Abstract

Background: Access to high-cost cancer drugs is an unsolved problem globally. The dedicated drugs fund is attractive and feasible. This study reviewed currently implemented dedicated drugs fund worldwide to inform policy implications for Thailand.

Methods: A scoping review was conducted to identify countries currently implementing dedicated funds for cancer drugs. We searched electronic databases, PubMed and Embase, from 2010 to May 2021, Google and Google Scholar in August 2021, and government websites up to April 2022. The structure, management, cost containment strategies, and impact of dedicated funds were summarized and compared across the identified countries and Thailand.

Results: Out of 218 nations, Hong Kong, England, and Italy have established dedicated cancer drugs fund, primarily funded by their governments. Funds in England and Italy operate within annual budget limits. Hong Kong relies on an endowment fund. In England and Italy, pharmaceutical companies contribute proportionally to cover overspending as per risk-sharing agreements, while cost-sharing is not required. Hong Kong implements cost-sharing based on a patient's family income. England and Italy employ a parallel pathway, utilizing the same drug selection committee to determine whether innovative drugs belong in the regular pharmaceutical benefits package or the dedicated drugs fund. Hong Kong follows a sequential pathway, allowing drugs to be considered for the dedicated funds after a negative decision. These countries use the fund for 5-11 years, making administrative adjustments to ensure sustainability.

Conclusion: The dedicated drugs fund is an effective strategy to improve access to non-reimbursable high-cost drugs in Thailand. Robust evaluation of the fund itself and funded drugs are recommended for policymakers’ better decision-making. Learning from other countries can offer promising solutions. Health insurers need to balance providing cancer treatments with overall system preparedness.

Keywords: Dedicated Fund, High-Cost Drug, Cancer Drug, Global Review, Thailand

Background

Cancer is a group of diseases with uncontrolled cell growth. Cancer can occur in many organs. GLOBOCAN revealed 19.3 million new cancer cases from 36 cancer types worldwide in 2020.1 According to the 2019 World Health Organization (WHO) report, cancer was ranked second among the leading causes of death worldwide.2 In Thailand, cancer is the leading cause of mortality, with a reported rate of 112.8-125.0 per 100 000 people from 2015 to 2019.3 Global expenditure on cancer treatment is tremendous, and drug cost consumes the largest proportion of money in terms of medical treatment. Between 1995 and 2018, health expenditures for cancer treatments in European Union countries nearly doubled from US$ 61 billion (52 billion Euro) to US$ 121 billion (103 billion Euro). During the same period, there was an increase in newly diagnosed cancer cases by approximately 50% and the use of high-cost drugs. Therefore, it was expected that the costs would continue to increase.4

To improve access to cancer drugs, various strategies have been utilized. Basic pharmaceutical reimbursement schemes with pricing policies provide the basic tools for most health insurance systems. Alternative funding strategies specific to cancer drugs, such as managed entry agreements (MEAs), dedicated funds for cancer drugs, orphan drug reimbursement policy, adjusted cost-effectiveness threshold, and the use of compulsory licensing, were complementarily utilized on top of the preferred drug list strategy. Financial assistance is another strategy used by either government or non-government organizations to support patients. Examples of financial assistance strategies include providing additional health insurance policies for the poor, reducing or exempting patient cost-sharing, utilizing patient assistance programs (PAPs), and setting up assistance foundations. Combinations of these strategies have been utilized and implemented to fit each country’s circumstances.5

Thailand’s health insurance system is highly recognized by the international community as a strong and advanced system comparable to the health insurance systems of other high-income countries. In Thailand, health insurance schemes cover all Thai citizens; Social Security Scheme (SSS) for employees in the private sector; Civil ServantMedical Benefit Scheme (CSMBS) for government officers and their dependents; and universal health coverage (UHC) schemes for the rest.

In general, access to medical services for Thais is considered good. All Thais under insurance have access to drugs listed in the National List of Essential Medicines (NLEM) of Thailand. However, access to cancer drugs has been reported to be quite limited, and there is a huge gap between local cancer protocol and international cancer treatment guidelines.6 Saerekul et al in 2018 and Patikorn et al in 2019 unanimously found that more than 85% of approved cancer drugs worldwide were market-authorized by the Thai Food and Drug Administration; however, only half of them were reimbursable.6,7 Patikorn et al also found that access to cancer drugs differed across the three Thai public health insurance schemes. SSS provides fewer types of cancer coverage when compared to UHC and CSMBS. CSMBS has broader coverage as they have an additional Oncology prior authorization (OCPA) program that allows for better access to cancer drug items and indications not listed in the NLEM. OCPA was established in 2005 with six cancer drugs. After more than 10 years of hiatus, OCPA has resumed its activity and actively included more cancer drugs in its program since 2018. Furthermore, there is a concern regarding the local and international cancer treatment guidelines. An example of treatment recommendations for advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer with anaplastic lymphoma kinase rearrangement positive is the use of anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibitor drugs, as recommended by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guideline 2021.8 However, the local cancer reimbursement protocol 2015 in Thailand recommends platinum (cisplatin or carboplatin) with paclitaxel, vinorelbine, docetaxel, gemcitabine or pemetrexed instead.9

Thailand has a health technology assessment (HTA) body supporting drug reimbursement decisions. Thai NLEM is updated yearly and implemented across the three public health insurance schemes. Reimbursement of cancer drugs must follow the cancer protocols.6 Reimbursement decisions have been primarily limited by the affordability of the health system, such as the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) threshold in Thailand. The results of three cost-effectiveness analyses of high-cost innovative cancer drugs conducted by the Health Intervention and Technology Assessment Program (HITAP) in 2017 showed that the ICER per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) gained ranged from US$ 20 099 to US$ 353 842 (682 155-12 009 328 Thai Baht) which far exceeded Thailand’s cost-effectiveness threshold of US$ 4714 (160 000 Thai Baht) per QALY gained by 4-75 times.10-12 Therefore, we have still encountered the access problem of high-cost cancer drugs due to the very high ICER/QALYs gained. Moreover, consideration of generic or biosimilar availability is an issue. To illustrate, the NLEM includes five monoclonal antibodies (rituximab, trastuzumab, basiliximab, tocilizumab, and bevacizumab) and four targeted therapies (erlotinib, imatinib, nilotinib, and dasatinib). More importantly, some of these drugs were listed in the NLEM at the time when generic products were available.6 This implies that patients may experience delays in accessing care. In addition, the policy of choosing only one drug from the same pharmacological drug class was utilized.13 Thus, many cancer drugs in Thailand are not reimbursable, and these drugs compose not only non-innovative but also the innovative drugs.

Besides the preferred drug list, pricing policy, prior authorization, economic evaluation, and budget impact strategies implemented in Thailand’s public health insurance systems, the PAP is another financing strategy.6 Several pharmaceutical companies sponsor PAPs, which cover a range of cancer drugs to alleviate self-paying patients financially.14 There are many types of PAPs; however, they could be broadly categorized into two groups.6,14 First is the fixed scheme in which PAP offers a fixed assistance pattern of “Buy X gets Y boxes free” for every patient under the same indication. The second is PAP which considers patients’ income. Income is a major criterion in deciding whether the patient is qualified for PAP or not and reflects the level of financial support the patient will receive. The decision to join PAP depends solely on the patient. Although PAP could alleviate the financial burden of the patients, it helps only those who still have the ability to pay and leaves out the poor who cannot afford it.6,14

Thailand has utilized many strategies to enhance access to cancer drugs. However, dedicated funds for cancer drugs have not been explicitly implemented. Dedicated funds are another financial subsidization method that some countries use to aid access to high-cost cancer drugs. National budgets are allocated to subsidize cancer drugs awaiting reimbursement decisions.15,16 Among other strategies not yet implemented in Thailand, the dedicated fund is one of the interesting strategies that could benefit our current healthcare system. As countries which have implemented dedicated funds have different criteria and processes, it is interesting to explore the details of those dedicated funds. Therefore, this study aims to review existing international dedicated funds for cancer drugs to inform the development of policy implications suitable for Thailand.

Methods

Data Source

We conducted a scoping review. Because of the nature of the studies on policies and routine operations, information related to cancer drug funds is not solely available in peer-reviewed journals. A literature review of published literature alone may miss out on important information. Therefore, we searched for both published literature and grey literature to identify countries that currently implement dedicated funds for cancer drugs. We reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist (Supplementary file 1 – Table S1).17

For the purpose of this study, dedicated funds for cancer drugs were defined as special reimbursement programs with the allocated budget to provide patients access to cancer drugs outside the regular reimbursement system (ie, reimbursement list) awaiting to be transitioned to the standard reimbursement drugs list. A case-by-case reimbursement of cancer drugs was not included under this definition. In addition, dedicated funds that ceased their operation were not included.

