Abstract

Intussusception is a common pediatric emergency that causes significant morbidity and mortality, particularly in low- to middle-income countries. The laparoscopic management of intussusception following failed non-invasive methods remains a topic of debate. This study aims to evaluate the long-term outcomes of minimally invasive approaches for intussusception. A retrospective analysis was conducted on patients who underwent minimally invasive surgery for intussusception between January 2016 and December 2020 at our institution. Data on patient demographics, pre-operative and intra-operative variables, immediate postoperative complications, length of hospital stay, and long-term results were collected. A total of 181 patients underwent minimally invasive surgery, including 117 boys (64.6%) and 64 girls (35.4%), with a median age of 8 months (range: 2–134). The median hospital stay was 4 days. Thirty-nine patients underwent trans-umbilical mini-open reduction (MO group), while 142 had laparoscopic exploration after failed air enema reduction. Among them, 40 had successful laparoscopic reduction (LAP group), and 102 required conversion to laparoscopic-assisted mini-open reduction (LAMO group). No intra-operative or immediate postoperative complications were observed. Recurrence occurred in 13 patients (7.2%) after a median follow-up of 43 months, with 6 patients (3.3%) requiring laparoscopic adhesiolysis due to bowel adhesions. In conclusion, minimally invasive surgery for intussusception is a safe and feasible approach with excellent long-term outcomes.

Keywords: Intussusception, Minimally invasive, Laparoscopic, Surgery, Pediatric

Subject terms: Gastrointestinal diseases, Paediatrics, Paediatric research

Introduction

Intussusception stands as the predominant cause of intestinal obstruction among children aged 3 months to 5 years, contributing significantly to morbidity and mortality rates1. The majority of occurrences manifest as ileocolic and can typically be resolved through air enema reduction, with a success rate of up to 95%2. Surgical intervention becomes necessary when pneumatic reduction fails or is contraindicated. Traditionally, manual open reduction requires a large right-sided transverse incision. However, with the evolution of minimally invasive techniques in pediatric surgery, the laparoscopic approach has gained momentum in intussusception management3,4. Laparoscopic reduction offers the advantage of reduced surgical trauma and shorter operative times compared to open reduction procedures5–7. Nonetheless, the adoption of laparoscopic treatment for intussusception remains a topic of controversy due to limited working space in children, as well as the variability in the location of the affected bowel segment among patients, thereby hindering widespread acceptance2. This study aims to explore the safety and feasibility of laparoscopic (LAP) and laparoscopic-assisted mini-open reduction (LAMO) techniques in the management of idiopathic intussusception in pediatric patients.

Materials and methods

After institutional review board and ethical committee approval, a retrospective review was performed to evaluate the outcomes of a minimally invasive approach for intussusception at the National Children’s Hospital of Pediatrics in Hanoi, Vietnam. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations (i.e., STROBE checklist).

Patients’ selection

Inclusion criteria

Patients diagnosed with idiopathic intussusception at the National Children’s Hospital between January 2016 and December 2020, confirmed by ultrasound, underwent fluoroscopy-guided air enema reduction.

Patients unresponsive to pneumatic reduction were indicated for surgery

Exclusion criteria

Patients with prior intussusception episodes, clinical instability indicating peritonitis or intestinal perforation, co-morbidities, known pathologic lead points, or complications during pneumatic reduction.

Surgical management

Patients deemed unsuitable for air enema reduction due to a grossly distended abdomen will be directed towards mini-open exploration and manual reduction (MO).

Patient failed pneumatic reduction would proceed to laparoscopic exploration and attempted reduction. If laparoscopy alone was insufficient in reducing the intussusceptum or when bowel resection was required, conversion to LAMO was initiated.

Operating technique

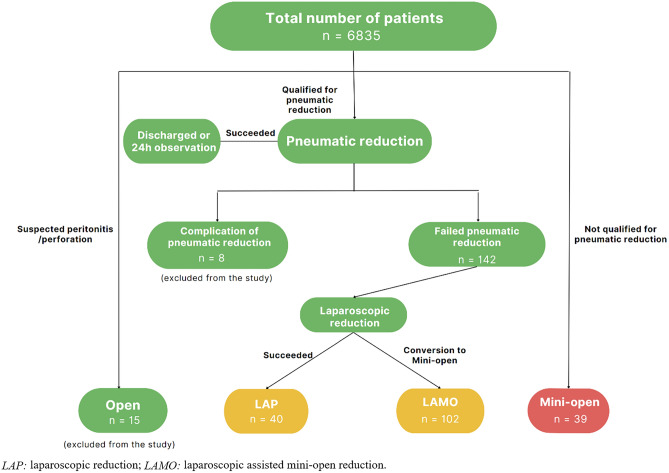

Laparoscopic exploration

Patients were administered general anesthesia and positioned supine.

