Abstract

Background

Dorper sheep are celebrated for their fast maturation and superior meat quality, with some shedding their wool each spring. Wool shedding occurs naturally due to the hair follicle (HF) cycle, but its regulatory mechanisms remain unclear and need further investigation.

Results

In this study, shedding and non-shedding sheep were selected from the same Dorper flock. Skin samples were collected in September of the first year and January and March of the following years. RNA sequencing was performed on these samples. Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to assess the results. A total of 2536 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified. Using a clustering heatmap and fuzzy clustering analysis three distinct gene expression patterns were identified: A pattern (high expression in anagen), T1 pattern, and T2 pattern (high expression in telogen). For each pattern, differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were analyzed through Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analyses. Combining this with pathway expression analysis, six A-pattern and fourteen T-pattern pathways linked to telogen-anagen transition in the HF cycle were identified. Networks of key pathways were then constructed. Additionally, key genes were identified in the telogen-anagen transition, including one A-pattern gene and seven T-pattern (T1, 1; T2, 6) genes, using the Maximal Clique Centrality (MCC) tool in Cytoscape. Predicted transcription factors (TFs) involved in key pathways, such as LEF and STAT5B, were identified. Finally, RNA-seq results were confirmed by RT-qPCR.

Conclusion

This study highlights critical genes and pathways in the telogen-anagen transition, and transcriptome sequencing along with bioinformatics analysis provides new insights into the regulatory mechanisms of the HF cycle and development.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12864-024-11059-7.

Keywords: Dorper sheep, Shedding, Hair cycle, RNA-seq, Hair follicle, Transcriptome analysis

Background

Dorper sheep HFs are composed of primary hair follicles (PHFs) and secondary hair follicles (SHFs) [1]. PHFs produce coarse wool, while SHFs produce fine wool [2–5]. Both types undergo repeated HF cycles, but SHFs have shorter, more active cycles than PHFs [3]. In part of the Dorper herd, a clear HF cycle is observed in SHFs. The HF cycle generally comprises three phases: active growth (anagen), apoptosis-induced degradation (catagen), and relative stasis (telogen). A more detailed subdivision based on HF morphological structure has been made [6–8]. For example, He et al. divided the SHF cycle in Hexi cashmere goats into proanagen, anagen, procatagen, catagen, and telogen phases [7]. Similarly, Liu et al. reported the HF cycle in Tibetan sheep as mid-anagen in May, catagen in October, and late telogen/early anagen in January [9]. The wool shedding phase, known as exogen, is characterized by a notable loss of wool cover in specific areas or throughout the sheep’s body [10]. This phase primarily occurs during the transition from the resting stage (telogen) to the active growth stage (anagen) of the hair cycle, yet it is frequently overlooked [11]. Microscopically, the hair shaft takes on the form of “club hair,” which is identifiable by its distinctive crumpled, brush-like appearance at the base. Shedding is believed to be an active process influenced by specific signals that disrupt the adhesion of the club hair to surrounding epithelial cells, though the exact mechanism is still unclear.

The HF cycle is regulated by various genes and signaling pathways. WNT/β-catenin signaling is critical for initiating anagen, and absence of β-catenin in the dermal papilla halts hair regeneration [12]. Sonic hedgehog (Shh) signaling, influenced by Wnt/β-catenin signaling, is essential for downward growth of the HF, though it is not required for hair placode formation or early epidermal ingrowth [2, 13, 14]. BMP signaling, which opposes Wnt and Shh pathways, inhibits HFs from entering the anagen phase, with Bmp2 and Bmp4 in the dermis playing roles in cyclic process [15]. TGF-β signaling is complex; TGF-β2 promotes anagen by suppressing BMP signaling in HF stem cells, but can also cause apoptosis in HF epidermal cells via the MAPK pathway, leading to catagen [16, 17]. The coexistence and antagonism of these pathways significantly impact the HF cycle and morphological changes.

With high-throughput technology advances, transcriptome analysis has become popular to study gene expression and regulation in mice, sheep, and other animals. These methods have facilitated gene screening related to HF growth and development. For example, Liu et al. identified 12,865 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in Inner Mongolia cashmere goats, with 7664 up-regulated and 5201 down-regulated genes during anagen and telogen [18]. Bhat et al. examined transcriptome profiles in Pashmina goats, outlining genes and pathways regulating anagen and telogen [19]. These studies provide insights into HF growth and development, yet they have limitations in analyzing underlying mechanisms, primarily due to using single populations prone to seasonal variations. In contrast, we included both shedding and non-shedding sheep with the same genetic background. Using the integrated approach, we combined gene and pathway expression analyses, protein-protein interaction (PPI) network analyses, and TF prediction to elucidate the key regulatory mechanisms in the telogen-anagen transition.

Methods

Animals and sampling

A Dorper flock from Ningxia Zhongmuyilin Livestock Products Stock, located at latitude 38°35’ and an elevation of 1,100 m. Seventeen healthy Dorper ewes, about 2 years old and of similar weight, were selected: nine were shedding and eight were non-shedding, all under identical feeding conditions. To collect their skin tissue, the animals were intravenously anesthetized with xylazine hydrochloride (1.0–2.0 ml/100kg). Once they lay on their sides, samples were taken using surgical scissors from the lateral midsection. Following skin alcohol disinfection, approximately 2 cm2 of skin tissue was excised (see Fig. 1A) with surgical scissors. The wounds were sutured and disinfected using a special surgical trigon and absorbable sutures. The sheep were monitored for health and retained for breeding, with skin tissues stored in liquid nitrogen. Skin tissue samples were collected on September 27, 2019 (anagen), January 3, 2020 (telogen), and March 17, 2020 (early anagen). Additionally, bodyside wool from 17 ewes was collected on March 17, 2020. The shedding and non-shedding phenotypes of the ewes were monitored over two years and reassessed as stable on May 13, 2020. Ultimately, RNA-seq and RT-qPCR experiments were conducted on five complete shedding ewes (S1, S2, S3, S4, and S5) and three non-shedding ewes (N1, N2, and N3) representing the best extreme phenotypes.

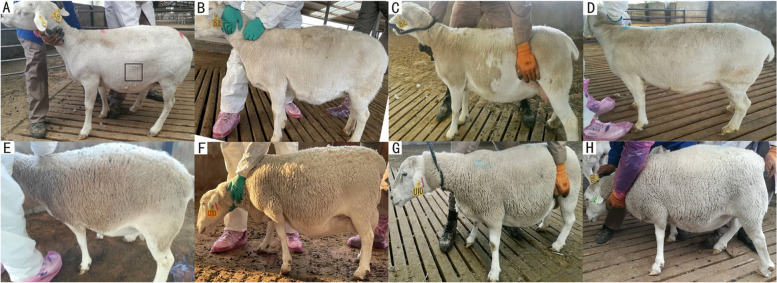

Fig. 1.

Shedding phenotypes of extreme individuals. A-D The phenotype of the same sheep in shedding sheep group (S) at four different time points: September 2019 (anagen), January 2020 (telogen), and March 2020 and May 2020 (early anagen). Shedding occurred mostly in C, with almost complete shedding in D. In A, the sample collection location is marked with a black square. E-H The phenotype of the same sheep in the non-shedding sheep group (N) across the four different time points

Determination of wool phenotype

On 17 March 2020, the straightened lengths of coarse and fine wool were measured using a 15 cm ruler. Wool diameters were assessed with a microscope projector CYG-055 C (Shanghai Optical Instrument Factory); the wool was divided into 16 parts, and 4 were randomly selected for counting. This count was then multiplied by 4 and divided by 9 (the sheared wool area) to calculate the density. Data were analyzed using SPSS23.0.

