Summary

The care for cystic fibrosis (CF) has dramatically changed with the development of modulators, correctors, and potentiators of the CFTR molecule, which lead to improved clinical status of most people with CF (pwCF). The modulators influence phospholipids and ceramides, but not linoleic acid (LA) deficiency, associated with more severe phenotypes of CF. The LA deficiency is associated with upregulation of its transfer to arachidonic acid (AA). The AA release from membranes is increased and associated with increase of pro-inflammatory prostanoids and the characteristic inflammation is present before birth and bacterial infections. Docosahexaenoic acid is often decreased, especially in associated liver disease Some endogenously synthesized fatty acids are increased. Cholesterol and ceramide metabolisms are disturbed. The lipid abnormalities are present at birth, and before feeding in transgenic pigs and ferrets. This review focus on the lipid abnormalities and their associations to clinical symptoms in CF, based on clinical studies and experimental research.

Subject areas: Health sciences, Medicine, Medical specialty, Clinical genetics, Internal medicine, Respiratory medicine, Human genetics, Molecular biology

Graphical abstract

Health sciences; Medicine; Medical specialty; Clinical genetics; Internal medicine; Respiratory medicine; Human genetics; Molecular biology.

Introduction

Although 35 years have passed since the gene for cystic fibrosis (CF), the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), was identified and more than 2200 mutations have been registered (The Clinical and Functional Translation of CFTR (CFTR2); listed at http://cftr2.org), a cure for the disease has not yet been found. Only about 30% of gene variants of the CFTR, a chloride and bicarbonate channel, have been found clinically relevant for the CF disease. Despite extensive research in the latest decades, difficulties remain to fully explain the link between the channel and many of the clinical symptoms.1,2 It is also of interest that CF-like phenotypes have been produced in animal experiments by inhibition of nuclear liver X receptor (LXR)β,3,4 and by genetic variants of the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC),5 but the associations to CFTR are not fully explored.

New CFTR modulating therapies with protein chaperones (potentiators-correctors) have made great improvement in life for people with CF (pwCF), but are not available for all patients.6,7,8,9 The latest triple combination, elexacaftor-tezacaftor-ivacaftor (ETI; Kaftrio/Trikafta), has shown important clinical effects related to the most common mutation, Phe508del, with increase of lung function about 14% – much more than previous combinations – and with positive impact on the general clinical status.10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17 This is a large step forward, but can only help pwCF with certain mutations18,19 and has limited influence on the chronic inflammation.20,21,22,23,24 So far, some serious adverse effects have been reported,16,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32 like liver failure29 and psychological disturbances33,34,35,36,37,38

New interest to the lipid disturbances in CF has emerged since the modulators of the CFTR, from Ivacaftor to the latest triple combination ETI, have been shown to interfere with the lipid metabolism, especially with phosphatidylcholine (PC) and ceramides, both in humans39,40,41 and in CF cell cultures.41,42,43,44 Table 1 summarizes studies about lipid interferences with the modulators so far. The cellular membranes are mainly built of phospholipids, cholesterol and ceramides.45 The physiology of proteins in membranes are highly dependent on the lipid structure, which varies between different tissues and different organelles.46,47,48,49,50 It is of interest that it has repeatedly been reported that PC, the dominating phospholipid in the outer cell membrane, has an increased turnover in CF.51,52,53,54,55 Using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time of flight (MALDI-TOF) technique with mass spectrometry, Guerrera et al.56 found that six PC and four lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) molecules were significantly decreased in pwCF with differences between severe and mild phenotypes, corroborating clinical findings that plasma phospholipid profiles in mild phenotypes may not differ from those in healthy controls.57,58,59

Table 1.

Recent update of lipid abnormalities in Cystic Fibrosis in relation to CFTR mutations and CFTR modulators

| Reference | Tissue | Method/Modulator | Lipids | Metabolic effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vitro studies | ||||

| Liessi et al.60 | Human dF508del bronchial cells Review |

Ivacaftor, Lumacaftor, Orkambi, ETI | Ceramides, sphingomyelins, phospholipids, diacylglycerols | ETI, more than other modulators, blocks formation of ceramides from dihydroceramides and downregulates major lysoPC independent of CFTR variants. Associated with less apoptosis. |

| Abu-Arish et al.44 | Human bronchial dF508del and S13F cells | Detergents, Lumacaftor Spectroscopy Immunostaining Short-circuit current |

Membrane lipid order in rafts | CFTR clustering and membrane integration are dependent of membrane lipid order. Defective clustering restored by modulators and detergents. |

| Abu-Arish et al.,61 | Human bronchial cells | Spectroscopy Confocal microscopy |

Cholesterol | Different clustering of CFTR in membranes depending on cholesterol concentration |

| Abu-Arish et al.,62 | Human dF508del bronchial cells | Live cells imaging, Spectroscopy Immunology Ussing chambers VIP, Carbacol |

Cholesterol, ceramides | CFTR surface expression influenced by ceramide-rich platforms aggregated from clusters at stimulation by VIP and carbachol triggered by ASMas. |

| Liessi et al.63 | Human primary bronchial epithelial cells from dF508del, and from M/Min mutations | ETI MS, High pressure chromatography |

Ceramides | ETI impacts conversion of dihydroceramides to ceramides independent of CFTR variants. Suggest neurological risk factor? |

| Schenkel et al.64 | Unilamellar vesicles of phosphatidylcholine (POPC) with CFTR TM loops 3/4 and intervening extramembrane loop ± cholesterol | Lumacaftor Fluorescence microscopy |

Cholesterol, Protein action |

Lumacaftor shields protein from lipid environment improving function/configuration, independent of cholesterol |

| Combined studies | ||||

| Veltman et al.42 | Air-liquid interface in pulmonary cells from CF mice lungs, CF-KO pigs and human CF airway epithelium cultures | Orkambi, ETI Fenretinide LC/MS, protein inflammatory markers, Ussing chambers Inflammatory markers |

Fatty acids, ceramides, cytokines | Improvement of lipid pattern by modulators but persistent inflammation markers and oxidative stress markers. High n-6/n-3 ratio (AA/DHA), and low ceramide levels improved but not normalized by fenretinide and ETI, resp. |

| Centorame et al.,65 | F508deltm1EUR mice, (only 3 mice in each group) in vitro cell lines | ETI Fenretinide GC |

Fatty acid, lipid profiles | Increase of EPA and DHA, decrease of saturated fatty acids. Fenretinide better effect than ETI on lung function, histology, inflammation; combination of drugs similar to fenretinide or even better. Glucosylation of defective CFTR increased by fenretinide and combination with ETI, but not by only ETI. |

| Bae et al.66 |

CFTR+/+ vs. CFTR−/− piglets Comparisons 8 vs. 8 animals, within 12 h from birth Cell culture |

Arteriovenous metabolomics in different organs LC/MS |

Fatty acids, mono-di- and triglycerides, | Increased nonesterified long-chain fatty acids and decreased LA in CF piglets |

| Clinical studies | ||||

| Petersen et al.31 | Blood samples from pwCF Retrospective, observational study, 134 CF adults (female 46%) |

ETI | Cholesterol Lipoproteins | Increase of Cholesterol, LDL-C, obesity and blood pressure |

| Despotes et al.32 | Blood samples from pwCF Retrospective observational study, 41 CF adults (female 66%), aged 16–73 years |

ETI | Cholesterol lipoproteins | Increase of Cholesterol, LDL-C, TC/HDL-C, more in family history of CVD, less in CFLD |

| O'Connor and Seegmiller39 | Blood samples from pwCF G5551D variant Prospective, observational study, 20 children pwCF (female 50%), 20 adults pwCF (female 80%)) |

Ivacaftor | AA, PGE-M, n-3 fatty acids | Decrease of AA and its metabolite PGE-M. No change in n-3 fatty acids. |

| Zardini Buzatto et al.40 | Blood samples from pwCF 42 pwCF (female 60%), aged – 12–34 years. |

HPLC and LC-MS Databases |

Ceramides, sphingomyelins, fatty acids, diacylglycerols | Lipid pattern, especially phosphatidic acids and diacylglycerols, differed by different mutation classes. Five oxidized lipids correlated to FEV1 |

| Lonabaugh et al.67 | Human blood from different variants of pwCF Retrospective chart review study, 128 adults pwCF (female 52%) |

ETI | Cholesterol, Lipo-proteins | ETI increases Cholesterol, LDL-C and HDL-C |

| Patel et al.68 | Human blood from homo and heterozygotes of pwCF dF508del Retrospective study, 137 adults (n = 110) and adolescents (n = 26) (female 40%)) |