A longitudinal trans-umbilical incision of 1 cm was made, and a 10 mm trocar was inserted for pneumoperitoneum. Laparoscopic exploration was performed using a 10 mm double-channel operating laparoscope equipped with an atraumatic grasper. If signs suggestive of intestinal perforation, bowel ischemia/necrosis, or the presence of a pathologic lead point were identified, conversion to LAMO was initiated. Otherwise, laparoscopic reduction was carried out with the insertion of two 5 mm working trocars. The position of these trocars usually depended on the location of the intussusceptum and the surface area of the child’s abdomen. In the majority of cases, trocars were inserted at the suprapubic and upper left or upper right abdomen (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Patient’s positioning: (a) Patient’s abdomen showing positioning of trocars. (b) 10 mm double-channel operating laparoscope equipped with a 5-mm atraumatic grasper. (c) The laparoscopic setup involved positioning the surgeon on the left side of the patient. (d) Invaginating the terminal ileum (intussusceptum) into the cecum (intussuscipiens).

The ascending colon was then manipulated to precisely locate the intussusceptum. Two atraumatic graspers were alternately used on the ascending colon to mobilize the intussusceptum, pushing it downward towards the cecum. Subsequently, the terminal ileum, along with its mesentery, was grasped and pulled outward and downward using the right grasper, while the left grasper pulled the neck of the intussusceptum in the opposite direction. Care was taken to maintain tension while pulling and to avoid damaging the bowel’s serosa or mesentery. If resistance was encountered, the terminal ileum could be held with the right-hand grasper while the left grasper widened the neck of the intussusceptum by repeatedly opening its jaws. Following reduction, the intestines were re-examined for necrosis and possible lead points. In cases where laparoscopic reduction alone was unsuccessful, or when there was a pathologic lead point or bowel resection was required, the intussusceptum was secured with grasping forceps and brought to the umbilicus for LAMO.

Trans-umbilical mini-open reduction (MO)

A 2 cm longitudinal trans-umbilical incision was made, and a skin retractor was inserted. The underlying fascia was divided superiorly and inferiorly along the linea alba. Upon opening the peritoneum, the actual length on the abdominal wall could be expanded up to 5 cm, while the skin incision remained at 2–3 cm (Fig. 2). If the abdominal opening was insufficient for exploration, the rectus muscle around the umbilicus could be laterally divided on both sides without cutting the skin. Once an adequate opening was achieved, the procedure commenced with the evacuation of the small intestine and manual extracorporeal decompression by squeezing the intestinal contents and pushing them towards the stomach for suction (Fig. 3). This step aimed to reduce tension and enhance visualization of the intussusception’s mass. Manual reduction of the intussusceptum was then performed, along with bowel resection and anastomosis if necessary. The skin was closed using 6–0 Vicryl interrupted subcuticular sutures to optimize cosmetic outcomes.

Fig. 2.

Trans-umbilical mini-open incision: Longitudinal division of underlying fascia superiorly (a) and inferiorly (b) without extending the skin incision.

Fig. 3.

Manual reduction: (a) Extracorporeal decompression was accomplished by manually squeezing the intestinal contents towards the stomach to facilitate suctioning. (b) The intussusceptum revealed after decompression. (c) Manual reduction coupled with identification of lead points and detection of bowel necrosis.

Postoperative management and follow up

Trial feeding commenced on the first day after surgery if no bowel resection was performed, and between days two and five if bowel resection was required, depending on the patient’s tolerance. Following discharge, patients underwent assessments at intervals of 1, 4 and 12 weeks postoperatively, followed by an annual visit. The postoperative complications were ranked according to the Clavien–Dindo classification.

Statistical analysis

Categorical data were presented as frequencies with percentages, and were tested using Fisher’s exact test or chi-square test where appropriated. Continuous data were represented as medians (interquartile ranges) or medians (ranges) for non-normally or normally distributed data, respectively, and were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, or Student’s t-test, as appropriate. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance.

