Abstract

Background

Obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) is a common disease with breathing disturbances during sleep. Sulthiame (STM), a carbonic anhydrase (CA) inhibitor, was recently shown to reduce OSA in a significant proportion of patients. CA activity and hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α are two potential biomarkers reported in severe OSA and hypoxia. Both have been considered to play roles in the development of OSA comorbidities. This study investigated the effects of STM on these biomarkers in OSA.

Methods

This was an exploratory analysis of a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of STM in OSA. Patients with moderate to severe OSA, body mass index 20–35 kg·m−2, aged 18–75 years and not accepting positive airway pressure treatment were randomised to 4 weeks with placebo, STM 200 mg or STM 400 mg. CA activity (n=43) and HIF-1α concentration (n=53) were determined at baseline, after 4 weeks of treatment and 2 weeks after treatment completion.

Results

In the 400 mg group, both CA activity and HIF-1α concentration were reduced (median difference −26% (95% CI −32– −12%) and −4% (95% CI −8– −2%); both p<0.05 versus placebo). The reductions were sustained 2 weeks after treatment completion. In the 200 mg group, both CA activity and HIF-1α were numerically reduced. The STM-induced reductions in CA activity and HIF-1α correlated significantly (r=0.443, p=0.023).

Conclusions

STM treatment in OSA induced a reduction of both CA activity and HIF-1α concentration. The effects remained 2 weeks after treatment completion, suggesting prolonged effects of STM in OSA.

Shareable abstract

The carbonic anhydrase inhibitor sulthiame reduces the hypoxia marker hypoxia-inducible factor-1α and carbonic anhydrase activity in the treatment of OSA. The effects are still evident 2 weeks after drug termination, suggesting prolonged effects in OSA. https://bit.ly/3RtxHdK

Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) is a highly prevalent disease with potentially severe health outcomes [1]. The intermittent apnoeas or hypopnoeas during the sleeping period result in periodic hypoxia and fragmentation of sleep in OSA. Daytime tiredness and cognitive deficiencies represent potentially immediate effects, while increased risks of metabolic and cardiovascular diseases appear to be long-term consequences [2]. The leading treatment for OSA is positive airway pressure (PAP), which effectively reduces breathing disturbances. However, long-term compliance is often incomplete [3]. Other treatment alternatives include oral appliances, upper airway surgery and weight reduction [4, 5]. Novel drug therapies are now under development [6–9]. The carbonic anhydrase (CA) inhibitor sulthiame (STM) was recently shown to be both safe and efficacious for the treatment of OSA in most patients [8, 10].

CA activity in whole blood has been proposed as a biomarker of OSA and its comorbidities. We previously reported elevated activity in severe OSA compared to non-OSA controls [11]. CA activity was also higher in hypertensive compared to normotensive OSA subjects. However, PAP therapy did not reduce the activity [11, 12].

Intermittent hypoxia is likely to be another important trigger in the development of comorbidities in OSA [13–15]. The expression of the transcriptional activator hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1 is a central component in the physiological hypoxic response. The α subunit (HIF-1α) is oxygen sensitive and increased by intermittent hypoxia [16]. Interestingly, several studies have demonstrated higher HIF-1α blood concentration in untreated OSA subjects compared with healthy controls, and the concentration was proportional to OSA severity [17–19]. Other data suggest that PAP treatment reduces blood HIF-1α concentration [19]. HIF-1α increases the production of reactive oxygen species and sensitises the carotid bodies, a proposed pathophysiological pathway for the development of OSA comorbidities including hypertension and impaired glycaemic control [20–22]. The association to comorbidities and OSA severity makes HIF-1α an interesting potential biomarker of the hypoxic consequences in OSA.

The current study investigated the effect of STM on CA activity and HIF-1α concentration in subjects with moderate to severe OSA intolerant to PAP therapy. We hypothesised that STM would reduce CA activity and HIF-1α concentration.

