Abstract

BACKGROUND

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a prevalent pathogen associated with various diseases. Cholelithiasis is also a common condition. H. pylori infection has been identified in the biliary system, suggesting its potential involvement in biliary diseases. However, the specific role of H. pylori in the development of cholelithiasis remains inconclusive.

AIM

To investigate the potential association between H. pylori infection and the development of cholelithiasis.

METHODS

We performed a retrospective study in more than 70000 subjects in health examination center from 3 institutions in the middle, northern and eastern China, from October 2018 to December 2021, to explore the potential association between H. pylori and cholelithiasis through univariate and multivariate analysis. Meanwhile, the influence of H. pylori on biliary-related parameters was investigated. A comprehensive analysis of previous studies concerned about H. pylori and cholelithiasis was also executed.

RESULTS

In our multi-center study, H. pylori was positively associated with cholelithiasis [odds ratio (OR) = 1.103, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.001-1.216, P = 0.049]. Furthermore, H. pylori patients had less total and direct bilirubin than uninfected patients, while the total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol were more in H. pylori-positive participants (P < 0.05). In the published articles, the cohort studies indicated H. pylori was a risk factor of cholelithiasis (hazard ratio =1.3280, 95%CI: 1.1810-1.4933, P < 0.0001). The pooled results of case-control and cross-sectional studies showed positive association between H. pylori and cholelithiasis in Asia (OR = 1.5993, 95%CI: 1.0353-2.4706, P = 0.034) but not in Europe (OR = 1.2770, 95%CI: 0.8446-1.9308, P = 0.246). Besides, H. pylori was related to a higher choledocholithiasis/cholecystolithiasis ratio (OR = 3.3215, 95%CI: 1.1034-9.9986, P = 0.033).

CONCLUSION

H. pylori is positively correlated with cholelithiasis, choledocholithiasis phenotype particularly, especially in Asia, which may be relevant to bilirubin/cholesterol metabolism. Cohort studies confirm an increased risk of cholelithiasis in H. pylori patients.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, Cholelithiasis, Bilirubin, Cholesterol, Multi-center

Core Tip: Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection in the biliary system has been identified but its relationship with cholelithiasis is not clear. This study is to analyze the possible correlation between H. pylori and cholelithiasis, and found that H. pylori infection was associated with an increased risk of cholelithiasis, particularly the choledocholithiasis phenotype. The metabolism of bilirubin and cholesterol could be a possible explanation for the link between H. pylori and cholelithiasis. Patients with H. pylori should be screened for cholelithiasis, and H. pylori eradication may help prevent cholelithiasis. In the management of cholelithiasis, the potential influence of H. pylori infection should also be considered.

INTRODUCTION

Cholelithiasis is a high-prevalence disease. The global prevalence of gallstones in 21st century is 6.1% with the highest prevalence in South America (11.2%) followed by North America (8.1%), Africa (6.6%), Europe (6.4%), and Asia (5.1%)[1]. Meanwhile, gallstone disease has incidence of 0.47 per 100 person-years[1]. In the United States, the prevalence of gallstone disease was 13.9% from 2017 to March 2020 which is almost twice as in 1988-1994[2]. Gallstone disease is associated with factors including female gender, older age, body mass index, and other variables[1,2]. Additionally, the role of bacteria in cholelithiasis has been extensively researched[3]. Bacteria can hydrolyze bilirubin glucuronide into free bilirubin and glucuronic acid to form calcium bilirubinate through β-glucuronidase[4]. A majority of Chinese patients with calcium bilirubinate stone were found to be infected by β-glucuronidase-active bacteria[5]. Beyond bilirubin conjugates, bacteria also hydrolyze biliary lipids to form calcium salt sediment and brown pigment stones[6]. Furthermore, Stewart et al[7] identified bacteria could also serve as the nucleus for stone formation in pigment stones. Moreover, bacteria-associated cholelithiasis may also be related to factors such as phospholipase, mucin, and prostaglandin, etc.[8].

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is the risk factor for gastritis, peptic ulcer, gastric cancer and so on[9,10]. The prevalence of H. pylori between 2015 and 2019 in China mainland was 40.0%[11], which is still a heavy burden. H. pylori infection in the biliary system has been reported, suggesting a potential relationship with biliary diseases. Various studies found evidence of H. pylori infection in bile, gallbladder, and gallstones using different methods[12-14]. However, conclusions regarding the relationship between H. pylori and cholelithiasis remain controversial. Some reports indicate that H. pylori-infected patients have a higher risk of cholelithiasis[15], while other studies have found no significant association between H. pylori and cholelithiasis[16]. The treatment of H. pylori could have potential influence on the biliary system. Clarithromycin, a kind of antibiotics commonly used in H. pylori eradication, was found to strengthen the contraction of gallbladder in gallstone patients[17]. Besides antibiotics, some natural substance with less side effects, such as Hericium erinaceus[18,19], could both inhibit H. pylori and benefit biliary system.

Clarifying the association between H. pylori infection and cholelithiasis is essential for a deeper understanding of the role of H. pylori in the hepatobiliary system. This knowledge could benefit the clinical practice of both H. pylori infection and cholelithiasis, holding significant public health implications. Therefore, we conducted a multi-center study encompassing three hospitals from central, northern and eastern China. Additionally, we analyzed evidence from published articles elucidate the potential relationship between H. pylori and cholelithiasis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

New original data

Study subjects: The study included participants underwent health examinations at three centers in the middle, northern and eastern China, from October 2018 to December 2021. The study followed the “Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology” statements[20]. All the included patients received both 14C urease breath test (14C-UBT) and ultrasound examination. At the same time, they also took blood test for related parameters including bilirubin, bile acid, cholesterol and triglyceride levels. The following information was obtained from the health examination results and previous medical records of the participants: (1) Age and gender; (2) The results of 14C-UBT and ultrasound examination; (3) Other relevant medical history, such as major health problems, medication history, and surgical history; and (4) Parameters related to biliary system mentioned above.

According to their examination results and previous medical records, participants would be excluded if one of the following criteria was met: (1) Antibiotic, bismuth, and other antibacterial medicine use history within one month, or proton pump inhibitors use history within half a month; (2) Cholecystectomy history and no stones in the residual biliary system; and (3) H. pylori eradication treatment history. This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the clinical research ethics committee of every center (Ethics Committee Approval No. 23277, No. Z-2024-028, and No. G-2024-11). The requirement to obtain informed written consent was waived because the study is retrospective and did not involve the privacy and commercial interests of patients, and measures were taken to anonymize biological samples, and formulated a strict data security management system and technical protection system for the storage, use, and sharing of biological samples and data to ensure data and personal information security.

The diagnosis of cholelithiasis was established through ultrasound examination (Siemens Acuson™ Sequoia 512 Doppler ultrasound, Siemens, German). Based on the ultrasound findings, the study participants were categorized into two groups: The cholelithiasis group (comprising individuals with confirmed cholelithiasis) and the control group (consisting of subjects without evidence of cholelithiasis). The participants received 14C-UBT after fasting for solid and liquid food overnight or for a minimum of 3 hours. The criterion for H. pylori positive is a result of 14C-UBT greater than or equal to 100 disintegrations per minute. Professional specialists conducted the test process and interpreted the results.

Statistical analysis: Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). Categorical data were expressed as percentages and analyzed using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact probability method. Measurement data were expressed as mean ± SD and analyzed by t-test. Logistic regression was performed to explore factors related to cholelithiasis. The parameters, which have significant difference between cholelithiasis group and control group, and those are known to be related to cholelithiasis, would be included in the multivariable analysis. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Systematic review and meta-analysis

This meta-analysis adheres to the guidelines outlined in meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology[21] (Supplementary Table 1) and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses[22]. The literature screening and data extraction in the systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted by 2 investigators independently.

Search strategy: We conducted a comprehensive literature search in PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library databases up to May 10, 2024. The following search strategy was employed: “((Helicobacter pylori) OR (H. pylori) OR (HP) OR (Helicobacter) OR (Helicobacter species) OR (Helicobacter spp.) OR (Helicobacter genus) OR (Helicobacter pylori infection) OR (Helicobacter infection) OR (pylori) OR (enterohepatic Helicobacter spp.) OR campylobacter OR (campylobacter infection) OR campylobacteriosis OR (Campylobacter pylori* OR Campylobacter pylori subsp. Pylori) OR (campylobacter spp)) AND (cholelithiasis or cholecystolithiasis or hepatolithiasis OR choledocholithiasis OR gallstone* OR gall* stone* OR (gallbladder AND stone*) OR (gallbladder AND cholelith*) OR (gallbladder AND lithiasis) OR bilestone* OR (bile AND stone*) OR (bile AND lithiasis) OR (bile AND cholelith*) OR (biliary AND calculus) OR (biliary AND stone*) OR (biliary AND cholelith*) OR (biliary AND lithiasis))”. All search results were exported to EndNote 20 (Thomson ResearchSoft, United States) for further screening. Additionally, a manual search was performed to identify any relevant studies not captured by the initial search.

