Abstract

Open reading frame 1 (ORF1) of potexviruses encodes a viral replicase comprising three functional domains: a capping enzyme at the N terminus, a putative helicase in the middle, and a polymerase at the C terminus. To verify the enzymatic activities associated with the putative helicase domain, the corresponding cDNA fragment from bamboo mosaic virus (BaMV) was cloned into vector pET32 and the protein was expressed in Escherichia coli and purified by metal affinity chromatography. An activity assay confirmed that the putative helicase domain has nucleoside triphosphatase activity. We found that it also possesses an RNA 5′-triphosphatase activity that specifically removes the γ phosphate from the 5′ end of RNA. Both enzymatic activities were abolished by the mutation of the nucleoside triphosphate-binding motif (GKS), suggesting that they have a common catalytic site. A typical m7GpppG cap structure was formed at the 5′ end of the RNA substrate when the substrate was treated sequentially with the putative helicase domain and the N-terminal capping enzyme, indicating that the putative helicase domain is truly involved in the process of cap formation by exhibiting its RNA 5′-triphosphatase activity.

Bamboo mosaic virus (BaMV) is a member of the potexvirus group, which belongs to the alphavirus-like superfamily. The ∼6.4-kb positive-strand RNA genome of BaMV consists of a 94-nucleotide 5′-untranslated region, ORF1 (4,098 nucleotides), a triple gene block (ORF2 to ORF4), coat protein-coding region (ORF5), a 142-nucleotide 3′-untranslated region, and a poly(A) tail (20). ORF1 of BaMV encodes a 155-kDa polypeptide (replicase) whose amino acid sequence reveals three functional domains: an N-terminal Sindbis virus-like methyltransferase, a central putative RNA helicase, and a C-terminal RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) (9, 16, 24). Recently, the activities of RdRp (18) and RNA capping (guanylyltransferase and methyltransferase) (19) in the C and N termini, respectively, of the BaMV replicase were verified. The central region of the 155-kDa replicase contains several conserved motifs belonging to superfamily 1 (SF1) of RNA helicases (14). This middle region (designated here the helicase-like domain) has thus been hypothesized to be an RNA helicase that assists RdRp in the RNA replication process by unwinding the duplex RNA structure. Besides the central helicase-like domain encoded by ORF1, the 28-kDa movement protein encoded by ORF2 also harbors nucleoside triphosphate (NTP)-binding helicase motifs. Although the overall homology is no more than 20%, the two BaMV proteins have similar sequences in regions containing putative motifs I, II, and VI of SF1 helicases. Since the products of triple gene block are indispensable for the movement of potexviruses through the plasmodesmata between host cells (4, 5), it is believed that the 28-kDa protein helps the viral genome move by its as yet unidentified helicase activity. Recently, the nucleoside triphosphatase (NTPase) and RNA-binding activities on the 28-kDa protein were corroborated (20a, 28). Among the alphavirus-like supergroup, the association of NTPase activity with NTP-binding helicase motif-containing proteins has also been established in several cases such as the nsP2 protein of Semliki Forest virus (23), the nonstructural 206-kDa polyprotein of turnip yellow mosaic tymovirus (13), and a fragment of the nonstructural polyprotein of rubella virus (10). Some RNA helicases such as the nsP2 protein of Semliki Forest virus and the λ1 protein of reovirus also possess RNA 5′-triphosphatase activity (7, 27), suggesting that these two animal viral proteins are involved not only in RNA replication but also in the formation of the 5′ cap structure of newly synthesized viral RNAs.

Eukaryotic mRNA possesses a blocked 5′ end, m7G(5′)pppN-, known as the cap structure, which is required for translation and mRNA stability. In general, capping occurs on nascent RNA transcripts inside the nucleus and is catalyzed by three consecutive enzymatic activities (22, 25). First, the 5′-triphosphate group of the nascent mRNA is hydrolyzed by RNA 5′-triphosphatase; the 5′-diphosphate terminus is then capped with GMP by mRNA guanylyltransferase; finally the G(5′)pppN- is methylated by RNA (guanine-7)-methyltransferase using S-adenosylmethionine (AdoMet) as the methyl group donor. Potexvirus multiplies in the cytoplasm of the infected cells; thus it is presumed that the virus possesses its own capping machinery. In a previous study, we demonstrated that the N-terminal 442 amino acids of the 155-kDa protein exhibit a distinct AdoMet-dependent guanylyltransferase activity (19). In an attempt to search for all the inherent activities associated with the 155-kDa replicase and find out whether BaMV has RNA 5′-triphosphatase activity, we set out to characterize the properties of the helicase-like domain and the 28-kDa movement protein in this study. Results indicate that the helicase-like domain of BaMV replicase possesses both NTPase and RNA 5′-triphosphatase activities and that the latter activity is indeed involved in the formation of the cap structure by collaborating with the RNA-capping activity residing in the N-terminal domain of the 155-kDa protein.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids.

