HIGHLIGHTS

-

•

Using survey data from North Carolina, the authors described the Medicaid expansion population.

-

•

The newly eligible population had numerous unmet preventive healthcare needs.

-

•

The authors estimated 186,000 newly eligible individuals without a regular source of care.

-

•

There were also gaps in the use of wellness visits, dental care, and cancer screening.

-

•

Transitions to Medicaid can serve as an opportunity to address preventive care needs.

Keywords: Medicaid, preventive care, underserved populations, cancer screening, primary care

Abstract

Introduction

Effective December 2023, North Carolina expanded Medicaid eligibility to cover individuals up to 138% of the Federal Poverty Level. The authors sought to understand the preventive care needs of the newly Medicaid-eligible population.

Methods

The authors conducted a repeat cross-sectional analysis using the 2016, 2018, 2020, and 2022 North Carolina Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey. The authors defined the Medicaid expansion population as those aged 18–64 years with household incomes below 138% Federal Poverty Level and reporting no current source of insurance. The authors compared with those enrolled in traditional Medicaid and all nonelderly adult North Carolinians, evaluating up-to-date use of preventive care services. Survey weights were used to estimate total unmet need.

Results

The authors estimated 294,000 individuals in the Medicaid expansion population in 2022. Preventive care use was low for the expansion population in all years. In 2022, 36.7% (27.7%–46.8%) reported having a regular source of care, 40.2% (31.1%–50%) reported a past-year wellness visit, and 45.7% (36.6%–55.2%) reported delaying needed care owing to cost. Among eligible respondents, 28.6% (13.8%–50.2%) were up to date with colorectal cancer screening (vs 49.4% [30.5%–68.4%] for traditional Medicaid and 71% [67.3%–74.4%] for all North Carolina population). It was estimated that 176,000 in the expansion population needed a wellness visit; 186,000 needed a regular care provider; and 66,000 needed 1 or more cancer screening.

Conclusions

The North Carolina Medicaid expansion population has a high number of unmet preventive care needs. North Carolina should consider approaches to improve provider capacity for those in Medicaid and promote preventive care and risk reduction for the newly enrolled expansion population.

INTRODUCTION

In 2023, North Carolina became the 40th state to expand eligibility of its Medicaid program to cover all low-income adults up to 138% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL). This will expand Medicaid eligibility to as many as 600,000 individuals,1 many of whom were in what is known as the Medicaid gap, with incomes too low to qualify for premium subsidies but not meeting categorical criteria for Medicaid.2 Prior work has demonstrated that this population, without affordable options for health insurance, is less likely to receive routine and preventive care services.3

In states that have expanded Medicaid, evidence suggests increases in insurance and the use of preventive services, particularly among low-income individuals.4 Improvements in care use have been particularly strong for cancer screening, which shows both an overall increase and some reductions in racial disparities after the expansion of state Medicaid programs.3,5,6 There are concerns about whether system capacity can meet the needs of the newly insured,7 but some promising data in early-expansion states showed no substantial changes in wait times or primary care appointment availability after expansion.8,9 Concerns remain for health system capacity in states that were later to expand such as North Carolina, particularly in rural areas and other areas of high need, given existing challenges meeting primary care demand in the state.10

Prior work demonstrated low use of many preventive services among those in the potential Medicaid expansion population,11 but numerous changes may have affected this population in recent years. Notably, isolation recommendations during the first waves of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in 2020 resulted in delays in nonemergent and preventive services. The pandemic also resulted in changes to eligibility and re-enrollment requirements for numerous government support programs, including Medicaid.12 Continuous eligibility for Medicaid lasted through the end of the public health emergency, with redeterminations beginning in April 2023 and disenrollments beginning in July, including an estimated 200,000 individuals in North Carolina.13, 14, 15 Because more than a half million North Carolinians become newly eligible for the Medicaid program, it is important to understand the nature and extent of unmet needs faced by the population. The authors sought to assess the demographic characteristics and preventive health services needs of the North Carolina Medicaid expansion population in the years leading up to the expansion of its Medicaid program.

METHODS

Data on North Carolina from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey for 2016, 2018, 2020, and 2022 were provided by the North Carolina Center for Health Statistics.16 Use of multiple years of data and a repeat cross-sectional design allowed us to evaluate trends over time and understand the potential role of the COVID-19 pandemic and pandemic-related changes to eligibility on the Medicaid expansion population.

Study Population

The authors compared populations using self-reported data on income, household size, and insurance status at the time of the interview. Household incomes were provided as a range; the authors compared the median of this range with FPL by household size.17 Those uninsured and with incomes <138% FPL were identified as the Medicaid expansion population. Those reporting Medicaid insurance were designated traditional Medicaid. These groups were also compared with the full nonelderly adult North Carolina population (all NC). Those declining to report income (∼22% of respondents) were excluded for estimates of the expansion population but included in estimates for traditional Medicaid and all NC.