Total RNA extraction, cDNA library construction, and Illumina sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from each skin sample by grinding in liquid nitrogen with Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The quality and concentration of RNA were assessed using a spectrophotometer (IMPLEN, CA, USA). For each skin sample, 24 RNA libraries were constructed, representing three developmental time points of in vivo HFs. Poly (A) mRNA was isolated using oligo (dT), fragmented, and reverse transcribed with random primers. Double-stranded cDNAs were synthesized using RNase H and DNA polymerase I, then purified using QiaQuick PCR. The cDNA was sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 4000 platform by GeneDenovo Co, Guangzhou, China.

RNA-sequencing data analysis

Raw image data from sequencing were transformed into sequence data by base calling. This raw data was then filtered to obtain clean data by removing reads with adapters, poly-N > 10%, and low-quality reads (> 50% of bases with Phred quality scores < 5%). The Phred score (Q20) and GC content of the clean data were calculated. All subsequent analyses used this high-quality data. The clean reads were mapped to the sheep reference genome (Oar_rambouillet_v1.0) using HISAT2. Based on the comparison results, Stringtie was used to reconstruct transcripts and the FPKM method calculated the expression levels of each transcript. DESeq2 was used to analyze the DEGs between the two groups, calculating the probability of hypothesis testing (p-value) and performing multiple hypothesis testing corrections to obtain the FDR (false discovery rate) value. The fold change (FC) was calculated, and genes with FDR < 0.05 and |log2 FC|≥1 were identified as DEGs.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining of skin samples

Skin samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for over 48 h, washed, dehydrated, and cleared, then impregnated in paraffin and embedded. The resulting wax blocks were sectioned serially (5 μm) longitudinally with a microtome (KD-1508, Jinhua, China). For paraffin section preparation, the fixed samples were dewaxed with xylene, hydrated through graded alcohols, stained, dehydrated, cleared with xylene, and sealed with neutral gum. Morphological changes in the skin were examined using a light microscope (MSHOT, Guangzhou, China).

GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analyses

To further understand the biological function of each pattern DEGs, GO and KEGG enrichment analyses were performed using OmicShare tools, a free online platform (https://www.omicshare.com/tools). Q-value ≤ 0.05 for GO and p-value ≤ 0.05 for KEGG were considered significant as shown in Fig. 5.

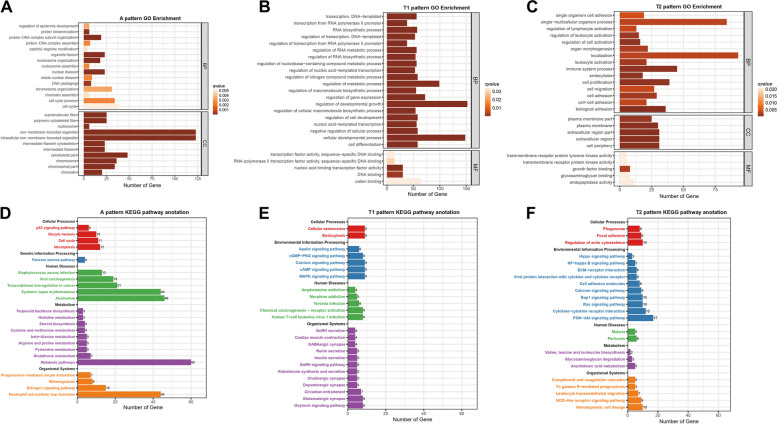

Fig. 5.

GO and KEGG enrichment analysis of the three DEG patterns. A-C GO enrichment analysis results of A-pattern DEGs, T1-pattern DEGs, and T2-pattern DEGs, respectively. The x and y-axes represent the gene counts and different GO terms. D-F KEGG enrichment results of A-pattern DEGs, T1-pattern DEGs, and T2-pattern DEGs, respectively. The x- and y-axes indicate the gene counts and the KEGG pathway names

PCA and pattern analysis

FPKM values from 24 sheepskin samples were used to perform the PCA using OmicShare tools. 2536 DEGs were subjected to hierarchical analysis using the ‘hclust’ function. The cluster dendrogram was fragmented using the ‘complete’ function to classify genes. ClusterGVis R software package was used to analyze pattern-specific DEGs. Trend line graphs are used to present the expression of genes clustered in the heatmap using the kmeans method. For pattern clustering, we used mfuzz, a soft clustering method based on the fuzzy C-means (FCM) clustering algorithm, and the membership values of the genes were used to determine the degree of belonging to the clustered group.

PPI network construction and TFs prediction

PPI network analyses were performed on pattern DEGs using the STRING database (https://string-db.org, version 12.0), selecting interactions with a combined score > 0.4 as significant. Cytoscape (version 3.10.1) was used to visualize the network and present core and hub gene biological interactions. CytoHubba (version 0.1) in Cytoscape used MCC to calculate the topological parameters of nodes and identify hub genes in the co-expression networks. The BMKCloud platform (www.biocloud.net) aligned the genetic sequence data with the transcription factor database (AnimalTFDB).

Real-time fluorescent quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) detection

To verify the sequencing results, six DEGs were selected, and GADPH was the internal reference gene for RT-qPCR verification. Total RNA was converted into cDNA using MightyScript Plus First Strand cDNA Synthesis Master Mix (gDNA digester) (Sangon, Shanghai, China). qPCR was conducted using TB Green Premix Ex Taq (2X) (Tli RNaseH Plus), and ROX plus (TAKARA, Dalian, China). Primer Premier 5.0 software was used to design the primers (Table 1), which were purchased from Zhongke Yutong Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Xianyang, China).

Table 1.

Primer information

| Gene name | Primer sequence (5’−3’) | Tm/℃ | Product Length (bp) | Accession Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAPDH |

F: TGACGCTCCCATGTTTGTGA R: GCGTGGACAGTGGTCATAAGT |

50–60 | 162 | NM_001190390.1 |

| COL1A2 |

F: AATGGTGGCACCCAGTTTGA R: CAGCCTTTTTCAGGTTGCCA |

55.4 | 172 | XM_004007726.6 |

| FGF5 |

F: ACTCCATGCAAGTGCCAA R: GCTGCTCCGATTGCTTGAAT |

54 | 227 | NM_001246263.2 |

| FGF10 |

F: TGTGCGGAGCTACAATCACC R: ATCTCCAGGATACTGTACGGG |

57.5 | 138 | NM_001009230.1 |

| HSPA8 |

F: GTGAACGTGCCATGACCAAG R: TTGCTCAAGCGGCCCTTAT |

56.4 | 202 | XM_012095633 |

| FGFR1 |

F: TCCGTACTGGACGTCACCA R: GGTGGCATAACGGACCTTGT |

57.4 | 181 | XM_060407149.1 |

| FOS |

F: AGTGCCAACTTCATCCCAAC R: AGCCATCTTATTCCTTTCCCTTC |

58.3 | 282 | NM_001166182.1 |

Results

Phenotypic analysis of wool and identification of HF cycle stages

Phenotypic results show that most fine wool in shedding sheep group (S) had shed by March (Fig. 1B) and almost completely by May (Fig. 1C). No shedding occurred in the non-shedding sheep group (N) from September to May of the following year (Fig. 1E-H). After phenotypic observation, coarse and fine wool measurements were compared between S and N (Table 2). The length, diameter, and density of coarse wool were higher in S than in N (P < 0.05, P < 0.01, and P < 0.05, respectively). The straightened length of fine wool in S was less than half of that in N (P < 0.01), consistent with observed phenotypes (Fig. 1C, G). The shorter fine wool length was influenced by the catagen and telogen stages, while in N, fine wool continued to grow.

