Abstract

In previous cross-sectional studies, we demonstrated that, in most patients with chronic hepatitis C, the composition and complexity of the circulating hepatitis C virus (HCV) population do not coincide with those of the virus replicating in the liver. In the subgroup of patients with similar complexities in both compartments, the ratio of quasispecies complexity in the liver to that in serum (liver/serum complexity ratio) of paired samples correlated with disease stage. In the present study we investigated the dynamic behavior of viral population parameters in consecutive paired liver and serum samples, obtained 3 to 6 years apart, from four chronic hepatitis C patients with persistently normal transaminases and stable liver histology. We sequenced 359 clones of a genomic fragment encompassing the E2(p7)-NS2 junction, in two consecutive liver-serum sample pairs from the four patients and in four intermediate serum samples from one of the patients. The results show that the liver/serum complexity ratio is not stable but rather fluctuates widely over time. Hence, the liver/serum complexity ratio does not identify a particular group of patients but a particular state of the infecting quasispecies. Phylogenetic analysis and signature mutation patterns showed that virtually all circulating sequences originated from sequences present in the liver specimens. The overall behavior of the circulating viral quasispecies appears to originate from changes in the relative replication kinetics of the large mutant spectrum present in the infected liver.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is one of the leading causes of chronic liver disease worldwide (22). The quasispecies nature of the single-stranded RNA genome of HCV is thought to play a central role in maintaining and modulating viral replication (10, 29). In general, the natural history of HCV infection does not follow a defined pattern, but the rates of progression of the disease (from minimal changes of the liver to cirrhosis and hepatocarcinoma) vary greatly in different individuals (22). The cytopathic potential of the virus and the characteristics of the host's immune response have both been postulated to explain the observed differences in disease progression (6, 17, 18, 45).

In the absence of an appropriate animal model or culture system and in the context of the extreme heterogeneity of HCV, it has not been possible to associate particular sequences with distinct cytopathic potential. Similarly, attempts to correlate the process of quasispecies diversification with disease progression have yielded controversial results. While in cross-sectional studies some authors found a correlation between quasispecies complexity and extent of liver damage (20, 20, 21, 25, 48), others did not (19, 27, 33, 41). In longitudinal studies, the nucleotide complexity of the hypervariable domain of the HCV E2 region (HVR1) did not increase cumulatively over time but fluctuated in consecutive serum samples (2). Similarly, at more conserved regions of the genome, an oscillatory pattern of quasispecies complexity over time has been observed in long-term studies with frequent serum sampling (7). The factors that drive these fluctuations and their relative contributions are not defined, and, to further complicate the interpretation of the biological meaning of circulating quasispecies complexity, it has been proven that within an infected patient the composition of the circulating viral population does not necessarily reflect that of the hepatic population (4, 15, 28, 34, 38).

Recently, we observed a significant correlation between quasispecies complexity at the amino acid level, in both serum and liver quasispecies, and the extent of liver fibrosis, albeit only in those patients with a similar levels of complexity in both compartments (5). It is currently unknown whether the ratio of quasispecies complexity in the liver to that in serum (liver/serum complexity ratio) is a stable parameter, so that patients may be characterized by their ratios, or if it fluctuates over time.

We have investigated the behavior of viral population parameters over time in consecutive liver biopsy and serum samples obtained from four patients with nonprogressive chronic hepatitis C.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viral isolates.

HCV RNA was isolated from consecutive paired serum and liver biopsy samples obtained from four HCV-infected patients (A to D) at intervals of 3 to 6 years (Table 1). In one of the patients (patient A), four additional serum samples obtained during the 3 years between the biopsies were also studied. All patients had persistently normal alanine transaminase (ALT) levels and histologically nonprogressive liver disease (Table 1). All patients were infected with HCV genotype 1b, were negative for other hepatitis viruses and human immunodeficiency virus, and had not been treated with antiviral therapy. Informed consent was obtained before they underwent liver biopsies. In all cases blood was drawn in Vacutainer tubes and centrifuged within 2 h and the serum was stored at −80°C. Three-millimeter-long fragments of liver biopsy samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen.

TABLE 1.

Demographic, biochemical, and clinical parameters of four female HCV-positive patients

| Patient | Agea (yr) | Mean ALT ± SD | Sample date | Necroinflammation score | Fibrosisb score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 24 | 21 ± 5 | 1995 | 3 | 2 |

| 1998 | 2 | 2 | |||

| B | 19 | 30 ± 4 | 1995 | 2 | 0 |

| 2000 | 5 | 1 | |||

| C | 61 | 34 ± 5 | 1995 | 7 | 3 |

| 2000 | 10 | 2 | |||

| D | 62 | 34 ± 7 | 1994 | 6 | 3 |

| 2000 | 6 | 3 |

Age at entry.

The degree of liver damage was semiquantified according to the scoring system of Ishak et al. (23).

RNA extraction, reverse transcription-PCR, cloning, and sequencing.

Viral RNA was extracted from both serum (140-μl) and liver (0.05-g) samples using QIAamp viral RNA binding columns (Qiagen). Isolated HCV RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA with a genotype 1b-specific primer from the E2(p7)-NS2 region (MJJ3, 5′-CTCGAGCGTTGAGGGGGG-3′, at positions 2925 to 2942). Nested PCR was performed with specific oligonucleotides to amplify a 212-bp fragment (outer set, MJJ3 and MJJ4 [5′-TGTGCCTGCTTGTGGATG-3′, at positions 2534 to 2551]; inner set, MJJ5 [5′-CTAGAATTCAAAAATATTGTAACCACCA-3′, at positions 2870 to 2888] and MJJ6 [5′-ACAGGATCCAGTCCTTCCTTGTGTTCTTCT-3′, at positions 2639 to 2657]). Amplified products were purified with the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen) and cloned in Escherichia coli DH5α. Individual clones were sequenced by the dideoxy chain terminator method using the DNA dRhodamine sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems) and the ABI Prism 310 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems).

