Abstract

Marine heatwaves (MHW) pose an increasing threat and have a critical impact on meroplanktonic organisms, because their larvae are highly sensitive to environmental stress and key for species’ dispersion and population connectivity. This study assesses the effects of MHW on two key moulting cycle periods within first zoea of the valuable crab, Metacarcinus edwardsii. First, the changes in swimming behaviour during zoea I were recorded and associated to moult cycle substages. Then, larvae were exposed during the zoea I to (1) control temperature of 12 °C, (2) Early MHW, occurring in intermoult, (3) Late MHW, occurring in premoult and (4) 14 °C, representing MHW during whole development. Additionally, optimum temperature was estimated from thermal performance curves through swimming behaviour of one-day zoea I. The timing of the MHW within the moulting cycle significantly affects larval fitness. Early MHW led to improved survival rates (72%) and reduced developmental times (9.8 days) compared to those exposed to Later MHW (63% and 10.3 days, respectively). As optimum temperature was higher than 12 °C, MHW events maybe favouring larval performance. These results highlight the importance of interaction between the moult cycle and environmental variables as a factor of sublethal effects on population dynamics.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-81258-5.

Subject terms: Ecology, Behavioural ecology, Climate-change ecology

Introduction

Marine heatwaves (MHW) are define as anomalously warm water lasting at least five days in which the sea surface temperature exceeds a threshold determined by the high percentile (90th-99th percentile) of the 30-year climatology of the location at a given time of the year1. These extreme events like MHW are an emerging issue in marine biology due to their direct and indirect impacts on marine life shaping the performance, survival, and its distribution2–4. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (2019)5 presents several pathway models for MHW, which become more frequent, intense and extensive in time and geography in each projection. In the best-case scenario, the annual probability of a MHW event increases by a factor of 16–24, a prediction that doubles in the worst-case scenario, with projected global intensities of around 3.1–3.8 °C by the 2080–2100 period (RCP 8.5)5.

Temperature is the most influential physical factor in oceans, directly affecting organisms’ biochemical and physiological processes, operating across various spatial and temporal scales6, so the vulnerability of marine organisms to MHW is challenging to predict. Thermal sensitivity experiments use different constant temperature regimes to determine their effects on organisms, but thermal stress in the environment fluctuates daily, and the potential presence of a MHW event adds acute thermal stress to individuals that may exceed species-specific thermal tolerance limits or physiological endpoints7–9. As marine organisms appear to be more vulnerable to climatic extremes than to gradual increases in mean temperature, conceptual thermal thresholds have recently been widely applied to ectotherms10. The thermal biology of ectotherms is described in terms of parameters such as thermal performance11, which varies between life cycle stages12,13.

Early ontogenetic stages appear to be the most sensitive to environmental conditions14–18. In fact, early stages such as embryos, larvae or juveniles tend to be more sensitive to environmental conditions due to their constant processes of organogenesis and growth14. The rate of cell division involved in early developmental timing events is strongly influenced by temperature, which could be described by fitting the Arrhenius equation19. Therefore, as the environmental temperature increases, so does the acceleration of ectotherm development20. This fact undoubtedly leads to an increase in energy requirements, resulting in sublethal effects up to death21. However, the catalytic effect driven by temperature could be just an additional stress to the own sensitivity of the developmental period that the organisms are going through22,23 and the magnitude of the thermal stress effect could be state-conditioned.

Crustacean decapods exhibit a diverse range of developmental patterns, including a distinctive moult cycle. During larval development, this cycle is characterised by a significant shift in morphology and functional requirements, which occurs in a compartmentalised manner within each stage16. The moulting cycle substages are composed principally of a postmoult (A-B), intermoult (C), premoult (D₀-D₄) and ecdysis (E) (as described by Drach, 193924) generated by itself described variation of energy requirements, ecdysone production or tegument composition. Therefore, depending on the specific period during the moulting cycle in which an environmental stressor occurs (i.e. variations in temperature, salinity, food availability), it may exert a harder effect on larval development25,26. A potential critical window was identified as the transition from the intermoult to the premoult stage, referred to as the “D₀ threshold”23. This period requires the organism to be nutritionally and hormonally prepared for the onset of the moult, as larval susceptibility to stress is likely to increase significantly during this time. The bioenergetics performance during the post and intermoult phases (A-C) is superior to that observed during the premoult substage (D phases)25, consequently as active metabolism shows the remaining energy after the basal living expenses27, larval behaviour, and in particular larval movement, should be related with the basal living expenses across their moult cycle. Swimming behaviour was associated to the moulting in the vertical migration of Callinectes sapidus megalopa, that showed a sequence of vertical migration activity at the time of the day, an interval of low activity (premoult), metamorphosis, and then activity at the time of night (when is a Juvenile)28.

