Abstract

The c-Jun NH2-terminal protein kinase (JNK) is a member of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) group and is an essential component of a signaling cascade that is activated by exposure of cells to environmental stress. JNK activation is regulated by phosphorylation on both Thr and Tyr residues by a dual-specificity MAPK kinase (MAPKK). Two MAPKKs, MKK4 and MKK7, have been identified as JNK activators. Genetic studies demonstrate that MKK4 and MKK7 serve nonredundant functions as activators of JNK in vivo. We report here the molecular cloning of the gene that encodes MKK7 and demonstrate that six isoforms are created by alternative splicing to generate a group of protein kinases with three different NH2 termini (α, β, and γ isoforms) and two different COOH termini (1 and 2 isoforms). The MKK7α isoforms lack an NH2-terminal extension that is present in the other MKK7 isoforms. This NH2-terminal extension binds directly to the MKK7 substrate JNK. Comparison of the activities of the MKK7 isoforms demonstrates that the MKK7α isoforms exhibit lower activity, but a higher level of inducible fold activation, than the corresponding MKK7β and MKK7γ isoforms. Immunofluorescence analysis demonstrates that these MKK7 isoforms are detected in both cytoplasmic and nuclear compartments of cultured cells. The presence of MKK7 in the nucleus was not, however, required for JNK activation in vivo. These data establish that the MKK4 and MKK7 genes encode a group of protein kinases with different biochemical properties that mediate activation of JNK in response to extracellular stimuli.

Mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) are components of pathways that relay signals to particular cell compartments in response to a diverse array of extracellular stimuli (38, 42, 63, 83). Activated MAPK can translocate to the nucleus and phosphorylate substrates, including transcription factors, thereby eliciting a biological response. At least three groups of MAPKs have been identified in mammals: ERK (extracellular signal-regulated kinase), JNK (c-Jun N-terminal kinase; also known as stress-activated protein kinase), and p38 MAPK (also known as cytokine-suppressive anti-inflammatory drug-binding protein). ERK contributes to the response of cells to signals initiated by many growth factors and hormones through a Ras-dependent pathway (63). In contrast, JNK and p38 MAPK are activated by environmental stresses, such as UV radiation, osmotic shock, heat shock, protein synthesis inhibitors, and lipopolysaccharide (38, 83). The JNK and p38 MAP kinases are also activated by treatment of cells with proinflammatory cytokines, including interleukin-1 (IL-1) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) (38, 83). MAPKs are involved in the control of a wide spectrum of cellular processes including growth, differentiation, survival, and death (38, 63).

MAPKs are activated by conserved protein kinase signaling modules which include a MAPK kinase kinase (MAPKKK) and a dual-specificity MAPK kinase (MAPKK). The MAPKKK phosphorylates and activates the MAPKK which, in turn, activates the MAPK by dual phosphorylation on threonine and tyrosine residues within a Thr-Xaa-Tyr motif located in protein kinase subdomain VIII (38, 63). Separate protein kinase signaling modules are used to activate different groups of MAPKs (13). The MAPKKK and MAPKK that activate the ERK MAP kinases include c-Raf-1 and MEK1, respectively (63). The c-Raf-1 protein kinase activity is regulated by the small GTPase Ras, which induces translocation of c-Raf-1 to the plasma membrane, where it is thought to be activated (63). In contrast, JNK and p38 MAPK appear to be activated by small GTPases of the Rho family (3, 10, 49, 59, 91). The mechanism by which Rho GTPases activate the JNK and p38 MAPK signaling pathways is unclear. Although Rho GTPases interact with the PAK group of STE20-related protein kinases, it appears that JNK and p38 MAP kinase activation may be mediated, in part, by the mixed-lineage group of protein kinases (MLK) (62, 74) or by the scaffold protein POSH (72). STE20-like protein kinases represent possible targets for other upstream signals that lead to JNK activation. Among the STE20-like protein kinases, the hematopoietic progenitor kinase 1 (HPK1) (2, 37, 41, 79) and the kinase homologous to STE20/SPS1 (KHS) (78) appear to specifically activate JNK. There is evidence for significant complexity in the mechanism of initiation of the JNK and p38 MAPK signaling pathways because of the large number of MAPKKK protein kinases that contribute to stress-activated MAPK signaling (19, 38). Whether there is a general or a specific role for Rho family GTPases in the activation of the JNK and p38 MAP kinase signaling pathways has not been established.

The protein kinases that have been reported to act as MAPKKKs for the JNK signaling pathway include the MEK/ERK kinase (MEKK) group, the MLK group, TPL-2, ASK1, and TAK1 (19, 38). The MEKK group of MAPKKKs includes MEKK1 (43, 50, 86), MEKK2 (6, 11), MEKK3 (6, 11, 15), MEKK4/MTK1 (25, 71), and MAPKKK5/MEKK5 (80). The MLK group of MAPKKKs includes MLK1 (14), MLK2/MST (14, 33), MLK3/SPRK (62, 74, 75), dual-leucine zipper-bearing kinase (DLK)/MUK (18, 32), and leucine zipper-bearing kinase (LZK) (64). Binding sites for the Rho family GTPases Cdc42 and Rac1 have been described for MLK1, MLK2, and MLK3 (but not DLK or LZK) (7). It has also been reported that MEKK1 and MEKK4 (but not MEKK2 or MEKK3) bind directly to the Rho family GTPases Cdc42 and Rac1 (20). These interactions between Rho GTPases and MAPKKKs may contribute to the effects of Rho GTPases on JNK activation. MAPKKK protein kinases that do not interact with Rho GTPases may mediate the effects of Rho-independent signals that lead to JNK activation.

Several MAPKKs have been identified. ERK is activated by MEK1 and MEK2 (1); p38 MAPK is activated by MKK3 (13), MKK4 (13, 45), and MKK6 (28, 53, 61, 68); JNK is activated by MKK4 (13, 45, 65). The existence of JNK activators distinct from MKK4 was suggested by chromatographic fractionation of cell extracts (48, 52) and by the results of targeted disruption of the MKK4 gene (58, 87). We (76) and others (21, 34, 36, 44, 46, 55, 77, 84, 89) have recently characterized the novel JNK activator MKK7. In contrast to MKK4, which activates both JNK and p38 MAPK, the MKK7 protein kinase selectively activates only JNK. Interestingly, the two JNK activators D-MKK4 (Drosophila MKK4) (29) and Hep/D-MKK7 (26, 67) are conserved in Drosophila. Genetic analysis demonstrates that D-MKK4 and Hep/D-MKK7 serve nonredundant functions in the fly (38). Similarly, gene disruption experiments demonstrate that MKK4 is an essential gene in the mouse, indicating that MKK7 is unable to fully substitute for the function of MKK4 (24, 57, 58, 70, 87). These data demonstrate that MKK4 and MKK7 serve nonredundant functions as activators of the JNK MAP kinases in vivo.

We report here the molecular cloning of the MKK7 gene and the characterization of MKK7 isoforms that are created by alternative splicing. The MKK7 isoforms are differentially activated by upstream signals, and their regulation differs from that of the MKK4 isoforms. These data establish that JNK activation is mediated by a family of protein kinases that are formed by the alternative splicing of two genes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Human TNF-α and IL-1α were from Genzyme Corp. [γ-32P]ATP was obtained from Amersham Corp. Recombinant glutathione S-transferase (GST)–c-Jun and GST-JNK1 were purified from bacteria as described elsewhere (12). Mammalian expression vectors for MKK4 isoforms (13) and MKK7α1 (76) have been described elsewhere. MKK4β includes an additional 34 amino acids fused to the NH2 terminus of MKK4 (13). The expression vectors pCMV-HA-MEK1 and pCMV-HA-ΔN3-MEK1-EE were provided by N. Ahn (47). The expression vectors pEBG-KHS (78), pSRα-HPK1 (37), pMT2T-MEKK3 (15), pCDNAI-MTK1/MEKK4 (71), pCDNA3-MLK3 (74), and pSRα-DLK (33) were provided by J. Blenis, T. Tan, U. Siebenlist, H. Saito, S. Gutkind, and J. Avruch, respectively.

Molecular cloning of MKK7 isoforms.

Genomic DNA clones corresponding to the MKK7 locus were isolated by screening a λ FixII murine genomic library (Stratagene, Inc.), using the MKK7α1 cDNA as a probe. The genomic sequence of MKK7 was obtained with an Applied Biosystems model 373A machine. To identify additional MKK7 isoforms, a mouse testis cDNA library cloned in the phage λZAPII (Stratagene, Inc.) was screened by using the MKK7α1 cDNA as a probe. Positive clones were plaque purified and sequenced. The MKK7 isoforms were subcloned into the mammalian expression vectors pCDNA3 (Invitrogen Inc.) and pEBG (86). The Flag epitope (Asp-Tyr-Lys-Asp-Asp-Asp-Asp-Lys; Immunex Corp.) was fused to the NH2 terminus of the MKK7 isoforms by insertional overlapping PCR (35). A nuclear export signal (NES) sequence (23) corresponding to residues 32 to 51 of MEK1 (Ala-Leu-Gln-Lys-Lys-Leu-Glu-Glu-Leu-Glu-Leu-Asp-Glu-Gln-Gln-Arg-Lys-Arg-Leu-Glu) was inserted following the Flag epitope, by using a PCR-based procedure to create NES-MKK7 isoforms. Bacterial expression of MKK7 was performed with the vector pGEX-4T-1 (Pharmacia-LKB Biotechnology, Inc.).

