Abstract

Purpose

Variants in PIK3CA (encoding p110α; the catalytic subunit of PI3K) characterize some disorders of somatic mosaicism (DoSM) conditions with clinical features, including sporadic overgrowth and vascular malformations. Here, we profile PIK3CA variants in DoSM.

Methods

We applied a next-generation, sequencing-based, laboratory-developed test, using an average coverage of approximately 2000× for up to 37 genes associated with DoSM, on a cohort of 1197 patients with DoSM referred for clinical genomics services between 2013 and 2022.

Results

We identified clinically reportable variants in 747 (62.4%) individuals in this cohort. Notably, 371 clinically reportable variants in PIK3CA were identified in 368 patients, constituting approximately 49.2% of all patients with reportable findings. Variants in the C2 domain of p110α are enriched in DoSM (this cohort) compared with those of cancer (Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer [COSMIC] database), highlighting the role of the C2 domain in driving uncontrolled cell proliferation in DoSM. Furthermore, we report 17 novel variants in PIK3CA that are not previously reported in DoSM and describe clinical presentation correlation for 4 novel variants.

Conclusion

Our findings from the largest single-center cohort of patients with DoSM expand the spectrum of variants in PIK3CA and shed light on the less-studied role of the C2 domain in the pathogenesis of DoSM.

Keywords: NGS, PIK3CA, PIK3CA-related overgrowth spectrum, PROS, Somatic mosaicism

Introduction

PIK3CA is one of the most frequently mutated genes across all human cancers.1 PIK3CA encodes p110α, the catalytic subunit of the Class I phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) enzyme, which catalyzes the conversion of membrane lipid phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate1 to the second messenger PI(3,4,5)P3 or PIP3.2 p110α heterodimerizes with p85α regulatory subunit, encoded by PIK3R1.3 Activation of p110α results in an increase of PIP3, which stimulates the recruitment of effector proteins, including protein kinase B serine/threonine kinases (AKT), and activates the AKT/mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathways, inducing cell growth, metabolism, survival, and proliferation.4,5

The p110α subunit of PI3K comprises 5 domains: an N-terminal adaptor-binding domain (ABD) that binds to the p85α regulatory subunit, a RAS-binding domain, a C2 domain, a helical domain, and a kinase catalytic domain. The C2 domain mediates the interaction between p110α and p85α subunits.6 Variants disrupting the tightly constrained activity of the PI3K enzyme promote uncontrolled cell survival, proliferation, and migration, as seen in cancer and other disorders of uncontrolled cell proliferation. Such variants have been identified across the entire length of the p110α protein, with variants at 3 codons (Glu542 and Glu545 in the helical domain and His1047 in the kinase domain) as hotspots, constituting the majority of the oncogenic variants in different cancer types reported to date.1,7

Disorders of somatic mosaicism (DoSM) typically present at birth and are caused by spontaneous variants occurring postzygotically.8 Although germline variants are present in every cell of the body, somatic variants happen after conception and are not inherited. Variants that occur early during development may affect multiple organs and spread throughout the body. In contrast, variants occurring at later stages during development or after birth are typically confined to smaller regions. Given the pivotal role of the PI3K pathway in cell proliferation and survival, it is not surprising that variants in genes encoding its regulatory and kinase subunits (PIK3R1 and PIK3CA) are also implicated in DoSM. Rare, postzygotic activating variants in PIK3CA cause generally benign overgrowth syndromes, collectively termed PIK3CA-related overgrowth spectrum (PROS).9 PROS is an umbrella term for clinical presentations associated with somatic variants in PIK3CA, previously defined as separate entities, for example, congenital lipomatous overgrowth, vascular malformations, epidermal nevi, scoliosis syndrome (CLOVES); Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome (KTS); megalencephaly-capillary malformation syndrome (MCAP); megalencephaly-cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita.7 These somatic variants are found in the affected tissues; therefore, choosing the appropriate specimen is fundamental in the genetic diagnosis of DoSM.

