Abstract

Background

Coarctation of the aorta (CoA) accounts for 5% to 7% of congenital heart disease, with an incidence of 0.3 to 0.4 per 1000 live births. Surgery was the only choice of therapy for CoA until 1982 when balloon angioplasty became an available alternative for its treatment. Re‐coarctation, aneurysm and aortic dissection remain the disadvantages of both treatments. To avoid those disadvantages, in 1990 endovascular stents were introduced for native coarctation and re‐coarctation and since then they have become an alternative approach to surgical repair. The best approach to treat the CoA, whether open surgery or by stent placement, is not clear.

Objectives

To analyze the effectiveness and safety of stent placement compared with open surgery in patients with coarctation of the thoracic aorta.

Search methods

The Cochrane Peripheral Vascular Diseases Group searched their Specialised Register (last searched September 2011) and CENTRAL (2011, Issue 3). We also searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, AMED, Web of Science and LILACS (last searched in September 2011). We evaluated the located references and applied the inclusion criteria to selected studies. There was no restriction on language.

Selection criteria

Randomized or quasi‐randomized controlled clinical trials that compared patients with CoA undergoing open surgery or stent placement.

Data collection and analysis

The review authors independently assessed the studies identified for eligibility for inclusion. We excluded studies after a consensus meeting.

Main results

All identified studies were screened and had the selection criteria applied to the title and abstract. In total, we selected five studies for full‐text analysis. After detailed evaluation, we excluded all studies because there was no comparison between stent placement and open surgery.

Authors' conclusions

There is insufficient evidence with regards to the best treatment for coarctation of the thoracic aorta. This review suggests a need to perform a randomized controlled clinical trial with emphasis on the allocation method, evaluation of primary outcomes, size and quality of the sample, and long‐term follow‐up.

Keywords: Humans; Infant, Newborn; Stents; Aortic Coarctation; Aortic Coarctation/surgery

Plain language summary

Treatments for coarctation of the thoracic aorta

Coarctation of the aorta (CoA) is a congenital narrowing of the lumen in a section of the aorta. The narrowing is most commonly in the upper thoracic aorta but can occur in the abdominal aorta. It is present at birth and males are more often affected than females. Clinical symptoms are variable and depend on the position, degree and extent of the narrowed segment of the aorta. Other congenital heart abnormalities may also be present. In general, the diagnosis is made by finding a difference in pulsations and blood pressure between the upper body and arms and the lower body and legs. If left unrepaired, average survival is 31 years. The treatment of CoA is intended to improve life expectancy and quality of life by reducing the incidence of aortic and cardiac disabling conditions such as aneurysm (dilation) of the ascending aorta, coronary artery disease, high blood pressure, and aortic and mitral valvular disease. The treatment of CoA consists of enlarging of the narrowed segment. Traditionally this required open heart surgery. Balloon angioplasty became available as an alternative treatment in the 1980s but recurrence, aneurysm and aortic dissection (a tear in the inner wall of the aorta causing blood to flow between the layers of the blood vessel wall) remained disadvantages of both treatments. In the early 1990s, endovascular stents were introduced and have become an alternative approach to surgical repair. The present review looked at the available evidence for the effectiveness of open surgery compared with placing a stent in the coarctation of the thoracic aorta. The review authors searched the medical literature but they did not found any studies that compared open surgery and stent placement for the treatment of coarctation of the thoracic aorta. The treatment of CoA is a challenging procedure and the centers that perform this treatment have a well‐established strategy for patients with CoA; the strategy is in accordance with the experience of involved professionals and local resources. In both situations experience and resources have improved the results of the treatment. However a more concrete and long‐term analysis of these strategies is needed.

Background

Description of the condition

Coarctation of the aorta (CoA) in its classical form describes congenital narrowing of the isthmus around the insertion of the arterial duct, which is the most common site of obstruction (thoracic coarctation) although the term includes narrowing in any region from the aortic arch to the abdominal aorta (Egan 2009; Ramnarine 2005). Coarctation of the aorta accounts for 5% to 7% of congenital heart disease, with an incidence of 0.3 to 0.4/1000 live births (Kuehl 1999; Mitchell 1971; Rosenthal 2005), and it is approximately two to three times more common in males (Baylis 1956; Jenkins 1999). The morphological spectrum of abnormalities ranges from a discrete stenosis distal to the left subclavian artery to a hypoplasic transverse arch and aortic isthmus (Mullen 2003).

The age at presentation is related to the severity rather than the site of obstruction, as a result of cardiac failure or occasionally stroke, aortic dissection or endocarditis (Jenkins 1999). Coarctation of the aorta is frequently associated with other congenital cardiac abnormalities. In patients submitted to open surgical correction, a bicuspid aortic valve was present in 40% and other cardiac defects were uncommon (Gibbon 1969). In a series of 100 patients who died from CoA, exclusive of cases of bicuspid aortic valve, 91% of patients aged under six months had other severe cardiac congenital defects compared with 74% in the group older than six months (Becker 1970). The spectrum of clinical manifestations of CoA is variable and depends on the degree of obstruction and the presence of other associated cardiac lesions (Rosenthal 2005).

