Abstract

BACKGROUND

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection exhibits a familial clustering phenomenon.

AIM

To investigate the prevalence of H. pylori infection, identify associated factors, and analyze patterns of transmission within families residing in the community.

METHODS

From July 2021 to September 2021, a total of 191 families (519 people) in two randomly chosen community health service centers in the Chengguan District of Lanzhou in Gansu Province, were recruited to fill out questionnaires and tested for H. pylori infection. Individuals were followed up again from April 2023 and June 2023 to test for H. pylori infection. The relationship between variables and H. pylori infection was analyzed using logistic regression and generalized linear mixed models.

RESULTS

In 2021, the individual-based H. pylori infection rate was found to be 47.0% (244/519), which decreased to 38.1% (177/464) in 2023. Additionally, the rate of individual-based H. pylori new infection was 22.8% (55/241). The family-based H. pylori infection rate in 2021 was 76.9% (147/191), which decreased to 67.1% (116/173) in 2023, and the rate of family-based H. pylori new infection was 38.6% (17/44). Individual H. pylori infection was positively correlated with age, body mass index (BMI), eating food that was excessively hot, frequent acid reflux, bloating, and halitosis symptoms, and negatively correlated with family size and nut consumption. New individual H. pylori infection was positively correlated with BMI, other types of family structures, drinking purified water, and frequent heartburn symptoms, while negatively correlated with the use of refrigerators and following a regular eating schedule. A larger living area was an independent protective factor for H. pylori infection in households. Frequently consuming excessively hot food and symptoms of halitosis were independent risk factors for H. pylori infection in individuals; frequent consumption of nuts was an independent protective factor for H. pylori infection. Other types of family structure, drinking purified water, and frequent heartburn symptoms were independent risk factors for new individual H. pylori infection; the use of a refrigerator was an independent protective factor for new H. pylori infections.

CONCLUSION

The household H. pylori infection rate in Lanzhou is relatively high and linked to socio-demographic factors and lifestyles. Eradication efforts and control of related risk factors are recommended in the general population.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, Household, China, Prevalence, Risk factors

Core Tip: Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is characterized by family cluster infection. However, studies investigating the status of H. pylori infection and patterns of intra-household transmission are scarce. In our study, the individual H. pylori infection rate in the Chengguan District of Lanzhou was found to have decreased from 47.0% in 2021 to 38.1% in 2023. The rate of new individual infection is currently 22.8%. Similarly, the proportion of households with at least one infected member has decreased from 76.9% in 2021 to 67.1% in 2023. These results suggest that family-based prevention and treatment are more conducive to the management of H. pylori.

INTRODUCTION

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a spiral-shaped gram-negative bacterium. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis found that the estimated global prevalence of H. pylori infection decreased from 58.2% in the 1980-1990 period to 43.1% in the 2011-2022 period[1]. Although the prevalence of H. pylori infection in China is high, most patients do not present with obvious symptoms or complications. However, almost all H. pylori-infected individuals undergo inflammatory changes in their gastric mucosa 25%-30% of cases develop a variety of gastrointestinal and extra-gastrointestinal disorders[2-4]. Studies on familial H. pylori clustering infections have increased in recent years. In a large-scale study of H. pylori in 29 provinces in mainland China in 2021, 10735 families (31098 individuals) were included, and the average individual-based H. pylori infection rate was 40.66%. Among these, 43.45% were adults and 20.55% were children and adolescents. The average family-based infection rate was 71.21%. The rate of familial H. pylori infection is much higher than that of individuals, and the infection rates are higher in northwest China[5]. Zhang et al[6] found that the use of a family-based strategy to screen for H. pylori infections exhibited an improvement of 4.02% in the ability to detect infection. This approach is a cost-effective strategy that enables an optimized allocation of screening resources[7].

Several studies have shown that H. pylori is mainly transmitted through oral-oral and fecal-oral contact, as well as through water sources[8,9]. Infection is also caused by close contact with H. pylori-positive family members[10,11]. This may explain persistent, recurrence and reinfection of H. pylori. Parents, especially mothers, infected with H. pylori, have been found to play a crucial role in transmitting the bacteria to their children[12,13]. The infection rate of H. pylori in children significantly increases with an increase in the parental infection rate[14]. Although a Japanese study initially showed support for this, it also highlighted the importance of mother-to-child transmission, making it difficult to clarify the spread of H. pylori in these families[15]. The transmission of H. pylori is also evident between spouses and among siblings. Studies on H. pylori infection in spouses have highlighted a degree of consistency in infection among spouses, wherein one spouse’s infection could increase the other’s risk of becoming infected[16]. As the duration of marriage increases, the infection rate of H. pylori in spouses has also been found to increase significantly, indicative of potential cross-infection between couples[17]. In a previous study conducted in Spain, a remarkably high consistency of H. pylori transmission among siblings was observed, further confirming that sibling-to-sibling transmission is a route of H. pylori infection in children. Additionally, living with non-siblings in extended families may increase the risk of infection, but only in families where H. pylori infection is prevalent in all family groups[18]. Therefore, familial clustering and the high prevalence of H. pylori are among the most important reasons for the failure of H. pylori treatment. This is because it can lead to transmission among family members during the treatment process and increase the recurrence rate of H. pylori in patients after eradication.

Previous large clinical studies and guideline consensus recommend tests and treatments, as well as screening and treatment strategies for the individual-based management of H. pylori infection in various infected populations[2-4,19]. Due to the familial clustering of H. pylori infections, whole-family H. pylori infection control and management is clinically significant for the prevention of related diseases[20]. In China, a newly proposed strategy of family-based H. pylori infection control and management provides an advanced clinical approach for controlling the intrafamilial transmission and infection of H. pylori[8,17]. However, relatively few studies have investigated the status of family-based infections, associated factors, and patterns of intrafamilial transmission in the general population.

In this study, a cross-sectional comparison of infections before and after 20 months was conducted to evaluate household infections, risk factors, and transmission routes of H. pylori in families in the community of Lanzhou, in northwest China. We also assessed the willingness of H. pylori-infected individuals to undergo co-treatment with their entire family and conducted post-treatment follow-up. This study provides empirical evidence relating to familial H. pylori infection and contributes to the development of improved strategies for family co-treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population and design

This family-based survey was conducted in the Chengguan District of Lanzhou in Gansu Province, China from July 2021 to September 2021. After considering factors such as area, water source, cost, accessibility, testing facilities, and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), we randomly selected the Zhangye Road Guangwumen Community Health Service Center and the Yanchang Road Caochang Street Community Health Service Center from which to recruit volunteers by distributing introductory brochures or information booklet for this study and posting posters at community health service centers to inform residents of the risk of H. pylori infection and the need for eradication treatment. We offered free testing to those who volunteered to participate on a family basis, without any incentives. At the research site, our experienced doctors provided relevant consultation services. Community workers were responsible for helping to recruit community family members for onsite registration.