Methods

Study design and population

This is a per protocol tertiary exploratory analysis of a double-blind, randomised controlled dose-escalation trial of STM in OSA. A detailed study outline and results from the primary outcomes have previously been reported [8]. To summarise, inclusion criteria were moderate to severe OSA (mean of two baseline measurements, apnoea–hypopnoea index (AHI) ≥10 events·h−1 in each measurement), body mass index 20–35 kg·m−2, age 18–75 years, Epworth Sleepiness Scale ≥6 and previously not accepting PAP treatment. Exclusion criteria were central sleep apnoea, OSA treatment during the last 4 weeks before the baseline visit, other significant sleep disorders, severe nocturnal hypoxia (>10 episodes of arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2) <50% or incomplete re-saturation (SaO2 ≤90%) between desaturations), uncontrolled hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥160 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥100 mmHg) or a change in antihypertensive medication within the last 4 weeks. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The participants were randomised to either placebo, STM 200 mg or STM 400 mg according to an independently prepared list provided by the contracted clinical research organisation. STM was administered orally, once a day at bedtime. For detailed information regarding dose titration, see the main study [8]. CA activity and HIF-1α concentration were determined at baseline, after 4 weeks of treatment and 2 weeks after treatment completion. Only participants with complete data on CA activity (n=43) and/or HIF-1α (n=53) measurements from all three occasions were included in the current analysis (figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Study flowchart. STM: sulthiame; CA: carbonic anhydrase; HIF-1α: hypoxia-inducible factor-1α.

Sleep assessments

Polysomnography (PSG) was applied during 2 consecutive nights at baseline and at 4-week follow-up with the Embla A10 system (Flaga, Reykjavik, Iceland). The means of the two paired study recordings were used. The PSG setup has been described previously [8], and included electroencephalography, electrooculograms, electromyography at chin and tibia, airflow measurements with nasal canula and oronasal thermistor, thoracoabdominal respiratory movements, body position and SaO2 measurements. The PSG recordings were manually scored by an experienced sleep technician according to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine criteria [23]. An apnoea was defined as a ≥90% drop of the airflow signal from baseline lasting ≥10 s. A hypopnoea was defined as a drop of the airflow signal of ≥50% from baseline lasting ≥10 s, with an associated desaturation ≥3% or an EEG arousal. The oxygen desaturation index (ODI) was computed as the number of ≥4% oxygen desaturations per hour of sleep.

Biochemical analysis

Blood samples were collected from an antecubital vein in the morning after sleep study 1 (baseline) and sleep study 3 (4-week follow-up) in addition to the follow-up visit after treatment completion. The whole-blood samples for CA activity analysis were collected in heparinised tubes and frozen at −80 °C. Samples were thawed followed by three pipetting/vortexing sequences prior to the analysis of CA activity. The serum samples for HIF-1α analysis were coagulated at room temperature and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min. The serum was then separated and stored at −80 °C. All experiments for CA activity and HIF-1α assays were run in duplicate.

CA activity

CA activity analysis procedures followed the protocol specified in the commercially available assay kit (K472-100; BioVision, Milpitas, CA, USA). The esterase activity of CA enzymes on an esterase substate, compared to a nitrophenol standard, was spectrophotometrically quantified via measurement of the released chromophore at 405 nm using a spectrophotometer (SpectraMax i3x; Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA). With this technique, the overall activity of all CA isozymes in the sample is measured. The results are presented as the maximal rate of CA enzymatic activity over time (Vmax). The CA inhibitor acetazolamide was used as a negative control. The activity quantification was performed in 96-well microtitre plates with technical duplicates and read at 405 nm in an end-point mode. Due to the high concentration of CA enzyme in erythrocytes, CA activity was normalised to the individual haemoglobin level in the sample if not otherwise stated.

HIF-1α concentration

Serum samples were used for sandwich ELISA to determine HIF-1α concentration (ng·mL−1) with a commercially available kit (DYC1935-2; Bio-Techne, Minneapolis, MN, USA). The assay was performed according to the ELISA kit protocol.

Statistical analysis

Normally distributed data are presented as mean with standard deviation, categorical data as number (percentage) and non-normally distributed data as median (interquartile range) or median (95% confidence interval). Distribution of data was determined by visual inspection of histograms and the Shapiro–Wilk test (p≤0.05). Changes between baseline, during treatment and after treatment completion were analysed with the Kruskal–Wallis H-test due to the non-normal data distribution. If the Kruskal–Wallis H-test was significant, pairwise comparisons were conducted using Dunn's procedure. Differences between two groups were analysed with the t-test (normal distribution) or Mann–Whitney U-test (non-normal distribution). Correlations were analysed with Pearson's correlation coefficient (normal distribution without significant outliers) or Spearman's rank correlation coefficient (non-normal distribution and/or significant outliers). 95% confidence intervals for medians were calculated with a bootstrap method with 1000 iterations. Results were considered statistically significant if p≤0.05. Due to the exploratory study design, results were not adjusted for multiple comparisons. The statistical analyses were performed with SPSS Statistics version 29 for Macintosh (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

Ethics and formal requirements

This study was approved by the regional research ethics committee at Gothenburg University (045-18) and the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (2020-06237). The original clinical trial was registered in the EU Clinical Trials Register (2017-004767-13).

