Abstract

Purpose

Advances in cancer detection and treatment have extended cancer survivors’ (CSs) life expectancy, but their evolving health needs remain unmet. This study analyzes 14 patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) for CSs with non-cutaneous cancers using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) framework. These 14 PROMs are derived from a recent review focusing on the implementation of the routine assessment of unmet needs in cancer survivors.

Methods

Each PROM was examined for correspondence to ICF health and functioning dimensions. Two independent reviewers extracted meaningful concepts from each PROM item, linking them to ICF categories. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion with a third expert reviewer.

Results

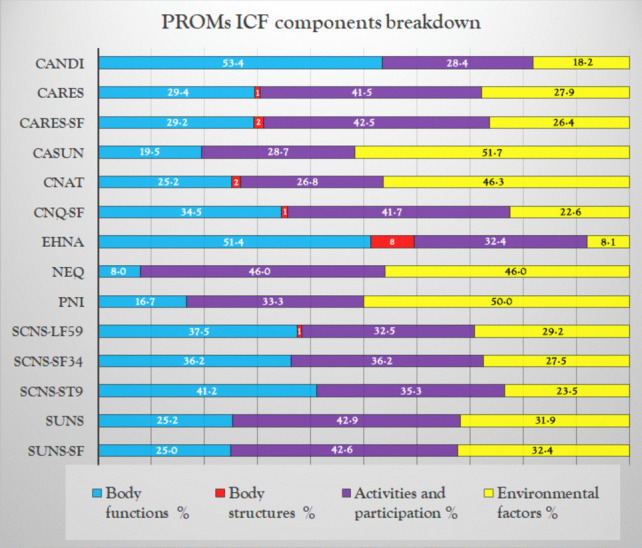

PROMs varied in ICF component correspondence, with “Activities and Participation” (37.2%) and “Environmental Factors” (31.8%) most frequently represented, highlighting their significance. “Body Structures” (1%) received minimal attention, suggesting its limited relevance to CSs’ needs. The results of the linking process show the differences between the various PROMs: Candi and eHNA were primarily linked to “Body Function” (53.4% and 51.4%, respectively), NEQ and SUN to “Activities and Participation,” and CaSUN and PNI to “Environmental Factors” (51.7% and 50%, respectively), while eHNA had the highest percentage of items linked to “Body Structures” (8.1%).

Conclusions

This evaluation of PROMs enhances the understanding of CSs’ diverse needs so as to address them, thereby improving these individuals’ quality of life.

Implications for cancer survivors

The study underscores the importance of addressing “Activities and Participation” and “Environmental Factors” in PROMs for CSs. These insights support developing comprehensive PROMs and help healthcare providers prioritize critical areas of survivorship care, ultimately enhancing CSs’ well-being.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00520-024-09019-8.

Keywords: Oncology; Needs; International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health; Rehabilitation outcome; Patient-reported outcome measures; Quality of life

Introduction

Up to a few decades ago, cancer was often regarded as an incurable disease. However, due to advances in early diagnosis and treatment, many forms of cancer are now considered manageable conditions, allowing individuals to have a life expectancy not significantly different from that of the general population [1]. These individuals are referred to as cancer survivors (CSs). The currently accepted international definition of CS includes not only those individuals in the post-treatment phase but also those undergoing active therapy, those in remission, those for whom the disease has assumed chronic characteristics, and those who have recovered [2]. Given the increasing number of CSs, it is essential to comprehend their evolving health needs as their unmet needs, i.e., needs not addressed by the health and social care systems, may impact their quality of life and the demand for services [3–5].

Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) can be used to assess patients’ unmet needs. The inclusion of PROMs in routine clinical practice can foster communication between patients and clinicians, improving patient outcomes, and facilitate optimal delivery of supportive care and health service outcomes [6].

When implementing PROMs in practice, clinicians must pay particular attention to both the methodological robustness and the feasibility of the available tools. In this regard, a recent systematic review conducted a search for PROMs specifically designed to capture the unmet needs of CSs [7]. The review adopted the COSMIN methodology to critically evaluate these measures, providing a detailed description of their measurement properties as well as guidance for selecting those that reliably reflect the outcome to be examined.

However, since cancer survivors’ unmet needs are quite heterogeneous, clinicians should not base their choice solely on the psychometric characteristics of a particular tool; instead, they should prioritize which outcomes are important in a given population [8].

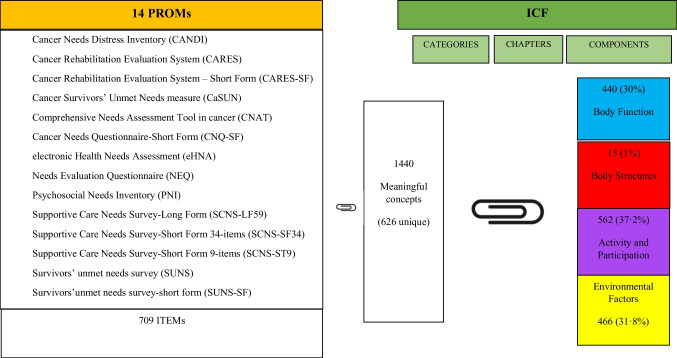

This study reliably linked the content of the PROMs included in Contri et al.’s review to the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) [7, 9]. That review identified 14 PROMs that serve as the starting point of our linking process, with the list of scales shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Linking process

The ICF provides a universal and internationally recognized framework and taxonomy for comprehensively describing an individual’s functioning profile, which in turn permits a better understanding of that person’s specific needs. Providing a shared language to enhance communication among stakeholders, the ICF makes it possible to compare contents across domains evaluated by different PROMs designed to capture the unmet needs of CSs as well as to identify any overlaps or gaps [10]. The current study’s results allow for a comprehensive understanding of the specific areas addressed by these PROMs and facilitate the selection of the most suitable tool based on the outcome domains to be addressed.