Participants included in the study were defined as individuals who had resided in the same household for a period exceeding 10 months within the past five years. The exclusion criteria encompassed the use of medications, including antibiotics, herbal medicines with antimicrobial properties, proton pump inhibitors, bismuth, probiotics, and other pharmaceuticals that could potentially impact the outcomes of the test if consumed within the preceding four weeks. In total, 519 individuals from 191 households (family size ≥ 2 persons) participated in the complete survey. All members of the included households participated, carefully fulfilling the H. pylori testing and completing the relevant questionnaire. After the completion of initial testing, the active intent-to-treat population was provided with a first-line bismuth-containing quadruple regimen for H. pylori eradication, and followed up again from April and June 2023 to test for H. pylori infection. However, due to the global COVID-19 pandemic since 2019, the treatment population has been unable to undergo timely follow-up examinations.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Hospital of Lanzhou University (No. LDYYLL2021-146), and all participants provided written informed consent. For participants who were minors, written informed consent was obtained from a legal guardian.

Questionnaires for family members

Our questionnaire was rigorously designed based on the existing literature. Before initiating the study, we conducted a small-scale pilot experiment to ensure that participants could understand the reliability and accuracy of the questions and answers. For each eligible household, all members were asked to complete a questionnaire online or on-site. Well-trained physicians and community workers were on hand to guide and help individuals with the registration process and the filling out of the questionnaires. All participants were informed that their information would be treated as confidential and only used for statistical analysis. Community workers at the health centers with knowledge of the families assisted in checking the questionnaires to avoid the inclusion of careless answers. According to the purpose of this study, the questionnaire included the following items: (1) General information (e.g. age, gender, body mass index (BMI), the number of family members, occupation, marital status, income, and housing areas); (2) Family hygiene and living habits; (3) Dietary habits; (4) Exercise and sleep status; (5) Chronic diseases; (6) Gastrointestinal symptoms; and (7) Family history of gastrointestinal diseases.

H. pylori testing for all family members

According to the manufacturer's instructions, a specially trained clinical physician or laboratory technician used the 13C-urea breath test (UBT) reagent kit to evaluate all participating family members for H. pylori infection. All study participants were tested in the morning after fasting for at least 6 hours. After collecting an initial breath sample with the sample collection container bag during normal respiration, the participants were orally administered 80 mL of a pre-prepared orange juice-flavored solution containing 50 mg of 13C-urea. Thirty minutes later, a second breath sample was collected. We analyzed the samples using a 13C breath detector (Guangzhou Huayou Mingkang Optoelectronics Technology Co., Ltd., China). A delta over baseline ≥ 4.0‰ was considered positive for H. pylori, and a delta over baseline < 4.0‰ was considered negative. An infected household was defined as a household with at least one H. pylori-infected family member. The definition of a new infection of H. pylori was that of an individual who was not infected in 2021 but was infected in 2023. The definition of new infected households was that of families where all family members were negative in 2021 and at least one positive member was infected in 2023. All tests were conducted in adherence to the manufacturer's instructions, with calibration and verification completed using samples of known gas concentrations supplied by the analyzer manufacturer before the start of the study.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted with Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 27.0.1. Categorical data were presented as frequencies and percentages. Univariate logistic regression analysis was used to examine the correlation between the study variables and H. pylori infection. When analyzing at the family level, a binary logistic regression model was used due to the independence between families. At the individual level, a generalized linear mixed model was utilized to account for the nested nature of individuals within households in the collected data. Variables with statistical significance in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate logistic regression and generalized linear mixed models to investigate the association between risk factors and H. pylori infection. The results indicated odds ratios (OR) and 95%CI. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

General information on enrolled families and individuals

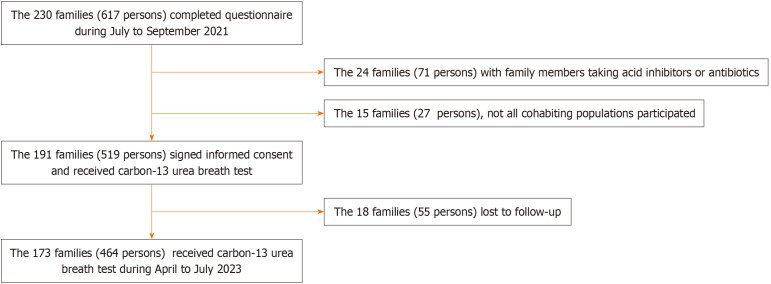

Details of family enrollment are provided in Figure 1. A total of 519 individuals from 191 families signed informed consent and received 13C-UBT testing for analysis of prevalence and risk factors. In 2023, 18 families (55 individuals) were lost to follow-up testing, and 173 families (464 individuals) completed the 13C-UBT.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of household and individual enrolment processes. An infected household is defined as a household with at least one Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infected family member. The new infection of H. pylori occurred in individuals who were not infected in 2021 but were infected in 2023.

The average age of the 519 individuals in 2021 was 45.3 years. Of these individuals, 222 (42.8%) were male, 297 (57.2%) were female, 404 (77.8%) were married, and 55 (10.6%) were children and adolescents. The average family size of the 191 participating families was 3.0 persons. A total of 173 families (464 individuals) followed up in 2023, comprising 194 (41.8%) males, 270 (58.1%) females, and 49 (10.5%) children and adolescents (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic information and Helicobacter pylori infection status of enrolled individuals, n (%)

|

Variables

|

H. pylori-infected1

|

H. pylori uninfected

|

a

P value

|

New H. pylori-infected2

|

New H. pylori uninfected

|

b

P value

|

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 105 (47.3) | 117 (52.7) | 18 (18.0) | 82 (82.0) | ||

| Male | 139 (46.8) | 158 (53.2) | 0.829 | 37 (26.2) | 104 (73.8) | 0.100 |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| ≤ 18 | 14 (25.5) | 41 (74.5) | 5 (13.5) | 32 (86.5) | ||

| ≤ 39 | 79 (46.2) | 92 (53.8) | 0.010 | 19 (23.5) | 62 (76.5) | 0.251 |

| ≤ 59 | 77 (49.0) | 80 (51.0) | 0.004 | 18 (25.0) | 54 (75.0) | 0.167 |

| ≥ 60 | 74 (54.4) | 62 (45.6) | 0.001 | 13 (25.5) | 38 (74.5) | 0.233 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | ||||||

| < 18.5 | 15 (29.4) | 36 (70.6) | 3 (9.1) | 30 (90.0) | ||

| 18.5-23.9 | 132 (46.6) | 151 (53.4) | 0.034 | 30 (23.3) | 99 (76.7) | 0.105 |

| 24-27.9 | 76 (50.7) | 74 (49.3) | 0.017 | 18 (26.9) | 49 (73.1) | 0.048 |

| > 28 | 21 (60.0) | 14 (40.0) | 0.011 | 4 (33.3) | 8 (66.7) | 0.117 |

| Nationality | ||||||

| The Han nationality | 238 (46.9) | 269 (53.1) | 49 (20.0) | 186 (79.1) | ||

| Others | 6 (50.0) | 6 (50.0) | 0.721 | 6 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.986 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Unmarried | 46 (40.0) | 69 (60.0) | 11 (17.7) | 51 (82.3) | ||

| Married | 198 (49.0) | 206 (51.0) | 0.127 | 44 (24.6) | 135 (75.4) | 0.248 |

| Education level | ||||||

| Junior high school and below | 65 (47.1) | 73 (52.9) | 16 (24.6) | 49 (75.4) | ||

| High school or technical school | 59 (47.2) | 66 (52.8) | 0.994 | 14 (25.0) | 42 (75.0) | 0.757 |

| Junior college | 59 (47.2) | 66 (52.8) | 0.790 | 15 (25.4) | 44 (74.6) | 0.977 |

