Abstract

Introduction

While the adoption of strengths‐based approaches to supporting autistic adolescents is growing in popularity, the application of this approach to a digital arts mentoring program has yet to be explored. This study reports on the core elements contributing to the success of a community digital arts mentoring program for autistic adolescents from the mentors' perspective. This paper presents an in‐depth exploration of mentors' experiences, comprising a component of a broader line of research investigating a digital arts mentoring program for autistic adolescents emphasising positive youth development.

Methods

The digital arts mentoring program spanned 20 weeks across two Australian school terms and was attended by two groups of autistic adolescents (N = 18) aged between 11 and 17 years. A qualitative approach was utilised in exploring the perspective of their mentors (N = 6). Qualitative data were collected at the end of each school term for each group with the mentors using an interpretive phenomenological approach and Colaizzi's seven‐step analysis method. Thirteen individual interviews were conducted with six mentors.

Consumer and Community Involvement

This research was conducted with a disability arts provider to provide a digital arts mentoring program to autistic adolescents. The mentors employed have lived experience with disorders such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and anxiety.

Results

Five primary themes emerged from the data: positive connections, mentor knowledge and experience, mentoring approaches, autism education, program organisation, resources and environment. Subthemes underpinned the primary themes related to positive connections (three subthemes), mentoring approaches (four subthemes) and program organisation, resources and environment (three subthemes).

Conclusion

The findings suggest that prior experience, sufficient training, a supportive environment and a flexible and adaptable approach were essential for success. Understanding the core elements of a strengths‐based digital arts program in occupational therapy provides a comprehensive framework for utilising clients' inherent strengths and creativity as therapeutic tool, creating an empowering environment, fostering meaningful outcomes for clients.

Keywords: adolescents, autism spectrum disorder, digital arts, interests, mentors, strengths‐based program

Key Points for Occupational Therapy.

Mentoring is powerful in supporting autistic teenagers in learning about their skills and abilities.

Strengths‐based approaches build autistic youth's self‐esteem and sense of identity.

Strengths‐based approaches leverage clients' unique abilities, preferences and interests.

1. INTRODUCTION

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a complex neurological developmental disability characterised by a range of challenges in communication, emotional awareness, and social interaction, often accompanied by restricted, repetitive patterns of behaviour, activities or interests (American Psychiatric Association, 2000; Zeidan et al., 2022). These characteristics can be observed in individuals from infancy through to later stages of life, leading to significant challenges in functional domains where interpersonal interactions and engagement are required (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Current estimates suggest that globally approximately one in 100 individuals are impacted. Improved diagnostic approaches and greater societal awareness have likely contributed to the increasing prevalence (Zeidan et al., 2022). This significant increase in the number of individuals living with ASD underscores the urgency of understanding those approaches that best support autistic individuals (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2017; Zeidan et al., 2022). In accordance with the preference of the majority of autistic individuals and autism community, this paper uses identity‐first language, reflecting autism as an integral aspect of a person's identity (Autism CRC, 2020; Kenny et al., 2016).

Compared to their neurotypical peers, autistic adolescents are at greater risk for poor mental health outcomes including anxiety, loneliness, the experience of social exclusion, and less satisfying friendships, despite their desire for social connections (Sundberg, 2018). The core behaviours characterising ASD can significantly affect an individual's quality of life and daily functioning across the lifespan (Sundberg, 2018). Outcomes for autistic adults in major life areas in adulthood such as employment, community participation and independent living remain consistently poor (Howlin et al., 2004; Howlin & Magiati, 2017; Poon & Sidhu, 2017) and there is a great need for evidence‐based interventions supporting autistic adolescents as they move towards adulthood.

In the field of autism intervention, strategies primarily focus on addressing the social, communication and behavioural deficits associated with the diagnosis. However, despite these efforts, outcomes in adulthood including autistic individuals' quality of life remain poor (Jones et al., 2021; Will et al., 2018). In preference to adopting a deficit‐based approach which focuses on remediating impairments, recently, studies have emerged framed by a strengths‐based approach, aiming to enhance the outcomes of autistic individuals by focusing on individual strengths (Jones et al., 2021; Lee, Scott, et al., 2023).

The Department of Education and Early Childhood Development of Victoria (2012, p. 6) defines the strengths‐based approach as ‘an approach to people that views situations realistically and looks for opportunities to complement and support existing strengths and capacities as opposed to focusing on, and staying with, the problem or concern’. In the realm of occupational therapy, therapists focus on identifying their clients' strengths and positive attributes while addressing the problems within the framework of their existing strengths, skills and supports systems that can be leveraged to address the problems (Pulla, 2017).

Research has provided evaluations of strengths‐based programs that focused on interest‐based activities to promote socialisation, communication and relationship‐building within therapy and mentoring programs for autistic adolescents (Lee, Scott, et al., 2023; Stancliffe et al., 2010). Specifically, these programs target common strengths often associated with ASD, including attention to detail, mathematics, artistic skills and memory (de Schipper et al., 2016).

Creative art therapy with autistic individuals has been linked with improvements in flexible thinking, expressiveness and relaxation when communicating with others, all of which can be challenging for autistic individuals (Zeidan et al., 2022). Engaging in art‐based activities, such as drawing and painting provides opportunities for autistic individuals to express themselves in a safe space, indirectly improving their communication skills (Schweizer et al., 2019). The diverse materials and methods employed in art education and art therapy provide opportunities for exploring mediums that can potentially support autistic individuals in regulating their sensory processing and emotions (Martin, 2009; Schweizer et al., 2019). Further, many autistic individuals possess creative talents and artistic skills (de Schipper et al., 2016), which can be harnessed in arts‐based programs, establishing outlets for creativity and promoting positive behaviours (Schweizer et al., 2019).

Although programs adopting strengths‐based approaches in supporting autistic adolescents are gaining popularity, research investigating these programs remains limited. Prior to evaluating the efficacy of arts‐based programs for autistic adolescents in experimental designs, some understanding of the essential components of these programs is needed (Craig et al., 2008). Although a substantial body of research has investigated the elements contributing to the success of technology strengths‐based programs for autistic adolescents (Ashburner et al., 2017; Diener et al., 2016; Donahoo & Steele, 2013; Jones et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2020), limited research has examined on strengths‐based creative art programs (Müller et al., 2017). Further, previous research has highlighted the key role that mentors play in promoting the successful outcomes of strengths‐based programs for autistic adolescents and young adults (Jones et al., 2021; Thompson et al., 2018). Mentoring relationships can support social‐emotional development in autistic adolescents (Weiler et al., 2022). While this has been established in the context of technology‐focused programs (Ashburner et al., 2017; Donahoo & Steele, 2013; Jones et al., 2021), it is crucial to explore whether similar mentorship dynamics apply to strengths‐based creative art programs. The perspectives of art mentors are crucial in informing program design and implementation. They provide insights into the mentor‐mentee relationship, identify the needs of both mentors and autistic adolescents and highlight the challenges and success factors of the program. This knowledge is instrumental in shaping and improving strengths‐based art programs for autistic adolescents. Given this need the present study aimed to investigate the key elements of a digital arts mentoring program for autistic adolescents from the perspective of the mentors involved in delivering the program. This study constitutes a component of a broader line of research evaluating a digital arts program for autistic adolescents that harnesses the principles of positive youth development (Bowers et al., 2010) with autistic adolescents themselves, their parents and mentors. Positive youth development emphasises developing strengths for adolescents, providing opportunities and further support to build on their strengths (Bowers et al., 2010).

