Abstract

Context:

Agriculture is one of the occupations with the highest risk of injuries and fatalities but the farmers are ignorant about eye care and eye safety.

Aim:

The current study aims at understanding the occupational hazard and ocular morbidities associated with agriculture and the effect of safety eyewear.

Settings and Design:

Multicenteric, cross-sectional, observational study was conducted in two states of India: Tamil Nadu and Karnataka. Subjects were agriculture workers recruited by convenience sampling.

Methods and Material:

The study was done in three phases: Phase 1: Visual task analysis (VTA), Phase 2: Comprehensive eye examination, and Phase 3: Spectacle compliance assessment. The Standard of Living Index scale was administered to assess the socioeconomic status of the participants.

Statistical Analysis Used:

Descriptive statistics and logistic regression.

Results:

A study involving 276 workers (39.4% male, 65.2% female) found that VTA agricultural tasks were visually less demanding but hazardous, carrying the risk of ocular and nonocular injuries. Ocular injuries accounted for 9.4% (26 cases), while nonocular injuries accounted for 9.8% (27 cases). Spectacle compliance assessment revealed that 91.8% (157 out of 171 workers) reported improved visual comfort, reduced dust exposure, and enhanced safety with safety eyewear.

Conclusions:

This study illustrates numerous types of hazards associated with the occupation of farming. The study population had a 9.4% prevalence of ocular injuries. Refractive safety eyewear was reported to improve worker visual comfort.

Keywords: Farmers, hazard, ocular injury, ocular morbidities, safety eyewear

INTRODUCTION

In India, 54.6% unorganized sector workforce lies in agriculture and its related sectors.[1] Agriculture is one of the traditional occupations, with the highest risk of injuries and fatalities, followed by mining and construction.[2] Workers engage in various tasks throughout the crop growth, which exposes them to risks associated with the use of farming tools, pesticides, and challenging weather conditions.[3]

Agricultural accident incident rate was reported to be 589 per 1,00,000 workers per year in the Northeast part of India. In West Bengal, the rate of work-related injuries was reported to be 8.99 and 7.89 per 1000 workers per year for male and female farm workers, respectively.[4] Despite advancements in farming equipment, manual hand tools continue to be a significant factor, contributing to 64.7% of farm injuries, that frequently occurs to the hands and legs.[3,4,5]

The crops grown in India vary regionally, influencing farming practices and ocular injuries. Sugarcane leaf-related injuries are prevalent in the Northern and Western regions. In the central and southern regions, ocular injuries occur during paddy cultivation, specifically during harvesting and manual threshing.[6] In Chhattisgarh, the frequency of ocular injury was 0.7% among workers compliant in wearing safety eyewear compared to 11.3% among noncompliant workers.[7]

Despite the high risk of ocular injuries, there is a paucity of research on risk factors and the effectiveness of safety eyewear among agricultural workers. This study aims to explore occupational hazards in agriculture, particularly concerning ocular health, and assess the impact of safety eyewear.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

A multicenteric, cross-sectional, observational study was conducted in Tamil Nadu and Karnataka. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee and Institutional Review Board of Vision Research Foundation and followed the principles of Declaration of Helsinki. A uniform study protocol was implemented across all three centers. The study consisted of three phases, with participants selected through convenience sampling. Eligibility criteria included participants over 20 years of age, residing in the chosen areas, and engaged in agriculture or related activities for at least two years. Excluded were farmers who spent less than 10 h per week working on their farms.

Phase 1

Visual task analysis (VTA): The study aimed to assess task characteristics, vision requirements, and occupational and environmental hazards related to agriculture and allied tasks using Grundy’s Task Analysis Nomogram.[8] VTA was conducted in all three districts to gain insights into crop cultivation, farming techniques, and associated risks. The team scrutinized work patterns, examined task nature and processes, and identified workplace hazards.

Phase 2

All the participants had a comprehensive eye examination in community setting respective center. The occupational history [Appendix 1] was incorporated, along with general history, after VTA. Distance visual acuity was measured using an internally illuminated Log MAR chart, and near visual acuity was tested with a continuous text chart, followed by objective and subjective refraction. A handheld slit-lamp biomicroscope examined the anterior segment, intraocular pressure was measured with a noncontact tonometer, and a nonmydriatic fundus camera examined the posterior segment.

