Abstract

PURPOSE

Durable partial response (PR) and durable stable disease (SD) are often seen in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) receiving atezolizumab plus bevacizumab (atezo-bev). This study investigates the outcome of these patients and the histopathology of the residual tumors.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The IMbrave150 study's atezo-bev group was analyzed. PR or SD per RECIST v1.1 lasting more than 6 months was defined as durable. For histologic analysis, a comparable real-world group of patients from Japan and Taiwan who had undergone resection of residual tumors after atezo-bev was investigated.

RESULTS

In the IMbrave150 study, 56 (77.8%) of the 72 PRs and 41 (28.5%) of the 144 SDs were considered durable. The median overall survival was not estimable for patients with durable PR and 23.7 months for those with durable SD. The median progression-free survival was 23.2 months for patients with durable PR and 13.2 months for those with durable SD. In the real-world setting, a total of 38 tumors were resected from 32 patients (23 PRs and nine SDs) receiving atezo-bev. Pathologic complete responses (PCRs) were more frequent in PR tumors than SD tumors (57.7% v 16.7%, P = .034). PCR rate correlated with time from atezo-bev initiation to resection and was 55.6% (5 of 9) for PR tumors resected beyond 8 months after starting atezo-bev, a time practically corresponding to the durable PR definition used for IMbrave150. We found no reliable radiologic features to predict PCR of the residual tumors.

CONCLUSION

Durable PR patients from the atezo-bev group showed a favorable outcome, which may be partly explained by the high rate of PCR lesions. Early recognition of PCR lesions may help subsequent treatment decision.

INTRODUCTION

The combination of atezolizumab (atezo; anti–PD-L1 antibody) and bevacizumab (bev; antivascular endothelial growth factor antibody) has become the first-line standard treatment for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) since 2020.1,2 In addition to a complete response (CR) rate of 8% for atezo-bev, the regimen often results in a high disease control rate and a sustainable response duration. Hence, in the real-world setting, more and more patients are in a state of long-lasting partial response (PR) or stable disease (SD). However, the outcome, clinical course, and histologic features of the radiologically persistent tumors of these patients are not fully understood.

CONTEXT

Key Objective

The reasons why patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) often experience a durable response to immunotherapy remain unclear.

Knowledge Generated

Our study reveals that a significant proportion of HCC tumors become ghost tumors (tumors that are radiologically persistent without viable tumor cells on routine pathologic examinations) after immunotherapy.

Relevance (E.M. O'Reilly)

Atezolizumab and bevacizumab is relatively recent new standard therapy for advanced HCC. These data provide insights on histologic and radiologic characteristics for patients who achieve excellent cancer control, and support the observation known from other diseases that a favorable anti-tumor response may be underpinned by a pathologic complete response.*

*Relevance section written by JCO Associate Editor Eileen M. O'Reilly, MD.

To answer these questions, we have performed a comprehensive post hoc analysis of the IMbrave150 study. Since the IMbrave150 study did not collect information of subsequently resected tumors, we performed a real-world analysis of comparable patients who had undergone tumor resection after atezo-bev treatment in multiple centers of Japan and Taiwan, where salvage or curative resection is often performed for those stable residual tumors.3,4

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

Data from patients receiving atezo-bev in the intent-to-treat population of the IMbrave150 study (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT03434379)1,2 were analyzed. Treatment responses were assessed according to RECIST v1.1 every 6 weeks for the first 54 weeks and every 9 weeks thereafter, by the independent review facility (IRF). PR or SD lasting over 6 months was classified as durable PR or durable SD, respectively. By contrast, PR or SD persisting for 6 months or less was considered nondurable. CR, typically the best response category, only serves as the reference group in survival analysis.

Because of the lack of on-treatment tumor tissue from the IMbrave150 study, consecutive adult patients who had undergone tumor resection at a state of PR or SD after atezo-bev treatment from January 2021 to March 2023 were retrospectively enrolled from eight hospitals of Japan and eight hospitals of Taiwan (Taiwan Liver Cancer Association Research Group) for histologic analysis. Tumor assessments were conducted in accordance with local practice, at baseline and every 9-12 weeks. Since the radiologic follow-up program was different from the stringent protocol of IMbrave150, we estimated that remaining PR or SD at least 8 months from starting atezo-bev to resection largely corresponded to durable PR or durable SD, as defined for IMbrave150 in this study. The decision to do surgical intervention in this real-world patient cohort was made by individual treating physicians for a curative intent after a planned neoadjuvant approach, successful downstaging, and stationary tumor sizes in consecutive radiologic assessments. Clinical information, including patient characteristics, etiology and extent of HCC, previous treatment, liver function, performance status, starting and end dates of atezo-bev, date and method of tumor resection, and histologic findings, was collected from electronic medical records. Response per RECIST v1.1 at the time of tumor resection was assessed by individual treating physicians. Response per modified RECIST (mRECIST) was not shown because of being nonevaluable in many patients. Institute Review Board approvals were obtained from each participating hospital, and informed consent documentation was waived.

Survival Outcomes (IMbrave150 cohort)

Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from random assignment to death from any cause. Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as time from random assignment to disease progression per IRF-assessed RECIST v1.1 or death from any cause, whichever occurred first.

Isolated Progression (IMbrave150 study)

At the time of progressive disease (PD) per IRF-assessed RECIST v1.1, every lesion was individually assessed. Isolated progression was defined as only one lesion (target, nontarget, or new) progressed, whereas all other lesions remained regressed or stationary.

Pathologic Complete Response (real-world cohort)

Pathologic complete response (PCR), indicating the absence of viable tumor cells, was assessed for individual resected tumors, according to the standard procedures of the respective participating hospitals. Typically, each tumor sample was thoroughly inspected for its gross appearance and then meticulously examined with sections cut at a thickness of 0.5 cm. A number of tissue blocks corresponding to the length of the tumor's longest diameter in centimeters were taken. Any gross suspicious areas were further examined. This sampling method was subject to adjustments on the basis of the characteristics of individual tumors, staging requirements, and clarification of tumor margin to comply with the standards set forth by the College of American Pathology.5

Statistical Analysis

For the post hoc analysis of the IMbrave150 study, clinical characteristics at baseline were compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test (for age only) and Fisher's exact test (for all other variables). Durability of PR and SD, the subsequent progression rate, and the proportion of isolated progressions among all progressions between durable PR and durable SD were compared using Fisher's exact test. Median OS and PFS were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Mean OS and PFS were estimated using restricted mean survival time analysis.6,7 However, this study had no intent to compare survival between groups because of the lack of power. In the real-world study, the PCR rates between groups were compared using Fisher's exact test.

RESULTS

Clinical Outcomes and Dispositions of Durable PR or SD Patients (IMbrave150 study)

As of the most recent clinical update (August 31, 2020), 28 (8.9%), 72 (22.1%), and 144 (44.2%) patients in the atezo-bev group achieved CR, PR, and SD, respectively. Fifty-six (77.8%) of the 72 PRs and 41 (28.5%) of the 144 SDs were durable as defined in the methods. PR was more likely to be durable than SD (77.8% v 28.5%, P < .001). A total of 97 patients (56 durable PRs and 41 durable SDs) were analyzed in this study. The baseline characteristics of patients with durable PR or durable SD were generally similar to those with nondurable PR or SD, except that patients with nondurable SD were younger than those with durable SD (median age: 63 v 68 years; P = .003; Appendix Table A1, online only).