The corresponding cDNA fragment of the helicase-like domain was amplified by PCR using primers 5′-AGCGAGGAGCGGAAGTGCC and 5′-TTCGGAAAGCTTCAGTCAGTGTTCCTTTGTAAGGTTGA in a 50-μl reaction mixture containing 1 ng of pBL (carrying the full-length cDNA of BaMV), 0.32 μM (each) primer, 0.2 mM (each) deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP), and 2.5 U of Pfu polymerase. The amplified DNA fragment (1,137 bp) was digested with HindIII and then inserted into HindIII-EcoRV-treated plasmid pET32 (Novagen) to become helicase-like domain expression vector pHWT. The mutation of the GKS motif to GAA was performed by a PCR-based mutagenesis in which a pair of divergent 5′-phosphorylated primers, 5′-GCCGCAAGAGCCCCTGCAAGAATACATGAGG and 5′-ACCACTGCCGCCCGCGCCATGTAT, was used in a 50-μl PCR mixture that contained 50 ng of pHWT, 0.32 μM (each) primer, 0.2 mM (each) dNTP, and 2.5 U of Pfu polymerase. The sequences in italics represent the mutagenic codons. The amplified blunt-ended ∼7.0-kb DNA fragment was then self-ligated and designated pHAA.

A pair of divergent 5′-phosphorylated primers (5′-TCAGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGTTCGGTAGTTGCTGCGTCTGT and 5′-GCTCTAGAGGGCCGCATCATGTAA) was used to add a hexahistidine-coding sequence to the 3′ end of the coding sequence of the BaMV capping enzyme domain in a PCR-based insertion mutagenesis. The inserted sequence is underlined, and it is complementary to the coding sequence of the histidine tag. The 50-μl PCR mixture contained 0.32 μM (each) primer, 50 ng of pYEB3 (18), 0.2 mM (each) dNTP, and 2.5 U of Pfu polymerase. The amplified blunt-ended DNA fragment was then self-ligated and designated pYEB3H. The mutations created by PCR were verified by nucleotide sequencing using an Amplicycle sequencing kit (Perkin-Elmer).

Protein expression and purification.

Escherichia coli Novablue cells (Novagen) harboring the desired plasmids were grown in Luria-Bertani broth, and the helicase-like domain was produced by the induction of IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside). Cells were then harvested by centrifugation, suspended in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 100 mM KCl, 0.1% Brij-35, 10% glycerol, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], and protease inhibitor cocktail [Boehringer Mannheim]), and broken by ultrasonication. The majority of the helicase-like domain was pelleted as inclusion bodies, solubilized in 8 M urea-containing Tris buffer (pH 7.5, 50 mM), and immediately refolded in an excess of lysis buffer. The refolded protein was then purified by Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) (Qiagen) chromatography according to the instructions of the manufacturer. For determining the metal dependence of enzymatic activities, the purified helicase-like domain was dialyzed sequentially against a 1,000-fold dialysis buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 100 mM KCl, 5% glycerol, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], and 1 mM PMSF) with or without EDTA (5 mM). The full-length 155-kDa protein and the C-terminal RdRp domain were expressed as previously described (18) and purified by procedures described above. The purified 28-kDa movement protein of BaMV was a gift from Ban-Yang Chang (28).

The histidine tag-fused RNA-capping enzyme of BaMV was produced by Saccharomyces cerevisiae containing pYEB3H, and it was collected in the membrane fraction as described previously (19). The membrane fraction was then solubilized in the extraction buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 100 mM KCl, 5 mM DTT, 4 mM PMSF, and 0.3% Sarkosyl NL30). The detergent-solubilized protein was then purified with Ni2+-NTA resin (Qiagen) and subsequently dialyzed with dialysis buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 100 mM KCl, 5% glycerol, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF, and 0.3% Sarkosyl NL30) to remove excessive imidazole.

Preparation of RNA substrates.

A 200-nucleotide 5′-terminal fragment of the plus-strand RNA of BaMV was produced by an in vitro transcription reaction as described previously (18). For the production of 5′-32P-radiolabeled RNA, 20 μCi of either [α-32P]GTP or [γ-32P]GTP (Amersham; 5,000 Ci/mmol) was included in the in vitro transcription reaction. The reaction products were then treated with DNase I, extracted with phenol-chloroform (1:1), and purified by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) in 8% gels containing 7 M urea.

Activity assay.

Unless otherwise stated, the standard NTPase reaction was performed at 37°C for 30 min in a 10-μl solution containing 50 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM DTT, 200 μM NTP, 5 μCi of [α-32P]NTP (Amersham; 5,000 Ci/mmol), 40 U of RNase inhibitor (HPR I; Takara), and 30 ng of the purified enzymes. The reaction was stopped by adding 5 mM EDTA. Aliquots of the reaction products were spotted on a polyethyleneimine (PEI)-cellulose thin-layer chromatography (TLC) plate (Merck), developed with 0.5 M LiCl–0.5 M formic acid, and visualized by autoradiography. Nucleotide markers such as GTP, GDP, GMP, ATP, ADP, CTP, CDP, UTP, and UDP were run along with the reaction products and visualized under UV at 254 nm. To determine the kinetic constants of ATPase, the activity was measured by an enzyme-coupled assay (26) in which the reaction was performed at 37°C in a 1-ml solution containing 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM DTT, 50 to 800 μM ATP, 2 mM phosphoenolpyruvate, 0.2 mM NADH, 12 U of pyruvate kinase, 12 U of lactic dehydrogenase, and 1 to 3 μg of the helicase-like domain. The rate of ATP hydrolysis, equivalent to the rate of consumption of NADH, was calculated from the rate of decline of the optical density at 340 nm. Kinetic constants Km and Vmax, were determined from Lineweaver-Burk and Eadie-Hofstee plots.

