Abstract

Background

To address the rising demand for urgent care and decrease hospital use, health systems are implementing different strategies to support urgent care patients (i.e. patients who would have typically been treated in hospital) in the community, such as general practitioner (GP) advice lines. The aims of this study were to: identify the support and resources GPs need to manage urgent care patients in the community; assess the need for GP advice lines by primary care services in Australia; and identify the facilitators and barriers to adoption, and strategies to support the sustainability of GP advice lines.

Methods

Qualitative study involving semi-structured interviews with GPs, hospital-based healthcare providers, consumers, and healthcare management, recruited via existing investigator networks and snowballing approach. The interviews were conducted between February and August 2023. Major themes were identified by an iterative and inductive thematic analysis.

Results

We interviewed 16 participants (median age 50, IQR 38–59). Based on the aims of the study, three themes emerged: support and resources for GPs; motivation for GP advice lines; and factors influencing the uptake and sustainability of GP advice lines. Participants reported that better communication from hospital services with GPs is critical to ensure continuity of care between tertiary and primary settings. They also noted that GP advice lines can help increase capacity to manage urgent care patients in the community by providing timely decision-support to GPs. However, a reported barrier to the uptake and ongoing use of GP advice lines was the limited hours of the service. To sustain GP advice lines, participants highlighted a need to broaden the scope of the service beyond the pandemic, conduct rigorous evaluation on health outcomes, and further digitise the service so that a tiered level of support could be provided based on risk stratification.

Conclusions

The benefits of GP advice lines are yet to be fully realised. With increasing technology sophistication, there remain opportunities to further digitise and optimise GP advice lines, whilst ensuring better integration within and across primary and tertiary care services. This is however dependent on continued financial and policy support from the government.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12875-024-02649-1.

Keywords: General practice, Advice lines, Continuity of care, Urgent care

Introduction

Demand for emergency and urgent care has been rising consistently worldwide, with emergency department (ED) visits increasing by as much as 3% to 6% each year [1–3]. An important driver for the growth in ED visits is the presentation of patients with conditions that could potentially be treated in the community [3, 4]. In Australia, between 2022 and 2023, 16% of ED visits were classified as emergencies (i.e., life-threatening conditions), 40% were classified as urgent, and the remainder were semi-urgent or non-urgent [2]. A high prevalence of lower acuity ED presentations contributes to longer waiting times and adverse outcomes for all patients, as well as higher overall healthcare costs [5].

To address the rising demand for urgent care and decrease unnecessary ED use, health systems are implementing different strategies to support urgent care patients (i.e. patients who would have typically been treated in hospital). Strategies to increase out-of-hospital urgent care capacity and improve coordination between General Practice (GP) and hospitals include virtual urgent care models such as [3, 6]: delivering digitally-enabled care remotely to patients at home (i.e. virtual care); and delivering hospital specialist advice remotely to GPs via telephone lines (i.e. GP advice lines) [7, 8]. GP advice lines are telephone hotlines that provide primary care providers with timely access to hospital specialists’ advice [9].

Existing studies of GP advice lines from Canada, the United States, France and Italy have indicated reductions in referrals, ED visits, and hospitalisations, as well as cost-savings and clinician satisfaction associated with the implementation [9–15]. In Australia, studies of telephone communication between GPs and hospital specialists indicate satisfaction, but low awareness and low uptake for the majority of targeted users [16, 17]. This indicates the need for in-depth evaluations of GP advice line services to identify whether and why GPs need these advice lines and to determine the barriers to adoption, facilitators and strategies to support the sustainability of GP advice lines within the Australian context.

This study aimed to: 1) identify the support and resources GPs need to manage urgent care patients in the community in coordination with virtual hospital services; 2) assess the need for GP advice lines by primary care services in Australia; and 3) identify the facilitators and barriers to adoption, and strategies to support the sustainability of GP advice lines.

Methods

Study design

This was a qualitative study involving semi-structured interviews. Reporting follows the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ; Appendix 1). [18] Ethics approval was received from Western Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee (2022/ETH01690), in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research. All participants provided informed consent. This study was funded by Sydney Health Partners and undertaken by Sydney Health Partners’ Virtual Care Clinical Academic Group (CAG). Sydney Health Partners is an accredited research translation centre that seeks to support the implementation of evidence-based practice into clinical practice and service delivery through partnership with academia (the University of Sydney) and local health services. Partners to the Virtual Care CAG include Northern Sydney Local Health District, Sydney Local Health District, Sydney Children’s Hospital Network and Western Sydney Local Health District. These health districts service metropolitan Sydney and the Network is a specialty paediatric service across the state.

Setting and participants

Eligible participants were stakeholders involved in urgent care coordination between primary care and hospital services (clinicians, consumer representatives, healthcare service management staff), including stakeholders directly involved in implementing GP advice lines in different Sydney regions and GP end-users. The four GP advice line services that were the focus of this study were implemented by Sydney Local Health District (SLHD), Northern Sydney Local Health District (NSLHD), Sydney Children’s Hospital Network (SCHN), and Western Sydney Local Health District (WSLHD):

SLHD established a GP advice line supported by GP Liaison Clinical Nurse Consultants, through the Royal Prince Alfred Virtual Hospital [19, 20] to provide assistance and advice to GPs in managing COVID-19 patients in the community.

NSLHD virtual hospital established a GP advice line to support GPs with COVID-19 symptom management and antiviral therapy.

SCHN established an advice line during the COVID-19 pandemic to support GPs in caring for high acuity children in the community.

WSLHD established the GP Specialist advice line as part of the Western Sydney Integrated Care Program, to support GPs in caring for chronic disease patients.

We used a purposive sampling technique, with initial participants identified by the Virtual Care CAG as key stakeholders. Additional participants were later recruited employing passive snowballing methodology i.e. relying on the natural and organic social networks of the Virtual CAG stakeholders and the initial participants. Potential participants were emailed a Participant Information and Consent Form and written consent was obtained prior to the interview.

