Abstract

Background:

Nurse-patient relationships are an integral component of person-centred palliative care. Greater understanding of how nurse-patient relationships are fostered and perceived by patients and nurses can be used to inform nursing practice.

Aim:

To systematically identify and synthesise how nurse-patient relationships are fostered in specialist inpatient palliative care settings, and how nurse-patient relationships were perceived by patients and nurses.

Design:

Integrative review with narrative synthesis. The review protocol was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42022336148, updated April, 2023).

Data Sources:

Five electronic databases (PubMed, CINAHL Complete, Medline, Web of Science and PsycINFO) were searched for articles published from their inception to December 2023. Studies were included if they (i) examined nurse and/or patient perspectives and experiences of nurse-patient relationships in specialist inpatient palliative care, (ii) were published in English in a (iii) peer-reviewed journal. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool was used to evaluate study quality. Data were synthesised using narrative synthesis.

Results:

Thirty-four papers from 31 studies were included in this review. Studies were mostly qualitative and were of high methodological quality. Four themes were identified: (a) creating connections; (b) fostering meaningful patient engagement; (c) negotiating choices and (d) building trust.

Conclusions:

Nurses and patients are invested in the nurse-patient relationship, benefitting when it is positive, therapeutic and both parties are valued partners in the care. Key elements of fostering the nurse-patient relationship in palliative care were revealed, however, the dominance of the nurses’ perspectives signifies that the nature and impact of these relationships may not be well understood.

Keywords: Hospice, integrative review, nursing, nurse-patient relations, palliative care, patients

What is already known about this topic?

The nurse-patient relationship is considered the foundation of palliative care nursing.

Nurse-patient relationships are founded on trust, empathy, authenticity, genuineness and intentionality.

Person-centred care requires palliative care nurses to form interpersonal relationships that elicit patients’ true wishes and recognise and respond to both their needs and emotional concerns.

What this paper adds

The nurse-patient relationship is contingent on the patients’ trust of the nurses’ authenticity.

Nurses are not aware that their verbal and non-verbal communication do not always align creating apprehension in patients.

The need for further research from the patient perspective on the authentic behaviours that foster the nurse-patient relationship is warranted.

Implications for practice, theory or policy

A greater emphasis on strategies or models to promote positive nurse-patient relationships in palliative care are needed.

Identification of the various components or phases of the nurse-patient interaction that develop positive relationships perceived by the patient are necessary for optimal, ethical and culturally respectful health outcomes.

Actions to aid in understanding each person’s unique needs are key to person-centred care.

Introduction

Nurse-patient relationships are a core feature of person-centred care in nursing. 1 Nurse-patient relationships have been conceptualised as a key element of holistic care, together with physical and psychosocial dimensions, intrinsically related to the discipline of nursing.2,3 Despite many attempts to define the nurse-patient relationship there is no one universally accepted and used definition. 4 Guiding principles include that the nurse-patient relationship influences care incorporating the person’s perspective; 5 it is holistic, compassionate, mutually beneficial to nurses, individuals and families;6,7 and understood to be safe and respectful. 8 The nurse-patient relationship has also been referred as relationship-centred care, 9 a caring relationship, 6 patient-centred care, 3 and person-centred care. 4

The philosophy of person-centred care is described as basic, human kindness and respectful behaviour, 4 where care is impacted by the very nature and quality of that relationship. 10 Critical to the success of the nurse-patient relationship is an awareness and sensitivity to the patient’s preferences, their responses and reactions, 11 ensuring respectful and tailored care,6,12 that is therapeutic.13,14 Patients from across all healthcare settings report valuing personalised treatment and positive interpersonal communication. 14 Patients report placing great significance on being treated with care, respect and dignity, and nurses connecting with each patient through simple acts of kindness. 15 Patients value being seen as a person, who is deserving of being treated respectfully with authentic compassion, 16 with equal merit, 17 and being included in decision-making.18,19 Several issues exist on how the nurse-patient relationship is measured stemming primarily from a lack of conceptual and theoretical clarity around what constitutes the nurse–patient relationship. 20 First and foremost is the context in which the nurse-patient relationship is developed or exists, which constitutes the context of care. The Fundamentals of Care Framework has been promoted as key to explaining and guiding person-centred care, emphasising the importance of developing trust with the patient, anticipating patient needs and knowing enough about the patient to respond appropriately. 3 The context of care as described in the framework is expressed in terms of policy and system level factors more readily applied to inpatient settings. 3 Whilst the lack of specificity around the context of care has been recognised as a limitation to the framework, 12 the framework does emphasise the importance of the nurse-patient relationship as part of person-centred care in inpatient settings.

It is posited that identifying the ways in which nurses can develop relationships with patients when they encounter a range of challenges might be more useful. 20 While there is significant rhetoric about the value of the nurse-patient relationship in person-centred care, 4 how nurses foster a positive and therapeutic relationship is less clear. 11 Rather, a person-centred approach to care that focuses on authentic shared decision-making and empowerment form the base on which the nurse-patient relationships develops.21,22 Evidence about nurse-patient relationships in palliative care from the patient’s perspective are comparatively limited. 3 A previous review which explicated researcher concerns that asking patients with a life-limiting illness to participate in research was too burdensome, or even unethical 23 may partially account for this. Thus, building a comprehensive understanding requires that patient and nurse perspectives are examined together. Therefore, the aim of this integrative review was to identify and synthesise the research evidence on how nurse-patient relationships (i) are fostered in inpatient specialist palliative and hospice care services and settings and (ii) perceived from the nurse and patient perspectives.

Methods

Design

This integrative review was undertaken to answer the research question, using an approach similar to the preliminary stages of (i) problem identification, (ii) literature search and (iii) data evaluation described by Whittemore and Knafl. 24 Reporting of this review was guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. 25 The integrative review protocol was registered prospectively with Prospero #CRD42022336148, and updated in April 2023.

Search strategy

A comprehensive search of five electronic databases was initially conducted in June 2022 and updated in December 2023. Databases searched were CINAHL Complete, PsycINFO, MEDLINE (via OVID), PubMed and Web of Science, guided by the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1).

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Peer reviewed publications Primary research conducted in specialist inpatient palliative care or hospice settings* # Sample/participants include Adults over the age of 18 diagnosed with a life-limiting illness receiving palliative care in a specific palliative care unit or hospice, and/or Their significant others (such as family and carers), and/or Registered and/or enrolled nurses who cared for adult patients (>18 years old) Focus on the nurse-patient relationship Published in English |

Abstracts, letters to the editor, opinion pieces or education-focused pieces Sample includes other health professionals or professional groups, where the data are not separated. Patient sample includes children or adolescents, and /or significant others, under 18 years of age, where the data are not separated |

Where a study included non-inpatient settings, only data/quotes pertaining to inpatient settings were extracted.

Where a study included mixed participant groups, only data pertaining to participants involved in inpatient care were extracted.

A search strategy was developed with a health-sciences librarian and used MeSH terms for the concepts: ‘nurse’, ‘nurse-patient’, ‘patient’ and ‘relationship’ with combinations of terminal* OR palliative OR ‘end of life’ OR ‘hospice care’ AND ‘nurse-patient’ OR ‘nurse-client’ AND interact* OR relation*. The phenomenon of interest was nurse-patient relationships in specialist palliative care or hospice care inpatient settings. Results were limited to English language, with no time limit applied (Table 2).

Table 2.

Search terms used in the integrative review.

| Search term type | Concept 1 | Concept 2 | Concept 3 | Concept 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Keywords | Terminal* or palliative or ‘end-of-life’ or hospice | ‘Nurse-patient’ or ‘nurse-client’ or ‘patient-nurse’ or ‘client-nurse’ | Adult* | Interact* or relation* or connect* |

| Subject headings | ||||

| Medline/PubMed (MeSH) | Terminal Care/ or Palliative Care/ or Hospice Care/ or Terminally Ill/ | Nurse-Patient Relations/ | exp Adult/ | |

| PsycINFO | Palliative Care/ or Hospice/ or Terminally Ill Patients/ | Therapeutic Processes | ||

| CINAHL complete | MH = ‘Terminal Care’ or ‘Palliative Care’ or ‘Hospice Care’ or ‘Terminally Ill Patients’ or ‘Hospice Patients’ | MH = ’Nurse-Patient Relations’ | MH = ’Adult+’ | |

| Web of Science | Keywords only | |||

The search yielded 1763 citations, which were imported into EndNote v.20. 26 Duplicate citations were removed in EndNote and the remaining citations were exported to Covidence, 27 where additional duplicate citations were automatically identified and removed. Citations were independently screened first by title and abstract, then full text, by two members of the research team. Conflicts were resolved by team consensus.