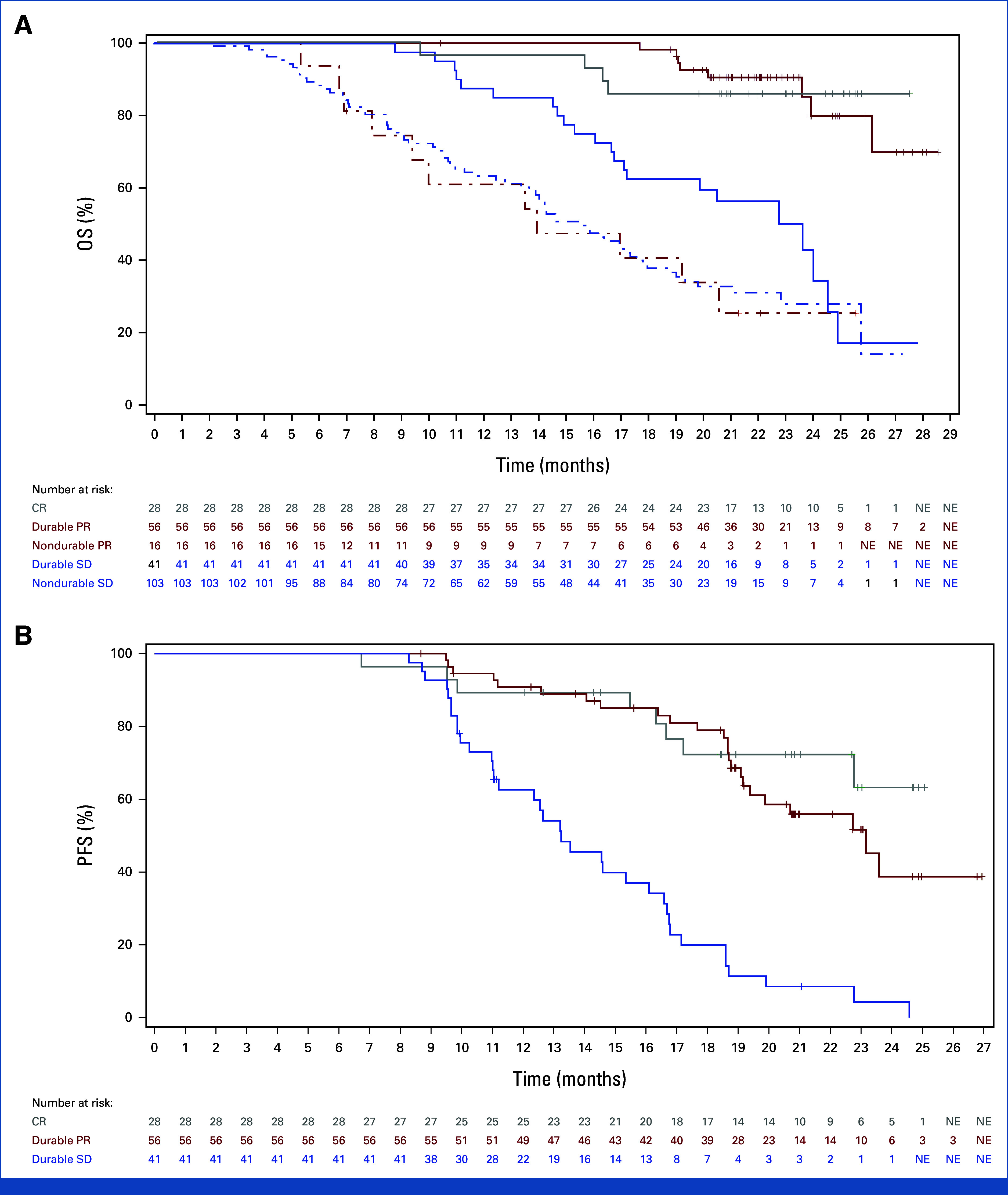

Post hoc analyses were not intended for any statistical comparison. However, to better depict the survival outcomes of patients with durable PR or durable SD, data of CR and nondurable PR or SD are also shown for reference. Figure 1A illustrates that the median OS was not estimable (NE; 95% CI, NE to NE) for patients with CR, NE (95% CI, 26.2 to NE) for patients with durable PR, and 23.7 months (95% CI, 17.2 to 24.6) for those with durable SD. The mean OS (adjusted by SEM) was 25.4 ± 0.9 months for patients with CR, 26.0 ± 0.4 months for those with durable PR, and 20.6 ± 0.9 months for those with durable SD. The estimated OS rates at 12, 18, and 24 months were 96.4%, 85.7%, and 85.7% for CR; 100%, 98.2%, and 79.9% for durable PR; and 87.6%, 62.5%, and 43.0% for durable SD, respectively. By contrast, patients with nondurable PR and those with nondurable SD showed markedly worse OS (median OS: 13.9 [95% CI, 9.4, to 20.6] months for patients with nondurable PR; 15.6 [95% CI, 13.7 to 17.6] months for patients with nondurable SD).

FIG 1.

Survival outcomes of patients exhibiting durable PR and durable SD in the atezo-bev group of the IMbrave150 study. (A) OS. The Kaplan-Meier OS curves of patients with CR, durable PR, nondurable PR, durable SD, and nondurable SD are shown. (B) PFS. The Kaplan-Meier PFS curves of patients with CR, durable PR, and durable SD are shown. atezo-bev, atezolizumab plus bevacizumab; CR, complete response; NE, nonestimable; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease.

Figure 1B shows that the median PFS was NE (95% CI, 22.8 to NE) for patients with CR, 23.2 months (95% CI, 19.4 to NE) for those with durable PR, and 13.2 months (95% CI, 11.3 to 16.1) for those with durable SD. The mean PFS (adjusted by SEM) was 21.3 ± 1.0 months for patients with CR, 20.7 ± 0.7 months for those with durable PR, and 14.2 ± 0.7 months for those with durable SD. The estimated PFS rates at 12, 18, and 24 months were 89.3%, 72.3%, and 63.2% for CR; 90.8%, 79.0%, and 38.7% for durable PR; and 62.6%, 19.9%, and 4.3% for durable SD, respectively. It is noteworthy that the PFS curves of CR and durable PR were similar until 19 months after treatment initiation.

Progression patterns and subsequent therapies in patients with durable PR or SD are detailed in Table 1. Patients with durable PR had a lower tendency to develop PD compared with those with durable SD (35.7% v 56.1%; P = .063). The rates of isolated progression were similar between the two groups (35.0% for durable PR v 30.4% for durable SD; P > .999). Notably, 75% of PD patients with initially durable PR and 86.9% of those with initially durable SD continued atezolizumab with or without bevacizumab after first progression.

TABLE 1.

Progression Patterns and Subsequent Therapies

| Progression Pattern and Subsequent Treatment | Durable PR (n = 56) | Durable SD (n = 41) |

|---|---|---|

| Median duration of follow-up, months (95% of CI) | 22.3 (21.7 to 23.5) | 21.6 (21.1 to 23.9) |

| All progressions, No. (%a) | 20 (100) | 23 (100) |

| Isolated progression, No. (%a) | 7 (35.0) | 7 (30.4) |

| No treatment on or after first PD | 1 (5.0) | 2 (8.7) |

| Continue atezo (with or without bev) on or after first PD | 5 (25.0) | 5 (21.7) |

| Other anticancer treatment on or after first PD | 1 (5.0) | 0 |

| Nonisolated progression, No. (%a) | 13 (65.0) | 16 (69.6) |

| No treatment on or after first PD | 1 (5.0) | 1 (4.3) |

| Continue atezo (with or without bev) on or after first PD | 10 (50.0) | 15 (65.2) |

| Other anticancer treatment on or after first PD | 2 (10.0) | 0 |

Abbreviations: atezo, atezolizumab; bev, bevacizumab; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease.

The total number of patients who experienced subsequent progression, referred to as all progressions, was used as the denominator.