This study consists of an ICF-based analysis of the PROMs that assess the unmet needs of adult CSs suffering from non-cutaneous cancers in order to describe their content and the domains evaluated.

Methods

A linking process was conducted to evaluate the extent to which the PROMs assessing the unmet needs of adult CSs cover the spectrum of health-related outcomes and determinants outlined by the ICF [11, 12].

Based on the above-mentioned systematic review that our group recently conducted, 14 PROMs that reliably assess the unmet needs of adult CSs with non-cutaneous cancers were selected for analysis (Box 1).

Box 1 PROMs used in the linking process.

| • Cancer Needs Distress Inventory (CANDI) is designed to identify distressed patients in need of intervention, assessing 7 domains: Depression, Anxiety, Emotion, Social, Healthcare, Practical, and Physical. It consists of 39 items, with scores ranging from 39 to 195 |

| • Cancer Rehabilitation Evaluation System (CARES) is designed to assess the day-to-day problems and rehabilitation needs of patients with cancer, assessing 5 domains: Physical, Psychosocial, Medical Interaction, Marital, Sexual. It consists of 139 items, with scores ranging from 0 to 556 |

| • Cancer Rehabilitation Evaluation System – Short Form (CARES-SF) is designed to assess the day-to-day problems and rehabilitation needs of patients with cancer, assessing 5 domains: Physical, Psychosocial, Medical Interaction, Marital, Sexual (+ 1 Miscellaneous subscale). It consists of 59 items, with scores ranging from 0 to 236 |

| • Cancer Survivors’ Unmet Needs measure (CaSUN) is designed to identify cancer survivors’ supportive care needs, assessing 5 domains: Existential survivorship, Comprehensive care, Information, Quality of life, Relationships. It consists of 35 items, with scores ranging from 0 to 35 |

| • Comprehensive Needs Assessment Tool in cancer (CNAT) is designed to cover cancer patients' needs in a comprehensive way throughout all phases of the cancer experience, from diagnosis to recovery or palliative care, with 8 domains: Information, Psychological problems, Health care staff, Physical symptoms, Hospital facilities and service, Family/interpersonal problems, Spiritual/religious concerns, Social support. It consists of 59 items, with scores ranging from 0 to 100 |

| • Cancer Needs Questionnaire-Short Form (CNQ-SF) is designed to assess cancer patient's needs across several domains, assessing 5 domains: Psychological, Health information, Physical and daily living, Patient care and support, Interpersonal communication needs. It consists of 32 items, with scores ranging from 0 to 100 |

| • electronic Health Needs Assessment (eHNA) is designed to help people living with cancer express all their needs and help those helping them better target support, assessing 5 domains: Physical, Practical, Social, Emotional, Spiritual. It consists of 48 items, with scores ranging from 0 to 480 |

| • Needs Evaluation Questionnaire (NEQ) is designed to evaluate needs expressed by cancer patients, assessing 5 domains: Informative needs, Needs related to assistance/care, Material needs, Needs for a psychoemotional support, Relational needs. It consists of 23 items, with scores ranging from 0 to 23 |

| • Psychosocial Needs Inventory (PNI) is designed to identify the psychosocial needs of cancer patients, and the contributory factors to need, assessing 7 domains: Needs associated with health professionals, Information needs, Needs related to Social support networks, Identity needs, Emotional and Spiritual needs, Practical needs, Need for childcare. It consists of 48 items, with scores ranging from 0 to 240 (section A) and from 48 to 480 (section B) |

| • Supportive Care Needs Survey-Long Form (SCNS-LF59) is designed to assess the generic needs of patients with cancer, assessing 5 domains: Psychologic, Health system and information, Physical and daily living, Patient care and support, Sexuality. It consists of 59 items, with scores ranging from 0 to 100 |

| • Supportive Care Needs Survey-Short Form 34-items (SCNS-SF34) is designed to measure cancer patients' perceived needs across a range of domains, assessing 5 domains: Psychologic, Health system and information, Physical and daily living, Patient care and support, Sexuality. It consists of 34 items, with scores ranging from 1 to 100 |

| • Supportive Care Needs Survey-Short Form 9-items (SCNS-ST9) is designed to assess the perceived needs of people with cancer, assessing 5 domains: Psychologic, Health system and information, Physical and daily living, Patient care and support, Sexuality. It consists of 9 items, with scores ranging from 2 to 100 |

| • Survivor Unmet Needs Survey (SUNS) is designed to assess the generic needs of patients with cancer, assessing 5 domains: Emotional Health, Access and Continuity of Care, Relationships, Financial Concerns, Information. It consists of 89 items, with scores ranging from 0 to 356 |

| • Survivor Unmet Needs Survey-short form (SUNS-SF) is designed to assess the generic needs of patients with cancer, assessing 4 domains: Information, Financial concerns, Access and continuity of care, Relationships and Emotional health. It consists of 30 items, with scores ranging from 0 to 120 |

All items from these PROMs were entered into Microsoft Excel 365 [7]. Then, using the updated linking rules by Cieza et al., two independent reviewers (Reviewer 1: MS, occupational therapist; Reviewer 2: AC, physical therapist) extracted the meaningful concepts from each item and linked them to the ICF [13–15]. The meaningful concepts were first categorized based on the ICF components (“Body Functions,” “Body Structures,” “Activities and Participation,” and “Environmental Factors”), chapters, and related categories. The linking process was then performed within each category at the most appropriate and precise ICF hierarchical level (e.g., second or third level). Disagreements were resolved through discussion and consultation with a third reviewer (SC), a physical therapist with extensive clinical expertise in cancer rehabilitation. Additionally, a fourth reviewer specialized in the taxonomy of psychological aspects in cancer care (IB) was consulted to standardize the linking process for meaningful concepts that, depending on the context, could be construed as more an emotional rather than a cognitive aspect.