FISH.

Lymphocytes isolated from male mouse spleen were used for chromosome fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis (FISH) (30, 31). Metaphase chromosomes spread on a glass slide were air dried, baked at 55°C (1 h), and digested with RNase A. The DNA was denatured for 2 min at 70°C in 70% formamide in 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) and dehydrated with ethanol. DNA prepared from a mouse MKK7 genomic clone was biotinylated and used as the hybridization probe (30). The FISH and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining were recorded on film. The assignment of the FISH mapping data with chromosomal bands was achieved by superimposing the FISH signals with images of the DAPI-banded chromosomes.

Tissue culture and transfection assays.

COS-7 and 293 cells were cultured at 37°C in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Life Technologies, Inc.), 2 mM glutamine, 100 U of penicillin per ml, and 100 U of streptomycin per ml in a humidified environment with 5% CO2. Transient transfections were performed with the LipofectAMINE reagent (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. After 36 h, the cells were serum starved for 1 h and treated with UV-C (80 J/m2), anisomycin (5 μg/ml), TNF-α (20 ng/ml), or IL-1α (2 to 10 ng/ml) for 30 min prior to lysis. Cell extracts were prepared in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100, 0.137 M NaCl, 25 mM β-glycerophosphate, 2 mM EDTA, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 10 μg of leupeptin per ml, 10 μg of aprotinin per ml, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) and centrifuged at 15,000 × g (15 min at 4°C). The concentration of total soluble protein in the supernatant was quantitated by the Bradford method (Bio-Rad).

Binding assays.

GST-tagged MKK7 proteins were isolated by incubation with glutathione (GSH)-Sepharose (Pharmacia-LKB Biotechnology) in lysis buffer (4 h at 4°C). The beads were washed five times with lysis buffer, and the presence of bound JNK was examined by immunoblot analysis.

Protein kinase assays.

Epitope-tagged MAPKK was immunoprecipitated from cell extracts by incubation for 3 h at 4°C with the Flag-specific monoclonal antibody M2 (IBI-Kodak) bound to protein G-Sepharose beads (Pharmacia-LKB Biotechnology). GST-tagged MAPKK was isolated by incubation for 3 h at 4°C with GSH-Sepharose beads (Pharmacia-LKB Biotechnology). The complexes were washed twice with lysis buffer and three times with kinase buffer (25 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 25 mM β-glycerophosphate, 25 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1 mM sodium orthovanadate). MAPKK activity was measured at 30°C for 20 min in 30 μl of kinase buffer containing 0.5 μg of GST-JNK1, 2 μg of GST–c-Jun, and 50 μM [γ-32P]ATP (10 Ci/mmol; 1 Ci = 37.6 GBq). The reactions were terminated by addition of Laemmli sample buffer. Proteins were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE 10% polyacrylamide gel) and identified by autoradiography. The incorporation of [32P]phosphate into GST–c-Jun was quantitated by PhosphorImager analysis.

JNK protein kinase assays were performed with extracts of cells transfected with HA-JNK1. The JNK was immunoprecipitated with an antibody to the HA epitope tag (12CA5; Boehringer Mannheim). Protein kinase activity was measured in the immune complex with c-Jun as the substrate (12).

Western blot analysis.

Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE (10% gel), electrophoretically transferred to an Immobilon-P membrane (Millipore Inc.), and probed with the Flag-specific monoclonal antibody M2 (1:4000; IBI-Kodak) or a monoclonal antibody to MKK4 (1:1000; Pharmingen). Immune complexes were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (Lumiglo; Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories).

Immunofluorescence microscopy.

COS-7 cells were seeded onto glass coverslips coated with poly-l-lysine (Sigma Chemical Co.); 36 h after transfection, the cells were fixed for 10 min with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then permeabilized for 5 min with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS. After incubation for 15 min with 3% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS, the coverslips were incubated for 1 h with primary antibodies in PBS with 3% BSA. The primary antibodies were rabbit anti-MKK4 (K-18; 1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), goat anti-MKK7 (C-18; 1:100; Santa Cruz), rabbit anti-phosphorylated (on Thr-183 and Tyr-185) JNK (phospho-JNK) (9251; 1:100; New England Biolabs Inc.), and monoclonal antibodies (1:500) to Flag (M2) and HA (12CA5). Immune complexes were detected with Texas red-conjugated anti-mouse immunoglobulin (Ig), Texas red-conjugated anti-goat Ig, rhodamine-conjugated anti-rabbit Ig, and fluorescein-conjugated anti-rabbit Ig antibodies (1:100; Jackson ImmunoResearch, Inc.) in 3% BSA in PBS. After nuclei were stained for 1 min with DAPI (1:10,000; Molecular Probes, Inc.), the coverslips were mounted in Vectashield (Vector Laboratories, Inc.). All procedures were performed at room temperature. Fluorescence microscopy was performed with a Zeiss Axioplan microscope.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequences of the murine MKK7 cDNA clones have been deposited in GenBank with accession no. U93030, AF060943, AF060944, AF060945, AF060946, and AF060947.

RESULTS

Molecular cloning of MKK7 isoforms.

MKK7 has recently been identified as a specific activator of the JNK group of MAPKs. Northern blot analysis demonstrated the presence of at least two MKK7 mRNAs (2.2 and 4.2 kb) in adult murine tissues (76), an observation which suggested that MKK7 may be expressed as a group of alternatively spliced isoforms. To characterize members of the MKK7 group, we exhaustively screened a mouse testis cDNA library by using our original MKK7 clone (MKK7α1) as a probe. This analysis led to the identification of additional isoforms: MKK7α2, MKK7β1, MKK7β2, MKK7γ1, and MKK7γ2 (Fig. 1). The predicted amino acid sequences are identical except at the NH2 terminus (α, β, and γ isoforms) and at the COOH terminus (1 and 2 isoforms).

FIG. 1.

Primary structures of MKK7 protein kinase isoforms. The primary sequence of the mouse MKK7 protein kinase isoforms deduced from the sequences of cDNA clones are presented in single-letter code. Residues that are identical to those in MKK7γ2 (.), deletions (−), and termination codons (#) are indicated.

We isolated a murine genomic clone that encodes the MKK7 protein kinase isoforms. FISH analysis led to the mapping of the gene to mouse chromosome 11 region A2 (Fig. 2). Sequence analysis of the gene demonstrated the presence of 14 exons (Fig. 3). Sequence comparison of the gene with cDNA encoding the MKK7 isoforms demonstrated that these isoforms are created by the usage of alternative exons. This analysis indicated that MKK7 is a complex gene that expresses a group of MKK7 protein kinases.

FIG. 2.

The MKK7 gene is located on mouse chromosome 11. The MKK7 gene was identified by FISH analysis of murine metaphase chromosomes by using an MKK7 genomic clone as a probe. The FISH signal is illustrated on the left (arrow). The corresponding DAPI signal indicating chromosome 11 is shown on the right. Detailed comparison of DAPI-banded chromosome 11 with the FISH signal indicated that the MKK7 gene is located in region A2.

FIG. 3.

Schematic representation of the structure of the MKK7 gene. The MKK7 gene is formed by 14 exons. The alternative splicing that creates the α, β, γ, 1, and 2 isoforms of MKK7 is illustrated. The coding (black) and noncoding (grey) regions and excluded exons (striped) are shown. Initiation codons (ATG), termination codons (∗), and polyadenylation signals (•) are indicated.

Initiation codons in frame with upstream termination codons are located in separate exons in the 5′ region of the MKK7 gene. The α isoforms are created by using an initiation codon located in exon 4 in frame with an upstream termination codon located in exon 3 (Fig. 3). In contrast, the initiation codon (together with an upstream in-frame termination codon) used to create the β and γ isoforms is located in exon 1. Alternative splicing which includes or excludes exon 2 distinguishes the β and γ isoforms (Fig. 3).

Alternative splicing in the 3′ region of the gene changes the usage of termination codons to create a truncated COOH terminus (1 isoforms) and an extended COOH terminus that includes 33 additional amino acids (2 isoforms). The truncated COOH terminus results from the presence of an in-frame termination codon and a polyadenylation signal in exon 13 (Fig. 3). Alternative splicing within exon 13 immediately prior to this termination codon fuses the open reading frame to sequences located in exon 14. This fusion creates the longer COOH terminus that is characteristic of the 2 isoforms. A termination codon and a polyadenylation signal are located in exon 14.

Comparison of protein kinase activities of MKK7 isoforms.