2. METHODS

2.1. Research design

An overarching qualitative research paradigm enabled the exploration of the mentor's experiences in supporting autistic adolescents participating in a digital arts program (Smith & Osborn, 2015). An interpretive phenomenological approach (IPA) was utilised, allowing insight and understanding into participants' experiences. Taking an inductive approach to analysing and interpreting individuals' experiences through a subjective lens (Smith & Osborn, 2015), IPA supports original interpretations of experiences, free from pre‐conceived ideas (Smith & Osborn, 2015). This approach provided opportunities for participants to express their views comprehensively, enabling a complete description of the research topic. Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee in Western Australia (HRE2017–0147).

2.2. The digital arts mentoring program

The digital arts mentoring program investigated in the present study was delivered to two groups of autistic adolescents for 20 weeks, over three 10‐week Australian school terms, (from October 2021 to June 2022) at DADAA, a Western Australian disability arts provider. Each group comprised 10 autistic adolescents participating in a weekly workshop on Saturday morning for 2 h and 30 min. This program was designed to engage autistic adolescents (aged 11 to 17 years) in creative art activities. The activities offered within the weekly workshops included paper‐based pencil and pen drawing, watercolour and ink, acrylic painting, collage, clay, printmaking, digital drawing and painting, animation on Procreate, green screen, sound sampling and iMovie production. The program was grounded in an artist‐led, strengths‐based approach, focusing on leveraging the adolescents' strengths, interests, preferences and skills. The program integrated activities aiming to foster social interaction and communication, including snack time during the weekly sessions and two to three excursions to art galleries. The art gallery excursions specifically aimed to promote meaningful aesthetic learning, by encouraging autistic adolescents to engage in discussions about the artists' work, materials and processes, with the goal of fostering in participants a sense of themselves as artists. At the end of each program, parents of mentees were invited to attend a ‘Celebration Event’. This event was held in the cinema room of DADAA and was an opportunity for the autistic adolescents to display their art and showcase their journey and efforts throughout their engagement in the program.

The weekly workshop was facilitated by four to five facilitators (see Table 1). In the presentation of data, pseudonyms are used to protect the anonymity of all participants. Prior to commencing the program mentors were provided with autism awareness training delivered by a clinical psychologist experienced in working with autistic adolescents, with the goal of developing their skills and knowledge in supporting autistic adolescents. This study was related to a broader research project that included participant observation as part of the study design, with research team members present at the weekly sessions.

TABLE 1.

Strengths‐based digital arts program groups.

| Program groups | Year and school term | Number of mentees enrolled in the program | Number of mentees withdrawing from the program | Reason for withdrawal | Number of mentors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A | 2021 Term 4 and 2022 Term 1, a total of 20 sessions | 10 | 0 | N/A |

Term 4: n = 5 Kelly, John, Anne, Melissa and Robert Term 1: n = 4, Kelly, John, Anne and Joanne |

| Group B |

2022 Terms 1 and 2, a total of 20 sessions |

9 | 1 | Unable to cope in a group | Terms 1 and 2: n = 4, Kelly, John, Anne and Joanne |

2.3. Participants

Mentors meeting the following inclusion criteria were invited to participate in the present study: (1) over the age of 18, (2) specific interest in digital art and teaching art skills, (3) previous experience in working with people with a disability and (4) employed by DADAA in delivering the specialist digital arts program evaluated in the present study. Six mentors, consisting of four females and two males, ranging in age from 23 to 49 years agreed to participate in the study. The mentors' average age was 32 years, and they brought a diverse range of experiences and expertise to the study. Among the mentors, four mentors were neurodivergent and four had attained undergraduate degrees, whereas two had completed postgraduate degrees, primarily specialising in education, media and communication, creative media and fine arts. This combination of educational backgrounds ensured that the mentors collectively held a broad knowledge and skills in artistic mediums. All mentors provided informed consent prior to any data collection.

2.4. Data collection

Data collection took the form of individual interviews with the mentors. Mentors were requested to attend an interview at the end of each 10‐week term, with the majority of mentors engaging in two interviews. Interviews followed a guide comprising semi‐structured questions designed to elicit the mentor's experience and views on factors contributing to the success of the program. Sample questions included: What was your overall mentoring experience? Tell us what worked for you in delivering the program. What was the overall effect of the program on mentors and mentees? Interviews lasted between 45 and 60 min and were recorded and transcribed using ‘Otter AI’ with transcripts reviewed against recordings, ensuring their accuracy. Transcriptions were then subsequently imported into NVivo data management software (Dhakal, 2022).