Study screening criteria: The inclusion criteria were: (1) Participants (P): Patients with examination results for cholelithiasis and H. pylori; (2) Intervention/exposure (I): H. pylori infection; (3) Comparison (C): Participants free of H. pylori; (4) Outcomes (O): The prevalence/incidence of cholelithiasis; and (5) Studies (S): Case-control studies, cohort studies, or cross-sectional studies. The exclusion criteria were as follows: Papers not written in English; articles that were not original research; studies conducted on animals or cells; research not pertaining to H. pylori or cholelithiasis; and studies for which the necessary data could not be obtained.

Data extraction and quality assessment: The following information was extracted from included studies: Publication year, first author, region, types of cholelithiasis, sample sizes, sample sources and detection methods of H. pylori, and H. pylori status of each group. The Methodological Index for Non-randomized Studies[23] was employed to assess the quality of the included studies. The maximum attainable score is 24 for comparative studies and 16 for non-comparative studies. A higher score is indicative of superior methodological quality.

Data analysis: Data analysis was performed using the Meta package of R (version 4.3.2)[24]. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Heterogeneity was assessed using I2[25]. If I2 < 50% the common effect model (also referred to as the fixed effect model[26]) would be used, otherwise we will reduce the heterogeneity by subgroup analysis. If the heterogeneity is still high, the random effect model would be employed. I2 values of 25%, 50%, and 75% were considered to represent low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively[27]. Sensitivity analysis was conducted using the leave-one-out method. Publication bias was evaluated using a funnel plot, with a symmetric plot indicating no significant bias[28]. If the Peters’ test[29] showed a P value < 0.05, there is significant publication bias.

To determine the relationship between H. pylori infection and cholelithiasis, we calculated the summarized odds ratios (OR) of case-control/cross-sectional studies, and hazard ratios of cohort studies with a 95% confidence interval (CI). Subgroup analysis was also performed based on the regions of where the studies were conducted. Furthermore, we analyzed the association between H. pylori and various cholelithiasis phenotypes.

RESULTS

New original data

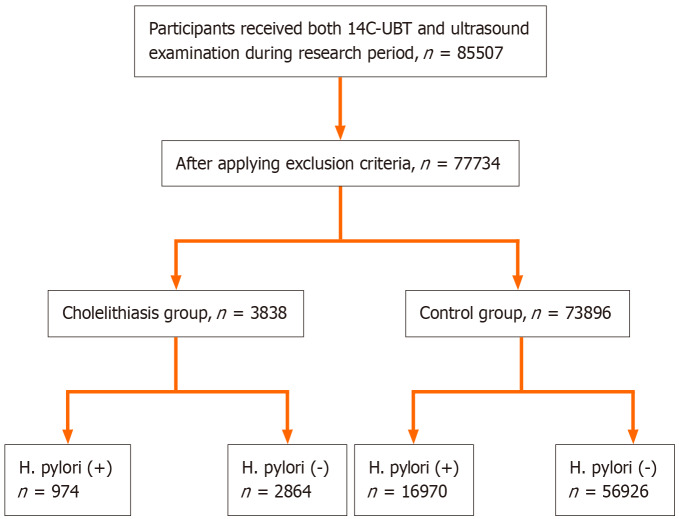

Characteristics of study subjects: There were 77734 participants included in this research after applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Figure 1). The number of subjects from the Third Xiangya Hospital, the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University, and Shanxi Coal Central Hospital was 54631, 19241, and 3862, respectively. There were 48159 men and 29575 women. Subjects were divided into 2 groups as mentioned above. The cholelithiasis group included 3838 (4.9%) patients, while the control group included 73896 participants (Table 1).

Figure 1.

The flow chart of the study subjects screening process. H. pylori: Helicobacter pylori; 14C-UBT: 14C urease breath test; H. pylori (+): Helicobacter pylori-positive; H. pylori (-): Helicobacter pylori-negative (detailed data shown in Table 1).

Table 1.

The characteristics of participants

|

|

Cholelithiasis group

|

Control group

|

P value

|

| H. pylori+ (n) | 974 | 16970 | 0.001 |

| H. pylori- (n) | 2864 | 56926 | |

| Male (n) | 2287 | 45872 | 0.002 |

| Female (n) | 1551 | 28024 | |

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 51.01 ± 11.95 | 43.61 ± 12.06 | < 0.001 |

| Total bilirubin (μmol/L), mean ± SD | 13.1 ± 5.7 | 13.2 ± 5.5 | 0.627 |

| Direct bilirubin (μmol/L), mean ± SD | 3.8 ± 1.9 | 3.8 ± 2.4 | 0.665 |

| Total bile acid (μmol/L), mean ± SD | 4.7 ± 7.0 | 4.0 ± 5.3 | < 0.001 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L), mean ± SD | 5.06 ± 0.99 | 5.00 ± 0.97 | 0.001 |

| Triglyceride (mmol/L), mean ± SD | 1.98 ± 1.81 | 1.85 ± 1.84 | < 0.001 |

| HDL-cholesterol (mmol/L), mean ± SD | 1.28 ± 0.27 | 1.32 ± 0.30 | < 0.001 |

| LDL-cholesterol (mmol/L), mean ± SD | 2.89 ± 0.85 | 2.85 ± 0.82 | 0.002 |

H. pylori: Helicobacter pylori; H. pylori+: Helicobacter pylori-positive; H. pylori-: Helicobacter pylori-negative; LDL: Low-density lipoprotein; HDL: High-density lipoprotein.

Association between H. pylori and cholelithiasis: According to our data, 23.1% of all the participants were infected by H. pylori. H. pylori infection rate was significantly higher in cholelithiasis group compared to the control group (25.4% vs 23.0%, P = 0.001). Furthermore, cholelithiasis patients exhibited higher female rate, age, total bile acid, total cholesterol, triglyceride, and low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-cholesterol, while high-density lipoprotein (HDL)-cholesterol was higher in control group (P < 0.05) (Table 1). Besides the factors with significant difference between cholelithiasis and control group mentioned above, we also include bilirubin level, a known risk factor of cholelithiasis[30], in the multivariable logistic regression which showed H. pylori may be related to cholelithiasis (OR =1.103, 95%CI: 1.001-1.216, P = 0.049). Besides, other factors including age > 60 years, total bile acid, HDL-cholesterol, total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, total cholesterol, triglyceride, and female gender, were also associated with cholelithiasis (Table 2). This study included 74 patients with hepatolithiasis and 3724 cholecystolithiasis patients for phenotype analysis. Patients with both hepatolithiasis and cholecystolithiasis were excluded from this part of the study. The H. pylori infection rates didn’t differ significantly between hepatolithiasis and cholecystolithiasis patients (Table 3).

Table 2.

The results of multivariable logistic regression on factors associated with cholelithiasis

|

|

OR (95%CI)

|

P value

|

| H. pylori infection | 1.103 (1.001-1.216) | 0.049 |

| Age > 60 years | 2.031 (1.821-2.266) | < 0.001 |

| Total bile acid (μmol/L) | 1.017 (1.011-1.023) | < 0.001 |

| HDL-cholesterol (mmol/L) | 0.361 (0.296-0.441) | < 0.001 |

| Total bilirubin (μmol/L) | 1.027 (1.012-1.043) | 0.001 |

| Direct bilirubin (μmol/L) | 0.938 (0.897-0.982) | 0.006 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 1.095 (1.038-1.154) | 0.001 |

| Triglyceride (mmol/L) | 0.969 (0.942-0.997) | 0.032 |

| Female gender | 1.493 (1.355-1.644) | < 0.001 |

H. pylori: Helicobacter pylori; HDL: High-density lipoprotein; OR: Odds ratio; CI: Confidence interval.

Table 3.