We used a coupled protein kinase assay in vitro to examine the protein kinase activities of MKK7 isoforms that were isolated from transfected mammalian cells. This assay employs bacterially expressed JNK1 as a substrate for the MKK7 protein kinases. The activation of JNK1 by MKK7 was examined by using bacterially expressed c-Jun as a substrate for JNK. Control experiments indicated that MKK7 does not phosphorylate c-Jun (data not shown). These assays demonstrated that the activities of the MKK7β and MKK7γ isoforms were similar and that the alternative splicing at the COOH terminus of MKK7 (1 and 2 isoforms) did not markedly alter protein kinase activity (Fig. 4). In contrast, activities of the MKK7α isoforms were lower than those of the MKK7β and MKK7γ isoforms. Quantitation of the MKK7 activity by PhosphorImager analysis indicated that MKK7β1 was 37-fold more active than MKK7α1.

FIG. 4.

Effects of MKK7 homologs on JNK activation. (A) COS-7 cells were transfected with expression vectors encoding Flag epitope-tagged MKK7α1, MKK7α2, MKK7β1, MKK7β2, MKK7γ1, or MKK7γ2. The expression of each of these MKK7 isoforms was examined by immunoblot (IB) analysis using the Flag-specific monoclonal antibody M2. The MKK7 isoforms were immunoprecipitated, and their activities were measured in the immune complex by a coupled protein kinase assay (KA) using recombinant GST-JNK1 and GST–c-Jun as substrates. The phosphorylated c-Jun was detected after SDS-PAGE by autoradiography and was quantitated by PhosphorImager analysis. The effect of cotransfection with an empty expression vector (−) or with an MEKK1 expression vector (+) is shown. Similar results were observed in three separate experiments. (B) MKK7 activity, presented as relative protein kinase activity. (C) MKK7 activation caused by MEKK1 (fold activity over MKK7 activity in the absence of MEKK1).

The difference in protein kinase activity of the MKK7 isoforms was detected under basal conditions (Fig. 4). To determine whether similar differences could be detected following activation, we examined the effect of a strong activator of the JNK signaling pathway (MEKK1). We found that MEKK1 caused marked activation of all the MKK7 isoforms. The largest increase was observed for MKK7α1 and MKK7α2, which were activated by 34- and 20-fold, respectively (Fig. 4). The MKK7β and MKK7γ protein kinases were activated more modestly (three- fivefold). These data demonstrate that the MKK7β and MKK7γ isoforms are more active than MKK7α isoforms (under basal conditions and following activation) but that the MKK7α isoforms are more inducible following stimulation. The low basal activity of the MKK7α isoforms accounts, in part, for their greater activation.

Together, these data demonstrate that the activity of MKK7 isoforms is affected by alternative splicing of the NH2-terminal region but not by alternative splicing of the COOH-terminal region. However, the inclusion or exclusion of exon 2 within the NH2-terminal region of MKK7 (β and γ isoforms) did not alter MKK7 protein kinase activity in these assays.

The NH2-terminal region of MKK7β interacts with JNK.

The observation that activities of the MKK7α isoforms were lower than those of the MKK7β and MKK7γ isoforms suggests that these MKK7 isoforms may differentially interact with the substrate JNK. To test this hypothesis, we examined the interaction of MKK7α and MKK7β isoforms with JNK1 following expression in COS-7 cells. We precipitated the MKK7 protein kinases from cell lysates, and examined the presence of JNK1 in the precipitates by immunoblot analysis (Fig. 5A). These assays demonstrated that MKK7β isoforms, but not MKK7α isoforms, coprecipitated with JNK. This binding interaction may contribute to the higher activities of MKK7β isoforms than of MKK7α isoforms (Fig. 4).

FIG. 5.

Interaction of JNK with MKK7 isoforms. (A) Selective binding of MKK7β isoforms to JNK. Epitope-tagged JNK1 and either GST (Control) or GST-tagged MKK7α1, MKK7α2, MKK7β1, or MKK7β2 were expressed in COS-1 cells. Protein expression levels, monitored by immunoblot analysis of the cell lysates, were similar in all transfections. The MKK7 protein kinases were isolated from cell extracts by incubation with GSH-agarose. The binding of JNK1 was examined by immunoblot analysis with an antibody to the HA epitope tag. (B) JNK binds to the NH2 terminus of MKK7β. Bacterially expressed GST (Control) or a GST fusion protein (residues 1 to 73 of MKK7β) was immobilized on GSH-agarose and incubated with extracts prepared from COS-7 cells expressing epitope-tagged JNK1. The agarose beads were washed, and the amount of bound JNK1 was examined by immunoblot analysis.

The MKK7β and MKK7α isoforms differ structurally by virtue of an NH2-terminal extension that is present in MKK7β but not MKK7α. This NH2-terminal region of MKK7β therefore accounts for the binding interaction observed between JNK and MKK7β. The mechanism by which this NH2-terminal region alters the binding to JNK is unclear. The NH2-terminal region may act indirectly by altering the conformation of another region of the MKK7 protein kinase that binds JNK. Alternatively, JNK may bind directly to the NH2 terminus of MKK7β. To test the latter hypothesis, we expressed the NH2-terminal region of MKK7β (residues 1 to 73) as a GST fusion protein in bacteria. This recombinant protein was found to bind JNK (Fig. 5B). These data demonstrate that the MKK7β isoforms bind JNK and indicate that this is mediated, in part, by a direct interaction between JNK and the NH2-terminal region of MKK7β that is absent in MKK7α. The presence of a region in the NH2 terminus of MKK7β that binds JNK is consistent with previous studies that have implicated the NH2-terminal region of MAPKK in the determination of signaling specificity to distinct MAPK isoforms (4).

Regulation of MKK7 isoforms by MAPKKKs.

The protein kinases MEKK1, MLK3, and DLK preferentially activate JNK (32, 33, 50, 62, 74, 75, 86), MEKK3 activates both JNK and ERK (6, 11, 15), while MEKK4 has been reported to activate both JNK and p38 MAPK (25, 71). Since MEKK1 causes differential activation of MKK7 isoforms (Fig. 4), we examined whether other MAPKKKs, including members of the MEKK and MLK groups (19), could also cause differential activation of MKK7 isoforms.

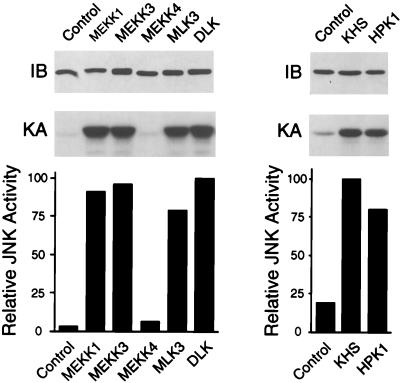

To test the effects of various MAPKKK isoforms on activation of MKK7 isoforms, we examined MEKK and MLK protein kinases in cotransfection assays. Control experiments demonstrated that MEKK1, MEKK3, MLK3, and DLK caused similar increases in JNK activity (Fig. 6). However, MEKK4 caused no JNK activation (Fig. 6), in contrast to a previous report (25). Instead, MEKK4 selectively activated p38 MAPK (data not shown). These data identify MEKK4 as an activator of the p38 MAPK pathway (71).

FIG. 6.

Effect of MEKK and STE20 protein kinases on JNK activation. To examine the ability of MAPKKKs and STE20 homologs to activate JNK1, COS-7 cells were cotransfected with a mammalian expression vector encoding HA-tagged JNK1 together with an empty expression vector (Control) or an expression vector encoding either MEKK1, MEKK3, MEKK4, MLK3, DLK, KHS, or HPK1. The expression of JNK1 was examined by immunoblot (IB) analysis using a monoclonal antibody to the HA epitope tag. JNK1 was immunoprecipitated and its activity was measured in the immune complex by a protein kinase assay (KA) using recombinant GST–c-Jun as the substrate. The phosphorylated c-Jun was detected after SDS-PAGE by autoradiography and was quantitated by PhosphorImager analysis. JNK activity is presented as relative protein kinase activity. The levels of JNK activation caused by MEKK1, MEKK3, MEKK4, MLK3, DLK, KHS, and HPK1 were 28-, 29-, 2.0-, 24-, 30-, 5.3-, and 4.3-fold, respectively. Similar results were obtained in three separate experiments.

