Abstract

Background

Care from the family physician is generally interrupted when patients with cancer come under the care of second‐line and third‐line healthcare professionals who may also manage the patient’s comorbid conditions. This situation may lead to fragmented and uncoordinated care, and results in an increased likelihood of not receiving recommended preventive services or recommended care.

Objectives

To classify, describe and evaluate the effectiveness of interventions aiming to improve continuity of cancer care on patient, healthcare provider and process outcomes.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care Group (EPOC) Specialised Register, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL, and PsycINFO, using a strategy incorporating an EPOC Methodological filter. Reference lists of the included study reports and relevant reviews were also scanned, and ISI Web of Science and Google Scholar were used to identify relevant reports having cited the studies included in this review.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (including cluster trials), controlled clinical trials, controlled before and after studies and interrupted time series evaluating interventions to improve continuity of cancer care were considered for inclusion. We included studies that involved a majority (> 50%) of adults with cancer or healthcare providers of adults with cancer. Primary outcomes considered for inclusion were the processes of healthcare services, objectively measured healthcare professional, informal carer and patient outcomes, and self‐reported measures performed with scales deemed valid and reliable. Healthcare professional satisfaction was included as a secondary outcome.

Data collection and analysis

Two reviewers described the interventions, extracted data and assessed risk of bias. The authors contacted several investigators to obtain missing information. Interventions were regrouped by type of continuity targeted, model of care or interventional strategy and were compared to usual care. Given the expected clinical and methodological diversity, median changes in outcomes (and bootstrap confidence intervals) among groups of studies that shared specific features of interest were chosen to analyse the effectiveness of included interventions.

Main results

Fifty‐one studies were included. They used three different models, namely case management, shared care, and interdisciplinary teams. Six additional interventional strategies were used besides these models: (1) patient‐held record, (2) telephone follow‐up, (3) communication and case discussion between distant healthcare professionals, (4) change in medical record system, (5) care protocols, directives and guidelines, and (6) coordination of assessments and treatment.

Based on the median effect size estimates, no significant difference in patient health‐related outcomes was found between patients assigned to interventions and those assigned to usual care. A limited number of studies reported psychological health, satisfaction of providers, or process of care measures. However, they could not be regrouped to calculate median effect size estimates because of a high heterogeneity among studies.

Authors' conclusions

Results from this Cochrane review do not allow us to conclude on the effectiveness of included interventions to improve continuity of care on patient, healthcare provider or process of care outcomes. Future research should evaluate interventions that target an improvement in continuity as their primary objective and describe these interventions with the categories proposed in this review. Also of importance, continuity measures should be validated with persons with cancer who have been followed in various settings.

Keywords: Adult, Humans, Case Management, Continuity of Patient Care, Continuity of Patient Care/standards, Health Personnel, Health Personnel/psychology, Job Satisfaction, Neoplasms, Neoplasms/therapy, Patient Care Team, Quality Improvement, Quality Improvement/standards

Plain language summary

Interventions to improve the continuity of care in the follow‐up of patients with cancer

Cancer is a very complex disease characterised by varying clinical features and treatment phases. The continuum of cancer care includes risk assessment, primary prevention, screening, detection, diagnosis, treatment, survivorship, and end‐of‐life care. Continuity of care is defined as how one patient experiences care over time, as coherent and linked, and is the result of good information flow, good interpersonal skills, and good coordination of care. The objectives of this review were to classify, describe and determine the effectiveness of interventions tested in the literature to improve continuity of care in the follow‐up of patients with cancer.

Three main models of care (case management, shared care and interdisciplinary team) designed to improve continuity of care were identified in the 51 studies included in this review. We found no standard instruments that allow to specifically measure continuity of care in patients with cancer. According to our analysis, there was no clear evidence that the interventions assessed in this review either improved or worsened patient health‐related outcomes. Therefore, our analyses did not allow us to draw firm conclusions on the effectiveness of interventions designed to improve continuity of care in the follow‐up of patients with cancer.

Few studies reported provider and informal caregiver outcomes, as well as process of care outcomes, so they could not be regrouped for analysis. The main limitations of this review were the various differences between the included studies, especially in their study designs, interventions, participants, patients' phase of care, measured outcomes, healthcare settings, and length of follow‐up.

More relevant research is needed to sort out which interventions aiming to improve continuity of care in the follow‐up of patients with cancer are the most beneficial to improve patient, provider and process of care outcomes. Future research should identify which outcomes are the most sensitive to change and the most meaningful regarding continuity of care. Also, it would be valuable to develop a standardised instrument to measure continuity of care in patients with cancer.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Interventions designed to improve any type of continuity compared to usual care.

| Interventions designed to improve any type of continuity compared to usual care | |||

| Patient or population: cancer patients Settings: multiple settings Intervention: any type of continuity Comparison: usual care | |||

| Outcomes | Median effect size* (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) |

| Functional status Multiple scales. Scale from: 0 to 100. | The median Functional status in the intervention groups was 0 higher (1.69 lower to 2.65 higher) | 3966 (16 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 |

| Physical status Multiple scales. Scale from: 0 to 100. | The median Physical status in the intervention groups was 0 higher (0.5 lower to 0.45 higher) | 5070 (25 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 |

| Psychological status Multiple scales. Scale from: 0 to 100. | The median Psychological status in the intervention groups was 0.24 lower (3.04 lower to 0.44 higher) | 4634 (20 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 |

| Social needs Multiple scales. Scale from: 0 to 100. | The median Social needs in the intervention groups was 0.71 lower (6.96 to 0.01 lower) | 1278 (8 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 |

| Satisfaction Multiple scales. Scale from: 0 to 100. | The median Satisfaction in the intervention groups was 6.7 higher (6.7 to 11.5 higher) | 378 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 |

| Global quality of life Multiple scales. Scale from: 0 to 100. | The median Global quality of life in the intervention groups was 2.05 higher (0.06 lower to 2.14 higher) | 2622 (10 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,4 |

| *The basis for the median effect size (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. Differences between the value of each outcome before and after the intervention in each experimental group were calculated for each study. Then, the difference between the effects measured in the experimental and control group served to measure the overall effect of the intervention for each outcome. We then calculated the median value of all the measured effects across all the outcomes of the same type. Lastly, to pool the results from multiple studies, the median effect size (and its 95% confidence interval) was computed for each type of outcome, by calculating the median from all the median effects in outcomes obtained from individual studies. CI: Bootstrap confidence interval; | |||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||

1 Lack of blinding or unclear blinding 2 Heterogeneity of population, interventions and outcomes 3 Unclear sequence generation 4 Lack of blinding

Background

Recent estimates have measured significant increases in survival of patients diagnosed with cancer (Jemal 2007; Sant 2003), and advances in cancer control and the application of more effective treatment approaches should lead to further reduction in cancer death rates (Byers 1999). Along with these encouraging results come new challenges for cancer care providers; adults who report a history of cancer have higher levels of disability compared to the general population (Hewitt 2003) and an increased burden of illness, as shown by long periods of sick leave, inability to work, the general perception of poor health, and the need for help with daily activities (Yabroff 2004). In addition, cancer occurs predominantly in older persons, with a median age at diagnosis of 68 years, and the proportion of older persons with cancer is expected to increase dramatically over the next 50 years (Edwards 2002). Also, older long‐term cancer survivors have been shown to have higher rates of lung disease, diabetes, heart disease, arthritis, incontinence, chronic pain, and obesity than comparable persons who have never had cancer (Keating 2005; Yancik 2001).

Care from the family physician is generally interrupted when patients with cancer come under the care of second‐line and third‐line healthcare professionals who may also manage the patient’s comorbid conditions (Oeffinger 2006). On completion of cancer treatment, patients are often discharged back to their primary care physician, who does not always have access to information about the patient prognosis, treatment plans, pain medication, possible side‐effects of treatments, complications related to the illness, and whether the transition from curative to palliative care has occurred (Barnes 2000; Dworkind 1999). These patients often require treatment from multiple providers, including surgeons, oncologists, primary care providers, nutritionists, psychologists and social workers, who are often located in multiple settings. This situation may lead to fragmented and uncoordinated care (Earle 2006; Smith 1999). As a result, cancer survivorship has been associated with an increased likelihood of not receiving recommended preventive services or recommended care across a broad range of chronic medical conditions, such as heart failure or diabetes (Earle 2004). In addition, physicians and nurses often fail to detect patients' psychosocial needs (Hewitt 2007; Hopwood 2000; Passik 1998).

Description of the intervention

The Canadian Health Services Research Foundation commissioned a report to develop a common understanding of the concept of continuity of care for patients with chronic conditions requiring management by primary care providers and to recommend continuity measures for health system monitoring. To achieve this objective, published literature on continuity of care was reviewed and researchers, content experts, and Canadian policy makers were consulted. Continuity of care was then defined as how one patient experiences care over time, as coherent and linked; continuity being the result of good information flow, good interpersonal skills, and good coordination of care (Reid 2002). The purpose of the present Cochrane review was to identify interventions aiming to improve the three types of continuity of care in cancer patients:

informational continuity, which is the availability and use of information on prior events and circumstances to make current care appropriate,

relational continuity (also called longitudinality), which refers to an ongoing relationship between a patient and a provider, and

management continuity, which is the provision of timely and complementary services within a shared management plan (Reid 2002).

Various types of barriers to continuity of cancer care have been identified in the literature. These barriers include inadequate communication between specialists and primary care providers and insufficient information provided for long‐term follow‐up care (Barnes 2000; Dworkind 1999; Johansson 2000; Oeffinger 2006); deficient communication between healthcare providers and the patient (Airey 2002; Dumont 2005; Hack 2005); insufficient coordination of health services and healthcare providers (Bickell 2001; Earle 2004; Earle 2006); difficulties to maintain a progressive transition between curative and palliative treatments (Lofmark 2005); sub‐optimal care plans (Miedema 2003); lack of clinical guidelines (Earle 2006); and lack of education and training of healthcare providers (Alvarez 2006; Dworkind 1999).

How the intervention might work

The literature describes a number of formal programs, care delivery approaches, roles, and interventional strategies that may be used to operationalize continuity of care. Continuity of care interventions are typically multifaceted, as they often combine multiple components such as: interdisciplinary approaches (accessible through most of the illness continuum) including case conference, shared written documentation tool, and interdisciplinary care standards; comprehensive assessment of patient and family needs and strengths; patient and family education and their involvement in decision making; implementation of a care plan with measurable goals; identification and coordination of supplemental resources; integration of care through each transition; and evaluation (Beddar 1994). These various components are sometimes encompassed within specific models of care delivery, such as shared care or case management.

Shared care refers to the joint participation of primary care physicians and specialists in the planned delivery of care for patients with a chronic condition and involves enhanced information exchange over and above routine discharge and referrals (Hickman 1994; Oeffinger 2006; Smith 2009). Recent descriptive studies suggest that the majority of older patients with breast and colorectal cancer are receiving care from both primary care physicians and oncology specialists and that preventive services (e.g. monitoring for chronic conditions such as diabetes, heart disease) are more often received when a primary care physician is involved (Earle 2004; Earle 2006; Etim 2006; Ganz 2006). However, cancer screening services are received more reliably when an oncology specialist is also caring for the patient (Etim 2006; Keating 2006). For example, a shared care intervention using a collaborative home‐care record to improve communication between caregivers has led to a significant reduction in the use of hospital services and improved patient/caregiver communication (Smeenk 1998a; Smeenk 1998b; Smeenk 2000).