Results

Cohort characteristics

A total of 43 and 53 participants had full sets of CA activity and HIF-1α concentration measurements including baseline, end of treatment and 2 weeks after treatment completion, respectively (figure 1). The anthropometric and clinical data for both analysis cohorts are shown in tables 1 and 2 (CA activity and HIF-1α concentration, respectively). Patients were predominately males, aged >60 years and overweight. The participants had mainly severe OSA; CA activity cohort: mean±sd AHI 54±22 events·h−1 (range 15–92 events·h−1) and HIF-1α cohort: mean±sd AHI 55±23 events·h−1 (range 15–109 events·h−1). Blood pressures and degree of cardiometabolic comorbidities were comparable between groups (tables 1 and 2).

TABLE 1.

Anthropometrics, comorbidities and obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) severity in the carbonic anhydrase (CA) activity cohort

| Full cohort (n=43) | Placebo (n=15) | STM 200 mg (n=8) | STM 400 mg (n=20) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anthropometrics | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 30 (70) | 11 (73) | 5 (63) | 14 (70) |

| Female | 13 (30) | 4 (27) | 3 (37) | 6 (30) |

| Age (years) | 61±10 | 60±11 | 63±10 | 60±10 |

| Weight (kg) | 85±13 | 89±14 | 82±11 | 83±12 |

| BMI (kg·m−2) | 28±3 | 29±3 | 27±3 | 27±3 |

| Waist/hip ratio | 1 (0.9–1) | 0.8 (0.9–1) | 1 (0.9–1) | 1 (0.9–1) |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension | 17 (40) | 3 (20) | 6 (75) | 8 (40) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 133±13 | 134±12 | 136±12 | 131±15 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 81±9 | 80±5 | 85±8 | 80±11 |

| Diabetes mellitus type 2 | 2 (5) | 1 (7) | 0 | 1 (5) |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 1 (2) | 1 (7) | 0 | 0 |

| OSA | ||||

| AHI (events·h−1) including range | 54±22 (15–92) | 51±22 (19–83) | 56±22 (15–88) | 55±23 (22–92) |

| ODI (events·h−1) | 34±22 | 34±23 | 32±23 | 34±22 |

| Mean oxygen saturation (%) | 93±2 | 93±2 | 92±2 | 94±2 |

| Time in <90% oxygen saturation (%TST) | 10±14 | 12±18 | 17±15 | 6±11 |

| Minimum oxygen saturation (%) | 79±7 | 80±6 | 74±10 | 80±6 |

| CA activity# | 16±6.9 | 14.8±6.4 | 16.9±6.0 | 16.6±7.8 |

| CA activity#, haemoglobin adjusted | 0.11±0.05 | 0.10±0.05 | 0.11±0.04 | 0.11±0.06 |

Data are presented as n (%), mean±sd or median (interquartile range), unless otherwise stated. BMI: body mass index; AHI: apnoea–hypopnoea index; ODI: oxygen desaturation index; TST: total sleep time. #: see Methods for details of CA activity analysis.

TABLE 2.

Anthropometrics, comorbidities and obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) severity in the hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) concentration cohort

| Full cohort (n=53) | Placebo (n=22) | STM 200 mg (n=7) | STM 400 mg (n=24) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anthropometrics | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 38 (72) | 17 (77) | 4 (57) | 17 (71) |

| Female | 15 (28) | 5 (23) | 3 (43) | 7 (29) |

| Age (years) | 60±10 | 61±10 | 60±11 | 60±9 |

| Weight (kg) | 85±13 | 89±12 | 83±12 | 82±14 |

| BMI (kg·m−2) | 28±3 | 29±3 | 29±3 | 26±3 |

| Waist/hip ratio | 1 (0.9–1) | 1 (0.9–1) | 1 (0.9–1) | 1 (0.9–1) |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension | 20 (38) | 6 (27) | 5 (71) | 9 (38) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 133±13 | 134±11 | 134±12 | 131±14 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 82±9 | 81±6 | 87±8 | 80±11 |

| Diabetes mellitus type 2 | 3 (6) | 2 (9) | 0 | 1 (4) |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 5 (9) | 3 (14) | 0 | 2 (8) |

| OSA | ||||

| AHI (events·h−1) including range | 55±23 (15–109) | 54±21 (19–91) | 64±30 (15–109) | 54±22 (22–92) |

| ODI (events·h−1) | 35±22 | 35±21 | 41±29 | 33±20 |

| Mean oxygen saturation (%) | 93±2 | 93±2 | 92±2 | 94±2 |

| Time in <90% oxygen saturation (% TST) | 11±14 | 12±17 | 19±14 | 6±10 |

| Minimum oxygen saturation (%) | 78±8 | 79±8 | 72±8 | 80±6 |

| HIF-1α concentration (ng·mL−1) | 9.4 (8.1–9.9) | 9.4 (8.1–9.7) | 11.3 (10–18.3) | 9 (8–9.7) |