ETI | Cholesterol, lipoproteins | ETI increases Cholesterol, LDL-C, HDL-C, S levels of vitamins A and D |

| Tindall et al.69 | Blood samples from pwCF 12 children (female 60%), age 4–20 months. |

Ivacaftor | Fatty acids | Ivacaftor increased total saturated fatty acids, mead acid, palmitic acid and docosatetraenoic acid, indicating EFAD. |

| Tindall et al.70 | Blood samples from pwCF homozygous for F508del Prospective longitudinal study, 21 children (female 61%), aged 2–5.9 years |

Orkambi | Fatty acids, fat soluble vitamin | Lumacaftor/Ivacaftor increased S- retinol. No change in plasma total fatty acids but decrease of ALA and DHA. |

| McDonald et al.71 | Serum from 142 pwCF (4 months-18 years) homo- and heterozygotes for dF508 | Ivacaftor, Orkambi Symdeko |

Fatty acids, lipoproteins | No influence of modulators on EFA deficiency, but some influence on LDL, HDL, VLDL and triglycerides |

| Slimmen LJM et al.72 | Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from 46 pwCF aged 1–5 years. | Lipid mediators at HPLC-tandem MS at 65 samples 8/65 on Orkambi |

Lipid mediators of linoleic acid and arachidonic acid | No influence by modulators. Increase of AA derivatives and decrease of LA derivatives in relation to neutrophiles and pulmonary damage. |

| Yuzyuk et al.73 | Blood samples from 153 pwCF (mean age 10.1 ± 4.7 years). | Ivacaftor, Orkambi, Symdeko, ETI. 65% on modulators for >1 mnth | Lipoproteins | Modulators increased HDL cholesterol, lowered LDL, VLDL and triglycerides comparing to controls. |

AA, arachidonic acid; ALA, alpha linolenic acid; ASMas, acid sphingomyelinase; C, cholesterol; CFLD, cystic fibrosis liver disease; CFLD, cystic fibrosis liver disease; CFTR, Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductive regulator; CVD, cardiovascular diseases; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; EFAD, essential fatty acid deficiency; ETI, Ivacaftor+elexacaftor+tezacaftor; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; HPLC, high-pressure liquid chromatography; LA, linoleic acid; LC, Liquid chromatography; L/HDL, low/high-density lipoprotein; MS, masspectrometry; TM, transmembrane; Orkambi, Ivacaftor+Lumacaftor; Symdeko, Ivacaftor+Tezacaftor.

Linoleic acid (LA, 18:2n-6) is an important component of membrane phospholipids.74,75,76,77 Thus the LA deficiency in CF, which has been repeatedly described since more than 60 years,78 and verified in hematological elements as well as in different other tissues,79,80,81 can be one factor associated with the disturbed channel localization and activities. The composition of fatty acids in membranes is important for the membrane function, influencing transports and metabolism in all cells and tissues,45,46,76,82,83,84,85 and the local tissue balance is not always reflected in the blood.85,86 The essential fatty acids (EFA), their long-chain derivatives and corresponding lipid mediators of the n-6 and the n-3 series, are also important for the inflammatory homeostasis,87 which is seriously disturbed in CF.21,88 Since channels mainly act in membrane rafts, markedly influenced by ceramides63,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96 and cholesterol, the disturbances in these lipids are also important for the channel functions.97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108 The importance of membrane lipids for cell functions and the limitations of modern modulator therapy, hitherto not shown to improve the characteristic lipid abnormalities in CF, are the facts behind this review. The aim is to describe the associations between the lipid divergences, focusing on the n-6 fatty acids, and the clinical symptoms, as a challenge to optimize the treatment of pwCF.

Lipid abnormalities

Fatty acids

The most consistent EFA disturbance in CF fatty acid metabolism is the low concentration of LA in blood; in total lipids, cholesterol esters, phospholipids, platelets and red cell membranes.58,78,79,80,81,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124 Other tissues are more seldom examined, but show marked deficiency, also in comparison with the plasma levels.79,80,81,125 Interestingly, CF-knock out (KO) pigs and ferrets have low LA at birth before feeding and the typical lipid changes are also found in the liver of newborn CF pigs.66,126 Arachidonic acid (AA, 20:4n-6) concentrations varies, but the ratio AA/docosahexaenoic acid (22:6n-3, DHA) is consistently increased.57,81,119,127,128,129 Analyses of the arteriovenous ratio in different organs of newborn CF piglets showed marked increase of AA.66 The long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid (LCPUFA) of the omega-3 series, is often decreased in plasma and tissues, especially in patients with CF related liver disease (CFRLD).130,131 Endogenously synthesized fatty acids, like palmitoleic acid (16:1n-7, PA), oleic acid (18:1 n-9,OA) and eicosatrienoic acid (20:3n-9, Mead acid) are increased in CF,57,110,132,133 reflected in increase of the fatty acid transforming enzymes in CF cells.54 Parts of the typical fatty acid profile have been suggested as markers for the CF diagnosis, e.g., the classical EFA index (Mead acid/AA or expressed triene/tetraene (T/T) ratio),133 the ratio PA/LA113 and the product DHA x LA.134 Algorithms to relate symptoms to low LA concentrations and high AA release, respectively, were suggested for the gastrointestinal tract and the airways135,136 and have gained support in recent studies, as discussed below.

The LA concentration is usually inversely correlated to AA, both in CF,137 some other pathological conditions and in healthy individuals.138,139,140,141 In severe LA deficiency as in malnutrition, not related to CF, AA is generally decreased,142 which observation might have impact also in malnourished pwCF.143 The LA deficiency in CF varies in relation to CFTR variants and to dietary intake.57,119,127,144 Older studies have shown that obligatory heterozygotes for the CFTR variants had slightly different fatty acid profile compared to controls, suggesting a milder fatty acid abnormality.110,115 as also indicated in pwCF with pancreatic sufficiency.114,117 A recent comprehensive study examining the lipid pattern between different classes of mutations confirmed significant differences in relation to the symptomatic spectrum.40

The role of n-3 fatty acids has been extensively discussed after the publication by Freedman et al.145 showing an association between low DHA and abnormal intestinal and pancreatic morphology in CF mice, which improved by DHA supplementation. These improvements were not confirmed in a long-time running study of DHA supplementation in CF mice,146 but showed protection from liver damage, supporting clinical observations of associations between low DHA and liver disease in CF.130,131 Many n-3 supplementation studies in pwCF showed increase of plasma concentrations without clinical improvements,147,148 but a few studies showed a slight decrease of inflammation markers.148,149 In animal studies the DHA concentration varies,150 suggesting that the n-3 abnormality might be secondary, possibly related to long-term increased PC synthesis by the internal pathway.108,151 Although a basic disturbance of DHA in CF pathology is controversial, achievements of adequate concentrations would be of importance because specialized pro-solving mediators (SPM) of the long-chain n-3 fatty acids have a modulatory effect on inflammation.152,153

Ceramides

The role of sphingolipids are multifactorial, and especially the impact of ceramides on the raft process in membranes might be of importance for the action of CFTR.154 An imbalance with an increased ratio between very long chain and long chain ceramides influencing the stability of rafts in cell membranes have been suggested to influence the sensitivity to Pseudomonas infection in pwCF155 and have been connected with increase of inflammatory cytokines.156 Type of sphingolipids are important for protein function and the organization of rafts.157 Their roles in the pathophysiology of CF has mainly been focused on the airways but conclusive results have been restricted due to non-specific antibody results. Interesting results are provided by the supplementation of fenretinide, a synthetic retinoid (N-(4-hydroxy-phenyl retinamide) improving the ceramide balance158 influencing many functions, e.g., in the lungs and improving the AA/DHA ratio.97 Further improvement in lung function and fatty acid status was found in CF KO mice and in Phe508del(tm1EUR) mice by a combined therapy of fenretinide and the modulator ETI.65,159

Cholesterol

Cholesterol is low in serum of pwCF and in CF animal models but usually increased intracellularly.98,99,103,160 A Polish study found significant differences between patients with CFTR mutations associated with severe or mild disease, which differences also referred to other sterols.161 The cholesterol concentration is related to CFTR and fatty acids and its function to stabilize rafts makes its influence on the function of CFTR and other membranous proteins important,67,101,104 especially in the context of disturbed ceramide metabolism, also important for raft building. Its significance in the pathophysiology of CF from a clinical point of view has been limited, but it is interesting that the latest modulators have a great impact on the LDL-cholesterol (Table 1). The oxidation of cholesterol to keto-cholesterol is usually increased,162 which might be related to the generally increased oxidation in CF. The finding of a CF like disease in the LXRβ −/−mice might be related to the impact of defective LXR metabolism on the cholesterol and fatty acid balances.4,163,164,165,166

Associations between clinical symptoms and fatty acid balance

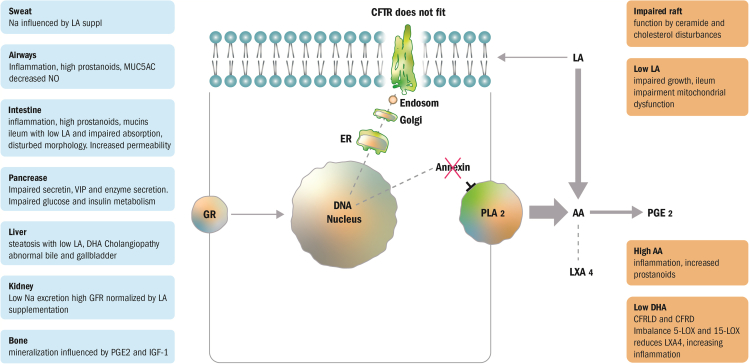

An overview of the symptomatology, which can be related to the fatty acid disturbances in CF, is briefly summarized in Figure 1 and is described for the mainly involved tissues below.

