Abstract

Acute dependence to nicotine can rapidly elicit withdrawal symptoms. However, protracted withdrawal signs from acute nicotine dependence have not been explored. Here, we demonstrate that acute nicotine dependence induces delayed neurobehavioral defects in mice. Acute nicotine dependence led to impairment in passive avoidance but without changes in innate anxiety or learning/memory. Concurrently, F-actin level in the dorsal striatum was aberrantly increased, striatal dendritic spine density was reduced, and striatal neural population activity was diminished after acute nicotine dependence. The smoking-related and synapse-associated microRNA miR-27b was decreased in the dorsal striatum throughout the protracted phase of acute nicotine dependence. In silico analysis with empirical validation revealed the neuronal membrane-associated gene Marcks as a direct inhibition target of miR-27b, and that striatal Marcks was aberrantly enhanced after acute nicotine dependence. Our data collectively indicate that acute nicotine dependence accompanies a series of protracted neurobehavioral sequelae with striatal structural, electrophysiological, and molecular dysfunctions.

Subject terms: Reward, Addiction

Early nicotine withdrawal causes a long-lasting impairment in passive avoidance, accompanied by aberrant changes in microRNA, neural activity, and dendritic spines in the dorsal striatum.

Introduction

Nicotine is the principal psychoactive substance in tobacco and thought as the critical determinant of tobacco addiction1. Early withdrawal-like behavioral signs can develop from short-term exposure to nicotine in both animals2–7 and humans8–10, which has been recognized as “acute dependence” to nicotine4,11–13. The pathophysiological significance of acute dependence has not been well-established. However, the withdrawal/negative effect constitutes an essential stage in the addiction cycle14, which suggests that acute dependence on nicotine could be an important contributing factor in the development of tobacco addiction.

Prior studies have demonstrated that nicotine dependence causes various behavioral deficits in the early phase2–7,9,10,15. However, the protracted signs of acute nicotine dependence have not been well-characterized to date. As protracted withdrawal (or protracted abstinence) and early withdrawal seem to involve distinct biological mechanisms16, it is essential to characterize the neurobehavioral consequences of acute nicotine dependence during the protracted phase.

Recent studies have discovered that a neuron-enriched microRNA (miRNA), miR-27b, is linked to cigarette smoking17,18. miR-27b is a highly conserved miRNA that controls presynaptic transcriptome by silencing transcriptional repressors19. miR-27b knockdown reduces synaptogenesis and neural network activity. In terms of neurological disorders, miR-27b has been associated with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia20. These studies collectively suggest that miR-27b is an essential modulator of neuronal function. However, the role of miR-27b in the neurobiology of nicotine dependence has not been investigated to date.

In the brain, the dorsal striatum is a hub of nicotine dependence. Previous studies have shown that nicotine dependence leads to functional synaptic alterations in the dorsal striatum21–23. Moreover, the dorsal striatum has been identified as a critical regulatory component of nicotine withdrawal in our previous studies24. These findings collectively suggest that the neural correlates of nicotine dependence exist in the dorsal striatum, and that aberrant regulation of the dorsal striatum is causally linked to nicotine dependence.

In this study, we characterize the delayed impacts of acute nicotine dependence on behavior, miRNA, and neural plasticity. We show that acute nicotine dependence impairs passive avoidance and dysregulates striatal miR-27b/Marcks pathway during the protracted phase of withdrawal. In accordance, acute nicotine dependence causes structural and functional changes in the dorsal striatum, such as in dendritic spines and neural population activity. These data collectively indicate that acute nicotine dependence could cause persisting changes in the brain and behavior.

Results

Previous studies have shown that early withdrawal can be precipitated after acute nicotine exposure2,4,5, which has been established as a mouse model of acute nicotine dependence. Accordingly, in our previous study, mice were treated with 0.5 mg/kg (-)-Nicotine ditartrate for 3 days to mimic the light nicotine exposure during the initial experimentation stage of cigarette smoking, and 3.0 mg/kg mecamylamine (MEC) was administered in the next day to precipitate early nicotine withdrawal7, thereby generate a mouse model of acute dependence to nicotine. Here, we examined the impact of acute nicotine dependence during the protracted phase defined as 1–7 days after mecamylamine-induced precipitation of nicotine withdrawal25, during which the immediate pharmacological effects of mecamylamine have been washed out. The overall timeline of animal modeling and experiments is depicted in Fig. S1.

The protracted phase of acute nicotine dependence is marked by impairment in passive avoidance

Withdrawal symptoms can be divided into somatic, affective, and cognitive aspects. The somatic signs rapidly dissipate days after induction of nicotine withdrawal in rodents6,25–27, suggesting that the acute symptoms of nicotine withdrawal are hallmarked by somatic signs. On the other hand, the affective and cognitive signs emerge and persist during the protracted phase of nicotine withdrawal25,28. Thus, we evaluated anxiety-like behavior and learning/memory during the protracted phase of acute nicotine dependence.

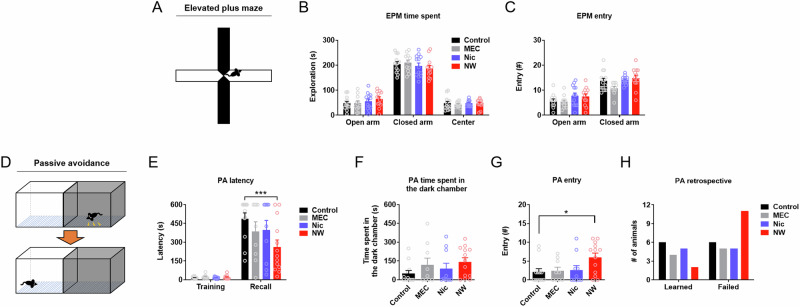

The mouse model of acute nicotine dependence showed no change in anxiety-like behavior in the elevated plus maze (Fig. 1A–C) (n = 11–13/group). However, mice displayed a significant impairment in avoidance behavior in the passive avoidance test during the protracted phase of acute nicotine dependence (Fig. 1D and E, PA latency) (n = 9–13/group) (between-subject two-way repeated measures (RM) ANOVA, Group effect, F(3,40) = 2.371, p = 0.0848; Dunnett’s post-hoc analysis, ***p = 0.0007). Further examination of the passive avoidance behavior showed that the time spent in the dark chamber was not significantly affected by acute nicotine dependence (Fig. 1F, PA time spent in the dark chamber), but the number of entries into the dark chamber was increased by acute nicotine dependence (Fig. 1G, PA entry) (Ordinary one-way ANOVA, Group effect, F(3,40) = 3.200, p = 0.0334; Dunnett’s post-hoc analysis, *p = 0.0255). Lastly, retrospective assessment visually summarized that the ratio of mice “failing” to learn the passive avoidance behavior (latency < 600 s) was notably higher than those of all other groups (Fig. 1H, PA retrospective).

Fig. 1. Acute nicotine dependence induces a delayed deficit in inhibitory avoidance behavior.

A Illustration of elevated plus maze test (EPM). B Time spent in each arm in the EPM. MEC, mecamylamine. Nic, nicotine. NW, nicotine withdrawal (acute nicotine dependence). C Number of entries into each arm in the EPM. D Illustration of passive avoidance test (PA). E Latency to enter the dark chamber during training or recall phase of the PA. F Time spent in the dark chamber during the recall phase of the PA. G Number of entries into the dark chamber in the PA. H Retrospective assessment of the number of mice that “Learned” (latency = 600 s) or “Failed” to learn (latency < 600 s) the passive avoidance behavior. Data represent mean ± S.E.M. See also Fig. S1.

Alternatively, mice did not exhibit changes in spatial object recognition during the protracted phase of acute nicotine dependence (Fig. 2A–C) (n = 8–9/group). Interestingly, mice showed an increase in social object exploration time after either nicotine exposure or acute nicotine dependence (Fig. 2D and E, SI object exploration time) (n = 12–14/group) (Between-subject two-way RM ANOVA, Group effect, F(3,48) = 8.416, p = 0.0001; Dunnett’s post-hoc analysis, ***p = 0.0001). However, mice did not exhibit change in social interaction ratio during the protracted phase of acute nicotine dependence (Fig. 2F, SI preference), which is presumed to be due to a non-significant increase in empty object exploration time after acute nicotine dependence (Fig. 2E, SI object exploration time, Empty). Lastly, mice did not show an increase in somatic signs during the protracted phase of acute nicotine dependence (Fig. 2G–I) (n = 7–8/group).

Fig. 2. Acute nicotine dependence does not affect spatial memory, sociability, or somatic signs.

A Illustration of spatial object recognition test (SOR). B Object exploration time during training or recall phase of the SOR. MEC, mecamylamine. Nic, nicotine. NW, nicotine withdrawal (acute nicotine dependence). C Recognition index during the recall phase of the SOR. D Illustration of social interaction test (SI). E Object exploration time (empty vs. social object) during the SI. F Social interaction ratio in the SI. G Illustration of the measurement of somatic withdrawal signs (SW). H Individual number of somatic signs. I Total number of somatic signs. Data represent mean ± S.E.M. See also Fig. S1.