Although the antenatal diagnosis of CoA improves survival and reduces morbidity (Eapen 1998; Franklin 2002) it is not frequent (Wren 2008). Nowadays the vast majority of CoA are identified and treated in the first year of life and adult presentation is becoming less frequent (Rosenthal 2005). The diagnosis is made simply and easily in almost all cases by finding a difference in arterial pulsations and blood pressure in the upper and lower extremities (Gibbon 1969) and it can be made rapidly by non‐invasive tests such as echocardiography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Nielsen 2005). Despite the increased diagnosis of CoA in childhood some cases are still not diagnosed until adulthood (Franklin 2002).

Natural history studies show that the median age of death for unrepaired coarctation of the aorta is 31 years; 76% of deaths are attributed to complications of aortic coarctation (25.5% cardiac failure, 21% aortic rupture, 18% bacterial endocarditis and 11.5% intracranial hemorrhage) (Campbell 1970).

Description of the intervention

The first successful surgical repair of CoA was reported by Crafoord and Nylin in 1945 (Crafoord 1945; Gross 1945). Since then, a number of publications have shown satisfactory results in relation to better control pressure and reduced related complications, and increased survival (Corno 2001; Harrrison 2001; Lerberg 1982). The most common surgical repair is resection with end‐to‐end anastomosis; other techniques such as resection with replacement by a tube graft, patch aortoplasty, and bypass graft are used less frequently (Backer 1998; Cobanoglu 1998; Walhout 2003). Re‐coarctation and residual hypertension are the most frequent complications after surgery, occurring in 3% to 4% and 25% to 38% of patients respectively (Backer 1998; Cohen 1989; O'Sullivan 2002; Ou 2004).

Surgery was the only choice of therapy for CoA until 1982 when Lock 1983 published the results of a case series of eight newborn babies with CoA associated with other congenital cardiac abnormalities who underwent balloon angioplasty. Since then, balloon angioplasty has become an available option to treat these patients. However, re‐coarctation, aneurysm formation and aortic dissection remain disadvantages of both treatments (Ebeid 1997; Golden 2007; Hamdan 2001; Qureshi 2005).

How the intervention might work

In the beginning of 1990s, endovascular balloon‐expandable stents were introduced in place of balloon dilatation for both native coarctation and re‐coarctation in children and adults (Bulbul 1996; Suarez de Lezo 1995). The arguments for these changes were that stents support the integrity of the vessel wall during balloon dilatation and create a more controlled tear, this minimizes tear extension and subsequent dissection or aneurysm formation. However, aneurysms occur in 4% to 7% after stent placement for CoA. (Suarez de Lezo 1999; Thanopoulos 2000).

Why it is important to do this review

Many questions related to the techniques of open surgery or stent placement remain unsolved, such as intra and post‐operative mortality, survival, proportion of hypertension, aortic wall complications and technical complications (Tzifa 2007). In the presence of these unresolved questions, we proposed to conduct a systematic review of the literature comparing the results of open surgery and stent placement in patients with coarctation of the thoracic aorta by considering safety and effectiveness.

Objectives

To analyze the effectiveness and safety of stent placement compared with open surgery in patients with coarctation of the thoracic aorta.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomized or quasi‐randomized controlled prospective clinical trials in patients with coarctation of the aorta and undergoing surgery or placement of an intravascular stent.

The classification of controlled clinical trials (CCT) is also applied to quasi‐randomized studies, where the method of allocation is known but is not considered strictly random. Examples of quasi‐randomized methods of assignment include alternation, date of birth and medical record number (Higgins 2011).

Types of participants

Adults and children of both sexes with coarctation of the aorta. We intended to consider the following subgroup analyses.

Pediatric: neonates (less than one month), infants (from one month to 12 months).

Children (12 months to 15 years of age).

Adults (above 15 years of age).

Both sexes.

The criteria for inclusion of these subgroups were: the presence of coarctation of the aorta, alone or associated with other congenital heart defects; the three types of coarctation (pre‐ductal, juxta‐ductal and post‐ductal).

Types of interventions

Corrective treatment of coarctation of the aorta. The comparison was of intravascular stent placement versus open or minimally‐invasive surgery.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Survival

Quality of life

Mortality by any cause

Secondary outcomes

Hypertension

Aortic wall complication (re‐coarctation, aneurysm formation, intimal tears, dissection)

Other complications (cardiovascular: stroke, peripheral emboli and access artery injury; technical complications: stent migration, balloon rupture, suture dehiscence, paraplegia)

Search methods for identification of studies

There was no restriction on publication language.

Electronic searches

The Cochrane Peripheral Vascular Diseases Group searched their Specialised Register (last searched September 2011) and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (2011, Issue 3), which is part of The Cochrane Library at www.thecochranelibrary.com. See Appendix 1 for details of the search strategy used to search CENTRAL. The Specialised Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and is constructed from weekly electronic searches of MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL and AMED, and through handsearching relevant journals. The full list of the databases, journals and conference proceedings which have been searched, as well as the search strategies used, are described in the Specialised Register section of the Cochrane Peripheral Vascular Diseases Group module in The Cochrane Library (www.thecochranelibrary.com).