The standard RNA 5′-triphosphatase activity reaction was performed at 37°C for 30 min in a 10-μl volume that contained 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM DTT, 2 μg (∼3 μM) of 5′-32P-labeled RNA, 40 U of RNase inhibitor, and 30 ng of the purified enzymes. The reaction was stopped by phenol-chloroform extraction, and aliquots from reaction mixtures were spotted onto PEI-cellulose TLC plates, developed with 0.5 M LiCl–0.5 M formic acid, and visualized by autoradiography. To determine the nature of the 5′ termini of RNA molecules, the 5′-α-32P-RNA was first subjected to the standard RNA triphosphatase reaction as described above, extracted with phenol-chloroform, and precipitated with ethanol. The recovered RNA was then digested with nuclease P1 (10 μg/μl) at 37°C, and the products were analyzed using TLC as described above. To determine the reaction rate of RNA 5′-triphosphatase, 10 ng of the helicase-like domain was added to buffer containing 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM DTT, 40 U of RNase inhibitor, and 50 μM RNA in a final volume of 20 μl. After incubation for various times at 37°C, the reactions were terminated by the addition of 20 μl of perchloric acid (0.6 M), and the concentrations of Pi in the supernatant were determined by a malachite green colorimetric assay (17). It was found that the rate of liberation of Pi is constant within the first 4-min incubation.

The in vitro RNA-capping assay mixture contained 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 4 mM MgCl2, 5 mM DTT, 40 U of RNase inhibitor, 20 μCi of [α-32P]GTP, 1.2% n-octyl-β-d-glucopyranoside, 800 μM AdoMet, 5 μg of RNA, and 200 ng of the purified capping enzyme domain in a final volume of 20 μl. Following incubation, the samples were extracted with phenol-chloroform, and the RNA substrate was analyzed by electrophoresis on 6% polyacrylamide gels containing 8 M urea and autoradiography.

Resolving the cap structure by TLC.

The 32P-labeled RNA product of the in vitro capping assay was first purified by PAGE and ethanol precipitation. The recovered RNA (100 ng) was then incubated with 5 μg of either nuclease P1 (in 25 mM sodium acetate [pH 6.2]–2.5 mM MgCl2) or RNase T1 (in 10 mM Tris [pH 8.0]–1 mM EDTA) in a final volume of 10 μl for 1 h at 37°C. Following phenol-chloroform extraction, portions of the samples, along with unlabeled marker m7GpppG, were spotted onto a PEI-cellulose TLC plate, developed with 1.2 M LiCl, and visualized by autoradiography. The marker was detected under UV at 254 nm.

RESULTS

Protein expression and purification.

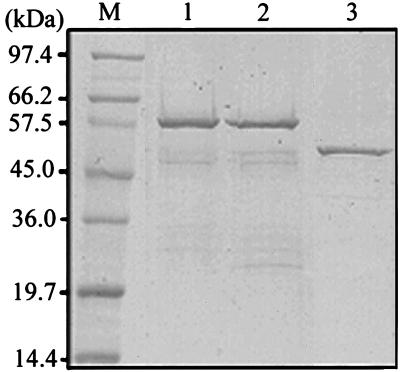

The central region of the 155-kDa replicase is a helicase-like domain owing to the presence of motifs I (640GSGKS644), II (700IMDD703), III (729GDPRQ733), V (784GQKTRISV791), and VI (852AFSR855) of SF1 helicases (the numbers indicate amino acid positions). To explore the enzymatic activities associated with the helicase-like domain, the corresponding cDNA fragment was inserted into pET32 and the target protein was expressed in E. coli with thioredoxin, a His tag, and an S tag fused at its N terminus. While most of the recombinant protein was insoluble, a small fraction remained in the supernatant after 18,000 × g centrifugation. Purification efforts were initially focused on the soluble fraction. Practically, the soluble helicase-like domain could be purified by metal affinity chromatography; however, the homogeneity could not be appreciated owing to the degradation of the protein that occurred inside E. coli cells. The efforts were then devoted to purifying the protein in the insoluble fraction. The insoluble protein was first dissolved in urea-containing buffer and dialyzed immediately against a large quantity of buffer to allow the protein to refold. Metal affinity chromatography was subsequently employed to purify the helicase-like domain (Fig. 1, lanes 1 and 2). The purified protein remained soluble after a 30-min centrifugation at 18,000 × g, suggesting that the refolded protein did not aggregate. Western blotting analysis suggested that most of the minor proteins present in the purified sample are degraded products of the helicase-like domain (data not shown). The proteins purified from both the soluble and insoluble fractions had the same enzymatic activities, which are described below, suggesting that the refolded proteins should have the correct conformations.

FIG. 1.

Purification of the E. coli-expressed helicase-like domain and the S. cerevisiae-expressed capping enzyme domain of BaMV replicase. The helicase-like domain was purified from the insoluble fraction of E. coli cell extracts by steps of urea denaturing, renaturing, and metal affinity chromatography. Lane 1, wild-type helicase-like domain; lane 2, motif I mutant (GKS→GAA); lane 3, C-terminal hexahistidine-fused capping enzyme domain purified by steps of membrane fractionation, detergent solubilization, and metal affinity chromatography. The purified proteins were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-PAGE (10% polyacrylamide) and visualized by Coomassie blue staining. The sizes of marker proteins (lane M) are indicated at the left.