Electronic databases, including PubMed and Embase, were searched to identify countries implementing dedicated funds for cancer drugs from any relevant peer-reviewed articles published from 2010 to May 12, 2021. This is to capture the latest ten years of evidence using a combination of synonyms of “Cancer,” “Drug,” and “Fund.” Search strategies are shown in Supplementary file 2 – Table S2. Titles and abstracts of the identified articles from electronic databases were then independently screened for relevancy by two reviewers (PL and CP) after excluding duplicates. Relevant articles were then sought to retrieve their full-text articles and independently selected against the eligibility criteria by two reviewers (PL and CP). The third reviewer (ON) made a final decision when a discrepancy was identified. Eligible articles should be full-text articles, including original research, reviews, and editorials published in peer-reviewed journals which provide information regarding the dedicated funds for cancer drugs. Any discrepancies in this review were resolved by discussion among all authors.

Grey literature, including websites and reports, were searched via Google and Google Scholar in August 2021 using the keywords “Cancer” AND “Drug” AND “Fund” AND “Name of country” for additional information regarding the dedicated funds for cancer drugs in 218 countries throughout the world. Only the first 50 articles identified from Google and Google Scholar searches were screened. We then further searched the government websites to gather information on dedicated funds for cancer drugs. Searching the government websites was performed up to April 30, 2022.

Selected evidence was independently extracted by two reviewers (PL and CP). The third reviewer (PA) made a final decision when a discrepancy was identified. The following information was extracted: country, name of dedicated funds for cancer drugs, year of establishment, responsible organization, organization structure, mission and objective of dedicated funds, financing mechanism, selection criteria and coverage, operational process, cancer drugs list, and impact of dedicated funds for cancer drugs on patient access.

Data Analysis

Extracted data were analyzed to compare the structure of dedicated funds for cancer drugs, management, and cost containment strategies, and the impact of the dedicated fund on patient access across countries. Cancer drugs under the dedicated funds were extracted and compared across the identified countries and Thailand to understand the current situation of access to cancer drugs in Thailand. Findings and extracted data were subsequently used to formulate policy recommendations for dedicated funds for cancer drugs in the context of the health system in Thailand.

To analyze the current situation of access to cancer drugs in Thailand, the cancer drug items of each country were compared to their reimbursable classification. Identified cancer drugs were divided into 15 groups according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system.18 The reimbursable classification of cancer drugs was divided into five categories as follows: (1) Reimbursable under regular benefits package: drug could be reimbursed through the national health insurance scheme in the country; (2) Reimbursable under special programs: drug could be reimbursed through the special programs outside the regular benefits package including OCPA in Thailand; (3) Reimbursable under the dedicated funds: drug could be reimbursed through the dedicated funds in the identified countries; (4) Not Reimbursable: drug could be neither reimbursed through the national health insurance scheme nor the special program in the country; and (5) Not registered: data were not registered, or the drug had not been approved for marketing authorization in the country. For Thailand, we reported access to cancer drugs separately as UHC/SSS and CSMBS due to the differences in access to cancer drugs across these three health insurance schemes.

Results

Identified Countries With Dedicated Funds for Cancer Drugs

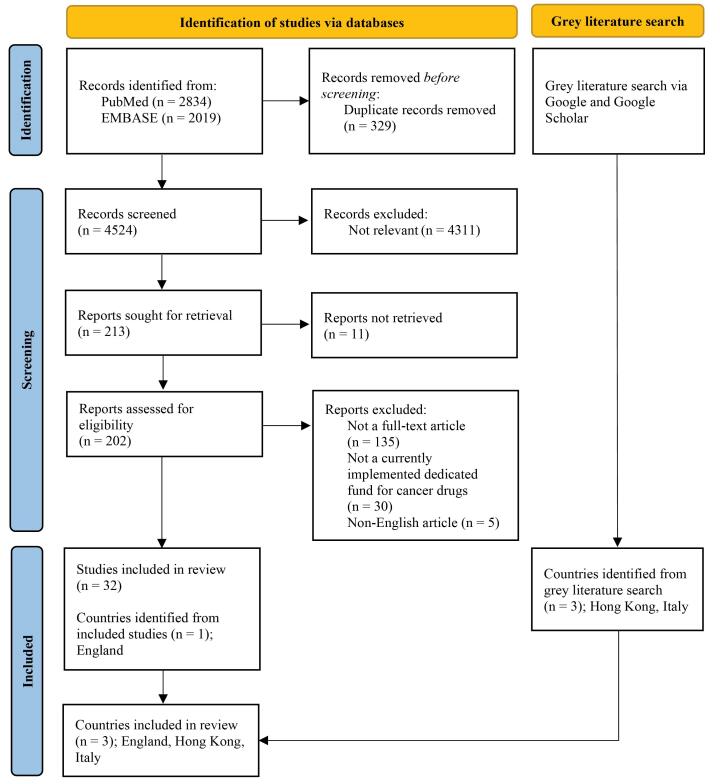

A total of 4853 articles were identified from electronic databases, of which 33 were included (Figure 1).16,19-49 From these included articles, dedicated funds for cancer drugs were found to be currently implemented in England. A supplemental search for dedicated funds for cancer drugs in 218 countries via Google and Google Scholar found three countries: Hong Kong, England, and Italy. We found no countries that had previously implemented dedicated funds programs for cancer drugs and ceased their operations.

Figure 1.

Selection Flow of Countries That Currently Implement Dedicated Funds for Cancer Drugs.

Country demographics and health insurance systems of these three countries and Thailand were summarized in Table 1. Details of dedicated funds for cancer drugs in England, Hong Kong, and Italy were summarized in Table 2. We compared key characteristics of dedicated funds for cancer drugs in Hong Kong, England, and Italy.37,43,50-61 Dedicated funds for cancer drugs in England and Italy are similar in providing early access to innovative cancer drugs while real-world data are being collected to inform future transitioning to the normal funding mechanism. On the other hand, dedicated funds for cancer drugs in Hong Kong have been established to provide financial assistance to patients who need cancer drugs and are transitioning to reimbursement. England’s cancer drugs fund (CDF) allows access to only cancer drugs. Hong Kong’s Samaritan Fund (SF) and community care fund (CCF) and Italy’s Fund for Innovative Oncological and Non-oncological Medicines provide access to both cancer and non-cancer drugs.

Table 1. Country Demographics and Health Insurance System as of 2020 .

| Thailand | Hong Kong | United Kingdom | Italy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population, million | 69.80 | 7.50 | 67.20 | 59.60 |

| GDP, million USD | 501 644 | 346 585 | 2 707 743 | 1 886 445 |

| GDP per capita, USD | 7187 | 46 324 | 40 285 | 31 676 |

| Total healthcare expenditure per capita, USD | 296 | 3250 | 5268 | 3819 |

| Healthcare expenditure, % of GDP | 3.8%a | 6.1% | 9.8% | 8.9% |

| Pharmaceutical expenditure, % of total healthcare spending | 55.5%b | 10.6% | 11.5%a | 18.0%a |

| Public healthcare spending per capita, USD (% of total healthcare expenditure) | 216 (73.0%) | 1740 (53.5%) | 4306 (81.7%) | 2914 (76.3%) |

| National health insurance system | NHSO | Public Healthcare System | NHS | SSN |

| Healthcare coverage scheme | - UHC - SSS - CSMBS |

- UHC - CSSA |

UHC | UHC |

| Health benefits packages | - Healthcare services: outpatient, inpatient, health promotion and disease prevention, high-cost healthcare services - HIV infection care - Chronic kidney disease care - Prevention of chronic diseases in community-based care - Long-term care for dependent patients - Primary care cluster |

- Pharmaceuticals - Inpatient care - Preventive medicine - Outpatient specialist care - Maternity care - Home care - Primary care - Hospice care |

- Pharmaceuticals - Inpatient and outpatient hospital care - Preventive services - Maternity care - Physician services - Clinically necessary dental care - Some eyes care - Mental healthcare - Palliative care - Some long-term care - Rehabilitation - Home visits by community-based nurses - Wheelchairs, hearing aids, and other assistive devices |

- Pharmaceuticals - Inpatient care - Preventive medicine - Outpatient specialist care - Maternity care - Home care - Primary care - Hospice care |

| Classifications of pharmaceutical benefits | - List A: Standard medicines for preventing and treating common health problems - List B: Alternative medicines to List A medicines - List C: Medicines prescribed in specialty diseases - List D: Medicines with many indications that are likely to be misused - List E1: Medicines for special programs proposed and responsible by government organizations - List E2: Very high-cost medicines for specific groups of patients |