To compare the levels of activation of MKK4 and MKK7 isoforms by different MAPKKKs, we performed coupled protein kinase assays. MKK4 and MKK7 activity was detected with bacterially expressed JNK1 as the substrate, and JNK activation was assessed by measurement of the phosphorylation of c-Jun. Protein immunoblot analysis demonstrated that similar amounts of MKK7 were examined in all assays (Fig. 7). While MEKK1, MEKK3, MLK3, and DLK efficiently activated JNK (Fig. 6), these MAPKKKs displayed differences in the ability to activate MKK4 and MKK7 isoforms. For example, MEKK1 was the most potent activator of MKK7 isoforms, whereas MEKK3 was the most potent activator of MKK4 isoforms (Fig. 7). MEKK1, MLK3 and DLK caused similar increases in MKK4 and MKK4β activity. The extent of activation of MKK7 isoforms by MEKK3 was largest for MKK7α1, while the MKK7β2 isoform was only weakly activated by MEKK3. However, the MKK7β isoforms were activated by the mixed-lineage kinases DLK and MLK3 more strongly than by MEKK3. The decreased electrophoretic mobility of MKK7α2 (and MKK7β isoforms to a lesser extent) caused by MEKK1 and MEKK3 was not caused by MLK3 or DLK (Fig. 7). Together, these data demonstrate that MEKK1, MEKK3, MLK3, and DLK are capable of selectively activating MKK4 and MKK7 protein kinase isoforms.

FIG. 7.

Activation of MKK4 and MKK7 protein kinases by MAPKKKs. To examine the abilities of MAPKKKs to activate MKK isoforms, COS-7 cells were cotransfected with mammalian expression vectors encoding tagged MKK7α1, MKK7α2, MKK7β1, MKK7β2, MKK4, or MKK4β together with either an empty expression vector (Control) or an expression vector encoding MEKK1, MEKK3, MEKK4, MLK3, or DLK. MKK protein expression was monitored by immunoblot (IB) analysis. The MKK4 and MKK7 isoforms were immunoprecipitated, and their activities were measured by a coupled protein kinase assay (KA) using recombinant JNK1 and c-Jun as substrates. The phosphorylated c-Jun was detected after SDS-PAGE by autoradiography and was quantitated by PhosphorImager analysis. MAPKK activity is presented as relative protein kinase activity. The levels of MAPKK activation caused by MEKK1, MEKK3, MEKK4, MLK3, and DLK were 27-, 19-, 1.8-, 5.0-, and 7.0-fold (MKK7α1); 32-, 10-, 1.4-, 13-, and 6.5-fold (MKK7α2); 5.6-, 2.0-, 0.3-, 4.2-, and 4.5-fold (MKK7β1); 13-, 2.6-, 1.3-, 7.5-, and 5.1-fold (MKK7β2); 42-, 88-, 2.0-, 38-, and 39-fold (MKK4); and 53-, 77-, 2.2-, 48-, and 36-fold (MKK4β), respectively. Similar results were obtained in three separate experiments.

Consistent with the observation that MEKK4 did not activate JNK (Fig. 6), we found that MEKK4 did not activate any of the MKK4 or MKK7 isoforms (Fig. 7).

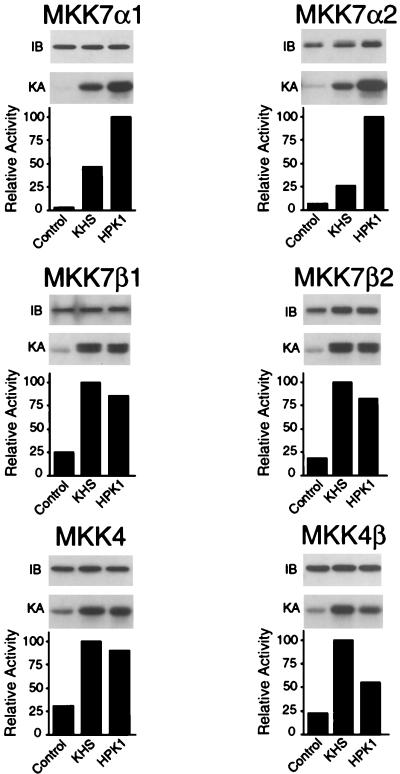

Regulation of MKK4 and MKK7 isoforms by STE20-like protein kinases.

Several STE20-like protein kinases have been reported to be capable of activating the JNK pathway (19). Among them, KHS (78) and HPK1 (37, 41, 79) appear to be specific for the JNK signaling pathway. We therefore examined the abilities of KHS and HPK1 to activate MKK4 and MKK7 isoforms. Cells were transiently transfected with expression vectors encoding epitope-tagged MKK4 or MKK7 isoforms, together with expression vectors for either KHS or HPK1. Control experiments demonstrated that the KHS and HPK1 protein kinases caused similar levels of JNK activation (Fig. 6). The amount of MKK4 and MKK7 protein expression was examined by Western blot analysis (Fig. 8). The MKK4 and MKK7 protein kinases were immunoprecipitated, and their activities were measured by a coupled protein kinase assay. KHS and HPK1 caused similar increases in the activities of MKK7β1, MKK7β2, and MKK4. However, differences in the activation of MKK4β and MKK7α isoforms were detected. Indeed, HPK1 was the most potent activator of MKK7α1 and MKK7α2, while KHS was the most potent activator of MKK4β.

FIG. 8.

Activation of MKK4 and MKK7 protein kinases by STE20 homologs. To examine the abilities of KHS and HPK1 to activate MKK7 isoforms, COS-7 cells were cotransfected with Flag-tagged MKK7α1, MKK7α2, MKK7β1, MKK7β2, MKK4, or MKK4β together with an empty expression vector (Control) or an expression vector for either KHS or HPK1. Protein expression was monitored by immunoblot (IB) analysis. Flag-tagged MKKs were immunoprecipitated, and MKK activity was measured in the immune complex by a coupled protein kinase assay (KA) using recombinant JNK1 and c-Jun as substrates. The phosphorylated c-Jun was detected after SDS-PAGE by autoradiography and quantitated by PhosphorImager analysis. MAPKK activity is presented as relative protein kinase activity. The levels of MAPKK activation caused by KHS and HPK were 15- and 31-fold (MKK7α1); 3.9- and 15-fold (MKK7α2); 4.0- and 3.5-fold (MKK7β1); 5.4- and 4.4-fold (MKK7β2); 3.2- and 2.9-fold (MKK4); and 4.4- and 2.4-fold (MKK4β), respectively. Similar results were obtained in three separate experiments.

Regulation of MKK4 and MKK7 protein kinases by extracellular stimuli.

To identify the nature of the MKKs involved in the regulation of the JNK cascade in response to specific extracellular stimuli, we examined the effects of environmental stresses and proinflammatory cytokines on activation of MKK4 and MKK7 protein kinase activities. We found that MKK4 and MKK7 isoforms were selectively regulated by upstream kinases (Fig. 7 and 8). Therefore, we examined the effects of UV-C radiation, anisomycin, TNF-α, and IL-1α on the regulation of MKK7 and MKK4 isoforms. The MKK4 and MKK7 isoforms were isolated, and their activity was measured by a coupled kinase assay. TNFα and IL-1α selectively activated the MKK7 isoforms and only weakly activated MKK4 (Fig. 9). In contrast, UV-C radiation and anisomycin caused selective activation of MKK4 compared to MKK7 (Fig. 9). These data indicate that the MKK4 and MKK7 isoforms are selectively regulated by specific extracellular stimuli. This selective regulation is consistent with the genetic evidence for nonredundant roles of MKK4 and MKK7 in Drosophila and mammals (38).

FIG. 9.

Regulation of MKK4 and MKK7 protein kinases by extracellular stimuli. 293 cells were transiently transfected with expression vectors (pEBG) encoding either MKK7α1, MKK7α2, MKK7β1, MKK7β2, MKK4, or MKK4β; 36 h after transfection, the cells were untreated (Control) or treated with UV-C (UV; 80 J/m2), anisomycin (ANISO; 5 μg/ml), TNF-α (20 ng/ml), or IL-1α (2 ng/ml). The cells were harvested after incubation at 37°C (30 min). MKK4 and MKK7 were isolated by using GSH-Sepharose beads, and the MKK activity was measured by a coupled protein kinase assay using recombinant JNK1 and c-Jun as substrates. The radioactivity incorporated into c-Jun was quantitated after SDS-PAGE by PhosphorImager analysis. MAPKK activity is presented as relative protein kinase activity. The levels of MAPKK activation caused by UV, anisomycin, TNF-α, and IL-1α were 1.4-, 1.5-, 2.2-, and 1.9-fold (MKK7α1); 2.8-, 1.8-, 3.9-, and 2.5-fold (MKK7α2); 2.4-, 2.1-, 2.5-, and 4.1-fold (MKK7β1); 2.0-, 1.7-, 2.8-, and 2.9-fold (MKK7β2); 4.7-, 3.2-, 0.9-, and 0.9-fold (MKK4); and 2.6-, 2.3-, 0.9-, and 0.9-fold (MKK4β), respectively. Similar results were obtained in three separate experiments.

Subcellular localization of MKK4 and MKK7 protein kinases.

JNK has been reported to accumulate in the nucleus upon treatment of cells with stimuli known to activate the JNK signaling pathway (8, 40, 51). We therefore examined the subcellular localization of MKK4 and MKK7 by immunofluorescence analysis. These studies demonstrated that the endogenous MKK4 and MKK7 protein kinases were distributed in both the cytoplasm and the nucleus (Fig. 10A). Exposure of the cells to UV-C radiation or treatment with IL-1α did not cause marked changes in the distribution of the endogenous MKK4 or MKK7 protein kinases.