Data are presented as n (%), mean±sd or median (interquartile range), unless otherwise stated. BMI: body mass index; AHI: apnoea–hypopnoea index; ODI: oxygen desaturation index; TST: total sleep time.

STM reduced CA activity and HIF-1α concentration

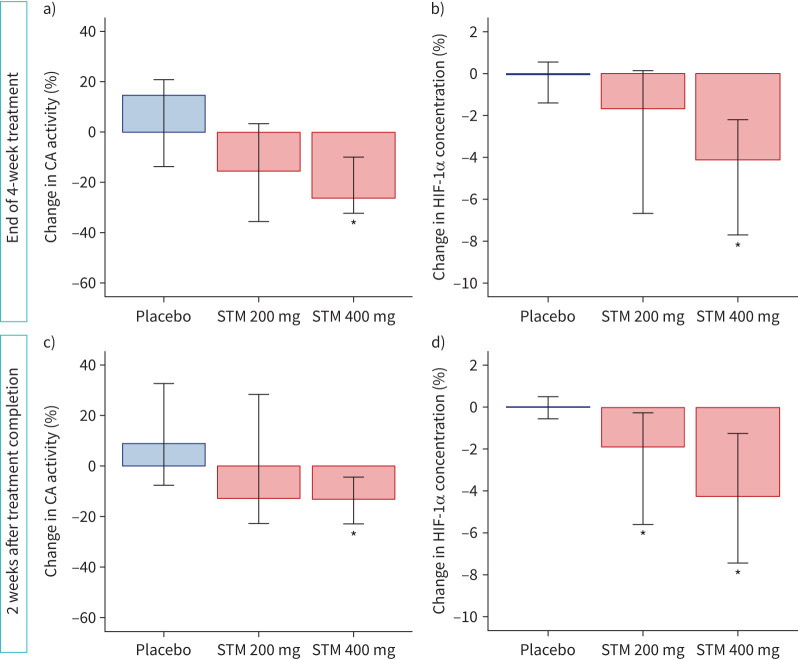

The CA activity differed significantly between groups at end of treatment (Kruskal–Wallis H-test p=0.016). Pairwise comparisons showed that CA activity was significantly reduced compared with placebo in the STM 400 mg group (median change −26% (95% CI −32– −12%); p=0.004 versus placebo). For the STM 200 mg group, a numerical, but not statistically significant, difference was seen versus both the STM 400 mg and placebo groups (figure 2a). At 2 weeks after treatment completion there were still significant differences between study groups (Kruskal–Wallis H-test p=0.019). The STM 400 mg group had reduced levels of CA activity compared to placebo, although the difference was smaller (median change −13% (95% CI −23– −5%); p=0.005) (figure 2c). Absolute and unadjusted changes are presented in supplementary table S1.

FIGURE 2.

Changes in a, c) whole-blood carbonic anhydrase (CA) activity and b, d) hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) concentration a, b) during treatment and c, d) 2 weeks after treatment completion. Data are presented as median (95% CI) change versus baseline. *: statistical significance (p≤0.05) versus placebo. Kruskal–Wallis H-test with pairwise comparisons.

The HIF-1α concentration also differed between groups at end of treatment (Kruskal–Wallis H-test p<0.001). In pairwise comparisons, HIF-1α concentration was significantly reduced during STM treatment in the 400 mg group (median difference −4% (95% CI −8– −2%); p<0.001 versus placebo) whereas the difference to placebo did not reach statistical significance in the 200 mg group (figure 2b). The reduced HIF-1α concentration in the 400 mg group was maintained 2 weeks after treatment completion (difference between groups Kruskal–Wallis H-test p=0.002; pairwise comparisons 400 mg: −4% (95% CI −7– −2%); p<0.001 versus placebo) (figure 2d). A significant persistent reduction was also seen in the STM 200 mg group after treatment completion (−2% (95% CI −6– −0.4%); p=0.027 versus placebo). Absolute changes are presented in supplementary table S2.