Quality appraisal

Quality appraisal was undertaken independently by three members of the research team to assess the quality, methodological rigour and risk of bias of each study included in the final review using the Mixed Methods Assessment Tool (MMAT). 28 Discrepancies were discussed by all members of the research team until final scores were agreed upon. Regardless of the MMAT scores, all articles meeting the inclusion criteria were included because it was considered they may include valuable data. Factors that contributed to lower scores are detailed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Characteristics of included studies.

| Author (year of publication), country | Study aim and design | Setting and sample | Findings | Quality appraisal MMAT scores | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % of criteria met | Comments | ||||

| Aghaei et al. (2023), Iran | To explore the meaning of care in the process of providing palliative to care to Iranian people with cancer and to develop a theory that would explain the phenomenon. Grounded theory interviews. |

Inpatient palliative care offered by healthcare centres and charitable institutions in Tehran. Registered nurses (n = 9). Patients (n = 4). Others (n = 8). |

Building emotional connection, reinforcing patient’s positive mindset, having a core value in care, understanding the difficult state of patient, cooperation of various care resources, inner peace of patients and psychological distress of healthcare providers. Healthcare providers have tried to reduce the affection and anxiety of patients by understanding their difficult state; they have applied different strategies that have constructed a care process. | 80 | There is a lack of coherence between the qualitative data sources, collection, analysis and interpretation. |

| Barnard et al. (2006), Australia | To describe the qualitatively different ways a group of Australian nurses‚ understood their experience of being a palliative care nurse. Phenomenology using interviews. |

Inpatient palliative care unit in a 317-bed regional hospital. Registered nurses (n = 10). |

Nurses understood their experience as journeying with their patients through the final phases of the person’s life. The journey involved the patient, his/her family and members of the healthcare team. Five ways of being a palliative care nurse included (1) doing everything you can, (2) developing a closeness, (3) working as a team, (4) creating meaning about life and (5) maintaining myself. | 80 | There was no clear qualitative research question(s) resulting in a lack of coherence between the qualitative data sources, collection, analysis and interpretation. |

| Bottorff et al. (1998), Canada | To explore and describe patients’ experiences of making choices related to their personal and nursing care routines. Grounded theory using observation and interviews. |

Inpatient palliative care units in two hospitals. Patients (n = 16). |

Patients used three ways to communicate their choices: initiating requests, responding to offers, and ‘letting go’ or handing over the responsibility. Refusals made up a significant number of choices. | 80 | The interpretation of results may not sufficiently substantiate the data. There is a lack of participant voice in the results, and no notation as to who comments were made by. |

| Bottorff et al. (2000), Canada | To investigate the ways nurses support or restrict patients’ participation in their care. Grounded theory using secondary analysis. |

Inpatient palliative care units in two hospitals. Nurses (n = 32) observed. Nurses (n = 12) interviewed. |

Nurses took control when they perceived that compromised physical or cognitive status threatened patient safety. Nurses’ efforts to support patients’ participation in decision making are represented in a four-phase process. | 80 | The interpretation of results may not sufficiently substantiate the data. There is a lack of participant voice in the results, and no notation as to who comments were made by. |

| Byrne and McMurray (1997), Australia | To reveal the essence of a complex human and social phenomenon of hospice nurses’ experiences in caring for dying patients. Phenomenology using interviews. |

Hospice with 26 beds. Registered nurses (n = 9). |

Assisting dying patients had changed the nurses’ perspectives on life and death. The essence of the nurses’ experience of caring for dying patients is embedded in five key themes that structured the experience: being transformed by the experience; the influence of the context on caring; the embodiment of caring; caring for the family and coping. | 100 | |

| Canzona et al. (2018), USA | To investigate challenges nurses face when providing care for oncology patients transitioning from curative to palliative care and to identify educational and support opportunities for nurses. Phenomenology using interviews. |

Acute inpatient oncology and palliative care units in hospital. Oncology nurses (n = 14). Palliative care nurses (n = 14). |

Four themes (a) coping with interpersonal communication errors during the transition, (b) responding to patient/family reactions to miscommunication about the goals of care, (c) navigating emotional connection to patients and (d) adapting to sociocultural factors that influence information exchange. | 100 | Unable to ascertain if consent was obtained. |

| Clover et al. (2004), Australia | To explore patients’ understanding of their discussions about end-of-life care with nurses in a palliative care setting. Modified grounded theory using interviews. |

Inpatients of a palliative care program. Patients (n = 11). |

Analysis revealed six approaches that patients in palliative care used which were dependant on the type of decision they needed to make: wait and see, quiet acceptance, active acceptance, tolerating bossiness, negotiation and being adamant. | 100 | |

| Dean and Gregory (2005), Canada | To extensively describe occasions where humour and laughter occurred; the functions served by humour and laughter; and the identification of circumstances where humour and laughter were experienced or observed as inappropriate in the context of palliative care. Clinical ethnography using observations and interviews. |

Inpatient palliative care unit with 30 beds. Nurses (n = 17). |

Functions of humour in palliative care include; building relationships, contending with circumstances and expressing sensibility. | 100 | |

| Georges et al. (2002), Belgium | To describe the perceptions of nurses about the nature of their work as palliative care nurses and to gain insight into the problems they experience. Qualitative using observation. |

Inpatient palliative care unit in an academic cancer hospital. Nurses (n = 24). |

Two main perceptions emerged from the data: ‘striving to adopt a well-organised and purposeful approach’ and ‘striving to increase the well-being of the patient’. These perceptions are divergent and lead to a different approach to patient care and to one’s own reality as a palliative care nurse. | 100 | Unable to ascertain if consent was obtained. |

| Hill et al. (2014), United Kingdom | To examine the association between familiarity and the provision of psychosocial care by professionals in a hospice setting. Grounded theory using observation, interviews, organisational and documentary analysis. |

Inpatient specialist palliative care unit with 24 beds. Nurses (n = 38). Patients (n = 47). |

Psychosocial support can be provided on a patient’s first contact and does not rely on building a professional patient relationship. | 100 | |

| Hill et al. (2015), United Kingdom | To explore patients’ expressions of psychosocial needs and nurses’ responses to them in a hospice setting. Secondary analysis of original study. |

Inpatient specialist palliative care unit with 24 beds. Nurses (n = 38). Patients (n = 47). |

Nurses immediately respond to patients’ psychosocial needs in one of four ways: ‘dealing’, ‘deferring’, ‘ducking’ or ‘diverting’. | 80 | The rationale for using mixed methods design was not described. Study was observational and interviews. |

| Isaacson and Minton (2018), United States | To understand the communication practices used by rural and urban hospice/palliative care nurses when engaging patients and families in decision-making at EOL. Qualitative using interviews. |

Inpatient hospice/palliative care. Nurses (10). |

Nurses guide and orchestrate communication using skills as information broker, patient advocate and supporter; concepts of trust, honesty, attentive listening, presence, contact and repetition. | 100 | |

| Johnston and Smith (2006), United Kingdom | To explore the perceptions of patients and nurses of palliative care, and particularly the concept of the expert palliative nurse. Qualitative using interviews. |

Two acute care hospitals and two inpatient hospices. Registered nurses (n = 22). Patients (n = 22). |