| College and above | 61 (46.6) | 70 (53.4) | 0.975 | 10 (16.4) | 51 (83.6) | 0.295 |

| Occupation | ||||||

| Blue collar | 46 (43.8) | 59 (56.2) | 18 (32.7) | 37 (67.3) | ||

| White collar | 78 (45.3) | 94 (54.7) | 0.765 | 15 (19.2) | 63 (80.8) | 0.116 |

| Student | 14 (26.9) | 38 (73.1) | 0.057 | 4 (11.8) | 30 (88.2) | 0.057 |

| Unemployed people | 106 (55.8) | 84 (44.2) | 0.069 | 18 (24.3) | 56 (75.7) | 0.494 |

| Family size | ||||||

| 2 | 103 (54.8) | 85 (45.2) | 14 (17.7) | 65 (82.3) | ||

| 3 | 82 (42.7) | 110 (57.3) | 0.035 | 18 (18.8) | 78 (81.3) | 0.952 |

| Four and above | 59 (42.4) | 80 (57.6) | 0.049 | 23 (34.8) | 43 (65.2) | 0.088 |

| Family structure3 | ||||||

| Couple's family | 62 (54.4) | 52 (45.6) | 5 (10.4) | 43 (89.6) | ||

| Nuclear family | 35 (40.2) | 52 (59.8) | 0.081 | 6 (13.6) | 38 (86.4) | 0.795 |

| Immediate family | 51 (45.5) | 61 (54.5) | 0.243 | 12 (25.5) | 35 (74.5) | 0.149 |

| United States family | 34 (47.9) | 37 (52.1) | 0.433 | 10 (28.6) | 25 (71.4) | 0.109 |

| Others | 62 (45.9) | 73 (54.1) | 0.270 | 22 (32.8) | 45 (67.2) | 0.022 |

| Household income (renminbi) | ||||||

| < 10000 | 62 (48.1) | 67 (51.9) | 9 (15.5) | 49 (84.5) | ||

| 10000-30000 | 78 (52.0) | 72 (48.0) | 0.569 | 19 (29.7) | 45 (70.3) | 0.158 |

| > 30000 | 104 (43.3) | 136 (56.7) | 0.466 | 27 (22.7) | 92 (77.3) | 0.567 |

| Annual household living area (m2) | ||||||

| ≤ 30 | 51 (46.4) | 59 (53.6) | 8 (15.1) | 45 (84.9) | ||

| 30-60 | 88 (47.6) | 97 (52.4) | 0.810 | 18 (20.7) | 69 (79.3) | 0.422 |

| ≥ 60 | 105 (46.9) | 119 (53.1) | 0.822 | 29 (28.7) | 72 (71.3) | 0.092 |

P value was calculated by univariate logistic regression of the infected individuals, P < 0.05 indicates that infection risk increased/decreased significantly compared with the reference groups.

P value was calculated by univariate logistic regression of the new infected individuals, P < 0.05 indicates that new infection risk increased/decreased significantly compared with the reference groups.

H. pylori-infected: Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori)-infected individuals were infected in 2021.

New H. pylori-infected: New H. pylori-infected individuals were not infected in 2021 but were infected in 2023.

Family structure refers to the relationships between the family members who make up the family. The couple's family is composed of only two individuals: A husband and a wife. The nuclear family is a family composed of parents and unmarried children. Immediate family is a family consisting of two or more generations of married couples, with no more than one couple per generation and no intergenerational gap between them. A United States family refers to a family in which any generation contains two or more couples. Others include single-parent families, intergenerational families, cohabiting families, homosexual families, and single families.

H. pylori: Helicobacter pylori.

Household H. pylori infection status and risk factors

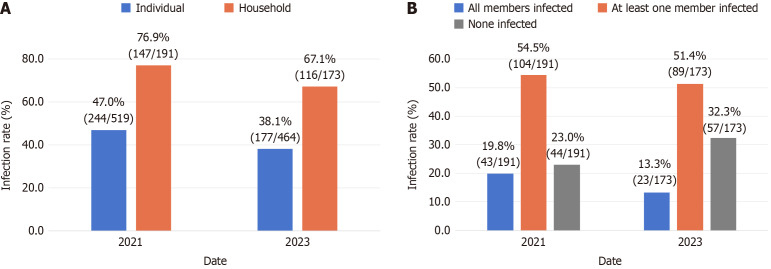

The family-based H. pylori infection rate in 2021 was 76.9% (147/191). All members were infected in 19.8% (43/191) of the enrolled families, in 54.5% (104/191) of the families at least one member was infected, and in 23.0% (44/191), there were no infections. The family-based infection rate in 2023 was 67.1% (116/173). All members were infected in 13.3% (23/173) of the enrolled families. In 51.4% (89/173) of the families, at least one member was infected, and in 32.3% (57/173) of the families, there were no infections (Figure 2A-B).

Figure 2.

Individual and household Helicobacter pylori infection rates. A: Individual and household Helicobacter pylori infection rates in 2021 and 2023; B: Proportion of households with different numbers of infected family members.

Information on the infection and risk factors of the family members in the 191 registered households is provided in Table 2. A larger living area (e.g., sixty and above: OR: 0.10, 95%CI: 0.01-0.77) was an independent protective factor for household infections (P < 0.05). Other factors in this study did not affect the risk of household infections (P > 0.05), including family size and structure, annual household income level, household hygiene, eating habits, and the sharing of cups, dental implements, towels, dishes, and drinking sources.

Table 2.

Household Helicobacter pylori infection status and risk factors, n (%)

|

Variables

|

Infected household (147)1

|

Uninfected household (44)2

|

Crude OR

|

95%CI

|

a

P value

|

Adjusted OR

|

95%CI

|

b

P value

|

|

| Family structure3 | |||||||||

| Couple's family | 43 (75.4) | 14 (24.6) | Reference | ||||||

| Nuclear family | 22 (78.6) | 6 (21.4) | 1.19 | 0.40-3.54 | 0.749 | ||||

| Immediate family | 26 (81.3) | 6 (18.8) | 1.41 | 0.48-4.13 | 0.530 | ||||

| United States families | 16 (88.8) | 2 (11.1) | 2.61 | 0.53-12.76 | 0.238 | ||||

| Others | 40 (71.4) | 16 (28.6) | 0.81 | 0.35-1.88 | 0.630 | ||||

| Family size | |||||||||

| 2 | 69 (73.4) | 25 (26.6) | Reference | ||||||

| 3 | 49 (76.6) | 15 (23.4) | 0.38 | 0.12-1.19 | 0.097 | ||||

| Four and above | 29 (87.9) | 4 (12.1) | 0.45 | 0.14-1.49 | 0.191 | ||||

| Household income (renminbi) | |||||||||

| < 10000 | 41 (80.4) | 10 (19.6) | Reference | ||||||

| 10000-30000 | 49 (76.6) | 15 (23.4) | 0.80 | 0.32-1.96 | 0.621 | ||||

| > 30000 | 57 (75.0) | 19 (25.0) | 0.73 | 0.31-1.74 | 0.479 | ||||

| Annual household living area (m2) | |||||||||

| ≤ 30 | 29 (96.7) | 1 (3.3) | Reference | Reference | |||||

| 30-60 | 61 (72.6) | 23 (27.4) | 0.09 | 0.01-0.71 | 0.022 | 0.09 | 0.01-0.71 | 0.022 | |