Measures

Included sociodemographic characteristics were age, sex, Hispanic ethnicity, and race. Participants could self-report their race as White only, Black/African American only, Asian only, and American Indian/Alaskan Native only in all years. Across years, the grouping of multiple races, another race not listed, and missing was inconsistent; the authors combined these as a single category. The authors compared those married or living with a long-term partner with those who were divorced, separated, or widowed and those who report never being married. Employment status was defined as those who reported any full-time or part-time employment versus those who are out of work, those who were homemakers, those who were students, those who were retired, and those unable to work. The authors evaluated metrics of overall health, including general health status (excellent or very good versus good, fair, or poor) and number of chronic conditions as previously described11 (none vs 1 vs 2 or more). The authors also measured functional disability as those who reported any of the following: being blind, being deaf, having difficulty walking, having difficulty dressing themselves or performing activities of daily living, being unable to live alone, or having difficulty concentrating or making decisions.

Preventive care measures included any wellness visit in the past year, reporting a regular place one could go for health care, having delayed or forgone care in the past year due to cost, any dental care visits in the past year, and a seasonal flu vaccine in the past year. To assess health risk behaviors that are potentially addressable through primary care, the authors assessed the proportion of respondents who reported ever smoking, currently smoking, or any binge drinking in the past month (>4 drinks in 1 sitting for women and >5 drinks for men). To assess cancer screening usage, respondents age and sex eligible for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screening were compared with U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommendations for up-to-date screening for each.18, 19, 20 Owing to changes in cervical cancer screening questions, the authors evaluated these data only through 2020. Lung cancer screening was only included in 2022; the authors assessed the proportion of respondents meeting the USPSTF recommendations for lung cancer screening (including 20 pack-year history and being aged 50–80 years)21 as well as the fraction who reported ever receiving a screen. Owing to small sample size, the authors reported the latter measure only for the full North Carolina data.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed in R, Version 4.3.1.22 BRFSS data were deidentified; therefore, this study was exempted by the IRB. The proportion of respondents reporting each outcome and 95% CIs were calculated using survey-weighted logit model following National Center for Health Statistics recommendations.23 The authors compared each measure with corresponding Healthy People 2030 goals where these existed (Appendix Table 1, available online).24 The authors also estimated the total number of individuals in the Medicaid expansion population with an unmet need for each preventive service overall and stratified for men and women aged 45–64 years, to capture those eligible for all included services. Statistical significance of differences was assessed using a Wald test and an alpha value of 0.05.

RESULTS

The estimated number of uninsured individuals eligible for expanded Medicaid decreased across years, from an estimated 539,000 (approximately 8.7% of nonelderly adults) in 2016 to 294,000 (4.7%) in 2022 (Table 1). This shift resulted from 2 factors; somewhat consistent reductions in the proportion living under 138% FPL (from 22.8% to 18.7%, p<0.001) (Appendix Table 2, available online) and a more abrupt decrease after 2020 in those reporting no insurance coverage (from 18.6% in 2020 to 12.2% in 2022, p<0.001). Most sociodemographic characteristics of the expansion population remained stable. However, there were significant increases in the proportion who identified as Hispanic (from 40.2% in 2016 to 56.4% in 2022; p=0.002). This substantially outpaced the growth in Hispanic population for all NC (Appendix Table 2, available online). There were also small decreases in the proportion identifying their race as White only (from 48.4% to 40.8%) or Black only (from 23.3% to 19.4%; p=0.008) with increases in the combined other, missing, or multiple race category.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Medicaid Expansion Population, 2016–2022

| Categories | 2016 | 2018 | 2020 | 2022 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 372 | 271 | 307 | 164 | |

| Estimated population | 539,026 | 478,473 | 475,270 | 294,473 | |

| Age, years | |||||

| 18–24 | 13.6% (32) | 12.9% (25) | 12.2% (28) | 12.3% (13) | |

| 25–34 | 30.5% (96) | 34.4% (76) | 30.8% (78) | 39.4% (56) | |

| 35–44 | 27.5% (106) | 21.1% (64) | 28.3% (92) | 20.8% (42) | |

| 45–54 | 20.3% (97) | 20.5% (67) | 17.9% (69) | 15.8% (34) | |

| 55–64 | 8.1% (41) | 11.1% (39) | 10.8% (40) | 11.7% (19) | 0.64 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 53.2% (195) | 46.3% (128) | 52.9% (155) | 58.4% (92) | |

| Female | 46.7% (176) | 53.7% (143) | 47.1% (152) | 41.6% (72) | |

| Missing | 0.1% (1) | 0 (-) | 0 (-) | 0 (-) | 0.47 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | |||||

| Hispanic | 40.2% (171) | 44.8% (125) | 36.2% (136) | 56.4% (103) | |

| Non-Hispanic | 58.9% (199) | 55.2% (146) | 63.8% (171) | 43.6% (61) | |

| Missing | 0.9% (2) | 0 (—) | 0 (—) | 0 (—) | 0.002 |

| Race | |||||

| White only | 48.4% (177) | 37.5% (106) | 41.3% (121) | 40.8% (65) | |

| Black/African American only | 23.3% (75) | 27.3% (69) | 23.9% (53) | 19.4% (23) | |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native only | 3.3% (11) | 3.7% (11) | 4.4% (23) | 3.6% (10) | |

| Asian only | 2.1% (4) | 0 (—) | 0.6% (1) | 1.6% (2) | |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 0 (—) | 0.5% (1) | 0.4% (2) | 0.7% (1) | |