The results of phenotype analysis and parameters comparison

|

|

H. pylori+

|

H. pylori-

|

P value

|

| Phenotype | |||

| Hepatolithiasis (n) | 21 | 53 | 0.546 |

| Cholecystolithiasis (n) | 942 | 2782 | |

| Parameters | |||

| Total bilirubin (μmol/L) | 12.5 ± 5.2 | 13.2± 5.2 | < 0.001 |

| Direct bilirubin (μmol/L) | 3.6 ± 1.6 | 3.9 ± 1.6 | < 0.001 |

| Total bile acid (μmol/L) | 3.8± 5.1 | 3.6 ± 4.3 | 0.055 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 4.84 ± 0.90 | 4.77 ± 0.86 | < 0.001 |

| Triglyceride (mmol/L) | 1.26 ± 0.94 | 1.27 ± 1.00 | 0.489 |

| HDL-cholesterol (mmol/L) | 1.41 ± 0.29 | 1.41 ± 0.29 | 0.994 |

| LDL-cholesterol (mmol/L) | 2.83 ± 0.76 | 2.76 ± 0.73 | < 0.001 |

H. pylori: Helicobacter pylori; H. pylori+: Helicobacter pylori-positive; H. pylori-: Helicobacter pylori-negative; LDL: Low-density lipoprotein; HDL: High-density lipoprotein.

H. pylori and biliary-system parameters: To further investigate the possible mechanism of H. pylori-related cholelithiasis, we measured parameters associated with the biliary system in H. pylori-positive and H. pylori-negative participants (Table 3). Patients with hepatopancreatobiliary and metabolic diseases (diabetes, hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism and others) were excluded from this analysis. A total of 18996 participants (4034 in the H. pylori-positive group and 14962 in the H. pylori-negative group) were included in this section. Total bilirubin as well as direct bilirubin was significantly lower in the H. pylori-positive group. More total cholesterol and LDL-cholesterol were found in the H. pylori-infected patients. This meant the metabolism of bilirubin and cholesterol is related to H. pylori status, which may contribute to the formation of cholelithiasis.

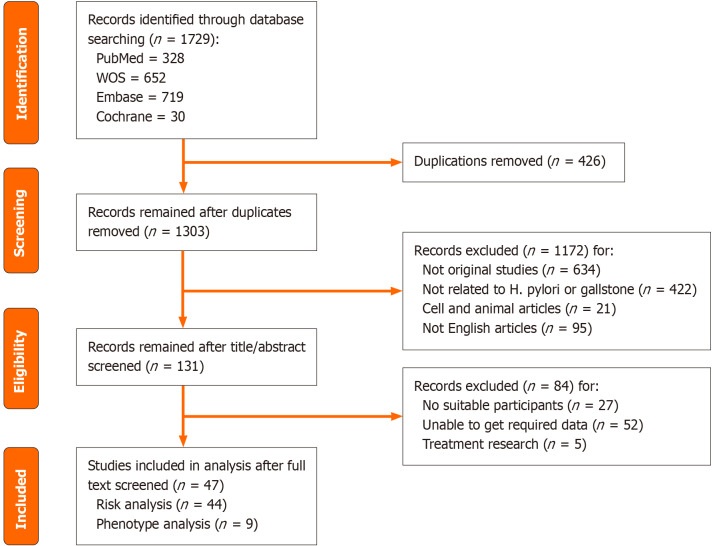

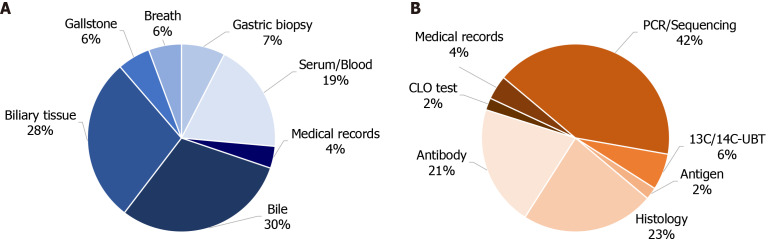

Systematic review and meta-analysis

Profiles of included studies: A total of 1729 papers were retrieved. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 47 papers were ultimately included in the analysis. Risk analysis was performed on 44 articles, which collectively included 40624 cholelithiasis cases and 673534 non-cholelithiasis subjects. Phenotype analysis was conducted on 9 articles, encompassing 633 cholelithiasis cases. The literature screening process is illustrated in Figure 2. The characteristics of the included articles are detailed in Table 4 and Supplementary Tables 2 and 3. Biliary-related samples were the most frequently chosen samples, providing direct evidence of H. pylori infection in the biliary system (Figure 3A). Polymerase chain reaction/sequencing was the most commonly employed method for detecting H. pylori (Figure 3B). The average Methodological Index for Non-randomized Studies score for comparative studies was 16.39 ± 2.10 and for non-comparative studies, it was 11.00 ± 1.00 (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

The flow chart of the literature screening process. Detailed included articles shown in Table 4. H. pylori: Helicobacter pylori; WOS: Wed of Science.

Table 4.

The characteristics of included studies

|

Ref.

|

Region

|

Cholelithiasis type

|

Sample source for H. pylori

|

Method for H. pylori

|

No. of cholelithiasis

|

No. of non-cholelithiasis

|

| Loosen et al[54], 2024 | Germany | Cholelithiasis | Medical records | Medical records | 2394 | 34669 |

| Sermet[55], 2024 | Turkey | Cholelithiasis | Gastric biopsy | Histology | 8753 | 5565 |

| Azimirad et al[12], 2023 | Iran | Common bile duct stones | Bile | 16S rDNA sequencing | 9 | 6 |

| Cen et al[15], 2023 | China | Gallstones | Breath | 13C/14C-UBT | 60 | 1132 |

| Hashimoto et al[56], 2022 | Japan | Gallstones | Serum | Antibody test | 14 | 47 |

| Higashizono et al[57], 2022 | Japan | Gallstones | Medical records | Medical records | 23843 | 588087 |

| Jahantab et al[58], 2021 | Iran | Cholelithiasis | Bile | Antigen test | 132 | / |

| Kucuk and Küçük[13], 2021 | Turkey | Gallstones | Gallbladder | Giemsa | 131 | 82 |

| Zhang et al[16], 2020 | China | Gallstones | Breath | 13C/14C-UBT | 935 | 935 |

| Ari et al[59], 2019 | Turkey | Gallstones | Gallbladder | Giemsa | 27 | 33 |

| Cherif et al[60], 2019 | Morocco | Bile duct stones | Gallbladder | IHC | 48 | 41 |

| Kerawala et al[61], 2019 | Pakistan | Gallstones | Serum | Antibody test | 45 | 45 |

| Fatemi et al[62], 2018 | Iran | Gallstones | Serum | ELISA | 52 | 25 |

| Xu et al[63], 2018 | China | Gallstones | Serum | ELISA | 995 | 16976 |

| Seyyedmajidi[64], 2017 | Iran | Common bile duct stones | Bile | PCR | 150 | / |

| Choi et al[65], 2016 | Korea | Gallstones | Gastric biopsy | CLO test | 39 | 607 |

| Dar et al[66], 2016 | India | Hepatobiliary lithiasis | Bile | PCR | 50 | 25 |

| Patnayak et al[67], 2016 | India | Gallstones | Gallbladder | IHC | 40 | 5 |

| Tajeddin et al[68], 2016 | Iran | Gallstones | Bile | PCR | 74 | 28 |

| Guraya et al[69], 2015 | Saudi Arabia | Gallstones | Serum | ELISA | 95 | 30 |

| Zhang et al[70], 2015 | China | Gallstones | Breath | 13C-UBT | 882 | 9134 |

| Murphy et al[71], 2014 | Finland | Gallstones | Serum | Serology | 10 | 214 |

| Takahashi et al[50], 2014 | Japan | Gallstones | Serum | ELISA | 694 | 14857 |

| Zhou et al[36], 2013 | China | Gallstones | Gallbladder | PCR | 267 | 59 |

| Boonyanugomol et al[72], 2012 | Thailand | Cholelithiasis | Bile | PCR | 53 | 103 |

| Jahani Sherafat et al[73], 2012 | Iran | Gallstones | Bile | PCR | 74 | 28 |

| Yakoob et al[74], 2011 | Pakistan | Cholelithiasis | Gallbladder/bile | IHC/PCR | 89 | 49 |

| Bostanoğlu et al[75], 2010 | Turkey | Calculous cholecystitis | Gallbladder/bile/stone | PCR | 47 | 3 |

| Lee et al[14], 2010 | Korea | Gallstones | Gallstone | PCR | 22 | / |

| Popović et al[76], 2010 | Serbia | Cholelithiasis | Blood | Serology | 3 | 204 |