Table 2.

Coarse and fine wool phenotypes of S and N

| Group | Number (only) | Coarse wool straightened length(cm) | Coarse wool diameter(µm) | Course wool Density Number/cm2 | Fine wool straightened length (cm) |

Fine wool diameter(µm) | Fine wool density Number/cm2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | 9 | 1.44 ± 0.18a | 163.39 ± 9.25A | 41.13 ± 3.31a | 2.24 ± 0.25B | 24.22 ± 1.44 | 171.96 ± 8.99 |

| N | 8 | 0.99 ± 0.12b | 86.99 ± 9.58B | 29.83 ± 2.82b | 5.84 ± 1.16A | 25.14 ± 1.18 | 174.89 ± 8.27 |

S exhibited longer, thicker, and denser coarse wool compared to N. However, the fine wool in S was shorter than that in N. Different uppercase letters A and B signify extremely significant differences (P < 0.01), while differing lowercase letters a and b indicate significant differences (P < 0.05). No letters denote no significant differences

Furthermore, the HF cycle stages for S in September of the first year, January of the first year, and March of the following year were identified. September is marked anagen, initiated by cooler temperatures and shorter days, stimulating vigorous wool growth. January was telogen, halting wool growth. The telogen structure was also confirmed in HF tissue sections (Figure S1. A-B) [20]. March represented early anagen as new wool began to jack up the old. (Figure S1. C) [21]. Sheepskins in May still retained coarse wool, which is consistent with the findings of Zhu et al. [22, 23]. This showed differences in HF cycles for coarse and fine wool.

To explore the regulatory mechanisms of hair cycle transitions between telogen and anagen, we conducted RNA-seq and transcriptome analysis.

Sequencing data quality control analysis

After filtering out adaptor reads and low-quality sequences, the proportion of high-quality data was above 99%, with GC content ranging from 48.51 to 52.49%, and all Q30 values exceeding 92.4%. Over 93.65% of clean reads mapped to the sheep reference genome (Table S1). These results confirmed the reliability of the sequencing data for further analysis.

Verifying the division of the HF cycle stages by marker genes and KERATINs

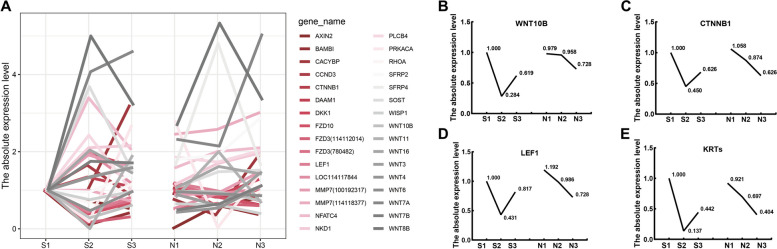

The Wnt/β-catenin pathway is crucial for anagen in HFs, with expression levels corresponding to follicle stages [24]. Analysis of 32 DEGs in the Wnt pathway showed 8 genes with consistent expression trends, including marker DEGs Wnt10B, CTNNB1, and LEF1 [9, 25, 26] (Fig. 2B-D). The trend for 9 other genes in the Wnt pathway was opposite to that observed in Fig. 2 (Table S2). Studies have linked KERATINs (KRTs), regulated by LEF1 in the Wnt pathway, to hair growth [27]. RNA-seq identified 57 KRTs, with 32 showing expression trends aligned with marker genes of the Wnt pathway (Fig. 2E).

Fig. 2.

DEGs of Wnt signaling pathway and KRTs. A Twenty genes in the Wnt signaling pathway showed similar changes in S (S1,anagen; S2,telogen; S3,early anagen) and N (N1-N3, slow growth). B-E Expression trend of marker genes in the Wnt pathway and KRTs. Figures B, C, and D illustrate the expression trends of Wnt10B, CTNNB1, and LEF1. Figure E shows merged expression trends in 32 differentially expressed KERATINs (KRTs). The average FPKM value of the 32 keratin groups S and N in each period was separately divided by the average FPKM value of S1 to obtain the absolute expression level value

Expression patterns of marker genes and KRTs corresponded with HF cycle stages. In the S group, gene expression peaked in S1 and was lowest in S2, increasing slightly in S3. In the N group, gene expression decreased gradually, with similar levels in N3 and S3, indicating comparable HF development stages. WNT and KRT expression highlighted differing HF development stages between S and N, with S exhibiting a distinct HF cycle and N in a slower growth phase without a cycle. These results align with our phenotypic observations (Fig. 1).

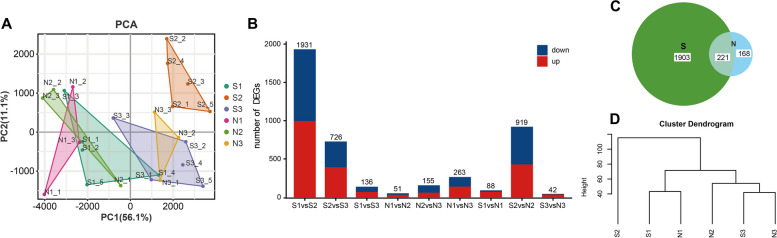

Sample PCA and DEGs analysis

PCA was used to analyze the expression of all genes (Fig. 3A). The samples from S1, N1, and N2 overlapped significantly, while S3 and N3 showed greater overlap, indicating similarity in these stages. Cluster S2 was more isolated, highlighting its uniqueness.

Fig. 3.

Sample PCA and DEGs analysis. A PCA of 24 samples. Every stage in each group was clustered; especially, 5 individuals in the S2 stage were well clustered. N1, N2, and S1 were grouped, while S3 and N3 were grouped having similar expression profiles. B The number of DEGs in 9 comparisons. There were more DEGs between S2 and the other three stages (S2, S3, N2) comparisons, indicating the specificity of the S2 stage. C Venn diagram of DEGs between S and N. S with a clear HF cycle had more DEGs. D Cluster dendrogram of DEGs at different stages of S and N. S2 was grouped into a single cluster, indicating that S2 was different from others

DEGs comparisons involved nine groups, displaying both up- and down-regulated genes as indicated in Fig. 2B. The S1-vs-S2 comparison revealed 1931 DEGs, S2-vs-S3 had 726 DEGs, and S2-vs-N2 had 919 DEGs; the other six comparisons showed fewer DEGs. This pattern emphasizes the unique nature of S2, the telogen stage, and its high number of DEGs compared to other stages (Fig. 3B). According to Fig. 3D, the cluster dendrogram of DEGs grouped S1 and N1 in one group, while S2 formed a separate cluster, aligning with findings in Fig. 3A. This result underscores the distinct expression profile of S2. Notably, DEGs of N2 clustered with S3 and N3, whereas genes of N2 were similar to that of N1 and S1 (Fig. 3A). This suggests gene expression similarities in the decline phase in N, the slow growth stage, with other stages.

