Abstract

Background

This study aimed to explore the association between perceived social support and eHealth literacy in Chinese nursing students, with a particular emphasis on the mediating effects of self-efficacy, family health, and perceived stress within this relationship.

Method

This study utilized data drawn from the 2023 Psychology and Behavior Investigation of Chinese Residents (PBICR) survey, which involved a sample of 967 nursing students. Structural equation modeling was utilized to examine the relationships among the study variables.

Results

The mediating effect analysis revealed a negative direct relationship between perceived social support and eHealth literacy in Chinese nursing students (β = -0.149, p < 0.001). Both self-efficacy (β = 0.124, p < 0.05) and family health (β = 0.148, p < 0.05) acted as mediators in the association between perceived social support and eHealth literacy. Additionally, perceived social support positively affected eHealth literacy through a chain mediation of self-efficacy, perceived stress, and family health (β = 0.008, p < 0.05).

Conclusion

This study provides valuable insights for developing strategies to enhance nursing students’ eHealth literacy, ultimately contributing to their professional development and the quality of healthcare services they provide.

Keywords: Perceived social support, eHealth literacy, Self-efficacy, Family health, Perceived stress, Nursing students

Introduction

With the rapid development of electronic technological innovations, electronic media such as internet-enabled mobile devices have become crucial channels for information acquisition and communication. People often search for health information online [1]. eHealth literacy refers to the ability to find, access, comprehend, and assess health-related information from digital platforms and subsequently use this information to manage health concerns [2]. For healthcare professionals, especially nurses, the skill to find effective and reliable health information is essential [3]. As future key members in the healthcare sector, nursing students benefit significantly from possessing eHealth literacy, which is vital for their professional development and the quality of healthcare services they provide [4, 5]. In the medical field, knowledge updates rapidly, with new research findings, treatment methods, and technologies continually emerging. Nursing students with eHealth literacy can utilize online resources to stay informed about these new developments, adopt new technologies, and enhance their professional competence, thereby offering higher-quality healthcare services to patients [3, 5]. Elevating eHealth literacy among nursing students helps shape well-rounded healthcare professionals, meeting societal demands, and promoting the advancement of the healthcare industry [4].

Nursing students face a uniquely demanding educational experience that combines rigorous academic coursework with extensive clinical practice. The need for practical skills, emotional resilience, ethical decision-making, interdisciplinary collaboration, and continuous learning sets nursing education apart from many other academic disciplines [6]. Social support may assist them in dealing with these challenges and improve their mental health [7]. Prior studies have confirmed the influence of perceived social support on eHealth literacy [8–10]. Meanwhile, the eHealth literacy levels among nursing students still require improvement [5].

Currently, there remains a gap in understanding how perceived social support affects eHealth literacy. Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory emphasizes the interplay between personal, environmental, and behavioral factors [11]. In this framework, perceived social support and family health are considered environmental factors, while self-efficacy and perceived stress are personal factors. These factors may interact to collectively affect individual behavior, such as eHealth literacy [11]. Specifically, perceived social support may enhance self-efficacy, helping nursing students cope with psychological stress, and may support improvements in their eHealth literacy [12–14]. Family health also plays a critical role by providing emotional support and a stable home environment, which may indirectly foster eHealth literacy [15, 16]. This study aims to explore the relationship between perceived social support and eHealth literacy among Chinese nursing students, focusing on how personal factors (self-efficacy, perceived stress) and environmental factors (perceived social support, family health) interact to affect eHealth literacy. By gaining a deeper understanding of these interactions, this study will help to provide scientific evidence to improve nursing students’ eHealth literacy, offering strategies and new approaches for nursing education.

Background

Perceived social support refers to the perception of available resources or supportive social relationships obtained through social interactions [17], typically encompassing support from parents, friends, teachers, and others. It has been widely acknowledged as a critical factor influencing health behaviors and outcomes [18]. A study conducted on Korean women undergoing breast cancer treatment found that social support significantly impacts eHealth literacy [8], indicating that those who perceive higher support levels are more likely to engage with and benefit from eHealth resources. Similarly, research involving primary care providers in China also found a significant link between social support and eHealth literacy [9]. Furthermore, a study of 947 college students in China found a similar association between social support and eHealth literacy [10]. Within contemporary society, the role of perceived social support may be significant in facilitating individuals’ engagement with eHealth resources, thereby enhancing their eHealth literacy [9].

Self-efficacy refers to an individual’s confidence in their capacity to plan and carry out the actions necessary to handle future situations, serving as a decisive factor influencing behavior [19]. It affects how individuals cope with challenges, their perseverance in the face of difficulties, and their overall engagement in health-promoting activities [20]. According to Social Cognitive Theory, social support can enhance self-efficacy by providing encouragement, modeling effective behaviors, and offering instrumental assistance [11]. Previous research has shown that social support increases self-efficacy, which in turn promotes health behaviors [12]. A cross-sectional mixed methods study confirmed the impact of self-efficacy on eHealth literacy among adolescents [13]. Therefore, high perceived social support may boost individuals’ confidence in their ability to use digital health resources, thereby enhancing their eHealth literacy [11–13].