Viral RNA quantitation at E2(p7)-NS2.

To ensure that the number of template RNA molecules that enter the amplification reaction did not limit the level of resolution of the quasispecies analysis, we quantified the HCV RNA in the E2(p7)-NS2 region (the locus used for the quasispecies analysis) in at least one liver-serum sample pair from three of the patients, as already described (30). Specific oligonucleotides and the fluorogenic probe for genotype 1b were used (sense primer: C-2743, 5′-AGCGTTACCACCACGGG-3′, at positions 2743 to 2759; antisense primer: CR-2799, 5′-CCTCCGCACGATGCA-3′, at positions 2799 to 2785; probe: C-FT-2782, 5′-CATCTCCCGGTCCATGGCGTA-3′, at positions 2762 to 2782).

An HCV RNA standard used as reference for quantitation, representing the E2(p7)-NS2 region (at positions 2639 to 2888), was synthesized in vitro and purified by CF11 cellulose chromatography and polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, in accordance with the protocol published by Martell et al. (30). Transcripts were quantitated by isotopic tracing (24).

HCV quasispecies parameters.

Complexity of the quasispecies was estimated in all tissue and serum samples according to two parameters: mutation frequency (Mf) and Shannon entropy (S; frequencies of different sequences). Mf was calculated as the total number of mutations (nucleotide or amino acid) relative to the consensus sequence of each sample divided by the total number of nucleotides or amino acids sequenced; heterogeneity of the quasispecies increases as Mf increases (8). Shannon entropy has been defined in terms of the probabilities of the different sequences or clusters of sequences than can be present at a given time point (40, 46). This measure was calculated as S = −Σi(piln pi), where pi is the frequency of each sequence in the viral quasispecies. The resulting number was normalized as a function of the number of clones analyzed, thus allowing comparison of complexities among different isolates. The normalized entropy, Sn, was calculated as Sn = S/ln N, where N is the total number of sequences analyzed. Sn varies from 0 (no diversity) to 1 (maximum diversity) (40). Intrasample genetic distances were calculated by the Kimura two-parameter modification method. To track the evolution of particular sequences over time, neighbor-joining phylogenetic trees were constructed with Phylip, version 3.572c (Phylogeny Inference Package [16]).

Quantitation of nucleotide misincorporation with Taq Gold DNA polymerase.

To ensure that the observed heterogeneity was not due to nucleotide misincorporations introduced by the Taq Gold DNA polymerase (Applied Biosystems), one of the E2(p7)-NS2 clones of known sequence was amplified by PCR and subcloned. Among 47 such clones (totaling 9,964 nucleotides), only two nucleotide changes were detected in one of the clones. This low level of background noise coincides with our previous estimate of the misincorporation rate of Taq DNA polymerase (Perkin-Elmer) (one nucleotide change in 5,451 bases sequenced) (29) and confirms that most of the observed heterogeneity was independent of artifacts during the amplification procedure.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The GenBank and EMBL database accession numbers for the rest of sequences presented in this article are Z76958 through Z76966, Z77037 through Z77046, Z76944 through Z76957, Z77047 through Z77060, Y07774, AJ247670 through AJ247676, AJ247783 through AJ247792, AJ247899 through AJ247905, AJ248003 through AJ248012, AJ248103 through AJ248125, AJ391365 through AJ391490, and AJ303205 through AJ303331.

RESULTS

On average, 19 sequences (range: 7 to 24) for each sample were obtained (Table 2). We estimated the mutation frequency, normalized Shannon entropy, and genetic distance at both the nucleotide and amino acid levels in all serum and liver samples analyzed.

TABLE 2.

Sequence complexity at the amino acid level of the E2(p7)-NS2 genomic region in the liver and serum quasispecies of four chronic hepatitis patients

| Patient | Date (day.mo.yr) | Sample | Sample source | No. of clones sequenceda | Quasispecies complexity

|

% Synonymous mutations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mf | S | Genetic distance | ||||||

