Abstract

Background

Tongue squamous cell carcinoma (TSCC) is one of the most common malignant tumors with high mortality and poor prognosis. Its incidence rate is increasing gradually. Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor interacting protein (TRAIP), as a factor related to several tumors, reveals that its gene expression is different between normal tissue and primary tumor of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma using bioinformatics analysis.

Method

In our study, TCGA database, immunohistochemistry, proliferation assay, colony formation, wound healing assay, Transwell, cell cycle analysis and tumor xenografts model were used to determine the expression and functions of TRAIP in TSCC.

Result

We found that TRAIP may promote the proliferation, migration and invasion of TSCC. Furthermore, the results of bioinformatics analysis, mass spectrometry and co-immunoprecipitation suggested that DDX39A may be a TRAIP interacting protein. DDX39A has been proven to be an oncogene in several tumors, which may have an important effect on cell proliferation and metastasis in multiple tumors. In addition, the high expression of DDX39A implies the poor prognosis of patients. Our study demonstrated that TRAIP probably interact with DDX39A to regulate cell progression through epithelial-mesenchymal transition and Wnt/β-catenin pathway. In addition, we show that the necessary domain of DDX39A for the interaction between DDX39A and TRAIP region.

Conclusion

These results indicate that TRAIP is important in occurrence and development of TSCC and is expected to become the new promising therapeutic target.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12885-024-13130-8.

Keywords: TRAIP, Progression, Tongue squamous cell carcinoma, Wnt/β-catenin signaling, EMT, DDX39A

Introduction

Oral cancer is a highly prevalent cancer worldwide, and more than 90% of the cases are squamous cell carcinoma [1], which is the most common malignant tumor of the head and neck [2]. Tongue cancer is a branch of head and neck cancer. The incidence rate of tongue squamous cell carcinoma (TSCC) gradually increases, especially in young patients [3]. Many cases were diagnosed in advanced stage because of lack of symptoms [4]. Early regional lymph nodes metastasis and unsatisfactory chemotherapeutic treatment are also related to high mortality. Despite various treatments, the long-term prognosis of TSCC is poor, and the 5 year survival rate is about 50%. The survivors also have many severe disabilities, such as swallowing and speech disorders [5]. Therefore, finding effective targeted therapeutic molecules to TSCC is urgently needed.

Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor interacting protein (TRAIP) is a ring-dependent E3 ubiquitin ligase, it’s a 53-kDa protein, with a 55-aminoacid-long ring domain at its N-terminal end, a putative coiled-coil domain and a leucine zipper region [6]. Through bioinformatic analysis, we found that the expression of TRAIP in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSC) was remarkably higher than that of normal tissues. Previous reports have pointed that TRAIP involves cell progression of many tumors [7–10]. TRAIP is highly expressed in liver cancer, and such overexpression encouraged malignant behavior of liver cancer cells [7]. In a previous study, TRAIP defective homozygous mouse died in the early embryonic stage because of proliferation defect and excessive cell death [11]. The overexpression of TRAIP enhanced the proliferation, metastasis, and invasion ability of lung cancer cells [8]. Interacting with CYLD, TRAIP serves as a tumor suppressor in basal cell carcinoma. TRAIP improves the invasion and proliferation abilities of osteosarcoma and triple negative breast cancer [9, 10]. Therefore, we hypothesize that TRAIP may be a new target in TSCC. However, no research has been conducted on the relationship between TRAIP and TSCC. Bioinformatics is a field that uses mathematics, information technology, statistics and computer science to research biological questions. At present, several bioinformatics databases can be used to analyze proteins sequence, structure and functions [12].

Therefore, we used bioinformatics to analyze the relationship between TRAIP and TSCC, and to verify the results. Our study found that TRAIP regulated the proliferation and invasion of TSCC cells by interacting with DDX39A. Previous studies have indicated that TRAIP promotes tumor cell growth and metastasis through epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [10]. The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is critically involved in the regulation of EMT in tumor cells [13]. However, the interaction between TRAIP and the Wnt pathway has not been empirically validated to date. The Wnt signaling pathway and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) play important roles in the progression of oral cancer [14]. Therefore, we further investigated the relationship among TRAIP, DDX39A, Wnt/β-catenin and EMT. These results indicate that TRAIP may be a new potential target in TSCC treatment.

Materials and methods

TRAIP gene expression analysis

We obtained the expression of TRAIP in different normal tissues from the Human Protein Atlas (HPA) database (https://www.proteinatlas.org/) [15]. Unpaired and paired HNSC data from TCGA database joint GTEx database and one datasets (GSE160042 [16]) containing TSCC tissue and normal tissue samples from Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) were analyzed and boxplots were drawn. The pROC [17] package and ggplot2 package were used for plotting ROC curve. We obtained the variation information of TRAIP in patients with HNSC from TCGA database by using cBioPortal (https://www.cbioportal.org/). Data sampling was performed using the genome database updated as of 2023.

Enrichment analysis

TRAIP expression levels were grouped (transcripts per million (TPM) data, Low TRAIP: 0-50%. High TRAIP: 50-100%) and differential analysis was performed using DESeq2 [18] package to obtain differential genes, screen protein coding genes and draw volcano maps. GSEA was analyzed by using clusterProfiler [19] package (the number of calculations was 10000, and the gene set ranged from 10 to 1000, p.adj < 0.05, FDR < 0.2, |NES| > 1.8, species: homo sapiens).

TRAIP downstream molecular screening

Through the same processing as before, the mass spectrometry, HNSC-related differential genes and TRAIP-related differential genes were intersected to obtain the genes that were simultaneously related to HNSC and TRAIP and were screened in the mass spectrometry. TRAIP related proteins were obtained by co-immunoprecipitation (CO-IP), and then the samples were used for mass spectrometry test. The mass spectrometry was finished by Shanghai OE Biotechnology Company (Shanghai, China). The results are shown in supplementary material (Table S3 and S4). We selected several genes related to cancer cell proliferation and invasion from the mass spectrometry results. These genes were input into the STRING (https://string-db.org/) for molecular interaction analysis. The heatmap and scatter plot of the correlation between these genes and TRAIP were drawn by ggplot2. These results suggested that TRAIP may interact with other genes in TSCC, which need further verification.

Specimens and cell culture

Sixty-five TSCC tissues, corresponding adjacent normal tissues and related clinical characteristics (Table 1) were collected at the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University between 2014 and 2016. Specimens from cancer tissue and adjacent normal tissue were obtained during surgery and were immediately dipped in 10% formalin for immunohistochemistry (IHC). No patients received radiotherapy or chemotherapy before surgery. Nine pairs of fresh cancer and adjacent tissue collected at the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored for protein analysis. All patients have signed the informed consent document. The study was approved by the Institutional Medical Ethics Committee of the Qingdao University Affiliated Hospital.

Table 1.