| Other/multirace/missing | 22.9% (105) | 31.1% (84) | 29.4% (107) | 33.9% (63) | 0.008 |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married/long-term partnered | 45.4% (173) | 50.2% (129) | 45.3% (140) | 53.7% (95) | |

| Divorce/widowed/separated | 21.8% (91) | 18.6% (68) | 24.1% (81) | 20.7% (36) | |

| Never married | 32.5% (107) | 31.2% (74) | 29.9% (85) | 25.6% (33) | |

| Missing | 0.3% (1) | 0 (—) | 0.6% (1) | 0 (—) | 0.4 |

| Education | |||||

| Less than high school | 41.5% (141) | 37.4% (97) | 39.3% (106) | 47% (69) | |

| High school/GED | 34.4% (136) | 32.6% (95) | 29.7% (112) | 35.4% (59) | |

| Some college | 21.6% (79) | 26.4% (62) | 25.7% (61) | 11.9% (20) | |

| College+ | 2.5% (16) | 3.6% (17) | 5.1% (26) | 5% (14) | |

| Missing | 0 (—) | 0 (—) | 0.2% (2) | 0.7% (2) | 0.06 |

| Employment | |||||

| Employed | 55.8% (212) | 55.7% (162) | 54.5% (179) | 59.1% (103) | |

| Out of work | 17% (64) | 16.1% (39) | 21.6% (61) | 17% (25) | |

| Homemaker | 9.6% (38) | 13.7% (31) | 11.4% (33) | 12.6% (18) | |

| Student | 3.9% (14) | 4.9% (8) | 2.4% (5) | 0.7% (1) | |

| Retired | 0.7% (6) | 1.9% (7) | 0.8% (5) | 1.3% (3) | |

| Unable to Work | 12.3% (35) | 7.4% (23) | 9% (23) | 8.7% (13) | |

| Missing | 0.6% (3) | 0.2% (1) | 0.3% (1) | 0.7% (1) | 0.83 |

| Children | |||||

| No children | 42.4% (167) | 42.5% (124) | 42.5% (136) | 39.2% (59) | |

| 1 child | 14.9% (58) | 15.7% (46) | 18.7% (50) | 20.9% (33) | |

| 2 children | 20.3% (72) | 18.9% (52) | 21.2% (61) | 18.4% (32) | |

| ≥3 children | 22.4% (75) | 22.9% (49) | 17.5% (60) | 21.6% (40) | 0.72 |

| Health status | |||||

| Poor/fair/good | 69.7% (257) | 68.4% (187) | 60% (179) | 69.2% (110) | |

| Excellent/very good | 30.1% (114) | 30.3% (80) | 39.9% (127) | 30.5% (52) | |

| Missing | 0.1% (1) | 1.3% (4) | 0.2% (1) | 0.3% (2) | 0.01 |

| Chronic conditions | |||||

| 0 | 55.6% (199) | 51.1% (131) | 53.8% (162) | 61.8% (94) | |

| 1 | 22.6% (86) | 26.1% (67) | 25.7% (79) | 18% (31) | |

| ≥2 | 18.2% (71) | 19.2% (61) | 16.8% (55) | 15% (30) | |

| Missing | 3.7% (16) | 3.6% (12) | 3.7% (11) | 5.1% (9) | 0.67 |

| Functional disability | |||||

| Yes | 35.4% (121) | 38.5% (107) | 30.7% (83) | 35.2% (58) | |

| No | 62.2% (241) | 59.6% (159) | 68% (218) | 64.8% (106) | |

| Missing | 2.4% (10) | 1.9% (5) | 1.3% (6) | 0 (—) | 0.02 |

| CC screen eligible | |||||

| Yes | 40.2% (158) | 52.1% (141) | 43.9% (142) | 38.4% (68) | |

| BC screening eligible | |||||

| Yes | 7.2% (35) | 15.3% (48) | 10.5% (40) | 7.8% (16) | |

| CRC screening eligible | |||||

| Yes | 14.8% (78) | 23.6% (75) | 21.3% (70) | 24.6% (49) |

Note: Data are from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey 2016, 2018, 2020, and 2022.

BC, breast cancer; CC, cervical cancer; CRC, colorectal cancer; GED, General Education Degree.

The Medicaid expansion population was notably different from both all NC (Appendix Table 2, available online) and the traditional Medicaid population (Appendix Table 3, available online). In 2022, those in the Medicaid expansion population were more likely to identify as Hispanic (56.4% vs 11.6% traditional Medicaid and 11.5% all NC). The expansion population was also more likely to report having less than a high school education (47%) than either the traditional Medicaid population (25.1%) or all NC (11.2%). Those in the expansion population were slightly less likely to be employed than all NC (59.1% vs 69.8%) but were much more likely to be employed than those in traditional Medicaid (39.3%).

Those in the traditional Medicaid were more likely to report a functional disability (45.2% vs 35.2% for Medicaid expansion and 21.3% for All NC) as well as more likely to have multiple chronic conditions. Despite this, those in the expansion population were less likely to have excellent or very good health overall (30.5%) than those in either traditional Medicaid (43.1%) or all NC (54.5%).

