Abstract

Background

Evidence suggests that prehabilitation interventions, which optimise physical and mental health prior to treatment, can improve outcomes for surgical cancer patients and save costs to the health system through faster recovery and fewer complications. However, robust, theory-based evaluations of these programmes are needed. Using a theory of change (ToC) approach can guide evaluation plans by describing how and why a programme is expected to work. Theories of Change have not been developed for cancer prehabilitation programmes in the literature to date. This paper aims to provide an overview of the methodological steps we used to retrospectively construct a ToC for Prehab2Rehab (P2R), a cancer prehabilitation programme being implemented by the Cardiff and Vale University Health Board.

Methods

We used an iterative, participatory approach to develop the ToC. Following a literature review and document analysis, we facilitated a workshop with fourteen stakeholders from across the programme using a ‘backwards mapping’ approach. After the workshop, stakeholders had three additional opportunities to refine and validate a final working version of the ToC.

Results

Our process resulted in the effective and timely development of a ToC. The ToC captures how P2R’s interventions or activities are expected to bring about short, medium and long-term outcomes that, collectively, should result in the overarching desired impacts of the programme, which were improved patient flow and reduced costs to the health system. The process of developing a ToC also enabled us to have a better understanding of the programme and build rapport with key stakeholders.

Conclusions

The ToC has guided the design of an evaluation that covers the complexity of P2R and will generate lessons for policy and clinical practice on supporting surgical cancer patients in Wales and beyond. We recommend that evaluators apply a ToC development process at the outset of evaluations to bring together stakeholders and enhance the utilisation of the findings. This paper details a pragmatic, efficient and replicable process that evaluators could adopt to develop a ToC. Theory-informed evaluations may provide better evidence to develop and refine cancer prehabilitation interventions and other complex public health interventions.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12913-024-11964-3.

Keywords: Theory of Change (ToC), Cancer Prehabilitation, Evaluation, Stakeholders, Complex Intervention

Background

Evaluating public health interventions is crucial to help understand the effectiveness and impact of the interventions, by generating evidence on what works for whom, why and how. Evaluation findings can be used to support decision making on future intervention funding, prioritisation, and if/how an intervention should change [25]. Evaluation relies on knowing the outcomes and goals of an intervention, in order to test them against results [6]. It also relies on clear objectives and measurable data. However, most public health interventions are complex, with multiple components that interact at various levels. This makes them more challenging to evaluate [12]. Research suggests that understanding the public health intervention’s underlying programme theory, including how it interacts with the context and the underlying uncertainties about how or why it works, may improve the evaluation of complex health interventions [37].

Programme theory can be visualised through a Theory of Change (ToC) approach. A theory of change describes how an intervention is expected to work by illustrating the sequence of outcomes and the anticipated pathways of change between programme activities, expected outcomes and the overall impact [5]. It is a conceptual model that can be developed through a combination of using evidence from existing research on the problem, theoretical models, the intervention in question, as well as consultation with stakeholders. This enables the model to explain how and why the programme is expected to achieve its desired goals/impact in the context in which it is implemented through the identified causal pathways [9, 37]. ToCs provide a framework for evaluation of complex health and social care interventions [37]. However, while much literature exists on how to create a programme theory for interventions, there is comparatively little reflection on developing a theory of change for cancer prehabilitation.

In Wales, there are over 1,000 new cancer cases each month [31]. Evidence suggests that cancer incidence could be reduced by modifiable lifestyle risk factors such as physical activity and nutrition [48]. Research suggests that cancer prehabilitation interventions can improve patient health prior to treatment, in-turn improving their treatment outcomes, decreasing treatment-related morbidity and decreasing costs to the health system [11, 26, 48]. Cancer prehabilitation refers to a proactive approach taken before cancer treatment begins to enhance a patient's physical and mental resilience [35, 36]. It generally involves a structured program tailored to the individual's needs, focusing on various modifiable lifestyle factors such as physical fitness, nutrition, mental health, and education about the upcoming treatment [48]. The goals of cancer prehabilitation include optimising the patient's health status, reducing treatment-related complications, enhancing post-treatment recovery, and improving overall quality of life [36]. By preparing patients physically and mentally for treatment, prehabilitation aims to improve outcomes and minimise the impact of treatment-related side effects.

Systematic reviews have found evidence to support the implementation of cancer prehabilitation services. These reviews suggest that prehabilitation patients experience fewer post-operative complications and reduced post-operative length of stay [15, 18, 19]. Another systematic review [21] found that prehabilitation also appears to have an additional positive effect on patient survival at one-year post-surgery. Systematic reviews have also shown that patients also reported a greater sense of control, and lower levels of anxiety and low mood [15, 43]. There is also emerging evidence from an outcome evaluation of prehabilitation programmes in the UK supporting the effectiveness of cancer prehabilitation programmes on cancer recovery outcomes for patients and cost savings for the NHS [30]. However, systematic reviews report that high heterogeneity across prehabilitation interventions, cancer types and sites, evaluation study design, and outcome measures make it difficult to assess the true impact of prehabilitation [18, 43, 44].

In 2019, a pilot site in Cardiff and Vale University Health Board (CVUHB), one of seven health boards within NHS Wales, developed the Prehab2Rehab (P2R) programme. P2R is a system-wide, personalised, multi-modal, and needs-based health and wellbeing prehabilitation and recovery programme, designed to improve physiological and psychological resilience prior to surgical treatment. P2R sits within the national cancer pathway in Wales, although not all patients on the cancer pathway access P2R. Currently, P2R sites are only based in the Cardiff and Vale University Health Board area and the programme is limited to patients with confirmed Upper Gastrointestinal, Lung, Hepatobiliary Pancreatic, Colorectal, Complex Urology, and Ovarian cancers. The aim for P2R is to use the point of referral from primary to secondary care with suspected cancer as a ‘teachable moment’ to address cancer risk factors through lifestyle modification for all patients whether they receive a confirmed cancer diagnosis or the all-clear, and to optimise patient outcomes from cancer surgery and treatment [7]. Overall, the programme has potential to improve patient recovery and reduce the use of health resources.