| A | 28.1.95 | L0 | Liver | 24 | 1/98 | 0.6 | 0.03 ± 0.3 | 66 |

| S0 | Serum | 24 | 1/176 | 0.36 | 0.01 ± 0.05 | 25 | ||

| 4.12.97 | L5 | Liver | 20 | 1/700 | 0.13 | 0.003 ± 0.007 | 50 | |

| S5 | Serum | 23 | 1/161 | 0.54 | 0.01 ± 0.03 | 64 | ||

| B | 5.6.95 | L0 | Liver | 7 | 1/560 | 0.6 | 0.004 ± 0.001 | 83 |

| S0 | Serum | 8 | 1/490 | 0.4 | 0.004 ± 0.001 | 67 | ||

| 9.3.00 | L1 | Liver | 23 | 1/544 | 0.11 | 0.004 ± 0.02 | 73 | |

| S1 | Serum | 20 | 1/710 | 0.13 | 0.003 ± 0.007 | 80 | ||

| C | 25.10.95 | L0 | Liver | 10 | 1/700 | 0.1 | 0.003 ± 0.002 | 89 |

| S0 | Serum | 12 | 1/168 | 0.2 | 0.02 ± 0.04 | 76 | ||

| 3.3.00 | L1 | Liver | 21 | 1/186 | 0.61 | 0.03 ± 0.1 | 75 | |

| S1 | Serum | 21 | 1/249 | 0.49 | 0.03 ± 0.08 | 69 | ||

| D | 2.12.94 | L0 | Liver | 10 | 1/140 | 0.7 | 0.01 ± 0.004 | 79 |

| S0 | Serum | 10 | 1/350 | 0.1 | 0.006 ± 0.003 | 86 | ||

| 29.2.00 | L1 | Liver | 23 | 1/163 | 0.55 | 0.2 ± 0.04 | 76 | |

| S1 | Serum | 19 | 1/337 | 0.27 | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 84 | ||

Seventy amino acids were analyzed for each clone.

Comparison of liver and serum quasispecies in all patients.

Table 2 summarizes the results obtained for patients A to D at the amino acid level. For patients A, B, and D amino acid consensus sequences in the four samples analyzed (L0, S0, L1, and S1) were identical. In patient C, three of the four samples analyzed (L0, S0, and L1) had the same amino acid consensus sequence but this sequence differed at two residues from the consensus sequence of sample S1. Nevertheless this difference was due to the existence of a double population in samples L1 and S1, with a different proportion of each population in the samples (the consensus residue at a given position is defined when the residue is present in 60% or more of the sequences [8]).

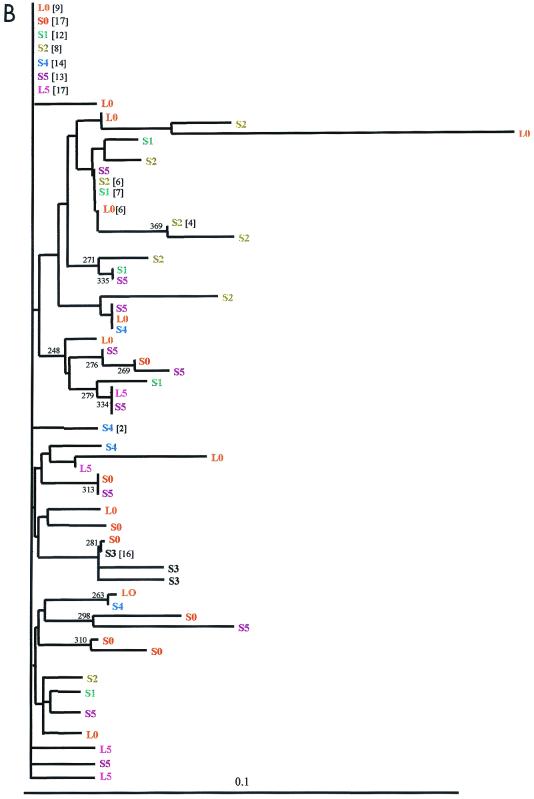

Phylogenetic analysis showed that, in all patients, amino acid sequences from the first liver-serum sample pair did not segregate from those of the second pair (see Fig. 2B; data not shown).

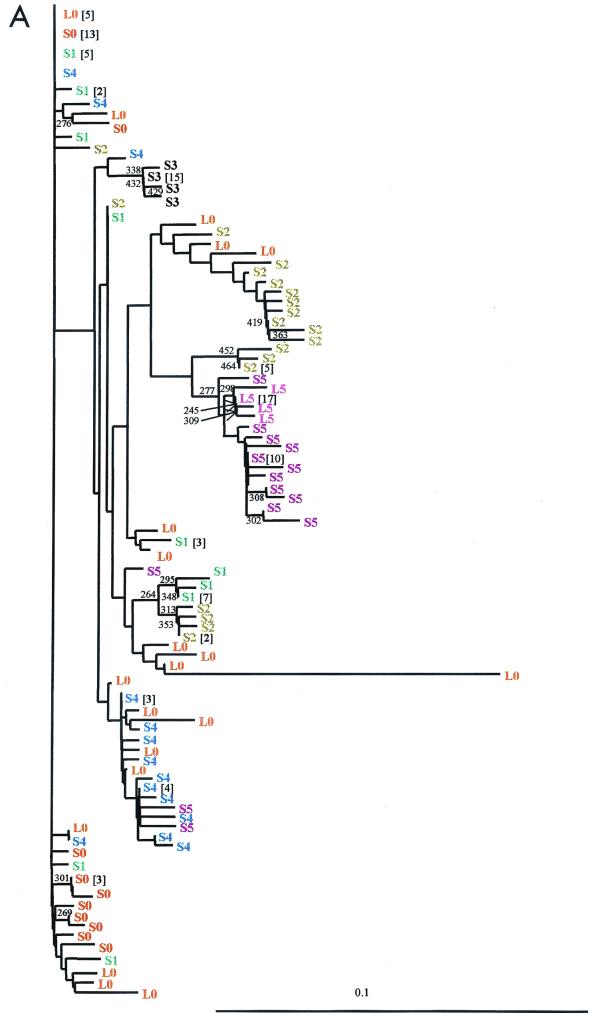

FIG. 2.

HCV phylogenetic reconstruction of long-term evolutionary relationship from a nonprogressive chronic hepatitis C patient. The phylogenetic analysis shown consists of unrooted neighbor-joining trees of nucleotide (A) and deduced amino acid (B) sequences from two liver (S0 and S5) and six serum (L0 to L5) samples. Numbers in brackets, numbers of identical sequences. Numbers indicate the bootstrap support (500 replicates); values of 50% or more are indicated.