| ≥ 60 | 57 (74.0) | 20 (26.0) | 0.10 | 0.01-0.77 | 0.027 | 0.10 | 0.01-0.77 | 0.027 | |

| Household hygiene | |||||||||

| Good | 100 (76.3) | 31 (23.7) | Reference | ||||||

| Fair or poor | 47 (78.3) | 13 (21.7) | 1.12 | 0.54-2.34 | 0.761 | ||||

| Eating habits | |||||||||

| Individual dining | 8 (80.0) | 2 (20.0) | Reference | ||||||

| Dish sharing | 83 (73.5) | 30 (26.5) | 0.69 | 0.14-3.44 | 0.653 | ||||

| Both of the above | 56 (82.4) | 12 (17.6) | 1.17 | 0.22-6.20 | 0.856 | ||||

| Use cleaning agents or detergent to clean tableware | |||||||||

| Frequently | 39 (79.6) | 10 (20.4) | Reference | ||||||

| Everyday | 108 (76.1) | 34 (23.9) | 0.81 | 0.37-1.80 | 0.613 | ||||

| Sharing drinking cup | |||||||||

| Rarely | 111 (76.0) | 35 (24.0) | Reference | ||||||

| Frequently | 36 (80.0) | 9 (20.0) | 1.26 | 0.55-2.87 | 0.581 | ||||

| Sharing dental equipment | |||||||||

| Rarely | 135 (77.1) | 40 (22.9) | Reference | ||||||

| Frequently | 12 (75.0) | 4 (25.0) | 0.89 | 0.27-2.91 | 0.846 | ||||

| Sharing towels | |||||||||

| Rarely | 130 (76.5) | 40 (23.5) | Reference | ||||||

| Frequently | 17 (81.0) | 4 (19.0) | 1.31 | 0.42-4.11 | 0.646 | ||||

| Sharing tableware | |||||||||

| Rarely | 69 (73.4) | 25 (26.6) | Reference | ||||||

| Frequently | 78 (80.4) | 19 (19.6) | 1.49 | 0.75-2.93 | 0.252 | ||||

| Source of drinking water | |||||||||

| Tap water | 73 (73.7) | 26 (26.3) | Reference | ||||||

| Purified water | 74 (80.4) | 18 (19.6) | 1.46 | 0.74-2.90 | 0.273 | ||||

| Storage methods for leftover food | |||||||||

| Put it in the fridge | 120 (76.9) | 36 (23.1) | Reference | ||||||

| Room temperature | 17 (81.0) | 4 (19.0) | 1.28 | 0.40-4.03 | 0.679 | ||||

| Throw away | 10 (71.4) | 4 (28.6) | 0.75 | 0.22-2.54 | 0.643 | ||||

P value was calculated by univariate logistic regression, P < 0.05 indicates that infection risk increased/decreased significantly compared with the reference groups.

P value was calculated by multivariate logistic regression and was adjusted with items of P < 0.05 in univariate logistic regression.

Infected household is defined as a household with at least one Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori)-infected family member.

Uninfected household is defined as a household without any H. pylori-infected family member.

Family structure refers to the relationships between the family members who make up the family. The couple's family is composed of only two individuals: A husband and a wife. The nuclear family is a family composed of parents and unmarried children. Immediate family is a family consisting of two or more generations of married couples, with no more than one couple per generation and no intergenerational gap between them. A United States family refers to a family in which any generation contains two or more couples. Others include single-parent families, intergenerational families, cohabiting families, homosexual families, and single families.

OR: Odds ratio; H. pylori: Helicobacter pylori.

Individual-based H. pylori infection status and risk factors

In 2021, the individual-based H. pylori infection rate was found to be 47.0% (244/519), which decreased to 38.1% (177/464) in 2023 (Figure 2A). Initially, the consideration of individuals infected with H. pylori was designated as the dependent variable, and a generalized mixed model was employed to establish a two-level zero model with individuals at level 1 and families at level 2. The findings indicated a significant clustering of H. pylori infection within households (P < 0.05). Age, BMI, family size, eating excessively hot food, consumption of nuts, and having symptoms of acid reflux, bloating, and halitosis were all found to be associated with H. pylori infection in individuals (P < 0.05) (Supplementary Table 1).

In a multivariate analysis, eating excessively hot food daily or often (OR: 2.11, 95%CI: 1.09-4.11) and frequent or occasional symptoms of halitosis (OR: 0.60, 95%CI: 0.39-0.93) were independent risk factors for individual infection (P < 0.05). However, the daily or frequent consumption of nuts (OR: 0.60, 95%CI: 0.39-0.93) was an independent protective factor for individual H. pylori infection (Table 3, P < 0.05).

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis of factors associated with individual-based Helicobacter pylori infection

|

Model

|

Intercept and variables

|

Odds ratio

|

95%CI

|

P value

|

| Fixed effect | Intercept | 0.53 | 0.21-1.35 | 0.184 |

| Age (years) | ||||

| ≤ 18 | Reference | |||

| ≤ 39 | 1.68 | 0.75-3.75 | 0.207 | |

| ≤ 59 | 1.74 | 0.76-4.02 | 0.193 | |

| ≥ 60 | 1.97 | 0.82-4.71 | 0.127 | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | ||||

| < 18.5 | Reference | |||

| 18.5-23.9 | 2.25 | 0.80-6.31 | 0.123 | |

| 24-27.9 | 1.28 | 0.56-2.95 | 0.557 | |

| > 28 | 1.19 | 0.55-2.61 | 0.656 | |

| Family size | ||||

| 2 | Reference | |||

| 3 | 0.69 | 0.43-1.12 | 0.134 | |

| Four and above | 0.64 | 0.37-1.11 | 0.114 | |

| Eating too hot food | ||||

| Never | Reference | |||

| Occasionally | 1.14 | 0.73-1.79 | 0.563 | |

| Every day or often | 2.11 | 1.09-4.11 | 0.027 | |

| Consumption of nuts | ||||

| Never | Reference | |||

| Occasionally | 0.56 | 0.36-0.88 | 0.013 | |

| Every day or often | 0.45 | 0.22-0.92 | 0.03 | |

| Heartburn | ||||

| Never or rarely | Reference | |||

| Often or occasionally | 1.00 | 0.64-1.57 | 0.993 | |

| Abdominal distension | ||||

| Never or rarely | Reference | |||

| Often or occasionally | 1.07 | 0.64-1.80 | 0.791 | |

| Halitosis | ||||

| Never or rarely | Reference | |||

| Often or occasionally | 1.70 | 1.06-2.72 | 0.028 | |

| Random effect | Level 2 | 0.055 | ||

| Level 1 (scale parameters) |

P value was calculated by multivariate analysis utilizing generalized linear mixed models and was adjusted with items of P < 0.05 in univariate logistic regression.

Individual-based H. pylori new infection status and risk factors

The individual-based H. pylori new infection rate was 22.8% (55/241). In the 2023 follow-up, 92 out of 244 individuals infected with H. pylori in 2021 opted for eradication treatment using the bismuth quadruple. BMI, family structure, source of drinking water, use of a refrigerator at home, following a regular eating schedule, and heartburn symptoms were associated with new H. pylori infection (P < 0.05) (Supplementary Table 2).