Family health refers to the overall health and well-being of family members and the family unit as a whole, playing a crucial role in maintaining health and preventing disease [21]. A healthy family creates an environment of belonging and shared care among its members, enhancing their health and quality of life [21]. Research has shown that social support is a positive predictor of family functioning [22]. Families with higher perceived social support can create a supportive environment that provides emotional stability and exhibits strong communication patterns and effective problem-solving skills, all of which contribute to overall family health [23, 24]. Studies have also found that a healthy family environment can boost individuals’ confidence in using eHealth resources, thereby improving their eHealth literacy [15, 16]. Family Systems Theory [25] provides a deeper understanding of these relationships by positing that individuals cannot be understood in isolation from their family unit, as family members are interconnected and interdependent. Within this theoretical framework, perceived social support and eHealth literacy are not simply individual attributes but are instead deeply embedded in the family environment. Therefore, in conditions of high perceived social support and family health, the eHealth literacy of family members may enhance the eHealth literacy of the entire family unit.

Perceived stress reflects a person’s thoughts or feelings regarding their current degree of stress [26]. Nursing students often encounter high levels of stress [6], making effective stress management crucial for maintaining their academic performance and mental health [27]. The stress-buffering model suggests that social support aids individuals in managing crises, better adapting to environmental changes, and increaseing their sense of security and confidence in the face of stress [28]. Additionally, nursing students’ self-efficacy has been proven to significantly affect perceived stress [14]. Therefore, we hypothesize that perceived social support may reduce perceived stress through the mediation of self-efficacy. Moreover, family health is adversely affected by high levels of stress [29]. Families with strong social support networks may tend to exhibit lower stress levels, promoting healthier interactions and environments, which benefit family health, encourage better health behaviors, and ultimately enhance eHealth literacy [15, 16].

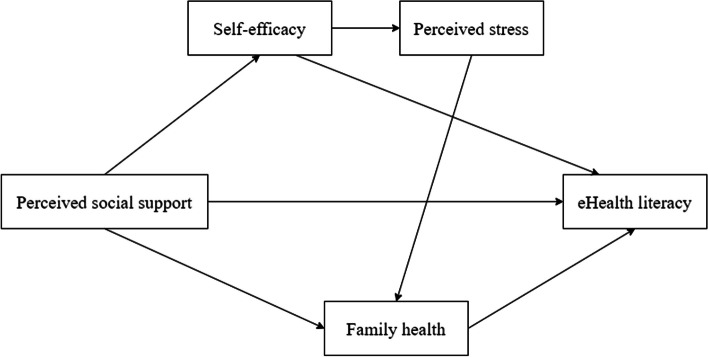

Based on previous research findings, this study suggests the following hypotheses (Fig. 1):

H1: Perceived social support is associated with eHealth literacy.

H2: Self-efficacy mediates the relationship between perceived social support and eHealth literacy.

H3: Family health mediates the relationship between perceived social support and eHealth literacy.

H4: Perceived social support affects the eHealth literacy of nursing students in China through a chain mediation of self-efficacy, perceived stress, and family health.

Fig. 1.

Hypothesized model of the interrelationships of perceived social support, self-efficacy, family health, and perceived stress on eHealth literacy

Method

Participants and procedures

The data for this study was sourced from the 2023 Psychology and Behavior Investigation of Chinese Residents (PBICR), a large-scale, multi-center cross-sectional survey designed to capture comprehensive and representative data on the psychosocial and behavioral characteristics of Chinese residents. Conducted between June 20 and August 31, 2023, the PBICR collected responses from individuals across 150 cities in 22 provinces, 5 autonomous regions, 4 municipalities, and 2 special administrative regions (Hong Kong and Macao), covering 97% of China’s provincial-level administrative divisions. Trained interviewers conducted face-to-face interviews to administer the survey, recording responses on Questionnaire Star, an extensively used online survey tool in China. The process ensured anonymity, with informed consent obtained from all participants. Additional information regarding PBICR methodology is available elsewhere [30].

According to the formula for estimating sample size in structural equation modeling, the sample should be between 10 and 15 times the number of dimensions [31]. In this study, given the presence of 5 dimensions, the sample size was estimated at 15 times the number of dimensions, resulting in a minimum requirement of 75 participants. However, to achieve stable estimations in structural equation modeling, it is advisable to have at least 200 participants [32]. Taking into account a possible 20% rate of invalid responses, it was concluded that a sample size of 240 participants would be necessary.

To focus specifically on nursing students, we restricted our sample to individuals identified as current nursing students. From the original PBICR sample of 45830 participants, 967 nursing students were included in our final analysis.