- General drug - Special drug - Self-financed items drug with Safety Net - Self-financed items drug without Safety Net |

- Prescription-only medicine - Pharmacy - General sales list - Black-listed - Selected list |

- Class A: lifesaving drugs and treatments for chronic conditions - Class H: drugs delivered only in a hospital setting - Class C: non-reimbursable drugs - Class C (non negotiated): drugs identified as innovative status covered by Fund for innovative oncological and non-oncological medicines |

| Cost sharing of pharmaceutical benefits | None | - General drugs & special drugs: full coverage by public healthcare system - Self-financed drugs with safety net cost sharing by patients <20% depending on household income - Self-financed drugs without safety net: 100% out of pocket |

Copayment of US$ 12.50 per outpatient prescription - People who are exempt from prescription drug copayments include: - Children aged 15 and under - Full-time students aged 16 to 18 - People aged 60 or older - People with low incomes - Pregnant women and women who have given birth in the past 12 months - People with cancer and certain other long-term conditions or disabilities |

Reimbursable - Tier 1 (Class A): prescription fee for several regions - Tier 3 (Class H): no cost sharing Non-reimbursable - Tier 2 (Class C): 100% out of pocket - Class C (non negotiated): no cost sharing |

| Reimbursement decision making system | Centralized decision making | Centralized decision making | Decentralized decision making across England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland | Decentralized decision making |

| HTA body | HITAP | DAC | NICE | AIFA |

| References | 62-64 | 50,62,65,66 | 62,65,67,68 | 62,65,69,70 |

Abbreviations: AIFA, Agenzia Italiana del farmaco (Italian Medicines Agency); CSMBS, Civil Servant Medical Benefit Scheme; CSSA, Comprehensive Social Security Assistance; DAC, Drug Advisory Committee; GDP, gross domestic product; HITAP, Health Intervention and Technology Assessment Program; NHS, National Health Service; NHSO, National Health Security Office; SSN, Servizio sanitario nazionale (Italian National Health Service); SSS, Social Security Scheme; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; UHC, universal health coverage; USD, United States dollar; HTA, Health technology assessment.

Costs are presented in 2020 USD to ease comparison.

a Data as of 2019.

b Data as of 2014.

Table 2. Characteristics of Dedicated Funds for Cancer Drugs in Hong Kong, England, and Italy .

| Hong Kong | England | Italy | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name of a dedicated fund for cancer drugs | SF | CCF Medical Assistance Program | CDF England | Fund for Innovative Oncological and Non-oncological medicines |

| Establishment year | 1950 | 2011 | 2010 (reformed in 2016) | 2017 |

| Objectives | Financial assistance for self-financed drugs and medical devices when patients have a clinical need with access difficulty | Financial assistance for cancer drugs, uncommon disorders and medical devices not covered by the SF before transitioning to SF | Early access to cancer drugs before transitioning to the normal funding mechanism | - Early access to innovative drugs before transitioning to normal funding mechanism - Ensure equity of access to innovative drugs across regions |

| Administrative organization | Samaritan fund management committee | CCF administrative committee | NHS England | SSN |

| Responsible sector | Government and non-government | Government | Government | Government |

| Source of funding | - Government grants - Social Welfare Department - Donations |

- Government - Donations |

NHS England | Central government |

| Annual budget allocated, million USD (% of pharmaceutical expenditure) | 2012: 1300 for 2012 to 2022 (NA) | - 2011-2015: 256 (NA) - 2016: 436 (1.1%) |

1136 which could be crossed paid between oncology and non-oncology drugs (2.4%) - 568 for oncological drugs (1.2%) - 568 for non-oncological drugs (1.2%) |

|

| An annual budget used, million USD | - 2011: 27 - 2012: 31 - 2013: 38 - 2014: 43 - 2015: 47 - 2016: 50 - 2017: 55 - 2018: 54 - 2019: 68 - 2020: 88 - 2021: 110 |

2017: 22 2018: 36 2019: 40 |

- 2013: 359 - 2014: 436 - 2015/2016: 598 - 2017/2018: 259 - 2018/2019: 308 - 2019/2020: 407 - 2020/2021: 431 |

- 2017: 764 - 2018: 1546 - 2019: 1965 - 2020: 2279 |

| Financial administrative organization | Samaritan fund committee | CCF medical assistance program task force | Joint NHS England/NICE/CDF Investment Group | SSN |

| HTA organization | Drug advisory committee | Drug advisory committee | NICE England | AIFA |

| Drug indications covered | Cancer and non-cancer | Cancer and non-cancer | Only cancer | Cancer and non-cancer |

| Coverage scheme | Self-financed items drug with the safety net | Self-financed items drug with the safety net | Conditional reimbursement with further evidence collected to address clinical uncertainties | Conditional reimbursement with further evidence collected to address clinical uncertainties |

| Length of coverage | Not specified (Note: for a patient who is qualified for the drug in SF/CCF, the reimbursement lasts for 18 months after which the patient’s household income will be re-evaluated) |

Not specified (Note: for a patient who is qualified for the drug in SF/CCF, the reimbursement lasts for 18 months after which the patient’s household income will be re-evaluated) |

Normally up to 2 years | - Fully innovative: up to 36 months (same coverage across regions) - Conditionally innovative: up to 18 months (coverage may vary across regions) |

| Cost sharing | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Patient qualification | Hong Kong Citizens with conditions and indications approved by SF and agree to copay | Hong Kong Citizens with conditions and indications approved by CCF and agree to copay | NHS England eligible patients with conditions and indications approved by the CDF | SSN eligible patients with conditions and indications approved by the AIFA |

| Monitoring and evaluation | Post-approval monitoring and audit | Post-approval monitoring and audit | CDF registry to monitor and evaluate patients’ outcomes | Registry to monitor and evaluate patients’ outcomes |

| Maximum number of covered patients | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified |

| Financial control mechanism | Tender | Tender | Financial agreement by NHS England with pharmaceutical companies with input from NICE’s cost-effectiveness analyses | Financial agreement by SSN with pharmaceutical companies with input from AIFA’s cost-effectiveness analyses - MEAs - Confidential discounts |

| Financial control mechanism in the event of budget overspending | The government secured a budget allocation | The government secured a budget allocation | Proportional rebate to all pharmaceutical companies receiving any funding | Rebate to all pharmaceutical companies receiving any funding |

| References | 50,51 | 52,53 | 37,43,54-58 | 59-61 |

Abbreviations: AIF, Agenzia Italiana del farmaco (Italian Medicines Agency); CCF, community care fund; CDF, cancer drugs fund; NA, not applicable; NHS, national health service; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; SF, Samaritan fund; SSN, Servizio sanitario nazionale (Italian National Health Service); USD, United States dollar; HTA, Health technology assessment; MEAs, managed entry agreements.

Costs are presented in 2020 USD to comparison.

The process of enlisting cancer drugs to the dedicated funds in England and Italy is done as part of the normal reimbursement pathway. Responsible authorities make the decision to include cancer drugs either under the standard drug list or dedicated funds for cancer drugs. Cancer drugs considered for listing in Hong Kong’s SF/CCF were once rejected for inclusion in the standard drug list.

The length of coverage of cancer drugs under the dedicated funds ranges from up to 24 months in England to 36 months in Italy, after which the covered cancer drugs will be re-evaluated to make a final decision to either be reimbursable drugs under the standard drugs list or non-reimbursable drugs. Cancer drugs under dedicated funds in England and Italy will be provided under patient registry programs to monitor patient outcomes and collect real-world data. Patient outcomes are not collected in Hong Kong’s SF/CCF. Cancer drugs under the dedicated funds are provided without cost sharing in England and Italy. Hong Kong SF/CCF requires patients to co-pay depending on their household income.

Dedicated funds for cancer drugs in all countries are funded with the annual budget allocated mainly from government sources. The expenditures of dedicated funds for cancer drugs as a percentage of pharmaceutical expenditures were found to range from 1% in England to 5% in Hong Kong. In Hong Kong, spending of the dedicated funds for cancer drugs was well controlled, with spending within the allocated budget. Spending of the dedicated funds for cancer drugs in England and Italy were exceeding the designated budget. However, the overspending did not cost extra budget to the government. England’s and Italy’s dedicated funds for cancer drugs have a financial control mechanism to prevent budget overspending, such as a proportional rebate to all pharmaceutical companies receiving any funding from the dedicated funds in the event of an overspend in England and Italy.