Ethics declaration

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Vietnam National Children’s Hospital. The study was retrospectively registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (identifier NCT06351163) on April 5th, 2024. Written informed consent to participate in this study was waived by the ethics committee due to its retrospective nature, and the interventions are routine procedures at our institution. Informed consent was obtained from the patients’ legal guardians for the publication of information and/or images in an online open-access publication.

Results

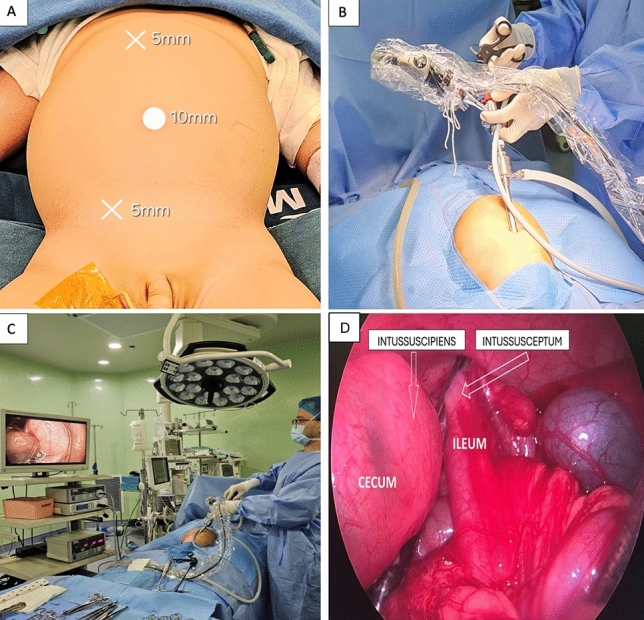

Between January 2016 and December 2020, a cohort of 6835 patients exhibiting clinical signs and symptoms of intussusception, along with positive ultrasound findings, were admitted to the emergency department of the Vietnam National Children’s Hospital. Fifteen patients in critical condition or suspected of bowel perforation and peritonitis were excluded from the study. Thirty-nine patients who did not meet the criteria for air enema reduction due to significant abdominal distension, were directed towards MO. The remaining patients underwent fluoroscopic guided air enema reduction up to three attempts, with laparoscopic exploration being indicated if air enema reduction failed (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Flow chart of pediatric intussusception management at our institution.

A total of 181 patients underwent minimally invasive surgery (LAP, LAMO and MO), including 117 boys (64.6%) and 64 girls (35.4%). The median age at the time of surgery was 8 months (range: 2–134), and the median hospital stay was 4 days (range: 2–31). Among the patients, 142 failed air enema reduction and underwent laparoscopic exploration. Of these, 40 patients successfully completed LAP, while conversion to LAMO was required in 102 patients. Bowel resection and anastomosis were performed in 29 out of 181 cases, with 6 in the MO group and 23 in the LAMO group. LAP exhibited the shortest operating time of 32 ± 17 min, while LAMO and MO had a mean operating time of 52 ± 30 and 58 ± 25 min, respectively. The shortest mean hospital stay (2.58 ± 1.43 days) was also observed in LAP, while LAMO and MO were 4.72 ± 2.87 days and 4.49 ± 4.27 days, respectively (p < 0.05). 3 cases in LAMO group had wound infection. No intra-operative or major immediate postoperative complications were encountered in all three groups. Following a median follow-up duration of 43 months, recurrence of intussusception occurred in 13 patients (7.2%), which could be managed by pneumatic reduction. Six patients (4.3%) developed bowel adhesions requiring laparoscopic adhesiolysis. None of the adhesion cases occurred in the LAP group, while 5 cases belonged to the MO group, with this difference being statistically significant. There was no statistical difference in the rate of recurrence between the 3 groups (p > 0.05). Outcomes of LAP, LAMO, and MO are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of outcomes between LAP, LAMO and MO approaches.

| Parameters | LAP (n = 40) | LAMO (n = 102) | MO (n = 39) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (months) | 11 | 8 | 7 | < 0.05 |

| Operating time (minutes) | 32 ± 17 | 52 ± 30 | 58 ± 25 | < 0.05 |

| Immediate postoperative complications | 0 | 3 cases with wound infections (Grade II) | 0 | 0.192 |

| Median time to feed (days) | 1 | 4 | 5 | < 0.05 |

| Mean hospital stays in days | 2.58 ± 1.43 | 4.72 ± 2.87 | 4.49 ± 4.27 | < 0.05 |

| Recurrence rate | 5/40 (12.5%) | 7/102 (6.9%) | 1/39 (2.6%) | 0.230 |

| Long-term complication rate | 0/40 (0%) | 1/102 (1%) | 5/39 (12.8%) | < 0.05 |

LAP: Laparoscopic reduction; LAMO: Laparoscopic assisted mini-open reduction; MO: Mini-open reduction.