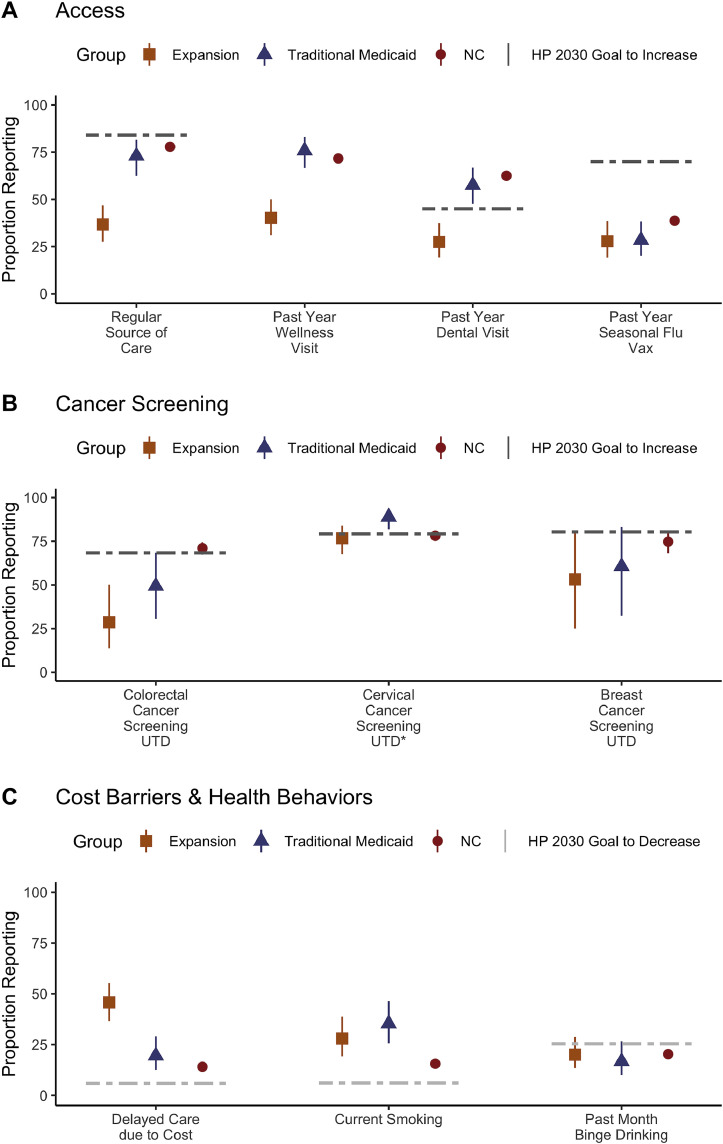

Compared with those in traditional Medicaid, all NC, and Healthy People 2030 goals, those in the Medicaid expansion population reported low access to and use of health care by multiple measures in 2022 (Figure 1A), which was similar across years (Appendix Table 4, available online). In 2022, (40.2% [95% CI=31.1%, 50%]) of the Medicaid expansion population reported a past year wellness visits compared with 75.8% (95% CI=66.6%, 83.1%) of traditional Medicaid and 71.6% (95% CI=69.5%, 73.7%) of all NC. Findings are similar for a regular source of care, with 36.7% (95% CI=27.7%, 46.8%) of the expansion population reporting a regular source of care compared with 73% (95% CI=62.4%, 81.5%) of traditional Medicaid. A total of 27.5% (95% CI=19.3%, 37.5%) of the expansion population and 57.5% (95% CI=47.6%, 66.8%) of traditional Medicaid reported a past-year dental visit. Seasonal flu vaccination was fairly low for all groups, with no significant differences in coverage. Finally, those in the Medicaid expansion population are more than twice as likely to have delayed or declined needed care (Figure 1C) in the past year owing to cost (45.7% [95% CI=36.6%, 55.2%] vs 19.5% [95% CI=12.6%, 29%] for traditional Medicaid and 14.1% [95% CI=12.5%, 15.7%] for all NC).

Figure 1.

Describes care access (A), cancer screening use (B), cost barriers and health behaviors (C) in North Carolina by Medicaid Status in 2022.

Dashed lines indicate Healthy People 2030 goals; no goal is provided for adult wellness visits. NC, North Carolina.

Cancer Screening

The Medicaid expansion population was below Healthy People 2030 targets for both breast and colorectal cancer screening (Figure 1B). Breast cancer screening in Medicaid expansion population was 53.2% (95% CI=25.1%, 79.4%) in 2022 (Table 2) and not significantly different from coverage for either traditional Medicaid or all NC. Up-to-date cervical cancer screening was fairly high for all groups, although some decline was seen across years with coverage in the expansion population at 84.2% (95% CI=74.8%, 90.6%) in 2016 and 76.7% (95% CI=67.6%, 83.8%) in 2020. Up-to-date colorectal cancer screening was significantly lower in the Medicaid expansion population than in the NC population across all years (2022: 28.6% [95% CI=13.8%, 50.2%] vs 71% [95% CI=67.3%, 74.4%]). Finally, lung cancer screening is only captured in data from 2022. For nonelderly North Carolinians, approximately 4.5% (95% CI=3.6%, 5.6%) were eligible for lung cancer screening on the basis of age and smoking history, similar to that of the Medicaid expansion population. Among those for who screening was recommended, use was low (all NC: 30.8% [95% CI=19.8%, 44.4%]).

Table 2.