The Standard of Living Index (SLI) calculates socioeconomic status, considering household items, amenities, and ownership of land or farm equipment.[9] Following the eye examination, workers received either single-vision or bifocal spectacles based on occupational and age-related requirements. All workers, regardless of refractive error, received safety eyewear with a secure headband for farming activities. Spectacle measurements were collected and dispensed within two weeks from the date of examination.

Phase 3

Compliance assessment was done after three weeks of dispensing spectacles through telephone calls. It had a set of questions to assess the usability, durability, and perceived impact at work.

Statistical analysis

The data collected from three centers were entered into Microsoft Excel and the analysis was done using SPSS statistical software version 20 (IBM statistics). Descriptive statistics were done. Logistic Regression was performed to assess the risk of ocular injuries and nonocular injuries, associated with age, gender, socioeconomic status, years of experience, use of spectacles, and presence of ocular morbidities.

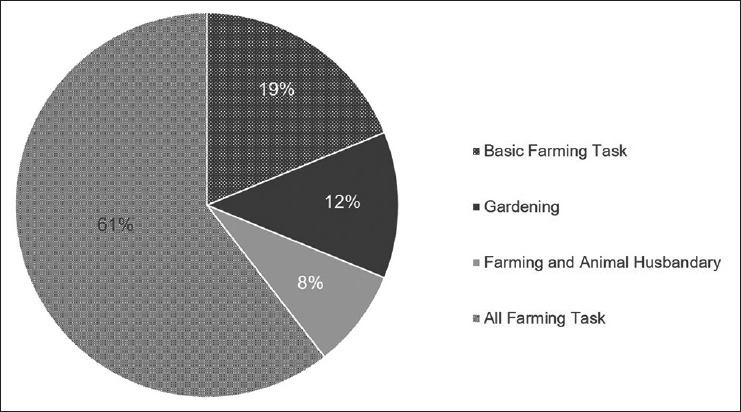

For analysis, tasks done by the farmers were classified as basic farming tasks, gardening, farming and animal husbandry, and all farming tasks.

Ethical clearance

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee and Institutional Review Board of Vision Research Foundation and followed the principles of Declaration of Helsinki. Date of the approval: 03-02-2022.

RESULTS

Phase 1: Observations from visual task analysis

From the task analysis, paddy cultivation was common in both Tamil Nadu and the Udupi district. In Tamil Nadu, seasonal vegetables/fruits/flowers and sugarcane were grown, while the Udupi district focused on areca nut, urad dal, and coconut cultivation. Workers began early in the day and worked till evening, without taking breaks. Although none of the workers used safety eyewear, they wore turbans to carry loads on their heads and to shield themselves from the sun. These workers were either full-time farmers or laborers who worked for daily wages. They were also involved in cattle rearing and animal husbandry [Figure 1]. The tasks observed were less visually demanding, larger task size, performed at intermediate to far distances, and did not require precision. However, some tasks posed potential hazards, leading to agricultural accidents and ocular injuries.

Figure 1.

Pie chart representing the various tasks performed by the workers

Physical hazards

These include flying particles while cutting, harvesting, removing the weeds, exposure to leaves/thorns of tall plants, and hit by stones while plowing and threshing the paddy. The workers were also exposed to heat, UV radiation, and adverse environmental conditions making them vulnerable to ocular morbidities like pterygium, pinguecula, and cataracts.

Chemical hazards

These include exposure to pesticides and insecticides in the form of both powder and spray.

Biological hazards

These include exposure to fungus and other parasites in the farming area that can lead to infection followed by penetrating injuries.

Ergonomic hazards

Most of the tasks were done by bending or stooping down, and the usage of farming tools in those awkward postures increases the risk of ocular injuries.

