Abstract

Organic by‐products are released into the surrounding soil during the terrestrial decomposition of animal remains. The affected area, known as the Cadaver Decomposition Island (CDI), can undergo biochemical changes that contribute to landscape heterogeneity. Soil bacteria are highly sensitive to labile inputs, but it is unknown how they respond to shifts in dissolved organic matter (DOM) quantity and quality resulting from animal decomposition. We aimed to evaluate the relationship between soil DOM composition and bacterial activity/function in CDIs under a Canadian temperate continental climate. This was studied in soils surrounding adult pig carcasses (n = 3) that were surface deposited within a mixed forested environment (Trois‐Rivières, Québec) in June 2019. Using fluorescence spectroscopy and dissolved organic carbon analyses, we detected a pulse of labile protein‐like DOM during the summer season (day 55). This was found to be an important driver of heightened soil bacterial respiration, cell abundance and potential carbohydrate metabolism. These bacterial disturbances persisted into the cooler autumn season (day 156) and led to the gradual transformation of labile DOM inputs into microbially sourced humic‐like compounds. By the spring (day 324), DOM quantities and bacterial measures almost recovered, but DOM quality remained distinct from surrounding vegetal humic signals. All observed effects were spatially constrained to the topsoil (A‐horizon) and within 20 cm laterally from the carcasses. These findings provide valuable insight into CDI organic matter cycling within a cold‐climate ecosystem. Repeated CDI studies will however be required to capture the changing dynamics resulting from increasing global temperatures.

Keywords: cadaver decomposition island, dissolved organic matter, soil biogeochemistry, soil microbial ecology, bacterial metabolism, carrion

Key Points

Pig decomposition created prolonged and spatially constrained changes in soil DOM composition, as detected by fluorescence spectroscopy

Labile DOM inputs from carcasses drove shifts in soil bacterial respiration, abundance, and metabolic function

Microbial transformation of labile carcass inputs into humic‐like compounds gradually occurred, even over cooler seasons

1. Introduction

As an animal decomposes, a large quantity of fluid and organic compounds are leached into the surrounding soil following the autolytic, microbial, and larval breakdown of flesh. The biological by‐products produced reflect the high protein, lipid and water content found in animal soft tissues, which differs from the composition of vegetation that is ubiquitously found in terrestrial environments (Achinewhu et al., 1995; de Lange et al., 2003; Ioan et al., 2017). As a result, the decomposition of an animal body leads to the formation of a biochemically distinct “hot spot” known as the cadaver decomposition island (CDI) (Carter et al., 2007). Affected soil experiences characteristic physiochemical changes (e.g., pH, moisture, redox potential, nutrient concentrations) that are often accompanied by shifts in microbial community composition, function, and activity (Aitkenhead‐Peterson et al., 2012; Fancher et al., 2017; Finley et al., 2016; Pechal et al., 2013; Singh et al., 2018). CDIs are therefore considered a localized natural disturbance that contribute to soil heterogeneity (Carter et al., 2007). CDI properties are highly dynamic and can differ between decomposition phases, individuals, season, and soil type (Aitkenhead‐Peterson et al., 2012; Breton et al., 2016; Stokes et al., 2009; Vass et al., 1992; Wilson et al., 2007). Semi‐controlled CDI studies on animal or donated human remains have largely been directed toward forensic applications in post‐mortem interval estimation and clandestine grave detection (Fiedler et al., 2023; Wescott, 2018). Such studies have also been principally conducted during the summer or in annually warm areas (e.g., Texas, Tennessee) because of the unverified assumption that microbially mediated decomposition ceases at below‐freezing temperatures (Mason et al., 2023; Megyesi et al., 2005; Singh et al., 2023). In consequence, there is minimal empirical research that examines body decomposition within an ecological context, particularly in temperate regions (Barton, Cunningham, Lindenmayer, & Manning, 2013; Meyer et al., 2013). The ecological processes and seasonal effects that govern CDI biochemistry are hence largely unknown.

Carrion is a concentrated labile resource because of an animal's narrow C:N ratio, large mass and patchy distribution (Barton, Cunningham, Macdonald, et al., 2013; Carter et al., 2007). The drastic changes in soil conditions and nutrient availability accompanying animal decomposition tend to favor bacterial processes by promoting the proliferation of zymogenous and copiotroph bacterial groups (Carter et al., 2017; Forbes & Dadour, 2009). Levels of carcass‐derived C and N are also more suited to supporting the stoichiometry of prokaryotes over fungi (Strickland & Rousk, 2010; Strickland & Wickings, 2015). Incubation studies have additionally demonstrated that soil bacterial communities are highly responsive to the addition of labile organic matter, and that they can subsequently affect its breakdown (Cleveland et al., 2007; de Graaff et al., 2010; Goldfarb et al., 2011; Lerch et al., 2011; Wardle et al., 2004). The functional response of dominant bacteria in CDIs can therefore be crucial in controlling the degradation and trophic transfer of labile carcass inputs. This can ultimately influence downstream consumers and overall soil productivity (Fiedler et al., 2023). However, the dynamics between soil bacteria and organic matter have been minimally evaluated under the unique scenario of animal decomposition. This has left a gap in the mechanistic understanding of how and when carrion‐derived organic matter is cycled in terrestrial ecosystems. Such information is needed to better establish the role of dead animal biomass in ecosystem food‐webs and nutrient/energy budgets (Barton, 2015; Barton et al., 2019).

Dissolved organic matter (DOM) is the soluble and most bioavailable fraction of organic matter in soils. The degree of DOM's influence on soil bacteria and its cycling is partly dictated by its chemical composition, which is characterized by its quantity and quality (Chapin et al., 2002; Chenu et al., 2014). Soil DOM quantity is commonly evaluated by using organic carbon concentrations as a proxy, given that DOM can be composed of up to 50% of carbon in mass (Strawn et al., 2015). DOM quantity provides insight into the flux of organic material, but the measure fails to inform about lability, transformation, and cycling. This can be addressed through the characterization of DOM quality. Small, simple compounds generated from biological activity (e.g., amino acids from metabolites) are deemed high‐quality, for they can be readily transformed by microbial enzymes. Large, conjugated, and aromatic compounds originating from plant matter (e.g., lignin, tannin) or polymerization (i.e., humic substances) are contrarily low‐quality and recalcitrant because of the greater degree of microbial specialization needed for their metabolism (Chapin et al., 2002; Marín‐Spiotta et al., 2014; Strawn et al., 2015). DOM quality can be inferred using cost‐effective spectrofluorometric techniques and statistical modelling. This is possible because of an optically active fraction of DOM compounds that can produce three‐dimensional excitation‐emission (EEM) spectra based on their molecular structure (Fellman et al., 2010; Hansen et al., 2016; Stedmon et al., 2003). Significant shifts in DOM composition can result from the introduction of new sources, microbial processes and humification. Hence, fluorescence spectroscopy has been used in combination with quantitative analyses to track DOM inputs and their transformation in various natural and engineered systems (D’Andrilli et al., 2019; Ishii & Boyer, 2012). Characterising DOM composition in CDI soils can similarly provide insight on carrion's value to microbial communities and its contribution to labile and recalcitrant pools.

The following study aimed to evaluate the spatiotemporal relationship between soil DOM composition and bacterial responses to CDI formation under a Canadian temperate continental climate. It was hypothesized that the decomposition of animal remains would introduce a large quantity of DOM and shift chemical characteristics from vegetal‐dominated humic substances to labile microbially sourced protein‐like compounds. This was moreover expected to fuel increases in bacterial activity and promote functional changes that support the degradation of high‐quality substrates. Changes were anticipated to be greatest following the complete purging of fluids and were assumed to decrease over time from the gradual transformation and depletion of labile carcass‐derived material. This was tested over three seasons (summer, autumn, spring) by examining the EEM spectra, DOC concentration and different aspects of bacterial metabolism in soils surrounding pig carcasses placed in a forested site of Trois‐Rivières, Quebec. Labile carcass DOM was initially found to stimulate bacterial metabolic responses in nearby soil. This was followed, during the cooler seasons, by the gradual microbial humification of DOM and eventual restoration of soil bacterial function.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site and Set‐Up

The carcasses of three domestic adult pigs (Sus scrofa domesticus Erxleben), weighing approximately 90 kg each, were obtained the morning of 18 June 2019, from the Boucherie Côté at Sainte‐Eulalie (Quebec, Canada). The pigs were killed with a perforating gun in accordance with Section 12 of the Quebec Animal Welfare and Safety Act, and the use of pigs was authorized under Section 11.1 of the Quebec Food Products Act. Each carcass was placed in a plastic body bag and transported to a 100 m2 experimental site located on the campus of the Université du Québec à Trois‐Rivières (46.3446°N, −72.5834°W). The carcasses were surface deposited directly on the soil with a minimum of 10 m between each carcass. When not sampling or conducting observations, galvanized mesh cages were placed over the carcasses to prevent scavenging and the dispersion of remains by large animals.

The experimental site was situated in a temperate mixed forest within the Saint‐Laurent lowlands ecoregion (Jobin et al., 2010). The area was populated by white pine (Pinus strobus), red maple (Acer rubrum), white spruce (Picea glauca) and American beech (Fagus grandifolia). The forest foliage created a closed canopy with an open understory, which provided a mix of sunny and shaded areas throughout the day (Maisonhaute & Forbes, 2020). The terrain had a minor slope (0%–3%) and consisted of an imperfectly drained humo‐ferric podzolic soil with a sandy texture. The soil profile in the area on average had an A‐horizon depth of 0–14 cm and B‐horizon depth of 14–50 cm (Soil Landscapes of Canada Working Group, 2010). The climate of the region is classified as snowy, fully humid with warm summers (Dfb) according to the Köppen‐Geiger classification system (Peel et al., 2007).