Detection of causal variants in DoSM can be challenging because of the somatic nature of the variants and their relatively low abundance in the affected area.10 The advent of next-generation sequencing technology (NGS) and the ability to deeply sequence each DNA nucleotide at >1000× coverage allows for the reliable identification of these low-level mosaic variants and has made high-depth sequencing a core step in genetic diagnosis of DoSM.11,12

Similar to cancer, codons Glu542, Glu545, and His1047 are also hotspots in PROS, constituting >80% of cases reported to date.7,12,13 Functional studies have demonstrated the activating effect of these gain-of-function variants in vitro and in vivo.14, 15, 16, 17, 18 The application of NGS facilitates the detection of variants at these hotspots, while interrogating the entire length of PIK3CA gene (full exonic coverage with flanking intronic regions), permitting the discovery of novel variants in a single assay. Currently, >80 unique variants in PIK3CA have been identified in patients with PROS.12

Given the implication of altered PI3K activity in cancer, efforts have been made to develop effective treatments targeting this enzyme or other components of the AKT/mTOR pathway.19,20 Recent studies have demonstrated the efficacy of these therapies in inhibiting PI3K activity in patients with noncancerous overgrowth syndromes, that is, PROS, caused by pathogenic variants in PIK3CA. Alpelisib (PIQRAY) is one such drug that the Food and Drug Administration recently approved for administration in adult and pediatric patients with severe PROS who require systemic therapy.21,22 Thus, the identification of pathogenic somatic variants in these patients may lead to more effective treatment of their overgrowth.

In this study, we performed a review of the variants identified in the PIK3CA gene in patients with DoSM who were referred to our laboratory between 2013 and 2022. We sought to compare the frequencies of clinically reportable variants across the PIK3CA gene in our cohort and in patients diagnosed with cancer using the COSMIC database. We report novel variants in PIK3CA and describe the clinical presentation of patients with PROS with such variants.

Materials and Methods

Cohort and DNA sequencing

A total of 1197 individuals with DoSM were referred to our clinical genetics laboratory for NGS analysis between February 2013 and May 2022. DNA extraction and sequence analysis were performed on affected tissue samples, including fresh biopsy tissues, formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue, fibroblast cultures, or buccal specimens. Target enrichment was performed using oligonucleotide-based targeted capture of exonic regions for up to 37 genes known to cause DoSM, including PIK3CA. Enriched libraries were sequenced using Illumina instrumentation (HiSeq 2500 and NovaSeq 6000) according to the manufacturer’s recommended protocol to generate paired-end reads with an average unique on-target coverage depth of approximately 2000× to reliably detect variants of low-level mosaicism. Single-nucleotide variants with variant allele fraction (VAF) greater than 3% and small insertions and deletions (indels, <21 bp) were identified for further analysis. Variants with VAF between 1% and 3% were manually inspected for quality verification. The detailed descriptions of DNA isolation, library preparation, sequencing, bioinformatic analyses, and variant interpretation have been previously described.11 When a peripheral blood specimen was available, follow-up Sanger sequencing was performed to help determine the mosaic vs germline status of variants. Informed consent to publish patients’ photographs was obtained from the legal guardians of patients.

Variant interpretation

Annotated variants were subjected to expert classification using the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics/Association for Molecular Pathology standards and guidelines for constitutional variant interpretation,23 taking into consideration professional guidelines provided by ClinGen brain malformation variant curation expert panel,24 literature review and functional data, and representation within available databases of human genomic variation (eg, ClinVar or gnomAD). Clinically reportable variants were defined as those classified as pathogenic or likely pathogenic and of uncertain significance.

Results

Cohort overview

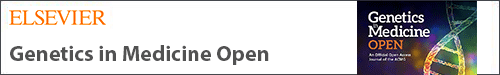

We received samples from 1197 patients with clinical indications of DoSM from clinics across the United States and Canada. In total, we identified at least 1 pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant in 747 patients (diagnostic yield = 62.4%) (Figure 1A), with 39 patients in this cohort having 2 clinically reportable variants detected. The co-occurrence of these variants in patients with DoSM is discussed in a separate study.25 A significant proportion of the patients with reportable findings had a variant identified in PIK3CA (n = 368, 30.7%), followed by GNAQ (n = 55), TEK (n = 50), KRAS (n = 38), GNA11 (n = 34), and HRAS (n = 22) (Figure 1B). Of the 368 patients with clinically reportable variants in PIK3CA (Supplemental Table 1), 3 individuals had 2 reportable variants, with 2 individuals having 1 variant with a VAF near a heterozygous state in this gene. A significant proportion of the variants identified by our assay were localized to the well-established hotspots of this gene at codons 1047 (n = 80, 21.6%), 542 (n = 40, 10.8%) and 545 (n = 38, 10.2%), collectively comprising approximately 42.6% of the variants identified in PIK3CA in our cohort. The majority of the variants in this gene were missense (n = 348, 93.8%); in-frame indels comprised 5.7% of the variants, with only 2 indel variants predicted to result in frameshift identified (∼0.5%) (Figure 1C). Among the 371 reported PIK3CA variants, 336 were classified as pathogenic, 31 were likely pathogenic, and only 4 were variants of unknown significance (Figure 1D). Among the 368 patients referred to our laboratory, the top indication for testing was MCAP (n = 54), followed by CLOVES (n = 21), and KTS (n = 15), with the rest of the patients with phenotypes related to DoSM, of no particular category. Analysis of these major categories by different domains/regions of p110α revealed no major differences in the frequency of these phenotypes, except for the decreased proportion of variants in the helical domain in patients with MCAP, relative to KTS, CLOVES, and other phenotypes (Supplemental Figure 1, Supplemental Table 1).

