Abstract

Skipped dienes are among the most prevalent motifs in a vast array of natural products, medicinal compounds, and fatty acids. Herein, we disclose a straightforward one-step reductive protocol under Co/PC for the synthesis of diverse 1,4-dienes with excellent regio- and stereoselectivity. The protocol employs allenyl or allyl carbonate as π-allyl source, allowing for the direct synthesis of skipped diene with a broad range of alkynes including terminal alkynes, propargylic alcohols, and internal alkynes. The method also demonstrated the biomimetic homologation of natural terpenols into synthetic counterparts via iterative allylation of three-carbon allyl units, employing propargylic alcohol as a readily available alkyne source. Experimental studies, control experiments, and DFT calculations suggest the dual catalytic process generates 1,3-diene from allenyl carbonate, followed by proton and electron transfer leading to Co(II)-π-allyl species prior to the alkyne coupling. The catalytic cycle transitions through Co(II), Co(I), and Co(III).

Subject terms: Photocatalysis, Homogeneous catalysis, Synthetic chemistry methodology

Skipped dienes are among the most prevalent motifs in vast array of natural products, medicinal compounds, and fatty acids. Here, the authors disclose a straightforward one-step reductive protocol under Co/PC for the synthesis of diverse 1,4-dienes with excellent regio- and stereoselectivity.

Introduction

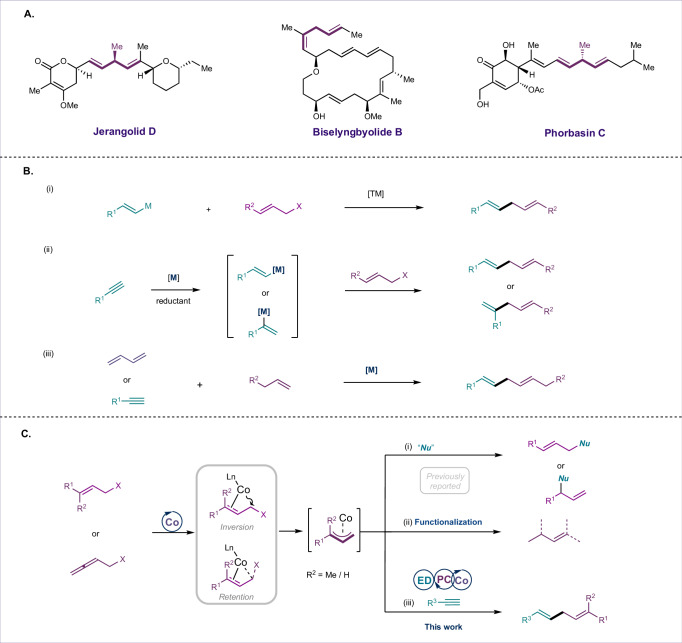

Skipped dienes are present in a wide-array of primary metabolites, polyketides, fatty acids, and terrestrial/marine natural products1–4. The distinctive features of most polyunsaturated fatty acids are determined by a stereo-chemically specified skipped diene motif. In contrast to 1,3-dienes, which are inextricably bonded, the sp3-hybridized carbon atoms in skipped dienes (1,4-dienes) sit at right angles to one another. Methyl substituents at the sp3-carbon placed between the two olefins have an enormous impact on the bioactivity of secondary metabolites such as Phorbasin C and Jerangolid D (Fig. 1A)5–8. However, the synthesis of such skipped dienes with complete control over stereo- and regioselectivity remains a significant challenge in organic synthesis. Numerous methods have been developed for cross-allyl/vinyl coupling reactions, including the use of vinyl organometallic reagents (Fig. 1B(i))9–16, allyl metalation of alkynes (Fig. 1B(ii)17–21, and Alder-ene reactions (Fig. 1B(iii))22,23. However, these approaches often require stoichiometric amounts of organometallic reagents or metal reductants, which can limit their practicality in targeted synthesis. In this context, metal-catalyzed hydroallylation reactions have proven transformative for the atom-economical synthesis of 1,4-dienes24–30. Since Trost’s seminal work24, many studies have demonstrated the effective hydroallylation of alkynes facilitated by stoichiometric amounts of reductants or metal hydrides in the presence of transition metals such as nickel26, copper27,28, and cobalt30, leading to regioselective synthesis of skipped dienes. Despite these advancements, these methods have drawbacks; they largely rely on in situ-generated vinyl metal species from alkynes through hydrometallation, which may result in regioselectivity issues prior to cross-coupling with allylic electrophiles (Fig. 1B(ii)). Conversely, the hydroalkenylation of 1,3-dienes also yields skipped dienes and has been accomplished using cobalt31–34, nickel35, and iron36 catalysts (Fig. 1B(iii)). A significant advantage of these methods over traditional cross-coupling strategies is that the substrates are readily available and do not require prefunctionalization. Additionally, 1,2-carboallylation of alkynes37–44 and carboalkenylation of 1,3-dienes45 have been explored, with or without organometallic coupling partners (Fig. 1B(ii) & (iii)). A missing link in these ongoing studies is the utilization of readily available allylic surrogates with low-valent metals via oxidative addition in the absence of stoichiometric reductant, followed by coupling with π-partners such as alkynes to produce skipped dienes with high regioselectivity. This method may have direct implications for the homologation of allylic fragments, akin to biosynthetic pathways46–48.

Fig. 1. Importance of skipped dienes and its synthetic overview.

A Bioactive molecules containing Skipped diene. B Reported methods for the synthesis of skipped diene. C Activation of allylic substrates with Co(I).

With the rise of greener and more sustainable methods in recent years, benign metallophoto-redox catalysis using 3 d metals has shown effectiveness in facilitating valuable C–C and C–N bond-forming reactions49–56. Among the 3 d metals, cobalt has been extensively employed for cross-electrophile coupling with activated allylic substrates and alkyl halides (Fig. 1B(i))57,58, as well as for allylic substitution with hard or soft nucleophiles (Fig. 1C(i))54–59. In this regard, activation of allylic substrates via oxidative addition was achieved with the in situ generated low-valent cobalt under dual cobalt/photoredox catalysis although stereochemistry of oxidative addition is yet to be comprehend59. For example, Sigman60 and Casitas61 independently proposed that the oxidative addition proceeds through retention pathway (SN1 type polarization) whereas Tunge62,63 and co-workers proposed inversion pathway although the ligand and steric environment of the central cobalt are not the same (Fig. 1C(i) and (ii)). A recent innovative approach involves a proton-coupled electron transfer strategy to generate (π-allyl)metal species from dienes—either in situ from vinyl carbonates or from commercially available allenyl derivatives—followed by interception with other coupling partners to yield cross-coupled products (Fig. 1C(i) & (ii))64–66. However, the direct formation of (π-allyl)cobalt species through oxidative addition of allylic surrogates, followed by coupling with alkynes under cobalt/photoredox catalysis without the use of external reductants, remains relatively unexplored (Fig. 1C(iii)).

Based on our previous experimental results66, we postulate that allenyl carbonate could generate 1,3-diene in situ using cobalt with a photocatalyst and an electron donor under visible light. The in situ-generated diene could then undergo protonation via a proton-coupled electron transfer process to yield the Co(II)-π-allyl intermediate. Alternatively, the Co(II)-π-allyl intermediate may form via oxidative addition of allylic substrates to low-valent cobalt(I), followed by one-electron reduction leading to the same intermediate. Subsequent alkyne coordination, migratory insertion between Co−C, and protodemetallation would afford the skipped diene (Fig. 1C(iii)). Herein, we report a sustainable one-pot protocol for the reductant-free, cobalt-catalyzed reductive coupling of alkynes with allylic surrogates (allyl or allenyl carbonates) under photoirradiation, enabling access to diverse skipped dienes in good-to-excellent yields. This efficient strategy also highlights the role of in situ-generated diisopropylammonium bicarbonate67 (produced in situ from Hünig base and water under photocatalytic conditions) as a unique proton donor in the protodemetallation steps.

Results

We began our investigation using phenyl acetylene 1a and allenyl carbonate 2a as the coupling partners, employing 10 mol% of CoCl2, 10 mol% of 4,4′-dtbbpy, 2 mol% of 4CzIPN, 4 equiv. of DIPEA in 0.1 M MeCN:H2O (9:1) under photo-irradiation, as shown in Table 1. The resultant product 3aa was obtained as a single regioisomer in 73% NMR yield and 64% as isolated yield (entry 1). Analysis of the crude mixture indicated no alteration in stereochemistry or regioselectivity, as we only obtain E,E-linear selective product 3aa over the branched selective product 3aa′. A systematic screening was performed to identify the best cobalt precursor, ligand, solvent, and base (see the SI for more details). Replacing 4CzIPN with [Ir-PC] as photocatalyst provided 3aa, albeit in moderate yield (entry 2). Removing substituents on the bpy ligand or replacing 4,4’-dtbbpy ligand with phosphine ligand did not yield the desired outcome (entries 3-4).

Table 1.