Phase 2 – Workers profile

A total of 276 workers participated in the study, among which 109 (39.4%) were male and 167 (65.2%) were female; 111 (40.2%) workers were from Thiruvallur, 71 (25.7%) were from Erode District, Tamil Nadu, and 94 (34%) were from Udupi, Karnataka. Descriptive details are presented in Table 1. The mean age of workers was 53 ± 10.7 years (26–85 years), with mean years of work experience 28 ± 14.6 years. The workers were residing at the same location for an average period of 39.6 ± 17.9 years. About 104 (37.6%) workers reported using spectacles while at work with 10.6 average years of spectacle usage. On assessing the sun protective behavior, 178 workers were using either a turban/hat/cap while at work. Based on the calculated SLI scores, the majority belong to high SLI.

Table 1.

Descriptive information of the study participants

| Variables | Thiruvallur n (%) | Erode n (%) | Udupi n (%) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of farmers | 111 | 71 | 94 | 276 |

| Female | 81 (73) | 36 (50.7) | 50 (53.1) | 167 (60.5) |

| Male | 30 (27) | 35 (49.3) | 44 (46.8) | 109 (39.5) |

| Age (Mean±SD) | 47.7±9.7 | 54.5±11.3 | 57.5±9.2 | |

| Years of experience | 25.4±12.3 | 28.8±15.5 | 32.3±15.3 | |

| Task involved | ||||

| Basic farming task | 28 (54.9) | 12 (23.5) | 11 (21.6) | 51 (18.4) |

| Gardening | 5 (14.7) | 25 (73.5) | 4 (11.8) | 34 (12.3) |

| Farming and animal husbandry | 2 (7.7) | 4 (15.4) | 20 (76.9) | 26 (9.4) |

| All farming task | 76 (46.1) | 30 (18.2) | 59 (35.8) | 165 (59.7) |

| Vision impairment status | ||||

| Mild | 22 (19.8) | 23 (32.3) | 32 (34) | 77 (27.9) |

| Moderate | 25 (22.5) | 10 (14) | 7 (7.4) | 42 (15.2) |

| Severe | 1 (0.9) | - | 3 (3.1) | 4 (1.4) |

| Blindness | 8 (7.2) | 3 (4.2) | - | 11 (4) |

| Standard of living (SLI) | ||||

| Low | 9 (8.1) | 7 (14.1) | - | 16 (5.8) |

| Medium | 40 (36) | 18 (36) | 5 (5.3) | 63 (22.8) |

| High | 62 (55.8) | 46 (55.5) | 89 (94.6) | 197 (71.4) |

Frequently reported visual and ocular symptoms included headache 75 (27.1%), eye pain/strain 29 (10.5%), ocular irritation 55 (19.9%), and foreign body sensation 7 (2.5%). About 37 (13.4%) workers presented with difficulty in the vision for both distance and near; 104 (38%) reported difficulty for distance alone; and 24 (8.6%) reported difficulty for near alone. Based on their presenting visual acuity, the workers were asked to rate their work-related visual performance as good, fair, or poor, and the results were 148 (53.6%), 94 (34%), and 34 (12.3%), respectively.

The prevalence of visual impairment was mild 78 (28.2%), moderate 57 (20.6%), and severe 20 (7.2%) after refractive correction. At the end of the comprehensive eye examination, 204 (73.5%) workers were dispensed with new spectacles of which 166 (60.1%) workers were dispensed with refractive error-incorporated safety eyewear in addition along with headbands. The workers were educated on the need for safety eyewear and its appropriate usage.

Ocular morbidities

The symptoms of glare associated with sunlight at work were reported by 131 (47.4%) workers. The prevalence of ocular surface morbidities such as pterygium was found to be 46 (16.6%), pinguecula 33 (11.6%), and conjunctival pigmentation 26 (23.3%). The prevalence of cataractous lens changes were present in 215 (78%) of the workers. The workers whose vision did not improve were referred for further examination (81, 29.3%): retina examination (15, 18.5%), ocular surface (3, 3.7%), and cataract (50, 61.7%). The risk factors for ocular morbidity are presented in Table 2. The usage of spectacles while at work was observed to be protective against cataract development (OR: 0.42, 95% CI: 0.22–0.82).

Table 2.