Association between TRAIP in human TSCC and patient characteristics

| Variables | n | Mean ± SD | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Female | 27 | 5.852 ± 0.770 | 0.518 |

| Male | 38 | 6.158 ± 0.823 | |

| Age | |||

| ≤60 years | 40 | 6.075 ± 0.798 | 0.128 |

| > 60 years | 25 | 5.960 ± 0.841 | |

| Clinical stage | |||

| I, II | 50 | 5.820 ± 0.774 | 0.001** |

| III, IV | 15 | 6.733 ± 0.458 | |

| Carcinoma | 65 | 6.031 ± 0.810 | < 0.001*** |

| Adjacent tissues | 65 | 5.523 ± 0.752 | |

| Gross type | |||

| Exophytic | 25 | 6.040 ± 0.735 | 0.317 |

| Ulcerative | 23 | 6.043 ± 0.825 | 0.705 |

| Endophytic | 17 | 6.000 ± 0.935 | 0.655 |

| Differentiation# | |||

| Well | 18 | 5.222 ± 0.647 | 0.001** |

| Moderate | 24 | 6.208 ± 0.658 | 0.124 |

| Poor | 23 | 6.478 ± 0.593 | < 0.001*** |

| Tumor recurrence | |||

| Positive | 10 | 6.500 ± 0.527 | 0.014* |

| Negative | 55 | 5.946 ± 0.826 | |

| Lymph node metastasis | |||

| Positive | 17 | 6.353 ± 0.493 | 0.002** |

| Negative | 48 | 5.938 ± 0.885 | |

* Significant at < 0.05; ** Significant at < 0.01; *** Significant at < 0.001. # Differentiation: well vs. moderate, p = 0.001; moderate vs. poor, p = 0.124; well vs. poor, p < 0.001

Human TSCC cell lines were obtained from Culture Collection of Chinese Academy of Science (Shanghai, China). CAL27 is known to be an adenosquamous cell carcinoma, in the following decades after CAL 27 cell line was established, it has been widely used to build OSCC models for studies in vitro and in vivo and thus regarded as a representative cell line for OSCC studying. All cell lines were tested and characterized using STR profiles and were regularly evaluated for mycoplasma. The cells were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Gibco, New York, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Transgen Biotech, Beijing, China), penicillin (100 units/ml) and streptomycin(100 mg/ml) at 37℃ in 5% CO2.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

The operating steps of IHC staining were introduced previously [20]. After deparaffinization and hydration, the slides were inactivated endogenous peroxidase by using 3% hydrogen peroxide and heat-pretreated in ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid (pH 8.0) for 5 min by using a microwave oven. Then the anti-TRAIP antibody (Abcam, United Kingdom, dilution at 1:300, 4 °C, overnight) and the sheep anti-rabbit antibody (Abcam, dilution at 1:100, 37 °C, 30 min) were incubated. Sections thickness was set at 4 μm, stained with diaminobenzidine (DAB) and counterstained with hematoxylin. Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) acts as negative control (NC). The results of IHC staining were scored in accordance with staining intensity and percentage of positive tumor cells. The total score contains the staining intensity (0, none; 1, weak; 2, intermediate; 3, strong) and tumor cell positive ratio (0, none; 1, < 1/100; 2, 1/100-1/10; 3, 1/10 − 1/3; 4, 1/3 − 2/3; 5, > 2/3).

Cell transfection

Lentiviral-transduced shRNA interference was performed to inhibit TRAIP and DDX39A expression. The lentivirus was purchased from GenePharma (GenePharma, China) and Genechem (Genechem, China). CAL27 and SCC15 cells were transfected with shTRAIP and shDDX39A, and SCC9 was transfected with oeTRAIP and oeDDX39A. CAL27 and SCC15 cells with TRAIP and DDX39A suppressed contained shTRAIP and shDDX39A, SCC9 with TRAIP and DDX39A overexpressed contained oeTRAIP and oeDDX39A, the control group was transfected with NC RNA. 4 × 104 cells were cultured in 6-well plates with 10% fetal bovine serum until 70-80% of the plates’ bottom was carpeted. After transfection with lentivirus in DMEM for 24 h, the culture medium was replaced with complete growth medium with 10% fetal bovine serum. Cells were cultured in medium containing puromycin after 48 h for follow-up experiments. All relative sequences are listed in Table S1.

Western blot

After covering the bottom surface of T25 culture flask, about 5 × 106 cells were used to extract proteins. Western blot assay was performed as described previously [20]. The following antibodies were used in this study: anti-TRAIP (Proteintech Group, Inc., Chicago, USA, dilution at 1:1000), anti-β-actin (Proteintech Group, Inc., Chicago, USA, dilution at 1:4000), anti-DDX39A, anti-E-cadherin, anti-N-cadherin, anti-Vimentin, anti-Slug, anti-Snail, anti-MMP2, anti-MMP9, anti-P-β-catenin, anti-β-catenin, anti-c-Myc, anti-cyclinD1 (Abclonal Technology, China, dilution at 1:1000). The stripe gray value of the target protein was measured using Image J and divided by the gray value of the reference protein for normalization. Then the obtained values were homogenized with reference to the control group data, and the expression trend value can be obtained. CAL27, SCC15 and SCC9 were used for western blot assay. All blots were cut prior to hybridization with antibodies. According to the required target proteins, the membrane was cut open and incubated in different boxes to eliminate the interference of some impurity bands.

Co-IP

After covering the bottom surface of the petri dish with a diameter of 10 cm, about 107 cells were disposed accordance with the Co-IP kit instructions (Takara Biotechnology, Japan). Then, 10 µl of 5× loading buffer was added into the protein, and the mixture was boiled for 15 min. The protein-protein complexes were later subjected to western blot and IgG was used as a NC. CAL27, SCC15 and SCC9 were used for Co-IP experiment.

Proliferation assay

A total of 2000 cells in 100 µl complete growth medium were seeded in 96-well plates and cultured separately for 1,2,3,4,5 days in an incubator before 10 µl of CCK-8 solution was added in each well for 1 h. The optical density value was detected at 450 nm by using a microplate reader. Each experiment was repeated three times. CAL27, SCC15 and SCC9 were used for proliferation assay.

Migration and invasion assays

In testing the migration ability of CAL27, SCC15 and SCC9, 5× cells in 100 µl of serum-free medium were added in upper Transwell chambers. The lower chamber was loaded with 500 µl of culture medium containing 30% fetal bovine serum. After incubating CAL27, SCC15 and SCC9 for 21, 15, and 17 h respectively, a cotton swab was used to wipe off cells in the upper chamber. The lower surface of Transwell chamber was immerged in 4% paraformaldehyde for 25 min and then dyed with 0.1% crystal violet.

In completing cells’ invasion assay, the inner surface of the Transwell chamber was laid with 100 µl of diluted Matrigel (Corning, USA) and placed in an incubator for 1 h. The 5× cells were added into the upper Transwell chamber and incubated for 27, 22 and 23 h for CAL27, SCC15 and SCC9, respectively. The rest of the steps were basically the same as describedpreviously. The total number of cells on the lower surface counted by Image J was regarded as the number of migrated cells.

Colony formation assays

TSCC cells were digested by pancreatin and counted by using a cell counting plate. The 1 cells on a single-cell suspension condition in a 2 ml culture medium were inoculated in 6-well plates. After being incubated for 14 days, the inner surface of the plate was immerged in 4% paraformaldehyde for 25 min and then dyed with 0.1% crystal violet. The colony number was calculated. CAL27, SCC15 and SCC9 were used for colony formation assays.