Reaction Optimizationa

| Entry | Change in condition | Yield of 3aab,c |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | none | 73 (64) |

| 2 | [Ir-PC] instead of 4CzIPN | 49 |

| 3 | bpy instead of dtbbpy | 41 |

| 4 | Xantphos instead of dtbbpy | n.r. |

| 5 | DIPA instead of DIPEA | 27 |

| 6 | 2 equiv. of 1a and 1 equiv. of 2a | 89 (81) |

| 7 | without 4CzIPN | n.r. |

| 8 | without [Co] | n.r. |

| 9 | without H2O | n.r. |

| 10 | without DIPEA | n.r. |

| 11 | in absence of light | n.r |

| 12 | under air | 89 (80) |

a All the reactions were carried out under argon atmosphere unless otherwise stated using phenylacetylene 1a (0.1 mmol), allenyl carbonate 2a (0.2 mmol), diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA) (0.4 mmol), cobalt catalyst (0.01 mmol), 4,4′-dtbbpy (0.01 mmol), photocatalyst (0.002 mmol), in CH3CN:H2O (9:1, 0.1 M) under 45 W blue LED irradiation (440 nm) for 24 h. b NMR yield (%) calculated from the crude mixture using anisole as internal standard. c number in parenthesis is isolated yield (%). The temperature rises due to 2 LED lights to the max. of 35 °C. DIPA = diisopropyl amine, n.r. = no reaction.

Other electron donors, such as diisopropyl amine, subjected to reaction conditions, afforded the desired product with lower yield (entry 5). The best yield of 3aa was obtained when stoichiometry of alkyne (1a) and allenyl carbonate (2a) was reversed to 2:1 resulting in the skipped diene in 81% isolated yield (entry 6). Control experiments revealed that all components—photocatayst (PC), [Co], H2O, DIPEA, and light- are necessary; without anyone of them, the reaction did not proceed (entry 7-11). No change in reactivity was observed when the reaction was performed under air, yielding 3aa in 80% isolated yield (entry 12), suggesting that the reaction is not sensitive to air and moisture. This may be due to the presence of excess of Hünig base, which rapidly undergoes proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET). This process may first reduce molecular oxygen to superoxide radical anions (O2•−), which are subsequently converted into hydrogen peroxide, effectively removing oxygen from the reaction medium60,68. As a result, the active species can be continuously regenerated in the catalytic cycle, even in the presence of atmospheric air within a closed vial.

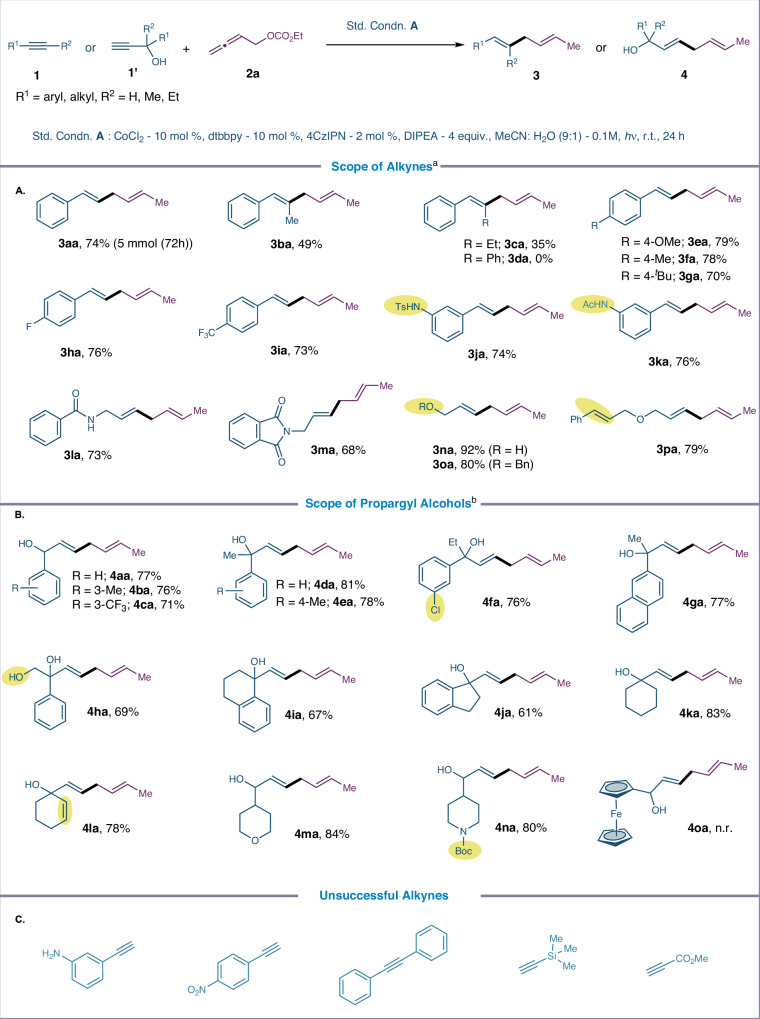

With the optimized reaction conditions in hand, we explored the generality of the discovered protocol. Figure 2 illustrates the range of steric and electronic substituents on alkyl and aryl groups directly linked to the alkyne in this transformation. We first conducted the reaction on a 5 mmol scale to assess the practical utility of the developed protocol for large-scale synthesis. The expected product 3aa was obtained in 74% yield, indicating that the reaction is scalable. Next, we evaluated the reactivity differences between terminal and internal alkynes (1b-1d), and the results suggested that terminal alkyne exhibit superior reactivity, possibly due to steric influences during the migratory insertion step. Alkynes with electron-deficient and electron-rich substituents (MeO, Me, tBu, F and CF3,) at various positions on the aryl moiety were susceptible and provided the desired skipped diene motif (3ea-3ia) in yields ranging from 70 to 79%. Electron-deficient alkynes featuring sulfonamide (3ja), acetamide (3ka), benzamide (3la), and phthalimide (3ma) performed remarkably well. Sensitive but valuable functional groups such as hydroxy, ether, and a competing allyl ether moiety showed good tolerance, allowing the production of 1,4-diene motifs without any side products (3na-3pa). The alkyne scope can be extended to diverse propargylic alcohols. Monosubstituted propargyl alcohols derived from electronically diverse benzaldehydes were reductively coupled with allenyl carbonate, yielding the skipped dienes (4aa-4ca) with excellent stereoselectivity control. Furthermore, alcohols generated from ketones also performed well and provided the tertiary alcohols in the diene products (4da-4ga). Propargyl alcohol derived from β-hydroxy ketone, tetralone, indanone, cyclohexanone, cyclohexenone were amenable and produced the desired dienes/trienes without compromising the isolated yield of the product (4ha-4la). Interestingly, substrates containing saturated (hetero)cyclic fragments, common in pharmaceuticals, furnished the products in good yields (4ma-4na). However, propargyl alcohol derived from ferrocene carboxaldehyde 1o was incompatible, most likely due to an interruption in the electron transfer process. Additionally, neither the free amine nor the nitro groups attached to phenyl acetylene, TMS-alkyne, or methyl propiolate underwent reductive coupling under standard conditions.

Fig. 2. Substrate scope of alkynes and propargyl alcohols.

A Scope of alkynes. B Scope of propargyl alcohols. C Unsuccessful alkynes. a1:2 stoichiometric ratio of allenyl carbonate 2a and alkyne are utilized. bAllenyl carbonate 2a and propargyl alcohol 1' are utilized in 1:4 stochiometric ratio.

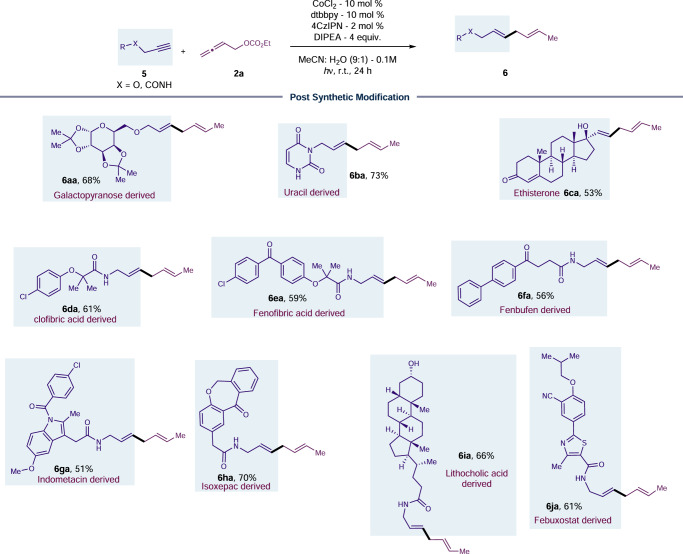

Next, we investigated alkyne compatibility in late-stage functionalizations with diverse substrates containing natural products, carbohydrates, nucleotides, and/or pharmaceutical compounds, due to the excellent functional group tolerance demonstrated in photo-induced reductive coupling approach (Fig. 3). Galactopyranose, Uracil and Ethisterone retain their diketal functionality or α,β-unsaturated carbonyl moiety under reductive coupling, allowing access to the 1,4-diene motif (6aa-6ca) during the late-stage diversification. Biologically active metabolites such as Clofibric acid (6da), Fenofibric acid (6ea) and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug such as Fenbufen (6fa), and Indomethacin (6ga) are amenable for late-stage installation of 1,4-diene motif while retaining functional group such as chloro, ether, ketone, and heterocyclic core. Even an alkyne derived from Isoxepac, Lithocholic acid and Febuxostat successfully produced the desired outcome, indicating the compatibility of susceptible functional groups (6ha-6ja).