In 2022, Welsh Government made commitments to cancer prehabilitation programmes by introducing integrated prehabilitation models as standard elements of all pathways, with the overarching aim to develop a standard prehabilitation approach to improve outcomes and reduce NHS waiting lists [47]. Given that the Welsh Government intends to scale up the P2R programme to include other types of cancer and the other NHS Wales health board regions, it is imperative that an independent evaluation of the programme is conducted. This will provide a descriptive and analytical account of how the programme has been implemented as well as how and why it is or is not making a difference to patients or the NHS.

Given the complexity of the P2R programme, a ToC approach was taken to articulate the programme theory at the outset of the evaluation. Having a ToC for such a service would explicitly detail the P2R programme activities, the sequence of outcomes and propose a theory to explain how the various activities contribute to the final intended impacts on patients and the NHS. It would also enable stakeholders to identify the conditions that need to be maintained (assumptions) to enable the programme to be successful, and the risks to the programme if these assumptions are not met or maintained. The ToC was also needed to guide the final development of the evaluation matrix which would detail the evaluation questions, identify the appropriate qualitative and quantitative indicators for the outcomes, the data sources and the evaluation design that would be most suited to testing the ToC. For complex interventions such as cancer prehabilitation, developing a ToC to depict and test the underlying theory is particularly important, allowing evaluators to better assess the effectiveness of the programme.

There is limited evidence of how a theory of change approach can guide the evaluation of cancer prehabilitation services. In this paper, we provide an overview of the methodological steps we used to construct and refine a ToC for Prehab2Rehab. We will also present our reflections on the process, including successes, challenges faced and implications for the evaluation of Prehab2Rehab. This will present a replicable process for other evaluators seeking to develop a ToC for a complex intervention, as well as build on our reflections to help guide others in this process.

Methods

In this section, we detail the method taken to develop the ToC for P2R, including how we adapted existing guidance to enable the development of a ToC in this context. A structured, iterative process was employed to identify the conceptual programme theory for P2R. We used a multi-step Theory of Change (ToC) development approach designed to facilitate stakeholder contributions to establish consensus on the programme theory. The approach was developed by adapting existing guidance on developing a ToC [12, 13, 39].

Identification of stakeholders for the theory of change workshop

Due to the complex, multimodal nature of the programme, over fifty stakeholders across multiple disciplines contribute to the delivery of P2R, including clinicians, therapy assistant practitioners, physiotherapists, surgeons, pharmacists, dietitians, anaesthetists, cardiologists, occupational therapists and administrators. These stakeholders represent the various strands of the programme that patients can go through in primary and secondary care along the cancer treatment pathway. This includes exercise, nutrition, and wellbeing components, clinical optimisation, and surgical treatment. Stakeholders from across these disciplines were identified by the P2R leadership team and invited to the ToC workshop.

Developing the ToC

As has been recommended in previous ToC protocols, we used an iterative approach to develop and refine the ToC. We took a three-stage approach which were scoping, workshop, and validation or quality assurance. This three-stage approach was used to ensure the evaluators developed an understanding of prehabilitation as an intervention and how Prehab2Rehab is delivered in practice prior to the development and refinement of the ToC. The stages are described below.

Stage 1—Scoping

To inform the evaluation, a rapid, unstructured literature review of the published evidence and systematic reviews of cancer prehabilitation was undertaken by JW and AC. This approach enabled the evaluators to efficiently gain an understanding of the existing evidence on cancer prehabilitation. There is significant evidence underpinning prehabilitation, with various systematic reviews [14, 20, 22, 44, 45] and primary research [4, 42, 46]. The main findings of our literature review were:

Prehabilitation, through a combination of increased physical activity, improved diet and psychological/wellbeing therapy, can significantly improve a patient’s readiness for treatment [22, 34, 49].

Outcomes of prehabilitation for patients include improved fitness, functional capacity, reduced/prevented malnutrition, improved resilience against anxiety, depression and cancer-related cognitive impairment [22, 34, 49].

Prehabilitation can also reduce a patient’s length of stay in hospital and reduce the risk of the patient experiencing further complications [20, 24].

Structured health and wellbeing education empowers a significant proportion of patients to act on their health behaviours/lifestyle prior to treatment [44, 46].

Typical barriers to prehabilitation include family needs, work commitments, anxiety, illness, comorbidities, lack of social support, travel requirements and financial capacity [29, 45].

The success of prehabilitation programmes is typically dependent on coordination of a multidisciplinary team featuring surgeons, anaesthetists, nurses, physiotherapists, exercise specialists, dieticians, finance experts and information technology experts [4, 14, 42].

JW and AC also attended P2R team meetings throughout 2023 and undertook analysis of key P2R programme documents supplied by the programme team. Based on the scoping, an initial ToC diagram was drafted by JW and AC with support from the other evaluators to provide a framework through which stakeholders could explore how they thought P2R will make a difference to patients and the process by which that difference takes place.

Having a prepopulated ToC is an abbreviated approach to the ToC development process which can ordinarily take a long time over multiple workshops to conduct with stakeholders. This abbreviated approach was taken to enable us to conduct a high-quality ToC development process in a condensed timeframe. Using the evidence base to construct an initial draft ToC allowed us to maximise our time with stakeholders and have focused discussions. Equally, this made the process accessible to prehabilitation clinicians with competing time pressures, ensuring a wide range of stakeholder perspectives were engaged. The abbreviated approach aligns with the ToC being a live diagram that is continuously adapted based on learning, reflection, and conversations with stakeholders.