Wound healing assays

TSCC cells were seeded in 6-well plates and incubated until cells covered the bottom surface of plates. The inner surface cells were scratched using 200 µl pipette tip to create straight lines and then washed 3 times with PBS to eliminate detached cells. Then the cells were cultured in incubator with serum-free medium for 24 h. Wound area pictures of 0 h and 24 h were taken. The migration ability of cells is evaluated by measuring the area changes of the injured area using Image J in accordance with the following: scratch closure rate (%) = (injured area of 0 h - injured area of 24 h) / injured area of 0 h . CAL27, SCC15 and SCC9 were used for wound healing assays. The experiment was repeated 3 times.

Tumor xenografts in nude mice

Ten four-week-old nude mice were purchased from Beijing Sperford Company and managed by the Animal Management Center of Qingdao University. Nude mouse tumorigenesis experiment is a common experiment to study the biological characteristics of human tumors and tumor treatment. And the transplanted nude mouse tumor model has the advantages of high tumor formation rate, good uniformity, and could more accurately reflect the biological characteristics of the tumor cells. Six-week-old BALB/c nude mice were used for subcutaneous tumor implantation experiments. The 1CAL27 cells of the NC group and experimental group resuspended in 100 µl of PBS (phosphate buffer) and mixed with equal volume of Matrigel (8.1 mg/ml) were implanted to the right flank of each nude mouse subcutaneously for 6 weeks. The tumor was measured using a ruler each week. The tumor volume didn’t reach 1500 before the deadline of 6 weeks in accordance with the following formula: volume = 1/2length width2.

For the lung metastasis model, 1 cells were injected into the tail vein of nude mice. Six weeks later, mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation and the lung tissues were anatomized and analyzed by HE staining. The research protocol was approved by the Qingdao University Laboratory Animal Welfare Ethics Committee.

Cell cycle analysis

Cells were seeded in 6-well plates for 24 h and then collected to 15 ml centrifugal tubes. After centrifugation at 1000 g and 4℃ for 5 min, cells were washed by precooled PBS and centrifugated at the abovementioned condition. Cells were resuspended with 70% ethanol and placed in refrigerator at 4℃ for at least 2 h. After being resuspended with 250 µl of binding buffer and adjusted to the concentration of 1/ml, the cells were stained using propidium iodide (PI) and RNase for 15 min in darkness before being analyzed using a flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Inc., USA). CAL27, SCC15 and SCC9 were used for cell cycle analysis.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8.3.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). The results are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean. The results of two groups were compared using two-tailed Student t-test and three groups or more were compared using one-way ANOVA. The association of TRAIP and patient clinicopathologic characteristics was estimated using Wilcoxon rank-sum test. To ensure accuracy, all experiments were repeated at least three times independently. Statistical significance was marked using “*” to indicate P < 0.05.

Results

TRAIP expression is upregulated in human TSCC tissues

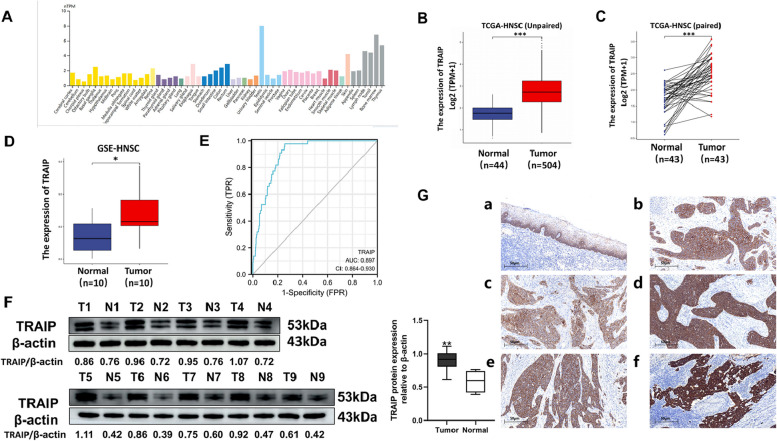

Using the Human Protein Atlas (HPA) database, we found that TRAIP was expressed in various normal tissues (Fig. 1A). This result suggested that TRAIP expression is lower in normal tongue tissue and higher in testis, bone marrow or thymus. We further assessed the TRAIP expression level in HNSC using TCGA joint GTEx and GEO data and found that the expression level of TRAIP is all significantly higher in HNSC tissue than in normal tissue (Fig. 1B). These results indicated a correlation between the high expression level of TRAIP and the tumorigenesis of HNSC. Based on the ROC curve, the cut-off value, AUC, sensitivity, specificity and Youden index were 2.284, 0.897, 0.743, 0.977 and 0.720, respectively (Fig. 1E). These abovementioned data indicated that TRAIP may play an important role in HNSC diagnosis.

Fig. 1.

The expression level of TRAIP is upregulated in TSCC. A The level of TRAIP expression in different human normal tissues. B TRAIP levels in unpaired HNSC tissues and normal tissues in TCGA. C TRAIP levels in paired HNSC tissues and normal tissues in TCGA. D TRAIP levels in paired HNSC tissues and normal tissues in GSE. E ROC for TRAIP to diagnose HNSC. F TRAIP protein expression levels in TSCC were higher than that in normal tissues. T: tumor, N: normal tissue. G Representative IHC images of TRAIP expression. IHC findings showed that the expression level of TRAIP in TSCC tissues(b, IHC score: 6) was higher than that in adjacent tissues(a, IHC score: 4). The TRAIP expression level was higher in the primary tumors with lymph node metastasis(d, IHC score: 7) than that without lymph node metastasis(c, IHC score: 5) .The immuno-staining is strongly positive in lymph node metastasis(f, IHC score: 8) than in primary tumor tissues(e, IHC score: 6). a:100X ; b-f : 200X *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

We further studied the correlations between TRAIP expression and patient clinicopathological characteristics in human TSCC. The TRAIP expression in 9 pairs of fresh TSCC tumors and adjacent tissues was detected using western blot. The results suggested that TRAIP expression in tumor tissues was significantly higher than that in adjacent tissues, which indicated that TRAIP was up regulated in TSCC (P < 0.01, Fig. 1F). Meanwhile, IHC findings showed that the expression level of TRAIP in TSCC tissues was higher than that in adjacent tissues (Fig. 1G-a, b). The TRAIP expression level was higher in the primary tumors with lymph node metastasis than that without lymph node metastasis TRAIP was located in the cytoplasm and cell membrane (Fig. 1G-c, d). In addition, the immuno-staining is strongly positive in lymph node metastasis than in primary tumor tissues (Fig. 1G-e, f). As shown in Table 1, no significant association was observed between TRAIP expression and patients’ gender, age and gross tumor type (P > 0.05). However, the expression level of TRAIP evidently increased in stage III/IV compared with stage I/II, in carcinoma compared with adjacent tissue, in poor differentiation compared with well differentiation, in tissues with recurrence compared with those without recurrence, and in tissues with lymph node metastasis compared with thosewithout lymph node metastasis (P < 0.05).

TRAIP promotes TSCC cell proliferation and invasion

A total of 19,577 protein coding genes were obtained in TRAIP expression grouping (except TRAIP) and the volcano maps are shown in Figure S1A. By analyzing the abovementioned genes using GSEA, we obtained 389 entries in the C2 gene set and plotted the GSEA plots. The results indicated that TRAIP was related to the proliferation (Figure S1B-C), invasion (Figure S1D-E), and metastasis (Figure S 1F-H) of tumors, as well as DNA replication (Figure S1I-J), EMT (Figure S1K-L), cell cycle (Figure S1M-O), and Wnt/β-catenin pathway (Figure S1P).