2.5. Data analysis

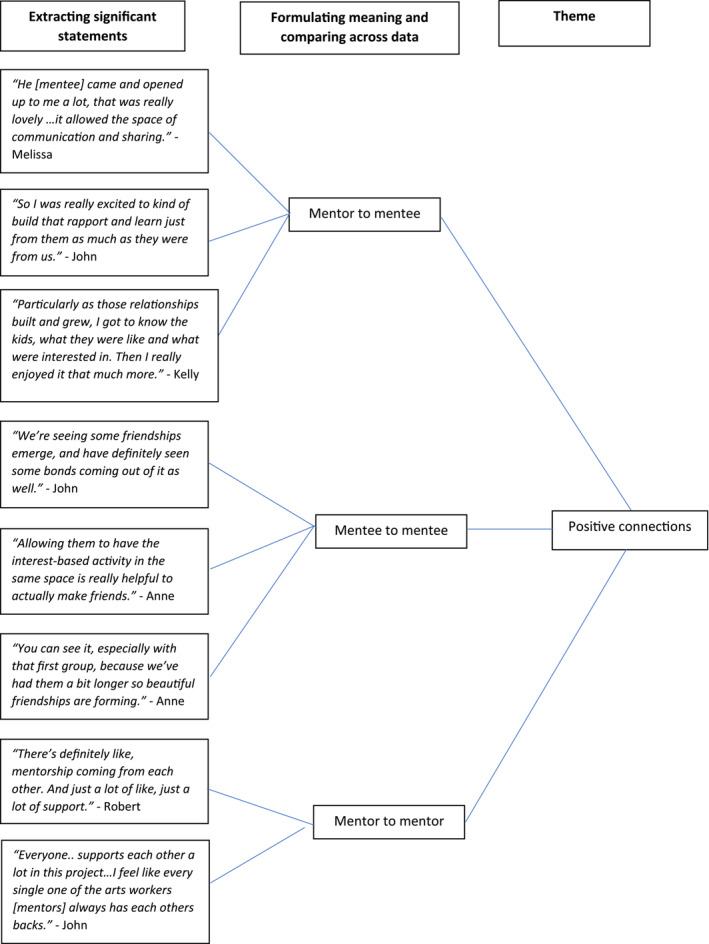

Analysis in IPA is considered inductive where codes were generated from the data without using a pre‐existing theory to explore in detail how participants are making sense of their personal experience. It is to understand the content and complexity of those meanings instead of measuring their frequency (Smith & Osborn, 2008). Central to the IPA is the six‐step approach to analysis: (1) reading and re‐reading, (2) initial noting, (3) developing emergent themes, (4) searching for connections across emergent themes, (5) moving to the next case and (6) looking for patterns across cases (Smith et al., 2009, pp. 82–107). However, rather than a prescriptive methodology, the analysis methodology is open to adaption to meet the purpose of the study (Bartoli, 2019; Smith & Osborn, 2008). In analysing the data of this study, the seven steps of Colaizzi's analysis method (Colaizzi, 1978), which aligns with the IPA approach was utilised in interpreting the meaning and experience of the mentors: (1) Each transcript was read individually by four authors (EC, A‐MJ, RK and TM) ensuring a deep understanding of the participants' stories; (2) significant statements were identified; (3) meaning was developed from significant statements; (4) reoccurring meanings from participants stories were compared and meanings were amalgamated into themes; (5) emergent themes were developed into an exhaustive description; (6) the exhaustive description was condensed to capture the essential aspects of the phenomenon; and (7) a summary of themes and subthemes were presented to each of the participants for member checking and confirmation of findings (Chan et al., 2013). Themes were documented and coded using NVivo reaching saturation (Dhakal, 2022). Figure 1 reflects an example of data coding following the process of Colaizzi's analysis method (Colaizzi, 1978). Confirmability was established through researchers (EC, A‐M J, RK and TM) independently gathering information and developing initial codes for every transcription, before analysing the data collaboratively to identify findings derived from the data (Krefting, 1991).

FIGURE 1.

Colaizzi's analysis theory for the overarching theme ‘positive connections’.

2.6. Trustworthiness

Trustworthiness and rigour of qualitative research are influenced by strategies employed in addressing the credibility, transferability, dependability, confirmability and reflexivity quality of the research (Krefting, 1991). In the present study credibility was supported by employing an interview guide, the process of investigator triangulation, whereby multiple researchers collected, coded and analysed data individually (Carter et al., 2014) within NVivo software (QSR International, 2018), which enabled communication between the researchers (Dhakal, 2022). Peer debriefing between the researchers further contributed to the dependability of the data. To facilitate trustworthiness, discussions around field note interpretations and review of interpretations regarding the data were conducted in fortnightly meetings in which a critical review was conducted (Norman & James, 2020). The research team also developed rapport with the mentors, by regularly attending the weekly session. Mentors were provided with a summary of the overarching themes and subthemes emerging from the preliminary data analysis for member checking.

2.7. Positionality

he researchers (the second, fourth, fifth, sixth, seventh and last authors) are occupational therapists with clinical experience. The first author has an educational background and the third author has a foundational background in psychology, adding diverse perspectives to the group. Further, the first, second, third and last authors have extensive research experience in autism, particularly in the domain of strengths‐based programs for autistic adolescents and young adults. The last and second authors played a pivotal role in securing funding by collaborating with a disability arts provider, DADAA, enabling the delivery of the community strengths‐based digital arts program tailored for autistic adolescents.

3. RESULTS

Data analysis revealed that the experience of mentoring autistic adolescents in a digital arts program could be described by five primary themes: positive connections; mentor knowledge and experience; autism education; mentoring approaches and program organisations; and resources and environment (see Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Themes and subthemes of essential factors for the digital arts program.

| Theme | Subtheme | Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Positive connections |

Mentor to mentee |

‘I feel like after those a couple of weeks, just sort of getting to know each other, and the artworkers [mentors] and myself getting to know each other. And, we started to feel like there was a bit more of a team forming and we had a better sense of attention span of the kids and how to engage with them’.—Kelly, Term 1 |

|

Mentor to mentee |

‘The first group… some beautiful friendships are forming. And, it's amazing to see the difference from that first day. So yeah, it's gorgeous’.—Anne, Term 1 |

|

|

Mentor to mentee |

‘I think I was very lucky. Well, we're all very lucky that we all kind of have each other's backs, and we're all supportive of each other’.—Joanna, Term 2 |

|

| Mentor knowledge and experience |

‘I felt really quite prepared, because I've done it before. And yeah, there was a lot of support and help with this project as well’.—Anne, Term 4 ‘I feel really satisfied that we've given, you know, we've thrown all our resources and all our knowledge and collective expertise at this’.—Kelly, Term 2 |

|

| Autism education |

‘I thought all of the preparation was really informative, not only for us as mentors, but for myself, and like, who I am in my neurodiversity. And I think it really informed ways to approach and be careful around the way we speak, or the way we collaborate’.—Melissa, Term 4 ‘I was actually pretty happy just with the training I received right at the start of the program. I'd not be adverse to having an extra training, because I always feel like it's good to have everything that I possibly can. Like I said, my skills are as solid as possible. But I certainly don't think that I would suffer at all from not having that extra little bit. I think that I definitely had what I needed to get through it. But yeah, wouldn't be adverse to the possibility of further training’.—John, Term 1 |

|

| Mentoring approaches | One‐on‐one mentoring |

‘It feels like it's really easy to establish that rapport when you're one‐on‐one because like you get to understand their creative processes … allows you to really understand like just how long they can kind of keep working on one activity before they really need a break… and what kind of things they like and what they're interested in’.—John, Term 4 |

|

Autonomous choices |

‘His [mentee] drawings were just so expressive and full of life. And I think he works really well [when he is] given like direction, but allowing him to, you know, follow direction, but in his own manner, and being allowed that time to really express himself’.—Joanna, Term 1 |

|

| Allowing time |

‘His drawings were just so expressive and full of life. And I think he works really well. Giving like direction, but allowing himself to, you know, follow direction, but in his own manner, and being allowed that time to really express themselves’.—Joanne, Term 1 |

|

| Adjusting mentoring style |

‘It's [autism] such a large spectrum, and everybody has their own things that they like or dislike, and it's just about learning about the individual and then tailoring the way you mentor for them specifically’.—Melissa, Term 4 |

|

| Program organisation, resources and environment | Program structure |

‘The structure that we went for, ended up working quite well, which was basically that first beginning half hour of the workshop where we're everyone's arriving and gathering together, and then we'd had that focus time to either do a demo or an activity or something. And then there would be options to continue that activity, or then spend the rest of the time working on their own ideas and having arts workers [mentors] float round to engage. Yeah, that worked quite well, I think’.—Kelly, Term 2 |

| Facilities and resources |

‘Having separate rooms, really works, having multiple sections to choose from, again, having multiple, like different seating arrangements, so you know, you can sit at a table or on the ground on a beanbag. And having snacks and drinks provided for the kids is really helpful. They get a sort of break room vibe, where they get to chat around the watercooler kind of thing. So, I think that really worked well. And just having access to heaps and heaps of materials that are just free for all ready to use’.—Anne, Term 1 ‘I definitely liked… one thing I did like about the project was having the walkthroughs and stuff for people, like they could view a walkthrough, record walkthrough, so they know what to expect. Because I know for a lot of people on the spectrum, it can be a lot of anxiety around the unknown. So, I suppose helping remove the unknown a little bit is really handy’.—Robert, Term 4 ‘Yeah absolutely. We have probably more than enough there. [Ann] loves opening up all the cupboards and seeing what he could explore with today and what he wanted to, he was really fascinated with charcoal. So, we worked mainly with charcoal. And luckily for us, there's a whole drawer full of charcoal. So, for [James], he never felt that he was limited or anything like that’.—Joanne, Term 2 |

|

| Environment |

‘I think it was inclusive, because we yeah, we let them do what was best for them’.—Anne, Term 1 ‘I wouldn't change a thing about it, it's just generally been a very safe, supportive and fun environment to work in’.—John, Term 1 ‘The information sessions we had before was super informative and amazing. And I really can't fault any of that. I felt really comfortable with the working environment that we worked with’.—Melissa, Term 4 |

