Abstract

The psychological states of wives and husbands are thought to influence each other to varying degrees. However, relatively little is known from a longitudinal observation about the effects of spouses’ psychological distress and well-being on their mental health. To address this question, we analyzed the TWIN Study II dataset using a three-wave annual survey of the psychological distress and happiness of 379 dual-income families. A group-based trajectory modeling analysis was conducted to identify psychological distress patterns and happiness over time, while estimating the effects of spouses’ psychological distress and happiness and their own job demands, control, and support as time-varying covariates. The two- or three-group trajectory model best fit husbands’ and wives’ psychological distress and happiness trajectories. Husbands’ trajectories of psychological distress and happiness were significantly influenced by wives’ happiness as well as their own job demands and/or support, whereas wives’ happiness and psychological distress were not.

Keywords: Longitudinal data, Group-based trajectory modeling, Couple’s data, Psychological distress, Happiness, Time-varying covariate

Longitudinal data are at the core of research regarding changes in various outcomes across a wide range of disciplines1). Work stress research, previously mostly cross-sectional, is now predominantly conducted through longitudinal studies. Individual-level longitudinal data are effective in capturing changes because they effectively track the same sample over time. Currently, the appropriate analysis method is multilevel modeling2), which yields an average trajectory (fixed effects) with individual variations around the average (subject-specific random effects). This information is useful for clarifying trends in the entire sample. However, upon closer inspection, we noticed that some subgroups exhibited distinct trajectories. Therefore, fine-grained modeling of these individual differences appears to be more useful for representing real-world situations.

In analyzing longitudinal data on workers’ stress and health, for example, researchers may be interested in the number of trajectories or patterns of change over time in the variables (e.g., stress at work and mental health), as well as the possible factors influencing the trajectories. The group-based trajectory model (GBTM)3) is designed to address these questions by extracting the “phenotype” of the longitudinal data. The GBTM is a growth mixture model used to identify distinct subgroups that exhibit similar progressions in symptoms and behaviors. Its advantage is that both time-stable and time-varying covariates can be entered into the trajectory estimation; further, their contribution to the trajectory can be checked.

In the symposium titled “New Longitudinal Insights into Work Stress & the Well-being Process” (ICOH-WOPS 2023), we presented the GBTM analysis used to examine longitudinal changes in stress and the mental health of dual-earner couples with preschool children. The psychological states of wives and husbands are believed to influence each other to varying degrees. Several cross-sectional surveys4) (i.e., studies on work-family life balance) have yielded significant associations. However, relatively little is known from longitudinal observations about the effects of spouses’ psychological distress and well-being on their own mental health. Therefore, we performed a GBTM analysis.

We analyzed data collected in the Tokyo Work–Family Interface Study II5), a three-wave annual survey of 379 dual-income couples with preschool children. Data from 135 wives who responded to the mental health measures in all three waves (follow-up rate: 35.6%) and 115 of their husbands who responded were used. However, the final analyses including spouses’ responses were based on data from 114 wives and 112 husbands, due to the lack of responses from husbands. Mean ages (in years) and SDs of wives and husbands at wave 1 were 38.0 ± 4.3 and 39.3 ± 5.7, respectively. The survey questionnaire addressed work stress, work-family life balance, parenting style, mental health, and other issues. We only analyzed work stress, support, and mental health. To avoid reducing the sample size as much as possible, the confounding factors such as age, education, and income, were not included in the analyses. Mental health was measured by both the negative and positive aspects of psychological distress and happiness. Workers’ happiness and well-being were highlighted as major positive outcomes in the workplace4, 5). Details of this study are described elsewhere6).

Workplace stress data were collected using several subscales for job demands, control, and social support from the Brief Job Stress Questionnaire7), a standard questionnaire for evaluating occupational stress. All items were scored on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (disagree) to 4 (agree). The coefficient α for each wave ranged from 0.71 to 0.82 for job demand, 0.76 to 0.81 for control, and 0.81 to 0.87 for support. Psychological distress was assessed using the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale8, 9), a six-item self-report measure of psychological distress in the general population. Participants indicated how often they experienced six different feelings or experiences during the past 30 d on a five-point Likert scale that ranged from 0 (never) to 4 (all the time). The coefficient α range was 0.87–0.91. Happiness was measured using a single item. Respondents were asked to rate their overall happiness on a 0–10 scale, ranging from 0 (not happy at all) to 10 (very happy). One-item happiness scales are often used in happiness or well-being research10).

A Stata plugin “traj”11) was used to conduct GBTM analyses regarding the mental health of wives and husbands. Referring to the procedures of Miller-Lewis et al.12), we fitted a series of models and utilized the following criteria to identify the best fit trajectories: (1) whether the trajectory shape was statistically significant at a p level of 0.05 (the analysis began by modeling a single group trajectory, with a cubic specification for trajectory shape; we dropped non-significant polynomial terms); (2) whether the Bayesian Information Criterion for models with increasing numbers of groups showed evidence of improved fit; and (3) whether at least 5% of the sample was identified for each trajectory membership. Once the optimal number of trajectories was determined, time-varying covariates (i.e., one’s own job stress variables and spouse’s mental health) were entered into the estimation of trajectories to check for their significant influence on the trajectory.