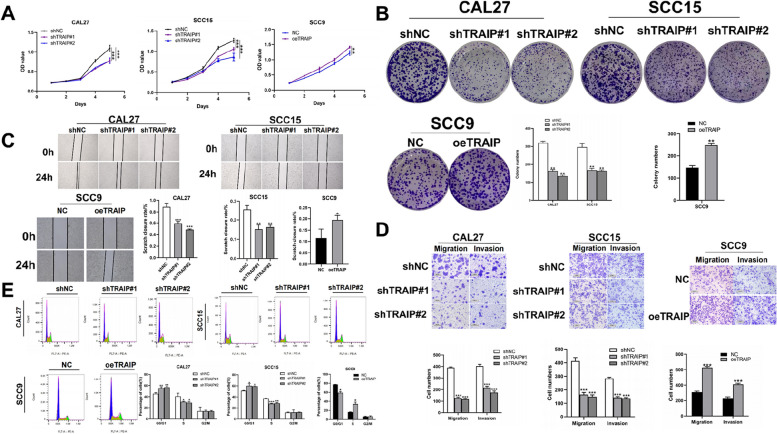

Western blot was used to detect the relative TRAIP expression in CAL27, SCC15 and SCC9 cells (Figure S2A). CAL27 and SCC15 showing a high expression level of TRAIP were selected for silencing TRAIP expression (Figure S2B). SCC9 showed the lowest expression level of TRAIP, which was used to overexpress TRAIP (Figure S2C). In studying the effect of TRAIP on TSCC, the expression level of TRAIP was silenced or overexpressed using lentiviruses. Proliferation assay and colony formation assay showed that cells with TRAIP silencing proliferated slowly and conversely, the cells selected to overexpress TRAIP grew faster (P < 0.01, Fig. 2A, B) compared with the NC group. Wound healing assay and Transwell assay revealed that TRAIP downregulation inhibited cell migration and invasion, but when TRAIP upregulated, the opposite applies (P < 0.05, Fig. 2C, D).

Fig. 2.

TRAIP promotes TSCC cell proliferation, migration and invasion in vitro. Cell viability was tested using proliferation assay (A). Cell proliferation ability was detected using colony formation assay (B). Wound healing assay (C) and transwell assay (D) were used to detect the migration and invasion abilities of TSCC cell. E The distribution of cell phase in TSCC cell lines after TRAIP was silenced or overexpressed. Data are shown as mean ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

In exploring whether TRAIP influences the cell cycle progression in TSCC, groups with different TRAIP expression were involved. As shown in Fig. 2E, the percentage of cells increased in the G1 phase and decreased in the S phase in the shTRAIP group compared with the shNC group, and the trend was opposite in the TRAIP overexpressed group (P < 0.05), indicating that shTRAIP induces G1 cell cycle arrest in TSCC cells.

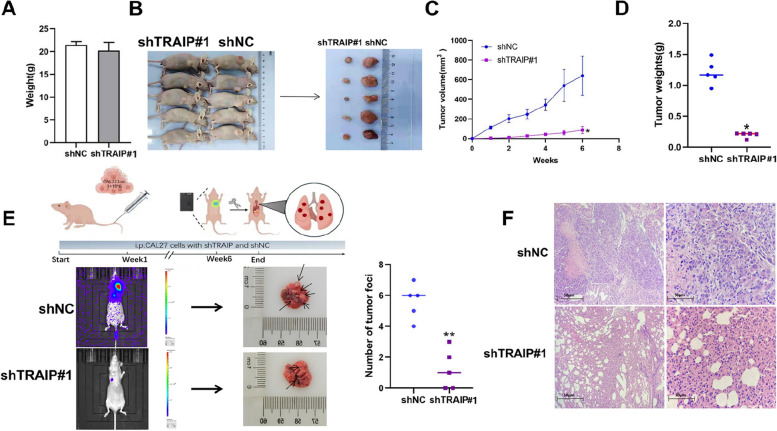

TRAIP knockdown inhibits tumor growth and metastasisin vivo

In conforming the effect of downregulated TRAIP on proliferation in vivo, CAL27 cells with shTRAIP and shNC were planted to nude mice subcutaneously and injected into the tail vein of nude mice separately. Six weeks later, the results from xenograft tumor models, as assessed by IHC, demonstrated a stable knockdown of TRAIP in the shTRAIP group(Figure S5F), the weight of mice of the two groups didn’t have significant difference (Fig. 3A). In addition, the tumor weight in the experimental group was significantly less than that in the shNC group (196.8038.54 mg vs. 1210.00179.22 mg, P<0.05, Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3.

TRAIP knockdown inhibited TSCC cell growth and metastasis in vivo. A The weight of mice. B Dissected tumors generated by TRAIP knockdown or negative control CAL27 cell (n = 5). C, D The growth curve (C) and weights of xenograft tumors (D). E The metastatic nodules of nude mice lungs after tail vein injection of TRAIP knockdown or negative control CAL27 cell. F Representative HE images of lung tissues after tail vein injection (left : 200X ; right : 400X ; upper: shTRAIP#1 group; lower: shNC group). *P < 0.05

The in vivo bioluminescence imaging was used to detect metastasis in lung tissues. Three mice in the shTRAIP group had lung metastasis, whereas all five mice developed lung metastasis in the shNC group. The number of tumor foci detected in the shNC group was significantly more than that in the shTRAIP group (Fig. 3E). Hematoxylin-eosin staining also confirmed this result (Fig. 3F). These findings indicate that depleting TRAIP inhibits the proliferation and metastasis of TSCC cells in vivo.

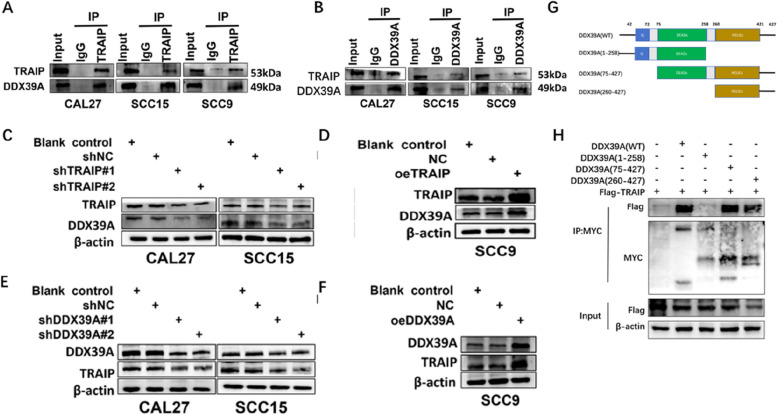

DDX39A may be the interacting protein of TRAIP

In revealing the molecular mechanisms of TRAIP promoting TSCC progression, bioinformatics analysis, mass spectrometry and Co-IP were used. The flow chart is shown in figure S3. A total of 19,578 protein coding genes were obtained in patients with HNSC. The volcano maps are shown in Figure S4A. By taking the intersection of two differentially expressed genes and the results of mass spectrometry (table S2, table S3), and screening through the STRING database, 8 related genes were finally obtained (DNAJC9, RFC3, DDX18, CORO1C, ETF1, RFC4, DDX39A and PFDN2, Figure S4B-D). We found that RFC4 and DDX39A have higher relevance with TRAIP by analyzing the correlation between the abovementioned 8 genes and TRAIP (Figure S4E-M, table S4). Considering that the relationship between RFC4 and TSCC has been revealed [21], we selected DDX39A for the subsequent experiment. In addition, We found that the expression pattern of DDX39A in TSCC cells is similar to that of TRAIP(Fig S5A).