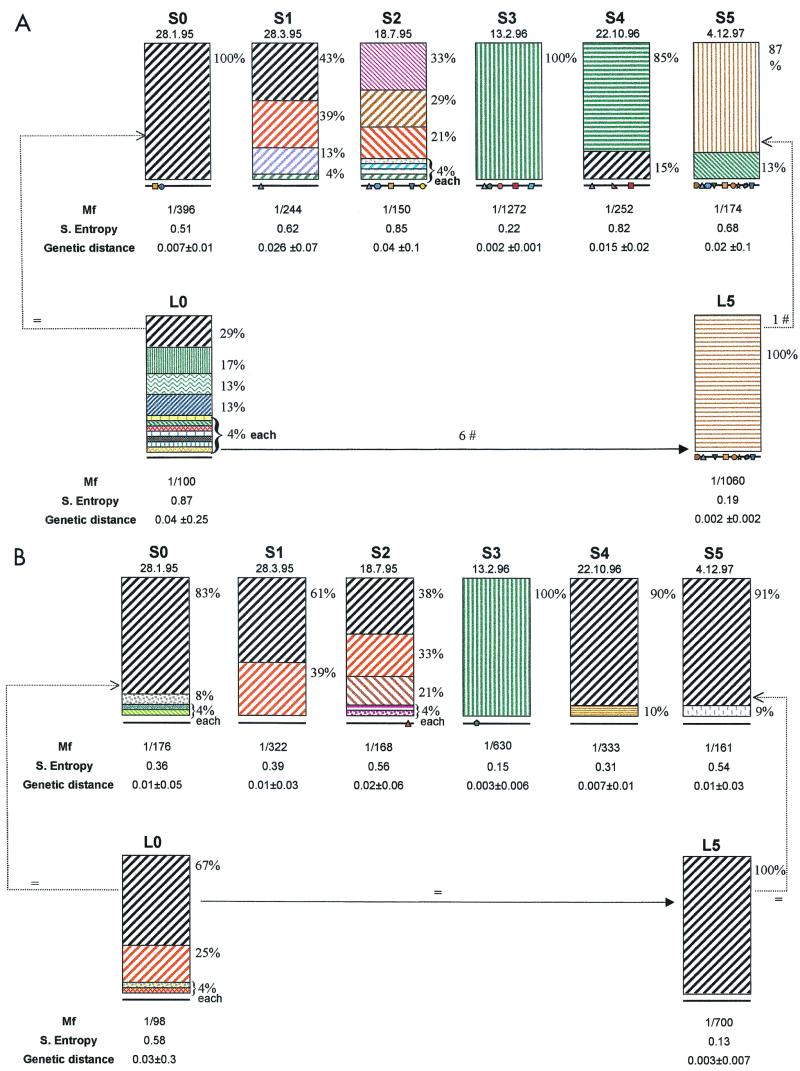

Regarding the quasispecies structure at the amino acid level, we observed that the liver/serum complexity ratios (Mf, Shannon entropy, and genetic distance) in the paired samples analyzed (L0-S0 and L1-S1) from patients B and D were similar (Table 2; patient B had the same level of complexity in the liver and serum in both paired samples, and patient D had more-complex serum quasispecies in both paired samples). In contrast, in patients A and C we found differences in this ratio between the two paired samples. In patient A, whereas the serum population was, on average, twofold less complex than that in liver in the first pair of samples (L0-S0), in the second pair (L5-S5) the serum population was fourfold more complex than the liver population (Table 2 and Fig. 1B). In patient C, for the first pair of liver and serum samples (L0-S0) the quasispecies in serum was twofold more complex than that in liver while in the second pair of samples (L1-S1) the complexities of the quasispecies in the two compartments were similar (Table 2). No correlation between the degree of complexity at the amino acid level and the stage of liver disease in the first pair of samples (L0-S0) was found in patient C. However, in agreement with our previous results, the liver/serum complexity ratio of the second pair (L1-S1) (5) fell within the correlation range (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Signature mutation pattern: diversity of viral forms and shift in the HCV quasispecies in serum and liver samples over time. Nucleotide (A) and amino acid (B) sequences of the E2(p7)-NS2 junction quasispecies in serum (S0 to S5) and liver (L0 to L5) were grouped as clusters and represented as histograms. Groups were made according to identity at some points so that nucleotide sequences in any subgroup shared three or more specific mutations which were not present together in any other sequence subset in the same or in other samples; subsequent intergroup differences ranged from three to seven mutations and intragroup nucleotide differences were single point mutations (A). Similarly, amino acid sequences in any subgroup share one or more amino acid replacements, so intergroup amino acid differences consisted of one or two substitutions and intragroup amino acid differences were single point substitutions (B). Same colors and patterns identify identical subgroups. Same colors but different patterns identify related groups. Mutations in the consensus sequence of the studied viral quasispecies over time are shown at the bottom of each histogram (each symbol represents one mutation). Mf, Shannon entropy, and genetic distance for each sample are shown below the respective histogram.

Patient A: genotypic fluctuations in HCV quasispecies over 3 years.

Overall, values of Mf, proportion of variants present (Shannon entropy), and genetic distance in both serum and liver samples varied widely from sample to sample (Fig. 1).

(i) Serum viral populations.