Fig. 3. Post synthetic diversification of natural products and bioactive molecules.

The reaction was performed on a 0.1 mmol scale under the condition in Table 1, entry 12.

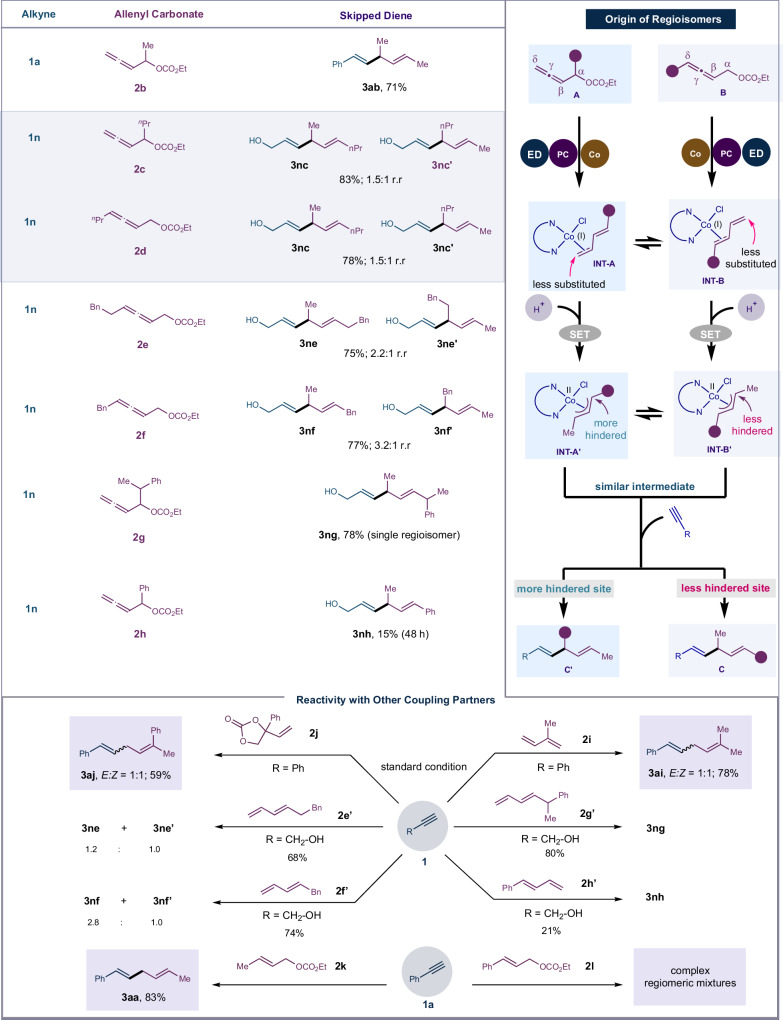

Most notably, this method is efficient in coupling sterically encumbered allenyl carbonate partners, and pattern of the regioselectivity is similar that observed in Figs. 2 and 3. Migratory insertion occurs at the less hindered site of the Co−C in π-allyl cobalt(II) intermediate during C–C bond formation step, as depicted in Fig. 4. For example, α-methyl allenyl carbonate 2b when subjected to the reaction conditions afforded the skipped diene 3ab with methyl substituents at the sp3-carbon placed between the two olefins. Increasing the carbon chain by introducing n-propyl group in place of methyl group at the α-carbon to the oxygen provided the skipped dienes in 85% yield, with a mixture of regioisomers (3nc and 3nc′) in a ratio of 1.5:1. Allenyl carbonate 2d, having n-propyl substitution at the δ-carbon, produced the same products (3nc and 3nc′) in 83% isolated yield with a regiomeric ratio of 1.5:1, indicating that both allenyl carbonates (2c and 2d) proceed through the same π-allyl cobalt(II) intermediate.

Fig. 4. Substrate scope of allenyl carbonate, origin of regioselectivity and reactivity of other coupling partner.

The reaction was performed in 0.3 mmol scale under standard condition A.

Based on these findings, we postulated that allenyl carbonates with the same functionality at the α- or δ-carbon would produce the identical 1,3-diene intermediate INT-A or INT-B, or the resultant π-allyl cobalt(II) intermediates INT-A′ or INT-B′ upon protonation followed by SET, as shown in Fig. 4. Following alkyne coordination, migratory insertion occurs at the less hindered site of the Co−C bond in the π-allyl cobalt(II) intermediate. This results in an intermediate that undergoes protodemetallation, ultimately yielding skipped diene C or C’ as the regioisomer. Experimental results showed that the former is more favored over the latter and is obtained as major isomer. To further validate our experimental findings, allenyl carbonates 2e and 2f were employed. Analysis of the products revealed that among the two isomers, 3ne and 3nf were obtained as major isomer, respectively. The reaction is largely steric dependent, and the regioisomeric ratio can be improved by introducing sterically bulky group at the α-carbon to the oxygen.

In line with our hypothesis, sterically bulky allenyl carbonate 2g afforded the skipped diene 3ng as a single regioisomer. However, phenyl substitution at the α-carbon of the allenyl carbonate (2h) drastically slowdown the reaction, yielding only 15% of the resultant skipped diene (3nh). This suggests that the phenyl group, which is directly attached to the π-allyl cobalt(II) intermediate, draws more electron density and introduces steric hindrance, possibly slowdown the migratory insertion step with the alkyne.

We further explored the reactivity of additional coupling partners that resemble either allenyl carbonate or the in situ produced 1,3-diene or Co-π-allyl intermediate to assess the importance of the established reductive coupling approach. To begin with, Isoprene (2i) was used directly as a diene partner with 1a, yielding the skipped diene 3ai in 78% yield, with E:Z ratio of 1:1. Cyclic vinyl carbonate (2j), known to liberate 1,3-diene in situ65, showed reactivity similar to that of allenyl carbonate; however, the skipped diene 3aj was obtained in 59% yield with poor stereoselectivity (E/Z = 1:1). These results suggest that the 1,3-diene could be suitable for reductive coupling; however, substituent at the C-2 position of the 1,3-diene hinder the stereochemical outcome of the reaction. To further validate our findings, we independently synthesized the 1,3-dienes 2e’-2h’. When subjected to standard conditions, these dienes produced results comparable to those obtained with the corresponding allenyl carbonates. These experiments reinforce the formation of the 1,3-diene in situ and its subsequent coupling with alkyne, leading to the expected skipped dienes. To confirm the in situ formation of π-allyl cobalt(II) species, we tested both cinnamyl carbonate (2l) and crotyl carbonate (2k) for reductive coupling with alkyne under standard conditions (Fig. 4). The cinnamyl carbonate resulted in a mixture of unidentified products, while the crotyl carbonate yielded the expected product 3aa in 83% yield, similar to the results obtained with the allenyl carbonate model substrate.

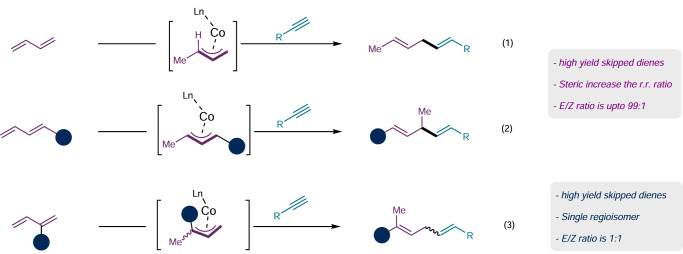

The rationale for the observed selectivity is based on the reactivity of the 1,3-diene and the formation of the corresponding π-allyl cobalt complex prior to its coupling with the alkyne, as illustrated in Fig. 5. As shown in both cases 1 and 2 of Fig. 5, either unsubstituted 1,3-butadiene or C-1 substituted 1,3-butadiene can be obtained from allenyl carbonate, leading to consistently high stereoselectivity for the skipped diene produced upon coupling with alkyne. In contrast, the C-2 substituted 1,3-diene (case 3) cannot be generated using allenyl carbonate, which explains the absence of stereoisomers in our reactions with this class of substrate.

Fig. 5. The plausible formation of Co-π-allyl intermediate from 1,3-dienes and its products formation with alkyne.

(1) 1,3-butadiene generated from allenyl carbonate 2a and its reactivity with alkyne. (2) and (3) C-1 or C-2 substituted 1,3-butadiene derivatives derived from the corresponding allenyl carbonates and its reactivity and selectivity with alkyne.