| Griniatsos et al[77], 2009 | Greece | Cholesterol gallstones | Gallbladder | Histology | 89 | 42 |

| Yucebilgili et al[78], 2009 | Turkey | Cholelithiasis | Gallbladder | PCR | 41 | 27 |

| Misra et al[79], 2007 | India | Gallstones | Gallbladder | Histology | 116 | 45 |

| Abayli et al[80], 2005 | Turkey | Mixed cholesterol gallstones | Gallbladder | HE | 77 | 20 |

| Kobayashi et al[81], 2005 | Japan | Cholelithiasis | Bile | PCR | 30 | 27 |

| Farshad et al[82], 2004 | Iran | Gallstones | Gallstone/bile | PCR | 33 | 40 |

| Chen et al[83], 2003 | New Zealand | Gallstones | Gallbladder | PCR | 70 | 52 |

| Silva et al[84], 2003 | Brazil | Cholelithiasis | Gallbladder | PCR | 46 | 18 |

| Bulajic et al[43], 2002 | Yugoslavia | Gallstones | Bile | PCR | 63 | 26 |

| Bulajic et al[85], 2002 | Yugoslavia | Biliary lithiasis | Bile | PCR | 65 | 7 |

| Fukuda et al[86], 2002 | Japan | Cholecystolithiasis | Gallbladder/bile | PCR | 15 | 23 |

| Harada et al[87], 2001 | Japan | Cholelithiasis | Bile/biliary epithelium | PCR | 53 | 16 |

| Myung et al[88], 2000 | Korea | Hepatolithiasis | Serum | ELISA | 30 | 13 |

| Roe et al[89], 1999 | Korea | Intrahepatic duct stones | Bile | PCR | 11 | 21 |

| Figura et al[90], 1998 | Italy | Gallstones | Serum | ELISA | 112 | 112 |

| Kochhar et al[91], 1993 | India | Common bile duct stone | Gastric biopsy | Giemsa | 3 | 15 |

| Kellosalo et al[92], 1991 | Finland | Gallstones | Gastric biopsy | WS | 47 | 41 |

H. pylori: Helicobacter pylori; WS: Warthin-Starry silver stain; ELISA: Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay; PCR: Polymerase chain reaction; HE: Hematoxylin and eosin staining; 13C/14C-UBT: 13C or 14C urease breath test; IHC: Immunohistochemistry; CLO: Campylobacter-like organism.

Figure 3.

The distribution of sample sources and detection methods for Helicobacter pylori of included studies. A: Sample sources for Helicobacter pylori; B: Detection methods for Helicobacter pylori. Detailed data shown in Table 4. 13C/14C-UBT: 13C or 14C urease breath test; CLO: Campylobacter-like organism; PCR: Polymerase chain reaction.

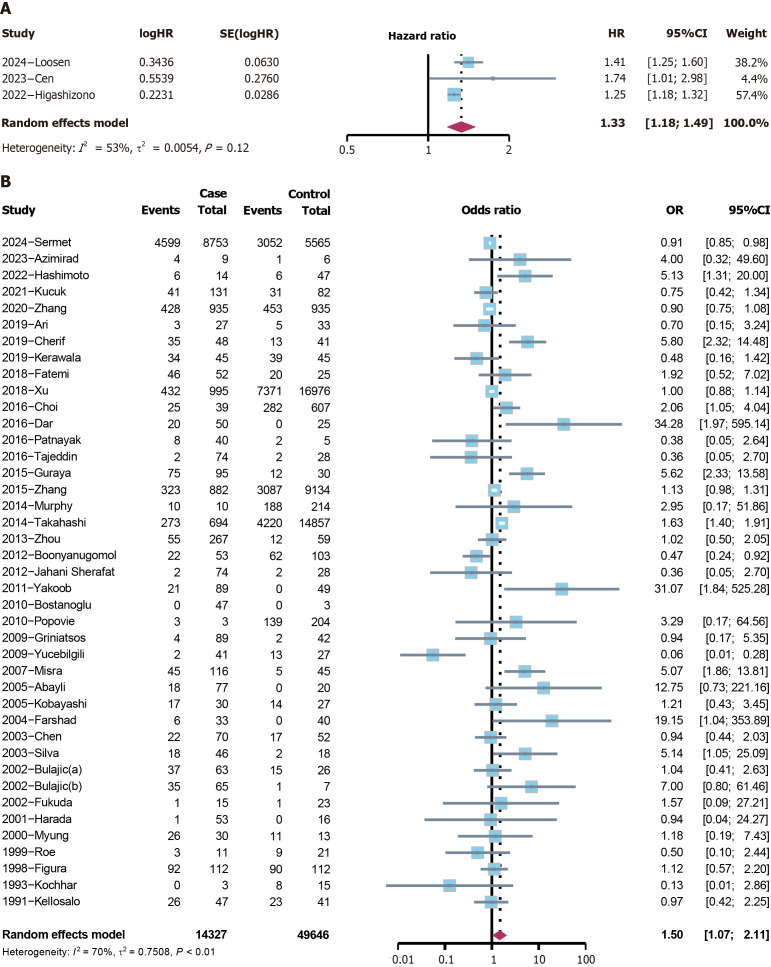

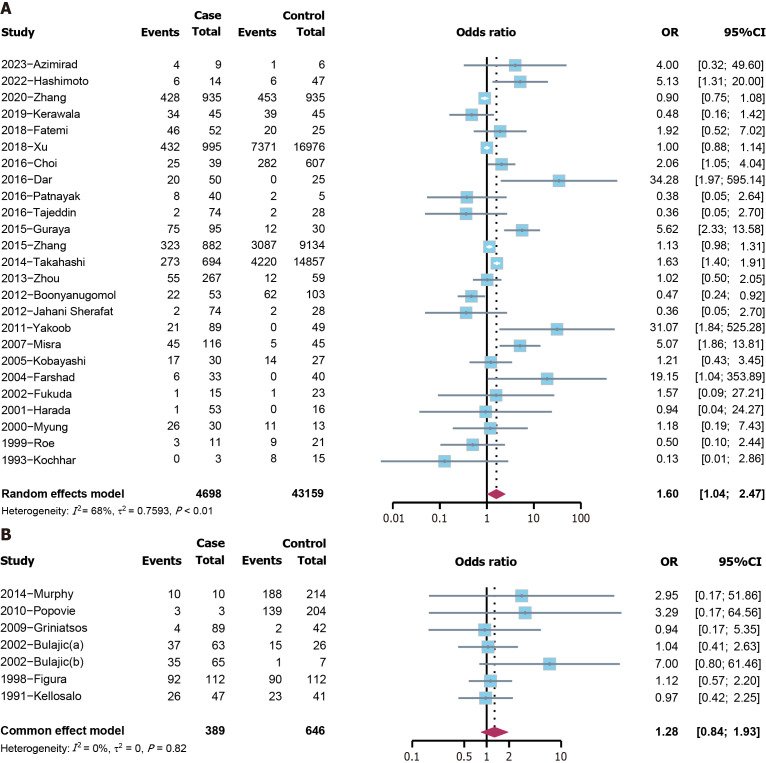

H. pylori and cholelithiasis risk: The analysis included three cohort studies, revealing that H. pylori was a risk factor for cholelithiasis (hazard ratio = 1.3280, 95%CI: 1.1810-1.4933, P < 0.0001) (Figure 4A). Among the 41 case-control and cross-sectional studies, a positive association was found between cholelithiasis and H. pylori (OR = 1.5042, 95%CI: 1.0698-2.1148, P = 0.019) (Figure 4B). The funnel plot demonstrated symmetry (Supplementary Figure 1), and the Peters’ test indicated no publication bias (P = 0.259). The sensitivity analysis identified no distinct variation (Supplementary Figure 2). Since the heterogeneity is relatively high, subgroup analyses were performed based on continents. Studies conducted in Asia showed a positive association between cholelithiasis and H. pylori (OR = 1.5993, 95%CI: 1.0353-2.4706, P = 0.034), while in Europe, the relationship was not statistically significant (P = 0.246) (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

The forest plot of the 44 included studies for the risk analysis of cholelithiasis. A: Cohort studies; B: Case-control and cross-sectional studies. HR: Hazard ratio; CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio.

Figure 5.

The results of subgroup risk analyses of cholelithiasis. A: The subgroup analysis of studies in Asia; B: The subgroup analysis of studies in Europe. CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio.