Gene expression patterns analysis

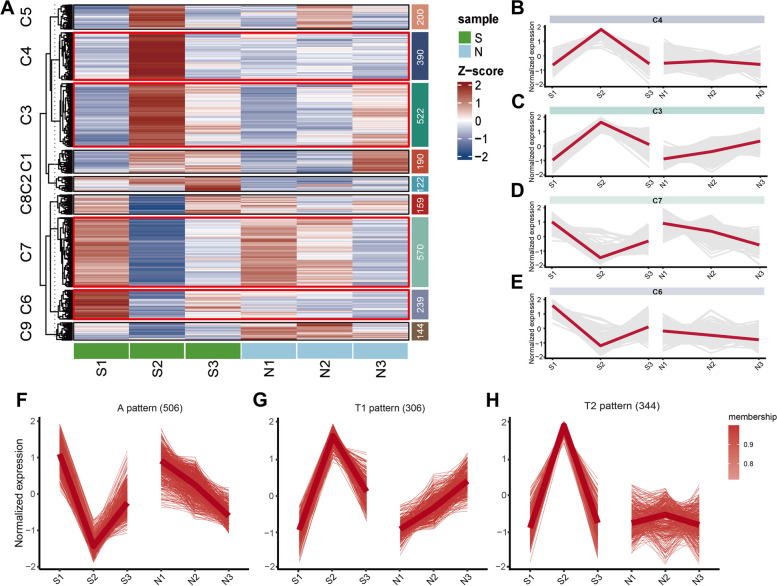

To investigate gene expression patterns, cluster heatmap analysis was conducted on DEGs (Fig. 4A). Results showed that genes in clusters C6 and C7 had the highest expression in S1 and the lowest in S2, with an increase in S3 (Fig. 4D, E), similar to observations in Fig. 2B-E. Cluster C3 showed opposite trends to C6 and C7, while C4 was highly expressed only in S2 (Fig. 4C, B). After removing chaotic gene trends in the four clusters, three patterns of DEGs were identified (Fig. 4F-H). Genes with the highest expression in anagen, lowest in telogen, and increasing during early anagen were labeled as ‘A pattern’ (Fig. 4F). Genes with the highest expression in telogen, lowest in anagen, and decreasing during early anagen were labeled as ‘T1 pattern’, contrasting with A-pattern genes (Fig. 4G). It is speculated that A-pattern and T-pattern genes may synergistically influence HF growth and development. Genes only showing peak expression in S2 were classified under the ‘T2 pattern’, indicating their critical regulatory role in telogen (Fig. 4H). A total of 506 A-pattern DEGs, 306 T1-pattern DEGs, and 344 T2-pattern DEGs were identified.

Fig. 4.

Gene expression patterns analysis. A Heatmap of DEG expression levels, with the high score marked in red and the low score marked in blue. The x-axis represents the HF stages of S and N, while the y-axis represents the normalized FPKM of genes in each stage. B-E Visualization of C4, C3, C7, and C6 clusters in heatmap. F-H Fuzzy c-means clustering identified three distinct temporal patterns of DEG expression: A pattern (the highest gene expression in anagen in group S, the lowest in telogen, and the second highest in early anagen; the gene expression in N decreased slowly), the T1 pattern (the lowest gene expression in anagen in group S, the highest in telogen, and the second lowest in early anagen; the gene expression in N increased slowly), and the T2 pattern (only high expression in the telogen which was S2)

GO and KEGG pathway analysis of DEG expression patterns

GO analysis revealed that A-pattern DEGs were significantly enriched in the Biological Process (BP) and Cell Component (CC) functional categories (Fig. 5A). In BP, terms like regulation of epidermal development, cell cycle process, and cell cycle were closely associated with HF development. In CC, elements such as supramolecular fiber, polymeric cytoskeletal fiber, and nucleosome play roles in preserving HF cell structural integrity and controlling HF growth and development. T1-pattern DEGs showed enrichment mainly in BP and Molecular Function (MF) categories (Fig. 5B). In BP, terms such as regulation of cell development, negative regulation of cellular process, and cellular developmental process were prevalent, aiding in maintaining follicle cell stability and preparing for the next HF cycle. In MF, terms including transcription factor activity sequence-specific DNA binding and RNA polymerase II transcription factor activity, and sequence-specific DNA binding highlight the importance of transcription factors in HF transcriptional regulation during telogen. T2-pattern DEGs were significantly enriched in the BP, CC, and MF categories, linked with resting HF structure, promoting HF cell proliferation and migration (Fig. 5C).

By KEGG enrichment analysis, 245 pathways for A-pattern DEGs, 203 for T1-pattern DEGs, and 253 for T2-pattern DEGs were identified (Fig. 5D-F). In the A-pattern, the estrogen signaling pathway in organismal systems and the cell cycle in cellular processes were closely related to HF growth and cycle processes [28, 29]. The p53 signaling pathway, implicated in cell differentiation and programmed cell death, was also highlighted (Fig. 5D). For T1-pattern DEGs, genes enriched in cellular senescence may reflect the declining proliferation capacity and physiological function of HF cells. The MAPK signaling pathway, related to HF growth and development, was enriched in Environmental Information Processing (Fig. 5E) [30]. T2-pattern results showed enrichment in the regulation of actin cytoskeleton in cellular processes, along with Hippo, NF-kappa B, and PI3K-Akt signaling pathways in Environmental Information Processing. These pathways play crucial roles in the HF cycle in telogen. Fc gamma R-mediated phagocytosis in Organismal Systems may be vital for maintaining cell quiescence (Fig. 5F).

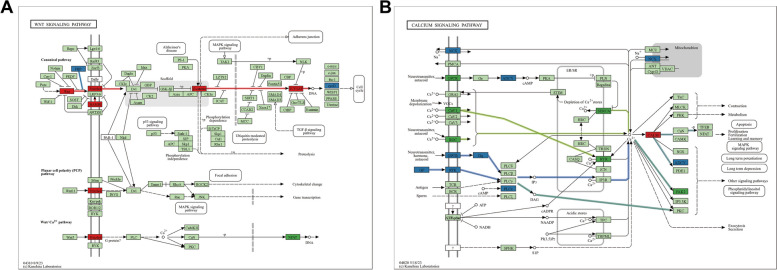

Analyzing expression patterns pathway

Based on KEGG enrichment analysis, three pattern-specific DEGs were counted (Table S3). After analyzing the distribution of these DEGs across KEGG pathways, specific expression patterns in HFs were identified. Five pathways showed an A-pattern, five exhibited a T1-pattern, one demonstrated a T2-pattern, and six were active in both T1 and T2 (Table 3). For instance, the Wnt signaling pathway was identified as an A-pattern in Fig. 6A. It included six A-pattern genes and one T2-pattern DEG predominantly located in the canonical Wnt signaling pathway. The calcium signaling pathway, functioning in both T1 and T2 patterns, included pathways linked to telogen with eight T1-pattern and eight T2-pattern DEGs shown in Fig. 6B (Table 3). Furthermore, the trend of gene expression in these pathways and the regulatory relationships between genes were examined to see if they aligned with the three identified patterns (A, T1, and T2) (Figure S2).

Table 3.