3.1. Theme 1. Positive connections

Mentors expressed how engaging with autistic adolescents provided opportunities for socialising and developing friendships. Socialising occurred both among the autistic adolescents and between the autistic adolescents and mentors. Mentors felt they had a key role in encouraging social interaction within the group, seeing socialising as an important part of the program. Three subthemes were identified including mentor to mentee, mentee to mentee and mentor to mentor.

3.1.1. Mentor to mentee

The collaboration between mentors and mentees was essential in mentees developing confidence in their artistic skills. One of the mentors John reflected on his experience of working with one of the mentees:

So, there's definitely like an amazing change in his [mentee] confidence. And I think that it's part of that building that rapport with him that brought that out of him.

The program ‘set‐up’ of the DADAA's premises and the accessibility of equipment such as iPads and art supplies enabled the mentors to collaborate with the mentees on various art‐based activities. Mentors sharing their skills and interests with the mentees while working on projects resulted in natural pairings between mentors and mentees based on shared interests:

When it came to the mentoring, it was beneficial having that open discussion of what us as mentors are good at and allowing the participants to pick who they would kind of like to gravitate to working with. (Melissa)

Another mentor reflected having some background information about the autistic adolescents prior to the workshops helped with relationship‐building:

[Kelly] telling us something about the kids that are going to be coming in, the kids coming in, and then us making that connection, ‘Ahhh yes, that must be so and so that must be them’. You gotta keep all this information in mind, and then using that to kind of begin building that rapport as well. (John).

3.1.2. Mentee to mentee

Mentors described relationships forming between the autistic adolescents based on their shared interests in art, relationships that strengthened and grew across the 20 sessions of the program. Mentors encouraged the adolescents to share their artwork and interests with each other, providing opportunities for developing authentic peer relationships: ‘Sharing their artworks with each other was so amazing… they gave each other really nice feedback and advice, and would sometimes help each other out’ (Anne). Mentors highlighted the importance of the afternoon tea break in encouraging conversation and social interaction among the adolescents, ‘having the break time in the middle was quite a good time for people to mix and chat’ (Robert). John described how the relationship between adolescents developed as they became more confident and familiar with their peers over the course of the program:

I would say confidence is the biggest thing that I've seen growing in all of the participants [mentees], like… the fact that they're in a safe space with people that they've actually had a chance to get to know and they've worked with.

Anne described how the adolescents all sharing a common interest in art provided a basis for developing authentic friendships with their peers:

Allowing them to have the interest‐based activity in the same space is really helpful in actually making friends.

3.1.3. Mentor to mentor

Mentors observed a positive dynamic among them: ‘We try to make sure that we are available for each other and hearing each other out’ (Joanne), noticing that they had been working well together since the outset:

I feel like me, [Anne], [Joanne], and [Kelly] and [Lucy] as well. Yep. We all work really, really well together. And we've worked together before. [Joanne], I'm just meeting her this term, but she's like one of those people where you just feel like you've got an instant rapport with. So I feel like we all work quite well together. (John).

Further, mentors noted that their relationships with the other mentors grew over the course of the art program, providing opportunities to develop both their mentoring and artistic skills. John reflected on his experience working collaboratively with other mentors and expressed that in doing so, he felt he was able to be a role model to the mentees:

It's just a bouncing ball of ideas when somebody comes up with something. It continues to grow when more people [mentors] add to it. I think it's a really important thing to instil with people with autism that find it hard to communicate … that this is actually really beneficial to be able to share our ideas and collaborate with people in order to learn new skills, and that it will add to our own skill set.

3.2. Theme 2. Mentor knowledge and experience

Mentors recruited for the research study had varying levels of experience in working with people with disabilities, autistic adolescents and specific art skills.

Although mentors' previous levels of experience in mentoring differed, they all agreed that these experiences were important to their ability and confidence in working with the autistic adolescents. John described that the diverse backgrounds of the mentors are key in promoting the art program's successful outcomes: ‘We are all bringing, like unique sort of perspectives to it’. Another mentor, Robert, expressed concern that his lack of experience in working with autistic adolescents limited his understanding as to how much to challenge them:

I haven't worked with a lot of people of that [adolescent] age group. I suppose I had a little bit of anxiety centred around sort of how much do I push? How much don't I push? Just a little bit of uncertainty.

Anne reflected on her own personal experience of living with neurodiversity, which she felt helped her to effectively mentor and build rapport with the autistic adolescents:

It helps having a bit of experience… I've only got ADHD so I don't have experience with some of the autism traits, but… some of the traits are very similar… so yeah, I guess I just can understand their struggle a little bit… and also just, like, have some things in common.

Mentors' knowledge and experience grew throughout the program, by sharing tips, strategies and approaches with other mentors, and learning from their own practical experiences within the program: ‘I'm learning alongside them [mentees]. Where there is like learning partners almost. And I noticed that over time, I got more and more comfortable with that. And more and more able to like slip into that [mentor] role’. (John)

3.3. Theme 3. Autism education

All of the mentors commented that the autism awareness training was a key factor in building their understanding and confidence in mentoring autistic adolescents engaging in the digital art program. As Kelly explained: ‘I think that we had all the preparation that we could have possibly had [from the autism awareness training]’. Another mentor, Anne, valued both her prior experience and the autism awareness training in preparing her to be an effective mentor: ‘I felt really quite prepared again, because I've done it before, but also, you know, from the bit of extra training’. Similarly, another mentor John felt well prepared: ‘I definitely wasn't going in blind, like I had all the training and preparation I needed’. Melissa expressed that although she had previous experience in working with older autistic individuals, she had limited experience in working with autistic adolescents:

I was a little unsure to begin with, because the variety of people that I've worked with that are on the spectrum are older… So, I was thinking, am I prepared to work with autistic adolescents?

However, Melissa felt supported with the autism awareness training:

The information session [autism awareness training] we had before was super informative and amazing. And I really can't fault any of that. I really felt comfortable with the working environment.

3.4. Theme 4. Mentoring approaches

Mentors described the ongoing process of adapting their approach to align with the needs of the autistic adolescents, ensuring they were having a positive experience:

Recognising the uniqueness of each individual and then tailoring your teaching method to that person, rather than having the same kind of approach with everybody was effective. (Melissa)

Mentoring strategies included one‐on‐one mentoring, promoting autonomous choice‐making and allowing time for autistic adolescents to develop their artistic and interpersonal skills, adjusting mentoring style.