Building on the results obtained with crotyl carbonate, we investigated other allylic carbonates under the standard condition A used for the reductive coupling of allenyl carbonates and alkynes, as detailed in Fig. 6. Although skipped diene formation was observed with sterically less hindered allylic substrates, the yield and stereochemical outcome were compromised. The reaction condition are not generally applicable to other allylic substrates, and many allylic carbonates that failed to yield successful outcome are also shown in Fig. 6. These results suggest that extensive and systematic screening is necessary for the direct coupling of allylic carbonates with alkyne, as opposed to the standard conditions used with allenyl carbonates in the cobalt/photoredox catalytic system.

Fig. 6. Reductive coupling of allyl carbonate and alkyne under Co/PC catalytic system.

A Scope of allyl carbonates. B Unreactive allylic substrates. The reaction was performed in 0.3 mmol scale under standard condition A.

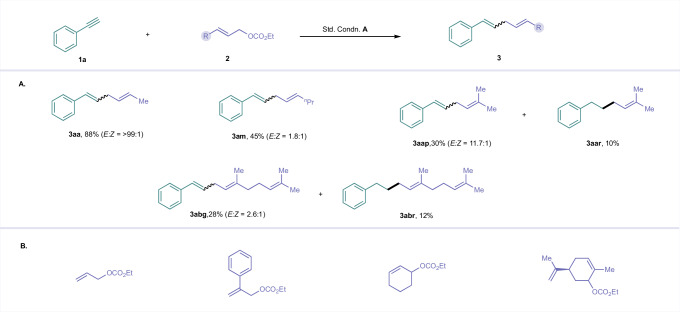

Drawing inspiration from the controlled stereoselectivity observed with crotyl and prenyl carbonates (see Fig. 4–6), we further investigated the reaction conditions for the reductive coupling of crotyl and prenyl carbonates with alkyne. A preliminary screening of the reaction conditions allowed us to identify the optimized parameters for the reductive coupling (see SI for details). The optimized conditions involve a catalytic system consisting of 10 mol% Co(NO3)2·6H2O, 10 mol% 4,4′-dtbbpy, 2 mol% 4CzIPN, 20 mol% Hantzsch ester, and 4 equivalents of DIPEA in 0.1 M MeCN, with the resulting mixture subjected to photo-irradiation for 24 h. This led to the formation of the skipped diene 8 in excellent yields with a very high E/Z ratio (see Fig. 7, top). These results motivated us to explore additional terpenol derivatives under cobalt/PC reductive conditions for allyl homologation from natural terpenols. We successfully evaluated a range of terpenols, including prenol, geraniol, nerol, phytol, and solanesol derivatives, all of which yielded corresponding skipped dienes in good yield, with exclusive formation of a single stereoisomer. Furthermore, the generality of the reaction with various alkyne further confirmed that the allyl-alkyne reductive coupling can be achieved in addition to allenyl carbonate (see SI for comparative results). Such structurally diverse collection of isoprenoid compound is constructed by homologation of allyl/prenyl fragment through biosynthetic route46–48. For example, prenyl diphosphates, geranyl diphosphate (GPP), farnesyl diphosphate (FPP), and geranylgeranyl diphosphate are formed when the allylic isoprenoid diphosphate (DMAPP) combines with one or more IPP molecules to produce the 1–4 linkage characteristic of head–to–tail condensation (GGPP). These two basic five/four-carbon building blocks that make up isoprenoid molecules46–48.

Fig. 7. Reductive coupling of terpenols with alkynes.

A Scope of terpenols. B Scope of alkynes. C Biosynthetic terpenoid synthesis (previous known). D Co/PC iterative synthesis of terpenol. aThe reaction was performed in 0.2 mmol scale under standard condition B. bThe reaction was performed in 0.3 mmol scale.

To mimic such biosynthetic pathway, we applied the developed methodology for iterative extension of three-carbon building blocks from geraniol derivatives, coupling them with propargyl alcohol through tandem Co-PC reductive coupling with alkyne 1n. This approach led to the sequential synthesis of 8nb, 8ne and 8nf as shown in Fig. 7. Since allylic alcohol 8nb and 8ne-8nf are produced from the reactions involving geranyl carbonate 7b and propargyl alcohol 1n, this product can be readily converted into allylic carbonate substrate through a reaction with ethyl chloroformate, facilitating homologation reactions under standard condition B (Fig. 7, bottom).

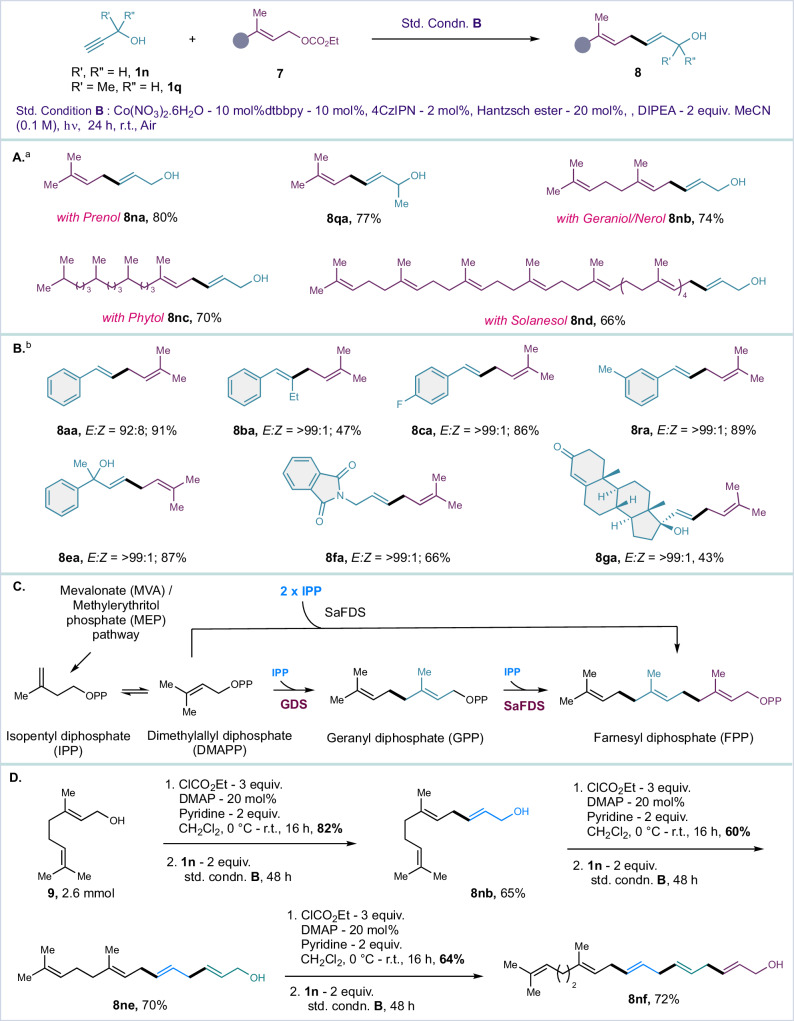

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed to cast light on the reaction mechanism for the cobalt-catalyzed reductive coupling of alkyne and allenyl carbonate, leading to skipped diene. First, we have investigated the mechanistic route for the generation of the low-valent Co(I) species TINT-1 as an active catalyst (Fig. 8a). Under visible light irradiation, the photoexcited T4CzIPN undergoes reductive quenching (SET1) in presence of DIPEA (C1) to generate the radical cation DIPEA•+ (C2) and 4CzIPN−. This step is exergonic by 10.9 kcal/mol with a negligible free energy barrier of 0.4 kcal/mol, estimated using the Marcus-Hush theory (Supplementary Table 13)69–71. On the other hand, single electron transfer from T4CzIPN to QLCoCl2, oxidative quenching, is endergonic by 13.5 kcal/mol with an energy barrier of 13.5 kcal/mol (Supplementary Fig. 17a). Alternatively, the reductive quenching of T4CzIPN by Co(II) is endergonic by 20.7 kcal/mol with an energy barrier of 21.8 kcal/mol (Supplementary Fig. 17b). Similarly, the quenching of T4CzIPN via energy transfer to Co(II) species can be discarded owing to the mismatched energy levels (Supplementary Fig. 18)72. Therefore, calculations indicate that the reductive quenching of T4CzIPN by C1 is favored over both the oxidative, reductive and energy transfer quenching by QLCoCl2. Moreover, considering the excess concentration of C1 compared to QLCoCl2, quenching of T4CzIPN by C1 dominates, and therefore, the reductive cycle is preferred73. The subsequent proton transfer from C2 to C1 results in the protonated amine (C3) and α-amino radical species (C4) via transition state TS-A and an energy barrier of only 0.1 kcal/mol. An exergonic reduction of Co(II) to Co(I) by C4 furnishes the iminium ion C5 with an estimated energy barrier of 2.8 kcal/mol (SET2). The oxidation of C4 by T4CzIPN requires surmounting a high energy barrier of 31.3 kcal/mol, rendering it unattainable under ambient reaction conditions (Supplementary Fig. 19). The subsequent hydrolysis of C5 yields diisopropylammonium cation C8, with the release of acetaldehyde. Importantly, C8 acts as a proton donor in the cobalt catalytic cycle. In line with our calculations, C8 was isolated from the catalytic reaction mixture and the solid-state structure of C8 was further confirmed by X-ray studies (Fig. 8b, for details see: Supplementary Data 1)67. The 1e reduction of Co(I) by 4CzIPN−, leading to Co(0) species, is thermodynamically unfavored (Supplementary Fig. 20), indicating that the Co(I) species starts the cobalt catalytic cycle.