Figure 1.

Overview of the cohort. A. Genetic results in 1197 patients with DoSM referred to our laboratory. B. Distribution of clinically reportable variants by gene. C. Various classes of clinically reportable variants identified in PIK3CA. D. Breakdown of variants in PIK3CA by classification. DoSM, disorders of somatic mosaicism; Indel, insertions and deletions; P/LP, pathogenic or likely pathogenic; VUS, variant of uncertain significance.

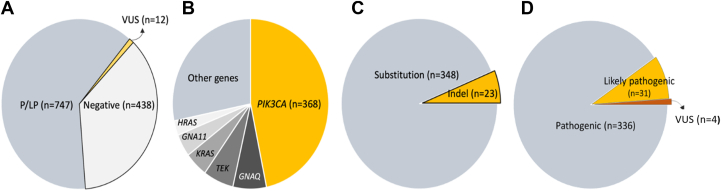

Distribution of PIK3CA variants in PROS patients vs COSMIC database

We sought to compare our findings with those reported in the COSMIC database (v96) for PIK3CA (https://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic). Synonymous variants reported in the COSMIC database were removed for this analysis, given that these variants are not likely to affect the function of p110α. In total, we included 10,202 variants in the PIK3CA gene from the COSMIC database (Figure 2A). Variants in the hotspot codons constitute the majority of the variants in both cancer and PROS (70% and 42.6%, respectively). We identified 77 variants in the C2 domain (approximately 21% of the variants in the cohort), suggesting an enrichment of variants in the C2 domain in patients with PROS compared with cancer (Figure 2). Variants in codons Cys378 (n = 11, 2.9%), Cys420 (n = 10, 2.7%), and Glu453 (n = 23, 6.2%) each contribute to >2% of total variants in our cohort (Supplemental Table 1). Notably, we identified 10 patients (2.7%) with a pathogenic in-frame deletion of codon Glu110 in our cohort, whereas this variant is present in only 2 cases (0.02%) of the COSMIC database (Figure 2A). Similarly, variants in codons Glu726 (n = 17, 4.6%) in the linker region between the helical and kinase domains (Figure 2B) and Gly914 (n = 19, 5.1%) were more enriched in our cohort compared with COSMIC, with Glu726 and Gly914 representing 0.7% and 0.004% of the variants identified in patients with cancer, respectively (Figure 2A). We did not identify any variants in the RAS-binding domain in patients with DoSM in our cohort, and variants in this domain were present in approximately 0.3% of the variants in the COSMIC database.

Figure 2.

Distribution of PIK3CA variants in cancer vs DoSM. A. Variants identified across the PIK3CA gene in the COSMIC database (top, blue) and DoSM (bottom, red). Variants with frequency >2% are labeled. B. Distribution of variants with frequency >1% identified in the COSMIC database (blue) and DoSM (red) by p110α domains and regions. COSMIC, Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer; DoSM, disorders of somatic mosaicism.

We identified 17 novel variants in PIK3CA that were not previously reported in DoSM (Supplemental Material). Notably, 6 novel variants, including c.6_50del p.(Pro5_Pro19del), c.91A>C p.(Ile31Leu), c.1053_1054insTACATTCGA p.(Ile351_Asp352insTyrIleArg), c.1253_1261del p.(Glu418_Pro421delinsAla), c.1253_1262delinsT p.(Glu418_P421delinsVal), and c.1324G>C p.(Ala442Pro), are not reported in the COSMIC database. Of the 17 novel variants, 8 (47%) are located in the C2 domain (Table 1). Fourteen variants were identified at a VAF consistent with somatic origin, and 3 were detected at a near-heterozygous VAF, 2 of which, c.91A>C p.(Ile31Leu) and c.2080G>T p.(Ala694Ser), were also present in the peripheral blood samples of the patients using follow-up Sanger sequencing, suggestive of a germline origin; however, multitissue, high-level mosaicism cannot be ruled out using this method. Peripheral blood specimen was not available for further testing of the third variant c.1324G>C p.(Ala442Pro) with a VAF of 47%.