Hong Kong – Samaritan Fund and Community Care Fund Medical Assistance Programs

SF, established in 1950 by the Legislative Council, is a charitable fund to provide financial assistance to patients who agree to co-pay of 0%-20% self-financed products with the safety net either partially or fully, depending on their household income.71 For a patient qualified for the drug in SF/CCF, the reimbursement lasts for 18 months, after which the patient’s household income will be re-evaluated.50

The CCF Medical Assistance Program, launched in 2011, is a safety net mechanism providing additional funding to support products that the SF does not cover. Similar to SF, a co-pay is also applied. Both funds cover costly cancer drugs, non-cancer drugs, and non-drug items. The Hospital Authority agency, under the Food and Health Bureau’s supervision, is responsible for managing the SF and CCF funds.72 They hold regular quarterly meetings to review and update the hospital formulary. Costly products are reviewed every six months for listing into SF and CCF. However, there is no information on how long drugs are covered under the SF and CCF. As of January 2021, 51 and 37 drug items were included in SF and CCF listing, respectively.73,74

In June 2012, The Finance Committee of the Legislative Council approved a commitment fund of US$ 1.3 billion for 10 years of SF operation. For CCF operation, the government has provided the majority of funds, with approximately 5% of the contribution from the private sector since 2011.75 As of August 2021, the CCF’s balance reached US$ 1600 million.72 Drug expenditure for SF and CCF medical assistance programs was estimated to be around US$ 273 million in 2021 and US$ 403 million in 2022.50

England – Cancer Drugs Fund

In 2010, England initiated the CDF as a mechanism to provide faster access to expensive cancer drugs that have not been reviewed, approved, or received a negative recommendation by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE).16 The annual budget allocation was originally US$ 256 million.76 However, the CDF significantly overspent beyond the allocated budget. The annual spending increased from US$ 359 million in 2013 to US$ 436 million in 2014 and US$ 598 million in 2015/2016.55 Since July 29, 2016, the system has been reformed to prevent the CDF from overspending. The critical aspect of the CDF re-organization was that the CDF utilized the NICE process for reviewing new cancer drugs. The new CDF is now a managed access scheme with clear entry and exit criteria.76

Previously unreviewed or unapproved cancer drugs by NICE would be enrolled in the CDF. The CDF panel, including clinical professionals, public health representatives, and patient representatives, is responsible for appraising drugs regarding access to the CDF list. New drugs are included in the list after the Chemotherapy Clinical Reference Group has reviewed clinical evidence.54 Clinical data are collected on the benefit of the treatments for future reconsideration after two years of coverage.56 Since 2016, all new systemic cancer drug indications expected to receive marketing approval are appraised by NICE for reimbursement. NICE is allowed to make one of three recommendations: (1) recommended for routine commissioning, (2) not recommended for routine commissioning, and (3) recommended for use within the CDF.76

A cancer drug recommended by NICE for use within the new CDF will be funded through the CDF which acts as a new managed access fund for resolving uncertainty. Pharmaceutical companies and the National Health Service (NHS) England will need to agree with the managed access agreement consisting of two key components: a data collection arrangement and a CDF commercial agreement.76

The data collection arrangement includes the data needed to be collected to resolve significant clinical uncertainties jointly set on a case-by-case basis by NHS England, NICE, Public Health England, and the pharmaceutical company, with input from patients and clinicians.76 The time frame for a data collection period is determined on a case-by-case basis, depending on the level of uncertainties. The time frame is designed to be as short as possible but usually would be up to two years.77 However, the accurate duration of drugs would be considered on a case-by-case basis.25

The CDF commercial agreement determines how much NHS England will pay during the managed access period with a confidential agreement between NHS England and the pharmaceutical company. The extent to which the drug costs are covered by NHS is determined on a case-by-case basis with input from NICE based on the results of the cost-effectiveness estimates. After the managed access period, drugs covered under CDF will be reappraised in which the decision could be (1) recommended for routine commissioning, (2) not recommended for routine commissioning.76

Italy – Fund for Innovative Oncological and Non-oncological Medicines

In 2017, the government launched the “Fund for Innovative Oncological and Non-oncological medicines” to solve the problem of access to innovative medicine. This fund aims (1) to facilitate early access to innovative oncology and non-oncology drugs and (2) to ensure equal access to cancer drugs for all Italians as each region administers its benefits package.60

Agenzia Italiana del farmaco (AIFA) is responsible for designating whether the new active substances are deemed innovative, conditionally innovative, or not innovative. AIFA makes the decision based on three main criteria: (1) Unmet therapeutic need: High, important, moderate, scarce, and absent; (2) Added value: High, important, moderate, scarce, and absent; and (3) Quality of evidence using Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation GRADE method: High, moderate, low, and very low.60

The Italian government allocates US$ 1136 million annually to the Fund for innovative oncological and non-oncological medicines (US$ 568 million each for cancer and non-cancer drugs). Drugs with innovative status will be subsidized for 36 months under this innovative funding, and this will be equally applied across all regions. On the other hand, reimbursement of drugs with “conditional innovative” status will be subjected to each regional administration. Drugs with “not innovative” status will not get reimbursed under the universal health insurance system named “Servizio Sanitario Nazionale” (SSN). SSN did not require any cost-sharing for medicines.60,78

After reaching the innovative status, AIFA and the pharmaceutical company need to set the reimbursement price. It was reported by Prada et al that the most common price-setting strategies were hidden discounts followed by financial-based and performance-based MEAs.79

Patients receiving drugs under the innovative drug fund are subjected to registration for outcome monitoring. Information from Statista revealed expenditure on innovative drugs since the special fund embarkment. It was found that the expenses were US$ 764 million in 2017 and continuously increased to US$ 1546, US$ 1965, and US$ 2279 million in 2018-2020, respectively.80 It is worth noting that the expenditure for innovative drugs exceeded the 1 billion Euro budget the year after the special funding was launched. The government primarily allocated a budget of US$ 1136 million for innovative drugs, while the pharmaceutical companies were responsible for rebates exceeding expenditures.

Comparison of Dedicated Funds for Cancer Drugs Across Identified Countries

We compared key characteristics of dedicated funds for cancer drugs in Hong Kong, England, and Italy.37,43,50-61 Dedicated funds for cancer drugs in England and Italy are similar in providing early access to innovative cancer drugs while real-world data are being collected to inform future transitioning to the normal funding mechanism. Dedicated funds for cancer drugs in Hong Kong, on the other hand, are established to provide financial assistance to patients who need cancer drugs. England’s CDF provides access to only cancer drugs. Hong Kong’s SF/CCF and Italy’s Fund for Innovative Oncological and Non-oncological Medicines provide access to both cancer and non-cancer drugs.

The process of enlisting cancer drugs to the dedicated funds in England and Italy is done as part of the normal reimbursement pathway. Responsible authorities make the decision to include cancer drugs either under the standard drug list or dedicated funds for cancer drugs. Cancer drugs considered for listing in Hong Kong’s SF/CCF are once rejected for inclusion in the standard drug list.

The length of coverage of cancer drugs under the dedicated funds ranges from up to 24 months in England to 36 months in Italy, after which the covered cancer drugs will be re-evaluated to make a final decision to either be reimbursable drugs under the standard drugs list or non-reimbursable drugs. Cancer drugs under dedicated funds in England and Italy will be provided under patient registry programs to monitor patient outcomes and collect real-world data. Patient outcomes are not collected in Hong Kong’s SF/CCF. Cancer drugs under the dedicated funds are provided without cost sharing in England and Italy. Hong Kong SF/CCF requires patients to pay cost-sharing depending on their household income.

Dedicated funds for cancer drugs in all countries are funded with the annual budget allocated mainly from government sources. The expenditures of dedicated funds for cancer drugs as a percentage of pharmaceutical expenditures range from 1% in England to 5% in Hong Kong. In Hong Kong, the spending of the dedicated funds for cancer drugs is well controlled, with spending within the allocated budget. Spending of the dedicated funds for cancer drugs in England and Italy is exceeding the designated budget. However, the overspending does not cost extra budget to the government. England’s and Italy’s dedicated funds for cancer drugs have a financial control mechanism to prevent budget overspending, such as a proportional rebate to all pharmaceutical companies receiving any funding from the dedicated funds in the event of an overspend in England and Italy.

Comparison of Cancer Drugs in Thailand, Hong Kong, England, and Italy

Results demonstrated that 269 unique cancer drugs were identified and divided into 15 groups according to the ATC classification system.51,53,81-90 Protein kinase inhibitors had the highest proportion, followed by monoclonal antibodies and miscellaneous in all four countries. All 269 drug lists were reported in Table 3.