Pathologic Responses of Residual Tumors in PR or SD Patients (real-world cohort)

A total of 32 patients with HCC who underwent tumor resection after first-line atezo-bev treatment were analyzed (Table 2). Among these patients, 18 (56.2%) presented with Barcelona Clinical Liver Cancer stage C disease, five (15.6%) had extrahepatic spread, 14 (43.7%) exhibited macrovascular invasion, and five (15.6%) showed extensive intrahepatic involvement (≥50% of liver) before starting atezo-bev. Of the five patients initially presenting with extrahepatic spread, three underwent only hepatectomy because of complete resolution of their lung metastases. Another patient underwent only pulmonary metastasectomy because of the absence of recurrent hepatic tumors while initiating atezo-bev. The last patient underwent both hepatectomy and right adrenal metastasectomy with both lesions becoming resectable after atezo-bev treatment. As of now, none of them have experienced recurrence after surgery. In the whole group, the majority (71.9%, n = 23) achieved PR, whereas nine (28.1%) achieved SD before undergoing tumor resection. The median time from atezo-bev initiation to tumor resection was 6.6 months (range: 1.2-22.6 months) with a trend toward a shorter duration in patients with SD compared with those with PR (median: 4.0 months v 7.4 months; P = .1387).

TABLE 2.

Baseline Characteristics of Real-World Patients Undergoing Tumor Resection After Atezolizumab-Bevacizumab Treatment

| Variable | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Total | 32 (100) |

| Age, years | |

| Median (range) | 67.7 (41.5-82.2) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 27 (84.4) |

| Female | 5 (15.6) |

| Country | |

| Japan | 22 (68.8) |

| Taiwan | 10 (31.2) |

| Etiology | |

| HBsAg+, anti-HCV– | 10 (31.3) |

| HBsAg–, anti-HCV+ | 8 (25.0) |

| HBsAg–, anti-HCV– | 14 (43.7) |

| ECOG performance status | |

| 0 | 20 (62.5) |

| 1 | 12 (37.5) |

| Child-Pugh classification | |

| A | 31 (96.9) |

| B | 1 (3.1) |

| BCLC stage | |

| B | 14 (43.8) |

| C | 18 (56.2) |

| AFP | |

| <400 ng/mL | 15 (46.9) |

| ≥400 ng/mL | 17 (53.1) |

| EHS | |

| No | 27 (84.4) |

| Yes | 5 (15.6) |

| MVI | |

| No | 18 (56.3) |

| Yes | 14 (43.7) |

| Liver occupancy ≥50% | |

| No | 27 (84.4) |

| Yes | 5 (15.6) |

| Previous liver-directed locoregional therapy | |

| No | 23 (71.9) |

| Yes | 9 (28.1) |

Abbreviations: AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; atezo-bev, atezolizumab-bevacizumab; BCLC, Barcelona Clinical Liver Cancer; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; EHS, extrahepatic spread; HBsAg, hepatitis B virus surface antigen; HCV, hepatitis C virus; MVI, macrovascular invasion; PS, performance status.

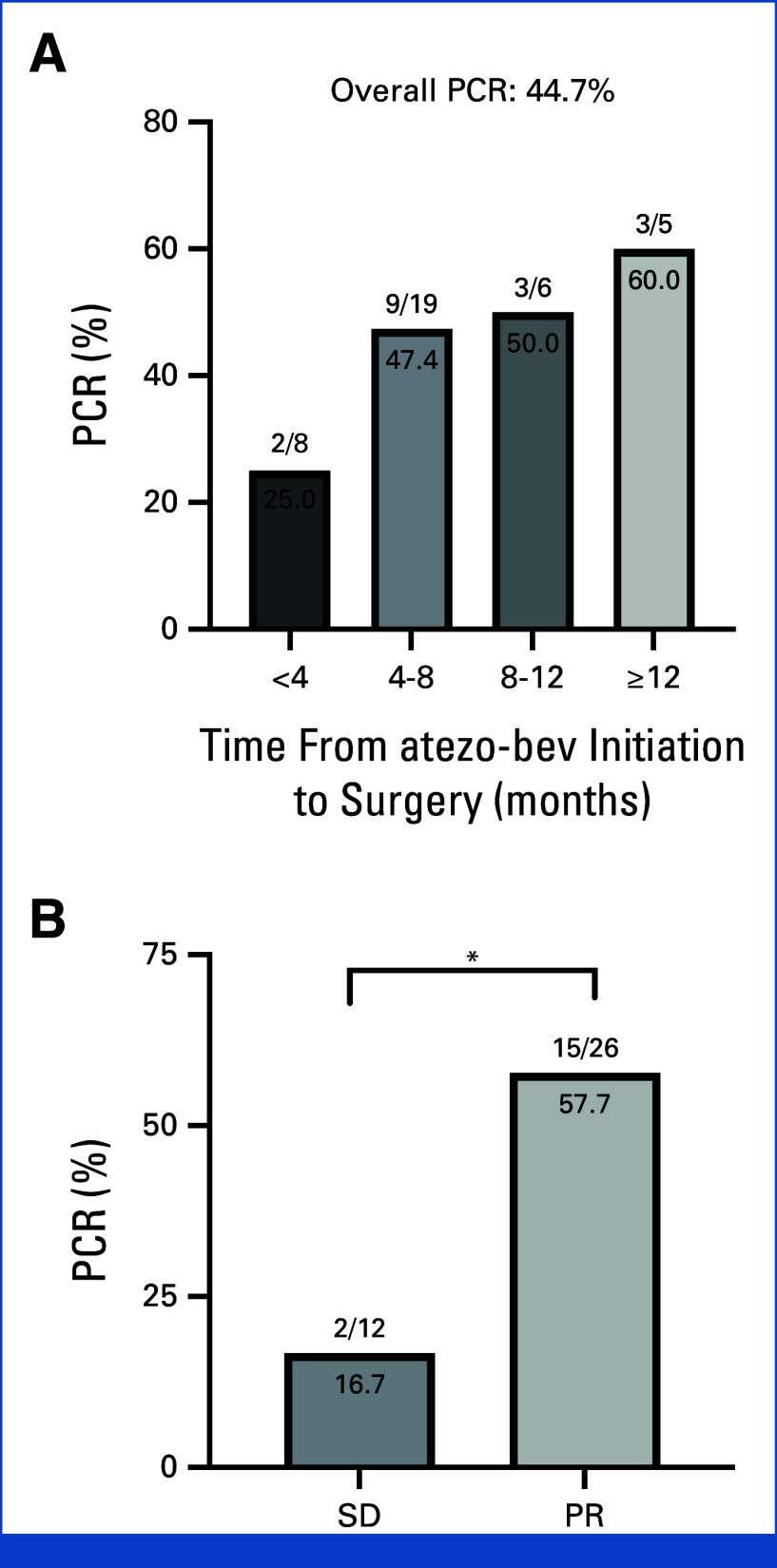

Most patients underwent curative resection of single tumor, but five patients received resection of multiple tumors (two tumors in four patients and three tumors in one patient). A total of 38 tumors were resected (35 in the liver, two in the lung, and one in the adrenal gland), including 26 from patients with PR (PR tumors) and 12 from those with SD (SD tumors). PCR was observed as soon as 2.2 months after initiation of atezo-bev. The PCR rates were 25% (2 of 8), 47.4% (9 of 19), 50% (3 of 6), and 60% (3 of 5) for tumors resected within 4, 4-8, 8-12, and beyond 12 months after initiation of atezo-bev treatment, respectively (Fig 2A). Notably, PCRs were observed in five (55.6%) of nine PR tumors and one (50%) of two SD tumors, which persisted for more than 8 months after initiating atezo-bev without progression. PCRs occurred in 15 (57.7%) of 26 PR tumors compared with only two (16.7%) of 12 SD tumors (P = .034; Fig 2B).

FIG 2.

PCR rates. (A) PCR rates per tumor according to time from atezo-bev initiation to surgery. (B) PCR rates per tumor according to the tumor response at the time of surgery. *P < .05. atezo-bev, atezolizumab plus bevacizumab; PCR, pathologic complete response; PR, partial response per RECIST v1.1; SD, stable disease per RECIST v1.1.