Additional searches of MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, AMED, Web of Science and LILACS were carried out using the search strategies shown in Appendix 2, Appendix 3, Appendix 4, Appendix 5, Appendix 6 and Appendix 7.

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of articles retrieved by the electronic searches for additional citations.

Data collection and analysis

We traced references mentioning stent placement and open surgery from the articles identified and we planned to include those that met the criteria. We documented the reasons for exclusion of any article from the selection process. Thereafter, we planned to assess studies fulfilling the inclusion criteria. We planned to independently review articles for inclusion before reconciliation of any discrepant selections.

Selection of studies

We selected studies as described in section 7.2.3 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), using the following methods:

merged search results using reference management software, and removed duplicate records of the same report;

examined titles and abstracts to remove obviously irrelevant reports;

retrieved the full text of the potentially relevant reports;

linked together multiple reports of the same study;

examined full‐text reports for compliance of studies with the eligibility criteria;

corresponded with investigators, where appropriate, to clarify study eligibility;

made final decisions on study inclusion and proceeded to data collection.

Data extraction and management

We planned to process those articles that met the inclusion criteria for data extraction. We planned to extract data independently and check the results for consistency using a prepared data extraction form. We planned to collect the following details: patient characteristics (age, gender); the presence of coarctation of the aorta, alone or associated with other congenital heart defects; consideration of the three types of coarctation (pre‐ductal, juxta‐ductal and post‐ductal); type of corrective treatment: open surgery or endovascular stent placement; morbidity and mortality outcomes; adverse effects reported; and length of trial follow‐up.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We planned to study the characteristics of the included trials to determine their quality. We planned to assess the quality of the studies using quality scores based on the Cochrane Collaboration's 'Risk of bias' tool, described in Section 8.5 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We planned to resolve disagreements by consensus. The parameters we planned to seek included the method and security of randomization, whether assessors and patients were blinded to treatment allocation, whether analysis was by intention to treat, the rate of completion of follow‐up and whether the washout period was adequate, if applicable (that is for cross‐over studies).

Measures of treatment effect

We planned to base quantitative analysis of outcomes on intention‐to‐treat data where these data were available. We planned to express dichotomous data as risk difference (number needed to treat (NNT)) and odds ratio, and we planned to express continuous data as standardized mean differences and mean differences. We planned to use the full random‐effects model to combine results across studies. Differences between the random‐effects model results and those from the theoretically exact fixed‐effect model will describe the potential effects of heterogeneity. We planned to explore differences in the summary statistics between the fixed‐effect and random‐effects models. We planned to summarize each study for including re‐coarctation, hypertension and aneurysm. Furthermore, we planned to combine studies according to the type of surgery or to the method of intervention.

Unit of analysis issues

Given the surgical nature of the interventions, we intended to not consider cross‐over trials as a suitable trial design. Similarly, we intended to not consider cluster randomized trials to be appropriate as there could be other factors at a particular trial site, for example the skill of the surgeon, which could affect the outcome.

Dealing with missing data

We planned to obtain relevant missing data from authors and to carefully perform evaluation of important numerical data such as screened, randomized patients as well as intention‐to‐treat (ITT), as‐treated and per protocol (PP) populations. We planned to investigate attrition rates, for example dropouts, losses to follow‐up and withdrawals, and to critically appraise issues of missing data and imputation methods (for example last observation carried forward (LOCF) (Higgins 2011)).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We planned to first assess statistical heterogeneity using the I2 statistic, which examines the percentage of total variation across studies due to heterogeneity rather than to chance (Higgins 2003). Values of I2 under 40% indicate a low level of heterogeneity and justify use of a fixed‐effect model for meta‐analysis. Values of I2 between 30% and 60% are considered moderate heterogeneity and a random‐effects model can be used. Values of I2 higher than 75% indicate a high level of heterogeneity; in this case meta‐analysis is not appropriate. We planned to consider whether statistical, methodological and clinical heterogeneity are present (Deeks 2008).

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to use funnel plots to assess for the potential existence of small study bias. There are numerous possible explanations for the asymmetry of a funnel plot (Sterne 2002) and we planned to carefully interpret results (Lau 2006). However, we recognise that if the number of eligible studies is small (less than 10) the results are likely to be inconclusive (Sterne 2008).

Data synthesis

In the absence of heterogeneity we planned to use a fixed‐effect model for meta‐analysis. If statistical heterogeneity was moderate, we planned to use a random‐effects model (Deeks 2008). In the presence of substantial statistical heterogeneity between studies we planned to present a qualitative summary (O'Rourke 1989).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned the following subgroup analyses.

Age: neonates (less than one month); infants (from one month to 12 months); children (12 months to 15 years of age); adults above 15 years of age.

Sex.

Types of coarctation (pre‐ductal, juxta‐ductal and post‐ductal).

