Abstract

Understanding estrogen receptor (ER) signaling pathways is crucial for uncovering the mechanisms behind estrogen-related diseases, such as breast cancer, and addressing the effects of environmental estrogenic disruptors. Traditionally, ER signaling involves genomic events, including ligand binding, receptor dimerization, and transcriptional modulation within cellular nuclei. However, recent research have revealed ERs also participate in non-genomic signaling pathways, adding complexity to their functions. Researchers use advanced fluorescence-based techniques, leveraging fluorescent probes (FPb) to study ER dynamics in living cells, such as spatial distribution, expression kinetics, and functional activities. This review systematically examines the application of fluorescent probes in ER signaling research, covering the visualization of ER, ligand-receptor interactions, receptor dimerization, estrogen response elements (EREs)-mediated transcriptional activation, and G-protein-coupled estrogen receptor (GPER) signaling. Our aim is to provide researchers with valuable insights for employing FPb in their explorations of ER signaling.

Keywords: Endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs), ER dimerization, Estrogen receptor, Fluorescent probes, FRET/BRET biosensors

INTRODUCTION

The estrogen receptor (ER) signaling pathway is pivotal in mediating the broad physiological effects of estrogen. These effects span the development and maintenance of secondary sexual characteristics, regulation of reproductive functions, bone density, cardiovascular health, and cognition (1). There are three primary subtypes of ER: ER alpha (ERα), ER beta (ERβ), and the G-protein-coupled estrogen receptor (GPER) (1). ERα and ERβ are comprised of several domains, including the activation function-1 (AF-1), the DNA-binding domain (DBD), the hinge region, the ligand-binding domain (LBD), and the activation function-2 (AF-2), each imparting distinct properties that influence ER behavior (2). While ERα and ERβ exhibit certain similarities, they vastly differ in their tissue distribution and functionalities; ERα is primarily expressed in female reproductive tissues, while ERβ is predominantly located in male reproductive tissues, with both subtypes responsive to estrogen (3, 4). Distinct from ERα and ERβ, GPER features seven transmembrane domains and is embedded within the cell membrane, instigating signaling cascades in response to estrogenic hormones, and is widely expressed in various tissues beyond just the reproductive system (5).

The ER signaling pathway facilitates its effects through two main mechanisms: genomic and non-genomic pathways. The genomic effects, considered the classical conduit of ER signaling, primarily involve the subtypes ERα and ERβ. In this mechanism, ERs bind to estrogen molecules, which evoke conformational changes leading to their dimerization and subsequent migration into the cell nucleus. Inside the nucleus, they associate with specific DNA sequences known as estrogen response elements (EREs), thereby modulating gene expression. This modulation encompasses the recruitment of coactivators or corepressors, influencing cellular functions such as proliferation, differentiation, and survival. The genomic effects exhibit tissue-specific manifestations, accounting for the diverse physiological responses across different target tissues (1). The canonical stages of ER signaling—ligand binding, receptor dimerization, and gene expression modulation—are interconnected yet do not always correlate proportionately with one another. For example, the stability of ER dimers is significantly affected by the nature of the ligand rather than its binding affinity (6). Moreover, studies suggest that ER phosphorylation and the activity of other transcriptional activators can influence ERE activation, and the binding affinity of ERα does not necessarily align with estrogen-induced transcriptional activation (7). On the other hand, non-genomic effects of ER signaling encompass various signaling cascades that operate independently of gene transcription, such as the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt pathway, and the cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) pathway (8). These pathways regulate cellular functions and are often mediated by the GPER or cytoplasmic ERs. As a result, non-genomic pathways enable rapid cellular responses as they directly participate in cell signaling.

A dynamic interplay exists between genomic and non-genomic effects, necessitating the independent study of each signaling phase to fully comprehend the intricacies of ER signaling (1, 9). Furthermore, ERs can interact with other classes of steroid ligands, expanding the scope of their influence (10). Endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) that interfere with ER signaling, especially those modulating the action of the female hormone 17β-estradiol (E2), are categorized as either natural or synthetic compounds found in a variety of environmental matrices, including food, air, water, and soil (11, 12). Identifying EDCs is paramount for pinpointing the causes of estrogenic diseases and for the future prevention and prognosis of these diseases among the general populace. To this end, diverse screening methods have been devised to detect EDCs (13, 14).

The fluorescent probe (FPb) represents a molecule or compound that emits fluorescent light, employed in the study of proteins of interest (POI). FPb, upon absorbing light at a specific wavelength, emits light at a longer wavelength as it reverts to its ground state. These probes have proven indispensable in various scientific and medical fields, facilitating the detection and visualization of specific molecules, cells, or structures. Notable types of FPb include antibodies, fluorescent proteins (FPt), self-labeling protein tags (SLP), and fluorescent dyes (FDy) (15, 16). Antibodies are incredibly valuable for targeting POIs and detecting protein post-translational modifications, such as phosphorylation and methylation. They can monitor the endogenous activity of POIs, offering insights free from overexpression or genetic manipulation effects. For fluorescent applications, antibodies can be conjugated with diverse fluorophores or single-stranded oligonucleotides for proximity ligation assays (PLA). Although their substantial size can alter the physiological behavior of the POIs upon bonding, and their usage involves invasive methods that may induce cytotoxicity and complicate the observation of POI alterations in living cells, these limitations are relatively minor compared to their significant benefits (17).

FPt and SLP constitute genetically encoded methodologies for tagging POIs. A limitation of these approaches is the potential over-representation of POIs above endogenous levels, which may also require time to mature post-expression. Nonetheless, they offer substantial benefits, including high specificity in tagging POIs, minimal cytotoxicity due to their noninvasive nature, and the diminutive size of the tag, which minimally disrupts cellular processes. These attributes simplify the observation of intracellular POI dynamics in living cells, enabling researchers to trace real-time molecular interactions and cellular changes. The tagging technique utilizing fluorescent proteins (FPt) enables the concurrent expression of the fluorescent protein alongside the protein of interest (POI), thereby eliminating the need for separate ligand processing, in contrast to self-labeling protein (SLP) tagging methods. However, FPt is its vulnerability to photobleaching under strong fluorescence stimulation, which requires caution (18). Self-labeling protein tags (SLP), such as Halotag, SNAP-tag, and CLIP-tag, facilitate the specific and covalent attachment of proteins with suitable ligands, including fluorescent dyes (19). Although SLP tagging methods necessitate the separate introduction of the fluorescent dye (FDy) ligand into the ligand-binding pocket, potentially resulting in nonspecific binding due to some fluorophores’ lack of target specificity, they afford flexibility in utilizing diverse colors or ligands for various experiments. This flexibility is advantageous, as it permits alterations in the experimental design without necessitating the cloning of a new construct for each change in FPt color, and it ensures photostability (20). Fluorescent dyes (FDy) are minute organic molecules that emit light upon excitation. Exhibiting photostability, high quantum yield, and significant cell permeability, these dyes efficaciously penetrate cell membranes, accessing POIs within living cells (19). Furthermore, their structural simplicity and synthesis ease facilitate the creation of a multitude of compounds, enhancing their experimental applicability (21).

Fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) and bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) are techniques extensively employed in molecular biology and biophysics to examine interactions among biomolecules. These phenomena rely on energy transfer between two fluorophores to detect molecular interactions, conformational alterations, and proximity among biomolecules. FRET involves a donor fluorophore that, upon excitation, conveys energy to an acceptor fluorophore situated within 1-10 nanometers. This transfer results in decreased fluorescence intensity of the donor and increased fluorescence of the acceptor (22). Conversely, BRET utilizes a bioluminescent donor, typically a luciferase enzyme, that emits light through a chemical reaction with a luciferase substrate. The fluorescent acceptor subsequently absorbs this light and emits fluorescence at a longer wavelength. Both FRET and BRET exhibit high sensitivity to the distance and orientation between donor and acceptor molecules, rendering them invaluable for investigating protein-protein interactions, protein-ligand interactions, and monitoring intracellular signaling events in living cells (22).