FIG. 10.

Subcellular distribution of MAPKK isoforms. (A) Endogenous MKK4 and MKK7 (red) were detected by immunofluorescence analysis using primary antibodies specific for these MKK isoforms. The cells were untreated (Control) or treated (30 min) with UV (80 J/m2) or IL-1α (10 ng/ml). DNA was visualized by staining with DAPI (blue). The scale bar (white) represents 20 μm. (B) Epitope-tagged MKK7α1, MKK7α2, MKK7β1, MKK7β2, MKK4, MKK4β, MEK1, and ΔN3-MEK1-EE were detected by using a primary monoclonal antibody to the epitope tag and a Texas red-labeled secondary antibody. The scale bar (white) represents 10 μm.

To examine the subcellular localization of individual MKK4 and MKK7 isoforms, we transfected cells with epitope-tagged MKK4 and MKK7 and also performed control experiments with epitope-tagged wild-type MEK1 and constitutively activated MEK1 (ΔN3-MEK1-EE). The activated MEK1 was constructed by replacing the two activating phosphorylation sites with glutamic acid residues and by deletion of the NH2-terminal NES (22, 23, 39, 47). Immunofluorescence analysis demonstrated that, as expected, wild-type MEK1 was restricted to the cytoplasm, while activated MEK1 was present in the nucleus (Fig. 10B). Under the same experimental conditions, the MKK4 and MKK7 isoforms were detected at low levels in the cytoplasm and appeared to preferentially accumulate in the nucleus (Fig. 10B). The higher level of nuclear accumulation of the transfected MAPKK than of the endogenous MAPKK may reflect the overexpression of the recombinant proteins. Exposure of the cells to UV-C radiation or treatment with IL-1α did not induce changes in the localization of MKK4 or MKK7 (data not shown).

Effect of nuclear exclusion on the activity of MKK7.

The distribution of the MKK7 protein in the cytoplasm and the nucleus differs from that described for the ERK MAPK activator MEK1. While the endogenous MKK7 protein appears to preferentially accumulate in the nucleus (Fig. 10A), MEK1 is excluded from the nucleus. The mechanism of nuclear exclusion is mediated by the presence of an NES in the NH2-terminal region of MEK1 (23). Disruption of the NES causes nuclear accumulation of MEK1 and marked potentiation of signaling (22). These data suggest that the NES may be important for the normal control of MEK1 activity.

To test whether the presence of an NES would affect the properties of MKK7, we fused the NES of MEK1 to the NH2-terminal region of MKK7β (Fig. 11A). Immunofluorescence analysis demonstrated that while MKK7β2 preferentially accumulated in the nucleus, the NES-MKK7β2 was excluded from the nucleus (Fig. 11B). Similar results were obtained in experiments using MKK7β1 and NES-MKK7β1 (data not shown).

FIG. 11.

Effect of an NES on the properties of MKK7. (A) Schematic representation of MKK7β and NES-MKK7β. Both proteins were constructed with an NH2-terminal Flag epitope (grey box). The nuclear export signal (NES) of MEK1 (residues 32 to 51) was inserted following the Flag epitope to create NES-MKK7β. (B) The MKK7 proteins and HA-JNK1 were expressed in COS-7 cells. Transfected cells were identified by immunofluorescence analysis using antibody M2, which binds the Flag epitope on the MKK7 proteins. Activated JNK in the transfected cells was examined by using an antibody to phospho-JNK [JNK(P)]. The MKK7 (red) and phospho-JNK (green) were detected with secondary antibodies conjugated to Texas red and fluorescein, respectively. DNA was visualized by staining with DAPI (blue). The scale bar (white) represents 10 μm. (C) Regulation of MKK7β2 and NES-MKK7β2 by extracellular stimuli. COS-7 cells expressing MKK7β2 or NES-MKK7β2 were untreated (Control) or treated (30 min) with UV-C (80 J/m2) or IL-1α (10 ng/ml). The expression of MKK7 was examined by immunoblot (IB) analysis using the Flag-specific monoclonal antibody M2. MKK7 activity was measured in a coupled protein kinase assay (KA). The radioactivity incorporated into c-Jun was quantitated after SDS-PAGE by PhosphorImager analysis. MAPKK activity is presented as relative protein kinase activity. The levels of MAPKK activation caused by UV and IL-1α were 3.0- and 3.7-fold (MKK7β2) and 1.5- and 1.8-fold (NES-MKK7β2), respectively. (D) Activation of JNK1 by MKK7β and NES-MKK7β. COS-7 cells were cotransfected with plasmids expressing HA-tagged JNK1 together with an empty vector (Control) or an expression vector encoding Flag-tagged MKK7β1, NES-MKK7β1, MKK7β2, or NES-MKK7β2. The expression of MKK7 and JNK1 was monitored by immunoblot (IB) analysis using antibodies to Flag and HA, respectively. JNK1 activity was measured by immune complex kinase assay (KA) using the substrate c-Jun. The radioactivity incorporated into c-Jun was quantitated after SDS-PAGE by PhosphorImager analysis. JNK activity is presented as relative protein kinase activity. The levels of JNK activation observed for MKK7β1, NES-MKK7β1, MKK7β2, and NES-MKK7β2 were 21-, 27-, 25-, and 31-fold, respectively.

The presence of an NES may alter the activation of MKK7 by cytokines or by environmental stresses. We therefore examined the effects of UV-C radiation and IL-1α on the activation of MKK7β2 and NES-MKK7β2 (Fig. 11C), using a coupled protein kinase assay to measure the MKK7 protein kinase activity. Western blot analysis demonstrated the expression of similar amounts of MKK7β2 and NES-MKK7β2. Protein kinase assays demonstrated that both MKK7β2 and NES-MKK7β2 were activated by UV-C radiation and IL-1α. These data demonstrated that extracellular stimuli can activate MKK7 proteins that are preferentially located either in the nucleus (MKK7β2) or in the cytoplasm (NES-MKK7β2).

The presence of an NES might also alter the effect of MKK7 on JNK. To examine JNK activation, we performed immunofluorescence analysis using an antibody that binds to JNK phosphorylated on Thr-183 and Tyr-185. Control experiments demonstrated that the exposure of cells to UV-C radiation caused increased staining by the phospho-JNK antibody (data not shown). Expression of either MKK7β2 or NES-MKK7β2 also caused increased staining by the phospho-JNK antibody. Immunofluorescence analysis demonstrated that the activated JNK accumulated in the nucleus (Fig. 11B). Quantitative assays of protein kinase activity using biochemical methods demonstrated that MKK7β1, MKK7β2, NES-MKK7β1, and NES-MKK7β2 caused a similar level of JNK activation (Fig. 11D). These data indicated that recombinant MKK7 molecules that are preferentially located in the nucleus (MKK7β2) or in the cytoplasm (NES-MKK7β2) are equally capable of activating the JNK MAPK. This observation contrasts with the previous finding that constitutively nuclear MEK1 mutants cause enhanced signaling by the ERK MAPK (22).

DISCUSSION

The genes that encode the JNK activators MKK4 and MKK7 are located on mouse chromosome 11.

The MKK7 gene was mapped to mouse chromosome 11 (Fig. 2). It is interesting that the MKK4 gene is also located on this chromosome (81). The localization of both of the genes that encode JNK activators on the same mouse chromosome suggests that these genes might be linked. This is an interesting possibility because MKK4 is a candidate tumor suppressor gene that is mutated in certain tumors (73), suggesting that the MKK7 gene may also be a target of genetic alterations in disease processes.

Although the mouse MKK4 and MKK7 genes reside on the same chromosome, it does not appear that this relationship is present in all species. Thus, in Drosophila, the D-MKK4 (29) and D-MKK7 (26) genes are located on different chromosomes. Indeed, it appears that the D-MKK3 gene (and not the D-MKK4 gene) is tightly linked to the D-MKK7 gene in the fly (29). The colocalization of the genes that encode the JNK activators MKK4 and MKK7 on one mouse chromosome is therefore not evolutionarily conserved.

The MKK7 gene encodes a group of protein kinases.

The MKK7 gene includes 14 exons. Alternative splicing leads to the inclusion or exclusion of exons located in the 5′ and 3′ regions of the gene, resulting in the expression of a group of MKK7 isoforms that differ in their NH2 and COOH termini (Fig. 3). These MKK7 protein kinase isoforms act as activators of JNK MAPK. Comparative studies demonstrate that the MKK7 isoforms differ in the extent of activation in response to different upstream components of the JNK signaling pathway (Fig. 7 to 9).