The reductions in CA activity and HIF-1α concentration were correlated at an individual level during STM treatment (Pearson r=0.443, p=0.023) (figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Changes in hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) concentration in relation to changes in carbonic anhydrase (CA) activity at end of treatment. STM: sulthiame. Pearson correlation r=0.443, R2=0.210, p=0.023. Dotted lines indicate 95% CI of regression line.

Associations between biomarkers and sleep apnoea indices at baseline

The individual baseline CA activity or HIF-1α concentration did not correlate to the degree of OSA-induced hypoxia during sleep (ODI, mean SaO2 or time under 90% SaO2), venous carbon dioxide tension, AHI or blood pressure. Likewise, there was no association between hypertension diagnosis and CA activity or HIF-1α concentration (data not shown).

Associations between STM-induced changes in biomarkers and sleep apnoea indices at end of treatment

Group-level data suggested a covariance between changes of CA activity and HIF-1α concentration and OSA severity measures. In the full cohort analysis (placebo and STM-treated subjects), both CA activity and HIF-1α concentration changes were correlated to the change in mean SaO2 (CA activity: Spearman r= −0.341 and HIF-1α concentration: Spearman r= −0.273; both p<0.05) but not to AHI (figure 4). We could not identify significant correlations between changes in CA activity, HIF-1α concentration and changes in OSA measurements (AHI and mean SaO2) for the STM 200 mg and 400 mg dose groups separately (figure 4). There were no correlations between change in CA activity or HIF-1α concentration and changes in ODI or sleep time spent below 90% SaO2 (supplementary figures S1 and S2). OSA severity measurements at end of treatment are presented in supplementary tables S3 and S4.

FIGURE 4.

Changes in a, b) hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) concentration and c, d) carbonic anhydrase (CA) activity in relation to changes in a, c) apnoea–hypopnoea index (AHI) and b, d) mean arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2) during sulthiame (STM) treatment and placebo. Shaded area defines reduction of OSA indices and HIF-1α concentration or CA activity.

Discussion

Our study demonstrated that STM reduced both CA activity and HIF-1α concentration in a dose-dependent manner and that there was a correlation between the changes in biomarkers. Further, the improvement of overnight mean SaO2 after STM correlated with the reduction of the biomarkers. The decrease in HIF-1α concentration adds to the previously reported improvement of ventilation by STM and suggests the presence of significant hypoxia in the cohort, despite the relatively high baseline mean SaO2. In addition, the sustained effects on CA activity and HIF-1α concentration, at least 2 weeks after treatment completion, indicate prolonged effects following the administration of STM. Overall, the findings suggest that STM reduces hypoxia, not only in terms of measures of sleep disordered breathing, but also as shown by the underlying regulatory mechanisms related to intermittent hypoxia during sleep.

STM 400 mg reduced CA activity in whole blood after 4 weeks of treatment. In the lower dose group, the reductions did not reach statistical significance. This is line with a previously reported trend towards a reduction of CA activity following CA inhibition by acetazolamide whereas no change in CA activity was observed following PAP treatment [12]. In addition to these results, previous data on the degree of CA activity reduction in OSA by CA inhibition are sparse. Our research group previously reported a study on CA activity and OSA severity, with higher activity levels in severe OSA compared to no OSA (n=70) [11]. These findings were not replicated in the current study, possibly due to the narrower OSA severity spectrum with mainly severe cases included. Hence, it remains unclear if CA activity is reduced from elevated or normal physiological levels. Recent data in healthy subjects from our laboratory show that physiological levels of CA activity are also reduced after CA inhibition. Interestingly, the STM-induced reductions in CA activity were correlated with the changes in HIF-1α concentration (figure 3).

The mechanisms behind the reduction of HIF-1α concentration remain to be fully explained, but may include a sustained reduction of hypoxic load, as previously suggested in an observational 2-month study of PAP treatment [19]. However, interventional data from a single-night trial with PAP suggested no change in HIF-1α levels in patients with OSA [24]. Whether a 4% reduction in HIF-1α concentration is clinically relevant remains unknown, but the results suggest a reduction of overall hypoxia. The correlation between the change in CA activity and HIF-1α concentration during treatment suggests a more direct relationship between these markers, but the causality and specific pathways (direct effects and/or indirect effects via hypoxia reduction) need to be further investigated. In addition, previous studies have suggested the inverse relationship in which HIF-1α acts as a transcriptional factor for CA IX in tumour cells [25, 26]. If this relation is valid for other CA isoforms and in OSA remains unknown.