Table 1.

Novel variants in PIK3CA identified in this cohort

| Patient ID | Clinical Indication | Variant | Domain | VAF | Variant Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 271 | CM with overgrowth | c.6_50del, p.(Pro5_Pro19del) | N terminus | 0.09 | VUS |

| 367 | Macrocephaly, cutis marmorata | c.91A>C, p.(Ile31Leu)a | ABD | 0.47 | VUS |

| 308 | Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome | c.314_316delTAG, p.(Val105del) | ABD | 0.02 | LP |

| 306 | Hemihypertrophy and extensive port wine stain | c.331A>G, p.(Lys111Glu) | ABD-RBD linker | 0.07 | P |

| 263 | VM and LM | c.1031T>G, p.(Val344Gly) | C2 | 0.06 | LP |

| 183 | Macrocephaly, CM, asymmetric overgrowth | c.1053_1054insTACATTCGA, p.(Ile351_Asp352insTyrIleArg) |

C2 | 0.04 | LP |

| 87 | Macroglossia and AVM | c.1097C>G, p.(Pro366Arg) | C2 | 0.27 | LP |

| 326 | Epidermal nevus | c.1253_1261del, p.(Glu418_Pro421delinsAla) | C2 | 0.16 | LP |

| 200 | Vascular anomaly | c.1253_1262delinsT, p.(Glu418_Pro421delinsVal) | C2 | 0.02 | LP |

| 302 | Macrodactyly of toes, CMTC, pyogenic granulomas | c.1324G>C, p.(Ala442Pro)b | C2 | 0.47 | VUS |

| 358 | CM and leg length discrepancy | c.1346C>T, p.(Pro449Leu) | C2 | 0.05 | LP |

| 277 | CM and hemihypertrophy | c.1358A>G, p.(Glu453Gly) | C2 | 0.08 | LP |

| 234 | Somatic asymmetry and CM | c.1636C>G, p.(Gln546Glu) | Helical | 0.03 | P |

| 182 | LM, microcephaly, cardiac defects | c.2080G>T, p.(Ala694Ser)a | Helical | 0.49 | VUS |

| 287 | CM | c.3012G>T, p.(Met1004Ile) | Kinase | 0.14 | LP |

| 92 | LM | c.3193delinsTT, p.(His1065LeufsTer8) | C terminus | 0.01 | LP |

| 20 | Congenital lipoma | c.3194_3202delinsT, p.(His1065LeufsTer5) | C terminus | 0.02 | LP |

Transcript NM_006218.4 was used to describe all variants. Variants are in order of the position of the variant in the reference sequence (Supplemental Table 1 and Supplemental Information).

ABD, adaptor-binding domain; AVM, arteriovenous malformation; CM, capillary malformation; CMTC, cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita; LM, lymphatic malformation; LP, likely pathogenic; P, pathogenic; RBD, RAS-binding domain; VAF, variant allele fraction; VM, venous malformation; VUS, variant of uncertain significance.

Identified at a near-heterozygous VAF and present in the peripheral blood.

Identified at a near-heterozygous VAF in a patient with a pathogenic somatic PIK3CA c.1324G>C p.(Glu545Asp) variant.

Clinical correlation of the PIK3CA novel variants

To clinically characterize the novel variants identified in this cohort, we performed a detailed review of the clinical presentation of 4 patients for whom clinical information was available. Clinical information of 3 additional patients with novel variants are provided in the Supplemental Material.

Patient 271 was a 7-year-old girl with congenital vascular patches on the right face, scalp (Figure 3B) and lower lip, and reticulated vascular lesions extensively distributed bilaterally over much of the trunk and extremities (Figure 3A-E). In infancy, the right arm was subtly larger in girth than the left. Over time, deeper vascular malformations in the chest and back became apparent, as well as more generalized asymmetric overgrowth, including large feet with widened first interdigital space and long second toes bilaterally (Figure 3C), with the right leg being longer than the left requiring use of a heel lift. Genetic testing performed on fresh tissue biopsied from the vascular lesion on the upper right chest identified a novel somatic variant NM_006218.4:c.6_50del p.(Pro5_Arg19del) at 9% VAF, resulting in an in-frame deletion of 15 amino acids in the N terminus of p110α. This variant has not been reported in the general population databases (gnomAD v2.1.1). Sanger sequencing performed on a peripheral blood specimen from the patient did not identify this variant in PIK3CA, indicating somatic origin. The presence of this variant in a patient with vascular malformation and overgrowth supports a PROS diagnosis. In light of the patient’s overall excellent functionality and lack of organ system compromise, systemic therapy with alpelisib has not been pursued to date.