Expertise in palliative care nursing was defined by patients and nurses as having relationships with patients, involving effective communication skills, providing comfort and knowledge. Psychological aspects of care, particularly interpersonal communication, are more important than physical aspects of palliative nursing. Dying patients can, and wish to, participate in research. | 100 | |

| Johnstone et al. (2018), Australia | To explore and describe the specific processes that nurses use to foster trust and overcome possible cultural mistrust when caring for older immigrants of non-English speaking backgrounds hospitalised for end-of-life care. Qualitative using interviews. |

Four metropolitan health services offering inpatient palliative care. Registered nurses (n = 22). |

Fostering trust encompassed 3 commensurate stages: establishing trust, strengthening trust and sustaining trust. Moral commitment to fostering trust as an essential ingredient of quality end-of-life care. | 100 | There was no clear qualitative research question proposed with the aim only presented in the abstract. |

| Keall et al. (2014), Australia | To investigate the facilitators, barriers and strategies that Australian palliative care nurses identify in providing existential and spiritual care for patients with a life-limiting illness. Qualitative using interviews. |

Inpatient palliative care services in community, inpatient unit in an acute hospital within a major city, large metropolitan area, semi-rural and remote rural areas. Palliative care nurses (n = 20). |

The development of the nurse-patient relationship requires good communication skills and ‘creating openings’ to facilitate care. Barriers included lack of time, skills, privacy and fear of what they might uncover unresolved symptoms and differences in culture or belief. | 100 | Unable to ascertain if ethics was obtained. |

| Kozlowska et al. (2012), Poland | To ascertain what methods of communication nurses used during interactions with patients nearing the end of their lives, with a particular focus on non-verbal communication. Quantitative using survey. |

Five inpatient hospices. Nurses (n = 95). |

Nurses (48%) used non-verbal communication consciously and with a certain aim and 37% reported that they sometimes did. Compassion was expressed through, holding patients’ hand, silently keeping company, smiling, sustaining eye contact (22% compassion is expressed through verbal contact). | 80 | Unable to determine if ethics was obtained. A survey as a measurement was deemed not the best tool to answer the research question. |

| Kwon et al. (2020), South Korea | To explore the sensitive nursing care provided by nurses who care for terminally ill individuals with cancer. Qualitative using a 5-point Likert scale of 48 questions; individual interviews (face-to-face, telephone and email). |

Nine specialised inpatient urban hospices. Nurses (n = 20). 16 Hospice specialist nurses; 4 non-specialist hospice nurses with hospice training. |

Analysis of the nurses’ sensitive nursing care revealed two dimensions consisting of sensitive attitudes and sensitive nursing behaviours. A sensitive nursing attitude was a prerequisite for sensitive nursing behaviour. Four sensitive attitudes included; reflective thinking, an accepting attitude toward death, intuition and open-mindedness. Four sensitive nursing behaviours included; listening, responding to patients in a manner suitable to their conditions, quickly responding to patients’ problems and providing a moment saying farewell). |

100 | |

| Langegard and Ahlberg (2009), Sweden | To increase knowledge of what patients with incurable cancer have found consoling during the course of the disease. Qualitative, descriptive method, cross-sectional analysis using semi-structured interviews. |

Inpatient hospice. Patients (n = 10). |

‘Being seen’ to be seen and, therefore consoled results from experiencing a sense of connection, self-control, affirmation and acceptance. | 100 | |

| McCabe et al. (2012), Australia | To describe palliative care nurses’ confidence and skills as well as their perception of the barriers to working with depressed patients. Qualitative using survey. |

Three inpatient palliative care services. Nurses (n = 69). |

One-third reported low confidence in recognising depression, two-thirds endorsed lack of training and knowledge to detecting depression, one-third indicated lack of confidence in monitoring symptoms of depression. | 100 | |

| McCallin (2011), New Zealand | To generate a grounded theory of nursing practice in end-of-life care. Qualitative using semi-structured interviews. Theoretical sampling and memo writing furthered theoretical development. |

Two hospices, an aged care facility, an acute paediatric hospital and an acute care hospital all offering inpatient care. Registered nurses (n = 30). |

The main concern for nurses in end-of-life care was that patients, families and nurses had different expectations of how end-of-life care might be managed. Nurses used the process of moderated guiding to manage different expectations in end-of-life care. Nurses preferenced patient/family would control what happened at the end-of-life; often expectations were idealistic, and patient and/or family had no idea what to expect. | 100 | Unable to ascertain if consent was obtained. |

| Minton et al. (2018), United States | To describe rural and urban palliative/hospice care nurses’ communication strategies while providing spiritual care for patients and families at end of life. Qualitative using individual interviews. |

Rural and urban hospices and nursing home settings offering inpatient palliative care. Palliative/hospice care nurses (n = 10). |

Sentience includes the capacity to act, a willingness to enter the unknown and the ability to have deep meaningful conversations with patients regardless of the path it may yield. Subthemes include Willingness to go there, being in ‘A’ moment and sagacious insight. | 100 | |

| Mok and Chiu (2004), Hong Kong | To explore aspects of nurse-patient relationships in the context of palliative care. Qualitative using interviews. |

Palliative care unit and service. Hospice nurses (n = 10). Patients (n = 10). |

Four major categories were described (1) forming a relationship of trust, (2) being part of the family (3) refilling with fuel along the journey of living and dying, (4) enriched experiences. It is the nurse’s personal qualities and skills, which are embedded in these relationships, that constitute excellence in nursing care. | 100 | |

| Munkombwe et al. (2020), Zambia | To explore the experiences and views of nurses regarding nonpharmacological therapies of chronic pain management in palliative care. Qualitative using interviews. |

Hospital based inpatient palliative care, hospice and community palliative care. Nurses (n = 15). |

Four categories were described: ‘building and sustaining favourable therapeutic relationships’, ‘recognising the diversity of patients’ needs’, ‘incorporating significant others’, ‘recognising the existence of barriers’. | 100 | |

| Pereira et al. (2023), Portugal | To understand the ways and means of comfort perceived by the person at end-of-life hospitalised in a palliative care unit, their family and health staff as well as the value of the nurse in this process. Qualitative using observation and interviews. |

Palliative care unit within an acute hospital. 57 Participants. Nurses (n = 9). Other clinicians (n = 12). Patients (n = 18). Family members (n = 18). |

The nurse was identified as a privileged player, an essential role in all phases; playing a very important role in end-of-life comfort, which is based on a predisposition for end-of-life care (active listening, empathy, congruence and biographical narrative) and focused attention (global care, attention to detail, family support and opposition to therapeutic obstinacy). | 60 | There was no clear qualitative research question for the data to address. Findings are not substantiated or interpreted sufficiently by the data. |

| Piredda et al. (2020), Italy | To explore palliative care nurses’ experiences and perceptions regarding patient dependence. Qualitative using interviews. |

Inpatient palliative care centre. Nurses (n = 16). |

Nurses strive to build and maintain relationships helping patients to accept dependence, bringing meaningful life experiences for their nurse and the patient. | 100 | |

| Sacks and Volker (2015), United States | To develop an inductive theory describing the process that hospice nurses use to identify and respond to patients’ suffering; coping strategies with patients suffering. Grounded theory using semi-structured interviews. |

Five inpatient hospices. Nurses (n = 22; 18 registered; 4 vocational). |

Four phase process of carefully cultivated nurse-patient relationship designed to build trust. Participants recognised importance of self-care but had difficulties naming strategies of self-care. | 100 | |

| Samarel (1989), United States | To describe and analyse the ways registered nurses interact with terminally ill patients in a hospital-based hospice unit. Clinical ethnography using participant observations and unstructured informal interviews. |

Combined hospice and acute care unit with 35 inpatient beds. Registered nurses (n = 10). Patients (n = 278). |

Data analysis revealed that patients’ responsiveness rather than ‘acute’, or ‘terminal’ labels determined the quality of the nurses’ interactions with them. Humanistic caring was found to be the unifying focus for both acutely ill and terminally ill patients. | 100 | |

| Samarel (1989), United States | To explore the ways a group of hospice nurses met the needs of a varying patient population. Clinical ethnography using observation and interviews. |

Combined hospice and acute care unit with 35 inpatient beds. Registered nurses (n = 10). |