Ethical considerations

According to the Declaration of Helsinki, this study received ethical approval from the Ethics Review Committee of Shandong Provincial Hospital (No. 2023–198). All participants provided informed consent.

Measures

Demographic characteristics

Age was categorized as 18–20, 21–22, and over 23 years. Gender was classified as woman and man. Ethnicity was divided into Han and minority. Education was categorized as college and below, undergraduate, and master’s degree and above. The place of residence was classified as rural and urban. Hukou was categorized as agricultural and non-agricultural. Religious beliefs and love experience were recorded as no and yes.

Perceived social support

The Perceived Social Support Scale (PSSS) was a 3-item short form to assess perceived social support [18]. Participants responded to items using a 7-point Likert scale, with ratings ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Total scores varied from 3 to 21, with higher scores reflecting greater perceived social support. In this study, the PSSS demonstrated a Cronbach’s α of 0.898.

eHealth literacy

eHealth literacy was assessed using the eHealth Literacy Scale-Short Form (eHEALS-SF) [33], consisting of 5 items. Participants rated each item on a 5-point Likert scale, with responses ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Scores could range from 5 to 25, where higher scores reflect higher eHealth literacy. In this study, the eHEALS-SF demonstrated a Cronbach’s α of 0.931.

Self-efficacy

The 3-item New General Self-Efficacy Scale-Short Form (NGSES-SF) was used to assess self-efficacy [34]. Using a 5-point Likert scale, participants rated the items from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The total scores varied from 3 to 15, with higher scores reflecting higher self-efficacy. In this study, the NGSES-SF demonstrated a Cronbach’s α of 0.947.

Family Health

The Short Form of the Family Health Scale (FHS-SF) was used to measure family health [21]. It was a 10-item scale for assessing family health. Using a 5-point Likert scale, participants rated the items from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Reverse scoring was applied to items 6, 9, and 10. The total scores could vary between 10 and 50, with higher scores reflecting better family health. In this study, the FHS-SF demonstrated a Cronbach’s α of 0.792.

Perceived stress

Perceived stress was evaluated using a 4-item Short Form Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-4) [26]. Participants rated each item on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (very often). Possible scores ranged from 0 to 16, with higher scores indicating higher perceived stress. The PSS-4 demonstrated a Cronbach’s α of 0.939 in this study.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS version 25.0 and Amos version 28.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). P < 0.05 (two-sided test) was considered statistically significant.

First, to evaluate common method bias, a Harman single-factor test was conducted [35]. Second, the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was conducted to determine the normal distribution. Descriptive statistics were reported as frequencies and percentages. Third, Spearman correlation analysis was conducted to explore the relationships between perceived social support, self-efficacy, family health, perceived stress, and eHealth literacy. Finally, structural equation modeling was utilized to examine how self-efficacy, family health, and perceived stress mediate the relationship between perceived social support and eHealth literacy. Bootstrap tests were performed with 5,000 repetitions to assess the significance of the mediating effect, ensuring that the 95% confidence interval (CI) excluded 0. Model fit was assessed based on the following criteria: A chi-squared test of minimum discrepancy divided by degrees of freedom (CMIN/DF) of less than 3 is considered acceptable, while the comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and goodness of fit index (GFI) should all be 0.90 or higher. Additionally, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) should be 0.08 or below, while the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) should not exceed 0.06 [36].

Results

Common method bias test

The Harman single-factor test identified five factors with eigenvalues greater than 1. The initial factor explained 30.063% of the total variance, which is lower than the critical standard of 40%. This suggests that significant common method bias is not present in this study [35].

Demographic characteristics of participants

Among the 967 participants, the majority were aged between 18 and 20 years (49.328%), identified as women (80.558%), belonged to the Han ethnicity (88.314%), were undergraduates (61.531%), resided in urban areas (72.802%), held agricultural hukou (64.012%), did not have religious beliefs (93.899%), and had previous love experiences (61.841%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the participants (N = 967)

| Variables | N | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 18–20 | 477 | 49.328 |

| 21–22 | 256 | 26.474 |

| > 23 | 234 | 24.199 |

| Gender | ||

| Woman | 779 | 80.558 |

| Man | 188 | 19.442 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Han | 854 | 88.314 |

| Minority | 113 | 11.686 |

| Education | ||

| College and below | 204 | 21.096 |

| Undergraduate | 595 | 61.531 |

| Master’s degree and above | 168 | 17.373 |

| Place of residence | ||

| Urban | 704 | 72.802 |

| Rural | 263 | 27.198 |

| Hukou | ||

| Agricultural | 619 | 64.012 |

| Non-agricultural | 348 | 35.988 |

| Religious belief | ||

| No | 908 | 93.899 |

| Yes | 59 | 6.101 |

| Love experience | ||

| No | 369 | 38.159 |

| Yes | 598 | 61.841 |

Percentages might not add up to 100% due to rounding

Descriptive statistics and Spearman correlation analysis

The nursing students exhibited an average eHealth literacy score of 19.800 ± 3.593. Their scores for perceived social support, self-efficacy, family health, and perceived stress were 15.160 ± 3.922, 10.720 ± 2.413, 40.070 ± 5.950, and 4.000 (2.000, 7.000), respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and the correlation between perceived social support, self-efficacy, family health, perceived stress, and eHealth literacy (N = 967)