In this cohort, no correlation was seen between baseline HIF-1α concentration and OSA severity. However, as previously discussed, the cohort did not include those with mild or no OSA, thereby not allowing an analysis of the full spectrum of OSA. An earlier study showed a higher HIF-1α concentration in OSA patients compared to no OSA controls (n=60+24) but no differences were identified between the OSA severity groups [27]. However, a large study (n=368) investigating HIF-1α mRNA in plasma showed higher levels with increased OSA severity, although with a considerable overlap between groups and low correlation coefficients [18].

The reduction in CA activity was associated with changes in mean SaO2 in the full cohort analysis, but not in the respective dose groups of STM-treated subjects. The high variability in CA activity provides a potential reason as to why we could not show a correlation. It is also possible that the whole-blood CA activity does not directly, or only in part, relate to the OSA pathophysiology. As mentioned earlier, data in this field are sparse and the mechanistic pathway of CA inhibition in OSA remains insufficiently understood. Measurements of CA activity in whole blood may not fully reflect the underlying physiology. Similar to CA activity, the reduction of HIF-1α concentration did not correlate to changes in OSA severity measures when using the STM-treated subgroup. However, on the full cohort level, with all study subjects, we identified an association and correlation between the response in HIF-1α and mean SaO2 (figure 4). This strengthens a potential link between OSA-induced hypoxaemia and the biomarkers.

The reductions of CA activity and HIF-1α concentration were still evident 2 weeks after completion of STM treatment, albeit to a lower degree. This finding suggests a considerable functional pharmacodynamic half-life of STM. However, the reported pharmacokinetic half-life of STM varies considerably. While May et al. [28] reported a serum half-life of 9 h, a more recent pharmacokinetic study reported a plasma half-life of 51–91 h, depending on dosage, and a terminal half-life of up to 13 days, a finding attributed to a two-compartment kinetic model characterised by a high erythrocyte affinity [29]. The half-life of STM was not determined in the current study but the sustained changes at the 2-week follow-up after treatment completion suggest that the functional half-life may be prolonged.

In this study, we did not find any significant associations between HIF-1α concentration or CA activity and OSA comorbidities. However, the trial was not designed and powered for these specific analyses. The treatment length was short, and the included participants were relatively healthy in terms of cardiovascular and metabolic disease. Several studies have suggested that HIF-1α is an important factor in the development of cardiometabolic OSA comorbidities such as insulin resistance, fatty liver disease and atherosclerosis [20, 30, 31]. A reduction of HIF-1α could also potentially reduce hypoxia-induced carotid body sensitisation, a proposed pathway for comorbid hypertension development in OSA [22]. A previous study showed that CA inhibition had antihypertensive effects in OSA and that CA activity was elevated in untreated hypertensive OSA patients [12, 32]. Hence, it remains to be investigated if STM-induced reduction of blood CA activity and/or HIF-1α concentration is clinically useful for the prevention of OSA-related comorbidities.

This study has both strengths and limitations. Strengths include a well-defined cohort from a randomised controlled trial, a follow-up after drug treatment completion and inclusion of participants who had not used any OSA treatment within 4 weeks of baseline. However, there were also some limitations. The trial was not designed to specifically address CA activity and HIF-1α concentration and may therefore, due to the considerable variability in both biomarkers, be underpowered. Our data may provide the rationale for designing future studies of these biomarkers. The blood samples were drawn at different time-points in relation to awakening, in the morning at baseline and during treatment, and during daytime at the follow-up after treatment completion. Since HIF-1α degradation is oxygen dependent, a sample from later in the day may theoretically have a reduced concentration due to the longer time with normoxia. However, no difference was seen between measurements in the placebo group, suggesting this was not the case. Previous studies have used different methods for measurement of CA activity and HIF-1α blood concentration, making comparisons with other datasets more difficult. We therefore used the percentage change in our main analyses, to account for baseline values. The homogenous cohort with mostly severe OSA prevented correlations to different OSA severities and limited the possibility to explore a potential usefulness of CA activity and/or HIF-1α concentration as biomarkers for the hypoxic component of OSA. It should be acknowledged that measurement of the transcription factor HIF-1α in serum has limited documentation in OSA and further studies are needed to understand its potential usefulness. We still lack a complete understanding of the physiological mechanisms in the response to intermittent hypoxia in OSA and the effects of STM. Future studies need to include larger cohorts with the entire spectrum of hypoxic load associated with OSA.

Conclusions

It is concluded that STM reduces CA activity and HIF-1α concentration in addition to the improvement of OSA. The effects remained 2 weeks after treatment completion, suggesting prolonged effects of STM.