Basic needs or caring remain the same for the acutely ill and the terminally ill patient. Role transition did not demonstrate role conflict. | 100 | |

| Shimoinaba et al. (2014), Japan | To explore the type of relationship and the process of developing these relationships between nurses and patients in palliative care units in Japan. The special contribution that culture makes was examined to better understand the intensity of nurses’ grief after the death of their patient. Grounded theory using open-ended question interviews. |

Inpatient palliative care units. Registered nurses (n = 13). |

Significant cultural influences emerged both in the type of relationship nurses formed with patients and in the way they developed relationships. The type of relationship was termed ‘human-to-human’, meaning truly interpersonal. The cultural values of ‘Uchi (inside) and Soto (outside)’ have particular implications for the relationship. Four actions (1) Being open, (2) Trying to understand, (3) Devoting time and energy and (4) Applying a primary nurse role, were identified as strategies for nurses to develop such relationships. The quality of this deeply committed encounter with patients caused nurses to grieve following patients’ death. | 100 | |

| Stenman et al. (2023), Sweden | To gain a deeper understanding of how nurses in palliative care experience and describe confidential conversations with patients. Qualitative secondary analysis of data from a primary study. |

Specialised inpatient palliative care units. Registered nurses (n = 17). |

Creating an interpersonal relationship, regardless of time and occasion was important. The confidential conversation required the nurse to gain trust when sharing urgent issues about life and death and manage the responsibility afforded to them. Confidential conversations were unpredictable, and often took place during the performance of other caring activities. The confidential conversation could be a way to safeguard the patient. | 80 | The examples did not always provide a sufficient explanation of the claim. |

| Strang et al. (2014), Sweden | To describe nurses’ reflections on existential issues in communication with patients close to death. Qualitative using group reflections sessions over an 8-week period. |

Three inpatient hospices, six hospital oncology wards and two palliative homecare teams. Nurses (n = 98). |

Three domains and nine themes emerged. The content domain of the existential conversation covered living, dying and relationships. The process domain dealt with using conversation techniques to open up conversations, being present and confirming. The third domain was about the meaning of existential conversation for nurses. The group reflections revealed a distinct awareness of the value of sensitivity and supportive conversations. | 100 | Unable to ascertain if consent was obtained. |

| Walker and Wentworth (2017), New Zealand | To explore palliative care nurses’ experiences providing spiritual care to their patients who are facing a life-limiting illness. Qualitative using semi-structured in-depth interviews. |

Three inpatient hospices. Nurses (n = 18): 9 palliative care nurses; 6 staff nurses, 3 clinical nurse specialists. |

Challenges identifying and defining spiritual distress and complexity in provision of spiritual care. Focusing on individual patients and developing relationships enabled patients’ needs to be met. | 100 | |

| Wu and Volker (2009), Taiwan | To explore the experiences of Taiwanese nurses who care for patient who die within hospice settings. Qualitative using individual interviews. |

Inpatient hospice settings. Registered nurses (n = 14). |

Four themes: Entering the hospice speciality, managing everyday work, living with the challenges and reaping the rewards. | 100 | |

Data extraction

Data about key features including authors, year of publication, country, purpose/aim, setting and context, sample, study design, data collection method/s and key findings were extracted into a spreadsheet (Table 3). Where a study included data from participant groups who did not meet the inclusion criteria, or from alternate settings, such as oncology wards, these data were not extracted. Guided by the Fundamentals of Care Framework, 3 which specifically describes context of care factors relating to inpatient settings, this review was limited to a focus on inpatient settings to help ensure findings were not influenced by differences in models of care, workload and time allocation, previously posited as confounders when examining nurse-patient relationships in cancer care 29 and nurses’ roles across inpatient and community palliative care contexts. 30

Data analysis and synthesis

For data analysis and synthesis, narrative synthesis as described by Popay et al. 31 was used. Narrative synthesis emphasises the use of words to explain and summarise findings, and to ‘tell the story’ of included studies. 31 Popay et al.’s 31 guidance does not represent definitive or prescriptive rules for approaching narrative synthesis, nor is a wholly linear approach suggested. Rather, this approach was used because of the emphasis on story-telling to guide organisation of data from included studies, and consideration of potential patterns or relationships in the data. 31 From a practical perspective, this approach allowed shared concepts and like ideas from both qualitative and quantitative research, to be grouped into themes, thereby forming the story. 31 Analysis was initially undertaken independently by the lead researcher using an iterative approach to enable identification of commonalities and differences, allowing for grouping of data according to similarities, common features and relationships. 31 A second reviewer then reviewed the preliminary findings so that any differences or disagreements could be resolved, and to enable refinement. The synthesis was then reviewed by the remaining members of the research team until the final findings could be determined.

Results

Search results

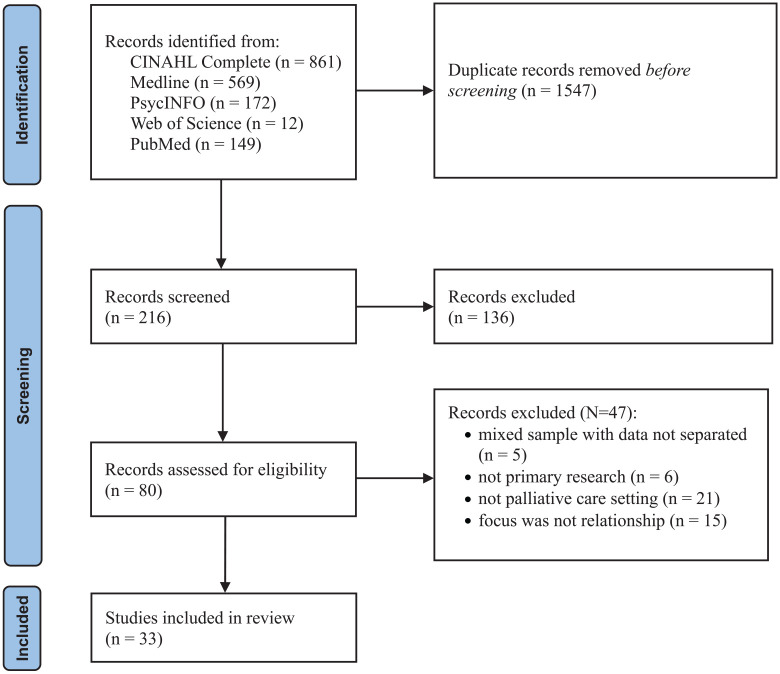

The decision trail for the search is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Decision trail of included studies (PRISMA flow chart). 25

CINAHL: cumulative index to nursing and allied health literature.

In total, 33 papers from 31 studies published between 1989 and 2023, were included, with three papers reporting different components of the same study. Studies were conducted in the United States of America (n = 6),32 –37 Australia (n = 6),38 –43 Canada (n = 3),44 –46 Sweden (n = 3),47 –49 United Kingdom (n = 3),50 –52 New Zealand (n = 2),53,54 and one each in Belgium, 55 Hong Kong, 56 Iran, 57 Italy, 58 Japan, 59 Poland, 60 Portugal, 61 South Korea, 62 Taiwan, 63 and Zambia 64 (Table 3).

Study designs included qualitative (n = 29),32 –42,44 –49,52 –59,61 –64 survey (n = 2),43,60 and mixed methods designs (n = 2).50,51 In terms of quality, one study scored 60%, seven studies scored 80% out of a possible 100%, and the remaining studies (n = 26) scored 100% (Table 3). Studies were conducted in inpatient hospital palliative care units and inpatient community-based hospice care units, across metropolitan, rural and remote settings. Synthesis revealed four main themes (i) creating connections; (ii) fostering meaningful patient engagement, (iii) negotiating choices and (iv) building trust (Table 4).

Table 4.