| Variables | Mean (SD) or median (P25, P75) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Perceived social support | 15.160(3.922) | 1.000 | ||||

| 2. Self-efficacy | 10.720(2.413) | 0.615** | 1.000 | |||

| 3. Family health | 40.070(5.950) | 0.459** | 0.279** | 1.000 | ||

| 4. Perceived stress | 4.000(2.000,7.000) | −0.196** | −0.231** | −0.236** | 1.000 | |

| 5. eHealth literacy | 19.800(3.593) | 0.185** | 0.253** | 0.305** | −0.190** | 1.000 |

**p < 0.01 (two-tailed). Correlations were Spearman correlation coefficients

Spearman correlation analysis indicated that eHealth literacy was positively correlated with perceived social support (rs = 0.185, p < 0.01), self-efficacy (rs = 0.253, p < 0.01), and family health (rs = 0.305, p < 0.01). Perceived social support was positively correlated with self-efficacy (rs = 0.615, p < 0.01) and family health (rs = 0.459, p < 0.01). A positive correlation was also found between self-efficacy and family health (rs = 0.279, p < 0.01). In addition, perceived stress showed negative correlations with perceived social support (rs = −0.196, p < 0.01), self-efficacy (rs = −0.231, p < 0.01), family health (rs = −0.236, p < 0.01), and eHealth literacy (rs = −0.190, p < 0.01) (Table 2).

Mediating effect analysis

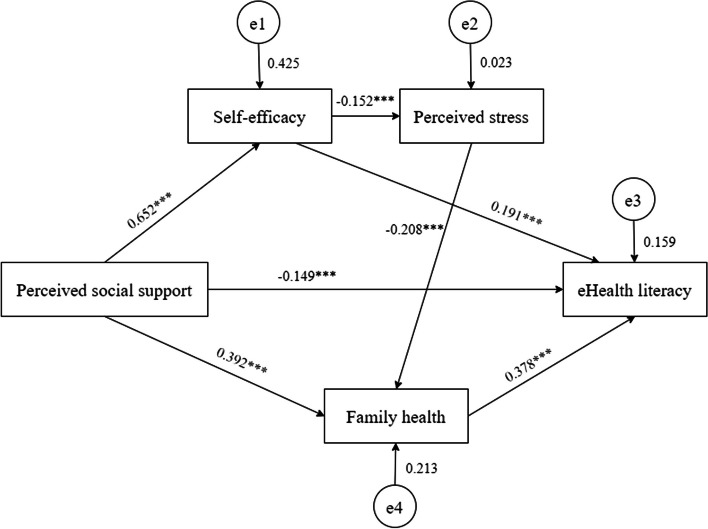

The assessment of the structural equation model revealed that the final version achieved satisfactory goodness-of-fit indices: CMIN = 4.218, DF = 3, CMIN/DF = 1.406, CFI = 0.999, TLI = 0.996, GFI = 0.998, RMSEA = 0.021, SRMR = 0.014. Figure 2 illustrates the standardized path coefficients.

Fig. 2.

Model for the effects of perceived social support, self-efficacy, family health, and perceived stress on eHealth literacy. Note: ***p < 0.001 (two-tailed)

Table 3 presents the results of the structural equation model analysis. First, perceived social support could significantly and positively affect the self-efficacy of nursing students (β = 0.652, p < 0.001, Model 1). Second, self-efficacy could significantly and negatively affect the perceived stress of nursing students (β = −0.152, p < 0.001, Model 2). Third, perceived social support (β = 0.392, p < 0.001) and perceived stress (β = −0.208, p < 0.001) could significantly affect the family health of nursing students (Model 3). Fourth, perceived social support (β = −0.149, p < 0.001), self-efficacy (β = 0.191, p < 0.001), and family health (β = 0.378, p < 0.001) could significantly affect the eHealth literacy of nursing students (Model 4).

Table 3.