Table 3. ATC Classification of Cancer Drugs in Thailand, Hong Kong, England, and Italy .

| ATC classification | Thailand | Hong Kong | England | Italy | ||||||||||||||||

| Reimbursable Under Regular Benefits Package | Reimbursable Under Special Programs | Not Reimbursable | Not Registered | Total | Reimbursable Under Regular Benefits Package | Reimbursable Under the Dedicated Drugs Fund | Not Reimbursable | Not Registered | Total | Reimbursable Under Regular Benefits Package | Reimbursable Under the Dedicated Drugs Fund | Not Reimbursable | Not Registered | Total | Reimbursable Under Regular Benefits Package | Reimbursable Under the Dedicated Drugs Fund | Not Reimbursable | Not Registered | Total | |

| Alkylating agents | 8 | 0 | 2 | 9 | 19 | 11 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 19 | 11 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 19 | 12 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 19 |

| Alkylating agents; platinum coordination complexes | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Antibiotics, cytotoxic | 6 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 13 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 13 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 13 | 8 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 13 |

| Antimetabolites; antifolates | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 5 |

| Antimetabolites; purine analogues | 3 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 7 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| Antimetabolites; pyrimidine analogues | 4 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 10 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 7 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 10 |

| Histone deacetylase inhibitors | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Hormonal agents; antiandrogens | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 8 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 8 |

| Hormonal agents; antiestrogens (including aromatase inhibitors) | 2 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 7 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| Hormonal agents; gonadotropin releasing hormone analogues | 4 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 10 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 10 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 10 | 7 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 10 |

| Hormonal agents; peptide hormones | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Monoclonal antibodies | 4 | 2 | 16 | 22 | 44 | 5 | 13 | 3 | 23 | 44 | 7 | 23 | 8 | 6 | 44 | 22 | 8 | 14 | 0 | 44 |

| Protein kinase inhibitors | 5 | 10 | 27 | 32 | 74 | 4 | 26 | 6 | 38 | 74 | 11 | 42 | 11 | 10 | 74 | 41 | 8 | 25 | 0 | 74 |

| Topoisomerase inhibitors | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 6 |

| Taxanes | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| Vinca alkaloids | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| Biologic response modifiers | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 4 |

| Monoclonal antibodies and topoisomerase inhibitors | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Monoclonal antibodies and cytotoxic agent | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Combination | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 7 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 7 |

| Miscellaneous | 7 | 1 | 9 | 16 | 33 | 11 | 4 | 1 | 17 | 33 | 6 | 11 | 7 | 9 | 33 | 20 | 2 | 11 | 0 | 33 |

| Total | 59 | 15a | 76 | 119 | 269 | 77 | 49b | 17 | 126 | 269 | 74 | 95 | 33 | 67 | 269 | 163 | 18 | 88 | 0 | 269 |

Abbreviation: ATC, Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical.

a Six cancer drugs in Thailand including bevacizumab, dasatinib, imatinib, nilotinib, rituximab, and trastuzumab are reimbursed under regular benefits package of Thailand with additional indications reimbursed under the OCPA.

b Seven cancer drugs in Hong Kong including cetuximab, dasatinib, everolimus, imatinib, interferon alfa, rituximab, and temozolomide are reimbursed under regulars benefit package of Hong Kong with additional indications reimbursed under SF and CCF.

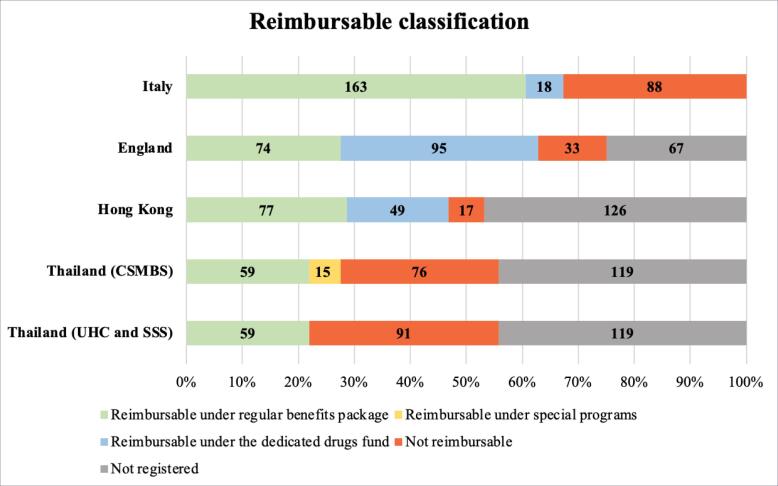

A comparison of the reimbursable classification of 269 cancer drugs across four countries was shown in Figure 2. Italy led with the highest number of cancer drugs available in the country (n = 269), followed by England (n = 202), Thailand (n = 150), and Hong Kong (n = 143). Italy also had the largest number of reimbursable cancer drugs (n = 181), followed by England (n = 169), Hong Kong (n = 126), Thailand for CSMBS (n = 74), and Thailand for UHC & SSS (n = 59). Among the reimbursable cancer drugs, Italy was the country with the highest number of cancer drugs on the regular benefits package (163 cancer drugs, 60.59%), followed by Hong Kong (77 cancer drugs, 53.84%) while England was the country with the highest proportion of drugs in the CDF (95 cancer drugs, 47.03%). Thailand not only had a lower number of reimbursements under the regular benefits package (59 cancer drugs, 39.33%) and a higher number of non-reimbursable drugs (91 cancer drugs, 60.67%) than other countries but also recorded that approximately half of all drugs were not even registered as a licensed drug.

Figure 2.

Reimbursable Classification of Cancer Drugs in Thailand, Hong Kong, England, and Italy. Abbreviations: UHC, universal health coverage; SSS, social security scheme; CSMBS, Civil Servant Medical Benefit Scheme.

Discussion

We specifically reviewed and compared the dedicated funds for cancer drugs utilized by three countries, including Hong Kong, England and Italy. Dedicated funds for cancer drugs have been established with clear objectives. These funds are typically created to enhance access to cancer drugs awaiting transition into the regular reimbursement system. The decision to facilitate access to innovative cancer drugs is distinct from other aspects of cancer care, such as cancer screening, palliative care, and end-of-life treatment, which many of these aspects are already covered by the national health insurance systems in all three countries.

All dedicated funds are publicly financed. Two of these funds receive an annual budget, while the third is allocated a lump sum budget for a 10-year period. The annual budget allocated to the funds in England and Italy is subject to a cap, estimated to be less than 2.5% of the annual national pharmaceutical expenditure. With a fixed budget, the government can allocate funds with certainty each year and evaluate whether to continue utilizing this strategy. In contrast, the funds that receive a lump sum budget can strive for self-sustainability through prudent investment.

The scope of dedicated drug funds may vary. Hong Kong and Italy operate the funds nationwide, while England is the only country within the United Kingdom operating the funds. Moreover, it is worth noting that in Hong Kong and Italy, dedicated funds extend their coverage to both cancer and non-cancer drugs. In contrast, dedicated funds in England specifically target funding for cancer drugs exclusively. The variation in the scope of dedicated funds may reflect the unique healthcare challenges and financial situations in each country.

Management of the dedicated funds varies among the three countries, particularly in terms of drug listing and delisting. Two distinct pathways have emerged: parallel and sequential. In the parallel approach, a single expert committee assesses drugs for reimbursement under three options: (1) regular pharmaceutical benefits scheme, (2) dedicated funds, or (3) non-reimbursement. In contrast, the sequential pathway involves two committees. The first assesses drugs for inclusion in the regular pharmaceutical benefits scheme, with the possibility of proposing non-listed drugs for dedicated funds consideration. The parallel pathway appears more efficient than the sequential one.

The drug selection criteria, including unmet medical need, added therapeutic value, and the quality of the evidence, are consistent across the three countries. In Italy, the quality of the evidence is of paramount importance. If the quality of the evidence is assessed as low or medium, the drugs will not qualify for full innovative status. A recent study by Jommi and Galeone reported that the innovative status is primarily influenced by the added therapeutic value and the quality of the evidence rather than the unmet need.91 Moreover, cancer drugs prescribed for end-of-life care should be deliberately considered with palliative care. The utilization of cancer drugs in such cases may be perceived as a signal of aggressive treatment. Aggressive treatments involving newer cancer drugs do not consistently enhance patients’ conditions or prolong the quality of life. This circumstance can potentially result in the underutilization of palliative care.92

Delisting is another mechanism used in dedicated funds management. England and Italy have established fixed time frames of 24 and 36 months, respectively, for delisting drugs from dedicated funds. Once the grace period ends, the pharmaceutical companies have the option to submit the drug for evaluation under the regular pharmaceutical benefits scheme. In contrast, Hong Kong does not employ a time frame strategy but instead evaluates drugs for delisting on a case-by-case basis through the committee.