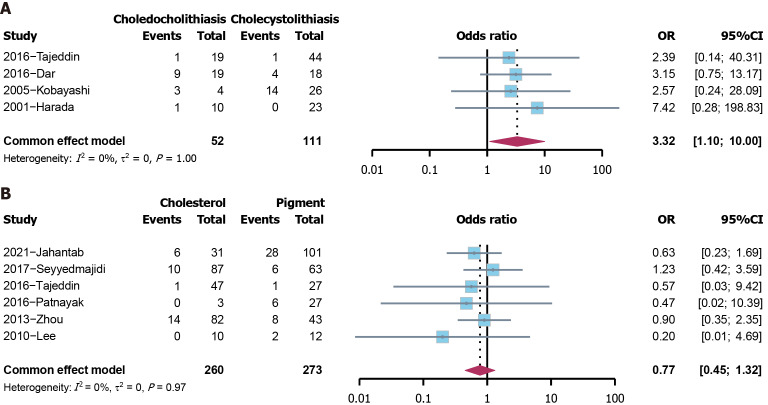

H. pylori and the phenotypes of cholelithiasis: The effect of H. pylori on the phenotypes of cholelithiasis was further analyzed. Regarding the position of stones, H. pylori-positive patients were more common in the choledocholithiasis group compared to those in the cholecystolithiasis group (OR = 3.3215, 95%CI: 1.1034-9.9986, P = 0.033) (Figure 6A). The chemical components of stones were also investigated. H. pylori infection was not found to be related to the chemical components of stones (P = 0.344) (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

The results of phenotype analysis of cholelithiasis. A: The analysis of position of stones; B: The analysis of chemical components of stones. CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio.

DISCUSSION

In addition to gastroduodenal diseases, numerous extra-gastric diseases have been associated with H. pylori[31]. There is emerging evidence suggesting H. pylori involvement in cholelithiasis[3] but no definitive conclusions have been established. This study aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of the relationship between H. pylori and cholelithiasis with both new original data and published articles. This study’s finding demonstrate that H. pylori infection is correlated with an increased risk of cholelithiasis. Besides, there was a correlation between H. pylori and the choledocholithiasis phenotype. But the chemical constituent of stones is not related to H. pylori.

In our study, the metabolism of bilirubin and cholesterol could be the possible explanation for H. pylori-related cholelithiasis. H. pylori may promote cholelithiasis through the enhancement of endogenous β-glucuronidase[32]. This supports our results of lower total bilirubin and direct bilirubin in H. pylori-infected patients. More direct bilirubin may be hydrolyzed into free bilirubin to form sediment. According to this theory, direct bilirubin may be negatively related to cholelithiasis, while the relationship between free bilirubin and cholelithiasis should be positive. In our analyses, although the bilirubin level didn’t differ between cholelithiasis patients and controls, the multivariable logistic regression found both total bilirubin and direct bilirubin was associated with cholelithiasis, and the results were consistent with the previously proposed theory. In our data, the total cholesterol was higher in H. pylori-positive participants, especially LDL-cholesterol. Cytotoxin-associated gene A (CagA), a virulence factor of H. pylori, could inhibit the uptake of LDL by interacting with the LDL receptor, leading to increased LDL in plasma[33]. The dysregulation of cholesterol metabolism could lead to cholesterol crystal formation, which could develop into gallstones[34]. Increased total cholesterol and LDL is positively correlated with cholesterol stones and cholesterol concentrations in gallstones[35]. In this study, we found total cholesterol and LDL-cholesterol were higher in cholelithiasis patients. The multivariable logistic regression showed total cholesterol was a factor associated with cholelithiasis but LDL-cholesterol was not. The reason for this could be the interaction between H. pylori and LDL-cholesterol, and total cholesterol could partly reflect the level of LDL-cholesterol.

Several other potential mechanisms may contribute to H. pylori-related cholelithiasis. The H. pylori-infected gallbladder mucosa has been shown to express elevated inducible NO synthase and reactive oxygen species[36]. Free radical reactions can play a role in the formation of gallstones[37]. Additionally the urease enzyme produced by H. pylori could induce calcium precipitation through alterations in pH[38]. Phospholipids levels were found to be lower in H. pylori-positive patients compared to the H. pylori-negative patients[39]. This finding is consistent with increased phospholipase activity in infected bile, which may contribute to gallstones formation by causing the precipitation of calcium palmitate[8]. Considering the potential mechanisms, H. pylori may be associated with both cholesterol stones and pigment stones, supporting our results that indicate no relation between H. pylori and the chemical composition of gallstones.

In order to get more comprehensive results, we performed a meta-analysis on other similar studies to compare our research to other investigations. The results of the meta-analysis are consistent with our multi-center study but there is heterogeneity. So, we conducted subgroup analysis based on regions to make the heterogeneity decrease. This study found a higher prevalence of H. pylori in the cholelithiasis group in Asia but not in Europe. Variances among H. pylori strains from different regions could contribute to the differing results. The Western type of CagA genes of H. pylori were similar in Japan, China, Iran, and the United States but differed from those in Thailand[40]. Additionally, the prevalence of cholelithiasis varies by regions, with higher prevalence in Europe than in Asia[1]. The relatively high prevalence of cholelithiasis in Europe may overshadow the role of H. pylori. Furthermore, the prevalence of H. pylori is lower in Europe compared to Asia[41]. The lack of study samples in certain regions could also influence the results.

In the meta-analysis, higher H. pylori infection rate was found in choledocholithiasis patients when compared with cholecystolithiasis patients, while in our new original data, there was no significant difference in the H. pylori status between cholecystolithiasis group and hepatolithiasis group. This may be due to the fact that H. pylori is easy to infect the common bile duct but difficult to reach the intrahepatic bile duct, supporting the theory that H. pylori in the stomach invades the biliary tract via the common bile duct[42]. A correlation between the presence of H. pylori in the bile and its presence in the stomach has been stated by Bulajic et al[43] and the Western type CagA sequences in hepatobiliary disease patients were similar to those in gastric cancer and gastritis patients[40], supporting the hypothesis that H. pylori in the biliary system originates from the gastrointestinal tract. However, some analyses have yielded contradictory results. The ureI-polymerase chain reaction results of H. pylori in certain gallstones differed from those of H. pylori in the stomach[44]. The vacuolating cytotoxin A and CagA analysis results from gastroduodenal patients were not similar to those from hepatobiliary patients[45]. Similarly, the research of Kafeel et al[46] concluded the presence of H. pylori in gallbladders was independent of its presence in the stomach. These results support the existence of differences between gastroduodenal and hepatobiliary H. pylori strains.

This study offers several advantages. It represents a large-scale multi-center investigation involving over 70000 participants. Our results about the relation between H. pylori and the risk of cholelithiasis are consistent with previous research[47-50]. Besides, we also provide some new information on this topic including the possible mechanism of H. pylori-related cholelithiasis, and the association between H. pylori and the phenotypes of cholelithiasis.

The present study could help the management of both H. pylori infection and cholelithiasis. Another study found that H. pylori eradication may help prevent gallstones[50], which supports our findings. On the one hand, H. pylori-positive patients should be screened for cholelithiasis especially those presenting right upper abdominal pain. On the other hand, patients with cholelithiasis should also consider the possibility of H. pylori infection. H. pylori is considered one of the common causes of post-cholecystectomy syndrome[51]. Research has identified unresolved pain symptoms after cholecystectomy in some patients and they can be alleviated by H. pylori triple therapy[52,53]. This could be attributed to the elimination of H. pylori-induced inflammation.