Regression analysis of the association between variables in the structural equation model

| Outcome variable | Predictive variable | R2 | β | SEs | t | 95%CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Model 1 | |||||||

| Self-efficacy | Perceived social support | 0.425 | 0.652 | 0.015 | 26.729*** | 0.592 | 0.704 |

| Model 2 | |||||||

| Perceived stress | Self-efficacy | 0.023 | −0.152 | 0.050 | −4.777*** | −0.228 | −0.074 |

| Model 3 | |||||||

| Family health | Perceived social support | 0.213 | 0.392 | 0.044 | 13.662*** | 0.333 | 0.447 |

| Perceived stress | −0.208 | 0.045 | −7.264*** | −0.271 | −0.147 | ||

| Model 4 | |||||||

| eHealth literacy | Perceived social support | 0.159 | −0.149 | 0.038 | −3.638*** | −0.234 | −0.066 |

| Self-efficacy | 0.191 | 0.058 | 4.901*** | 0.110 | 0.268 | ||

| Family health | 0.378 | 0.020 | 11.654*** | 0.300 | 0.453 | ||

***p < 0.001 (two-tailed)

Table 4 presents the results of the mediating effect analysis. The mediating effect of self-efficacy and family health was significant. Specifically, these mediating effects stemmed from three indirect pathways. First, the indirect effect of perceived social support on eHealth literacy through self-efficacy had a path coefficient of 0.124 (Bootstrap 95% CI: 0.073 to 0.180). Second, the indirect effect of perceived social support on eHealth literacy through family health had a path coefficient of 0.148 (Bootstrap 95% CI: 0.114 to 0.186). Third, the indirect effect of perceived social support on eHealth literacy through self-efficacy, perceived stress, and family health had a path coefficient of 0.008 (Bootstrap 95% CI: 0.004 to 0.013).

Table 4.

Total, direct, and indirect effects of perceived social support on eHealth literacy

| Effect types | Paths | Effect | Bootstrap SE | Bootstrap 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect | Perceived social support → eHealth literacy | 0.131 | 0.036 | 0.057 to 0.200 |

| Direct effect | Perceived social support → eHealth literacy | −0.149 | 0.042 | −0.234 to −0.066 |

| Indirect effects | Total indirect effect | 0.280 | 0.033 | 0.220 to 0.348 |

| Perceived social support → Self-efficacy → eHealth literacy | 0.124 | 0.027 | 0.073 to 0.180 | |

| Perceived social support → Family health → eHealth literacy | 0.148 | 0.018 | 0.114 to 0.186 | |

| Perceived social support → Self-efficacy → Perceived stress → Family health → eHealth literacy | 0.008 | 0.002 | 0.004 to 0.013 |

Discussion

This study explored the mediating roles of self-efficacy, family health, and perceived stress in the relationship between perceived social support and eHealth literacy among nursing students in China. In general, the results indicated that the perceived social support had a negative direct effect, a positive indirect effect, and a positive total effect on eHealth literacy. Self-efficacy and family health emerge as pivotal mediating factors, indicating the pathways through which perceived social support affects eHealth literacy. Perceived social support, through a chain mediation of self-efficacy, perceived stress, and family health, indirectly affects the Chinese nursing students’ eHealth literacy.

This study indicated a significantly negative direct effect of perceived social support among nursing students on their eHealth literacy. Therefore, the H1 hypothesis was supported. Previous studies have predominantly underscored the beneficial role of social support in promoting health behaviors and outcomes [37–39], diverging from our findings. We hypothesize this inconsistency may stem from the degree of reliance nursing students place on social support. Within nursing education, various factors such as extensive knowledge acquisition, skill training, clinical internship requirements, stringent assessment and evaluation criteria [40], as well as encountering challenges like managing emergencies during clinical internships [41], may prompt them to seek more social support for coping and adaptation to gain a sense of security and confidence [42]. While social support can offer valuable resources and assistance, an overreliance on others’ support may diminish individual autonomy and self-learning capabilities [43], which can reduce their motivation to actively engage in health-related tasks and subsequently affect the cultivation of their eHealth literacy. Hence, we emphasize the significance of fostering students’ autonomy and problem-solving abilities in nursing education to mitigate excessive reliance on external support. Future research should delve deeper into the potential mechanisms and boundary conditions of this relationship, furnishing insights for tailored interventions and educational strategies aimed at enhancing eHealth literacy across nursing students.

Our findings indicated that perceived social support positively affected eHealth literacy through the mediating role of self-efficacy, thereby supporting the H2 hypothesis. This finding was consistent with Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory, which suggested that self-efficacy is crucial to individuals’ motivation, behavior, and achievement [11]. Perceived social support serves as an important psychosocial resource that individuals may use to deal with challenges and adversities across various life domains [44]. Previous research has shown that social support fosters individuals’ self-efficacy [45]. Nursing students who perceive higher perceived social support may develop stronger beliefs in their ability to effectively navigate and utilize electronic health resources. Individuals with strong self-efficacy are more inclined to actively seek and utilize digital health information, overcome technological barriers, and critically evaluate the credibility and relevance of online health resources [46], which can contribute to their eHealth literacy. Our study underscores the significant roles of perceived social support and self-efficacy in promoting individuals’ eHealth literacy, contributing to a better understanding of the psychosocial factors shaping individuals’ engagement with digital health resources.