Themes, subthemes, units of meaning.

| Theme | Subtheme | Units of meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Creating Connections Aspects of forming the therapeutic relationship that supported the provision of person-centred care. |

Engaging authentically | Being with/silence Being available/approachable |

| Seeing the person | Individual choice Understanding the experience |

|

| Being empathetic | Being present Therapeutic touch Belonging/Spirituality |

|

| Fostering meaningful patient engagement Strategies used in communication, specifically when initiating and building relationships, negotiating choices and building trust. |

Hearing the person/Listening with intent | Requests are voiced directly or indirectly Withholding information or changing the topic Humour |

| Being with the person | Responding to/eliciting emotional cues Using non-verbal strategies |

|

| Working together | Providing information Willingness to ask difficult questions. Priorities and preferences are not always aligned |

|

| Negotiating choices Negotiation was used by patients and nurses in the provision of palliative care with a view to facilitating and collaborating towards person-centred care. |

Meeting the persons needs | Patients and nurses both have expectations of the interaction |

| Compromising | Negotiating nursing care Nurses are bound by timeframes; Patients’ timeframes fluctuate. Presenting options/choices Patients consider nurses’ workloads and other patients |

|

| Building trust Trust was integral to initiating, building and sustaining a nurse-patient relationship. |

Trust is built upon actions | Nurses are task focused |

| Trust is built over time | Factors that facilitate trust Nurses are trustworthy Trust gained enables collaborative partnerships |

Creating connections

Thirty-one studies provided detail about creating connections between patients and nurses,32 –52,54 –63 resulting in three sub-themes about the importance of (1) engaging authentically, (2) seeing the person and (3) being empathetic.

Engaging authentically

Engaging authentically during the provision of care, and demonstrating compassion was identified as key to creating connections with patients.33,34,38,43,52,54,55 Of the studies that included patients, authenticity was prominent when it came to connecting with the nurse.36,40,43 –47,50,51,56 Authenticity and genuine interest included the ability of the nurse to see the person and anticipate their needs.43,47,54,57 Authenticity was expressed differently between individuals, but understood when behaviours were genuine.42,43,46,54 Nurses reported that in order to respond to patients needs authentically, familiarity was necessary to increase interpersonal connections, which in turn, improved their ability to anticipate and respond to patient’s needs.50,51,56,58 This familiarity was described by nurses as beyond superficial, being like family, 56 sharing something of themselves,38,41 and reciprocal self-giving. 58 Familiarity was also explained by a patient as:

Everybody gets to know you and they know your illness and they know how to treat you and take an interest in you personally. (p. 705) 52

But importantly, as this hospice patient stated, familiarity was not essential if the nurse demonstrated genuine interest:

It’s not necessary to know the person who listens well as long as he or she signals that there is time. (p. E104) 47

Connecting through authentic behaviours also permitted the use of humour to strengthen connections.43,46 Connections between the nurse and patient were also strengthened through presence.33,34,41,42,54,55,61 Presence was also acknowledged as life-giving, spiritual, 34 comforting,34,54 demonstrating compassion, 33 kindness, 54 and empathy,34,35,41,42,54,59 requiring the nurse to be witness to, and acknowledge the patient’s suffering.35,49,52,54,59,61 Being present with a patient at times of great distress and acknowledging their suffering was important to authenticity, in spite of the potential for personal emotional drain, as a nurse described:

. . . sitting with the pain . . . I spent a lot of the night with him; sitting next to him. It was horrible but I had to do it. (p. 22) 54

Importantly however, another nurse reflected on how presence was only useful if it was authentic, purposeful and meaningful:

Presence or just being, can be a way of providing spiritual care, but you have to establish a rapport first. Otherwise, it can be misinterpreted. Otherwise, it can be like, ‘What’s she doing here? She hasn’t got anything to offer’. (p. 22) 54

The importance of presence to engaging authentically was also described by a patient:

The conversations, the silences too. There was a night when I felt very anxious and afraid to fall asleep . . . The nurse spent the whole night here with me in the room. We talked and even when I fell asleep, she stayed there. Incredible professional and incredible human being. (p. 9) 61

Humour was used by nurses and patients to create connections,43,46,48,61 initially on a superficial level but then as a means of contending with the tension and emotional aspects of the relationship and setting.46,48 Nurses were rarely conscious or deliberate in the use of humour whilst more often patients used humour to convey critical aspects of their care and situation. 46

Seeing the person

The importance of viewing the entire person, not just a patient and a list of tasks,33,39,43,46,47,51,52,54,56,57,63 acknowledging and respecting each patient’s values and beliefs, address spiritual and existential needs, acknowledging a patient’s purpose and meaning were identified as key to building connections.34,35,37,39,42,47,49,52,54,57,59 As a nurse described, to connect and know the patient deeply is crucial:

. . . You have to know their lived experiences. (. . .) You have not only to listen to words but also to observe the nonverbal language, because he wants to tell you something different. (p. 334) 58

Viewing the person holistically required nurses to seek to know and understand each person, and their needs,35,39,57 such as:

. . . I observe suffering with my eyes and with my heart. I can see he wasn’t sleeping, so I talked with him a bit. He’s worried. He’s leaving a young family. I sense it. You can hear it in the tone of their voice, and you can see it . . . and they make little comments. (p. 494) 35

Another nurse reflected on seeing the loss of self-identity that occurs with a terminal diagnosis, connecting to validate the patient’s experience:

And when someone has been given a terminal diagnosis, there’s the pain of a loss that’s impending. And it’s the greatest loss any of us will ever suffer because it’s the loss of ourselves. (p. 492) 35

Engaging empathetically

Behaviours that demonstrated engaging empathetically were noted in 19 studies.32,34 –37,39,42,43,47,48,51,54,55,57,59,60,62,63 Empathic engagement was described as being an active listener,33,39,42,43,47,51,55,62 offering advice, 51 providing emotional and physical comfort.33,57,59,62 A patient shared a description of a nurse who listened and therefore consoled them:

One of my caregivers is on a very professional level . . . I receive a lot of consolation from her . . . I think about how she consoles me . . . When I leave her, I feel stronger, mostly. She listens and tries to make me put my feeling into words. (p. E104) 47

Empathy is an inherent quality of humanistic caring which was embodied by one nurse:

It’s subjective. You can’t be objective and care or you don’t have a heart . . . Commitment to their humanness; totally separate from what’s wrong with ‘em. (p. 321) 37

By touching, 54 hugging, 37 holding hands36,60 nurses believed they were providing tangible symbolic gestures of concern, acknowledgement and deep feeling towards the patients’ situation, such as :

And then I gave her a big hug. That’s important. That’s the most important thing. Everyone needs that. (p. 318) 37

Similarly, a nurse explained that connecting through purposeful therapeutic touch was:

. . . very strength giving, it’s life giving, it’s love giving, it can smooth hurt, and it can take away fears.(p. 22) 54

Touch was occasionally reciprocated, suggesting that they had made a special connection:

I didn’t know why I had a special connection with some patients’ families. After the patients died, their families hugged me and cried just like I was part of their family. (p. 580) 63

Other nurses knew they had created connections by the way patients and families let them know. 41 Creating connections was sometimes unexpected, as this nurse described:

Sometimes the patient will do something, and it’s like my heart opens up. It’s like a feeling of warmth or something. I had 1 patient; he was a real bear. I couldn’t find anything good about him. . . . He touched my cheek, and I thought he was going to hit me. But no, all he did was touch my cheek and look at me. And I thought ‘Wow’. He was not a nice patient, but from then on, we got along. (p. 495) 35

When a connection was established, patients felt safe with the nurse, sharing some of their deepest concerns:

When I was caught in the toughest emotional struggle, I chose to disclose my deepest pain to my nurse, although it was not easy for me to tell someone else, I needed help . . . It was a tough situation and the strong trust in her drove me to ease this pain through dialogue with her. (p. 480) 56

In contrast, some nurses recognised that not all patients may be prepared or ready to invest in building the nurse-patient relationship,56,65 still, nurses remained hopeful, acknowledging that it was the patient’s choice.42,55,56 Making connections through caring behaviours was highly valued by both the nurses and patients but was heavily reliant on the nurse’s commitment to the process. 52 Equally, patients were motivated by authentic behaviours such as paying attention, guiding instead of directing and displaying excellent listening skills. 47