Associated risk factors for ocular morbidities

| Variables | OR (95% CI) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pterygium | Pinguecula | Cataract | |

| Age | 1.00 (0.97–1.03) | 0.97 (0.94–1.0) | 1.20 (1.14–1.26) |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Male | 1.21 (0.64–2.31) | 1.00 (0.48–2.1) | 1.93 (1.04–3.60) |

| Years of experience | 1.00 (0.98–1.02) | 0.99 (0.96–1.01) | 1.05 (1.02–1.07) |

| Task Done | |||

| Basic farming task | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Gardening | 0.45 (0.11–1.80) | 0.20 (0.03–1.63) | 1.32 (0.46–3.74) |

| Farming and animal husbandry | 0.98 (0.26–3.59) | 1.75 (0.49–6.23) | 1.23 (0.38–3.98) |

| All farming tasks | 1.03 (0.45–2.35) | 0.87 (0.35–2.19) | 1.22 (0.59–2.54) |

| Resident of the location | 1.00 (0.98–1.02) | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) | 1.04 (1.03–1.06) |

| Use of spectacles at work | |||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 0.76 (0.40–1.45) | 0.94 (0.45–1.98) | 0.42 (0.22–0.82) |

| Use of hat/turban at work | |||

| Yes | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| No | 0.94 (0.48–1.86) | 0.82 (0.37–1.79) | 1.48 (0.78–2.81) |

| Socioeconomic status | |||

| High income | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Medium income | 0.38 (0.14–1.01) | 1.52 (0.68–3.39) | 2.21 (0.98–4.97) |

| Low income | 0.78 (0.21–2.83) | 0.01 (0–2.83) | 1.18 (0.50–6.48) |

Ocular and nonocular injuries

The prevalence of ocular injury was 26 (9.4%). Most of the workers reported the frequency of injury to be rare (15, 57.7%) followed by sometimes (5, 19.2%) and often (4, 15.3%). Those who reported sometimes and often were involved in paddy and urad dal cultivation of Erode and Udupi. The prevalence of nonocular farm injuries was 27 (9.8%), with the reported frequency of rarely (14, 5%) and sometimes (6, 2.1%). The site of injury and the associated task were observed to be diverse. The injuries in the hand and finger (9, 33.3%) were reported to be associated with the usage of tools like cutter and sickle while involved in tasks like the removal of weeds/grass, harvesting crops, and cutting wood. Leg injuries (7, 25.9%) were observed to be associated with the task of climbing trees, plowing, and removing weeds. History of fractures in the hand and leg were reported by 3 (11.1%) workers and injury in the head was reported by 8 (29.6%) workers associated with tasks like climbing trees and cattle grazing.

The risk of nonocular injuries was associated with age, male gender, and years of experience of the farmers, whereas there were no risk factors noted for ocular injury [Table 3]. The workers with a history of ocular injuries were observed to have six times of risk of nonocular injuries (OR 6.10, 95% CI: 2.39–15.56). Ocular morbidities especially cataractous lens changes did not have any effect on the incidence of ocular/nonocular injury (OR: 0.94, 95% CI: 0.35–1.86).

Table 3.

The risk factors for ocular and nonocular injuries among farmers

| Variables | Ocular Injury |

Nonocular Injury |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Age (in years) | 1.00 (0.971–1.04) | 0.672 | 1.05 (1.01–`1.09) | 0.011 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 1 | 1 | ||

| Male | 0.997 (0.43–2.29) | 0.995 | 4.37 (1.91–10.00) | <0.001 |

| Years of experience (in years) | 1.02 (0.98–1.04) | 0.245 | 1.03 (1.01–1.06) | 0.006 |

| Task done | ||||

| Basic farming task | 1 | 1 | ||

| Gardening | 1.54 (0.20–11.57) | 0.670 | 2.65 (0.41–16.92) | 0.302 |

| Farming and animal husbandry | 1.09 (0.09–12.67) | 0.945 | 1.04 (0.09– 12.15) | 0.972 |

| All farming tasks | 3.40 (0.76–15.10) | 0.107 | 4.05 (0.92–17.84) | 0.064 |

| Use of spectacle | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.35 (0.56–3.26) | 0.498 | 0.82 (0.37–1.82) | 0.633 |