2.2. Sampling

Soil samples were collected laterally from the carcass at increasing distances uphill (−20, −50 cm) and downhill (20, 50, 100, 200 cm) using a manual slide hammer soil corer (7.62 × 15.24 cm). 0 cm samples were taken as close as possible to the trunk or abdomen of the carcass. An uphill and downhill control sample was also obtained from outside the perimeter of the experimental site (Figure S1 in Supporting Information S1). Soil cores were wrapped in aluminum foil and transported by cooler to be stored at 4°C before treatment. Sampling for the summer, autumn and spring seasons were respectively conducted on day 55, 156 and 324. During this period, the carcasses remained in a differential decomposition state of advanced decay and dry remains. Carcass skin was dry and leathery in appearance with partial bone exposure and accompanied by the presence of adipose tissue and lipid residues that were colonized by cheese skipper larvae (Piophilidae) (Maisonhaute & Forbes, 2020). No winter samples were collected because of deep snow cover and ground frost.

2.3. Soil and Slurry Preparation

Soil cores were processed by discarding the organic layer and carefully dividing the soil of the A‐horizon (topsoil) and B‐horizon (subsoil) into separate aluminum dishes. The soil was placed under a fume hood to airdry at ∼20°C for 1 week. Once dried, the soil was sieved (2 mm) to remove debris and break apart aggregates. The dried and sieved soil was then stored in sealed plastic bags at 4°C until slurry preparation.

A 1g sample of dried‐sieved soil was mixed with 40 mL ultrapure water and shaken overnight at 4°C. Soil particles were allowed to settle for a minimum of 30 min, to which the supernatant was extracted and buffered to 0.001 N NaHCO3 to replicate the ionic strength of natural soil systems (Wickland et al., 2007). The buffered slurry was then passed through pre‐combusted (500°C, 4 hr) GF/F (0.7 μm) or GF/D (2.7 μm) glass microfiber filters, respectively, for chemical and bacterial analyses. A subset of air‐dried soil was further dried at 105°C for 24 hr in order to determine the residual moisture content to correct absolute values into units of dried‐weight soil.

2.4. Chemical Analyses

For DOM quantity, the concentration of dissolved organic carbon (DOC) in acidified (HCl, pH < 2) GF/F slurries was measured using a Sievers M9 Portable TOC Analyzer (GE Analytical Instruments, Boulder, CO). The instrument was verified against a five‐point potassium hydrogen phthalate calibration curve and samples were run in triplicates with an accepted relative standard deviation of ≤10%.

DOM chemical characteristics were evaluated based on the absorbance and fluorescence EEM spectra of GF/F slurries. Fluorescent EEMs were created using a 1 cm glass cuvette and a Carey Eclipse Fluorescence Spectrometer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA). EEMs were collected at excitation wavelengths (Ex) of 230–540 nm and emission wavelengths (Em) of 300–600 nm respectively at 5 and 2 nm intervals. Instrument biases were removed using manufacturer‐provided correction files. Fluorescent spectra were corrected for inner filter effects by using the absorbance spectra (200–800 nm) of samples analyzed in a 1 cm quartz cuvette and a Carey 100 UV‐Vis Spectrophotometer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA). EEMs were normalized to Raman units (R.U., nm−1) using the area under the curve of the Raman scatter peak of ultrapure water. Fluorescent and absorbance based spectral indices were obtained using the ratios and calculations described in Fellman et al. (2010). The freshness index (BIX) served as an indicator of recently produced microbial DOM versus highly decomposed senescent DOM (Huguet et al., 2009). The humification index (HIX) designated the degree of DOM humification, which is associated with structural complexity (Ohno, 2002; Zsolnay et al., 1999). Microbial and terrestrial DOM sources were identified using the fluorescent index (FI) (Cory & McKnight, 2005). Lastly, DOM molecular weight was represented by the spectral slope ratio (S R) using the absorbance slope of 275–295 nm/350–400 nm (Helms et al., 2008). A total of 133 EEMs were collected in this study and analyzed using Parallel factor analysis (PARAFAC) as described by Murphy et al. (2013). PARAFAC is a multivariate modeling technique that decomposes 3D EEMs into independent fluorescent signals that are indicative of DOM chemical composition and source. The analysis was run using the drEEM toolbox 0.6.3 for MATLAB 2021b (Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA).

A four component (C1‐C4) PARAFAC model with 99% explained variation was validated using split‐half analysis (Figure S2 in Supporting Information S1). The model was uploaded to the OpenFluor online database (Murphy et al., 2019) for component identification. A search with a similarity score of 92% yielded matches for all four components. C1 (Exmax < 250, Emmax 458 nm) matched with components associated with humic‐like substances of terrestrial origin (Murphy et al., 2011). C2 (Exmax < 250, Emmax 414 nm) matched as a lower molecular weight humic‐ and/or fulvic‐like component that is linked to autochthonous microbial activity (Garcia et al., 2018; Murphy et al., 2011). C3 (Exmax 280, Emmax 336 nm) corresponded to protein‐like compounds that resemble free or bound tyrosine and tryptophan resulting from recent microbial peptide degradation (Fellman et al., 2010; Lapierre & del Giorgio, 2014; Wheeler et al., 2017). Matches for C4 (Exmax < 240, Emmax 312/364 nm) reported confounding identifications. The component was described as humic‐like (Dainard et al., 2019), protein‐like (Bittar et al., 2016; Dainard et al., 2019; Lapierre & del Giorgio, 2014; Wheeler et al., 2017), quinone‐like (Cory & McKnight, 2005) or inconclusive (Jørgensen et al., 2011; Murphy et al., 2018). This disagreement may be because of an overlap between the fluorescent signal of humic phenols (e.g., tannins) and the phenolic hydroxyl of labile tyrosine (Maie et al., 2007). The production of quinones from the oxidation of phenol‐containing lignin likely further obscured signal identification (Hernes et al., 2009). The overlap between compounds would explain for the double emission maxima reported by the model. For simplicity, C4 was decided to be identified as a phenol‐like component of terrestrial and/or microbial origin. Component values were calculated and analyzed as the precent contribution (%C1–%C4) to the maximum fluorescent intensity (Fmax, R.U.).

2.5. Bacterial Analyses

Rates of bacterial respiration (BR) of GF/D slurries were measured in the dark at 20°C using 4 mL glass vials equipped with PSt5 optical oxygen sensors and a SDR SensorDish™ (PreSens, Regensburg, Germany). Readings were automatically taken every 60 min for a maximum of 2 weeks or until respiration rates plateaued. The rate of oxygen consumption was obtained from the slope of the linear regression line of O2 (mg·L−1) versus time. The rate of O2 respiration was converted to the rate of carbon consumption using a respiratory quotient of 0.95 (Hilman et al., 2022).

For bacterial cell abundance (BA), 1.5 mL of GF/D slurries were fixed to a final concentration of 0.5% glutaraldehyde and stored at −80°C until analysis. Thawed bacterial cells were stained with 50X SYBR™ Green (Invitrogen, Walham, MA) and incubated at room temperature in the dark for 15 min. Cells were counted on a BD Accuri™ C6 Flow Cytometer (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) with an acquisition threshold of 10,000 events. Samples additionally filtered through GF/HP (0.22 μm) were stained and ran as blanks for a limit of 1 min. TruCount™ (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) fluorescent beads (24.3 beads·μL‐1) were used to determine the true flow rate. Data processing was done on BD CSampler™ Plus software (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Absolute cell counts were obtained from the log‐scale of FL1 (green, 533 nm) versus FL3 (red, >670 nm) density plots, and electronic gates were determined based on the strategy described by Hammes and Egli (2010).

Biolog EcoPlates™ (BioLog Inc., Hayward, CA) were used as an in vitro technique to assess the functional response of heterotrophic bacteria in our sampled soil. This technique worked by quantitively measuring the reduction rate of 31 sole carbon substrates (Table S1 in Supporting Information S1) that are known to have high discriminatory power in soil bacterial communities (Hitzl et al., 1997). Substrate utilization patterns were used as an indicator of metabolic potential (Stefanowicz, 2006).120 μL of GF/D slurry was pipetted into the wells and stored in the dark at room temperature. Purple coloration from substrate reduction was optically measured at an absorbance of 590 nm using a Synergy H1 microplate reader (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA). Absorbance measurements were taken twice daily for the first week, and once daily for the second week until the average plate well color development (AWCD) plateaued. The AWCD of individual blank corrected substrates were normalized to a plate AWCD of 0.5 to account for differences in well inoculum density (Garland, 1997; Garland & Mills, 1991). Negative values for normalized substrate AWCD were considered as zero.