Stage 2—ToC Workshop

On the 30th of November 2023, a workshop was held to discuss the initial ToC and enable stakeholders to reflect on the proposed change pathways based on their experience of delivering P2R. The overall purpose of this workshop was to engage staff and key stakeholders in participatory discussions about the P2R programme. It was facilitated by JW, AC, CG, and EM. The workshop lasted two hours with 14 attendees who represented all different components of P2R.

The workshop took place virtually, utilising Microsoft (MS) Teams and Miro [23], an online collaboration tool, to facilitate discussions. To mitigate against digital exclusion, stakeholders received a “Guide to Miro” document prior to the workshop, and any who were unable to access/use Miro were able to input to the discussion using the MS Teams Chat function. Points made orally or in the MS Teams chat were added to the Miro by the facilitators. Stakeholders were required to collaboratively develop the ToC and refine the initial ideas that had been gathered from literature about how P2R works.

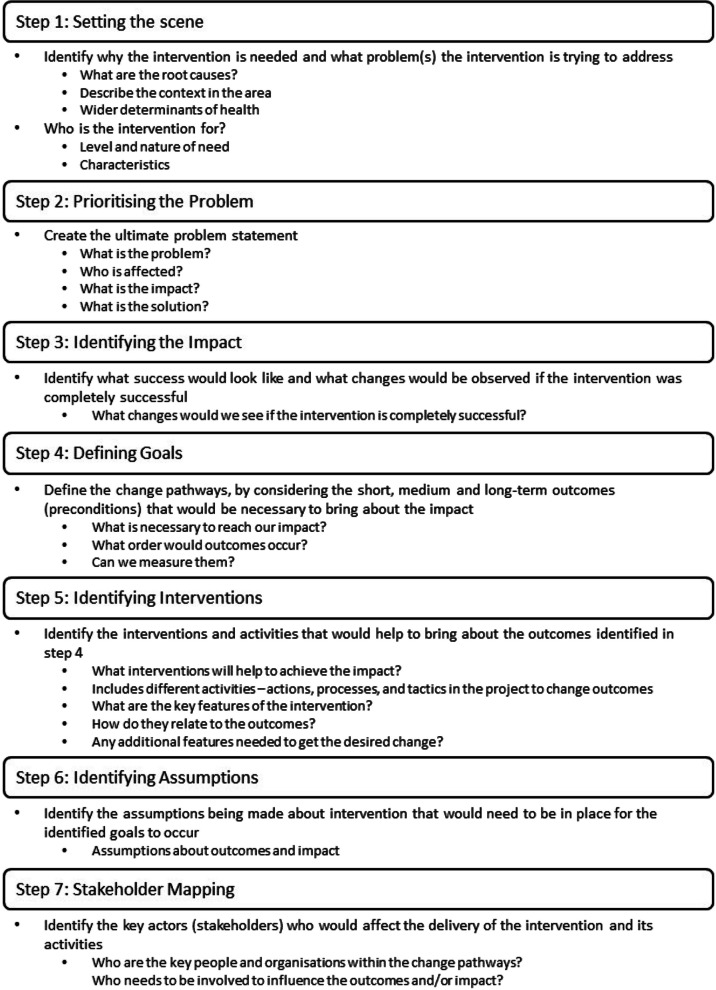

The workshop took a ‘backwards mapping’ approach, meaning the long-term goal was identified before working backwards through the sequences of changes that would need to occur to reach this goal [8]. Stakeholders were taken through seven steps adapted from previous guidance [12, 13, 39]. These steps were designed to aid critical thinking to map how P2R achieves the intended change through a causal sequence of outcomes, clearly articulated together with assumptions and with outcomes that can be tested empirically [12, 32]. The steps were: 1 Setting the scene,2 Prioritising the problem; 3 Identifying the impact; 4 Defining goals; 5 Identifying activities; 6 Identifying assumptions; and 7 Stakeholder mapping. Each of these steps, along with the corresponding questions used to facilitate discussions, are detailed in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

ToC Development Steps for Prehab2Rehab adapted from previous guidance [12, 13, 39]

Using the initial ToC diagram, each of the workshop steps were pre-populated with the corresponding ToC aspect on the Miro board, so stakeholders could view, comment, and/or make changes to the initial ToC diagram. Each author led 2–3 of the steps, while fellow co-facilitators took notes and managed any technical issues. Steps 1 and 2 facilitated a discussion around the wider issues surrounding the prevalence of cancer in Wales, the need for prehabilitation interventions and specifically the issues that P2R was striving to address. Step 3 enabled us to collate this discussion to articulate the overarching desired impact of P2R. Step 4 allowed stakeholders to articulate the series of changes that P2R would need to cause to bring about this impact, while Step 5 aligned these changes with various activities within P2R. Step 6 facilitated a discussion on broader influences that may affect P2R’s delivery and outcomes and Step 7 articulated the stakeholders who have roles to play throughout the change pathways.

Not all stakeholders were able to attend the workshop, therefore following the workshop, all stakeholders were contacted via email to ask for their input either via email or directly onto the Miro. Within the email, stakeholders were advised on the iterative process and that there would be additional opportunities to feed-in to the ToC. Stakeholders were given one-week to provide feedback. Six additional stakeholders provided feedback via email, meaning a total 20 stakeholders were involved in the ToC development process.

An additional step of the ToC-development process was conducted by the evaluators and Prehab2Rehab leaders outside of the workshop, to ensure that the workshop could be delivered in a timely manner. This step was the identification of indicators, which describe the data that could be used to capture change against each of the short, medium and long-term outcomes. As these outcomes had been confirmed with the input of stakeholders at the workshop, evaluators were able to define the indicators with input from Prehab2Rehab leads who had knowledge of potential data sources to ensure indicators could be measured.

