Abstract

Aspergillus is a ubiquitous saprophytic mold that humans and animals constantly inhale. In health, the conidia are eliminated by the innate immune system. However, a subset of individuals with risk factors such as neutropenia, receiving high doses of glucocorticoids or certain biologicals, and recipients of hematopoietic or solid-organ transplants develop invasive aspergillosis. The mortality associated with invasive aspergillosis is 42%–64%. The early diagnosis of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in patients without classical risk factors remains challenging. We present a case of an elderly female with uncontrolled diabetes mellitus who presented with acute-onset chest pain, breathlessness, and cough without expectoration. On evaluation, her chest radiograph showed a mass lesion in the right upper zone. 18Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-positron emission tomography-computed tomography showed two FDG-avid lesions in the apical and medial segment of the right upper lobe. The lung biopsy was negative for malignancy; however, she was diagnosed with invasive pulmonary aspergillosis based on serum and bronchoalveolar fluid galactomannan positivity. She was managed with voriconazole with complete resolution of the lesion.

Keywords: Aspergillus, case report, diabetes mellitus, galactomannan, lung cancer

INTRODUCTION

Aspergillus is a ubiquitous saprophytic mold that humans and animals constantly inhale. In health, the conidia are eliminated by the innate immune system. However, a subset of individuals with risk factors like neutropenia, receiving high doses of glucocorticoids or certain biologicals, and recipients of hematopoietic or solid-organ transplants develop invasive aspergillosis.[1] The mortality associated with invasive aspergillosis is 42%–64%.[2] Diabetic patients have 1.38 times more risk of having mycosis as compared to the general population; also, they are at increased risk of developing invasive fungal infections.[3] Pulmonary Aspergillosis, Cryptococcosis, and Actinomycosis can rarely present as a mass lesion in the lung, masquerading as lung cancer.[1,4,5] The early diagnosis of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in patients without classical risk factors remains challenging. Furthermore, the positive serum and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid galactomannan has established a role in diagnosing invasive aspergillosis in neutropenic patients only. We present a case of an elderly female with uncontrolled diabetes mellitus who presented with acute-onset chest pain, breathlessness, and cough without expectoration. On evaluation, her chest radiograph showed a mass lesion in the right upper zone. 18Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) showed two FDG avid lesions in the apical and medial segment of the right upper lobe. The lung biopsy was negative for malignancy; however, she was diagnosed with invasive pulmonary aspergillosis based on serum and bronchoalveolar fluid galactomannan positivity. She was managed with voriconazole with complete resolution of the lesion.