Coarctation alone or associated with other congenital heart defect.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to conduct sensitivity analysis by analysing the following categories of studies separately: trials with and without adequate randomization and concealment of treatment allocation; trials with and without intention‐to‐treat analysis; trials of low risk, moderate risk and high risk vascular surgery; trials of stent placement. For sensitivity analysis we planned to describe both the main effects within strata and a coefficient (and 95% confidence interval (CI)) describing the interaction between them.

Results

Description of studies

We did not identify any randomized controlled trials comparing stent placement and open surgery for CoA. After screening and reading the full‐text articles, we excluded five articles: three randomized clinical trials compared outcomes of open surgery and balloon angioplasty without stent placement and two were literature reviews.

Results of the search

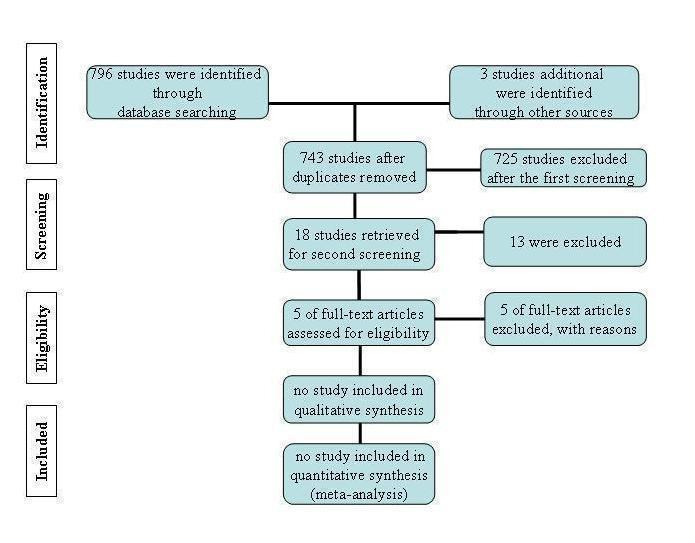

We identified studies in seven databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, CENTRAL, Web of Science, CINAHL, LILACS) and the screened studies had the selection criteria applied to the title and abstract. In total, we selected five articles for full‐text analysis. After detailed evaluation, we excluded all five articles because they were either literature reviews or not comparative randomized clinical trials of open surgery techniques and stent implantation. See the results in a flow diagram in Figure 1 (based on PRISMA 2009).

1.

Results of the search flow diagram

Included studies

We did not identify any randomized controlled trials comparing stent placement and open surgery for CoA.

Excluded studies

After detailed evaluation we excluded five articles (Carr 2006; Cowley 2005; Egan 2009; Hernandez‐Gonzalez 2003; Shaddy 1993). Three studies were excluded because they were not comparative randomized clinical trials between open surgery techniques and stent implantation (Cowley 2005; Hernandez‐Gonzalez 2003; Shaddy 1993) and two articles were excluded because they were literature reviews (Carr 2006; Egan 2009). See also Characteristics of excluded studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

There were no included studies.

Effects of interventions

There were no included studies. Therefore we were unable to perform any of the planned analyses including subgroup analyses, sensitivity analyses and assessments of heterogeneity and reporting bias.

Discussion

Summary of main results

We did not locate any randomized controlled trials that could be included. We selected five full‐text articles for assessing eligibility: three trials and two literature reviews that were then excluded (Characteristics of excluded studies). Therefore we cannot draw any conclusions regarding the effectiveness and safety of open surgery compared with stent placement in patients with coarctation of the aorta.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Coarctation of the thoracic aorta is a complex topic. It has several forms of anatomical presentation, either by location or by its extension, and can be associated with different congenital heart diseases. In addition, the available treatments are diverse. This review looked at stent placement versus surgery treatment options only and therefore not all available interventions were compared. In order to fully reflect the complexity of this topic, for future updates of this review we propose to broaden the review to include all treatment modalities for coarctation of the thoracic aorta.

Quality of the evidence

There were no randomized controlled clinical trials.

Potential biases in the review process

We made every attempt to locate all studies of open surgery compared with stent placement in patients with coarctation of the aorta by searching the main electronic databases. We also tried to contact some of the main specialized centers in the treatment of the CoA.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

We did not find any prospective randomized studies or systematic reviews that compared both interventions. We have only found narrative reviews and case series that analyzed patients undergoing open surgery or stent placement. These studies did not randomize patients or perform comparisons. These types of studies usually suffer from selection bias and represent a cohort of survivors and therefore do not represent the complete spectrum of the patients with coarctation of the aorta. Another limitation of these types of studies is that the analyses generally focus on secondary outcomes (post‐operative mortality, cure of hypertension, aortic wall complications like diameter of the narrowed segment and technical problems like stent migration, phrenic paralyses) and do not evaluate primary outcomes (long‐term survival and quality of life).

Since the first correction of CoA by means of open surgery, performed in 1944 by Crafoord (Crafoord 1945), and the availability of stent placement in the 1990s (Suarez de Lezo 1995) both techniques are continually improving. Nowadays, both modalities of open surgery and stent placement show low post‐operative mortality. However, recoarctation, aortic aneurysm and hypertension are considerable complications associated with both procedures.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There is insufficient evidence to prove which is the best treatment for coarctation of the thoracic aorta: open surgery or stent placement. Indications for treatment modalities depend on the age of patients, type of coarctation and associated cardiac lesions and in particular the preference of the medical team.