Data collection techniques

Our semi-structured interview guide (see Appendix 2) was developed based on existing literature and discussion among co-authors and Steering Committee members (including GPs, other clinicians, consumers, healthcare service management staff). All semi-structured interviews were conducted by a researcher (DK) experienced in qualitative interviewing, between 21 February and 2 August 2023 (one via phone call; remaining via video conference). Recruitment ceased once thematic saturation was reached [21]. Interviews were digitally audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Analysis

We used NVivo 1.7.1 (QSR International) to analyse transcripts. Thematic analysis was conducted line by line, using codes developed inductively, i.e. based on the data, using Braun and Clarke’s approach [22]. This approach included data familiarization, coding, generating initial themes, reviewing potential themes, defining and naming themes, and producing the report [22]. Specifically, ABA and LL repeatedly listened to the audio recording and familiarized themselves with the transcribed data by reading it multiple times before coding independently. After initial code generation, the researchers developed themes by merging codes with a shared meaning. Following this, the researchers reviewed the candidate themes to ensure coherent patterns were formed which contributed to the overall narrative and interpretation of the dataset. Finally, to ensure consistency and improve study rigour, the researchers discussed and reported the themes in relation to the dataset and the research aim. The two researchers met frequently throughout data collection and analysis to compare themes. Themes were discussed among the team of investigators until consensus was reached.

Results

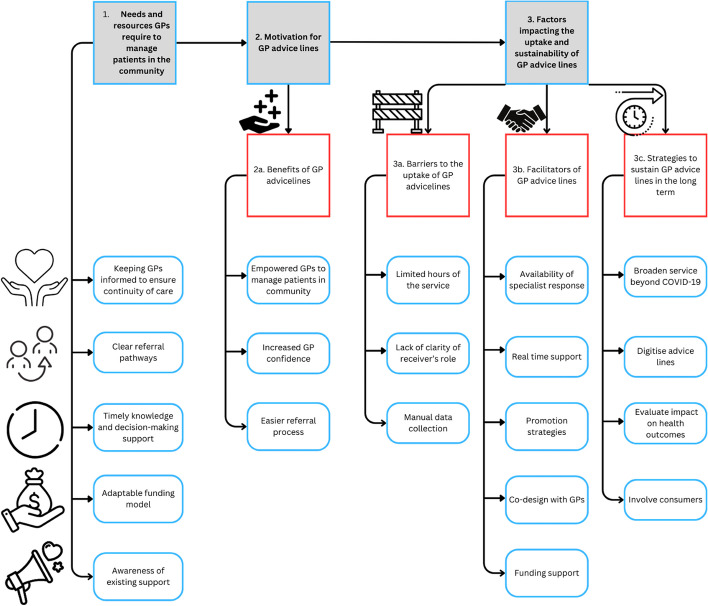

A total of 16 participants were interviewed (median age 50 years; Interquartile range 38–59 years; 9 female), of whom 6 were GPs, 2 were consumer representatives, and others were health service managers (HSM) or healthcare professionals (HCP), some with overlap in functions (Table 1). Participants were from 3 different regions in Sydney: 5 from Northern Sydney, 4 from Central-Eastern and 5 from Western Sydney. Interviews had a mean duration of 39.6 min (range 12.2—66.6 min). Based on the aims of the study, three major themes emerged (Fig. 1): support and resources for GPs; motivation for GP advice lines; and factors influencing the uptake and sustainability of GP advice lines.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 16 interviewees

| Characteristics | Number |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 9 |

| Male | 7 |

| Age Group * |

Overall median (IQR) 50 (38 – 59) |

| 30–39 | 4 |

| 40–49 | 3 |

| 50–59 | 5 |

| 60–69 | 3 |

| Occupation ** | |

| GP | 6 |

| Healthcare service management | |

| Primary Health Networks | 3 |

| Local Health Districts | 3 |

| Clinical role at NSW LHD service | |

| Sydney LHD | 1 |

| Northern Sydney LHD | 1 |

| Western Sydney LHD | 1 |

| Sydney Children’s Hospital Network | 2 |

| Consumer representative | |

| Location of employment | |

| Northern Sydney | 5 |

| Central-Eastern Sydney | 4 |

| Western Sydney | 5 |

| Number of years in current profession | |

| 0–2 | 5 |

| 3–5 | 7 |

| 6 + | 2 |

*Missing data; ** Multiple responses possible; LHD = Local Health District

Local Health Districts (LHDs) are government-funded organizations established in New South Wales, Australia, to deliver healthcare services across specific geographic regions. LHDs are responsible for managing public hospitals, healthcare clinics, and other healthcare institutions within their designated areas

Primary Health Networks (PHNs) are independent organisations funded by the Australian Government to manage primary health care in specific region

Fig. 1.

Illustrative representation of themes and subthemes

Support and resources for GPs to manage urgent care patients in the community

To support the management of urgent care patients in the community in coordination with virtual hospital services, three major needs were reported: keeping GPs informed about hospital care for their patients, clear referral pathways and knowledge and decision-making support.

a. Keeping GPs informed on hospital care for their patients.

Participants reported that keeping GPs in the loop regarding hospital care for their patients is critical to ensure continuity of care between tertiary and primary care. Participants stated that little or no information was being shared with GPs on the hospital care experienced by their patients, stating that: “the internal resident or registrar should be picking up the phone routinely for every admission and talking to the GP, involving the GP in care team meetings, so that they're actually part of the management plan and discharge planning. …we're unaware that they were admitted or discharged. We're just unaware that it even happened” – P11, GP.

b. Clear referral pathways.

