Abstract

Purpose

While the benefit of short-term androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) has been established for patients with intermediate-risk (IR) prostate cancer (PCa) receiving dose-escalated external beam radiation therapy (EBRT), the role of ADT for patients treated with brachytherapy (BT) with or without supplemental EBRT (sEBRT) is less clear.

Material and methods

We conducted a single-institution retrospective analysis of men with National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) unfavorable IR (UIR) PCa. All patients received BT with or without sEBRT, and were stratified by the receipt of 4-6 months of ADT. Kaplan-Meier method was used to measure biochemical progression- free survival (bPFS) between men who did vs. did not receive ADT. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards with backward selection was utilized to determine association of concomitant ADT with bPFS accounting for confounding variables.

Results

We identified 201 eligible patients treated between 2002 and 2019, 78 (38.8%) of whom received ADT. Median follow-up was 15 years. On univariable analysis, there was no significant association of ADT use with bPFS (HR = 0.95, 95% CI: 0.34-2.63, p = 0.92). Only PSA ≥ 10 was significant for association with worse bPFS (HR = 3.51, 95% CI: 1.29-9.52, p = 0.014). On multivariable analysis, there was no association of ADT use with bPFS (HR = 0.97, 95% CI: 0.34-2.78, p = 0.96).

Conclusions

Short-course ADT was not associated with improved bPFS in our study among men with UIR PCa treated with BT with or without sEBRT. These findings suggest that dose intensification achieved with BT may alone be sufficient in treating selected patients with UIR disease, but prospective studies are warranted.

Keywords: unfavorable intermediate-risk, prostate cancer, brachytherapy, androgen deprivation therapy

Purpose

Intermediate-risk prostate cancer accounts for over one-third of the estimated 288,300 new cases of prostate cancer in the United States [1, 2]. Radiotherapeutic management frequently entails dose-escalated external beam radiation (EBRT) [3-5], for which data shows improvement in biochemical control, distant metastasis, and prostate cancer mortality with short-term androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) [6]. Brachytherapy (BT) is frequently utilized for the management of intermediate-risk prostate cancer, and there is data to support its use either as monotherapy or with supplemental EBRT (sEBRT) [7, 8]. Patients treated with BT with or without sEBRT comprise a small proportion of those prospectively studied to assess ADT efficacy, making it difficult to render definitive conclusions regarding the benefit of ADT for patients treated with brachytherapy-based radiotherapy [6]. Given that the advantage of ADT has not been prospectively tested explicitly in patients receiving brachytherapy, we sought to evaluate the impact of ADT on patients treated with brachytherapy with or without sEBRT.

Material and methods

This was a single-institution study across multiple hospital sites, approved by our institutional review board. We queried our institutional database for patients with NCCN unfavorable intermediate-risk (UIR) prostate cancer with biopsy-proven Gleason grade group 3 prostate cancer or grade group 2 prostate cancer, with an additional intermediate-risk factor (prostate-specific antigen [PSA] 10-20, T2b-2c, ≥ 50% positive biopsy cores). All patients received either low-dose-rate (LDR) or high-dose-rate (HDR) BT with or without sEBRT. The decision to treat with sEBRT and ADT was per the treating physician’s discretion based on clinico-pathologic risk factors, as well as patient age, life expectancy, and comorbidities. Patients who received HDR monotherapy were treated with 27 Gy in 2 fractions to the prostate clinical target volume (CTV). Patients who received HDR with sEBRT were given 15 Gy in a single-fraction to CTV for brachytherapy treatment. Patients who received LDR monotherapy were treated with 145 Gy in a single-fraction to the prostate CTV. Patients who received LDR with sEBRT were treated with 110 Gy in a single-fraction for brachytherapy treatment. sEBRT was delivered using 45 Gy in 25 fractions to the prostate and SV with or without inclusion of pelvic lymph nodes, using 3D conformal or volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT) technique. Patients were stratified according to the receipt of short-term ADT (range, 4-6 months) or no ADT.

Baseline characteristics between the two groups (patients treated with ADT vs. without ADT) were compared using chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables, and ANOVA or Kruskal Wallis tests for numerical variables. Kaplan-Meier curves were utilized to assess biochemical progression-free survival (bPFS), defined as the time from date of biopsy to date of clinical or biochemical recurrence or death, and patients were censored at the time of last follow-up. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards model using backward variable selection with an α of 0.05 for removal was performed to account for age, race, insurance status, body mass index (BMI), T stage, Gleason grade group, BT type, receipt of sEBRT, and sEBRT target. Furthermore, to account for variability in diagnostic workup, additional covariates studied included use of pre-treatment MRI, pre-treatment CT scan, and pre-treatment bone scan. A test for interaction between Gleason grade group and receipt of ADT was performed. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS v. 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and SAS macros developed by the Biostatistics Shared Resource at Winship Cancer Institute [9]. Tests were two-sided, with a 0.05 level of significance.