These results indicated that (1) acute nicotine dependence leads to a delayed impairment in passive avoidance behavior, and (2) acute nicotine dependence increases exploratory behavior toward social conspecific.

Protracted phase of acute nicotine dependence disrupts small RNAs in the dorsal striatum

In the brain, the dorsal striatum is a hub of avoidance behavior29–31 and nicotine dependence21–24. Previous studies have shown that nicotine dependence leads to functional synaptic alterations in the dorsal striatum22,23. As such, we probed the dorsal striatum during the protracted phase of acute nicotine dependence. Small RNAs are regulatory non-coding RNAs with approximately 22 nucleotides in length32. Small RNAs play essential roles in function and disease. Here, we explored the potential alterations in small RNAs within the dorsal striatum after acute nicotine dependence.

Small RNA sequencing (RNA-seq.) was performed. Sample distribution analyses revealed that the total distribution and read length-wise distribution of striatal small RNAs were unchanged by acute nicotine dependence (Fig. S2A and S2B) (n = 3/group). Bioinformatics analysis through sRNAbench33 revealed that the type-specific proportions of striatal small RNAs were not significantly altered by acute nicotine dependence (Figure S2C).

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are the most abundantly expressed small RNAs (Fig. S2C, miRNA(sense))34, and has been associated in the pathophysiology of drug dependence35. Isolating miRNAs from the small RNA-seq., hierarchical clustering analysis through Morpheus36 revealed that acute nicotine dependence led to significant changes in miRNA expression profile (Fig. S2D). Statistical analysis of miRNA expression data with FDR correction (q-value = 1%) revealed that 13 miRNAs were significantly altered in response to acute nicotine dependence: miR-9-5p, miR-22-3p, miR-26a-5p, miR-27b-3p, miR-30a-5p, miR-101a-3p, miR-127-3p, miR-128-3p, miR-138-5p, miR-143-3p, miR-181a-5p, miR-411-5p, and miR-434-3p (Table 1).

Table 1.

Significantly altered microRNAs in the dorsal striatum after acute nicotine dependence

| Name | q-value (FDR) | Fold change | t ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| miR-9-5p | 7.95E−13 | 1.06 | 7.19 |

| miR-22-3p | 0.00E + 00 | 0.88 | 27.65 |

| miR-26a-5p | 2.36E−37 | 0.94 | 12.95 |

| miR-27b-3p | 4.90E−07 | 0.96 | 5.04 |

| miR-30a-5p | 0.00E + 00 | 1.08 | 18.45 |

| miR-101a-3p | 1.21E−04 | 1.07 | 3.85 |

| miR-127-3p | 0.00E + 00 | 0.94 | 47.55 |

| miR-128-3p | 5.39E−09 | 0.91 | 5.85 |

| miR-138-5p | 1.85E−12 | 0.84 | 7.07 |

| miR-143-3p | 3.01E−06 | 1.05 | 4.68 |

| miR-181a-5p | 6.00E−15 | 0.98 | 7.84 |

| miR-411-5p | 3.82E−05 | 0.94 | 4.12 |

| miR-434-3p | 0.00E + 00 | 0.85 | 14.32 |

q-value (FDR), false discovery rate-adjusted p-value (cutoff = 1%). Fold change, mean expression value of acute nicotine dependence group over mean expression value of control group.

These small RNA-seq. data revealed that (1) acute nicotine dependence does not alter the global proportion of small RNA species in the dorsal striatum, and (2) the miRNA expression profile in the dorsal striatum is changed in response to acute nicotine dependence.

The protracted phase of acute nicotine dependence disrupts the synaptic membrane-associated miRNA miR-27b

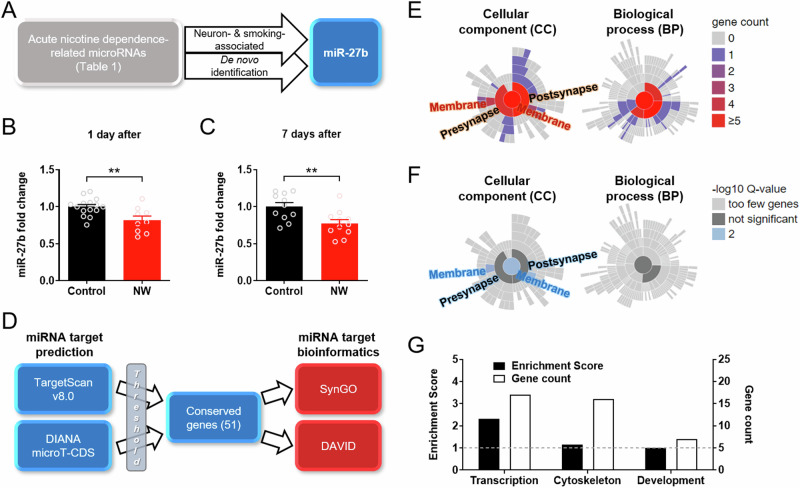

Among the 13 identified miRNAs, the neuron-enriched miRNA miR-27b has recently been directly associated with cigarette smoking17,18 and synaptic functioning19, but the relationship between brain miR-27b and nicotine dependence has not been explored to date (Fig. 3A). To bridge acute nicotine dependence to striatal synaptic dysfunctions, we examined the impact of acute nicotine dependence on striatal miR-27b in detail.

Fig. 3. Acute nicotine dependence-responsive microRNA miR-27b is associated with synaptic membrane and cytoskeleton.

A Schematic outline of target miRNA selection process. B Expression level of miR-27b in the dorsal striatum at 1 day after acute nicotine dependence. NW, nicotine withdrawal (acute nicotine dependence). C Expression level of miR-27b in the dorsal striatum at 7 days after acute nicotine dependence. D Schematic outline of miR-27b targetome prediction process (conserved genes) and bioinformatics-based analyses of miR-27b targetome. E Analysis of miR-27b targetome with SynGO annotation based on gene count. F Analysis of miR-27b targetome with SynGO annotation based on –log10(q-value). G Analysis of miR-27b targetome with DAVID functional annotation clustering based on gene count and enrichment score. Data represent mean ± S.E.M. See also Figure S2–S4 and Table S1~S3.

First, miRNA in situ hybridization assay showed that miR-27b was primarily found in the nuclear compartment of majority of cells in the dorsal striatum (Fig. S3). Considering that miR-27b is a neuron-enriched miRNA, this finding suggested that miR-27b is mainly localized to the nucleus of neurons, at least in the dorsal striatum. Second, striatal miR-27b was reduced at 1 day after (Fig. 3B) (n = 9–15/group) (Student’s t-test, t = 3.062, df = 22; **p = 0.0057) and 7 days after acute nicotine dependence (Fig. 3C) (n = 11/group) (Student’s t-test, t = 2.997, df = 20; **p = 0.0071). These results indicated that striatal miR-27b was reduced throughout the protracted phase of acute nicotine dependence.

Given the sparse distribution of the latency in passive avoidance behavior after acute nicotine dependence, correlation between striatal miR-27b expression and passive avoidance was calculated. First, Pearson correlation analysis revealed that striatal miR-27b expression level was not correlated with the passive avoidance behavior (r < 0.1). Second, the intercepts of regression lines were significantly different between groups (Figure S4) (intercept test, F(1,19) = 6.874, p = 0.0168), which indicates that acute nicotine dependence alters passive avoidance behavior. However, the slopes of regression lines were not significantly different from zero.

miRNAs innately function through inhibition of other molecular targets. This supports the notion that striatal miR-27b would indirectly influence behavior through miR-27b-dependent molecular alterations. Subsequently, the putative gene targets and functional roles of miR-27b were predicted through miRNA targetome analyses (Fig. 3D), in which the putative gene targets were identified through TargetScan v8.0 and DIANA microT-CDS37,38 (Table S1; miRNA targetome). Subsequently, the functional roles of miR-27b were predicted through SynGO and DAVID39,40. SynGO cellular component (CC) annotation revealed that the miR-27b targetome was mainly associated with the synaptic membranes (Fig. 3E and F) (Table S2). DAVID functional annotation clustering revealed that the miR-27b targetome was mainly involved in transcription, cytoskeleton, and development (Fig. 3G) (Table S3).

These results demonstrated that (1) acute nicotine dependence reduces the expression level of striatal miR-27b, and (2) the miR-27b targetome control transcription-, cytoskeleton-, and synaptic membrane-associated functions.

Protracted phase of acute nicotine dependence aberrantly increases striatal Marcks

Bioinformatics analyses revealed that miR-27b is linked to synaptic membrane-associated genes. To specify the potential role of miR-27b, we experimentally verified the inhibition target(s) of miR-27b related to the synaptic membrane functions.