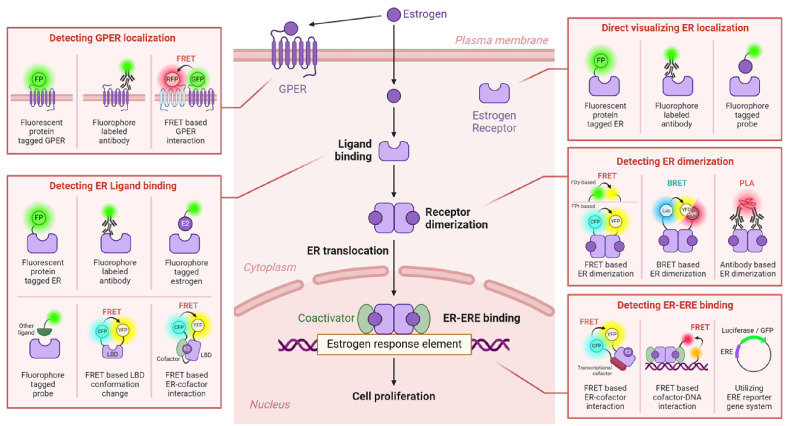

In this review, we catalogued studies that employed fluorescent probes (FPbs) to probe ER signaling. We organized these studies based on specific physiological phases in the ER signaling pathway: ER visualization, ligand-receptor binding, ER dimerization, ERE-mediated transcriptional activation, and GPER signaling. Our objective is to systematically outline the visual studies of the ER signaling pathway, thereby aiding future research on this complex subject. The holistic schematic of these methodologies is depicted in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Schematic overview of fluorescence-based techniques for ER signaling dynamics. This figure offers a visual representation of the use of fluorescence-based approaches in studying the five principal estrogen receptor (ER) signaling pathways. Each pathway is outlined within a pink frame and features an array of techniques for exploring ER dynamics. Notable methods demonstrated include fluorescent protein tagging (FPt), fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET), bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET), and proximity ligation assay (PLA). Additionally, the involvement of 17β-estradiol (E2) in these assays is highlighted.

DIRECT VISUALIZATION OF ESTROGEN RECEPTOR

The creation of a fluorescent probe for direct visualization of the ER has markedly advanced our understanding of the dynamics of ER and its implications in diverse diseases. The engineering of GFP-tagged ER constituted a pivotal advancement, facilitating the monitoring of ER activity alterations in response to various ligands (23). Researchers have subsequently employed fluorescence-based techniques extensively in studying the roles of ER, augmenting the specificity and reliability of these methods through the creation of fluorescence-based, ER-selective probe arrays to evaluate ER expression and subcellular localization (24, 25).

Further innovations have involved the integration of ER tagged with fluorescent proteins into various ER-positive cell lines and the utilization of immunofluorescence (IF) techniques. These approaches have enabled comprehensive examinations of ER activity within different cellular organelles, including the nucleus, mitochondria, and cytoplasm. Examinations have spanned a wide spectrum of biological inquiries, from scrutinizing ER expression patterns and degradation under the influence of various ER agonists and antagonists to investigating ER-mediated signaling pathways (26-29). At the tissue level, fluorescence-based visualization of ER has facilitated precise mapping of its expression in diverse tissues, offering significant benefits for tissue-level analyses (30). The domain of ER visualization and activity assays has been extended into in vivo studies, with the development of several fluorescence-based probes and systems. A landmark achievement was the invention of an ER-specific detection probe employing near-infrared (NIR) technology, which showed high binding affinity to ERα both in vitro and in vivo, enabling precise ER detection (31). Recent advancements encompass NIR-based probes targeting ERβ and a multifunctional probe designed for the simultaneous detection of both ER and progesterone receptor (PR), facilitating visual comparison of hormone receptor colocalization and enhancing our understanding of intercellular signaling networks (32, 33). These NIR-based probes have proven to be invaluable for in vivo ER detection and the early diagnosis of ER-related diseases, especially breast and prostate cancers, providing a method for both quantitative analysis and visual assessment of ER expression levels. This technological evolution supports continuous efforts in treating and comprehending ER-related pathologies.

Direct visualization of the estrogen receptor (ER) through fluorescence techniques has not only enabled the identification of the receptor’s localization but also facilitated the characterization of its sequence and specific domains. In investigations centered on the activation function-1 (AF-1) domain, GFP-tagged ERs and counterpart ERs lacking the AF-1 domain were constructed to evaluate their responses to estrogen, illustrating that the structural integrity of the AF-1 domain affects ligand binding, with phosphorylation at the serine 118 position being pivotal for this interaction. Furthermore, peptidyl-prolyl isomerase Pin1’s involvement in these processes was elucidated (34, 35). Subsequent fluorescence-based experiments have shed light on the role of the AF-1 domain in essential cellular and tissue functions, such as puberty-associated ductal growth, transcriptional regulation, tubulin interaction, and responses to epidermal growth factor (EGF) (36-39). Investigations also delved into the AF-2 domain, unveiling its contributions to growth, development, and ligand binding utilizing fluorescence-based methodologies (36, 40). Notably, antagonist-induced, SUMOylation-mediated transcriptional repression of ER, associated with the cofactor binding segment of the AF-2, was explored using bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) techniques to detect their dimerization (41).

Furthermore, fluorescence-based visualization has shed light on the crucial role of the hinge domain, which bridges the DNA-binding domain (DBD) and the ligand-binding domain (LBD). Experiments that excised this domain from GFP-ER validated its contribution to cytoplasmic localization and identified a nuclear localization signal (NLS) sequence, thereby underscoring its importance in ER localization and function (27, 40, 42, 43). These inquiries have further elucidated the hinge domain’s engagement in critical ER mechanisms, including degradation, ligand interaction, tether-mediated nuclear localization, and communication with nuclear elements. These findings emphasize the paramount importance of fluorescence-based visualization in unraveling the regulation and functional contributions of individual ER domains within cellular processes, substantially enriching our comprehension of ER biology and the dynamics between its domains and cellular activities.

FLUORESCENT PROBE-BASED DETECTION OF ESTROGEN RECEPTOR-LIGAND BINDING

The interaction between ER and its ligands is pivotal for initiating signal transduction, thereby eliciting a cascade of physiological responses (1). In the realm of oncology, ligand binding to ERs decisively influences the development and progression of cancer, spurring extensive research aimed at hindering this interaction to thwart cancer growth (30). Moreover, the perturbation of the endocrine system by endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) is associated with various diseases, catapulting ER-ligand interactions to the forefront as a viable approach for disease treatment and EDC screening (12, 14). This research has not only augmented our comprehension of ER biology but has also shed light on the intricacies of ligand binding and the receptor’s reaction to diverse ligands (29). As a result, validating and comparing the impacts of ER agonists and antagonists have become imperative in confronting ER-related diseases. To support these endeavors, a plethora of methods and instruments have been innovated for detecting and screening ER-specific binding sites. These tools are utilized in vitro and at the single-cell level, augmenting our grasp of ER binding dynamics and paving new pathways for pharmaceutical interventions against ER-associated cancers and ailments (44, 45). The exploration of ER-ligand binding has precipitated the employment of multiple experimental modalities, including fluorescence techniques, to inspect in vitro the interactions between ER and its ligands. The advent of fluorescence-based microarrays and fluorescent probes has facilitated more granular studies of these interactions (46, 47). Fluorescently tagged steroid hormones now allow the specific and visual discrimination of different ligands’ binding, both agonists and antagonists, to ERs. This strategy underscores the efficacy of ER binding assays and imaging studies employing fluorescent probes as potent instruments for identifying ER-targeting drugs and screening for EDCs, alongside interactions with estradiol (48).