Figure 1.

A basic simplified overview of the hypothetical relation between fatty acid abnormalities in relation to CFTR and clinical implications

CFTR must fit in the membrane for normal function. CFTR variants are processed in the cell and abnormal CFTR are sorted in the endoplasmic reticulum, where most aberrant CFTR is withdrawn, and not all reach the membranes where the localization or function may be impaired in the context of membrane lipids. In normal cells glucocorticoids interfere with the annexin synthesis, which possibly by phosphorylation regulate PLA2 activity by inhibition both of its release of arachidonic acid and activity of COX 2 for PGE2 release. In CF down-regulation of annexin synthesis increases arachidonic acid release with subsequent increasing synthesis from linoleic acid. Thereby linoleic decreases in the membranes interfering with the membrane stereochemistry hampering CFTR activity, and thus impairing the action between CFTR and membranes. Fatty acid composition differs in membranes and organelles, whereby the defective CFTR transfer/function might occur in different compartment localizations in cells and organs. Defective metabolism of ceramides and cholesterol interferes with the raft building (not shown), where the CFTR have its action. Low DHA have been described in cystic fibrosis liver disease (CFRLD) and may be connected with cystic fibrosis related diabetes (CFRD) and may be related to low LXA4. The boxes to the left summarize lipid related processes described in the section “associations between clinical symptoms and fatty acid balance”. GR, Glucocorticoid Receptor; AA, arachidonic acid; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; LA, linoleic acid; PLA2, phospholipase A2,; PGE2, prostaglandin E2; LXA4, lipoxin A4. Differences in arrow size reflect relative transfer activity.

Sweat test

Sweat test is still the most important diagnostic test for CF.167,168 High chloride concentration is associated with genotypes with more severe clinical phenotype.169,170 Sweat chloride concentration are generally reduced by treatment with potentiators-correctors,11,171,172,173 but not by long term fatty acid supplementation.174 On the other hand, LA supplementation was associated with a reduction of sodium in sweat,123,175,176,177 which might be related to ENaC, active in sweat glands.178,179 (cf the kidney section below).

Growth

Impaired growth is common in CF and certainly related to several factors. It is the reason for the general recommendations of very high energy intake.180,181,182 Recommendations of very high fat intake without specifying type of fat have resulted in increasing consumption of saturated fatty acids183 and problem with obesity184,185 increasing the risk for cardiovascular diseases.32,186 This is not seen in pwCF with supplementation of LA, who even can keep normal weight without increased energy intake.187,188 Thus, the classical and often first clinical symptom of EFA deficiency (EFAD) is impaired growth,189,190 which has been observed in pwCF already at birth.191,192 A series of studies from the neonatal screening program for CF in Wisconsin have strongly contributed to the knowledge about the impact of LA on early growth.120,125,144,193 This group has shown that at diagnosis 80% of pwCF with meconium ileus had LA deficiency, as indicated by high Mead acid and its T/T ratio at diagnosis, and that similar pathology were seen in around 50% of newborn pwCF without meconium ileus.120 A relative improvement occurred during infancy, but again the markers deteriorated in late toddler age – prepuberty, which coincides with the well documented dip in growth of pwCF, illustrated in both the European and North American CF patient registries.194,195 The series of papers from the Wisconsin CF Neonatal Screening program have shown that adequate body weight up to 2 years of age was dependent on both energy intake and adequate plasma concentrations of LA.120 Persistently low plasma concentration of LA despite high energy intake resulted in an OR of 7.46 for low growth compared to children with persistently adequate LA concentration and high energy intake, also after adjustment for the initial LA concentrations.144 By maintaining high LA intake above 5% of total energy intake, both the high energy and the LA concentration increased the possibility to catch up weight at 2 years of age (OR 30.6, p = 0.002). The authors concluded that “maintaining normal plasma LA for a prolonged period in addition to sustaining a high energy intake may be important in facilitating adequate weight gain”.144 The “early responders” also required lower energy intake to maintain adequate growth.196 In a follow-up study the Wisconsin group found that the early growth response was associated with better growth and lung function up to 12 years of age and also that pwCF with meconium ileus, who initially had a more severe LA deficiency, continued to be much worse off regarding growth.193,197 Some studies providing LA for shorter times, also reported an improvement in growth.180,198

An association between low LA concentration and poor growth can have different explanations. PwCF have low IGF-1 concentrations,199,200,201,202,203 also found in newborn CF pigs.203 Low levels of IGF-1 correlated to impaired growth,202,204 and to low lean body mass (LBM) in pwCF205 and in transgenic CF mice and rats.206,207 Rosenberg et al.206 reported low growth hormone (GH) levels in CF mice, which might be expected since IGF-1 is a major stimulator for GH. However, the relation between GH and IGF-1 is complex and treatment of pwCF with GH has given conflicting results.202,208,209 No general recommendation for treatment of impaired growth with GH are given,210 which would be logical, if the low GH is only a marker of low IGF-1. A study in healthy infants showed that low IGF-1 was correlated to low LA concentration in serum phospholipids.211 In animal models of EFAD low IGF-1 and growth normalized, when the animal received standard diet normalizing the fatty acid profile.212,213 It would thus be of interest to examine prospectively any correlation between LA concentration, IGF-1 levels, and growth in pwCF.

Another factor related to poor growth is increased energy demand. One suggested cause to high energy demand is an increased resting energy expenditure (REE), a high metabolic turn-over related to the basic CF defect.214,215,216,217,218 It has been shown that severe CF phenotype, e.g., homozygotic for Phe508del, is associated with an increased resting respiratory rate,215,218,219,220 not always associated to pulmonary function, but to the pancreatic status.221 In rats with EFAD an increased basal respiration has been reported and related to growth retardation.222 The molar ratio of PC/phosphatidyl ethanolamine (PE) has been correlated with oxidative capacity and energy production in hepatic mitochondria,223 and the phospholipids of the membranes are crucial for the mitochondrial function.224 Independent of the plasma membrane potential, the mitochondrial membrane potential was decreased in CF airway cells non-related to chloride channel activity but to changed mitochondrial morphology.225 It has been suggested that when mitochondrial activity in CF respiratory cells is below a certain energy threshold,223 mitochondria dictate the conditions of the cells and this may reduce the disposition of the cells to infection related to reduced oxidative stress and altered glucose-related metabolic pathways.226 An increasing interest in the mitochondrial dysfunction in CF cells227,228,229 might possibly elucidate if the high REE is related to the mitochondrial dysfunction and membrane fatty acid configuration in CF.230,231 Cardiolipin (CL) is a major and important phospholipid in mitochondrial inner membranes required for optimal activity of several mitochondrial carrier proteins, and especially tetralinoleoyl-CL is important for optimal activity of the ADP/ATP carrier.232 In liver tissue from pwCF cardiolipin was decreased compared to controls (Strandvik et al. to be published).