Correlation of Radiologic and Pathologic Responses (real-world cases)

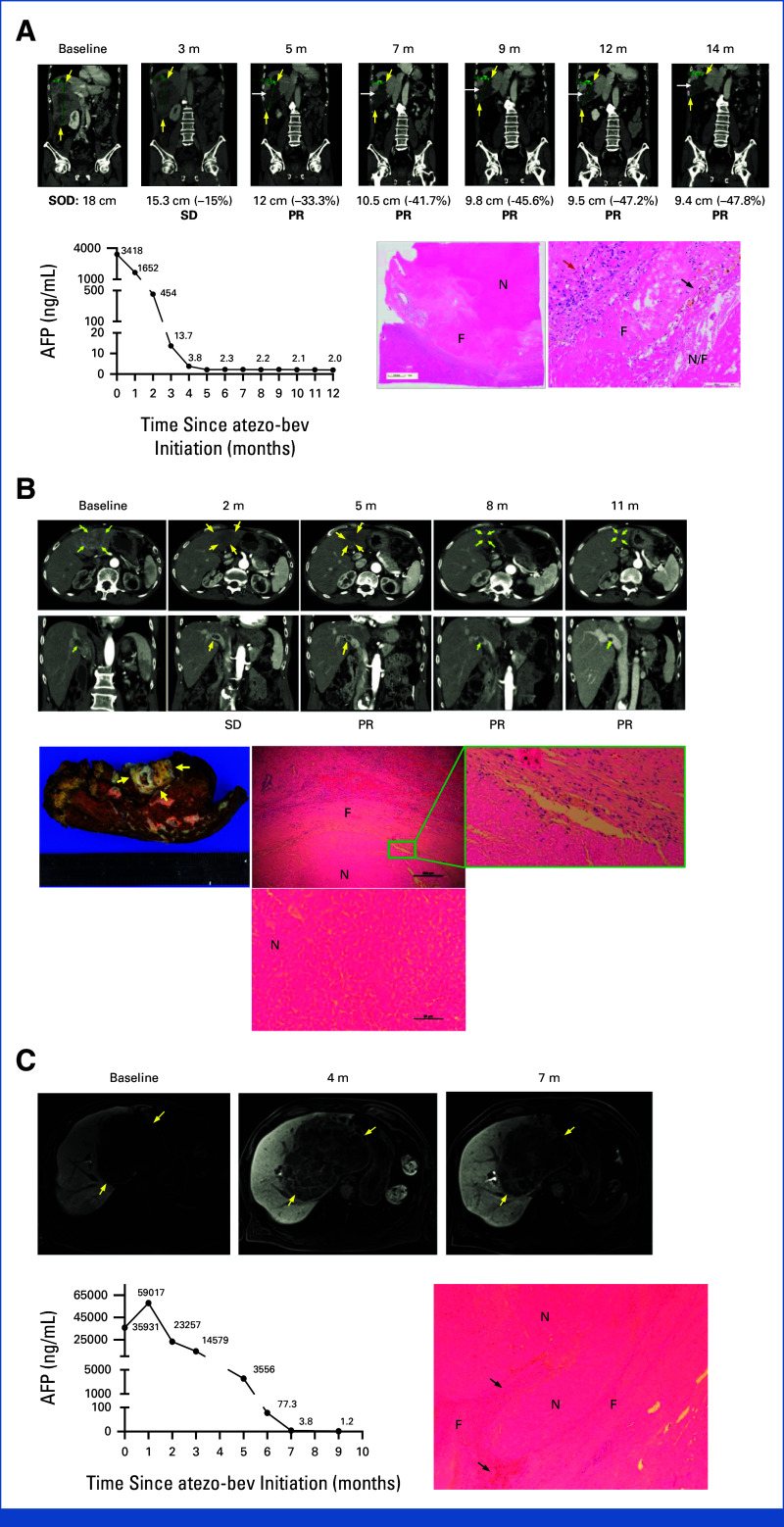

Figure 3 presents a remarkable discrepancy between radiologic and pathologic findings of two patients with durable PR and one patient with durable SD on atezo-bev, all achieving PCR of residual tumors. The first case (Fig 3A) involves a 63-year-old man with chronic hepatitis B, initially presenting with a large hypervascular hepatic tumor, right portal vein thrombus, and an elevated alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level of 3,418 ng/mL. He met RECIST v1.1–defined PR at 5 months after atezo-bev initiation. However, intratumor heterogeneous hyperenhancement (indicated by white arrows in Fig 3A) with a hypoenhanced background was noted, leading to difficulties in assessing tumor response per mRECIST. Pathologic examination revealed extensive necrosis and hyaline fibrosis without viable tumor cells. Instead, scattered aggregates of plasma cells, histiocytes, and macrophages were seen in the tumor bed (indicated by a red arrow in Fig 3A). The second case (Fig 3B) vignettes a 67-year-old man with a history of resolved chronic hepatitis C and a previous resected stage I HCC, presenting with recurrent infiltrative HCC, main portal vein thrombosis, and a low AFP level. He met RECIST v1.1–defined PR at 5 months after atezo-bev initiation. The tumor size remained stationary despite 1 year of atezo-bev treatment. The tumor assessment per mRECIST was challenging because of infiltrative nature and equivocal global enhancement of the post-treatment tumor. The pathologic examination showed scar tissue with central coagulative necrosis and the absence of viable tumor cells in the residual tumor bed and vascular thrombus. The third case (Fig 3C) illustrates a 79-year-old man with a history of chronic hepatitis B, presenting a large HCC with portal vein invasion and a high AFP level at baseline. Curative surgery was not feasible because of impaired hepatic reserve (Child-Pugh B9). The best tumor response was SD per RECIST v1.1 with AFP normalization. Because of improved liver function, he then received curative surgery later, and the pathologic examination showed extensive necrosis without viable tumor cells.

FIG 3.

Pathologic complete responses achieved in patients with durable PR or durable SD after atezo-bev treatment. (A) A patient achieved durable PR before resection. Tumors are outlined by yellow arrows. Intratumor heterogenous hyperenhancement is indicated by white arrows. AFP normalization was observed approximately 1 month before PR was documented. Microscopically, the tumor shows extensive necrosis (denoted as N), surrounded by hyaline fibrosis (denoted as F). The red arrow denotes infiltration of plasma cells, lymphocytes, and histiocytes in a high-power field. The black arrow denotes scattered hemosiderin-laden macrophages, foamy cells, and cholesterol clefts. (B) A patient achieved durable PR before tumor resection. The tumor and main portal vein thrombus are outlined or indicated by yellow arrows. The gross image of the resected tumor shows a scar with central coagulative necrosis, surrounded by fibrotic tissue. Microscopically, the tumor shows coagulative necrosis (denoted as N), surrounded by histiocytes/macrophages (shown in green box), and a thick fibrous capsule (denoted as F). No viable tumor cells were found after comprehensive microscopic examination of the entire tumor. (C) A patient achieved durable SD before tumor resection. MRI images showed a large hepatic tumor, outlined by yellow arrows. Microscopically, the tumor exhibited coagulative necrosis with hemosiderin deposits and no viable tumor cells, surrounded by an inflamed fibrous capsule. AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; atezo-bev, atezolizumab plus bevacizumab; cm, centimeter; MRI, magnetic resonance images; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; SOD, sum of longest diameters of target lesions.