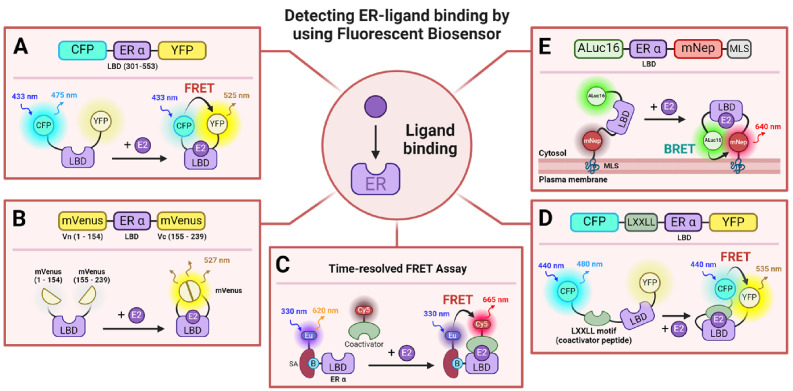

Furthermore, fluorescence polarization techniques have been adopted for ER binding detection assays and EDC screening, further broadening the arsenal for these pivotal investigations (49, 50). These methodologies highlight the crucial function of biophotonic technologies in elucidating ER dynamics and their implication in healthcare research. Researchers have leveraged FRET and BRET to visualize and scrutinize ligand binding to the ER. When a ligand binds to the ER’s LBD, this elicits a significant conformational alteration in helix-12, propelling the receptor into a transcriptionally active configuration (51-53). To trace these modifications upon agonist and antagonist binding, FRET-based biosensors were conceived. These biosensors incorporate cyan fluorescent protein (CFP) and yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) as donor and acceptor fluorophores, respectively, attached to either end of the ER LBD, facilitating live cell imaging to monitor FRET changes post ligand delivery (Fig. 2A) (54). In addition, a fluorescence complementation biosensor was engineered by bisecting a single mVenus fluorescent protein and affixing it to both termini of the ER LBD (Fig. 2B). This arrangement enables a comparative examination of ER’s affinity for various agonists and antagonists (55). Concurrently, another FRET biosensor leveraging a YFP-CFP duo, alongside a Time-Resolved FRET (TR-FRET) assay, was devised to probe interactions between the ER LBD and the steroid receptor coactivator 1 (SRC1), hence appraising ligand binding in living cells (Fig. 2C, D) (56-58). Moreover, BRET-based ligand binding biosensors employing Aluc16 and mNeptune have been deployed to assess the activities of diverse steroid hormones (Fig. 2E) (59). Comprehensive mechanisms and illustrative schematics of these FRET- or BRET-based biosensors are depicted in Fig. 2. Consequently, FRET- and BRET-based explorations into ER binding furnish crucial insights into the binding efficiency and functionality of agonists and antagonists, along with the dynamics of ER-ligand interactions under physiological conditions, courtesy of their heightened sensitivity and the ability to conduct assays in living cells.

Fig. 2.

Schematic illustration of ER-ligand binding dynamics using biosensors and operational mechanisms. (A) Depicts a FRET-based biosensor designed to visualize ligand engagement through conformational transitions in the ER alpha (ERα) ligand-binding domain (LBD), resulting in fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) that detects these interactions (54). (B) Presents a fluorescence complementation-based biosensor that exposes conformational changes in the ERα LBD upon ligand engagement, enabling visualization through the activation of mVenus fluorescence (55). (C) Details a time-resolved FRET (TR-FRET)-based assay employing fluorescent dyes to verify the interaction between ERα LBD and coactivators following ligand engagement (57). (D) Describes a FRET-based biosensor that utilizes fluorescent proteins to confirm interactions between the ERα LBD and coactivators post-ligand binding (56). (E) Illustrates a BRET-based membrane-target biosensor that employs bioluminescence resonance energy transfer to authenticate conformational modifications in the ERα LBD triggered by ligand binding, with membrane localization enabled by a membrane localization sequence (MLS) (59). europium (Eu), streptavidin (SA), biotin (B), mNeptune (mNep), and membrane localization sequence (MLS) are denoted.

FLUORESCENT PROBE-BASED DETECTION OF ESTROGEN RECEPTOR DIMERIZATION

ER dimerization initiates upon ligand binding to the LBD of an ER, triggering a conformational change facilitating the union of the LBD domains. This involves ERα and ERβ, culminating in the formation of three ER dimer types: ERα homodimer, ERβ homodimer, and ERα-ERβ heterodimer, each imparting distinct influences on cellular functions (60). Specifically, in MCF-7 cells exposed to estrogen, the ERα homodimer encourages cell proliferation, in contrast, the ERβ homodimer suppresses proliferation by obstructing the G2/M phase of the cell cycle (61). Moreover, in a modified human osteosarcoma cell line (U2OS) stably expressing the ERα-ERβ heterodimer, a singular gene expression profile was discerned, deviating from those linked to conventional ER homodimers (62). Conversely, in both HeLa and MDA-MB231 cell lines, the ERα-ERβ heterodimer mimics the function of the ERα homodimer within genomic estrogen signaling pathways, underscoring variability in ER dimer-related signaling among different cell types (63). ER dimerization also contributes to non-genomic signaling. Although ERs predominantly dimerize, they also engage in protein-protein interactions with other hormone receptors and various proteins, thereby orchestrating a gamut of cellular signaling phenomena (64, 65). Hence, ER dimerization not only represents a pivotal juncture in canonical ER signaling but also independently modulates cell signaling, underscoring the necessity for subtype-specific investigations of ER dimerization. In preceding research, YFP was conjugated to the LBDs of ERα, ERβ, the androgen receptor (AR), and the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) within a yeast system. This alteration enabled the quantification of dimerization intensity elicited by diverse ligands, as reflected by increases in YFP intensity indicative of dimer formation. It was further observed that diminishing the peptide linker distance between the fluorescent protein (FPt) and the LBD augmented the sensor’s sensitivity towards LBD interactions (66).