Supplementary material

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material 00342-2024.SUPPLEMENT (574.6KB, pdf)

Acknowledgements

The excellent clinical work of study registered nurses Lena Engelmark and Anna Björntorp, as well as sleep technician Karl Theliander, in this study is gratefully acknowledged (all at the Centre for Sleep and Vigilance Disorders, Department of Internal Medicine and Clinical Nutrition, Institute of Medicine, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden). Thanks to David G. Cameron for proofreading the original manuscript.

Provenance: Submitted article, peer reviewed.

The original clinical trial was registered at EU Clinical Trials Register with identifier number 2017-004767-13.

Ethics statement: This study was approved by the regional research ethics committee at Gothenburg University (045-18) and the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (2020-06237).

Author contributions: E. Hoff: conceptualisation, investigation, data analysis and statistics, interpretation, writing (original draft), project administration, and funding acquisition. S. Musovic: conceptualisation, investigation, biochemical analyses, validation, interpretation and writing (review and editing). A.M. Komai: conceptualisation, investigation, biochemical analyses, validation, interpretation and writing (review and editing). D. Zhou: conceptualisation, interpretation, writing (review and editing) and supervision. C. Strassberger: investigation, data analysis and statistics, and writing (review and editing). K. Stenlöf: conceptualisation, resources, writing (review and editing) and funding acquisition. L. Grote: conceptualisation, resources, interpretation, writing (review and editing), funding acquisition and supervision. J. Hedner: conceptualisation, resources, interpretation, writing (review and editing), funding acquisition and supervision.

Conflict of interest: E. Hoff, S. Musovic, A.M. Komai, D. Zou and C. Strassberger report no conflicts of interest. K. Stenlöf, L. Grote and J. Hedner are part owners of two patents related to sleep apnoea therapy. L. Grote reports speaker's bureaus for ResMed Inc., Philips, Lundbeck and AstraZeneca outside the scope of the current work. J. Hedner participated in a data safety monitoring board for Respicardia. L. Grote and J. Hedner received unrestricted grants on behalf of the ESADA group from ResMed Inc. and Philips Respironics, and research grants from Bayer Pharma and Desitin GmbH.

Support statement: Desitin Arzneimittel (Hamburg, Germany) provided funding for the original randomised trial and supported the post hoc analysis. Institutional grants were provided by the Swedish State Funds for Clinical Research LUA/ALF grant ALFGBG-721251, and the Swedish Heart and Lung Foundation grants 20180585 and 20210500. The PhD studies of E. Hoff were supported by the Local Research and Development Board Södra Älvsborg, and the Gothenburg Medical Society. Funding information for this article has been deposited with the Crossref Funder Registry.