Clear referral pathways was identified as a necessity as participants highlighted the complexity of the Australian healthcare system reporting that it is challenging to navigate for GPs particularly for those who gained their qualifications from other countries. For example, a participant said: “So, we need to provide them with really clear pathways in, they need to know who to ring, how to easily get through to someone, who's gonna be on the other end…it can be very difficult for them trying to navigate our system and to know… how to get through to the right department or the right specialist.” – P02, HSM.

It was also reported that there is a need for GPs to be able to refer patients to the hospital in a manner that bypasses the ED for direct access to care when the clinical requirements of the patient are clear: “I think the next step is having the GP able to directly refer patients into the hospital without going through ED for other types of care, and this might mean… treatment of wound care or fractures.” – P012, GP.

c. Knowledge and decision-making support.

Participants reported that it was key to provide knowledge and decision-making support to GPs to help determine whether the patient can be managed in their care or in hospital. For example, a participant said: “I suppose it's sort of critical decisions about whether someone's safe to be managed at home or not.” – P011, GP. Other participants clarified that knowledge support is not about providing generic clinical information but more about providing personalised actionable information based on the unique circumstances of individual patients: “[an] individual scenario needs to be tailored and we need advice on how to tailor it…it's not the clinical information we necessarily need, it's how to apply it.” – P08, GP. It was further noted that one way to provide timely, personalised, and actionable knowledge and decision-making support is through the use of GP advice lines.

Other general practice necessities reported by participants included: better awareness of existing support and having an adaptable funding model to allow GPs to be adequately remunerated for the management of urgent care patients in the community – see Table 2 for additional illustrative quotations.

Table 2.

Illustrative quotes for theme “Needs/support and resources GPs require to manage urgent care patients in the community”

| Keeping GPs informed to ensure continuity of care |

“I would've thought that by this day and age we would've had a way where a doctor's referral was flagged on a hospital system with a discharge summary and other documentation was automatically sent back to the GP.” [Participant 16; male; 50 years] “Once the patient gets to ED, the GP then loses track, completely, of what's going on with the patient (…) [GPs] often express frustration that hospitals aren't very good at thinking about what happens when the patient leaves the front door of the hospital. They're not very good at pre-planning discharge, and the quality of their discharge summaries sometimes is inferior. Sometimes the discharge summaries come too late, when the GP needed really critical information about medication.” [Participant 2; female;52 years] “When you give the patient (…) a referral letter, you're never sure if the doctor is actually gonna get it. Does it get lost in triage? Where does it go? So that's why verbal handover can be useful for those that you're really worried about. And when someone really seems to be acknowledging what you're saying and understanding what you need from them, then that's really good.” [Participant 8; female; 35 years] |

| Clear referral pathways |

“…we need to provide them with really clear pathways [so they] know who to ring, how to easily get through to someone, who's gonna be on the other end…it can be very difficult for them trying to navigate our system and to know how to get… how to get through to the right department or the right specialist.” [Participant 2; female; 52 years] “…ohh I mean gosh, it will be wonderful once things are electronic, but right now it's literally just writing caps lock urgent referral on the fax. And then sometimes, for someone I’m really worried about, I will call the on call, but even then it's an open ended way to try and safety net. You're never sure whether it's worked or not…” [Participant 8; female; 35 years] |

| Timely knowledge and decision-making support |

“…there's a cardiologist who I listened to once, give a talk at the Primary Health Network and he said, ‘look, here's my mobile number’. He put it up on the screen, said ‘I'm more than happy for you guys to text me if you've got any questions’. And then I did. I texted him, and now when I have a patient that I wanna refer, I'll send him a WhatsApp and he always replies quickly. I've even sent him an ECG before and he was really great (…) With a website, I'm not quite sure if that would be useful because if it's got generic information about-…this is how to treat, say, bronchiolitis, it's probably likely something the GP already knows, it's just that this individual scenario needs to be tailored and we need advice on how to tailor it. So that's why I think talking about the actual case is much more useful than just-…it's not the clinical information we necessarily need, it's how to apply it.” [Participant 8; female; 35 years] “…a lot of referrals could be avoided if-…sometimes if you could just ask one or two questions of a specialist, you know (…) so-…and that's what makes the health system inefficient and that's what clogs it up and that's what makes managing patients so much harder and takes so much longer. You know, you’ve got to then-…end up referring them to a specialist and they don't get in to see the specialist for five or six weeks, when you could probably ask a couple of pointed questions to a specialist immediately.” [Participant 13; male; 47 years] |

| Adaptable funding model |

“…to have a flexible and adaptable funding model. (…) GPs can be on the phone for like, half an hour to find out what (…) do I do with this patient's long COVID (…) They can't really bill for that.” [Participant 4; male; 34 years] “…three assessments a day (…) Your standard GP just cannot do that. (…) So, you know, that talks to the funding structure and the model of general practice and primary care that's used in Australia at the moment. So it would be access to enough resources to deliver the clinical assessments, deliver the frequency of remote monitoring, being able to respond to what that monitoring and assessment is telling you…” [Participant 6; male; 47 years] “…we get paid for the encounter that we're with the patient. And so, it's sort of difficult to work out how you'd kind of incorporate that model of care… I think one of the problems we've got here is that we want to move into new innovative models of care that our funding model doesn't support.” [Participant 11; female; 50 years] |

| Awareness of existing support |

“…knowing what support is available to them to be able to keep their patients at home or in their place of residence and not have to send them to hospital. So, if they don't have an avenue by which they can get support, the default would be to send to ED because they're concerned about the patient (…)” [Participant 5; male; 38 years] “I even feel like within the…the hospital, people don't know what's there (…) even when I work in ED, some of the bosses say ‘yes, we do iron infusions in ambulatory care’ or ‘no, we don't do iron infusion’. Nobody knows. And it made me feel better realising that it’s not just because I'm in the community.” [Participant 8; female; 35 years] “Yeah, I think (…) some of the PHN resources are great and I just wonder about whether they're aligned with LHD advice lines and that sort of thing, because I mean ideally the LHD advice lines should be looking at the health pathways systems that the PHN's have set up and directing GPs into some of those where it's appropriate.” [Participant 11; female; 50 years] |

Motivation for GP advice lines

The need for the advice lines was reported to have arisen from the shift to the community-based model of care for COVID-19 patients: “we had been asked to see … how general practice could start to take over care of COVID patients … well, what about if we had a GP advice line, that was for the GP's to ring up and speak to a GP in the virtual hospital”—P03, HSM.

a. Benefits of GP advice lines.