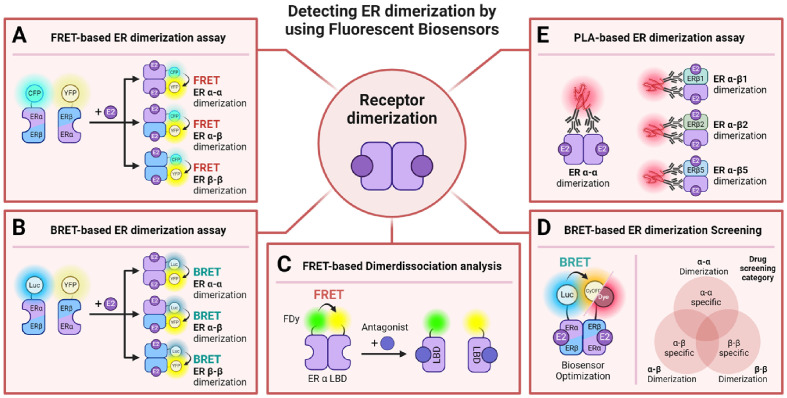

FRET and BRET stand as essential methodologies for the exploration of protein-protein interactions, having been utilized to investigate dimerization among ER LBDs. In a notable study, researchers employed fluorescein and tetramethylrhodamine, types of fluorescent dyes, to facilitate FRET phenomena, leveraging this for a biosensor targeting ERα-LBD dimers (Fig. 3C) (6). They monitored FRET variations consequent to ligand-driven dissolutions of ERα-LBD dimers or temperature shifts, thus delineating the kinetic and thermodynamic stabilities of these dimers. Subsequent experiments have harnessed CFP and YFP to forge FRET-based biosensors, adapting the wild-type ERα LBD and the ERα A430D LBD variant to amplify biosensor functionality (54). These adjustments paved the path for the establishment of high-throughput screening platforms. Additional inquiry using CFP and YFP revealed that both ERα and ERβ homo- and heterodimers could assemble independent of 17β-estradiol (E2) or antiestrogens in the human embryonic kidney 293 cell line. Mutations such as ERα L539A facilitated homodimerization and transcriptional activity in the absence of E2. Moreover, E2 was found to intensify interactions among ERα, ERβ, and the receptor interaction domains (RID) of steroid receptor coactivators (SRC)-1 and SRC-3 within human prostate stem and progenitor cells, elucidating the complex dynamics of ER interactions (Fig. 3A) (67).

Fig. 3.

Schematic illustration of ER dimerization using biosensors and operational mechanisms. (A) Exhibits a fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET)-based assay for visualizing both homodimerization and heterodimerization of ER subunits upon ligand engagement (67). (B) Depicts the use of bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) for illustrating homo- and heterodimerization of ER subunits (69). (C) Describes a FRET-based technique utilizing fluorescent dyes to track the dissociation of dimerized ERα LBD in the coinvolvement of ER antagonists (6). (D) Outlines a BRET-based biosensor tailored for drug screening endeavors: (Left) Optimization of the BRET biosensor for detecting ER homo- and heterodimerization. (Right) Application of the biosensor in categorizing drugs according to their potential to promote ER dimerization (70). (E) Introduces a proximity ligation assay (PLA)-based methodology for striking visualizations of ERα homodimerization and heterodimerization with ERβ isoforms (71). luciferase (Luc), fluorescent dyes (FDy), and the proximity ligation assay (PLA) are noted.

Numerous studies have implemented BRET, coupling luciferase as the donor with fluorescent proteins (FPt) as the acceptor (68). One specific study employed Renilla luciferase (RLuc) as the donor and YFP as the acceptor to investigate the ligand-selective activity of ERα-ERα, ERβ-ERβ homodimers, and ERα-ERβ heterodimers. Results suggested that ligand-bound ERα predominantly fosters the formation of ERα-ERβ heterodimers, with certain bioactive substances uniquely prompting ERβ/β homodimers and ERα/β heterodimers, demonstrating minimal effects on ERα/α homodimers (Fig. 3B) (69). Another investigation devised a biosensor exploiting the BRET phenomenon with the complete ER, enhanced by integrating nano luciferase (NLuc) as the donor and cyan-excitable orange-red fluorescent protein (CyOFP1) together with Halotag, a type of self-labeling protein (SLP), as acceptors (Fig. 3D). Utilizing this biosensor alongside stabilized cell lines facilitated the screening of 72 estrogen analogs (EAs), ascertaining alterations in ER dimerization and categorizing ER dimer subtype-specific EAs (70).

In studies utilizing antibodies for ER dimerization analysis, immunofluorescence (IF) and proximity ligation assay (PLA) techniques were employed to detect ERα and ERβ homo- and heterodimers in ERα-positive MCF-7 cells. This investigation corroborated dimerization between ERα and various ERβ variants (ERβ1, ERβ2, ERβ5), quantifying the ratios of homodimers and heterodimers relative to total ER proteins (Fig. 3E) (71). Detailed operational mechanisms and schematic illustrations of sensor constructs for these FRET- and BRET-based assays are summarized in Fig. 3.

FLUORESCENT PROBE-BASED DETECTION OF ER- AND ERES-MEDIATED TRANSCRIPTION AND GENE EXPRESSION DYNAMICS

The ER activates transcription by binding with high affinity to EREs, initiating gene expression in response to estrogen (7, 72). This ER-ERE interaction has been crucial for assessing the estrogenic impacts of both natural estrogens and various estrogenic chemicals. In the late 1990s, researchers utilized a range of assays to evaluate ER-mediated responses, including the Vitellogenin expression system, the E-SCREEN system, which assesses the proliferative effects of different substances comparatively, and the ER-CALUX assay, employing an ERE-Luciferase reporter for analysis. These in vitro ERE expression assay systems have been demonstrated to effectively quantify ER-mediated expression levels across different estrogen analogs (73). Additionally, for the enhanced detection of natural estrogens and estrogen-mimetic chemicals in mammalian and yeast cells alike, researchers developed a rapid and sensitive estrogen screening system utilizing a GFP expression system that capitalizes on ER-ERE interactions (74-76). These developments in ER-ERE binding-mediated screening systems have substantially streamlined the rapid detection and assessment of a wide variety of endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) and estrogenic compounds in the environment.

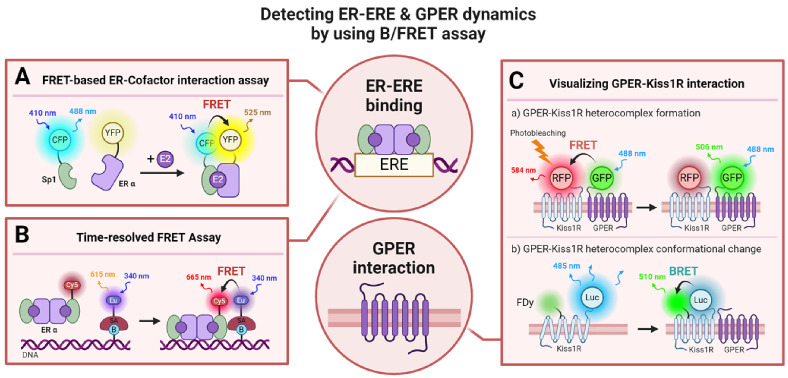

The exploration of ERE activity through fluorescence has not only improved screening capabilities but also enriched our comprehension of biological ER dynamics, particularly emphasizing the role of co-activators in ERE-ER interactions. By employing FRET, researchers visualized the interaction between ERα and Sp1 proteins through the creation of YFP-tagged ERα and CFP-tagged Sp1 (Fig. 4A). Their live cell imaging experiments demonstrated the hormone-dependent activity of the ER and Sp1 protein interaction in response to various ligands (77). Furthermore, additional studies utilized Time-Resolved FRET (TR-FRET), attaching Europium (Eu) as a donor to the ERE and Cy5 as an acceptor to the SRC3 coactivator, to measure the coactivator’s binding affinity to the ER (Fig. 4B). These investigations revealed that the coactivator’s recruitment is essential for forming the pre-initiation complex and initiating gene regulatory responses upon ligand binding (78). These FRET-based methodologies have enabled a closer examination of the molecular mechanisms governing ER-mediated gene regulation, potentially enhancing our understanding of cell signaling pathways implicated in ER-ERE-associated diseases. The principles of these FRET-based assays are summarized in schematic diagrams in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Schematic Illustration of Assays Utilizing B/FRET for Detecting ER-ERE and GPER Interactions. (A) Showcases a FRET-based biosensor elucidating the interaction between ERα and coactivators upon ligand binding through the use of fluorescent proteins (77). (B) Utilizes a fluorescent dye-based approach to confirm the attachment of ER and coactivator complexes to estrogen response elements (ERE) (78). (C) Employs B/FRET to depict the interactions of the G protein-coupled estrogen receptor (GPER) with other membrane proteins (91): (Top) Use of FRET and FRET acceptor photobleaching methods to validate the creation of GPER and Kiss1R heterocomplexes. (Bottom) Implementation of BRET to affirm that interaction with Kiss1R elicits a conformational alteration in Kiss1R. europium (Eu), streptavidin (SA), biotin (B), luciferase (Luc), and fluorescent dye (FDy) are mentioned.