Furthermore, meroplanktonic larvae are more susceptible to temperature fluctuations within the water column than benthic adults14,26. The mortality of larvae under acute thermal stress has been documented in certain species. For example, this has been observed in pluteus larvae of sea urchins29 and crab larvae8,30,31. Nevertheless, the lethal impact of MHW on larvae may be uncommon but could be significant in extreme projected scenarios. However, nonlethal effects may drive changes on indispensable capacities for larval success in nature, including migration, prey capture and escape from predators32,33. Conversely, the temperature increase due to a MHW must impact larval developing time (LDT) and could significantly affect population connectivity34. This is because reductions in larval development time may result in reduced larval dispersal, leading to a reduction in genetic flow due to fragmentation34,35. It can be reasonably deduced that MHW has the potential to directly impact the ecosystem’s provisioning service if it affects exploited species. Consequently, estimating the lethal and sublethal effects of MHW in species that support fisheries can assist in developing future management strategies to address the challenges posed by climate change. It can be reasonably deduced that MHW has the potential to directly impact the ecosystem’s provisioning service if it affects exploited species. Consequently, estimating the lethal and sublethal effects of MHW in species that support fisheries can assist in developing future management strategies to address the challenges posed by climate change.

For the Chilean artisanal fishery, the marble crab (Metacarcinus edwardsii) is one of the most valuable crustacean species36. This species is subjected to intensive landing in ports in the southernmost part of its geographic range, primarily on Chiloé Island and in the northern Patagonian fjords (~ 42–44°S). It is the most harvested crab in Chile37. The species appears particularly abundant in estuarine environments, which may function as nursery grounds38. The larval cycle of M. edwardsii is characteristic of the family Cancridae, comprising five zoea stages and one megalopa. The larval development period is approximately 60 days at 13–14 °C39. The impact of temperature stress on survival and development time has yet to be investigated. Genetic analysis suggests that M. edwardsii exhibits a non-structured population with extensive connectivity across 1,700 km of coastline, despite biogeographical barriers34. Consequently, wide range of sea temperatures likely contributes to a breadth species’ thermal niche, which may be a key factor in its successful dispersal across this region40.

This study aims to test the effect of temperature stress triggered by simulated short MHWs at key phases within the crab larval moulting cycle. First, larval activity was used as a daily indicator of the remaining energy during the moult cycle across the first zoea stage, this allowed identify moult substages and timing within the moult cycle. Second, an MHW experiment was performed using local temperature average values to check the effects on the developmental time and survival of the first larvae stage. Finally, to better interpret the results and put them into a regional context, a conceptual thermal optimal niche was performed for the first day after hatching, using changes in swimming behaviour in a thermal ramp to obtain thermal breadth and local optimum of temperature. This novel integrative approach using behavioural traits could enhance our understanding of how an emerging aspect of the future environment may affect crab larvae during their moulting cycle.

Methods

Ovigerous females sampling

Four females of Metacarcinus edwardsii with late-stage embryos were collected in Los Molinos, Valdivia, Chile (39.8°S; 73.4°W) by SCUBA diving in September 2023. They were transported to the coastal laboratory Calfuco (Laboratorio Costero Calfuco) of Universidad Austral de Chile, where the experiments were conducted. The females were maintained in individual 40-litre tanks with a constant seawater flow at a temperature of 11.5 ± 1 °C and feed with mussels (Mytilus chilensis) every other day until they released the larvae. Experiments were conducted under all bioethical standards set forth by the Chilean Government (Law N° 20,380, Animal Protection Statute) and approved by the Chilean Subsecretary of Fishery and Aquaculture (C.I. 12.701) through the submission of a technical report (N°254/2015).

Larval activity across to the moult cycle

Immediately post-hatching, 200 larvae were maintained at 12 °C within a temperature-controlled chamber in four 100 mL vials for twelve days. Eight zoea I larvae from a female brood were randomly selected and placed individually in a plastic multiwell plate with 24 arenas available (one larva per arena, diameter = 16 mm, water volume = 3 ml). The plates were positioned within a Daniovision Observation Chamber (DVOC-0040-t) to record larval behaviour by tracking larval movement using the EthoVision XT software (version 17.0, Noldus Information Technology, The Netherlands). The larvae’s movements were recorded for a period of one hour. To account for the possible effects of light and dark periods on larval swimming behaviour, the experimental period consisted of a 30 min light (10,000 lx) period followed by a 30 min dark period. Thus, if the larvae had any change in phototactic behaviour during the moulting cycle, it would be integrated into a cumulative swimming behaviour during the experimental period. This was regulated automatically by the trial hardware control for the light stimulus of the Daniovision Observation Chamber. This trial was repeated with different larvae until the day of moulting to the second stage (zoea II). To incorporate inter-female variation in progeny quality, the experimental procedure was repeated for larvae from five females. The dependent variables were calculated as the mean distance moved (mm), based on tracking the centre point of each individual.

The accumulated distance moved by larvae during the experimental trial served as an indicator of the cyclic daily remaining energy within the moulting cycle in the first zoea25,27, as it does for vertical migrations in Forward, Diaz & Ogburn (2007). For each day of the moult cycle, the phase of the cycle was identified by observing the condition of the cuticle16,26 in the larval telson (supplementary material). All was done to determine the D₀ threshold.

Thermal performance curve

As previously, the swimming behaviour (i.e. distance recorded and time in movement) for 12 one day old larvae from each female (4 females, 48 larvae in total) was recorded for 5 min every 15 min in absolute darkness, to monitor their performance during a temperature ramp from 12 °C to 30 °C with an increasing rate of approximately 0.04 °C/min, following the recommended rate of 2 °C/h41. Subsequently, the procedure was repeated with an additional 12 larvae from the same females for the decreasing ramp from 12 °C to 7 °C at the rate as mentioned above. The temperature regulation within the Daniovision chamber was achieved through the utilisation of an own-build circuit, comprising a dual-thermostat (Penn), a common resistance for heating and a chiller (Sunsun HYH .05D-D), connected to Daniovision’s water flow system, which enabled the immersion of the multiwell plate.