Case management can be defined as a client‐level strategy for promoting the coordination of human services, opportunities or benefits. The case manager, a designated person or a team, organizes, coordinates and sustains a network of formal and informal support and activities designed to optimise the functioning and well‐being of people with multiple needs (Moxley 1989). In the context of continuity of care of patients with cancer, the case manager will often be a nurse specialist. Indeed, nurse‐led follow‐up care interventions have been developed to ensure safe monitoring of disease status, continuity of care, and close liaison with primary and secondary/tertiary care teams (Moore 2006). According to this model, patients who are stable on completion of treatment are supported by nurse specialists responsible for coordinating follow‐up care and, depending on their needs, the nurse specialists would provide information, emotional support, symptom management, and referral to oncologists, palliative care teams, social care and/or primary healthcare provider (Moore 2006). Nurses can either be based in the community or in specialised oncology clinics, and are sometimes referred to as case manager, patient navigator, advanced practice nurse, breast cancer coordinator, clinical coordinator or follow‐up nurse (Fillion 2006). There are examples of successful nurse‐led follow‐up interventions applied to patients with cancer which led to a reduction in the number and severity of symptoms, an increased survival (Addington‐Hall 1992), an improved quality of life, and an improved patient satisfaction with care (Faithfull 2001).

Interdisciplinary teams refer to healthcare professionals from different disciplines working together, usually for the same organisation and in the same setting. They discuss and analyse clinical situations in order to identify common goals. They harmonise links between disciplines into a coordinated and coherent whole (Choi 2006).

Why it is important to do this review

Many authors have recognised the lack of continuity in the services needed by patients throughout their trajectory of care as one of the main problems of cancer care (Dudgeon 2007; Dumont 2005; Grunfeld 2006; Gysels 2007; Haggerty 2003). To address this problem, the Institute of Medicine (USA) (Institute of Medicine 2006) recommends that patients completing primary cancer treatment be given a comprehensive care summary and follow‐up care plan to optimise both the continuity and the coordination of their care. However, the essential elements of follow‐up care plans need to be identified, the optimal levels of involvement of various specialists and primary care providers in the creation and application of the care plans need to be determined, and ways to optimise communication between providers should also be evaluated. The current evidence provides little guidance on whether one approach is superior to another and there is a need to identify evidence that will guide health care planning and provide a framework for the follow‐up of patients with cancer. The present review will thus summarize the various approaches tested to date and evaluate their effects in order to identify the best evidence‐based interventions within the reach of existing resources.

To our knowledge, no recent systematic review has covered all aspects of continuity (relational, informational, and management) and examined all types of interventions to assess their effectiveness on patients and their relatives, on professional and informal caregivers and on care processes.

Objectives

1. To describe and classify the various interventions studied in the literature to improve continuity of care in the follow‐up of patients with cancer.

2. To determine the effectiveness of interventions aiming to improve continuity of cancer care, on patient, healthcare provider and process outcomes.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

This review considered randomised controlled trials (including cluster trials); controlled clinical trials in which participants were definitely assigned prospectively to alternative forms of health care using quasi‐randomised allocation methods, e.g. alternation, date of birth, patient identifier, or possibly assigned prospectively to alternative forms of health care using a process of randomised or quasi‐randomised allocation; controlled before and after studies and interrupted time series. Studies published in all languages were included.

Types of participants

We included studies if a majority of participants (> 50%) were adults with cancer or healthcare providers of adults with cancer.

Types of interventions

We included well‐defined interventions that explicitly stated "aiming to improve the continuity of cancer care". However, since most interventions answering a continuity problem are not necessarily described as such, we also searched among interventions described as shared care, case management, inter‐ and multidisciplinary teams, discharge planning, implementation of individual follow‐up care plans, and telephone follow‐up. Additionally, we searched among strategies to improve communication between healthcare professionals such as referral guidelines, transmission of comprehensive treatment summaries, transmission of treatment plans or patient‐held records. We excluded studies which evaluated specialised teams accessible through a single phase of patient follow‐up unless they explicitly included an intervention to improve continuity of care. If improving continuity of care was not an explicit goal of the study and if the intervention was not described as one listed here above, then it could still be included provided the data collected and results reported indicated that the intervention was aimed at improving continuity of care. To limit bias from including studies that did not specify an improvement in continuity as their objective, inclusion was initially done independently by two reviewers, and following this process, all included and excluded studies were approved by the complete panel of authors (N = 7). Included studies were expected to compare an intervention with usual care or with another intervention in equivalent settings.

Types of outcome measures

Multiple measures are needed to capture all aspects of continuity of care (Reid 2002). For the purpose of this review, the included primary outcomes were the process of healthcare services, objectively measured healthcare professional, informal carer and patient outcomes, and self‐reported measures performed with scales having known validity and reliability. Healthcare professional satisfaction was included as a secondary outcome.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Studies were identified using the following bibliographic databases, sources, and approaches.

Databases

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Issue 1, 2009, part of the The Cochrane Library.www.thecochranelibrary.com

PubMed [1948 to 2009]

EMBASE, embase.com [1947 to 2009]

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), EbscoHost [1980 to 2009]

PsycINFO, APA PsycNET [1806 to 2009]

The EPOC Specialised Register, Reference Manager

Strategy

Search strategies were developed by AG (Appendix 1; Appendix 2; Appendix 3; Appendix 4; Appendix 5; Appendix 6). The strategies were initially based on published research on continuity of care (Beddar 1994; Cox 2003; Dumont 2005; Freeman 2001; Gysels 2007; O'Hare 1993; Reid 2002; Sussman 2004) and then refined through an iterative development process whereby results of test strategies were screened for relevance. Based on this feedback, terms were added to or deleted from the final search strategies used for the review.

Search strategies are comprised of keywords and controlled vocabulary terms. Language limits were not applied. All databases were searched from database start date to February 2nd, 2009.

EPOC methodological search filter for MEDLINE, CINAHL and EMBASE was used to limit retrieval to appropriate study design and interventions of interest. See Appendices 1 to 6 for details of individual strategies and filters for each database searched.

Searching other resources

Additional studies were identified as follows:

we reviewed reference lists of relevant systematic reviews or other publications;

we contacted authors of relevant studies or reviews to clarify reported published information or seek unpublished results/data;

we contacted researchers with expertise relevant to the review topic;

we conducted cited reference searches on studies selected for inclusion in this review, studies cited in related reviews, and other relevant citations in ISI Web of Science/Web of Knowledge and in Google Scholar.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two reviewers (AG and Marie Fortier) independently selected studies to be included in the review. Disagreements regarding study inclusion were resolved by discussion between the two reviewers.

Data extraction and management

A single reviewer (AG, MM, Marie Fortier or Nadine Tremblay) initially extracted data regarding study design, sample size at randomisation, follow‐up duration, description of the interventions in all experimental groups, setting, participants' inclusion and exclusion criteria, types of cancer, patient's phase of care (pre‐treatment, treatment, discharge, surveillance, recurrence or palliative) and type of outcome reported (patient, care provider or process) using a specially designed data extraction form based on the Cochrane EPOC data collection template. A second reviewer verified all data extracted. Disagreements were generally resolved by consensus or when needed, by consulting a third reviewer.

Several investigators (N = 40) were contacted to obtain missing information to complete data extraction. If information on the outcome results could not be found (generally because the investigators did not respond to the email or sometimes because they could not locate the information), then the outcomes were excluded from the analyses.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two reviewers (AG and Marie Fortier) independently assessed risks of bias of the selected trials, except for one trial (Vallieres 2006) which was assessed by RV and Marie Fortier because AG was a coauthor in this trial. Two reviewers (AG, MF) assessed the quality of all eligible studies using the eight criteria described in the EPOC module: sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding; incomplete outcome data; selective reporting; baseline outcomes; baseline characteristics; protection against contamination; and other bias. Each criteria was answered by "Yes", "No" or "Unclear". We resolved any discrepancies in quality ratings by discussion and involvement of an arbitrator as necessary (MA or RV).

Data synthesis

Each intervention was described independently by two authors (MA and AG) with categorical variables relative to the type of continuity targeted (informational, relational and/or management), the model of care tested (case management, shared care, interdisciplinary team), and the type of interventional strategy used, as proposed in the EPOC data collection checklist for professional and organisational interventions (EPOC) (Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5). In addition, the type of targeted behaviour, the format or medium used, the deliverer of the intervention and its recipient were described using the categories proposed by EPOC in its data collection checklist (data not shown). Disagreements regarding intervention classification were resolved by discussion between the reviewers.

1. Characteristics of interventions involving case management.

| ID | Type of continuity targeted | Secondary model of cancer care | Type of targeted behaviour↕ | Structural organisational strategies § | Provider‐oriented organisational strategies * | Professional strategies ¥ | Format △ |

| Addington‐Hall 1992 | Relational Management |

‐ | 1 | 4 | 5, 6 | 1 | |

| Giesler 2005 | Relational | ‐ | 2, 4, 5, 6, 10, 11, 12 | 2, 3, 4 | 5, 6, 9, 10 | 7, 8 | 1, 3, 4, 5 |

| Given 2002 | Relational | ‐ | 2, 4, 5, 6, 10, 11, 12 | 2, 3, 4 | 5, 6, 9, 10 | 7 | 1, 2, 5 |

| Goodwin 2003 | Management Relational Informational |

‐ | 1, 2, 5, 11, 12 | 4 | 3‐12 | 2 | 1, 2, 3 |

| Koinberg 2004 | Relational Management |

‐ | 1, 2, 5, 6 12 | 4 | 3, 5, 6, 11 | 1, 2, 3 | |

| Liu 2006 | Relational | ‐ | 2, 5, 6, 10 | 4 | 5, 6, 9‐11 | 1, 2 | |

| McArdle 1996 | Relational | ‐ | 5, 9 | 1 | 5 | 1, 2 | |

| McCorkle 1989 | Relational | Home care | 1 | 4 | 1, 6, 11 | 1 | |

| McCorkle 2000 | Relational Management Informational |

Home care | 1, 2, 5, 11, 12 | 1, 2, 4 | 3, 5, 6, 10‐12 | 1, 2 | |

| McCorkle 2009 | Relational Management Informational |

‐ | 1, 2, 5, 11 | 4 | 3‐6, 9‐11 | 1, 2, 3 | |

| McKegney 1981 | Relational Management |

Home care | 2‐4, 6, 10 | 4 | 3, 10 | 1 | |

| McLachlan 2001 | Management Relational Informational |

‐ | 1, 2, 6, 11 | 2, 4 | 3, 5, 6, 9‐11 | 6 | 1, 5 |

| Moore 2002 | Relational Informational Management |

‐ | 1, 2, 6, 11 | 1, 2, 4 | 1, 3, 5‐7, 10, 11 | 2 | 1, 2, 3 |

| Mor 1995 | Relational | ‐ | 5, 6, 11, 10 | 1, 2, 4 | 5, 6, 9, 11, | 1, 2, 3 | |

| Oleske 1988 | Management Informational Relational |

Shared care | 2 | 2, 3, 4 | 1, 3‐6, 8, 11 | 2, 4 | 1, 3 |

| Rawl 2002 | Relational Management |

‐ | 2, 4, 10, 11 | 1, 2, 4 | 4‐6, 9, 10 | 1, 4 | 1, 2, 5 |

| Ritz 2000 | Relational Management |

‐ | 1, 5, 9, 11 | 1, 4 | 4‐6, 9, 10 | 1, 2 | |

| Schumacher 2002 | Relational | Home care | 3, 4, 5, 10, 12 | 1 | 5, 6 | 6 | 1, 2 |

| Skrutkowski 2008 | Relational Management |

‐ | 1, 5, 6, 11, 12 | 1, 2, 4 | 3‐6, 9, 11 | 2 | 1, 2 |

| Wells 2003 | Management | ‐ | 4, 10, 11, 12 | 1, 4 | 5 | 2 |

* 1 = Revision of professional roles; 2 = Clinical multidisciplinary teams; 3 = Formal integration of services; 4 = Skill mix change; 5 = Arrangement for follow‐up; 6 = Coordination of assessment and treatment; 7 = Transmission of comprehensive treatment summaries between providers; 8 = Transmission of treatment plans between providers; 9 = Implementation of follow‐up care plans; 10 = Care protocols, directives, guidelines; 11= Referral guidelines; 12 = Communication and case discussion between distant health professionals