The relationship between TRAIP and DDX39A was confirmed by Co-IP (Fig. 4A, B). Figure 4A shows that DDX39A was one of the proteins that bind to TRAIP. Figure 4B shows that TRAIP was also one of the proteins that bind to DDX39A. The DDX39A protein levels were decreased when TRAIP was knocked down in TSCC cell lines (Fig. 4C, Figure S5F). On the contrary, the DDX39A protein level increased when TRAIP was overexpressed (Fig. 4D). When DDX39A was silenced or upregulated, the expression level of TRAIP was also downregulated or overexpressed (Fig. 4E, F).In addition, truncated bodies mutually experiments show that the HELICc domain of DDX39A is the necessary structure for the interaction between DDX39A and TRAIP region (Fig. 4G, H).

Fig. 4.

TRAIP interacts with DDX39A in TSCC cells. A, B Whole-cell lysates of CAL27, SCC15 and SCC9 cells were used in Co-IP with IgG (control) and anti-TRAIP or anti-DDX39A antibodies. C-F Western blot analysis was used to measure the expression of TRAIP and DDX39A in these two factors silenced or overexpressed cells. G Schematic of DDX39A domains. H Co-immunoprecipitation analysis of the interaction of Flag-TRAIP and WT or truncated MYC-DDX39A

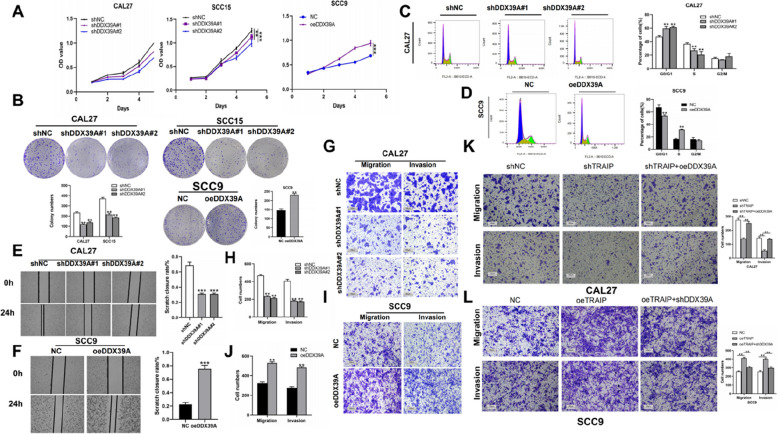

TRAIP promotes TSCC cell proliferation and invasion by increasing DDX39A expression

As shown in Fig. 5, DDX39A knockdown inhibited cell proliferation (Fig. 5A, B), cell cycle progression (Fig. 5C-D, Figure S5C), migration, invasion (Fig. 5E-J, Figure S5D) and caused G1 cell cycle arrest, and when DDX39A was overexpressed, the results were opposite. In determiningthe relationship between DDX39A and TRAIP in TSCC progression, rescue experiments were performed. DDX39A was overexpressed in TRAIP-knockdown cells and DDX39A was silenced in TRAIP overexpressed cells. Transwell assays indicated that DDX39A overexpression (partly) rescued the migration and invasion abilities in TRAIP-knockdown cells, and DDX39A silencing decreased the migration and invasion abilities caused by TRAIP overexpression (Fig. 5K, L). These results suggested that TRAIP interacted with DDX39A during TSCC progression.

Fig. 5.

DDX39A promotes TSCC cell proliferation and migration in vitro. Cell growth ability was determined using proliferation assay (A) and colony formation assay (B), (C-D) The distribution of cell phase after DDX39A was silenced or overexpressed. The migration abilities were measured using wound healing assay (E-F). DDX39A promotes TSCC cell migration and invasion in vitro. The migration and invasion abilities were measured using Transwell assay (G-L) *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

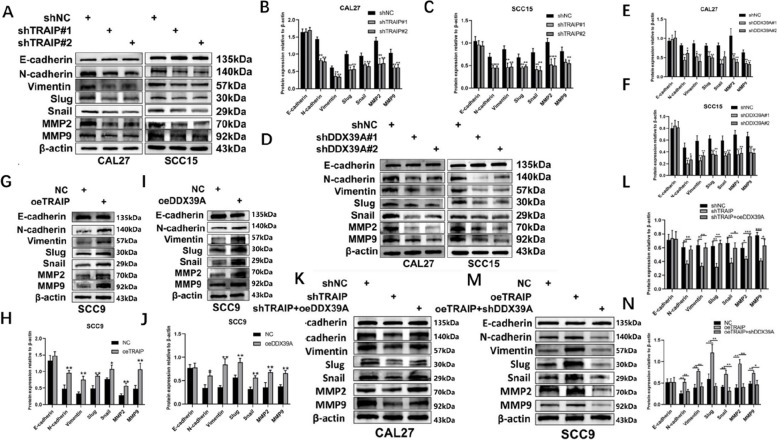

TRAIP and DDX39A induces EMT in TSCC cells

Western blot analysis showed that when TRAIP or DDX39A was suppressed, the protein levels of N-cadherin, Vimentin, Slug, Snail, MMP-2 and MMP-9 were decreased, and E-cadherin expression didn’t have obvious change (Fig. 6A-F). When TRAIP or DDX39A was upregulated, the expression level of N-cadherin, Vimentin, Slug, Snail, MMP-2 and MMP-9 was increased, and E-cadherin expression still didn’t remarkably change (Fig. 6G-J). In addition, Upon TRAIP overexpression, cells demonstrated an elongated morphology, accompanied by an extension of the cytoskeletal structure(Figure S5B). The overexpression of DDX39A might increase the expression level of EMT related proteins (except for E-cadherin) caused by TRAIP suppression (Fig. 6K, L). In addition, the downregulation of DDX39A can decrease the expression level of EMT related proteins (except for E-cadherin) caused by TRAIP overexpression (Fig. 6M, N).

Fig. 6.