Marine heatwave experiments setting

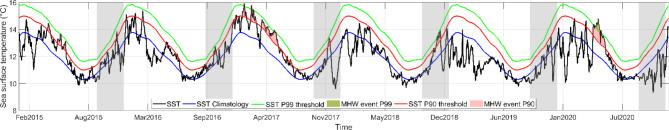

The non-constant thermal experimental regimes included a five-day heat pulse designed to simulate a short term MHW. These simulated temperatures were based on climatological data from 1982 to 2016 and reflects conditions observed during the 2015–2020 period, when MHW reached temperatures of up to 14 °C along the coast of Valdivia (Fig. 1). Additionally, a control temperature is represented by the mean spring sea surface temperature (SST), which is approximately 12 °C. A constant temperature regime at MHW temperature of 14 °C was also established. To evaluate the impact of temperature increase on the survival and development time during two substages of the moult cycle of the Zoea I, the MHW was applied during the early moulting cycle (intermoult substages, first 5 days) in ‘Early MHW’ treatment. In contrast, in ‘Late MHW’ treatment, the simulated MHW encompasses the latest 5 days of the moulting cycle, namely the premoult and Ecdysis substages.

Fig. 1.

Time series of daily sea surface temperature (SST, black line) from 2015 to 2020 along the coast of Valdivia (40°S, 73.75°W). The blue line represents the 35 year-climatology (1982–2016), while the green and red lines indicate the Marine heatwaves (MHWs) thresholds, corresponding to the 99th (P99) and 90th (P90) percentiles, respectively. The green and pink shaded areas indicate MHW events exceeding the P99 and P90 percentile thresholds, respectively. The grey bars highlight the spring seasons. SST data are based on ERA5 reanalysis project53. MHWs were detected following the methodology described by Hobday et al.1.

A total of 250 larvae from each single female batch were cultured in glass pots of 350 ml capacity, 50 larvae per pot, with the culture medium consisting of filtered seawater (through three microfilters and a UV pulse). To incorporate females’ variability, the larvae were derived from 4 females brood. Larvae were subjected to the two MHW treatments plus two constant temperature regimes (see Thermal Regimes in Table 1). The water in the pots was changed daily, and the pot’s larvae were monitored, counted, and provided with freshly hatched Artemia nauplii on an ad libitum basis. The moult of a larva was checked by tegument skull and the larval size. The D threshold was estimated, based our results through larval activity and tegument changes (Supplementary document), also in accordance with the literature42,43, around the 50% of this 11 days development time.

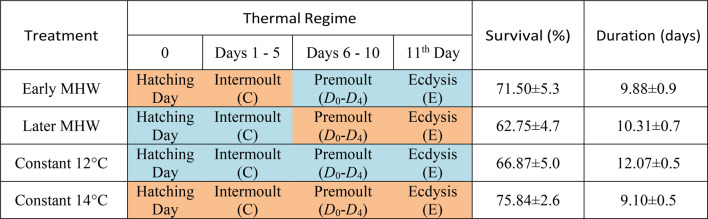

Table 1.

Treatments and their respective thermal regimes followed during the experiments.

Orange boxes represent 14 °C acclimatization, and blue boxes 12 °C acclimatization. Respectively, the mean survival rate and larval development time aside their females standard error, obtained from the experimental culture of Metacarcinus edwardsii zoea for each of the treatments. P-values between the MHW treatments are available in the table S2. Of the supplementary document.

Data analyses

To moulting cycle activity assesses, the distance moved during 1-hour acquisition for each larva were averaged by female and day. To test the statistical significance of the findings, data were transform to natural logarithm to make it normal and a one-way ANOVA and a post hoc LSD test were conducted in R (v.4.2.2) and Rstudio (2024.04.2)44 using the packages agricolae, dplyr, multcompView and ggplot2 for visualisation purposes45–48.

To estimate thermal optimum of larvae activity, five-minute acquisitions for each larva was analysed in Ethovision software (version XT-17), and then averaged of the distanced moved per temperature across the entire thermal ramp was obtained. These values were assessed with the rTPC and nls.multstart packages49 in R (v.4.2.2). The model selected by Akaike’s value was the Flinn (1991) model of thermal performance curve (TPC), which was created in the first time for parasitic waps analysed50. The generated parameters were the breadth (width of the range of temperatures in where the curve is over 80% of the peak for larval activity), the maximum rate (rate of the peak of the curve), temperature optimum (temperature of the peak of the curve for larval activity) and lower and upper optimum temperature (lower and higher temperature limits in where the rate of the curve are over the 80% of the maximum rate).

For the MHW experiments, the survival and moulting days analyses were conducted in R (v.4.2.2) and Rstudio (2024.04.2)38 using the survival and survminer packages to generate Kaplan-Meier curves and incorporate the progenitor female as a random factor for the Shared Frailty Cox model values51,52.