Participants stated that GP advice lines were beneficial because they helped to minimise knowledge gaps and increase GP confidence in their skills and expertise in managing urgent care patients during the period of uncertainty in the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, a participant reported that, “OK, I don't actually have to know every bit of minutiae, the people at the end of this line, doctor to doctor, will tell me what I need to do or know”—P07, GP, while another stated that, “sometimes you're just not quite sure and so you can just ring … so it's that confidence that you're making the right decision by the patient.”—P09, GP.

Another benefit of GP advice lines was that they facilitated an easier referral process, as GPs could speak to a specialist and directly get an appointment for the patient in a manner that bypasses the emergency department: “So, it allows them to get seen in a timely manner in the public system, but without having to go through the emergency department.”—P09, GP (see Table 3 for additional quotes).

Table 3.

Illustrative quotes for theme “Motivation for GP advice lines”

| Motivation for GP advice lines |

“we got to a nexus where, you know, the…the pandemic was changing, the nature of care was changing, it was moving to obviously needing to be a community based model. The work that [health organisation] was doing on behalf of the district, was not going to be, nor should it be sustainable because it was becoming…endemic’s not the right word, but it was becoming endemic in the community. So there was a real shift towards primary care, which is where the clinician advice line came in.” [Participant 6; male; 47 years] “I think the principle of GP advice line is really to cover the skills and expertise gap in the community, which is actually, I think, really good, because if you look at a organisational challenge or, you know, whole industrial challenge in terms of workforce, you …you find we not only having shortage on staff, we're having shortage on skills and expertise.” [Participant 4; male; 34 years] |

| Benefits of GP advice lines |

Empowered GPs to manage patients in the community “…And I’ve certainly seen that, as I said, the GP’s that called, the next time they call for asthma, they're like, ‘I've done this and this and this, like what I did with the last patient’, and I think the more we get that exposure the lesser the calls will come, because we are actually empowering our GP’s to manage….” [Participant 14; male; 41 years] “We don’t necessarily take over, we actually empower the GP to say “look you can keep this child in your practice, you can see the child in two days’ time” [Participant 14; male; 41 years] “So, if the GP isn't sure about a COVID sort of thing, they will need to find someone to ask, right? So-…and then, because we are very familiar with that, and the policy changes every day, so it's good to… to have us supporting the GP's in the community and fill their expertise shortage or gap” [Participant 4; male; 34 years] |

|

Increased GP confidence “…so you can just ring and they can say ‘yes you're right’ or ‘no I would suggest this’ so it's that…that confidence that you're making the right decision by the patient…” [Participant 9; female; 59 years] “it just gave them the confidence, I think” [Participant 3; Female; 56 years] | |

|

Easier referral pathways “it means the patient gets seen in a timely manner, they don’t have to sit in the emergency department with a whole pile of coughing people…So, it allows them to get seen in a timely manner in the public system, but without having to go through the emergency department.” [Participant 9; female; 59 years] “[we] set up a GP advice line where GP’s could talk directly to a staff specialist about a COVID patient and that we would also have referral back to us available to GP’s. So if they were seeing a patient but risk factors changed, they really declined, the GP wasn't feeling confident anymore, they could refer the patient back under our care. [Participant 2; Female; 52 years] |

Factors influencing the uptake and sustainability of GP advice lines

A. Facilitators of GP advice lines.

Various facilitators to the use of the GP advice lines were identified by the participants, with the availability of a specialist response the most frequently reported. Participants stated specialist doctors with a level of seniority, training and experience, and preferably those with general practice expertise, are in the best position to be the receivers of the call; as this enabled the uptake and continuous use of the advice lines. A participant stated, “if you're calling the cardiology line, you'd want a cardiology AT who's working … in the rapid access clinic…. you get the best outcomes and the best communication when you're working like for like, so doctor to doctor.”—P05, HSM.

Also, GP advice line models that were designed to provide real-time support via synchronous communication between GPs and specialist doctors were preferred to models with asynchronous communication: “it was a great way for the GP's to be able to talk immediately, not e-mail someone and hope they get a response…. so it was this instantaneous decision making”—P07, GP.

Using various promotion strategies to create awareness of the purpose of, and how to use the advice line, was another facilitator. Participants further highlighted the primary health networks (PHNs) were a good avenue for disseminating information but insufficient to reach all GPs: “a lot of GP's have their own organisations … and some of those will go, ‘no, we don't have anything to do with the PHN’”—P13, GP.

Other reported facilitators to the GP advice lines included: co-designing the service with GPs and the availability of funding support (see Table 4 for additional quotes).

Table 4.