The net difference between the first (S0) and the last (S5) nucleotide consensus sequences from serum were 10 mutations; nevertheless, comparison of the consensus sequences from the consecutive serum sample quasispecies failed to demonstrate a gradual accumulation of mutations. Except for a mutation at position 2707, which became fixed between the first two samples (S0 to S1), most mutations were present only transiently.

Nucleotide sequence populations at each time point were grouped according to their identities (signature mutation pattern; Fig. 1), resulting in a different consensus sequence for each subgroup (Fig. 1A). Figure 1 shows the changes in quasispecies complexity over time; these changes were subsequently analyzed through population parameters. Phylogenetic analysis segregation of these nucleotide sequences coincides with the former grouping (Fig. 2A).

The analysis of all population parameters (Shannon entropy, Mf, and intrasample genetic distance) revealed a fluctuating behavior in the structure of the circulating quasispecies during the studied period (Fig. 1A). For all parameters, quasispecies complexity increased from S0 to S1, S1 to S2, S3 to S4, and S4 to S5 (with the exception in the last interval for Shannon entropy) and decreased from S2 to S3. Intrasample genetic distances (Fig. 1A) aptly illustrate the oscillatory pattern of the complexity and the rate of evolution of HCV quasispecies throughout the course of infection.

(ii) Liver viral populations.

Consensus nucleotide sequences of the two liver quasispecies (L0 and L5) differed at eight positions (quantitatively similar to the observed difference between their corresponding serum quasispecies). Important differences in quasispecies complexity between the two samples were also seen. The population of sequences corresponding to L0 was composed of seven individual sequences (each one representing 4% of the total), several minor groups consisting of very similar sequences representing 13, 13, and 17% of the total, and a major group representing 29% of the total (Fig. 1A). None of the sequences present in the second liver biopsy sample (L5) was identical to those present in the initial biopsy sample (the most closely related sequence, differing at six positions), and the complexity of the population was far lower in the repeat biopsy sample.

Phylogenetic analysis of sequences of serum and liver samples was performed to establish the relationship between samples during the infection (Fig. 2A) and specifically to monitor the persistence of minor sequences and the changes of master sequences. The majority of sequence groups in all serum samples had sequences identical or similar (0 to 3 single mutations) to those observed in the first liver biopsy sample (L0), even though sometimes at a very low frequency. Surprisingly, S5 and L5 major populations seemed to come from a minor group of the S2 sample, undetected in the first liver sample.

The master sequence in the first serum sample (S0) was completely replaced after 171 days by a complex population of sequences in S2; these were subsequently replaced by a mutant sequence (S3) in 210 days, which in turn evolved after 252 days into a mixture of two subpopulations (85 and 15%), one of which contained sequences identical to the S0 master. Both populations were replaced by two other new ones in the last serum sample studied (S5): a minor subpopulation derived from sequences present in the original liver population and a master sequence which clustered with the major population found in the second liver specimen.

Patient A: amino acid fluctuations in HCV quasispecies over 3 years.

The signature mutation pattern and phylogenetic analysis of deduced amino acid sequences from serum and liver viral populations are presented in Fig. 1B and 2B, respectively. All but one of the amino acid consensus sequences (S3) were identical; after 3 years no amino acid substitution became fixed. Synonymous substitutions dominated overall variation both in serum and liver populations, except in serum samples S0 and S3; thus amino acid sequence complexity of the viral populations was considerably narrower than the complexity of the nucleotide sequences (Table 2).

Viral RNA quantitation at the E2(p7)-NS2 region.

In all samples investigated (see Materials and Methods), the number of E2(p7)-NS2 RNA molecules subject to amplification was at least 104, as confirmed by both RNA E2(p7)-NS2 quantitation and the positive result of amplification of the 1:10 dilution of the cDNA transcribed from the template with the same primer set used for quasispecies analysis in all serum and liver samples evaluated. This suggests that neither the input RNA molecules nor the efficiency of the reverse transcriptase to transcribe the RNA of this region led to underestimation of the quasispecies complexity.

DISCUSSION

For Darwin and most evolutionists, the individual organism is the object of selection (31). Nevertheless, according to Eigen's theory of quasispecies, the individual RNA replicon, as an entity for natural selection, is absent (12). Instead, selection acts on an ensemble of variant replicons: the quasipecies as a whole. In fact, what appears to be a revolutionary concept in theoretical biology (11), arising from Eigen's theory, was found throughout the world of RNA viruses as a way of organizing their genetic information, and HCV is a good example. The uncertainty of the genetic identity of the viral agent is maintained, both in space (serum and liver) and in time, throughout the infection. Our understanding of the viral life cycle relies on the knowledge of the behavior and relationships among components of the population of individuals, which, in turn, might help in understanding viral persistence and failure of treatment (1, 3, 13, 14, 39). In an attempt to define the continuity of the genetic constitution of the viral quasispecies in space and time, we analyzed series of sequential liver and serum samples in four patients with chronic hepatitis C.

In a previous work (4) we described two patients in whom the replicating HCV quasispecies was twice as complex as that circulating in the serum at the E2(p7)-NS2 region. We then investigated the liver/serum complexity ratio in a larger group of HCV-infected patients and identified a subset of patients (40%) with similar levels of complexity in both compartments, in whom the degree of complexity at the amino acid level correlated significantly with disease stage (5) and did not correlate with other clinical parameters (duration of infection, age, necroinflammation degree, etc.). In the present study, we expanded original cross-sectional findings for four patients with nonprogressive hepatitis C by analyzing viral population parameters in repeat liver-serum sample pairs obtained 3 to 6 years apart.