3.4.1. One‐on‐one mentoring

While mentors noted one‐on‐one mentoring was the most commonly implemented approach to mentoring, mentors noted that not all autistic adolescents wanted or responded well to one‐on‐one mentoring with some adolescents preferring to work independently with less support.

We would have moments of, you know, really good one‐to‐one chats. So that worked well… Because they didn't really need someone there the whole time. (Anne)

One‐on‐one mentoring worked towards building rapport between some mentors and their mentees, providing opportunities for collaboration on artistic methods.

The one‐on‐one time is, you know, definitely required. Even if it's just… maybe sitting in for 10 minutes with a person, and then… taking turns, there has to be that, for sure. (Kelly)

3.4.2. Autonomous choices

Allowing the autistic adolescents' autonomy in choosing their artistic projects and how they spent their time enabled the development of adolescents' artistic and social skills. This freedom of choice engaged the adolescents, encouraging them to express themselves through their art projects. Tapping into adolescents' special interests further engaged them in the sessions:

Engaging with special interests… It worked really well, in terms of, you know, outcomes, creative outcomes, artistic outcomes, and social outcomes. (Kelly)

It feels [like] you get more out of someone when you walk in their shoes a little bit and see what they're interested in, then push that. (Robert)

Another mentor shared his experience of inspiring and guiding the autistic adolescents by tapping their special interests:

Whenever I interacted with them, I was mostly there to inspire them because I'm a character designer. When I noticed that's something that they're really interested in, that was something I could help like, verbally with. (John)

3.4.3. Allowing time

Allowing for time and having a patient approach was described by mentors as key in mentoring the autistic adolescents:

I think something I've learned over a long time working at DADAA is to have a huge amount of patience. Yeah, letting someone sit in silence or waiting for them to work out what they're going to say. Huge amounts of patience and understanding, you know, really helps. (Anne)

John shared that the participating adolescents worked at their own pace across the program, and how patience was needed to support them in developing their artistic and social skills:

I think that all of them, when they were ready, would show interest and were inspired to try new things… It just took some of the adolescents a different amount of time than others.

Mentors reported that being patient also helped them in establishing rapport with the adolescents:

It was just giving the adolescents time to get used to us just as much as we needed to get used to them. (Robert)

3.4.4. Adjusting mentoring style

Mentors described tailoring their mentoring style to adolescents' individual needs across the program, describing their mentoring style as transitioning from a ‘teacher‐like’ style to collaborator and peer:

It was learning about what works for one doesn't work for another, and the individualism and uniqueness in all of their learning abilities, and the differing factors in that. (Melissa)

Mentors actively fostered an inclusive and non‐judgmental environment, allowing the participating adolescents to be themselves, and work in their own way:

We tried our best to be like, inclusive, and inviting kids to, you know, get help from us, but some of them were more keen to just be alone. And for them, that I guess, was inclusive. (Anne)

3.5. Theme 5. Program organisation, resources and environment

The significance of organisational factors, including program organisation, resources and setting was acknowledged as crucial in determining the program's success. This theme covers the subthemes of program delivery and structure, facilities and resources and environment.

3.5.1. Program delivery and structure

The program's delivery approach that centred around special interests contributed to positive outcomes: ‘Well, if we're talking about creative processes, that methodology we talked about, yeah, that engaging with special interests, then I think it worked. It worked really well, in terms of, you know, outcomes, creative outcomes, artistic outcomes, and social outcomes’. (Kelly)

Mentors commented that the overall structure of the program and the length of the weekly sessions supported both their roles as mentors and the mentees in engaging in the digital arts. John expressed that the sessions were ‘just the right amount of time to get enough work done, but not to burn [the adolescents] out’. The program was run with a different structure as in school with the opportunity to share their work showcasing their achievement and getting constructive feedback to refine their artistic skills:

And we keep reminding them that this is not school, you're not forced to do anything you don't want to do here. Like, there's no assignments, there's no marking, yeah, create whatever works you like. And they don't have to be perfect in any way. And we give them the opportunity to showcase their work [at the end of each term] … It's really nice, because everyone gives each other feedback, that's negative, positive. And then from that, it's like they're given the opportunity to develop their artistic practice’. (Joanne)

Mentors noted that the snack time was beneficial for socialisation:

We're [mentors] leading conversations with them, and we try and engage in like a little group conversation … It might take a little while for people to warm up. But after a while, you just get into a really nice conversation. After the break time you see everyone kind of warming up a little bit more with each other, as well. (Joanne)

This was supported by another mentor:

And having snacks and drinks provided for the kids is really helpful. They get a sort of break room vibe, where they get to chat around the watercooler kind of thing. So I think that really worked well. (Anne)

Overall, mentors expressed their appreciation for the program and the joy they felt seeing the positive progress experienced by the mentees, noting that ‘It would be so useful for them to continue on for more terms’. (Anne)

3.5.2. Facilities and resources

The mentors felt supported with the availability of ample resources:

I feel really well supported. I wouldn't have like any kind of worries coming in on Saturday, like concerns like whether there'll be enough materials or whether we'll have access to all the stuff that we need. (John)

Another mentor was impressed by the readily available resources and facilities at the premises:

DADAA is a great environment to be in. In itself. There's so many facilities available for us and especially on a Saturday we kind of have full rein of the whole area. So, the theatre, we have the digital room with the green screen we have the entire hall. James and I, we mainly use the mix media room, which is where all the paints and all the supplies are there. So it's very easy, accessible. And just a really motivating space for us to work in as well. (Joanne)

According to a mentor, the autistic adolescents were given the chance to make use of resources and facilities that were typically unavailable to them:

And I'm pretty happy with the outcome of the fact that I know that like a lot of the participants hadn't had access to facilities to be able to make this kind of art or work with people in the field of this kind of art. (Melissa)

3.5.3. Environment

Mentors highlighted the importance of a supportive and flexible environment in influencing the success of digital arts program:

Yeah, I think a big one would be providing spaces that have options. So, providing a quiet space, providing an option to have a bit of music or providing, say headphones, or like other aids to help people deal with certain sensory issues. Yeah. Definitely things like that. Making sure there's, you know, comfort, and different choices of seating and all of those things. But yeah, I think, definitely that like being able to have a private or quiet zone is very important. (Anne)

Mentors described the environment as safe and inclusive, as supporting the needs of the adolescents:

It definitely felt like a very safe and effective and supportive environment… and it is a conducive workspace. (John)

I think DADAA, the space at DADAA is really calm, and, like, I love working there, it's really accepting, loving, especially being someone with neurodiversity. I love working there for that reason, and that I'm accepted. And I feel everyone that works there is very accepting, because of our line of work. (Melissa)

Additional quotes for each theme and subthemes are presented in Table 2.

4. DISCUSSION

This paper explores the core elements of a strengths‐based digital arts mentoring program for autistic adolescents from the perspective of their mentors. Five key themes were identified: positive connections, mentor knowledge and experience, mentoring approaches, autism education, program organisation, resources and environment.