Pancreatic function

Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency develops early in about 85% of pwCF and is sometimes present at birth. It has been related to the impaired secretin response and the decreased bicarbonate secretion reducing the intestinal pH, described long before CFTR was identified.233 Interestingly, the impaired pancreas function in a newborn was reversed during Intralipid supplementation,175 but the results could not be replicated although Intralipid resulted in better growth.176 PwCF with more expressed LA deficiency, seem to have CFTR variants associated with more severe phenotypes (classes I-III) including growth impairment and pancreatic insufficiency.57 The pancreatic acini and ducts are obliterated by secretions in CF animal models, and it is not known if the impairment of the pancreatic secretion is initially due to a blockage in secretory ducts.234 In newborn CF pigs, which show EFAD already at birth,126 the acinar function is impaired with lower pH and impaired enzyme expression.235 Also the CF ferrets126 show EFAD at birth and have dilatations of acini gradually developing both endocrine and exocrine pancreatic insufficiency.236 In rats with EFAD, the amylase secretion was impaired and although responding to carbachol stimulation, it was not catching up to control levels.237 AA has been shown to be involved in the carbachol stimulated amylase secretion,238 which might be provided by its products, prostaglandins, as suggested in studies with inhibitors.239 In pancreatic acinar cells, LA much more than AA, stimulated basal amylase secretion by activating protein kinase C in the presence of Ca2+.240 The complex interaction of n-6 fatty acids in enzyme secretion needs further studies to find out if and how they are contributing to the pancreatic pathophysiology in CF.241,242

The endocrine pancreatic function, the insulin secretion, seems to be more impaired in pwCF with low LA concentrations (Hjelte, Strandvik et al., unpublished observation). Especially the first rapid increase of insulin was more impaired in pwCF with LA deficiency compared both to pwCF with normal LA concentrations and to healthy age-matched controls. An inverse correlation was found between plasma LA concentration and HbA1c.243 The increased prevalence of diabetes with age in pwCF suggests a gradual decline in insulin production and/or reduced insulin sensitivity,244 which is preceded by impaired glucose tolerance for years.245 In this context the report that high LA concentrations were protective for type 2 diabetes mellitus is of interest.246 The development of CF related diabetes mellitus (CFRD) is usually associated with clinical deterioration with decrease in weight and pulmonary function.247 In mice with the Phe508del mutations, the impairment in insulin secretion develops during the first 12 weeks of life together with impaired growth and reduced β-cell function.248 It is not clear if the endocrine impairment is independent of or to what extent it is related to the progression of pancreatic exocrine morphological deformation. In transgenic CF pigs the insulin homeostasis improved, when the pancreatic exocrine atrophy was completed, suggesting that the two processes were at least partly independent.249 In cells from human Langerhan’s isles AA was necessary for the glucose-stimulated insulin secretion.250 Humans with type2 diabetes and animals with alloxan-induced diabetes had low long chain fatty acid concentrations and prior administration of AA, EPA and DHA to the animals could protect them from induced diabetes.251 The effect of AA was not mediated by its prostanoid metabolites but by lipoxin LXA4, which production is impaired in CF.252 In this context it is of interest that one study showed that DHA supplementation increased LXA4 by probable switching the balance between 5-LOX and 15-LOX enzymes in the metabolism of AA.253 The role in CF of the balance between LA and AA, as well as that to DHA, and the possible influence on the gradual development of diabetes waits further studies of importance for the possibility of protection.

Gastrointestinal function

The well-known impairment in duodenal bicarbonate secretion is not seen in the stomach of pwCF,254 probably because the gastric bicarbonate secretion is not dependent on CFTR, but on prostaglandins,255,256 which syntheses are generally increased in CF.177,257,258 This might explain the relatively good effect of modern pancreatic enzyme therapy without obvious benefit by bicarbonate supplementation.259 The bicarbonate secretion in duodenum and in the pancreatic ducts is stimulated by secretin, related to a functional CFTR, and is thus impaired in most pwCF.233

PwCF have increased intestinal permeability,260 which correlates to the clinically more severe phenotype Phe508del.261 Membrane phospholipid layers are important for the intestinal permeability and function45 and EFAD relates to both functional and morphological abnormalities.262,263,264 Ileum and colon in mice seem to be especially sensitive for EFAD with a 5-fold decrease of LA concentration in the mucosa compared to controls and without a similar decrease in blood.85 In a study of EFAD in rats, morphological changes were only noticed in ileum and not in jejunum,263 which together with the results in mice with EFAD,85 suggest that ileum is more sensitive to a deficiency state than the rest of the small intestine. Impaired active reabsorption of bile acids in ileum has been documented in both pwCF and animal models.265 Morphological changes and lipid abnormalities have been documented in ileum of CF mice.266 Nitric oxide synthase (NOS2) was reduced in ileum of CF mice in concordance with studies of human trachea, where loss of CFTR reduced NOS2messenger RNA expression and reduced overall NO production.267 Low NO may be related to abnormal lipids and bacterial growth also in the intestine, which has not been shown, but can be indicated by the studies of De Lisle,268 see below. In CFTR-KO mice, lipid mapping with cluster time of flight secondary-ion mass spectrometry (TOF-SIMS) imaging of the colon mucosa and lamina propria, showed low LA concentrations in the epithelial border, and principal component analyses showed marked differences between CF mice and wild type (WT) mice.269 Morphological abnormalities in the intestine of patients with CF are mainly described in ultramicroscopical studies,270 but increase of mucus producing cells are reported also in studies using light microscopy, including organoids.271 Occasionally it has been shown an improvement in pancreatic function by ETI,272 but improvement in general status and body weight suggest higher improvement than verified. Any effect on absorption by ETI treatment have not been studied, but a slight increase in serum levels of vitamin A and D, but not of vitamin E, was reported, although the variation was very large.68 Modern technology opens further possibility to study abnormalities of the lipid structure in relation to physiological disturbances in intact tissues and it would be of importance to further investigate the impact of the lipid abnormalities in the CF intestine in relation to physiology. It has been shown that newborns with meconium ileus often are more LA deficient than pwCF without this complication.120 The fact that ENaC is mainly expressed in colon179,273 implies its tentative importance for the development of meconium ileus and the comparative disease in the adult pwCF, the distal intestinal obstruction syndrome (DIOS).

PwCF have also been described to have inflammation of the intestinal mucosa,274 sometimes even referred to as colitis resembling Crohn's disease.275 Some studies found differences indicating that the inflammation in the CF intestine is different from that observed in inflammatory bowel disease, with higher fecal calprotectin and impaired growth.88,276,277,278,279 In a small study in pwCF with liver disease 4/11 reduced fecal calprotectin during 6 months of ETI treatment and changed the microbiota, but the study did not give any data of feeding and antibiotic treatment during the study period.280 In the intestine of transgenic CF mice there was a marked change in phospholipid and eicosanoid metabolism with high activity of COX 2 and its inflammatory product, PGE2.268 This might be related to high liberation of AA in the intestine, and might have relevance for the increased mucus production, similar to what has been shown in the airways, where high activity of PLA2 was associated with increase of mucins.281 The lipid abnormalities together with the impaired secretion by a dysfunctional CFTR and ENaC282 might contribute to the mucus abnormality increasing the risk of intussusception in CF.

A disturbed motility has been discussed as a possible factor for the gastrointestinal dysfunction and was shown for the circular muscle in CF mice.283 This was not verified in pwCF during fasting conditions, where differences could neither be seen in the longitudinal nor in the circular muscle contractions compared to non-CF controls.254 Dysbiosis has been verified in several studies and present also in comparisons with the influence of frequent use of antibiotics.284,285 It has been suggested that there is a gut-lung axis implicating that the disturbed intestinal milieu transforms cytokines and others to influence the lungs.286 Maybe surprisingly, no author has suggested that trends in these two organ systems may be related to the general lipid status, which might interfere with mucosal permeability, immunology, bacterial growth, and metabolism. Studies are warranted.