Classification of pathway expression patterns

| Type | Pathway | A-pattern DEGs | T1-pattern DEGs | T2-pattern DEGs | All pattern DEGs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A pattern | Wnt signaling pathway | 6 | 0 | 1 | 7 |

| Glutathione metabolism | 6 | 0 | 0 | 6 | |

| Cell cycle | 7 | 0 | 0 | 7 | |

| Arginine and proline metabolism | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | |

| Ferroptosis | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| T1 and T2 pattern | PI3K-Akt signaling pathway | 1 | 4 | 15 | 20 |

| Calcium signaling pathway | 0 | 8 | 8 | 16 | |

| Fc gamma R-mediated phagocytosis | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 | |

| Ras signaling pathway | 0 | 5 | 9 | 14 | |

| Regulation of actin cytoskeleton | 0 | 4 | 7 | 11 | |

| Chemokine signaling pathway | 0 | 3 | 2 | 5 | |

| T1 pattern | TGF-beta signaling pathway | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| AMPK signaling pathway | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |

| NF-kappa B signaling pathway | 0 | 4 | 2 | 6 | |

| Notch signaling pathway | 0 | 2 | 1 | 3 | |

| Gap junction | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 | |

| T2 pattern | JAK-STAT signaling pathway | 0 | 1 | 7 | 8 |

Fig. 6.

Pathway annotations of A, T1, and T2 DEGs. A Pathway map of the WNT signaling pathway. B Pathway map of the calcium signaling pathway. Red represents A-pattern genes and A-pattern pathway, green represents T1-pattern genes and T1-pattern pathway, blue represents T2-pattern genes and T2-pattern pathways, and light green represents background genes. A white background with a rounded rectangle indicates any other pathway

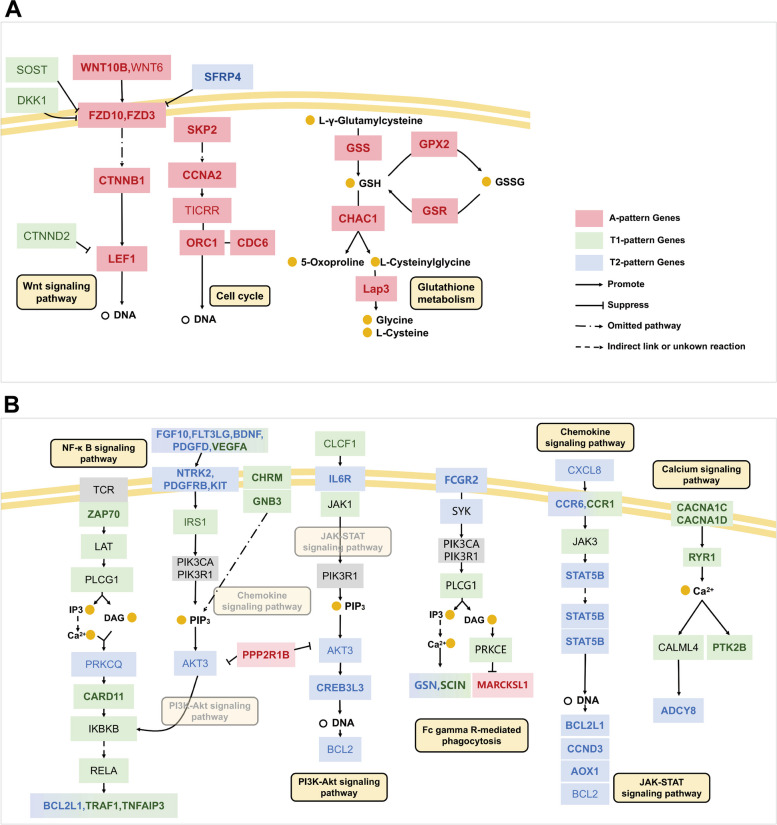

Construction of regulatory networks using critical pattern pathways

Based on pattern pathways and their corresponding DEGs, two regulatory networks of the critical signaling pathway were constructed as shown in Fig. 7. Figure 7A includes three A-pattern signaling pathways: the typical Wnt signaling pathway, cell cycle, and glutathione metabolism. In the Wnt signaling pathway, A-pattern DEGs such as WNT10B, FZD10, FZD3, CTNNB1, and LEF were highlighted in bold red. Past research has reported that Wnt ligands WNT6, WNT10B, and LEF1, upregulated by hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), influence HF growth [12]. In the Cell cycle pathway, the knockout of SKP2 led to apoptosis of HF cells [31]. CCNA2 was found crucial for HF formation and growth [32]. The Glutathione metabolism pathway helped protect HF cells from oxidative stress.

Fig. 7.

Regulatory networks of critical pattern pathways. A The A-pattern regulatory network of the critical pathways (including 3 A-pattern pathways, GSH: glutathione; GSSG: glutathione disulfide). B The T-pattern regulatory network of critical pathways (including 1 T1 pathway, 1 T2 pathway, and 4 T1 and T2 pathways). A-pattern DEGs are shown in bold red. DEGs and genes showing an A-pattern trend are in light red and light black, respectively. Similarly, T1-pattern DEGs are shown in bold green. DEGs and genes showing a T1-pattern trend are in light green and light black, respectively. T2-pattern DEGs are shown in bold blue. DEGs and genes showing a T2-pattern trend are in light green and light black, respectively. Genes with unclear trends, which may be involved in tissues other than HFs, are shown in grey, while metabolites or intermediates are shown as orange dots. The yellow oval represents the pathway

In Fig. 4B, the T1 and T2 pattern pathways map displayed a complex arrangement with four pathways acting in both T1 and T2, one T1-pattern pathway, and one T2-pattern pathway. The PI3K-AKT, calcium, Fc gamma R-mediated phagocytosis, and chemokine pathways were part of both T1 and T2 patterns. In the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway, growth factors (FGF10, FLT3LG, BDNF, PDGFD, VEGFA) bound to receptor tyrosine kinases (NTRK2, PDGFRB, KIT), promote PIP3 production through PI3K class IA genes PIK3RA and PIK3R1. This activation of AKT3, regulated by the Chemokine pathway, influences the expression of the NF-κB pathway. In the Fc gamma R-mediated phagocytosis pathway, FCGR2 bound with SYK, activates the PI3K-Akt and calcium signaling pathways, promoting expression of GSN and SCIN while inhibiting MARCKSL1. In the calcium signaling pathway, CACNA1C and CACNA1D promote RYR1, further enhancing ADCY8 and PTK2B expression in telogen. In the chemokine signaling pathway, CXCL5 binds with CCR6 and CCR1, promoting the JAK-STAT signaling pathway. The NF-κB pathway, a T1 pattern pathway, is activated when Zap70 stimulates LAT, which activates PLCG1 via the calcium signaling pathway, upregulating BCL2L1, TRAF1, and TNFAIP3 in telogen. The JAK-STAT signaling pathway, a T2 pattern pathway, is influenced by upstream elements of the chemokine pathway and also affects the PI3K-Akt pathway.