Data availability

The data are available on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Benjafield AV, Ayas NT, Eastwood PR, et al. Estimation of the global prevalence and burden of obstructive sleep apnoea: a literature-based analysis. Lancet Respir Med 2019; 7: 687–698. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30198-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gottlieb DJ, Punjabi NM. Diagnosis and management of obstructive sleep apnea. JAMA 2020; 323: 1389–1400. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rotenberg BW, Murariu D, Pang KP. Trends in CPAP adherence over twenty years of data collection: a flattened curve. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2016; 45: 43. doi: 10.1186/s40463-016-0156-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johansson K, Neovius M, Lagerros YT, et al. Effect of a very low energy diet on moderate and severe obstructive sleep apnoea in obese men: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2009; 339: b4609. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b4609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Randerath W, Verbraecken J, De Raaff CAL, et al. European Respiratory Society guideline on non-CPAP therapies for obstructive sleep apnoea. Eur Respir Rev 2021; 30: 210200. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0200-2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taranto-Montemurro L, Messineo L, Wellman A. Targeting endotypic traits with medications for the pharmacological treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. A review of the current literature. J Clin Med 2019; 8: 1846. doi: 10.3390/jcm8111846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaisl T, Haile SR, Thiel S, et al. Efficacy of pharmacotherapy for OSA in adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev 2019; 46: 74–86. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2019.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hedner J, Stenlöf K, Zou D, et al. A randomized controlled trial exploring safety and tolerability of sulthiame in sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2022; 205: 1461–1469. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202109-2043OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hedner J, Zou D. Turning over a new leaf – pharmacologic therapy in obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Med Clin 2022; 17: 453–469. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2022.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoff E, Strassberger C, Zou D, et al. Modification of endotypic traits in obstructive sleep apnea by the carbonic anhydrase inhibitor sulthiame. Chest 2023; 165: 704–715. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2023.09.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang T, Eskandari D, Zou D, et al. Increased carbonic anhydrase activity is associated with sleep apnea severity and related hypoxemia. Sleep 2015; 38: 1067–1073. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoff E, Zou D, Schiza S, et al. Carbonic anhydrase, obstructive sleep apnea and hypertension: effects of intervention. J Sleep Res 2020; 29: e12956. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turnbull CD. Intermittent hypoxia, cardiovascular disease and obstructive sleep apnoea. J Thorac Dis 2018; 10: Suppl. 1, S33–S39. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2017.10.33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stranks EK, Crowe SF. The cognitive effects of obstructive sleep apnea: an updated meta-analysis. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 2016; 31: 186–193. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acv087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fernandes M, Placidi F, Mercuri NB, et al. The importance of diagnosing and the clinical potential of treating obstructive sleep apnea to delay mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease: a special focus on cognitive performance. J Alzheimers Dis Rep 2021; 5: 515–533. doi: 10.3233/ADR-210004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luo Z, Tian M, Yang G, et al. Hypoxia signaling in human health and diseases: implications and prospects for therapeutics. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2022; 7: 218. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-01080-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gabryelska A, Szmyd B, Szemraj J, et al. Patients with obstructive sleep apnea present with chronic upregulation of serum HIF-1α protein. J Clin Sleep Med 2020; 16: 1761–1768. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.8682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu C, Wang H, Zhu C, et al. Plasma expression of HIF-1α as novel biomarker for the diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome. J Clin Lab Anal 2020; 34: e23545. doi: 10.1002/jcla.23545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu D, Li N, Yao X, et al. Potential inflammatory markers in obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome. Bosn J Basic Med Sci 2016; 17: 47–53. doi: 10.17305/bjbms.2016.1579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gabryelska A, Karuga FF, Szmyd B, et al. HIF-1α as a mediator of insulin resistance, T2DM, and its complications: potential links with obstructive sleep apnea. Front Physiol 2020; 11: 1035. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2020.01035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prabhakar NR, Peng YJ, Nanduri J. Hypoxia-inducible factors and obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Invest 2020; 130: 5042–5051. doi: 10.1172/JCI137560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iturriaga R, Alcayaga J, Chapleau MW, et al. Carotid body chemoreceptors: physiology, pathology, and implications for health and disease. Physiol Rev 2021; 101: 1177–1235. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00039.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berry RB, Brooks R, Gamaldo C, et al. AASM Scoring Manual updates for 2017 (Version 2.4). J Clin Sleep Med 2017; 13: 665–666. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gabryelska A, Stawski R, Sochal M, et al. Influence of one-night CPAP therapy on the changes of HIF-1α protein in OSA patients: a pilot study. J Sleep Res 2020; 29: e12995. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaluz S, Kaluzová M, Liao S-Y, et al. Transcriptional control of the tumor- and hypoxia-marker carbonic anhydrase 9: a one transcription factor (HIF-1) show? Biochim Biophys Acta 2009; 1795: 162–172. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2009.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wykoff CC, Beasley NJ, Watson PH, et al. Hypoxia-inducible expression of tumor-associated carbonic anhydrases. Cancer Res 2000; 60: 7075–7083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gabryelska A, Szmyd B, Panek M, et al. Serum hypoxia-inducible factor-1α protein level as a diagnostic marker of obstructive sleep apnea. Pol Arch Intern Med 2020; 130: 158–160. doi: 10.20452/pamw.15104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.May TW, Korn-Merker E, Rambeck B, et al. Pharmacokinetics of sulthiame in epileptic patients. Ther Drug Monit 1994; 16: 251–257. doi: 10.1097/00007691-199406000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dao K, Thoueille P, Decosterd LA, et al. Sultiame pharmacokinetic profile in plasma and erythrocytes after single oral doses: a pilot study in healthy volunteers. Pharmacol Res Perspect 2020; 8: e00558. doi: 10.1002/prp2.558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mesarwi OA, Moya EA, Zhen X, et al. Hepatocyte HIF-1 and intermittent hypoxia independently impact liver fibrosis in murine nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2021; 65: 390–402. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2020-0492OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thomas C, Leleu D, Masson D. Cholesterol and HIF-1α: dangerous liaisons in atherosclerosis. Front Immunol 2022; 13: 868958. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.868958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eskandari D, Zou D, Grote L, et al. Acetazolamide reduces blood pressure and sleep-disordered breathing in patients with hypertension and obstructive sleep apnea: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Sleep Med 2018; 14: 309–317. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material 00342-2024.SUPPLEMENT (574.6KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

The data are available on reasonable request.