Collectively, the themes identified in the present study demonstrate the importance of mentors actively supporting autistic adolescents throughout the digital arts program, aiding in the development of their critical thinking, artistic and social skills aligned with their preferred interests. This support was fostered through collaboration and socialisation, particularly during activities such as working on their digital art projects or snack time, creating a social context that supported autistic adolescents' preferred interests and facilitated social interaction among peers (Smith et al., 2017). Mentors reported that towards the end of the term, autistic adolescents were observed to be ‘really opening up to each other and sharing ideas’. Although professionals serve a key role in organising and supporting these programs, mentors who share similar passion and interests with the autistic individuals in the program have a significant impact on their satisfaction, engagement levels and communication skills development. This study along with its previous literature, highlights the importance of having mentors who share similar passions and interests to mentees within strengths‐based programs (Jones et al., 2021). These findings are also consistent with its broader study involving adolescents and their parents who reported that shared interests contributed to building rapport and fostering friendship development between mentors and adolescents, creating a sense of belonging for the participating autistic adolescents, enabling them to feel part of the team and connect with like‐minded people (Lee, Milbourn, et al., 2023). Given the recent drive to improve outcomes in the major life areas of adulthood for autistic individuals, including employment, focusing on supporting autistic adolescents in developing their skills and abilities through sharing their interests could be key (Scott et al., 2017).

The program's success was underpinned by a culture of support and understanding of individual needs, fostering meaningful relationships between mentors and autistic adolescents, rather than relying on didactic teaching. Providing an appropriate level of support to people living with disabilities is key to promoting their successful participation in meaningful activities and social relationships (Bigby et al., 2019). Actively supporting autistic adolescents, rather than implementing a traditional didactic teaching approach, is a key component in creating effective outcomes in relationship development and social skills within strengths‐based programs. This seems particularly important given other research found that autistic adolescents find it challenging to respond to traditional teaching styles, which may result in disengagement, loss of interest and exclusion (Hasson et al., 2022).

The mentors described the importance of taking a flexible, participant‐led approach to working with the autistic adolescents, rather than following a pre‐determined program plan. Flexibility and adaptability were crucial in supporting the social and artistic development of autistic adolescents across the program (Stancliffe et al., 2010). This included being flexible in terms of the physical layout of the venue, adapting the structure of sessions and the overall program, and providing guidance and support for a variety of art forms. Being responsive to the sensory needs of adolescents was also important. Supporting sensory needs has been found to be beneficial in establishing positive relationships which in turn lead to outcomes such as employment, a sense of belonging, increased productivity and an improvement in social awareness (Scott et al., 2019).

Throughout the program, autistic adolescents were given the freedom to choose the activities they wanted to engage in. By remaining person‐centred and allowing autonomous choices, adolescents were engaged in developing their social and artistic skills. This finding is consistent with existing literature and a broader study with the participating adolescents and their parents in this program (Lee, Milbourn, et al., 2023), which has shown that allowing choice can decrease challenging behaviours in autistic adolescents, promoting their engagement and well‐being (Diener et al., 2016; Jones et al., 2021; Milbourn et al., 2020). Further, mentors in the present study recognised their need to be patient allowing authentic relationships to develop over time, positively impacting the autistic adolescents' social development (Nora & Crisp, 2007).

In the present study, as with previous research, attending autism awareness training was identified by the mentors as a key factor in supporting their mentoring of autistic adolescents (Hamilton et al., 2016). While those who had previous practical experience with mentoring thought these experiences were important in enabling their mentoring, those new to mentoring felt they were able to develop their own unique skill set and mentoring style across the duration of the program. This finding aligns with previous research highlighting the importance of on‐the‐job training in effectively supporting the development of mentors' knowledge, confidence and skills in their role (Naweed & Ambrosetti, 2015).

Mentors shared the value of having access to resources and facilities that assisted in delivering the sessions each week. Creating a supportive physical, social and cultural environment is essential in enabling the success of arts programs for autistic adolescents. The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) framework recognises an individual's functioning and disability are influenced by various contextual factors including environmental factors (Bölte et al., 2014). Environmental factors play a key role in supporting the functioning of autistic individuals, in helping them to manage their sensory needs, promoting independence (Bölte et al., 2019; Lowe et al., 2014) and quality of life outcomes (Nora & Crisp, 2007). This is likely particularly important in designing programs such as the one described in the present study, where inattention to environmental factors detracts from the inclusivity of the environment (Krieger et al., 2018). Creating a supportive cultural environment where individuals feel safe, comfortable, and able to express themselves is a key element for a strengths‐based program. The findings of this study, along with emerging literature, suggest that mentors can help achieve this by building rapport with the mentees by finding common interests, being patient and allowing time for them throughout all stages of the program (Jones et al., 2021; Lee, Milbourn, et al., 2023).

4.1. Implications

With the high prevalence and diagnostic rate of autism (Özerk, 2016), there is a growing opportunity for occupational therapists to develop programs focusing on providing mentoring opportunities for autistic children and adolescents. Mentors are a critical environmental factor in enabling the success of strengths‐based art programs with autistic teenagers. This study highlighted the importance of mentors adopting a flexible and adaptable mentoring style, tailored towards the needs and preferences of each mentee. Our findings also emphasise the importance of mentors adopting a person‐centred approach, while considering the broader social and sensory environment, in optimising autistic teens' engagement in strengths‐based arts programs. The key elements contributing to the effectiveness and success of a strengths‐based digital arts mentoring program, as perceived by the mentors in the study, can serve as a guide for occupational therapists in fostering a positive, client‐centred therapeutic environment that enhances engagement, promotes self‐efficacy and meaningful outcomes and engages autistic teenagers. Our findings also have significant implications for organisational change and future research aimed at strengths‐based art programs for autistic adolescents.

4.2. Limitations and future research

Several limitations were identified in this study. Firstly, it is important to note that the goal of the study was not to identify generalisable findings but to gain insight and understanding into the perspectives of a specific population (Liamputtong, 2012). Further research with a larger sample size is needed to validate and extend the results (Liamputtong, 2012). As with any qualitative study, the findings are subject to response bias as mentors may have given answers they believed were desirable to the interviewers. However, efforts were made to mitigate this bias by encouraging the mentors to express all aspects of their experience, whether positive, negative or neutral. Another limitation is that the digital arts program was delivered during Western Australia's COVID‐19 outbreak, which led to varying attendance rates for the participants due to lockdowns, essential quarantines and personal preferences for attending group gatherings. This may have influenced the mentors' ability to provide sufficient amounts of support and impacted their overall experience of the program. It is also important to consider that varying levels of mentor absences may have further compounded this issue. Finally, researchers were present during some of the sessions, which may have influenced the participants' behaviour and responses.