TRAIP promotes TSCC cell migration and invasion by EMT. Western blot analysis was used to determine the protein levels of E-cadherin, N-cadherin, Vimentin, Slug, Snail, MMP2, MMP9 after TRAIP or DDX39A was silenced (A-F). TRAIP promotes TSCC cell migration and invasion by EMT. Western blot analysis was used to determine the protein levels of E-cadherin, N-cadherin, Vimentin, Slug, Snail, MMP2, MMP9 after TRAIP or DDX39A was overexpressed (G-J). CAL27 and SCC9 cells were transfected with lentiviruses. Cells were used to detect the EMT relative proteins expression (K-N)

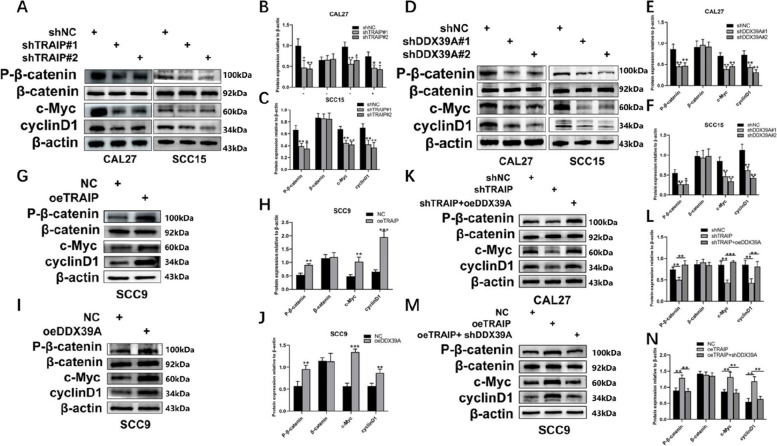

DDX39A and TRAIP regulated proliferation, migration and invasion via Wnt/β-catenin pathway in TSCC cells

In exploring the mechanism of TRAIP and DDX39A in regulating cell progression in TSCC, we analyzed the protein levels of Wnt/β-catenin pathway. TRAIP or DDX39A silencing decreased the expression level of P-β-catenin, cyclinD1 and c-Myc, but β-catenin expression level didn’t significantly change (Fig. 7A-F). In the xenograft tumor models, the immunohistochemistry results show that knockdown of TRAIP leads to a significant reduction in the expression of phosphorylated β-catenin (P-β-catenin) in both the cytoplasm and nucleus. This is consistent with the results observed in the Western blot analysis (Figure S5F). Conversely, the expression level of P-β-catenin, cyclinD1 and c-Myc was increased after TRAIP or DDX39A overexpression, and β-catenin expression level still didn’t significantly change (Fig. 7G-J). The overexpression of DDX39A might enhance the expression level of P-β-catenin, cyclinD1 and c-Myc caused by TRAIP suppression (Fig. 7K, L). Moreover, the downregulation of DDX39A can diminish the expression level of related proteins caused by TRAIP overexpression (Fig. 7M, N). The diagram was plotted using Biorender (https://biorender.com/, Fig. 8).

Fig. 7.

TRAIP and DDX39A activate Wnt/β-catenin pathway in TSCC cells. Western blot analysis of Wnt/β-catenin pathway relative proteins after TRAIP or DDX39A knockdown (A-F). TRAIP and DDX39A activate Wnt/β-catenin pathway in TSCC cells. Western blot analysis of Wnt/β-catenin pathway relative proteins after TRAIP or DDX39A overexpressed (G-J). CAL27 and SCC9 cells were transfected with lentiviruses. Cells were used to detect the Wnt/β-catenin pathway relative proteins expression (K-N)

Fig. 8.

The schematic diagram of TRAIP regulates TSCC cells proliferation, migration and invasion by interacting with DDX39A via Wnt/β-catenin pathway. By BioRender

Discussion

At present, the main treatment of tongue carcinoma is surgery, and chemoradiation is also important in advanced stage patients [22]. However, these treatments damage patients’ appearance, cause psychosocial problems, and lead to functional defect, particularly dysphagia [23, 24]. Some other severe complications are found in these therapies, which seriously influence the quality of life. Therefore, exploring ways at a molecular level is of great importance to improve patient prognosis [25].

Much evidence has accumulated indicating that TRAIP as a TRAF-interacting protein, plays a crucial role in various biological processes within the organism [26]. Considering the mammalian replicative stress response and as a factor interacting with the proliferation cell nuclear antigen, TRAIP contributes to the recovery of impaired DNA replication forks [27]. TRAIP regulates mitotic process by regulating the spindle assembly checkpoint and it’s crucial to early mitotic process and arrangement of metaphase chromosomes [28]. Previous investigations have demonstrated the role of TRAIP in various cancer processes, including hepatocellular carcinoma, breast cancer, osteosarcoma, and choroidal melanoma. Our research suggested that TRAIP is highly expressed in TSCC and closely related to the prognosis of patients. Therefore, TRAIP might promote the malignant behavior of TSCC. Our in vivo and in vitro experimental results also showed that TRAIP may stimulate the proliferation, migration and invasion of TSCC cells.

Given the critical role of TRAIP in the process of cell growth, it is essential to further investigate its response within the cell cycle, particularly after establishing its function in oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC). Our research also showed that silencing TRAIP induces G1 cell cycle arrest in TSCC cells, which consists with the role of TRAIP in foreskin keratinocyte [29]. After silencing TRAIP or DDX39A, the expression of CyclinD1 was decreased. The main function of CyclinD1 is to promote cell proliferation. CyclinD1 binds to and activates the G1-phase unique cyclin-dependent kinase CDK4, which is phosphorylated by the G1 phase cycle inhibitor protein (Rb). Moreover, the phosphorylated Rb protein is dissociated from the E2F transcription factor to which it binds, and the E2F transcription factor initiates the transcription of genes in the living cell cycle, thereby promoting the cell cycle from the G1 phase to the S phase [30]. We hypothesized that TRAIP and DDX39A cause cell cycle arrest by inhibiting CyclinD1 expression.

To further investigate the underlying mechanisms of TRAIP in tongue squamous cell carcinoma using mass spectrometry and co-IP experiments, we identified a direct interaction between TRAIP and DDX39A. TRAIP is a nucleocytoplasmic shuttling protein, These proteins typically enter the nucleus through specific signal sequences, such as the nuclear localization signal (NLS), and are exported to the cytoplasm via the nuclear export signal (NES) [31, 32]. Research has shown that TRAIP can directly interact with TBK1 in the cytoplasm to promotes K48-linked polyubiquitination of TBK1, leading to its proteasomal degradation [33]. Thus, TRAIP can interact with DDX39A, which is localized in the nucleus. DDX39A as a member of the DEAD-box RNA helicase family of nucleic acid-binding proteins can inhibit the export of mRNA and recruit Aly to the spliced mRNP [34]. Additionally, DDX39A is involved in cytoplasmic mRNA localization, genomic integrity, and the processes of mitosis and cytokinesis [35]. By performing bioinformatics analysis, we found that DDX39A was highly expressed in TSCC tissue compared with normal tissue. We prove that DDX39A is the interacting protein of TRAIP, and HELICc domain of DDX39A is the key to interact with TRAIP. The interaction of TRAIP and DDX39A can regulate the proliferation, migration, invasion abilities and cell cycle progression in TSCC. Since DDX39A has been researched to be involved in Wnt/β-catenin pathway by promoting β-catenin accumulate in nucleus, and the expression of Wnt signaling target genes [35], DDX39A promotes hepatocellular carcinoma growth and metastasis by activating Wnt/β-catenin pathway [36]. The Wnt/β-catenin pathway comprises a family of proteins that play critical roles in embryonic development and adult tissue homeostasis [37]. We hypothesize that the interaction between TRAIP and DDX39A may promote the activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway and performed validation. The results of our experiments show that the activation of β-catenin was suppressed when either TRAIP or DDX39A was knocked down. These findings confirm that TRAIP influences β-catenin activation through its interaction with DDX39A. Future studies would focus on whether TRAIP functions as an E3 ubiquitin ligase to regulate DDX39A stability and how this affects DDX39A’s role in β-catenin enrichment and nuclear translocation. In addition, we also found that TRAIP and DDX39A could enhance the phosphorylation of β-catenin without affecting its protein expression levels. In the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, the mechanism by which β-catenin expression is maintained in a stable state within cells is relatively complex. The primary mode of β-catenin degradation occurs via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway following phosphorylation by the GSK3β complex [38]. However, in this study, it was observed that knockdown of TRAIP or DDX39A led to inhibited β-catenin phosphorylation, while the overall expression levels remained unchanged. This may be explained by the fact that β-catenin is a highly abundant protein, with phosphorylated β-catenin constituting only a small fraction of the total β-catenin pool in cells. As a result, the decrease in phosphorylated β-catenin may not significantly affect the total protein levels, leading to a relatively unchanged overall expression.