In a previous study, we demonstrated that the N-terminal 442 amino acids of the 155-kDa protein constitute a capping enzyme that forms a covalent linkage to m7GMP, a characteristic of capping activity, when it was incubated with GTP and AdoMet (19). To assure the RNA-capping function of the N-terminal domain, it is important to demonstrate that the protein-linked guanylate moiety could be further transferred to the 5′ ends of RNA substrates. A pure preparation of the N-terminal domain is necessary for such an in vitro RNA capping assay to avoid the interference of RNase contamination. To facilitate the enzyme purification, a hexahistidine tag was fused at the C terminus of the BaMV capping enzyme in this study. Several detergents were tested for their ability to solubilize the capping enzyme from the yeast membrane fraction. Among them, Sarkosyl NL30 had the best result. The Sarkosyl-solubilized protein was then purified by metal affinity chromatography (Fig. 1, lane 3).

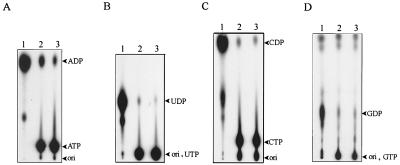

NTPase activity.

The NTPase activity was measured initially by the liberation of [α-32P]NDP from the hydrolysis of [α-32P]NTP. TLC analysis of the reaction products revealed that the helicase-like domain could catalyze the hydrolysis of all four NTPs (ATP, GTP, UTP, and CTP) to nucleoside diphosphates and phosphate (Fig. 2, lane 1). Mutation of GKS (motif I) to GAA reduced this activity dramatically (Fig. 2, lane 2). To characterize the NTPase activity in detail, the ATPase activity was measured kinetically based on the enzyme-coupled assay described in Materials and Methods. From four independent sets of data, the Km and kcat values of ATPase were determined to be 260 ± 30 μM and 13 ± 3 s−1, respectively. Although NTPase activity is a prerequisite for RNA helicase activity, the evidence for helicase activity has not been determined yet.

FIG. 2.

NTPase activity of the helicase-like domain analyzed by TLC (A) ATPase; (B) UTPase; (C) CTPase; (D) GTPase. [α-32P]NTP was incubated with various enzyme preparations (lanes 1, wild-type helicase-like domain; lanes 2, motif I mutant (GKS→GAA); lanes 3, blank), and the reaction products were analyzed by TLC as described in Materials and Methods. Standard nucleotides (arrowheads) were run along with the radiolabeled samples in a same TLC sheet, visualized under UV at 254 nm.

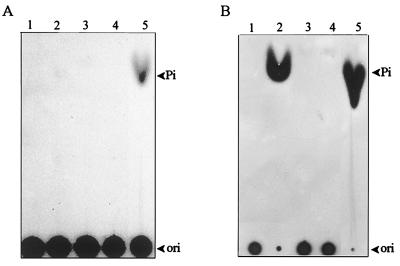

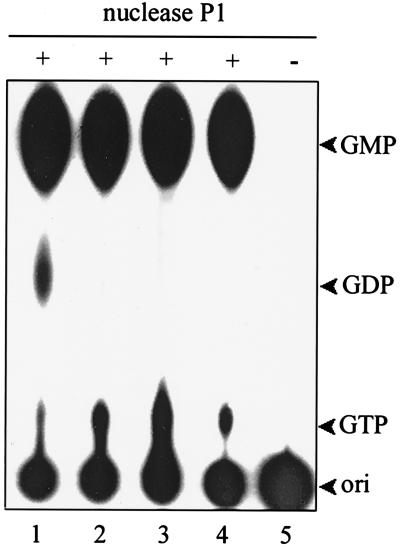

RNA 5′-triphosphatase activity.

The lack of selectivity on NTPs for NTPase activity prompted us to ask whether the BaMV helicase-like domain could also take the 5′-triphosphate of an RNA molecule as a substrate. To address the question, 5′-γ-32P-RNA and 5′-α-32P-RNA were prepared by including [γ-32P]GTP and [α-32P]GTP, respectively, in the in vitro transcription mixture. Each 5′-radiolabeled RNA was incubated individually with the helicase-like domain, the 28-kDa movement protein, and calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (CIP). The reaction products were then analyzed by TLC. As expected, CIP could remove the 32P moiety from both 5′-α-32P-RNA (Fig. 3A, lane 5) and 5′-γ-32P-RNA (Fig. 3B, lane 5); nonetheless, the helicase-like domain removed the 32P moiety only from 5′-γ-32P-RNA (Fig. 3B, lane 2). Despite having NTPase and RNA-binding activity, the 28-kDa movement protein showed negligible activity for releasing the 32P moiety from either of the RNA substrates (Fig. 3, lane 4). The GKS-to-GAA mutation disabled the activity of removing the 32P moiety from 5′-γ-32P-RNA (Fig. 3B, lane 3). To identify the nature of the 5′ end of RNA after treatment with the helicase-like domain, the enzyme-treated products of 5′-α-32P-RNA were further digested by nuclease P1 and the final products were analyzed by TLC. If the 5′ γ phosphate of an RNA molecule had been cleaved off by the helicase-like domain, further treatment with nuclease P1 would liberate [α-32P]GDP from the 5′ end of the radiolabeled RNA and would liberate [32P]GMP from the rest of the RNA substrate. On the other hand, if the helicase-like domain had broken the phosphodiester bond between α and β phosphates, only [32P]GMP would be generated after the nuclease P1 reaction. [α-32P]GTP and [32P]GMP would appear upon the hydrolysis of intact 5′-α-32P-RNA by nuclease P1. The results of this experiment are shown in Fig. 4. Digestion of 5′-α-32P-RNA with the helicase-like domain and subsequently with nuclease P1 gave rise to a spot corresponding to GDP on the TLC plate in addition to those corresponding to GMP and GTP (Fig. 4, lane 1); however, treatment with nuclease P1 alone (Fig. 4, lane 4) generated spots corresponding to GMP and GTP only. No GDP spot appeared in the reactions with either the GKS→GAA mutant (Fig. 4, lane 2) or the 28-kDa protein (Fig. 4, lane 3). These results indicate that the helicase-like domain attacked the phosphodiester bond between γ and β phosphates. Taken together, the above data confirm that the helicase-like domain indeed has an RNA 5′-triphosphatase activity and that the GKS motif is required for this activity. The full-length replicase, the N-terminal capping domain, and the C-terminal RdRp domain were also examined for RNA 5′-triphosphatase activity to assure that the activity identified above is not an artifact due to the protein truncation. The full-length replicase was also able to remove the 5′ γ phosphate from the RNA substrate (Fig. 5, lane 1). Nonetheless, the N-terminal (Fig. 5, lane 4) and C-terminal domains (Fig. 5, lane 5) did not show any appreciable activity. The results affirm the existence of an RNA 5′-triphosphatase in the helicase-like domain. One picomole of the helicase-like domain was able to catalyze approximately 4 pmol of RNA hydrolysis per s under the conditions described in Materials and Methods.