CASE REPORT

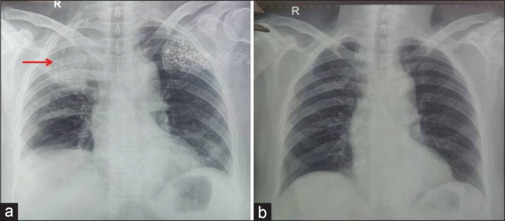

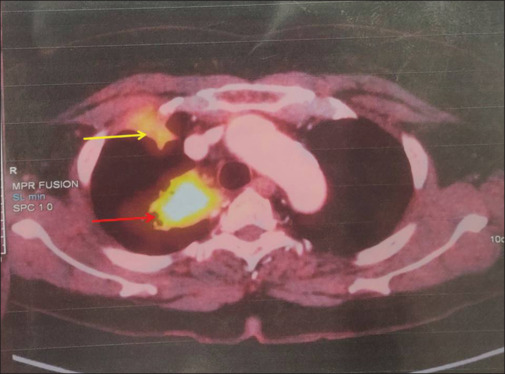

A 64-year-old female with a history of diabetes mellitus and hypertension on irregular medication for the past 5 years presented to the emergency department with complaints of chest pain localized to the right side and pleuritic in nature, cough without expectoration, and breathlessness on exertion of one-day duration. She denied any history of fever, hemoptysis, or prolonged immobilization. She did not have palpitations, angina, syncope, or presyncope; however, she gave a history of increased frequency of micturition and dryness of the mouth. On general examination, she had a pulse rate of 74 beats/min, blood pressure of 148/84 mm of Hg, and oxygen saturation of 88% on room air. She was markedly dehydrated and also had pallor. Her respiratory system examination was normal. Initial laboratory evaluation showed anemia, neutrophilic leukocytosis, and hyperglycemia, with mildly raised C-reactive protein and serum procalcitonin levels [Table 1]. She did not have acidosis, and urine ketones were negative. Her blood glucose level on admission was 345 mg/dL, with an HBA1C level of 13.9%. Electrocardiogram was normal. The initial chest radiograph showed a nonhomogeneous opacity in the right upper zone [Figure 1a]. She was managed as a case of community-acquired pneumonia with suspicion of pseudomonas infection due to uncontrolled diabetes mellitus with broad-spectrum injectable antibiotics, insulin infusion, and oxygen inhalation by nasal prongs. The next day, she underwent contrast-enhanced CT of the chest, which showed a mass lesion in the apical and medial segments of the right upper lobe. Subsequently, the patient underwent 18FDG whole-body (WB)-PET, which showed two mass lesions in the right suprahilar region suggestive of primary malignant pathology with SUV of 6.72 [Figure 2]. The patient underwent fiberoptic bronchoscopy and BAL. BAL samples were sent for galactomannan and mucormycosis real-time polymerase chain reaction [Table 1]. At the same time, the patient underwent computed tomographic-guided biopsy of the mass lesion in the right upper lobe of the lung. The BAL and serum galactomannan were positive, and the biopsy was negative for malignancy. The patient was started on injection caspofungin 70 mg intravenous on day 1, followed by 50 mg intravenously once a day, and tablet voriconazole 200 mg twice daily. The patient gradually improved for the next 15 days. She had complete resolution of the mass lesion on the chest radiograph after one month of therapy [Figure 1b].

Table 1.

Laboratory investigations

| Laboratory parameters | Value | Reference range |

|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 10.5 | 12–16 g/dL |

| Total leukocyte count (cells/μL) | 11,230 | 4000–11,000/μL |

| Platelets (cells/μL) | 256,000 | 150,000–450,000/μL |

| Blood urea (mg/dL) | 55.6 | 8–20 mg/dL |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.16 | 0.50–1.10 mg/dL |

| Serum sodium (mEq/L) | 128 | 136–145 mEq/L |

| Serum potassium (mEq/L) | 4.9 | 3.5–5 mEq/L |

| Total protein (g/dL) | 6.5 | 5.5–9 g/dL |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.0 | 3.5–5.5 g/dL |

| Globulin (g/dL) | 3.5 | 2.5–4.0 g/dL |

| C-reactive protein | 0.4 | ≤0.5 mg/dL |

| HbA1c | 13.9 | <5.7% |

| Serum procalcitonin | 0.78 | ≤0.10 ng/mL |

| Serum galactomannan | 0.58 | <0.25 |

| BAL fluid galactomannan | 2.08 | <0.05 |

| BAL fluid mucormycosis RT-PCR | Target not detected |

BAL: Bronchoalveolar lavage, RT-PCR: Real-time polymerase chain reaction, HbA1c: Glycated hemoglobin

Figure 1.

The chest radiograph posterior-anterior view. (a) The red arrow shows a homogeneous opacity involving the right upper zone. (b) A normal chest radiograph after 8 weeks with complete resolution of the lesion in Figure 1a

Figure 2.

The whole-body positron emission tomography. The red arrow shows a fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) avid ill-defined mass lesion with speculated margins in the right suprahilar region with SUV of 6.72. The yellow arrow shows an FDG-avid pleural-based ill-defined nodule in the right lung upper lobe at the level of the second right rib with no erosion of the bone

DISCUSSION

Aspergillosis has been described to cause lobar collapse, mimicking late-onset asthma, mediastinal mass, and multiple lung nodules. However, Aspergillus-related lung mass presenting as primary lung cancer has been seldom reported.[1] Our patient presented with acute-onset breathlessness, pleuritic chest pain, and cough. Initially, we considered the differential diagnosis of pulmonary thromboembolism, acute coronary syndrome, or pneumonia. The patient Mohamed et al.[1] reported also had a similar presentation.

Diabetes mellitus is a disorder characterized by persistent hyperglycemia. Recently, diabetes mellitus has been recognized as a risk factor for invasive pulmonary aspergillosis and unusual fungi like Histoplasma capsulatum.[6] In diabetic patients, anemia, hypoalbuminemia, and raised serum creatinine increase the risk of invasive fungal infections. Our patient had anemia and hypoalbuminemia along with diabetes mellitus.