Results

We identified 201 eligible patients treated between 2002 and 2019, with a median follow-up of 15 years. Table 1 shows the patient characteristics of the cohort. Seventy-eight (38.8%) patients received ADT. Those who received ADT were more frequently White race patients, more likely to obtain pre-treatment MRI and bone scan, more likely to have grade group 3 cancer, and more likely to receive sEBRT.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the cohort stratified by androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) receipt

| Covariate | Total N = 201 (100.0%) |

ADT | p-value** | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes n = 78 (38.8%) |

No n = 123 (61.2%) |

||||

| Age (years) | 0.080* | ||||

| Median (Q1-Q3) | 65 (59-69) | 64 (58-68) | 65 (60-70) | ||

| Race | < 0.001 | ||||

| African American/other | 76 (37.8) | 18 (23.1) | 58 (47.2) | ||

| White | 125 (62.2) | 60 (76.9) | 65 (52.8) | ||

| PSA | 0.592 | ||||

| < 10 | 161 (80.1) | 61 (78.2) | 100 (81.3) | ||

| ≥ 10 | 40 (19.9) | 17 (21.8) | 23 (18.7) | ||

| Pre-treatment MRI | 0.010 | ||||

| Yes | 122 (60.7) | 56 (71.8) | 66 (53.7) | ||

| No | 79 (39.3) | 22 (28.2) | 57 (46.3) | ||

| Pre-treatment CT scan | 0.641 | ||||

| Yes | 33 (16.4) | 14 (17.9) | 19 (15.4) | ||

| No | 168 (83.6) | 64 (82.1) | 104 (84.6) | ||

| Pre-treatment bone scan | < 0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 115 (57.2) | 59 (75.6) | 56 (45.5) | ||

| No | 86 (42.8) | 19 (24.4) | 67 (54.5) | ||

| Obese | 0.394 | ||||

| Yes | 39 (41.1) | 14 (35.9) | 25 (44.6) | ||

| No | 56 (58.9) | 25 (64.1) | 31 (55.4) | ||

| T stage | 0.281 | ||||

| T1 | 132 (66.0) | 55 (70.5) | 77 (63.1) | ||

| T2 | 68 (34.0) | 23 (29.5) | 45 (36.9) | ||

| Gleason grade group | < 0.001 | ||||

| 2 | 106 (52.7) | 21 (26.9) | 85 (69.1) | ||

| 3 | 95 (47.3) | 57 (73.1) | 38 (30.9) | ||

| Insurance | 0.445 | ||||

| Private | 106 (52.7) | 45 (57.7) | 61 (49.6) | ||

| Medicare | 78 (38.8) | 26 (33.3) | 52 (42.3) | ||

| Other/unknown | 17 (8.5) | 7 (9.0) | 10 (8.1) | ||

| Brachytherapy type | 0.008 | ||||

| HDR | 136 (80.0) | 53 (91.4) | 83 (74.1) | ||

| LDR | 34 (20.0) | 5 (8.6) | 29 (25.9) | ||

| Supplemental external radiation therapy | 0.004 | ||||

| Yes | 180 (89.6) | 76 (97.4) | 104 (84.6) | ||

| No | 21 (10.4) | 2 (2.6) | 19 (15.4) | ||

| Supplemental external radiation therapy target | 0.009 | ||||

| No sEBRT | 21 (12.4) | 1 (1.7) | 20 (17.9) | ||

| Prostate + seminal vesicles | 121 (71.2) | 45 (77.6) | 76 (67.9) | ||

| Pelvic lymph nodes + prostate + seminal vesicles | 28 (16.5) | 12 (20.7) | 16 (14.3) | ||

| BMI | 0.874* | ||||

| Total (n) | 95 | 39 | 56 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 30.2 (6.3) | 30.6 (7.7) | 29.9 (5.1) | ||

| Median (Q1-Q3) | 29 (26.2-33.2) | 29.3 (26.2-34.3) | 28.7 (25.8-33.1) | ||

| Min-max | 19.4-62.6 | 19.4-62.6 | 21.9-41.9 | ||

p-value was calculated by either parametric (ANOVA, chi-square) or non-parametric (Kruskal-Wallis, Fisher’s exact) test whenever appropriate, based on normality test of data distribution and sample size; * non-parametric test (Kruskal-Wallis or Fisher’s exact tests) was applied