Stage 3—Validation and quality assurance of the ToC

Following the workshop, the ToC underwent three additional rounds of reflection and feedback before consensus was reached on a ToC that was feasible, testable and plausible. For each round, the PHW evaluation team compiled the comments and refined the ToC in a new iteration of the ToC diagram, based on the feedback that was provided. The new iteration was then produced and circulated firstly among the evaluation team for comments. Once consensus was achieved among the evaluation team, the ToC diagram was reshared with the Prehab2Reahab team. For each round, the Prehab2Reahab team was given two weeks to review and provide additional comments.

After agreement was achieved between the evaluation team and Prehab2Rehab team, the ToC diagram was shared to the wider stakeholders for a final round of feedback. Wider stakeholders were given one week to provide any comments on the ToC diagram and were advised the ToC would be revisited throughout the evaluation. After receiving the final comments, a final ToC diagram was produced.

Results

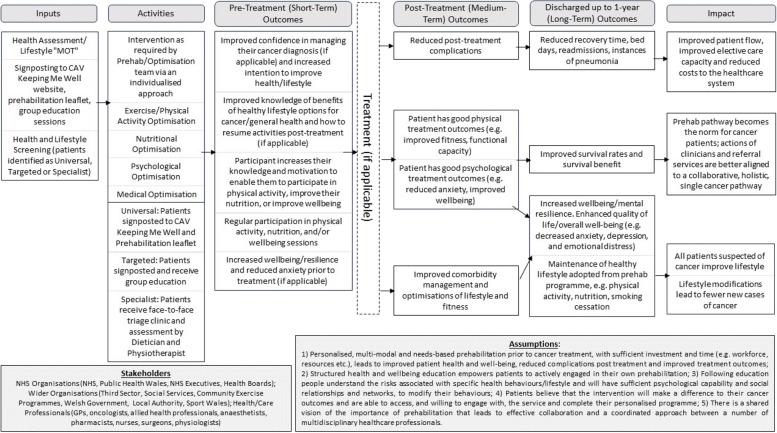

The resulting ToC is given in Fig. 2. The diagram provides the various inputs, outputs and expected outcomes of the programme, with arrows to depict the theoretical change pathways between the activities and outcomes that Prehab2Rehab participants are expected to experience.

Fig. 2.

Theory of Change diagram for Prehab2Rehab programme

In-keeping with the backwards mapping approach, Steps 1, 2 and 3 of the process detailed in the previous section enabled the identification of the long-term desired impacts of P2R, which were improved patient flow and capacity, reduced costs to the NHS, the alignment of services and lifestyle modifications in people with suspected cancer. These are depicted in the right-hand column of the ToC.

Step 4 articulated the short, medium and long-term outcomes required to bring about this overarching impact. These outcomes are provided in the Pre-Treatment, Post-Treatment and Discharged up to 1 Year columns of the ToC. Pre-Treatment depicts the immediate, short-term outcomes that participants experience prior to treatment. Post-Treatment depicts the medium-term outcomes that participants will experience following their treatment (if applicable). Discharged up to 1 Year depicts the long-term outcomes that participants should experience up to one year after their treatment ends.

Step 5 articulated the key inputs and activities that exist within P2R, such as health assessments, screening, signposting and individualised interventions, which are expected to bring about those desired outcomes. These inputs and activities are provided in the left-hand columns of the ToC. Step 6 identified five assumptions that stakeholders felt may affect the delivery or impact of P2R, while Step 7 articulated the stakeholders with roles to play in the delivery of P2R. The assumptions and stakeholders are detailed at the bottom of the ToC. The indicators, which were developed by the evaluators and Prehab2Rehab leaders outside of the workshop, are available in Additional File 1.

Due to the complexity of the programme, the process included the development of a more detailed ToC, in which the simplified model is nested, that provides additional operational detail that is typically more akin to a logic model (Fisher et al., 2021), such as the overarching cancer pathway, as well as the various entry points and differing interventions that patients receive, leading to the anticipated outcomes. This is available in Additional File 2. A ToC narrative was also developed, which discusses the evidence underpinning each of the assumptions provided in the diagram. This narrative is available in Additional File 3.

Discussion

The iterative, participatory process used to develop the ToC is replicable not only for cancer prehabilitation programmes, but also for a wide range of other complex programmes, policies, and interventions to inform the design of evaluations. While we adopted a similar approach to those recommended by Connell and Kubisch [10] and De Silva et al. [12], there are important reflections on the successes and challenges of applying this process in practice. This section explores those reflections, as well as the benefits of developing a ToC for evaluation.

Successes

Developing a robust ToC can be a significantly time-consuming process [12, 41]. We found that drafting an initial ToC diagram based on our early understanding of the programme, and using this as a starting point at the ToC development workshop was highly effective in making this process more efficient. Rather than asking the stakeholders in the workshop to populate a 'blank sheet' with the relevant characteristics of a theory of change, we presented them with exemplar activities, interventions, and outcomes based on the evidence collected that triggered conversations where stakeholders could highlight what was important and relevant to them. Stakeholders reviewed the initial ToC for its accuracy and confirmed, clarified, or debated the points made. This allowed us to gather the relevant input from stakeholders in two hours, condensing a process that could take up to two days [41].