Implications for research.

There is insufficient evidence about the best treatment for CoA. This review suggests a need to perform a prospective randomized controlled clinical trial with an emphasis on primary outcomes such as quality of life and long‐term survival.

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 2010 Review first published: Issue 5, 2012

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 6 October 2009 | Amended | Modified protocol |

Acknowledgements

We thank the Peripheral Vascular Diseases Group, especially Heather Maxwell, Karen Welch and Marlene Stewart for their support.

Appendices

Appendix 1. CENTRAL search

| #1 | MeSH descriptor Aortic Coarctation explode all trees | 32 |

| #2 | (coarc* or recoarc*) | 52 |

| #3 | (#1 OR #2) | 52 |

| #4 | MeSH descriptor Stents explode all trees | 2638 |

| #5 | MeSH descriptor Blood Vessel Prosthesis explode all trees | 413 |

| #6 | MeSH descriptor Blood Vessel Prosthesis Implantation, this term only | 429 |

| #7 | MeSH descriptor Balloon Dilatation explode all trees | 3732 |

| #8 | (stent*) | 4304 |

| #9 | (angioplast*) | 5419 |

| #10 | (aortoplast*) | 4 |

| #11 | MeSH descriptor Endovascular Procedures explode all trees | 4784 |

| #12 | (endovasc*):ti,ab,kw | 600 |

| #13 | (endostent*):ti,ab,kw | 1 |

| #14 | (endoprosthe*):ti,ab,kw | 164 |

| #15 | (#4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14) | 10014 |

| #16 | (#3 AND #15) | 7 |

Appendix 2. MEDLINE search

Database: Ovid MEDLINE(R) <1948 to September Week 1 2011>

Search Strategy:

‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐

1 Aortic Coarctation/ (7464)

2 exp Aorta/ (89070)

3 (aorta or aortic).ti,ab. (172512)

4 (constrict$ or stricture? or steno$ or coarctat$).ti,ab. (156412)

5 Constriction, Pathologic/ (17393)

6 (2 or 3) and (4 or 5) (27151)

7 1 or 6 (29270)

8 exp Stents/ (42793)

9 stent$.ti,ab. (47635)

10 Endovascular procedures/ (887)

11 endovascular.ti,ab. (17970)

12 or/8‐11 (66295)

13 7 and 12 (1811)

14 randomized controlled trial.pt. (316611)

15 controlled clinical trial.pt. (83472)

16 randomized.ab. (222175)

17 placebo.ab. (128297)

18 drug therapy.fs. (1497018)

19 randomly.ab. (160174)

20 (trial or groups).ab. (1236595)

21 or/14‐20 (2769470)

22 exp animals/ not humans.sh. (3668851)

23 21 not 22 (2349800)

24 13 and 23 (189)

Appendix 3. EMBASE search

Database: Embase <1980 to 2011 Week 37>

Search Strategy:

‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐

1 aorta coarctation/ (8652)

2 exp aorta/ (82252)

3 (aorta or aortic).ti,ab. (191909)

4 (constrict$ or stricture? or steno$ or coarctat$).ti,ab. (182436)

5 (2 or 3) and 4 (29727)

6 exp stent/ (69452)

7 stent$.ti,ab. (66430)

8 6 or 7 (82298)

9 (1 or 5) and 8 (2362)

10 random$.ti,ab. (647339)

11 factorial$.ti,ab. (16869)

12 (crossover$ or cross over$ or cross‐over$).ti,ab. (56042)

13 placebo$.ti,ab. (158554)

14 (doubl$ adj blind$).ti,ab. (117444)

15 (singl$ adj blind$).ti,ab. (10980)

16 assign$.ti,ab. (182087)

17 allocat$.ti,ab. (60848)

18 volunteer$.ti,ab. (143624)

19 CROSSOVER PROCEDURE/ (30553)

20 DOUBLE‐BLIND METHOD/ (100257)

21 RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIALS/ (7021)

22 SINGLE‐BLIND METHOD/ (14015)

23 or/10‐22 (1035236)

24 9 and 23 (116)

Database: Embase <1974 to 2011 September 16>

Search Strategy:

‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐

1 aorta coarctation/ (9221)

2 exp aorta/ (86796)

3 (aorta or aortic).ti,ab. (204925)

4 (constrict$ or stricture? or steno$ or coarctat$).ti,ab. (195252)

5 (2 or 3) and 4 (32005)

6 exp stent/ (69530)

7 stent$.ti,ab. (66725)

8 6 or 7 (82599)

9 (1 or 5) and 8 (2370)

10 random$.ti,ab. (660403)

11 factorial$.ti,ab. (17430)

12 (crossover$ or cross over$ or cross‐over$).ti,ab. (58502)

13 placebo$.ti,ab. (164173)

14 (doubl$ adj blind$).ti,ab. (124033)