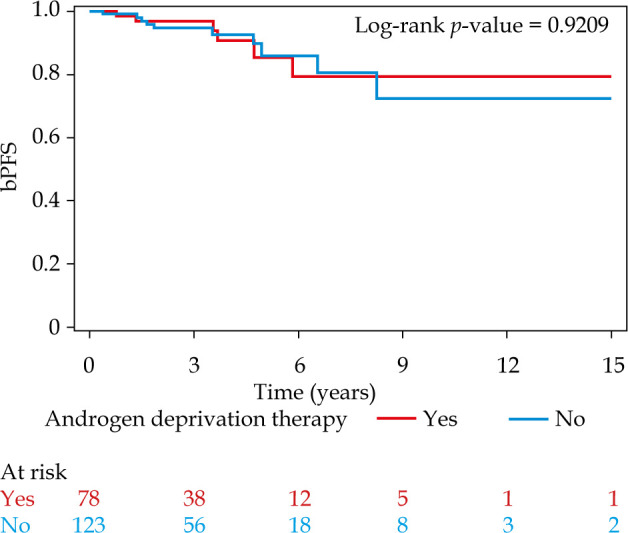

The 5- and 10-year bPFS for patients treated without ADT and with ADT was 86.0% (95% CI: 71.1-93.6) and 72.6% (95% CI: 47.3-87.2) vs. 85.5% (95% CI: 65.6-94.4) and 79.4% (95% CI: 56.0-91.2), respectively. On univariable analysis, there was no statistically significant association between ADT and bPFS (HR = 0.95, 95% CI: 0.34-2.63, p = 0.92) (Figure 1). The only variable associated with worse bPFS on univariable analysis was PSA ≥ 10 (HR = 3.51, 95% CI: 1.29-9.52, p = 0.014) (Supplementary Table 1). On multivariable analysis (Table 2), there was again no statistically significant association between ADT and bPFS (HR = 0.97, 95% CI: 0.34-2.78, p = 0.96). The only variables significant on multivariable analysis were PSA ≥ 10 (HR = 4.75, 95% CI: 1.65-13.70, p = 0.004) and receipt of pre-treatment MRI (HR = 3.77, 95% CI: 1.15-12.38, p = 0.029). Additionally, there was no significant interaction between Gleason grade group and receipt of ADT and bPFS (interaction, p = 0.88).

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves for biochemical progression-free survival (bPFS) for patients treated with or without androgen deprivation therapy

Table 2.

Multivariable Cox regression for biochemical progression-free survival*

| Covariate | Level | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | HR p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Androgen deprivation therapy | No | 1.03 (0.36-2.97) | 0.956 |

| Yes | – | – | |

| PSA | ≥ 10 | 4.75 (1.65-13.70) | 0.004 |

| < 10 | – | – | |

| Pre-treatment MRI | Yes | 3.77 (1.15-12.38) | 0.029 |

| No | – | – | |

| T stage | T1 | 0.37 (0.13-1.11) | 0.076 |

| T2 | – | – |

Backward selection with an α level of removal of 0.1. The following variables were removed from the model: insurance, age, brachytherapy type, supplemental external beam radiation therapy, external beam radiation target, Gleason score, obesity, pre-treatment bone scan, pre-treatment CT scan, and race

Supplementary Table

Discussion

In the current study among men with UIR PCa, we did not find an association of improved bPFS with utilization of ADT when added to BT with or without supplemental EBRT. This supports the option of omitting ADT in the setting of combined EBRT and BT accepted by current guidelines [10], and adds to a large body of studies, which suggest that dose intensification using BT may lessen the impact of radio-sensitizing benefit of ADT in IR PCa cases [4, 11-17]. The omission of ADT would spare patients from potential toxicity and adverse quality of life changes, including fatigue, hot flashes, sexual dysfunction, metabolic changes, and bone deterioration [18].

Currently, guidelines for UIR prostate cancer treated with radiation recommend either EBRT with short-term ADT or EBRT with BT boost with or without ADT [10]. The best available evidence supporting the use of ADT with modern dose-intensified radiotherapy is the NRG/RTOG 0815 trial, which showed the benefit of short-term utilization of ADT in disease control when added to dose-escalated radiation for intermediate-risk prostate cancer [6]. Given the minority of patients who received BT in this trial as well as that the trial was not powered to assess the effect of ADT in men receiving BT boost, it is difficult to draw conclusive evidence of ADT’s benefit in the setting of BT. Since there are limited prospective data evaluating the benefit of ADT in UIR patients receiving BT as well as conflicting retrospective data [19], ADT is frequently omitted when BT is given [20].

