Abstract

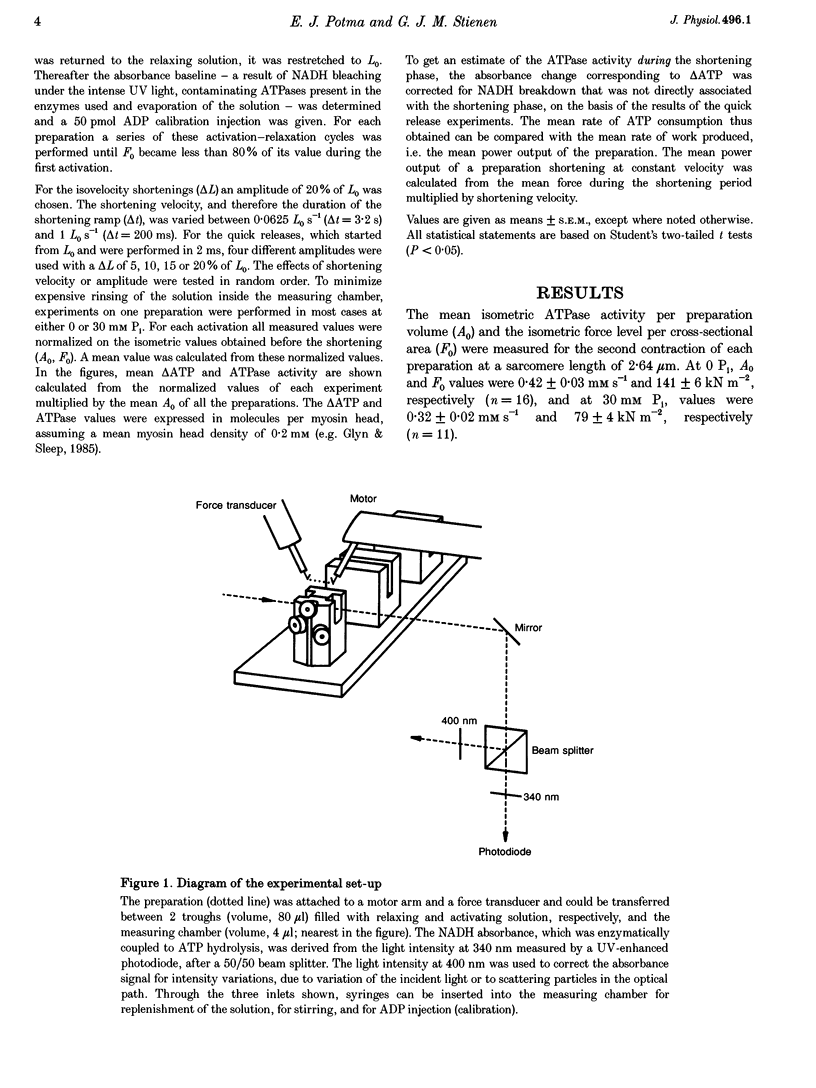

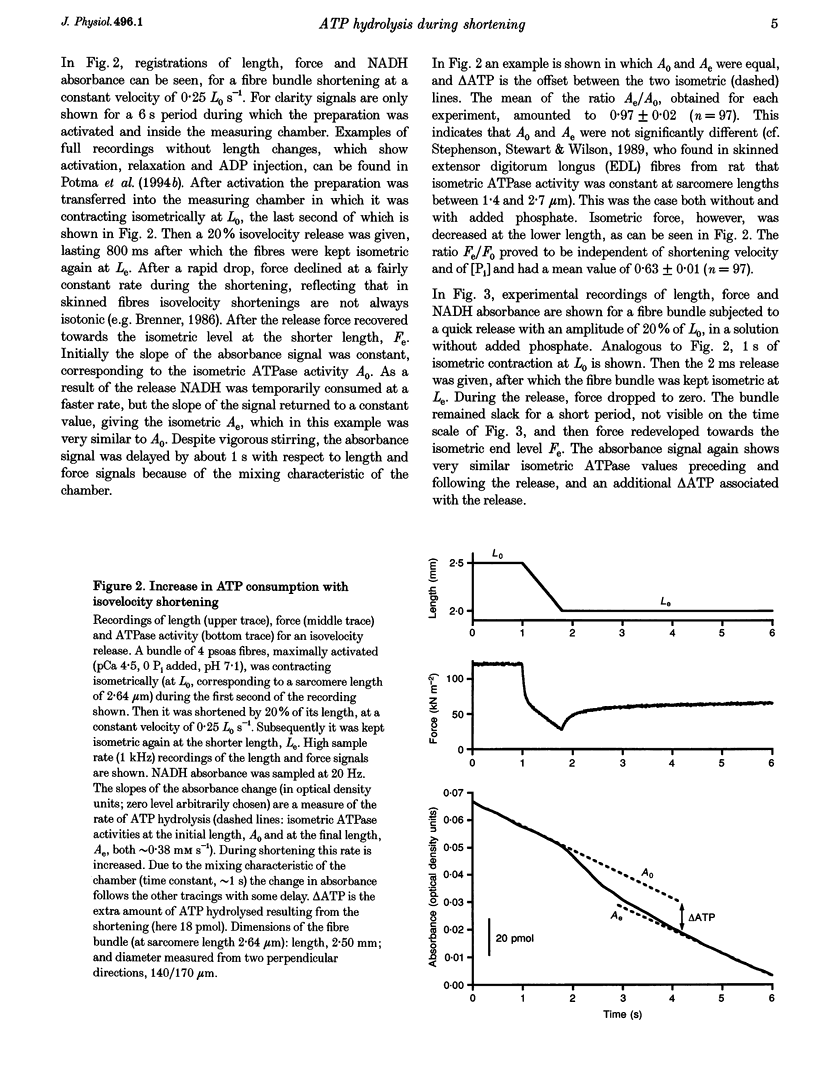

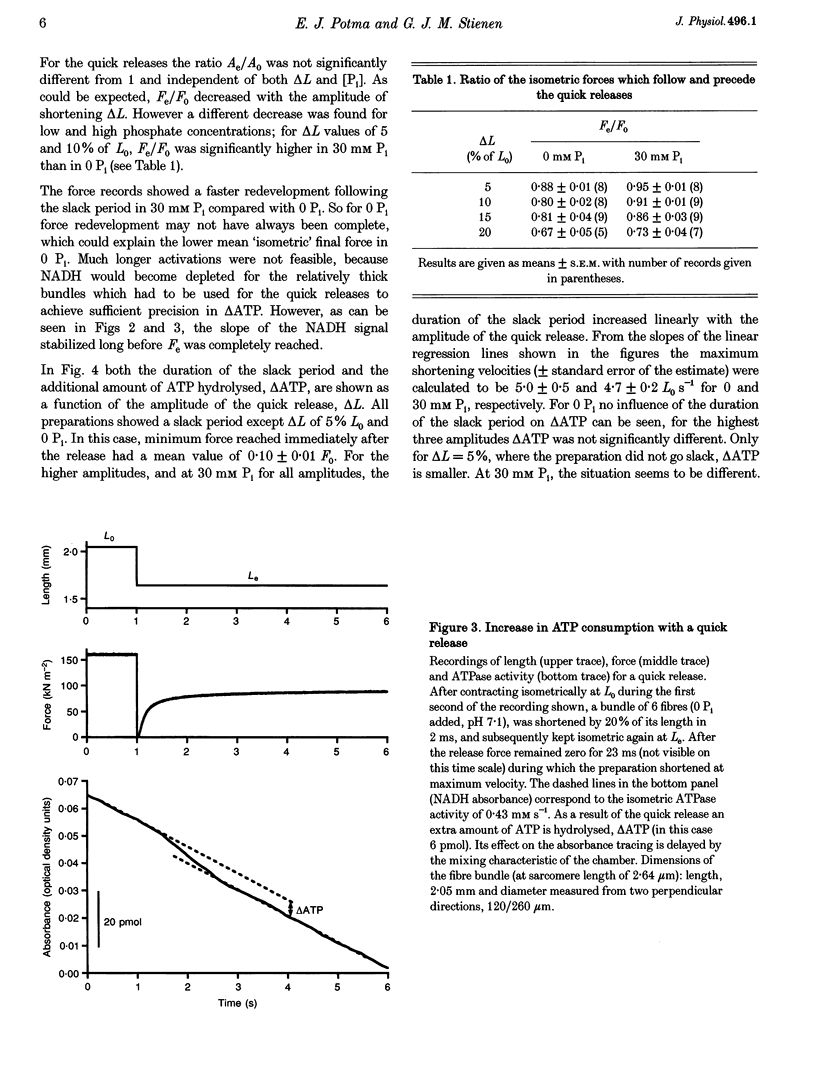

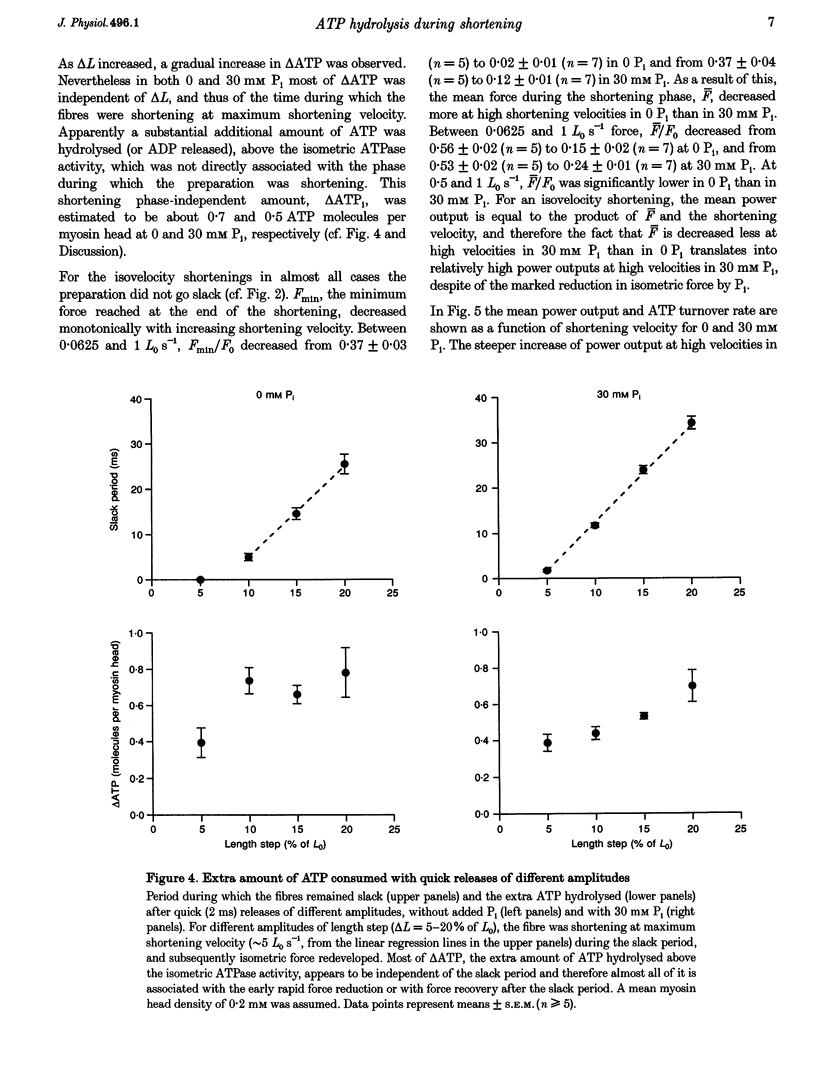

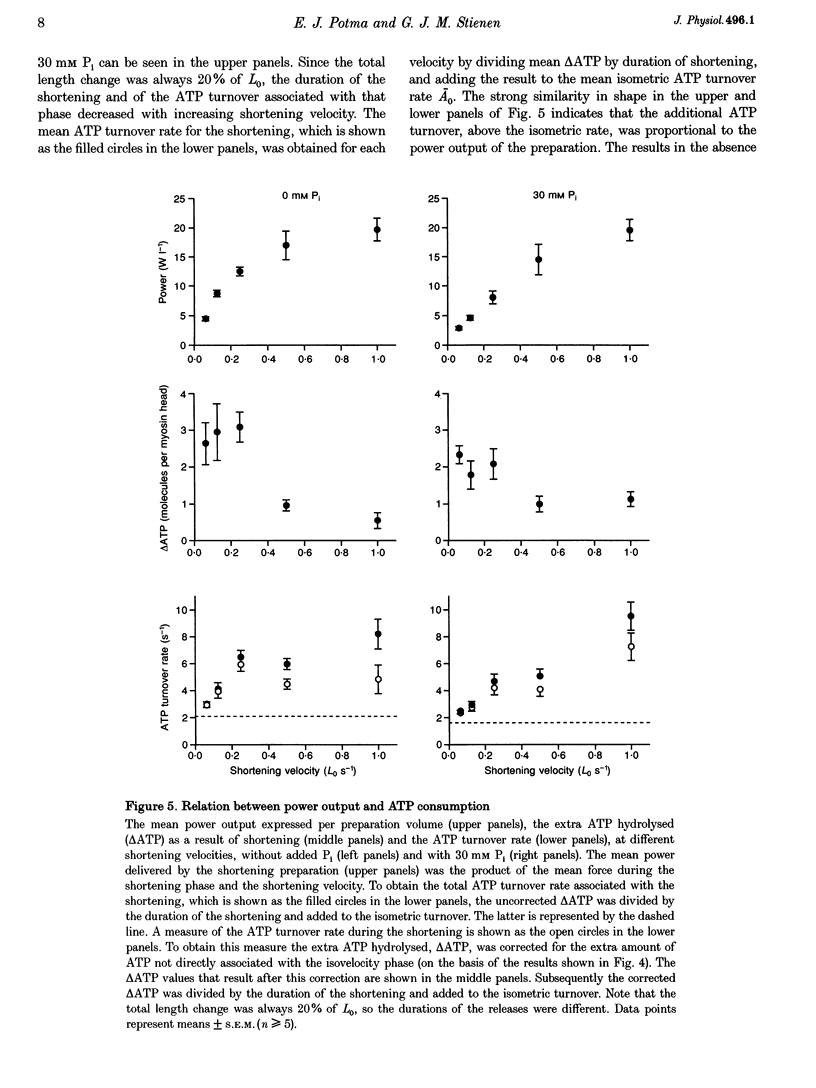

1. The influence of inorganic phosphate (P(i)) on the relationship between ATP consumption and mechanical performance under isometric and dynamic conditions was investigated in chemically skinned single fibres or thin bundles from rabbit psoas muscle. Myofibrillar ATPase activity was measured photometrically by enzymatic coupling of the regeneration of ATP to the oxidation of NADH. NADH absorbance at 340 nm was determined inside a miniature (4 microliters) measuring chamber. 2. ATP consumption due to isovelocity shortenings was measured in the range between 0.0625 and 1 L0 s-1(L0: fibre length previous to shortening, corresponding to a sarcomere length of 2.64 microns), in solutions without added P(i) and with 30 mM P(i). To get an estimate of the amount of ATP utilized during the shortening phase, quick releases of various amplitudes were also performed. 3. After quick releases, sufficiently large that force dropped to zero, extra ATP was hydrolysed which was largely independent of the amplitude of the release and of the period of unloaded shortening. This extra amount, above the isometric ATP turnover, corresponded to about 0.7 and 0.5 ATP molecules per myosin head at 0 and 30 mM P(i), respectively. 4. ATP turnover during the isovelocity shortenings was higher than isometric turnover and increased with increasing shortening velocity up to about 2.7 times the isometric value. At low and moderate velocities of shortening (< 0.5 L0 s-1), P(i) reduced ATP turnover during isovelocity shortening and isometric ATP turnover to a similar extent, i.e. a decrease to about 77% between 0 and 30 mM added P(i). 5. The extra ATP turnover above the isometric value, resulting from isovelocity shortenings studied at different speeds, was proportional to the power output of the preparation, both in the absence and presence of added [P(i)]. 6. The effect of shortening velocity and [P(i)] on energy turnover can be understood in a cross-bridge model that consists of a detached, a non- or low-force-producing, and a force-producing state. In this model, mass action of P(i) influences the equilibrium between the force-producing and the non-or-low-force-producing cross-bridges, and shortening enhances cross-bridge detachment from both attached states.