Due to the diverse nature of stakeholders and the common practice of remote working, the decision was made to host the ToC workshop online via Microsoft Teams. While there are innate issues with this such as the potential for technological difficulties [33], this was also thought to be a successful approach. Using video-conferencing software can enhance the accessibility of stakeholder engagement activities by removing the time and costs associated with travel to an in-person workshop [17]. The team felt that, given the diverse range of stakeholders involved in the programme, removing these burdens resulted in better attendance and engagement at the workshop than would have been achieved in-person. This is an important reflection, given the need to maximise stakeholder input to a ToC, especially when the programme in question is multi-faceted and complex as it was with Prehab2Rehab [13, [38]. Equally, the workshop was able to facilitate discussions between diverse stakeholders in the programme. While the ToC diagram itself is the primary output, the connections, interactions, and engagement between diverse stakeholders – that may not have occurred without the workshop – are to the benefit of the programme. This is comparable to other areas of public health evaluation, where participatory activities act as a “hook” to bring together stakeholders, and the resultant discussions and interactions are equally as impactful as the workshop output itself [1].

Another aspect of hosting the workshop online was the use of the Miro software to build the ToC. This was thought to be an appropriate tool to bring together the perspectives of the stakeholders, as all stakeholders that attended the workshop were able to work on the same document, meaning points could be discussed, confirmed, or disputed with the whole group. In-person, this may be difficult to achieve if stakeholders needed to be split into groups to keep discussions and inputs practically manageable. Equally, because the Miro board was left open after the workshop, individuals who were unable to attend could provide their input in their own time. To this end, we feel as though the process employed for the P2R ToC was heavily participatory and maximised the input of the expert stakeholders who attended. Using Teams to facilitate the discussion and Miro to provide a base ToC that was edited by stakeholders was felt to be a pragmatic and efficient approach to maximising participation and collaboratively developing a robust ToC.

Challenges

There were, of course, challenges associated with developing this ToC. Given the complexity of Prehab2Rehab and the large number and diverse range of stakeholders, it was unrealistic to expect that every part of the programme would be represented in the ToC development workshop. This means that the initial and subsequent drafts of the ToC may not fully reflect the views of the stakeholders who did not engage in the process. To overcome this, we shared the draft ToC with wider stakeholders who missed the workshop via a combination of emails and follow-up meetings to collect their input. This provided another challenge, in that refining the ToC was time-consuming and it was difficult to capture the input of every stakeholder. Equally, owing to the complexity of the programme, there were sometimes conflicting views on the activities and outcomes which required the evaluators to have additional meetings with Prehab2Rehab leaders to ensure the accuracy of the diagram. This indicates how a ToC development process can impact the timelines for evaluations, particularly of complex programmes. While the timeline for this evaluation was relatively flexible, the refining process we employed may not be appropriate for evaluations with strict, challenging deadlines.

Another challenge we experienced was occasional confusion around whether the ToC should be a realistic depiction of the programme in its current state, or a less-detailed theoretical depiction of how the programme is designed to bring about the desired change. In the case of Prehab2Rehab, where there are some disparities at present between the aspirations and the actual delivery, there were often conflicting perspectives presented on the ToC. As stakeholders were unfamiliar with the concept of ToC, evaluators were required to ensure discussions remained focused on how Prehab2Rehab should operate in theory, rather than the current practical reality. This presents an important reflection for future evaluations, where the purpose of a ToC and what is expected must be clearly articulated to all stakeholders who are inputting to the diagram. On reflection, more time could have been allocated to explaining this and it may have saved time when it came to refining the diagram.

Uses for evaluation

We used this ToC development process as the starting point for our evaluation of Prehab2Rehab, and there are a number of ways in which developing a Theory of Change has strengthened our ability to evaluate the programme. Firstly, the participatory process taken facilitated stronger connections between the evaluation team and the leaders and deliverers of P2R. The ToC development process and subsequent other meetings and connection points facilitated and built the relationship and communication channels between the evaluation team and P2R stakeholders, and helped to build rapport. Many of the stakeholders involved in developing the ToC were likely to be part of the evaluation, so this enabled them to understand the purpose of the evaluation and ask any questions less formally. This indicates that a ToC development process may be an effective and useful way for evaluators to build rapport with stakeholders at the outset of an evaluation.

As well as the interactions with Prehab2Rehab stakeholders, the ToC diagram itself facilitated a more thorough understanding of the programme among the evaluation team. Engaging a wide range of stakeholders enabled the evaluation team to understand how the different aspects of Prehab2Rehab were working in practice, how they linked to each other and the overarching patient pathway. Once the ToC had been finalised, the evaluation team felt they had a significantly deeper understanding of Prehab2Rehab, that would not have been possible through independently reviewing programme documents. In turn, this facilitated the development of robust indicators to be used in the evaluation. This is in-keeping with other perspectives on Theories of Change, in that developing a ToC can help to identify the data that can best answer evaluation questions [3]. By clarifying the P2R programme and explicitly identifying its short, medium, and long-term outcomes, the evaluation team were able to align indicators with these outcomes. This helped us develop an evaluation matrix which supported us to identify the data needed to evidence the impact of Prehab2Rehab. By mapping the evaluation questions against the routinely collected data that could answer them, we were able to design methods to collect primary data that was also necessary to answer the questions. Evaluators should therefore consider a ToC development process at the outset of an evaluation, particularly when they may have limited understanding of the programme in question and data sources available to them.

Perhaps the most significant benefit of developing a ToC is the potential to “test” the programme’s model through the evaluation. The outcomes and indicators are one part of this, but a ToC also captures the theoretical delivery model and the assumptions that the programme’s outcomes may be dependent on. This enables further refinement of the evaluation approach, identifying the questions that need to be asked to understand if the theoretical model is being delivered in practice and if the assumptions being made are holding true in the real world. Furthermore, developing a ToC indicated how Prehab2Rehab was intended to work in its given context. This enabled the evaluation to assess the applicability and generalisability of the programme to other contexts [40]. This is the additional value of using a ToC approach rather than a logic model, as a ToC articulates concepts beyond the operational details of a programme and can capture the complexity of a programme within its wider context. In the example of Prehab2Rehab, the ToC captures the theory that underpins the programme alongside the routine delivery of the broader cancer pathway. By illustrating conceptual change pathways, the ToC represents the theory that underpins Prehab2Rehab, whereas a logic model would explain step-by-step how the programme should work in practice. This indicates that evaluators could use a ToC development process to support a theory-based evaluation, which can consider the effectiveness and efficiency of a programme. The findings of this type of evaluation are likely to be important to stakeholders and commissioners.