In the current study, we did not find a benefit of ADT in the cohort of UIR patients treated with BT, most (90%) of whom received additional EBRT. Furthermore, while the number of patients who received BT alone in this study was small, no significant association of external beam radiation with improved biochemical progression-free survival was found. This confirms recent randomized evidence showing that BT without sEBRT is likely sufficient for disease control in IR PCa cases [7].

There is conflicting data regarding the benefit of adding ADT to BT in UIR PCa patients. A meta-analysis of 9 randomized trials with intermediate- and high-risk patients comparing EBRT with or without ADT and EBRT with or without BT, showed improved overall survival in patients receiving EBRT with ADT compared with EBRT with BT, suggesting that omission of ADT in BT-treated patients may lead to inferior outcomes [21]. However, since this study contained a small minority of patients with UIR PCa treated with EBRT with BT, it is difficult to draw conclusions regarding the benefit of ADT in this population. Retrospective data derived from the National Cancer Database (NCDB) limited to UIR patients show no significant benefit in adding ADT to patients receiving EBRT + BT [22]. A separate NCDB study investigating BT alone in UIR cases showed a benefit in overall survival with ADT plus BT, and superior overall survival in patients treated with BT alone versus EBRT alone [23]. These studies were hindered by lack of available data regarding disease control outcomes. A propensity score-matched study of UIR patients treated with EBRT to the prostate and seminal vesicle with high-dose-rate (HDR) BT boost, showed an improvement in biochemical failure-free survival with addition of ADT [24]. In another institutional analysis of UIR, high-risk (HR) and very-high risk (VHR) patients did not show biochemical control benefit with addition of ADT to iodine-125 (125I) brachytherapy [25]. Ultimately, the variability in results of these studies suggests that UIR PCa consists of a hete-rogeneous group of cancers for which genomic and/or radiographic stratification may be able to better select patients treated with BT who may benefit from addition of ADT [26, 27].

While the 5- and 10-year bPFS rates found in our study are comparable to those seen in prospective data of intermediate-risk prostate cancer patients [6-8], limitations related to selection bias may contribute to the finding of no statistically significant difference in bPFS with ADT. For example, patients who received ADT were more frequently diagnosed with grade group 3 (vs. 2) disease, staged with pre-treatment bone scan and MRI, and treated with sEBRT. This suggests that patients treated with ADT may have been selected for treatment intensification due to inherently higher risk of biochemical failure; it is possible that such selection bias could not be fully mitigated by multivariable analysis. Additionally, patients who received ADT were a minority in this study, and it is possible that this factor limits the study’s statistical power.

In conclusion, in this study among UIR PCa patients treated with BT-based dose escalation with or without ADT, we found no significant association between receiving ADT and improved bPFS. These findings suggest that for appropriately selected patients receiving BT, there may be little added benefit to ADT, but prospective validation is warranted.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary table is available on the journal’s website.

Funding

The research reported in this publication was supported in part by the Biostatistics and Bioinformatics Shared Resource of Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University and NIH/NCI under award number of P30CA138292. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors, and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The identifying data was anonymized for the review.

Disclosures

Bioethics Committee approval was not required.