Beyond fluorescence, luciferase assays have emerged as invaluable tools for monitoring ER-ERE-mediated gene expression, extending their application to in vivo studies. In a landmark study, researchers introduced the ERE-Luc biosensor, incorporating a luciferase reporter gene linked to an ERE (79). This arrangement allows the transcriptional activation of luciferase by the ligand-induced ER binding to the ERE, facilitating the observation of biological processes across various mammalian tissues and organs. Following the successful application of this luciferase reporter system for visualizing ER expression, a transgenic mouse model was developed, based on the ERE-Luc biosensor. This model enabled straightforward comparisons of ER expression across different tissues and provided clear evidence of decreased ER expression following treatment with ER antagonists (79). Leveraging this luminescence-based, in vivo system, researchers have thoroughly examined the kinetics of ER activity upon exposure to various agonists, antagonists, and phytoestrogens (80, 81). It has also facilitated research into the pharmacokinetic profiles of ER ligands, broadening our understanding of their biological impacts. Thus, both fluorescence and luminescence techniques have played crucial roles in visualizing ER-ERE-mediated gene expression and assessing ER activity in response to a spectrum of natural and synthetic ER ligands, significantly advancing our knowledge of ER signaling biology and pharmacology.

FLUORESCENT PROBE-BASED DETECTION OF G-PROTEIN-COUPLED ESTROGEN RECEPTOR (GPER) SIGNALING DYNAMICS

Upon the discovery of ERb, another transformative discovery emerged with the identification of the G protein-coupled receptor GPR30, subsequently renamed the G protein-coupled estrogen receptor (GPER) (82). GPER, which binds to estrogen, plays a pivotal role in cellular signaling, underscored by numerous studies that have confirmed its involvement in transcriptional regulation via pathways incorporating kinase proteins such as MAPK, PI3K, and ERK (8). This receptor’s association with a wide array of health conditions and diseases has spurred extensive research into its signaling mechanisms and functions, aiming to unearth its potential as both a therapeutic target and an early diagnostic marker for various diseases. This review also centers on synthesizing additional fluorescence-based studies that elucidate the estrogenic activity of GPER. GPER’s visualization was initially achieved through immunofluorescence in HEK293 cells in 2007, revealing its localization on the cell surface and functioning akin to that of other 7-transmembrane receptors. Subsequently, GPER’s functionality in various cellular environments has been investigated using fluorescence, including in hepatic stellate cells, retinal microglia, and cardiocytes (83, 84). Moreover, the exploration of GPER’s expression and activity across diverse tissues such as the breast, testes, and brain aims to adjudicate its connection to cancer and other diseases (85, 86). These inquiries strive to augment our comprehension of GPER’s cellular role and its implications for health and disease.

Fluorescence-based visualization methodologies have propelled GPER research forward by furnishing intricate insights into its biological roles and intracellular signaling pathways. Utilizing fluorescence, researchers have elucidated the endocytic trafficking mechanisms of GPER in cells, establishing its internalization dynamics and its engagement in Golgi and proteasome pathways (87). Furthermore, investigations into GPER’s colocalization with the actin cytoskeleton have been instrumental in examining its participation in the regulation of focal adhesion and stress fiber assembly, evidencing its vital role in mechanotransduction processes (88). These fluorescence-centered studies have illuminated GPER’s biological functions not just in normal cells but also in the context of cancer cells. Within cancer models, GPER activity has been shown to modulate processes such as epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), mechanotransduction, and cell contraction by inhibiting RhoA. Importantly, direct evidence from fluorescence imaging has elucidated GPER-mediated signaling pathways in cancer cells, underscoring their impact on the tumor microenvironment and drug resistance mechanisms (89, 90). Beyond the direct GPER signaling pathways, fluorescence-based techniques have facilitated the examination of its interactions with other proteins. For instance, to probe the interaction between the kisspeptin receptor (Kiss1R) and GPER, a Kiss1R-RFP and GPER-GFP fusion protein was engineered (Fig. 4C). Employing FRET and FRET acceptor photobleaching techniques, researchers assessed FRET efficiency and conformational changes in Kiss1R upon its interaction with GPER. Through the implementation of a BRET/FRET strategy, they have confirmed that the formation of Kiss1R/GPER heterocomplexes impairs Kiss1R-mediated signal transduction (91). A summarized schematic illustration of the B/FRET-based GPER-Kiss1R interaction assays is presented in Fig. 4. In essence, the deployment of fluorescent probes in the visualization of GPER has permitted expansive studies delving into its function and importance across various physiological and pathological frameworks, potentially charting a course towards therapeutic innovations in cancer and other diseases.

DISCUSSION

Over the last five decades, research into ER dynamics has seen remarkable progress, primarily driven by advancements in fluorescence-based methodologies, which have shed light on ER behaviors in a variety of biological settings. The advent of fluorescence technology has revolutionized our ability to directly observe the distribution of ER across cells and tissues, thus broadening our insights from in vitro to in vivo studies. It has been demonstrated, through the use of western blot analysis, that ERa relocates from the cytoplasm to the nucleus upon receiving estrogen signals (92). On the other hand, ERb has been identified in the cytosol, mitochondria, and nucleus through the application of immunofluorescence (IF) techniques (26), with transient transfection of fluorescent-tagged ER proteins mainly substantiating its nuclear presence (23, 28, 29). However, the predominant focus on nuclear localization has somewhat narrowed the scope of research into the cytosolic functions of ER. Attempts to bridge this gap have included strategies like modifying the nuclear localization signal (NLS) or utilizing solely the ER LBD (93, 94), yet these approaches fall short of fully capturing the wild-type ER activity, signaling the necessity for more sophisticated ER visualization techniques.

The nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of ER emerges as a pivotal mechanism for its function, facilitating the transition of ER between the cytoplasm and the nucleus to control gene expression (95). While this shuttling process is not unique to ER and is observable in other steroid receptors through fluorescent protein tagging (96, 97), dedicated research offering a direct visualization of ER shuttling is sparse. Notably, in 2014, the development of a novel GFP-tagged biosensor, amalgamating the glucocorticoid receptor (GR)-DBD with the ERa-LBD, marked a significant innovation. This biosensor can localize in the cytoplasm in the absence of estrogen and migrate to the nucleus upon its presence, paving the way for a high-content screening of synthetic ER ligands (98). This points to a compelling need for further exploration into the detailed mechanisms of ER’s nucleocytoplasmic movements, especially the roles played by proteins such as importin-a/b1 and transportin-2 (94).

Since the late 1990s, the ER-ERE complex has served as a multifaceted platform for screening estrogenic chemicals and endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs), relevant in both in vitro and in vivo contexts. Nevertheless, the capacity of ER-mediated gene expression to be elicited by non-estrogenic ligands, for example, growth factors, through ligand-independent pathways (10, 39), necessitates a broader investigation into these alternative gene expression routes.

In the same vein, the understanding of GPER has deepened through fluorescence studies, unveiling its critical roles in processes such as tumor cell survival and migration, influenced by the signaling pathways of estrogen, EGF, and IGF-1 (82, 99). A noteworthy breakthrough has been the development of a BRET-based BERKY system for the real-time analysis of GPCR activity in live cells. This innovation has facilitated dynamic investigations into GPER functionality and its interactions (100).