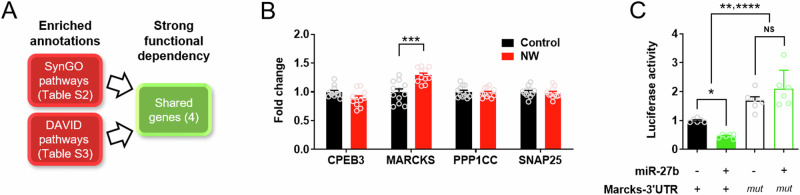

Delving into the miR-27b targetome identified four commonly found genes in the functional annotations (i.e. genes shared in the SynGO CC annotation (Table S2) and DAVID functional annotation clustering (Table S3)) (Fig. 4A): Cpeb3, Marcks, Ppp1cc, and Snap25. qPCR validation revealed that the mRNA of Marcks (myristoylated alanine-rich C-kinase substrate) was significantly increased in the dorsal striatum during the protracted phase of (at 7 days after) acute nicotine dependence, but not the other genes (Fig. 4B) (n = 11–12/group) (Between-subject two-way RM ANOVA, Interaction effect, F(3,60) = 13.26, p < 0.0001; Two-stage linear step-up procedure of Benjamini, Krieger and Yekutieli, ****p < 0.0001 for Marcks).

Fig. 4. The neurite-enriched gene Marcks is a direct inhibition target of miR-27b.

A Schematic outline of process for selecting the mRNA target of miR-27b with strong functional dependency thoughout the miR-27b-related biological pathways. B qPCR analysis of the selected, putative gene targets of miR-27b. NW, nicotine withdrawal (acute nicotine dependence. C Luciferase assay. **miR-27b(-)/Marcks-3’UTR(+) vs. miR-27b/Marcks-3’UTR(mut). ****miR-27b(+)/Marcks-3’UTR(+) vs. miR-27b/Marcks-3’UTR(mut). mut, 3’UTR mutant. Data represent mean ± S.E.M. See also Table S2–S4.

Subsequently, luciferase assay revealed that Marcks mRNA 3’UTR was reduced in response to miR-27b overexpression (Fig. 4C) (n = 6/group) (Between-subject one-way ANOVA, Group effect, F(3, 20) = 24.34, p < 0.0001; Sidak’s post-hoc analysis, *p = 0.0354 for miR-27b(–)/Marcks-3’UTR(+) vs. miR-27b(+)/Marcks-3’UTR(+)), while Marcks 3’UTR mutation rendered miR-27b overexpression ineffective in reducing Marcks mRNA 3’UTR (miR-27b(+)/Marcks-3’UTR(mut) vs. miR-27b(–)/Marcks-3’UTR(mut)).

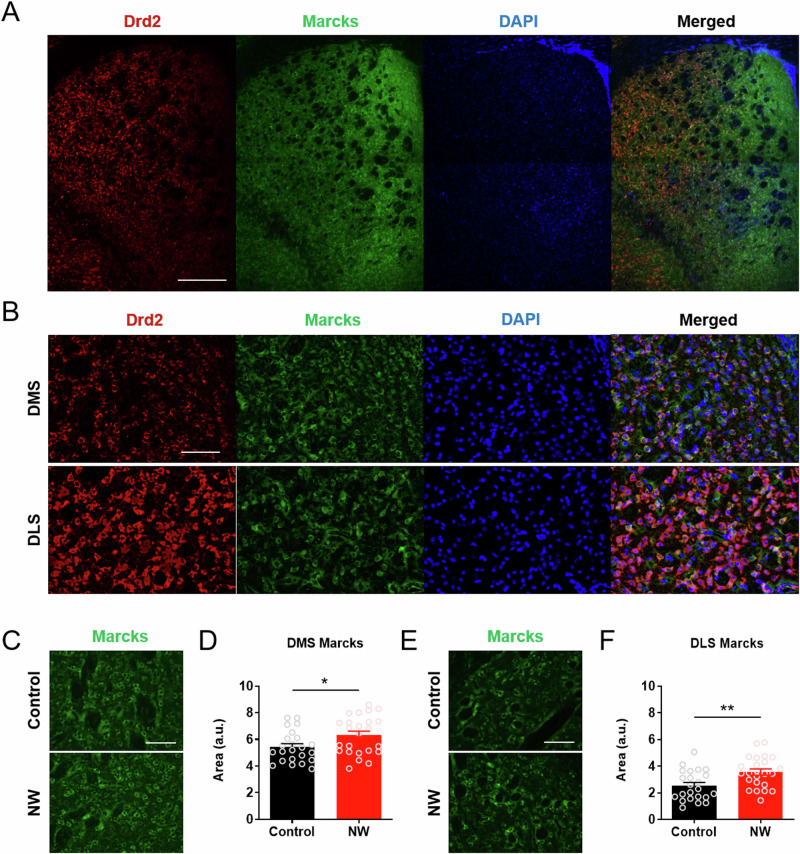

Change in mRNA expression does not necessarily correspond to protein expression41,42, and the dorsomedial and the dorsolateral striatum (DMS and DLS, respectively) play distinct functional roles in drug dependence43. Therefore, Marcks protein expression was separately examined within the DMS and DLS during the protracted phase of acute nicotine dependence. In the immunohistochemical images of wild-type mice, the Marcks protein was significantly enriched in DMS, which opposed the expression pattern of dopamine receptor D2 (Drd2) protein (Fig. 5A). A closer examination of the images revealed that the Marcks protein was mainly localized to the plasma membrane and co-localized with Drd2 protein in both the DMS and DLS (Fig. 5B; see merged images). Comparison of the Marcks protein expression via corrected total cell fluorescence analysis revealed that the Marcks protein was significantly increased in the whole dorsal striatum after acute nicotine dependence (Fig. 5C–F) (n = 23 ~ 24/group) (Student’s t-test; t = 2.341, 3.088; df = 45, 45; *p = 0.0237 for DMS, **p = 0.0034 for DLS). On the other hand, the Drd2 level in the dorsal striatum did not differ after acute nicotine dependence (Fig. S5).

Fig. 5. Marcks expression is aberrantly increased in the dorsal striatum after acute nicotine dependence.

A A representative immunohistochemical image of Marcks and Drd2 in the dorsal striatum of wild-type mouse. Scale bar, 500 µm. B Representative immunohistochemical images of Marcks and Drd2 in the dorsomedial and dorsolateral striatum of wild-type mouse. Scale bar, 100 µm. C Representative immunohistochemical images of Marcks protein in the dorsomedial striatum (DMS). Scale bar, 100 µm. D Quantification of Marcks protein in the DMS by corrected total cell fluorescence analysis. E Representative immunohistochemical images of Marcks protein in the dorsolateral striatum (DLS). Scale bar, 100 µm. F Quantification of Marcks protein in the DLS by corrected total cell fluorescence analysis. Data represent mean ± S.E.M. See also Fig. S5.

These results collectively implied that (1) miR-27b directly inhibits expression of the cytoskeleton-associated gene Marcks, and (2) Marcks in the striatal D2-expressing indirect pathway is aberrantly increased in the whole dorsal striatum after acute nicotine dependence.

Protracted phase of acute nicotine dependence alters striatal dendritic spines and neural population activity

In the adult brain, Marcks protein physically interacts with actin cytoskeleton at the plasma membrane and plays a role in dendritic spine maintenance and synaptic plasticity44–46. These findings suggest that Marcks is associated with neuronal structure and activity. Thus, we lastly examined the impact of acute nicotine dependence on dendritic spines and neural activity in the dorsal striatum.

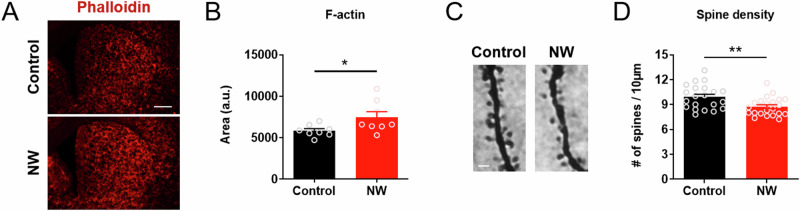

First, immunohistochemical visualization and quantification of filamentous actin (F-actin) via phalloidin staining revealed that acute nicotine dependence caused an aberrant increase in striatal F-actin level (Fig. 6A) (n = 8/group) (Student’s t-test; t = 2.285; df = 14; *p = 0.0384). Second, spine density analysis from Golgi-Cox images revealed that acute nicotine dependence led to a reduction in striatal dendritic spines (Fig. 6B) (n = 21 ~ 22/group) (Student’s t-test; t = 3.070; df = 41; **p = 0.0038).

Fig. 6. Acute nicotine dependence impairs actin dynamics in the dorsal striatum.

A A representative immunohistochemical images of F-actin. Scale bar, 500 µm. B Corrected total fluorescence analysis of F-actin expression level in the dorsal striatum. NW, nicotine withdrawal. C A representative immunohistochemical images of dendritic spines. Scale bar, 2 µm. D Golgi-Cox image showing dendritic spine density in the dorsal striatum. Data represent mean ± S.E.M.