2.6. Statistics

All statistical analyses and graph building were carried out in RStudio version 4.2.1 (R Core Team, 2022). A permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA, with 999 permutations) was performed using vegan 2.6–2 (Oksanen et al., 2022) to evaluate global difference between soil horizons. The test was carried out using Euclidean distances with pigs as a blocking factor to account for inter‐individual variability. Seasonal and spatial differences in DOC, BR and BA were tested via linear mixed effects model with pigs set as a random effect using lme4 1.1.30 (Bates et al., 2015). This was followed by a two‐sided Dunnett's test with Bonferroni adjustment via multcomp 1.4–20 (Hothorn et al., 2008). Principal component analysis (PCA) was generated using stats 4.2.1 (R Core Team, 2022) to reveal patterns in DOM composition (DOC, spectral indices, PARAFAC components) along sampling distance and season. A PCA was similarly performed on the normalized AWCD of each Biolog EcoPlate™ substrate to examine spatial and temporal trends in bacterial metabolic potential. Partial least squares regression (PLSR) with leave‐one‐out cross‐validation was performed with plsdepot (Sanchez, 2012) to evaluate if the x‐variables of DOM composition (DOC, PARAFAC components, spectral indices) drove changes in the y‐variables of bacterial activity/function (BR, BA, metabolic potential). A linear regression, stats 4.2.1 (R Core Team, 2022), between the PLSR scores of t1 and u1 was additionally conducted to view the correlation between x and y variables over sampling distances and season. All multivariate analyses were performed on centered and scaled data. A significance value of 0.05 was adopted across all statistical analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Vertical Extent

A PERMANOVA was performed on the entirety of chemical and bacterial measures to evaluate if universal differences occurred within the A‐ and B‐horizons of the sampled soil. This was done to determine the vertical extent of the CDI's effect. Results indicated that the A‐horizon differed across both sampling distances (Df = 6, F = 1.463, p = 0.001) and season (Df = 2. F = 3.47, p = 0.001), for chemical and bacterial measures altogether. Dissimilarly, no differences were detected across sampling distance in the B‐horizon (Df = 6, F = 1.02, p = 0.326), but measures did demonstrate significant seasonal changes (Df = 2, F = 4.72, p = 0.001). Mean values for DOC, BR and BA were generally lower for the B‐horizon when compared to the A‐horizon (Figure S3 in Supporting Information S1). It was therefore concluded that the vertical extent of carcass decomposition did not exceed the A‐horizon, since the B‐horizon remained stable across all lateral distances. Only naturally occurring seasonal shifts in DOM and bacteria were measurable within the subsoil. For this reason, all subsequent results are focused only on the A‐horizon.

3.2. DOM Composition

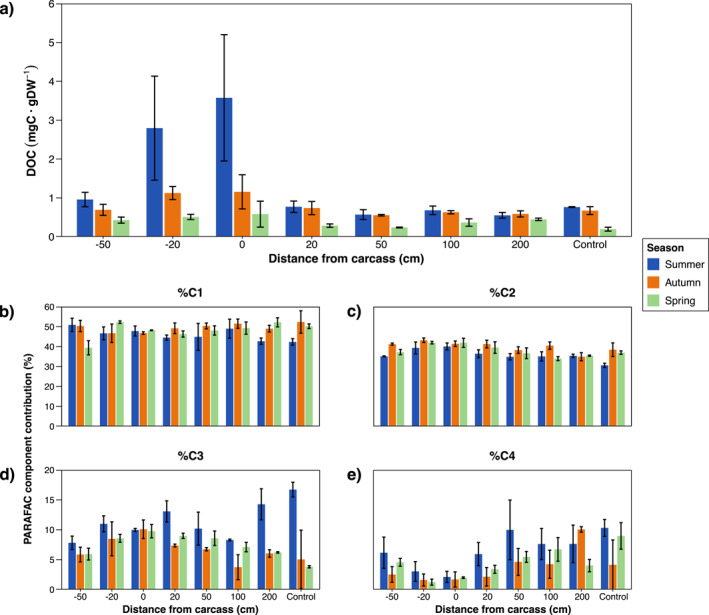

Linear mixed effect model revealed significant differences in DOC concentration within the A‐horizon across distance (Df = 7, F = 3.06, p = 0.015) and season (Df = 2, F = 7.66, p = 0.001). DOC in soil at −20 and 0 cm from the pig carcasses underwent the greatest degree of change in the summer, with a respective 266% and 368.16% increase when compared to the controls. These concentrations decreased over time but remained slightly elevated by the spring at an increase of 161% and 198% (Figure 1a).

Figure 1.

Observed seasonal trends in DOC concentration (a) and relative percent contribution of PARAFAC components C1 (b), C2 (c), C3 (d) and C4 (e) in soil of the A‐horizon sampled at varying distances from decomposing pig carcasses (n = 3). Values are expressed as the mean and standard error. Control samples taken outside of the experimental site are included as the furthest distance from the carcass.

The percent contribution of each PARAFAC component to total fluorescence varied greatly across distance and season. C1 generally remained stable over all sampling distances and seasons, for it represented plant‐derived humic substances that are universally present in a forested setting (Figure 1b). The greatest peak in C2 was observed at point −20 cm, with an increase from the control of 31%, 10% and 13% respectively for the summer, autumn, and spring seasons (Figure 1c). The opposite effect occurred for C4, where component contribution declined the most at −20 cm, resulting in a decrease of −79%, −49% and −85% across the three seasons (Figure 1e). The majority of sampling distances during the summer experienced a decrease in C3 contribution. This was because of unusually high C3 values obtained for the 200 cm and the control samples. Excluding the 200 cm and the controls, the next greatest peak in C3 for the summer was observed at 20 cm, which was 67% greater than the lowest value recorded at −50 cm. The greatest peak in C3 for the proceeding autumn and spring was observed at 0 cm, with respective increases of 160% and 154% from the controls (Figure 1d).

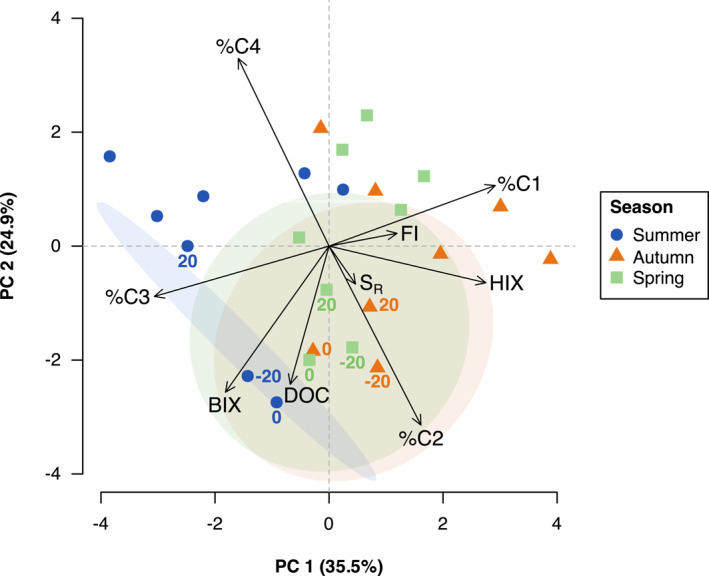

A principal component analysis (PCA) of relative PARAFAC component contribution (%C1–%C4), spectral indices (BIX, HIX, FI, SR) and DOC concentration demonstrated a shift in DOM composition across season and sampling distance (Figure 2). PC1 (35.4% explained variation) represented naturally occurring seasonal shifts, whereas PC2 (25.3% explained variation) distinguished the effect of carcass decomposition. Spring and autumn samples were similarly driven toward the right quadrants by the positive loadings of %C1, FI and HIX along PC1, whereas summer differed toward the left by the negative loading of %C3. Summer sampling distances closest to the carcasses (−20 and 0 cm) were strongly driven downwards by the negative loadings of DOC and BIX along PC2. Autumn and spring samples at −20, 0 and 20 cm were similarly driven by the negative loading of DOC, but also appeared strongly influenced by the negative loading of %C2 on PC2. All other sampling distances (−50, 50, 100, 200 cm) and controls across the three seasons were contrarily shifted toward the upper quadrants by the positive loading of %C4 along PC2. Furthermore, the small loading for S R suggested that strong variations in molecular size did not occur across season and sampling distance.

Figure 2.

PCA biplot of seasonal DOM composition (DOC, FI, HIX, BIX, SR, %C1–%C4) in soil of the A‐horizon sampled at varying distances from decomposing pig carcasses (n = 3). PCA includes 95% confidence ellipses for labeled points that were sampled closest to the carcasses (−20, 0 and 20 cm).

3.3. Bacterial Activity and Function

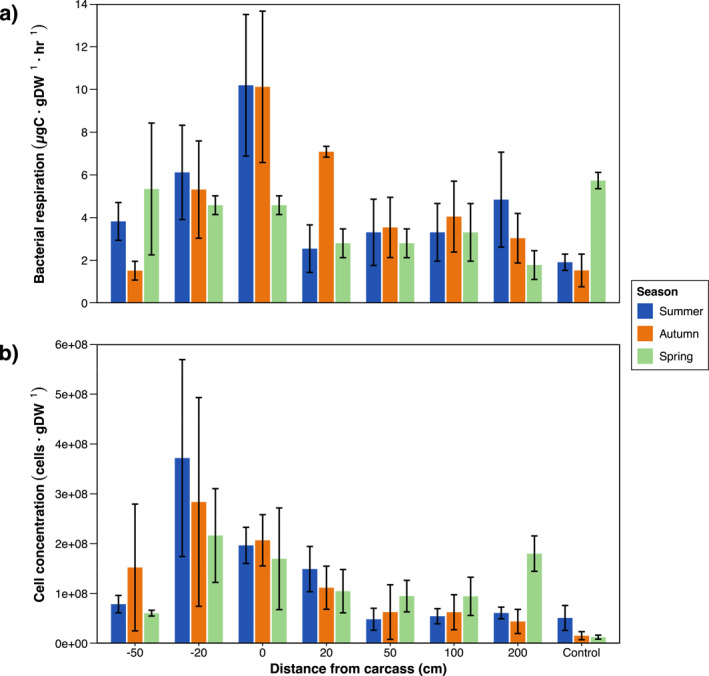

Mean rates of bacterial carbon respiration (BR) significantly differed across sampling distance (Df = 7, F = 2.95, p = 0.031) but not season according to a linear mixed effects model. Temporal trends were however noticeable, particularly for soil sampled closest to the carcasses (Figure 3a). At 0 cm, BR increased by 500% from control values during the summer season. Respiration rates remained at an increase of 400% in the autumn and decreased slightly below controls at −11% in the spring.

Figure 3.

Seasonal trends in bacterial carbon respiration (a) and bacterial cell abundance (b) in soil of the A‐horizon sampled at varying distances from decomposing pig carcasses (n = 3). Values are expressed as the mean and standard error. Control samples taken outside of the experimental site are included as the furthest distance from the carcass.