Another challenge is to establish the diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis. The proven diagnosis is established by demonstrating the hyphal elements in tissue biopsy from the affected site, like skin/lung or culture of the fungi in sterile body fluid or blood.[7] Diagnosing probable invasive fungal disease requires at least one host factor, one clinical feature, and mycologic evidence and is proposed for only immunocompromised patients. Raised serum or BAL fluid galactomannan level is accepted as mycologic evidence. Recently, a study tried to establish serum/BAL fluid galactomannan levels as the marker of invasive aspergillosis in immunocompetent patients. BAL fluid galactomannan level of more than 0.7 was associated with a sensitivity of 72.97% and specificity of 89.16%.[8] Our patient did not have a conventional host factor but had clinical and mycological evidence. Moreover, her BAL fluid galactomannan level was 2.08. Thus, we established the diagnosis of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis.

The management of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis is guided by the Infectious Diseases Society of America 2016 practice guidelines for the management of aspergillosis.[9] The preferred therapy is monotherapy with voriconazole, posaconazole, isavuconazole, and itraconazole. Amphotericin B should be used in suspected patients pending the confirmation of diagnosis. We managed our patient with a combination of injection caspofungin and tablet voriconazole for 2 weeks, followed by monotherapy with voriconazole for 6 weeks. Our patient had a complete recovery with a resolution of lung mass in 8 weeks.

This case highlights the fact that investigations can misguide the clinician. The WB-PET-CT was suggestive of primary lung malignancy; however, the biopsy from the mass was negative for the malignancy. This case further emphasizes that the high index of suspicion can lead to correct diagnosis and management with a favorable outcome.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient has given her consent for her images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patient understands that her name and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal her identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Research quality and ethics statement

The authors followed applicable EQUATOR Network (http://www.equator-network.org/) guidelines, notably the CARE guideline, during the conduct of this report.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank all the nursing and paramedical staff for their support in managing this case.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mohamed S, Patel AJ, Darr A, Jawad F, Steyn R. Aspergillus-related lung mass masquerading as a lung tumour. J Surg Case Rep. 2020;2020:rjaa169. doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjaa169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bassetti M, Garnacho-Montero J, Calandra T, Kullberg B, Dimopoulos G, Azoulay E, et al. Intensive care medicine research agenda on invasive fungal infection in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43:1225–38. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4731-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lao M, Li C, Li J, Chen D, Ding M, Gong Y. Opportunistic invasive fungal disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus from Southern China: Clinical features and associated factors. J Diabetes Investig. 2020;11:731–44. doi: 10.1111/jdi.13183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Echieh C, Nwagboso C, Ogbudu S, Eze J, Ochang E, Jibrin P, et al. Invasive pulmonary cryptococcal infection masquerading as lung cancer with brain metastases: A case report. J West Afr Coll Surg. 2020;10:30–4. doi: 10.4103/jwas.jwas_47_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bunkar ML, Gupta PR, Takhar R, Rajpoot GS, Arya S. Pulmonary actinomycosis masquerading as lung cancer: Case letter. Lung India. 2016;33:460–2. doi: 10.4103/0970-2113.184944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nunes JO, Pillon KR, Bizerra PL, Paniago AM, Mendes RP, Chang MR. The simultaneous occurrence of histoplasmosis and cryptococcal fungemia: A case report and review of the literature. Mycopathologia. 2016;181:891–7. doi: 10.1007/s11046-016-0036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donnelly JP, Chen SC, Kauffman CA, Steinbach WJ, Baddley JW, Verweij PE, et al. Revision and update of the consensus definitions of invasive fungal disease from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer and the mycoses study group education and research consortium. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:1367–76. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou W, Li H, Zhang Y, Huang M, He Q, Li P, et al. Diagnostic value of galactomannan antigen test in serum and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid samples from patients with nonneutropenic invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2017;55:2153–61. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00345-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patterson TF, Thompson GR, 3rd, Denning DW, Fishman JA, Hadley S, Herbrecht R, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of aspergillosis: 2016 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:e1–60. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]