Our study revealed that perceived social support among nursing students positively affected eHealth literacy through the mediating role of family health. Thus, the H3 hypothesis was supported. Meanwhile, consistent with the Family Systems Theory [25], individual behavior can be influenced by family circumstances. Previous research has also demonstrated that social support can positively predict family functioning, enabling families to cope with dysfunction and promote family health [22]. Parents have an important role in fostering healthy lifestyles, and a health-promoting family environment encourages individuals to make healthier choices [47]. Therefore, a supportive and health-conscious family environment may facilitate open discussions about health issues and encourage the effective use of digital health tools for health management [15, 16]. By recognizing the impact of family-level factors on eHealth literacy, healthcare practitioners and policymakers can devise interventions and educational programs targeted at the family level to promote eHealth literacy, empowering individuals to take an active role in managing their health.

This study discovered that perceived social support could indirectly affect the eHealth literacy of nursing students in China through a chain mediation effect of self-efficacy, perceived stress, and family health, thereby supporting the H4 hypothesis. Furthermore, the findings offer empirical evidence for Social Cognitive Theory [11], which emphasizes the role of both individual and environmental factors in shaping behavior. Meanwhile, this finding also aligns with the stress-buffering model [28], which suggests that social support increases individual feelings of security and confidence in coping with stress. Previous studies indicated that perceived social support enhances individuals’ self-efficacy, with higher perceived social support may exhibit greater self-efficacy [45, 48]. Nursing students with high self-efficacy are often more confident and optimistic, better equipped to handle challenges and stress, thus potentially experiencing lower perceived stress [49]. When they perceive lower stress, they may demonstrate more positive changes conducive to family health, such as improved mental health, enhanced emotional support, healthier lifestyles, and improved communication, fostering a relaxed and enjoyable family atmosphere [29, 50, 51]. Higher levels of family health may suggest a supportive family environment, potentially increasing their access to health-related resources and aiding in the cultivation of eHealth literacy [15]. This study suggested the importance of comprehensive interventions in nursing education and practice that target not only nursing students’ capacities but also broader social and family environments to promote optimal development in eHealth literacy.

The findings indicated that perceived social support had a direct negative effect on eHealth literacy. However, its total effect remains positive through mediating mechanisms, highlighting the complexity of the relationship between perceived social support and eHealth literacy. This relationship may also be affected by other factors or pathways. For instance, personality traits and cultural backgrounds can affect how nursing students perceive and utilize social support [52]. Additionally, environmental factors such as the accessibility of eHealth resources and the quality of digital health information may impact the association between social support and eHealth literacy [53]. These findings underscore the need for targeted interventions to optimize the positive effect of perceived social support on eHealth literacy while mitigating potential drawbacks. Future research should explore the mechanisms that connect social support to eHealth literacy, aiming to develop targeted strategies for effectively promoting eHealth literacy among nursing students.

This study had several limitations. First, while our sample consisted of 967 nursing students from various regions and diverse educational backgrounds, the extent to which our findings can be generalized may still be restricted. To enhance external validity, future studies should aim to incorporate participants from a broader range of geographic and cultural backgrounds. Second, given the cross-sectional design of this study, establishing causality among the variables is not possible. Longitudinal designs in future research could provide a more thorough exploration of the causal relationships involved. Third, the reliance on self-reported data raises concerns about potential social desirability and recall biases. Future studies should utilize objective measurement instruments to confirm the accuracy of self-reported information.

Conclusion

This study explored the relationship between perceived social support and eHealth literacy in Chinese nursing students, demonstrating the positive effect of perceived social support on eHealth literacy through a mediating role of self-efficacy, perceived stress, and family health. It underscored the interconnection of individual and environmental factors in cultivating health behaviors, highlighting the importance of a holistic approach in nursing education and practice. The findings suggest that nursing education programs should focus on supporting social support systems and fostering a healthy family environment to enhance nursing students’ eHealth literacy. It provides valuable insights into the mechanisms through which perceived social support impacts eHealth literacy, offering practical strategies for developing well-rounded, competent nursing professionals, ultimately contributing to their professional development and the quality of healthcare services they provide.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the participants of the study.

Authors’ contributions

XJS and SZ contributed to the conception and drafted the manuscript. XJS designed the study, formally analyzed, and interpreted the data. YBW contributed to data collection. SZ acquired resources. XJS, SZ, YBW, JL, and XTJ contributed to critical revision of the report. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

None.

Data availability

The data in this study can be obtained from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

According to the Declaration of Helsinki, this study received ethical approval from the Ethics Review Committee of Shandong Provincial Hospital (No. 2023–198). All participants provided informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yibo Wu and Shuang Zang contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Yibo Wu, Email: bjmuwuyibo@outlook.com.

