Abstract

Cleidocranial Dysplasia (CCD) is a rare genetic disorder characterized by skeletal abnormalities and dental anomalies, primarily caused by variants in the RUNX2 gene. Understanding the spectrum of RUNX2 variants and their effects on CCD phenotypes is crucial for accurate diagnosis and management strategies. This systematic review aimed to comprehensively analyze the genotypic and phenotypic spectra of RUNX2 variants in CCD patients, assess their distribution across functional regions, and investigate genotype–phenotype correlations. This review included 569 reported variants and 453 CCD patients from 103 articles. Of 569 variants, in-frame variants constituted 48.68%, while null variants accounted for 51.32%. Regarding locations, RUNX2 variants were predominantly located in the RHD (55.54%), followed by PST (16.34%), NMTS (6.33%), QA (4.75%), VWRPY (1.23%), and NLS (1.41%) regions while 10.19% were in non-coding regions. In-frame variants occurred primarily in the RHD (90.97%), while null variants were found across various regions of RUNX2. Data analysis revealed a correlation between variant location and specific skeletal features in CCD patients. Missense variants, predominantly found within the functionally critical RHD, were significantly associated with supernumerary teeth, macrocephaly, metopic groove, short ribs, and hypoplastic iliac wings compared to nonsense variants. They were also significantly associated with delayed fontanelle closure, metopic synostosis, hypertelorism, limited shoulder abduction, pubic symphysis abnormalities, and hypoplastic iliac wings compared to in-frame variants found in other regions. These findings underscore the critical role of the RHD, with missense RHD variants having a more severe impact than nonsense and other in-frame variants. Additionally, in-frame insertions and deletions in RUNX2 were associated with fewer CCD features, compared to missense, frameshift, and nonsense variants. Null variants in the NLS region exhibited weaker associations with delayed fontanelle closure, supernumerary teeth, Wormian bones, and femoral head hypoplasia than variants in other regions. Moreover, the NLS variants did not consistently alter nuclear localization, questioning the role of NLS region in nuclear import. In summary, this comprehensive review significantly advances our understanding of CCD, facilitating improved phenotype-genotype correlations, enhanced clinical management, and a deeper insight into RUNX2 functional domains. This knowledge has the potential to guide the development of novel therapeutic targets for skeletal disorders.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12967-024-05904-2.

Keywords: Cleidocranial dysplasia, Data, Genes, Humans, Mutation, Prevalence, Skeleton, Supernumerary teeth

Introduction

Cleidocranial dysplasia (CCD, OMIM #119600), estimated to affect approximately one in a million individuals, is a rare genetic disorder characterized by unique skeletal anomalies affecting the clavicles and the skull, as well as dental irregularities such as retained deciduous teeth and supernumerary and unerupted permanent teeth, often accompanied by cyst formation [1, 2]. Unique facial features of CCD were a prominent forehead, midfacial hypoplasia, and hypertelorism. Additionally, individuals with CCD may exhibit wide pelvic joints, delayed growth of the pubic bone, scoliosis, and brachydactyly [3, 4]. Treatment for CCD is tailored to address individual symptoms, which may involve orthodontic and oral surgical interventions to remove extra teeth and facilitate the eruption of impacted teeth. Additionally, facial reconstructive surgeries may be performed to improve function and esthetics.