15 (singl$ adj blind$).ti,ab. (11263)

16 assign$.ti,ab. (186480)

17 allocat$.ti,ab. (62514)

18 volunteer$.ti,ab. (150056)

19 CROSSOVER PROCEDURE/ (30564)

20 DOUBLE‐BLIND METHOD/ (102752)

21 RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIALS/ (7088)

22 SINGLE‐BLIND METHOD/ (14018)

23 or/10‐22 (1068271)

24 9 and 23 (116)

Database: Embase Classic <1947 to 1973>

Search Strategy:

‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐

1 aorta coarctation/ (889)

2 exp aorta/ (19127)

3 (aorta or aortic).ti,ab. (25600)

4 (constrict$ or stricture? or steno$ or coarctat$).ti,ab. (31335)

5 (2 or 3) and 4 (6102)

6 exp stent/ (138)

7 stent$.ti,ab. (202)

8 6 or 7 (204)

9 (1 or 5) and 8 (3)

Appendix 4. AMED search

Database: AMED (Allied and Complementary Medicine) <1985 to September 2011>

Search Strategy:

‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐

1 exp aorta/ (95)

2 (aorta or aortic).ti,ab. (419)

3 (constrict$ or stricture? or steno$ or coarctat$).ti,ab. (622)

4 (1 or 2) and 3 (25)

5 exp stent/ (174)

6 stent$.ti,ab. (293)

7 5 or 6 (298)

8 4 and 7 (1)

Appendix 5. CINAHL search

| 19/9/2011 | Query | Results |

| S11 | S7 and S10 | 151 |

| S10 | S8 or S9 | 9728 |

| S9 | TI stent* OR AB stent* | 7336 |

| S8 | MH stents | 7478 |

| S7 | S1 or S6 | 1779 |

| S6 | S4 and S5 | 1635 |

| S5 | TI ( (constrict* or strictur* or steno* or coarctat*) ) OR AB ( (constrict* or strictur* or steno* or coarctat*) ) |

9430 |

| S4 | S2 OR S3 | 10739 |

| S3 | TI ( (aorta or aortic) ) OR AB ( (aorta or aortic) ) | 10152 |

| S2 | MH aorta | 1998 |

| S1 | MH Aortic Coarctation | 401 |

Appendix 6. Web of Science search

Date of search 20.9.2011

Title=(coarctation) AND Title=(aort*) AND Title=(stent*) = 204

Appendix 7. LILACS search

iAH Search interface ‐ ListBIREME/PAHO/WHO ‐ Virtual Health Library Date of search 30.9.2011 Database : LILACS Search on : Aorta OR Aortic [Words] and coarctation OR COARCTACAO [Words] and stent OR surgery OR CIRURGIA [Words] Total of references : 125

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Carr 2006 | Literature review of English language articles related to the treatment of adult and adolescent with CoA between 1995 to 2005 found in the on‐line databases of MEDLINE and PubMed. |

| Cowley 2005 | Prospective, randomized clinical trial with initially 36 patients, comparing open surgery (10/36) and balloon angioplasty without stent placement (11/36) for unoperated CoA in long follow‐up (between 11.3 ± 3.7 years for surgical subjects and 10.6 ± 4.7 years for balloon angioplasty subjects). |

| Egan 2009 | Critical literature review of retrospective institutional series and comparative prospective studies about management of CoA comparing stent placement, balloon angioplasty and open surgery. |

| Hernandez‐Gonzalez 2003 | A clinical, randomized, multicenter trial with 58 pediatric patients (1 to 16 years) comparing open surgery (28/58) and balloon angioplasty without stent placement (30/58) for congenital aortic coarctation in short follow‐up (average of 221 days for surgery subjects and 196 days for balloon angioplasty subjects) |

| Shaddy 1993 | Prospective, randomized clinical trial with 36 patients, comparing open surgery (16/36) and balloon angioplasty without stent placement (20/36) for unoperated CoA in short follow‐up (between 18.7 ± 15.1 months and 18.0 ± 8.7 months). |

Differences between protocol and review

We broadened the secondary outcome 'other cardiovascular complications' to 'other complications (cardiovascular: stroke, peripheral emboli and access artery injury; technical complications: stent migration, balloon rupture, suture dehiscence, paraplegia etc) to consider the potential effect of technical as well as cardiovascular complications.

Contributions of authors

Padua LMS wrote the protocol and the review, selected which studies to include, obtained copies of studies, will update the review. Garcia LC wrote the protocol and the review, selected which studies to include, obtained copies of studies. Carvalho PE wrote the protocol and review, will update the review. Rubira CJ wrote the protocol and review, developed and ran the search strategy.

Sources of support

Internal sources

FAPESP ‐ Fundaçâo de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo, Brazil.

FAMEMA ‐ Marília Medical School, Brazil.

External sources

-

Chief Scientist Office, Scottish Government Health Directorates, The Scottish Government, UK.

The PVD Group editorial base is supported by the Chief Scientist Office.