The results of the present study confirm and extend our previous findings regarding differences between replicating and circulating viral population in all four patients (samples L0 and S0; Table 2) (4). As our results demonstrate, these differences were not due to limitations in the input RNA molecules, efficiency of the reverse transcriptase in the region analyzed, or misincorporation errors during the amplification procedure.

In previous cross-sectional studies dissimilarities between liver and serum quasispecies raised the question of the potential origin of the circulating viruses. We proposed that the higher complexity in the liver could be due to the existence of different functional compartments with distinct replication kinetics in the infected liver or by an excess contribution of sequences unable to become incorporated into mature virions and to be released to the circulation (4). For the opposite finding, that is, higher complexity in the circulating pool in addition to the minor contribution of variants replicating in extrahepatic sites (26, 34, 38), the possibility of differences in the clearance rates of major variants leading to an overrepresentation of the mutant repertoire has been suggested (5, 15). The results of the present study provide additional information to clarify this issue. First, in all patients most circulating sequences found in the consecutive samples could be traced back to sequences present in the mutant spectrum of the initial liver specimen (L0) (Fig. 2A for patient A; data not shown for patients B to D). Second, the lack of complete nucleotide identity in some patients between the replicating and circulating major species (for instance, in the second liver-serum pair from patient A [L5-S5]) could not be easily explained given the different rates of turnover of virus in the two compartments and the greater stability of virions in the liver (half-life [t1/2] = 2.7 h for free serum virions; t1/2 = 1.7 to 70 days for infected cells) (35). All this reinforces our original suggestions that there is either a differential effect of selective forces or hepatocytes with different kinetics of viral replication in the two compartments and that preferential release from one type of cell or another fluctuates over time (4). Also, the reemergence of minority components from the first replicating viral quasispecies in consecutive serum samples in patient A could be interpreted as a molecular record of a past quasispecies composition, as if a molecular memory was acting (43). Molecular memory may be glimpsed from reinoculation studies of chronically HCV-infected chimpanzees in which preexisting, slower-replicating quasispecies outlive faster-replicating variants present in the second inoculation (47). Hence, no extrahepatic origin must be invoked to explain discrepancies in quasispecies composition, and most, if not all, sequences found in the replicating compartment at our level of resolution (44) are viable and able to gain access to the circulation (Fig. 1A and 2A).

Also, the observed replacement of the replicating pool by a homogeneous population of sequences in the last biopsy sample of patient A is more apparent than real, since the minor population of sequences in the coincident circulating pool was more related to sequences in the first biopsy sample, implying that at higher resolution the parental sequence should have been detected.

It is well known that the evolutionary potential of the HCV genome varies markedly at different loci depending on structural and functional constraints (i.e., those of the 5′-noncoding region) and positive selective forces such as that of the immune system on the hypervariable region of E2 (14, 36, 37). It is possible that the quasispecies fluctuation of the genomic region here investigated is a consequence of selective forces acting at other functional or antigenic regions of the encoded HCV proteins, favoring replication of a specific sequence subset from those present in the liver. Whatever the specific nature of the forces driving the observed fluctuations in composition and complexity of the viral population in both compartments, it is noteworthy that they have been found to occur in patients with persistently normal ALT levels and nonprogressive liver damage over a 3- to 6-year period (Table 1). Hence, in such a stable clinical situation it is tempting to speculate that the observed nucleotide fluctuation is not the result of a substantial change in the environmental conditions but rather that continuous reshaping of the viral quasispecies is necessary for the virus to persist and maintain steady-state replication. In fact, fitness variations in constant environments have been described in other viral systems (9, 42).

The high rate of nucleotide changes within and between samples contrasts with the overall low rate of amino acid changes (32) so that the most heterogeneous populations had no more than five groups of sequences differing at one or two amino acid positions (Fig. 1B). All but one of the consensus amino acid sequences were identical in both serum and liver specimens. This finding implies some kind of negative selective force driven by functional or structural constraints of the protein product encoded at this level.

With regard to our previous observation of a significant correlation between liver/serum complexity ratio and disease stage, the present study demonstrates that this parameter is not stable but fluctuates over relatively short periods of time in the absence of apparent disease progression. Hence, the liver/serum complexity ratio does not identify a particular group of patients but rather a particular state of the infecting quasispecies, which may change over time. Thus, one should be cautious when trying to correlate liver damage and quasispecies complexity. As our results have demonstrated, such correlation is found only in those coincident-time point samples, obtained from individual patients, in which the liver and serum quasispecies have the same or similar levels of complexity (patients were considered to have the same level of complexity when the ratio between liver and serum values for a given parameter was between 0.5 and 2). The issue of whether other methods of complexity analysis or investigation of quasispecies behavior at other genomic regions may provide more practical information warrants further studies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Mariona Parera for her excellent technical assistance.