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Arata T., Mukohata Y., Tonomura Y. Coupling of movement of cross-bridges with ATP splitting studied in terms of the acceleration of the ATPase activity of glycerol-treated muscle fibers on applying various types of repetitive stretch-release cycles. J Biochem. 1979 Aug;86(2):525–542. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a132552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barclay C. J., Constable J. K., Gibbs C. L. Energetics of fast- and slow-twitch muscles of the mouse. J Physiol. 1993 Dec;472:61–80. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner B. Rapid dissociation and reassociation of actomyosin cross-bridges during force generation: a newly observed facet of cross-bridge action in muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991 Dec 1;88(23):10490–10494. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.23.10490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner B. The cross-bridge cycle in muscle. Mechanical, biochemical, and structural studies on single skinned rabbit psoas fibers to characterize cross-bridge kinetics in muscle for correlation with the actomyosin-ATPase in solution. Basic Res Cardiol. 1986;81 (Suppl 1):1–15. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-11374-5_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buschman H. P., Elzinga G., Woledge R. C. Energetics of shortening depend on stimulation frequency in single muscle fibres from Xenopus laevis at 20 degrees C. Pflugers Arch. 1995 Jun;430(2):160–167. doi: 10.1007/BF00374646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase P. B., Kushmerick M. J. Effects of pH on contraction of rabbit fast and slow skeletal muscle fibers. Biophys J. 1988 Jun;53(6):935–946. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(88)83174-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke R., Franks K., Luciani G. B., Pate E. The inhibition of rabbit skeletal muscle contraction by hydrogen ions and phosphate. J Physiol. 1988 Jan;395:77–97. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp016909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke R., Pate E. The effects of ADP and phosphate on the contraction of muscle fibers. Biophys J. 1985 Nov;48(5):789–798. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(85)83837-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow M. T., Kushmerick M. J. Chemical energetics of slow- and fast-twitch muscles of the mouse. J Gen Physiol. 1982 Jan;79(1):147–166. doi: 10.1085/jgp.79.1.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantzig J. A., Goldman Y. E., Millar N. C., Lacktis J., Homsher E. Reversal of the cross-bridge force-generating transition by photogeneration of phosphate in rabbit psoas muscle fibres. J Physiol. 1992;451:247–278. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebus J. P., Stienen G. J., Elzinga G. Influence of phosphate and pH on myofibrillar ATPase activity and force in skinned cardiac trabeculae from rat. J Physiol. 1994 May 1;476(3):501–516. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg E., Hill T. L., Chen Y. Cross-bridge model of muscle contraction. Quantitative analysis. Biophys J. 1980 Feb;29(2):195–227. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(80)85126-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiato A. Myoplasmic free calcium concentration reached during the twitch of an intact isolated cardiac cell and during calcium-induced release of calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum of a skinned cardiac cell from the adult rat or rabbit ventricle. J Gen Physiol. 1981 Nov;78(5):457–497. doi: 10.1085/jgp.78.5.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenn W. O. A quantitative comparison between the energy liberated and the work performed by the isolated sartorius muscle of the frog. J Physiol. 1923 Dec 28;58(2-3):175–203. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1923.sp002115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenn W. O. The relation between the work performed and the energy liberated in muscular contraction. J Physiol. 1924 May 23;58(6):373–395. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1924.sp002141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glyn H., Sleep J. Dependence of adenosine triphosphatase activity of rabbit psoas muscle fibres and myofibrils on substrate concentration. J Physiol. 1985 Aug;365:259–276. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman Y. E., Hibberd M. G., Trentham D. R. Relaxation of rabbit psoas muscle fibres from rigor by photochemical generation of adenosine-5'-triphosphate. J Physiol. 1984 Sep;354:577–604. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Güth K., Poole K. J., Maughan D., Kuhn H. J. The apparent rates of crossbridge attachment and detachment estimated from ATPase activity in insect flight muscle. Biophys J. 1987 Dec;52(6):1039–1045. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(87)83297-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUXLEY A. F. Muscle structure and theories of contraction. Prog Biophys Biophys Chem. 1957;7:255–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heglund N. C., Cavagna G. A. Mechanical work, oxygen consumption, and efficiency in isolated frog and rat muscle. Am J Physiol. 1987 Jul;253(1 Pt 1):C22–C29. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1987.253.1.C22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibberd M. G., Dantzig J. A., Trentham D. R., Goldman Y. E. Phosphate release and force generation in skeletal muscle fibers. Science. 1985 Jun 14;228(4705):1317–1319. doi: 10.1126/science.3159090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibberd M. G., Trentham D. R. Relationships between chemical and mechanical events during muscular contraction. Annu Rev Biophys Biophys Chem. 1986;15:119–161. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.15.060186.001003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- INFANTE A. A., KLAUPIKS D., DAVIES R. E. ADENOSINE TRIPHOSPHATE: CHANGES IN MUSCLES DOING NEGATIVE WORK. Science. 1964 Jun 26;144(3626):1577–1578. doi: 10.1126/science.144.3626.1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto H. Strain sensitivity and turnover rate of low force cross-bridges in contracting skeletal muscle fibers in the presence of phosphate. Biophys J. 1995 Jan;68(1):243–250. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80180-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julian F. J., Morgan D. L. Variation of muscle stiffness with tension during tension transients and constant velocity shortening in the frog. J Physiol. 1981;319:193–203. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai M., Güth K., Winnikes K., Haist C., Rüegg J. C. The effect of inorganic phosphate on the ATP hydrolysis rate and the tension transients in chemically skinned rabbit psoas fibers. Pflugers Arch. 1987 Jan;408(1):1–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00581833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martyn D. A., Gordon A. M. Force and stiffness in glycerinated rabbit psoas fibers. Effects of calcium and elevated phosphate. J Gen Physiol. 