Fostering meaningful patient engagement

Nineteen studies provided data about how nurses approached patients for the purpose of creating the relationship and getting to know the person, establishing a partnership and accomplishing the goals of both the nurse and the patient during daily interactions.33,35,37,39,41 –43,47,50,52,54 –59,61 –63 The importance of fostering meaningful patient engagement was evidenced by (1) hearing the person; listening with intent, (2) being with the person and (3) working together. Nurses described being present,41,47,55,57 sitting in silence,42,54,56 listening with intent,35,39,41,42,47,54 –56,59,62 responding to and eliciting emotional cues,47,50,54,56,57,59,63 respecting patients choices50,55,58 and the provision of information35,37 as ways to foster mutual respect and engagement. Patients reported interpersonal skills and the value of the nurse-patient relationship was the most important aspect palliative nursing.35,37,52

Hearing the person; listening with intent

Listening with intent was identified by nurses as being an important aspect of connecting with patients while patients indicated that it demonstrated nurses were interested in them as individuals.39,47,52,57,61 This nurse tells how by simply listening to the patient provided a safe environment for patients to explore their feelings:

. . . Its important to stop and listen. To talk if need be. But sometimes it’s just important to just be with the patient. You’re not there to do things to a patient. You are here to listen. You are to let them say things to you which they need to get off their chest. (p. 22) 54

Actively listening for expressed psychosocial needs gave the nurses opportunity to explore the patient’s anxieties fostering meaningful engagement, as this nurse describes:

If a patient says to me, ‘Am I dying?’ we’re listening to them and talking to them. ‘Do you feel like things are catching up with you?’ ‘Yes, I feel like I’m dying’. And that opens the door. (p. 23) 54

Nurses sought to understand the patient in order to foster meaningful relationships,39,41,54 waiting to be invited in 59 dependent on the patients’ willingness to engage. 56 Occasionally nurses felt they were shut out of a relationship recognising they may need to amend their approach. 58 Others acknowledged that the patient might not be ready to disclose their vulnerability:

When patients only talked to you in a superficial way and did not express their emotions, this indicated they did not want to disclose their intimate feelings. It did not mean they rejected the nurse. They were not ready to disclose their feelings and sufferings. (p. 479) 56

Being with the person

Being with the person was focusing on being present-centred, maintaining or improving the person’s quality of life at that time.35,39,43,56,61 The nurses’ ability to provide person-centred, individualised palliative care whilst interacting with patients was dependent on whether the nurses were busy,37,43,50,52,55 their comfort and skill level,51,52 or if the person was imminently terminal. 37

Nurses acknowledged that confidence and experience were necessary to enable them to connect through use of presence and listening.39,42,52,59

I just listened to the patient. I am with him, with his heart. I may cry with him. What can I say . . . I do not provide anything; I just listen to his heart. I feel it is great if I can support the patient who suffered emotionally and if he is relieved because I listen to. (p. 459) 59

Silence was also recognised as an invaluable aspect of being with the person,42,54,55,61 such as:

Allowing people to talk or allowing silences. One of my mentors told me that you should sit on your hands or if you feel like you should leave don’t – stay a bit longer. (p. 3200) 42

Being with the patient occasionally was an intrusion into the nurse’s workload,43,55 while other nurses understood that it was sometimes the required action:

Sometimes I tell the patient that I do not know. I also try to stay with him, at the patient’s side. You don’t always have to talk; sitting at his side is sometimes enough, the patient may find some peace or someway to cope with his own emptions and thoughts. (p. 790) 55

Patients reported nurses’ ability to convey a sense of security and calm,43,47,52,61 while nurses described the use of presence as a way of providing spiritual care, such as:

. . . Whenever he was in fear and sorrow, I took the initiative to be with him, listened to his feelings, or was just there, and encouraged him, and I found he was changed. (p. 480) 56

Other times, nurses made considerable effort to find time to spend with the patient:

I’m going to go and have another chat with Vera and try to persuade her to stay in a bit longer. But I want to make sure we have plenty of time. (p. 8) 50

Working together

Working together was a culmination of those connecting behaviours of listening with intent and being with the person. 52 It required the nurse to demonstrate expert skills in communication43,66 and a commitment to tackle the difficult questions allowing the nurse and patient to come together in a moment of shared openness:

If a patient says to me, ‘Am I dying?’ we’re listening to them and talking to them. ‘Do you feel like things are catching up with you?’ ‘Yes, I feel like I’m dying’. And that opens the door. (p. 23) 54

Connecting and working together sometimes required nurses to utilise the family, 33 but ultimately it was focusing on what was important to the patient:

If we are directing the conversations instead of letting them direct the conversation, it is two different conversations. So, to really ask questions trying to pull out what’s important to them and then having the discernment and the wisdom to see what you can pull out that’s really important out of that conversation. It takes listening. (p. 10) 33

Negotiating choices

Twenty studies provide data on approaches used by nurses and patients in negotiating choices in meeting the needs of the person;32 –34,37,40,41,44 –46,48,50 –53,55,56,58,59,62,64 presented according to two subthemes: (1) meeting the needs of the person and (2) compromising.

Meeting the needs of the person

Nurses acknowledged that meeting the needs of the patient as a person was essential to fostering nurse-patient relationships,45,59 such as:

It’s a real part of the caregiving to recognize when patients need to make choices and when they need to make as few choices as possible. (p. 9) 45

Meeting the needs of the patient required nurses to identify and act upon the expressed needs,50,52 claiming that familiarity of the patient was necessary to respond to the request. 51 Nurses initially sought patient knowledge and understanding of their needs and perceived capacity to ascertain what choices might be able to be offered,32 –34,41,48,53,56,59,64 while others relied upon their intuition of the patients’ needs. 46 But it was not always realistic to give the patient a choice, as this nurse claimed:

People are autonomous beings. It’s about who has the power or control. . . Working with patients, ultimately, I would like them to have total control, but it has to be moderated according to what is possible, what they are ready for and what they can do at this moment. (p. 2327) 53

Whilst the evidence demonstrated that patients and nurses sought to resolve any issues in a manner acceptable to all, their approaches were diverse. In four studies50,53,55,62 nurses cited recognising the importance of creating a trusting environment and were committed to enabling patient choices for activities related to hygiene,44,58 medications,37,44,58 and general day-to-day activities.37,44,45,58 Patients also negotiated choices either directly or indirectly voicing their needs, by initiating requests, responding either favourably or indifferently to offers and suggestions, and occasionally allowing the nurse to make the final decision:

Even if you end up saying (to the nurse), ‘Well, I don’t care. You decide’. Even if that is the outcome, I think it’s very important that the conversation at least be broached, be started. (p. 11) 44

Compromising

Negotiating choices was about compromise, as in compromising about the goal or objective and the timeframe. When nurses felt that strongly enough about a goal or the task at hand, sometimes opportunities for compromise or negotiation were not provided, particularly when nurses felt it was not realistic, feasible or safe. 53 Rather, nurses described offering pseudo-choices while actually completing the task before the patient could respond, 45 or dissuading the patient altogether. 40 Patients’ expectations of negotiation and compromise also changed over time, such as when the independence lessened, 44 when they trusted the nurse as an expert:

I rather do accept what they freely give me . . . I suppose I have to trust them. What other choice do I have? They are the experts; they have the knowledge and training. (p. 337) 40

Patients did not want to appear demanding when negotiating their choices, with some describing alluding to nurses’ workloads before expressing a request. 44 When requests were not adequately considered or they had not been provided with an adequate rationale, patients’ became persistent,40,44,45 and others resorted to withholding vital information, throwing away offered medications or enlisting families to advocate on their behalf when they felt manipulated. 44 When given too many options at once, or little time to consider them, some patients viewed choice as burdensome, irrelevant or even tokenistic. 45 Patients described feeling coerced, bullied or manipulated, 40 with nurses driving the agenda:

It was just that the nurse had an agenda, a time agenda, and had formed an opinion about what they thought I needed and when I needed it . . . The outcome was rather a nasty confrontation. . . I just got fed up and said that I wanted to be alone and go away. (p. 10) 44