This investigation was supported in part by grants 99-0108 and 2000-0347 from the Comisión Interministerial de Ciencia y Tecnología (CICYT) and by the Fundació per a la Recerca Biomèdica i la Docència de l' Hospital Vall d'Hebron.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmed R, Stevens J G. Viral persistence. In: Fields B N, Knipe D N, editors. Fundamental virology. New York, N.Y: Raven Press; 1991. pp. 241–265. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brambilla S, Bellati G, Asti M, Lisa A, Candusso M E, d'Amico M, Grassi G, Giacca M, Franchini A, Bruno S, Ideo G, Mondelli M U, Silini E M. Dynamics of hypervariable region 1 variation in hepatitis C virus infection and correlation with clinical and virological features of liver disease. Hepatology. 1998;27:1678–1686. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bukh J, Miller R H, Purcell R H. Genetic heterogeneity of hepatitis C virus: quasispecies and genotypes. Semin Liver Dis. 1995;15:41–63. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cabot B, Esteban J I, Martell M, Genesca J, Vargas V, Esteban R, Guardia J, Gomez J. Structure of replicating hepatitis C virus (HCV) quasispecies in the liver may not be reflected by analysis of circulating HCV virions. J Virol. 1997;71:1732–1734. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.2.1732-1734.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cabot B, Martell M, Esteban J I, Sauleda S, Otero T, Esteban R, Guardia J, Gomez J. Nucleotide and amino acid complexity of hepatitis C virus quasispecies in serum and liver. J Virol. 2000;74:805–811. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.2.805-811.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cerny A, Chisari F V. Pathogenesis of chronic hepatitis C: immunological features of hepatic injury and viral persistence. Hepatology. 1999;30:595–601. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devereux H L, Brown D, Dusheiko G M, Emery V C, Lee C A. Long-term evolution of the 5′UTR and a region of NS4 containing a CTL epitope of hepatitis C virus in two haemophilic patients. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:583–590. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-3-583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Domingo E. Biological significance of viral quasispecies. J Viral Hepatol. 1996;2:247–261. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Domingo E, Escarmís C, Menendez-Arias L, Holland J J. Viral quasispecies and fitness variations. In: Domingo E, Webster R H J, editors. Origin and evolution of viruses. London, United Kingdom: Academic Press; 1999. pp. 141–161. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Domingo E, Holland J J. RNA virus mutations and fitness for survival. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1997;51:151–178. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.51.1.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eigen M. Steps towards life. New York, N.Y: Oxford University Press Inc; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eigen M, Biebricher C K. Variability of RNA genomes. Sequence space and quasispecies distribution. In: Domingo E, Holland J J, Ahlquist P, editors. RNA genetics. Boca Raton., Fla: CRC Press, Inc.; 1988. pp. 211–245. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Esteban J I, Gomez J, Martell M, Guardia J. Hepatitis C. In: Wilson R A, editor. Viral hepatitis. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker Inc.; 1997. pp. 147–216. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Esteban J I, Martell M, Carman W F, Gómez J. The impact of rapid evolution of the hepatitis viruses. In: Domingo E, Holland J J, Webster R E, editors. The origin and evolution of RNA viruses. London, United Kingdom: Academic Press; 1999. pp. 345–375. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fan X, Solomon H, Poulos J E, Neuschwander-Tetri B A, Di Bisceglie A M. Comparison of genetic heterogeneity of hepatitis C viral RNA in liver tissue and serum. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1347–1354. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Felsenstein J. PHYLIP Inference Package, version 3.5. Seattle: University of Washington; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gerber M A. Pathobiologic effects of hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 1995;22(Suppl.):83–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gonzalez-Peralta R P, Davis G L, Lau J Y. Pathogenetic mechanisms of hepatocellular damage in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J Hepatol. 1994;21:255–259. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(05)80405-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gonzalez-Peralta R P, Qian K, She J Y, Davis G L, Ohno T, Mizokami M, Lau J Y. Clinical implications of viral quasispecies heterogeneity in chronic hepatitis C. J Med Virol. 1996;49:242–247. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9071(199607)49:3<242::AID-JMV14>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hayashi J, Kishihara Y, Yamaji K, Furusyo N, Yamamoto T, Pae Y, Etoh Y, Ikematsu H, Kashiwagi S. Hepatitis C viral quasispecies and liver damage in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology. 1997;25:697–701. doi: 10.1002/hep.510250334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Honda M, Kaneko S, Sakai A, Unoura M, Murakami S, Kobayashi K. Degree of diversity of hepatitis C virus quasispecies and progression of liver disease. Hepatology. 1994;20:1144–1151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoofnagle J H. Hepatitis C: the clinical spectrum of disease. Hepatology. 1997;26:15s–20s. doi: 10.1002/hep.510260703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ishak K, Baptista A, Bianchi L, Callea F, De Groote J, Gudat F, Denk H, Desmet V, Korb G, MacSween R N, et al. Histological grading and staging of chronic hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1995;22:696–699. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(95)80226-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kinloch R A, Roller R J, Wassarman P M. Quantitative analysis of specific messenger RNAs by ribonuclease protection. Methods Enzymol. 1993;225:294–303. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(93)25020-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koizumi K, Enomoto M, Kurosaki M, Murakami T, Izumi N, Marumo F, Sato C. Diversity of quasispecies in various disease stages of chronic hepatitis C virus infection and its significance in interferon treatment. Hepatology. 1995;22:30–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laskus T, Radkowski M, Wang L F, Jang S J, Vargas H, Rakela J. Hepatitis C virus quasispecies in patients infected with HIV-1: correlation with extrahepatic viral replication. Virology. 1998;248:164–171. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.López-Labrador F X, Ampurdanès S, Giménez-Barcons M, Guilera M, Costa J, Jiménez de Anta M T, Sánchez-Tapies J M, Rodés J, Sáiz J C. Relationship of the genomic complexity of hepatitis C virus with liver disease severity and response to interferon in patients with chronic HCV genotype 1b interferon. Hepatology. 1999;29:897–903. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maggi F, Fornai C, Vatteroni M L, Giorgi M, Morrica A, Pistello M, Cammarota G, Marchi S, Ciccorossi P, Bionda A, Bendinelli M. Differences in hepatitis C virus quasispecies composition between liver, peripheral blood mononuclear cells and plasma. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:1521–1525. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-7-1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martell M, Esteban J I, Quer J, Genesca J, Weiner A, Esteban R, Guardia J, Gomez J. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) circulates as a population of different but closely related genomes: quasispecies nature of HCV genome distribution. J Virol. 1992;66:3225–3229. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.5.3225-3229.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martell M, Gómez J, Esteban J I, Sauleda S, Quer J, Cabot B, Esteban R, Guardia J. High-throughput real-time reverse transcription-PCR quantitation of hepatitis C virus RNA. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:327–332. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.2.327-332.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mayr E. The objects of selection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:2091–2094. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nagayama K, Kurosaki M, Enomoto N, Maekawa S Y, Miyasaka Y, Tazawa J, Izumi N, Marumo F, Sato C. Time-related changes in full-length hepatitis C virus sequences and hepatitis activity. Virology. 1999;263:244–253. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Naito M, Hayashi N, Moribe T, Hagiwara H, Mita E, Kanazawa Y, Kasahara A, Fusamoto H, Kamada T. Hepatitis C viral quasispecies in hepatitis C virus carriers with normal liver enzymes and patients with type C chronic liver disease. Hepatology. 1995;22:407–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Navas S, Martin J, Quiroga J A, Castillo I, Carreño V. Genetic diversity and tissue compartmentalization of the hepatitis C virus genome in blood mononuclear cells, liver, and serum from chronic hepatitis C patients. J Virol. 1998;72:1640–1646. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.1640-1646.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neumann A U, Lam N P, Dahari H, Gretch D R, Wiley T E, Layden T J, Perelson A S. Hepatitis C viral dynamics in vivo and the antiviral efficacy of interferon-alpha therapy. Science. 1998;282:103–107. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5386.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ogata N, Alter H J, Miller R H, Purcell R H. Nucleotide sequence and mutation rate of the H strain of hepatitis C virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:3392–3396. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.8.3392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Okamoto H, Kojima M, Okada S, Yoshizawa H, Iizuka H, Tanaka T, Muchmore E E, Peterson D A, Ito Y, Mishiro S. Genetic drift of hepatitis C virus during an 8.2-year infection in a chimpanzee: variability and stability. Virology. 1992;190:894–899. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90933-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Okuda M, Hino K, Korenaga M, Yamaguchi Y, Katoh Y, Okita K. Differences in hypervariable region 1 quasispecies of hepatitis C virus in human serum, peripheral blood mononuclear cells, and liver. Hepatology. 1999;29:217–222. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pawlotsky J M. Hepatitis C: viral markers and quasispecies. In: Liang T J, Hoofnagle J H, editors. Hepatitis C. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press; 2000. pp. 25–52. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pawlotsky J M, Germanidis G, Neumann A U, Pellerin M, Frainais P O, Dhumeaux D. Interferon resistance of hepatitis C virus genotype 1b: relationship to nonstructural 5A gene quasispecies mutations. J Virol. 1998;72:2795–2805. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.2795-2805.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pawlotsky J M, Pellerin M, Bouvier M, Roudot-Thoraval F, Germanidis G, Bastie A, Darthuy F, Remire J, Soussy C J, Dhumeaux D. Genetic complexity of the hypervariable region 1 (HVR1) of hepatitis C virus (HCV): influence on the characteristics of the infection and responses to interferon alfa therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Med Virol. 1998;54:256–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Quer J, Huerta R, Novella I S, Tsimring L, Domingo E, Holland J J. Reproducible nonlinear population dynamics and critical points during replicative competitions of RNA virus quasispecies. J Mol Biol. 1996;264:465–471. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ruiz-Jarabo C M, Arias A, Baranowski E, Escarmís C, Domingo E. Memory in viral quasispecies. J Virol. 2000;74:3543–3547. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.8.3543-3547.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vartanian J P, Meyerhans A, Henry M, Wain-Hobson S. High-resolution structure of an HIV-1 quasispecies: identification of novel coding sequences. AIDS. 1992;6:1095–1098. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199210000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wakita T, Taya C, Katsume A, Kato J, Yonekawa H, Kanegae Y, Saito I, Hayashi Y, Koike M, Kohara M. Efficient conditional transgene expression in hepatitis C virus cDNA transgenic mice mediated by the Cre/loxP system. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:9001–9006. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.15.9001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wolinsky S M, Korber B T, Neumann A U, Daniels M, Kunstman K J, Whetsell A J, Furtado M R, Cao Y, Ho D D, Safrit J T. Adaptive evolution of human immunodeficiency virus-type 1 during the natural course of infection. Science. 1996;272:537–542. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5261.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wyatt C A, Andrus L, Brotman B, Huang F, Lee D H, Prince A M. Immunity in chimpanzees chronically infected with hepatitis C virus: role of minor quasispecies in reinfection. J Virol. 1998;72:1725–1730. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.3.1725-1730.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yuki N, Hayashi N, Moribe T, Matsushita Y, Tabata T, Inoue T, Kanazawa Y, Ohkawa K, Kasahara A, Fusamoto H, Kamada T. Relation of disease activity during chronic hepatitis C infection to complexity of hypervariable region 1 quasispecies. Hepatology. 1997;25:439–444. doi: 10.1053/jhep.1997.v25.pm0009021961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]