In a multivariate analysis, family structure (e.g., others: OR: 7.18, 95%CI: 1.83-28.13), source of drinking water (e.g., purified water, OR: 3.08, 95%CI: 1.34-7.10), and frequent or occasional symptoms of heartburn (OR: 3.21, 95%CI: 1.35-7.64) were independent risk factors for new individual H. pylori infection (P < 0.05). However, the use of a refrigerator at home (OR: 0.11, 95%CI: 0.02-0.75) was an independent protective factor for new H. pylori infections (Table 4, P < 0.05).

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis of factors associated with new individual-based Helicobacter pylori infection

|

Model

|

Intercept and variables

|

Odds ratio

|

95%CI

|

P value

|

| Fixed effect | Intercept | 0.13 | 0.01-1.56 | 0.107 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | ||||

| < 18.5 | Reference | |||

| 18.5-23.9 | 2.80 | 0.64-12.27 | 0.171 | |

| 24-27.9 | 4.33 | 0.89-21.06 | 0.069 | |

| > 28 | 6.71 | 0.87-51.80 | 0.068 | |

| Family structure | ||||

| Couple's family | Reference | |||

| Nuclear family | 1.53 | 0.29-7.98 | 0.612 | |

| Immediate family | 3.43 | 0.80-14.71 | 0.097 | |

| United States family | 3.61 | 0.78-16.78 | 0.101 | |

| Others | 7.18 | 1.83-28.13 | 0.005 | |

| Source of drinking water | ||||

| Tap water | Reference | |||

| Purified water | 3.08 | 1.34-7.10 | 0.008 | |

| Using a refrigerator at home | ||||

| No | Reference | |||

| Yes | 0.11 | 0.02-0.75 | 0.025 | |

| Eating regularly and on time | ||||

| Often or occasionally | Reference | |||

| Every day | 0.47 | 0.22-1.02 | 0.056 | |

| Heartburn | ||||

| Never or rarely | Reference | |||

| Often or occasionally | 3.21 | 1.35-7.64 | 0.009 | |

| Random effect | Level 2 | 0.062 | ||

| Level 1 (scale parameters) |

P value was calculated by multivariate analysis utilizing generalized linear mixed models and was adjusted with items of P < 0.05 in univariate logistic regression.

DISCUSSION

Our study investigated the prevalence of H. pylori infection within households and individuals within the community of Lanzhou in Gansu Province, China, for which cross-sectional comparisons were conducted after 20 months. The results revealed that the rate of family-based H. pylori infections was significantly higher than individual-based infections, indicative of the existence of an inter-family of H. pylori infection, possibly due to the high prevalence of H. pylori in the general population and communal dining habits in China. In the present study, the assessment of H. pylori test outcomes before and after a 20-month period revealed a reduction in the prevalence of individual infection from 47.0% (244/519) to 38.1% (177/464), as well as a decrease in the prevalence of household infection from 76.9% (147/191) to 67.1% (116/173). There are several potential explanations for this phenomenon: (1) A shift in poor living and dietary habits among participants following an increased awareness of H. pylori infection through health education; (2) Some infected people voluntarily chose eradication treatment, and although some of them did not undergo eradication treatment for H. pylori infection, they tested negative for 13C-UBT in 2023, potentially due to the widespread antibiotic use during the COVID-19 pandemic[21]; and (3) Due to the limitations of this study’s sample size.

Nevertheless, infected family members were recommended to undergo quadruple treatment. However, a 22.8% rate for new infections was observed in this study, which may be due to the combination of a high incidence of H. pylori infection and communal dining habits in China. In 2021, only 37.3% (92/244) of infected individuals voluntarily received eradication treatment via the bismuth quadruple therapy, and they did not follow up in a timely during the medication period, potentially resulting in insufficient compliance. According to the questionnaire, in families where participants tested positive for H. pylori, fewer of the infected members in these families followed up with treatment together after health education. This was partly because a small percentage of enrolled participants were unable or unwilling to receive treatment. Some infected members of the family selected eradication treatment, while other infected family members were at increased risk of reinfection and recurrence if they did not undergo eradication treatment[22]. These findings highlight the need to provide treatment to all family members who have been infected together.

Sampling for this study was conducted at Community Health Service Centers, which services over 10 communities, and evaluated the impact of different household factors, such as occupation, education levels, and different income levels, on the rates of infection. The results suggested that a larger living area per capita was an independent protective factor for household H. pylori infection. This is in line with previous research that living in crowded living conditions is associated with higher rates of H. pylori infection[9,23]. Nevertheless, factors such as family size and structure, income levels, hygienic conditions, and shared use of living goods were not found to be significantly correlated with household infections. In this study, as individuals began to realize the importance of personal hygiene and living standards in disease prevention, fewer living goods were shared, with the exception of dishes and chopsticks. Previous studies have shown a strong correlation between H. pylori infection in family members and their lifestyle choices, as well as the significance of intra-household transmission of the infection in family members. H. pylori is adapted to live in the stomach and can enter the mouth through the reflux of gastric juice. As a result, H. pylori can be transmitted through the sharing of tableware or cups, or by chewing or tasting children’s food[24]. A study of children in China found that eating in unsterilized conditions, sharing towels, communal meals, maternal chew-feeding, artificial feeding, lack of hand hygiene, overcrowded housing, and a family history of gastrointestinal disease were associated with a significantly increased risk of infection[24]. Some studies have identified low levels of household income and education[5,17], infection in family members, larger family size, and family history of gastric cancer as risk factors for household H. pylori infection[5].

Our findings highlight a noteworthy association between age and H. pylori infection, with a higher prevalence of H. pylori infection observed in individuals over the age of 60 years. This susceptibility in older individuals can be attributed to age-related declines in physiological function, resistance, and immunity. Nevertheless, studies have indicated a decrease in H. pylori infection rates in individuals aged 40-50 years[25,26], possibly due to younger and middle-aged individuals being more likely to come into contact with infected individuals while dining out and socializing. Furthermore, cytokines are essential in combating H. pylori, and variations in immune responses across age groups further influence infection rates[27]. There may be a bi-directional association between BMI and H. pylori infection[28]. Our research revealed a positive association between BMI and the prevalence of H. pylori infection in individuals, with overweight individuals showing a heightened risk of new infections. Previous research has established a positive correlation between H. pylori infection and BMI in developing countries[29-31], while a negative association has been observed in developed nations[32]. This was supported by the significant rise in body weight observed after the successful eradication of H. pylori, which may be attributed to the improvement of gastrointestinal dyspepsia symptoms following the elimination of the infection[33]. The mechanisms underlying the relationship between H. pylori infection and obesity are unclear. There was a suggestion that gastrointestinal hormone regulation may play a role. Individuals infected with H. pylori were found to exhibit decreased serum leptin levels, which can lead to delayed satiety and an increased susceptibility to obesity[34]. An additional potential mechanism contributing to the development of obesity in individuals infected with H. pylori was the observed association with increased insulin resistance[35]. Furthermore, compromised gastrointestinal immune function in individuals with obesity may promote the persistence of H. pylori[36].

Family size and structure were linked to individual H. pylori infections in this study, with infection rates decreasing as the number of family members increased. This contradicts previous findings that larger families have a higher risk of infection[4,5], possibly because many two-person families in this study were couples who were in close contact with each other. Previously, studies have found that couples in which one partner is infected face a heightened risk of infection, and that couples exhibiting symptoms of reflux are more susceptible to infection[37,38]. In this study, other family structures, including sibling, single-parent, or intergenerational families, exhibited a greater susceptibility to new infections compared to husband-and-wife families. This finding contradicted the prevailing notion that households with spouses are more closely contact-transmissible and therefore at higher risk, indicative of a potentially complex pattern underlying the intrafamilial transmission of H. pylori.