Fig. 8. Energy profile for the formation of C8 and solid-state structure of C8.

a Free energy profile for the generation of TINT-1 and C8 at the M06-D3(SMD, acetonitrile)/def2-TZVPP//PBE-D3/def2-TZVP/def2-SVP level of theory. b X-ray structure of C8 obtained from the catalytic reaction. T = triplet, Q = quartet.

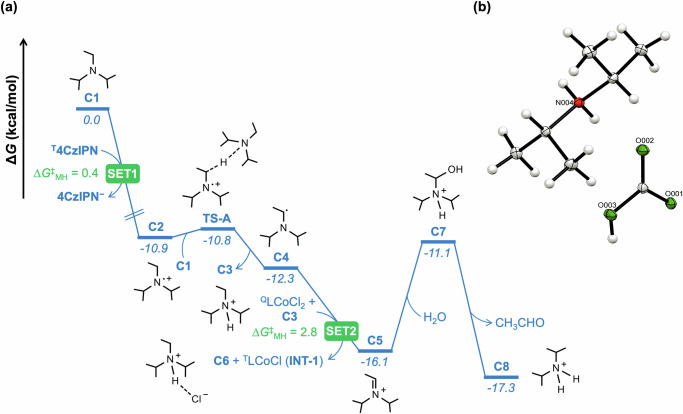

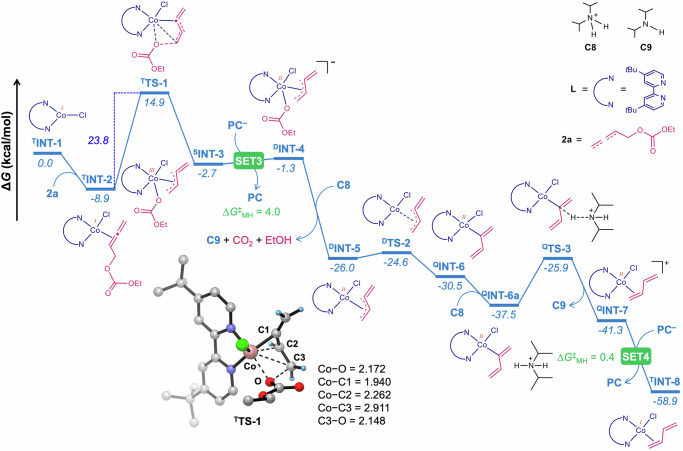

The overall cobalt catalytic cycle is divided into two sections: (i) formation of 1,3-butadiene; and (ii) skipped diene formation in the reaction of 1,3-butadiene bound Co(I) intermediate with alkyne. The first section initiates with the oxidative addition of allenyl carbonate (2a) to TINT-1 (Fig. 9). This step needs to surmount the energy barrier of 23.8 kcal/mol via transition state TTS-1. The protonation of the resulting intermediate SINT-3 at different oxygen centers always yields significantly less stable intermediates (Supplementary Fig. 21). Rather, single electron transfer from 4CzIPN− to SINT-3 leads to a marginally less stable intermediate DINT-4 with an energy barrier of 4.0 kcal/mol. The facile proton transfer from C8 to DINT-4 liberates CO2 and ethanol, giving rise to a remarkably stable intermediate DINT-5. Next, DINT-5 rearranges to QINT-6 with an energy release of 4.5 kcal/mol via transition state DTS-2 and an energy barrier of only 1.4 kcal/mol. Another protonation step from QINT-6 via transition state QTS-3, and an energy barrier of 11.6 kcal/mol, results in QINT-7. This section ends with the highly exergonic one-electron reduction of QINT-7 by 4CzIPN− that furnishes 1,3-butadiene bound Co(I) intermediate TINT-8.

Fig. 9. Free energy profile for the formation of 1,3-diene at the M06-D3(SMD, acetonitrile)/def2-TZVPP//PBE-D3/def2-TZVP/def2-SVP level of theory.

Optimized geometry of the transition state TTS-1 with selected bond distances in angstroms (Å). Only selected hydrogen atoms are shown for clarity. PC = 4CzIPN. S = singlet, D = doublet, T = triplet, Q = quartet.

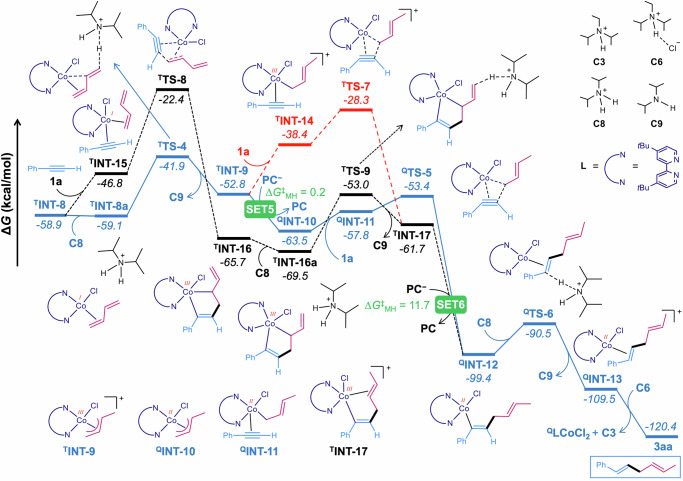

Thereafter, we explored different reaction channels for the generation of the skipped diene starting from TINT-8 (Fig. 10). In the favourable route (blue pathway), TINT-8 undergoes protonation by C8 to generate the slightly less stable electrophilic π-allyl Co(III) intermediate TINT-9, with an energy barrier of 17.2 kcal/mol. One-electron reduction of TINT-9 (SET5) results in QINT-10, exergonic by 10.7 kcal/mol. The alkyne (1a) coordination to QINT-10 generates slightly less stable intermediate QINT-11. The subsequent migratory insertion of phenylacetylene into the Co−C bond in QINT-11, from its less hindered site, leads to a notably stable intermediate QINT-12 via transition state QTS-5. The insertion step needs to overcome an energy barrier of 10.1 kcal/mol which is appreciably lower than the energy barrier of 18.4 kcal/mol computed for the insertion of phenylacetylene from its more hindered site leading to the branched selective product 3aa′ (Supplementary Fig. 22). Protodemetallation of QINT-12, via transition state QTS-6 and an energy barrier of 8.9 kcal/mol, delivers the desired skipped diene bound Co(II) intermediate QINT-13. Finally, the product (3aa) is liberated, and the Co(II) catalyst gets regenerated by chloride transfer from C6.

Fig. 10. Free energy profile for the formation of skipped diene at the M06-D3(SMD, acetonitrile)/def2 TZVPP//PBE-D3/def2-TZVP/def2-SVP level of theory.

PC = 4CzIPN, T = triplet, Q = quartet.

An alternative route emerging from TINT-9 (red pathway), consisting of alkyne coordination/migratory insertion in Co(III) species prior to reduction (SET6), requires a noticeably higher energy barrier of 24.5 kcal/mol, and thus can be discarded. In another alternative route for the generation of QINT-12 (black pathway), alkyne coordination/migratory insertion followed by protonation before single electron transfer (SET6) demands a drastically high energy barrier of 36.5 kcal/mol, and therefore can be ruled out. In conclusion, the theoretical calculations suggest the reaction to proceed through the Co(II)−Co(I)−Co(III) pathway, and the oxidative addition of allenyl carbonate to LCo(I)−Cl is the rate-limiting step.

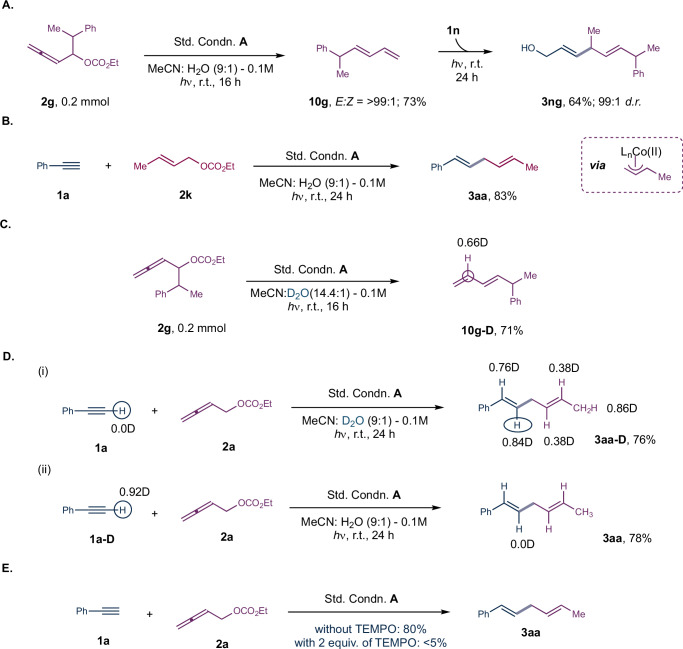

Several control experiments were conducted to further validate the reaction mechanism, as displayed in Fig. 11. To confirm the involvement of 1,3-diene as possible reaction intermediate, we carried out a reaction with allenyl carbonate 2 g in the absence of alkyne under standard conditions, resulting in the formation of mono-substituted 1,3-diene 10 g in 73% yield with the E/Z ratio of 99:1 (Fig. 11A).