There is no significant difference in terms of hospital stay, the need for bowel resection, recurrence and complication rate between the group greater than 36 months of age and less than 36 months of age (p > 0.05). Also, the long-term complication rate of patients had bowel resection versus no bowel resection was also similar (p > 0.05).

Discussion

A systematic review by Attoun et al. in 2023 recommended nonoperative therapy such as pneumatic reduction as the primary approach for pediatric intussusception due to its high success rate8. However, in cases of failed air enema reduction or contraindications, surgical intervention is required. Laparoscopic reduction of idiopathic intussusception was first documented in 1996, and since then, numerous authors have emphasized the use of minimally invasive procedures to avoid the necessity for laparotomy8,9. Nonetheless, literature regarding the safety and effectiveness of minimally invasive procedures in pediatric patients remains scarce. The aim of this study is to investigate the feasibility and long-term outcomes of laparoscopic and mini-open reduction at our institution.

The demographic characteristics of our study cohort, including a slight male predominance and a median age at surgery of 8 months, are consistent with existing literature1–7. Our findings, as illustrated in Table 1, demonstrate several significant advantages favoring LAP, such as shorter operating times, faster postoperative recovery evidenced by shorter hospital stays, and earlier resumption of feeding. These findings are in line with those reported by other authors1–4,6,7,10.

In our institution, air enema reduction is allowed up to 3 attempts. This practice aligns with the systematic review by the American Pediatric Surgical Association Outcomes and Evidence-Based Practice Committee, which suggests that repeated enema reductions may be attempted when clinically appropriate11. Our protocol involves initially proceeding to laparoscopic exploration following unsuccessful air enema reduction, rather than resorting to laparotomy immediately. The advantage of this approach is that injuries to bowel segments distant from the intussusceptum, due to air enema reduction attempts, or other abdominal pathologies and possible lead points can be detected laparoscopically. Our choice of prioritizing LAP after failed air enema reduction explained a high conversion rate from LAP to LAMO, which was 71.8% and surpassing rates observed in other studies1–3. Furthermore, owing to the substantial patient volume, approximately 1400 cases of pneumatic reduction annually, our surgical team has acquired considerable expertise in non-operative reduction techniques, thereby reserving laparoscopic exploration for only the most intricate cases. Additionally, it is debatable that our “conversion” is not actual conversion, as conventional laparotomy was not required in any of the cases; instead, a laparoscopic-assisted trans-umbilical mini-open approach was adopted.

The absence of intraoperative complications in both the LAP and LAMO groups highlights the safety and feasibility of minimally invasive techniques in pediatric patients. Although the immediate postoperative complication rates were higher in the LAMO and MO groups than in LAP, primarily due to wound infections, the difference was not statistically significant. Additionally, this study showed no statistical difference in recurrence rates between LAP, LAMO, and MO, which was similar to studies by other authors1,6,12. However, the rate of bowel adhesions requiring intervention was significantly lower in the LAP and LAMO groups compared to the MO group, suggesting potential benefits of the laparoscopic approach in terms of long-term postoperative morbidity.

It was also noted that there was a statistical difference between the mean age of LAP patients compared to the other two groups. This could be because larger patients would be more likely to tolerate pneumoperitoneum and have more intra-abdominal space to successfully perform reduction. Our findings align with the National Inpatient Database in Japan, which also showed that patients in the laparoscopic surgery group were older13. Moreover, it has been reported by some study that patients over 3 years of age have a higher probability of intestinal resection2. However, our study showed there is no significant difference in terms of hospital stay, the need for bowel resection, recurrence and complication rate between the group greater than 36 months of age and less than 36 months of age (p > 0.05). Also, the long-term complication rate of the group had bowel resection versus no bowel resection was also similar (p > 0.05).