Mean cell counts for bacterial abundance (BA) similarly differed across distance (Df = 7, F = 3.51, p = 0.002). Although no significant differences were detected across season, clear temporal trends also emerged for samples taken at −20 and 0 cm (Figure 3b). These samples respectively experienced a summer increase of 628%, and 285% from the controls. Absolute bacterial cell concentrations at these distances gradually decreased over time, but still remained elevated relative to the controls at an increase of 1,736% and 1,238% in the autumn, and 1,619% and 1,248% in the spring.

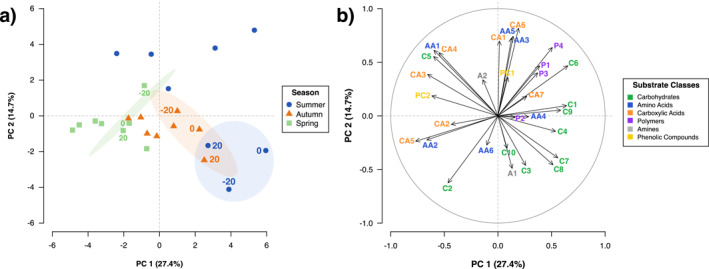

Changes in bacterial metabolic potential were assessed using Biolog EcoPlates™. A PCA (Figure 4) of average well color development (AWCD) demonstrated a shift in substrate utilization patterns across season and sampling distance. Seasonal effects were mostly distinguished by PC2 (14.7% explained variation), with autumn and spring falling within the lower quadrants, and summer within the upper quadrants. Decomposition driven shifts in metabolic potential appeared along both PC1 (27.4% explained variation) and PC2. Summer samples at −20, 0 and 20 cm were distinct from all other distances and appeared to be strongly driven by the negative PC2 loadings of several carbohydrate substrates (C3, C4, C7, C8, C10) and Phenylethyl‐amine (A1). In addition to PC2, the positive PC1 loadings for the same substrates contributed to a shift in −20, 0 and 20 cm autumn samples. Pig carcass decomposition therefore shifted scores toward the lower right quadrant of the PCA. Metabolic potential for the remaining autumn (−50, 50, 100, 200 cm and controls) and spring samples were notably influenced by the negative loadings of carboxylic acids (CA2, CA3, CA4, CA5) along PC1. The lack of separation for points −20, 0 and 20 cm from further sampling distances in the spring suggested a return to baseline seasonal substrate utilization patterns.

Figure 4.

PCA score (a) and loading (b) plots of seasonal substrate metabolic potential of bacteria in soil of the A‐horizon sampled at varying distances from decomposing pig carcasses (n = 3). Substrates are categorized into their respective chemical classes: carbohydrates (green C1‐C10), amino acids (blue AA1‐AA6), carboxylic acids (orange CA1‐CA7), polymers (purple P1‐P4), amines (gray A1‐A2) and phenolic compounds (yellow PC1‐PC2). PCA score biplot (a) includes 95% confidence ellipses for the labeled points sampled closest to the carcasses (−20, 0, 20 cm).

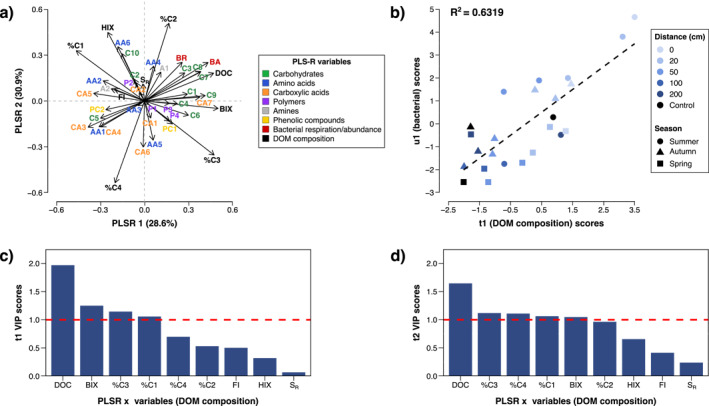

3.4. Influence of DOM Composition on Bacterial Responses

Partial least squares regression (PLS‐R) was performed to evaluate the influence of carcass related DOM compositional changes on bacterial function and activity (Figure 5a). First two components of the model explained 59.5% of the total variation. Bacterial respiration, cell abundance and the metabolism of carbohydrate substrates C3, C7 and C8 were highly correlated with DOC concentration. These bacterial response variables were also positively correlated to BIX and %C2, but to a lesser extent. BIX was however strongly correlated with an increased metabolic potential for C1, C4, C6, C9, and CA7. %C2 was moreover closely related to A1 and AA4 substrate reduction. A linear regression of the x‐scores (t1) and y‐scores (u1) from the first component of the PLS‐R model demonstrated a positive linear relationship (R 2 = 0.632) between the model scores for DOM composition and bacterial responses (Figure 5b). Samples were uniquely distributed along the linear regression based on season and distance; with further distances (−50, 50, 100, 200 cm, controls) in the autumn and spring visibly clustering toward the lower left of the plot, versus proximal (−20, 0, 20 cm) samples in the summer extending more toward the upper right. DOC concentration, BIX and % C3 were identified as the top three most influential predictor variables of bacterial responses, as seen in the variables of importance to prediction (VIP) scores (Figures 5c and 5d).

Figure 5.

PLS‐R biplot (a) of bacterial responses (activity and function) in relation to DOM composition in soil of the A‐horizon sampled at varying distances from decomposing pig carcasses (n = 3). Linear regression (b) of PLS‐R t1 and u1 scores categorized by sampling distance and season. Score plots for DOM composition variables of importance to projection (VIP) that contributed to the t1 (c) and t2 (d) components of the PLS‐R model.

4. Discussion

4.1. Spatial Patterns

Large mammalian carrion comprise approximately 20% of carbon in mass and have been estimated to contribute over 1% of organic matter inputs in some terrestrial environments (Carter et al., 2007). It was therefore unsurprising that we observed a localized increase in soil DOC during the summer season, following the decomposition of surface deposited pig carcasses (day 55). Levels were greatest beneath the carcasses (0 cm), followed by a sampling distance of 20 cm uphill. Soil DOC enrichment has likewise been recorded in soils sampled directly underneath animal and human remains (Chowdhury et al., 2019; Fancher et al., 2017; Keenan et al., 2018; Macdonald et al., 2014; Woelber‐Kastner et al., 2021). Though, small increases in DOC were dissimilarly recorded up to 5 m away from pig carcasses placed on principally clayey soils in Texas (Heo et al., 2021). The diffusion of decomposition products was furthermore anticipated to follow the slope of our experimental terrain since Aitkenhead‐Peterson et al. (2012) reported a lengthy downhill leaching of DOC from cadavers. We therefore did not foresee an uphill increase. The slope of our terrain may not have been sufficient to influence the directionality of leaching. Instead, the location of carcass rupture, the displacement of the carcass during bloating and the movement of maggot masses may have had a greater effect. We moreover found that DOC increases were vertically bound to the A‐horizon (≤14 cm). A limited diffusion of cadaver DOC down the soil profile was also reported by Fancher et al. (2017), who observed concentration changes only up to depths of 15 cm. Interstudy comparisons between biogeographic regions must however be done with caution since differences in soil type, precipitation, cadaver mass, adipose deposits, ante‐ or peri‐mortem trauma, scavenging and bacterial mineralization can all influence the spatial extent of CDI measures (Aitkenhead‐Peterson et al., 2012; Barton et al., 2020; Coe, 1978; Damann et al., 2012; Heo et al., 2021). Within the context of our study, the elevated DOC levels were particularly interpreted as a spatially constrained increase in soil DOM quantity.

Optical analyses revealed that the spatial pattern in DOM quantity was accompanied by an increase in quality. This was seen by a rise in the relative DOM fluorescent signal for labile amino acids (tyrosine, tryptophan). Similar protein‐like fluorescence has been observed in an Alaskan creek following annual salmon spawning mortalities (Hood et al., 2007). Such compositional changes could be partially attributed to the degradation of protein‐rich soft‐tissue, as shown by Nolan et al. (2019) who identified known blood and tissue components in the peptide profile of porcine decomposition fluid. However, the turn‐over rate of free amino acids in soils is universally rapid due to nitrogen limitations (Macdonald et al., 2014). By the time the first summer soil core was collected, a portion of carcass‐derived proteinaceous DOM may have already been assimilated into microbial biomass or lost to mineralization. Keenan et al. (2019) reported CDI 15N isotopic profiles that are suggestive of both carrion and microbial inputs, and Macdonald et al. (2014) attributed only 40% of N‐inputs to carrion‐derived free amino acids and peptides. The positive correlation we observed between protein‐like fluorescence (C3) and the freshness index (BIX) (Figure 2) similarly indicated that the proteinaceous DOM in our CDI soil was mostly microbial in origin. These protein inputs may have also been responsible for the depletion in phenol‐like DOM compounds (Figure 1). Phenolic compounds, like tannins, are naturally introduced to soil systems by plant root exudates or decaying leaf litter (Schmidt et al., 2013). Proteins, such as those generated during CDI formation, can polymerize with these endogenous phenols to produce recalcitrant humic acids. This phenomenon has been especially observed during composting and is known as the phenol‐protein theory of humification (Sánchez–Monedero et al., 1999; Wu et al., 2017). The conversion of phenols to humic substances would moreover explain the negative correlation that we obtained between phenol‐like (C4) and humic‐like (C2) DOM fluorescence (Figure 2). Altogether, fluorescence spectroscopy was capable of detecting distinct changes in DOM chemical quality within CDI soils, and further highlighted the important implication of microbial sources in the development of labile and humic DOM fractions following body decomposition.