Liver and biliary system

In CF both the liver and biliary tract are involved, and the pathophysiology is not fully understood, since CFTR is not shown to be expressed in the hepatocytes.287,288 On the other hand it has been suggested that small amounts of CFTR may be localized in the intracellular compartments with functions not clearly documented.289 Identification with antibodies may give cross reactivity but combined data do not support an expression in the hepatocytes. Steatosis is the most common finding and has sometimes been described as excessive,290 but mostly as a more or less distributed finding in the microscopical analyses of liver biopsies and in imaging investigations.291 Steatosis was found to be inversely associated to the LA concentration in plasma phospholipids,291 and CF related liver disease (CFRLD) was associated with lower DHA concentrations.119,130,131 Long-term studies in CF mice supplemented with DHA showed less periportal inflammation compared to a control group146 and some authors suggest that the ratio between AA/DHA in blood cell tissues is related to liver disease in CF and that the disturbed PUFA concentrations might contribute to the unexplained liver affection in many of the pwCF.130,131,146,291,292 Interestingly a long-term supplementation with Intralipid for 3 years showed less steatosis compared with untreated CF controls.293 Steatosis has been suggested to increase the risk of cirrhosis, and periportal fibrosis is common in pwCF and may in 5–10% result in a multinodular cirrhosis.291,294 The Swedish policy to supply LA,291,295 might therefore be a factor contributing to low prevalence of cirrhosis and portal hypertension in Swedish pwCF, shown in comparison with other centers in an international multicenter study comprising more than 1500 pwCF in 11 CF centers in Europe and Australia.296

Morphological signs of inflammation in the liver are relatively rare but a vascular inflammatory component has been discussed as a dominant feature in a smaller number of pwCF, who rapidly developed portal hypertension without cirrhosis.297,298 It would be of interest to study that group of pwCF in relation to lipids since endothelial cells are interactive with blood cells regarding cytokines and eicosanoids.299,300,301

The disturbance in bile acid metabolism and biliary tract abnormalities can be expected since CFTR is expressed in the cholangiocytes, including the gallbladder epithelium. Clinically, disturbed function and anatomy of the gallbladder, such as an enlargement of the latter (less than 10% of pwCF), or a non-visible micro gallbladder (>30%), are the most common findings. Cholangiopathies, visually similar to primary sclerosing cholangitis are not uncommon302 increasing in prevalence with age.303 This has been suggested to be linked to the abnormal CFTR function with sticky secretion, but in electron microscopical analyses of liver biopsies from pwCF the small cholangial ducts were not plugged although biochemically a cholestatic pattern was common.304,305 It is of interest that CFTR variants are frequently found in primary sclerosing cholangitis.306 Malignancy in the biliary system is not unusual in CF, but the risk of colon malignany is greater.307,308

It has been reported that pwCF have an increased fecal bile acid excretion,309 defective bile acid absorption and thus a low bile acid pool size.310 However, this was not confirmed in a study of Swedish pwCF in good clinical condition,311 and the absorption seems very good both after individual bile acid supplementation and after a test meal (Strandvik et al., unpublished observation). It cannot be excluded that the varying results are related to the clinical condition of the pwCF. The bile acid pattern in serum, urine and duodenum showed that patients with CF have increased primary bile acids, cholic and chenodeoxycholic acids; the latter increase mainly related to CFRLD.312,313 The secondary bile acids, known to be more toxic than the primary ones, are sometimes decreased in CF.309,312 Interestingly a recent report found increase of deoxycholic acid, more pronounced in CFRLD without clinical cirrhosis.314 If differences are associated with treatment strategies, including influence from the intestinal microbiome, have not been reported. Interestingly, long-term supplementation of LA resulted in some improvement of the plasma bile acid profile.293 The complex fat metabolism in the liver restrict any suggestions of relation to the impaired metabolism and need more focused studies.

Kidney function

PwCF do not usually present clinical impairment in renal function, except after long-term treatment with toxic drugs, like aminoglycoside antibiotics or after transplantation with extensive immunosuppressive therapy.315 However, the kidneys are involved in CF,316 and pwCF have a delayed renal acidifying capacity, indicating a reduced bicarbonate threshold, which was interpreted as a proximal tubular dysfunction.317,318 This is supported by CFTR being mainly expressed in the proximal tubules and in the collecting ducts, which were shown to have an impaired secretin response long before the gene was discovered.233

Renal sodium excretion is impaired in infants with CF despite supplementation182 and is also lower in children with CF than in controls.317,319 This low excretion was not improved by 10 days of high sodium intake or after intravenously loading with high doses.317 Investigations with 24Na did not indicate sodium depletion.320 Three years of LA supplementation to children with CF resulted in an improvement and even normalization in the renal sodium excretion,318 but since the study was performed before the gene was discovered, differences in relation to mutation were not investigated. The low sodium excretion has also been correlated to poor growth and interpreted as low sodium status despite normal plasma levels of sodium.319,321 ENaC is present in the renal tubules,322,323 and similar hyperactivity as in the airways, might explain the decreased sodium excretion.324,325 The LXR might also influence ENaC mediated sodium reabsorption in collecting duct cells.326 The results, including those in sweat (see above), indicate that the intramembranous ENaC activity directly or indirectly was influenced by LA supplementation, supported by studies relating ENaC activity to rafts.323

PwCF have an increased glomerular filtration rate which was normalized after fatty acid supplementation.318,327,328 It is well-known that pwCF need high doses of antibiotics329 partly due to an increased non-renal clearance330 and partly due to increased glomerulus filtration rate.331 After LA supplementation the glomerulus clearance normalized.318 In rats with EFAD, glomerulus clearance was increased.332

In a dietary study of tissue incorporation of EFA in rats, the LA levels were 18-fold higher in kidney phospholipids than that of alpha-linolenic acid (ALA, 18:3n-3), both provided in similar amounts.333 Oxylipins from LA were highly concentrated in the kidney,333,334 but not related to the AA concentration or the corresponding AA products, suggesting that the effect was not eicosanoid related. In a study of EFAD rats, labeled LA was highly incorporated in the kidney, especially in PE but not in phosphatidylinositol (PI).335 In another experimental study of mice with EFAD, AA was well preserved in PC, PE and phosphatidyl serine (PS) in the kidney compared to the liver, but not in PI.336 Nothing is known about the effect in CF, but tentatively the transmembrane proteins CFTR and ENaC may be influenced directly or indirectly326 by LA deficiency changing membrane lipid pathophysiology affecting the described disturbances as indicated by the effect of LA supplementation. PGE2 and PGF2α, which are increased in CF, enhance the ENaC channel open probability.337

Airway function

The problem for many years has been the controversial concept of what is the primary origin of the airway problems - is it inflammation per se or the infections causing inflammation (for review see137). Increasing amount of data indicate that the inflammation starts before the infections338,339 supporting an abnormality in the inflammatory homeostasis, beginning already in utero.340 The inflammation might be related to the increase of AA,341,342 which is rate-limiting for the synthesis of eicosanoids, most of which are pro-inflammatory and found in high amounts in the airways, but also in urine indicating a general high production.177,257,258 High AA concentrations are also related to increase of MUC5A, important for the pathological mucus in CF,281 and to low exhaled NO, also in non-pseudomonas infected pwCF.343 The low exhaled NO was inversely correlated to EFAD index.344 Infection will add to a primary inflammation, contributing to the severity of the pulmonary disease in CF. Such interpretation is supported by studies reporting improvement of the lipid abnormality in serum after lung transplantation, not in terms of the disturbed balance, but in the total absolute amount of LA.345 Significant correlations have been reported between pulmonary function and the LA status of pwCF.116,119,243,346 Interestingly also in a chicken model pulmonary pathology was induced by EFAD.347 In Sweden with decades of LA supplementation in the two largest CF centers, the lung function has been higher than in the other Nordic centers despite lower antibiotic use.295,348,349 The defective macrophage function, of importance for the bacterial clearance in the airways, is dependent on several factors and modulators have contradictory results.350 High PGE2 in pwCF inhibited phagocytosis of inhaled diesel exhaust particles.351 ETI had some influence on the phagocytosis in pwCF, but did not influence the inflammatory markers.352 The cell membrane lipid configuration would be interesting to investigate in this context.

Bone mineral density

Osteoporosis and fractures are reported as a common finding in adults with CF,353 but are rare in the Swedish CF population.354 PwCF with normal growth have decreased bone mineralization but normal bone growth was found in a longitudinal study of the Swedish pwCF, who regularly received LA supplementation.355,356 The bone mineral content was differently associated to the fatty acid profile in children and adult pwCF,357,358 which can be referred to different influence of fatty acids during bone modeling in childhood and bone remodeling in adults.359 Animal studies have shown that fatty acids are important for bone growth.212,213,360,361,362 The role of PGE2 in bone modeling is depending on its concentration and there are indications in animal experiments that IGF-1, which is low in CF, is important for mineralization of trabecular bone.363,364 Studies in healthy children indicate that both LA and DHA are important for bone mineral density.365,366 Longitudinal studies are warranted to evaluate associations between bone modeling and lipid metabolism in CF.