Health Risk Behaviors, by Group

| Group | 2016 | 2018 | 2020 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ever smoker | ||||

| Medicaid expansion | 42.1 (35.8, 48.6) | 48.4 (41, 55.8) | 53.6 (46.4, 60.6) | 40.6 (31.2, 50.7) |

| Traditional Medicaid | 62.5 (54.6, 69.8) | 56.1 (46.5, 65.3) | 54.9 (45.1, 64.2) | 46.0 (35.9, 56.4) |

| All NC (aged 18–64 years) | 41.1 (39.4, 42.9) | 40.2 (38.1, 42.3) | 37.5 (35.7, 39.4) | 35.8 (33.6, 38.1) |

| Current smoker | ||||

| Medicaid expansion | 29.5 (23.9, 35.9) | 27.5 (21.4, 34.5) | 37.2 (30.1 44.9) | 28.0 (19.2, 38.8) |

| Traditional Medicaid | 43.2 (35.6, 51.2) | 35.9 (27.3, 45.6) | 42.5 (33.3, 52.2) | 35.3 (25.6, 46.4) |

| All NC (aged 18–64 years) | 20.3 (18.9, 21.8) | 18.8 (17.2, 20.5) | 18.2 (16.8, 19.8) | 15.6 (13.8, 17.5) |

| Binge drinking | ||||

| Medicaid expansion | 20.7 (15.3, 27.5) | 18.5 (13.3, 25.2) | 19.0 (13.9, 25.4) | 20.1 (13.5, 28.8) |

| Traditional Medicaid | 12.3 (8.0, 18.4) | 7.1 (3.5, 14.1) | 16.3 (10.6, 24.3) | 16.7 (10, 26.6) |

| All NC (aged 18–64 years) | 17.7 (16.3, 19.2) | 17.5 (15.8, 19.2) | 16.9 (15.5, 18.4) | 20.3 (18.5, 22.2) |

Note: All values are given in percentage (%) with 95% CIs in parentheses. NC, North Carolina.

Smoking was similar in the expansion and traditional Medicaid populations by 2022 (Table 3 and Figure 1C), with 40.6% (95% CI=31.2%, 50.7%) reporting ever smoking in the expansion population in 2022 (vs 46% [95% CI=35.9%, 56.4%] for traditional Medicaid and 35.8% [95% CI=33.6%, 38.1%] for all NC). However, current smoking was reported roughly twice as often in all years by the expansion population (2022: 28% [95% CI=19.2%, 38.8%]) and traditional Medicaid (35.3% [95% CI=25.6%, 46.4%]) compared with that by all NC (15.6% [95% CI=13.8%, 17.5%]). Any binge drinking during the past month was reported by a fifth of the expansion population (20.1% [95% CI=13.5%, 28.8%]), very similar to the proportion of those in both traditional Medicaid (16.7% [95% CI=10%, 26.6%]) and nonelderly North Carolinians (20.3% [95% CI=18.5%, 22.2%]).

Table 3.

Preventive Care Use, by Group

| Group | 2016 | 2018 | 2020 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Up-to-date breast cancer screening, F, aged 50–64 years | ||||

| Medicaid expansion | 38.5 (19.8, 1.4) | 45.5 (29.4, 62.5) | 60.1 (40.7, 76.8) | 53.2 (25.1, 79.4) |

| Traditional Medicaid | 77.6 (60.6, 88.6) | 82.6 (61.2, 93.5) | 75.1 (54.6, 88.3) | 60.6 (32.4, 83.2) |

| All NC (aged 18–64 years) | 77.4 (74.0, 80.5) | 78 (73.8, 81.6) | 78.5 (74.9, 81.7) | 74.7 (68.1, 80.3) |

| Up-to-date cervical cancer screening, F, aged 21–64 years | ||||

| Medicaid expansion | 84.2 (74.8, 90.6) | 78.3 (69.5, 85.1) | 76.7 (67.6, 83.8) | |

| Traditional Medicaid | 94.0 (87.4, 97.3) | 82.0 (72.3, 88.9) | 88.9 (81.8, 93.5) | |

| All NC (aged 18–64 years) | 91.6 (89.8, 93.1) | 79.4 (76.8, 81.7) | 78.1 (75.7, 80.3) | |

| Up-to-date colorectal cancer screening, M/F, aged 50–64 years | ||||

| Medicaid expansion | 31.1 (19.1, 46.4) | 40.1 (26.3, 55.7) | 44.2 (29.7, 59.7) | 28.6 (13.8, 50.2) |

| Traditional Medicaid | 65.3 (52.6, 76.2) | 63.2 (47.6, 76.4) | 55.0 (36.2, 72.4) | 49.4 (30.5, 68.4) |

| All NC (aged 18–64 years) | 67.1 (64.3, 69.8) | 65.3 (61.8, 68.6) | 68.4 (65.4, 71.3) | 71.0 (67.3, 74.4) |

Note: All values are given in percentage (%) with 95% CIs in parentheses. F, female; M, male; NC, North Carolina.