Although dedicated funds are seen as ring-fenced, they employ various cost-control mechanisms. MEAs play a central role in cost containment in England and Italy. Financial-based MEAs are more favorable in Italy due to their operational ease and resource efficiency. In contrast, outcome-based MEAs are more favorable in England as it provides evidence for further drug selection decision.

Cost-sharing strategies vary among these countries. In Hong Kong, tiered cost-sharing based on family income is applied within the dedicated funds, but it is not mandatory for drugs covered by the regular pharmaceutical benefits scheme. Conversely, England and Italy require cost-sharing for drugs covered by the regular pharmaceutical benefits scheme but do not impose cost-sharing within dedicated funds. Given the potentially impoverishing impact of cancer on patients and their families, the implementation of cost-sharing strategies should be approached with careful consideration.

Proportional rebate is implemented in both England and Italy. While drug expenditures surpassing budgetary constraints have not hindered patients from continuing their treatment, they have imposed a financial burden on pharmaceutical companies. Notably, in Italy, innovative drug spending exceeded the limit during the second year of implementation, leading to pharmaceutical companies being required to make repayments. While rebates help mitigate financial risk for insurers, they concurrently place a burden on pharmaceutical companies. The dedicated funds will be seen as less attractive if the budget is inadequate and requires a large proportion of rebates.

While dedicated drugs fund enable greater access to innovative drugs, the evaluation of their performance, including clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction, remains limited. The drugs listed in the regular pharmaceutical benefits scheme serve as a tangible trace indicating whether dedicated funds provide the opportunity for innovative drugs to prove their value.

In 2023, an NHS report revealed that out of the 28 drugs listed under the England CDF, 24 had received recommendations from NICE for inclusion in the NHS regular reimbursement system.93

When countries establish a dedicated drugs fund, it is crucial to consider both benefits and risks. While patients will experience improved drug access and an enhanced quality of life, it’s essential to acknowledge that co-pay requirements may persist in certain countries. Physicians might have access to alternative drugs better suited to their patients’ needs. However, accurately recording and reporting clinical outcomes is imperative for assessing the drugs’ potential. Payers can broaden their reimbursement drug lists to aid those in need but must judiciously manage funding sources, control budgets, and contain costs. Moreover, pharmaceutical companies, while introducing new drugs, must be willing to share risks with payers. It’s pivotal to carefully weigh these factors before implementing a dedicated drugs fund.

Policy Recommendations for Thailand

Cancer is the leading cause of death in Thailand. Within the cancer care continuum, the Thai healthcare system provides limited cancer screening (Human papillomavirus screening for women aged 35 and older), cancer treatment (reimbursed cancer drugs according to established cancer protocols), and symptomatic treatment. However, cancer treatment is widely recognized as the most critical aspect. Out-of-pocket payments for drugs not listed in the NLEM are deemed unacceptable for eligible cancer patients covered by the three public health insurance systems.

The issue of access to cancer drugs in Thailand is widely recognized, and numerous stakeholders are continuously working to address it.6,7 Many attempts have recently been pushed forward. In 2022, the Thai Society of Clinical Oncology proposed an updated cancer protocol. If approved by payers, these revised protocols will serve as a framework for cancer drug reimbursement across public health insurance programs in Thailand. Additionally, the sub-committee of the NLEM has recently agreed to exempt rare disease drugs from the regular HTA pathway if they are deemed lifesaving, recommended by national or international clinical practice guidelines, and fall within a reasonable budget. In the same year, the National Health Security Office (NHSO) established a new committee comprising healthcare providers, academia, representatives from the NLEM’s subcommittee, and pharmaceutical companies to address the issue of access to high-cost drugs. This new committee identified MEAs and dedicated drugs fund as attractive and feasible strategies to implement in Thailand’s healthcare system.94

The proposed dedicated drugs fund should aim to enhance access to non-reimbursable drugs with proven added benefits over those in the NLEM, supported by robust evidence of their significant clinical impact. The dedicated drugs fund not only provides additional funding to the healthcare system but also establishes a maximum drug expenditure limit, ensuring that the government does not face a financial crisis while patients receive continuous treatment. The dedicated funds should encompass both cancer and non-cancer drugs, as well as rare diseases. It is imperative that all Thai citizens have equal access to drugs listed in the dedicated drugs fund, irrespective of their health insurance schemes.

The primary source of funding to support the dedicated drugs fund should originate from the government. It is imperative for the government to commit to financing the dedicated drugs fund. An issue that warrants further discussion is the allocation of the budget to the fund. Allocating additional government tax revenue to the fund necessitates the country to make trade-offs with other meaningful projects and activities. Seeking non-governmental tax support, especially from those who will benefit from the fund or private entities seeking tax exemptions, may serve as alternative financial sources that can help ensure the sustainability of the dedicated funds. Additionally, considering other financial sources, such as revenue generated from endowment funds and donations, is also prudent.

Regarding management, the dedicated drugs fund must establish clear drug listing and de-listing criteria, accompanied by a reasonable de-listing timeline. These criteria should be meticulously drafted, undergo a hearing process, and be pilot-tested. The drug selection process should align with the NLEM. This is particularly important as Thailand has a limited number of HTA experts. Utilizing the same expert committee is more efficient, as they can determine whether a new drug should be reimbursed under the NLEM, the dedicated funds, or not reimbursed at all.

The fund administration should be entrusted to an existing organization, such as one of the three public health insurers. The NHSO is considered a potential candidate, as it covers over 70% of the Thai population and is regarded as the most advanced claim administrative system.

Cost-sharing is a contentious issue in the context of Thailand. Given the country’s national-politics-driven health insurance system over the past 20 years, which promised free healthcare access to all Thai citizens, cost-sharing is perceived as the least acceptable strategy. Proposing that individuals contribute to the fund for future utilization may be a more possible approach. Additionally, establishing financial risk-sharing mechanisms between the government and pharmaceutical companies is a crucial aspect of the dedicated drugs fund. When the annual budget is exceeded, proportional rebates should also be considered.

Information technology infrastructure is crucial for successfully implementing dedicated funds. A robust Information technology system should facilitate the tracking of drug utilization under the dedicated drugs fund, encompassing both expenditure and clinical outcomes. Furthermore, the evaluation of outcomes stemming from implementing the dedicated drugs fund should be clearly defined. This evaluation should not only encompass clinical and financial outcomes but also comprehensively assess the impact on the overall healthcare system.

Although the concept of the dedicated drugs fund receives support from many stakeholders, it is worthwhile to consider the opportunity cost associated with its implementation when compared to investing in health education initiatives aimed at raising awareness of cancer self-examination, population-based cancer screening, and palliative care. These areas are either not well-established or are not currently covered under the public health insurance system in Thailand.

Limitations

Our study has some unavoidable limitations. Firstly, the inherent nature of health policy research involving grey literature searches might lead to the omission of recent information. Future studies should consider updating data in countries where dedicated drugs fund is already in use and in countries where these funds have been newly established.

Secondly, the classification of certain cancer drugs as reimbursable could not be thoroughly examined in England due to the unavailability of a positive drugs list, with only the negative drugs list accessible. Consequently, the absence of a positive drugs list made it challenging to determine which drugs were covered by national health insurance. Nonetheless, our findings could serve as a proxy for evaluating access to high-cost innovative cancer drugs in the studied countries. Future studies should consider conducting surveys with key informants in each country to investigate the reimbursement classification of cancer drugs.

Thirdly, this study focused solely on access to cancer drugs in terms of reimbursement status. It did not extend its scope to the timeline for including cancer drugs in the regular benefits package and dedicated drugs fund. Consequently, we were unable to assess the efficiency of the dedicated drugs fund in terms of ensuring timely access to cancer drugs. This issue should be considered in future research.

Conclusion

The dedicated drugs fund is considered an attractive and feasible strategy to enhance access to non-reimbursable high-cost drugs in Thailand. Robust criteria and evaluation processes for drug inclusion in the dedicated drugs fund, as well as for transitioning drugs back into the standard reimbursement drugs list, are crucial. This ensures efficient management and sustained patient access to needed medicines post-exit. Insights from other countries offer a promising solution for limited medication access. To implement the dedicated drugs fund, the responsible organization must thoroughly prepare its structures, objectives, operational plan, funding sources, and management system. Health insurers must balance providing additional cancer treatments and benefits for overall member well-being.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mr. Krit Yodinlom for his diligent support in English language proofreading of this work.

Ethical issues

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by MSD (Thailand) Ltd. The funder had no role in any part of the work, including the design and conduct of the study, as well as manuscript preparation.