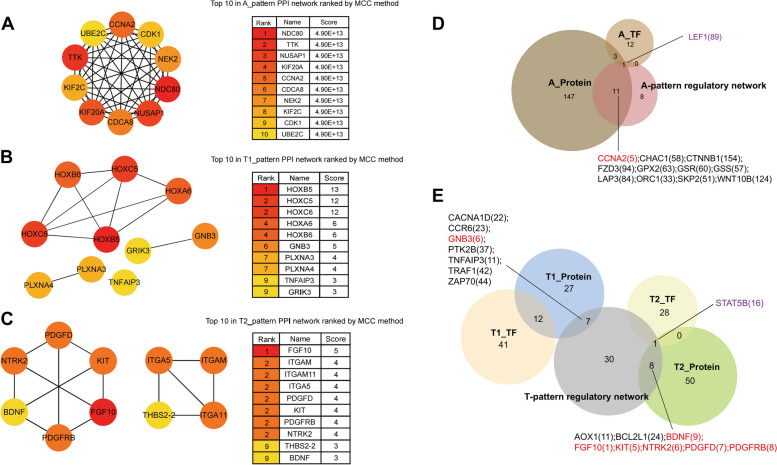

Identification of key genes in key pathways and prediction of TFs of key pathways

To investigate the key genes in critical pathways, pattern-DEGs-associated proteins were identified through PPI analysis using MCC scoring. This analysis identified 162 A-pattern proteins, 46 T1-pattern proteins, and 59 T2-pattern proteins (Table S4). The best TFs were also predicted, resulting in 19 A-pattern TFs, 53 T1-pattern TFs, and 29 T2-pattern TFs (Table S5). Key genes including one A-pattern, one T1-pattern, and six T2-pattern genes ranked in the top 10 by MCC scores appeared in the pattern regulatory network of critical pathways (Fig. 8). CCNA2, a key gene in the cell cycle pathway, and LEF1, a significant TF in the Wnt signaling pathway, were noted in blue in Fig. 8E. GNB3, a high-scoring T1-pattern gene, is upstream in the chemokine pathway. Key genes FGF10, BDNF, PDGFD, PDGFRB, NTRK, and KIT were identified between the T-pattern network and T2-pattern protein (Fig. 8C, E). Additionally, STAT5B was recognized as an important T2-pattern TF.

Fig. 8.

Identification of key genes and predicted TFs in key pathways. A-C The PPI network of the top 10 DEGs pattern and its ranking results. D The Venn diagram consisted of three components: A-pattern predicted proteins by PPI with MCC score (brown), A-pattern regulatory network of key pathways (red), and A-pattern predicted TFs (yellowish brown). E The Venn diagram included T1-pattern predicted proteins (blue), T2-pattern predicted proteins (green), T-pattern regulatory network of key pathways (grey), and T1 and T2 predicted TFs (orange and yellow). Genes ranked in the top 10 with high scores in the PPI network and appearing in the pattern regulatory network are displayed in red, while the forecasted TFs in the pattern regulatory network are depicted in purple. The numbers in parentheses represent the rank of predicted proteins by the MCC method

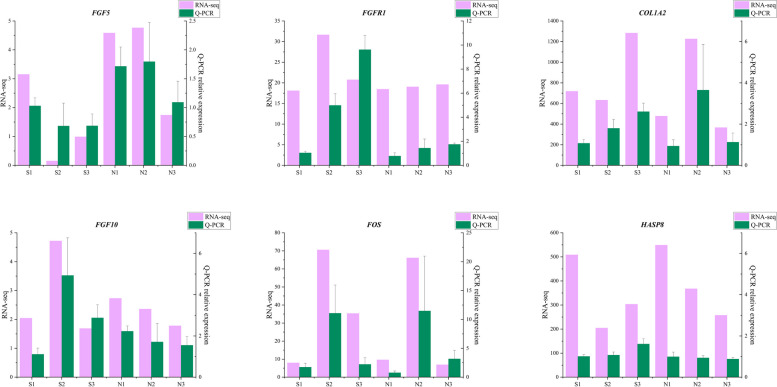

Validation of DEGs by RT-qPCR

The expression of six DEGs, namely COL1A2, FGF5, FGF10, FOS, FGFR1, and HSPA8, was validated by RT-qPCR. Their expression profiles aligned with the RNA-seq results (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

RT-qPCR validation of 6 DEGs

Discussion

This study employed reliable design and analytical methods to determine the regulatory mechanisms of the telogen-anagen transition in the hair follicle cycle. Initially, an ideal experimental model was established with S as the experimental group and N as the control. This model reduced the false-positive rate, as seen with clusters C5 and C8 in Fig. 4A. These genes fluctuated similarly with seasonal changes in S and N but were unrelated to the HF cycle. Filtering out these genes allowed for specific identification of genes and pathways associated with the HF cycle. For instance, Yang et al. only selected Inner Mongolian Arbas white cashmere goats as a single experimental group to investigate the HF cycle, which increased the false positive probability [33]. Additionally, Su et al. found STC2 associated with the HF cycle or other physiological functions, but in this study, it was a seasonal DEG (categorized under cluster C5) [34]. Next, genes and pathway expression patterns were identified. Currently, expression pattern analysis related to HF development is an effective method. For example, Chun Li et al. analyzed the expression patterns of stage-specific and melatonin-triggered genes, constructing a regulatory pathway model for melatonin-triggered HF cycles [35]. In this study, 506 A-pattern DEGs, 306 T1-pattern DEGs, and 344 T2-pattern DEGs were screened, discovering five A-pattern signaling pathways, six T1 and T2 pattern signaling pathways, five T1-pattern signaling pathways, and one T2-pattern signaling pathway. These pattern genes and pathways were associated with HF development.

Telogen plays an important role in the development of HFs. Six T1 and T2-pattern pathways, five T1-pattern pathways, and one T2-pattern pathway were identified by pattern pathway analysis. Key signaling pathways include NF-κB signaling, PI3K-Akt signaling, JAK-STAT signaling, Fc gamma R-mediated phagocytosis, calcium signaling, and chemokine signaling. While previous research focused on the PI3K-Akt signaling in transitioning from telogen to anagen, it has been shown to enhance dermal papilla cell proliferation via WNT/β-catenin signaling, thus inducing hair growth [36–38]. However, this study found PI3K-Akt signaling (T1 and T2) also crucial in telogen, due to its role in maintaining follicles in this phase [39]. Receptors upstream of PI3K-AKT influence FcγR-mediated phagocytosis (T1 and T2), JAK-STAT (T2), and chemokine signaling (T1 and T2). FcγR-mediated phagocytosis may contribute to HF atrophy. Wiener et al. reported high GSN expression during the telogen phase in canine transcriptome analysis [40]. The AMPK signaling pathway (T1), FcγR-mediated phagocytosis, and NF-Kappa B signaling (T1) all transmit signals through calcium ions, highlighting calcium signaling’s intermediary role (T1 and T2). NF-κB signaling, identified as a T1 pattern, was associated with strong activity in the secondary hair germ during late telogen and early anagen phases, indicating its potential in activating HF stem/progenitor cells during anagen induction, as observed in NF-κB reporter mouse models by Krieger et al. [41]. In the JAK-STAT signaling pathway, the target gene BCL2, crucial for maintaining the telogen stage as an apoptosis inhibitor [42], was identified. Topical application of JAK inhibitors can induce hair growth from resting mouse HFs, suggesting JAK-STAT signaling is essential for keeping HF stem cells quiescent [43].

Key genes in key pathways were identified through PPI analysis, including one A-pattern key gene, one T1-pattern key gene, and six T2-pattern key genes. Additionally, TFs in the key pathways were identified, featuring one predicted A-pattern TF and one predicted T2-pattern TF. The A-pattern key gene CCNA2 is regulated by CDKN1B, which promotes the synthesis of the TICRR complex in the cell cycle. Chen SJ and others emphasized the critical role of CCNA2 in the formation and growth of HFs [32]. TF LEF1 is repeatedly reported as vital in the growth and development of HFs [44–46]. GNB3, a key T1-pattern gene, acts as a receptor in the Chemokine pathway. It plays a crucial role in the telogen stage, a finding not previously reported. The T2-pattern key genes FGF10, PDGFD, PDGFRB, and NTRK2 are located upstream in the calcium signaling pathway, Ras signaling pathway, and PI3K-Akt signaling pathway. BDNF and KIT are also positioned upstream in these pathways. Six key T2-pattern genes appear to initiate these pathways significantly. It is notable that PDGFD and PDGFRB, a pair of corresponding signaling molecules, show differences in their anagen and telogen phases by more than threefold. Valentina Greco and colleagues observed that FGF10 and FGF7 are expressed in the dermal papilla of HFs during telogen [47]. BDNF shows high expression during the anagen VI phase of the human hair cycle. However, only weak positive BDNF staining is detected in the outer root sheath and secondary hair germ epithelium of resting HFs, indicating its critical role in the transition from anagen to telogen [48]. This finding contradicts our conclusions, necessitating further validation.