Topsoil within 20 cm laterally from the carcasses also exhibited elevated bacterial activity (respiration) and cell abundance. Cell counts could have been affected by stimulated cell growth from labile inputs or from the introduction of carcass‐associated gut bacteria, which have been found to persist in soil up to 198 days post‐mortem (Cobaugh et al., 2015; Prescott & Vesterdal, 2021). Spatial patterns in BA nevertheless did not mirror the measured spike in BR, particularly at 0 cm, thus indicating a possible increase in cell‐specific respiration. Resource dense environments, like CDIs, tend to select for copiotroph bacteria with high metabolic demands (Strickland & Wickings, 2015). The selection for copiotrophic groups has been repeatedly observed in CDI communities, where Proteobacteria increasingly dominate following the purging of decomposition fluids. The surge in respiration could have similarly been produced by shifts in the metabolic strategies of native soil bacteria (Cobaugh et al., 2015; Finley et al., 2016; Metcalf et al., 2013; Singh et al., 2018). These marked increases in activity could have promoted rates of carbon mineralization and loss that were greater than the rate of CDI diffusion. This would explain the small spatial extent of carcass DOC. Other soil microbial communities, like fungi and protists, undoubtedly also contributed to CDI respiration. However, in this study we decided to isolate and focus on the response of prokaryotic groups that dominate CDI soils and labile DOM decomposition (Chapin et al., 2002; Strickland & Wickings, 2015). Non‐bacterial groups should be included in future studies to reveal competitive and trophic interactions that can potentially influence CDI outcomes.

Biolog EcoPlate™ assays also demonstrated a shift in bacterial metabolic potential. Some soil bacteria in proximity to the carcasses preferentially utilized carbohydrate substrates. A similar response has been seen in soils amended with other high‐quality resources like animal manure and biochar (Ayaz et al., 2022; Chakraborty et al., 2011). Microbial community structure and function are highly related (Fuhrman, 2009), therefore the reduction of labile carbohydrates could echo the high energy needs of a growing copiotroph population. Glucose‐1‐Phosphate (C8) and D‐Cellobiose (C7) were carbohydrates that were notably degraded by CDI communities. The former was previously identified as a likely metabolic indicator of pig carcass decomposition by Heo et al. (2020), whereas the latter may reflect the metabolism of pig‐derived cellulolytic bacteria (Checcucci et al., 2021). The metabolic preference for these substrates may therefore be functional markers of a bacterial community that is associated with pig carcass decomposition.

Despite the characterized increase in labile protein‐like DOM, the CDI bacterial community did not demonstrate a preferential utilization of EcoPlate™ amino‐acid substrates. Fluorescence spectroscopy is unfortunately restricted in the detection of carbohydrate compounds, so we were unable to assess their contribution to the labile DOM pool. Bacteria can however have a variable preference for carbohydrates and amino acids, regardless of the relative substrate quantities. The differential use of carbohydrates and proteins can arise from fluctuations in resource C:N, substrate allocation (energy VS biosynthesis), the availability of non‐protein nitrogenous compounds (e.g., ammonia), substrate accessibility, and/or physiological adaptations (Chapin et al., 2002; Weiss & Simon, 1999). This isn't to say that a metabolic preference for amino acids did not occur earlier in CDI formation, prior to summer sampling.

Differential DOM composition from leaf‐litter and root exudates has been well‐established as a regulator of microbial patchiness in forest soils (de Graaff et al., 2010; Tian et al., 2015; Yano et al., 2005). Labile compounds from these sources are particularly recognized to stimulate bacterial metabolic activity through the alleviation of energy and nutrient limitations (Bray et al., 2012). We found that this DOM‐bacterial relationship remained true in CDI soils. Partial least squares regression analysis listed high DOM quantity (DOC) and quality (%C3, BIX) as important predictors of bacterial activity (BR) and function (BA, metabolic potential) (Figures 5c and 5d). A strong gradient over sampling distance was also seen in the relationship between the model scores for DOM composition (t1) and bacterial responses (u1) (Figure 5). This spatial connection between carcass input chemistry and bacterial trends reinforces the view of a biochemical “hot spot” and further suggests that DOM composition is worth considering when examining microbial variabilities in CDIs.

4.2. Temporal and Seasonal Patterns

The biochemical disturbances described above were found to be temporally short‐lived. As hypothesized, heightened bacterial activity and functional changes led to the rapid consumption and transformation of carcass inputs. We saw a steep decrease in soil DOC levels between summer and autumn (day 156), but concentrations still remained slightly more elevated than non‐CDI soils (>20 cm). This decline was surely because of the atmospheric loss of CO2 and other carbon‐containing gases evolved from bacterial respiration (Putman, 1978). The decrease in quantity also coincided with a secondary shift in DOM quality, where the composition became increasingly characterized by microbial humic‐like compounds instead of labile proteins. As labile DOM inputs were being respired for energy use, some of it would also have been microbially converted into bulky biomass components, metabolites, polymeric slimes, or polymerizing intermediates (Guggenberger, 2005; Strawn et al., 2015). These residues could have then contributed to the growing fraction of microbial humic DOM. The accumulation of recalcitrant microbial products has been reported following labile additions from plant matter (Cotrufo et al., 2013; Tamura & Suseela, 2021; Tamura & Tharayil, 2014). But to our knowledge, this is the first time that a temporal switch from labile to humic DOM has been observed as the result of inputs and microbial activity associated with terrestrial animal decomposition. This supports the theories of Strickland and Wickings (2015) who suggested that the microbially mediated stabilization of organic matter is likely to occur following labile carcass inputs. These evolved CDI humic substances could have implications in generating patches of improved soil structure, aeration and water holding capacity by promoting the formation of stable aggregates (Chaney & Swift, 1984; Foth, 1990).

Ambient temperature can be an important temporal regulator of soil microbial processes, especially in temperate regions that experience extreme seasonal variabilities (Birgander et al., 2018; Kritzberg & Bååth, 2022). Freezing temperatures can limit the availability of liquid water and decrease enzyme reaction rates (Arcus & Mulholland, 2020; Drotz et al., 2009). This is why microbial processes are often assumed to slow‐down or cease in sub‐zero conditions. Even with these temperature‐related pressures, we found that CDI bacterial responses were maintained throughout the cooler autumn season. Insulation from fat deposits and snow coverage (Figure S4 in Supporting Information S1) likely aided in decoupling ambient and soil temperatures by helping to retain heat. Organic matter inputs also likely contributed to the freezing‐point depression of water by lowering matric and osmotic potentials (Drotz et al., 2009). Together, this could have buffered CDI microbial communities from freezing above‐ground conditions. This would explain why BR and BA, although reduced from their summer values, remained noticeably elevated when compared to the surrounding soil. Spikes in CO2 efflux and bacterial cell counts have similarly been seen in soils under mummified seal remains in an annually cold Antarctic environment (Tiao et al., 2012). Our results further suggest that the insulative effect of decomposed carrion also extends to the metabolic profile of soil bacteria. CDI communities managed to maintain their metabolic preference for carbohydrates, even when faced with an almost 20°C difference in ambient temperature (Figure S5 in Supporting Information S1) between the summer and autumn seasons. This metabolic consistency differs from Pechal et al. (2013), who attributed temperature variabilities to their observed differences in seasonal and annual Biolog profiles of pig carcasses. This suspected temperature sensitivity was however seen in samples taken from the skin and buccal cavity, which are areas that are more directly exposed to environmental conditions. Rather, the results of our study suggest that decomposed carrion may provide a protective effect to soil bacteria and help to reduce temperature‐dependent shifts in soil bacterial metabolic activity.

The persistence of bacterial activity through the cooler months was also evident in the DOM composition of spring samples (day 324). By this point, DOC concentrations in CDI soils had returned to almost baseline levels, though DOM remained distinctly characterized by microbial humic compounds. This could imply that losses in DOM quantity were related to microbial processes that were sustained throughout the autumn and winter. Snowmelt could have had a dilution effect on DOC, and the presence of anti‐scavenging cages may have also obstructed leaf coverage that could have replenished vegetal humic‐ and phenol‐like DOM. Nevertheless, evidence of continued bacterial respiration, growth, and enzyme synthesis under sub‐zero conditions has been repeatedly shown in soil incubation studies and arctic field experiments (Drotz, Sparrman, Nilsson, et al., 2010, Drotz, Sparrman, Nilsson, et al., 2010; McMahon et al., 2009; Michaelson & Ping, 2003; Nikrad et al., 2016). It is therefore not unreasonable to assume that soil bacteria continued to transform carcass inputs under Quebec (Canada) winter conditions. Persistent and even elevated bacterial activity throughout the autumn and winter seasons are likely to become more pronounced as global temperatures continue to rise in the face of climate change. This is expected to generate accelerated rates of carcass decomposition and soil DOM processing, thus altering the above reported temporal CDI trends (O’Donnell et al., 2016; Parmenter & Macmahon, 2009).

The resulting spring depletion in DOM quantity and quality meant that bacterial activity was no longer optimally supported. CDI respiration rates were further reduced towards or below control values, even in the presence of inflated cell counts. This could have emerged from a decrease in cell specific respiration, but it must be noted that we did not stain for viability. Therefore, BA likely constituted both living, dead and dormant cells. Spring CDI microbial communities additionally displayed a decrease in substrate class specificity and began to target a broader range of less energetically favourable compounds (e.g., carboxylic acids, phenolic compounds). CDI substrate utilization patterns were less distinct and resembled more the profiles of non‐affected soils. The exhaustion of labile DOM inputs may have facilitated the reestablishment of some endogenous phyla consisting of metabolically diverse oligotrophs (e.g., Acidobacteria). But it was unlikely that CDI soils fully returned to their native community. Alterations in bacterial community composition have been detected in soils as far as 10 years after swine carcass decomposition (Burcham et al., 2021). The spring convergence in Biolog profiles between CDI and undisturbed soils could have resulted from functional redundancies that emerged from shifting metabolic pathways. This idea is supported by Singh et al. (2018) who saw a recovery in mineralizable carbon and citric acid respiration despite a prolonged (732 days) disruption in CDI community composition. Whether our observed metabolic profiles and activity were because of community assembly or individual strategies, they demonstrated that CDI bacteria were functionally restored almost a year after carcass placement.