Next, neural activity in the dorsal striatum was examined after acute nicotine dependence via multi-electrode array (MEA) recording before and after bath application of nicotine solution (Baseline and Nicotine, respectively) (Fig. 7A). First, the step current-wise striatal neural population activity was reduced after acute nicotine dependence (Fig. 7B and C) (n = 9 ~ 11/group) (for Fig. 7C, Control-Baseline vs. NW-Baseline, between-subject two-way RM ANOVA, Group effect, F(1,18) = 6.660, p = 0.0188; Fisher LSD post-hoc analysis, **p = 0.0063 at 500 nA, *p = 0.0487 at 625 nA, **p = 0.0075 at 875 nA) (for Fig. 7C, Control-Nicotine vs. NW- Nicotine, between-subject two-way RM ANOVA, Group effect, F(1,18) = 3.502, p = 0.0776; Fisher LSD post-hoc analysis, #p = 0.0462). Also, the cumulative number of neural population activity in the dorsal striatum was reduced after acute nicotine dependence (Fig. 7D) (Between-subject two-way RM ANOVA, Group effect, F(1,21) = 5.181, p = 0.0353; Fisher LSD post-hoc analysis, *p = 0.0291 for Control-Baseline vs. NW-Baseline, *p = 0.0456 for Control-Nicotine vs. NW-Nicotine), while the bath application of nicotine solution did not affect the striatal neural population activity.

Fig. 7. Acute nicotine dependence reduces neural population activity in the dorsal striatum.

A Experimental schedule for ex vivo striatal recording of neural population activity and neural oscillations. Experimental schedule outline, with a representative image of the dorsal striatal slice on the multi-electrode array. B Representative traces of striatal neural population spikes. Control, in vivo exposure to vehicle. NW, in vivo nicotine withdrawal. Baseline, ex vivo ACSF incubation. Nicotine, ex vivo nicotine incubation. C Number of striatal neural population spikes per step current. *,**Control-Baseline vs. NW-Baseline. #Control-Nicotine vs. NW-Nicotine. D Cumulative number of striatal neural population spikes. E Representative traces of local field potential recorded from the dorsal striatum. F Normalized power spectral density (PSD) per frequency band. G Sample entropy. Data represent mean ± S.E.M.

Next, neural oscillations were analyzed in the dorsal striatum after acute nicotine dependence (Fig. 7E). Normalized power spectral density (PSD) of the striatal delta oscillation was significantly reduced by bath application of nicotine in the control group (Fig. 7F) (n = 9–11/group) (Between-subject two-way RM ANOVA, Group effect, F(3,36) = 3.237, p = 0.0334; Fisher LSD post-hoc analysis in Delta, **p = 0.0044 for Control-Baseline vs. Control-Nicotine, **p = 0.0034 for NW-Baseline vs. Control-Nicotine). However, the bath nicotine-induced reduction of striatal delta oscillations was absent after acute nicotine dependence (Fig. 7F) (NW-Baseline vs. NW-Nicotine). In contrast, striatal sample entropy did not significantly change after acute nicotine dependence or by bath application of nicotine (Fig. 7G).

These data collectively demonstrated that (1) acute nicotine dependence impairs synaptic structural dynamics in the dorsal striatum, (2) acute nicotine dependence reduces the neural population activity in the dorsal striatum, and (3) acute nicotine dependence diminishes the nicotine-induced reduction in striatal delta oscillations.

Discussion

This study provided evidence that the protracted phase of acute nicotine dependence accompanies distinct behavioral, molecular, and electrophysiological phenotypes in mice. After acute nicotine dependence, mice showed an impairment in passive avoidance with changes in striatal miR-27b/Marcks pathway, dendritic spine, and neural activity. These findings suggest that the various molecular and neurophysiological alterations in the dorsal striatum may be associated with the protracted behavioral sign of acute nicotine dependence.

Molecular changes in acute nicotine dependence

While yet to be recognized by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)28, the existence of protracted symptoms from acute dependence has been reported in previous studies16,47. This “post-acute withdrawal syndrome” (PAWS) or protracted withdrawal affects many people after repeated substance use. During the early phase, drug withdrawal signs are thought to arise from the abrupt removal of the pharmacological effects of substance use48, while during the protracted phase, drug withdrawal signs are thought to be caused by residual dysregulation of the brain system after acute dependence49. The short-lasting nature (in the range of a few minutes to hours) of acute dependence generally precludes the involvement of gene expression changes (in the range of hours to days), but the delayed nature of protracted withdrawal may be associated with changes in gene expression.

In accordance, we found that the neuron-enriched miRNA miR-27b and its inhibition target Marcks (myristoylated alanine-rich C-kinase substrate) were concurrently dysregulated in the dorsal striatum in response to acute nicotine dependence. This finding suggests that the changes in gene expressions play a role in the pathophysiology of acute nicotine dependence.

miR-27b/Marcks pathway in acute nicotine dependence

miR-27b has been identified as a cigarette smoking-related miRNA in previous studies17,18. miR-27b plays an important role in cigarette-associated immune responses possibly through miRNA interference, and dysregulation of circulating miR-27b was prominent in active cigarette smokers. However, its role in the brain during nicotine dependence and relevant molecular targets have not been investigated to date. Here, we implemented in silico functional annotation of the miRNA targetome50,51, followed by experimental validation of the miRNA inhibition target. Through this streamlined analysis, miR-27b was found to be involved in synaptic membrane and cytoskeleton-related function, and directly inhibit the membrane-bound protein Marcks. These results support the idea that miRNA targetome analysis is useful in exploring miRNA function and targets. Moreover, in association with the previous studies17,18 showing that miR-27b is altered in the periphery in response to cigarette smoking, our data suggest that miR-27b is systemically altered in response to cigarette smoking, which implies that miR-27b could be a systemic marker of acute nicotine dependence. In the future, studies are warranted to reveal the causality between miR-27b and the behavioral deficits induced by acute nicotine dependence.

As with miR-27b, the role of Marcks in nicotine dependence has not been revealed to date. Marcks is a ubiquitous, brain-enriched, and membrane-bound protein that promotes actin polymerization by crosslinking F-actin44. Marcks plays various roles in neurons including neurogenesis, dendritic spine maintenance, synaptic plasticity, and neurotransmitter release44,45. In terms of pathophysiology, Marcks has been associated with various neurological disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, schizophrenia, depression, and bipolar disorders. Our data additionally demonstrated that striatal Marcks is associated with acute nicotine dependence. As with miR-27b, further studies are required to reveal the causal relationship between Marcks and the behavioral signs of acute nicotine dependence. Use of Marcks antagonist such as MANS peptide or BIO-11006 may prove beneficial for the treatment of nicotine dependence52,53.

Neurophysiological changes in the dorsal striatum after acute nicotine dependence

Here, we found that acute nicotine dependence leads to an increased level of F-actin and a lower level of dendritic spine density in the dorsal striatum, which suggests that acute nicotine dependence impairs the structural neural plasticity of the dorsal striatum. Previous studies found that Marcks is an F-actin cross-linking protein46, and that F-actin cross-linking increases phalloidin immunoreactivity54. Actin cross-linking is an important step in dendritic spine stabilization55. Our data imply that acute nicotine dependence-mediated upregulation of Marcks leads to an uncontrolled increase in F-actin cross-linking, which may contribute to the reduction of dendritic spine density by depleting the readily polymerizable F-actin pool necessary for normal dendritic spine maintenance. Further research is required to uncover the causal relationship between Marcks, F-actin dynamics, and dendritic spines.

In addition to the aberrant regulation of cytoskeleton dynamics, acute nicotine dependence also reduced the striatal neural population activity and the nicotine-dependent decrease in delta oscillations, which suggests that acute nicotine dependence impairs the functional neural plasticity of the dorsal striatum. Previous studies have demonstrated that acute nicotine dependence induces various deficits in striatal neural activity. Interestingly, the significant reduction in striatal neural population spikes23,56 and the abnormal change in striatal delta oscillation power24 were identified as the hallmarks of chronic nicotine dependence. These results suggest that acute and chronic nicotine dependence share certain neurophysiological deficits that signify post-acute withdrawal syndrome.

Consideration on the route of nicotine administration

The route of nicotine administration is known to significantly affect the pharmacokinetics of nicotine. In terms of face validity, an animal model of vapor nicotine inhalation of would better mirror human behavior as nicotine is primarily absorbed through lungs following inhalation of tobacco smoke in humans. The key difference is that cigarette smoke inhalation leads to rapid delivery of nicotine to the brain (in a few seconds), while systemic injection of nicotine by i.p. or s.c. route leads to slower delivery (in tens of minutes)57. The speed of drug absorption is known to critically affect the rewarding effects of drugs of abuse58,59, and the stress from repeated nicotine injections may also affect animal behavior.

However, previous studies have proven that the non-contingent repeated nicotine injection undoubtedly changes the subsequent responses of animals in a wide range of behaviors including brain reward threshold and conditioned place preference60. More importantly, unlike drug addiction, drug dependence does not necessarily require experiencing the reinforcing effect of drugs as dependence can also develop from drug misuse61, and it has been documented that the behavioral signs of nicotine withdrawal are similar in animals after either nicotine inhalation or injection62. These findings collectively support that the pathogenesis of nicotine dependence is less likely affected by the route of nicotine administration. Still, further studies are warranted to clarify this point.

Limitations

Limitations exist in this study. First, the effect by potential sex difference was not tackled. Previous studies have suggested that the symptomatic severity of tobacco abstinence is similar in both genders63,64, which suggests that the clinical importance of nicotine withdrawal in females should not be dismissed. In this regard, the gender-specific impact of acute nicotine dependence must be explored in depth in the future.