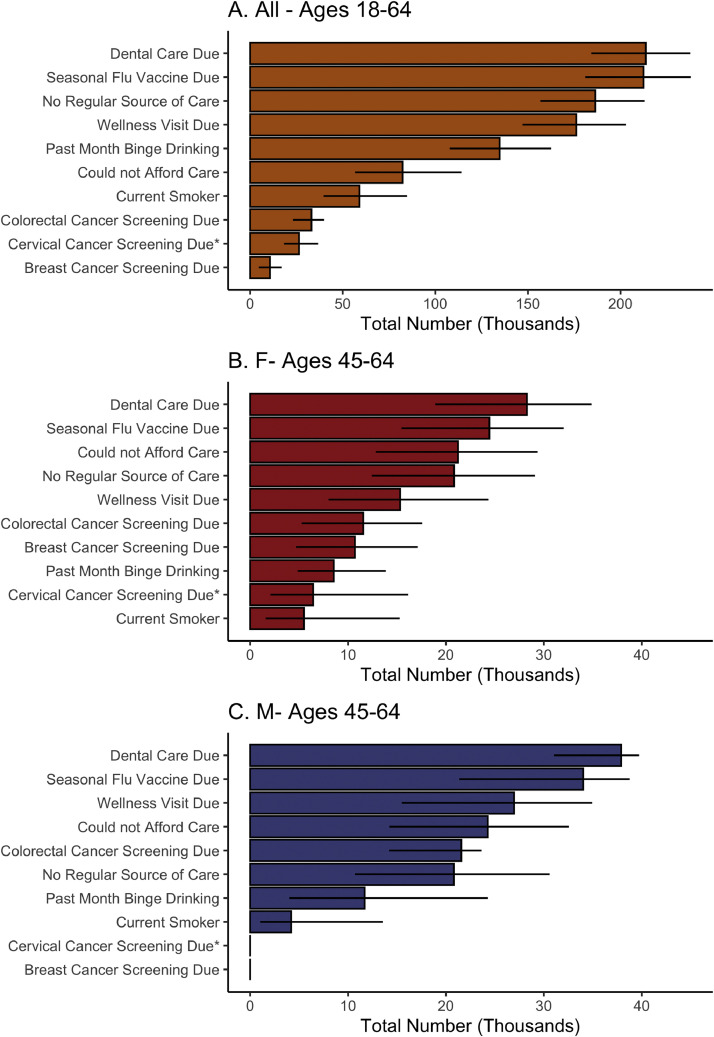

Using sample weights, the authors estimated the total number of individuals Medicaid expansion population due for all measured services on the basis of 2022 data (Figure 2). The authors estimated that 65,500 individuals in the Medicaid expansion population were overdue for 1 or more cancer screening. Estimates of need were even higher for several broadly recommended services, including 213,600 persons estimated to need dental care; 212,400 persons needing a seasonal flu vaccine; and 186,400 persons needing a regular source for primary care.

Figure 2.

Unmet needs of the Medicaid expansion population.

The asterisk (*) denotes cervical cancer screening data from 2020. F, female; M, male.

When subsetting to those aged 45–64 years, the highest unmet needs among women were dental care (28,300 women), flu vaccines (24,400 women), and affordability (21,200 women), with a high need for both colorectal (11,600 women) and breast (10,700 women) cancer screening. For men aged 45–64 years, the highest areas of need included dental care (37,900 men), flu vaccination (34,000 men), and wellness visits (27,000 men), with a notably high need for colorectal cancer screening (21,600 men). When further expanding colorectal cancer eligibility from age 50 years to age 45 years following recently updated USPSTF recommendations, an additional 5,700 women and 10,800 men in the Medicaid expansion population were estimated to be due for colorectal screening.

DISCUSSION

Using data from a large, representative survey, the authors find that those in the North Carolina Medicaid expansion population report more frequent cost-related barriers to care and low access to primary care and high prevalence of unmet needs for preventive care services, including annual wellness visits, cancer screenings, seasonal flu vaccines, and dental care. As these individuals become insured, it is important to ensure the availability of primary care services and use enrollment as an opportunity to catch up on overdue services. In other states, Medicaid expansion has resulted in improvements in preventive care services.4 How this additional need for capacity will be met is also an important question for the healthcare system—data from previous expansion states have shown that a large portion of this demand is met by federally qualified health centers and other safety-net providers.25,26 Bolstering the health workforce and improving primary care capacity across the state, including advanced practice providers, is important for ensuring that the newly insured population will be able to find providers.10,27,28

The authors find that the size of the expansion population has declined over time. A large portion of this decline was likely due to changes during the COVID-19 pandemic, allowing for continuous enrollment on Medicaid and other policies that led to decreases in poverty and uninsurance. These and other public health emergency provisions expired in 2023, removing an estimated 200,000 individuals from the Medicaid program.14,15 Furthermore, the authors include only those who were uninsured, but individuals may also move into the Medicaid program from other insurance sources—these individuals may have fewer unmet preventive care needs—but will be important in program planning.