Large cohort studies, including the one by Takamoto et al. using a Japanese nationwide inpatient database13, and meta-analyses such as the one conducted by Wu et al., also support the feasibility, safety, and effectiveness of laparoscopic surgery in pediatric intussusception14. Regarding the trans-umbilical reduction technique, Li et al. in 2021 was the first to report intussusception reduction through an umbilical incision, with a success rate similar to that of LAP15. This approach requires no laparoscopic instruments, and the incision site can be extended laterally in cases where reduction is challenging, or resection of necrotic intestine is necessary15. However, our study favored a different incision approach, extending the fascia and peritoneum incision longitudinally along the linea alba. Conventional laparotomy was not required in any of our patients.

Appendectomy was occasionally performed in this cohort study, depending on the surgeon’s preferences. Our literature review reveals conflicting opinions on this practice. Delgado-Miguel et al. found no significant differences between groups with and without appendectomy16. Conversely, Liu et al. observed that incidental appendectomy is associated with longer operation times and higher total costs, suggesting insufficient evidence to recommend appendectomy during laparoscopic intussusception treatment17. Additionally, ileopexy was also performed in some patients in this study, based on the surgeon’s preference. This approach is supported by a recent study by Zhang et al. which demonstrated that laparoscopic ileopexy significantly reduces the risk of recurrence18. Li et al. also concluded that early preventive laparoscopic ileopexy should be considered for patients with multiple recurrences21. However, Wei et al. argued that ileopexy offers no benefit in preventing recurrence and results in longer operation times3. Unfortunately, due to the retrospective nature of this study, we lack data to identify and compare the outcomes of the appendectomy and ileopexy groups versus the non-appendectomy and non-ileopexy groups.

To the best of our knowledge, our cohort study represents one of the largest single-center investigations, as illustrated in Table 2, concerning the long-term outcomes of minimally invasive surgical interventions for intussusception. In general, our recurrence and long-term complication rates were either equivalent to or better than those reported in the literature1–12,14,15,19,22.

Table 2.

Comparative analysis with existing literature.

| Author, year published | Number of OPEN | Number of LAP/LAMO |

|---|---|---|

| This study | 39 | 142 |

| Zhao et al.1 | 100 | 62 |

| Li et al.2 | 0 | 65 |

| Jamshidi19 | 26 | 26 |

| Li et al.15 | 27 | 24 |

| Benedict12 | 18 | 63 |

| Houben10 | 7 | 37 |

| Wei3 | 35 | 23 |

| Sklar7 | 23 | 5 |

| Hill6 | 27 | 65 |

LAP: Laparoscopic reduction; LAMO: Laparoscopic assisted mini-open reduction; MO: Mini-open reduction.

However, it is essential to acknowledge the limitations of our study. Firstly, its retrospective design and single-center experience may limit the generalizability of our findings. Secondly, the lack of statistically significant differences in outcomes between the LAMO, LAP, and MO groups might be due to the study being underpowered because of the relatively small number of subjects in each group and the low occurrence rate of complications. Thirdly, the study does not apply randomization in the selection of patients for different surgical approaches, leading to potential bias in treatment selection. Factors such as surgeon preference, patient condition, or hospital resources could influence which surgical method was used, thus affecting the outcomes. Additionally, there may be potential variability in the surgeons’ expertise or experience with laparoscopic versus open surgery. Surgeon skill could significantly impact the outcomes, especially in minimally invasive techniques. Lastly, there was a potential confounding factor in cases where bowel resection was performed. As no bowel resections were performed in the LAP group, the differences in outcomes between the LAP group and the other groups, such as time to feed and hospital stay, could be attributed to bowel resection rather than the surgical approach.

Conclusion

Minimally invasive surgery for intussusception is a safe and feasible approach with excellent long-term outcome. Bowel resection and anastomosis could be performed by mini-open technique through trans-umbilical incision, which provided a better cosmetic result than conventional laparotomy.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Dr. Tam, Dr. Kien, Dr Tho Anh, Dr Son and Dr Du from the Surgery Department, the National Hospital of Pediatrics, for their support in this work.

Author contributions

Dr. NTQ led the conceptualization, supervision, methodology, validation, and original draft writing. Assoc. Prof. PDH led resources, visualization and participated in investigation. DTT led project administration and shared investigation responsibilities. LBD led formal analysis and data curation. NVML and Prof. NTL contributed equally to writing, investigation, and editing, with Prof. NTL also sharing equal responsibility in methodology and validation. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final manuscript version.