Fig. 11. Control studies, labelling and radical scavenging experiments.

A Evidence for 1,3-butadiene formation. B Indirect evidence for Co(II)-π-allylic pathway. C D-Scrambling in 1,3-butadiene formation step. D D-scrambling in 1,4-skipped diene. E Radical quenching experiment.

The isolated diene 10 g was further subjected with propargyl alcohol 1n and produced the corresponding regioselective skipped diene (3 ng) as a single isomer in 64% yield. Furthermore, to confirm the involvement of the π-allyl cobalt(II) intermediate, crotyl carbonate (2k) was employed as the allyl source alongside 1a, providing the expected skipped diene 3aa (Fig. 11B).This suggests that the in situ generated π-allyl Co(III) intermediate (INT-9 in Fig. 10) might further generate π-allyl Co(II) intermediate (INT-10) via SET, which could be responsible for further reaction with alkyne. To better understand the role of water in protodemetallation step, we performed the reaction in presence of D2O. The allenyl carbonate 2 g under standard conditions A, in absence of alkyne in CH3CN:D2O as the solvent, produced mono-substituted-1,3-butadiene 10g-D in 71% isolated yield, with 66% deuterium incorporation at the C-3 carbon of the diene (Fig. 11C). This suggests the involvement of PCET (SET followed by H+ addition) during the formation of 1,3-diene from allenyl carbonate (step II to V of the mechanism in Fig. 12). Additionally, a deuterium scrambling study was performed in the presence of alkyne (1a or 1a-D), and analysis of the isolated skipped diene (3aa-D) revealed that the incorporation of deuterium at various positions: 86% deuterium incorporation at the methyl carbon, 38% deuterium incorporation at both the C-4 and C-5 carbon, 84% deuterium incorporation at C-2 carbon and 76% deuterium incorporation at C-1 carbon respectively (Fig. 11D(i)). These results indicate the involvement of π-allyl cobalt intermediate during the catalytic cycle, suggesting that the acidic acetylenic proton might have undergone deuterium exchange prior to the coordination to the low-valent cobalt center. To further validate these results, deuterated phenyl acetylene (1a-D, 92%D) was subjected to the reaction conditions in presence of H2O, yielded skipped diene 3aa with complete loss of deuterium at C-2 carbon (Fig. 11D(ii)). Finally, we conducted a control experiment with 2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-1-piperidinyloxy (TEMPO) that resulted in <5% of the product formation suggesting that the in situ generated low-valent cobalt might have trapped by the radical scavenger (Fig. 11E).

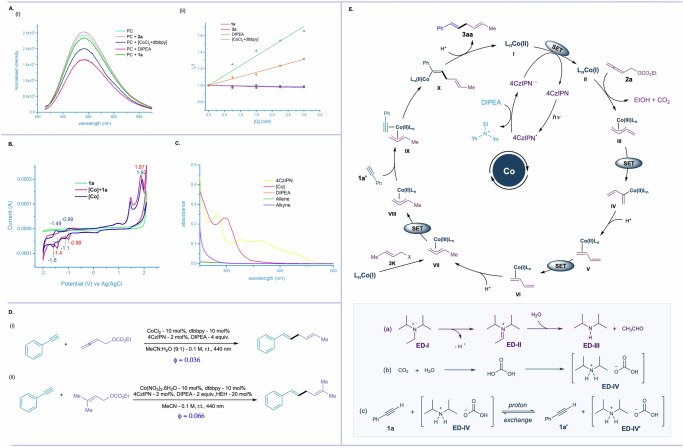

Fig. 12. Mechanistic studies and plausible mechanism.

A Fluorescence quenching studies. B Cyclic voltametric study. C UV-Vis study. D Quantum yield. E Proposed mechanism.

Furthermore, fluorescence quenching studies revealed that both DIPEA and cobalt-complex could act as efficient electron donor to reduce the PC* to PC•− (Fig. 12A). Due to the higher concentration and quenching rate constant of DIPEA, it effectively reduces the PC and thus would initiate the SET cycle, which is also consistent with the DFT calculations. From cyclic voltametric (CV) studies, the reduction potential of CoCl2(dtbbpy) was determined, showing two reduction peaks corresponding to the CoII/CoI reduction (−1.1 V vs. Ag/AgCl) and the CoI /Co0 reduction (−1.6 V vs. Ag/AgCl) (Fig. 12B). The peaks were shifted towards the higher voltage upon addition of phenylacetylene (1a). The UV-Vis absorption spectra of all the reaction components ruled out the involvement of energy transfer (EnT) for the coupling reaction (Fig. 12C). The quantum yield of the reductive coupling reaction was found to be 0.036 and 0.066 for the allenyl carbonate and allyl carbonate with alkyne respectively, indicating that the coupling reactions are not a photo – initiated radical chain processes but rather photocatalyzed process (Fig. 12D). Based on the control experiments, mechanistic studies, comprehensive DFT studies and relevant reports from the literature60–62,73–75, a plausible mechanism for the coupling reaction is proposed, as shown in Fig. 12E. Under photo-irradiation, 4CzIPN undergoes excitation, and the excited photocatalyst 4CzIPN* (Ered* = 1.35 V vs SCE in MeCN) first undergoes reductive quenching in presence of DIPEA (electron donor, ED) to generate radical cation DIPEA•+ and 4CzIPN•− via SET. The reduced photocatalyst 4CzIPN•− has the potential to reduce Co(II)/dtbbpy system to Co(I)/dtbbpy, thereby regenerating 4CzIPN for the next cycle and forming low-valent Co(I) intermediate (II). This in situ-generated low-valent Co(I) intermediate undergoes oxidative addition with allenyl carbonate (2a) to generate π-allyl-Co(III) intermediate (III). At this stage, intermediate III undergoes SET followed by protonation to generate 1,3-diene bound Co(II) intermediate (V) which is well supported by the outcome of both control experiments and DFT studies. Intermediate V undergoes a SET followed by protonation, yielding the electrophilic π-allyl-Co(III) intermediate (VII). Alternatively, π-allyl-Co(III) intermediate (VII) can be directly formed through the oxidative addition of allyl carbonate 2k. This is followed by SET, resulting in the electron-rich π-allyl-Co(II) intermediate (VIII), which then coordinates with the alkyne (1a′) and undergoes migratory insertion at the less hindered site, leading to the formation of intermediate-X.

Finally, protodemetallation of the vinyl cobalt species liberates the desired skipped diene 3aa, releasing the Co(II) pre-catalyst (I) for the next catalytic cycle. We next study the fate of the in situ generated radical cation DIPEA•+. A careful analysis of the reaction mixture revealed that the in situ-generated radical cation DIPEA•+ undergoes hydrolysis, generating diisopropyl amine. Simultaneously, the liberated CO2 from allenyl carbonate, in the presence of water, produces carbonic acid in the same pot. Both diisopropyl amine and carbonic acid couple to produce the diisopropylammonium bicarbonate (ED-IV) and the same is confirmed by the X-ray crystallography67. This proton donor intermediate is isolated under the photo reductive coupling with Co/4CzIPN catalytic system in the presence of DIPEA. The deuterium scrambling study with phenyl acetylene (1a) likely underwent proton exchange with diisopropylammonium bicarbonate (ED-IV), serving as the in situ generated proton donor to yield terminal alkyne 1a' prior to the coordination and migratory insertion between the Co−C bond.

Discussion

In summary, we present an efficient one-step reductive protocol utilizing a dual cobalt/organophotoredox strategy for synthesizing diverse skipped dienes, crucial motifs in therapeutics and fatty acids. Our method achieves excellent regio- and stereoselectivity by employing allenyl or allyl carbonates as π-allyl sources, facilitating the direct conversion of various alkynes, including terminal, propargylic, and internal alkynes, into skipped dienes. This protocol’s versatility is further demonstrated by its compatibility with allyl carbonates, including prenyl derivatives. Notably, the biomimetic homologation of natural terpenols into synthetic analogs through iterative prenylation showcases the potential for complex molecule synthesis. Through experimental studies and detailed DFT analyses, we demonstrate that 1,3-dienes are generated in situ from allenyl carbonate via oxidative addition followed by proton-coupled electron transfer mechanism. Further protonation of Co(I)-diene intermediate leads to π-allyl-Co(III). Alternatively, this species can be directly formed through the oxidative addition of allyl carbonate with Co(I). The π-allyl-Co(III) intermediate undergoes single electron transfer to generate the π-allyl-Co(II) intermediate. The migratory insertion of alkyne with this intermediate is energetically favorable over π-allyl-Co(III). This synthetic method not only expands the repertoire for constructing skipped dienes but also holds significant promise for targeted synthesis, particularly in pharmaceutical and bioactive molecule applications.