Despite the contributions of this study, certain limitations persist. Foremost, in our new data, there is only position information of stones, neglecting other phenotypes. We didn’t include more factors related to cholelithiasis like body mass index in this study because of the lack of required data. Besides, in the meta-analysis, the heterogeneity is relatively high. This may be caused by the differences in regions. We performed subgroup analyses according to study regions to reduce the heterogeneity and make region-specific conclusions but the heterogeneity is still over 50%. There are other possible sources of heterogeneity. For example, the detection methods and sample sources varied in the included studies. The serum test for H. pylori antibodies will identify both current and previous infection, while other methods, like UBT, Campylobacter-like organism test etc., detect only currently infected patients. Most of the included studies in the meta-analysis were focused on current infection. Since methods, like the serum tests for H. pylori, can’t distinguish current infection from previous infection, we are not able to make subgroup analysis according to current/previous infection by categorizing the detection methods. The inconsistency of inclusion and exclusion criteria among the included articles may also contribute, such as the age of participants. Some articles investigated specifically in adults, while there are also studies included teenagers and children. However, age-specific subgroup analysis couldn’t be carried out because of the inaccessibility of detailed raw data of certain studies which included both adults and children. Due to insufficient data, the researched phenotype of cholelithiasis in the meta-analysis was restricted to chemical components and the position of stones. To elucidate the precise role of H. pylori in cholelithiasis, further investigations exploring the underlying mechanisms of H. pylori-associated cholelithiasis are warranted.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, our new original data in China revealed H. pylori was related to higher prevalence of cholelithiasis. The meta-analysis supported the results of H. pylori as a risk factor for cholelithiasis. In the subgroup analyses, H. pylori was correlated with an increased risk of cholelithiasis in Asia. Besides, H. pylori was specifically related to choledocholithiasis but it was not associated with the chemical components of stones. The underlying mechanism of H. pylori-related cholelithiasis could potentially involve the relationship between H. pylori and the metabolism of bilirubin and cholesterol, warranting further investigation. Additionally, the routes of H. pylori infection to the biliary system require more extensive exploration.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank all the participants in this study.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the clinical research ethics committee of every center (Ethics Committee Approval No. 23277, No. Z-2024-028, and No. G-2024-11).

Informed consent statement: The requirement to obtain informed written consent was waived.

Conflict-of-interest statement: All the authors report no relevant conflicts of interest for this article.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade B, Grade C, Grade C

Novelty: Grade B, Grade B, Grade B

Creativity or Innovation: Grade B, Grade B, Grade B

Scientific Significance: Grade B, Grade B, Grade B

P-Reviewer: Gravina AG; Zhou R S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Guo X

Contributor Information

Shuo-Yi Yao, Department of Gastroenterology, The Third Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha 410013, Hunan Province, China; Hunan Key Laboratory of Nonresolving Inflammation and Cancer, The Third Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha 410006, Hunan Province, China.

Xin-Meng Li, Department of Gastroenterology, The Third Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha 410013, Hunan Province, China; Hunan Key Laboratory of Nonresolving Inflammation and Cancer, The Third Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha 410006, Hunan Province, China.

Ting Cai, Department of Gastroenterology, The Third Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha 410013, Hunan Province, China; Hunan Key Laboratory of Nonresolving Inflammation and Cancer, The Third Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha 410006, Hunan Province, China.

Ying Li, Health Management Center, The Third Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha 410013, Hunan Province, China.

Lun-Xi Liang, Department of Gastroenterology, The Third Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha 410013, Hunan Province, China; Hunan Key Laboratory of Nonresolving Inflammation and Cancer, The Third Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha 410006, Hunan Province, China.

Xiao-Ming Liu, Department of Gastroenterology, The Third Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha 410013, Hunan Province, China; Hunan Key Laboratory of Nonresolving Inflammation and Cancer, The Third Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha 410006, Hunan Province, China.

Yu-Feng Lei, Department of Gastroenterology, Shanxi Coal Central Hospital, Taiyuan 030006, Shanxi Province, China.

Yong Zhu, Department of Gastroenterology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University, Nanchang 330006, Jiangxi Province, China.

Fen Wang, Department of Gastroenterology, The Third Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha 410013, Hunan Province, China; Hunan Key Laboratory of Nonresolving Inflammation and Cancer, The Third Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha 410006, Hunan Province, China. wfen-judy@csu.edu.cn.