Funding

No funding was received for this article.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to sensitive patient’s information but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These First Authors contributed equally to this work: Thanh Quang Nguyen and Duy Hien Pham.

References

- 1.Zhao, J., Sun, J., Li, D. & Xu, W. J. Laparoscopic versus open reduction of idiopathic intussusception in children: An updated institutional experience. BMC Pediatr22(1), 44 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li, S. M., Wu, X. Y., Luo, C. F. & Yu, L. J. Laparoscopic approach for managing intussusception in children: Analysis of 65 cases. World J. Clin. Cases10(3), 830–839 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wei, C. H., Fu, Y. W., Wang, N. L., Du, Y. C. & Sheu, J. C. Laparoscopy versus open surgery for idiopathic intussusception in children. Surg. Endosc.29(3), 668–672 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang, P. C. Y., Duh, Y. C., Fu, Y. W., Hsu, Y. J. & Wei, C. H. Single-incision laparoscopic surgery for idiopathic intussusception in children: Comparison with conventional laparoscopy. J. Pediatr. Surg.54(8), 1604–1608 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bailey, K. A., Wales, P. W. & Gerstle, J. T. Laparoscopic versus open reduction of intussusception in children: A single-institution comparative experience. J. Pediatr. Surg.42(5), 845–848 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hill, S. J., Koontz, C. S., Langness, S. M. & Wulkan, M. L. Laparoscopic versus open reduction of intussusception in children: Experience over a decade. J. Laparoendosc Adv. Surg. Tech. A23(2), 166–169 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sklar, C. M., Chan, E. & Nasr, A. Laparoscopic versus open reduction of intussusception in children: A retrospective review and meta-analysis. J. Laparoendosc Adv. Surg. Tech. A24(7), 518–522 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Attoun, M. A. et al. The management of intussusception: A systematic review. Cureus15(11), e49481 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cuckow, P. M., Slater, R. D. & Najmaldin, A. S. Intussusception treated laparoscopically after failed air enema reduction. Surg. Endosc.10(6), 671–672 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Houben, C. H., Feng, X. N., Tang, S. H., Chan, E. K. W. & Lee, K. H. What is the role of laparoscopic surgery in intussusception?. ANZ J. Surg.86(6), 504–508 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelley-Quon, L. I. et al. Management of intussusception in children: A systematic review. J. Pediatr. Surg.56(3), 587–596 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benedict, L. A. et al. The laparoscopic versus open approach for reduction of intussusception in infants and children: An updated institutional experience. J. Laparoendosc Adv. Surg. Tech A.28(11), 1412–1415 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takamoto, N. et al. Outcomes following laparoscopic versus open surgery for pediatric intussusception: Analysis using a national inpatient database in Japan. J. Pediatr. Surg.58(11), 2255–2261 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu, P. et al. Laparoscopic versus Open reduction of intussusception in infants and children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Pediatr. Surg.32(6), 469–476 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li, N. et al. Open transumbilical intussusception reduction in children: A prospective study. J. Pediatr. Surg.56(3), 597–600 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delgado-Miguel, C. et al. Incidental appendectomy in surgical treatment of ileocolic intussusception in children. Is it safe to perform?. Cir. Pediatr.35(4), 165–171 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu, T. et al. A retrospective study about incidental appendectomy during the laparoscopic treatment of intussusception. Front Pediatr.10, 966839 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang, Y. et al. Laparoscopic ileopexy versus laparoscopic simple reduction in children with multiple recurrences of ileocolic intussusception: A single-institution retrospective cohort study. J. Laparoendosc Adv. Surg. Tech. A.30(5), 576–580 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jamshidi, M., Rahimi, B. & Gilani, N. Laparoscopic and open surgery methods in managing surgical intussusceptions: A randomized clinical trial of postoperative complications. Asian J. Endosc. Surg.15(1), 56–62 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loukas, M. et al. Intussusception: An anatomical perspective with review of the literature. Clin. Anat.24(5), 552–561 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li, B., Sun, C. X., Chen, W. B. & Zhang, F. N. Laparoscopic ileocolic pexy as preventive treatment alternative for ileocolic intussusception with multiple recurrences in children. Surg. Laparosc. Endosc. Percutan. Tech.28(5), 314–317 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang, J. et al. Liberal surgical laparoscopy reduction for acute intussusception: Experience from a tertiary pediatric institute. Sci. Rep.14(1), 457 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to sensitive patient’s information but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.