5. Conclusions

Our study demonstrated a distinct, long‐lasting, and spatially constrained disturbance to soil DOM chemical composition following the decomposition of pig carcasses in a Canadian forested environment. The high quantity and quality of DOM that was initially inputted into the soil was either progressively respired as CO2 or transformed to recalcitrant humic‐like compounds by bacterial communities. Throughout the entirety of the study, DOM characteristics remained discernible from the vegetal humic signal of unaffected soils. Soil DOM composition may therefore be a suitable chemical marker for detecting and mapping areas affected by body decomposition, even in later stages of decay.

Soil DOM composition was moreover found to be an important driver of bacterial responses to carcass decomposition. Large amounts of labile compounds first favored elevated rates of bacterial respiration and carbohydrate metabolism. These bacterial changes persisted over the cooler autumn and winter months, which also contributed to the sustained consumption and transformation of DOM inputs. The eventual depletion of labile DOM was then seen to be concurrent with the functional recovery of soil bacterial communities by the spring season.

These findings deepen our understanding of the relationship between animal decomposition, soil chemistry and microbial ecological processes, particularly the cycling and stabilization of organic matter within a cold‐climate ecosystem. The study of individual carcasses and the exclusion of scavengers provides a snapshot of the maximum effect a CDI can produce in a temperate forested environment. This can serve as a basis to hypothesize outcomes in scenarios where tissue loss and dispersion occurs from scavenging or larger spatial inputs are generated from mass mortalities. Our findings add to a growing conceptual framework of carrion's ecological contribution. Such information will be crucial in managing ecosystem health following fluxes in the distribution and density of animal populations produced by anthropogenic and climatic factors (e.g., livestock rearing, wildfires, mass starvation) (Barton et al., 2019).

Supporting information

Supporting Information S1

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dany Bouchard at the Laboratoire d'analyses en écologie aquatique et sédimentologie (LAEAS) of the Université du Québec à Trois‐Rivières (UQTR) for help with DOC and absorbance/fluorescence instrumentation and the lab of Dr. Jérôme Comte at the Institut national de la recherche scientifique (INRS) ‐ Québec, Canada for training and lending use of their flow cytometer. We are thankful to the UQTR taphonomy team (Rushali Dargan, Ariane Durand‐Guévin, Gabrielle Harvey, Julie‐Éléonore Maisonhaute, Sophie Morel, Frédérique Ouimet, Darshil Patel, Karelle Séguin) and Dr. Christopher Watson for helping out in the field, and Jade Dormoy‐Boulanger, Elizabeth Grater, Charles Martin and Mathieu Michaud for assisting with statistical analyses and R. Lastly, a huge thanks to Dr. David O. Carter at Chaminade University of Honolulu for his insight and guidance. This work was supported by funds from the Fonds de Recherche du Québec ‐ AUDACE program (Frank Crispino), the Canada 150 Research Chair in Forensic Thanatology of Shari Forbes, and the NSERC‐Discovery grant of François Guillemette.

Pecsi, E. L. , Forbes, S. , & Guillemette, F. (2024). Organic matter composition as a driver of soil bacterial responses to pig carcass decomposition in a Canadian continental climate. Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences, 129, e2024JG008355. 10.1029/2024JG008355

Data Availability Statement

All data that supports the findings of this study is openly available through the Borealis Canadian Dataverse Repository (Pecsi et al., 2024) for use under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The validated PARAFAC model generated in this study is accessible through the OpenFluor database (Murphy et al., 2013) under model ID 7906.

References

- Achinewhu, S. C. , Ogbonna, C. C. , & Hart, A. D. (1995). Chemical composition of indigenous wild herbs, spices, fruits, nuts and leafy vegetables used as food. Plant Foods for Human Nutrition, 48(4), 341–348. 10.1007/BF01088493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aitkenhead‐Peterson, J. A. , Owings, C. G. , Alexander, M. B. , Larison, N. , & Bytheway, J. A. (2012). Mapping the lateral extent of human cadaver decomposition with soil chemistry. Forensic Science International, 216(1–3), 127–134. 10.1016/j.forsciint.2011.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcus, V. L. , & Mulholland, A. J. (2020). Temperature, dynamics, and enzyme‐catalyzed reaction rates. Annual Review of Biophysics, 49(1), 163–180. 10.1146/annurev-biophys-121219-081520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayaz, M. , Feizienė, D. , Feiza, V. , Tilvikienė, V. , Baltrėnaitė‐Gedienė, E. , & Khan, A. (2022). The impact of swine manure biochar on the physical properties and microbial activity of loamy soils. Plants, 11(13), 1729. 10.3390/plants11131729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton, P. S. (2015). The role of carrion in ecosystems. In Benbow M. E., Tomberlin J. K., & Tarone A. M. (Eds.), Carrion ecology, evolution, and their applications (pp. 273–290). CRC Press. 10.1201/b18819 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barton, P. S. , Cunningham, S. A. , Lindenmayer, D. B. , & Manning, A. D. (2013). The role of carrion in maintaining biodiversity and ecological processes in terrestrial ecosystems. Oecologia, 171(4), 761–772. 10.1007/s00442-012-2460-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton, P. S. , Cunningham, S. A. , Macdonald, B. C. , McIntyre, S. , Lindenmayer, D. B. , & Manning, A. D. (2013). Species traits predict assemblage dynamics at ephemeral resource patches created by carrion. PLoS One, 8(1), e53961. 10.1371/journal.pone.0053961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton, P. S. , Evans, M. J. , Foster, C. N. , Pechal, J. L. , Bump, J. K. , Quaggiotto, M.‐M. , & Benbow, M. E. (2019). Towards quantifying carrion biomass in ecosystems. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 34(10), 950–961. 10.1016/j.tree.2019.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton, P. S. , Reboldi, A. , Dawson, B. M. , Ueland, M. , Strong, C. , & Wallman, J. F. (2020). Soil chemical markers distinguishing human and pig decomposition islands: A preliminary study. Forensic Science, Medicine and Pathology, 16(1), 605–612. 10.1007/s12024-020-00297-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates, D. , Mächler, M. , Bolker, B. , & Walker, S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed‐effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1), 1–48. 10.18637/jss.v067.i01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Birgander, J. , Olsson, P. A. , & Rousk, J. (2018). The responses of microbial temperature relationships to seasonal change and winter warming in a temperate grassland. Global Change Biology, 24(8), 3357–3367. 10.1111/gcb.14060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bittar, T. B. , Berger, S. A. , Birsa, L. M. , Walters, T. L. , Thompson, M. E. , Spencer, R. G. M. , et al. (2016). Seasonal dynamics of dissolved, particulate and microbial components of a tidal saltmarsh‐dominated estuary under contrasting levels of freshwater discharge. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 182(1), 72–85. 10.1016/j.ecss.2016.08.046 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bray, S. R. , Kitajima, K. , & Mack, M. C. (2012). Temporal dynamics of microbial communities on decomposing leaf litter of 10 plant species in relation to decomposition rate. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 49(1), 30–37. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2012.02.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Breton, H. A. , Kirkwood, A. E. , Carter, D. O. , & Forbes, S. L. (2016). Changes in soil microbial activity following cadaver decomposition during spring and summer months in southern Ontario. In Kars H. & van den Eijkel L. (Eds.), Soil in criminal and environmental forensics (pp. 243–262). Springer. 10.1007/978-3-319-33115-7_16 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burcham, Z. M. , Weitzel, M. A. , Hodges, L. D. , Deel, H. L. , & Metcalf, J. L. (2021). A pilot study characterizing gravesoil bacterial communities a decade after swine decomposition. Forensic Science International, 323(1), 110782. 10.1016/j.forsciint.2021.110782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter, D. O. , Junkins, E. N. , & Kodama, W. A. (2017). A primer on microbiology. In Carter D. O., Tomberlin J. K., Benbow M. E., & Metcalf J. L. (Eds.), Forensic microbiology (pp. 1–24). Wiley and Sons. 10.1002/9781119062585.ch1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carter, D. O. , Yellowlees, D. , & Tibbett, M. (2007). Cadaver decomposition in terrestrial ecosystems. Naturwissenschaften, 94(1), 12–24. 10.1007/s00114-006-0159-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, A. , Chakrabarti, K. , Chakraborty, A. , & Ghosh, S. (2011). Effect of long‐term fertilizers and manure application on microbial biomass and microbial activity of a tropical agricultural soil. Biology and Fertility of Soils, 47(2), 227–233. 10.1007/s00374-010-0509-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaney, K. , & Swift, R. S. (1984). The influence of organic matter on aggregate stability in some British soils. Journal of Soil Science, 35(2), 223–230. 10.1111/j.1365-2389.1984.tb00278.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chapin, F. S. , Matson, P. A. , & Mooney, H. A. (2002). Terrestrial decomposition. In Chapin F. S., Matson P. A., & Vitousek P. M. (Eds.), Principles of terrestrial ecosystem ecology (pp. 151–175). Springer. 10.1007/0-387-21663-4_7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Checcucci, A. , Luise, D. , Modesto, M. , Correa, F. , Bosi, P. , Mattarelli, P. , & Trevisi, P. (2021). Assessment of Biolog EcoplateTM method for functional metabolic diversity of aerotolerant pig fecal microbiota. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 105(14), 6033–6045. 10.1007/s00253-021-11449-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chenu, C. , Rumpel, C. , & Lehmann, J. (2014). Methods for studying soil organic matter: Nature, dynamics, spatial accessibility, and interactions with minerals. In Paul E. A. & Frey S. D. (Eds.), Soil microbiology, ecology and biochemistry (pp. 369–406). Elsevier Inc. 10.1016/B978-0-12-822941-5.00013-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, S. , Kim, G.‐H. , Ok, Y. S. , & Bolan, N. (2019). Effect of carbon and nitrogen mobilization from livestock mortalities on nitrogen dynamics in soil. Process Safety and Environmental Protection, 122(1), 153–160. 10.1016/j.psep.2018.11.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland, C. C. , Nemergut, D. R. , Schmidt, S. K. , & Townsend, A. R. (2007). Increases in soil respiration following labile carbon additions linked to rapid shifts in soil microbial community composition. Biogeochemistry, 82(1), 229–240. 10.1007/s10533-006-9065-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cobaugh, K. L. , Schaeffer, S. M. , & DeBruyn, J. M. (2015). Functional and structural succession of soil microbial communities below decomposing human cadavers. PLoS One, 10(6), e0130201. 10.1371/journal.pone.0130201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coe, M. (1978). The decomposition of elephant carcases in the Tsavo (East) national Park, Kenya. Journal of Arid Environments, 1(1), 71–86. 10.1016/S0140-1963(18)31756-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cory, R. M. , & McKnight, D. M. (2005). Fluorescence spectroscopy reveals ubiquitous presence of oxidized and reduced quinones in dissolved organic matter. Environmental Science and Technology, 39(21), 8142–8149. 10.1021/es0506962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotrufo, M. F. , Wallenstein, M. D. , Boot, C. M. , Denef, K. , & Paul, E. (2013). The microbial efficiency‐matrix stabilization (MEMS) framework integrates plant litter decomposition with soil organic matter stabilization: Do labile plant inputs form stable soil organic matter? Global Change Biology, 19(4), 988–995. 10.1111/gcb.12113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dainard, P. G. , Guéguen, C. , Yamamoto‐Kawai, M. , Williams, W. J. , & Hutchings, J. K. (2019). Interannual variability in the absorption and fluorescence characteristics of dissolved organic matter in the Canada Basin polar mixed waters. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 124(7), 5258–5269. 10.1029/2018JC014896 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Damann, F. E. , Tanittaisong, A. , & Carter, D. O. (2012). Potential carcass enrichment of the university of Tennessee anthropology research facility: A baseline survey of edaphic features. Forensic Science International, 222(1), 4–10. 10.1016/j.forsciint.2012.04.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Andrilli, J. , Junker, J. R. , Smith, H. J. , Scholl, E. A. , & Foreman, C. M. (2019). DOM composition alters ecosystem function during microbial processing of isolated sources. Biogeochemistry, 142(2), 281–298. 10.1007/s10533-018-00534-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Graaff, M.‐A. , Classen, A. T. , Castro, H. F. , & Schadt, C. W. (2010). Labile soil carbon inputs mediate the soil microbial community composition and plant residue decomposition rates. New Phytologist, 188(4), 1055–1064. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03427.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lange, C. F. M. , Morel, P. C. H. , & Birkett, S. H. (2003). Modeling chemical and physical body composition of the growing pig. Journal of Animal Science, 81(14.2), E159–E165. 10.2527/2003.8114_suppl_2E159x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drotz, S. , Tilston, E. L. , Sparrman, T. , Schleucher, J. , Nilsson, M. , & Öquist, M. G. (2009). Contributions of matric and osmotic potentials to the unfrozen water content of frozen soils. Geoderma, 148(3), 392–398. 10.1016/j.geoderma.2008.11.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drotz, S. H. , Sparrman, T. , Nilsson, M. B. , Schleucher, J. , & Öquist, M. G. (2010). Both catabolic and anabolic heterotrophic microbial activity proceed in frozen soils. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(49), 21046–21051. 10.1073/pnas.1008885107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drotz, S. H. , Sparrman, T. , Schleucher, J. , Nilsson, M. , & Öquist, M. G. (2010). Effects of soil organic matter composition on unfrozen water content and heterotrophic CO2 production of frozen soils. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 74(8), 2281–2290. 10.1016/j.gca.2010.01.026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fancher, J. P. , Aitkenhead‐Peterson, J. A. , Farris, T. , Mix, K. , Schwab, A. P. , Wescott, D. J. , & Hamilton, M. D. (2017). An evaluation of soil chemistry in human cadaver decomposition islands: Potential for estimating postmortem interval (PMI). Forensic Science International, 279(1), 130–139. 10.1016/j.forsciint.2017.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fellman, J. B. , Hood, E. , & Spencer, R. G. M. (2010). Fluorescence spectroscopy opens new windows into dissolved organic matter dynamics in freshwater ecosystems: A review. Limnology & Oceanography, 55(6), 2452–2462. 10.4319/lo.2010.55.6.2452 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fiedler, S. , Kaiser, K. , & Fournier, B. (2023). Cadaver imprint on soil chemistry and microbes ‐ knowns, unknowns, and perspectives. Frontiers in Soil Science, 3(1), 1107432. 10.3389/fsoil.2023.1107432 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Finley, S. J. , Pechal, J. L. , Benbow, M. E. , Robertson, B. K. , & Javan, G. T. (2016). Microbial signatures of cadaver gravesoil during decomposition. Microbial Ecology, 71(3), 524–529. 10.1007/s00248-015-0725-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes, S. L. , & Dadour, I. (2009). The soil environment and forensic entomology. In Byrd J. H. & Castner J. L. (Eds.), Forensic entomology (pp. 407–426). CRC Press. 10.1201/NOE0849392153 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foth, H. D. (1990). Soil organic matter. In Fundamentals of soil science (8th ed., pp. 133–147). John Wiley and Sons. ISBN: 978‐0‐471‐52279‐9. [Google Scholar]