1992 May;99(5):795–816. doi: 10.1085/jgp.99.5.795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara I., Elliott G. F. X-ray diffraction studies on skinned single fibres of frog skeletal muscle. J Mol Biol. 1972 Dec 30;72(3):657–669. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(72)90183-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQUATE J. T., UTTER M. F. Equilibrium and kinetic studies of the pyruvic kinase reaction. J Biol Chem. 1959 Aug;234(8):2151–2157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosek T. M., Fender K. Y., Godt R. E. It is diprotonated inorganic phosphate that depresses force in skinned skeletal muscle fibers. Science. 1987 Apr 10;236(4798):191–193. doi: 10.1126/science.3563496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pate E., Cooke R. A model of crossbridge action: the effects of ATP, ADP and Pi. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 1989 Jun;10(3):181–196. doi: 10.1007/BF01739809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pate E., Cooke R. Addition of phosphate to active muscle fibers probes actomyosin states within the powerstroke. Pflugers Arch. 1989 May;414(1):73–81. doi: 10.1007/BF00585629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potma E. J., Stienen G. J., Barends J. P., Elzinga G. Myofibrillar ATPase activity and mechanical performance of skinned fibres from rabbit psoas muscle. J Physiol. 1994 Jan 15;474(2):303–317. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potma E. J., van Graas I. A., Stienen G. J. Effects of pH on myofibrillar ATPase activity in fast and slow skeletal muscle fibers of the rabbit. Biophys J. 1994 Dec;67(6):2404–2410. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80727-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potma E. J., van Graas I. A., Stienen G. J. Influence of inorganic phosphate and pH on ATP utilization in fast and slow skeletal muscle fibers. Biophys J. 1995 Dec;69(6):2580–2589. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80129-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REYNARD A. M., HASS L. F., JACOBSEN D. D., BOYER P. D. The correlation of reaction kinetics and substrate binding with the mechanism of pyruvate kinase. J Biol Chem. 1961 Aug;236:2277–2283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleep J., Glyn H. Inhibition of myofibrillar and actomyosin subfragment 1 adenosinetriphosphatase by adenosine 5'-diphosphate, pyrophosphate, and adenyl-5'-yl imidodiphosphate. Biochemistry. 