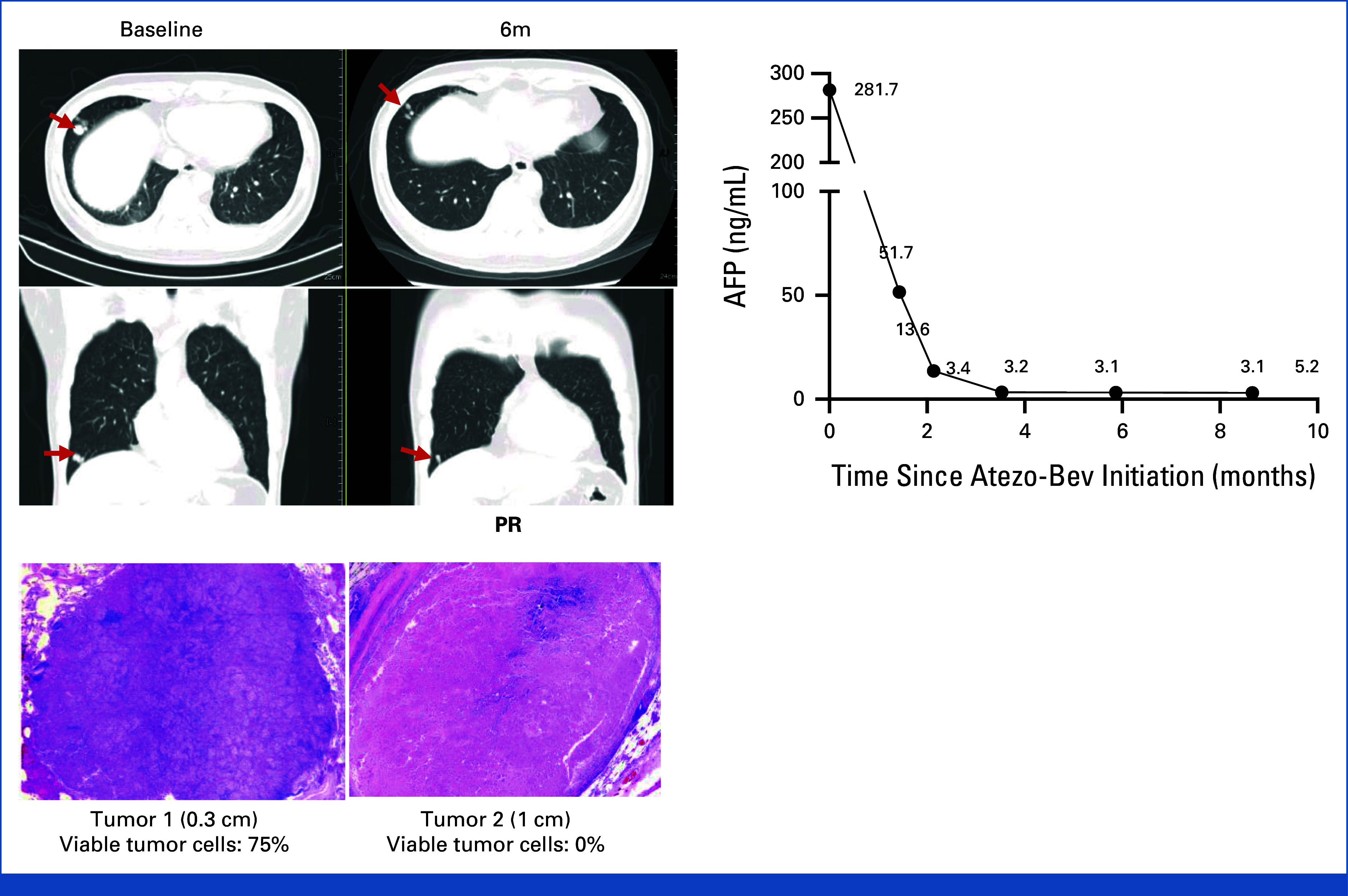

Among five patients who had multiple tumors resected, two (40%) patients showed discrepant pathologic responses among resected tumors. One representative case, a 44-year-old man with a history of chronic hepatitis B and previously resected HCC, presented with multiple lung metastases (Fig 4). He achieved PR per RECIST v1.1 after 6 months of atezo-bev treatment. Subsequent metastasectomy revealed two residual lung tumors with 75% and 0% of viable tumor cells, respectively, despite AFP normalization, underscoring the limitation of tumor marker normalization in predicting PCR.

FIG 4.

Discrepant pathologic responses within a single patient. A patient with multiple pulmonary nodules and a high AFP level before atezo-bev and who achieved PR before metastasectomy. Two pulmonary tumors were resected, and only one tumor achieved PCR despite AFP normalization. AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; atezo-bev, atezolizumab plus bevacizumab; PCR, pathologic complete response; PR, partial response.

DISCUSSION

Durable PR and durable SD represent an intriguing phenomenon of cancer immunotherapy. While their significance has been briefly described in other cancer types,8-11 their exact outcomes, clinical courses, and histologic correlation in patients with HCC remain unclear. This study explores these questions by post hoc analyses of patients from the atezo-bev group of the IMbrave150 study and an international multicenter real-world study to investigate the histologic findings of the resected tumors exhibiting PR or SD for various time periods after atezo-bev treatment. Our findings indicate a favorable outcome of patients with durable PR in the IMbrave150 study, and in the real-world setting, around half of the durable PR tumors appeared to be ghost tumors (radiologically persistent tumors without viable cancer cells). Although rarer, patients with durable SD may still be associated with ghost tumors. Correlations between radiologic and histologic findings were conducted in some vignetted cases—no reliable clues to predict a ghost tumor by current imaging studies were found.

Immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) immunotherapy, as opposed to targeted therapy or chemotherapy, is distinguished by remarkable durability of response,10 which leads to a substantial survival benefit. However, the exact reasons behind this phenomenon remain unknown. In the context of immunotherapy, the histologic intricacies underlying durable response are poorly explored because of a scarcity of comprehensive histopathologic studies of resected residual tumors.12-17 Our real-world analysis suggests that the prevalence of ghost tumors may help explain the longer OS in patients with durable PR and in certain patients with durable SD in the atezo-bev group of the IMbrave150 study. We often found variable infiltration of histiocytes and macrophages but negligible infiltration of cytotoxic lymphocytes and a notable presence of fibrous tissue and hyalinization necrosis in the ghost tumors. Whether the remaining innate immune cells are still suppressing the tumor growth should be elucidated.18,19 On the other hand, as viable tumor cells were still present in approximately half of postimmunotherapy durable PR tumors, it remains unclear why these viable tumor cells are constrained from a rapid reoutgrowth, unlike the scenario after chemotherapy and targeted therapy. A direct comparison of post-treatment histologic changes was made in melanoma.20 It showed a dramatic difference between the immune checkpoint inhibitor and the tyrosine kinase inhibitor.20 It raises the possibility that after an initial tumoricidal phase, a prolonged immune-mediated tumor dormancy21,22 or immune equilibrium23 may exist specifically in the postimmunotherapy lesions.

Identifying postimmunotherapy ghost tumors by noninvasive methods would greatly help the clinical decision for subsequent treatments, such as performing curative surgery or not performing curative surgery, in patients achieving durable PR or durable SD. Unfortunately, our results suggest a significant discrepancy between radiologic and pathologic responses to immunotherapy, a finding aligning with other reports,3,4,15,17 and indicate insufficiency of current imaging methods to detect PCR cases. CR per mRECIST criteria, defined as complete disappearance of arterial enhancement of intrahepatic tumors without any extrahepatic tumors, has long been equated with necrosis and is used for defining clinical CR.4,24 However, less than half of tumors exhibiting mRECIST-defined CR under immunotherapy actually achieved PCR.16,17 Novel imaging technologies, such as 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (PET) scan4,25 and artificial intelligence–assisted radiomics analyses on the basis of images of computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, or PET scans,25-31 hold promise in predicting ghost tumors. In addition to imaging biomarkers, peripheral blood-based biomarkers may help predict PCR. Tumor marker normalization has been recently proposed as one of the criteria for clinical CR.4,24 However, not all patients with HCC present with elevated tumor markers, and tumor marker normalization is not a definitive indication of PCR, as illustrated in the representative cases (Figs 3B and 4). Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) has emerged as a promising biomarker for real-time monitoring of therapeutic responses, especially in cancer types carrying dominant driver mutations.32,33 Molecular CR, defined as a complete clearance of ctDNA, often correlates with survival benefits in patients with cancer receiving ICI-based immunotherapy34,35 but does not consistently align with PCR.36-39

This study has several limitations. Regarding post hoc analyses of data from the IMbrave150 study, our definition of durable PR or durable SD is not universally standardized. While we defined it as PR or SD lasting for at least 6 months using data from the IMbrave150 study, Pons-Tostivint et al40 defined durable response as PFS exceeding three times the median PFS of the whole population of patients treated with the same treatment in the same trial. The estimated OS or PFS of subgroups defined according to the durability of PR or SD is also subjected to immortal time bias.41 The IMbrave150's median observation period is roughly 2 years, limiting our insights into long-term survival benefits of patients with durable PR or durable SD. Regarding our real-world study, the retrospective nature, limited sample size, subjective patient selection criteria for surgery, lack of uniform tissue processing procedures, and lack of central pathologic review are prone to some inherent biases. Furthermore, resection of potentially more curable lesions in patients who experienced durable PR may overestimate the PCR rate.