5. CONCLUSION

Mentors involved in the strengths‐based digital arts program highlighted the essential elements through their experience in mentoring autistic adolescents. This study contributes to understanding strengths‐based approaches in autism by demonstrating that focusing on leveraging autistic adolescents' interests and strengths, rather than remediating their deficits can promote positive outcomes. Our research findings suggest that mentors with previous experience and adequate training are key elements. Further, their awareness of factors promoting a supportive environment coupled with a flexible approach plays a crucial role. The program's success is further enhanced by a well‐structured and organised program in a safe and resourceful environment. These elements should be considered when planning future strengths‐based arts programs, as well as in workplaces and secondary education institutions catering to autistic adolescents. Understanding the core elements of a strengths‐based digital arts program‐ in occupational therapy provides a comprehensive framework for leveraging each client's inherent strengths and creativity as a therapeutic tool, creating an empowering environment and fostering meaningful outcomes for clients.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

The first author participated in the study design, coordinated data collection, interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. The second and third authors contributed to the study design, data collection and draft of the manuscript. The fourth, fifth, sixth and seventh authors contributed to the study design, data collection, data analysis and draft of the manuscript. The last author is the project leader who sourced the funding and contributed to the study design, data collection, interpretation of the data, coordination of research partners and the draft of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was funded by the Department of Education, Western Australia, and the Ian Potter Foundation (Grant No. 31110575). The authors would like to thank Ricky Arnold, Lyndsay Humphries and Connla Kerr from DADAA, Lilly Blue from the Art Gallery of Western Australia and Jane King from John Curtin Gallery for the successful delivery of this program. The authors were particularly grateful to the study participants who gave their time and shared their experiences with them.

Lee, E. A. L. , Milbourn, B. , Afsharnejad, B. , Chitty, E. , Jannings, A.‐M. , Kealy, R. , McWhirter, T. , & Girdler, S. (2024). ‘We are all bringing, like a unique sort of perspective’: The core elements of a strengths‐based digital arts mentoring program for autistic adolescents from the perspective of their mentors. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 71(6), 998–1014. 10.1111/1440-1630.12980

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research data are not shared.

REFERENCES

- American Psychiatric Association . (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th, Text Revision ed.). American Psychiatric Press Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner, J. K. , Bobir, N. I. , & van Dooren, K. (2017). Evaluation of an innovative interest‐based post‐school transition programme for young people with autism spectrum disorder. International Journal of Disability Development and Education, 65(3), 262–285. 10.1080/1034912x.2017.1403012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . (2017). Autism in Australia. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/disability/autism-in-australia

- Autism CRC. (2020). Language choices around autism and individuals on the autism spectrum. Retrieved January 17, 2024, from https://www.autismcrc.com.au/language-choice

- Bartoli, A. (2019). Every picture tells a story: Combining interpretative phenomenological analysis with visual research. Qualitative Social Work, 19(5–6), 1007–1021. 10.1177/1473325019858664 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bigby, C. , Bould, E. , & Beadle‐Brown, J. (2019). Implementation of active support over time in Australia. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 44(2), 161–173. 10.3109/13668250.2017.1353681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bölte, S. , de Schipper, E. , Holtmann, M. , Karande, S. , de Vries, P. J. , Selb, M. , & Tannock, R. (2014). Development of ICF core sets to standardize assessment of functioning and impairment in ADHD: The path ahead. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 23(12), 1139–1148. 10.1007/s00787-013-0496-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bölte, S. , Mahdi, S. , de Vries, P. J. , Granlund, M. , Robison, J. E. , Shulman, C. , Swedo, S. , Tonge, B. , Wong, V. , Zwaigenbaum, L. , Segerer, W. , & Selb, M. (2019). The Gestalt of functioning in autism spectrum disorder: Results of the international conference to develop final consensus International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health core sets. Autism: the International Journal of Research and Practice, 23(2), 449–467. 10.1177/1362361318755522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers, E. P. , Li, Y. , Kiely, M. K. , Brittain, A. , Lerner, J. V. , & Lerner, R. M. (2010). The five Cs model of positive youth development: A longitudinal analysis of confirmatory factor structure and measurement invariance. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(7), 720–735. 10.1007/s10964-010-9530-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter, N. , Bryant‐Lukosius, D. , Dicenso, A. , Blythe, J. , & Neville, A. J. (2014). The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncology Nursing Forum, 41(5), 545–547. 10.1188/14.ONF.545-547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan, Z. C. Y. , Fung, Y.‐L. , & Chien, W.‐T. (2013). Bracketing in phenomenology: Only undertaken in the data collection and analysis process? Qualitative Report, 18(30), 1. [Google Scholar]

- Colaizzi, P. F. (1978). Psychological research as the phenomenologist views it. In Vale R. S. & King M. (Eds.), Existential‐phenomenological alternatives for psychology. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, P. , Dieppe, P. , Macintyre, S. , Mitchie, S. , Nazareth, I. , & Petticrew, M. (2008). Developing and evaluating complex interventions: The new Medical Research Council guidance. British Medical Journal, 337(a1655). 10.1136/bmj.a1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Schipper, E. , Mahdi, S. , de Vries, P. , Granlund, M. , Holtmann, M. , Karande, S. , Almodayfer, O. , Shulman, C. , Tonge, B. , Wong, V. V. , Zwaigenbaum, L. , & Bölte, S. (2016). Functioning and disability in autism spectrum disorder: A worldwide survey of experts. Autism Research, 9(9), 959–969. 10.1002/aur.1592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhakal, K. (2022). NVivo. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 110(2), 270–272. 10.5195/jmla.2022.1271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener, M. L. , Wright, C. A. , Dunn, L. , Wright, S. D. , Anderson, L. L. , & Smith, K. N. (2016). A creative 3D design programme: Building on interests and social engagement for students with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). International Journal of Disability, Development, and Education, 63(2), 181–200. 10.1080/1034912X.2015.1053436 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Donahoo, D. , & Steele, E. (2013). Evaluating the lab: A technology club for young people with Asperger's syndrome. Young and Well Cooperative Research Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, J. , Stevens, G. , & Girdler, S. (2016). Becoming a mentor: The impact of training and the experience of mentoring university students on the autism spectrum. PLoS ONE, 11(4), e0153204. 10.1371/journal.pone.0153204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasson, L. , Keville, S. , Gallagher, J. , Onagbesan, D. , & Ludlow, A. K. (2022). Inclusivity in education for autism spectrum disorders: Experiences of support from the perspective of parent/carers, school teaching staff and young people on the autism spectrum. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 70(2), 201–212. 10.1080/20473869.2022.2070418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlin, P. , Goode, S. , Hutton, J. , & Rutter, M. (2004). Adult outcome for children with autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45(2), 212–229. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00215.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlin, P. , & Magiati, I. (2017). Autism spectrum disorder: Outcomes in adulthood. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 30, 69–76. 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M. , Falkmer, M. , Milbourn, B. , Tan, T. , Bölte, S. , & Girdler, S. (2021). Identifying the essential components of strength‐based technology clubs for adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 24(5), 323–336. 10.1080/17518423.2021.1886192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny, L. , Hattersley, C. , Molins, B. , Buckley, C. , Povey, C. , & Pellicano, E. (2016). Which terms should be used to describe autism? Perspectives from the UK autism community. Autism, 20(4), 442–462. 10.1177/1362361315588200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krefting, L. (1991). Rigor in qualitative research: The assessment of trustworthiness. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 45(3), 214–222. 10.5014/ajot.45.3.214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger, B. , Piskur, B. , Schulze, C. , Jakobs, U. , Beurskens, A. , & Moser, A. (2018). Supporting and hindering environments for participation of adolescents diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder: A scoping review. PLoS ONE, 13(8), e0202071. 10.1371/journal.pone.0202071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E. A. L. , Black, M. H. , Falkmer, M. , Tan, T. , Sheehy, L. , Bölte, S. , & Girdler, S. (2020). “We can see a bright future”: Parents' perceptions of the outcomes of participating in a strengths‐based program for adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(9), 3179–3194. 10.1007/s10803-020-04411-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E. A. L. , Milbourn, B. , Afsharnejad, B. , Gizzi, C. , Marinovich, A. , Milne, M. , Zimmerman, L. , & Girdler, S. (2023, 6–7 December). Unveiling the essential components: A realist evaluation of a digital art multimedia program for autistic adolescents. Australasian Society for Autism Research (ASfAR) conference. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E. A. L. , Scott, M. , Black, M. H. , D'Arcy, E. , Tan, T. , Sheehy, L. , Bölte, S. , & Girdler, S. (2023). “He sees his autism as a strength, not a deficit now”: A repeated cross‐sectional study investigating the impact of strengths‐based programs on autistic adolescents. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 1‐16, 1656–1671. 10.1007/s10803-022-05881-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liamputtong, P. (2012). Qualitative research methods (4th ed.). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, C. , Gaudion, K. , McGinley, C. , & Kew, A. (2014). Designing living environments with adults with autism. Tizard Learning Disability Review, 19(2), 63–72. 10.1108/TLDR-01-2013-0002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, N. (2009). Art as an early intervention tool for children with autism. Jessica Kingsley. [Google Scholar]