Results

Larval activity across to the moult cycle

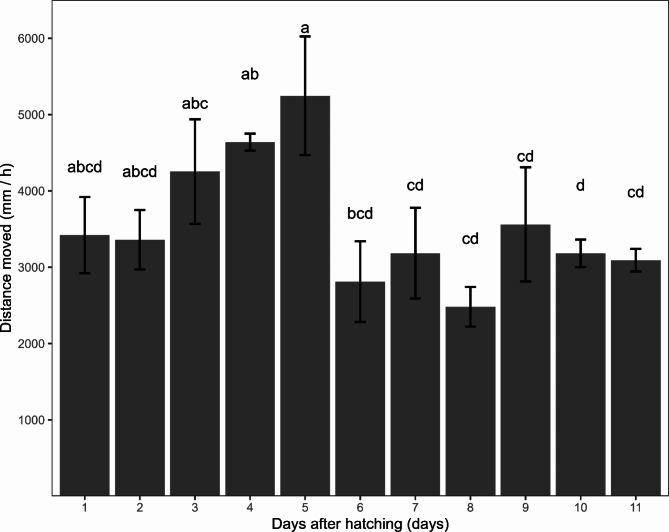

The daily recordings were conducted from day 1 to 11 post-hatching for hazard zoea I larvae at a constant temperature of 12 °C. By the 11th day, above 50% of the larvae had undergone a moult to Zoea II. The mean distance moved per larva per day (Fig. 2) demonstrated a notable increase in the movement of the larvae from days 2 to 5 post-hatching. A pronounced decline in the mean distance moved was observed between the fifth and sixth day, which would represent the transition from intermoult to premoult substage (D threshold). Mean and standard error from each day is available in Table S1. of the Supplementary document.

Fig. 2.

The average distance moved per individual in an hour tracked throughout the days of the first zoea at 12 °C. The black brackets represent the standard error between the 4 female’s larvae. Bars showing the same letter denote no statistical differences among days after hatching.

The images of this section of the telson from a random larva sampled daily to distinguish tegument changes during the moulting cycle are supplied in the Supplementary Document. The images from the 5th and 6th day larval telson highlight as a thickened cuticle is observed in the 5th day and a slight detach on 6th day. There was seem pollution or possible fungi in the microscopic telson assembles maybe increasing through days in some individuals, even of that, there was no pattern of decreasing in the swimming activity to link directly the results with a possible pollution.

To provide a control, the recordings from zoea I and zoea II larvae on their first day within the moulting cycle (first and twelfth days, respectively) were compared. No meaningful differences were identified (distance moved of 3756 ± 282 and 3844 ± 374 mm, respectively). Differences between females’ brood were also significant (p-value < 0.001).