The authors find that the most common unmet need among the Medicaid expansion population in North Carolina is dental care, a well-documented challenge in the state.29 Although Medicaid includes dental coverage for adults, this may be a particular challenge to address owing to a lack of dentists in the state who accept Medicaid.30 Compared with Healthy People 2030 goals and to traditional Medicaid, the authors find that the largest gaps are in reporting a regular source of care and a past-year wellness visit, both of which are likely necessary, although certainly not sufficient, for high-quality preventive care. Notably, the authors also find that binge drinking is reported by 20% of the expansion population in 2022 (identical to the prevalence of binge drinking in the overall nonelderly adult North Carolina population) and that smoking is reported by 28% of the expansion population, about twice the rate in the North Carolina population. Expansion may present an opportunity to identify these risk behaviors and provide resources for those wishing to reduce their drinking or smoking. Evidence from prior expansion states suggests that coverage itself is insufficient to improve these measures; therefore, targeted interventions specific to this population should be considered.31,32

Cancer screening services also merit additional attention because these services are only beneficial if connected effectively to care pathways in the case of a positive test. Those who are newly insured may be at increased risk for having disease identified on a screen.33 The health care system must therefore be ready for navigating individuals, including those who may have minimal prior contact with the healthcare system, through to appropriate care, a challenge that may be hardest for cervical and colorectal cancer.34 Tracking not only screening completion but also follow-up for those with positive tests would be a valuable way for North Carolina to ensure that care is delivered effectively throughout an entire screening episode. Use of lung cancer screening could not be adequately measured for those in the expansion population, but among those eligible in North Carolina, the authors find that only around a third of those recommended for a low-dose computed tomography had received one, suggesting that resources for both patients and providers on screening recommendations may be valuable to promoting adequate cancer screenings for those newly insured.

Limitations

The Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey offers unique cross-sectional data on the health, health behaviors, and healthcare access of populations in North Carolina and across the U.S. In the future, these data can be used to evaluate the impact of Medicaid expansion on care usage for low-income adults, as has been done in other expansion states.35 However, there are a few limitations to this approach. First, self-report of preventive care measures may be subject to over-reporting.36 Second, the authors can identify those potentially eligible for expanded Medicaid through income, but because nearly a quarter of participants declined to report their income, the authors are likely underestimating the number of individuals in the Medicaid expansion population. Not all of those the authors identified as in the potential expansion population will be eligible for Medicaid, including many noncitizens. Although some noncitizens are eligible for Medicaid, rules are complicated, and evidence suggests that this group does not benefit to the extent of native-born or naturalized U.S. citizens.37 Finally, the authors note that additional data on preventive care, including ability to get a timely appointment, continuity of care, and use of other preventive services such as depression and blood pressure screenings, would be valuable for long-term monitoring. Despite this, this analysis provides some valuable evidence of the distinct characteristics and needs of the Medicaid expansion population.

CONCLUSIONS

The Medicaid expansion population in North Carolina is a particularly underserved group, reflecting numerous barriers to quality care access. Although this population reports better health than the traditional Medicaid population by several measures (chronic conditions, functional disability), those in the expansion population are more likely to self-report poor health and report lower access to preventive health care across nearly every measure. As this population becomes newly eligible for care, the state government and healthcare providers across the state should be ready to address this unmet need for care and seize a crucial opportunity for closing health gaps for low-income individuals across the state.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding: MPP received support from the ACS Clinical Research Professor Award. JCS is supported by a Career Development Award from National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (K01MD017633-02).

Declaration of interest: None.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.focus.2024.100289.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

REFERENCES

- 1.Medicaid expansion to begin soon in North Carolina as governor decides to let budget bill become law, September 2023, AP News, Published online. Available from:https://apnews.com/article/north-carolina-medicaid-expansion-governor-legislature-330ea1adef37a323b31a9cfe0d470a58. Accessed January 10, 2024.

- 2.Garfield R, Damico A, Orgera K. Kaiser Family Foundation; San Francisco, CA: January 2020. The coverage gap: uninsured poor adults in states that do not expand Medicaid.https://files.kff.org/attachment/Issue-Brief-The-Coverage-Gap-Uninsured-Poor-Adults-in-States-that-Do-Not-Expand-Medicaid Accessed January 10, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aaronson MRM, Zhao MY, Lei Y, de Silva S, Badiee J, May FP. Medicaid expansion states see long-term improvement in colorectal cancer screening uptake among low-income individuals. Gastroenterology. 2024;166:518–520.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sommers BD, Blendon RJ, Orav EJ, Epstein AM. Changes in utilization and health among low-income adults after Medicaid expansion or expanded private insurance. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(10):1501–1509. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.4419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Song S, Kucik JE. Trends in the impact of Medicaid expansion on the use of clinical preventive services. Am J Prev Med. 2022;62(5):752–762. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2021.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedman AS, Thomas S, Suttiratana SC. Differences in cancer screening responses to state Medicaid expansions by race and ethnicity, 2011-2019. Am J Public Health. 2022;112(11):1630–1639. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2022.307027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ku L, Jones K, Shin P, Bruen B, Hayes K. The states’ next challenge — securing primary care for expanded Medicaid populations. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(6):493–495. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1011623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rhodes KV, Basseyn S, Friedman AB, Kenney GM, Wissoker D, Polsky D. Access to primary care appointments following 2014 insurance expansions. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(2):107–112. doi: 10.1370/afm.2043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Candon M, Polsky D, Saloner B, et al. Primary care appointment availability and the ACA insurance expansions. LDI Issue Brief. 2017;21(5):1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petterson SM, Cai A, Moore M, Bazemore A. State-Level Projections of Primary Care Workforce, 2010–2030, The Robert Graham Center. 2013. Available at: https://www.graham-center.org/publications-reports/by-topic/workforce.html. Accessed March 29, 2024.