Based on our research, we have found that TRAIP promotes cell invasion and migration. EMT and stemness have become widely accepted as crucial biological processes driving tumour cell invasion and metastatic dissemination from primary tumours [39]. Our results show that TRAIP influences EMT through its interaction with DDX39A. However, the mechanisms by which this interaction affects EMT remain unexplored. We suppose that TRAIP may enhance the stability of DDX39A, which, as an RNA splicing factor, may exhibit increased RNA helicase activity [39]. This enhanced activity could, in turn, facilitate the splicing and transport of mRNAs of EMT-related genes more efficiently, further increase the expression of EMT-related genes [40]. In addition, previous studies have shown that the activation of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway could induce EMT [40]. Specifically, the accumulation of β-catenin and its nuclear translocation can upregulate the expression of EMT-related genes [13, 41]. Therefore, we speculate that TRAIP may regulate the Wnt signaling pathway and EMT through interaction with DDX39A, but the detailed mechanisms remain to be explored.

It is worth mentioning that TRAIP is a replisome-associated E3 ubiquitin ligase, which has a RING finger motif and an extended coiled-coil domain [41]. Diverse signaling factors mediate the up- or down-regulation of Wnt signaling through post-translational modifications [42]. Target therapies for the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway are varied and clinical experiments are nascent in a host of cancers [43]. Future research will focus on elucidating the role of TRAIP-mediated ubiquitination in the regulation of the DDX39A, Wnt signaling pathway and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [44], as well as investigating tumor suppressors associated with the Wnt pathway [45].

Up to now, this study is the first to investigate (1) TRAIP expression in TSCC and its relationship with clinicopathological characteristics of TSCC patients, (2) the effect of TRAIP and DDX39A on progression of TSCC cells, (3) the interaction of TRAIP and DDX39A in TSCC progression, (4) the mechanism by which the two factors regulate tumor malignant behaviors. Our research indicates that TRAIP and DDX39A may be potential treatment targets in TSCC.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Material 1: Tab. S1 Sequence of TRAIP, DDX39A and their negative control.

Supplementary Material 2: Tab. S2 Proteins that interact with the tag protein of TRAIP.

Supplementary Material 3: Tab. S3 Proteins that interact with the IgG protein.

Supplementary Material 4: Tab. S4 Correlation between TRAIP and 8 genes.

Supplementary Material 5: Fig. S1 Biological function of TRAIP in HNSC. (A) The volcano maps of TRAIP DEGs in TCGA-HNSC. (B, C) Proliferation. (D, E) Invasion. (F-H) Metastasis. (I-J) DNA replication. (K, L) Epithelial mesenchymal transition. (M-O) Cell cycle. (P) Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Fig. S2 TRAIP expression in TSCC cell lines. (A) Western blot analysis of TRAIP in three TSCC cell lines. (B, C) The TSCC cells were infected with lentivirus. The transfective effenciency was tested using western blot analysis. *P< 0.05, **P< 0.01, ***P< 0.001. Fig. S3 The “mass spectrum” flow chart. Fig. S4 DDX39A may interact with TRAIP in TSCC. (A) The volcano maps of DEGs in TCGA-HNSC. (B) Intersection of mass spectrum results. (C) The intersection of two differentially expressed genes and the results of mass spectrometry. (D) The result of STRING network. (E) Heatmap of co-expression of TRAIP and 8 genes. (F-M) Correlation between TRAIP and 8 genes. DNAJC9 (F). RFC3 (G). DDX18 (H). CORO1C (I). ETF1 (J). RFC4 (K). DDX39A (L). PFDN2 (M). Fig. S5 The distribution of cell phase after DDX39A was silenced in SCC15(A). Western blot analysis of DDX39A in three TSCC cell lines. (B). The morphological changes following TRAIP overexpression in SCC9.(C). The migration abilities were measured using wound healing assay in SCC15. (D). DDX39A promotes TSCC cell migration and invasion in vitro. (E). The migration and invasion abilities were measured using Transwell assay. (F). The detection of TRAIP, DDX39A, β-catenin and P-β-catenin expression from the xenograft tumor models by IHC; 400X; *P< 0.05, **P< 0.01, ***P< 0.001.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

CW was responsible for the conception and design. PW, LL and CG contributed to the experimental performance. LS, LC, HQ and YZ were responsible for data analysis. PW, CW and XX were responsible for manuscript writing and revision.

Funding

This research was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2022MH206), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.81672606), and Beijing Jingjian Pathology Development Foundation (JJlXA2022-008).

Data availability

All data from this study are available from the corresponding author.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research protocol was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University (registration no. QYFY WZLL 27524) and Qingdao University Laboratory Animal Welfare Ethics Committee (registration no. 20210420BALB/Cnude100615001). All patients or their guardians were given and accepted informed consent. All animal studies were given and accepted informed consent from the owner.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Litong Liu, Ping Wang and Cheng Guo these authors contributed equally for this work.