| Socioeconomic status | ||||

| High income | 1 | 1 | ||

| Medium income | 0.46 (0.13–1.60) | 0.224 | 1.32 (0.55–3.19) | 0.527 |

| Low income | 1.61 (0.43–6.01) | 0.477 | 0.97 (0.21–4.54) | 0.976 |

| Presence of lens changes | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.94 (0.35–1.86) | 0.912 | 0.94 (0.362– 2.47) | 0.912 |

| History of ocular injury | ||||

| No | - | |||

| Yes | - | 6.10 (2.39–15.56) | <0.001 | |

Perceived impact of safety eyewear

The workers who were provided with safety eyewear were assessed for compliance at work after three weeks from the date of dispensing. Of the 166 safety eyewear prescribed, 71 (42.7%) were from the Thiruvallur district, 27 (16.2%) were from Erode district, and 68 (40.9%) were from Udupi District. For the telecompliance assessment, 149 (92.5%) farmers were reachable and they responded to the compliance call. Of those who responded to the call, about 139 (93.2%) were compliant with spectacle usage at work and reported improved visual performance. Few workers (11, 7.3%) have reported a reduction in symptoms like ocular itching and irritation, foreign body sensation, and dryness.

Of the 10 workers who were noncompliant with the use of safety eyewear at work, the common reasons were: Physical discomfort (2), stopped working (3), impaired vision while working, i.e. difficulty while seeing through the bifocals (3), and not interested in using them at work (2).

DISCUSSION

Agriculture is observed to be one of the occupations with the highest risk of injuries. About 61% of workers in this study were involved in various farming activities, such as weed removal, land preparation, pesticide spraying, and harvest. VTA revealed that farming tasks, although visually less demanding, involved significant hazards due to tool usage, awkward postures, and exposure to pesticides/insecticides.[4,5]

The prevalence of ocular injuries in the current study was 9.4%. Paddy cultivation workers carry a higher risk of injury due to the sharp edges of paddy leaves and manual threshing, as noted in other studies.[6,10] Nonocular farm injuries had a prevalence rate of 9.8%, with frequent reports of hand and finger injuries. These findings align with previous studies, highlighting the prevalence of hand and finger injuries among farm workers who use tools like sickles and cutters.[3,4,5] The risk of ocular injuries showed no correlation with age, gender, years of experience, SLI index, or task involvement. Conversely, nonocular injuries were found to be associated with age, gender, and years of experience. This association can be attributed to the decline in dexterity and motor abilities that accompany age, leading to poor task performance and increased accident rates.[11] The same happens with the increase in years of experience, where the farmer’s attitude in performing tasks or using the tools may alter when aiming at task completion.[11] The other fact is the gender difference in injury risk; males are at a higher risk of injury compared to females due to their risk-taking behavior. Although not statistically significant, workers involved in multiple farming tasks have a higher risk of nonocular injuries compared to those involved in fewer tasks, possibly due to their attitude toward performing tasks.[11] Workers with ocular injuries also have a risk of nonocular injury, which may be attributed to their risk-taking behavior or poor safety practices, as ocular morbidities like cataracts do not affect injury occurrence.

The risk of cataract was observed to be associated with age, years of experience, and male gender. The workers in middle SLI had two times higher risk when compared to workers in the other groups.

The compliance with safety eyewear at the workplace was observed to be 91.8%. The safety eyewear protected the workers from exposure to dust and plant matter and reduced their existing symptoms of dryness, itching, and irritation, and it also improved their overall visual performance. With our previous experience, providing them with the headband to keep spectacles safe in place has reassured the workers to be compliant with spectacles at work. The results quite similar to a study in Chhattisgarh found that compliance with safety eyewear led to a significant decrease in ocular injuries compared to those who did not use such eyewear. The compliant group had an injury frequency of 0.7%, while the noncompliant group had a frequency of 11.3%.[7] Farmers cited poor safety behavior, lack of affordability/availability of safety eyewear, and physical discomfort as reasons for not using protective gear.[12] Overall, the use of appropriate safety eyewear was observed to reduce ocular injuries and exposure to airborne particles during agricultural tasks, improving preexisting ocular surface symptoms like irritation.