In conclusion, this study indicates that patients with durable PR on atezo-bev in the IMbrave150 study exhibited favorable PFS and OS. The favorable survival outcomes of durable PR may be linked to a PCR state, which likely existed in many of these patients. Our findings emphasize that the actual immunotherapy responses are often underestimated or misestimated by current imaging modalities, urging further investigations to bridge the gap between radiologic and pathologic postimmunotherapy responses.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to thank the patients who participated in IMbrave150 trial and the real-world study, the patients' families, the investigators and staff at all relevant sites, nonfinancial supports from the Taiwan Liver Cancer Association Research Group, collaborative research grant from National Taiwan University Hospital and Taipei Veterans General Hospital (VN111-02), supports from the T-Star Center (NSTC 113-2634-F-039-001), and fees for Open Access supported by F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Ltd.

APPENDIX

TABLE A1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients With Durable PR, Nondurable PR, Durable SD, and Nondurable SD in the Atezolizumab-Bevacizumab Group of the IMbrave150 Study

| Variable | Durable PR (n = 56) | Nondurable PR (n = 16) | P | Durable SD (n = 41) | Nondurable SD (n = 103) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ns | .0026 | ||||

| Median (range) | 64.0 (34-87) | 66.5 (49-85) | 68.0 (43-85) | 63 (27-88) | ||

| Sex, No. (%) | ns | ns | ||||

| Male | 47 (83.9) | 13 (81.3) | 35 (85.4) | 81 (78.6) | ||

| Female | 9 (16.1) | 3 (18.8) | 6 (14.6) | 22 (21.4) | ||

| Ethnicity, No. (%) | ns | ns | ||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 2 (3.6) | 0 | 1 (2.4) | 2 (1.9) | ||

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 52 (92.9) | 16 (100) | 37 (90.2) | 90 (87.4) | ||

| Not stated or unknown | 2 (3.6) | 0 | 3 (7.3) | 11 (10.7) | ||

| Geographical region, No. (%) | ns | ns | ||||

| Asia (excluding Japan) | 25 (44.6) | 8 (50) | 14 (34.1) | 31 (30.1) | ||

| Rest of world | 31 (55.4) | 8 (50) | 27 (65.9) | 72 (69.9) | ||

| ECOG PS, No. (%) | ns | ns | ||||

| 0 | 37 (66.1) | 12 (75) | 29 (70.1) | 63 (61.2) | ||

| 1 | 19 (33.9) | 4 (25) | 12 (29.3) | 40 (38.8) | ||

| Child-Pugh score, No. (%) | ns | ns | ||||

| 5 | 42 (76.4) | 12 (75) | 34 (82.9) | 73 (70.9) | ||

| 6 | 13 (23.6) | 4 (25) | 7 (17.1) | 30 (29.1) | ||

| BCLC stage, No. (%) | ns | ns | ||||

| A | 1 (1.8) | 0 | 1 (2.4) | 3 (2.9) | ||

| B | 14 (25.0) | 2 (12.5) | 6 (14.6) | 15 (14.6) | ||

| C | 41 (73.2) | 14 (87.5) | 34 (82.9) | 85 (82.5) | ||

| AFP, No. (%) | ns | ns | ||||

| <400 ng/mL | 38 (67.9) | 10 (62.5) | 28 (68.3) | 66 (64.1) | ||

| ≥400 ng/mL | 18 (32.1) | 6 (37.5) | 13 (31.7) | 37 (35.9) | ||

| EHS, No. (%) | ns | ns | ||||

| No | 24 (42.9) | 3 (18.8) | 19 (46.3) | 42 (40.8) | ||

| Yes | 32 (57.1) | 13 (81.3) | 22 (53.7) | 61 (59.2) | ||

| MVI, No. (%) | ns | ns | ||||

| No | 35 (62.5) | 10 (62.5) | 28 (68.3) | 64 (62.1) | ||

| Yes | 21 (37.5) | 6 (37.5) | 13 (31.7) | 39 (37.9) | ||

| EHS and/or MVI, No. (%) | ns | ns | ||||

| No | 16 (28.6) | 1 (6.3) | 12 (29.3) | 26 (25.2) | ||

| Yes | 40 (71.4) | 15 (93.8) | 29 (70.7) | 77 (74.8) | ||

| High-risk features,a No. (%) | ns | ns | ||||

| No | 48 (85.7) | 13 (81.3) | 38 (92.7) | 84 (81.6) | ||

| Yes | 8 (14.3) | 3 (18.8) | 3 (7.3) | 19 (18.4) | ||

| Bile duct invasion, No. (%) | ns | ns | ||||

| No | 55 (98.2) | 16 (100) | 41 (100) | 102 (99.0) | ||

| Yes | 1 (1.8) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.0) | ||

| Main portal vein (VP4) thrombus, No. (%) | ns | ns | ||||

| No | 49 (87.5) | 14 (87.5) | 39 (95.1) | 89 (86.4) | ||

| Yes | 7 (12.5) | 2 (12.5) | 2 (4.9) | 14 (13.6) | ||

| Liver occupancy ≥50%, No. (%) | ns | ns | ||||

| No | 55 (98.2) | 18 (93.8) | 40 (97.6) | 97 (94.2) | ||

| Yes | 1 (1.8) | 1 (6.3) | 1 (4.9) | 6 (5.8) | ||

| Etiology of HCC, No. (%) | ns | ns | ||||

| HBV | 30 (53.6) | 5 (31.3) | 14 (34.1) | 44 (42.7) | ||

| HCV | 10 (17.9) | 5 (31.3) | 11 (26.8) | 24 (23.3) | ||

| Nonviral | 16 (28.6) | 6 (37.5) | 16 (39.0) | 35 (34.0) | ||

| PD-L1 status,b No. (%) | n = 22 | n = 7 | n = 16 | n = 39 | ||

| TC and IC <1% | 8 (36.4) | 2 (28.6) | ns | 7 (43.8) | 16 (41.0) | ns |

| TC or IC ≥1% | 14 (63.6) | 5 (71.4) | 9 (56.2) | 23 (59.0) | ||

| TC and IC <5% | 15 (68.2) | 2 (28.6) | ns | 10 (62.5) | 27 (69.2) | ns |

| TC or IC ≥5% | 7 (31.8) | 5 (71.4) | 6 (37.5) | 12 (30.8) | ||

| TC and IC <10% | 18 (81.8) | 5 (71.4) | ns | 14 (87.5) | 38 (97.4) | ns |

| TC or IC ≥10% | 4 (18.2) | 2 (28.6) | 2 (12.5) | 1 (2.6) |

Abbreviations: AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; BCLC, Barcelona Clinical Liver Cancer; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; EHS, extrahepatic spread; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HCV, hepatitis C virus; IC, immune cell; MVI, macrovascular invasion; ns, not statistically significant; PR, partial response; PS, performance status; SD, stable disease; TC, tumor cell.

Any of the following features: bile duct invasion, VP4 thrombus, or liver occupancy ≥50%.

Assessed using an immunohistochemical method; the details have been reported before (Zhu et al42).