FIG. 3.

The removal of the 5′-terminal 32P moiety from RNA molecules (A) 5′-α-32P-RNA. (B) 5′-γ-32P-RNA. 5′-32P-RNA was incubated with 30 ng of various enzyme preparations (lanes 1, blank; lanes 2, wild-type helicase-like domain; lanes 3, motif I mutant [GKS→GAA]; lanes 4, 28-kDa movement protein; lanes 5, CIP), and the reaction products were analyzed by TLC as described in Materials and Methods.

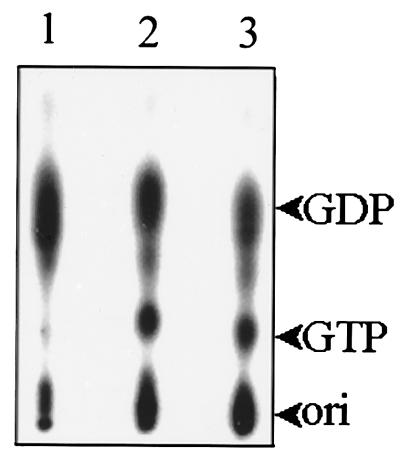

FIG. 4.

The nature of the 5′-terminal guanylate of RNA molecules. The 5′-α-32P-RNA substrate was first treated with 30 ng of various enzyme preparations (lane 1, wild-type helicase-like domain; lane 2, motif I mutant [GKS→GAA]; lane 3, 28-kDa movement protein; lanes 4 and 5, blank). The recovered RNA product was then treated with nuclease P1 as described in Materials and Methods. + and −, addition and omission of nuclease P1, respectively, in the second incubation. Standards (GTP, GDP, and GMP; arrowheads) were run along with the radiolabeled samples in a same TLC sheet, visualized under UV at 254 nm.

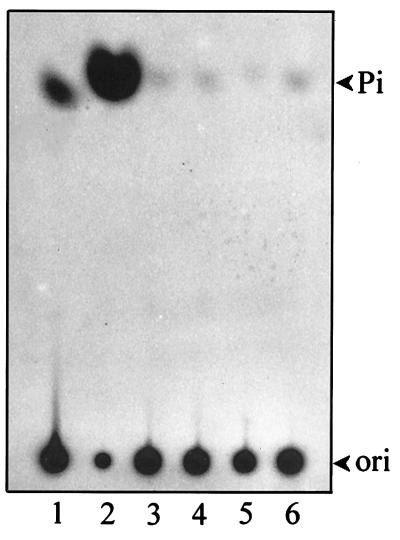

FIG. 5.

Association of RNA 5′-triphosphatase activity with the helicase-like domain of BaMV replicase. The 5′-γ-32P-RNA substrate was incubated with 30 ng of various enzyme preparations (lane 1, full-length replicase; lane 2, helicase-like domain; lane 3, motif I mutant of helicase-like domain; lane 4, capping enzyme domain; lane 5, RdRp domain; lane 6, blank), and the products were analyzed by TLC.

Factors affecting NTPase and RNA 5′-triphosphatase activities.

Divalent cations including Cu2+, Co2+, Ni2+, Zn2+, Mg2+, and Mn2+ were examined for their ability to support the NTPase and RNA 5′-triphosphatase activities. The results indicate that Mg2+ or Mn2+ was essential for both activities (Fig. 6). Other tested cations failed to support the activities except Zn2+, which enabled the enzyme to exhibit a weak RNA 5′-triphosphatase activity. The similarity between the two activities in the aspects of metal ion preference and the essential role of the GKS motif imply that NTPase and RNA 5′-triphosphatase have overlapping catalytic sites. To address this hypothesis, we further tested the competitive effect of RNA on NTPase activity. Inclusion of an ∼3 μM RNA transcript in a 30-min standard GTPase reaction inhibited GTPase activity to a significant extent (Fig. 7, lane 3). The inhibitory effect of guanylylimidodiphosphate (GIDP), a nonhydrolyzable analog of GTP, on GTPase activity was also apparent (Fig. 7, lane 2).