The ToC development approach is not without its limitations. Given that a ToC depicts the theoretical mechanisms for how and why a programme may bring about its outcomes, it cannot be assumed that all the mechanisms of change are delivered in practice. This is particularly true for complex programmes like P2R, where wider influences are likely to impact the real-world delivery of the programme. A ToC may therefore exclude operational details of a programme that are important to acknowledge in an evaluation [16]. However, as our process enabled the development of a classic, conceptual ToC (Fig. 2) nested within a more detailed ToC with additional operational detail (Additional File 2), we have mitigated against this limitation.

Because the ToC identifies the desired outcomes of the programme, it does not capture unintended outcomes. This is an important reflection for evaluators, as evaluations should strive to uncover both the intended and unintended impacts of interventions [28]. While the ToC provides an appropriate framework to test if and how intended outcomes are brought about, evaluators should consider whether the evaluation methods employed are capable of capturing the wider, unintended outcomes of a programme.

Similarly, Theories of Change have been criticised for not capturing the wider, whole-system view, or considering overall whether or not the programme is the right thing to do [2, 41]. However, we have found them to be successful and provide valuable insight into the evaluation design process, including where Prehab2Rehab sits within the broader cancer pathway. When used in combination with other methodologies, a ToC can provide an effective framework for evaluation of complex interventions. While Theories of Change provide an appropriate framework to test interventions, evaluators should consider additional evaluation methodologies that review the impacts of interventions on the whole-system to provide evidence that expands beyond overly simplistic, individual-level actions to influence public health [27].

Conclusions

Despite its challenges, the process of developing a ToC was thought to be highly beneficial to the evaluation of Prehab2Rehab. The backwards mapping approach resulted in a ToC diagram that informed the evaluation approach, methods, and questions. Delivering a ToC development workshop using software such as MS Teams and Miro, as well as developing a draft ToC prior to the workshop, were seen to reduce the time taken to establish a ToC for the programme. The process also enabled evaluators to build rapport with stakeholders across the P2R programme. We recommend that evaluators implement this approach to develop a deeper understanding of the intervention being evaluated, to facilitate relationships with programme stakeholders, and to maximise the impact of their evaluations by identifying the most pertinent questions to be answered. Further reflection and publication on this approach would test its applicability to other areas of public health and refine the method of developing a ToC.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Prehab2Rehab Table of Indicators. This table describes the indicators that could be used to capture change against each of the outcomes detailed in the Theory of Change. The indicators are measures that could identify whether or not each outcome has been achieved

Additional file 2: Full Theory of Change for Prehab2Rehab. This full Theory of Change provides additional operational detail depicting the complexity of the Prehab2Rehab programme. This includes the inputs, outcomes and impacts detailed in the diagram included in the article (Figure 2), but with extra detail such as the overarching cancer pathway, entry points and interventions that contribute to Prehab2Rehab

Additional file 3: Prehab2Rehab Theory of Change Narrative. This narrative that accompanies the Theory of Change diagram reviews the evidence behind each of the five assumptions identified by stakeholders. Assumptions are defined as something outside the scope of the programme that could have an impact on the short, medium and long-term outcomes

Acknowledgements

We wish to express our thanks to all members of staff at the Cardiff and Vale University Health Board who contributed to the development of the Theory of Change for Prehab2Rehab: Carole Jones, Claire Jarrom, Dean Whittle, Elaine Davies, Eleanor Davis, Emily Johns, Erica Thornton, Jemima Bevan, Joshua Tipple, Kerry Ashmore, Marian Jones, Megan Woolmer, Richard Baxter, Tessa Bailey and Zoe Hicks.

Abbreviations

- ToC

Theory of Change

- P2R

Prehab2Rehab

- PHW

Public Health Wales

Authors’ contributions

JW and AC delivered the Theory of Change workshop and were the major contributors in refining the diagram and writing the manuscript. EM adapted the steps for developing the ToC from various sources and provided the team with a template on how to deliver the ToC workshop. CG and EM supported the delivery of the workshop and contributed significantly to the development of the diagram. AD provided project oversight. RB and RM recruited stakeholders to contribute to the Theory of Change and contributed significantly to the refinement of the diagram. All authors provided comments and feedback to the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

JW (Senior Research and Evaluation Officer), AC (Research and Evaluation Fellow), CG (Public Health Evaluation Lead), EM (Deputy Head of Evaluation) and AD (Head of Research and Evaluation) are staff in Public Health Wales’ Research and Evaluation Division. RB (Clinical Lead, Prehabilitation) and RM (Senior Programme Manager) are senior leaders in Prehab2Rehab at the Cardiff and Vale University Health Board.

Funding

No funding was received for this work.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This project, including the Theory of Change workshop, was deemed to be a service evaluation to improve healthcare, undertaken as part of the establishment order for Public Health Wales NHS Trust under the National Health Service (Wales) Act 2006. As per Health Research Authority guidance, ethical approval was not required. This decision was ratified by the Public Health Wales Research and Development Office. An internal Data Protection Impact Assessment was completed to ensure that the evaluation activities adhered to Information Governance regulations. Only consensus data was collected (with no individual or personal data) and workshop participants provided verbal informed consent for the workshop outputs to be included in research outputs.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Allender S, et al. A community based systems diagram of obesity causes. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(7):e0129683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barbrook-Johnson P, Penn AS. Theory of Change diagrams. In: Systems Mapping: how to build and use casual models of systems. 2022; 33–46.