Shuang Zang, Email: zangshuang@cmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Freeman JL, Caldwell PHY, Bennett PA, Scott KM. How Adolescents Search for and Appraise Online Health Information: A Systematic Review. J Pediatr. 2018;195:244-255.e241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Norman CD, Skinner HA. eHEALS: The eHealth Literacy Scale. J Med Internet Res. 2006;8(4): e27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tubaishat A, Habiballah L. eHealth literacy among undergraduate nursing students. Nurse Educ Today. 2016;42:47–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kritsotakis G, Andreadaki E, Linardakis M, Manomenidis G, Bellali T, Kostagiolas P. Nurses’ ehealth literacy and associations with the nursing practice environment. Int Nurs Rev. 2021;68(3):365–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sinan O, Ayaz-Alkaya S, Akca A. Predictors of eHealth literacy levels among nursing students: A descriptive and correlational study. Nurse Educ Pract. 2023;68: 103592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou H, Zhao R, Yang Y. A qualitative study on knowledge, attitude, and practice of nursing students in the early stage of the COVID-19 epidemic and Inspiration for nursing education in Mainland China. Front Public Health. 2022;10: 845588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou L, Sukpasjaroen K, Wu Y, Gao L, Chankoson T, Cai E. Perceived Social Support Promotes Nursing Students’ Psychological Wellbeing: Explained With Self-Compassion and Professional Self-Concept. Front Psychol. 2022;13: 835134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee BE, Uhm JY, Kim MS. Effects of social support and self-efficacy on eHealth literacy in Korean women undergoing breast cancer treatment: A secondary analysis. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. 2023;10(9): 100267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu RH, Shi LS, Xia Y, Wang D. Associations among eHealth literacy, social support, individual resilience, and emotional status in primary care providers during the outbreak of the SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant. Digital health. 2022;8:20552076221089788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu HX, Chow BC, Hassel H, Huang YW, Liang W, Wang RB. Prospective association of eHealth literacy and health literacy with physical activity among Chinese college students: a multiple mediation analysis. Front Public Health. 2024;12:1275691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bandura A. Organisational applications of social cognitive theory. J Australian Journal of management. 1988;13(2):275–302. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi M. Association of eHealth Use, Literacy, Informational Social Support, and Health-Promoting Behaviors: Mediation of Health Self-Efficacy. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(21):7890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taba M, Allen TB, Caldwell PHY, Skinner SR, Kang M, McCaffery K, Scott KM. Adolescents’ self-efficacy and digital health literacy: a cross-sectional mixed methods study. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bodys-Cupak I, Majda A, Zalewska-Puchała J, Kamińska A. The impact of a sense of self-efficacy on the level of stress and the ways of coping with difficult situations in Polish nursing students. Nurse Educ Today. 2016;45:102–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hyman A, Stacy E, Mohsin H, Atkinson K, Stewart K, Novak Lauscher H, Ho K. Barriers and Facilitators to Accessing Digital Health Tools Faced by South Asian Canadians in Surrey, British Columbia: Community-Based Participatory Action Exploration Using Photovoice. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(1): e25863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsu W, Chiang C, Yang S. The effect of individual factors on health behaviors among college students: the mediating effects of eHealth literacy. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(12): e287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barrera M Jr. Distinctions between social support concepts, measures, and models. J American journal of community psychology. 1986;14(4):413–45. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu Y, Tang J, Du Z, Chen K, Zhang X, Wang F, Sun X, Sun X, Wu Y. Development of a Short Version of the Perceived Social Support Scale: Based on Classical Test Theory and Item Response Theory. In: Proceedings of the 25th National Conference of Psychology. Chengdu: Chinese Psychological Society; 2023. p. 539–541.

- 19.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84(2):191–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bodenheimer T, Lorig K, Holman H, Grumbach K. Patient self-management of chronic disease in primary care. JAMA. 2002;288(19):2469–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang F, Wu Y, Sun X, Wang D, Ming WK, Sun X, Wu Y. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of a short form of the family health scale. BMC primary care. 2022;23(1):108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu X, Kong X, Cao Z, Chen Z, Zhang L, Yu B. Social Support and Family Functioning during Adolescence: A Two-Wave Cross-Lagged Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(10):6327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Y, Hu Y, Yang M. The relationship between family communication and family resilience in Chinese parents of depressed adolescents: a serial multiple mediation of social support and psychological resilience. BMC psychology. 2024;12(1):33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.An J, Zhu X, Shi Z, An J. A serial mediating effect of perceived family support on psychological well-being. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(1):940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fingerman KL, Bermann E. Applications of family systems theory to the study of adulthood. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2000;51(1):5–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Warttig SL, Forshaw MJ, South J, White AK. New, normative, English-sample data for the Short Form Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-4). J Health Psychol. 2013;18(12):1617–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiang Z, Jia X, Tao R, Dördüncü H. COVID-19: A Source of Stress and Depression Among University Students and Poor Academic Performance. Front Public Health. 2022;10: 898556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull. 1985;98(2):310–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chua GT, Tung KTS, Kwan MYW, Wong RS, Chui CSL, Li X, Wong WHS, Tso WWY, Fu KW, Chan KL, et al. Multilevel Factors Affecting Healthcare Workers’ Perceived Stress and Risk of Infection During COVID-19 Pandemic. Int J Public Health. 2021;66: 599408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yibo W, Siyuan F, Diyue L, Xinying S. Psychological and behavior investigation of Chinese residents: concepts, practices, and prospects. Chin Gen Pract J. 2024;1(3):149–56.