Illustrative quotes for theme “Factors impacting the uptake and sustainability of GP advice lines”

| Barriers to the uptake of GP advice lines |

Limited hours of the service “We do have quite a few [GP practices] that run on Sundays, so there was no access on a Sunday, you know, is-… so I definitely think having longer hours would have been good, because I think that there are people, you know, people get sick on the weekends.” [Participant 3; Female; 54 years] “sometimes it's also if it's after hours, you know, that’s just the way it is, but yeah, I guess that’s a potential barrier.” [Participant 9; Female; 59 years] |

|

Lack of clarity of receiver’s role “…the only problems I've had are when I've rung the line and the person has no idea-…they can still answer my question because it was a clinical question, but not understanding what they're actually answering, what, you know, what their role is.” [Participant 9; Female; 59 years] “There needs to be a workforce, and to be truly blunt, at the moment, sometimes GP's are calling this line and having a great experience, sometimes they're calling someone who doesn't even know what the GP advice line is, they didn't even know it existed.” [Participant 5; Male; 38 years] “…if I was a GP it would irritate me if, you know, I want to speak to the paediatrician, but I have to go through three different people and everyone is saying, ‘Oh no, this is not me. You need to call this person and that person’. So, I'll get frustrated, and then lesson learned, I won't call anymore, and I'll just send them to ED. I think that’s human nature.” [Participant 14; Male; 41 years] | |

|

Manual data collection “…with the GP advice line, we've done a lot of the data collection manually on spreadsheets… it's… it's a bit clunky, doesn't make for easy reporting.” [Participant 2; Female; 52 years] “…so I set it up in REDCap (…) what we did was set up a standard questionnaire so when we received a call we would take the name of the GP that was calling, their contact details, their email if they provided it, and the reasons for their call, and I put in a number of drop downs so it would be quick and easy to fill in, (…) whether they were calling about covid, whether we’d given them advice and whether we had ended that conversation or referred the patient on to the hospital” [Participant 1; female; 60 years] | |

| Facilitators of GP advice lines |

Availability of specialist response “…responding to the need that's in front of you, regardless of what that need is and obviously that requires, you know, a degree of seniority and training and experience. You don't want…you don't want it to be the most junior member of the team that's picking up the phone.” [Participant 6; Male; 47 years] “…specialist clinical advice. So, I mentioned the medical specialists, but also the medical specialists having the specific, the condition specific experience and expertise. So, for example, COVID or respiratory conditions….acute-… sorry….urgent care conditions, that's really important.” [Participant 2; Female; 52 years] |

|

Real time support “…if I'm a GP and I speak like for like with someone in their rapid access clinic, I either get advice to support my patient in their home, or a referral into the-… their outpatient clinic the next day, to help that patient…that patient avoid ED. That is a big win in the GP's book. And that will support future engagement number one, hands down. That is the number one thing.” [Participant 5; Male; 38 years] “…if the GP's got the patient in front of them and they need to lift the phone, there needs to be someone answering the phone there and then to assist them with making sure they're making a good decision based on the services and information that's available.” [Participant 6; Male; 47 years] | |

|

Promotion strategies to create awareness “…when we set this up, we made sure that health-…I don't know if you're familiar with health pathways, but health pathways reflected what we were doing. It described the care, it described what was available, it described the contact points.” [Participant 6; Male; 47 years] “I think it also requires education of patients and also GP’s on how to use the lines, I don’t think we can assume they just know how to do it.” [Participant 10; Male; age unknown] | |

|

Co-design with GPs “…you've got to get GP's opinions and feedback when you're trying to set it up to make sure that you're setting up something that works for them.” [Participant 13; Male; 47 years] “I think having clear communications, like, we have gone and done site visits…to the centres and introduced our team, and having regular meetings with the managers of the practices, encouraging…and then we’ve established models of care” [Participant 14; Male; 41 years] “You've got to get GPs involved in setting them up, so you've got to (…) get GP's opinions and feedback when you're trying to set it up to make sure that you're setting up something that works for them. Because a lot of the time, that's what happens, general practice (…) [is] doing the bulk of the heavy lifting in the health sector and it's certainly the most effective part of what goes on in health, but it, sort of, sits back and does all this work and then everybody around it from federal and state bureaucrats and other (…) authorities and organisations—they're making decisions about how GPs go about doing their job without often talking to general practice itself and GPs-…so I think that's…that's really vital…” [Participant 13; male; 47 years] | |

|

Funding support “The PHN agreed to give us some funding. So, the way we were able to establish the advice line was through PHN funding in the first instance” [Participant 2; Female; 52 years] “The GP access line was originally funded by the PHN. So, it was actually a collaboration with the PHN who funded that position, but we've since taken the position over and funding it from within the virtual hospital for that reason, so that we can borrow the services.” [Participant 6; Male; 47 years] | |

| Strategies to sustain the use of GP advice lines in the long term |

Broadening the GP advice line service to other patient cohorts to support GPs “ So, I mean the advice line is great because we provide advice, but there's… there need to be a point that, you know, there's real difficulty in managing that patient including on COVID or any …any… any other condition, so that we need to actually get more involved to support the GP.” [Participant 4; male; 34 years] “…now we're looking to do more things, so you know, not only COVID, now with the GP advice line, but we're, you know-…influenza…” [Participant 7; Female; 62 years] |

|

Digitise advice lines “…because it allows all of those things in one, real-time, sharing of images, discussion of real-time information. So, I think having that visual component adds value and that ability to share information, patient information, adds value as well, so, yeah, that's how I could see it potentially looking.” Participant 5; Male; 38 years] “I think just making use of the technology that's there, that we really just don't make use of. As I said, you know, at the moment for that, sort of-…to get to-…get sort of that secondary care advice, you either-…you kind of need to get on the phone sometimes, you know, and that's often, probably not the most efficient way of…of doing it, you know, you get on a landline, it's particularly not very efficient. You gotta ring up the admitting officer at an emergency department, I mean, that's just, you know, it can be really difficult. So, making better use of, you know, our mobile phones and…and…and…and systems like Teams where you can interact, you know, visually, audio, upload information, upload images, upload videos, all sorts of things. We need to …be making use of these sort of things rather than just getting on traditional telephone and having to call up another landline.” [Participant 13; Male, 47 years] | |

|

Evaluate impact on health outcomes “So, if we go back to the principle that I think we were trying to focus on, the outcome. So, whether we have actually prevented the hospital presentation or hospital admission, whether we were able to, you know, move that care from the traditional hospital to the community by supporting the GP and then obviously the experience for providing and receiving care…” [Participant 4; male; 34 years] “I would say it would be feedback-based and probably also assessment of the numbers. So, feedback from all parties involved including the consumers, patients. Looking at the types and numbers of referrals, whether the stated aims of-…well, with our service, one of our key priorities is around ED avoidance. So, whether that's met and whether the patients’ needs have been met through the alternative pathways.” [Participant 12; Female; 37 years] | |