Declarations of interest

None known

New

References

References to studies excluded from this review

Carr 2006 {published data only}

- Carr JA. The results of catheter‐based therapy compared with surgical repair of adult aortic coarctation. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2006;47(6):1101‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cowley 2005 {published data only}

- Cowley CG, Orsmond GS, Feola P, McQuillan L, Shaddy RE. Long‐term, randomized comparison of balloon angioplasty and surgery for native coarctation of the aorta in childhood. Circulation 2005;111(25):3453‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Egan 2009 {published data only}

- Egan M, Holzer RJ. Comparing balloon angioplasty, stenting and surgery in the treatment of aortic coarctation. Expert Review of Cardiovascular Therapy 2009;7(11):1401‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hernandez‐Gonzalez 2003 {published data only}

- Hernandez‐Gonzalez M, Solorio S, Conde‐Carmona I, Rangel‐Abundis A, Ledesma M, Munayer J, et al. Intraluminal aortoplasty vs. surgical aortic resection in congenital aortic coarctation. A clinical random study in pediatric patients. Archives of Medical Research 2003;34(4):305‐10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Shaddy 1993 {published data only}

- Shaddy RE, Boucek MM, Sturtevant JE, Ruttenberg HD, Jaffe RB, Tani LY, et al. Comparison of angioplasty and surgery for unoperated coarctation of the aorta. Circulation 1993;87(3):793‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Backer 1998

- Backer CL, Mavroudis C, Zias EA, Amin Z, Weigel TJ. Repair of coarctation with resection and extended end‐to‐end anastomosis. Annals of Thoracic Surgery 1998;66(4):1365‐70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Baylis 1956

- Baylis JH, Campbell M. The course and prognosis of coarctation of the aorta. British Heart Journal 1956;18(4):475‐95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Becker 1970

- Becker AE, Becker MJ, Edwards JE. Anomalies associated with coarctation of aorta: particular reference to infancy. Circulation 1970;41(6):1067‐75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bulbul 1996

- Bulbul ZR, Bruckheimer E, Love JC, Fahey JT, Hellenbrand WE. Implantation of balloon‐expandable stents for coarctation of the aorta: implantation data and short‐term results. Catheterization and Cardiovascular Diagnosis 1996;39(1):36‐42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Campbell 1970

- Campbell M. Natural history of coarctation of the aorta. British Heart Journal 1970;32(5):633‐40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cobanoglu 1998

- Cobanoglu A, Thyagarajan GK, Dobbs JL. Surgery for coarctation of the aorta in infants younger than 3 months: end‐to‐end repair versus subclavian flap angioplasty: is either operation better?. European Journal of Cardio‐Thoracic Surgery 1998;14(1):19‐26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cohen 1989

- Cohen M, Fuster V, Steele PM, Driscoll D, McGoon DC. Coarctation of the aorta: long‐term follow‐up and prediction of outcome after surgical correction. Circulation 1989;80(4):840‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Corno 2001

- Corno AF, Botta U, Hurni M, Payot M, Sekarski N, Tozzi P, et al. Surgery for aortic coarctation: a 30 years experience. European Journal of Cardio‐Thoracic Surgery 2001;20(6):1202‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Crafoord 1945

- Crafoord C, Nylin G. Congenital coarctation of the aorta and its surgical treatment. Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery 1945;14:347‐61. [Google Scholar]

Deeks 2008

- Deeks JJ, Higgins JPT, Altman DG. Chapter 9: Analysing data and undertaking meta‐analyses. In: Higgins JPT, Green S editor(s). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Chicester: John Wiley & Sons, 2008:243‐96. [Google Scholar]

Eapen 1998

- Eapen RS, Rowland DG, Franklin WH. Effect of prenatal diagnosis of critical left heart obstruction on perinatal morbidity and mortality. American Journal of Perinatology 1998;15(4):237‐42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ebeid 1997

- Ebeid MR, Prieto LR, Latson LA. Use of balloon expandable stents for coarctation of the aorta: initial results and intermediate‐term follow‐up. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 1997;30(7):1847‐52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Franklin 2002

- Franklin O, Burch M, Manning N, Sleeman K, Gould S, Archer N. Prenatal diagnosis of coarctation of the aorta improves survival and reduces morbidity. Heart 2002;87(1):67‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gibbon 1969

- Gibbon JH, Sabiston DC, Spencer FC. Surgery of the Chest. 2nd Edition. Philadelphia: WB. Saunders & Co, 1969. [Google Scholar]

Golden 2007

- Golden AB, Hellenbrand WE. Coarctation of the aorta: stenting in children and adults. Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions 2007;69(2):289‐99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gross 1945

- Gross RE, Hufnagel CA. Coarctation of the aorta ‐ Experimental studies regarding its surgical correction. New England Journal of Medicine 1945;233:287‐93. [Google Scholar]

Hamdan 2001

- Hamdan MA, Maheshwari S, Fahey JT, Hellenbrand WE. Endovascular stents for coarctation of the aorta: initial results and intermediate‐term follow‐up. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2001;38(5):1518‐23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Harrrison 2001