References

- 1.Warnakulasuriya S, Kerr AR. Oral cancer screening: past, present, and future. J Dent Res. 2021;100(12):1313–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pillai J, et al. A systematic review of proteomic biomarkers in oral squamous cell cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2021;19(1):315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lenze NR, et al. Age and risk of recurrence in oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma: systematic review. Head Neck. 2020;42(12):3755–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang K, et al. LUCAT1 as an oncogene in tongue squamous cell carcinoma by targeting miR-375 expression. J Cell Mol Med. 2021;25(10):4543–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonomo P, et al. Quality Assessment in supportive care in Head and Neck Cancer. Front Oncol. 2019;9:926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chapard C, Hohl D, Huber M. The role of the TRAF-interacting protein in proliferation and differentiation. Exp Dermatol. 2012;21(5):321–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guo Z, et al. TRAIP promotes malignant behaviors and correlates with poor prognosis in liver cancer. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;124:109857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu Y, et al. LncRNA SLC7A11-AS1 contributes to Lung Cancer Progression through facilitating TRAIP expression by inhibiting miR-4775. Onco Targets Ther. 2020;13:6295–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li M, et al. TRAIP modulates the IGFBP3/AKT pathway to enhance the invasion and proliferation of osteosarcoma by promoting KANK1 degradation. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12(8):767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zheng Y, et al. Silencing TRAIP suppresses cell proliferation and migration/invasion of triple negative breast cancer via RB-E2F signaling and EMT. Cancer Gene Ther. 2023;30(1):74–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park ES, et al. Early embryonic lethality caused by targeted disruption of the TRAF-interacting protein (TRIP) gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;363(4):971–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen C, Huang H, Wu CH. Protein bioinformatics databases and resources. Methods Mol Biol. 2017;1558:3–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tian W, et al. AURKAIP1 actuates tumor progression through stabilizing DDX5 in triple negative breast cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2023;14(12):790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reyes M, et al. Wnt/β-catenin signaling in oral carcinogenesis. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(13):4682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vivian J, et al. Toil enables reproducible, open source, big biomedical data analyses. Nat Biotechnol. 2017;35(4):314–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhuang Z, et al. Down-regulation of long non-coding RNA TINCR induces cell dedifferentiation and predicts progression in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Front Oncol. 2020;10:624752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robin X, et al. pROC: an open-source package for R and S + to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of Fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15(12):550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu T, et al. clusterProfiler 4.0: a universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innov (Camb). 2021;2(3):100141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang C, et al. Silencing of KIF3B suppresses breast Cancer progression by regulating EMT and Wnt/β-Catenin signaling. Front Oncol. 2020;10:597464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang J, Wang L, Xie X. RFC4 promotes the progression and growth of oral Tongue squamous cell carcinoma in vivo and vitro. J Clin Lab Anal. 2021;35(5): e23761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liao JK, et al. Cancer-associated fi broblasts confer cisplatin resistance of tongue cancer via autophagy activation. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;97:1341–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen Goldemberg D, et al. Tongue cancer epidemiology in Brazil: incidence, morbidity and mortality. Head Neck. 2018;40(8):1834–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang ZS, et al. Dysphagia in tongue cancer patients before and after surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016;74(10):2067–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pai SG, et al. Wnt/beta-catenin pathway: modulating anticancer immune response. J Hematol Oncol. 2017;10(1):101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sajjad N, et al. Recognition of TRAIP with TRAFs: current understanding and associated diseases. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2019;115: 105589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scaramuzza S, et al. TRAIP resolves DNA replication-transcription conflicts during the S-phase of unperturbed cells. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):5071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu RA, et al. TRAIP is a master regulator of DNA interstrand crosslink repair. Nature. 2019;567(7747):267–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ou D, et al. Mir-340-5p affects oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) cells proliferation and invasion by targeting endoplasmic reticulum stress proteins. Eur J Pharmacol. 2022;920: 174820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goel S, Bergholz JS, Zhao JJ. Targeting CDK4 and CDK6 in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2022;22(6):356–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cuella-Martin R, et al. Functional interrogation of DNA damage response variants with base editing screens. Cell. 2021;184(4):1081–e109719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu J, et al. TRAIP suppresses bladder cancer progression by catalyzing K48-linked polyubiquitination of MYC. Oncogene. 2024;43(7):470–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shi P, et al. Dual regulation of host TRAIP post-translation and Nuclear/Plasma distribution by Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus non-structural protein 1alpha promotes viral proliferation. Front Immunol. 2018;9:3023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Banerjee S, et al. Parsing the roles of DExD-box proteins DDX39A and DDX39B in alternative RNA splicing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024;52(14):8534–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tapescu I, et al. The RNA helicase DDX39A binds a conserved structure in Chikungunya virus RNA to control infection. Mol Cell. 2023;83(22):4174–e41897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang T, et al. DDX39 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma growth and metastasis through activating Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9(6):675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu J, et al. Wnt/beta-catenin signalling: function, biological mechanisms, and therapeutic opportunities. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7(1):3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nelson WJ, Nusse R. Convergence of wnt, beta-catenin, and cadherin pathways. Science. 2004;303(5663):1483–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taniguchi I, Hirose T, Ohno M. The RNA helicase DDX39 contributes to the nuclear export of spliceosomal U snRNA by loading of PHAX onto RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024;52(17):10668–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang YE, Stuelten CH. Alternative splicing in EMT and TGF-beta signaling during cancer progression. Semin Cancer Biol. 2024;101:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu RA, Pellman DS, Walter JC. The Ubiquitin Ligase TRAIP: double-edged Sword at the Replisome. Trends Cell Biol. 2021;31(2):75–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Park HB, Kim JW, Baek KH. Regulation of wnt signaling through Ubiquitination and Deubiquitination in Cancers. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(11):3904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tang Y, et al. Dissection of FOXO1-Induced LYPLAL1-DT Impeding Triple-negative breast Cancer progression via mediating hnRNPK/beta-Catenin complex. Res (Wash D C). 2023;6:p0289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang Z, et al. RGS6 suppresses TGF-beta-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in non-small cell lung cancers via a novel mechanism dependent on its interaction with SMAD4. Cell Death Dis. 2022;13(7):656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krishnamurthy N, Kurzrock R. Targeting the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway in cancer: update on effectors and inhibitors. Cancer Treat Rev. 2018;62:50–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material 1: Tab. S1 Sequence of TRAIP, DDX39A and their negative control.

Supplementary Material 2: Tab. S2 Proteins that interact with the tag protein of TRAIP.

Supplementary Material 3: Tab. S3 Proteins that interact with the IgG protein.

Supplementary Material 4: Tab. S4 Correlation between TRAIP and 8 genes.

Supplementary Material 5: Fig. S1 Biological function of TRAIP in HNSC. (A) The volcano maps of TRAIP DEGs in TCGA-HNSC. (B, C) Proliferation. (D, E) Invasion. (F-H) Metastasis. (I-J) DNA replication. (K, L) Epithelial mesenchymal transition. (M-O) Cell cycle. (P) Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Fig. S2 TRAIP expression in TSCC cell lines. (A) Western blot analysis of TRAIP in three TSCC cell lines. (B, C) The TSCC cells were infected with lentivirus. The transfective effenciency was tested using western blot analysis. *P< 0.05, **P< 0.01, ***P< 0.001. Fig. S3 The “mass spectrum” flow chart. Fig. S4 DDX39A may interact with TRAIP in TSCC. (A) The volcano maps of DEGs in TCGA-HNSC. (B) Intersection of mass spectrum results. (C) The intersection of two differentially expressed genes and the results of mass spectrometry. (D) The result of STRING network. (E) Heatmap of co-expression of TRAIP and 8 genes. (F-M) Correlation between TRAIP and 8 genes. DNAJC9 (F). RFC3 (G). DDX18 (H). CORO1C (I). ETF1 (J). RFC4 (K). DDX39A (L). PFDN2 (M). Fig. S5 The distribution of cell phase after DDX39A was silenced in SCC15(A). Western blot analysis of DDX39A in three TSCC cell lines. (B). The morphological changes following TRAIP overexpression in SCC9.(C). The migration abilities were measured using wound healing assay in SCC15. (D). DDX39A promotes TSCC cell migration and invasion in vitro. (E). The migration and invasion abilities were measured using Transwell assay. (F). The detection of TRAIP, DDX39A, β-catenin and P-β-catenin expression from the xenograft tumor models by IHC; 400X; *P< 0.05, **P< 0.01, ***P< 0.001.

Data Availability Statement

All data from this study are available from the corresponding author.