Methods

General Procedure A for the Synthesis of 1,4-skipped Dienes from Allenyl Carbonate

In an oven-dried 4 mL glass vial equipped with magnetic stirrer, was charged with 4CzIPN (0.006 mmol, 2 mol%), dtbbpy (0.03 mmol, 10 mol%), CoCl2 (0.03 mmol, 10 mol%), allenyl carbonate 2 (0.3 mmol, 1 equiv.) and alkyne 1 (0.6 mmol, 2 equiv.) or propargyl alcohol 1’ (1.2 mmol, 4 equiv.), DIPEA (1.2 mmol, 4 equiv.), MeCN:H2O (9:1 v/v, 3 mL, 0.1 M) under open air and the reaction vial was sealed with cap and Teflon. The vial was exposed to Kessil blue LED (wavelength 440 nm) for 24 h at room temperature. After 24 hours, all the volatiles were removed under reduced pressure and the crude product was purified through column chromatography using petroleum ether/ethyl acetate as the eluent to give the desired product.

General Procedure B for the Synthesis of 1,4-skipped Dienes from Allyl Carbonate

In an oven-dried 4 mL glass vial equipped with magnetic stirrer, was charged with 4CzIPN (0.004 mmol, 2 mol%), dtbbpy (0.02 mmol, 10 mol%), Co(NO3)2.6H2O (0.02 mmol, 10 mol%), allyl carbonate 7 (0.2 mmol, 1 equiv.) and propargyl alcohol (0.4 mmol, 2 equiv.), Hantzsch ester (0.04 mmol, 20 mol%), DIPEA (0.4 mmol, 2 equiv.), MeCN (2 mL, 0.1 M) under open air and the reaction vial was sealed with cap and Teflon. The vial was exposed to Kessil blue LED (wavelength 440 nm) for 24 h at room temperature. After 24 hours, all the volatiles were removed under reduced pressure and the crude product was purified through column chromatography using petroleum ether/ethyl acetate as the eluent to give the desired product.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Source data

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge SERB (CRG/2020/001282) for research funding to B.S. and IITK for infrastructure. S.P. and D.S. thank CSIR for their fellowship. S.D., B.M., and L.C. acknowledge the KAUST Supercomputing Laboratory for providing computational resources of the supercomputer Shaheen III. L.C. thanks KAUST for financial support by grants URF/1/4384-01-01 and URF/1/4701-01-01. We thank Dr. Apparao Draksharapu and Ms. Pragya Arora for UV-Vis and CV measurements and their insightful discussions.

Author contributions

S.P., D.S., and B.S. conceived the concept. S.P. and D.S. performed all the reactions and analyzed the products. S.D., B.M., and L.C. designed and performed all the computational studies and analyze the results. S.P. performed X-ray diffraction analysis and analyzed the structure. The manuscript was written through contribution of all authors.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Bart Limburg, Naohiko Yoshikai and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

Supplementary information and details about the chemical compounds related to this paper can be found at www.nature.com/ncomms. The data supporting the findings of this study are included in the paper or the Supplementary Information and are also available upon request from the corresponding author. Crystallographic data for the structures discussed in this article have been submitted to the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center, with deposition number CCDC 2307953 (C8 or ED-IV) and further details can be accessed through supplementary data. Copies of the data can be accessed free of charge at https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/. The coordinates of the optimized structures are provided as source data. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Luigi Cavallo, Email: luigi.cavallo@kaust.edu.sa.

Basker Sundararaju, Email: basker@iitk.ac.in.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-024-54718-9.