Supplementary files

Supplementary file 1 contains Table S1.

Supplementary file 2 contains Table S2.

Citation: Luksameesate P, Nerapusee O, Patikorn C, Anantachoti P. Scoping review of international experience of a dedicated fund to support patient access to cancer drugs: policy implications for Thailand. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2024;13:7768. doi:10.34172/ijhpm.2023.7768

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization (WHO). Global Health Estimates 2020: Deaths by Cause, Age, Sex, by Country and by Region 2000-2019. 2020. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mortality-and-global-health-estimates/ghe-leading-causes-of-death. Accessed February 24, 2021.

- 3. Strategy and Planning Division Ministry of Public Health. Public Health Statistics A.D. 2021. https://bps.moph.go.th/new_bps/sites/default/files/statistic62.pdf. Accessed February 24, 2021.

- 4.Hofmarcher T, Lindgren P, Wilking N, Jönsson B. The cost of cancer in Europe 2018. Eur J Cancer. 2020;129:41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patikorn C, Taychakhoonavudh S, Sakulbumrungsil R, Ross-Degnan D, Anantachoti P. Financing strategies to facilitate access to high-cost anticancer drugs: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2022;11(9):1625–1634. doi: 10.34172/ijhpm.2021.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patikorn C, Taychakhoonavudh S, Thathong T, Anantachoti P. Patient access to anticancer medicines under public health insurance schemes in Thailand: a mixed methods study. Thai J Pharm Sci. 2019;43(3):168–178. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saerekul P, Limsakun T, Anantachoti P, Sakulbumrungsil R. Access to medicines for breast, colorectal, and lung cancer in Thailand. Thai J Pharm Sci. 2018;42(4):221–229. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ettinger DS, Wood DE, Aisner DL, et al. NCCN guidelines insights: non–small cell lung cancer, version 22021: featured updates to the NCCN guidelines. J Natl ComprCancNetw. 2021;19(3):254–266. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2021.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. National Cancer Institute, Department of Medical Services, Ministry of Public Health. Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Lung Cancer. Bangkok: Kosit Printing; 2015.

- 10. Health Intervention and Technology Assessment Program (HITAP) Thailand. Cost-Utility Analysis of Pemetrexed Plus Platinum-Based for the Treatment of Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma Patients. 2017. https://www.hitap.net/documents/172978. Accessed March 22, 2021.

- 11. Health Intervention and Technology Assessment (HITAP) Thailand. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of Temozolomide in the Treatment of Glioblastoma Multiforme and Anaplastic Astrocytoma Patients. 2017. https://www.hitap.net/documents/172978. Accessed March 22, 2021.

- 12. Health Intervention and Technology Assessment Program (HITAP) Thailand. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of Treating Multiple Myeloma Patients Who Do Not Respond Well to Treatments or Relapse with Bortezomib-Based Regimens, Thalidomide-Based Regimens, and Lenalidomide-Based Regimens. 2017. https://www.hitap.net/documents/173069. Accessed March 22, 2021.

- 13.Tanvejsilp P, Taychakhoonavudh S, Chaikledkaew U, Chaiyakunapruk N, Ngorsuraches S. Revisiting roles of health technology assessment on drug policy in universal health coverage in Thailand: where are we? And what is next? Value Health Reg Issues. 2019;18:78–82. doi: 10.1016/j.vhri.2018.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kittirotruji K, Lommuang K, Chumchaiyo C, Taychakhoonavudh S. Use of patient assistance programs (PAPs) to increase access to innovative drugs in Thailand Current situations and prospects. Value Health. 2018;21(Suppl 2):S20. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2018.07.158. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pauwels K, Huys I, Casteels M, De Nys K, Simoens S. Market access of cancer drugs in European countries: improving resource allocation. Target Oncol. 2014;9(2):95–110. doi: 10.1007/s11523-013-0301-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aggarwal A, Fojo T, Chamberlain C, Davis C, Sullivan R. Do patient access schemes for high-cost cancer drugs deliver value to society?-lessons from the NHS Cancer Drugs Fund. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(8):1738–1750. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–473. doi: 10.7326/m18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. World Health Organization (WHO). Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) Classification. https://www.who.int/tools/atc-ddd-toolkit/atc-classification.

- 19.Salcher-Konrad M, Naci H, Davis C. Approval of cancer drugs with uncertain therapeutic value: a comparison of regulatory decisions in Europe and the United States. Milbank Q. 2020;98(4):1219–1256. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Godman B, Malmström RE, Diogene E, et al. Are new models needed to optimize the utilization of new medicines to sustain healthcare systems? Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2015;8(1):77–94. doi: 10.1586/17512433.2015.990380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boncz I, Donkáné Verebes E, Oberfrank F, Kásler M. [Assessment of annual health insurance reimbursement for oncology drugs in Hungary] Magy Onkol. 2010;54(4):283–288. doi: 10.1556/MOnkol.54.2010.4.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Timmins N. At last, NICE to take over the Cancer Drugs Fund. BMJ. 2016;352:i1324. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moye-Holz D, Ewen M, Dreser A, et al. Availability, prices, and affordability of selected essential cancer medicines in a middle-income country - the case of Mexico. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):424. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05167-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Apperley JF. Cancer Drugs Fund and chronic myeloid leukemia: an unhappy alliance. Int J Hematol Oncol. 2016;5(1):1–4. doi: 10.4155/ijh.15.26. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sabry-Grant C, Malottki K, Diamantopoulos A. The Cancer Drugs Fund in practice and under the new framework. Pharmacoeconomics. 2019;37(7):953–962. doi: 10.1007/s40273-019-00793-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grieve R, Abrams K, Claxton K, et al. Cancer Drugs Fund requires further reform. BMJ. 2016;354:i5090. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i5090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Oliveira Avellar W, de Melo AC, da Silva CF, Aran V. Cancer research in Brazil: analysis of funding criteria and possible consequences. J Cancer Policy. 2019;20:100184. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpo.2019.100184. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lakdawalla DN, Jena AB, Doctor JN. Careful use of science to advance the debate on the UK Cancer Drugs Fund. JAMA. 2014;311(1):25–26. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.282839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Littlejohns P, Weale A, Kieslich K, et al. Challenges for the new Cancer Drugs Fund. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(4):416–418. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(16)00100-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hopkinson NS. Conservatism and the Cancer Drugs Fund. BMJ. 2017;357:j2451. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j2451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rajurkar SP, Presant CA, Bosserman LD, McNatt WJ. A copay foundation assistance support program for patients receiving intravenous cancer therapy. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7(2):100–102. doi: 10.1200/jop.2010.000112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rothwell B, Kiff C, Ling C, Brodtkorb TH. Cost effectiveness of nivolumab in patients with advanced, previously treated squamous and non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer in England. Pharmacoecon Open. 2021;5(2):251–260. doi: 10.1007/s41669-020-00245-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Runyan A, Banks J, Bruni DS. Current and future oncology management in the United States. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2019;25(2):272–281. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2019.25.2.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gabe J, Chamberlain K, Norris P, Dew K, Madden H, Hodgetts D. The debate about the funding of Herceptin: a case study of ‘countervailing powers’. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75(12):2353–2361. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stefan DC, Elzawawy AM, Khaled HM, et al. Developing cancer control plans in Africa: examples from five countries. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(4):e189–e195. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(13)70100-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dixon P, Chamberlain C, Hollingworth W. Did it matter that the Cancer Drugs Fund was not NICE? A retrospective review. Value Health. 2016;19(6):879–884. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chamberlain C, Collin SM, Hounsome L, Owen-Smith A, Donovan JL, Hollingworth W. Equity of access to treatment on the Cancer Drugs Fund: a missed opportunity for cancer research? J Cancer Policy. 2015;5:25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpo.2015.06.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morrell L, Wordsworth S, Schuh A, Middleton MR, Rees S, Barker RW. Correction to: will the reformed Cancer Drugs Fund address the most common types of uncertainty? An analysis of NICE cancer drug appraisals. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):198. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4039-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li EC. Exploring pharmacy and drug policy concerns. J Natl ComprCancNetw. 2010;8 Suppl 7:S2–S3. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2010.0131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kang SY, Sen A, Bai G, Anderson GF. Financial eligibility criteria and medication coverage for independent charity patient assistance programs. JAMA. 2019;322(5):422–429. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.9943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Duerden M. From a cancer drug fund to value based pricing of drugs. BMJ. 2010;341:c4388. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cancer drugs dropped from ‘unsustainable’ fund list. Nurs Stand 2015; 30(4):10. 10.7748/ns.30.4.10.s11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Chamberlain C, Collin SM, Stephens P, Donovan J, Bahl A, Hollingworth W. Does the Cancer Drugs Fund lead to faster uptake of cost-effective drugs? A time-trend analysis comparing England and Wales. Br J Cancer. 2014;111(9):1693–1702. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Emmerich N. Calling time on the Cancer Drugs Fund? Funding the NHS in the age of austerity. Br J Hosp Med (Lond) 2015;76(4):186–187. doi: 10.12968/hmed.2015.76.4.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Howard DH. Drug companies’ patient-assistance programs--helping patients or profits? N Engl J Med. 2014;371(2):97–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1401658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maynard A, Bloor K. The economics of the NHS Cancer Drugs Fund. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2011;9(3):137–138. doi: 10.2165/11585750-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McCabe C, Paul A, Fell G, Paulden M. Cancer Drugs Fund 2.0: a missed opportunity? Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;34(7):629–633. doi: 10.1007/s40273-016-0403-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McGuire A, Drummond M, Martin M, Justo N. End of life or end of the road? Are rising cancer costs sustainable? Is it time to consider alternative incentive and funding schemes? Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2015;15(4):599–605. doi: 10.1586/14737167.2015.1039518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Morrell L, Wordsworth S, Rees S, Barker R. Does the public prefer health gain for cancer patients? A systematic review of public views on cancer and its characteristics. Pharmacoeconomics. 2017;35(8):793–804. doi: 10.1007/s40273-017-0511-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Legislative Council. Updated Background Brief on Drug Formulary of the Hospital Authority and Drug Subsidies. LC Paper No. CB(4)973/20-21(06). https://www.legco.gov.hk/yr20-21/english/panels/hs/papers/hs20210514cb4-973-6-e.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2021.