Sequences in the NH2 termini of MAPKK protein kinases have been reported to mediate specific interactions with other components of MAPK pathways (4). Similarly, specificity determinants have been identified in the NH2- and COOH-terminal regions of MAPK pathway components, including PBS2 and MEKK1 (60, 69, 85). It is therefore interesting that multiple cDNA clones with different 5′ regions have been reported for MKK3, MKK4, MKK5, and MKK6 (13, 17, 28, 54, 61, 65, 90). Whether these different cDNA clones correspond to fully processed mRNA is unclear because the corresponding genes have not been characterized. In contrast, it is established that the usage of alternative exons within the MKK7 gene leads to the formation of multiple protein kinase isoforms (Fig. 3). It is therefore likely that the expression of a group of alternatively spliced isoforms is a common property of MAPKK genes. The possible role of the divergent NH2-terminal sequences of MAPKK isoforms as specificity determinants for MAPKK function (4) suggests that different MAPKK isoforms may have different physiological functions. In this study, we demonstrate that the NH2-terminal extension that is present in the MKK7β isoforms, but not MKK7α isoforms, binds to the substrate JNK and may account, in part, for the differences in activity between these MKK7 isoforms (Fig. 4 and 5). This binding to JNK is consistent with the presence of consensus primary sequence motifs for JNK interaction (Leu-Xaa-Leu) in the NH2-terminal region of MKK7β (88).

The MKK7 group of protein kinases are present in the cytoplasm and the nucleus.

Studies of the ERK MAPK signaling pathway demonstrate that the ERK MAPKs are present in the cytoplasm of quiescent cells and that the ERKs accumulate in the nucleus following activation (9, 27, 66). Similarly, it has been reported by several groups that JNK accumulates in the nucleus following activation (8, 40, 51). In contrast to the activation-induced nuclear accumulation of the ERK MAPKs, the ERK activators MEK1 and MEK2 are cytoplasmic enzymes (1). A nuclear export sequence in the NH2-terminal region of MEK1 appears to mediate rapid export out of the nucleus and, therefore, the accumulation of MEK1 in the cytoplasm (22, 23, 39). In contrast, we found that the JNK activator MKK7 was present in both the cytoplasm and the nucleus (Fig. 10). This nuclear location was observed for endogenous MKK7 (Fig. 10A) and for multiple MKK7 isoforms (Fig. 10B). Nuclear localization was also observed for the JNK activator MKK4. The mechanism that accounts for the nuclear location of MKK4 and MKK7 is unclear because the sequences of these protein kinases do not include an obvious nuclear localization sequence. It is possible that the absence of an NES may contribute to the localization of MKK4 and MKK7 in the nucleus. Thus, the subcellular location of the JNK activators MKK4 and MKK7 differs from that of the ERK activators MEK1 and MEK2.

Recent studies indicate that the subcellular organization of the p38 MAPK pathway differs from that of both the ERK and JNK signaling pathways. The major p38 MAPK activators (MKK3 and MKK6), like the activators of ERK (MEK1 and MEK2), are both preferentially located in the cytoplasm (5). However, unlike ERK, which exhibits activation-induced redistribution from the cytoplasm to the nucleus, the p38 MAPK is prelocalized in the nucleus and is rapidly exported to the cytoplasm upon activation (5). The mechanism of nuclear export appears to be mediated, at least in part, by the nuclear substrate MAPKAP kinase 2, which is also exported from the nucleus following activation (5, 16). Together, these data indicate that there are marked differences between the subcellular organization of the ERK, JNK, and p38 MAPK pathways.

The presence of MKK4 and MKK7 in the nucleus suggests that these MAPKK may activate JNK in this compartment of the cell. Indeed, Mizukami et al. (51) have recently reported that JNK may be activated in the nucleus during ischemia-reperfusion injury to the heart. However, it is possible that MKK4 and MKK7 may also activate JNK in the cytoplasm. Evidence in favor of this hypothesis was obtained from studies of mutated MKK7 protein kinases that are excluded from the nucleus (Fig. 11). We found that cytoplasmic MKK7 protein kinases efficiently activated JNK in vivo (Fig. 11D) and that the activated JNK in these cells accumulated in the nucleus (Fig. 11B). These data indicate that MKK7 (and possibly MKK4) can activate JNK in the cytoplasm and that the activated JNK redistributes from the cytoplasm to the nucleus.

The presence of MKK4 and MKK7 in the nuclei of quiescent and stimulated cells indicates that these MKK isoforms may also be activated in the nucleus. Fanger et al. have reported that MEKK1 is located in the nucleus (20). However, other MAPKKK that activate the JNK signaling pathway appear to be preferentially located in the cytoplasm. For example, MLK2 is detected in punctate structures along microtubules (56), MEKK2 and MEKK3 are located on Golgi-associated vesicles (20), while MLK3 and DLK were identified in the cytoplasm by immunofluorescence microscopy (data not shown). The cytoplasmic location of these MAPKKKs raises questions concerning the mechanism of action of nuclear MKK4 and MKK7. Clearly MAPKKKs and MAPKKs must interact and therefore have to be present in the same cellular compartment. The simplest explanation is that although MKK4 and MKK7 are present in the nucleus, a cytoplasmic population of molecules may arise from rapid shuttling across the nuclear membrane. This model implies that some MAPKKKs (e.g., MEKK1) may directly activate MKK4 and MKK7 in the nucleus, whereas others (e.g., MLK3) may activate a cytoplasmic population of MKK4 and MKK7 that rapidly shuttles to the nucleus.

Further studies are required to identify the mechanisms used to determine the subcellular distribution of components of the JNK signaling pathway. Such mechanisms may include scaffold proteins that interact with JNK and MKK7 (82). The expression of scaffold proteins may contribute to the selective control of JNK signaling in specialized differentiated cells.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank N. Ahn, J. Avruch, J. Blenis, S. Gutkind, H. Saito, U. Siebenlist, and T. Tan for providing reagents, and we thank K. Gemme for administrative assistance.