Thermal experiments

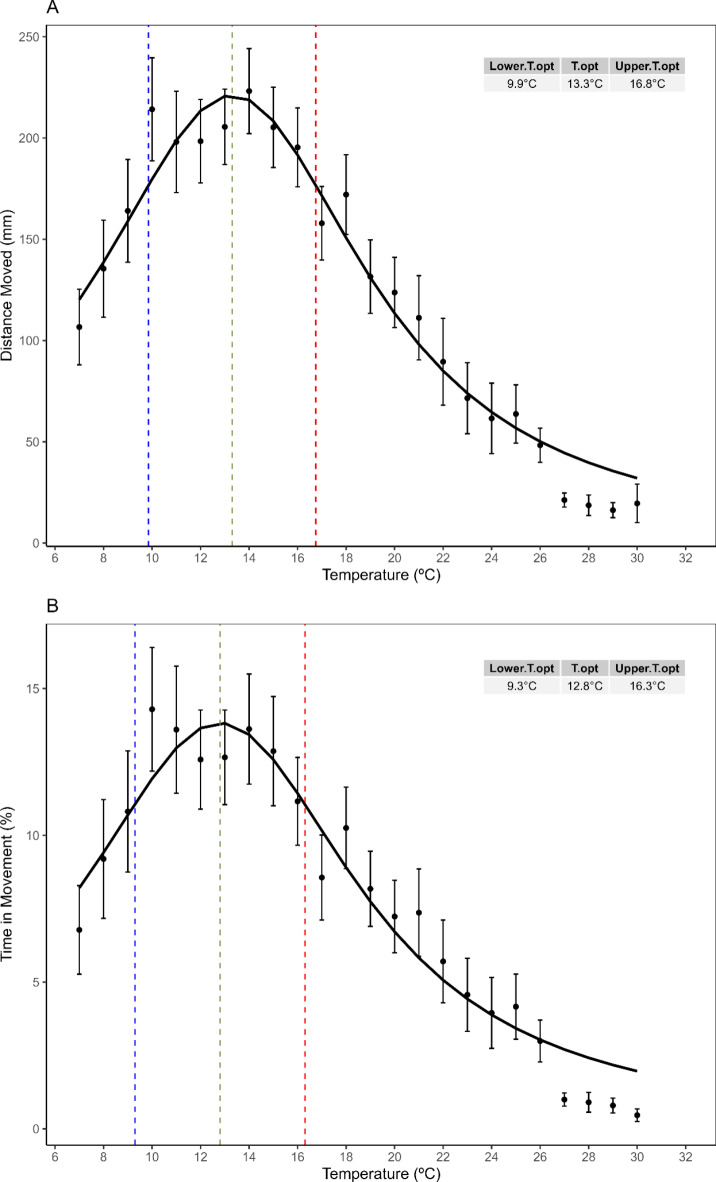

Thermal performance curve

The optimal temperature was estimated to be 12.8 °C and 13.3 °C based on the time movement and the distance moved, respectively (Fig. 3). At these temperatures, the maximum time in movement was approximately 14% of the total larval recording period, while the maximum distance moved was 221 mm. Additionally, the thermal optimal range was identified as spanning from 9.3 °C to 16.3 °C and 9.9 °C to 16.8 °C for both variables (Fig. 3), corresponding to breadths of 7 and 6.9 °C, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Thermal performance curves fitted with the Flinn model, based on (A) the distance moved and (B) the percent of time in movement by zoea freshly released in a 5-minute record. Blue and red dashed lines represent the lower and upper thermal optimal limits, respectively. The green dashed line denotes the optimal temperature. Top-right table show the values corresponding to the three optimum parameters highlight by the dashlines. Black dots and brackets represent the mean and standard error between 48 larvae performance per temperature.

Marine heatwave experiments

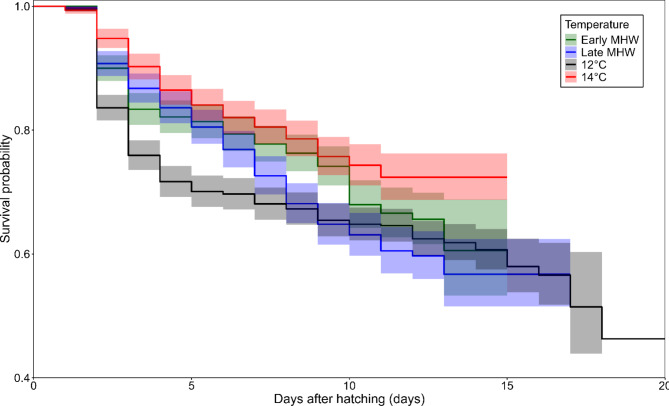

The data indicated that all treatments resulted in a survival rate of over 60% for larvae reaching zoea II. However, the application of a MHW during the intermoult sub-stage (see Table 1, ‘Early MHW’) resulted in an increased survival rate of approximately 72%, which was comparable to the survival probability curve of the constant regime at 14 °C (see Table 1), which was around 76%. It is noteworthy that neither treatment showed statistical significance. However, they were significantly higher than the opposite treatment (see Table 1, Late MHW which had a survival rate of 63%. The control regime at 12 °C presents a survival rate of approximately 67%. Regardless of when the MHW was applied or if the temperature of 14 °C was maintained throughout the full cycle, the shared Cox model showed statistical significance between all (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Shared-cox model curves of survival of Metacarcinus edwardsii. Coloured lines represent the estimated survival probability for each treatment of thermal regime through the days of zoea I development. The shaded colours show confidence interval (level 0.95).

The developmental period of the Zoea I stage was markedly abbreviated across all temperature regimes compared to the control (constant 12 °C). As well as it could be seen in the Kaplan-Meier survival curves (Fig. 4), Table II demonstrates that a higher constant temperature regime resulted in an accelerated development. At the highest temperature treatment of 14 °C, 50% of the successful larvae reached the next stage at 9.1 days after hatching (DAH), while at 12 °C it was 12.07 DAH. In the case of fluctuating thermal regimes, the instar duration was shortened, with the moult occurring in 9.88 (‘Early MHW’ treatment) and 10.31 (‘Late MHW’ treatment) days. This indicates that the timing of the moult was considerably influenced by the timing of the simulated MHW (+ 2 °C) applied within the moulting cycle. However, the Cox model demonstrated that both treatments also exhibited significant effects. All thermal regimes shown statistically significant differences (p-value < 0.01), as well as the females’ frailty (between females of offspring, p-value < 0.001).

Discussion

To estimate larval performance, the swimming behaviour of the larvae was tested through the measurement of their distance moved and time in movement rates to fit the thermal performance curves for the one-day-old M. edwardsii larvae. Currently, physiological rates (growth, development, oxygen consumption) are the most used to model thermal niches. However, direct measures of fitness, such as survival, fecundity, and predation, are also being employed12, which represents an intriguing avenue for investigation, offering insights into the energetic balance and the link between active metabolism and behaviour. Moreover, it encompasses individual ecological responses coupled with the daily requirements of organisms in their natural habitats. The interaction between fitness and metabolism suggests that metabolic processes may be a predictor of larval swimming behaviour54. However, some researchers have questioned the use of classical physiological thermal performance curves by itself to estimate species distribution, without considering the possible decoupling with behavioural TPC under stress conditions55. An effective swimming ability in larvae is crucial for their survival in the wild, as it enables them to forage, migrate vertically, couple with currents, capture prey and escape predators. This ultimately determines the functional success of the larvae, which in turn affects their dispersal and survival.