§1 = Implementation of communication technologies (telephone, facsimile, telehealth); 2 = Change in medical records systems; 3 = Presence and organisation of quality monitoring mechanisms; 4 = Staff organisation

¥1 = Distribution of educational materials; 2 = Educational meetings; 3 = Local consensus processes; 4 = Educational outreach visits; 5 = Local opinion leader; 6 = Patient mediated interventions; 7 = Audit and feedback; 8 = Reminders; 9 = Marketing; 10 = Mass media

↕ 1 = Referrals; 2 = Procedures; 3 = Prescribing; 4 = General management of a problem; 5 =Patient education/advice; 6 = Professional‐patient communication; 7 = Record keeping; 8 = Financial; 9 = Discharge planning; 10 = Patient outcome; 11 = Assessment; 12 = Patient empowerment

△1 = Interpersonal; 2 = Telephone; 3 = Paper; 4 = Audio/visual; 5 = Computer / Interactive; 6 = Tele‐nursing; 7 = Diary; 8 = Group meetings; 9 = Algorithm

2. Characteristics of interventions involving shared care.

| ID | Type of continuity targeted | Secondary model of cancer care | Type of targeted behaviour↕ | Structural organisational strategies § | Provider‐oriented organisational strategies * | Professional strategies ¥ | Format △ |

| Bonnema 1998 | Management Informational |

‐ | 1, 2, 5, 9 | 4 | 3, 5, 7, 11 | 1, 3 | |

| de Wit 2001 | Informational Management |

Telephone follow‐up Patient‐held record |

2, 4, 5, 11, 12 | 1, 2 | 7, 12 | 6 | 1, 2, 3, 4, 7 |

| Grunfeld 1996 | Informational Management |

‐ | 1, 2, 9 | 1, 5, 7, 10, 11 | 1 | 3 | |

| Grunfeld 2006 | Informational Management |

‐ | 1 | 4 | 1, 3, 5, 8, 10, 11 | 1 | 3 |

| Jefford 2008 | Informational Management |

‐ | 2, 4, 7 | 2 | 7, 10, 11 | 1 | 2, 3, 5, |

| Johansson 1999 | Informational Management Relational |

Home care | 1 | 4 | 3‐7, 10‐12 | 2 | 1, 2, 3 |

| Jordhoy 2001 | Management Informational Relational |

Multidisciplinary team | 1, 2, 12 | 4 | 2, 3, 5‐12 | 2, 4 | 1 |

| Kousgaard 2003 | Management Informational |

‐ | 1, 5, 9, 12 | 7, 10, 11, 12 | 1 | 2, 3 | |

| Luker 2000 | Informational | ‐ | 1, 2, 9 | 7, 10, 11 | 1, 6 | 3 | |

| McWhinney 1994 | Informational Management |

Interdisciplinary team Home care |

1, 11 | 2, 4 | 2, 3, 5, 6, 8, 9, 11, 12 Palliative care team physician as backup resource |

3 | 1, 2, 3 |

| Mitchell 2008 | Management | Interdisciplinary team | 1 | 2, 5, 8, 12 | 3 | 2, 3, 4 | |

| Rutherford 2001 | Management Informational Relational |

‐ | 6, 9 | 1, 3, 7, 8 | 1, 6 | 1, 2, 3 | |

| Wattchow 2006 | Management Informational |

‐ | 2, 7 | 2 | 4, 5, 10 | 1, 8 | 3 |

| Wells 2004 | Informational Management |

Case management Patient‐held record |

1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 9, 11 |

1, 2, 4 | 3, 5‐7, 10‐12 | 6 | 1, 2, 3, 7 |

see footnotesTable 2

3. Characteristics of interventions involving Interdisciplinary teams.

| ID | Type of continuity targeted | Secondary model of cancer care | Type of targeted behaviour↕ | Structural organisational strategies § | Provider‐oriented organisational strategies * | Professional strategies ¥ | Format △ |

| Boyes 2006 | Informational Management |

Cancer centre care | 2, 7, 10, 11 | 2 | 10 | 3, 6, 7 | 5 |

| Hanks 2002 | Management Informational |

Shared care | 2, 6, 7, 9, 11 | 2, 4 | 2, 3, 5, 6, 8, 9, 12 | 3 | 1, 2, 3 |

| Hughes 1992 | Management Informational |

‐ | 2, 7 | 4 | 2, 5, 6, 8, 9 | 3 | 1, 7 |

| Kane 1984 | Management | ‐ | 4 | 2, 3 | 1 | ||

| Rao 2005 | Management Informational |

‐ | 1, 2, 10, 11 | 4 | 2, 3, 5, 6, 9, 10 | 1 |

see footnotesTable 2

4. Main interventional strategies used by interventions that could not be encompassed within identified models of care.

| ID | Type of continuity targeted | Main interventional strategies | Setting | Type of targeted behaviour↕ | Structural organisational strategies § | Provider‐oriented organisational strategies * | Professional strategies ¥ | Format △ |

| Beney 2002 | Management | Telephone follow‐up | Cancer centre care | 1, 2, 6 | 1, 4 | 5, 10 | 2, 3 | |

| Bohnenkamp 2004 | Relational | Communication technology | Home care | 5, 9 | 1 | 1, 4, 6 | ||

| Drury 2000 | Informational | Patient‐held records | Any setting | 7 | 2 | 6 | 3, 7 | |

| Du Pen 1999 | Management | Care protocol | Cancer centre care | 2, 3, 4, 10, 11, 12 | 2, 3 | 5, 10 | 1, 3, 9 | |

| King 2009 | Informational Management |

Assessments and feedback | Cancer centre care | 4, 6, 11 | 2, 3 | 6 | 6 | 1, 3 |

| Kravitz 1996 | Informational | Change in medical record system | Cancer centre care | 4, 7, 10, 11 | 2 | 3 | ||

| McDonald 2005 | Informational Management |

Communication technology | Home care | 1, 4, 10 | 1 | 10 | 1, 8 | 5 |

| Mills 2009 | Informational | Patient‐held records | Any setting | 4, 7, 10, 11 | 2 | 1, 6 | 3, 7 | |

| Trowbridge 1997 | Informational | Change in medical record system | Cancer centre care | 4, 6, 7, 10, 11 | 2 | 6 | 3 | |

| Vallières 2006 | Informational | Patient‐held records | 1, 3‐5, 7, 10‐12 | 2 | 6, 10, 11 | 6 | 1, 3, 7 | |

| Velikova 2004 | Informational | Assessments and feedback | Cancer centre care | 2, 4, 7, 10, 11 | 2 | 1, 2, 6, 10 | 3, 5 | |

| Williams 2001 | Informational | Patient‐held records | 7, 12 | 2 | 6 | 7 |

see footnotes Table 2

Given the clinical and methodological diversity with various models of interventions, disparate outcomes, many different care settings, and various study designs, a formal meta‐analysis could not be done. Instead, we have reported a modified form of meta‐analysis based on the median change in outcomes among studies. This approach was first suggested by Grimshaw and colleagues (Grimshaw 2004) and later used by a number of authors (Shojania 2009; Steinman 2006; Walsh 2006). We slightly adapted the methodology to give some inferences, using 200 bootstrap resamples to compute 95% confidence level bootstrap intervals.

Patient outcomes were initially combined into eight classes chosen by consensus by all the review authors: functional status, physical status, psychological status, social status, satisfaction with care, support, care needs, and global quality of life (Table 6). We decided to consider independently each sub‐scale of the quality of life instruments (i.e. Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Scale‐General, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer, and Medical Outcomes Study 36 Short form) to assess patient's functioning, physical, psychological and social status as well as global quality of life, which is a single item present in each of these scales.

5. Scales regrouped under each class of patient‐related outcomes.

| Classes of outcome measures | Instruments used to evaluate the endpoint |

| Functional status | Enforced Social Dependency Scale; Barthels Self‐Care Index; Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Scale‐General (FACT‐G); Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS); European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). |

| Physical status | McGill‐Melzack Pain Questionnaire; Brief Pain Inventory (BPI); Symptom Distress Scale (SDS); Supportive Care Needs Survey (SCNS); Brief Fatigue Inventory; Karnofsky Performance Status; Rotterdam Symptoms Checklist; Amsterdam Pain Management Index; Ferrell's Patient Pain Questionnaire; Symptom Experience Scale; WONCA Scale; General Health Rating Index; Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Scale‐General (FACT‐G); Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS); European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC); Present, Average and Worst Pain Intensity Scale; Symptom experience scale. |

| Psychological status | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS); Profile of Mood States (POMS); Supportive Care Needs Survey (SCNS); Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (SPMSQ); Uncertainty Scale (US); General Health Questionnaire; Inventory of Current Concerns (ICC); Beck Depression Inventory; State‐Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI); Impact of Event Scale (IES); Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES‐D); Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Scale‐General (FACT‐G); Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS); Supportive Care Needs Survey (SCNS); European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). |

| Social status | Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Scale‐General (FACT‐G); European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC); Supportive Care Needs Survey (SCNS). |

| Satisfaction with care | Satisfaction with Care Scale; Family Apgar Scale; Pain Treatement Acceptibility Scale; FAMCARE Scale; MacAdam's Assessment of suffering Questionnaire. |

| Support | Social Support Questionnaire (SSQ); Supportive Care Needs Survey (SCNS). |

| Global quality of life | Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Scale‐General (FACT‐G); European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC); Medical Outcomes Study 36 Short form (SF‐36); Palliative Care Quality of Life Index (PQLI); Prostate Cancer Quality of Life Instrument. |

| Care needs | Social Support Questionnaire (SSQ). |

The standard median effect size estimates across studies were calculated for patient health measures when a minimum of 4 studies were included in the analyses.