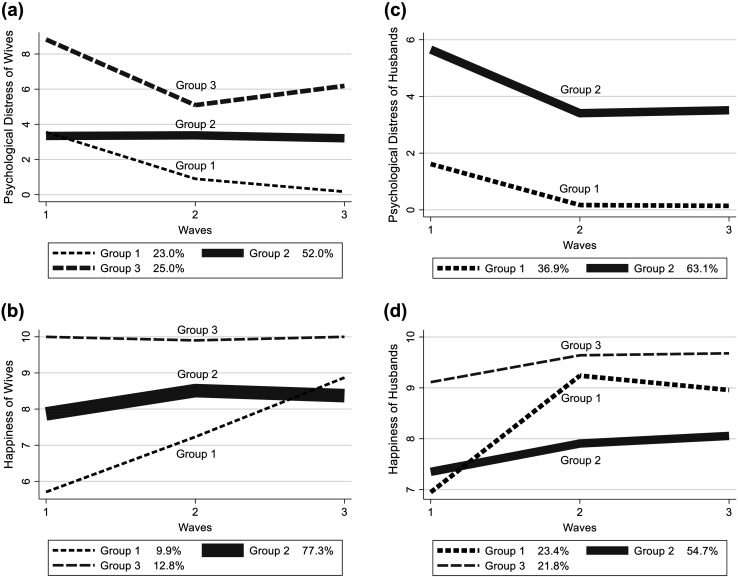

Table 1 shows the maximum likelihood estimates of the time-varying covariates in the trajectory groups for the mental health of wives and husbands. The GBTM analyses of wives’ psychological distress indicated the presence of three trajectories (Fig. 1a). The trajectory of Group 2, which included half of the wives, was not affected by any of the covariates, whereas the trajectories of the other two groups were affected by workplace support. The trajectory of Group 1, to which one-fifth of the wives belonged, was significantly influenced by job demands and husbands’ psychological distress. As shown in Fig. 1b, three trajectories were extracted from the wives’ happiness. Workplace support significantly influenced all trajectories. The trajectories of participants in Groups 1 and 3 were also influenced by their own job demands, whereas no peculiar effects were observed in terms of husbands’ mental health. A marginal effect of husbands’ happiness was observed for Group 2 participants.

Table 1. Effects of one’s own work stress and spouses’ mental health on the trajectory groups for wives’ and husbands’ mental health.

| Time-varying covariates | Wives | Husbands | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological distress | Happiness | Psychological distress | Happiness | |||||||||

| Group 1 (23.0%) | Group 2 (52.0%) | Group 3 (25.0%) | Group 1 (9.9%) | Group 2 (77.3%) | Group 3 (12.8%) | Group 1 (36.9%) | Group 2 (63.1%) | Group 1 (23.4%) | Group 2 (54.7%) | Group 3 (21.8%) | ||

| One’s own stress at work | ||||||||||||

| Job demands | 1.10* | 0.12 | 0.20 | –0.62** | –0.01 | –0.60** | 0.90** | 0.16 | –0.05 | 0.02 | 0.04 | |

| Control | –0.50† | –0.10 | –0.18 | 0.19 | 0.04 | 0.10 | –0.30 | –0.17 | 0.14 | 0.17* | 0.19† | |

| Support | –0.81*** | 0.09 | –0.83*** | 0.30* | 0.07* | 0.51* | –0.19 | –0.45*** | 0.42*** | 0.06† | 0.09† | |

| Spouse’s mental health | ||||||||||||

| Psychological distress | 0.49** | 0.03 | –0.14 | –0.11 | –0.03 | 0.34 | 0.21 | 0.15† | 0.10* | –0.05† | 0.01 | |

| Happiness | 0.04 | –0.07 | –0.35 | –0.01 | 0.15† | –0.79 | 0.20 | –0.80*** | 0.91*** | 0.06 | 0.13 | |

Table entities represent the maxmum likelihood estimates of time-varying covariates for the individual trajectory.

†p<0.10, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Fig. 1.

Trajectories of the three-year observation of wives’ and husbands’ mental health.

(a) wives’ psychological distress, (b) wives’ happiness, (c) husbands’ psychological distress, and (d) husbands’ happiness.

The GBTM analyses of husbands’ psychological distress indicated the presence of two trajectories (Fig. 1c). The trajectories of Group 2, which accounted for two-thirds of the husbands, were influenced significantly by workplace support and the happiness of their wives and marginally by their wives’ psychological distress. Group 1 participants were influenced solely by their own job demands. As shown in Fig. 1d, three trajectories were extracted from husbands’ happiness. Only Group 1, to which one-fourth of the husbands belonged, was significantly influenced by workplace support, wives’ happiness, and psychological distress. The trajectory of Group 2, which included half of the husbands, was influenced significantly by job control and marginally by workplace support and wives’ psychological distress. The trajectory of Group 3 was marginally influenced by job control and workplace support.