- 11.Spencer JC, Gertner AK, Silberman PJ. Health status and access to care for the North Carolina Medicaid gap population. N C Med J. 2019;80(5):269–275. doi: 10.18043/ncm.80.5.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saloner B, Gollust SE, Planalp C, Blewett LA. Access and enrollment in safety net programs in the wake of COVID-19: a national cross-sectional survey. PLoS One. 2020;15(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baxley J. North Carolina Health News; June 1, 2023. “Unwinding” could undermine Medicaid expansion in North Carolina.https://www.northcarolinahealthnews.org/2023/06/01/unwinding-could-undermine-medicaid-expansion-in-north-carolina/ Accessed January 10, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaiser Family Foundation . Kaiser Family Foundation; San Francisco, CA: October 9, 2024. Medicaid enrollment and unwinding tracker.https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-enrollment-and-unwinding-tracker/ Accessed March 17, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sandoe E. Keeping people enrolled during Medicaid expansion and COVID-19 continuous coverage unwinding. N C Med J. 2024;85(2):89–91. doi: 10.18043/001c.94842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.North Carolina Center for State Health Statistics. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey. Published Online 2016/2022. https://schs/dph.ncdhhs.gov/units/stat/brfss. Accessed October 23, 2023.

- 17.Robert H. Four Methods for Calculating Income as a Percent of the Federal Poverty Guideline (FPG) in the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) [Internet]. Minneapolis, MN: State Health Access Data Assistance Center; 2019. Available from:https://www.shadac.org/sites/default/files/publications/Calculating_Income_as_PercentFPG_BRFSS.pdf. Accessed July 15, 2024.

- 18.Siu AL. Screening for breast cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(4):279–296. doi: 10.7326/M15-2886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Curry SJ, Krist AH, et al. Screening for cervical cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320(7):674–686. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.10897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Davidson KW, Barry MJ, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2021;325(19):1965–1977. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.6238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Krist AH, Davidson KW, et al. Screening for lung cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2021;325(10):962–970. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Published Online 2023. Available from: https://www.R-project.org/. Accessed June 16, 2023.

- 23.Lumley T. Analysis of complex survey samples. J Stat Soft. 2004;9(8):1–19. doi: 10.18637/jss.v009.i08. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Healthy people 2030. US Department of Health and Human Servies. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health. Available from: https://health.gov/healthypeople. Accessed January 02, 2024.

- 25.Rieselbach R, Epperly T, McConnell E, Noren J, Nycz G, Shin P. Community health centers: a key partner to achieve Medicaid expansion. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(10):2268–2272. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05194-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cole MB, Wright B, Wilson IB, Galárraga O, Trivedi AN. Medicaid Expansion And Community Health Centers: care quality and service use increased for rural patients. Health Aff (Millwood) 2018;37(6):900–907. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McConnell KJ, Charlesworth CJ, Zhu JM, et al. Access to primary, mental health, and specialty care: a comparison of Medicaid and commercially insured populations in Oregon. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(1):247–254. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05439-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Newman L, Taylor S, Levis Hewson DL, Wroth T. Is primary care adapting to Medicaid managed care in North Carolina? Implications for expansion and future managed care transitions. North Carolina Med J. 2024;85(2):121–124. doi: 10.18043/001c.94872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fraher E, McGee V, Hom J, Lyons J, Gaul K. We're not keeping up with the Joneses: North Carolina has fewer dentists per capita than neighboring (and most other) states. N C Med J. 2012;73(2):111–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nasseh K, Fosse C, Vujicic M. Dentists who participate in Medicaid: who they are, where they locate, how they practice. Med Care Res Rev. 2023;80(2):245–252. doi: 10.1177/10775587221108751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Phillips AZ, Karriker-Jaffe KJ, Bensley KMK, Subbaraman MS, Delk J, Mulia N. Residence in a Medicaid-expansion state and receipt of alcohol screening and brief counseling by adults with lower incomes: is increased access to primary care enough? Alcohol Clin Exp Res (Hoboken) 2023;47(7):1390–1405. doi: 10.1111/acer.15102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ku L, Bruen BK, Steinmetz E, Bysshe T. Medicaid tobacco cessation: big gaps remain in efforts to get smokers to quit. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35(1):62–70. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kirkpatrick D, Dunn M, Tuttle R. Breast cancer stage at presentation in Ohio: the effect of Medicaid expansion and the Affordable Care Act. Ann M Surg. 2020;86(3):195–199. doi: 10.1177/000313482008600327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tosteson ANA, Beaber EF, Tiro J, et al. Variation in screening abnormality rates and follow-up of breast, cervical and colorectal cancer screening within the PROSPR consortium. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(4):372–379. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3552-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Benitez JA, Adams EK, Seiber EE. Did health care reform help Kentucky address disparities in coverage and access to care among the poor? Health Serv Res. 2018;53(3):1387–1406. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rauscher GH, Johnson TP, Cho YI, Walk AHA. Accuracy of self-reported cancer-screening histories: a meta-anlysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:748–757. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stimpson JP, Wilson FA. Medicaid expansion improved health insurance coverage for immigrants, but disparities persist. Health Aff. 2018;37(10):1656–1662. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.