When offered choices, patients considered whether they felt physically or psychologically ready to perform the offered activity of care, sometimes asking the nurse to delay or postpone the cares while they considered all options or until they felt able to.40,44 In contrast, nurses offered choices that fit their timeline, citing time limits, 45 doctors’ orders, 44 senior nurse managers, 40 hospital routines and work constraints 45 as the reason. A nurse shared:

It’s sometimes easy to phrase things so that you get what you want . . . I’ll do that when I know what my day is like and the things that I should get done, how much time that I have, and when my breaks are, and when they might have an appointment or something. Then I’ll phrase questions like that, so it fits into my schedule of the day. (p. 9) 45

Whilst this approach was intended to make the patient feel as though they had choice, both options were about meeting nurses’ timeframes. 45 Conversely, another nurse described how it was important for them to put aside their own agenda, timeframe and focus on the patients need:

‘. . . doing what the patients needed even if they were busy . . .’ and that ‘caring for hospice patients involves not doing what I need, but helping patients when they need’. (p. 4) 62

Building trust

Sixteen studies provided data on how trust is sought, established, sustained and occasionally lost, all requiring constant actions by the nurse, and attentive energy by the patient.33,35,40 –42,45,47,48,52,54,56,58,59,61,63,64 Trust was integral to the relationship,33,35,41,42,56 enabling the patient to feel secure, 41 valued, 52 consoled with a sense of belonging.47,61 There were two themes related to this category: (1) trust is built upon actions and (2) trust is built over time.

Trust is built upon actions

Trust was completely reliant on the actions41,52 and attitudes45,56,61 of the nurse. Trust fostered deeper conversations between the nurse and patient,33,35,42,48,56,59,61 and the utilisation of meaningful presence. 54 Eight studies highlighted that trust was built when nurses listened to the patient, acknowledging their story and being authentically empathetic.33,45,47,56,58,59 Occasionally trust afforded a special connection that nurses likened to being a friend or family.56,63 Early establishment of trust paved the way for nurses to provide person-centred care,35,56 patient advocacy,33,56 forming favourable therapeutic relationships.48,64 Trust supported nurses to console, 47 provide existential care whether the nurse was spiritual or not,42,48 and explore alternative options in the provision of care. 64 Nurses were aware that trust was achieved by getting it right from the start and being seen to be doing the right thing, supporting the patient, as described by this nurse:

. . . the patients know that you are supporting them and are on their side; that you are never going to ‘turn up your nose’ and do what you want to do. (p. 765) 41

Nurses sought to be trusted,48,58 monitored trust as an indicator of the strength of their relationship, 35 and were aware that trust was tenable and could be lost 41 if actions were not congruent to patients wishes. 40 Trust was integral to enabling a therapeutic relationship between the nurse and patient, with both participants watching and waiting for the behaviours that instilled trust. 47 Though it appears patients remained vigilant while some nurses may not have been so vigilant in their actions:

Consolation to me is when I can trust people when someone says, ‘Goodbye then, I’ll soon be back’, . . . and then she really is coming back. If she isn’t, I can’t trust her. But if she is, it’s a great solace. (p. E104) 47

Trust and the relationship can be lost very simply, 52 as one nurse explained:

‘. . . if you don’t have trust, you have no relationship . . .’ and ‘You can lose trust by just not even being able to answer a buzzer or something’. (p. 767) 41

Acknowledging that marginalised people may have an inherent mistrust in the health system, nurses described having to traverse additional hurdles such as language and cultural beliefs in building trust:

That trust and rapport is very different to what other staff have . . . I think it’s because I’m Turkish [and the family thinks] ‘Okay, she speaks our language, she’s of our religion’. (p. 765) 41

Trust was also tenuous, 40 and founded on action, as this patient explains:

They [the nurses] come in smiling – they are always smiling – and present tablets. I ask what are they for and the nurse looks at me blankly and says, ‘They are new, the doctor’s ordered them’. I feel like saying, ‘Well, I don’t care what the doctor’s ordered. Tell me what they are and any side effects and maybe I’ll take them’. (p. 337) 40

Trust is built over time

Some nurses were sensitive to the time it could take for patients to build sufficient trust to express their concerns or preferences. 45 To expedite the process, nurses disclosed personal attributes of themselves to build trust:

When they come to us, we need to get it right at the start. We need to give a bit of ourselves first and give a bit about what we really are here for and how we want to try and support them . . . Maybe then they would feel more comfortable disclosing those kinds of things to us and more comfortable at the start, feeling ‘It’s okay’. (p. 765) 41

The building of trust in the nurse-patient relationship was also described by nurses and patients alike. A nurse suggested trust was an ongoing process:

Trust – I guess you’ve got to feed it. . . to let it grow. And the more that it grows, the better [as] it will make it easier for us and them to be able to do things better. (p. 766) 41

From the patient perspective, trust could be built through advocacy and sharing:

With a trusting relationship, as patient I could tell her everything I need. She would bring my issues to the meeting at the hospital, so my concerns would be heard. It wouldn’t be that way if our relationship were a distant one. The nurse was not only a healthcare professional she was also a good friend, part of the family. (p. 480) 56

Discussion

Main findings

This review had two aims. The first was to identify and synthesise data on how nurse-patient relationships are fostered in specialist palliative care settings, and second, to examine how nurse-patient relationships were perceived from the nurse and patient perspective. These findings have demonstrated that nurses and patients alike are invested in the nurse-patient relationship, with both parties appreciating connections that are fostered, meaningful engagement, opportunities to negotiate choice and build trust.

Whilst this review highlights the complexity and richness of what happens when nurses and patients interact positively, the findings also explicate the consequences when the patient’s perspective is overlooked. Patients and nurses described both opposing and supportive relationships, while some nurses were willing to put the patient first, they cited workloads and daily tasks as activities that may be more favourably considered than engaging meaningfully with patients. Patients, nevertheless, disclosed the richness of the relationship52,56 while others have had to expend energy into creating and maintaining a sense of safety and succour.40,44 Spiritual, existential distress and psychological issues for patients and families have been promoted as areas of important nursing research. 67 Other research has reported that nurses have lost the sensitivity to deliver respectful, compassionate, person-centred care,68 –70 with the provision of palliative care being reduced to a series of checks and tasks within care pathways replacing good clinical practice encompassing empathy, humanity and communication. 71

What this review adds

The nurse-patient relationship is at the core of this review. These findings demonstrate that nurse-patient relationships are fostered using diverse actions, gestures and approaches. Nurse presence, authenticity, familiarity, empathy and ensuring patients were seen, were highly valued by patients, bringing comfort, 54 and a sense of support. 51 Similar to previous research which has demonstrated the perpetual importance of communication in palliative care,72,73 these findings further demonstrate how communication was key to working in partnership with patients in their care. The nurse’s ability to establish rapport, be trusted and be fully present, as part of the nurse-patient relationship was influenced by several factors highlighted in this review. Even when justified according to competing demands in nurses’ workload, resisting patient requests is demonstrative of the power imbalance that exists in the nurse-patient relationship.40,44 For nurse-patient relationships to be therapeutic and/or beneficial for patients, power imbalances must be avoided.

Although the nurse-patient relationship is known to be vital to ensuring safe and effective care, 74 knowing what is important to patients in palliative care and how their experience of care affects them enables health care organisations and nurses to align themselves with the principles of person-centred care. However, these findings suggest it is important not to simply assume that nurses can form positive and/or therapeutic relationships with patients, 75 particularly given that this may not always desired by the patient.56,58 or personal and behavioural barriers exist between the nurse and patient. 13 Nonetheless, given that, by-comparison, the majority of data came from nurses, these findings provide a clear argument for ensuring patients’ voice and experience is more equally considered, if the nurse-patient relationships is to be understood comprehensively and holistically.