- 3.Better Evaluation. Describe the theory of change. https://www.betterevaluation.org/frameworks-guides/managers-guideevaluation/scope/describe-theory-change . Accessed 24 May 2023.

- 4.Bingham SL, Small S, Semple CJ. A qualitative evaluation of a multi-modal cancer prehabilitation programme for colorectal, head and neck and lung cancers patients. PLoS ONE. 2023;18(10):e0277589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breuer E, Lee L, De Silva M, Lund C. Using theory of change to design and evaluate public health interventions: a systematic review. Implementation Science. 2015;11:63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brownson RC, Baker EA, Deshpande AD, Gillespie KN. Evidence-based public health. New York: Oxford University Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cardiff South West Primary Care Cluster. Prehab2Rehab: Health Optimisation Service. https://cardiffsw.co.uk/prehab2rehab-health-optimisation-service/#:~:text=The%20Prehab2Rehab%20service%20sets%20out,for%20those%20on%20regular%20medication. Accessed 28 May 2024.

- 8.Center for Theory of Change. What is Theory of Change? Glossary. https://www.theoryofchange.org/what-is-theory-of-change/how-does-theory-of-change-work/glossary/. Accessed 20 May 2024.

- 9.Clark H, Anderson A. Theories of Change and Logic Models: Telling Them Apart. PowerPoint presented at: American Evaluation Association Conference. Atlanta; 2004.

- 10.Connell JP, Kubisch AC. Applying a Theory of Change Approach to the Evaluation of Comprehensive Community Initiatives. In: Fullbright-Anderson K, Kubisch AC, Connell JP, editors. Progress, Prospects, and Problems. New Approaches to Evaluating Community Initiatives, Volume 2: Theory, Measurement, and Analysis. Washington DC: The Aspen Institue; 1998. p. 1–16.

- 11.Cox T, O’Connell M, Leeuwenkamp O, Palimaka S, Reed N. Real-world comparison of healthcare resource utilization and costs of in patients with progressive neuroendocrine tumors in England: a matched cohort analysis using data from the hospital episode statistics dataset. Curr Med Res Opin. 2022;38(8):1305–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Silva MJ, Breuer E, Lee L, Asher L, Chowdhary N, Lund C, Patel V. Theory of change: a theory-driven approach to enhance the Medical Research Council’s framework for complex interventions. Trials. 2014;15(1):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Early Intervention Foundation. How to develop and confirm your theory of change. https://evaluationhub.eif.org.uk/theory-of-change/. Accessed 18 April 2023.

- 14.Engel D. Setting Up a Prehabilitation Unit: Successes and Challenges. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2022;38(5):151334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Faithfull S, Turner L, Poole K, Joy M, Manders R, Weprin J, Winters-Stone K, Saxton J. Prehabilitation for adults diagnosed with cancer: A systematic review of long-term physical function, nutrition and patient-reported outcomes. Eur J Cancer Care. 2019;28(4):e13023. 10.1111/ECC.13023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fisher K, Macleod J, Kennedy S, Schnapp B, Chan TM. Logic model of program evaluation. Educ Theory Made Pract. 2021;5(7):46–52. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gray LM, et al. Expanding Qualitative Research Interviewing Strategies: Zoom Video Communications. The Qualitative Report. 2020;25:1292–301. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jensen BT, Baldini G. Future Perspectives on Prehabilitation Interventions in Cancer Surgery. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2022;38(5):151337. 10.1016/J.SONCN.2022.151337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jensen BT, Thomsen T, Mohamed N, Paterson C, Goltz H, Retinger NL, Witt VR, Lauridsen SV. Efficacy of pre and rehabilitation in radical cystectomy on health related quality of life and physical function: A systematic review. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. 2022;9(7):100046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lambert JE, Hayes LD, Keegan TJ, Subar DA, Gaffney CJ. The impact of prehabilitation on patient outcomes in hepatobiliary, colorectal, and upper gastrointestinal cancer surgery: a PRISMA-accordant meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2021;274(1):70–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McIsaac DI, Gill M, Boland L, Hutton B, Branje K, Shaw J, Grudzinski AL, Barone N, Gillis C, Akhtar S, Atkins M, Aucoin S, Auer R, Basualdo-Hammond C, Beaule P, Brindle M, Bittner H, Bryson G, Carli F, Wijeysundera D, et al. Prehabilitation in adult patients undergoing surgery: an umbrealla review of systematic reviews. Br J Anaesth. 2022;128(2):244–57. 10.1016/J.BJA.2021.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Michael CM, Lehrer EJ, Schmitz KH, Zaorsky NG. Prehabilitation exercise therapy for cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Med. 2021;10(13):4195–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miro. https://miro.com/login. Accessed 11 June 2024.

- 24.Molenaar CJ, Minnella EM, Coca-Martinez M, Ten Cate DW, Regis M, Awasthi R, MartínezPalli G, López-Baamonde M, Sebio-Garcia R, Feo CV, van Rooijen SJ. Effect of multimodal prehabilitation on reducing postoperative complications and enhancing functional capacity following colorectal cancer surgery: the PREHAB randomized clinical trial. JAMA surgery. 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Moore G, Audrey S, Barker M, Bond L, Bonell C, Cooper C, Hardeman W, Moore L, O’Cathain A, Tinati T, Wight D. Process evaluation in complex public health intervention studies: the need for guidance. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2014;68(2):101–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mouch CA, Kenney BC, Lorch S, Montgomery JR, Gonzalez-Walker M, Bishop K, et al. Statewide Prehabilitation Program and Episode Payment in Medicare Beneficiaries. J Am Coll Surg. 2020;230(3):306–313.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.NIHR School for Public Health Research. Guidance on systems approaches to local public health evaluation – part 2: what to consider when planning a systems evaluation. https://sphr.nihr.ac.uk/wpcontent/uploads/2018/08/NIHR-SPHR-SYSTEM-GUIDANCE-PART-2-v2- FINALSBnavy.pdf. Accessed 14th February 2023.