Figure 3.

Patients’ clinical presentation. Representative photographs of patients 271 (A-E), 306 (F, G), 92 (H, I), and 358 (J, K). A. Left trunk at 3 months of age. B. Head and trunk 3 months of age. C. Feet at 5 years of age. D. Back at 3 years of age. E. Upper body at 5 years of age. F. Left leg hemihypertrophy and extensive port wine stain. G. Bilateral larger second toes. H. Ptosis of the right eye. I. Lymphatic malformation of the hard palate. J and K. Capillary malformation of the right forearm.

Patient 306 was born term to nonconsanguineous parents, with congenital widespread capillary malformation, noted to be darker and more homogeneous on both feet, lighter and more reticulated on both legs, abdomen, back, and groin (Figure 3F). Bilateral second toes were longer and slightly larger than the great toes, with a subtle overgrowth of the left leg suggestive of hemihypertrophy. Genetic testing was performed at 6.5 years of age on a fresh tissue specimen from the patient’s left leg and identified a novel clinically significant NM_006218.4:c.331A>G p.(Lys111Glu) variant in the PIK3CA gene at 7% VAF. This variant is reported in multiple patients with breast carcinoma and other cancer types in the COSMIC database (COSM13570) but not in patients with DoSM. Subsequently, Sanger sequencing performed on the peripheral blood specimen of this patient did not identify this variant, confirming the somatic origin of this variant in PIK3CA.

Patient 92 was a 6-year-old girl with congenital ptosis of the right eye (Figure 3H). Magnetic resonance imaging performed at the age of 2 months showed a prenasal mass with no intracranial or retro-orbital extension, which might result in right eye vision impairment per ophthalmological examination. Given these findings, she was initially treated for presumptive infantile hemangioma with propranolol without improvement. At the age of 2 years, lesions on the hard palate were noticed, consistent with a lymphatic malformation on pathology examination (Figure 3I). Genetic testing performed on a formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded sample from this specimen identified a frameshift NM_006218.4:c.3193delinsTT p.(His1065LeufsTer8) variant in PIK3CA at 1% VAF. Given these findings, the patient was diagnosed with PROS.

Patient 358 was an 8-year-old boy with a diffuse capillary malformation on the right arm and leg (Figure 3J and K) with ipsilateral undergrowth of both affected extremities. Orthopedics is managing his leg length discrepancy with an orthotic incorporating a lift. Genetic testing was performed on a punch biopsy specimen from the right forearm and identified a novel NM_006218.4:c.1346C>T p.(Pro449Leu) variant in PIK3CA at 5% VAF. This variant has been reported in only 2 patients with skin and endometrium carcinoma in the COSMIC database (COSM1041482). Sanger sequencing for comparative analysis performed on a peripheral blood sample did not detect PIK3CA c.1346C>T p.(Pro449Leu), consistent with a somatic origin for this variant. Given these findings, the clinical team decided on continued vigilance for secondary cancer and clotting risks associated with PROS.26

Discussion

Gain-of-function pathogenic variants in PIK3CA result in the constitutive activation of the AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. This effect has been well established using in vitro and in vivo studies,14, 15, 16, 17, 18 particularly for the variants occurring in the hotspot codons, which account for most variation detected in PIK3CA to date. Although the functional and clinical impact and the frequency of the hotspot variants in PIK3CA are well understood in the context of cancer and DoSM, less is known about the noncanonical or rare variants in this gene causing DoSM. Efforts have been made to characterize some of these variants, particularly in the setting of cancer.27, 28, 29 Still, lack of this information for the majority of these low-abundance variants is one of the significant challenges in interpreting their clinical relevance in patients with DoSM.

High-depth NGS provides a powerful tool for identifying mosaic variants in DoSM, which are typically of at a low fraction in the affected tissues. Furthermore, this method allows for the sequencing of the entire length of the PIK3CA gene, encompassing exons and exon-flanking regions, promoter and untranslated regions, permitting the identification of novel variants in this gene that are not otherwise detectable by targeted sequencing of only hotspot codons. Using a high-depth NGS assay on the largest single-center study of 1197 patients with DoSM, we identified 747 individuals (62.4%) with clinically reportable variants. A total of 371 clinically reportable variants in PIK3CA were identified in 368 (30.7%) patients, making PIK3CA variants the most common cause of DoSM in our cohort.