Clinical effects of fatty acid supplementation

After 1975, when the pancreatic function in a newborn infant with CF temporarily recovered after Intralipid administration,175 several trials with LA, or high energy diets including LA, have been performed, a few for one year or longer.80,174,346 None showed influence on pancreatic function, but influence on growth, also in supplementation for only some months.180,198 High energy intake alone did not have the same effect.180,182,367,368 Pulmonary function was also influenced by LA status but not by n-3 fatty acid supplementation.116,243,369

In a long-term controlled small study performed before the gene was identified, administration of Intralipid biweekly over 2 of 3 years,174 showed improvements in renal and liver parameters compared to the control pwCF not receiving LA supplementation.293,318 The dose was relatively low, which was illustrated by a very slow improvement in plasma fatty acid status. Another study showed increased LA in several tissues after one year of LA supplementation compared to non-supplemented pwCF.80 Many clinical studies have shown associations between low LA and clinical symptoms.116,119,131,243,291,346,370 Animal studies of LA deficiency have shown similar clinical symptomatology as found in pwCF.237,332,347 It has to be noticed that most studies have given too low substitution or for too short time. In one study giving very high amount of LA (13 g per serving) the effect in some children was remarkable.187 In relation to all available data about low LA, reported for more than 60 years, it is surprising that nutritional guidelines usually not mention the fatty acids. One reason might be that the fatty acids are not analyzed and thereby not considered. Thus, there are no general recommendations for LA supplementation.371,372

It is well known that low LA concentrations sometimes are associated with high AA concentration, while supplementation with LA decreases the AA concentration,138,139,140,141,373 and importantly - without increasing inflammation.139 The general inverse relation in plasma phospholipids between AA and LA is also documented in pwCF.137 Based on results in cell cultures using sense and antisense CF cells, warnings have been expressed to supply LA in CF,374,375 which might explain the reluctance to further explore this simple treatment strategy. It is of interest that the eicosanoid excretion was influenced by LA supplementation, supporting the inverse relation between LA and AA.177 Obviously also in Sweden, where LA has been supplied to most pwCF at the two largest centers for several decades, the good clinical results were thought to depend on the general pulmonary treatment strategy, especially the antibiotic schedules.376,377,378 It is difficult to compare small centers, which of course have small differences in general treatments, but what really stands out when comparing the Nordic centers was the lipid supplementation policy (only applicated in the two biggest centers in Sweden), which was associated with less need of antibiotics and still good lung function.295,348,349 This observation motivates a double-blind randomized study to evaluate if regular LA supplementation should be offered to the pwCF as an adjuvant therapy (ClinicalTrials.gov ID#NCT04531410).

The cause of the low DHA is not clear, but the variation in concentration in different pwCF and models suggests that this might not be a primary disturbance. Some improvement of DHA by LA supplementation has been shown supporting it might be secondary to the lipid dysfunction125 associated with a high phospholipid turn-over and a supply of PC via the alternative pathway from PE, rich in DHA.108 This is further supported by the general lack of clinical improvement by n-3 supplementation studies.147,148,379,380,381,382 One longitudinal study showed positive association between n-3 fatty acids and lung function,383 and one study showed that high ratio between the DHA-derived resolvin D1 and IL-8 levels in sputum was associated with better lung function.384 However, another study with regular intravenous supplementation of omega-3 for 3 months showed negative impact on the included pwCF.385 One n-3 supplementation study showed marked clinical improvement by a combination with γ-linolenic acid, the fatty acid derived from LA in the transformation to AA.75,386 The n-3 fatty acids are important as substrate for SPM.387 Thus, if not possible to balance a high eicosanoid production by decreasing the AA release, the counter action of n-3 providing SPM might theoretically balance the inflammation, which was indicated in cell cultures.388 That was also supported in a community-based study of non-CF adults, where the total n-3 fatty acids were independently associated with lower levels of proinflammatory markers and higher levels of anti-inflammatory markers.389 Interesting observations were reported in studies of mice253 and infants,390 respectively, where DHA supplementation highly amplified 15-LOX increasing LXA4 in plasma compared to controls, and thereby influencing inflammation. It was also possible to improve LA by DHA supplementation in cell culture studies with sense-antisense cells.391 Current evidence is insufficient to routinely recommend supplementation of omega-3 fatty acids to people with CF, although theoretically it may hamper inflammation.

The potentiator Ivacaftor given to pwCF with the G551D mutation decreased AA and also showed a trend to less prostanoid excretion,392 but hitherto studies in pwCF have not shown influence on the classical plasma fatty acid pattern by the new modulators,69,71 despite that several studies have shown a general influence on PC and ceramides.40,41,42,43,44,155,393

Possible mechanisms of the fatty acid abnormalities

The mechanism underlying CFTR and the fatty acid abnormalities is not known and suggestions have previously been discussed.108 CFTR seems to be inhibited by AA like other chloride transporting epithelial channels,394,395 and the mechanism has been suggested to be an electrostatic interaction with amino acids in blocking the entrance in the CFTR molecule.396 This might only be relevant for the classes of mutations with disturbed gating. The multi-complexity of disturbed functions of the more than 2200 variants of CFTR indicates additional mechanisms. The recent information that the new modulators influence the phospholipids and ceramides opens for new aspects and interest in the possible interaction between CFTR and lipid metabolism. Abu-Arish et al.61,62 have suggested that there might be two populations of CFTR related to membrane cholesterol enrichment influencing the micro-domains and raft platforms. These aggregations were regulated by secretagogues like vasoactive intestinal peptide and carbachol, which increased the CFTR aggregation into clusters building ceramide-rich platforms.

It is well known that lipids modulate ion channel activity, either by direct interaction with the channel structure or by modulating the physio-chemical properties of the cellular membrane.50,397 The importance of protein-lipid interaction for normal activity of channels and other membrane bound proteins are well established.398,399,400,401 The fatty acid composition influences enzyme activity, receptor affinity, transport capacity, and permeability,75 as illustrated in the activity of Ca++-ATPas being related to the chain length of fatty acids,76 and the function of aquaporins dependent on binding to phospholipids.77 One factor might be that different mutations of CFTR make the stereo-interaction with the lipids in membranes incomplete thereby disturbing the membrane associated transports or the activity of the channel in the plasma membrane.75,76,77,402,403,404 Support for such mechanism in CF was presented by Eidelman et al.405 showing that the NBF-1 domain of CFTR interacted in membranes with PS rather than PC, but that the Phe508del mutation lost the ability to discriminate between PS and PC. They showed that non-charged analogous to PC could increase the CFTR expression, indicating that phospholipid chaperones might be therapeutic tools. This work links clinical PC abnormalities with the CFTR dysfunction. In this context it is of interest that PS was shown to thermally stabilize CFTR by stimulating the ATP hydrolysis function of purified CFTR. Regulatory lipid interactions may differently regulate ion channel functions in different organelles,406 explaining or contributing to different abnormalities in different tissues (for overview see Figure 1).

It was suggested more than 30 years ago that the LA deficiency was not due to malabsorption but related to an increased release of AA with an increased compensatory transformation of LA, resulting in low LA concentrations.342,407 The AA release from membranes was not inhibited by dexamethasone in cells from pwCF compared to healthy controls, indicating an increased activity of cPLA2, the major AA releasing enzyme, which was confirmed by others in different cell systems.281,408,409,410 A high turn-over demands upregulation of the enzymes involved in the fatty acid transformation, which was documented and suggested as the primary defect.411 The upregulation of the desaturases and elongases was related to increased activity of cAMP-activated protein kinase (AMP/APK),412 which might be secondary to infection/inflammation and thus further increasing the transfer of LA to AA.413

The increased AA release was suggested being the result of an impairment in the regulation of cPLA2 by annexin 1 (lipomodulin) or the necessary phosphorylation for its action on cPLA2.342 (Figure 1). This hypothesis has been supported in reports that annexin 1 is decreased in CF cells and that inhibition of annexin 1 stimulates AA release414 and in cell systems also attenuate glucocorticoid functions.415 In the annexin-1 KO mice macrophage functions are impaired with increased COX-2 and PGE2 release with an exaggerated response to inflammation.416,417,418 Annexin 1 was shown to colocalize with PS for clearance of apoptotic cells,419 illustrating the importance of phospholipids in cell functions. The activity of annexin 1 is linked to S100, low molecular weight proteins of calcium-binding family, which also have been found involved in the cAMP/PKA signaling.420 Borthwick et al.421 showed that the annexin 2-S100A10 complex with CFTR regulated the channel function by AMP/PKA and showed this action was defective in Phe508del cells. In neutrophils, LA and its fatty acid derivatives are ligands to fatty acid binding complex with S100 proteins.422 It is of interest that strains of CF mice with different expression of the S100 proteins had different correlations to inflammatory lung disease and increase of neutrophils.423 In a recent study of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of young pwCF 1–5 years of age, a shift was shown from LA to AA derivatives associated with neutrophil influx and progression of lung damage,72 supporting studies in annexin 1-deficient neutrophils showing a greater extent of leukocyte transmigration resulting in a prolonged and exacerbated inflammatory response.424 However, the interaction between CFTR and annexin or its complex with S100 is not known. Of interest for functional studies might be that the eight annexins have 37–47% homology with CFTR.425