- 28.Parrott L, Lange H. An introduction to complexity science. In: Messier C, Puettmann KJ, Coates KD, editors. Managing Forests as Complex Adaptive Systems. Oxon: Routledge; 2013. p. 31–46. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Powell R, Davies A, Rowlinson-Groves K, French DP, Moore J, Merchant Z. Acceptability of prehabilitation for cancer surgery: a multi-perspective qualitative investigation of patient and ‘clinician’experiences. BMC Cancer. 2023;23(1):744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prehab4Cancer Greater Manchester. Independent evaluation shows extremely positive results. https://www.prehab4cancer.co.uk/2022/01/independent-evaluation-shows-extremely-positive-results/. Accessed 11 June 2024.

- 31.Public Health Wales, Welsh Cancer Intelligence and Surveillance Unity (WCISU). Pathology samples indicating new cases of cancer in Wales. https://phw.nhs.wales/services-and-teams/welsh-cancer-intelligence-and-surveillance-unit-wcisu/cancer-reporting-tool-official-statistics/pathology-samples-indicating-new-cases-of-cancer-in-wales/. Accessed 28 May 2024.

- 32.Reinholz DL, Andrews TC. Change theory and theory of change: what’s the difference anyway? International Journal of STEM Education. 2020;7(1):1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rowe M, et al. Video Conferencing Technology in Research on Schizophrenia: A Qualitative Study of Site Research Staff. Psychiatry. 2014;77:98–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scriney A, Russell A, Loughney L, Gallagher P, Boran L. The impact of prehabilitation interventions on affective and functional outcomes for young to midlife adult cancer patients: A systematic review. Psychooncology. 2022;31(12):2050–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Silver JK. Cancer Prehabilitation and its Role in Improving Health Outcomes and Reducing Health Care Costs. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2015;31(1):13–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Silver JK, Baima J. Cancer Prehabilitation: An opportunity to decrease treatment-related morbidity, increase cancer treatment options, and improve physical and psychological health outcomes. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;92(8):715–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Skivington K, Matthews L, Simpson SA, Craig P, Baird J, Blazeby JM, Boyd KA, Craig N, French DP, McIntosh E, Petticrew M. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: Update of Medial Research Council Guidance. BMJ. 2021;374:n2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tanner-Smith EE, Grant S. Meta-analysis of complex interventions. Annu Rev Public Health. 2018;39:135–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taplin DH, Clark H. Theory of Change Basics: A Primer on Theory of Change. https://www.theoryofchange.org/wp-content/uploads/toco_library/pdf/ToCBasics.pdf. 2012. Accessed 28 May 2024.

- 40.Taplin DH, Clark H, Collins E, Colby DC. Theory of change. New York: ActKnowledge; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Taylor-Powell E, Henert E. Developing a logic model: Teaching and training guide. Benefits. 2008;3(22):1–118. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tew GA, Bedford R, Carr E, Durrand JW, Gray J, Hackett R, Lloyd S, Peacock S, Taylor S, Yates D, Danjoux G. Community-based prehabilitation before elective major surgery: the PREPWELL quality improvement project. BMJ open quality. 2020;9(1):e000898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Toohey K, Hunter M, McKinnon K, Casey T, Turner M, Taylor S, Paterson C. A systematic review of multimodal prehabilitation in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2023;197(1):1–37. 10.1007/S10549-022-06759-1/TABLES/4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Treanor C, Kyaw T, Donnelly M. An international review and meta-analysis of prehabilitation compared to usual care for cancer patients. J Cancer Surviv. 2018;12(1):64–73. 10.1007/S11764-017-0645-9/FIGURES/4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van der Velde M, van der Leeden M, Geleijn E, Veenhof C, Valkenet K. What moves patients to participate in prehabilitation before major surgery? A mixed methods systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2023;20(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Waterland JL, Chahal R, Ismail H, Sinton C, Riedel B, Francis JJ, Denehy L. Implementing a telehealth prehabilitation education session for patients preparing for major cancer surgery. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Welsh Government. Programme for transforming and modernising planned care and reducing waiting lists in Wales. https://gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2022-04/our-programme-for-transforming--and-modernising-planned-care-and-reducing-waiting-lists-in-wales.pdf. Accessed 17 April 2024.

- 48.West MA, Jack S, Grocott MP. Prehabilitation before surgery: Is it for all patients? Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2021;35(4):507–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.West MA, Wischmeyer PE, Grocott MP. Prehabilitation and nutritional support to improve perioperative outcomes. Curr Anesthesiol Rep. 2017;7:340–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Prehab2Rehab Table of Indicators. This table describes the indicators that could be used to capture change against each of the outcomes detailed in the Theory of Change. The indicators are measures that could identify whether or not each outcome has been achieved

Additional file 2: Full Theory of Change for Prehab2Rehab. This full Theory of Change provides additional operational detail depicting the complexity of the Prehab2Rehab programme. This includes the inputs, outcomes and impacts detailed in the diagram included in the article (Figure 2), but with extra detail such as the overarching cancer pathway, entry points and interventions that contribute to Prehab2Rehab

Additional file 3: Prehab2Rehab Theory of Change Narrative. This narrative that accompanies the Theory of Change diagram reviews the evidence behind each of the five assumptions identified by stakeholders. Assumptions are defined as something outside the scope of the programme that could have an impact on the short, medium and long-term outcomes

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.