The agreement between reviewers was examined using Kappa statistics. A Kappa statistic of 0·6 or higher was considered indicative of substantial agreement. Detailed information about the linking process is provided in the Repository [16, 17].

A comprehensive framework was developed to assess how thoroughly each PROM addressed the four ICF components through a descriptive analysis of the frequency of distribution of the ICF components, chapters, and categories.

Results

The 14 selected PROMs contained a total of 709 items which, altogether, accounted for 1440 meaningful concepts. Overall, 626 of them were unique meaningful concepts, which were linked to 205 different ICF categories across all four ICF components (Fig. 1).

Meaningful concepts

During the linking process, the two reviewers initially agreed on 420 meaningful concepts (67·1%). After discussion with the third reviewer, 76 meaningful concepts (12·1%) were accepted as initially identified by Reviewer 1, and 92 meaningful concepts (14·7%) were accepted as initially attributed by Reviewer 2. For the remaining 38 meaningful concepts (6·1%), the reviewers chose alternate codes after discussion.

The top five meaningful concepts extracted from the 709 items were help (extracted 56 times), dealing with (extracted 55 times), information (extracted 46 times), feeling (extracted 43 times), and care (extracted 33 times), as shown in Fig. 1A in the appendix.

ICF component linking

The majority of the meaningful concepts were linked to the ICF components of “Activities and Participation” and “Environmental Factors,” as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

The top four ICF chapters and related categories

| Component | Chapter and categories | Links |

|---|---|---|

| Activities and Participation | General tasks and demands > d240 handling stress and other psychological demands > d2408 other specified handling stress and other psychological demands | 94 |

| Environmental Factors | Support and relationships > e355 health professionals | 72 |

| Environmental Factors | Services, systems and policies > e580 health services, systems and policies > e5800 health services | 54 |

| Activities and Participation | Major life areas > economic life | 52 |

Table 1A in the appendix shows the full list of links to the ICF, with their frequencies.

Overall, the “Activities and Participation” component was the most represented, accounting for 37·2% of all the linkages, followed by “Environmental Factors” (31·8%) and “Body Functions” (29·8%). The “Body Structure” component was minimally represented, accounting for only 1% of the linkages made and addressed in only six out of 14 PROMs.

The PROMs varied significantly in their representation of ICF components.

The “Activities and Participation” component was the most prominent in PROMs like SUNS (42·9% of its links), the SUNS-SF (42·6%), and the CARES-SF (42·5%). The PROMS that focus primarily on the “Environmental Factors” component are the CaSUN (51·7%) and the PNI (50·0%), while the CaNDI and eHNA best represent the “Body Functions” component (53·4 and 51·4% of all links, respectively).

eHNA had the highest number of items linked to “Body Structure” (8.1%), while CARES, CARE-SF, CNAT, CNQ-SF, and SCNS-LF59 had the most 2%. The other eight PROMs had no items linked to the “Body Structure” component.

The ICF components for the 14 PROMs that assess the unmet needs of adult CSs suffering from non-cutaneous cancers are represented in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Breakdown of ICF components in the PROMs analyzed

Table 2 presents the distribution of links to ICF chapters for each PROM. Although the linking process was performed at the most appropriate ICF hierarchical level, data are here presented at the ICF chapter level to allow for an immediate comparison between the representation of ICF chapters and each PROM.

Table 2.

The first column presents the different ICF chapters grouped by components. The following columns provide the absolute and relative frequencies of linking to chapters at the PROM level and for the 14 PROMs analyzed overall

| PROM | CaSUN | SUN-SF | CARES-SF | CaNDI | SCNS-LF59 | SCNS-SF34 | SCNS-ST9 | CARES | CNQ-SF | SUNS | CNAT | eHNA | NEQ | PNI | Tot | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICF chapter | n° | % | n° | % | n° | % | n° | % | n° | % | n° | % | n° | % | n° | % | n° | % | n° | % | n° | % | n° | % | n° | % | n° | % | n° | % |

| Body functions | 17 | 19·5 | 17 | 25·0 | 31 | 29·2 | 48 | 53·4 | 43 | 37·5 | 23 | 33·8 | 7 | 41·2 | 80 | 29·3 | 29 | 34·5 | 53 | 25·2 | 31 | 25·2 | 38 | 51·4 | 4 | 8·0 | 16 | 16·7 | 440 | 30·0 |

| Mental functions | 15 | 17·2 | 17 | 25·0 | 19 | 18·1 | 37 | 42·5 | 36 | 23·2 | 20 | 30·3 | 7 | 41·2 | 54 | 14·1 | 24 | 29·6 | 49 | 16·3 | 21 | 17·4 | 19 | 25·7 | 2 | 4·0 | 15 | 11·8 | 335 | 23·1 |

| Sensory functions and pain | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1·0 | 1 | 1·1 | 2 | 1·3 | 1 | 1·5 | - | - | 6 | 1·6 | 1 | 1·2 | - | - | 3 | 2·5 | 4 | 5·4 | 1 | 2·0 | - | - | 20 | 1·4 |

| Voice and speech functions | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1·4 | - | - | - | - | 1 | 0·1 |

| Functions of the cardiovascular· hematological·immunological and respiratory systems | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1·1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 0·3 | - | - | 2 | 0·7 | 2 | 1·6 | 2 | 2·7 | - | - | - | - | 8 | 0·6 |