All measured outcome scales were pre‐processed to assure they were in an interval of [0‐100] and that the direction of the scales were uniform, 100 indicating a better outcome for the patient. Differences between the value of each outcome before and after the intervention in each experimental and control group were calculated for each study. Then, the difference between the effects measured in the intervention minus those in the control groups served to measure the overall effect of the intervention for each outcome. To handle the diverse set of outcomes within each individual study, we computed the median value of all the measured effects across all the outcomes of the same class. Lastly, to pool the results from multiple studies, the median effect size was calculated for each class of outcome, by computing the median from all the median effects in outcomes obtained from individual studies. Variability of this weighted median effect size was estimated using a 95% non‐parametric bootstrap confidence interval (BCI) (Efron 1993). Studies were weighted according to their sample size, so larger studies had more weight in the computation of the median effect than smaller studies. Similarly, bootstrap intervals were computed using this same weighting. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.2 (SAS Software) and figures were created using R 2.12.1 and the rmeta package (rmeta Package; R Software). This pooling strategy, based on a median instead of a mean, was chosen to be consistent with the median approach used in other reviews. Also, considering the disparate outcomes and their different scales, it seemed more appropriate to use a median instead of a mean, because it is less influenced by extreme values than would have been a mean.

As mentioned earlier, when some information on an outcome was missing to perform the calculations, then this outcome was not included in the analyses. The median effect size estimates were only calculated for patient outcome measures including four studies or more. The result significance was analysed based on the 95% BCI around the median effect size estimates.

Lastly, a descriptive analysis of single interventions on the improvement of patient health‐related outcomes was performed.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

For analyses, studies were grouped either according to the type of targeted continuity of care (informational, management, and relational) or to the type of model of care or interventional strategy being evaluated. The following comparisons were studied:

Effectiveness of interventions designed to improve continuity of care on patient outcomes:

any type of continuity of care compared to usual care;

the 3 types of continuity of care simultaneously compared to usual care;

informational continuity of care compared to usual care;

management continuity of care compared to usual care;

relational continuity of care compared to usual care.

Effectiveness of different models of care or interventional strategies:

case management model of care compared to usual care;

shared care model compared to usual care;

interdisciplinary team model of care compared to usual care;

patient held‐records compared to usual care;

telephone follow‐up compared to usual care;

communication technologies compared to usual care;

changes in medical record system compared to usual care;

care protocols compared to usual care;

assessments and feedbacks compared to usual care.

Heterogeneity of the studies pooled within each analysis was explored visually using Forest plots. Then, for each comparison, studies were stratified according to the cancer phase: 1) treatment phase, 2) after discharge from the cancer centre, 3) palliative phase, and 4) any phase (many studies included patients at different phases of cancer and presented undifferentiated results).

Sensitivity analysis

For quality of life instruments, we compared effect size estimates and bootstrap confidence intervals when each subscale was considered separately (functioning, physical, psychological and social status, global quality of life) or when they were combined within a single measure. Furthermore, physical symptoms assessed within validated instruments were also considered either independently or as a whole in the physical status class of patient health‐related outcomes.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

Electronic searching yielded a total of 6968 citations. The PubMed search generated 3502 records, CINAHL generated 1695, EMBASE generated 2472, PsycINFO generated 29, CENTRAL generated 281, EPOC Specialised Register generated 287. From these abstracts, 653 studies appeared to meet the entry criteria and were retrieved for further assessment. Fifty‐one trials published in 115 documents met all the review criteria and the remaining 541 documents were excluded. Among the excluded documents, 410 did not meet the criteria relative to the types of studies, 21 failed to meet the type of participant inclusion criteria, 104 did not evaluate an intervention judged to improve continuity of care, and 6 did not meet the criteria relative to the types of studied outcomes. All included trials were published in English.

Included studies

Description of included studies

Fifty‐one studies met all the inclusion criteria of this review (see Table: Characteristics of included studies). Nine studies included more than two treatment groups (Johansson 1999; King 2009; McArdle 1996; McCorkle 1989; McDonald 2005; Oleske 1988; Rao 2005; Rutherford 2001; Wells 2003), giving a total of 63 different interventions being tested within the 51 studies. The majority of included studies were randomised controlled trials (N = 49) and among these, eight studies allocated participants by clusters (Addington‐Hall 1992; Du Pen 1999; Goodwin 2003; Jefford 2008; Jordhoy 2001; Kousgaard 2003; McKegney 1981; Oleske 1988). Only two studies used a controlled clinical trial design (Liu 2006; Luker 2000). None of the included studies were designed as controlled before and after studies or interrupted time series.

Characteristics of participants

For included studies, sample size at randomisation ranged from 28 (Bohnenkamp 2004) to 1388 patients (Rao 2005). Twenty‐five studies included patients having any type of cancer (Addington‐Hall 1992; Beney 2002; Boyes 2006; de Wit 2001; Drury 2000; Du Pen 1999; Given 2002; Hanks 2002; Jordhoy 2001; Kane 1984; Kousgaard 2003; Kravitz 1996; McCorkle 2000; McDonald 2005; McKegney 1981; McLachlan 2001; McWhinney 1994; Mitchell 2008; Mor 1995; Oleske 1988; Rao 2005; Trowbridge 1997; Vallieres 2006; Velikova 2004; Wells 2003). Six studies included patients with various mixes of cancer types (breast, lung or colorectal cancer: King 2009; Rawl 2002; bladder, colorectal or cervical/ovarian cancer: Bohnenkamp 2004; gastric, breast, prostate or colorectal cancer: Johansson 1999; endometrial or cervical/ovarian: Rutherford 2001; breast or lung cancer: Skrutkowski 2008). Ten studies included patients having exclusively breast cancer (Bonnema 1998; Goodwin 2003; Grunfeld 1996; Grunfeld 2006; Koinberg 2004; Liu 2006; Luker 2000; McArdle 1996; Ritz 2000; Wells 2004), three only included patients with lung cancer (McCorkle 1989; Mills 2009; Moore 2002) and one of each only included patients with prostate cancer (Giesler 2005), cervical/ovarian cancer (McCorkle 2009), and colorectal cancer (Wattchow 2006). One study included participants with any type of cancer except for basal cell carcinoma of the skin (Williams 2001). Three studies did not mention which type of cancer their participants had (Hughes 1992; Jefford 2008; Schumacher 2002).

Generally, participants in all phases of cancer care were recruited and many studies followed patients going through multiple cancer phases. A few studies selected patients exclusively in the treatment phase (Boyes 2006; Drury 2000; Given 2002; Kravitz 1996; Rawl 2002; Vallieres 2006; Velikova 2004) or in the palliative phase (Addington‐Hall 1992; Du Pen 1999; Hanks 2002; Hughes 1992; Jordhoy 2001; Kane 1984; McWhinney 1994; Mills 2009; Mitchell 2008). The follow‐up duration of included studies varied between five days (Kravitz 1996) to five years (Koinberg 2004), and a few interventions targeting patients in palliative care specified that the intervention would run until participants' death (Addington‐Hall 1992; Hanks 2002; Jordhoy 2001). Twenty‐two studies were performed in the United States of America, 13 in the United Kingdom, six in Australia, three in Canada, two in the Netherlands and in Sweden, and one of each in Norway, Denmark and Taiwan (please see Characteristics of included studies).

Description of the interventions

Among the 63 tested interventions (51 studies), 20 evaluated case management models (Table 2), 14 evaluated shared care models (Table 3), and five evaluated interdisciplinary team models (Table 4), among which three tested palliative care teams (Hanks 2002; Hughes 1992; Kane 1984). Some of the reviewed interventions could not be encompassed to any main model of care but the main interventional strategy used was identified: four studies used patient‐held records (Drury 2000; Mills 2009; Vallieres 2006; Williams 2001), one used telephone follow‐up (Beney 2002), two used communication technologies (Bohnenkamp 2004; McDonald 2005), two used changes in medical record system (Kravitz 1996; Trowbridge 1997), one tested a care protocol (Du Pen 1999) and two used strategies of regular assessments and feedbacks (King 2009; Velikova 2004) (Table 5).

Nine studies targeted simultaneously informational, relational and management continuity, including six using a case management model of care (Goodwin 2003; McCorkle 2000; McCorkle 2009; McLachlan 2001; Moore 2002; Oleske 1988) and three using a shared care model (Johansson 1999; Jordhoy 2001; Rutherford 2001).

Six studies targeted relational and management continuity, and all of these used a case management model of care (Addington‐Hall 1992; Koinberg 2004; McKegney 1981; Rawl 2002; Ritz 2000; Skrutkowski 2008). Thirteen studies targeted informational and management continuity of care, nine using a shared model of care (Bonnema 1998; de Wit 2001; Grunfeld 1996; Grunfeld 2006; Jefford 2008; Kousgaard 2003; McWhinney 1994; Wattchow 2006; Wells 2004) and four using an interdisciplinary model of care (Boyes 2006; Hanks 2002; Hughes 1992; Rao 2005). Seven studies targeted relational continuity only, and used a case management model of care (Giesler 2005; Given 2002; Liu 2006; McArdle 1996; McCorkle 1989; Mor 1995; Schumacher 2002). Three studies targeted management continuity exclusively and either used case management (one study: Wells 2003), shared care (one study: Mitchell 2008) or interdisciplinary team (one study: Kane 1984) models of care. One study only targeted informational continuity, and used a shared caremodel (Luker 2000).

Included studies targeted different types of behaviour and used a diverse range of organisational (structural and/or provider‐oriented) and professional strategies. Studies that tested a case management model of care targeted various types of behaviour (Table 2) but they mainly used strategies consisting in staff organisation, arrangement for follow‐up, and coordination of assessment and treatment. Interventions that tested shared care (Table 3) generally targeted a change in referrals or procedures, and used provider‐oriented organisational strategies, such as arrangement for follow‐up, transmission of comprehensive treatment summaries between providers, and the implementation of care protocols, directives and guidelines. Educational materials were distributed to healthcare providers for some of these interventions (Grunfeld 1996; Grunfeld 2006; Jefford 2008; Kousgaard 2003; Luker 2000; Rutherford 2001; Wattchow 2006). Studies evaluating interdisciplinary teams (Table 4) used organisational strategies such as staff organisation and the creation of teams of healthcare professionals working together to care for patients. These interventions also used local consensus processes, formal integration of services, arrangement for follow‐up, coordination of assessment and treatment, and implementation of follow‐up care plans.

Nine studies included more than two experimental groups (Johansson 1999; King 2009; McArdle 1996; McCorkle 1989; McDonald 2005; Oleske 1988; Rao 2005; Rutherford 2001; Wells 2003). To avoid unit‐of‐analysis errors, only results from two of the experimental groups were included in the analysis, with one group representing the control condition and the other representing the intervention (as opposed to an active control). The intervention group was first selected based on whether it would meet the criteria for inclusion in this review. If more than two intervention groups were included based on this, then only the most intensive intervention with respect to improving continuity of care was included in the review.