- 51. Hospital Authority. Items Supported by the Samaritan Fund. https://www.ha.org.hk/haho/ho/sf/SF_Items_en.pdf. Accessed November 11, 2021.

- 52. Hospital Authority. Community Care Fund Medical Assistance Programmes. https://www.ha.org.hk/visitor/ha_visitor_index.asp?Parent_ID=10044&Content_ID=206049&Ver=HTML. Accessed November 11, 2021.

- 53. Hospital Authority. Items Supported by the CCF Medical Assistance Programmes. https://www.ha.org.hk/haho/ho/ccf/CCF_items_en.pdf. Accessed November 11, 2021.

- 54.Roe H. Key changes to cancer care in the UK. Br J Nurs. 2015;24(4):S3. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2015.24.Sup4.S3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. NHS England. Cancer Drugs Fund (CDF) Activity Update. https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/cancer-drugs-fund-cdf-activity-update/#heading-2. Accessed December 3, 2021.

- 56. Cancer Research UK. Cancer Drugs Fund (CDF). https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/cancer-in-general/treatment/access-to-treatment/cancer-drugs-fund-cdf. Accessed November 23, 2021.

- 57. NICE and the Cancer Drugs Fund--2020 vision? Drug Ther Bull 2016; 54(4):37. 10.1136/dtb.2016.4.0391. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Emmerich N. Calling time on the Cancer Drugs Fund? Funding the NHS in the age of austerity. Br J Hosp Med (Lond) 2015;76(4):186–187. doi: 10.12968/hmed.2015.76.4.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Palù G. AIFA (Italian Medicines Agency). https://projects.gbreports.com/italy-life-sciences-2021/aifa-interview/. Accessed September 20, 2021.

- 60.Apolone G, Ardizzoni A, Biondi A, et al. Skip pattern approach toward the early access of innovative anticancer drugs. ESMO Open. 2021;6(4):100227. doi: 10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Barham L. 2021 Market Access Prospects for Italy. https://pharmaphorum.com/views-analysis-market-access/2021-market-access-prospects-for-italy/. Accessed August 13, 2021.

- 62. The World Bank Group. World Bank Open Data. 2021. https://data.worldbank.org. Accessed December 1, 2021.

- 63. World Health Organization (WHO). Thailand Medical Products Profile 2019. 2019. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/328915/medicines-profile-tha-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- 64. National Health Security Office. National Health Security Office Performance Report 2021. https://www.nhso.go.th/operating_results/50.

- 65. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Health Spending. https://data.oecd.org/healthres/health-spending.htm#indicator-chart. Accessed December 1, 2021.

- 66. Chief Secretary for Administration of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. Universal Health Coverage. https://www.cso.gov.hk/eng/blog/blog20180401.htm. Accessed December 3, 2021.

- 67. Chang J, Peysakhovich F, Wang W, Zhu J. The UK Health Care System. http://assets.ce.columbia.edu/pdf/actu/actu-uk.pdf. Accessed August 11, 2021.

- 68. Tikkanen R, Osborn R, Mossialos E, Djordjevic A, Wharton GA. International Health Care System Profiles England. 2020. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/international-health-policy-center/countries/england. Accessed November 3, 2021.

- 69.Tarricone R, Listorti E, Tozzi V, et al. Transformation of Cancer Care during and after the COVID Pandemic, a point of no return The Experience of Italy. J Cancer Policy. 2021;29:100297. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpo.2021.100297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Tikkanen R, Osborn R, Mossialos E, Djordjevic A, Wharton GA. International Health Care System Profiles Italy. 2020. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/international-health-policy-center/countries/italy. Accessed November 2, 2021.

- 71. Hospital Authority. Financial Assessment. https://www.ha.org.hk/visitor/ha_visitor_index.asp?content_id=254525. Accessed November 15, 2021.

- 72. Community Care Fund. Community Care Fund Latest Financial Position (as at 31 August 2021). https://www.communitycarefund.hk/en/finance.html. Accessed November 18, 2021.

- 73. Legislative Council of Hong Kong. Legislative Council Panel on Health Services Subcommittee on Issues Relating to the Support for Cancer Patients - Support for Cancer Drug Treatment. 2019. https://www.ha.org.hk/haho/ho/ccf/hs_scp20191216cb2_356_1_e.pd.

- 74. Legislative Council of Hong Kong. Panel on Health Services Meeting on 14 May 2021 - Updated Background Brief on Drug Formulary of the Hospital Authority and Drug Subsidies. 2021. https://www.legco.gov.hk/yr20-21/english/panels/hs/papers/hs20210514cb4-973-6-e.pdf.

- 75. Hospital Authority. Report on the Samaritan Fund. https://www.legco.gov.hk/yr20-21/english/counmtg/papers/cm20201216-sp058-e.pdf. Accessed November 18, 2021.

- 76. NHS England Cancer Drugs Fund Team. Appraisal and Funding of Cancer Drugs from July 2016 (Including the New Cancer Drugs Fund) A New Deal for Patients, Taxpayers and Industry. 2016. https://www.england.nhs.uk/cancer/cdf/. Accessed March 12, 2021.

- 77.Chamberlain C, Owen-Smith A, MacKichan F, Donovan JL, Hollingworth W. “What’s fair to an individual is not always fair to a population”: a qualitative study of patients and their health professionals using the Cancer Drugs Fund. Health Policy. 2019;123(8):706–712. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2019.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Vola F, Vinci B, Golinelli D, Fantini MP, Vainieri M. Harnessing pharmaceutical innovation for anti-cancer drugs: some findings from the Italian regions. Health Policy. 2020;124(12):1317–1324. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2020.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Prada M, Rossi L, Mantovani M. Time to reimbursement and negotiation condition in Italy for drugs approved by the European Medicines Agency during the period 2014-2019. AboutOpen. 2020;7(1):89–94. doi: 10.33393/abtpn.2020.2184. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Statista. Public Expenditure on Innovative Drugs in Italy from 2017 to 2020. https://www.statista.com/statistics/916357/public-expenditure-on-innovative-drugs-in-italy/. Accessed December 1, 2021.

- 81. The National Drug System Development Committee. The National List of Essential Medicines in Thailand. 2021. http://ndi.fda.moph.go.th/uploads/file_news/20210723999860392.pdf. Accessed March 10, 2022.

- 82. National Drug Information. Drugs and Herbal Information. http://ndi.fda.moph.go.th/drug_info. Accessed March 12, 2022.

- 83. Central office of Healthcare Information (CHI). Drug List Under Criteria for Reimbursement. 2022. https://www.chi.or.th/Catalog/Drug_list.html. Accessed April 12, 2022.

- 84. Hospital Authority. Hospital Authority Drug Formulary. https://www.ha.org.hk/hadf/en-us/Updated-HA-Drug-Formulary/Drug-Formulary.html. Accessed April 19, 2022.

- 85. Nottinghamshire Area Prescribing Committee. Formulary Chapters. https://www.nottinghamshireformulary.nhs.uk/chapters.asp. Accessed March 12, 2022.