If AA release is primary to LA deficiency in CF, a blockage of the AA release would have therapeutic implication, as reviewed recently.426 If it can be confirmed that LA supplementation in CF would be a way to naturally decrease the availability of AA,138,139,140,141 thereby circumventing the lacking CFTR/annexin/S100 inhibition of PLA2, that would be a tentative way to decrease the inflammation. The good results in Sweden by supplementation of LA for decades before the modulator therapy was available might support such suggestion.295,348,349,378

Activation of AMP/APK may also interfere with ENaC to decrease sodium absorption and reduce inflammation.427,428 An upregulation of ENaC has been documented in many experimental studies, and considered to contribute to the impaired secretion.429 Interestingly, overexpression of one trimer of the ENaC molecule results in CF like clinical disease.5 It has been shown that CFTR influences ENaC activity, but the mechanism is unclear. Some authors have suggested a close localization between the two channels in the membranes,430,431,432 but that was not supported in a study on alveolar cells.433 Whatever, the mechanism, it is clinically clear that LA administration influences sodium excretion both in sweat and kidneys.324 Since both CFTR and ENaC are active in membranes, it might be speculated that lipid membrane configuration interferes with their functions. It has been shown in cell studies that AA, like its product by cytochrome P450 epoxygenase, the 11,12-EET, significantly reduced the ENaC open probability, but that it was significantly enhanced by PGE2 and PGF2α,337 suggesting importance of the AA metabolism for the symptoms. Increased ENaC activity can have different explanations and Na+-K+-ATPas activity was coordinated with the ENaC activity in studies in renal collecting ducts.434 It is therefore of interest that the Na+-K+-ATPas activity in erythrocytes was activated by LA supplementation.435 It has been suggested that an inhibition of ENaC would improve the symptoms in CF and modulator development for ENaC are in progress.436 If the sodium transport can be improved by supplying LA it would be an inexpensive therapeutic additive.

Another factor of interest for the pathophysiology is the similarity between LXRβ KO- mice and clinical CF symptomatology.3,164 LXRβ interferes with CFTR,4,437,438 cholesterol, and fatty acid metabolism.165 LXRs influence immune response and inflammation439,440 and are important regulators of inflammatory gene expressions, and can blunt COX-2 and iNOS genes and various chemokines in response to TNF-α and IL1-β.439,440,441 LXRαβ−/− mice have shown increased susceptibility to infection associated with defective macrophage function,442 which is of interest since LXRs interfere with AA metabolism and eicosanoid secretion in macrophages.443 An important mediator of LXR effects is the modulation of PUFA in PC by influencing lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3, which preferentially synthesizes PC containing AA and LA at the sn-2 position.107 The different impact on or result of defective annexins and LXR on the fatty acid metabolism and CFTR are challenges for understanding the pathophysiology and symptoms in CF.

The influence of fatty acids on gene expression must also be considered.444 An increasing number of reports put attention to overlapping influences of CFTR variants, and different effects of therapy suggesting that the classification of six groups of mutation related dysfunctions probably need to be modified.445,446 This indicates that personalized therapy will be more important than only a broad classification of the CFTR variants. In this context it would be of interest to investigate the fatty acid status of the pwCF related to different effects on/of CFTR variants, since the fatty acid composition differs in cell organelles and plasma membranes which would be an explanation to different levels of dysfunction or blocking.403,447

Membrane lipid therapy has been suggested as possible treatment for many pathological conditions.448 The clinical associations between dysfunction of LA, AA, and DHA and the CF symptomatology related to the membrane proteins CFTR and ENaC, as well as to the nuclear receptor LXRβ, supported by different observational, experimental, and animal studies as outlined in this review, suggest that further studies on the lipid abnormalities are relevant, and may open for new and even cheap concepts for additional treatment.

Conclusion and prospects

The lipid abnormalities in CF are present at birth and develop further, more in organs than in serum, if not compensated by supplementation of LA by high dietary intake and/or intravenous supplementation. As components of membranes, fatty acids influence many metabolic functions and the fatty acid products, like the lipid mediators, are of strong importance for both metabolic and inflammatory characteristics of CF. The transmembrane localization of both CFTR and ENaC explains interaction with lipids. The role of annexin/p11 controlling the AA release might be a key factor in the pathophysiology, explaining high AA and compensatory low LA. Despite the accumulating evidence from both observational and experimental studies regarding the tentative relation between symptoms in CF and lipid abnormalities and the potential clinical benefits of fatty acid supplementation, lipids are not routinely analyzed, and no recommendations are provided in clinical guidelines. Confirming the possible additive or synergistic effects of fatty acid supplementation to CFTR modulating therapy would open for inexpensive and important adjuvant therapy and might even have an influence in those pwCF not eligible for the available modulator therapy.

Author contributions

B.S. designed the original draft, but all authors contributed with literature search and conceptualization of the manuscript. B.S. reviewed and edited the manuscript, which was approved by all authors.

Declaration of interests

J.W. reports personal fees and non-financial support from Biocodex, BGP Products, Chiesi, Hipp, Humana, Mead Johnson Nutrition, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Nestle, Norsa Pharma, Nutricia, Roche, Sequoia Pharmaceuticals, and Vitis Pharma, outside the submitted work, and grants, personal fees and non-financial support from Nutricia Research Foundation Poland, all outside the submitted work.

None of the other authors declare any conflicts of interest. Financial support for discussion meetings was received from European Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition and from the Swedish Cystic Fibrosis Association. No competing interest are reported by the authors.