A significant correlation was observed between the frequent consumption of excessively hot food and an elevated incidence of infection. This association may be attributed to the irritant effects of hot food on the gastric mucosa, leading to a reduction in gastrointestinal resistance and increased susceptibility to infection. This finding aligns with the outcomes of a multicenter randomized study conducted by Razuka-Ebela et al[39] in Latvia, Eastern Europe. The study involved 1855 participants aged 40-64 years and examined the presence of antibodies for H. pylori. The results indicated that the consumption of excessively hot food or beverages was identified as a risk factor for H. pylori infection (OR: 1.32, 95%CI: 1.03-1.69). We also found that the consumption of nuts was an independent protective factor for H. pylori infection in individuals. In a study conducted by Shu et al[40] on Chinese adults aged 40 years to 59 years, a diet rich in nuts was associated with a reduced prevalence of H. pylori infection. Phytochemicals obtained from nuts have been shown to inhibit H. pylori infection and influence metabolic and gut bacteria[41]. Consequently, the moderate consumption of nuts may help prevent H. pylori infection. Following a regular eating schedule was also found to be an independent protective factor for new individual H. pylori infections. Overeating and irregular prolonged meal times were associated with an increased risk of H. pylori infection[42,43]. These results suggest that eating regular meals, including avoiding oversaturation or excessive hunger, could help to prevent gastric mucosal damage and dysfunction resulting from abnormal gastric acid secretion, thereby reducing the risk of H. pylori infection.

A significant positive association was observed between individuals experiencing frequent symptoms of acid reflux, bloating, and halitosis and H. pylori infection, as well as a positive association between frequent heartburn symptoms and new H. pylori infection. These findings aligned with those of previous studies indicating a link between H. pylori infections and gastrointestinal dysfunction[44]. However, some studies have found that chronic dyspepsia does not predict H. pylori infection[45]. A study even identified a significant negative correlation between frequent symptoms of reflux and the presence of H. pylori antibodies[46]. Thus, halitosis could be a risk factor for H. pylori infection in individuals. In cases of H. pylori infection, there is a notable decrease in pressure in the lower esophagus, leading to the reflux of stomach contents and the subsequent transmission of strains to the oral cavity, resulting in halitosis. However, H. pylori infection was not found to be an independent risk factor for halitosis. Several studies have demonstrated the presence of H. pylori in saliva, the dorsum of the tongue, and dental plaque in the oral cavity of individuals with periodontal disease[47,48].

In summary, the prevalence of household H. pylori infection in families living in Lanzhou is significantly higher than the rate of individual infection. In response to the fact that H. pylori is characterized by familial clustering, in 2021, China proposed measures for the “family-based prevention and control of H. pylori infection” as an important strategy to effectively stop the infection and spread of H. pylori[8]. This is applicable in areas unaffected by the incidence of H. pylori infection and gastric cancer, and in some high-prevalence areas, is economically beneficial, reducing both the social and economic burden[49]. It is extremely important to raise public awareness of H. pylori through lectures on lifestyle and dietary habits. In this respect, the following measures could be taken: (1) Address unhealthy lifestyles, improve personal hygiene (e.g. wash hands before meals), adopt healthy habits (e.g. quit smoking and drinking), and practice physical exercise; (2) Pay attention to dietary habits, avoid consuming high-risk foods and raw foods, do not share chopsticks and spoons, and improve the dietary structure; (3) Monitor screening, especially for previously infected individuals, the family members of infected individuals, and other high-risk groups, such as those with halitosis, periodontal disease, etc.; and (4) H. pylori-infected individuals and their family members should undergo joint eradication treatment, and accurate testing and evaluation should be carried out before eradication. For children and the elderly, accurate testing and a comprehensive evaluation should be mainly based on their age, symptoms, and tolerance level before deciding whether to treat.

This study has several limitations. These include the lack of a timely review post-treatment for H. pylori-infected patients in 2021 and the inability to determine eradication failure or re-infection in individuals with positive 13C-UBT test results in 2023. In addition, although three-quarters of the infected families were willing to receive treatment together, not many families ultimately chose to be co-treated on a family basis, making it difficult to compare the eradication rate of co-treatment between families and individuals. These findings highlight the continued need for health education and the promotion of lifestyle changes. In addition, the small size of the study limits the representation of H. pylori infections in Lanzhou. Furthermore, the absence of bacterial strain culture and DNA data prevented the precise assessment of H. pylori genotypes in infected individuals.

CONCLUSION

In summary, the household H. pylori infection rate in Lanzhou is relatively high and linked to socio-demographic factors and lifestyles. Eradication efforts and control of related risk factors are recommended in the general population.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

we would like to thank the participants for generously dedicating their time to answering the questionnaire and providing test samples.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Hospital of Lanzhou University, No. LDYYLL2021-146.

Informed consent statement: All study participants or their legal guardians provided informed written consent about personal and medical data collection prior to study enrolment.

Conflict-of-interest statement: All authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest in this work.

STROBE statement: The authors have read the STROBE Statement-checklist of items, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the STROBE Statement-checklist of items.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade A, Grade C, Grade C

Novelty: Grade B, Grade B, Grade C

Creativity or Innovation: Grade A, Grade B, Grade C

Scientific Significance: Grade A, Grade B, Grade C

P-Reviewer: Kirkik D; Rao RSP; Vyshka G S-Editor: Luo ML L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zheng XM

Contributor Information

Ju-Kun Zhou, The First Clinical Medical College, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou 730000, Gansu Province, China; Department of Gastroenterology, The First Hospital of Lanzhou University, Lanzhou 730000, Gansu Province, China; Gansu Province Clinical Research Center for Digestive Diseases, The First Hospital of Lanzhou University, Lanzhou 730000, Gansu Province, China.

Ya Zheng, Department of Gastroenterology, The First Hospital of Lanzhou University, Lanzhou 730000, Gansu Province, China; Gansu Province Clinical Research Center for Digestive Diseases, The First Hospital of Lanzhou University, Lanzhou 730000, Gansu Province, China.

Yu-Ping Wang, Department of Gastroenterology, The First Hospital of Lanzhou University, Lanzhou 730000, Gansu Province, China; Gansu Province Clinical Research Center for Digestive Diseases, The First Hospital of Lanzhou University, Lanzhou 730000, Gansu Province, China.

Rui Ji, Department of Gastroenterology, The First Hospital of Lanzhou University, Lanzhou 730000, Gansu Province, China; Gansu Province Clinical Research Center for Digestive Diseases, The First Hospital of Lanzhou University, Lanzhou 730000, Gansu Province, China. jir@lzu.edu.cn.