The differences between married couples observed in this study may reflect the traditional role expectations within Japanese households. In Japan, wives play a more important role than husbands in housework and childrearing13), and this tendency does not change even among dual-earner couples14). Wives must devote much time and energy to housework and childcare and do not have much time to pay attention to their husbands’ situations. Instead, workplace support, which reflects the degree of workplace understanding of wives’ work-life balance, is more likely to affect their mental health. Husbands spend more time on work-related activities than wives do. Therefore, situations may arise in which some husbands feel that their wives have imposed their role in the home on them (Table 1, Fig. 1).

This study has some limitations. The sample size and three waves of observation were insufficient for extracting various trajectories and examining the effects of the covariates comprehensively. Low participation rate, particularly for husbands was another limitation. Also, to avoid reducing the sample size as much as possible, the confounding factors such as age, education, and income, were not taken into account. Additionally, participants were limited to dual earners with preschool children; thus, some working mothers might not have taken care of their husbands. Despite these limitations, our GBTM analysis of the longitudinal data provided the following insights that could not be obtained using other analytical methods: (1) we found some patterns of individual variations through a three-year follow-up period and (2) in some groups, husbands’ psychological distress and happiness trajectories seemed to be significantly influenced by their wives’ mental health (e.g., happiness). Conversely, husbands had little influence on their wives’ happiness and psychological distress.

Further studies using data from more representative samples of parents and couples are warranted to confirm the present findings. Considering a higher dropout rate through a follow-up study, participating couples could have good relationships. However, while a husband may seem concerned about his wife, she may not be as concerned about him. Revealing the truth of this phenomenon is sometimes crucial.

Ethical Approval

All procedures involving human participants were performed according to ethical standards of the Institutional Research Committee of the University of Tokyo and 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare regarding this study.

References

- 1.Andruff H, Carraro N, Thompson A, Gaudreau P, Louvet B. (2009) Latent class growth modelling: a tutorial. Tutor Quant Methods Psychol 5, 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bryk AS, Raudenbush SW .(1992) Hierarchical linear models: applications and data analysis methods. Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nagin DS, Odgers CL. (2010) Group-based trajectory modeling in clinical research. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 6, 109–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shimazu A, Demerouti E, Bakker AB, Shimada K, Kawakami N. (2011) Workaholism and well-being among Japanese dual-earner couples: a spillover-crossover perspective. Soc Sci Med 73, 399–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakata A. (2017) Work to live, to die, or to be happy? Ind Health 55, 93–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shimazu A, Shimada K, Watai I .(2014) Work-family balance and well-being among Japanese dual-earner couples: a spillover-crossover perspective. In: Contemporary occupational health psychology: global perspectives on research & practice (Volume 3), Leka S, Sinclair R (Eds.), 84–96. Wiley-Blackwell, Chichester. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shimomitsu T, Yokoyama K, Ono Y, Maruta T, Tanigawa T. (1998) Development of a novel brief job stress questionnaire. In: Report of the Research Grant for the Prevention of Work-Related Diseases from the Ministry of Labour. Kato S (Ed.), Ministry of Labour, Tokyo, 107–15 (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, Hiripi E, Mroczek DK, Normand SL, Walters EE, Zaslavsky AM. (2002) Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med 32, 959–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Furukawa TA, Kawakami N, Saitoh M, Ono Y, Nakane Y, Nakamura Y, Tachimori H, Iwata N, Uda H, Nakane H, Watanabe M, Naganuma Y, Hata Y, Kobayashi M, Miyake Y, Takeshima T, Kikkawa T. (2008) The performance of the Japanese version of the K6 and K10 in the World Mental Health Survey Japan. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 17, 152–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lyubomirsky S, King L, Diener E. (2005) The benefits of frequent positive affect: does happiness lead to success? Psychol Bull 131, 803–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones BL, Nagin D .(2018) A Stata plugin for estimating group-based trajectory models. Carnegie Mellon University. journal contribution.

- 12.Miller-Lewis LR, Sawyer AC, Searle AK, Mittinty MN, Sawyer MG, Lynch JW. (2014) Student-teacher relationship trajectories and mental health problems in young children. BMC Psychol 2, 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Japan Cabinet Office. Work-life balance report 2017. Kyodo-Sankaku 2018, 111, 2–5. http://www.gender.go.jp/public/kyodosankaku/2018/201805/pdf/ 201805.pdf (Accessed June 1, 2024) (in Japanese).

- 14.Shimazu A, Bakker AB, Demerouti E, Fujiwara T, Iwata N, Shimada K, Takahashi M, Tokita M, Watai I, Kawakami N. (2020) Workaholism, work engagement and child well-being: a test of the spillover-crossover model. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17, 6213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Japan Cabinet Office. Work-life balance report 2017. Kyodo-Sankaku 2018, 111, 2–5. http://www.gender.go.jp/public/kyodosankaku/2018/201805/pdf/ 201805.pdf (Accessed June 1, 2024) (in Japanese).