An important regulatory role in the transition from telogen to anagen has been identified among A, T1, and T2 patterns. A and T1 patterns, which are completely opposite, may interact synergistically. During the anagen stage, A-pattern genes showed high expression, while T1-pattern genes were suppressed. Conversely, during the telogen stage, T1-pattern genes showed high expression, while A-pattern genes were suppressed. Additionally, T2-pattern genes exhibited high expression specifically during telogen, without variation in other stages (Fig. 7B, color in blue). T2 genes were primarily located at the initial regulatory point of the pathway, emphasizing their critical role at that stage.

Conclusion

This study identified eight key genes, CCNA2, GNB3, BDNF, FGF10, KIT, NTRK, PDGFRD and PDGFRB, that may play a critical role in HF transition from the telogen to anagen stages. It identified four A-pattern and six T-pattern key pathways in this transition, with the predicted TFs LEF and STAT5B participating in WNT and JAK-STAT signaling, respectively. Additionally, three distinct gene expression patterns were found in the HF cycle. This research provides valuable insights for artificially regulating sheep shedding time. Future studies will validate these findings using immunofluorescence staining, Western blotting, and other experimental methods and explore the specific mechanisms by which these genes influence wool growth in sheep.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Ningxia China Animal Husbandry Yilin Livestock Co., Ltd. (Yinchuan, China) for providing sheep samples.

Abbreviations

- HF

Hair follicle

- DEGs

Differentially expressed genes

- PHFs

Primary hair follicles

- SHFs

Secondary hair follicles

- PPI

Protein-protein interaction

- TFs

Transcription factors

- FC

Fold change

- GO

Gene ontology

- KEGG

Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes

- FDR

False discovery rate

- PCA

Sample principal component analysis

- FCM

Fuzzy C-means

- S

Shedding sheep group

- N

Non-shedding sheep group

- BP

Biological process

- CC

Cell component

- MF

Molecular function

- MCC

Maximal clique centrality

- RT-qPCR

Real-time fluorescent quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Authors’ contributions

X.L.and N.Z. conceived and designed the study. N.Z. and Y.W. analyzed the transcriptome data and contributed significantly to the original manuscript draft. J.W. revised and proofread the manuscript.L.Z. participated in the collection of skin samples and conducted the suturing and disinfection of the wound. Y.W., H.S., X.Y., S.W., and C.W. contributed to the preparation of the materials and experiments. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China “Screening of key molecules and construction of regulatory network about sheep shedding trait” (No. 31960650).