References

- 1.Burt LM, Shrieve DC, Tward JD. Factors influencing prostate cancer patterns of care: An analysis of treatment variation using the SEER database. Adv Radiat Oncol 2018; 3: 170-180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Wagle NSet al. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin 2023; 73: 17-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zietman AL, DeSilvio ML, Slater JDet al. Comparison of conventional-dose vs high-dose conformal radiation therapy in clinically localized adenocarcinoma of the prostate: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2005; 294: 1233-1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krauss D, Kestin L, Ye Het al. Lack of benefit for the addition of androgen deprivation therapy to dose-escalated radiotherapy in the treatment of intermediate-and high-risk prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2011; 80: 1064-1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pasalic D, Kuban DA, Allen PKet al. Dose escalation for prostate adenocarcinoma: A long-term update on the outcomes of a phase 3, single institution randomized clinical trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2019; 104: 790-797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krauss DJ, Karrison T, Martinez AAet al. Dose-escalated radiotherapy alone or in combination with short-term androgen deprivation for intermediate-risk prostate cancer: Results of a phase III multi-institutional trial. J Clin Oncol 2023; 41: 3203-3216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Michalski JM, Winter KA, Prestidge BRet al. Effect of brachytherapy with external beam radiation therapy versus brachytherapy alone for intermediate-risk prostate cancer: NRG Oncology RTOG 0232 randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol 2023; 41: 4035-4044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oh J, Tyldesley S, Pai Het al. An updated analysis of the survival endpoints of ASCENDE-RT. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2023; 115: 1061-1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu Y, Nickleach DC, Zhang Cet al. Carrying out streamlined routine data analyses with reports for observational studies: introduction to a series of generic SAS (®) macros. F1000Res 2018; 7: 1955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schaeffer EM, Srinivas S, Adra Net al. Prostate Cancer, Version 4.2023, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2023; 21: 1067-1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Merrick GS, Galbreath RW, Butler WMet al. Primary Gleason pattern does not impact survival after permanent interstitial brachytherapy for Gleason score 7 prostate cancer. Cancer 2007; 110: 289-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ho AY, Burri RJ, Cesaretti JAet al. Radiation dose predicts for biochemical control in intermediate-risk prostate cancer patients treated with low-dose-rate brachytherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2009; 75: 16-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stock RG, Yalamanchi S, Hall SJet al. Impact of hormonal therapy on intermediate risk prostate cancer treated with combination brachytherapy and external beam irradiation. J Urol 2010; 183: 546-550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Merrick GS, Wallner KE, Butler WMet al. 20 Gy versus 44 Gy of supplemental external beam radiotherapy with palladium-103 for patients with greater risk disease: results of a prospective randomized trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2012; 82: e449-455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bittner N, Merrick GS, Butler WMet al. Gleason score 7 prostate cancer treated with interstitial brachytherapy with or without supplemental external beam radiation and androgen deprivation therapy: is the primary pattern on needle biopsy prognostic? Brachytherapy 2013; 12: 14-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tran AT, Mandall P, Swindell Ret al. Biochemical outcomes for patients with intermediate risk prostate cancer treated with I-125 interstitial brachytherapy monotherapy. Radiother Oncol 2013; 109: 235-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Merrick GS, Wallner KE, Galbreath RWet al. Is supplemental external beam radiation therapy essential to maximize brachytherapy outcomes in patients with unfavorable intermediate-risk disease? Brachytherapy 2016; 15: 79-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nguyen PL, Alibhai SM, Basaria Set al. Adverse effects of androgen deprivation therapy and strategies to mitigate them. Eur Urol 2015; 67: 825-836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keyes M, Merrick G, Frank SJet al. American Brachytherapy Society Task Group Report: Use of androgen deprivation therapy with prostate brachytherapy–a systematic literature review. Brachytherapy 2017; 16: 245-265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mohiuddin JJ, Narayan V, Venigalla Set al. Variations in patterns of concurrent androgen deprivation therapy use based on dose escalation with external beam radiotherapy vs. brachytherapy boost for prostate cancer. Brachytherapy 2019; 18: 322-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jackson WC, Hartman HE, Dess RTet al. Addition of androgen-deprivation therapy or brachytherapy boost to external beam radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer: A network meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Clin Oncol 2020; 38: 3024-3031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andruska N, Agabalogun T, Fischer-Valuck BWet al. Assessing the impact of brachytherapy boost and androgen deprivation therapy on survival outcomes for patients with unfavorable intermediate-risk prostate cancer patients treated with external beam radiotherapy. Brachytherapy 2022; 21: 617-625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andruska N, Fischer-Valuck BW, Carmona R, Agabalogun T, Brenneman RJ, Gay HA, et al. Outcomes of patients with unfavorable intermediate-risk prostate cancer treated with external-beam radiotherapy versus brachytherapy alone. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2022; 20: 343-50.e4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mendez LC, Martell K, Warner Aet al. Does ADT benefit unfavourable intermediate risk prostate cancer patients treated with brachytherapy boost and external beam radiotherapy? A propensity-score matched analysis. Radiother Oncol 2020; 150: 195-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smile TD, Tom MC, Halima Aet al. (125)I Interstitial brachytherapy with or without androgen deprivation therapy among unfavorable-intermediate and high-risk prostate cancer. Brachytherapy 2022; 21: 85-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spratt DE, Zhang J, Santiago-Jiménez Met al. Development and validation of a novel integrated clinical-genomic risk group classification for localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 2018; 36: 581-590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hofman MS, Lawrentschuk N, Francis RJet al. Prostate-specific membrane antigen PET-CT in patients with high-risk prostate cancer before curative-intent surgery or radiotherapy (proPSMA): a prospective, randomised, multicentre study. Lancet 2020; 395: 1208-1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table