- Milbourn, B. , Mahoney, N. , Trimboli, C. , Hoey, C. , Cordier, R. , Buchanan, A. , & Wilson, N. J. (2020). “Just one of the guys” An application of the occupational wellbeing framework to graduates of a men's shed program for young unemployed adult males with intellectual disability. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 67(2), 121–130. 10.1111/1440-1630.12630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller, E. , Nutting, D. , & Keddell, K. (2017). Understanding ArtAbility: Using qualitative methods to assess the impact of a multi‐genre arts education program on middle‐school students with autism and their neurotypical teen mentors. Youth Theatre Journal, 31(1), 48–74. 10.1080/08929092.2016.1225612 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Naweed, A. , & Ambrosetti, A. (2015). Mentoring in the rail context: The influence of training, style, and practice. The Journal of Workplace Learning, 27(1), 3–18. 10.1108/JWL-11-2013-0098 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nora, A. , & Crisp, G. (2007). Mentoring students: Conceptualizing and validating the multi‐dimensions of a support system. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 9(3), 337–356. 10.2190/CS.9.3.e [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Norman, A. S. , & James, R. K. (2020). Expanding approaches for research: Understanding and using trustworthiness in qualitative research. Journal of Developmental Education, 44(1), 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- Özerk, K. (2016). The issue of prevalence of autism/ASD. International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 9(2), 263–306. [Google Scholar]

- Poon, K. K. , & Sidhu, D. J. K. (2017). Adults with autism spectrum disorders: A review of outcomes, social attainment, and interventions. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 30(2), 77–84. 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000306 ‐ PMID: 28009723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulla, V. (2017). Strengths‐based approach in social work: A distinct ethical advantage. International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change, 3(2), 97–114. [Google Scholar]

- QSR International . (2018). NVivo qualitative data analysis software, version 12. QSR International Pty Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer, C. , Knorth, E. J. , van Yperen, T. A. , & Spreen, M. (2019). Consensus‐based typical elements of art therapy with children with autism spectrum disorders. International Journal of Art Therapy, 24(4), 181–191. 10.1080/17454832.2019.1632364 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scott, M. , Jacob, A. , Hendrie, D. , Parsons, R. , Girdler, S. , Falkmer, T. , & Falkmer, M. (2017). Employers' perception of the costs and the benefits of hiring individuals with autism spectrum disorder in open employment in Australia. PLoS ONE, 12(5), e0177607. 10.1371/journal.pone.0177607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott, M. , Milbourn, B. , Falkmer, M. , Black, M. , Bӧlte, S. , Halladay, A. , Lerner, M. , Taylor, J. L. , & Girdler, S. (2019). Factors impacting employment for people with autism spectrum disorder: A scoping review. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 23(4), 869–901. 10.1177/1362361318787789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A. , Prendeville, P. , & Kinsella, W. (2017). Using preferred interests to model social skills in a peer‐mentored environment for students with special educational needs. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 22(8), 921–935. 10.1080/13603116.2017.1412516 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J. A. , Flowers, P. , & Larkin, M. (2009). Interpretative phenomenological analysis: Theory, method and research. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J. A. , & Osborn, M. (2008). Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In Smith J. A. (Ed.), Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods (2nd ed., pp. 53–80). Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J. A. , & Osborn, M. (2015). Interpretative phenomenological analysis as a useful methodology for research on the lived experience of pain. British Journal of Pain, 9(1), 41–42. 10.1177/2049463714541642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stancliffe, R. J. , McVilly, K. R. , Radler, G. , Mountford, L. , & Tomaszewski, P. (2010). Active support, participation and depression. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 23(4), 312–321. 10.1111/j.1468-3148.2009.00535.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg, M. (2018). Online gaming, loneliness and friendships among adolescents and adults with ASD. Computers in Human Behavior, 79, 105–110. 10.1016/j.chb.2017.10.020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The Department of Education and Early Childhood Development . (2012). Strength‐based approach: A guide to writing transition learning and development statements. The Communication Division for Early Childhood Strategy Division. Department of Education and Early Childhood Development. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, C. , Falkmer, T. , Evans, K. , Bölte, S. , & Girdler, S. (2018). A realist evaluation of peer mentoring support for university students with autism. British Journal of Special Education, 45, 412–434. 10.1111/1467-8578.12241 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weiler, L. M. , Goerdt, A. K. , Kremer, K. B. , Goldberg, E. , & Hudock, R. L. (2022). Social validity and preliminary outcomes of a mentoring intervention for adolescents and adults with autism. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 37(4), 215–226. 10.1177/10883576211073687 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Will, M. N. , Currans, K. , Smith, J. , Weber, S. , Duncan, A. , Burton, J. , Kroeger‐Geoppinger, K. , Miller, V. , Stone, M. , Mays, L. , Luebrecht, A. , Heeman, A. , Erickson, C. , & Anixt, J. (2018). Evidenced‐based interventions for children with autism spectrum disorder. Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care, 48(10), 234–249. 10.1016/j.cppeds.2018.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeidan, J. , Fombonne, E. , Scorah, J. , Ibrahim, A. , Durkin, M. S. , Saxena, S. , Yusuf, A. , Shih, A. , & Elsabbagh, M. (2022). Global prevalence of autism: A systematic review update. Autism Research, 15(5), 778–790. 10.1002/aur.2696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Research data are not shared.