- Fuhrman, J. A. (2009). Microbial community structure and its functional implications. Nature, 459(7244), 193–199. 10.1038/nature08058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, R. D. , Diéguez, M. C. , Gerea, M. , Garcia, P. E. , & Reissig, M. (2018). Characterization and reactivity continuum of dissolved organic matter in forested headwater catchments of Andean Patagonia. Freshwater Biology, 63(9), 1049–1062. 10.1111/fwb.13114 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garland, J. L. (1997). Analysis and interpretation of community‐level physiological profiles in microbial ecology. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 24(4), 289–300. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.1997.tb00446.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garland, J. L. , & Mills, A. L. (1991). Classification and characterization of heterotrophic microbial communities on the basis of patterns of community‐level sole‐carbon‐source utilization. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 57(8), 2351–2359. 10.1128/aem.57.8.2351-2359.1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldfarb, K. C. , Karaoz, U. , Hanson, C. , Santee, C. A. , Bradford, M. A. , Treseder, K. K. , et al. (2011). Differential growth responses of soil bacterial taxa to carbon substrates of varying chemical recalcitrance. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2(1), 94. 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guggenberger, G. (2005). Humification and mineralization in soils. In Varma A. & Buscot F. (Eds.), Microorganisms in soils: Roles in genesis and functions (pp. 85–106). Springer. 10.1007/3-540-26609-7_4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hammes, F. , & Egli, T. (2010). Cytometric methods for measuring bacteria in water: Advantages, pitfalls and applications. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, 397(3), 1083–1095. 10.1007/s00216-010-3646-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, A. M. , Kraus, T. E. C. , Pellerin, B. A. , Fleck, J. A. , Downing, B. D. , & Bergamaschi, B. A. (2016). Optical properties of dissolved organic matter (DOM): Effects of biological and photolytic degradation. Limnology & Oceanography, 61(3), 1015–1032. 10.1002/lno.10270 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Helms, J. R. , Stubbins, A. , Ritchie, J. D. , Minor, E. C. , Kieber, D. J. , & Mopper, K. (2008). Absorption spectral slopes and slope ratios as indicators of molecular weight, source, and photobleaching of chromophoric dissolved organic matter. Limnology & Oceanography, 53(3), 955–969. 10.4319/lo.2008.53.3.0955 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heo, C. C. , Crippen, T. L. , Thornton, S. N. , & Tomberlin, J. K. (2020). Differential carbon utilization by bacteria in the soil surrounding and on swine carcasses with dipteran access delayed. Pure and Applied Geophysics, 178(1), 717–734. 10.1007/s00024-020-02608-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heo, C. C. , Tomberlin, J. K. , & Aitkenhead‐Peterson, J. A. (2021). Soil chemistry dynamics of Sus scrofa carcasses with and without delayed Diptera colonization. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 66(3), 947–959. 10.1111/1556-4029.14645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernes, P. J. , Bergamaschi, B. A. , Eckard, R. S. , & Spencer, R. G. M. (2009). Fluorescence‐based proxies for lignin in freshwater dissolved organic matter. Journal of Geophysical Research, 114(G4), 1–10. 10.1029/2009JG000938 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hilman, B. , Weiner, T. , Haran, T. , Masiello, C. A. , Gao, X. , & Angert, A. (2022). The apparent respiratory quotient of soils and tree stems and the processes that control it. Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences, 127(3), e2021JG006676. 10.1029/2021JG006676 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hitzl, W. , Rangger, A. , Sharma, S. , & Insam, H. (1997). Separation power of the 95 substrates of the BIOLOG system determined in various soils. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 22(3), 167–174. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.1997.tb00368.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hood, E. , Fellman, J. , & Edwards, R. T. (2007). Salmon influences on dissolved organic matter in a coastal temperate brownwater stream: An application of fluorescence spectroscopy. Limnology & Oceanography, 52(4), 1580–1587. 10.4319/lo.2007.52.4.1580 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hothorn, T. , Bretz, F. , & Westfall, P. (2008). Simultaneous inference in general parametric models. Biometrical Journal, 50(3), 346–363. 10.1002/bimj.200810425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huguet, A. , Vacher, L. , Relexans, S. , Saubusse, S. , Froidefond, J. M. , & Parlanti, E. (2009). Properties of fluorescent dissolved organic matter in the Gironde Estuary. Organic Geochemistry, 40(6), 706–719. 10.1016/j.orggeochem.2009.03.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ioan, B. , Manea, C. , Amariei, C. , Hanganu, B. , Statescu, L. , Solovastru, L. , & Manoilescu, I. (2017). The chemistry decomposition in human corpses. Revista de Chimie, 68(1), 1450–1454. 10.37358/RC.17.6.5672 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii, S. K. L. , & Boyer, T. H. (2012). Behavior of reoccurring PARAFAC components in fluorescent dissolved organic matter in natural and engineered systems: A critical review. Environmental Science and Technology, 46(4), 2006–2017. 10.1021/es2043504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobin, B. , Latendresse, C. , Grenier, M. , Maisonneuve, C. , & Sebbane, A. (2010). Recent landscape change at the ecoregion scale in Southern Québec (Canada), 1993–2001. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 164(1), 631–647. 10.1007/s10661-009-0918-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen, L. , Stedmon, C. A. , Kragh, T. , Markager, S. , Middelboe, M. , & Søndergaard, M. (2011). Global trends in the fluorescence characteristics and distribution of marine dissolved organic matter. Marine Chemistry, 126(1), 139–148. 10.1016/j.marchem.2011.05.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan, S. W. , Schaeffer, S. M. , & DeBruyn, J. M. (2019). Spatial changes in soil stable isotopic composition in response to carrion decomposition. Biogeosciences, 16(19), 3929–3939. 10.5194/bg-16-3929-2019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan, S. W. , Schaeffer, S. M. , Jin, V. L. , & DeBruyn, J. M. (2018). Mortality hotspots: Nitrogen cycling in forest soils during vertebrate decomposition. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 121(1), 165–176. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2018.03.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kritzberg, E. , & Bååth, E. (2022). Seasonal variation in temperature sensitivity of bacterial growth in a temperate soil and lake. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 98(10), fiac111. 10.1093/femsec/fiac111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapierre, J.‐F. , & del Giorgio, P. A. (2014). Partial coupling and differential regulation of biologically and photochemically labile dissolved organic carbon across boreal aquatic networks. Biogeosciences, 11(20), 5969–5985. 10.5194/bg-11-5969-2014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lerch, T. Z. , Nunan, N. , Dignac, M.‐F. , Chenu, C. , & Mariotti, A. (2011). Variations in the microbial isotopic fractionation during soil organic matter decomposition. Biogeochemistry, 10(1), 5–21. 10.1007/s10533-010-9432-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald, B. C. T. , Farrell, M. , Tuomi, S. , Barton, P. S. , Cunningham, S. A. , & Manning, A. D. (2014). Carrion decomposition causes large and lasting effects on soil amino acid and peptide flux. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 69(1), 132–140. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2013.10.042 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maie, N. , Scully, N. M. , Pisani, O. , & Jaffé, R. (2007). Composition of a protein‐like fluorophore of dissolved organic matter in coastal wetland and estuarine ecosystems. Water Research, 41(3), 563–570. 10.1016/j.watres.2006.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisonhaute, J.‐É. , & Forbes, S. L. (2020). Decomposition process and arthropod succession on pig carcasses in Quebec (Canada). Canadian Society of Forensic Science Journal, 5(1), 1–26. 10.1080/00085030.2020.1820799 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marín‐Spiotta, E. , Gruley, K. E. , Crawford, J. , Atkinson, E. E. , Miesel, J. R. , Greene, S. , et al. (2014). Paradigm shifts in soil organic matter research affect interpretations of aquatic carbon cycling: Transcending disciplinary and ecosystem boundaries. Biogeochemistry, 117(2), 279–297. 10.1007/s10533-013-9949-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mason, A. R. , Taylor, L. S. , & DeBruyn, J. M. (2023). Microbial ecology of vertebrate decomposition in terrestrial ecosystems. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 99(2), fiad006. 10.1093/femsec/fiad006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon, S. K. , Wallenstein, M. D. , & Schimel, J. P. (2009). Microbial growth in Arctic tundra soil at −2°C. Environmental Microbiology Reports, 1(2), 162–166. 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2009.00025.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Megyesi, M. S. , Nawrocki, S. P. , & Haskell, N. H. (2005). Using accumulated degree‐days to estimate the postmortem interval from decomposed human remains. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 50(3), 618–626. 10.1520/JFS2004017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metcalf, J. L. , Wegener Parfrey, L. , Gonzalez, A. , Lauber, C. L. , Knights, D. , Ackermann, G. , et al. (2013). A microbial clock provides an accurate estimate of the postmortem interval in a mouse model system. Elife, 2, e01104. 10.7554/eLife.01104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J. , Anderson, B. , & Carter, D. O. (2013). Seasonal variation of carcass decomposition and gravesoil chemistry in a cold (Dfa) climate. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 58(5), 1175–1182. 10.1111/1556-4029.12169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaelson, G. J. , & Ping, C. L. (2003). Soil organic carbon and CO2 respiration at subzero temperature in soils of Arctic Alaska. Journal of Geophysical Research, 108(D2). 10.1029/2001JD000920 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, K. R. , Hambly, A. , Singh, S. , Henderson, R. K. , Baker, A. , Stuetz, R. , & Khan, S. J. (2011). Organic matter fluorescence in municipal water recycling schemes: Toward a unified PARAFAC model. Environmental Science and Technology, 45(7), 2909–2916. 10.1021/es103015e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, K. R. , Stedmon, C. A. , Graeber, D. , & Bro, R. (2013). Fluorescence spectroscopy and multi‐way techniques. PARAFAC. Analytical Methods, 5(23), 6557–6566. 10.1039/C3AY41160E [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, K. R. , Stedmon, C. A. , Wenig, P. , & Bro, R. (2019). OpenFluor – An online spectral library of auto‐fluorescence by organic compounds in the environment. Analytical Methods, 6(3), 658–661. 10.1039/c3ay41935e [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, K. R. , Timko, S. A. , Gonsior, M. , Powers, L. C. , Wünsch, U. J. , & Stedmon, C. A. (2018). Photochemistry illuminates ubiquitous organic matter fluorescence spectra. Environmental Science and Technology, 52(19), 11243–11250. 10.1021/acs.est.8b02648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikrad, M. P. , Kerkhof, L. J. , & Häggblom, M. M. (2016). The subzero microbiome: Microbial activity in frozen and thawing soils. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 92(6), fiw081. 10.1093/femsec/fiw081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan, A.‐N. , Mead, R. J. , Maker, G. , Bringans, S. , Chapman, B. , & Speers, S. J. (2019). Examination of the temporal variation of peptide content in decomposition fluid under controlled conditions using pigs as human substitutes. Forensic Science International, 298(1), 161–168. 10.1016/j.forsciint.2019.02.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell, J. A. , Aiken, G. R. , Butler, K. D. , Guillemette, F. , Podgorski, D. C. , & Spencer, R. G. M. (2016). DOM composition and transformation in boreal forest soils: The effects of temperature and organic‐horizon decomposition state. JGR Biogeosciences, 121(10), 2727–2744. 10.1002/2016JG003431 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno, T. (2002). Fluorescence inner‐filtering correction for determining the humification index of dissolved organic matter. Environmental Science and Technology, 36(4), 742–746. 10.1021/es0155276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oksanen, J. , Simpson, G. L. , Blanchet, F. G. , Kindt, R. , Legendre, P. , Minchin, P. R. , et al. (2022). vegan: Community ecology package. R Package Version, 2, 2–6. Retrieved from https://CRAN.R‐project.org/package=vegan [Google Scholar]