| Functions of the digestive· metabolic and endocrine systems | - | - | - | - | 9 | 8·6 | 5 | 5·7 | 2 | 1·3 | - | - | - | - | 11 | 2·9 | - | - | - | - | 4 | 3·3 | 9 | 12·2 | 1 | 2·0 | - | - | 41 | 2·8 |

| Genitourinary and reproductive functions | 2 | 2·3 | - | - | 1 | 1·0 | 2 | 2·3 | 1 | 0·6 | 1 | 1·5 | - | - | 5 | 1·3 | - | - | - | - | 1 | 0·8 | 2 | 2·7 | - | - | 1 | 0·8 | 16 | 1·1 |

| Neuromusculoskeletal and movement-related functions | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 0·6 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2 | 2·5 | 2 | 0·7 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 5 | 0·3 |

| Functions of the skin and related structures | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2 | 0·5 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1·4 | - | - | - | - | 3 | 0·2 |

| Activities and participation | 25 | 28·7 | 29 | 42·6 | 45 | 42·5 | 25 | 28·4 | 40 | 32·5 | 25 | 36·8 | 6 | 35·3 | 114 | 41·8 | 35 | 41·7 | 90 | 42·9 | 33 | 26·8 | 24 | 32·4 | 23 | 46·0 | 32 | 33·3 | 546 | 37·2 |

| Learning and applying knowledge | 2 | 2·3 | - | - | 1 | 1·0 | 3 | 3·4 | 2 | 1·7 | 1 | 1·5 | - | - | 2 | 0·7 | 1 | 1·2 | 7 | 3·3 | 3 | 2·4 | 1 | 1·3 | 2 | 4·0 | 3 | 3·1 | 28 | 1·9 |

| General tasks and demands | 7 | 8·0 | 13 | 19·1 | 2 | 1·9 | 6 | 6·9 | 7 | 6·0 | 2 | 3·0 | 1 | 5·9 | 3 | 1·1 | 21 | 25·9 | 49 | 23·3 | 2 | 1·6 | 2 | 2·7 | - | - | 6 | 6·3 | 121 | 8·3 |

| Communication | 2 | 2·3 | 3 | 4·4 | 13 | 12·4 | 3 | 3·4 | 14 | 12·1 | 10 | 15·2 | 2 | 11·8 | 32 | 11·8 | 8 | 9·9 | 11 | 5·2 | 15 | 12·2 | 2 | 2·7 | 11 | 22·0 | 8 | 8·3 | 134 | 9·2 |

| Mobility | - | - | - | - | 3 | 2·9 | 1 | 1·1 | 1 | 0·9 | - | - | - | - | 8 | 2·9 | - | - | 1 | 0·5 | 1 | 0·8 | 3 | 4·0 | - | - | 2 | 2·1 | 20 | 1·4 |

| Self-care | 3 | 3·4 | 2 | 2·9 | 2 | 1·9 | 4 | 4·6 | 7 | 6·0 | 6 | 9·1 | 2 | 11·8 | 5 | 1·8 | 1 | 1·2 | 2 | 1·0 | 4 | 3·3 | 3 | 4·0 | 3 | 6·0 | 1 | 1·0 | 45 | 3·1 |

| Domestic life | - | - | 1 | 1·5 | 4 | 3·8 | 3 | 3·4 | 1 | 0·9 | 1 | 1·5 | - | - | 9 | 3·3 | 1 | 1·2 | 2 | 1·0 | 2 | 1·6 | 4 | 5·3 | 2 | 4·0 | 2 | 2·1 | 32 | 2·2 |

| Interpersonal interactions and relationships | 6 | 6·9 | 5 | 7·4 | 14 | 13·3 | - | - | 3 | 2·6 | 3 | 4·5 | 1 | 5·9 | 43 | 15·8 | 1 | 1·2 | 7 | 3·3 | 1 | 0·8 | 3 | 4·0 | 4 | 8·0 | 4 | 4·2 | 95 | 6·5 |

| Major life areas | 3 | 3·4 | 5 | 7·4 | 6 | 5·7 | 3 | 3·4 | 1 | 0·9 | - | - | - | - | 8 | 2·9 | - | - | 9 | 4·3 | 3 | 2·4 | 3 | 4·0 | - | - | 1 | 1·0 | 42 | 2·9 |

| Community· social and civic life | 2 | 2·3 | - | - | - | - | 2 | 2·3 | 3 | 2·6 | 2 | 3·0 | - | - | 4 | 1·5 | 2 | 2·5 | 2 | 1·0 | 2 | 1·6 | 3 | 4·0 | 1 | 2·0 | 5 | 5·2 | 28 | 1·9 |

| Environmental factors | 45 | 51·7 | 22 | 32·4 | 28 | 26·4 | 16 | 18·2 | 35 | 29·2 | 20 | 29·4 | 4 | 23·5 | 76 | 27·8 | 19 | 22·6 | 67 | 31·9 | 57 | 46·3 | 6 | 8·1 | 23 | 46·0 | 48 | 50·0 | 466 | 31·8 |

| Products and technology | - | - | - | - | 7 | 6·7 | 3 | 3·4 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 16 | 5·9 | 0 | 0·0 | 1 | 0·5 | 1 | 0·8 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 28 | 1·9 |

| Natural environment and human-made changes to environment | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Support and relationships | 26 | 29·9 | 5 | 7·4 | 16 | 15·2 | 7 | 8·0 | 16 | 13·8 | 8 | 10·6 | 2 | 11·8 | 45 | 16·2 | 7 | 8·6 | 20 | 9·5 | 20 | 16·3 | 4 | 5·3 | 11 | 20·0 | 27 | 28·1 | 211 | 14·5 |