Ying-Chun Shen

Speakers' Bureau: Roche, Eisai/MSD, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Ipsen, Astellas Pharma

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Roche/Genentech, Eisai

Tsung-Hao Liu

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Roche

Alan Nicholas

Employment: Genentech

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Genentech

Akihiko Soyama

Research Funding: SCREEN Holdings. Co (Inst)

Tomoharu Yoshizumi

Speakers' Bureau: AstraZeneca, Eisai, Chugai Pharma

Shinji Itoh

Honoraria: Chugai Pharma, AstraZeneca, Eisai, Takeda, Incyte Japan, Ono Pharmaceutical

Etsuro Hatano

Honoraria: Eisai, Bayer, Otsuka, Merck, Lilly, Chugai Pharma, Taiho Pharmaceutical, Ono Pharmaceutical, Incyte, AbbVie, AstraZeneca

Consulting or Advisory Role: Shionogi, Novartis, AstraZeneca

Research Funding: Eisai, Tsumura & Co

Atsushi Naganuma

Speakers' Bureau: Chugai/Roche, AstraZeneca, Eisai/MSD

Li-Chun Lu

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Pfizer

Honoraria: Roche, AstraZeneca

Chih-Hung Hsu

Honoraria: Bristol Myers Squibb, Ono Pharmaceutical, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Roche, Eisai

Consulting or Advisory Role: Ono Pharmaceutical, Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck Serono, Roche/Genentech, AstraZeneca, Daiichi Sankyo

Research Funding: Ono Pharmaceutical (Inst), AstraZeneca (Inst), MSD (Inst), Merck Serono (Inst), Taiho Pharmaceutical (Inst), Bristol Myers Squibb (Inst), BeiGene (Inst), NuCana (Inst), Johnson & Johnson (Inst), Roche/Genentech (Inst), NGM Biopharmaceuticals (Inst), Eucure Biopharma (Inst), Surface Oncology (Inst), Ipsen (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Daiichi Sankyo, Roche

Yi-Hsiang Huang

Honoraria: AstraZeneca, Gilead Sciences

Sairy Hernandez

Employment: Genentech

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Genentech

Research Funding: Genentech

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: HPK1 target as immunotherapy

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Genentech

Richard S. Finn

Consulting or Advisory Role: Pfizer, Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck, Eisai, Lilly, Genentech/Roche, AstraZeneca, Exelixis, CStone Pharmaceuticals, Hengrui Therapeutics, Medivir

Speakers' Bureau: Genentech

Research Funding: Pfizer (Inst), Bayer (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Eisai (Inst), Lilly (Inst), Merck (Inst), Bristol Myers Squibb (Inst), Roche/Genentech (Inst)

Masatoshi Kudo

Honoraria: Eisai, Lilly Japan, Takeda, Chugai/Roche, Bayer, AstraZeneca

Consulting or Advisory Role: Chugai/Roche, AstraZeneca, Eisai, Roche

Research Funding: Otsuka (Inst), Taiho Pharmaceutical (Inst), AbbVie (Inst), Eisai (Inst), Chugai/Roche (Inst), GE Healthcare (Inst)

Ann-Lii Cheng

Honoraria: Bayer Yakuhin, AstraZeneca, Eisai, Genentech/Roche

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bristol Myers Squibb, Bayer Schering Pharma, Eisai, Ono Pharmaceutical, AstraZeneca, Genentech/Roche, MSD, BeiGene, IQVIA, Ipsen, Roche, Omega Therapeutics, Inc

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

PRIOR PRESENTATION

Presented in part at the annual meeting of American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), Washington, DC, November 7, 2022.

M.K. and A.-L.C. contributed equally to this work.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Ying-Chun Shen, Tsung-Hao Liu, Li-Chun Lu, Shi-Ming Lin, Yi-Hsiang Huang, Sairy Hernandez, Richard S. Finn, Masatoshi Kudo, Ann-Lii Cheng

Provision of study materials or patients: Chang-Tsu Yuan, Tse-Ching Chen, Tomoharu Yoshizumi, Shinji Itoh, Noriaki Nakamura, Masaki Kaibori, Takamichi Ishii, Satoru Kakizaki, Po-Ting Lin, Chien-Huai Chuang, Hung-Wei Wang, Kun-Ming Rau, Chih-Hung Hsu, Shi-Ming Lin, Yi-Hsiang Huang, Richard S. Finn

Collection and assembly of data: All authors

Data analysis and interpretation: Ying-Chun Shen, Alan Nicholas, Chang-Tsu Yuan, Tse-Ching Chen, Shi-Ming Lin, Yi-Hsiang Huang, Sairy Hernandez, Richard S. Finn, Masatoshi Kudo, Ann-Lii Cheng

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Clinical Outcomes and Histologic Findings of Patients With Hepatocellular Carcinoma With Durable Partial Response or Durable Stable Disease After Receiving Atezolizumab Plus Bevacizumab

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Ying-Chun Shen

Speakers' Bureau: Roche, Eisai/MSD, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Ipsen, Astellas Pharma

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Roche/Genentech, Eisai

Tsung-Hao Liu

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Roche

Alan Nicholas

Employment: Genentech

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Genentech

Akihiko Soyama

Research Funding: SCREEN Holdings. Co (Inst)

Tomoharu Yoshizumi

Speakers' Bureau: AstraZeneca, Eisai, Chugai Pharma

Shinji Itoh

Honoraria: Chugai Pharma, AstraZeneca, Eisai, Takeda, Incyte Japan, Ono Pharmaceutical

Etsuro Hatano

Honoraria: Eisai, Bayer, Otsuka, Merck, Lilly, Chugai Pharma, Taiho Pharmaceutical, Ono Pharmaceutical, Incyte, AbbVie, AstraZeneca

Consulting or Advisory Role: Shionogi, Novartis, AstraZeneca

Research Funding: Eisai, Tsumura & Co

Atsushi Naganuma

Speakers' Bureau: Chugai/Roche, AstraZeneca, Eisai/MSD

Li-Chun Lu

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Pfizer

Honoraria: Roche, AstraZeneca

Chih-Hung Hsu

Honoraria: Bristol Myers Squibb, Ono Pharmaceutical, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Roche, Eisai

Consulting or Advisory Role: Ono Pharmaceutical, Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck Serono, Roche/Genentech, AstraZeneca, Daiichi Sankyo

Research Funding: Ono Pharmaceutical (Inst), AstraZeneca (Inst), MSD (Inst), Merck Serono (Inst), Taiho Pharmaceutical (Inst), Bristol Myers Squibb (Inst), BeiGene (Inst), NuCana (Inst), Johnson & Johnson (Inst), Roche/Genentech (Inst), NGM Biopharmaceuticals (Inst), Eucure Biopharma (Inst), Surface Oncology (Inst), Ipsen (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Daiichi Sankyo, Roche

Yi-Hsiang Huang

Honoraria: AstraZeneca, Gilead Sciences

Sairy Hernandez

Employment: Genentech

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Genentech

Research Funding: Genentech

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: HPK1 target as immunotherapy

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Genentech

Richard S. Finn

Consulting or Advisory Role: Pfizer, Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck, Eisai, Lilly, Genentech/Roche, AstraZeneca, Exelixis, CStone Pharmaceuticals, Hengrui Therapeutics, Medivir

Speakers' Bureau: Genentech

Research Funding: Pfizer (Inst), Bayer (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Eisai (Inst), Lilly (Inst), Merck (Inst), Bristol Myers Squibb (Inst), Roche/Genentech (Inst)

Masatoshi Kudo

Honoraria: Eisai, Lilly Japan, Takeda, Chugai/Roche, Bayer, AstraZeneca

Consulting or Advisory Role: Chugai/Roche, AstraZeneca, Eisai, Roche

Research Funding: Otsuka (Inst), Taiho Pharmaceutical (Inst), AbbVie (Inst), Eisai (Inst), Chugai/Roche (Inst), GE Healthcare (Inst)

Ann-Lii Cheng

Honoraria: Bayer Yakuhin, AstraZeneca, Eisai, Genentech/Roche

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bristol Myers Squibb, Bayer Schering Pharma, Eisai, Ono Pharmaceutical, AstraZeneca, Genentech/Roche, MSD, BeiGene, IQVIA, Ipsen, Roche, Omega Therapeutics, Inc