Second, the striatal subregion-specific effect was not tackled in depth. The dorsal striatum can be subdivided into the dorsolateral and dorsomedial parts (DLS and DMS, respectively). The two subregions receive separable inputs from various brain regions and are involved in different functional processes. These circuit and functional distinctions between the DLS and DMS suggest that the two striatal subregions could play different roles in acute nicotine dependence. In this study, we showed that Marcks protein was increased in both the DLS and DMS, suggesting that the acute nicotine dependence influences the whole dorsal striatum. However, additional studies are necessary to reveal the causal link between the specific subregions of the dorsal striatum and acute nicotine dependence in terms of pathophysiology and behavior.

Third, the anxiety-like behavior in the elevated plus maze was assessed at 2 days after acute nicotine dependence, while other behaviors were mainly conducted on 4–5 days after acute nicotine dependence. The behavioral changes observed on day 2 could be different from the ones observed on days 4–5. This is due to the effect of “incubation”. Eysenick’s theory of incubation65 posits that, through various biological mechanisms, a symptom can emerge/worsen after time has elapsed following the experience of disease risk factor(s). This “incubation” is the opponent process of the traditionally observed “extinction”, in which the symptom dissipates as time passes. In our previous work7 and in this study, we found that anxiety-like behavior in the elevated plus maze was not significantly altered immediately or 2 days after acute nicotine dependence. These findings indicate that the anxiety-like behavior could be in the “incubation” stage and may emerge at a later time point of acute nicotine dependence, as observed with passive avoidance. However, a simpler explanation is that anxiety-like behavior is not a hallmark of acute nicotine dependence, unlike chronic nicotine dependence. Further studies are warranted to clarify the protracted effect of acute nicotine dependence on anxiety and the potential existence of interaction between acute nicotine dependence-induced inhibitory avoidance and anxiety.

Lastly, another limitation to this study is the lack of validation in animal modeling. In our previous study, acute nicotine dependence was marked by the characteristic emergence of somatic signs and locomotor depression immediately after the pharmacological induction of nicotine withdrawal7. Although the existence of acute nicotine dependence has been proven in various studies2–6,9,10,15, whether the short-term low-dose nicotine can induce acute dependence in mice should to be established further in future studies.

Summary

In this study, we demonstrated that the protracted phase of acute nicotine dependence is characterized by passive avoidance deficit, dysregulation of miR-27b/Marcks pathway in the dorsal striatum, and impairments in striatal neural plasticity. The array of experimental evidence indicates that acute nicotine dependence causes multiple protracted symptoms that should not be neglected. Moreover, the clear manifestation of protracted signs from acute nicotine dependence suggests that a therapeutic intervention might aid in improving the quality of life among the people attempting to quit cigarette smoking.

Materials and methods

Animals

7-weeks-old male C57BL/6N mice were purchased one week before modeling (Daehan Bio Link, Daejeon, Republic of Korea). Mice were housed in groups of 3~4 within plastic cages with metal grids and were maintained under a 12-hour reversed light-dark cycle (light-off at 7:00 AM). Mice had ad libitum access to food and drinking water throughout experimentation. All mice were assigned randomly to each group.

All procedures regarding the handling and use of animals in this study were conducted as approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the Korea Institute of Science and Technology (KIST). We have complied with all relevant ethical regulations for animal use.

Mouse model of acute nicotine dependence

The mouse model of acute nicotine dependence was produced as previously described7. (-)-Nicotine ditartrate (Tocris Bioscience, Abindgon, UK) was dissolved in physiological saline. Mecamylamine hydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved in physiological saline. Mice were injected with the nicotine solution (0.5 mg/kg, 10 ml/kg, i.p.) once daily for three days, and then were injected with the mecamylamine solution (3.0 mg/kg, 10 ml/kg, i.p.) 24 hours after the last nicotine injection to precipitate nicotine withdrawal.

Behaviors

Mice were handled to the experimenter for three days (10 min/day) prior to behavioral assays. The behavioral assays were video-recorded for manual analysis using a stopwatch. Each behavioral test was performed with an independent batch of animals. All behavioral tests commenced 10 minutes after the last injection of saline or mecamylamine solution. All experiments were replicated at least once.

An elevated plus maze test was conducted 2 days after the precipitation of nicotine withdrawal. A passive avoidance test was conducted at 4~5 days after precipitation of nicotine withdrawal. The same mice were used for the elevated plus maze and passive avoidance experiments. Spatial object recognition was conducted with separate animals at 4~5 days after precipitation of nicotine withdrawal. Social interaction tests and somatic withdrawal sign measurements were conducted with separate animals at 5 days after precipitation of nicotine withdrawal. The overall experimental timeline is depicted in Fig. S1.

Elevated plus maze

Elevated plus maze test was performed to measure anxiety-like behavior as described previously7,66. The apparatus consisted of an elevated maze with two white open arms and two black closed arms. Each arm consisted of 10 cm × 40 cm dimensions. The closed arms were surrounded by 18-cm-high black walls. The center zone of the maze was maintained at 5 lux. The maze was elevated 50 cm above the ground. Mice were placed facing the end of a closed arm and allowed to freely explore the maze for 5 min. The time spent in open arms, closed arms, or center zone were analyzed manually using a stopwatch. An entry was defined as the mouse having three paws into an arm or the center zone of the maze.

Passive avoidance test

Passive avoidance test was performed to measure fear memory as described previously7,66. A two-chambered foot-shock apparatus was used (Jeungdo Bio & Plant Co., Seoul, Republic of Korea). The apparatus consisted of light and dark chambers separated by a gate. Mice were placed in the light chamber for 1 min, and the gate was opened. When mice entered the dark chamber, the gate was immediately closed and an electric foot-shock (0.4 mV, 2 seconds) was delivered through the floor grid. Mice were left in the dark chamber for an additional 1 min and then returned to their home cages. 24 hours later, mice were again placed in the light chamber for 1 min, and the gate was opened. Mice were allowed to freely explore the light and dark chambers for 10 min without electric foot-shock. The latency to enter the dark chamber, the time spent in the dark chamber, and the number of entries into the dark chamber were manually analyzed. An entry was defined as the mouse having all four paws in a chamber.

Spatial object recognition test

Spatial object recognition test was conducted to measure spatial recognition memory as described previously7,67. An open field box with 40 cm × 40 cm x 40 cm inner dimensions, two identical objects (blue glossy cylinders) consisting of 7 cm height and 4 cm radius, and a visual cue consisting of 18 cm × 24 cm dimensions with a checkered pattern of 2 cm × 2 cm dimensions were used for the test. The visual cue was attached to one wall of the open field box. The open field was maintained at ~5 lux. During training, the two identical objects were placed at the corner of the open field, 8 cm away from each wall, near the visual cue-attached wall. During recall (24 hours after training), one of the two identical objects was moved perpendicularly from its original position and to the opposite wall of the visual cue-attached wall.

During training and recall, mice were placed in the open field box facing the opposite wall of the visual cue-attached wall, and allowed to freely explore the box and the objects for 10 min. The time spent sniffing each object was manually analyzed using a stopwatch, and the recognition index was calculated as defined previously7,68.

Social interaction test

Social interaction test was conducted to measure social behavior as previously described69. The open field box and a cylindrical stainless steel cage consisting of 15 cm height and 5 cm radius were used for the test. The cage was placed right close to one wall of the open field box, in the central position.

During each session, mice were placed in the open field box facing the opposite wall of the wall with the stainless steel cage, and allowed to freely explore the box and the steel cage for 15 min. During the first session, the cage remained empty. During the next session, a conspecific weighing ~90% of the experimental mice’s body weight was confined in the cage. The two sessions were carried out consecutively. Between the two sessions, the experimental mice were kept in a holding cage similar to their home cages.

The time spent sniffing the empty cage or the social conspecific was analyzed manually, and the social interaction ratio was calculated as defined previously7,69.

Somatic withdrawal signs

Somatic signs of nicotine withdrawal were measured as previously reported7. A clear plexiglass column with 7 × 7 x 30 inner dimension and openings at the top and bottom was used for measurement of the somatic signs. The floor luminosity was maintained at 100 lux. Mice were confined in the plexiglass column for 30 min to allow for a close-up video-examination of paw and body movements. The last 20 min of the video recording was analysed for the measurement of somatic signs.

The number of events were counted for each sign. Paw tremors were defined as rapidly shaking paw(s) for two times while the two paws are supported on the ground or columnar wall, or three times while three paws are in support (paw movement frequency >10 Hz, amplitude (peak-to-peak) >5 mm as defined previously70). Body shakes were defined as wet-dog shakes, which are rapidly shaking the body with the anteroposterior axis as the axis of rotation (body shaking frequency ~30 Hz as defined previously71).

Brain sampling and cryosection

For small RNA sequencing and qPCR, either at one day (for qPCR in Fig. 4A) or one week after induction of acute nicotine dependence, mice were deeply anesthetized by intraperitoneal administration of 250 mg/kg Avertin (2,2,2-tribromoethanol) (Sigma-Aldrich). The whole brain was quickly isolated, frozen in dry ice and stored at −80 °C. The frozen brains were coronally sectioned on a cryostat (CM3050S; Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) to a thickness of 150 μm at −20 °C and then further micro-dissected with a cold surgical micro-knife to isolate the dorsal striatum.