|

Involve consumers to gain their trust “…if the GP's using the advice line with the person or carer there, it should be a routine part of that conversation to involve the person or carer in the conversation. So it…it really should be a three way conversation, not a two way conversation.” [Participant 11; Female; 50 years] ““I’m happy for my GP to use GP advice lines. I mean the only thing I’d want to be assured of was actually that advice line went through to a hospital and another clinical professional who was qualified to advise on whatever it was” [Participant 16; Female; 68 years] “I think the transparency should be there, as family…parents, I don't know about adults, but parents with a child would appreciate that the GP is taking the effort and time to speak to a paediatric service there and then.” [Participant 14; Male; 41 years] |

b. Barriers to the uptake of GP advice lines.

Participants noted some barriers to the uptake of GP advice lines. A key barrier was the limited hours of the service, which prevented GPs who work after hours and on weekends from using the service. For example, a participant stated that “but often I find I have to wait until 9:00 or 9:30 to call someone-…call an advice line. Most GP practises open at 8:00 or above.”- P08, GP while another said, “I definitely think having longer hours would have been good… people get sick on the weekends”—P03, HSM.

Another barrier that was raised was the lack of clarity on the role of the clinician on the receiver’s end of the call. Participants reported occasions where the GPs rang clinicians through the advice line but the receiver of the call was not fully aware of their role and unable to support GPs as needed to manage an urgent care patient in the community: “the only problems I've had are when I've rung the line and the person has no idea… what their role is.”—P09, GP.

Manual data collection was also noted as barrier to the use of the advice line, which makes it challenging to report on how the line is being used by GPs: “so with the GP advice line, we've done a lot of the data collection manually on spreadsheets… it's a bit clunky, doesn't make for easy reporting.”—P02, HSM (see Table 4 for additional quotations to support these themes).

c. Strategies to ensure the sustainability of GP advice lines.

To support the sustainability of the advice lines, participants emphasised the need to broaden the service from primarily focusing on COVID-19 to focus on other patient cohorts so that benefits can be felt by patients with a range of conditions in the broader community e.g. influenza. It was however noted that broadening the advice line service should be done cautiously: “we need to start small. We need to be specific to start with because if you open the door to every single condition, we'll just get overwhelmed easily. And [this] …is safer option as well …So, we're prepared to support and then gradually open the gate to support the wider community.”—P04, HSM.

Further digitising the advice line technologies, by providing additional electronic functionalities, was another strategy participants reported would be helpful in sustaining the advice lines. For example, a participant stated that, “if you look at the GP advice line in its current form, it's a phone service, … if there was… like a chat service that would allow,… [communication] via chat, …to discuss patient scenarios, secure sending of images…. real-time, sharing of images.”—P05, HSM.

Other participants indicated that the use of artificial intelligence (AI) driven clinical decision support tools, including the use of large language models such as Chat-GPT may have a role to play in complementing the advice lines. They noted that AI-driven tools could be integrated into practice software, and Health Pathways, such that a tiered level of support can be provided on low-risk concerns, while high risk issues would be handled through doctor-to-doctor conversations. For example, a participant stated that, “the advice line might be receiving calls that in the future could be handled through CHAT GPT AI type things…so the level of escalation may actually be for those that are a lot more serious, where you actually require a consultation with a fellow GP…”—P10, HSM.

Participants also reported that evaluation was imperative for the sustainability of the advice lines. Evaluating the advice lines was described to be critical to showcasing its benefits to enable ongoing support from funders: “so I thought, well if we can validate that this was a great utilisation of money, it connected GP’s to tertiary hospital, ensured that the patient had continuity of care as well, and if they were discharged from hospital.. by connecting them with their GP, then we would get ongoing funding.”—P01, HSM.

As part of an evaluation, participants stated that it was imperative to measure patient outcomes such as hospital presentation, and hospital admissions; clinician outcomes such as frequency of calls from a specific GP, reasons for the call, clinician experience and satisfaction; and health economic outcomes such as cost–benefit analysis: “I would love to look at some sort of evaluations that look at potential ED avoidance. Did this help avoid ED? You could then equate that to, you know, cost savings of ED admissions and bed stay and things like that as well” P05, HSM.

Consumer involvement was also highlighted as important in the ongoing use and expansion of the capabilities of GP advice lines. Participants indicated that the advice lines could evolve from a 2-way conversation to one that involves the GP, the specialist doctor and the patient. However, this was dependent on an alignment with the patient’s preference, and the patient’s level of health literacy. Nonetheless, it was noted that the current model of advice lines would benefit from trust between the GP and the patient, patient’s understanding and awareness of the usefulness of the advice lines and patient consent. A participant stated: “the only thing I’d want to be assured of was actually that advice line went through to a hospital and another clinical professional who was qualified to advise on whatever it was.” – P16, consumer. See Table 4 for more quotes.

Discussion

Our study assessed stakeholder perspectives on the support and resources GPs need for the management of urgent care patients in the community in coordination with hospital services, and identified the motivation for GP advice lines, as well as the barriers to adoption, facilitators and strategies to support the sustainability of GP advice lines. Our study revealed that better communication of hospital services with GPs is needed to facilitate continuity of care between primary and tertiary care services. Timely decision-support and advice, clear referral pathways, an adaptable funding model, and greater awareness of existing support were also identified as key aspects required to support GPs in managing urgent care patients. We also identified factors influencing the adoption of GP advice lines, including real-time availability of specialist advice (facilitator), limited hours of the advice line service (barrier) and need for robust evaluation of the advice line service (sustainability strategy).