Considering these findings, it can be posited that the MHW-induced temperature is more closely aligned with the optimal swimming performance of the larvae, thereby ensuring a greater degree of compatibility with their long-term physiological requirements. However, the findings indicate that a change in this performance rate during the premoult substage could result in the larvae becoming nutritionally depleted and ultimately leading to mortality. The results demonstrate that the level of activity during the moult cycle declines markedly towards the end of the developmental stage, which coincides with the onset of the premoult42,43. The observed reduction in swimming activity may be linked to an energy economy, whereby any additional energy expenditure may be crucial for survival.

Given that the early stages are considered to be the most vulnerable periods in the context of environmental change14,18, this approach, which employs functional thermal performance in the context of larval behaviour, appears to be a promising avenue for addressing the impacts of chronic and acute alterations in seawater temperature, which are driven by global warming and marine heatwaves. By incorporating a more realistic definition of the thermal niche, which encompasses individual ecological performance, this approach offers a valuable opportunity to enhance our understanding of the effects of environmental change on marine life.

In MHW experiment, to well-fed larvae, if thermal stress (MHW) occurs during the intermoult substage (for example, on the first day) and temperature is close to optimum for larvae, this will impact positively some processes, such as organogenesis, which requires high levels of cellular division. The relationship between temperature and cellular division rate in ectotherms19 indicate that thermal increase in the environment would accelerate this process, shortening the time needed to pass to the next stage. Notably, applying a MHW during the late substage of the moult cycle, so after the D0 threshold showed deleterious impacts on larvae. The precise mechanism by which this phenomenon occurs remains unclear. However, apolysis (the detachment of the old cuticle from the epidermis) during the premoult substage has been identified as a critical process during moult cycles26. Sudden changes in temperature could potentially influence this process. Furthermore, the premoult substage is characterised as an autonomous feeding phase23,56. It has been demonstrated that elevated temperatures lead to an increase in food requirements21, suggesting that a MHW during the premoult substage could result in elevated energetic demand, potentially leading to a deficiency in nutritional reserves for a successful moult.

It has also been argued in other studies the possibility of a positive effect of MHW in crab larvae if their thermal threshold is not exceeded57. The highest zoea I survival was reached at 14 °C. This value is close to optimum temperature drives, which shows high and effective swimming activity, as is shown in the thermal performance curve at 13.3 °C. An organism developing at its optimum swimming potential could improve feeding by capturing prey, which increases its nutritional reserve for the premoult substage, which also leads to increase survival probability58. In fact, the control temperature of 12 °C (local temperature for the period) showed the worse performance in survival probability analysis, demonstrating that there is no thermal local adaptation for larvae in this species.

This fact is to be expected due to the high population connectivity across the majority of the observed distributional range of M. edwardsii34,40 where spring temperature varies between 8 °C and 18 °C along the Chilean coast from 48° to 30°S (distribution based on GBIF observations during the 21st century). Notably, this temperature range is highly comparable to the thermal range of optimal larval behavioural performance (10 °C to 17 °C). This suggests that these ecologically relevant temperatures may prove more useful than critical temperatures (i.e. CTmin and CTmax) for understanding the geographic distributions of meroplanktonic species.

The study recalls the necessity of assessing potential larval dispersal as a crucial element in determining population connectivity. This is particularly crucial for species subjected to fishery exploitation, where effective management depends on accurate stock identification18. For example, crab fishery control measures in Chile are not differentiated by regions, assuming only one stock exists. This is supported by genetic flow studies indicating non-structured populations34, which currently allow continuous recruitment even in the most harvested locations. Nevertheless, a reduction in LDT resulting from alterations in thermal regimes could potentially impact larval dispersal, leading to a shift in population structure. It can be reasonably assumed that the southernmost and northernmost populations are the most susceptible to thermal extremes. Consequently, their fishery resilience is likely to be threatened in a scenario where the population is structured. It can be posited that species with a broad biogeographical range are susceptible to a reduction in overfishing resilience and an increased vulnerability to overexploitation.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported by FONDECYT 1220179 assigned to L.M.P. and by FONDECYT 1230556 assigned to D.V. During writing, L.M.P., J.G-V., I.G., M.J.C. and K.P. were supported by FONDAP grant #15150003 (IDEAL) and L.M.P. was supported by Regional Program ANID R20F0002. LMP thanks to Ayelen Araya for laboratory assitance during experiments. The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable contributions.

Author contributions

L.M.P., D.V., I.G. and M.J.B. conceived and designed the study. M.J.B. and M.J.C. performed the experiments while L.M.P. and K.P. supported them. J.G-V. and L.M.P. assess climatological data. L.M.P., D.V., N.R.H. and M.J.B. analysed the experimental data. L.M.P. and M.J.B. drafted the manuscript. All authors read, approved, and contributed to the final manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available in the github repository, https://github.com/CoteBruning/Bruningetal.2024_Effects-of-local-marine-heatwaves-in-decapod-larvae.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hobday, A. J. et al. A hierarchical approach to defining marine heatwaves. Prog. Oceanogr.141, 227–238 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walther, G. R. et al. Ecological responses to recent climate change. Nature416, 389–395 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parmesan, C. & Yohe, G. W. A globally coherent fingerprint of climate change impacts across natural systems. Nature421, 37–42 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kikuchi, E., De Grande, F. R., Duarte, R. M. & Vaske-Júnior, T. Thermal response of demersal and pelagic juvenile fishes from the surf zone during a heat-wave simulation. J. Appl. Ichthyol.35, 1209–1217 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 5.IPCC. 2019: IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate (eds. Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D.C., Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E., Mintenbeck, K., Alegría, A., Nicolai, M., Okem, A., Petzold, J., Rama, B. & Weyer, N.M.) 755 (Cambridge University Press, 2019). 10.1017/9781009157964.