Strength and limitations

The data collected from three centers provided valuable and diverse insights. Recall bias may exist due to questions about past work experience and injury details. Missing or invalid phone numbers led to data loss for compliance assessment regarding spectacles.

CONCLUSION

The prevalence of ocular injury among farmers was 26 (9.4%), while nonocular injury accounted for 27 (9.8%). Farming tasks were less visually demanding but associated with various hazards. Refractive correction improved visual impairment, providing workers with enhanced comfort and reduced glare when using safety eyewear.

Financial support and sponsorship

The study was funded by Essilor Vision Foundation.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The study was supported by the Optometry Council of India. We thank all the optometry students and social workers for their support in the execution of this study.

APPENDIX 1

OCCUPATION-SPECIFIC HISTORY FOR FARMING AND ASSOCIATED TASKS

Farming/associated task donex___________ Years

Task done ______________________________________

Residing at current location for _________ Years

-

History of previous spectacle wear Yes/No

If yes, since how many years _________

Use of any sunglasses/tints Yes/No

History of using hat/turban/other sun protective (others) __________ during the work at farm field

Vision during work good/fair/poor

Difficulty with sunlight during work at farm field: Yes/No

Visual Symptoms: Headache/Eye strain/Eye pain

Ocular Symptoms: Redness/irritation/itching/dryness/ocular injury/foreign body sensation/Nil

-

Ocular injury during work: Yes/No

If yes, frequency of injury: Very often/on/off/rarely

Injury associated with _______________ particular task of farming

-

Non ocular injury during work: Yes/No

If yes, frequency of injury: Very often/on/off/rarely

Injury associated with _______________ particular task of farming

Do you associate with injury with poor vision Yes/No

Work-related musculoskeletal disorder (WMSD): Wrist/Hand/Neck/Shoulder pain/Lower back pain/Hip pain/Leg pain/General fatigue/Nil

REFERENCES

- 1.Department of agriculture and farmers welfare. Annual report 2021-2022. Available from: https://agricoop.nic.in/Documents/annual-report-2021-22.pdf. [Last accessed on 2023 Jan 07] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agriculture: A hazardous work. 2009. Available from: https://www.ilo.org/safework/areaso.fwork/hazardous-work/WCMS_110188/lang--en/index.htm . (Last accessed on 2023 on 2023 Jan 07]

- 3.Patel T, Pranav PK, Biswas M. Nonfatal agricultural work-related injuries: A case study from Northeast India. Work. 2018;59:367–74. doi: 10.3233/WOR-182693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Das B. Agricultural work related injuries among the farmers of West Bengal, India. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot. 2014;21:205–15. doi: 10.1080/17457300.2013.792287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ojha P, Singh A. Assessment of occupational health hazards among farm workers involved in agricultural activities. J Pharmacogn Phytochem. 2018;7:1369–72. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sil AK. “Save your eyes for thirty rupees”: A case study. Community Eye Health. 2017;30:S18–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chatterjee S, Agrawal D. Primary prevention of ocular injury in agricultural workers with safety eyewear. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2017;65:859–64. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_334_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Janani S, Dhanalakshmi S, Rashima A, Krishnakumar R, Santanam P P. Visual demand, visual ability and vision standards for hairdressers – An observational study from Chennai, Tamil Nadu. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2021;69:1369–74. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_2491_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ORC Macro. Mumbai: IIPS; 2000. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-2), India; pp. 1998–99. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chaudhuri SK, Jana S, Biswas J, Bandyopadhya M. Modes and impacts of agriculture related ocular injury. Int J Health Sci Res. 2014:108–11. [Google Scholar]

- 11.McLaughlin AC, Sprufera JF. Aging farmers are at high risk for injuries and fatalities: how human-factors research and application can help. North Carolina Med J. 2011;72:481–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kyriakaki ED, Symvoulakis EK, Chlouverakis G, Detorakis ET. Causes, occupational risk and socio-economic determinants of eye injuries: A literature review. Med Pharm Rep. 2021;94:131–44. doi: 10.15386/mpr-1761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]