Data sharing statement

No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Li Y, Choi H, Leung K, Jiang F, Graham DY, Leung WK. Global prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection between 1980 and 2022: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8:553–564. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(23)00070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sugano K, Tack J, Kuipers EJ, Graham DY, El-Omar EM, Miura S, Haruma K, Asaka M, Uemura N, Malfertheiner P faculty members of Kyoto Global Consensus Conference. Kyoto global consensus report on Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Gut. 2015;64:1353–1367. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O'Morain CA, Gisbert JP, Kuipers EJ, Axon AT, Bazzoli F, Gasbarrini A, Atherton J, Graham DY, Hunt R, Moayyedi P, Rokkas T, Rugge M, Selgrad M, Suerbaum S, Sugano K, El-Omar EM European Helicobacter and Microbiota Study Group and Consensus panel. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection-the Maastricht V/Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2017;66:6–30. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang F, Pu K, Wu Z, Zhang Z, Liu X, Chen Z, Ye Y, Wang Y, Zheng Y, Zhang J, An F, Zhao S, Hu X, Li Y, Li Q, Liu M, Lu H, Zhang H, Zhao Y, Yuan H, Ding X, Shu X, Ren Q, Gou X, Hu Z, Wang J, Wang Y, Guan Q, Guo Q, Ji R, Zhou Y. Prevalence and associated risk factors of Helicobacter pylori infection in the Wuwei cohort of north-western China. Trop Med Int Health. 2021;26:290–300. doi: 10.1111/tmi.13517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou XZ, Lyu NH, Zhu HY, Cai QC, Kong XY, Xie P, Zhou LY, Ding SZ, Li ZS, Du YQ National Clinical Research Center for Digestive Diseases (Shanghai), Gastrointestinal Early Cancer Prevention and Treatment Alliance of China (GECA), Helicobacter pylori Study Group of Chinese Society of Gastroenterology and Chinese Alliance for Helicobacter pylori Study. Large-scale, national, family-based epidemiological study on Helicobacter pylori infection in China: the time to change practice for related disease prevention. Gut. 2023;72:855–869. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2022-328965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang J, Deng Y, Liu C, Wang H, Ren H, Chen S, Chen L, Shi B, Zhou L. 'Family-based' strategy for Helicobacter pylori infection screening: an efficient alternative to 'test and treat' strategy. Gut. 2024;73:709–712. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2023-329696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ma Y, Zhou X, Liu Y, Xu S, Ma A, Du Y, Li H. An Economic Evaluation of Family-Based Versus Traditional Helicobacter pylori Screen-and-Treat Strategy: Based on Real-World Data and Microsimulation Model. Helicobacter. 2024;29:e13123. doi: 10.1111/hel.13123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ding SZ, Du YQ, Lu H, Wang WH, Cheng H, Chen SY, Chen MH, Chen WC, Chen Y, Fang JY, Gao HJ, Guo MZ, Han Y, Hou XH, Hu FL, Jiang B, Jiang HX, Lan CH, Li JN, Li Y, Li YQ, Liu J, Li YM, Lyu B, Lu YY, Miao YL, Nie YZ, Qian JM, Sheng JQ, Tang CW, Wang F, Wang HH, Wang JB, Wang JT, Wang JP, Wang XH, Wu KC, Xia XZ, Xie WF, Xie Y, Xu JM, Yang CQ, Yang GB, Yuan Y, Zeng ZR, Zhang BY, Zhang GY, Zhang GX, Zhang JZ, Zhang ZY, Zheng PY, Zhu Y, Zuo XL, Zhou LY, Lyu NH, Yang YS, Li ZS National Clinical Research Center for Digestive Diseases (Shanghai), Gastrointestinal Early Cancer Prevention & Treatment Alliance of China (GECA), Helicobacter pylori Study Group of Chinese Society of Gastroenterology, and Chinese Alliance for Helicobacter pylori Study. Chinese Consensus Report on Family-Based Helicobacter pylori Infection Control and Management (2021 Edition) Gut. 2022;71:238–253. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2021-325630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perry S, de la Luz Sanchez M, Yang S, Haggerty TD, Hurst P, Perez-Perez G, Parsonnet J. Gastroenteritis and transmission of Helicobacter pylori infection in households. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1701–1708. doi: 10.3201/eid1211.060086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kivi M, Tindberg Y, Sörberg M, Casswall TH, Befrits R, Hellström PM, Bengtsson C, Engstrand L, Granström M. Concordance of Helicobacter pylori strains within families. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:5604–5608. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.12.5604-5608.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eusebi LH, Zagari RM, Bazzoli F. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2014;19 Suppl 1:1–5. doi: 10.1111/hel.12165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rothenbacher D, Winkler M, Gonser T, Adler G, Brenner H. Role of infected parents in transmission of helicobacter pylori to their children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2002;21:674–679. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200207000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nguyen VB, Nguyen GK, Phung DC, Okrainec K, Raymond J, Dupond C, Kremp O, Kalach N, Vidal-Trecan G. Intra-familial transmission of Helicobacter pylori infection in children of households with multiple generations in Vietnam. Eur J Epidemiol. 2006;21:459–463. doi: 10.1007/s10654-006-9016-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang YJ, Sheu BS, Lee SC, Yang HB, Wu JJ. Children of Helicobacter pylori-infected dyspeptic mothers are predisposed to H. pylori acquisition with subsequent iron deficiency and growth retardation. Helicobacter. 2005;10:249–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2005.00317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Osaki T, Konno M, Yonezawa H, Hojo F, Zaman C, Takahashi M, Fujiwara S, Kamiya S. Analysis of intra-familial transmission of Helicobacter pylori in Japanese families. J Med Microbiol. 2015;64:67–73. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.080507-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brenner H, Weyermann M, Rothenbacher D. Clustering of Helicobacter pylori infection in couples: differences between high- and low-prevalence population groups. Ann Epidemiol. 2006;16:516–520. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu XC, Shao QQ, Ma J, Yu M, Zhang C, Lei L, Zhou Y, Chen WC, Zhang W, Fang XH, Zhu YZ, Wu G, Wang XM, Han SY, Sun PC, Ding SZ. Family-based Helicobacter pylori infection status and transmission pattern in central China, and its clinical implications for related disease prevention. World J Gastroenterol. 2022;28:3706–3719. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v28.i28.3706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sperti G, van Leeuwen RT, Quax PH, Maseri A, Kluft C. Cultured rat aortic vascular smooth muscle cells digest naturally produced extracellular matrix. Involvement of plasminogen-dependent and plasminogen-independent pathways. Circ Res. 1992;71:385–392. doi: 10.1161/01.res.71.2.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yan L, Chen Y, Chen F, Tao T, Hu Z, Wang J, You J, Wong BCY, Chen J, Ye W. Effect of Helicobacter pylori Eradication on Gastric Cancer Prevention: Updated Report From a Randomized Controlled Trial With 26.5 Years of Follow-up. Gastroenterology. 2022;163:154–162. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marabotti C, Genovesi-Ebert A, Palombo C, Giaconi S, Ghione S. Casual, ambulatory and stress blood pressure: relationships with left ventricular mass and filling. Int J Cardiol. 1991;31:89–96. doi: 10.1016/0167-5273(91)90272-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Langford BJ, So M, Raybardhan S, Leung V, Soucy JR, Westwood D, Daneman N, MacFadden DR. Antibiotic prescribing in patients with COVID-19: rapid review and meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27:520–531. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang D, Mao F, Huang S, Chen C, Li D, Zeng F, Bai F. Recurrence Rate and Influencing Factors of Helicobacter Pylori Infection After Successful Eradication in Southern Coastal China. Int J Gen Med. 2024;17:1039–1046. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S452348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanafi MI, Mohamed AM. Helicobacter pylori infection: seroprevalence and predictors among healthy individuals in Al Madinah, Saudi Arabia. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 2013;88:40–45. doi: 10.1097/01.EPX.0000427043.99834.