Description of the outcomes

Diverse patient, provider, and process outcomes were reported across the 51 included studies of this review. Several studies reported patient health‐related measures, such as physical and psychological status, quality of life, and satisfaction (Table 6), whereas fewer studies reported providers' quality of life and psychological status. Among the processes of healthcare services, included studies measured: utilization of healthcare services; care coordination; accessibility to care; and availability and transfer of information between providers. Time to detection of recurrence, survival and place of death were also reported in a limited number of studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

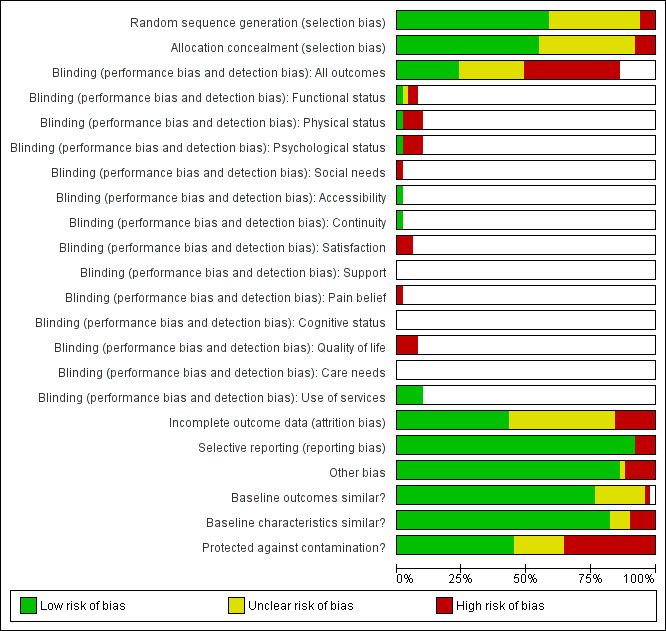

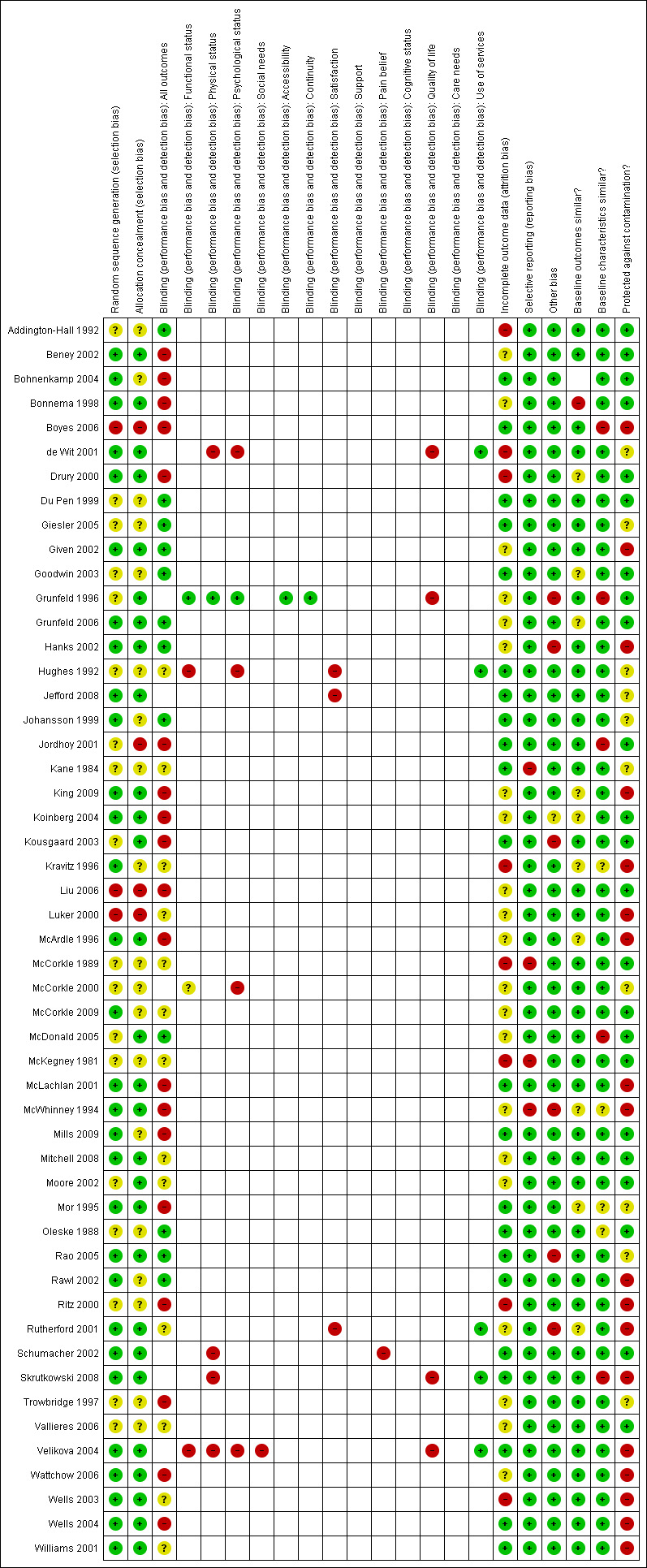

The biases most often identified in the included studies were inadequate allocation concealment, inadequate management of incomplete data, and contamination between experimental groups (see Characteristics of included studies; Figure 1; Figure 2). Also, blinding of study participants was not found in most studies.

1.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Among the 51 studies included in this review, more than half (N = 28) adequately concealed the allocation of participants or clusters. For most of the remaining studies (N = 19) the process of allocation concealment was rated as unclear whereas allocation was not explicitly concealed for four studies (Boyes 2006; Jordhoy 2001; Liu 2006; Luker 2000).

Blinding

Participants were blinded in only 12 studies (see Risk of bias tables within Characteristics of included studies).

Incomplete outcome data

Of the 51 studies included in this review, 22 adequately addressed incomplete data (see Risk of bias tables within Characteristics of included studies).

Selective reporting

Most included studies were free of selective outcome reporting (N = 47). However, four studies did not meet that criteria because at least one of the outcomes described in the methods section was not reported in the results of the published article (Kane 1984; McCorkle 1989; McKegney 1981) or because the study results were not presented in the published article (McWhinney 1994).

Other potential sources of bias

For most included studies (N = 45), outcome values and participant characteristics were similar at baseline. A single study reported a significant difference in outcomes between the intervention and control groups at baseline (Bonnema 1998) whereas five studies reported some differences in participant characteristics between the intervention and control groups at baseline (Boyes 2006; Grunfeld 1996; Jordhoy 2001; McDonald 2005; Skrutkowski 2008).

Of the 51 included studies, 23 used a design that prevented contamination between experimental groups. In the remaining studies, contamination between experimental groups was either unclear or possible, either because patients were the unit of randomisation (King 2009; Ritz 2000; Rutherford 2001; Skrutkowski 2008; Velikova 2004; Wells 2004; Williams 2001) or no stratification was done between healthcare professionals (de Wit 2001; King 2009; Given 2002), or because patients in the various groups were followed in the same setting (Ritz 2000; Rutherford 2001; Skrutkowski 2008; Wells 2003), or by the same healthcare professionals (Boyes 2006; Hanks 2002; Kravitz 1996; Luker 2000; McArdle 1996; McLachlan 2001; McWhinney 1994).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Patient health outcomes

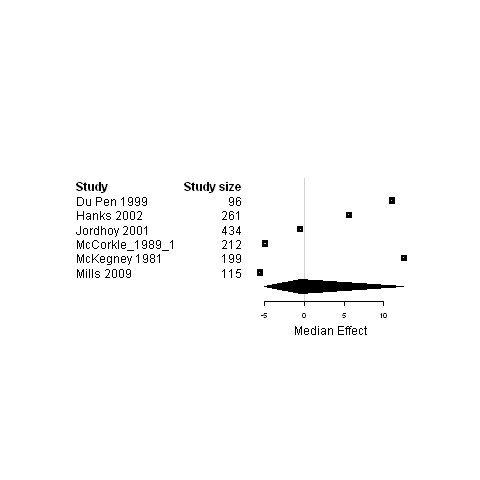

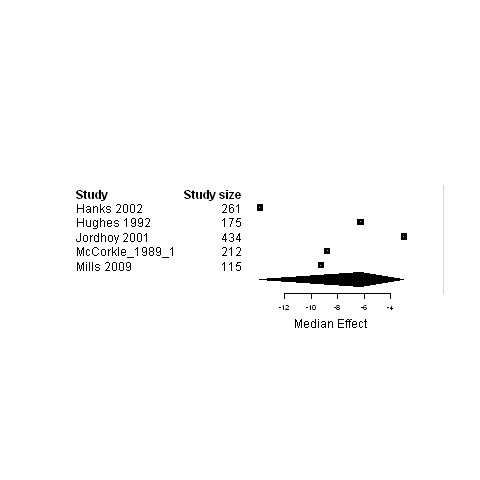

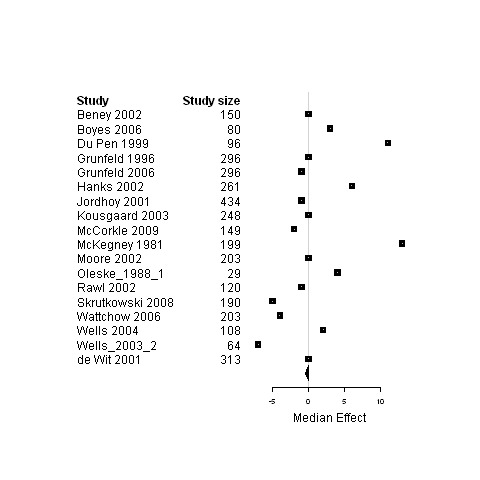

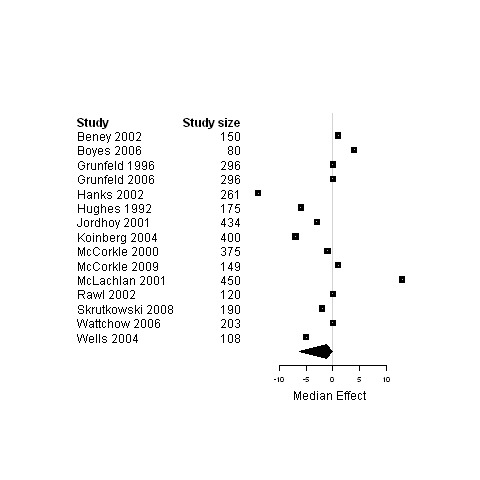

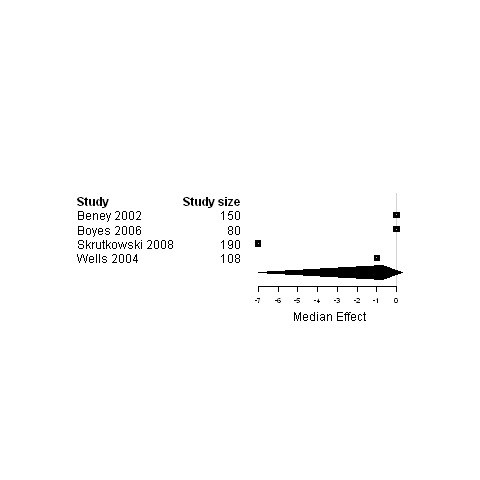

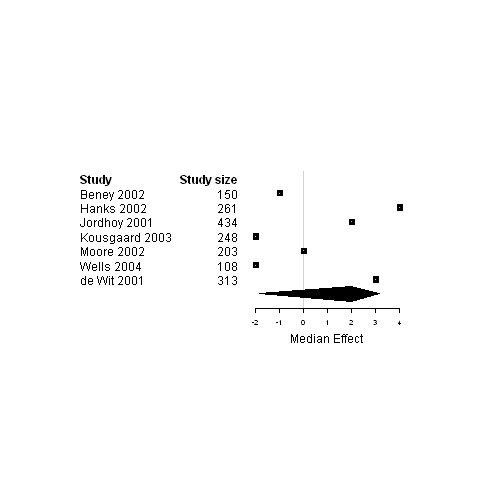

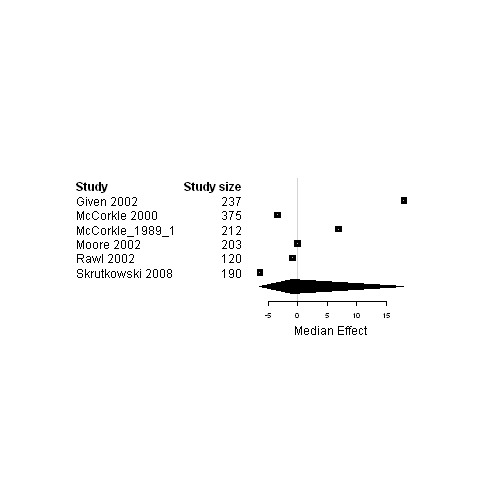

Median change in patient outcomes and 95% non‐parametric bootstrap confidence intervals (95% CI) are presented for the ninecomparisons of either studies regrouped according to the type of continuity targeted, the model of care or the interventional strategy used versus usual care (Table 7 and Figures 3 to 29). The stratification of studies according to the cancer phase (treatment phase, after discharge, palliative phase and any phase) was ineffective at reducing heterogeneity and it produced similar results as for the global analyses, except for studies conducted in the palliative phase. Therefore, only results from studies on patients in palliative care are presented (Figure 3; Figure 4; Figure 5) in addition to overall results.