Data availability

The analyzed RNA-seq data are available at the National Center for Biotechnology Information with the accession numbers PRJNA963059.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the College of Animal Science and Technology, Ningxia University, China (NXU-19-018). Animals were ethically treated and with minimal suffering.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Pogodaev V, Parzhanov Z, Azhimetov N, Sergeeva N, Akhynova U, Tenlibayeva A, Mustiyar T. The Dorper breed as a stage in the sustainable development of the agroindustry. Braz J Biol. 2024;83:e278882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang R, Li Y, Jia K, Xu XL, Li Y, Zhao Y, Zhang XS, Zhang JL, Liu GS, Deng SL, et al. Crosstalk between androgen and Wnt/β-catenin leads to changes of wool density in FGF5-knockout sheep. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11(5):407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lei ZH, Sun WB, Guo TT, Li JY, Zhu SH, Lu ZK, Qiao GY, Han M, Zhao HC, Yang BH, et al. Genome-wide selective signatures reveal candidate genes Associated with hair follicle development and wool shedding in Sheep. Genes-Basel. 2021;12(12):1924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mobini B. Histomorphometrical Variations of Hair Follicles of Bakhtiari Sheep at different skin areas. Thai J Vet Med. 2013;43(1):131–5. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cloete SWP, Snyman MA, Herselman MJ. Productive performance of Dorper sheep. Small Ruminant Res. 2000;36(2):119–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schneider MR, Schmidt-Ullrich R, Paus R. The hair follicle as a dynamic Miniorgan. Curr Biol. 2009;19(3):R132–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.He YY, Cheng LX, Wang JQ, Liu X, Luo YZ. Identification of the secondary follicle cycle of Hexi Cashmere Goat. Anat Rec. 2012;295(9):1520–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Müller-Röver S, Handjiski B, van der Veen C, Eichmüller S, Foitzik K, McKay IA, Stenn KS, Paus R. A comprehensive guide for the accurate classification of murine hair follicles in distinct hair cycle stages. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117(1):3–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu GB, Liu RZ, Tang XH, Cao JH, Zhao SH, Yu M. Expression profiling reveals genes involved in the regulation of wool follicle bulb regression and regeneration in Sheep. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(5):9152–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pollott GE. A suggested mode of inheritance for wool shedding in sheep. J Anim Sci. 2011;89(8):2316–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Higgins CA, Westgate GE, Jahoda CAB. From Telogen to Exogen: mechanisms underlying formation and subsequent loss of the Hair Club Fiber. J Invest Dermatology. 2009;129(9):2100–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen D, Jarrell A, Guo C, Lang R, Atit R. Dermal β-catenin activity in response to epidermal Wnt ligands is required for fibroblast proliferation and hair follicle initiation. Development. 2012;139(8):1522–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao WY, Pan XQ, Li T, Zhang CC, Shi NA. Polysaccharides Protect against Trimethyltin Chloride-Induced Apoptosis via Sonic Hedgehog and PI3K/Akt Signaling Pathways in Mouse Neuro-2a Cells. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016;2016:9826726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.St-Jacques B, Dassule HR, Karavanova I, Botchkarev VA, Li J, Danielian PS, McMahon JA, Lewis PM, Paus R, McMahon AP. Sonic hedgehog signaling is essential for hair development. Curr Biol. 1998;8(19):1058–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Plikus MV, Mayer JA, de la Cruz D, Baker RE, Maini PK, Maxson R, Chuong CM. Cyclic dermal BMP signalling regulates stem cell activation during hair regeneration. Nature. 2008;451(7176):340–U348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oshimori N, Fuchs E. Paracrine TGF-β signaling counterbalances BMP-Mediated repression in hair follicle stem cell activation. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10(1):63–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dinh K, Wang QX. A probabilistic boolean model on hair follicle cell fate regulation by TGF-5. Biophys J. 2022;121(13):2638–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu ZH, Yang F, Zhao M, Ma LN, Li HJ, Xie YC, Nai RL, Che TY, Su R, Zhang YJ, et al. The intragenic mRNA-microRNA regulatory network during telogen-anagen hair follicle transition in the cashmere goat. Sci Rep-Uk. 2018;8(1):14227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhat B, Yaseen M, Singh A, Ahmad SM, Ganai NA. Identification of potential key genes and pathways associated with the Pashmina fiber initiation using RNA-Seq and integrated bioinformatics analysis. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):1766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parry AL, Nixon AJ, Craven AJ, Pearson AJ. The microanatomy, cell replication, and keratin gene expression of hair follicles during a photoperiod-induced growth cycle in sheep. Acta Anat (Basel). 1995;154(4):283–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Milner Y, Sudnik J, Filippi M, Kizoulis M, Kashgarian M, Stenn K. Exogen, shedding phase of the hair growth cycle: characterization of a mouse model. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;119(3):639–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang QL, Li JP, Chen Y, Chang Q, Li YM, Yao JY, Jiang HZ, Zhao ZH, Guo D. Growth and viability of Liaoning Cashmere goat hair follicles during the annual hair follicle cycle. Genet Mol Res. 2014;13(2):4433–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhu B, Xu T, Yuan JL, Guo XD, Liu DJ. Transcriptome sequencing reveals differences between primary and secondary hair follicle-derived dermal papilla cells of the Cashmere Goat (Capra hircus). PLoS ONE. 2013;8(9):e76282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rishikaysh P, Dev K, Diaz D, Qureshi WMS, Filip S, Mokry J. Signaling involved in hair follicle morphogenesis and development. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15(1):1647–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li YH, Zhang K, Ye JX, Lian XH, Yang T. Wnt10b promotes growth of hair follicles via a canonical wnt signalling pathway. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36(5):534–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun Y, Zhou YX, Msuthwana P, Liu J, Liu C, Sello CT, Song YP, Feng ZQ, Li SY, Yang W, et al. The role of CTNNB1 and LEF1 in feather follicles development of Anser cygnoides and Anser anser. Genes Genom. 2020;42(7):761–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou P, Byrne C, Jacobs J, Fuchs E. Lymphoid enhancer factor 1 directs hair follicle patterning and epithelial cell fate. Genes Dev. 1995;9(6):700–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Purba TS, Brunken L, Hawkshaw NJ, Peake M, Hardman J, Paus R. A primer for studying cell cycle dynamics of the human hair follicle. Exp Dermatol. 2016;25(9):663–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ohnemus U, Ünalan M, Handjiski B, Paus R. Topical estrogen accelerates hair regrowth in mice after chemotherapy-induced alopecia by favoring the dystrophic catagen response pathway to damage. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;122(1):7–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Öztürk ÖA, Pakula H, Chmielowiec J, Qi JJ, Stein S, Lan LX, Sasaki Y, Rajewsky K, Birchmeier W. Gab1 and Mapk Signaling are essential in the Hair cycle and hair follicle stem cell quiescence. Cell Rep. 2015;13(3):561–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sistrunk C, Kim SH, Wang X, Lee SH, Kim Y, Macias E, Rodriguez-Puebla ML. Deficiency inhibits Chemical skin Tumorigenesis Independent of p27(Kip1) Accumulation. Am J Pathol. 2013;182(5):1854–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen SJ, Liu T, Liu YJ, Dong B, Huang YT, Gu ZL. Identification of single nucleotide polymorphisms in the CCNA2 gene and its association with wool density in Rex rabbits. Genet Mol Res. 2011;10(4):3365–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang F, Liu ZH, Zhao M, Mu Q, Che TY, Xie YC, Ma LN, Mi L, Li JQ, Zhao YH. Skin transcriptome reveals the periodic changes in genes underlying cashmere (ground hair) follicle transition in cashmere goats. BMC Genomics. 2020;21(1):392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Su R, Gong G, Zhang LT, Yan XC, Wang FH, Zhang L, Qiao X, Li XK, Li JQ. Screening the key genes of hair follicle growth cycle in Inner Mongolian Cashmere goat based on RNA sequencing. Arch Anim Breed. 2020;63(1):155–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li C, Feng C, Ma G, Fu S, Chen M, Zhang W, Li J. Time-course RNA-seq analysis reveals stage-specific and melatonin-triggered gene expression patterns during the hair follicle growth cycle in Capra hircus. BMC Genomics. 2022;23(1):140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang X, Chen H, Tian R, Zhang Y, Drutskaya MS, Wang C, Ge J, Fan Z, Kong D, Wang X, et al. Macrophages induce AKT/β-catenin-dependent Lgr5(+) stem cell activation and hair follicle regeneration through TNF. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kang JI, Choi YK, Koh YS, Hyun JW, Kang JH, Lee KS, Lee CM, Yoo ES, Kang HK. Vanillic Acid stimulates Anagen Signaling via the PI3K/Akt/β-Catenin pathway in dermal papilla cells. Biomol Ther. 2020;28(4):354–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang H, Su Y, Wang J, Gao Y, Yang F, Li G, Shi Q. Ginsenoside Rb1 promotes the growth of mink hair follicle via PI3K/AKT/GSK-3β signaling pathway. Life Sci. 2019;229:210–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lippens S, Hoste E, Vandenabeele P, Agostinis P, Declercq W. Cell death in the skin. Apoptosis. 2009;14(4):549–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wiener DJ, Groch KR, Brunner MAT, Leeb T, Jagannathan V, Welle MM. Transcriptome profiling and Differential Gene expression in Canine Microdissected Anagen and Telogen Hair Follicles and Interfollicular Epidermis. Genes-Basel. 2020;11(8):884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krieger K, Millar SE, Mikuda N, Krahn I, Kloepper JE, Bertolini M, Scheidereit C, Paus R, Schmidt-Ullrich R. NF-κB participates in mouse hair cycle control and plays distinct roles in the various pelage hair follicle types. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138(2):256–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Müller-Röver S, Rossiter H, Lindner G, Peters EMJ, Kupper TS, Paus R. Hair follicle apoptosis and Bcl-2. J Invest Derm Symp P. 1999;4(3):272–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang ECE, Dai ZP, Ferrante AW, Drake CG, Christiano AM. A subset of TREM2 + dermal macrophages secretes Oncostatin M to maintain hair follicle stem cell quiescence and inhibit hair growth. Cell Stem Cell. 2019;24(4):654–69. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Zhang Y, Yu J, Shi CY, Huang YQ, Wang Y, Yang T, Yang J. Lef1 contributes to the differentiation of Bulge Stem cells by Nuclear translocation and cross-talk with the Notch Signaling Pathway. Int J Med Sci. 2013;10(6):738–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hawkshaw NJ, Hardman JA, Alam M, Jimenez F, Paus R. Deciphering the molecular morphology of the human hair cycle: wnt signalling during the telogen-anagen transformation. Brit J Dermatol. 2020;182(5):1184–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lin CM, Yuan YP, Chen XC, Li HH, Cai BZ, Liu Y, Zhang H, Li Y, Huang K. Expression of Wnt/β-catenin signaling, stem-cell markers and proliferating cell markers in rat whisker hair follicles. J Mol Histol. 2015;46(3):233–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Greco V, Chen T, Rendl M, Schober M, Pasolli HA, Stokes N, Dela Cruz-Racelis J, Fuchs E. A two-step mechanism for stem cell activation during hair regeneration. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4(2):155–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peters EM, Hansen MG, Overall RW, Nakamura M, Pertile P, Klapp BF, Arck PC, Paus R. Control of human hair growth by neurotrophins: brain-derived neurotrophic factor inhibits hair shaft elongation, induces catagen, and stimulates follicular transforming growth factor beta2 expression. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124(4):675–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The analyzed RNA-seq data are available at the National Center for Biotechnology Information with the accession numbers PRJNA963059.