References

- 1.Krey, G. et al. Fatty acids, eicosanoids, and hypolipidemic agents identified as ligands of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors by coactivator-dependent receptor ligand assay. Mol. Endocrinol.11, 779–791 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ringbom, T. et al. COX-2 inhibitory effects of naturally occurring and modified fatty acids. J. Nat. Prod.64, 745–749 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petrunicia, G., Shellnut, Z., Elahi-Mohassel, S., Alishetty, S. & Paige, M. Skipped diene in natural product synthesis. Nat. Prod. Rep.38, 2187–2213 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sato, T., Suto, T., Nagashima, Y., Mukai, S. & Chida, N. Total synthesis of skipped diene natural products. Chem. Asian J.10, 2486–2502 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greth, K., Washausen, P., Höfle, G., Irschik, H. & Reichenbach, H. Antibiotics from gliding bacteria. The jerangolids: a family of new antifungal compounds from Sorangium Cellulosum (myxobacteria): production, physico-chemical and biological properties of Jerangolid. J. Antibiot.49, 71–75 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McNally, M. & Capon, R. J. Phorbasin B and C: novel diterpenes from a Southern Australian marine sponge, phorbas species. J. Nat. Prod.64, 645–647 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pospíšil, J. & Markό, E. I. Total synthesis of Jerangolid D. J. Am. Chem. Soc.129, 3516–3517 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Macklin, T. K. & Micalizio, G. C. Total Synthesis and Structure Elucidation of (+)-Phorbasin C. J. Am. Chem. Soc.131, 1392–1393 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhurkin, F. E. & Hu, X. γ-Selective Allylation of (E)-Alkenylzinc Iodides Prepared by Reductive Coupling of Arylacetylenes with Alkyl Iodides. J. Org. Chem.81, 5795–5802 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamilton, J. Y., Sarlah, D. & Carreira, E. M. Iridium-Catalyzed Enantioselective Allylic Vinylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc.135, 994–997 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hart, D. W., Blackburn, T. F. & Schwartz, J. Hydrozirconation. III. Stereospecific and regioselective functionalization of alkylacetylenes via vinylzirconium(IV) intermediates. J. Am. Chem. Soc.97, 679 (1975). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamilton, J. Y., Sarlah, D. & Carreira, E. M. Iridium-Catalyzed Enantioselective Allylic Vinylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc.135, 994–997 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kabalka, G. W. & Al-Masum, M. Microwave-Enhanced Palladium-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions of Potassium Vinyltrifluoroborates and Allyl Acetates: A New Route to 1,4-Pentadienes. Org. Lett.8, 11–13 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ilies, L., Yoshida, T. & Nakamura, E. Iron-Catalyzed Chemo- and Stereoselective Hydromagnesiation of Diarylalkynes and Diynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc.134, 16951–16954 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee, Y., Akiyama, K., Gillingham, D. G., Brown, M. K. & Hoveyda, A. H. Highly Site- and Enantioselective Cu-Catalyzed Allylic Alkylation Reactions with Easily Accessible Vinylaluminum Reagents. J. Am. Chem. Soc.130, 446–447 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gao, F., Carr, J. L. & Hoveyda, A. H. Copper-Catalyzed Enantioselective Allylic Substitution with Readily Accessible Carbonyl- and Acetal-Containing Vinylboron Reagents. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed.51, 6613–6617 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yadav, J. S., Reddy, B. V. S., Reddy, P. M. K. & Gupta, M. K. Zn/[bmim] PF6-Mediated Markovnikov Allylation of Unactivated Terminal Alkynes. Tetrahedron Lett.46, 8411–8413 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ranu, B. C. & Majee, A. Indium-Mediated Regioselective Markovnikov Allylation of Unactivated Terminal Alkynes. Chem. Commun.1225, 1226 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fujiwara, N. & Yamamoto, Y. Allyl- and Benzylindium Reagents. Carboindation of Carbon−Carbon and Carbon−Nitrogen Triple Bonds. J. Org. Chem.64, 4095–4101 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee, P. H., Heo, Y., Seomoon, D., Kim, S. & Lee, K. Regioselective Allylgallation of Terminal Alkynes. Chem. Commun.1874, 1876 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yasui, H., Nishikawa, T., Yorimitsu, H. & Oshima, K. Cobalt-Catalyzed Allylzincations of Internal Alkynes. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn.79, 1271–1274 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Snider, B. B. Lewis-Acid-Catalyzed Ene Reactions. Acc. Chem. Res.13, 426–432 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoffmann, H. M. R. The Ene Reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.8, 556–577 (1969). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trost, B. M., Probst, G. D. & Schoop, A. Ruthenium-Catalyzed Alder-Ene Type Reactions. A Formal Synthesis of Alternaric Acid. J. Am. Chem. Soc.120, 9228–9236 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hilt, G. & Treutwein, J. Cobalt-Catalyzed Alder-Ene Reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.46, 8500–8502 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Todd, D. P., Thompson, B. B., Nett, A. J. & Montgomery, J. Deoxygenative C-C bond forming processes via a net four-electron reductive coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc.137, 12788–12791 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu, G. et al. Ligand-controlled regiodivergent and enantioselective copper-catalyzed hydroallylation of alkynes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.56, 13130–13134 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mailig, M., Hazra, A., Armstrong, M. K. & Lalic, G. Catalytic anti-Markovnikov hydroallylation of terminal and functionalized internal alkynes: synthesis of skipped dienes and trisubstituted alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc.139, 6969–6977 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ji, D.-W. et al. A regioselectivity switch in Pd-catalyzed hydroallylation of alkynes. Chem. Sci.10, 6311–6315 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen, J., Ying, J. & Lu, Z. Cobalt-catalyzed branched selective hydroallylation of terminal alkynes. Nat. Commun.13, 4518 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arndt, M., Dindaroğlu, M., Schmalz, H.-G. & Hilt, G. Gaining absolute control of the regiochemistry in the cobalt-catalyzed 1,4-hydrovinylation reaction. Org. Lett.13, 6236 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hilt, G., du Mesnil, F.-X. & Lüers, S. An Efficient Cobalt(I) Catalyst System for the Selective 1,4-hydrovinylation of 1,3-Dienes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed.40, 387 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Page, J. P. & RajanBabu, T. V. Asymmetric Hydrovinylation of 1-Vinylcycloalkenes. Reagent Control of Regio- and Stereoselectivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc.134, 6556 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sharma, R. K. & RajanBabu, T. V. Asymmetric hydrovinylation of unactivated linear 1,3-dienes. J. Am. Chem. Soc.132, 3295 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang, A. & RajanBabu, T. V. Hydrovinylation of 1,3-dienes: a new protocol, an asymmetric variation, and a potential solution to the exocyclic side chain stereochemistry problem. J. Am. Chem. Soc.128, 54 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moreau, B., Wu, J. Y. & Ritter, T. Iron-Catalyzed 1,4-Addition of α-Olefins to Dienes. Org. Lett.11, 337 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ikeda, S.-I., Cui, D.-M. & Sato, Y. Regio- and Stereoselective Synthesis of 3,6-Dien-1-ynes by Nickel- and Alkynyltins. J. Org. Chem.59, 6877–6878 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ikeda, S.-I., Miyashita, H. & Sato, Y. Tandem coupling of allyl electrophiles, alkynes and Me3Al or Me3Zn in the presence of nickel catalyst. Organometallics17, 4316–4318 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mori, T., Nakamura, T. & Kimura, M. Stereoselective coupling reaction of dimethylzinc and alkyne toward nickelacycles. Org. Lett.13, 2266–2269 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li, W., Yu, S., Li, J. & Zhao, Y. Nickel-catalyzed allylmethylation of alkynes with allylic alcohols and AlMe3: facile access to skipped dienes and trienes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.59, 14404–14408 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mateos, J., Rivera-Chao, E. & Fañanás-Mastral, M. Synergistic copper/palladium catalysis for the regio- and stereoselective synthesis of borylated skipped dienes. ACS Catal.7, 5340–5344 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suilman, A. M. Y., Ahmed, E.-A. M. A., Gong, T.-J. & Fu, Y. Cu/Pd-catalyzed cis-borylfluoroallylation of alkynes for the synthesis of boryl-substituted monofluoroalkenes. Org. Lett.23, 3259–3263 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vázquez-Galiñanes, N., Velo-Heleno, I. & Fañanás-Mastral, M. Bifuntional skipped dienes through Cu/Pd-catalyzed allylboration of alkynes with B2Pin2 and vinyl epoxides. Org. Lett.24, 8244–8248 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li, W., Yu, S., Li, J. & Zhao, Y. Nickel-catalyzed allylmethylation of alkynes using allylic alcohols and AlMe3: a facile access to skipped dienes and trienes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.59, 14404–14408 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McCammant, M. S. & Sigman, M. S. Development and investigation of a site selective palladium-catalyzed 1,4-difunctionalization of isoprene using pyridine-oxazoline ligands. Chem. Sci.6, 1355 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kellogg, B. A. & Poulter, C. D. Chain Elongation in the Isoprenoid Biosynthetic Pathway. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol.1, 570–578 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kuzuyama, T. & Seto, H. Diversity of the biosynthesis of the isoprene units. Nat. Prod. Rep.20, 171–183 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Poulter, C. D. Biosynthesis of non-head-to-tail Terpenes. Formation of 10-1 and 10-3 linkages. Acc. Chem. Res.23, 70–77 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Levin, M. D., Kim, S. & Doste, F. D. Photoredox catalysis unlocks single-electron elementary steps in transition metal-catalyzed cross-coupling. ACS Cent. Sci.2, 293–301 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hopkinson, M. N., Tlahuext-Aca, A. & Glorius, F. Merging visible light photoredox and gold catalysis. Acc. Chem. Res.49, 2261–2272 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Twilton, J. et al. The merger of transition metal and photocatalysis. Nat. Rev. Chem.1, 0052 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Milligan, J. A., Phelan, J. P., Badir, S. O. & Molander, G. A. Alkyl carbon-carbon bond formation by nickel/photoredox cross-coupling. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.58, 6152–6163 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hossain, A., Bhattacharya, A. & Reiser, O. Copper’s rapid ascent in visible-light photoredox catalysis. Science364, eaav9713 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kojima, M. & Matsunaga, S. The merger of photoredox and cobalt catalysis. Trends Chem.2, 410–426 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang, H.-H., Chen, H., Zhu, C. & Yu, S. A review of enantioselective dual transition metal/photoredox catalysis. Sci. China.: Chem.63, 637–647 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chan, A. Y. et al. Metallaphotoredox: The Merger of Photoredox and Transition Metal Catalysis. Chem. Rev.122, 1485–1542 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gosmini, C., Bégouin, J.-M., & Moncomble, A. Cobalt-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions. Chem. Commun. 3221–3233 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Röse, P. & Hilt, G. Cobalt-Catalyzed Bond Formation Reactions; Part -2. Synthesis48, 463–492 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Joseph, E. & Tunge, J. A. Copper-catalyzed allylic alkylation at sp3-carbon centers. Chem. Eur. J.30, e202401707 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tang, T. et al. Investigating oxidative addition mechanisms of allylic electrophiles with low-valent Ni/Co catalysts using electroanalytical and data science techniques. J. Am. Chem. Soc.144, 20056–20066 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Andreetta, P. et al. Experimental and computation studies on cobalt(I)-catalyzed regioselective allylic alkylation reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.62, e202310129 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Joseph, E., Hernandez, R. D. & Tunge, J. A. Cobalt-catalyzed decarboxylative allylation: development and mechanistic studies. Chem. Eur. J.29, e202302174 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shen, Z. et al. A computational study on cobalt-catalyzed allylic substitution of racemic allylic carbonates with amines: inner-sphere C-N reductive elimination and origins of regio- and enantioselectivities. Org. Chem. Front.10, 2976–2987 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li, Y.-L., Li, W.-D., Gu, Z.-Y., Chen, J. & Xia, J.-B. Photoredox Ni-catalyzed branch-selective reductive coupling of aldehydes with 1,3-dienes. ACS Catal.10, 1528–1534 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xue, S. et al. Dual cobalt/organophotoredox catalysis for diastereo- and regioselective 1,2-difunctionalization of 1,3-diene surrogates creating quaternary carbon centers. ACS Catal.12, 3651–3659 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pradhan, S., Chakraborty, P., Paira, S. & Sundararaju, B. Allenyl carbonate as a butadiene surrogate in cobalt-catalyzed crotylation of aldehydes. J. Org. Chem.88, 5893–5899 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.CCDC 2307953 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. The Supporting data also provides additional information.

- 68.Shee, M., Shah, Sk. S. & Singh, N. D. P. Photocatalytic conversion of benzyl alcohols/methyl arenes to aryl nitriles via H-abstraction by azide radical. Chem. Eur. J.26, 14070–14074 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Maity, B., Dutta, S. & Cavallo, L. The mechanism of visible light-induced C–C cross-coupling by Csp3–H bond activation. Chem. Soc. Rev.52, 5373–5387 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Marcus, R. A. On the Theory of oxidation-reduction reactions involving electron transfer. J. Chem. Phys.24, 966–978 (1956). [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hush, N. S. Adiabatic theory of outer sphere electron-transfer reactions in solution. Trans. Faraday Soc.57, 557–580 (1961). [Google Scholar]

- 72.Qi, Z.-H. & Ma, J. Dual role of a photocatalyst: generation of Ni(0) catalyst and promotion of catalytic C−N bond formation. ACS Catal.8, 1456–1463 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 73.Maity, B. et al. Mechanistic insight into the photoredox-nickel-HAT triple catalyzed arylation and alkylation of α‑amino Csp3−H bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc.142, 16942–16952 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Limburg, B., Cristòfol, À. & Kleij, A. W. Decoding key transient inter-catalyst interactions in a reductive metallaphotoredox-catalyzed allylation reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc.144, 10912–10920 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gu, Z.-Y., Li, W.-D., Li, Y.-L., Cui, K. & Xia, J.-B. Selective reductive coupling of vinyl azaarenes and alkynes via photoredox cobalt dual catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.62, e202213281 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

Supplementary information and details about the chemical compounds related to this paper can be found at www.nature.com/ncomms. The data supporting the findings of this study are included in the paper or the Supplementary Information and are also available upon request from the corresponding author. Crystallographic data for the structures discussed in this article have been submitted to the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center, with deposition number CCDC 2307953 (C8 or ED-IV) and further details can be accessed through supplementary data. Copies of the data can be accessed free of charge at https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/. The coordinates of the optimized structures are provided as source data. Source data are provided with this paper.