6. Effectiveness of intervention by subgroup.

| Comparisons | Outcomes | Number of studies | Number of participants (total) | Standard Median Effect Sizes across studies (percent) | Confidence Intervals (bootstrap method) | Forest Plots |

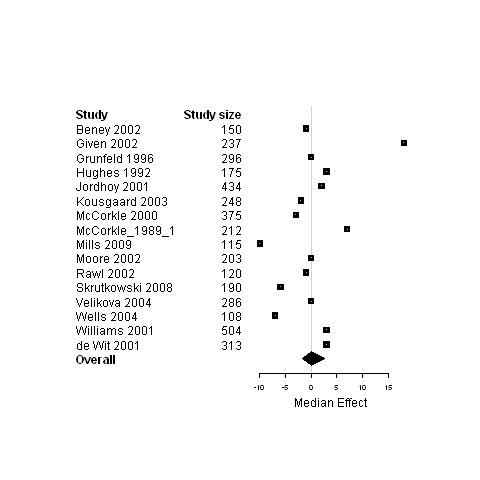

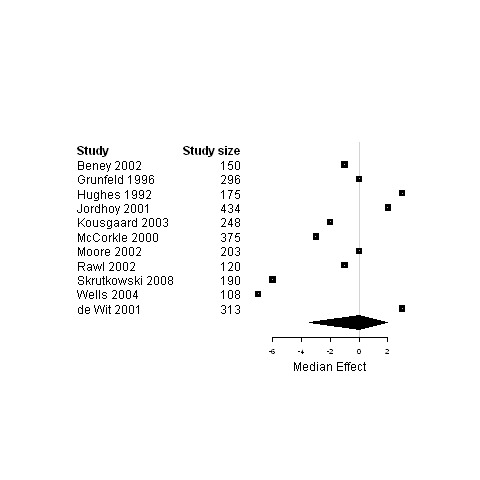

| 1. Interventions designed to improve any type of continuity of care versus usual care | Functional status | 16 | 3966 | 0 | ‐1.7 ; 2.7 | Figure 6 |

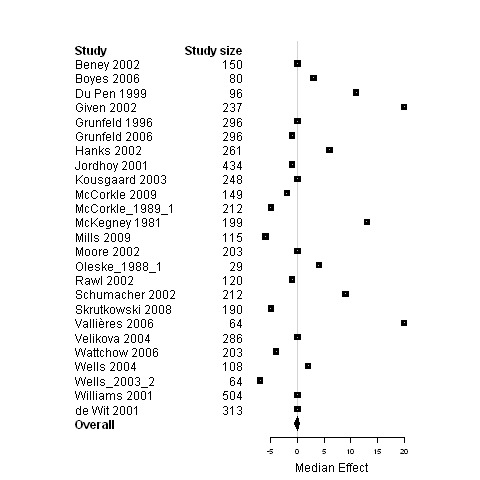

| Physical status | 25 | 5069 | 0 | ‐0.5 ; 0.5 | Figure 7 | |

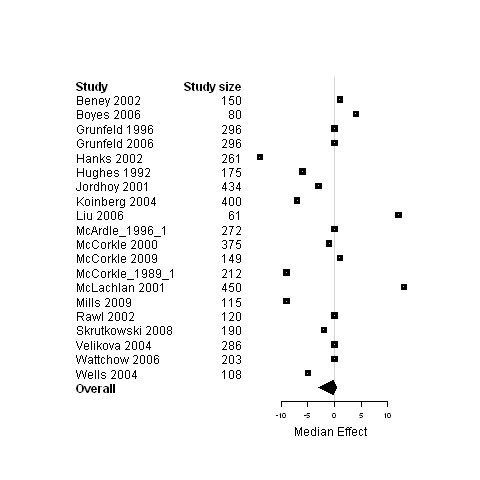

| Psychological status | 20 | 4633 | ‐0.2 | ‐3.0 ; 0.4 | Figure 8 | |

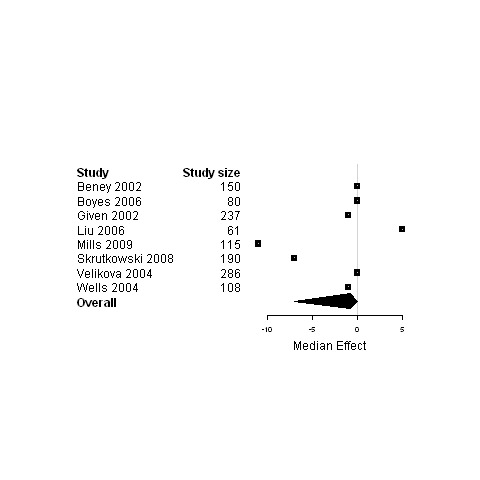

| Social status | 8 | 1277 | ‐0.7 | ‐7.0 ; ‐0.01 | Figure 9 | |

| Global Quality of life | 10 | 2622 | 2.1 | ‐0.1 ; 2.1 | Figure 10 | |

| 2. Interventions designed to improve simultaneously the three types of continuity of care versus usual care | Physical status | 4 | 815 | ‐0.5 | ‐2.4 ; 0 | Figure 11 |

| Psychological status | 4 | 1408 | ‐1.1 | ‐3.0 ; 13.1 | Figure 12 | |

| 3. Interventions designed to improve informational continuity of care versus usual care | Functional status | 11 | 3057 | 0 | ‐3.4 ; 2.7 | Figure 13 |

| Physical status | 16 | 3589 | 0 | ‐0.5 ; 0.5 | Figure 14 | |

| Psychological status | 13 | 3228 | ‐0.24 | ‐3.0 ; 0.02 | Figure 15 | |

| Social status | 4 | 589 | ‐0.01 | ‐10.7 ; 0.3 | Figure 16 | |

| Global Quality of life | 9 | 2472 | 2.0 | ‐0.03 ; 3.2 | Figure 17 | |

| 4. Interventions designed to relational continuity of care versus usual care | Functional status | 7 | 1771 | 0 | ‐3.4 ; 6.9 | Figure 18 |

| Physical status | 10 | 1985 | ‐0.5 | ‐4.9 ; 12.5 | Figure 19 | |

| Psychological status | 10 | 2663 | ‐1.1 | ‐6.7 ; 0.6 | Figure 20 | |

| 5. Interventions designed to improve management continuity of care versus usual care | Functional status | 11 | 2612 | 0 | ‐3.4 ; 2 | Figure 21 |

| Physical status | 18 | 3439 | 0 | ‐0.5 ; 0.03 | Figure 22 | |

| Psychological status | 15 | 3687 | ‐1.1 | ‐6.3 ; 0 | Figure 23 | |

| Social status | 4 | 528 | ‐0.7 | ‐7.0 ; 0.3 | Figure 24 | |

| Global Quality of life | 7 | 1717 | 2.0 | ‐1.9 ; 3.2 | Figure 25 | |

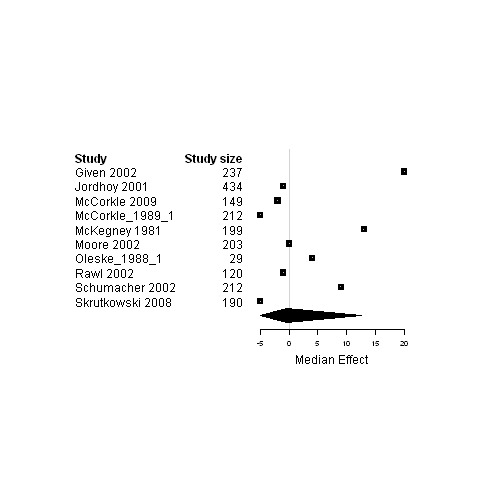

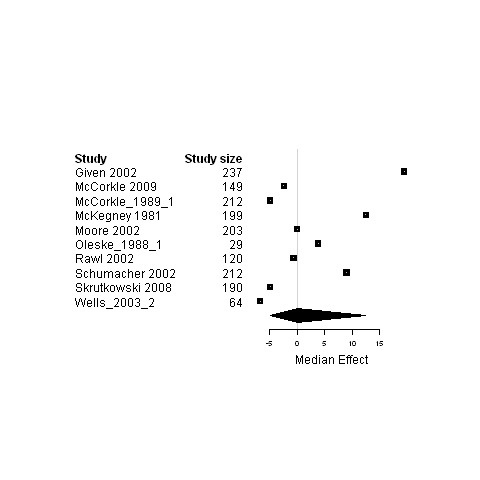

| 6. Interventions using a case management model of care versus usual care | Functional status | 6 | 1377 | ‐0.9 | ‐6.4 ; 18.0 | Figure 26 |