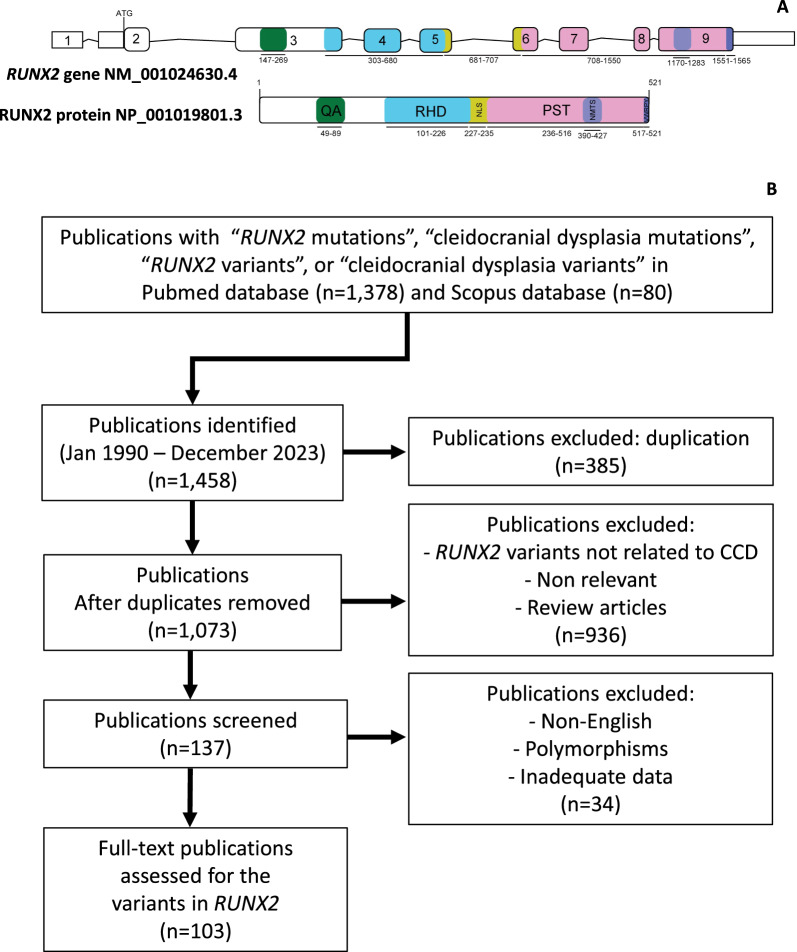

CCD is caused by variants in the runt-related transcription factor 2 gene (RUNX2) gene (OMIM *600211) [1, 5–7]. RUNX2 is a transcription factor that plays a central role in osteoblast differentiation, as well as bone formation and maintenance [8, 9]. Its activity is tightly regulated by a complex interplay of signaling pathways, co-factors, and epigenetic modifications, ensuring precise control of bone-related gene expression [10. RUNX2 consists of nine exons encoding the 521-amino acids of the RUNX2 protein, which includes a poly-glutamine and poly-alanine (QA) repeat (amino acids 49–89), a runt homologous domain (RHD, amino acids 101–226), a nuclear localization signal (NLS, amino acids 227–235), a proline–serine–threonine-rich (PST, amino acids 236–516), a nuclear matrix targeting signal (NMTS, amino acids 390–427), and a VWRPY pentapeptide sequence (amino acids 517–521) region [11–13]. The QA and PST regions serve as transactivation regions. The NLS regulates the nuclear translocation of RUNX2 protein. The highly conserved RHD facilitates DNA binding and the VWRPY pentapeptide sequence functions as a transcriptional repression region (Fig. 1A) [11]. While pathogenic variants within the coding region of RUNX2 are well-established as causative for CCD, non-coding variants also demonstrate a significant contribution to the phenotypic spectrum. These non-coding variants can disrupt splicing, generating aberrant RUNX2 isoforms with altered function, potentially contributing to CCD development [14].

Fig. 1.

Overview of RUNX2 gene and protein structure with literature search process. A Schematic diagrams of RUNX2 gene and protein. B Flowchart outlining the literature search and article selection process. QA poly-glutamine and poly-alanine repeat domain, RHD runt homologous domain, NLS nuclear localization signal, PST proline-serine-threonine-rich domain, NMST nuclear matrix targeting sequence, VWRPY pentapeptide sequence

Despite the growing number of CCD cases reported with pathogenic RUNX2 variants—currently exceeding 600 cases and 200 variants—there is a notable absence of systematic reviews on CCD-RUNX2 associations. The review by Jaruga et al. highlights the complex genotype–phenotype correlations in CCD, driven by diverse variants in RUNX2. Most commonly, variants within the RHD are linked to classic CCD symptoms, such as hypoplastic clavicles, delayed fontanelle closure, and dental abnormalities. However, phenotype severity varies significantly, even among individuals with similar genetic changes. Certain variants outside the RHD exhibit a milder phenotype primarily marked by dental anomalies. While this review underscores the challenges in defining precise genotype–phenotype correlations for CCD, it reveals trends regarding the impact of variant location and domain-specific disruptions on the condition's phenotypic spectrum [15].