| Attitudes | 2 | 2·3 | - | - | 1 | 1·0 | - | - | 3 | 2·6 | 2 | 3·0 | 1 | 5·9 | 2 | 0·7 | 3 | 3·7 | 8 | 3·8 | 3 | 2·4 | - | - | 3 | 6·0 | 5 | 4·2 | 32 | 2·2 |

| Services· systems and policies | 17 | 19·5 | 17 | 25·0 | 4 | 3·8 | 6 | 6·9 | 16 | 13·8 | 10 | 15·2 | 1 | 5·9 | 14 | 5·1 | 9 | 11·1 | 38 | 18·1 | 33 | 26·8 | 2 | 2·7 | 10 | 20·0 | 17 | 17·7 | 194 | 13·4 |

| Body structures | 0 | - | 0 | - | 2 | 1·9 | 0 | - | 1 | 0·8 | 0 | - | 0 | - | 3 | 1·1 | 1 | 1·2 | 0 | - | 2 | 1·6 | 6 | 8·1 | 0 | - | 0 | - | 15 | 1·0 |

| Structures of the nervous system | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 0·8 | 1 | 1·3 | - | - | - | - | 2 | 0·1 |

| The eye, ear, and related structures | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Structures involved in voice and speech | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Structures of cardiovascular· immunological and respiratory systems | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Structures related to the digestive· metabolic and endocrine systems | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1·3 | - | - | - | - | 1 | 0·1 |

| Structures related to the genitourinary and reproductive systems | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Structures related to movement | - | - | - | - | 2 | 1·9 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2 | 0·7 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 3 | 4·0 | - | - | - | - | 7 | 0·5 |

| Skin and related structures | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 0·4 | - | - | - | - | 1 | 0·8 | 1 | 1·3 | - | - | - | - | 6 | 0·4 |

The appendix contains Figs. 2A-15A, which graphically present the results of the linking process for each PROM.

Variability within ICF components

Variability was also observed within ICF components. For example, within “Activities and Participation,” the chapter “Communication,” which is about general and specific features of communicating by means of language, signs, and symbols, accounted for 24·6% of the links, while “General tasks and demands,” which concerns general aspects of carrying out single or multiple tasks, organizing routines, or handling stress, represented 22·2% of the links. Similarly, within “Environmental Factors,” the chapter “Support and relationships,” which is about people or animals that provide practical, physical, or emotional support, nurturing, protection, and/or assistance, accounted for 46·3% of links, and “Services systems and policies,” which concerns services that provide benefits, systems designed to organize those services, and policies that govern systems, represented 41·7% of the links. For the “Body Functions” component, “Mental functions,” which concerns functions of the brain, was the most frequently linked chapter, accounting for 77·9% of the links, followed by “Functions of the digestive, metabolic, and endocrine systems,” which is about functions of ingestion, digestion, and elimination as well as functions involved in metabolism and the endocrine glands, representing 9·6% of the links. In the “Body Structures” component, “Structures related to movement” was the most commonly linked chapter, accounting for 53·8% of the links, while “Skin and related structures” accounted for 23·1%.

Table 3 shows the chapters included in each ICF component and the summary of their linking to the items extracted from the 14 PROMs selected for this study.

Table 3.

ICF component and the summary of their linking to the items extracted from the 14 PROMs

| Chapter | Frequency in the 14 PROMs | % | % of chapter in the component |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activities and Participation | |||

| Communication | 134 | 9·2 | 24·6 |

| General tasks and demands | 121 | 8·3 | 22·2 |

| Interpersonal interactions and relationships | 95 | 6·5 | 17·4 |

| Self-care | 45 | 3·1 | 8·3 |

| Domestic life | 32 | 2·2 | 5·9 |

| Major life areas | 42 | 2·9 | 7·7 |

| Community, social, and civic life | 28 | 1·9 | 5·1 |

| Learning and applying knowledge | 28 | 1·9 | 5·1 |

| Mobility | 20 | 1·4 | 3·7 |

| Environmental Factors | |||

| Support and relationships | 211 | 14·5 | 45·4 |

| Services, systems, and policies | 194 | 13·4 | 41·7 |

| Attitudes | 32 | 2·2 | 6·9 |

| Products and technology | 28 | 1·9 | 6·0 |

| Natural environment and human-made changes to environment | - | - | - |

| Body Functions | |||

| Mental functions | 331 | 22·9 | 77·9 |

| Functions of the cardiovascular, hematological, immunological, and respiratory systems | 8 | 0·6 | 1·9 |

| Sensory functions and pain | 20 | 1·4 | 4·7 |

| Genitourinary and reproductive functions | 16 | 1·1 | 3·8 |

| Functions of the digestive, metabolic, and endocrine systems | 41 | 2·8 | 9·6 |

| Neuromusculoskeletal and movement-related functions | 5 | 0·3 | 1·2 |

| Functions of the skin and related structures | 3 | 0·2 | 0·7 |

| Voice and speech functions | 1 | 0·1 | 0·2 |

| Body Structures | |||

| Structures related to movement | 7 | 0·5 | 53·8 |

| Skin and related structures | 6 | 0·4 | 23·1 |

| Structures of the nervous system | 2 | 0·1 | 15·4 |

| Structures related to the digestive, metabolic and endocrine systems | 1 | 0·1 | 7·7 |

| The eye, ear, and related structures | - | - | 0·0 |

| Structures involved in voice and speech | - | - | 0·0 |

| Structures of cardiovascular, immunological, and respiratory systems | - | - | 0·0 |

| Structures related to the genitourinary and reproductive systems | - | - | 0·0 |

Most linked categories for each ICF component

The top five linked categories within the “Activities and Participation” component were as follows:

“d2408 Other specified handling stress and other psychological demands” (95 links), pertaining to the “General tasks and demands” chapter

“d329 Communicating—receiving, other specified and unspecified” (40 links), pertaining to the “Communication” chapter

“d770 Intimate relationships” (37 links), pertaining to the “Interpersonal interactions and relationships” chapter

“d5702 Maintaining one’s health” (26 links), pertaining to the “Self-care” chapter

“d3508 Conversation, other specified” (23 links), pertaining to the “Communication” chapter

Supplementary Fig. 16A describes the distribution of links in the nine chapters pertinent to the “Activities and Participation” component at the PROM level.