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, et al. : Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 382:1894-1905, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheng AL, Qin S, Ikeda M, et al. : Updated efficacy and safety data from IMbrave150: Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab vs. sorafenib for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 76:862-873, 2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kudo M: Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab followed by curative conversion (ABC conversion) in patients with unresectable, TACE-unsuitable intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Cancer 11:399-406, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kudo M, Aoki T, Ueshima K, et al. : Achievement of complete response and drug-free status by atezolizumab plus bevacizumab combined with or without curative conversion in patients with transarterial chemoembolization-unsuitable, intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma: A multicenter proof-of-concept study. Liver Cancer 12:321-338, 2023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.College of American Pathologists : Cancer Protocol Templates. https://www.cap.org/protocols-and-guidelines/cancer-reporting-tools/cancer-protocol-templates [Google Scholar]

- 6.Royston P, Parmar MK: Restricted mean survival time: An alternative to the hazard ratio for the design and analysis of randomized trials with a time-to-event outcome. BMC Med Res Methodol 13:152, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.A'Hern RP: Restricted mean survival time: An obligatory end point for time-to-event analysis in cancer trials? J Clin Oncol 34:3474-3476, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolchok JD, Weber JS, Maio M, et al. : Four-year survival rates for patients with metastatic melanoma who received ipilimumab in phase II clinical trials. Ann Oncol 24:2174-2180, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gettinger S, Horn L, Jackman D, et al. : Five-year follow-up of nivolumab in previously treated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: Results from the CA209-003 study. J Clin Oncol 36:1675-1684, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borcoman E, Kanjanapan Y, Champiat S, et al. : Novel patterns of response under immunotherapy. Ann Oncol 30:385-396, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolchok JD, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al. : Long-term outcomes with nivolumab plus ipilimumab or nivolumab alone versus ipilimumab in patients with advanced melanoma. J Clin Oncol 40:127-137, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Higuchi M, Kawamata T, Oshibe I, et al. : Pathological complete response after immune-checkpoint inhibitor followed by salvage surgery for clinical stage IV pulmonary adenocarcinoma with continuous low neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio: A case report. Case Rep Oncol 14:1124-1133, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higuchi M, Inomata S, Yamaguchi H, et al. : Salvage surgery for advanced non-small cell lung cancer following previous immunotherapy: A retrospective study. J Cardiothorac Surg 18:235, 2023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsumoto R, Arigami T, Matsushita D, et al. : Conversion surgery for stage IV gastric cancer with a complete pathological response to nivolumab: A case report. World J Surg Oncol 18:179, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu X-D, Huang C, Shen Y-H, et al. : Hepatectomy after conversion therapy using tyrosine kinase inhibitors plus anti-PD-1 antibody therapy for patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 30:2782-2790, 2023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang C, Zhu X-D, Shen Y-H, et al. : Radiographic and α-fetoprotein response predict pathologic complete response to immunotherapy plus a TKI in hepatocellular carcinoma: A multicenter study. BMC Cancer 23:416, 2023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang W, Hu B, Han J, et al. : Surgery after conversion therapy with PD-1 inhibitors plus tyrosine kinase inhibitors are effective and safe for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A pilot study of ten patients. Front Oncol 11:747950, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benci JL, Johnson LR, Choa R, et al. : Opposing functions of interferon coordinate adaptive and innate immune responses to cancer immune checkpoint blockade. Cell 178:933-948.e14, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Demaria O, Cornen S, Daëron M, et al. : Harnessing innate immunity in cancer therapy. Nature 574:45-56, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tetzlaff MT, Messina JL, Stein JE, et al. : Pathological assessment of resection specimens after neoadjuvant therapy for metastatic melanoma. Ann Oncol 29:1861-1868, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manjili MH: The inherent premise of immunotherapy for cancer dormancy. Cancer Res 74:6745-6749, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Teng MWL, Swann JB, Koebel CM, et al. : Immune-mediated dormancy: An equilibrium with cancer. J Leukoc Biol 84:988-993, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schreiber RD, Old LJ, Smyth MJ: Cancer immunoediting: Integrating immunity's roles in cancer suppression and promotion. Science 331:1565-1570, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kudo M: Drug-off criteria in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who achieved clinical complete response after combination immunotherapy combined with locoregional therapy. Liver Cancer 12:289-296, 2023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang G, Zhang W, Luan X, et al. : The role of (18)F-FDG PET in predicting the pathological response and prognosis to unresectable HCC patients treated with lenvatinib and PD-1 inhibitors as a conversion therapy. Front Immunol 14:1151967, 2023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hong CM, Jang Y-J, Lee D, et al. : Pathologic correlation of FDG PET and MR parameters in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Nucl Med 54:1474, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cui Y, Lin Y, Zhao Z, et al. : Comprehensive 18F-FDG PET-based radiomics in elevating the pathological response to neoadjuvant immunochemotherapy for resectable stage III non-small-cell lung cancer: A pilot study. Front Immunol 13:994917, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin Q, Wu HJ, Song QS, et al. : CT-based radiomics in predicting pathological response in non-small cell lung cancer patients receiving neoadjuvant immunotherapy. Front Oncol 12:937277, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van der Hulst HJ, Vos JL, Tissier R, et al. : Quantitative diffusion-weighted imaging analyses to predict response to neoadjuvant immunotherapy in patients with locally advanced head and neck carcinoma. Cancers (Basel) 14:6235, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu C, Zhao W, Xie J, et al. : Development and validation of a radiomics-based nomogram for predicting a major pathological response to neoadjuvant immunochemotherapy for patients with potentially resectable non-small cell lung cancer. Front Immunol 14:1115291, 2023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shi L, Zhang Y, Hu J, et al. : Radiomics for the prediction of pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemoradiation in locally advanced rectal cancer: A prospective observational trial. Bioengineering 10:634, 2023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anagnostou V, Landon BV, Medina JE, et al. : Translating the evolving molecular landscape of tumors to biomarkers of response for cancer immunotherapy. Sci Transl Med 14:eabo3958, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sivapalan L, Murray JC, Canzoniero JV, et al. : Liquid biopsy approaches to capture tumor evolution and clinical outcomes during cancer immunotherapy. J Immunother Cancer 11:e005924, 2023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nabet BY, Esfahani MS, Moding EJ, et al. : Noninvasive early identification of therapeutic benefit from immune checkpoint inhibition. Cell 183:363-376.e13, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Snyder A, Morrissey MP, Hellmann MD: Use of circulating tumor DNA for cancer immunotherapy. Clin Cancer Res 25:6909-6915, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Raj R, Wehrle CJ, Aykun N, et al. : Immunotherapy plus locoregional therapy leading to curative-intent hepatectomy in HCC: Proof of concept producing durable survival benefits detectable with liquid biopsy. Cancers (Basel) 15:5220, 2023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu S-Y, Dong S, Yang X-N, et al. : Neoadjuvant nivolumab with or without platinum-doublet chemotherapy based on PD-L1 expression in resectable NSCLC (CTONG1804): A multicenter open-label phase II study. Signal Transduct Target Ther 8:442, 2023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Provencio M, Serna-Blasco R, Nadal E, et al. : Overall survival and biomarker analysis of neoadjuvant nivolumab plus chemotherapy in operable stage IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer (NADIM phase II trial). J Clin Oncol 40:2924-2933, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Szabados B, Kockx M, Assaf ZJ, et al. : Final results of neoadjuvant atezolizumab in cisplatin-ineligible patients with muscle-invasive urothelial cancer of the bladder. Eur Urol 82:212-222, 2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pons-Tostivint E, Latouche A, Vaflard P, et al. : Comparative analysis of durable responses on immune checkpoint inhibitors versus other systemic therapies: A pooled analysis of phase III trials. JCO Precision Oncol 10.1200/PO.18.00114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yadav K, Lewis RJ: Immortal time bias in observational studies. JAMA 325:686-687, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhu AX, Abbas AR, de Galarreta MR, et al. : Molecular correlates of clinical response and resistance to atezolizumab in combination with bevacizumab in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Med 28:1599-1611, 2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]