For immunohistochemistry, at one week after induction of acute nicotine dependence, mice were deeply anesthetized with Avertin, then transcardial perfusion was performed with 1x PBS followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) (Sigma-Aldrich) in 1x PBS. The whole brain was isolated and post-fixed in 4% PFA for overnight at 4 °C. The fixed brains were then dehydrated with 30% sucrose until submersion, embedded in OCT compound, and stored at −80 °C. The fixed, OCT-embedded brains were coronally sectioned on a cryostat to a thickness of 20 μm at −20 °C.

RNA isolation

Total RNA from the frozen, dissected dorsal striatum was isolated using Trizol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. NanoDrop 2000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used to determine RNA yield and quality. RNA samples with low A260/A230 ratio (<1.0) were not used for the downstream experiments.

Small RNA sequencing

The dorsal striatum from 3 mice was combined to generate one sample (n) for small RNA sequencing (total 9 mice used per group). cDNA libraries were constructed via TruSeq Small RNA Library Prep Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA), and small RNA sequencing was conducted by Macrogen (Seoul, Republic of Korea). Raw data in FASTQ format was obtained and preprocessed for read count normalization with DESeq2 method72 and sample distribution analyses through sRNAbench server33. DESeq2-normalized read counts were used for heat map generation and hierarchical clustering analysis via Morpheus server36.

miRNA targetome analysis

TargetScan v8.0 and DIANA microT-CDS were used to predict the gene targets of miRNA38,73. For TargetScan, genes that were (1) commonly found in both TargetScanHuman and TargetScanMouse, (2) with cumulative weighted context + + score (CWCS + +) < −0.35, and (3) aggregate PCT > 0.75 were selected as putative targets. For microT-CDS, genes that were (1) commonly found as the target of hsa-miR-27b-3p and mmu-miR-27b-3p, and (2) with miTG score > 0.85 were selected as putative targets.

The common genes from TargetScan and microT-CDS were defined as miRNA targetome. SynGO and DAVID were used to predict the functions of the miRNA targetome39,40. For SynGO, annotations with -log10(q-value) > 2 were considered significant. For DAVID, functional annotation clusters with enrichment score > 1 were considered significant.

The common genes from the significant annotations in SynGO and DAVID analyses were selected as gene targets for mRNA qPCR.

qPCR

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was conducted to measure miRNA or mRNA in the dorsal striatum, as described previously74. 50 ng of the total RNA from each dorsal striatal sample was used for cDNA preparation through reverse transcription PCR.

For miRNA quantification, cDNA was amplified using TaqMan Universal Master Mix II, no UNG (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The expression of mature miR-27b-3p was quantified using qPCR with TaqMan MicroRNA Assays (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

For mRNA quantification, cDNA was amplified using ReverTra Ace™ qPCR RT Master Mix with gDNA Remover (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The expression of each mRNA was quantified using qPCR with iQ™ SYBR® Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For mRNA qPCR, primers were designed in-house and obtained from Bioneer, Inc. (Daejeon, South Korea). The sequences of primer sets used for mRNA qPCR are provided in Table S4.

qPCR reactions were run on CFX connect (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). All reactions were performed in triplicates. The relative abundance of miRNA and mRNAs was calculated by 2–ddCt method75. snoRNA202 or GAPDH was used as a normalization control for brain miRNA or mRNA quantification in mice, respectively. In the CFX Manager Software, the PCR efficiency confirmed to be at least >90% for all reactions with different amplicons.

Luciferase assay

Luciferase assay was conducted as described previously74. Mouse miRNA 3’UTR target clone Marcks (MmiT027592-MT05; GeneCopoeia, Rockville, MD, USA), Mir27b Mouse MicroRNA Expression Plasmid (MI0000142; OriGene, Rockville, MD, USA), and appropriate control vectors were used for the luciferase assay. Briefly, wild-type Marcks-3′UTR or mutant Marcks-3′UTR vector was transfected together with miR-27b overexpression vector or scrambled control vector to HEK293TN cells in a 24-well cell culture plate using Lipofectamine 3000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Total 500 ng of DNA vectors was transfected per well, and the ratio of miRNA expression vector to the 3′UTR clone vector was 9:1. Media was changed 16 hours after transfection, and collected 40 hours after transfection.

Gaussia luciferase activity was normalized to the activity of secreted alkaline phosphatase using Secrete-Pair Dual Luminescence Assay Kit (GeneCopoeia) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Each enzyme’s activity was quantified with Synergy HTX Multi-Mode Microplate Reader (BioTek, VT, USA).

miRNA fluorescence in situ hybridization

miRNA fluorescence in situ hybridization was performed as described previously76. Briefly, the fixed brain sections (20 μm) were washed in DEPC-PBS, incubated in TNT buffer, and incubated with proteinase K at 37 °C for 5 min. Next, the sections were treated with acetylation buffer at RT for 10 min, and incubated in hybridization buffer at 25 °C below the LNA probe’s Tm for 30 min. Then, the sections were incubated in hybridization buffer containing 50 nM of 5’-digoxigenin(DIG)-labeled LNA probe (Exiqon, Vedbæk, Denmark) overnight. Then, the sections were washed in SSC buffer, and treated with 3% hydrogen peroxide at RT for 30 min. Thereafter, the sections were incubated with blocking buffer at RT for 1 hour, and incubated with sheep anti-DIG-POD Fab fragments (1:200) (Sigma-Aldrich) in blocking buffer at RT for 1 hour.

The miRNA fluorescence signal was amplified using Alexa Fluor™ 594 Tyramide SuperBoost™ Kit, streptavidin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manusfacturer’s protocol. The sections were incubated in Tyramide SuperBoost (TSB) solution for 5 min. The sections were mounted with Vectashield HardSet Antifade Mounting Medium with DAPI (Vector Laboratories, CA, USA). Fluorescence images were taken with EVOS M7000 Imaging System (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical staining (IHC) was performed as described previously74. For Marcks and Drd2 IHC, the fixed brain sections (20 μm) were washed in 1x PBS, followed by 0.1% Tween-20 in 1x PBS (PBST). The washed sections underwent heat-induced antigen retrieval with sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) at 65 °C for 10 min. Then the sections were blocked with 10% normal donkey serum (NDS) in PBST for 1 hour, and incubated with rabbit anti-MARCKS (1:400) (AB9298; Sigma-Aldrich) and mouse anti-DRD2 (1:100) (sc-5303; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) in 2% NDS for 48 hours at 4 °C. Subsequently, the sections were washed and incubated with donkey anti-rabbit IgG Alexa Fluor 488 (1:400) (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and donkey anti-mouse IgG Alexa Fluor 594 (1:400) for 2 hours at RT. Lastly, the sections were mounted with Vectashield HardSet Antifade Mounting Medium with DAPI (Vector Laboratories, CA, USA).

To visualize F-actin, phalloidin IHC was performed as described previously77. Briefly, the fixed brain sections were washed in 1x PBS, underwent heat-induced antigen retrieval, blocked with 10% NDS, and incubated with Alexa Fluor 594 Phalloidin (1:200) (A12381; Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 48 hours at 4 °C. The sections were mounted with Vectashield HardSet Antifade Mounting Medium (Vector Laboratories).

Fluorescence images were taken with EVOS M7000 Imaging System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Corrected total cell fluorescence (CTCF) was calculated using ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) as previously defined78: CTCF = Integrated Density – (Area of selected cell x Mean fluorescence of background readings).

Golgi-Cox staining

Golgi-Cox staining was performed to visualize dendritic spines as described previously79,80, with minor modifications. At one week after induction of acute nicotine dependence, Mice were deeply anesthetized by Avertin, transcardially perfused with 1x PB, and subsequently perfused with 0.1% PFA + 0.5% glutaraldehyde in 1x PB. The whole brain was isolated and stored in 0.1% PFA + 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 1x PB for 30 min at 4 °C.

The whole brain was then incubated in 0.45-μm filtered Golgi-Cox solution in a glass bottle, protected from light, for 14 days at RT. The Golgi-Cox solution was changed daily. The Golgi-impregnated brain was submerged in 30% sucrose solution containing 1% PVP-40 and 30% ethylene glycol in 1x PB for 4 days at 4 °C. The 30% sucrose solution was changed daily.

The submerged brain was embedded in 4% agarose (45–50 °C), and allowed to harden at 4 °C overnight. The embedded brain was sectioned with a vibratome (VT1000 S, Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany) to a thickness of 150 μm at RT in 30% sucrose solution in 1x PB. Vibratome sectioning speed was 0.12 mm/s and amplitude was 0.40 mm.

The brain sections were washed with distilled water, passed in 0.5X Kodak Developer solution for 10 min, fixed in 0.5X Kodak Fixer solution for 10 min, and incubated in 0.1 M glycine in 1X PB. Then the sections were mounted on a gelatin-coated slide, air-dried until attached (~10 min), and passed through ethanol at concentrations of 70%, 95% 100%, and 100% for 2 min each. Lastly, the slide-mounted sections were incubated in xylene for 20 min, and immediately mounted with a xylene-permount mixture (1:1). Dendritic spine images were taken with EVOS M7000 Imaging System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The number of dendritic spines were counted manually as in previous studies81,82.