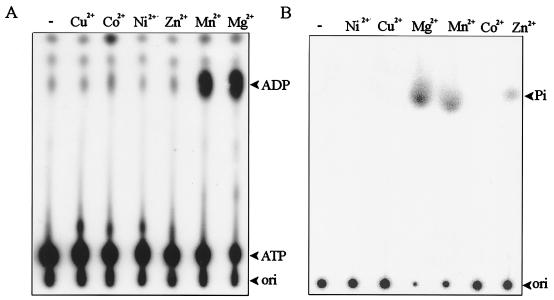

FIG. 6.

The metal dependence of the NTPase and RNA 5′-triphosphatase activities. The metal-free helicase-like domain of the BaMV replicase was used for an ATPase assay (A) and an RNA 5′-triphosphatase assay (B). Various divalent cations (5 mM) were included in the enzymatic reactions as described in Materials and Methods. −, blank reaction in which no metal was included.

FIG. 7.

The inhibition effects of GIDP and RNA on GTPase activity. The GTPase assay was carried out at 37°C for 30 min in a 10-μl reaction mixture (50 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 5 mM Mg2+, 5 mM DTT, 0.5 μCi of [α-32P]GTP, 40 U of RNase inhibitor, and 30 ng of the helicase-like domain) that contained either 2 mM GIDP (lane 2) or 3 μM 5′ plus-strand RNA of BaMV (lane 3). Lane 1, standard GTPase reaction. The products were then analyzed by TLC.

Formation of cap structure at the 5′ end of RNA.

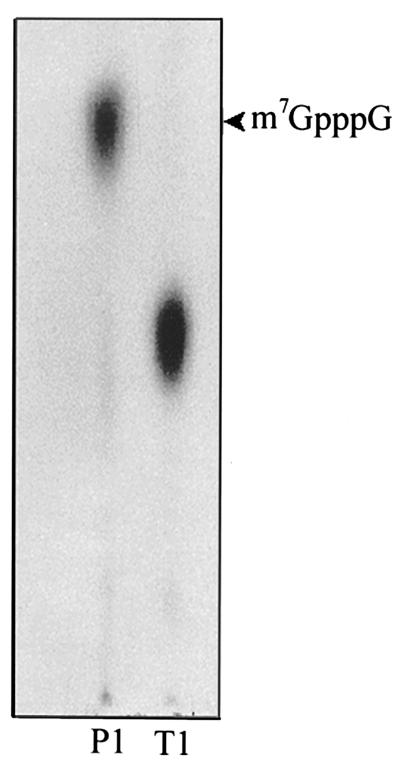

To confirm the biological significance of the 5′-triphosphatase activity of the helicase-like domain in cap formation in collaboration with the capping enzyme domain, we performed the following experiment. The capping enzyme domain was purified as described above, and a 200-nucleotide RNA substrate corresponding to the 5′ plus strand of BaMV was produced by in vitro transcription. The RNA substrate was first treated with the helicase-like domain for 30 min, and then the purified capping enzyme domain, [α-32P]GTP, and AdoMet were added to the mixture to initiate the RNA capping reaction. In the control experiment, the RNA substrate was treated only with buffer in the first-step reaction. The results are shown in Fig. 8. The RNA substrate was readily radiolabeled if the substrate had been treated with the helicase-like domain (Fig. 8A). In contrast, only a very low level of labeling on the control RNA substrate was observed (Fig. 8B). It was also noted that the radiolabeling of RNA occurred only in the presence of AdoMet, indicating that the labeling is due to the activity of the BaMV capping enzyme. To characterize the cap structure, the 32P-labeled RNA product of the in vitro capping reaction was digested with either nuclease P1 or RNase T1. Nuclease P1 hydrolyzes the 5′-3′ linked phosphodiester bonds of single-stranded RNA but cannot hydrolyze the 5′-5′ linked phosphodiester bonds of the cap. RNase T1 specifically attacks guanine nucleotides and generates products with terminal guanosine-3′-phosphate groups. The digested products were then analyzed for the presence of the 32P-labeled cap structure by TLC (Fig. 9). Treatment with nuclease P1 gave rise to a 32P-labeled spot that corresponds to the spot of the m7GpppG marker, suggesting that the 5′-terminal structure of the radiolabeled RNA is indeed m7GpppG. The spot generated from the digestion with nuclease T1 should represent m7GpppGp because it has a slower migration rate on PEI TLC plates.

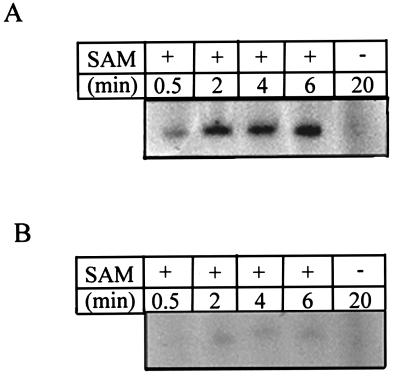

FIG. 8.

Time course of the in vitro RNA-capping reaction. The 5′ plus strand RNA of BaMV was first treated with the helicase-like domain (A) or buffer (B) for 30 min in a standard RNA 5′-triphosphatase reaction condition. Then the capping enzyme of BaMV, [α-32P]GTP, and AdoMet (SAM) were added to start the RNA-capping reaction. At the indicated time points, the capping reaction was stopped, and the labeling of RNA substrate was analyzed by electrophoresis and autoradiography. −, control in which AdoMet was absent from the RNA-capping reaction mixture and the reaction was carried out for 20 min.

FIG. 9.