Strengths and limitations

One of the strengths of this integrative review was the methodological rigour of the process, which contributes to the trustworthiness of the findings. The inclusion of evidence from multiple countries and heterogenous nature of the evidence also help contribute to the transferability of the findings; in essence because despite the differences, the synergies in nurse and patient experiences were clear. One of the challenges faced in attempting to answer the research question was that there is no universally accepted definition for or meaning of nurse-patient relationship. Compared to the amount of evidence presented from the perspective of the nurse, the paucity of evidence from the patient perspective is a limitation. As it was not possible to include research published in languages other than English, it is possible some research literature may have been missed. Finally, as the search was limited to peer-reviewed published research literature, it is possible that some unpublished research evidence and non-research literature may have been missed.

Conclusion

This review explicates an important perspective on the nurse-patient relationship in palliative care, building understanding on the importance of seeking to understand each person as an individual, including their unique needs, preferences and wishes for care. The evidence demonstrates that nurses’ commitment to being authentic, listening intently and building trust are core to fostering therapeutic relationships in palliative care. Yet, equally, trust cannot be assumed, and relies on nurses’ use of verbal and nonverbal indicators and earning patient trust. These findings emphasise the importance of nurses reflecting upon their approach to person-centred care in clinical practice, their actions and communication style and how these may affect the patient experience and nurse-patient relationship.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the assistance of Ms. Vanessa Varis, Faculty Librarian, Curtin University, for her support with the search strategy.

Footnotes

Author contributions: All authors meet the criteria for authorship as stated by the ICMJE or Australian Code for the Responsible Conduct of Research authorship guidelines. SB was responsible for the planning, design and conduct of the research, including database searching and data extraction. All authors contributed to citation screening. SB and MJB were responsible for data synthesis and led the manuscript development. MJB, EC and GKBH contributed to guiding the review design and conduct and editing of the manuscript. All authors have given final approval of the manuscript to be submitted for publication.

The author(s) declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) declare no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Ethics and consent: The author(s) declare ethics and consent was not deemed necessary for this study or publication of this article.

Data management and sharing: All relevant data are within the manuscript. Any other data are available upon request from the corresponding author.

ORCID iDs: Suzanne Bishaw  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8368-9971

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8368-9971

Melissa J Bloomer  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1170-3951

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1170-3951

References

- 1. Duffy JR, Brewer BB, Weaver MT. Revision and psychometric properties of the caring assessment tool. Clin Nurs Res 2014; 23: 80–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Feo R, Conroy T, Jangland E, et al. Towards a standardised definition for fundamental care: a modified Delphi study. J Clin Nurs 2018; 27: 2285–2299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kitson A. The fundamentals of care framework as a point-of-care nursing theory. Nurs Res 2018; 67: 99–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Byrne AL, Baldwin A, Harvey C. Whose centre is it anyway? Defining person-centred care in nursing: an integrative review. PLoS One 2020; 15: e0229923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Santana MJ, Manalili K, Jolley RJ, et al. How to practice person-centred care: a conceptual framework. Health Expect 2018; 21: 429–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Allande-Cussó R, Fernández-García E, Gómez-Salgado J, et al. Understanding the nurse-patient relationship: a predictive approach to caring interaction. Collegian 2022; 29: 663–670. [Google Scholar]

- 7. World Health Organization. People-centred health care: a policy framework. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8. International Council of Nurses. Nurses: a voice to lead: health for all – nursing, global health and universal health coverage. Geneva: International Council of Nurses, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jonsdottir H, Litchfield M, Pharris MD. The relational core of nursing practice as partnership. J Adv Nurs 2004; 47: 808–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ryan T. Facilitators of person and relationship-centred care in nursing. Nurs Open 2022; 9: 892–899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Molina-Mula J, Gallo-Estrada J. Impact of nurse-patient relationship on quality of care and patient autonomy in decision-making. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020; 17: 835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mudd A, Feo R, Conroy T, et al. Where and how does fundamental care fit within seminal nursing theories: a narrative review and synthesis of key nursing concepts. J Clin Nurs 2020; 29: 3652–3666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kwame A, Petrucka PM. A literature-based study of patient-centered care and communication in nurse-patient interactions: barriers, facilitators, and the way forward. BMC Nurs 2021; 20: 158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ruben BD. Communication theory and health communication practice: the more things change, the more they stay the same. Health Commun 2016; 31: 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Virdun C, Luckett T, Lorenz K, et al. Hospital patients’ perspectives on what is essential to enable optimal palliative care: a qualitative study. Palliat Med 2020; 34: 1402–1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Greenfield G, Ignatowicz AM, Belsi A, et al. Wake up, wake up! It’s me! It’s my life! patient narratives on person-centeredness in the integrated care context: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res 2014; 14: 619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bylund-Grenklo T, Werkander-Harstäde C, Sandgren A, et al. Dignity in life and care: the perspectives of Swedish patients in a palliative care context. Int J Palliat Nurs 2019; 25: 193–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Giusti A, Nkhoma K, Petrus R, et al. The empirical evidence underpinning the concept and practice of person-centred care for serious illness: a systematic review. BMJ Glob Health 2020; 5: e003330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Marti-Garcia C, Fernández-Férez A, Férandez-Sola C, et al. Patients’ experiences and perceptions of dignity in end-of-life care in emergency departments: a qualitative study. J Adv Nurs 2023; 79: 269–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Feo R, Kumaran S, Conroy T, et al. An evaluation of instruments measuring behavioural aspects of the nurse-patient relationship. Nurs Inq 2022; 29: e12425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Van Humbeeck L, Malfait S, Holvoet E, et al. Value discrepancies between nurses and patients: a survey study. Nurs Ethics 2020; 27: 1044–1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wiechula R, Conroy T, Kitson A, et al. Umbrella review of the evidence: what factors influence the caring relationship between a nurse and patient? J Adv Nurs 2016; 72: 723–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bloomer MJ, Hutchinson AM, Brooks L, et al. Dying persons’ perspectives on, or experiences of, participating in research: an integrative review. Palliat Med 2018; 32: 851–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs 2005; 52: 546–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev 2021; 10: 89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. The EndNote Team. EndNote. Philadelphia, PA: Clarivate, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Veritas Health Innovation. Covidence systematic review software. Melbourne, Australia: Veritas Health Innovation, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hong QN, Pluye P, Fàbregues S, et al. Mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT). Montreal: McGill University, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Walker S, Zinck L, Sherry V, et al. A qualitative descriptive study of nurse-patient relationships near end of life. Cancer Nurs 2023; 46: E394–E404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sekse RJT, Hunskår I, Ellingsen S. The nurse’s role in palliative care: a qualitative meta-synthesis. J Clin Nurs 2018; 27: e21–e38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews: a product from the ESRC methods programme. Lancaster: Lancaster University, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Canzona M, Love D, Barrett R, et al. ‘Operating in the dark’: nurses’ attempts to help patients and families manage the transisiton from oncology to comfort care. J Clin Nurs 2018; 27: 4158–4167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Isaacson MJ, Minton ME. End-of-Life Communication: nurses cocreating the closing composition with patients and families. Adv Nurs Sci 2018; 41: 2–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Minton ME, Isaacson MJ, Varilek B, et al. A wilingness to go there: nurses and spiritual care. J Clin Nurs 2018; 27: 173–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sacks JL, Volker DL. CE Symptom management series. For their patients. A study of hospice nurses’ responses to patient suffering. J Hosp Palliat Nurs 2015; 17: 490–500. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Samarel N. Nursing in a hospital-based hospice unit. J Nurs Scholarsh 1989; 21: 132–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Samarel N. Caring for the living and dying: a study of role transistion. Int J Nurs Stud 1989; 26: 313–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Barnard A, Hollingum C, Hartfiel B. Going on a journey: understanding palliative care nursing. Int J Palliat Nurs 2006; 12: 6-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Byrne D, McMurray A. Caring for the dying: nurses’ experiences in hospice care. Aust J Adv Nurs 1997; 15: 4–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Clover A, Browne J, McErlain P, et al. Patient approaches to clinical conversations in the palliative care setting. J Adv Nurs 2004; 48: 333–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Johnstone M, Rawson H, Hutchinson AM, et al. Fostering trusting relationships with older immigrants hospitalised for end-of-life care. Nurs Ethics 2018; 25: 760–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]