Multi-electrode array recording

Multi-electrode array (MEA) recording was performed to examine neural activity in brain slices ex vivo as described previously31, with modifications. Mice were deeply anesthetized with Avertin, and transcardially perfused with ice-cold oxygenated “NMDG-ACSF” composed of (in mM) 92 NMDG, 25 glucose, 5 Na L-ascorbate, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 2 thiourea, 10 MgCl2, 30 NaHCO3, 20 HEPES, 3 Na pyruvate, and 0.5 CaCl2 at pH 7.4. Coronal brain slices (300 mm thickness) containing the dorsal striatum were acutely isolated using a vibratome (Leica Biosystems). Next, the brain slices were incubated in oxygenated NMDG-ACSF at 34 °C for 30 min, followed by incubation in oxygenated “Standard ACSF” composed of (in mM) 92 NaCl, 25 glucose, 5 Na L-ascorbate, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 2 thiourea, 2 MgCl2, 30 NaHCO3, 20 HEPES, 3 Na pyruvate, and 2 CaCl2 at pH 7.4 at RT for 60 min prior to MEA recording. “Recording ACSF” composed of (in mM) 124 NaCl, 12.5 glucose, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 2 MgCl2, 24 NaHCO3, 20 HEPES, and 2 CaCl2 at pH 7.4 was used during MEA recording.

MEA recording was conducted using Maestro Edge MEA System (Axion Biosystems, GA, USA) and CytoView MEA 6 (Axion Biosystems). Recording chamber was set at 32 °C and continuously aerated with carbogen. Data acquisition and electrical stimulation were performed through AxIS Navigator (Axion Biosystems). An electrical stimulation session consisted of 8 blocks with 30-s inter-block interval, 30 pulses/block with 1-s inter-pulse interval, and each pulse consisting of a biphasic waveform lasting 250 μs. Step increase in the electrical stimulation intensity was applied from block to block, from 125 to 1000 nA.

For the analysis of neural population spikes, the acquired data were post-processed through AxionDataExportTool (Axion Biosystems) and Offline Sorter V4 (Plexon, TX, USA). The number of electrically-evoked neural population spikes were counted in each of the four recording sites immediately near the stimulation electrode. Recording sites with stimulation-response fidelity <10% (spikes evoked in less than 10% of all stimulation events) were excluded from analysis.

For the analysis of local field potential (LFP), the acquired data were post-processed through MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA) as described previously 24, with modifications. The obtained data was bandpass-filtered at 0.5–200 Hz. A single 10-s epoch of the local field potential data was obtained immediately before the electrical stimulation session. For normalized quantification of power spectral density (PSD) in the LFP, the frequency bands of delta (1–4 Hz), theta (4–8 Hz), alpha (8–12 Hz), beta (12–30 Hz), low-gamma (30–55 Hz), and high-gamma (65–90 Hz) were separately analyzed. Sample entropy in the LFP was quantified to measure the nonlinear irregularity or complexity of a signal as described previously.

Statistics and reproducibility

The experimenter was not blinded to the experimental conditions during behavioral recording and analysis, but all animals were randomly assigned into control or treatment groups and all experiments were replicated at least once. Replication attempts were successful and observed measurements were consistent.

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), two-way ANOVA, two-way repeated measures (RM) ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s, Fisher LSD, or two-stage linear step-up procedure of Benjamini, Krieger and Yekutieli post-hoc analysis, or Student’s t-test was conducted as appropriate. For small RNA sequencing, false discovery rate (FDR)-adjusted multiple t-test (q-value = 1%) was used to identify significantly altered miRNAs.

p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The exact number of animals/samples used, p values, F values, degrees of freedom (df), and t values were provided in the results. Data were displayed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

Statistical analyses were done with Prism v10.0 (GraphPad, CA, USA).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (2020R1A2C2004610, 2022R1A6A3A01087565; Republic of Korea), and the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (MFDS) grant by the Korean government (RS-2024-00332024; Republic of Korea).

Author contributions

B.K.: project administration, conceptualization, methodology, funding acquisition, investigation, validation, visualization, formal analysis, data curation, writing-original draft, and writing-review & editing. H.-I.I.: supervision, project administration, conceptualization, funding acquisition, resources, writing-original draft, and writing-review & editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Ana Domi, Vladimir Vladimirov and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Christoph Anacker and Christina Karlsson Rosenthal. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

All the datasets supporting the findings of the current study are available in the article and supplementary materials. Source data generated in this study will be shared from the corresponding author upon request. The miRNA sequencing data have been deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database under the following accession code: GSE280738. The source data behind the graphs in the paper can be found in Supplementary Data 1.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Inclusion & Ethics

Authors have committed to upholding the principles of research inclusion & ethics as advocated by the Nature Portfolio.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s42003-024-07207-0.

References

- 1.Benowitz, N. L. Nicotine addiction. N. Engl. J. Med.362, 2295–2303 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harris, A. C., Manbeck, K. E., Schmidt, C. E. & Shelley, D. Mecamylamine elicits withdrawal-like signs in rats following a single dose of nicotine. Psychopharmacology225, 291–302 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morrison, C. F. Effects of nicotine and its withdrawal on the performance of rats on signalled and unsignalled avoidance schedules. Psychopharmacologia38, 25–35 (1974). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harris, A. C. Further pharmacological characterization of a preclinical model of the early development of nicotine withdrawal. Drug Alcohol Depend.226, 108870 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muelken, P., Schmidt, C. E., Shelley, D., Tally, L. & Harris, A. C. A two-day continuous nicotine infusion is sufficient to demonstrate nicotine withdrawal in rats as measured using intracranial self-stimulation. PLoS One10, e0144553 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vann, R. E., Balster, R. L. & Beardsley, P. M. Dose, duration, and pattern of nicotine administration as determinants of behavioral dependence in rats. Psychopharmacology184, 482–493 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim, B. & Im, H.-I. Behavioral characterization of early nicotine withdrawal in the mouse: a potential model of acute dependence. Behav. Brain Funct.20, 1 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Schwab, M. Encyclopedia of cancer. Springer Science & Business Media (2008).

- 9.DiFranza, J. R. A 2015 update on the natural history and diagnosis of nicotine addiction. Curr. Pediatr. Rev.11, 43–55 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DiFranza, J. R. Thwarting science by protecting the received wisdom on tobacco addiction from the scientific method. Harm Reduct. J.7, 1–12 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris, A. C. & Gewirtz, J. C. Acute opioid dependence: characterizing the early adaptations underlying drug withdrawal. Psychopharmacology178, 353–366 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bickel, W. K., Stitzer, M. L., Liebson, I. A. & Bigelow, G. E. Acute physical dependence in man: effects of naloxone after brief morphine exposure. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther.244, 126–132 (1988). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin, W. & Eades, C. A comparison between acute and chronic physical dependence in the chronic spinal dog. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther.146, 385–394 (1964). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koob, G. F. & Le Moal, M. Drug abuse: hedonic homeostatic dysregulation. Science278, 52–58 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Damaj, M., Welch, S. & Martin, B. Characterization and modulation of acute tolerance to nicotine in mice. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther.277, 454–461 (1996). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koob, G. F. Neurobiology of addiction: Toward the development of new therapies. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci.909, 170–185 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pereira-da-Silva, T. et al. Cigarette smoking, miR-27b downregulation, and peripheral artery disease: Insights into the mechanisms of smoking toxicity. J. Clin. Med.10, 890 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen, Z. et al. miRNAomics analysis reveals the promoting effects of cigarette smoke extract-treated Beas-2B-derived exosomes on macrophage polarization. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.572, 157–163 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poon, V. Y., Gu, M., Ji, F., VanDongen, A. M. & Fivaz, M. miR-27b shapes the presynaptic transcriptome and influences neurotransmission by silencing the polycomb group protein Bmi1. BMC Genom.17, 1–14 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moreau, M. P., Bruse, S. E., David-Rus, R., Buyske, S. & Brzustowicz, L. M. Altered microRNA expression profiles in postmortem brain samples from individuals with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Biol. Psychiatry69, 188–193 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Isola, R., Zhang, H., Tejwani, G. A., Neff, N. H. & Hadjiconstantinou, M. Dynorphin and prodynorphin mRNA changes in the striatum during nicotine withdrawal. Synapse62, 448–455 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lagström, O., Vestin, E., Söderpalm, B., Ericson, M. & Adermark, L. Subregion specific neuroadaptations in the female rat striatum during acute and protracted withdrawal from nicotine. J. Neural Transm.131, 83–94 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adermark, L. et al. Temporal rewiring of striatal circuits initiated by nicotine. Neuropsychopharmacology41, 3051–3059 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim, B. & Im, H. I. Chronic nicotine impairs sparse motor learning via striatal fast‐spiking parvalbumin interneurons. Addict. Biol.26, e12956 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cippitelli, A. et al. Endocannabinoid regulation of acute and protracted nicotine withdrawal: effect of FAAH inhibition. PLoS one6, e28142 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Damaj, M. I., Kao, W. & Martin, B. R. Characterization of spontaneous and precipitated nicotine withdrawal in the mouse. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther.307, 526–534 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kwilasz, A. J., Harris, L. S. & Vann, R. E. Removal of continuous nicotine infusion produces somatic but not behavioral signs of withdrawal in mice. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav.94, 114–118 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.American Psychological Association (APA). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR®). American Psychological Association (2022).