- 31.Minglong W. Structural equation model: Operation and application of AMOS. Chongqing: Chongqing University Press; 2009.

- 32.Bagozzi RP, Yi Y. Specification, evaluation, and interpretation of structural equation models. J Acad Mark Sci. 2012;40:8–34. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiang F, Wu Y. Survey report on ehealth literacy of Chinese residents. Shanghai: Shanghai Jiao Tong University Press; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fei W, Ke C, Du Z, Wu Y, Tang J, Sun X, Wu Y. Reliability and validity analysis and Mokken model of New General Self-Efficacy Scale-Short Form (NGSES-SF). [Preprint]. PsyArXiv. 2022. Available at: 10.31234/osf.io/r7aj3.

- 35.Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with AMOS: basic concepts, applications, and programming (multivariate applications series). New York: Taylor & Francis Group; 2010.

- 37.Jackson ES, Tucker CM, Herman KC. Health value, perceived social support, and health self-efficacy as factors in a health-promoting lifestyle. Journal of American college health : J of ACH. 2007;56(1):69–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cho JH, Jae SY, Choo IL, Choo J. Health-promoting behaviour among women with abdominal obesity: a conceptual link to social support and perceived stress. J Adv Nurs. 2014;70(6):1381–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Poudel A, Gurung B, Khanal GP. Perceived social support and psychological wellbeing among Nepalese adolescents: the mediating role of self-esteem. BMC psychology. 2020;8(1):43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cao X. Learning of Short Video Text Description of Nursing Teaching Based on Transformer. Comput Intell Neurosci. 2022;2022:6989374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 41.Parreira P, Santos-Costa P, Pardal J, Neves T, Bernardes RA, Serambeque B, Sousa LB, Graveto J, Silén-Lipponen M, Korhonen U, et al. Nursing Students’ Perceptions on Healthcare-Associated Infection Control and Prevention Teaching and Learning Experience in Portugal. J Per Med. 2022;12(2):180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gan Y, Ma J, Wu J, Chen Y, Zhu H, Hall BJ. Immediate and delayed psychological effects of province-wide lockdown and personal quarantine during the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Psychol Med. 2022;52(7):1321–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Luu TT. Family support and posttraumatic growth among tourism workers during the COVID-19 shutdown: The role of positive stress mindset. Tour Manage. 2022;88: 104399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wickramasinghe ND, Dissanayake DS, Abeywardena GS. Prevalence and correlates of burnout among collegiate cycle students in Sri Lanka: a school-based cross-sectional study. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2018;12:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu Y, Aungsuroch Y. Work stress, perceived social support, self-efficacy and burnout among Chinese registered nurses. J Nurs Manag. 2019;27(7):1445–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang D, Hu H, Shi Z, Li B. Perceived Needs Versus Predisposing/Enabling Characteristics in Relation to Internet Cancer Information Seeking Among the US and Chinese Public: Comparative Survey Research. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(1): e24733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sobierajski F, Storey K, Bird M, Anthony S, Pol S, Pidborochynski T, Balmer-Minnes D, Tharani AR, Power A, Khoury M, et al. Use of Photovoice to Explore Pediatric Patients with Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy and their Parents’ Perceptions of a Heart-Healthy Lifestyle. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11(7): e023572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang T, Ren M, Shen Y, Zhu X, Zhang X, Gao M, Chen X, Zhao A, Shi Y, Chai W, et al. The Association Among Social Support, Self-Efficacy, Use of Mobile Apps, and Physical Activity: Structural Equation Models With Mediating Effects. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2019;7(9): e12606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hendrikx IEM, Vermeulen SCG, Wientjens VLW, Mannak RS. Is Team Resilience More Than the Sum of Its Parts? A Quantitative Study on Emergency Healthcare Teams during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(12):6968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shin YC, Lee D, Seol J, Lim SW. What Kind of Stress Is Associated with Depression, Anxiety and Suicidal Ideation in Korean Employees? J Korean Med Sci. 2017;32(5):843–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chiang SL, Chiang LC, Tzeng WC, Lee MS, Fang CC, Lin CH, Lin CH. Impact of Rotating Shifts on Lifestyle Patterns and Perceived Stress among Nurses: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(9):5235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim T, Hong H. Understanding University Students’ Experiences, Perceptions, and Attitudes Toward Peers Displaying Mental Health-Related Problems on Social Networking Sites: Online Survey and Interview Study. JMIR mental health. 2021;8(10): e23465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Levin-Zamir D, Bertschi I. Media Health Literacy, eHealth Literacy, and the Role of the Social Environment in Context. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(8):1643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data in this study can be obtained from the corresponding author on reasonable request.