- Parmenter, R. R. , & Macmahon, J. A. (2009). Carrion decomposition and nutrient cycling in a semiarid shrub–steppe ecosystem. Ecological Monographs, 79(4), 637–661. 10.1890/08-0972.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pechal, J. L. , Crippen, T. L. , Tarone, A. M. , Lewis, A. J. , Tomberlin, J. K. , & Benbow, M. E. (2013). Microbial community functional change during vertebrate carrion decomposition. PLoS One, 8(11), e79035. 10.1371/journal.pone.0079035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pecsi, E. , Forbes, S. , & Guillemette, F. (2024). Dissolved organic matter composition and bacterial metabolic responses in soils surrounding decomposing pig carcasses in a Canadian continental climate [Dataset]. Borealis, V3. 10.5683/SP3/DEH8FG [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peel, M. C. , Finlayson, B. L. , & McMahon, T. A. (2007). Updated world map of the Köppen‐Geiger climate classification. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 11(5), 1633–1644. 10.5194/hess-11-1633-2007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prescott, C. E. , & Vesterdal, L. (2021). Decomposition and transformations along the continuum from litter to soil organic matter in forest soils. Forest Ecology and Management, 498(1), 119522. 10.1016/j.foreco.2021.119522 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Putman, R. J. (1978). Patterns of carbon dioxide evolution from decaying carrion decomposition of small mammal carrion in temperate systems 1. Oikos, 31(1), 47–57. 10.2307/3543383 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team . (2022). R: A language and environment for statistical xomputing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Retrieved from https://www.R‐project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Sala, M. M. , Arrieta, J. M. , Boras, J. A. , Duarte, C. M. , & Vaqué, D. (2010). The impact of ice melting on bacterioplankton in the Arctic Ocean. Polar Biology, 33(12), 1683–1694. 10.1007/s00300-010-0808-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, G. (2012). plsdepot: Partial Least Squares (PLS) data analysis methods. R Package Version 0.2.0. Retrieved from https://CRAN.R‐project.org/package=plsdepot [Google Scholar]