High coverage of approximately 2000× enabled us to detect low-abundance somatic variants (as low as VAF ≈ 1%) in PIK3CA that helped confirm a diagnosis of PROS in some of the patients in this cohort. We report 17 novel variants in PIK3CA not previously reported in DoSM, 7 of which have not been reported in patients with cancer in the COSMIC database. In one of the patients with a presumed diagnosis of hemangioma, follow-up histopathological studies confirmed the presence of a lymphatic malformation, prompting genetic testing. Our NGS assay identified a low VAF novel NM_006218.4:c.3193delinsTT p.(His1065LeufsTer8) variant, which established a diagnosis of PROS and guided the course of the treatment for this patient.

Clinically reportable variants in the C2 domain were disproportionally enriched in our cohort of patients with DoSM compared with patients with cancer in the COSMIC database. The C2 domain was initially proposed to play a role in facilitating the binding of PI3K to the cellular membranes30; however, later studies revealed its role in mediating the binding of p110α to the p85α regulatory subunit.6 Therefore, it is plausible that damaging variants in the C2 domain of p110α would disrupt its interaction with p85α, resulting in the pathological hyperactivation of the PI3K enzyme. Our findings demonstrate the higher frequency of the C2-domain variants in patients with PROS than previously thought31 and underscore the importance of this relatively underexamined domain in the function of p110α. These results will help the future interpretation of variants in this domain identified in patients with DoSM, guiding their diagnosis and management. The differential enrichment of variants in the C2-domain could be due to differences in the underlying activation mechanisms in PROS vs cancer, which warrants future studies on this domain focusing on genotype-phenotype correlations and the development of targeted therapies.

We identified 2 patients with variants in PIK3CA present at a near-heterozygous state, which were also detected in the peripheral blood specimens of the patients: a NM_006218.4:c.91A>C, p.(Ile31Leu) variant in a 1-year-old girl (patient 367) with macrocephaly and cutis marmorata, and an NM_006218.4:c.2080G>T p.(Ala694Ser) variant in a 2-year-old girl (patient 182), who presented with lymphatic malformation of the right anterolateral chest and right arm, microcephaly, and left ventricular and atrial dilation. Germline PIK3CA variants are described in patients with Cowden syndrome, which is characterized by uncontrolled cell growth with broad phenotypic presentations including macrocephaly and developmental delay with an increased risk for various cancer types, particularly breast, thyroid, endometrial, and colorectal cancer.32 Although rare, germline variants in PIK3CA have also been reported in patients presenting with clinical features of DoSM, including macrocephaly, overgrowth, and developmental delay.33 Given the relatively mild phenotype, more consistent with the diagnosis of PROS, of these patients, it is unlikely that the identified variants would cause classical Cowden syndrome. Nevertheless, the identification of germline variants in patients with DoSM may warrant surveillance to monitor benign and malignant neoplasms.

Our assay enables us to robustly detect indels in addition to single-nucleotide variants. In fact, indels resulting in in-frame deletions/insertions or frameshift variants were identified in 23 of 368 patients with PROS (6.2%), constituting 8 of 17 novel variants identified in PIK3CA (Table 1). These findings highlight the importance of careful examination of indels when developing bioinformatics pipelines for genetic testing of patients with DoSM and may partially explain the lack of a molecular diagnosis in patients with PROS when only interrogating single-nucleotide missense variants.

Our results should be interpreted in the context of a few important limitations. Although our panel allows for the accurate and sensitive detection of single-nucleotide variants and indels, somatic variants of very low abundance (<0.5%) and larger (>50 bp) structural variants cannot be detected using this method. The latter may play a role in the pathogenesis of DoSM in a subset of patients, and future studies using other assays, including genome sequencing, may identify a molecular diagnosis for patients with no clinically reportable variants in gene panels. Another limitation of current studies on identification and interpretation of variants in DoSM comes from the lack of knowledge about the noncoding variants in genes implicated in DoSM, which makes interpreting these types of variants challenging.