Data sharing statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Wang X, Yu W, Jiang G, Li H, Li S, Xie L, Bai X, Cui P, Chen Q, Lou Y, Zou L, Li S, Zhou Z, Zhang C, Sun P, Mao M. Global Epidemiology of Gallstones in the 21st Century: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;22:1586–1595. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2024.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Unalp-Arida A, Ruhl CE. Increasing gallstone disease prevalence and associations with gallbladder and biliary tract mortality in the US. Hepatology. 2023;77:1882–1895. doi: 10.1097/HEP.0000000000000264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Binda C, Gibiino G, Coluccio C, Sbrancia M, Dajti E, Sinagra E, Capurso G, Sambri V, Cucchetti A, Ercolani G, Fabbri C. Biliary Diseases from the Microbiome Perspective: How Microorganisms Could Change the Approach to Benign and Malignant Diseases. Microorganisms. 2022;10 doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10020312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maki T. Pathogenesis of calcium bilirubinate gallstone: role of E. coli, beta-glucuronidase and coagulation by inorganic ions, polyelectrolytes and agitation. Ann Surg. 1966;164:90–100. doi: 10.1097/00000658-196607000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guo RX, He SG, Shen K. The bacteriology of cholelithiasis--China versus Japan. Jpn J Surg. 1991;21:606–612. doi: 10.1007/BF02471044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carey MC. Pathogenesis of gallstones. Recenti Prog Med. 1992;83:379–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stewart L, Smith AL, Pellegrini CA, Motson RW, Way LW. Pigment gallstones form as a composite of bacterial microcolonies and pigment solids. Ann Surg. 1987;206:242–250. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198709000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swidsinski A, Lee SP. The role of bacteria in gallstone pathogenesis. Front Biosci. 2001;6:E93–103. doi: 10.2741/swidsinski. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lanas A, Chan FKL. Peptic ulcer disease. Lancet. 2017;390:613–624. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32404-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang F, Meng W, Wang B, Qiao L. Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric inflammation and gastric cancer. Cancer Lett. 2014;345:196–202. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ren S, Cai P, Liu Y, Wang T, Zhang Y, Li Q, Gu Y, Wei L, Yan C, Jin G. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;37:464–470. doi: 10.1111/jgh.15751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Azimirad M, Sadeghi A, Hosseinkhan N, Mirbagheri SZ, Alebouyeh M. Microbiome analysis of bile samples in patients with choledocholithiasis and hepatobiliary disorders. Germs. 2023;13:238–253. doi: 10.18683/germs.2023.1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kucuk S, Küçük İG. The relationship between Helicobacter pylori and gallbladder pathologies, dysplasia and gallbladder cancer. Acta Medica Mediterr. 2021;37:2613. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee JW, Lee DH, Lee JI, Jeong S, Kwon KS, Kim HG, Shin YW, Kim YS, Choi MS, Song SY. Identification of Helicobacter pylori in Gallstone, Bile, and Other Hepatobiliary Tissues of Patients with Cholecystitis. Gut Liver. 2010;4:60–67. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2010.4.1.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cen L, Wu J, Zhu S, Pan J, Zhou T, Yan T, Shen Z, Yu C. The potential bidirectional association between Helicobacter pylori infection and gallstone disease in adults: A two-cohort study. Eur J Clin Invest. 2023;53:e13879. doi: 10.1111/eci.13879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang J, Zhang Y, Chen Y, Chen W, Xu H, Sun W. Helicobacter pylori is not a contributing factor in gallbladder polyps or gallstones: a case-control matching study of Chinese individuals. J Int Med Res. 2020;48:300060520959220. doi: 10.1177/0300060520959220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sengupta S, Modak P, McCauley N, O'Donnell LJ. Effect of oral clarithromycin on gall-bladder motility in normal subjects and those with gall-stones. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:95–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02962.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gravina AG, Pellegrino R, Auletta S, Palladino G, Brandimarte G, D'Onofrio R, Arboretto G, Imperio G, Ventura A, Cipullo M, Romano M, Federico A. Hericium erinaceus, a medicinal fungus with a centuries-old history: Evidence in gastrointestinal diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2023;29:3048–3065. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v29.i20.3048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu P, Pan X, Chen M, Ma J, Xu B, Zhao Y. Ultrasound-assisted enzymatic extraction of soluble dietary Fiber from Hericium erinaceus and its in vitro lipid-lowering effect. Food Chem X. 2024;23:101657. doi: 10.1016/j.fochx.2024.101657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370:1453–1457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264–269, W64. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Slim K, Nini E, Forestier D, Kwiatkowski F, Panis Y, Chipponi J. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (minors): development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J Surg. 2003;73:712–716. doi: 10.1046/j.1445-2197.2003.02748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balduzzi S, Rücker G, Schwarzer G. How to perform a meta-analysis with R: a practical tutorial. Evid Based Ment Health. 2019;22:153–160. doi: 10.1136/ebmental-2019-300117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Veroniki AA, McKenzie JE. A brief note on the common (fixed)-effect meta-analysis model. J Clin Epidemiol. 2024;169:111281. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2024.111281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peters JL, Sutton AJ, Jones DR, Abrams KR, Rushton L. Comparison of two methods to detect publication bias in meta-analysis. JAMA. 2006;295:676–680. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.6.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murphy MC, Gibney B, Gillespie C, Hynes J, Bolster F. Gallstones top to toe: what the radiologist needs to know. Insights Imaging. 2020;11:13. doi: 10.1186/s13244-019-0825-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roubaud Baudron C, Franceschi F, Salles N, Gasbarrini A. Extragastric diseases and Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter. 2013;18 Suppl 1:44–51. doi: 10.1111/hel.12077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Poster. J Dig Dis. 2016;17 Suppl 1:13–112. doi: 10.1111/1751-2980.12389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ninomiya R, Kubo S, Baba T, Kajiwara T, Tokunaga A, Nabeka H, Doihara T, Shimokawa T, Matsuda S, Murakami K, Aigaki T, Yamaoka Y, Hamada F. Inhibition of low-density lipoprotein uptake by Helicobacter pylori virulence factor CagA. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2021;556:192–198. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2021.03.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tazuma S, Kanno K, Sugiyama A, Kishikawa N. Nutritional factors (nutritional aspects) in biliary disorders: bile acid and lipid metabolism in gallstone diseases and pancreaticobiliary maljunction. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28 Suppl 4:103–107. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Atamanalp SS, Keles MS, Atamanalp RS, Acemoglu H, Laloglu E. The effects of serum cholesterol, LDL, and HDL levels on gallstone cholesterol concentration. Pak J Med Sci. 2013;29:187–190. doi: 10.12669/pjms.291.2798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou D, Guan WB, Wang JD, Zhang Y, Gong W, Quan ZW. A comparative study of clinicopathological features between chronic cholecystitis patients with and without Helicobacter pylori infection in gallbladder mucosa. PLoS One. 2013;8:e70265. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sipos P, Krisztina H, Blázovics A, Fehér J. Cholecystitis, gallstones and free radical reactions in human gallbladder. Med Sci Monit. 2001;7:84–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Belzer C, Kusters JG, Kuipers EJ, van Vliet AH. Urease induced calcium precipitation by Helicobacter species may initiate gallstone formation. Gut. 2006;55:1678–1679. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.098319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stathopoulos P, Zundt B, Spelsberg FW, Kolligs L, Diebold J, Goke B, Jungst D. Relation of gallbladder function and Helicobacter pylori infection to gastric mucosa inflammation in patients with symptomatic cholecystolithiasis. Digestion. 2006;73:69–74. doi: 10.1159/000092746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boonyanugomol W, Chomvarin C, Sripa B, Chau-In S, Pugkhem A, Namwat W, Wongboot W, Khampoosa B. Molecular analysis of Helicobacter pylori virulent-associated genes in hepatobiliary patients. HPB (Oxford) 2012;14:754–763. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2012.00533.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eusebi LH, Zagari RM, Bazzoli F. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2014;19 Suppl 1:1–5. doi: 10.1111/hel.12165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pellicano R, Ménard A, Rizzetto M, Mégraud F. Helicobacter species and liver diseases: association or causation? Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:254–260. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70066-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bulajic M, Maisonneuve P, Schneider-Brachert W, Müller P, Reischl U, Stimec B, Lehn N, Lowenfels AB, Löhr M. Helicobacter pylori and the risk of benign and malignant biliary tract disease. Cancer. 2002;95:1946–1953. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Monstein HJ, Jonsson Y, Zdolsek J, Svanvik J. Identification of Helicobacter pylori DNA in human cholesterol gallstones. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:112–119. doi: 10.1080/003655202753387455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boonyanugomol W, Khuntikeo N, Pugkhem A, Sawadpanich K, Hahnvajanawong C, Wongphutorn P, Khampoosa B, Chomvarin C. Genetic characterization of Helicobacter pylori vacA and cagA genes in Thai gastro-duodenal and hepatobiliary patients. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2017;11:42–50. doi: 10.3855/jidc.8126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kafeel A, Bashir J, Khan IA, Bawany MA, Rashid MJ, Ara J. Assessment of the Simultaneous Presence of Helicobacter Pylori in the Gastric Mucosa and Gallbladder Mucosa in Patients Suffering from Cholecystitis: a cross Sectional Study. Pak J Med Health Sci. 2022;16:627–629. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cen L, Pan J, Zhou B, Yu C, Li Y, Chen W, Shen Z. Helicobacter Pylori infection of the gallbladder and the risk of chronic cholecystitis and cholelithiasis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Helicobacter. 2018;23 doi: 10.1111/hel.12457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang L, Chen J, Jiang W, Cen L, Pan J, Yu C, Li Y, Chen W, Chen C, Shen Z. The Relationship between Helicobacter pylori Infection of the Gallbladder and Chronic Cholecystitis and Cholelithiasis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;2021:8886085. doi: 10.1155/2021/8886085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhou D, Zhang Y, Gong W, Mohamed SO, Ogbomo H, Wang X, Liu Y, Quan Z. Are Helicobacter pylori and other Helicobacter species infection associated with human biliary lithiasis? A meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27390. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Takahashi Y, Yamamichi N, Shimamoto T, Mochizuki S, Fujishiro M, Takeuchi C, Sakaguchi Y, Niimi K, Ono S, Kodashima S, Mitsushima T, Koike K. Helicobacter pylori infection is positively associated with gallstones: a large-scale cross-sectional study in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:882–889. doi: 10.1007/s00535-013-0832-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shirah BH, Shirah HA, Zafar SH, Albeladi KB. Clinical patterns of postcholecystectomy syndrome. Ann Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2018;22:52–57. doi: 10.14701/ahbps.2018.22.1.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kapadia SG, Kaji AH, Hari DM, Ozao-Choy J, Chen KT. Surgical referral for cholecystectomy in patients with atypical symptoms. Am J Surg. 2020;220:1451–1455. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2020.