| Physical status | 10 | 1615 | 0 | ‐4.9 ; 12.5 | Figure 27 | |

| Psychological status | 9 | 2229 | ‐1.12 | ‐6.7 ; 13.1 | Figure 28 | |

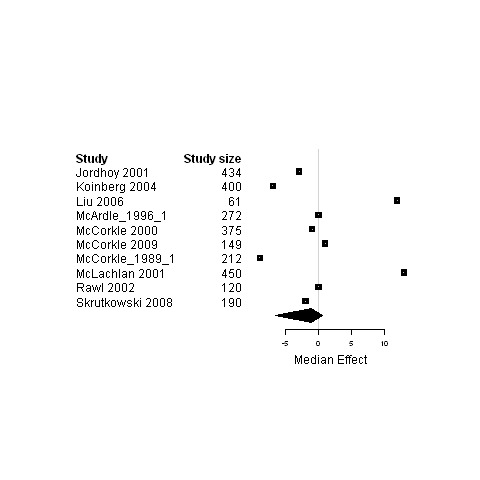

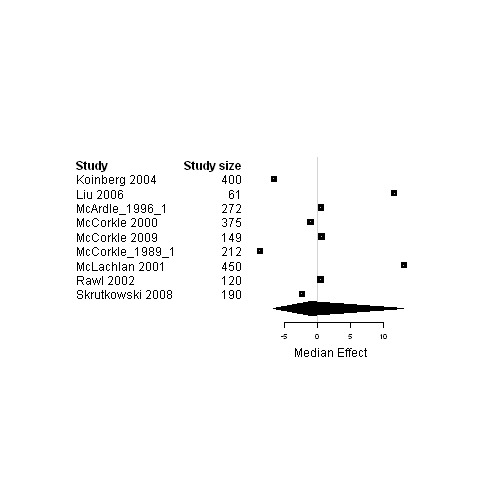

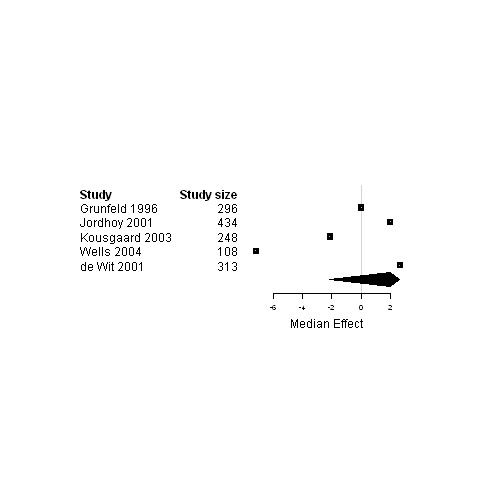

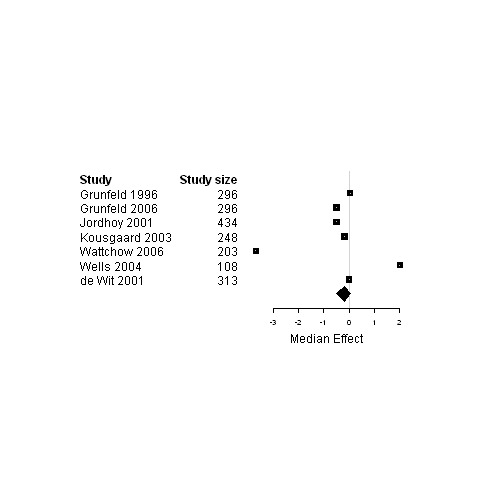

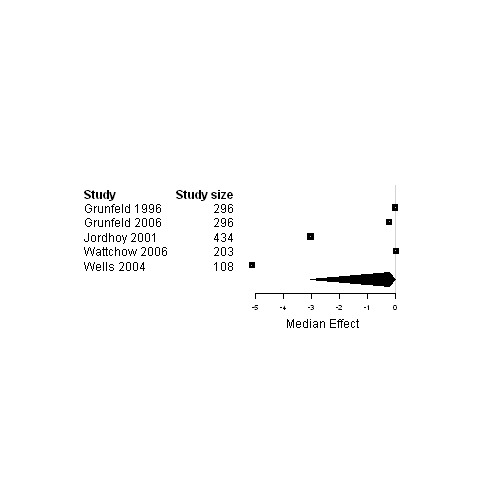

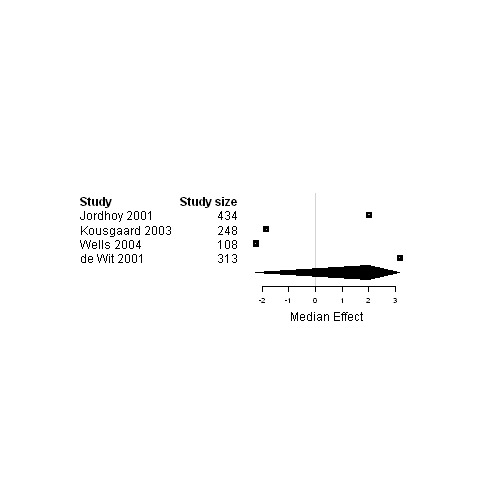

| 7. Interventions using a shared care model versus usual care | Functional status | 5 | 1399 | 2.0 | ‐2.1 ; 2.7 | Figure 29 |

| Physical status | 7 | 1898 | ‐0.2 | ‐0.5 ; 0.03 | Figure 30 | |

| Psychological status | 5 | 1337 | ‐0.2 | ‐3.0 ; 0 | Figure 31 | |

| Global Quality of life | 4 | 1103 | 2.0 | ‐2.2 ; 3.2 | Figure 32 |

The standard median effect size estimates across studies were calculated for patient health measures when a minimum of 4 studies were included in the analyses.

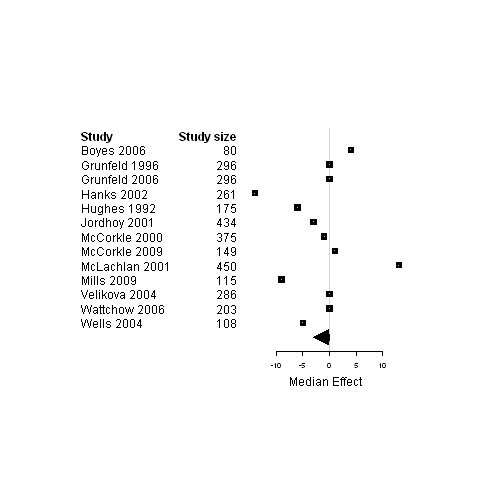

3.

Subgroup analysis of patients in palliative care ‐ Forest plot for the functional status of patients assigned to interventions designed to improve any type of continuity versus usual care.

4.

Subgroup analysis of patients in palliative care ‐ Forest plot for the physical status of patients assigned to interventions designed to improve any type of continuity versus usual care.

5.

Subgroup analysis of patients in palliative care ‐ Forest plot for the psychological status of patients assigned to interventions designed to improve any type of continuity versus usual care.

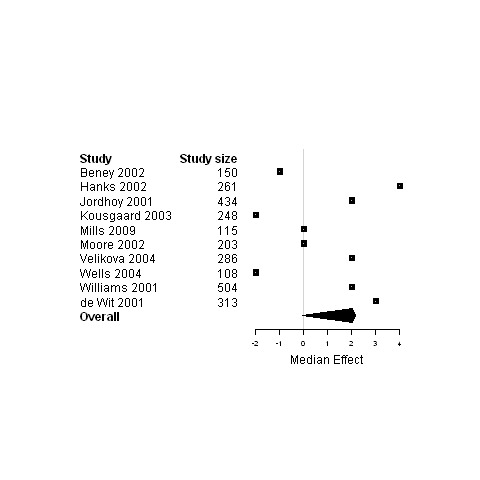

6.

Forest plot for the functional status of patients assigned to interventions designed to improve any type of continuity versus usual care.

7.

Forest plot for the physical status of patients assigned to interventions designed to improve any type of continuity versus usual care.

8.

Forest plot for the psychological status of patients assigned to interventions designed to improve any type of continuity versus usual care.

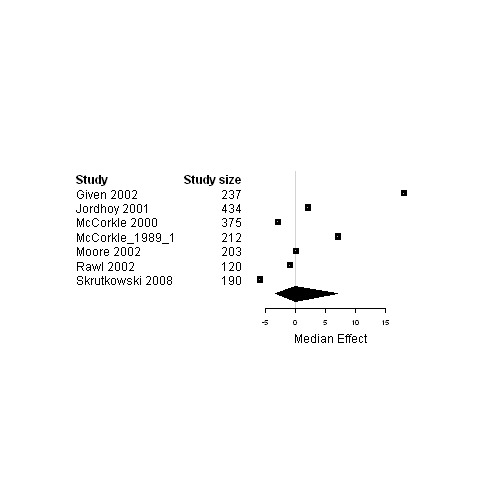

9.

Forest plot for the social status of patients assigned to interventions designed to improve any type of continuity versus usual care.

10.

Forest plot for the quality of life of patients assigned to interventions designed to improve any type of continuity versus usual care.

11.

Forest plot for the physical status of patients assigned to interventions designed to improve the three types of continuity versus usual care.

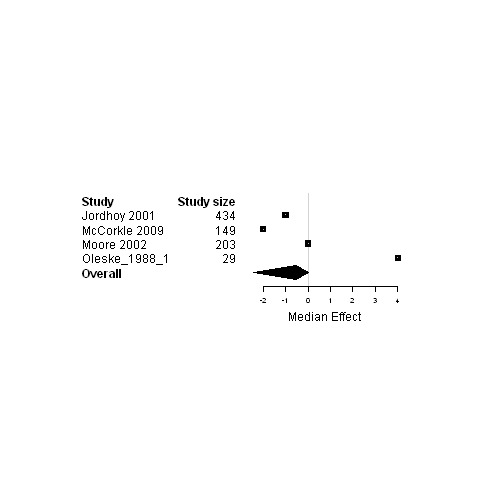

12.

Forest plot for the psychological status of patients assigned to interventions designed to improve the three types of continuity versus usual care.

13.

Forest plot for the functional status of patients assigned to interventions designed to improve informational continuity versus usual care.

14.

Forest plot for the physical status of patients assigned to interventions designed to improve informational continuity versus usual care.

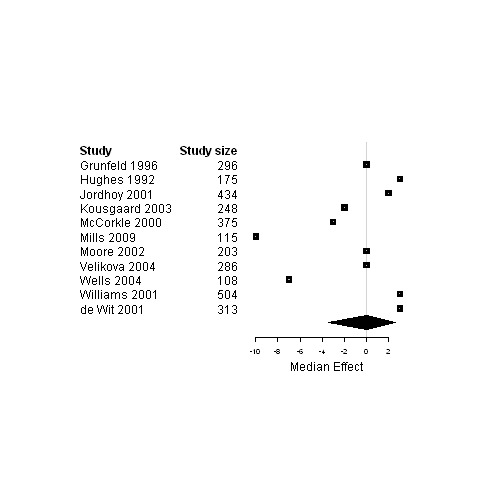

15.

Forest plot for the psychological status of patients assigned to interventions designed to improve informational continuity versus usual care.

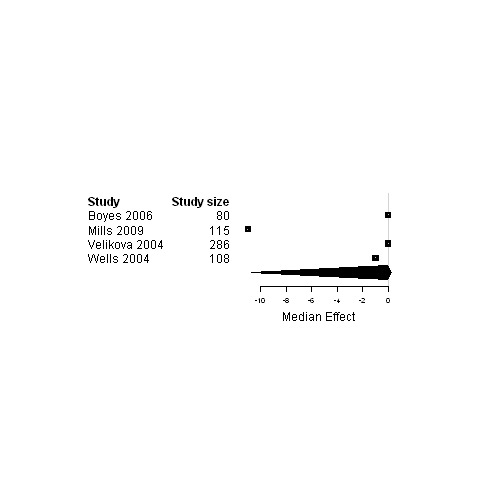

16.

Forest plot for the social status of patients assigned to interventions designed to improve informational continuity versus usual care.

17.

Forest plot for the quality of life of patients assigned to interventions designed to improve informational continuity versus usual care.

18.

Forest plot for the functional status of patients assigned to interventions designed to improve relational continuity versus usual care.

19.

Forest plot for the physical status of patients assigned to interventions designed to improve relational continuity versus usual care.

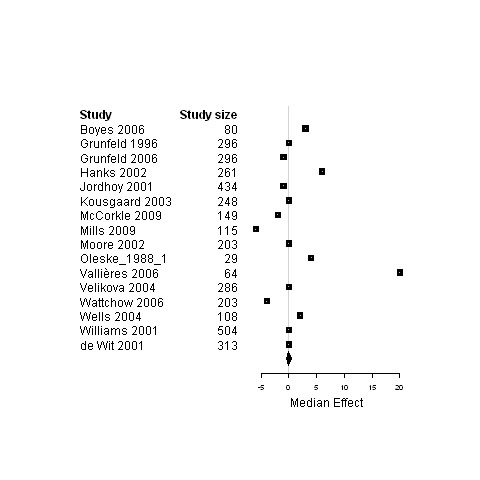

20.