The top five linked categories within the “Environmental Factors” component were as follows:

“e355 Health professionals” (78 links), pertaining to the “Supports and relationship” chapter

“e580 Health services, systems, and policies” (67 links) and

“e5800 Health services” (60 links), both in the “Services, systems, and policies” chapter

“e399 Support and relationships, unspecified” (42 links) and

“e315 Extended family” (32 links), both in the “Supports and relationship” chapter

Supplementary Fig. 17A describes the distribution of links in the five chapters pertaining to the “Environmental Factors” component at the PROM level.

The top five linked categories within the “Body Functions” component were as follows:

“b152 Emotional functions” (141 links)

“b160 Thought functions” (28 links)

“b1801 Body image” (25 links)

“b1521 Regulation of emotion” (20 links)

“b130 Energy and drive functions” (17 links)

All these categories belong to “Mental functions.”

Supplementary Fig. 18A describes the distribution of the links in the eight chapters pertinent to the “Body Functions” component at the PROM level.

The links to the “Body Structures” component were numerically much fewer than the previous ones, and the links to its pertinent categories were also limited. The most linked category was “s750 Structure of lower extremity,” which was linked three times.

Supplementary Fig. 19A describes the distribution of the links in the eight chapters pertinent to the “Body Structures” component at the PROM level.

Discussion

This study comprehensively linked the 14 PROMs that reliably assess the unmet needs of adult CSs suffering from non-cutaneous cancers to the ICF components. As a result, it provides an understanding of the contents assessed by these PROMs, thus facilitating the selection of suitable PROMs based on the domains to be addressed in the clinical or research setting.

Overall representation of ICF components

The results clearly demonstrate that each of the 14 PROMs included the ICF components in a unique way. Notably, “Activity and Participation” (37·2%) and “Environmental Factors” (31·8%) were the most represented components in the PROMs analyzed, with the four most represented categories (“Other specified handling stress and other psychological demands,” “Major life areas,” “Health professionals,” and “Health services”) pertaining to them. In the context of cancer survivorship, assessing “Activities and Participation” plays a crucial role in ensuring comprehensive and targeted care for these individuals, thereby significantly improving their quality of life. Understanding the level of “Activities and Participation” not only provides an overview of the physical and psychosocial impact of cancer and its treatments but also valuable insights into the rehabilitation needs and ways to enhance the overall health and well-being of CSs [18]. Regular assessment of “Activities and Participation” allows healthcare professionals to identify the challenges and barriers CSs may encounter in their healing journey and thus to intervene promptly to address them. Additionally, better management of “Activities and Participation” can help reduce the risk of depression, anxiety, and other emotional disorders, enabling CSs to lead a fuller and more satisfying life despite the challenges associated with their illness and treatment [19].

It is noteworthy that in the “Activities and Participation” component, we found 51 links with the category “Economic life.” The long-term effects of a cancer diagnosis include difficulties in returning to work and financial concerns [20, 21]. The importance of investigating the economic impact on working-age cancer survivors was also highlighted by focus groups in a study conducted by Paltrinieri et al., which reports that half of cancer survivors experience financial distress, known as “financial toxicity” [22].

This study also highlights the importance of the environment in meeting the needs of survivors. In a study focused on identifying the health problems among adult cancer survivors, the development and validation of the Cancer Survivor Core Set revealed a predominance of categories related to “Environmental Factors” (six out of 19 categories) [23]. This underscores the significance of investigating an individual’s environment (in its broadest sense) to eliminate barriers and implement facilitators. Environmental factors include cultural, economic, institutional, physical, and social dimensions, as proposed by the person-environment-occupation model [24]. The 14 PROMs analyzed primarily focus on investigating health services, with the most frequently linked categories being “Health professionals” and “Health services, systems, and policies.” To a lesser extent, relationships of support were also explored, both within and outside the family. Of note, only a few items address the physical environment, although the physical dimension is pivotal among environmental factors. This may reflect a tendency to prioritize healthcare and institutional support for CSs over the examination of physical barriers. This tendency aligns with the concept that the social environment significantly impacts an individual’s experiences and functioning, overshadowing the scrutiny of physical barriers [25].

The “Body functions” component was the third most significant component (29·8%), with a particular emphasis on mental functions. This underscores the critical importance of addressing both global mental functions, such as consciousness, energy, and motivation, and specific mental functions, such as memory, language, and cognitive functions, when caring for cancer survivors. In their survey, Fardel et al. highlighted that anxiety, depression, and cognitive impairment seem to be present in CSs. Younger individuals at the time of diagnosis, females, and those with lower levels of education are more likely to report anxiety, depression, and compromised cognitive functions [26].