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kapadia S, Kaji AH, Hari DM, Ozao-Choy J, Chen KT. Helicobacter pylori and Gallstone Disease: Incidence and Outcomes in a Los Angeles County Population. J Gastrointest Surg. 2021;25:887–889. doi: 10.1007/s11605-021-04918-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Loosen SH, Killer A, Luedde T, Roderburg C, Kostev K. Helicobacter pylori infection associated with an increased incidence of cholelithiasis: A retrospective real-world cohort study of 50 832 patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024 doi: 10.1111/jgh.16597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sermet M. Association between gastric abnormalities and cholelithiasis: A cross-sectional study. Ann Clin Anal Med. 2024;15 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hashimoto K, Nagao Y, Nambara S, Tsuda Y, Kudou K, Kusumoto E, Sakaguchi Y, Kusumoto T, Ikejiri K. Association Between Anti-Helicobacter pylori Antibody Seropositive and De Novo Gallstone Formation After Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy for Japanese Patients with Severe Obesity. Obes Surg. 2022;32:3404–3409. doi: 10.1007/s11695-022-06253-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Higashizono K, Nakatani E, Hawke P, Fujimoto S, Oba N. Risk factors for gallstone disease onset in Japan: Findings from the Shizuoka Study, a population-based cohort study. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0274659. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0274659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jahantab MB, Safaripour AA, Hassanzadeh S, Yavari Barhaghtalab MJ. Demographic, Chemical, and Helicobacter pylori Positivity Assessment in Different Types of Gallstones and the Bile in a Random Sample of Cholecystectomied Iranian Patients with Cholelithiasis. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;2021:3351352. doi: 10.1155/2021/3351352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ari A, Tatar C, Yarikkaya E. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori-positivity in the gallbladder and stomach and effect on gallbladder pathologies. J Int Med Res. 2019;47:4904–4910. doi: 10.1177/0300060519847345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cherif S, Rais H, Hakmaoui A, Sellami S, Elantri S, Amine A. Linking Helicobacter pylori with gallbladder and biliary tract cancer in Moroccan population using clinical and pathological profiles. Bioinformation. 2019;15:735–743. doi: 10.6026/97320630015735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kerawala AA, Bakhtiar N, Abidi SS, Awan S. Association of gallstone and helicobacter pylori. J Med Sci (Peshawar) 2019;27:269–272. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fatemi SM, Doosti A, Shokri D, Ghorbani-Dalini S, Molazadeh M, Tavakoli H, Minakari M, Tavakkoli H. Is There a Correlation between Helicobacter Pylori and Enterohepatic Helicobacter Species and Gallstone Cholecystitis? Middle East J Dig Dis. 2018;10:24–30. doi: 10.15171/mejdd.2017.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xu MY, Ma JH, Yuan BS, Yin J, Liu L, Lu QB. Association between Helicobacter pylori infection and gallbladder diseases: A retrospective study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;33:1207–1212. doi: 10.1111/jgh.14054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Seyyedmajidi M, Hosseini SA, Hajiebrahimi S, Ahmadi A, Banikarim S, Zanganeh E, Seyedmajidi S. Companion of Helicobacter Pylori Presence in Stomach and Biliary Tract in the Patients with Biliary Stones. International J Adv Biotechnology Res. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 65.Choi YS, Do JH, Seo SW, Lee SE, Oh HC, Min YJ, Kang H. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Gallbladder Polypoid Lesions in a Healthy Population. Yonsei Med J. 2016;57:1370–1375. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2016.57.6.1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dar MY, Ali S, Raina AH, Raina MA, Shah OJ, Shah MA, Mudassar S. Association of Helicobacter pylori with hepatobiliary stone disease, a prospective case control study. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2016;35:343–346. doi: 10.1007/s12664-016-0675-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Patnayak R, Reddy V, Jena A, Gavini S, Thota A, Nandyala R, Chowhan AK. Helicobacter pylori in Cholecystectomy Specimens-Morphological and Immunohistochemical Assessment. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:EC01–EC03. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/14802.7716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tajeddin E, Sherafat SJ, Majidi MR, Alebouyeh M, Alizadeh AH, Zali MR. Association of diverse bacterial communities in human bile samples with biliary tract disorders: a survey using culture and polymerase chain reaction-denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis methods. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;35:1331–1339. doi: 10.1007/s10096-016-2669-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Guraya SY, Ahmad AA, El-Ageery SM, Hemeg HA, Ozbak HA, Yousef K, Abdel-Aziz NA. The correlation of Helicobacter Pylori with the development of cholelithiasis and cholecystitis: the results of a prospective clinical study in Saudi Arabia. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2015;19:3873–3880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang FM, Yu CH, Chen HT, Shen Z, Hu FL, Yuan XP, Xu GQ. Helicobacter pylori infection is associated with gallstones: Epidemiological survey in China. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:8912–8919. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i29.8912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Murphy G, Michel A, Taylor PR, Albanes D, Weinstein SJ, Virtamo J, Parisi D, Snyder K, Butt J, McGlynn KA, Koshiol J, Pawlita M, Lai GY, Abnet CC, Dawsey SM, Freedman ND. Association of seropositivity to Helicobacter species and biliary tract cancer in the ATBC study. Hepatology. 2014;60:1963–1971. doi: 10.1002/hep.27193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Boonyanugomol W, Chomvarin C, Sripa B, Bhudhisawasdi V, Khuntikeo N, Hahnvajanawong C, Chamsuwan A. Helicobacter pylori in Thai patients with cholangiocarcinoma and its association with biliary inflammation and proliferation. HPB (Oxford) 2012;14:177–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2011.00423.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jahani Sherafat S, Tajeddin E, Reza Seyyed Majidi M, Vaziri F, Alebouyeh M, Mohammad Alizadeh AH, Nazemalhosseini Mojarad E, Reza Zali M. Lack of association between Helicobacter pylori infection and biliary tract diseases. Pol J Microbiol. 2012;61:319–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yakoob J, Khan MR, Abbas Z, Jafri W, Azmi R, Ahmad Z, Naeem S, Lubbad L. Helicobacter pylori: association with gall bladder disorders in Pakistan. Br J Biomed Sci. 2011;68:59–64. doi: 10.1080/09674845.2011.11730324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bostanoğlu E, Karahan ZC, Bostanoğlu A, Savaş B, Erden E, Kiyan M. Evaluation of the presence of Helicobacter species in the biliary system of Turkish patients with cholelithiasis. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2010;21:421–427. doi: 10.4318/tjg.2010.0130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Popović N, Nikolić V, Karamarković A, Blagojević Z, Sijacki A, Surbatović M, Ivancević N, Gregorić P, Ilić M. Prospective evaluation of the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in abdominal surgery patients. Hepatogastroenterology. 2010;57:167–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Griniatsos J, Sougioultzis S, Giaslakiotis K, Gazouli M, Prassas E, Felekouras E, Michail O, Avgerinos E, Pikoulis E, Kouraklis G, Delladetsima I, Tzivras M. Does Helicobacter pylori identification in the mucosa of the gallbladder correlate with cholesterol gallstone formation? West Indian Med J. 2009;58:428–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yucebilgili K, Mehmetoĝlu T, Gucin Z, Salih BA. Helicobacter pylori DNA in gallbladder tissue of patients with cholelithiasis and cholecystitis. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2009;3:856–859. doi: 10.3855/jidc.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Misra V, Misra SP, Dwivedi M, Shouche Y, Dharne M, Singh PA. Helicobacter pylori in areas of gastric metaplasia in the gallbladder and isolation of H. pylori DNA from gallstones. Pathology. 2007;39:419–424. doi: 10.1080/00313020701444473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Abayli B, Colakoglu S, Serin M, Erdogan S, Isiksal YF, Tuncer I, Koksal F, Demiryurek H. Helicobacter pylori in the etiology of cholesterol gallstones. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:134–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kobayashi T, Harada K, Miwa K, Nakanuma Y. Helicobacter genus DNA fragments are commonly detectable in bile from patients with extrahepatic biliary diseases and associated with their pathogenesis. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:862–867. doi: 10.1007/s10620-005-2654-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Farshad Sh, Alborzi A, Malek Hosseini SA, Oboodi B, Rasouli M, Japoni A, Nasiri J. Identification of Helicobacter pylori DNA in Iranian patients with gallstones. Epidemiol Infect. 2004;132:1185–1189. doi: 10.1017/s0950268804002985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chen W, Li D, Cannan RJ, Stubbs RS. Common presence of Helicobacter DNA in the gallbladder of patients with gallstone diseases and controls. Dig Liver Dis. 2003;35:237–243. doi: 10.1016/s1590-8658(03)00060-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Silva CP, Pereira-Lima JC, Oliveira AG, Guerra JB, Marques DL, Sarmanho L, Cabral MM, Queiroz DM. Association of the presence of Helicobacter in gallbladder tissue with cholelithiasis and cholecystitis. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:5615–5618. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.12.5615-5618.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bulajic M, Stimec B, Milicevic M, Loehr M, Mueller P, Boricic I, Kovacevic N, Bulajic M. Modalities of testing Helicobacter pylori in patients with nonmalignant bile duct diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2002;8:301–304. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v8.i2.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Fukuda K, Kuroki T, Tajima Y, Tsuneoka N, Kitajima T, Matsuzaki S, Furui J, Kanematsu T. Comparative analysis of Helicobacter DNAs and biliary pathology in patients with and without hepatobiliary cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:1927–1931. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.11.1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Harada K, Ozaki S, Kono N, Tsuneyama K, Katayanagi K, Hiramatsu K, Nakanuma Y. Frequent molecular identification of Campylobacter but not Helicobacter genus in bile and biliary epithelium in hepatolithiasis. J Pathol. 2001;193:218–223. doi: 10.1002/1096-9896(2000)9999:9999<::AID-PATH776>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Myung SJ, Kim MH, Shim KN, Kim YS, Kim EO, Kim HJ, Park ET, Yoo KS, Lim BC, Seo DW, Lee SK, Min YI, Kim JY. Detection of Helicobacter pylori DNA in human biliary tree and its association with hepatolithiasis. Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45:1405–1412. doi: 10.1023/a:1005572507572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Roe IH, Kim JT, Lee HS, Lee JH. Detection of Helicobacter DNA in bile from bile duct diseases. J Korean Med Sci. 1999;14:182–186. doi: 10.3346/jkms.1999.14.2.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Figura N, Cetta F, Angelico M, Montalto G, Cetta D, Pacenti L, Vindigni C, Vaira D, Festuccia F, De Santis A, Rattan G, Giannace R, Campagna S, Gennari C. Most Helicobacter pylori-infected patients have specific antibodies, and some also have H. pylori antigens and genomic material in bile: is it a risk factor for gallstone formation? Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:854–862. doi: 10.1023/a:1018838719590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kochhar R, Malik AK, Nijhawan R, Goenka MK, Mehta SK. H. pylori in postcholecystectomy symptoms. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1993;17:269–270. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199310000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kellosalo J, Alavaikko M, Laitinen S. Effect of biliary tract procedures on duodenogastric reflux and the gastric mucosa. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1991;26:1272–1278. doi: 10.3109/00365529108998624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.