References

- 1.Rubin B.K. Unmet needs in cystic fibrosis. Expet Opin. Biol. Ther. 2018;18:49–52. doi: 10.1080/14712598.2018.1484101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.West N.E., Flume P.A. Unmet needs in cystic fibrosis: the next steps in improving outcomes. Expet Rev. Respir. Med. 2018;12:585–593. doi: 10.1080/17476348.2018.1483723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gabbi C., Warner M., Gustafsson J.A. Minireview: liver X receptor beta: emerging roles in physiology and diseases. Mol. Endocrinol. 2009;23:129–136. doi: 10.1210/me.2008-0398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sweed N., Kim H.J., Hultenby K., Barros R., Parini P., Sancisi V., Strandvik B., Gabbi C. Liver X receptor β regulates bile volume and the expression of aquaporins and cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator in the gallbladder. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2021;321 doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00024.2021. G243-g251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mall M., Grubb B.R., Harkema J.R., O'Neal W.K., Boucher R.C. Increased airway epithelial Na+ absorption produces cystic fibrosis-like lung disease in mice. Nat. Med. 2004;10:487–493. doi: 10.1038/nm1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bierlaagh M.C., Muilwijk D., Beekman J.M., van der Ent C.K. A new era for people with cystic fibrosis. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2021;180:2731–2739. doi: 10.1007/s00431-021-04168-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saluzzo F., Riberi L., Messore B., Loré N.I., Esposito I., Bignamini E., De Rose V. CFTR Modulator Therapies: Potential Impact on Airway Infections in Cystic Fibrosis. Cells. 2022;11:1243. doi: 10.3390/cells11071243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Egan M.E. Non-Modulator Therapies: Developing a Therapy for Every Cystic Fibrosis Patient. Clin. Chest Med. 2022;43:717–725. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2022.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allen L., Allen L., Carr S.B., Davies G., Downey D., Egan M., Forton J.T., Gray R., Haworth C., Horsley A., et al. Future therapies for cystic fibrosis. Nat. Commun. 2023;14:693. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-36244-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stylemans D., Darquenne C., Schuermans D., Verbanck S., Vanderhelst E. Peripheral lung effect of elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor in adult cystic fibrosis. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2022;21:160–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2021.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Middleton P.G., Mall M.A., Dřevínek P., Lands L.C., McKone E.F., Polineni D., Ramsey B.W., Taylor-Cousar J.L., Tullis E., Vermeulen F., et al. Elexacaftor-Tezacaftor-Ivacaftor for Cystic Fibrosis with a Single Phe508del Allele. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019;381:1809–1819. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1908639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jia S., Taylor-Cousar J.L. Cystic Fibrosis Modulator Therapies. Annu. Rev. Med. 2023;74:413–426. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-042921-021447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foucaud P., Mercier J.C. CFTR pharmacological modulators: A great advance in cystic fibrosis management. Arch. Pediatr. 2023;30:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.arcped.2022.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kapouni N., Moustaki M., Douros K., Loukou I. Efficacy and Safety of Elexacaftor-Tezacaftor-Ivacaftor in the Treatment of Cystic Fibrosis: A Systematic Review. Children. 2023;10:554. doi: 10.3390/children10030554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thakur S., Ankita, Dash S., Verma R., Kaur C., Kumar R., Mazumder A., Singh G. Understanding CFTR Functionality: A Comprehensive Review of Tests and Modulator Therapy in Cystic Fibrosis. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2024;82:15–34. doi: 10.1007/s12013-023-01200-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olivier M., Kavvalou A., Welsner M., Hirtz R., Straßburg S., Sutharsan S., Stehling F., Steindor M. Real-life impact of highly effective CFTR modulator therapy in children with cystic fibrosis. Front. Pharmacol. 2023;14 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2023.1176815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bell S.C., Mall M.A., Gutierrez H., Macek M., Madge S., Davies J.C., Burgel P.R., Tullis E., Castaños C., Castellani C., et al. The future of cystic fibrosis care: a global perspective. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020;8:65–124. doi: 10.1016/s2213-2600(19)30337-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.King J.A., Nichols A.L., Bentley S., Carr S.B., Davies J.C. An Update on CFTR Modulators as New Therapies for Cystic Fibrosis. Paediatr. Drugs. 2022;24:321–333. doi: 10.1007/s40272-022-00509-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Graeber S.Y., Mall M.A. The future of cystic fibrosis treatment: from disease mechanisms to novel therapeutic approaches. Lancet. 2023;402:1185–1198. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(23)01608-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gillan J.L., Davidson D.J., Gray R.D. Targeting cystic fibrosis inflammation in the age of CFTR modulators: focus on macrophages. Eur. Respir. J. 2021;57:2003502. doi: 10.1183/13993003.03502-2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roesch E.A., Nichols D.P., Chmiel J.F. Inflammation in cystic fibrosis: An update. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2018;53 doi: 10.1002/ppul.24129. S30-s50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghigo A., Prono G., Riccardi E., De Rose V. Dysfunctional Inflammation in Cystic Fibrosis Airways: From Mechanisms to Novel Therapeutic Approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22:1952. doi: 10.3390/ijms22041952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McElvaney O.J., Wade P., Murphy M., Reeves E.P., McElvaney N.G. Targeting airway inflammation in cystic fibrosis. Expet Rev. Respir. Med. 2019;13:1041–1055. doi: 10.1080/17476348.2019.1666715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perrem L., Ratjen F. Are we there yet? The ongoing journey of cystic fibrosis care. Lancet. 2023;402:1113–1115. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(23)01727-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keown K., Brown R., Doherty D.F., Houston C., McKelvey M.C., Creane S., Linden D., McAuley D.F., Kidney J.C., Weldon S., et al. Airway Inflammation and Host Responses in the Era of CFTR Modulators. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:6379. doi: 10.3390/ijms21176379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Griese M., Costa S., Linnemann R.W., Mall M.A., McKone E.F., Polineni D., Quon B.S., Ringshausen F.C., Taylor-Cousar J.L., Withers N.J., et al. Safety and Efficacy of Elexacaftor/Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor for 24 Weeks or Longer in People with Cystic Fibrosis and One or More F508del Alleles: Interim Results of an Open-Label Phase 3 Clinical Trial. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2021;203:381–385. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202008-3176LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Graeber S.Y., Vitzthum C., Pallenberg S.T., Naehrlich L., Stahl M., Rohrbach A., Drescher M., Minso R., Ringshausen F.C., Rueckes-Nilges C., et al. Effects of Elexacaftor/Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor Therapy on CFTR Function in Patients with Cystic Fibrosis and One or Two F508del Alleles. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2022;205:540–549. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202110-2249OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mederos-Luis E., González-Pérez R., Poza-Guedes P., Álava-Cruz C., Matheu V., Sánchez-Machín I. Toxic epidermal necrolysis induced by cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator modulators. Contact Dermatitis. 2022;86:224–225. doi: 10.1111/cod.14002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salehi M., Iqbal M., Dube A., AlJoudeh A., Edenborough F. Delayed hepatic necrosis in a cystic fibrosis patient taking Elexacaftor/Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor (Kaftrio) Respir. Med. Case Rep. 2021;34 doi: 10.1016/j.rmcr.2021.101553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tindell W., Su A., Oros S.M., Rayapati A.O., Rakesh G. Trikafta and Psychopathology in Cystic Fibrosis: A Case Report. Psychosomatics. 2020;61:735–738. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2020.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Petersen M.C., Begnel L., Wallendorf M., Litvin M. Effect of elexacaftor-tezacaftor-ivacaftor on body weight and metabolic parameters in adults with cystic fibrosis. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2022;21:265–271. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2021.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Despotes K.A., Ceppe A.S., Donaldson S.H. Alterations in lipids after initiation of highly effective modulators in people with cystic fibrosis. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2023;22:1024–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2023.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heo S., Young D.C., Safirstein J., Bourque B., Antell M.H., Diloreto S., Rotolo S.M. Mental status changes during elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor therapy. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2022;21:339–343. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2021.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spoletini G., Gillgrass L., Pollard K., Shaw N., Williams E., Etherington C., Clifton I.J., Peckham D.G. Dose adjustments of Elexacaftor/Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor in response to mental health side effects in adults with cystic fibrosis. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2022;21:1061–1065. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2022.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baroud E., Chaudhary N., Georgiopoulos A.M. Management of neuropsychiatric symptoms in adults treated with elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2023;58:1920–1930. doi: 10.1002/ppul.26412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arslan M., Chalmers S., Rentfrow K., Olson J.M., Dean V., Wylam M.E., Demirel N. Suicide attempts in adolescents with cystic fibrosis on Elexacaftor/Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor therapy. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2023;22:427–430. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2023.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bathgate C.J., Muther E., Georgiopoulos A.M., Smith B., Tillman L., Graziano S., Verkleij M., Lomas P., Quittner A. Positive and negative impacts of elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor: Healthcare providers' observations across US centers. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2023;58:2469–2477. doi: 10.1002/ppul.26527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Southern K.W., Addy C., Bell S.C., Bevan A., Borawska U., Brown C., Burgel P.R., Button B., Castellani C., Chansard A., et al. Standards for the care of people with cystic fibrosis; establishing and maintaining health. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2024;23:12–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2023.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O'Connor M.G., Seegmiller A. The effects of ivacaftor on CF fatty acid metabolism: An analysis from the GOAL study. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2017;16:132–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2016.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zardini Buzatto A., Abdel Jabar M., Nizami I., Dasouki M., Li L., Abdel Rahman A.M. Lipidome Alterations Induced by Cystic Fibrosis, CFTR Mutation, and Lung Function. J. Proteome Res. 2021;20:549–564. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.0c00556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Despotes K.A., Donaldson S.H. Current state of CFTR modulators for treatment of Cystic Fibrosis. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2022;65 doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2022.102239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Veltman M., De Sanctis J.B., Stolarczyk M., Klymiuk N., Bähr A., Brouwer R.W., Oole E., Shah J., Ozdian T., Liao J., et al. CFTR Correctors and Antioxidants Partially Normalize Lipid Imbalance but not Abnormal Basal Inflammatory Cytokine Profile in CF Bronchial Epithelial Cells. Front. Physiol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2021.619442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liessi N., Pedemonte N., Armirotti A., Braccia C. Proteomics and Metabolomics for Cystic Fibrosis Research. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:5439. doi: 10.3390/ijms21155439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abu-Arish A., Pandžić E., Luo Y., Sato Y., Turner M.J., Wiseman P.W., Hanrahan J.W. Lipid-driven CFTR clustering is impaired in cystic fibrosis and restored by corrector drugs. J. Cell Sci. 2022;135:jcs259002. doi: 10.1242/jcs.259002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hedger G., Sansom M.S.P. Lipid interaction sites on channels, transporters and receptors: Recent insights from molecular dynamics simulations. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2016;1858:2390–2400. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2016.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hulbert A.J., Turner N., Storlien L.H., Else P.L. Dietary fats and membrane function: implications for metabolism and disease. Biol. Rev. Camb. Phil. Soc. 2005;80:155–169. doi: 10.1017/s1464793104006578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harayama T., Shimizu T. Roles of polyunsaturated fatty acids, from mediators to membranes. J. Lipid Res. 2020;61:1150–1160. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R120000800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Andersen O.S., Koeppe R.E., 2nd Bilayer thickness and membrane protein function: an energetic perspective. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2007;36:107–130. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.36.040306.132643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Phillips R., Ursell T., Wiggins P., Sens P. Emerging roles for lipids in shaping membrane-protein function. Nature. 2009;459:379–385. doi: 10.1038/nature08147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]