1986 Mar 11;25(5):1149–1154. doi: 10.1021/bi00353a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson D. G., Stewart A. W., Wilson G. J. Dissociation of force from myofibrillar MgATPase and stiffness at short sarcomere lengths in rat and toad skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 1989 Mar;410:351–366. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stienen G. J., Papp Z., Elzinga G. Calcium modulates the influence of length changes on the myofibrillar adenosine triphosphatase activity in rat skinned cardiac trabeculae. Pflugers Arch. 1993 Nov;425(3-4):199–207. doi: 10.1007/BF00374167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stienen G. J., Roosemalen M. C., Wilson M. G., Elzinga G. Depression of force by phosphate in skinned skeletal muscle fibers of the frog. Am J Physiol. 1990 Aug;259(2 Pt 1):C349–C357. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1990.259.2.C349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stienen G. J., Zaremba R., Elzinga G. ATP utilization for calcium uptake and force production in skinned muscle fibres of Xenopus laevis. J Physiol. 1995 Jan 1;482(Pt 1):109–122. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veech R. L., Lawson J. W., Cornell N. W., Krebs H. A. Cytosolic phosphorylation potential. J Biol Chem. 1979 Jul 25;254(14):6538–6547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker J. W., Lu Z., Moss R. L. Effects of Ca2+ on the kinetics of phosphate release in skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem. 1992 Feb 5;267(4):2459–2466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerblad H., Lee J. A., Lännergren J., Allen D. G. Cellular mechanisms of fatigue in skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol. 1991 Aug;261(2 Pt 1):C195–C209. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1991.261.2.C195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshizaki K., Seo Y., Nishikawa H., Morimoto T. Application of pulsed-gradient 31P NMR on frog muscle to measure the diffusion rates of phosphorus compounds in cells. Biophys J. 1982 May;38(2):209–211. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(82)84549-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]