In the era of precision medicine and with the development of molecular-guided therapies for specific genes and variants, sequencing and bioinformatics tools applied in genetic diagnosis play a central role in identifying the underlying genetic cause that in some diseases, including PROS, are instrumental in the diagnosis and subsequent therapies. Disease severity and clinical presentation are determined by tissue distribution, abundance, and the type of the activating variant in PIK3CA, significantly complicating genotype-phenotype correlation studies in PROS. Nevertheless, with the increasing accessibility to NGS, we are identifying novel variants in this gene to better understand the spectrum of the variants, and through genotype-phenotype as well as pharmacogenetics studies, we are more accurately predicting the progression of the phenotypes and treatment responsiveness for newly diagnosed patients.

Data Availability

All relevant data are reported in the article and the supplemental materials. The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available because of privacy or ethical restrictions.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients and their families for contributing to this study. They also thank all faculty and staff at the genetic and genomic services at the Washington University in St. Louis.

Funding

There is no funding for this study.

Author Information

Conceptualization: Y.C.; Data Curation: B.A.M., P.V.H., M.J.E., M.M.C., B.S., M.M., A.T., C.C.C., S.L.S.; Formal Analysis: B.A.M., P.V.H., Y.C.; Methodology: Y.C., M.J.E., M.M.C., J.W.H., M.C.S., J.A.N.; Visualization: B.A.M., P.V.H., S.L.S., A.T., B.S., M.M., C.C.C.; Writing-original draft: B.A.M.; Writing-review and editing: all authors; Supervision: Y.C.

Ethics Declaration

The study protocol (IRB #: 202103225) was approved by the institutional review board of Washington University School of Medicine. These data were collected during clinical testing. The individual-level data were deidentified. Informed written consent and permission were obtained to publish patients’ photographs and images.

Footnotes

This article was invited and the Article Publishing Charge (APC) was waived.

Additional Information

The online version of this article (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gimo.2023.100815) contains supplemental material, which is available to authorized users.