Despite comprehensive study, ERb has been explored to a lesser extent compared to ERa, underscoring a vital area for further inquiry through advanced fluorescence methodologies. This enhanced focus will likely enrich our comprehension of the distinct roles that ER subunits play in cellular signaling. The continuous evolution of fluorescence-based biosensors and assays not only supports these investigations but also opens new pathways for therapeutic interventions targeting ER-associated disorders. The pursuit of further research and technological advancements in fluorescence methodologies is indispensable for unraveling the intricate dynamics of ER and fostering the development of efficacious treatments for ER-related diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by grants from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) (No. 2022R1A4A5031503 and RS-2023-00279771). It was also funded by a grant (22194MFDS077) from the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety in 2022. All illustrations were created by us using BioRender (http://biorender.com).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicting interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fuentes N, Silveyra P. Estrogen receptor signaling mechanisms. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol. 2019;116:135–170. doi: 10.1016/bs.apcsb.2019.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arao Y, Korach KS. The physiological role of estrogen receptor functional domains. Essays Biochem. 2021;65:867–875. doi: 10.1042/EBC20200167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jia M, Dahlman-Wright K, Gustafsson JÅ. Estrogen receptor alpha and beta in health and disease. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;29:557–568. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2015.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen P, Li B, Ou-Yang L. Role of estrogen receptors in health and disease. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2022;13:839005. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.839005.820dffffc2fd49bc92a1fd70b67d6500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Filardo EJ, Thomas P. Minireview: G protein-coupled estrogen receptor-1, GPER-1: its mechanism of action and role in female reproductive cancer, renal and vascular physiology. Endocrinology. 2012;153:2953–2962. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tamrazi A, Carlson KE, Daniels JR, Hurth KM, Katzenellenbogen JA. Estrogen receptor dimerization: ligand binding regulates dimer affinity and dimer dissociation rate. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:2706–2719. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klinge CM. Estrogen receptor interaction with estrogen response elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:2905–2919. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.14.2905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeLeon C, Wang DQH, Arnatt CK. G protein-coupled estrogen receptor, GPER1, offers a novel target for the treatment of digestive diseases. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2020;11:578536. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2020.578536.bd6ce570efaf440686a6c8508172cc27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Björnström L, Sjöberg M. Mechanisms of estrogen receptor signaling: convergence of genomic and nongenomic actions on target genes. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:833–842. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bennesch MA, Picard D. Minireview: tipping the balance: ligand-independent activation of steroid receptors. Mol Endocrinol. 2015;29:349–363. doi: 10.1210/me.2014-1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shanle EK, Xu W. Endocrine disrupting chemicals targeting estrogen receptor signaling: identification and mechanisms of action. Chem Res Toxicol. 2011;24:6–19. doi: 10.1021/tx100231n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoon K, Kwack SJ, Kim HS, Lee BM. Estrogenic endocrine-disrupting chemicals: molecular mechanisms of actions on putative human diseases. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev. 2014;17:127–174. doi: 10.1080/10937404.2014.882194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campbell CG, Borglin SE, Green FB, Grayson A, Wozei E, Stringfellow WT. Biologically directed environmental monitoring, fate, and transport of estrogenic endocrine disrupting compounds in water: a review. Chemosphere. 2006;65:1265–1280. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rotroff DM, Dix DJ, Houck KA, et al. Using in vitro high throughput screening assays to identify potential endocrine-disrupting chemicals. Environ Health Perspect. 2013;121:7–14. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1205065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacoby-Morris K, Patterson GH. Choosing fluorescent probes and labeling systems. Methods Mol Biol. 2021;2304:37–64. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-1402-0_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fili N, Toseland CP. Fluorescence and labelling: how to choose and what to do. Exp Suppl. 2014;105:1–24. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-0856-9_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mocanu MM, Váradi T, Szöllősi J, Nagy P. Comparative analysis of fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) and proximity ligation assay (PLA) Proteomics. 2011;11:2063–2070. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201100028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gautier A, Juillerat A, Heinis C, et al. An engineered protein tag for multiprotein labeling in living cells. Chem Biol. 2008;15:128–136. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schneider AFL, Hackenberger CPR. Fluorescent labelling in living cells. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2017;48:61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2017.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoelzel CA, Zhang X. Visualizing and manipulating biological processes by using HaloTag and SNAP‐tag technologies. ChemBioChem. 2020;21:1935–1946. doi: 10.1002/cbic.202000037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Specht EA, Braselmann E, Palmer AE. A critical and comparative review of fluorescent tools for live-cell imaging. Annu Rev Physiol. 2017;79:93–117. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-022516-034055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu Y, Jiang T. Developments in FRET-and BRET-based biosensors. Micromachines. 2022;13:1789. doi: 10.3390/mi13101789.69df144927f649d3b0c482353d6d982c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Htun H, Holth LT, Walker D, Davie JR, Hager GL. Direct visualization of the human estrogen receptor α reveals a role for ligand in the nuclear distribution of the receptor. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:471–486. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.2.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu Z, Yang L, Ning W, et al. A high-affinity subtype-selective fluorescent probe for estrogen receptor β imaging in living cells. Chem Commun. 2018;54:3887–3890. doi: 10.1039/C8CC00483H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xie B, Meng Q, Yu H, et al. Estrogen receptor β-targeted hypoxia-responsive near-infrared fluorescence probes for prostate cancer study. Eur J Med Chem. 2022;238:114506. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2022.114506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang S-H, Liu R, Perez EJ, et al. Mitochondrial localization of estrogen receptor β. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4130–4135. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306948101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Casa AJ, Hochbaum D, Sreekumar S, Oesterreich S, Lee AV. The estrogen receptor alpha nuclear localization sequence is critical for fulvestrant-induced degradation of the receptor. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2015;415:76–86. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2015.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsuda K, Ochiai I, Nishi M, Kawata M. Colocalization and ligand-dependent discrete distribution of the estrogen receptor (ER) α and ERβ. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:2215–2230. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kocanova S, Mazaheri M, Caze-Subra S, Bystricky K. Ligands specify estrogen receptor alpha nuclear localization and degradation. BMC Cell Biol. 2010;11:1–13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-11-98.c50c91c27b6742f382c19e8d4750e7a9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hua H, Zhang H, Kong Q, Jiang Y. Mechanisms for estrogen receptor expression in human cancer. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2018;7:24. doi: 10.1186/s40164-018-0116-7.8c7e28e0a0b84f949d141cdf5ed90e68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tang C, Du Y, Liang Q, Cheng Z, Tian J. A novel estrogen receptor α-targeted near-infrared fluorescent probe for in vivo detection of breast tumor. Mol Pharm. 2018;15:4702–4709. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.8b00684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.He P, Deng X, Xu B, et al. Development of highly efficient estrogen receptor β-targeted near-infrared fluorescence probes triggered by endogenous hydrogen peroxide for diagnostic imaging of prostate cancer. Molecules. 2023;28:2309. doi: 10.3390/molecules28052309.bcc5a51de1bd48ecb4d9fabc705714eb [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang G, Dong M, Yao X, et al. Advancing breast cancer diagnosis with a near-infrared fluorescence imaging smart sensor for estrogen/progesterone receptor detection. Sci Rep. 2023;13:21086. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-48556-w.caa112e6a7d245e7a18d75bc7eff7404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Métivier R, Stark A, Flouriot G, et al. A dynamic structural model for estrogen receptor-α activation by ligands, emphasizing the role of interactions between distant A and E domains. Mol Cell. 2002;10:1019–1032. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00746-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rajbhandari P, Finn G, Solodin NM, et al. Regulation of estrogen receptor α N-terminus conformation and function by peptidyl prolyl isomerase Pin1. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32:445–457. doi: 10.1128/MCB.06073-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cagnet S, Ataca D, Sflomos G, et al. Oestrogen receptor α AF-1 and AF-2 domains have cell population-specific functions in the mammary epithelium. Nat Commun. 2018;9:4723. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07175-0.648ebe25ccab4e248c751792d692bd28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Björnström L, Sjöberg M. Estrogen receptor-dependent activation of AP-1 via non-genomic signalling. Nucl Recept. 2004;2:3. doi: 10.1186/1478-1336-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Azuma K, Horie K, Inoue S, Ouchi Y, Sakai R. Analysis of estrogen receptor α signaling complex at the plasma membrane. FEBS Lett. 2004;577:339–344. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berno V, Amazit L, Hinojos C, et al. Activation of estrogen receptor-α by E2 or EGF induces temporally distinct patterns of large-scale chromatin modification and mRNA transcription. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2286. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002286.997d919e62424f01a5f7e0fb53bc4278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zwart W, de Leeuw R, Rondaij M, Neefjes J, Mancini MA, Michalides R. The hinge region of the human estrogen receptor determines functional synergy between AF-1 and AF-2 in the quantitative response to estradiol and tamoxifen. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:1253–1261. doi: 10.1242/jcs.061135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vallet A, El Ezzy M, Diennet M, Haidar S, Bouvier M, Mader S. The AF-2 cofactor binding region is key for the selective SUMOylation of estrogen receptor alpha by antiestrogens. J Biol Chem. 2023;299:102757. doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2022.102757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weinberg AL, Carter D, Ahonen M, Alarid ET, Murdoch FE, Fritsch MK. The DNA binding domain of estrogen receptor α is required for high-affinity nuclear interaction induced by estradiol. Biochemistry. 2007;46:8933–8942. doi: 10.1021/bi700018w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Burns KA, Li Y, Arao Y, Petrovich RM, Korach KS. Selective mutations in estrogen receptor α D-domain alters nuclear translocation and non-estrogen response element gene regulatory mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:12640–12649. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.187773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Murata M, Nakayama M, Irie H, et al. Novel biosensor for the rapid measurement of estrogen based on a ligand-receptor interaction. Anal Sci. 2001;17:387–390. doi: 10.2116/analsci.17.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.La Spina R, Ferrero VEV, Aiello V, et al. Label-free biosensor detection of endocrine disrupting compounds using engineered estrogen receptors. Biosensors. 2017;8:1. doi: 10.3390/bios8010001.1c95298f356c4e7d80c9e157496374a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim SH, Tamrazi A, Carlson KE, Daniels JR, Lee IY, Katzenellenbogen JA. Estrogen receptor microarrays: subtype-selective ligand binding. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:4754–4755. doi: 10.1021/ja039586q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang L, Meng Q, Hu Z, et al. Estrogen receptor sensing in living cells by a high affinity turn-on fluorescent probe. Sensors Actuators B: Chem. 2018;272:589–597. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2018.06.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Díaz M, Hernández D, Valdés-Baizabal C, et al. Fluorescent tamoxifen derivatives as biophotonic probes for the study of human breast cancer and estrogen-receptor directed photosensitizers. Opt Mater. 2023;138:113736. doi: 10.1016/j.optmat.2023.113736. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ohno K, Fukushima T, Santa T, et al. Estrogen receptor binding assay method for endocrine disruptors using fluorescence polarization. Anal Chem. 2002;74:4391–4396. doi: 10.1021/ac020088u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tirri ME, Huttunen RJ, Toivonen J, Härkönen PL, Soini JT, Hänninen PE. Two-photon excitation in fluorescence polarization receptor-ligand binding assay. SLAS Discov. 2005;10:314–319. doi: 10.1177/1087057104273334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Beekman JM, Allan GF, Tsai SY, Tsai MJ, O'Malley BW. Transcriptional activation by the estrogen receptor requires a conformational change in the ligand binding domain. Mol Endocrinol. 1993;7:1266–1274. doi: 10.1210/mend.7.10.8264659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gee AC, Katzenellenbogen JA. Probing conformational changes in the estrogen receptor: evidence for a partially unfolded intermediate facilitating ligand binding and release. Mol Endocrinol. 2001;15:421–428. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.3.0602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ho BK, Agard DA. Probing the flexibility of large conformational changes in protein structures through local perturbations. PLoS Comp Biol. 2009;5:e1000343. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000343.55c2663a932d4ab0ba3fc7c9f816d048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.De S, Macara IG, Lannigan DA. Novel biosensors for the detection of estrogen receptor ligands. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;96:235–244. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2005.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McLachlan MJ, Katzenellenbogen JA, Zhao H. A new fluorescence complementation biosensor for detection of estrogenic compounds. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2011;108:2794–2803. doi: 10.1002/bit.23254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Awais M, Sato M, Sasaki K, Umezawa Y. A genetically encoded fluorescent indicator capable of discriminating estrogen agonists from antagonists in living cells. Anal Chem. 2004;76:2181–2186. doi: 10.1021/ac030410g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gunther JR, Du Y, Rhoden E, et al. A set of time-resolved fluorescence resonance energy transfer assays for the discovery of inhibitors of estrogen receptor-coactivator binding. J Biomol Screen. 2009;14:181–193. doi: 10.1177/1087057108329349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Moore TW, Gunther JR, Katzenellenbogen JA. Estrogen receptor alpha/co-activator interaction assay: TR-FRET. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1278:545–553. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2425-7_36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kim SB, Paulmurugan R, Kitada N, Maki SA. Single-chain multicolor-reporter templates for subcellular localization of molecular events in mammalian cells. RSC Chem Biol. 2023;4:1043–1049. doi: 10.1039/D3CB00077J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kumar R, Zakharov MN, Khan SH, et al. The dynamic structure of the estrogen receptor. J Amino Acids. 2011;2011:812540. doi: 10.4061/2011/812540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Song D, He H, Indukuri R, et al. ERα and ERβ homodimers in the same cellular context regulate distinct transcriptomes and functions. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2022;13:930227. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.930227.738a38fd4263449b9f8981899e871eb4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Monroe DG, Secreto FJ, Subramaniam M, Getz BJ, Khosla S, Spelsberg TC. Estrogen receptor α and β heterodimers exert unique effects on estrogen-and tamoxifen-dependent gene expression in human U2OS osteosarcoma cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:1555–1568. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li X, Huang J, Yi P, Bambara RA, Hilf R, Muyan M. Single-chain estrogen receptors (ERs) reveal that the ERα/β heterodimer emulates functions of the ERα dimer in genomic estrogen signaling pathways. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:7681–7694. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.17.7681-7694.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Iwabuchi E, Miki Y, Suzuki T, Sasano H. Visualization of the protein-protein interactions of hormone receptors in hormone-dependent cancer research. Endocr Oncol. 2022;2:R132–R142. doi: 10.1530/EO-22-0059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Majumdar S, Rinaldi JC, Malhotra NR, et al. Differential actions of estrogen receptor α and β via nongenomic signaling in human prostate stem and progenitor cells. Endocrinology. 2019;160:2692–2708. doi: 10.1210/en.2019-00177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Muddana SS, Peterson BR. Fluorescent cellular sensors of steroid receptor ligands. Chembiochem. 2003;4:848–855. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200300606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bai Y, Giguère V. Isoform-selective interactions between estrogen receptors and steroid receptor coactivators promoted by estradiol and ErbB-2 signaling in living cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:589–599. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kim HM, Seo H, Park Y, Lee HS, Lee SH, Ko KS. Development of a human estrogen receptor dimerization assay for the estrogenic endocrine-disrupting chemicals using bioluminescence resonance energy transfer. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:8875. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18168875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Powell E, Xu W. Intermolecular interactions identify ligand-selective activity of estrogen receptor α/β dimers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:19012–19017. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807274105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Choi G, Kang H, Suh JS, et al. Novel estrogen receptor dimerization BRET-based biosensors for screening estrogenic endocrine-disrupting chemicals. Biomater Res. 2024;28:0010. doi: 10.34133/bmr.0010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Iwabuchi E, Miki Y, Ono K, Onodera Y, Sasano H. In situ evaluation of estrogen receptor dimers in breast carcinoma cells: visualization of protein-protein interactions. Acta Histochem Cytochem. 2017;50:85–93. doi: 10.1267/ahc.17011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bafna D, Ban F, Rennie PS, Singh K, Cherkasov A. Computer-aided ligand discovery for estrogen receptor alpha. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:4193. doi: 10.3390/ijms21124193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Duijndam B, Tedeschi M, Stel W, et al. Evaluation of an imaging-based in vitro screening platform for estrogenic activity with OECD reference chemicals. Toxicol In Vitro. 2022;81:105348. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2022.105348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Miller S, Kennedy D, Thomson J, et al. A rapid and sensitive reporter gene that uses green fluorescent protein expression to detect chemicals with estrogenic activity. Toxicol Sci. 2000;55:69–77. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/55.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Beck V, Pfitscher A, Jungbauer A. GFP-reporter for a high throughput assay to monitor estrogenic compounds. J Biochem Biophys Methods. 2005;64:19–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jbbm.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fujiki N, Konno H, Kaneko Y, et al. Estrogen response element-GFP (ERE-GFP) introduced MCF-7 cells demonstrated the coexistence of multiple estrogen-deprivation resistant mechanisms. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;139:61–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2013.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kim K, Barhoumi R, Burghardt R, Safe S. Analysis of estrogen receptor α-Sp1 interactions in breast cancer cells by fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:843–854. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Likhite VS, Stossi F, Kim K, Katzenellenbogen BS, Katzenellenbogen JA. Kinase-specific phosphorylation of the estrogen receptor changes receptor interactions with ligand, deoxyribonucleic acid, and coregulators associated with alterations in estrogen and tamoxifen activity. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:3120–3132. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ciana P, Di Luccio G, Belcredito S, et al. Engineering of a mouse for the in vivo profiling of estrogen receptor activity. Mol Endocrinol. 2001;15:1104–1113. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.7.0658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ciana P, Raviscioni M, Mussi P, et al. In vivo imaging of transcriptionally active estrogen receptors. Nat Med. 2003;9:82–86. doi: 10.1038/nm809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Maggi A, Villa A. In vivo dynamics of estrogen receptor activity: the ERE-Luc model. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;139:262–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Prossnitz ER, Barton M. The G protein-coupled oestrogen receptor GPER in health and disease: an update. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2023;19:407–424. doi: 10.1038/s41574-023-00822-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cortes E, Lachowski D, Rice A, et al. Tamoxifen mechanically deactivates hepatic stellate cells via the G protein-coupled estrogen receptor. Oncogene. 2019;38:2910–2922. doi: 10.1038/s41388-018-0631-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Li R, Wang Y, Chen P, Meng J, Zhang H. G-protein coupled estrogen receptor activation protects the viability of hyperoxia-treated primary murine retinal microglia by reducing ER stress. Aging (Albany NY) 2020;12:17367. doi: 10.18632/aging.103733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chevalier N, Vega A, Bouskine A, et al. GPR30, the non-classical membrane G protein related estrogen receptor, is overexpressed in human seminoma and promotes seminoma cell proliferation. PloS One. 2012;7:e34672. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034672.91817073c4da41db863ebc8460d75625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bai N, Zhang Q, Zhang W, et al. G-protein-coupled estrogen receptor activation upregulates interleukin-1 receptor antagonist in the hippocampus after global cerebral ischemia: implications for neuronal self-defense. J Neuroinflammation. 2020;17:1–18. doi: 10.1186/s12974-020-1715-x.b4c27fc13b214f0b860736b04790e831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cheng SB, Quinn JA, Graeber CT, Filardo EJ. Down-modulation of the G-protein-coupled estrogen receptor, GPER, from the cell surface occurs via a trans-Golgi-proteasome pathway. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:22441–22455. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.224071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lachowski D, Cortes E, Matellan C, et al. G protein-coupled estrogen receptor regulates actin cytoskeleton dynamics to impair cell polarization. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:592628. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.592628.8153b8e6157e4fde885521f46a3fcb2a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rice A, Cortes E, Lachowski D, et al. GPER activation inhibits cancer cell mechanotransduction and basement membrane invasion via RhoA. Cancers. 2020;12:289. doi: 10.3390/cancers12020289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yu T, Yang G, Hou Y, et al. Cytoplasmic GPER translocation in cancer-associated fibroblasts mediates cAMP/PKA/CREB/glycolytic axis to confer tumor cells with multidrug resistance. Oncogene. 2017;36:2131–2145. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ke R, Lok SIS, Singh K, Chow BKC, Janovjak H, Lee LTO. Formation of Kiss1R/GPER heterocomplexes negatively regulates Kiss1R-mediated signalling through limiting receptor cell surface expression. J Mol Biol. 2021;433:166843. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2021.166843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hewitt SC, Collins J, Grissom S, Hamilton K, Korach KS. Estren behaves as a weak estrogen rather than a nongenomic selective activator in the mouse uterus. Endocrinology. 2006;147:2203–2214. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Strillacci A, Sansone P, Rajasekhar VK, et al. ERα-LBD, an isoform of estrogen receptor alpha, promotes breast cancer proliferation and endocrine resistance. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2022;8:96. doi: 10.1038/s41523-022-00470-6.f78ea24d939745a8868b8fcd4d4bff37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Moriyama T, Yoneda Y, Oka M, Yamada M. Transportin-2 plays a critical role in nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of oestrogen receptor-α. Sci Rep. 2020;10:18640. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-75631-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Rochefort H, André J, Baskevitch PP, Kallos J, Vignon F, Westley B. Nuclear translocation and interactions of the estrogen receptor in uterus and mammary tumors. J Steroid Biochem. 1980;12:135–142. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(80)90263-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Defranco DB, Madan AP, Tang Y, Chandran UR, Xiao N, Yang J. Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of steroid receptors. Vitam Horm. 1995;51:315–338. doi: 10.1016/S0083-6729(08)61043-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mazaira GI, Echeverria PC, Galigniana MD. Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of the glucocorticoid receptor is influenced by tetratricopeptide repeat-containing proteins. J Cell Sci. 2020;133:jcs238873. doi: 10.1242/jcs.238873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Dull AB, George AA, Goncharova EI, et al. Identification of compounds by high-content screening that induce cytoplasmic to nuclear localization of a fluorescent estrogen receptor α chimera and exhibit agonist or antagonist activity In Vitro. SLAS Discov. 2014;19:242–252. doi: 10.1177/1087057113504136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.De Marco P, Bartella V, Vivacqua A, et al. Insulin-like growth factor-I regulates GPER expression and function in cancer cells. Oncogene. 2013;32:678–688. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Maziarz M, Park J-C, Leyme A, et al. Revealing the activity of trimeric G-proteins in live cells with a versatile biosensor design. Cell. 2020;182:770–785. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]