Global, USA. 2016. Jun 9; 30–42. 10.4018/978-1-5225-0228-9.ch003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bohensky MA, Jolley D, Sundararajan V, Evans S, Pilcher D V., Scott I, et al. Data linkage: a powerful research tool with potential problems. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010. [cited 2023. May 26];10. 10.1186/1472-6963-10-346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Department for Education. The independent review of children’s social care. 2022.

- 42.Perinatal mental health network. Specialist perinatal metal health professionals role definitions and support structures. 2021.

- 43.Smith SS. Barriers to accessing mental health services for women with perinatal mental illness: systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative studies in the UK. BMJ Open. 2019;9:24803. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Chapman DP, Williamson DF, Giles WH. Childhood abuse, household dysfunction, and the risk of attempted suicide throughout the life span: Findings from the adverse childhood experiences study. J Am Med Assoc. 2001. Dec 26;286(24):3089–96. 10.1001/jama.286.24.3089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wild, J. (2023). Gendered Discourses of Responsibility and Domestic Abuse Victim-Blame in the English Children’s Social Care System. Journal of Family Violence, 38(7), 1391–1403. 10.1007/s10896-022-00431-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grant C, Radley J, Philip G, Lacey R, Blackburn R, Powell C, et al. Parental health in the context of public family care proceedings: A scoping review of evidence and interventions. Child Abuse Negl. 2023;140:106160. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2023.106160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dickens J, Masson J, Garside L, Young J, Bader K. Courts, care proceedings and outcomes uncertainty: The challenges of achieving and assessing “good outcomes” for children after child protection proceedings. Child Fam Soc Work. 2019;24(4):574–81. 10.1111/cfs.12638 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The SAIL Databank (https://saildatabank.com/) was used to access all data for this study. The data is accessible via a two-stage application process consisting of scoping and governance review to assess user and project approvals.