- 6.Lutterschmidt, W. I. & Hutchison, V. H. The critical thermal maximum: History and critique. Can. J. Zool.75, 1561–1574 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carter, M. J. et al. Upper thermal limits and risk of mortality of coastal Antarctic ectotherms. Front. Mar. Sci.9 (2023).

- 8.Marochi, M. Z., Grande, F. R. D., Farias-Pardo, J. C., Montenegro, Á. & Costa, T. M. Marine heatwave impacts on newly-hatched planktonic larvae of an estuarine crab. Estuar. Coastal. Shelf Sci.278 (2022).

- 9.Monteiro, M., Marques, S. C., Freitas, R. & Azeiteiro, U. M. An emergent treat: Marine heatwaves—implications for marine decapod crustacean species—an overview. Environ. Res.229, 116004 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saleuddin, S., Leys, S. P., Roer, R. D. & Wilkie, I. C. Frontiers in Invertebrate Physiology: A Collection of Reviews Vol. 2 (Apple Academic, 2023).

- 11.Panchuk, J., Schwerdt, L. & Ferretti, N. Differences between thermal preference and thermal performance in a wintry spider Mecicobothrium thorelli: Are the spiders under evolutionary pressures on their seasonal activity? Can. J. Zool.101, 1093–1100 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rebolledo, A. P., Sgrò, C. M. & Monro, K. Thermal performance curves are shaped by prior thermal environment in early life. Front. Physiol.12, 738338 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Storch, D., Fernández, M., Navarrete, S. A., Hans-Otto & Pörtner Thermal tolerance of larval stages of the Chilean kelp crab Taliepus DentatusMar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.429, 157–167 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pandori, L. L. & Sorte, C. J. The weakest link: Sensitivity to climate extremes across life stages of marine invertebrates. Oikos128, 621–629 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anger, K., Thatje, S., Lovrich, G. & Calcagno, J. Larval and early juvenile development of Paralomis granulosa reared at different temperatures: Tolerance of cold and food limitation in a lithodid crab from high latitudes. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.253, 243–251 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spitzner, F. et al. An atlas of larval organogenesis in the European shore crab Carcinus maenas l. (decapoda, brachyura, portunidae). Front. Zool.15, 1–39 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balogh, R. & Byrne, M. Developing in a warming intertidal, negative carry over effects of heatwave conditions in development to the pentameral starfish in Parvulastra exigua. Mar. Environ. Res.162, 105083 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marochi, M. Z., Costa, T. M. & Buckley, L. B. Ocean warming is projected to speed development and decrease survival of crab larvae. Estuar. Coastal. Shelf Sci.259, 107478 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Begasse, M. L., Leaver, M., Vazquez, F., Grill, S. W. & Hyman, A. A. Temperature dependence of cell division timing accounts for a shift in the thermal limits of C. Elegans and C. Briggsae. Cell. Rep.10, 647–653 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Connor, M. I. et al. Temperature control of larval dispersal and the implications for marine ecology, evolution, and conservation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.104, 1266–1271 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Paul, A. J. & Nunes, P. Temperature modification of respiratory metabolism and caloric intake of Pandalus borealis (Krøyer) first zoeae. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol.66, 163–168 (1983). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levine, D. M. & Sulkin, S. D. Partitioning and utilization of energy during the larval development of the xanthid crab, Rhithropanopeus harrisii (gould). J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol.40, 247–257 (1979). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anger, K. The d0 threshold: A critical point in the larval development of decapod crustaceans. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol.108, 15–30 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Drach, P. Mue Et cycle d’intermue chez les crustacés décapodes. Ann. De I’Institut Océanographique19, 103–391 (1939). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giménez, L. & Torres, G. Larval growth in the estuarine crab Chasmagnathus granulata: The importance of salinity experienced during embryonic development, and the initial larval biomass. Mar. Biol.141, 877–885 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anger, K. The Biology of Decapod Crustacean Larvae Vol. 14 (AA Balkema Publishers Lisse, 2001).