“Body structures” was scarcely represented in the 14 PROMs analyzed (1·0% of all the links), indicating little relevance of this ICF component in the investigation of the needs and challenges that CSs face. It is possible that only 1% of these questions pertain to “Body structures” because such aspects are already extensively examined during the clinical or acute phase of the disease, so it may not have been deemed necessary to give them further prominence in these tools. Additionally, body structures may not be considered an important issue compared to other aspects, such as physical function or quality of life, which may be deemed a priority when assessing the overall well-being of CSs. The low percentage could also be attributed to its significant pathology-dependent variability, making it challenging to generalize or standardize the evaluation of body structures through CS PROMs. Moreover, there may be a lack of consensus on which specific aspects of body structures should be assessed in CS PROMs, thus contributing to the low percentage of questions in this area. Since the “Body Structures” component focuses on anatomical body parts, it should not be surprising that this aspect is less frequently captured within PROMs. While patients may be asked about physical symptoms, they are not necessarily asked about specific anatomical parts.

Variability among PROMs

Notably, the PROMs exhibited substantial variability. While the NEQ and the SUNS strongly focus on the “Activities and Participation” component, others, like the CaSUN and the PNI, emphasize environmental factors, and the CaNDI and the eHNA pay major attention to body functions. Only six PROMs encompassed meaningful concepts related to the “Body Structure” component, with the highest percentage (8·1%) attributed to the eHNA.

Key ICF categories

The linking process implemented in this study identified key ICF categories that were consistently represented across PROMs. Notably, “Handling stress and other psychological demands” accounted for 95 links, highlighting a significant focus on the psychological impact of cancer survivorship [27]. Moreover, the categories “Health professionals,” “Health services, systems, and policies,” “Health services,” and “Support and relationships” were linked 78, 67, 60, and 42 times, respectively. This may reflect the need to adopt a holistic approach that integrates both health care and interpersonal support strategies in the care of CSs [28]. Finally, “Emotional functions” was linked 141 times, highlighting the pivotal importance of addressing emotional distress in this population, as also highlighted by Martínez Arroyo [29].

The results of the linking process reflect the current understanding of the scope of unmet needs within this population. Unmet needs among cancer survivors span a wide range of physical, emotional, practical, and informational challenges that profoundly affect their quality of life, as highlighted by Expert Consensus Statements on Cancer Survivorship [30].

The results obtained from the linking process could help healthcare organizations to create diagnostic-therapeutic care pathways based on PROMs, strategically and judiciously allocating resources according to the needs of CSS [31].

Limitations and future directions

This study has some limitations. First of all, although the linking process was carried out following precise guidelines, the choice of meaningful concepts to be linked and their match with the ICF contents are prone to subjectivity; indeed, a certain degree of disagreement between the reviewers was detected [14]. This disagreement was resolved through discussion with a third expert researcher. However, to improve interrater reliability and reduce discrepancies in the coding process, future research should implement more precise coding guidelines. Additionally, a thorough examination of the 131 concepts that lacked consensus provides valuable insights for refining the coding framework and conducting a more robust analysis.

Conclusion

This systematic evaluation of PROMs for CSs conclusively contributes to the ongoing efforts to better understand and address the unmet needs of this population. The comprehensive linking to the ICF framework facilitates a nuanced comparison of these tools, guiding healthcare professionals in selecting appropriate PROMs tailored to specific survivorship contexts. As cancer care continues to evolve, addressing the diverse needs of CSs remains of paramount importance to improving their overall well-being.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank Jacqueline M. Costa for the English language editing.

Author contribution

MS, AC, and SC wrote the main text of the manuscript, with AC preparing the figures and MS preparing the tables. Data analysis was performed by AC and MS, supervised by SC and IB. SF and SL contributed to the discussion. All authors reviewed the manuscript and participated in the conceptualization.

Funding

This study was partially supported by the Italian Ministry of Heath_Ricerca Corrente Annual Program 2025. The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files, and an online repository is available and cited in the References (10.5281/zenodo.12607869).

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Razzano G (2024) Equità e integrazione: due principi chiave per un nuovo piano sanitario nazionale. Oltre la “missione salute” del PNRR." RIVISTA AIC 4:49–66

- 2.Sanft T, Denlinger CS, Armenian S, Baker KS, Broderick G, Demark-Wahnefried W et al (2019) NCCN guidelines insights: survivorship, Version 2.2019. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 17:784–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Denlinger CS, Ligibel JA, Are M, Baker KS, Broderick G, Demark-Wahnefried W et al (2016) NCCN guidelines insights: survivorship, Version 1.2016. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 14:715–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Firkins J, Hansen L, Driessnack M, Dieckmann N (2020) Quality of life in “chronic” cancer survivors: a meta-analysis. J Cancer Surviv [Internet] 14:504–17. 10.1007/s11764-020-00869-9. [cited 2024 Apr 23] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harrison JD, Young JM, Price MA, Butow PN, Solomon MJ (2009) What are the unmet supportive care needs of people with cancer? A systematic review. Support Care Cancer 17:1117–1128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kotronoulas G, Kearney N, Maguire R, Harrow A, Di Domenico D, Croy S et al (2014) What is the value of the routine use of patient-reported outcome measures toward improvement of patient outcomes, processes of care, and health service outcomes in cancer care? A systematic review of controlled trials. J Clin Oncol 32:1480–1501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Contri A, Paltrinieri S, Torreggiani M, Chiara Bassi M, Mazzini E, Guberti M et al (2023) Patient-reported outcome measure to implement routine assessment of cancer survivors’ unmet needs: an overview of reviews and COSMIN analysis. Cancer Treat Rev 120:102622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Di Maio M, Basch E, Denis F, Fallowfield LJ, Ganz PA, Howell D et al (2022) The role of patient-reported outcome measures in the continuum of cancer clinical care: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline. Ann Oncol 33:878–892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization (2001) International classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF). https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/international-classification-of-functioning-disability-and-health . Accessed 30 Apr 2024