Continuity and coordination of care are key elements of high-quality primary care [23–25] and our study revealed that improving these elements is seen as a key enabler for the management of urgent care patients in the community. Continuity of care can be defined as the degree to which patients experience the delivery of services by different providers in a coherent, logical, and timely fashion, based on three main types of continuity: informational, management, and relational [25]. Gaps in communication and information sharing between hospital and primary care clinicians were commonly highlighted as the main barrier to continuity and coordination of care. These deficits are well described in the literature, with direct communication between hospital doctors and GPs known to occur infrequently and impacting patient safety and health outcomes [15, 23, 24, 26–29]. Recently, an international cross-sectional study showed that a higher frequency of informal interactions between GPs and hospital doctors (for example, through the use of telephone calls to ask for advice) was associated with higher frequency of referral letters, discharge summaries, and feedback communications [30].

The ability for the GP to connect directly with the hospital specialist, rather than using a routing system, call-back procedure, or other asynchronous approaches, [31] has been reported as the most common format for telephone consultation services between doctors [32], and seems particularly relevant in the context of urgent care. Nevertheless, participants in our study also indicated the potential for other technologies to support GPs in managing urgent care patients. Other technologies such web-based platforms can facilitate sharing of medical record information [33–36], while also enabling doctors to communicate synchronously via audio or video call. Recently, the use of artificial intelligence-driven clinical decision support tools has become more common [37], with participants in our study also mentioning the potential of large language models and conversational artificial intelligence to support GPs regarding urgent care, with research needed on the feasibility, acceptability and safety of such AI-driven approaches [38, 39]. Importantly, trusting the source of the advice was highlighted as key in our study and others [40], which is even more important in the context of AI-driven support.

Limitations

Our recruitment strategy was based on a purposive sampling technique and a passive snowballing approach to increase the diversity of our sample, but we acknowledge that our sample is limited to Sydney, NSW and our findings may not be generalisable to the broader population. However, it is important to bear in mind that generalisability is not a goal of qualitative research. Rather, its objectives are to enable an in-depth exploration of the topic of interest, which we achieved in this study. Also, none of our interviews were conducted in-person and nuances generated from non-verbal cues could have been missed, particularly in the singular phone interview that was conducted. Nonetheless, online interviews provided easier logistical access to participants. Future research should focus on aspects that were outside of the scope of this study, such as evaluating process measures, as well as quality and safety of implemented GP advice lines.

Conclusion and recommendations

This qualitative study of stakeholder perspectives identified better coordination and continuity of care as key enablers for the management of urgent care patients in the community. GP advice lines were seen as supporting coordination and continuity of care by enabling GPs to remain the locus of patient care while leveraging hospital specialists’ expertise. With increasing technology sophistication, there remain opportunities to further digitise and optimise advice lines, whilst ensuring better integration within and across primary and tertiary care services. Based on the findings of this study, we provide recommendations for managing urgent care patients in the community.

1. Tertiary care services should provide care information to GPs about their patients, clear referral pathways and timely decision-making support.

2. GP advice lines require careful co-design and implementation, together with GPs, to ensure they are aligned with GP workflows. GP advice lines can be digitised to provide access to discharge information, and to support innovative models of care.

3. PHNs and health service organisations can leverage the use of technologies to provide a tiered level of support, such as conversational AI-driven tools for low-risk issues, with high-risk issues being handled through doctor-to-doctor conversations.

4. Researchers have a role to play in sustaining GP advice lines by conducting robust evaluation to determine its impact on patient, clinician, health service experience and outcomes.

5. Health service organisations can provide better awareness of existing support (e.g. advice lines) to general practices, for example leveraging PHNs to communicate with affiliated GPs. In addition, local media campaigns can be implemented to inform the general public (and harder-to-reach GPs) about existing services aimed at strengthening the communication between hospitals and primary care.

6. The government and policymakers should consider providing an adaptable funding model to support general practice services in caring for urgent care patients in the community.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

None.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualisation: LL, TS, CKC, MM, MS, SN, MB; Data collection and analysis: LL, DK, AB; Interpretation of findings: AB, MM, DK, NN, KS, MS, AJ, FR, OH, SN, JS, MB, CKC, TS, LL; First draft: AB, LL; Revision of manuscript: AB, MM, DK, NN, KS, MS, AJ, FR, OH, SN, JS, MB, CKC, TS, LL.

Funding

This work was supported by a Sydney Health Partners Round 1 Clinical Academic Groups Funding Opportunity.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to ethics restrictions but may be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request pending ethics approval.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was received from Western Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee (2022/ETH01690), in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research. All participants provided informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Tim Shaw and Liliana Laranjo are co-senior authors.