- 27.Reinhold, K. Energetically costly behaviour and the evolution of resting metabolic rate in insects. Funct. Ecol.13, 217–224 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Forward, R. B., Diaz, H. & Ogburn, M. B. The ontogeny of the endogenous rhythm in vertical migration of the blue crab Callinectes sapidus at metamorphosis. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol.348, 154–161 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gall, M. L., Holmes, S. P., Campbell, H. & Byrne, M. Effects of marine heatwave conditions across the metamorphic transition to the juvenile sea urchin (Heliocidaris Erythrogramma). Mar. Pollut. Bull.163, 111914 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duguid, W. D., Iwanicki, T. W., Qualley, J. & Juanes, F. Fine-scale spatiotemporal variation in juvenile chinook salmon distribution, diet and growth in an oceanographically heterogeneous region. Prog. Oceanogr.193, 102512 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Monteiro, M., Azeiteiro, U. & Queiroga, H. Climatic resilience: Marine heatwaves do not influence the variations of green crab (Carcinus maenas) megalopae supply patterns to a western iberian estuary. Mar. Environ. Res. 106567 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Forward, R. B. Behavioral responses of crustacean larvae to rates of temperature change. Biol. Bull.178, 195–204 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Domenici, P., Allan, B. J. M., Lefrançois, C. & McCormick, M. I. The effect of climate change on the escape kinematics and performance of fishes: Implications for future predator-prey interactions. Conserv. Physiol.7 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Veliz, D. et al. Spatial and temporal stability in the genetic structure of a marine crab despite a biogeographic break. Sci. Rep.12, 14192 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pineda, J., Hare, J. A. & Sponaugle, S. Larval transport and dispersal in the coastal ocean and consequences for population connectivity. Oceanography20, 22–39 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pardo, L. M., Rosas, Y., Fuentes, J. P., Riveros, M. P. & Chaparro, O. R. Fishery induces sperm depletion and reduction in male reproductive potential for crab species under male-biased harvest strategy. PLoS One10, e0115525 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hamame, M. E., Aedo, G., Ortiz, P., Olguin, A. & Pardo, L. M. Biological and fisheries indicators for the small-scale marble crab fishery in northern Patagonia: Recommendations for improving a monitoring program and stock assessment of a data-limited fishery. Front. Mar. Sci.11, 1392758 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pardo, L. M., Rubilar, P. S. & Fuentes, J. P. North patagonian estuaries appear to function as nursery habitats for marble crab (Metacarcinus Edwardsii). Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci.36, 101315 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Quintana, R. et al. Larval development of the edible crab, Cancer edwardsi bell, 1835 under laboratory conditions (decapoda, brachyura). Reports Usa Mar. Biol. Institute-Kochi Univ. (Japan) (1983).

- 40.Rojas-Hernandez, N., Veliz, D., Riveros, M. P., Fuentes, J. P. & Pardo, L. M. Highly connected populations and temporal stability in allelic frequencies of a harvested crab from the southern Pacific coast. PLoS One. 11, e0166029 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Missionário, M. et al. Sex-specific thermal tolerance limits in the ditch shrimp Palaemon varians: Eco-evolutionary implications under a warming ocean. J. Therm. Biol.103, 103151 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gorissen, S. & Sandeman, D. Moult cycle staging in decapod crustaceans (pleocyemata) and the Australian crayfish, Cherax destructor clark, 1936 (decapoda, parastacidae). Crustaceana95, 165–217 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anger, K., Harzsch, S. & Thiel, M. (eds). Developmental Biology and Larval Ecology: The Natural History of the Crustacea Vol. 7 223–253 (Oxford University Press, 2020).

- 44.RStudio Team & RStudio RStudio: Integrated Development for R (PBC, 2020). http://www.rstudio.com/.

- 45.De Mendiburu, F. agricolae: Statistical Procedures for Agricultural Research. R package version 1.3-7. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=agricolae (2023).

- 46.Wickham, H., François, R., Henry, L., Müller, K. & Vaughan, D. dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation. R package version 1.1.4. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=dplyr (2023).

- 47.Graves, S., Piepho, H. & Dorai-Raj, S. multcompView: Visualizations of Paired Comparisons. R package version 0.1-10. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=multcompView (2024).

- 48.Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis (Springer, 2016).

- 49.Padfield, D., O’Sullivan, H. & Pawar, S. Rtpc and nls. Multstart: A new pipeline to fit thermal performance curves in R.

- 50.Flinn, P. Temperature-dependent functional response of the parasitoid Cephalonomia waterstoni (gahan) (hymenoptera: Bethylidae) attacking rusty grain beetle larvae (coleoptera: Cucujidae). Environ. Entomol.20, 872–876 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kassambara, A., Kosinski, M. & Biecek, P. Survminer: Drawing survival curves using ‘ggplot2’. R package version 1 (2016).

- 52.Therneau, T. M. & Grambsch, P. M. The Cox Model 39–77 (Springer, 2000).

- 53.Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R Meteorol. Soc.146, 1999–2049 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bozinovic, F., Calosi, P. & Spicer, J. I. Physiological correlates of geographic range in animals. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst.42, 155–179 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Monaco, C. J., McQuaid, C. D. & Marshall, D. J. Decoupling of behavioural and physiological thermal performance curves in ectothermic animals: A critical adaptive trait. Oecologia185(4), 583–593 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Anger, K., Storch, V., Anger, V. & Capuzzo, J. Effects of starvation on moult cycle and hepatopancreas of stage in lobster (Homarus americanus) larvae. Helgoländer Meeresuntersuchungen. 39, 107–116 (1985). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Macedo, T. P., Zhao, Q., Costa, N. V. & Freire, A. S. Ocean temperature and density dependence as key drivers of the population dynamics of an intertidal crab at the Brazilian oceanic islands. Popul. Ecol.64, 349–364 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Anger, K. Patterns of growth and chemical composition in decapod crustacean larvae. Invertebr. Reprod. Dev.33, 159–176 (1998). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available in the github repository, https://github.com/CoteBruning/Bruningetal.2024_Effects-of-local-marine-heatwaves-in-decapod-larvae.