Cap structure of the RNA product of an in vitro RNA-capping reaction. The purified radiolabeled RNA product of the in vitro capping reaction (see Fig. 8) was treated with either nuclease P1 or RNase T1, and the released products were analyzed by TLC. Standard mG7pppG (arrowhead) was run along with the analyzed products and visualized under UV at 254 nm.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated the enzymatic activities associated with the helicase-like domain of the 155-kDa replicase of BaMV and obtained explicit data proving that this domain could hydrolyze not only ribonucleoside triphosphates (NTPase activity) but also the 5′-triphosphate group of RNA (RNA 5′-triphosphatase activity). Motif I of helicase (GKS) plays an essential role in both activities. A divalent cation (Mg2+ or Mn2+) is definitely required for the catalytic reactions. Moreover, the presence of RNA actually interfered with NTPase activity. Considering these features, we suggest that the two activities have a common catalytic active site with an extended binding pocket for the RNA molecule. To inquire whether the possession of RNA 5′-triphosphatase activity is a common feature for any NTP-binding helicase motif-containing protein, we assayed the 28-kDa movement protein of BaMV for this activity. Despite exhibiting NTPase and RNA-binding activities, the 28-kDa movement protein showed no detectable RNA 5′-triphosphatase activity.

In a previous study, we demonstrated that the N-terminal domain of the 155-kDa protein is a capping enzyme that formed a covalent linkage to the m7GMP moiety when it was incubated with GTP and AdoMet (19). In this study, we demonstrated that this capping enzyme could further transfer the m7GMP moiety to the 5′ end of an RNA substrate and could form a typical m7GpppG cap structure. This RNA-capping reaction occurred efficiently only if the RNA substrate had been treated with the helicase-like domain. The results strongly suggest that the capping enzyme domain and the helicase-like domain of BaMV replicase are actually responsible for the formation of the cap structures of viral RNA transcripts. In BaMV, the supposed order of the RNA capping reaction is thus as follows: (i) the 5′ γ phosphate of nascent RNA is removed by the helicase-like domain; (ii) GTP is methylated by the capping enzyme domain; and (iii) the capping enzyme domain transfers the m7GMP moiety, via a m7GMP-enzyme intermediate step, to the 5′-diphosphate terminus of RNA.

The replicase of virus of the alphavirus-like superfamily consists of three putative catalytic domains (RNA capping enzyme, helicase, and RdRp). The three domains are expressed and organized differently in different family members. In potexvirus, they are present within a large polypeptide. In bromovirus, the RNA-capping enzyme and the putative helicase are expressed and organized within a polypeptide (1a protein) and the RdRp is expressed in another polypeptide (2a protein). In alphavirus, the three functional domains are generated from the proteolysis of a large polyprotein and are present as nsP1 (RNA-capping enzyme), nsP2 (helicase), and nsP4 (RdRp) proteins. Analogous to the capping enzyme of BaMV, the N-terminal fragment of 1a protein of brome mosaic virus (2, 15) and nsP1 of Semliki Forest virus (1) exhibit guanylyltransferase activity in an AdoMet-dependent manner. The similar properties of the capping enzymes suggest that the order of RNA capping reaction is conserved throughout the superfamily. Recently, nsP2 of Semliki Forest virus was found to possess RNA 5′-triphosphatase activity (27). Considering the present report of RNA 5′-triphosphatase activity in the helicase-like domain of BaMV replicase, we suggest that the replicases of the members of the superfamily have conserved domain-function relationships. In other words, the possession of RNA 5′-triphosphatase activity on the putative helicase domain of replicase may be universal within the superfamily.

Helicases catalyze the unwinding of double-stranded nucleic acids and have long been thought to play an essential role on various cellular processes such as replication, recombination, transcription, splicing, and translation (6, 21). For single-stranded viruses, the helicase activity has been hypothesized to be required to resolve intramolecular base pairing in the template nucleic acid during the replication of viral genome and to prevent the formation of extensive base pairing between the template and the nascent complementary strand. Direct evidence relating the helicase activity to the replication of viral genome comes from studies of viruses such as bovine viral diarrhea virus (12), vaccinia virus (11), and brome mosaic virus (3). In all the exemplified cases, mutations of the conserved motif I or motif II or both abolished the helicase activity and concomitantly the synthesis of viral RNA. As with other viruses, helicase activity is considered essential for BaMV to complete its replication cycle. In this study, we also examined the helicase-like domain for RNA helicase activity. Unfortunately, no convincing data have been obtained yet. Based on the existence of the conserved motifs of RNA helicase, and the recent identification of helicase activity on nsP2 of Semliki Forest virus (8), we believe that the helicase-like domain of BaMV replicase should have RNA helicase activity. The putative helicase activity of BaMV replicase will be pursued continuously by altering the reaction conditions such as by using RNA duplex substrates with different structures. In summary, we highlight the possibility that the helicase-like domain of BaMV replicase might have dual functions involving processes of both RNA replication and formation of the 5′ cap structure of RNA.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Ban-Yang Chang for the generous gift of the 28-kDa movement protein of BaMV and Muthukumar Nadar for the preparation of the manuscript.