- Harrison DA, McLaughlin PR, Lazzam C, Connelly M, Benson LN. Endovascular stents in the management of coarctation of the aorta in the adolescent and adult: one year follow up. Heart 2001;85(5):561‐6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2003

- Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta‐analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557‐60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2011

- Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

Jenkins 1999

- Jenkins NP, Ward C. Coarctation of the aorta: natural history and outcome after surgical treatment. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine 1999;92(7):365‐71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kuehl 1999

- Kuehl KS, Loffredo CA, Ferencz C. Failure to diagnose congenital heart disease in infancy. Pediatrics 1999;103(4):743‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lau 2006

- Lau J, Ioannidis JPA, Terrin N, Schmid CH, Olkin I. The case of the misleading funnel plot. BMJ 2006;333(7):597‐600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lerberg 1982

- Lerberg DB, Hardesty RL, Siewers RD, Zuberbuhler JR, Bahnson HT. Coarctation of the aorta in infants and children: 25 years of experience. Annals of Thoracic Surgery 1982;33(2):159‐70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lock 1983

- Lock JE, Bass JL, Amplatz K, Fuhrman BP, Castaneda‐Zuniga W. Balloon dilation angioplasty of aortic coarctations in infants and children. Circulation 1983;68(1):109‐16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mitchell 1971

- Mitchell SC, Korones SB, Berendes HW. Congenital heart disease in 56,109 births: Incidence and natural history. Circulation 1971;43(3):323‐32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mullen 2003

- Mullen MJ. Coarctation of the aorta in adults: do we need surgeons?. Heart 2003;89(1):3‐5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Nielsen 2005

- Nielsen JC, Powell AJ, Gauvreau K, Marcus EN, Prakash A, Geva T. Magnetic resonance imaging predictors of coarctation severity. Circulation 2005;111(5):622‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

O'Rourke 1989

- O'Rourke K, Detsky AS. Meta‐analysis in medical research: strong encouragement for higher quality in individual research efforts. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 1989;42(10):1021‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

O'Sullivan 2002

- O'Sullivan JJ, Derrick G, Darnell R. Prevalence of hypertension in children after early repair of coarctation of the aorta: a cohort study using casual and 24 hour blood pressure measurement. Heart 2002;88(2):163‐6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ou 2004

- Ou P, Bonnet D, Auriacombe L, Pedroni E, Balleux F, Sidi D, et al. Late systemic hypertension and aortic arch geometry after successful repair of coarctation of the aorta. European Heart Journal 2004;25(20):1853‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

PRISMA 2009

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine 2009;6(7):e1000097. [DOI: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Qureshi 2005

- Qureshi SA, Sivasankaran S. Role of stents in congenital heart disease. Expert Review of Cardiovascular Therapy 2005;3(2):261‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ramnarine 2005

- Ramnarine I. Role of surgery in the management of the adult patient with coarctation of the aorta. Postgraduate Medical Journal 2005;81(954):243‐7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rosenthal 2005

- Rosenthal E. Coarctation of the aorta from fetus to adult: curable condition or life long disease process?. Heart 2005;91(11):1495‐502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sterne 2002

- Sterne JA, Juni P, Schulz KF, Altman DG, Bartlett C, Egger M. Statistical methods for assessing the influence of study characteristics on treatment effects in "meta‐epidemiological" research. Statistics in Medicine 2002;21(11):1513‐24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sterne 2008

- Sterne JAC, Egger M, Moher D. Chapter 10: Addressing reporting biases. In: Higgins JPT, Green S editor(s). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2008:297‐334. [Google Scholar]

Suarez de Lezo 1995

- Suarez de Lezo J, Pan M, Romero M, Medina A, Segura J, Pavlovic D, et al. Balloon‐expandable stent repair of severe coarctation of aorta. American Heart Journal 1995;129(5):1002‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Suarez de Lezo 1999

- Suarez de Lezo J, Pan M, Romero M, Medina A, Segura J, Lafuente M, et al. Immediate and follow‐up findings after stent treatment for severe coarctation of aorta. American Journal of Cardiology 1999;83(3):400‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Thanopoulos 2000

- Thanopoulos BD, Hadjinikolaou L, Konstadopoulou GN, Tsaousis GS, Triposkiadis F, Spirou P. Stent treatment for coarctation of the aorta: intermediate term follow up and technical considerations. Heart 2000;84(1):65‐70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tzifa 2007

- Tzifa A. Management of aortic coarctation in adults: endovascular versus surgical therapy. Hellenic Journal of Cardiology 2007;48(5):290‐5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Walhout 2003

- Walhout RJ, Lekkerkerker JC, Oron GH, Hitchcock FJ, Meijboom EJ, Bennink GB. Comparison of polytetrafluoroethylene patch aortoplasty and end‐to‐end anastomosis for coarctation of the aorta. Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery 2003;126(2):521‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wren 2008

- Wren C, Reinhardt Z, Khawaja K. Twenty‐year trends in diagnosis of life‐threatening neonatal cardiovascular malformations. Archives of Disease in Childhood ‐ Fetal and Neonatal Edition 2008;93(1):F33‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]