Additional Information

References

- 1.Martínez-Sáez O., Chic N., Pascual T., et al. Frequency and spectrum of PIK3CA somatic mutations in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2020;22(1):45. doi: 10.1186/s13058-020-01284-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Czech M.P. PIP2 and PIP3: complex roles at the cell surface. Cell. 2000;100(6):603–606. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80696-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Engelman J.A., Luo J., Cantley L.C. The evolution of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases as regulators of growth and metabolism. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7(8):606–619. doi: 10.1038/nrg1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cantley L.C. The phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway. Science. 2002;296(5573):1655–1657. doi: 10.1126/science.296.5573.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Samuels Y., Diaz L.A., Schmidt-Kittler O., et al. Mutant PIK3CA promotes cell growth and invasion of human cancer cells. Cancer Cell. 2005;7(6):561–573. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang C.H., Mandelker D., Schmidt-Kittler O., et al. The structure of a human p110alpha/p85alpha complex elucidates the effects of oncogenic PI3Kalpha mutations. Science. 2007;318(5857):1744–1748. doi: 10.1126/science.1150799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Madsen R.R., Vanhaesebroeck B., Semple R.K. Cancer-associated PIK3CA mutations in overgrowth disorders. Trends Mol Med. 2018;24(10):856–870. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2018.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell I.M., Shaw C.A., Stankiewicz P., Lupski J.R. Somatic mosaicism: implications for disease and transmission genetics. Trends Genet. 2015;31(7):382–392. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2015.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keppler-Noreuil K.M., Rios J.J., Parker V.E., et al. PIK3CA-related overgrowth spectrum (PROS): diagnostic and testing eligibility criteria, differential diagnosis, and evaluation. Am J Med Genet A. 2015;167A(2):287–295. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hucthagowder V., Shenoy A., Corliss M., et al. Utility of clinical high-depth next generation sequencing for somatic variant detection in the PIK3CA-related overgrowth spectrum. Clin Genet. 2017;91(1):79–85. doi: 10.1111/cge.12819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McNulty S.N., Evenson M.J., Corliss M.M., et al. Diagnostic utility of next-generation sequencing for disorders of somatic mosaicism: a five-year cumulative cohort. Am J Hum Genet. 2019;105(4):734–746. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2019.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mussa A., Leoni C., Iacoviello M., et al. Genotypes and phenotypes heterogeneity in PIK3CA-related overgrowth spectrum and overlapping conditions: 150 novel patients and systematic review of 1007 patients with PIK3CA pathogenetic variants. J Med Genet. 2023;60(2):163–173. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2021-108093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mirzaa G., Timms A.E., Conti V., et al. PIK3CA-associated developmental disorders exhibit distinct classes of mutations with variable expression and tissue distribution. JCI Insight. 2016;1(9) doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.87623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Castillo S.D., Tzouanacou E., Zaw-Thin M., et al. Somatic activating mutations in Pik3ca cause sporadic venous malformations in mice and humans. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8(332):332ra43. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad9982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peyre M., Miyagishima D., Bielle F., et al. Somatic PIK3CA mutations in sporadic cerebral cavernous malformations. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(11):996–1004. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2100440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindhurst M.J., Parker V.E., Payne F., et al. Mosaic overgrowth with fibroadipose hyperplasia is caused by somatic activating mutations in PIK3CA. Nat Genet. 2012;44(8):928–933. doi: 10.1038/ng.2332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun B., Jiang Y., Cui H., et al. Activating PIK3CA mutation promotes adipogenesis of adipose-derived stem cells in macrodactyly via up-regulation of E2F1. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11(7):600. doi: 10.1038/s41419-020-02806-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roy A., Skibo J., Kalume F., et al. Mouse models of human PIK3CA-related brain overgrowth have acutely treatable epilepsy. eLife. 2015;4 doi: 10.7554/eLife.12703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Venot Q., Blanc T., Rabia S.H., et al. Targeted therapy in patients with PIK3CA-related overgrowth syndrome. Nature. 2018;558(7711):540–546. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0217-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parker V.E.R., Keppler-Noreuil K.M., Faivre L., et al. Safety and efficacy of low-dose sirolimus in the PIK3CA-related overgrowth spectrum. Genet Med. 2019;21(5):1189–1198. doi: 10.1038/s41436-018-0297-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morin G., Degrugillier-Chopinet C., Vincent M., et al. Treatment of two infants with PIK3CA-related overgrowth spectrum by alpelisib. J Exp Med. 2022;219(3) doi: 10.1084/jem.20212148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pagliazzi A., Oranges T., Traficante G., et al. PIK3CA-related overgrowth spectrum from diagnosis to targeted therapy: a case of CLOVES syndrome treated with alpelisib. Front Pediatr. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.732836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richards S., Aziz N., Bale S., et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17(5):405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lai A., Soucy A., El Achkar C.M., et al. The ClinGen Brain Malformation Variant Curation Expert Panel: rules for somatic variants in AKT3, MTOR, PIK3CA, and PIK3R2. Genet Med. 2022;24(11):2240–2248. doi: 10.1016/j.gim.2022.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cao Y., Evenson M.J., Corliss M.M., Schroeder M.C., Heusel J.W., Neidich J.A. Co-existence of 2 clinically significant variants causing disorders of somatic mosaicism. GIM Open. 2023;1(1):100807. doi: 10.1016/j.gimo.2023.100807. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keppler-Noreuil K.M., Lozier J., Oden N., et al. Thrombosis risk factors in PIK3CA-related overgrowth spectrum and Proteus syndrome. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2019;181(4):571–581. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loconte D.C., Grossi V., Bozzao C., et al. Molecular and functional characterization of three different postzygotic mutations in PIK3CA-related overgrowth spectrum (PROS) patients: effects on PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling and sensitivity to PIK3 inhibitors. PLoS One. 2015;10(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dogruluk T., Tsang Y.H., Espitia M., et al. Identification of variant-specific functions of PIK3CA by rapid phenotyping of rare mutations. Cancer Res. 2015;75(24):5341–5354. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jin N., Keam B., Cho J., et al. Therapeutic implications of activating noncanonical PIK3CA mutations in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Invest. 2021;131(22) doi: 10.1172/JCI150335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gabelli S.B., Huang C.H., Mandelker D., Schmidt-Kittler O., Vogelstein B., Amzel L.M. Structural effects of oncogenic PI3Kα mutations. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2010;347:43–53. doi: 10.1007/82_2010_53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lalonde E., Ebrahimzadeh J., Rafferty K., et al. Molecular diagnosis of somatic overgrowth conditions: a single-center experience. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2019;7(3):e536. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Orloff M.S., He X., Peterson C., et al. Germline PIK3CA and AKT1 mutations in Cowden and Cowden-like syndromes. Am J Hum Genet. 2013;92(1):76–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zollino M., Ranieri C., Grossi V., et al. Germline pathogenic variant in PIK3CA leading to symmetrical overgrowth with marked macrocephaly and mild global developmental delay. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2019;7(8):e845. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are reported in the article and the supplemental materials. The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available because of privacy or ethical restrictions.