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ding Z, Zhao S, Gong S, Li Z, Mao M, Xu X, Zhou L. Prevalence and risk factors of Helicobacter pylori infection in asymptomatic Chinese children: a prospective, cross-sectional, population-based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42:1019–1026. doi: 10.1111/apt.13364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang X, Shu X, Li Q, Li Y, Chen Z, Wang Y, Pu K, Zheng Y, Ye Y, Liu M, Ma L, Zhang Z, Wu Z, Zhang F, Guo Q, Ji R, Zhou Y. Prevalence and risk factors of Helicobacter pylori infection in Wuwei, a high-risk area for gastric cancer in northwest China: An all-ages population-based cross-sectional study. Helicobacter. 2021;26:e12810. doi: 10.1111/hel.12810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu Y, Zhou X, Wu J, Su J, Zhang G. Risk Factors and Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori Infection in Persistent High Incidence Area of Gastric Carcinoma in Yangzhong City. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2014;2014:481365. doi: 10.1155/2014/481365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Araújo GRL, Marques HS, Santos MLC, da Silva FAF, da Brito BB, Correa Santos GL, de Melo FF. Helicobacter pylori infection: How does age influence the inflammatory pattern? World J Gastroenterol. 2022;28:402–411. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v28.i4.402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xie Q, He Y, Zhou D, Jiang Y, Deng Y, Li R. Recent research progress on the correlation between metabolic syndrome and Helicobacter pylori infection. PeerJ. 2023;11:e15755. doi: 10.7717/peerj.15755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suki M, Leibovici Weissman Y, Boltin D, Itskoviz D, Tsadok Perets T, Comaneshter D, Cohen A, Niv Y, Dotan I, Leibovitzh H, Levi Z. Helicobacter pylori infection is positively associated with an increased BMI, irrespective of socioeconomic status and other confounders: a cohort study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;30:143–148. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000001014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Al-Zubaidi AM, Alzobydi AH, Alsareii SA, Al-Shahrani A, Alzaman N, Kassim S. Body Mass Index and Helicobacter pylori among Obese and Non-Obese Patients in Najran, Saudi Arabia: A Case-Control Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:2586. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15112586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soares GAS, Moraes FAS, Ramos AFPL, Santiago SB, Germano JN, Fernandes GA, Curado MP, Barbosa MS. Dietary habits and Helicobacter pylori infection: is there an association? Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2023;16:17562848231160620. doi: 10.1177/17562848231160620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lender N, Talley NJ, Enck P, Haag S, Zipfel S, Morrison M, Holtmann GJ. Review article: Associations between Helicobacter pylori and obesity--an ecological study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:24–31. doi: 10.1111/apt.12790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang YJ, Sheu BS, Yang HB, Lu CC, Chuang CC. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori increases childhood growth and serum acylated ghrelin levels. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:2674–2681. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i21.2674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Romo-González C, Mendoza E, Mera RM, Coria-Jiménez R, Chico-Aldama P, Gomez-Diaz R, Duque X. Helicobacter pylori infection and serum leptin, obestatin, and ghrelin levels in Mexican schoolchildren. Pediatr Res. 2017;82:607–613. doi: 10.1038/pr.2017.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Azami M, Baradaran HR, Dehghanbanadaki H, Kohnepoushi P, Saed L, Moradkhani A, Moradpour F, Moradi Y. Association of Helicobacter pylori infection with the risk of metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2021;13:145. doi: 10.1186/s13098-021-00765-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arslan E, Atilgan H, Yavaşoğlu I. The prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in obese subjects. Eur J Intern Med. 2009;20:695–697. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2009.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moayyedi P, Axon AT, Feltbower R, Duffett S, Crocombe W, Braunholtz D, Richards ID, Dowell AC, Forman D Leeds HELP Study Group. Relation of adult lifestyle and socioeconomic factors to the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:624–631. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.3.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sgambato D, Visciola G, Ferrante E, Miranda A, Romano L, Tuccillo C, Manguso F, Romano M. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in sexual partners of H. pylori-infected subjects: Role of gastroesophageal reflux. United European Gastroenterol J. 2018;6:1470–1476. doi: 10.1177/2050640618800628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Razuka-Ebela D, Polaka I, Parshutin S, Santare D, Ebela I, Murillo R, Herrero R, Tzivian L, Young Park J, Leja M. Sociodemographic, Lifestyle and Medical Factors Associated with Helicobacter Pylori Infection. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2020;29:319–327. doi: 10.15403/jgld-870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shu L, Zheng PF, Zhang XY, Feng YL. Dietary patterns and Helicobacter pylori infection in a group of Chinese adults ages between 45 and 59 years old: An observational study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019;98:e14113. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000014113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lu L, Chen B, Zhang X, Xu Y, Jin L, Qian H, Liang ZF. The effect of phytochemicals in N-methyl-N-nitro-N-nitroguanidine promoting the occurrence and development of gastric cancer. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1203265. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2023.1203265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lim SL, Canavarro C, Zaw MH, Zhu F, Loke WC, Chan YH, Yeoh KG. Irregular Meal Timing Is Associated with Helicobacter pylori Infection and Gastritis. ISRN Nutr. 2013;2013:714970. doi: 10.5402/2013/714970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.He S, He X, Duan Y, Luo Y, Li Y, Li J, Li Y, Yang P, Wang Y, Xie J, Liu M, Sk Cheng A. The impact of diet, exercise, and sleep on Helicobacter pylori infection with different occupations: a cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2024;24:692. doi: 10.1186/s12879-024-09505-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khoder G, Mina S, Mahmoud I, Muhammad JS, Harati R, Burucoa C. Helicobacter pylori Infection in Tripoli, North Lebanon: Assessment and Risk Factors. Biology (Basel) 2021;10:599. doi: 10.3390/biology10070599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee YJ, Ssekalo I, Kazungu R, Blackwell TS Jr, Muwereza P, Wu Y, Sáenz JB. Community prevalence of Helicobacter pylori and dyspepsia and efficacy of triple therapy in a rural district of eastern Uganda. Heliyon. 2022;8:e12612. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e12612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pandeya N, Whiteman DC Australian Cancer Study. Prevalence and determinants of Helicobacter pylori sero-positivity in the Australian adult community. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:1283–1289. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Flores-Treviño CE, Urrutia-Baca VH, Gómez-Flores R, De La Garza-Ramos MA, Sánchez-Chaparro MM, Garza-Elizondo MA. Molecular detection of Helicobacter pylori based on the presence of cagA and vacA virulence genes in dental plaque from patients with periodontitis. J Dent Sci. 2019;14:163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jds.2019.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhao Y, Gao X, Guo J, Yu D, Xiao Y, Wang H, Li Y. Helicobacter pylori infection alters gastric and tongue coating microbial communities. Helicobacter. 2019;24:e12567. doi: 10.1111/hel.12567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ma J, Yu M, Shao QQ, Yu XC, Zhang C, Zhao JB, Yuan L, Qi YB, Hu RB, Wei PR, Xiao W, Chen Q, Jia BL, Chen CL, Lu H, Ding SZ. Both family-based Helicobacter pylori infection control and management strategy and screen-and-treat strategy are cost-effective for gastric cancer prevention. Helicobacter. 2022;27:e12911. doi: 10.1111/hel.12911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No additional data are available.