- 10.Leonardi M, Lee H, Kostanjsek N, Fornari A, Raggi A, Martinuzzi A et al (2022) 20 years of ICF—International classification of functioning, disability and health: uses and applications around the world. Int J Environ Res Public Health. https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/19/18/11321. Accessed 23 Apr 2024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.ICF e-Learning Tool_English_20220501. https://www.icf-elearning.com/wp-content/uploads/articulate_uploads/ICF%20e-Learning%20Tool_English_20220501%20-%20Storyline%20output/story_html5.html. Accessed 23 Apr 2024

- 12.World Health Organization. How to use the ICF - A practical manual for using the international classification of functioning, disability and health https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/how-to-use-the-icf---a-practical-manual-for-using-the-international-classification-of-functioning-disability-and-health . Accessed 17 May 2024

- 13.Cieza A, Brockow T, Ewert T, Amman E, Kollerits B, Chatterji S et al (2002) Linking health-status measurements to the international classification of functioning, disability and health. J Rehabil Med 34:205–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cieza A, Geyh S, Chatterji S, Kostanjsek N, Ustün B, Stucki G (2005) ICF linking rules: an update based on lessons learned. J Rehabil Med 37:212–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cieza A, Fayed N, Bickenbach J, Prodinger B (2019) Refinements of the ICF linking rules to strengthen their potential for establishing comparability of health information. Disabil Rehabil 41:574–583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Landis JR, Koch GG (1977) The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33:159–74. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2529310 . Accessed 23 Apr 2024 [PubMed]

- 17.Costi S, Contri A, Schiavi M (2024) Repository: identifying unmet needs in cancer survivorship by linking patient-reported outcome measures to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health [Internet]. https://zenodo.org/: Zenodo. Available from: 10.5281/zenodo.12607869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Schwartz AL, Bea JW, Winters-Stone K (2020) Long-term and late effects of cancer treatments on prescribing physical activity. In: Schmitz KH (ed.) Exercise oncology: prescribing physical activity before and after a cancer diagnosis [Internet]. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp 267–82. Available from: 10.1007/978-3-030-42011-6_13

- 19.Chen J, Gan L, Tuersun Y, Xiong M, Sun J, Zhang C et al (2023) Social participation: a strategy to manage depression in disabled populations. J Aging Soc Policy 1–17. 10.1080/08959420.2023.2255492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Stanton AL (2006) Psychosocial concerns and interventions for cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 24:5132–5137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ell K, Xie B, Wells A, Nedjat-Haiem F, Lee P-J, Vourlekis B (2008) Economic stress among low-income women with cancer: effects on quality of life. Cancer 112:616–625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paltrinieri S, Costi S, Pellegrini M, Díaz Crescitelli ME, Vicentini M, Mancuso P et al (2022) Adaptation of the core set for vocational rehabilitation for cancer survivors: a qualitative consensus-based study. J Occup Rehabil 32:718–30. 10.1007/s10926-022-10033-y. [cited 2024 Apr 23] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geerse OP, Wynia K, Kruijer M, Schotsman MJ, Hiltermann TJN, Berendsen AJ (2017) Health-related problems in adult cancer survivors: development and validation of the Cancer Survivor Core Set. Support Care Cancer 25:567–574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Law M, Cooper B, Strong S, Stewart D, Rigby P, Letts L (1996) The person-environment-occupation model: a transactive approach to occupational performance. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/000841749606300103 . Accessed 23 Apr 2024

- 25.Carradori T, Bravi F, Butera DS, Iannazzo E, Valpiani G, Wienand U (2017) La continuità delle cure in oncologia. Un’analisi quantitativa dell’esperienza dei pazienti in due realtà emiliano-romagnole. Recenti Progressi in Medicina 108:288–93. https://www.recentiprogressi.it/archivio/2715/articoli/27716/ . Accessed 23 Apr 2024 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Fardell JE, Irwin CM, Vardy JL, Bell ML (2023) Anxiety, depression, and concentration in cancer survivors: national health and nutrition examination survey results. Support Care Cancer 31:272. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10105664/ . Accessed 23 Apr 2024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Tanner S, Engstrom T, Lee WR, Forbes C, Walker R, Bradford N et al (2023) Mental health patient-reported outcomes among adolescents and young adult cancer survivors: a systematic review. Cancer Med 12:18381–18393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaur B (2020) Interpersonal communications in nursing practice - key to quality health care. Arch Nurs Pract Care 6:019–22. https://www.medsciencegroup.us/articles/ANPC-6-144.php . Accessed 17 May 2024

- 29.Martínez Arroyo O, Andreu Vaíllo Y, Martínez López P, Galdón Garrido MJ (2019) Emotional distress and unmet supportive care needs in survivors of breast cancer beyond the end of primary treatment. Support Care Cancer 27:1049–1057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vaz-Luis I, Masiero M, Cavaletti G, Cervantes A, Chlebowski RT, Curigliano G, Felip E, Ferreira AR, Ganz PA, Hegarty J, Jeon J, Johansen C, Joly F, Jordan K, Koczwara B, Lagergren P, Lambertini M, Lenihan D, Linardou H, Loprinzi C, …, Pravettoni G (2022) ESMO Expert Consensus Statements on Cancer Survivorship: promoting high-quality survivorship care and research in Europe. Ann Oncol: Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol 33(11), 1119–1133. 10.1016/j.annonc.2022.07.1941 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Damman OC, Jani A, Jong BA de, Becker A, Metz MJ, DE Bruijne MC et al (2020) The use of PROMs and shared decision‐making in medical encounters with patients: an opportunity to deliver value‐based health care to patients. J Eval Clin Pract 26:524. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7155090/ . Accesssed 23 Apr 2024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files, and an online repository is available and cited in the References (10.5281/zenodo.12607869).