References

- 1.Lowthian JA, Curtis AJ, Jolley DJ, Stoelwinder JU, McNeil JJ, Cameron PA. Demand at the emergency department front door: 10-year trends in presentations. Med J Aust. 2012;196(2):128–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCaffrey N, Scollo M, Dean E, White SL. What is the likely impact on surgical site infections in Australian hospitals if smoking rates are reduced? A cost analysis. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(8):e0256424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baier N, Geissler A, Bech M, Bernstein D, Cowling TE, Jackson T, et al. Emergency and urgent care systems in Australia, Denmark, England, France, Germany and the Netherlands-Analyzing organization, payment and reforms. Health Policy. 2019;123(1):1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adie JW, Graham W, Wallis M. Factors associated with choice of health service delivery for after-hours, urgent, non-life-threatening conditions: a patient survey. Aust J Prim Health. 2022;28(2):137–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoot NR, Aronsky D. Systematic review of emergency department crowding: causes, effects, and solutions. Ann emerg med. 2008;52(2):126–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li E, Tsopra R, Jimenez G, Serafini A, Gusso G, Lingner H, et al. General practitioners’ perceptions of using virtual primary care during the COVID-19 pandemic: An international cross-sectional survey study. PLOS Digit Health. 2022;1(5):e0000029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sitammagari K, Murphy S, Kowalkowski M, Chou S-H, Sullivan M, Taylor S, et al. Insights from rapid deployment of a “virtual hospital” as standard care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(2):192–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pandit JA, Pawelek JB, Leff B, Topol EJ. The hospital at home in the USA: current status and future prospects. NPJ Digit Med. 2024;7(1):48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson M, Mazowita G, Ignaszewski A, Levin A, Barber C, Thompson D, et al. Family physician access to specialist advice by telephone: Reduction in unnecessary specialist consultations and emergency department visits. Can Fam Physician. 2016;62(11):e668–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wegner SE, Humble CG, Feaganes J, Stiles AD. Estimated savings from paid telephone consultations between subspecialists and primary care physicians. Pediatrics. 2008;122(6):e1136–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salles N, Floccia M, Videau MN, Diallo L, Guérin D, Valentin V, et al. Avoiding emergency department admissions using telephonic consultations between general practitioners and hospital geriatricians. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(4):782–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bal G, Sellier E, Gennai S, Caillis M, François P, Pavese P. Infectious disease specialist telephone consultations requested by general practitioners. Scand J Infect Dis. 2011;43(11–12):912–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tian PGJ, Eurich D, Seikaly H, Boisvert D, Montpetit J, Harris J. Telephone consultations with otolaryngology - head and neck surgery reduced emergency visits and specialty consultations in northern Alberta. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;49(1):39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zanaboni P, Scalvini S, Bernocchi P, Borghi G, Tridico C, Masella C. Teleconsultation service to improve healthcare in rural areas: acceptance, organizational impact and appropriateness. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9(1):238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pantilat SZ, Lindenauer PK, Katz PP, Wachter RM. Primary care physician attitudes regarding communication with hospitalists. Am J Med. 2001;111(9):15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sankaranarayanan A, Allanson K, Arya DK. What do general practitioners consider support? Findings from a local pilot initiative. Aust J Prim Health. 2010;16(1):87–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trankle SA, Usherwood T, Abbott P, Roberts M, Crampton M, Girgis CM, et al. Integrating health care in Australia: a qualitative evaluation. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shaw M, Anderson T, Sinclair T, Hutchings O, Dearing C, Raffan F, et al. rpavirtual: Key lessons in healthcare organisational resilience in the time of COVID-19. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2022;37(3):1229–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hutchings OR, Dearing C, Jagers D, Shaw MJ, Raffan F, Jones A, et al. Virtual health care for community management of patients with COVID-19 in Australia: observational cohort study. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(3):e21064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hennink MM, Kaiser BN, Marconi VC. Code saturation versus meaning saturation: how many interviews are enough? Qual Health Res. 2017;27(4):591–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Braun V, Clarke V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative research in sport, exercise and health. 2019;11(4):589–97. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dale SB, Ghosh A, Peikes DN, Day TJ, Yoon FB, Taylor EF, et al. Two-year costs and quality in the comprehensive primary care initiative. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(24):2345–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83(3):457–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haggerty JL, Reid RJ, Freeman GK, Starfield BH, Adair CE, McKendry R. Continuity of care: a multidisciplinary review. BMJ. 2003;327(7425):1219–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moore C, Wisnivesky J, Williams S, McGinn T. Medical errors related to discontinuity of care from an inpatient to an outpatient setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(8):646–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dinsdale E, Hannigan A, O’Connor R, O’Doherty J, Glynn L, Casey M, et al. Communication between primary and secondary care: deficits and danger. Fam Pract. 2020;37(1):63–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Malley AS, Reschovsky JD. Referral and consultation communication between primary care and specialist physicians: finding common ground. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(1):56–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scaioli G, Schäfer WL, Boerma WG, Spreeuwenberg PM, Schellevis FG, Groenewegen PP. Communication between general practitioners and medical specialists in the referral process: a cross-sectional survey in 34 countries. BMC family practice. 2020;21(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Radnaeva I, Muthusami A, Ward S. NHS advice and guidance – improving outpatient flow and patient care in general surgery. The Surgeon. 2023;21(5):e258–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tian PGJ, Harris JR, Seikaly H, Chambers T, Alvarado S, Eurich D. Characteristics and Outcomes of Physician-to-Physician Telephone Consultation Programs: Environmental Scan. JMIR Form Res. 2021;5(2):e17672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scherpbier-de Haan ND, van Gelder VA, Van Weel C, Vervoort GM, Wetzels JF, de Grauw WJ. Initial implementation of a web-based consultation process for patients with chronic kidney disease. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(2):151–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Gelder VA, Scherpbier-de Haan ND, van Berkel S, Akkermans RP, de Grauw IS, Adang EM, et al. Web-based consultation between general practitioners and nephrologists: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Fam Pract. 2017;34(4):430–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liddy C, Drosinis P, Keely E. Electronic consultation systems: worldwide prevalence and their impact on patient care-a systematic review. Fam Pract. 2016;33(3):274–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Keely E, Liddy C, Afkham A. Utilization, benefits, and impact of an e-consultation service across diverse specialties and primary care providers. Telemedicine and e-Health. 2013;19(10):733–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee P, Bubeck S, Petro J. Benefits, limits, and risks of GPT-4 as an AI chatbot for medicine. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(13):1233–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thirunavukarasu AJ, Ting DSJ, Elangovan K, Gutierrez L, Tan TF, Ting DSW. Large language models in medicine. Nat Med. 2023;29(8):1930–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meskó B, Topol EJ. The imperative for regulatory oversight of large language models (or generative AI) in healthcare. NPJ digital medicine. 2023;6(1):120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hollins J, Veitch C, Hays R. Interpractitioner communication: telephone consultations between rural general practitioners and specialists. Aust J Rural Health. 2000;8(4):227–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to ethics restrictions but may be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request pending ethics approval.