Forest plot for the psychological status of patients assigned to interventions designed to improve relational continuity versus usual care.

21.

Forest plot for the functional status of patients assigned to interventions designed to improve management continuity versus usual care.

22.

Forest plot for the physical status of patients assigned to interventions designed to improve management continuity versus usual care.

23.

Forest plot for the psychological status of patients assigned to interventions designed to improve management continuity versus usual care.

24.

Forest plot for the social status of patients assigned to interventions designed to improve management continuity versus usual care.

25.

Forest plot for the quality of life of patients assigned to interventions designed to improve management continuity versus usual care.

26.

Forest plot for the functional status of patients assigned to interventions using a case management model of care versus usual care.

27.

Forest plot for the physical status of patients assigned to interventions using a case management model of care versus usual care.

28.

Forest plot for the psychological status of patients assigned to interventions using a case management model of care versus usual care.

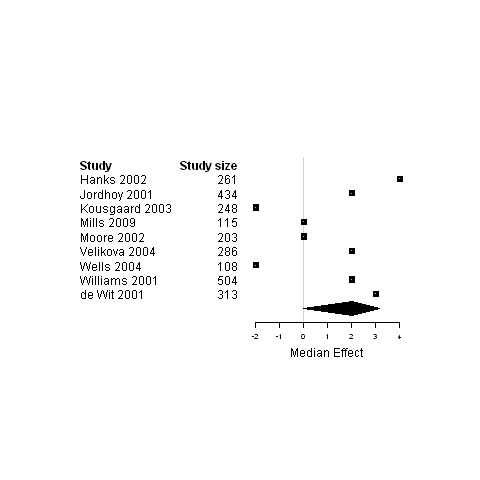

29.

Forest plot for the functional status of patients assigned to interventions using a shared care model versus usual care.

30.

Forest plot for the physical status of patients assigned to interventions using a shared care model versus usual care.

31.

Forest plot for the psychological status of patients assigned to interventions using a shared care model versus usual care.

32.

Forest plot for the quality of life of patients assigned to interventions using a shared care model versus usual care.

No difference was found when each subscale of the quality of life instruments was considered separately or when they were considered as a whole in comparisons by type of models of care (data not shown). Similarly, there was no difference when physical symptoms were considered either independently or as a whole within the physical functioning subclass in comparisons by type of models of care (data not shown).

Interventions using strategies other than those included in comparisons

Five strategies of intervention could not be pooled due to a limited number of studies included.

One study tested a telephone follow‐up (Beney 2002) 48 to 72 hours after hospital discharge for patients with cancer. No difference was found for the physical well‐being dimension of health‐related quality of life between patients who received the telephone follow‐up and those who did not (Beney 2002).

Two studies tested communication and case discussion between distant health professionals such as tele‐nursing (Bohnenkamp 2004) or email (McDonald 2005). Bohnenkamp et al. (Bohnenkamp 2004) reported that patients followed with tele‐nursing were more satisfied than patients followed with traditional home visits. McDonald et al. (McDonald 2005) found that patients assigned to a group receiving an email reminder with provider prompts, patient education material, and clinical nurse specialist outreach had significant improvement in ratings of worst pain intensity compared to patients assigned to the control group.

Two studies tested a change in medical record system that aimed to improve pain management, and they used bedside charting of pain level (Kravitz 1996) or a summary of pain assessment included in clinical charts (Trowbridge 1997). Kravitz et al. (Kravitz 1996) reported no significant difference in pain control, sleep, cancer‐related symptoms and analgesic dosing between the intervention group and the control group, whereas Trowbridge et al. (Trowbridge 1997) reported a significant change in prescription pattern and a significant reduction in the pain incidence in the intervention group.

A single study tested the distribution of a care protocol (Du Pen 1999) which consisted in a treatment algorithm for cancer pain management. This study showed that patients assigned to the pain algorithm group had a significant reduction in usual pain intensity compared to patients assigned to standard care, but no other significant difference was observed between the two groups for other symptoms nor quality of life outcomes (Du Pen 1999).

Two studies evaluated the coordination of assessments and treatment, the assessment being either of continuity (King 2009) or quality of life (Velikova 2004). The study by Velikova et al. (Velikova 2004) showed an improvement in health‐related quality of life for patients assigned to the intervention group whereas in the study by King et al. (King 2009), no significant difference was found between the intervention group and the control group.

Provider and informal carer outcome measures

A limited number of studies (N = 18) reported psychological health or satisfaction of providers or informal carers. They could not be regrouped to calculate median effect size estimates because of the high heterogeneity among studies.

Two studies reported an improvement in caregiver outcomes in the intervention group compared to the usual care group. The purpose of the study by Wells et al. (Wells 2003) was to determine if continued access to information following a baseline pain education program increased knowledge and positive beliefs about cancer pain management. In this study, a significant improvement in pain beliefs of the caregiver was found in the intervention group compared to the usual care group (Wells 2003). The study by Hughes et al. (Hughes 1992) assessed the cost‐effectiveness of a Veteran Affairs Hospital‐based Home Care Program for terminally ill patients with informal caregivers. A significant increase in caregiver satisfaction with care was found in the intervention group at one month follow‐up compared to the customary care (Hughes 1992).

Two studies reported significantly increased provider satisfaction in the intervention group compared to the standard care group. The study by de Wit et al. (de Wit 2001) examined the effectiveness of a Pain Education Program offered by nurses to cancer patients with chronic pain. District nurses of patients from the intervention group were significantly more satisfied with patient's pain treatment than nurses of patients from the usual care group (de Wit 2001). The study by Jefford et al. (Jefford 2008) assessed the impact of sending information to general practitioners about their patient's chemotherapy regimen. General practitioners assigned to the intervention group reported a significant increase in satisfaction and greater levels of confidence in treating those patients with chemotherapy adverse effects at follow‐up compared to general practitioners receiving the usual correspondence (Jefford 2008).

Process of care outcome measures

Accessibility to care and continuity of care

Patient satisfaction with service delivery, consultation and continuity of care was assessed with an instrument developed in the United Kingdom by the College of Health, in a study by Grunfeld et al. (Grunfeld 1996). This study aimed to evaluate the effect on patient satisfaction of transferring the primary responsibility for follow‐up of women with breast cancer in remission from hospital outpatient clinics to general practice. Patients assigned to the general practice group indicated greater satisfaction than did patients in the hospital group. Notably, more patients in the general practice group than in the hospital group could see the doctor on the same day for urgent problems and had enough time to discuss problems with their doctor. Furthermore, almost 90% of patients in the general practice group saw a doctor who knew them well at their follow‐up visit, compared to approximately 50% of patients in the hospital group. Lastly, there was a significant increase in the proportion of patients who were satisfied with continuity of care in the general practice group (Grunfeld 1996).

Place of death

Only four studies (Hughes 1992; Jordhoy 2001; Kane 1984; Moore 2002) reported the place of death of patients with cancer. The study by Hughes et al. (Hughes 1992) assessed the cost‐effectiveness of a Veteran Affairs Hospital‐based Home Care program for terminally ill patients. In the study by Kane et al. (Kane 1984) terminally ill cancer patients were randomly assigned to receive hospice care provided both in a special inpatient unit and at home or conventional care (Kane 1984). The study by Jordhoy et al. (Jordhoy 2001) evaluated a comprehensive palliative care program in patients who had incurable malignant disease and an expected survival of two to nine months. The study by Moore et al. (Moore 2002) assessed the effectiveness of a nurse‐led follow‐up in the management of patients with lung cancer who had completed their initial treatment and were expected to survive for at least three months. For two of these studies, deaths occurred significantly more frequently at home in the intervention group than in the control group (Jordhoy 2001; Moore 2002) whereas in one study, patients assigned to the intervention group spent 3.5 fewer days in the hospital prior to their death, compared to the control group patients (Hughes 1992). In the study by Kane et al. (Kane 1984), no significant difference was observed between the intervention and control groups in the number of deaths at home and at the hospital.

Other process of care outcome measures

Overall, very few studies reported process of care measures at baseline and during the follow‐up period. No pooled analysis was performed for process of care measures because of a high heterogeneity among studies, few process of care data available and context‐dependent measures. Only three studies reported a significant difference between the intervention and the control groups for process of care measures. The study by Hanks et al. (Hanks 2002) assessed the effectiveness of a hospital Palliative Care Team in the setting of a teaching hospital trust in England. In this study, the advice and support provided by a multidisciplinary specialist Palliative Care Team was compared with limited telephone advice. Within the study period, 48% of patients were discharged from hospital to their home. The patients in the complete Palliative Care Program received significantly more general practitioner visits during the period of time spent at home, compared to patients in the limited telephone advice group (Hanks 2002). The study by Jordhoy et al. (Jordhoy 2001) assessed the impact of comprehensive palliative care on patient's quality of life. The intervention was based on cooperation between a palliative medicine unit and the community services to enable patients to spend more time at home and to die there if they preferred. In that study, the time spent in nursing homes during the entire observation period and in the last month before death was less for patients in the intervention group, compared to those in the control group (Jordhoy 2001). The purpose of the study by Oleske et al. (Oleske 1988) was to determine the impact of modest changes in the home health system on patients with cancer. Patients from two certified home health agencies in two regions of Illinois (USA) were either assigned to oncology nurse specialists with continuing education on cancer, to continuing education on cancer alone or to observation only. The mean number of nurse visits to cancer patients during the two year duration of the study significantly declined in the groups who received the intervention and increased in the observation only group (Oleske 1988).

Descriptive analysis of single intervention on the improvement of patient health‐related outcomes

The significant improvements in one or more classes of patient health‐related outcomes are reported by type of model of care for all 51 studies included in this review.

Case management

Twelve out of the 20 studies assessing case management models of care (Table 2) reported significant improvements in one or more classes of patient health‐related outcomes, during the study follow‐up period.

Functional status

The study by Given et al. (Given 2002) was conducted in chemotherapy clinics of two comprehensive and two community cancer centres and evaluated a nursing intervention in patients undergoing an initial course of chemotherapy who reported pain and fatigue at baseline. Patients assigned to the intervention group reported a significant improvement in social functioning compared to those assigned to the usual care group (Given 2002). One study by McCorkle et al. (McCorkle 1989) assessed the effect of home nursing care for patients with progressive lung cancer. The home nursing care group had significantly less distress and greater independence six weeks longer compared to the office care group (McCorkle 1989). The study by Giesler et al. (Giesler 2005) evaluated a nurse‐driven cancer care intervention based on an interactive computer program to help patients with prostate carcinoma identify their quality of life related needs and provide education and support according to their identified needs. Patients who received the intervention experienced significant long‐term improvements in quality of life outcomes related to sexual functioning compared to patients who received standard care (Giesler 2005). The study by Moore et al. (Moore 2002) tested the effectiveness of a nurse‐led follow‐up in the management of patients with lung cancer who had completed their initial treatment and were expected to survive for at least three months. Patients assigned to the intervention group had significantly better scores for emotional functioning compared to those assigned to the conventional care group (Moore 2002).

Physical status