This work was supported by grant NSC89-2311-B-005-027-B11 from the National Science Council, Republic of China.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahola T, Kääriäninen L. Reaction in alphavirus mRNA capping: formation of a covalent complex of nonstructural protein nsP1 with 7-methyl-GMP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:507–511. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.2.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahola T, Ahlquist P. Putative RNA capping activities encoded by brome mosaic virus: methylation and covalent binding of guanylate by replicase protein 1a. J Virol. 1999;73:10061–10069. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.12.10061-10069.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahola T, den Boon J A, Ahlquist P. Helicase and capping enzyme active site mutations in brome mosaic virus protein 1a cause defects in template recruitment, negative-strand RNA synthesis, and viral RNA capping. J Virol. 2000;74:8803–8811. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.19.8803-8811.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Angell S M, Davies C, Baulcombe D C. Cell-to-cell movement of potato virus X is associated with a change in the size-exclusion limit of plasmodesmata in trichome cells of Nicotiana clevelandii. Virology. 1996;216:197–201. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beck D L, Guilford P J, Voot D M, Andersen M T, Forster R L. Triple gene block proteins of white clover mosaic potexvirus are required for transport. Virology. 1991;183:695–702. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90998-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bird L E, Subramanya H S, Wigley D B. Helicases: a unifying structural theme? Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1998;8:14–18. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(98)80004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bisaillon M, Lemay G. Characterization of the reovirus λ1 protein RNA 5′-triphosphatase activity. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:29954–29957. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.47.29954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Cedrón M G, Ehsani N, Mikkola M L, García J A, Kääriäninen L. RNA helicase activity of Semliki Forest virus replicase protein NSP2. FEBS Lett. 1999;448:19–22. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00321-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gorbalenya A E, Koonin E V. Helicase: amino acid sequence comparisons and structure-function relationships. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1993;3:419–429. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gros C, Wengler G. Identification of an RNA-stimulated NTPase activity in the predicted helicase sequence of the rubella virus nonstructural protein. Virology. 1996;217:367–372. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gross C H, Shuman S. The nucleoside triphosphatase and helicase activities of vaccinia virus NPH-II are essential for virus replication. J Virol. 1998;72:4729–4736. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.6.4729-4736.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gu B, Liu C, Lin-Goerke J, Maley D R, Gutshall L L, Feltenberger C A, del Vecchio A M. The RNA helicase and nucleotide triphosphatase activities of the bovine viral diarrhea virus NS3 protein are essential for viral replication. J Virol. 2000;74:1794–1800. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.4.1794-1800.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kadaré G, David C, Haenni A-L. ATPase, GTPase, and RNA binding activities associated with the 206-kilodalton protein of turnip yellow mosaic virus. J Virol. 1996;70:8169–8174. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.8169-8174.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kadaré G, Haenni A-L. Virus-encoded RNA helicases. J Virol. 1997;71:2583–2590. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.2583-2590.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kong F, Sivakumaran K, Kao C. The N-terminal half of the brome mosaic virus 1a protein has RNA capping-associated activities: specificity for GTP and S-adenosylmethionine. Virology. 1999;259:200–210. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koonin E V, Dolja V V. Evolution and taxonomy of positive-strand RNA viruses: implication of comparative analysis of amino acid sequence. Biochem Mol Biol. 1993;28:375–430. doi: 10.3109/10409239309078440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lanzetta P A, Alvarez L J, Reinach P S, Candia O A. An improved assay for nanomole amounts of inorganic phosphate. Anal Chem. 1979;100:95–97. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(79)90115-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Y-I, Cheng Y-E, Huang Y-L, Tsai C-H, Hsu Y-H, Meng M. Identification and characterization of the Escherichia coli-expressed RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of bamboo mosaic virus. J Virol. 1998;72:10093–10099. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.10093-10099.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Y-I, Chen Y-J, Hsu Y-H, Meng M. Characterization of the AdoMet-dependent guanylyltransferase activity that is associated with the N terminus of bamboo mosaic virus replicase. J Virol. 2001;75:782–788. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.2.782-788.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin N-S, Lin B-Y, Lo N-W, Hu C-C, Chow T-Y, Hsu Y-H. Nucleotide sequence of the genomic RNA of bamboo mosaic potexvirus. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:2513–2518. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-9-2513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20a.Liou D-Y, Hsu Y-H, Wung C-H, Wang W-H, Lin N-S, Chang B-Y. Functional analyses and identification of two arginine residues essential to the ATP-utilizing activity of the triple gene block protein 1 of bamboo mosaic potexvirus. Virology. 2000;277:336–344. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lohman T M, Bjornson K P. Mechanisms of helicase-catalyzed DNA unwinding. Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:169–214. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.001125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mizumoto K, Kaziro Y. Messenger RNA capping enzymes from eukaryotic cells. Prog Nucleic Acids Res Mol Biol. 1987;34:1–28. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60491-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rikkonen M, Peränen J, Kääriäninen L. ATPase and GTPase activities associated with Semliki Forest virus nonstructural protein nsP2. J Virol. 1994;68:5804–5810. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.5804-5810.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rozanov M N, Koonin E V, Gorbalenya A E. Conservation of the putative methyltransferase domain: a hallmark of the “Sindbis-like” supergroup of positive-strand RNA viruses. J Gen Virol. 1992;73:2129–2134. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-8-2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shuman S. Capping enzyme in eukaryotic mRNA synthesis. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1995;50:101–129. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60812-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tamura J K, Gellert M. Characterization of the ATP binding site on Escherichia coli DNA gyrase. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:21342–21349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vasiljeva L, Merits A, Auvinen P, Kääriäninen L. Identification of a novel function of the alphavirus capping apparatus. RNA 5′-triphosphatase activity of Nsp2. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:17281–17287. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M910340199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wung C-H, Hsu Y-H, Liou D-Y, Huang W-C, Lin N-S, Chang B-Y. Identification of the RNA-binding sites of the triple gene block protein 1 of bamboo mosaic potexvirus. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:1119–1126. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-5-1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]