- 29.LeBlanc, K. H. et al. Striatopallidal neurons control avoidance behavior in exploratory tasks. Mol. Psychiatry25, 491–505 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Loewke, A. C., Minerva, A. R., Nelson, A. B., Kreitzer, A. C. & Gunaydin, L. A. Frontostriatal projections regulate innate avoidance behavior. J. Neurosci.41, 5487–5501 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee, S. et al. Dysfunction of striatal MeCP2 is associated with cognitive decline in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Theranostics12, 1404–1418 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim, V. N., Han, J. & Siomi, M. C. Biogenesis of small RNAs in animals. Nat. Rev. Mol. cell Biol.10, 126–139 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aparicio-Puerta, E. et al. sRNAbench and sRNAtoolbox 2022 update: accurate miRNA and sncRNA profiling for model and non-model organisms. Nucleic Acids Res.50, W710–W717 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu, C. et al. Elucidation of the small RNA component of the transcriptome. Science309, 1567–1569 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gowen, A. M. et al. Role of microRNAs in the pathophysiology of addiction. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA12, e1637 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Broad Institute. Morpheus. https://software.broadinstitute.org/morpheus.

- 37.McGeary, S. E. et al. The biochemical basis of microRNA targeting efficacy. Science366, eaav1741 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paraskevopoulou, M. D. et al. DIANA-microT web server v5.0: service integration into miRNA functional analysis workflows. Nucleic Acids Res.41, W169–W173 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koopmans, F. et al. SynGO: an evidence-based, expert-curated knowledge base for the synapse. Neuron103, 217–234.e214 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sherman, B. T. et al. DAVID: a web server for functional enrichment analysis and functional annotation of gene lists (2021 update). Nucleic Acids Res.50, W216–W221 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buccitelli, C. & Selbach, M. mRNAs, proteins and the emerging principles of gene expression control. Nat. Rev. Genet.21, 630–644 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maier, T., Güell, M. & Serrano, L. Correlation of mRNA and protein in complex biological samples. FEBS Lett.583, 3966–3973 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Everitt, B. J. & Robbins, T. W. Neural systems of reinforcement for drug addiction: from actions to habits to compulsion. Nat. Neurosci.8, 1481–1489 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.El Amri, M., Fitzgerald, U. & Schlosser, G. MARCKS and MARCKS-like proteins in development and regeneration. J. Biomed. Sci.25, 1–12 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brudvig, J. J. & Weimer, J. M. X MARCKS the spot: myristoylated alanine-rich C kinase substrate in neuronal function and disease. Front. Cell. Neurosci.9, 407 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hartwig, J. et al. MARCKS is an actin filament crosslinking protein regulated by protein kinase C and calcium–calmodulin. Nature356, 618–622 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grover, C., Sturgill, D. & Goldman, L. Post–acute Withdrawal Syndrome. J. Addict. Med.17, 219–221 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baker, T. B., Japuntich, S. J., Hogle, J. M., McCarthy, D. E. & Curtin, J. J. Pharmacologic and behavioral withdrawal from addictive drugs. Curr. Direct. Psychol. Sci.15, 232–236 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Koob, G. F. & Le, MoalM. Drug addiction, dysregulation of reward, and allostasis. Neuropsychopharmacology24, 97–129 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kern, F. et al. What’s the target: understanding two decades of in silico microRNA-target prediction. Brief. Bioinforma.21, 1999–2010 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Monga, I. & Kumar, M. Computational resources for prediction and analysis of functional miRNA and their targetome. Comput. Biol. Non-Coding RNA: Methods Protocols1912, 215–250 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Singer, M. et al. A MARCKS-related peptide blocks mucus hypersecretion in a mouse model of asthma. Nat. Med.10, 193–196 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Agrawal, A., Singh, S. K., Singh, V. P., Murphy, E. & Parikh, I. Partitioning of nasal and pulmonary resistance changes during noninvasive plethysmography in mice. J. Appl. Physiol.105, 1975–1979 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Safiejko-Mroczka, B. & Bell, P. B. Jr. Bifunctional protein cross-linking reagents improve labeling of cytoskeletal proteins for qualitative and quantitative fluorescence microscopy. J. Histochem. Cytochem.44, 641–656 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hotulainen, P. & Hoogenraad, C. C. Actin in dendritic spines: connecting dynamics to function. J. Cell Biol.189, 619–629 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Licheri, V., Eckernäs, D., Bergquist, F., Ericson, M. & Adermark, L. Nicotine‐induced neuroplasticity in striatum is subregion‐specific and reversed by motor training on the rotarod. Addict. Biol.25, e12757 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Matta, S. G. et al. Guidelines on nicotine dose selection for in vivo research. Psychopharmacology190, 269–319 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu, Y., Roberts, D. C. & Morgan, D. Sensitization of the reinforcing effects of self‐administered cocaine in rats: effects of dose and intravenous injection speed. Eur. J. Neurosci.22, 195–200 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sorge, R. E. & Clarke, P. B. Rats self-administer intravenous nicotine delivered in a novel smoking-relevant procedure: effects of dopamine antagonists. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther.330, 633–640 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cohen, A. & George, O. Animal models of nicotine exposure: relevance to second-hand smoking, electronic cigarette use, and compulsive smoking. Front. Psychiatry4, 41 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Horowitz, M. A. & Taylor, D. Addiction and physical dependence are not the same thing. Lancet Psychiatry10, e23 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chellian, R. et al. Rodent models for nicotine withdrawal. J. Psychopharmacol.35, 1169–1187 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Madden, P. A. et al. Nicotine withdrawal in women. Addiction92, 889–902 (1997). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jackson, K., Muldoon, P., De Biasi, M. & Damaj, M. New mechanisms and perspectives in nicotine withdrawal. Neuropharmacology96, 223–234 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Eysenck, H. J. A theory of the incubation of anxiety/fear responses. Behav. Res. Ther.6, 309–321 (1968). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tag, S. H., Kim, B., Bae, J., Chang, K.-A. & Im, H.-I. Neuropathological and behavioral features of an APP/PS1/MAPT (6xTg) transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Brain15, 51 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kenney, J. W., Adoff, M. D., Wilkinson, D. S. & Gould, T. J. The effects of acute, chronic, and withdrawal from chronic nicotine on novel and spatial object recognition in male C57BL/6J mice. Psychopharmacology217, 353–365 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Antunes, M. & Biala, G. The novel object recognition memory: neurobiology, test procedure, and its modifications. Cogn. Process.13, 93–110 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Golden, S. A., Covington, I. I. I., HE, Berton, O. & Russo, S. J. A standardized protocol for repeated social defeat stress in mice. Nat. Protoc.6, 1183–1191 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kuo, S.-H. et al. Current opinions and consensus for studying tremor in animal models. Cerebellum18, 1036–1063 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dickerson, A. K., Mills, Z. G. & Hu, D. L. Wet mammals shake at tuned frequencies to dry. J. R. Soc. Interface9, 3208–3218 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol.15, 1–21 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Agarwal, V., Bell, G. W., Nam, J. W. & Bartel, D. P. Predicting effective microRNA target sites in mammalian mRNAs. eLife4, e05005 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kim, B. et al. SYNCRIP controls miR-137 and striatal learning in animal models of methamphetamine abstinence. Acta Pharm. Sin. B12, 3281–3297 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔCT method. Methods25, 402–408 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Silahtaroglu, A. Fluorescence in situ hybridization for detection of small RNAs on frozen tissue sections. In Situ Hybridization Protocols1211, 95–102 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 77.Lee, S. H. et al. Haploinsufficiency of Cyfip2 causes lithium‐responsive prefrontal dysfunction. Ann. Neurol.88, 526–543 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hammond, L. Measuring cell fluorescence using ImageJ. Open Lab Book1, 50–53 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zaqout, S. & Kaindl, A. M. Golgi-Cox staining step by step. Front. Neuroanat.10, 38 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bayram-Weston, Z., Olsen, E., Harrison, D. J., Dunnett, S. B. & Brooks, S. P. Optimising Golgi–Cox staining for use with perfusion-fixed brain tissue validated in the zQ175 mouse model of Huntington’s disease. J. Neurosci. Methods265, 81–88 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mahmmoud, R. R. et al. Spatial and working memory is linked to spine density and mushroom spines. PLoS one10, e0139739 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gu, J., Firestein, B. L. & Zheng, J. Q. Microtubules in dendritic spine development. J. Neurosci.28, 12120–12124 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

All the datasets supporting the findings of the current study are available in the article and supplementary materials. Source data generated in this study will be shared from the corresponding author upon request. The miRNA sequencing data have been deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database under the following accession code: GSE280738. The source data behind the graphs in the paper can be found in Supplementary Data 1.