This work was supported by grant CA53896 from the National Cancer Institute. R.J.D. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahn N G, Seger R, Krebs E G. The mitogen-activated protein kinase activator. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1992;4:992–999. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(92)90131-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anafi M, Kiefer F, Gish G D, Mbamalu G, Iscove N N, Pawson T. SH2/SH3 adaptor proteins can link tyrosine kinases to a Ste20-related protein kinase, HPK1. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:27804–27811. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.44.27804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bagrodia S, Derijard B, Davis R J, Cerione R A. Cdc42 and PAK-mediated signaling leads to Jun kinase and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:27995–27998. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.47.27995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bardwell L, Thorner J. A conserved motif at the amino termini of MEKs might mediate high-affinity interaction with the cognate MAPKs. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:373–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ben-Levy R, Hooper S, Wilson R, Paterson H F, Marshall C J. Nuclear export of the stress-activated protein kinase p38 mediated by its substrate MAPKAP kinase-2. Curr Biol. 1998;8:1049–1057. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70442-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blank J L, Gerwins P, Elliott E M, Sather S, Johnson G L. Molecular cloning of mitogen-activated protein/ERK kinase kinases (MEKK) 2 and 3. Regulation of sequential phosphorylation pathways involving mitogen-activated protein kinase and c-Jun kinase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:5361–5368. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.10.5361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burbelo P D, Drechsel D, Hall A. A conserved binding motif defines numerous candidate target proteins for both Cdc42 and Rac GTPases. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:29071–29074. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.49.29071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cavigelli M, Dolfi F, Claret F-X, Karin M. Induction of c-fos expression through JNK-mediated TCF/Elk-1 phosphorylation. EMBO J. 1995;14:5957–5964. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00284.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen R H, Sarnecki C, Blenis J. Nuclear localization and regulation of erk- and rsk-encoded protein kinases. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:915–927. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.3.915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coso O A, Chiariello M, Yu J C, Teramoto H, Crespo P, Xu N, Miki T, Gutkind J S. The small GTP-binding proteins Rac1 and Cdc42 regulate the activity of the JNK/SAPK signaling pathway. Cell. 1995;81:1137–1146. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deacon K, Blank J L. Characterization of the mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 4 (MKK4)/c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase 1 and MKK3/p38 pathways regulated by MEK kinases 2 and 3. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:14489–14496. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.22.14489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dérijard B, Hibi M, Wu I-H, Barrett T, Su B, Deng T, Karin M, Davis R J. JNK1: a protein kinase stimulated by UV light and Ha-Ras that binds and phosphorylates the c-Jun activation domain. Cell. 1994;76:1025–1037. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90380-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dérijard B, Raingeaud J, Barrett T, Wu I-H, Han J, Ulevitch R J, Davis R J. Independent human MAP kinase signal transduction pathways defined by MEK and MKK isoforms. Science. 1995;267:682–685. doi: 10.1126/science.7839144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dorow D S, Devereux L, Dietzsch E, De Kretser T. Identification of a new family of human epithelial protein kinases containing two leucine/isoleucine-zipper domains. Eur J Biochem. 1993;213:701–710. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ellinger-Ziegelbauer H, Brown K, Kelly K, Siebenlist U. Direct activation of the stress-activated protein kinase (SAPK) and extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase (ERK) pathways by an inducible mitogen-activated protein Kinase/ERK kinase kinase 3 (MEKK) derivative. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:2668–2674. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.5.2668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Engel K, Kotlyarov A, Gaestel M. Leptomycin B-sensitive nuclear export of MAPKAP kinase 2 is regulated by phosphorylation. EMBO J. 1998;17:3363–3371. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.12.3363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.English J M, Vanderbilt C A, Xu S, Marcus S, Cobb M H. Isolation of MEK5 and differential expression of alternatively spliced forms. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:28897–28902. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.48.28897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fan G, Merritt S E, Kortenjann M, Shaw P E, Holzman L B. Dual leucine zipper-bearing kinase (DLK) activates p46SAPK and p38MAPK but not ERK2. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:24788–24793. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.40.24788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fanger G R, Gerwins P, Widmann C, Jarpe M B, Johnson G L. MEKKs, GCKs, MLKs, PAKs, TAKs, and Tpls: upstream regulators of the c-Jun amino-terminal kinases. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1997;7:67–74. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(97)80111-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fanger G R, Johnson N L, Johnson G L. MEK kinases are regulated by EGF and selectively interact with Rac/Cdc42. EMBO J. 1997;16:4961–4972. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.16.4961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Foltz I N, Gerl R E, Wieler J S, Luckach M, Salmon R A, Schrader J W. Human mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 7 (MKK7) is a highly conserved c-Jun N-terminal Kinase/Stress-activated protein kinase (JNK/SAPK) activated by environmental stresses and physiological stimuli. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:9344–9351. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.15.9344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fukuda M, Gotoh I, Adachi M, Gotoh Y, Nishida E. A novel regulatory mechanism in the mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase cascade. Role of nuclear export signal of MAP kinase kinase. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:32642–32648. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.51.32642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fukuda M, Gotoh I, Gotoh Y, Nishida E. Cytoplasmic localization of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase directed by its NH2-terminal, leucine-rich short amino acid sequence, which acts as a nuclear export signal. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:20024–20028. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.33.20024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ganiatsas S, Kwee L, Fujiwara Y, Perkins A, Ikeda T, Labow M A, Zon L I. SEK1 deficiency reveals mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade crossregulation and leads to abnormal hepatogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6881–6886. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gerwins P, Blank J L, Johnson G L. Cloning of a novel mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase, MEKK4, that selectively regulates the c-Jun amino terminal kinase pathway. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:8288–8295. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.13.8288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Glise B, Bourbon H, Noselli S. hemipterous encodes a novel Drosophila MAP kinase kinase, required for epithelial cell sheet movement. Cell. 1995;83:451–461. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90123-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gonzalez F A, Seth A, Raden D L, Bowman D S, Fay F S, Davis R J. Serum-induced translocation of mitogen-activated protein kinase to the cell surface ruffling membrane and the nucleus. J Cell Biol. 1993;122:1089–1101. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.5.1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Han J, Lee J-D, Jiang Y, Li Z, Feng L, Ulevitch R J. Characterization of the structure and expression of a novel MAP kinase kinase (MKK6) J Biol Chem. 1996;271:2886–2891. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.6.2886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Han Z S, Enslen H, Hu X, Meng X, Wu I-H, Barrett T, Davis R J, Ip Y T. A conserved p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway regulates Drosophila immunity gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3527–3539. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.6.3527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heng H H, Squire J, Tsui L C. High-resolution mapping of mammalian genes by in situ hybridization to free chromatin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:9509–9513. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.20.9509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heng H H, Tsui L C. Modes of DAPI banding and simultaneous in situ hybridization. Chromosoma. 1993;102:325–332. doi: 10.1007/BF00661275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hirai S, Izawa M, Osada S, Spyrou G, Ohno S. Activation of the JNK pathway by distantly related protein kinases, MEKK and MUK. Oncogene. 1996;12:641–650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hirai S, Katoh M, Terada M, Kyriakis J M, Zon L I, Rana A, Avruch J, Ohno S. MST/MLK2, a member of the mixed lineage kinase family, directly phosphorylates and activates SEK1, an activator of c-Jun N-terminal kinase/stress-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:15167–15173. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.24.15167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hirai S, Noda K, Moriguchi T, Nishida E, Yamashita A, Deyama T, Fukuyama K, Ohno S. Differential activation of two JNK activators, MKK7 and SEK1, by MKN28-derived nonreceptor serine/threonine kinase/mixed lineage kinase 2. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:7406–7412. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.13.7406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ho S N, Hunt H D, Horton R M, Pullen J K, Pease L R. Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene. 1989;77:51–59. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holland P M, Suzanne M, Campbell J S, Noselli S, Cooper J A. MKK7 is a stress-activated mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase functionally related to hemipterous. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:24994–24998. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.40.24994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hu M C, Qiu W R, Wang X, Meyer C F, Tan T H. Human HPK1, a novel human hematopoietic progenitor kinase that activates the JNK/SAPK kinase cascade. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2251–2264. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.18.2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ip Y T, Davis R J. Signal transduction by the c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK)—from inflammation to development. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10:205–219. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jaaro H, Rubinfeld H, Hanoch T, Seger R. Nuclear translocation of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK1) in response to mitogenic stimulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3742–3747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kawasaki H, Moriguchi T, Matsuda S, Li H Z, Nakamura S, Shimohama S, Kimura J, Gotoh Y, Nishida E. Ras-dependent and Ras-independent activation pathways for the stress-activated-protein-kinase cascade. Eur J Biochem. 1996;241:315–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.00315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kiefer F, Tibbles L A, Anafi M, Janssen A, Zanke B W, Lassam N, Pawson T, Woodgett J R, Iscove N N. HPK1, a hematopoietic protein kinase activating the SAPK/JNK pathway. EMBO J. 1996;15:7013–7025. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kyriakis J M, Woodgett J R, Avruch J. The stress-activated protein kinases. A novel ERK subfamily responsive to cellular stress and inflammatory cytokines. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1995;766:303–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb26683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lange-Carter C A, Pleiman C M, Gardner A M, Blumer K J, Johnson G L. A divergence in the MAP kinase regulatory network defined by MEK kinase and Raf. Science. 1993;260:315–319. doi: 10.1126/science.8385802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lawler S, Cuenda A, Goedert M, Cohen P. SKK4, a novel activator of stress-activated protein kinase-1 (SAPK1/JNK) FEBS Lett. 1997;414:153–158. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00990-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lin A, Minden A, Martinetto H, Claret F X, Lange-Carter C, Mercurio F, Johnson G L, Karin M. Identification of a dual specificity kinase that activates the Jun kinases and p38-Mpk2. Science. 1995;268:286–290. doi: 10.1126/science.7716521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lu X, Nemoto S, Lin A. Identification of c-Jun NH2-terminal protein kinase (JNK)-activating kinase 2 as an activator of JNK but not p38. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:24751–24754. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.40.24751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mansour S J, Matten W T, Hermann A S, Candia J M, Rong S, Fukasawa K, Vande Woude G F, Ahn N G. Transformation of mammalian cells by constitutively activated MAP kinase kinase. Science. 1994;265:966–970. doi: 10.1126/science.8052857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meier R, Rouse J, Cuenda A, Nebreda A R, Cohen P. Cellular stresses and cytokines activate multiple mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase homologues in PC12 and KB cells. Eur J Biochem. 1996;236:796–805. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.00796.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Minden A, Lin A, Claret F X, Abo A, Karin M. Selective activation of the JNK signaling cascade and c-Jun transcriptional activity by the small GTPases Rac and Cdc42Hs. Cell. 1995;81:1147–1157. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Minden A, Lin A, McMahon M, Lange-Carter C, Derijard B, Davis R J, Johnson G L, Karin M. Differential activation of ERK and JNK mitogen-activated protein kinases by Raf-1 and MEKK. Science. 1994;266:1719–1723. doi: 10.1126/science.7992057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mizukami Y, Yoshioka K, Morimoto S, Yoshida K. A novel mechanism of JNK1 activation. Nuclear translocation and activation of JNK1 during ischemia and reperfusion. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:16657–16662. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.26.16657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moriguchi T, Kawasaki H, Matsuda S, Gotoh Y, Nishida E. Evidence for multiple activators for stress-activated protein kinase/c-Jun amino-terminal kinases. Existence of novel activators. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:12969–12972. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.22.12969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moriguchi T, Kuroyanagi N, Yamaguchi K, Gotoh Y, Irie K, Kano T, Shirakabe K, Muro Y, Shibuya H, Matsumoto K, Nishida E, Hagiwara M. A novel kinase cascade mediated by mitogen-activated protein kinase 6 and MKK3. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:13675–13679. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.23.13675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moriguchi T, Toyoshima F, Gotoh Y, Iwamatsu A, Irie K, Mori E, Kuroyanagi N, Hagiwara M, Matsumoto K, Nishida E. Purification and identification of a major activator for p38 from osmotically shocked cells. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:26981–26988. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.43.26981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moriguchi T, Toyoshima F, Masuyama N, Hanafusa H, Gotoh Y, Nishida E. A novel SAPK/JNK kinase, MKK7, stimulated by TNFα and cellular stresses. EMBO J. 1997;16:7045–7053. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.23.7045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nagata K, Puls A, Futter C, Aspenstrom P, Schaefer E, Nakata T, Hirokawa N, Hall A. The MAP kinase kinase kinase MLK2 co-localizes with activated JNK along microtubules and associates with kinesin superfamily motor KIF3. EMBO J. 1998;17:149–158. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.1.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nishina H, Bachmann M, Oliveira-dos-Santos A J, Kozieradzki I, Fischer K D, Odermatt B, Wakeham A, Shahinian A, Takimoto H, Bernstein A, Mak T W, Woodgett J R, Ohashi P S, Penninger J M. Impaired CD28-mediated interleukin 2 production and proliferation in stress kinase SAPK/ERK1 kinase (SEK1)/mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 4 (MKK4)-deficient T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1997;186:941–953. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.6.941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nishina H, Fischer K D, Radvanyl L, Shahinian A, Hakem R, Ruble E A, Bernstein A, Mak T W, Woodgett J R, Penninger J M. Stress-signaling kinase Sek1 protects thymocytes from apoptosis mediated by CD95 and CD3. Nature. 1997;385:350–353. doi: 10.1038/385350a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Olson M F, Ashworth A, Hall A. An essential role for Rho, Rac, and Cdc42 GTPases in cell cycle progression through G1. Science. 1995;269:1270–1272. doi: 10.1126/science.7652575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Posas F, Saito H. Osmotic activation of the HOG MAPK pathway via Ste11p MAPKKK: scaffold role of Pbs2p MAPKK. Science. 1997;276:1702–1705. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5319.1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Raingeaud J, Whitmarsh A J, Barrett T, Derijard B, Davis R J. MKK3- and MKK6-regulated gene expression is mediated by the p38 mitogen-activated signal transduction pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:1247–1255. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.3.1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rana A, Gallo K, Godowski P, Hirai S, Ohno S, Zon L, Kyriakis J M, Avruch J. The mixed lineage kinase SPRK phosphorylates and activates the stress-activated protein kinase activator, SEK-1. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:19025–19028. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.32.19025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Robinson M J, Cobb M H. Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:180–186. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80061-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sakuma H, Ikeda A, Oka S, Kozutsumi Y, Zanetta J P, Kawasaki T. Molecular cloning and functional expression of a cDNA encoding a new member of mixed lineage protein kinase from human brain. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:28622–28629. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.45.28622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sanchez I, Hughes R T, Mayer B J, Yee K, Woodgett J R, Avruch J, Kyriakis J M, Zon L I. Role of SAPK/ERK kinase-1 in the stress-activated pathway regulating transcription factor c-Jun. Nature. 1994;372:794–798. doi: 10.1038/372794a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Seth A, Gonzalez F A, Gupta S, Raden D L, Davis R J. Signal transduction within the nucleus by mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:24796–24804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sluss H K, Han Z, Barrett T, Davis R J, Ip Y T. A JNK signal transduction pathway that mediates morphogenesis and an immune response in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2745–2758. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.21.2745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stein B, Brady H, Yang M X, Young D B, Barbosa M S. Cloning and characterization of MEK6, a novel member of the mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase cascade. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:11427–11433. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.19.11427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Su Y C, Han J, Xu S, Cobb M, Skolnik E Y. NIK is a new Ste20-related kinase that binds NCK and MEKK1 and activates the SAPK/JNK cascade via a conserved regulatory domain. EMBO J. 1997;16:1279–1290. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.6.1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Swat W, Fujikawa K, Ganiatsas S, Yang D, Xavier R J, Harris N L, Davidson L, Ferrini R, Davis R J, Labow M A, Flavell R A, Zon L I, Alt F W. SEK1/MKK4 is required for maintenance of a normal peripheral lymphoid compartment but not for lymphocyte development. Immunity. 1998;8:625–634. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80567-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Takekawa M, Posas F, Saito H. A human homolog of the yeast Ssk2/Ssk22 MAP kinase kinase kinases, MTK1, mediates stress-induced activation of the p38 and JNK pathways. EMBO J. 1997;16:4973–4982. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.16.4973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tapon N, Nagata K, Lamarche N, Hall A. A new rac target POSH is an SH3-containing scaffold protein involved in the JNK and NF-kappaB signalling pathways. EMBO J. 1998;17:1395–1404. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.5.1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Teng D H, Perry W L, Hogan J K, Baumgard M, Bell R, Berry S, Davis T, Frank D, Frye C, Hattier T, Hu R, Jammulapati S, Janecki T, Leavitt A, Mitchell J T, Pero R, Sexton D, Schroeder M, Su P H, Swedlund B, Kyriakis J M, Avruch J, Bartel P, Wong A K C, Oliphant A, Thomas A, Skolnick M H, Tavtigian S V. Human mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 4 as a candidate tumor suppressor. Cancer Res. 1997;57:4177–4182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Teramoto H, Coso O A, Miyata H, Igishi T, Miki T, Gutkind J S. Signaling from the small GTP-binding proteins Rac1 and Cdc42 to the c-Jun N-terminal kinase/stress-activated protein kinase pathway. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:27225–27228. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.44.27225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tibbles L A, Ing Y L, Kiefer F, Chan J, Iscove N, Woodgett J R, Lassam N J. MLK-3 activates the SAPK/JNK and p38/RK pathways via SEK1 and MKK3/6. EMBO J. 1996;15:7026–7035. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tournier C, Whitmarsh A J, Cavanagh J, Barrett T, Davis R J. MAP kinase kinase 7 is an activator of the c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:7337–7342. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Toyoshima F, Moriguchi T, Nishida E. Fas induces cytoplasmic apoptotic responses and activation of the MKK7-JNK/SAPK and MKK6-p38 pathways independent of CPP32-like proteases. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:1005–1015. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.4.1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tung R M, Blenis J. A novel human SPS1/STE20 homologue, KHS, activates Jun N-terminal kinase. Oncogene. 1997;14:653–659. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1200877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wang W, Zhou G, Hu M C T, Yao Z, Tan T H. Activation of the hematopoietic progenitor kinase-1 (HPK1)-dependent, stress-activated c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) pathway by transforming growth factor beta (TGF-beta)-activated kinase (TAK1), a kinase mediator of TGF beta signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:22771–22775. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.36.22771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wang X S, Diener K, Jannuzzi D, Trollinger D, Tan T H, Lichenstein H, Zukowski M, Yao Z. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel protein kinase with a catalytic domain homologous to mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:31607–31611. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.49.31607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.White R A, Hughes R T, Adkison L R, Bruns G, Zon L I. The gene encoding protein kinase SEK1 maps to mouse chromosome 11 and human chromosome 17. Genomics. 1996;34:430–432. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Whitmarsh A J, Cavanagh J, Tournier C, Yasuda J, Davis R J. A mammalian scaffold complex that selectively mediates MAP kinase activation. Science. 1998;281:1671–1674. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5383.1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Whitmarsh A J, Davis R J. Transcription factor AP-1 regulation by mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathways. J Mol Med. 1996;74:589–607. doi: 10.1007/s001090050063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wu Z, Wu J, Jacinto E, Karin M. Molecular cloning and characterization of human JNKK2, a novel Jun NH2-terminal kinase-specific kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:7407–7416. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.12.7407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Xu S, Cobb M H. MEKK1 binds directly to the c-Jun N-terminal kinases/stress-activated protein kinases. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:32056–32060. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.51.32056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yan M, Dai T, Deak J C, Kyriakis J M, Zon L I, Woodgett J R, Templeton D J. Activation of stress-activated protein kinase by MEKK1 phosphorylation of its activator SEK1. Nature. 1994;372:798–800. doi: 10.1038/372798a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yang D, Tournier C, Wysk M, Lu H-T, Xu J, Davis R J, Flavell R A. Targeted disruption of the MKK4 gene causes embryonic death, inhibition of c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase activation and defects in AP-1 transcriptional activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3004–3009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yang S H, Whitmarsh A J, Davis R J, Sharrocks A D. Differential targeting of MAP kinases to the ETS-domain transcription factor Elk-1. EMBO J. 1998;17:1740–1749. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.6.1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yao Z, Diener K, Wang X S, Zukowski M, Matsumoto G, Zhou G, Mo R, Sasaki T, Nishina H, Hui C C, Tan T H, Woodgett J P, Penninger J M. Activation of stress-activated protein kinases/c-Jun N-terminal protein kinases (SAPKs/JNKs) by a novel mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:32378–32383. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.51.32378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yashar B M, Kelley C, Yee K, Errede B, Zon L I. Novel members of the mitogen-activated protein kinase activator family in Xenopus laevis. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:5738–5748. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.9.5738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zhang S, Han J, Sells M-A, Chernoff J, Knaus U G, Ulevitch R J, Bokoch G M. Rho family GTPases regulate p38 Mitogen-activated protein kinase through the down-stream mediator PAK-1. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:23934–23936. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.41.23934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]