This gap in research hinders clinicians' ability to deliver accurate diagnoses, prognoses, and prospective genetic engineering therapeutics for patients. Additionally, detailing the phenotypic spectrum of CCD and its correlation with specific RUNX2 variants stands as a pivotal pursuit in comprehending the intricate interplay between genetics and clinical manifestations. Therefore, this systematic review aims to delineate the diverse clinical presentations of CCD and the spectrum of RUNX2 variants, as well as explore genotype–phenotype associations.

Materials and methods

Bibliographic search

This study was performed according to the PRISMA 2020 guideline for reporting systematic reviews [16]. The systematic search covered from January 1990 to December 2023 and included articles that reported CCD associated with RUNX2 variants. The Pubmed and Scopus searches were conducted using the terms “RUNX2 variants”, “RUNX2 mutations”, “Cleidocranial dysplasia variants” or “Cleidocranial dysplasia mutations”. After removing the duplicate articles, the relevant articles were included if they met the following criteria: (1) the RUNX2 variant was identified as the CCD-causative gene and (2) the articles had an adequate description of the clinical phenotypes. The articles reporting RUNX2 polymorphisms, non-English language association studies, and literature reviews were excluded. The protocol was submitted to PROSPERO (CRD42023424847) (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?RecordID=424847).

Data extraction and analysis

The data extraction procedure was conducted by three independent reviewers (ST, KT, and SW).

The reviewers recorded the types and locations of the RUNX2 variants, along with the clinical phenotypic characteristics observed in each patient. To ensure accuracy, clinical images and radiographs were checked whenever available to corroborate the phenotypic descriptions provided in the text.

Variants in RUNX2 (CCDS43467.2, NM_001024630.4, NP_001019801.3) were categorized into two main groups according to a previous publication [17]. The first group consisted of in-frame variants, which included missense variants (mutations involving a single nucleotide resulting in a different amino acid) and in-frame insertions or deletions (changes where the reading frame remains unaltered). The second group comprised null variants, which encompassed frameshift variants (truncated), nonsense variants (mutations leading to premature stop codons), out-of-frame insertions or deletions (changes that disrupt the reading frame), and splicing variants (initiation codon). Null variants were characterized as alterations within the gene that either impede or diminish its transcription into RNA and/or its translation into a functional protein. The variant nomenclature adhered to the guidelines outlined by the Human Genome Variation Society (HGVS) [18].

The variants were further classified according to their location on the gene or protein comprising the QA, RHD, NLS, PST, NMTS, VWRPY, uncharacterized and non-coding regions. The analysis identified the following as the key clinical features of CCD according to variant type: clavicle defect, fontanelle defect, and supernumerary teeth [6]. The percentages of each clinical feature were calculated based on the total number of patients affected by each feature.

Clinical features of CCD were extracted from patient records and categorized as either present, absent, or not applicable (NA) if no information was available. The incidence of each clinical feature was then calculated based on the proportion of patients with the feature present, excluding those for whom data was not reported.

Statistical analysis

The Chi-square test (performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, IBM Corp, NY, USA) was utilized to compare the prevalence of clinical phenotype among variant types and different regions of RUNX2. A significant difference was defined as p-value < 0.05 (*), p-value < 0.01 (**), and p-value < 0.001(***).

Results

Overview of RUNX2 variants in CCD patients

One hundred and three articles (n = 103) reporting patients with CCD and RUNX2 were included for analysis (Fig. 1B, Supplementary Table 1). Five hundred and sixty-nine patients that carry RUNX2 variants (n = 569) were identified, comprising 277 in-frame variants (277/569, 48.68%), which included missense variants (267/277, 96.39%), in-frame deletions (6/277, 2.17%), and in-frame insertions (4/277, 1.44%)]. The remaining 292 null variants (292/569, 51.32%), consisting of frameshift variants (140/292, 47.95%), nonsense variants (94/292, 32.19%), splicing variants (56/292, 19.18%), out-of-frame insertion (1/292, 0.34%), and out-of-frame deletion (1/292, 0.34%) (Fig. 2A, Supplementary Tables 2–4).

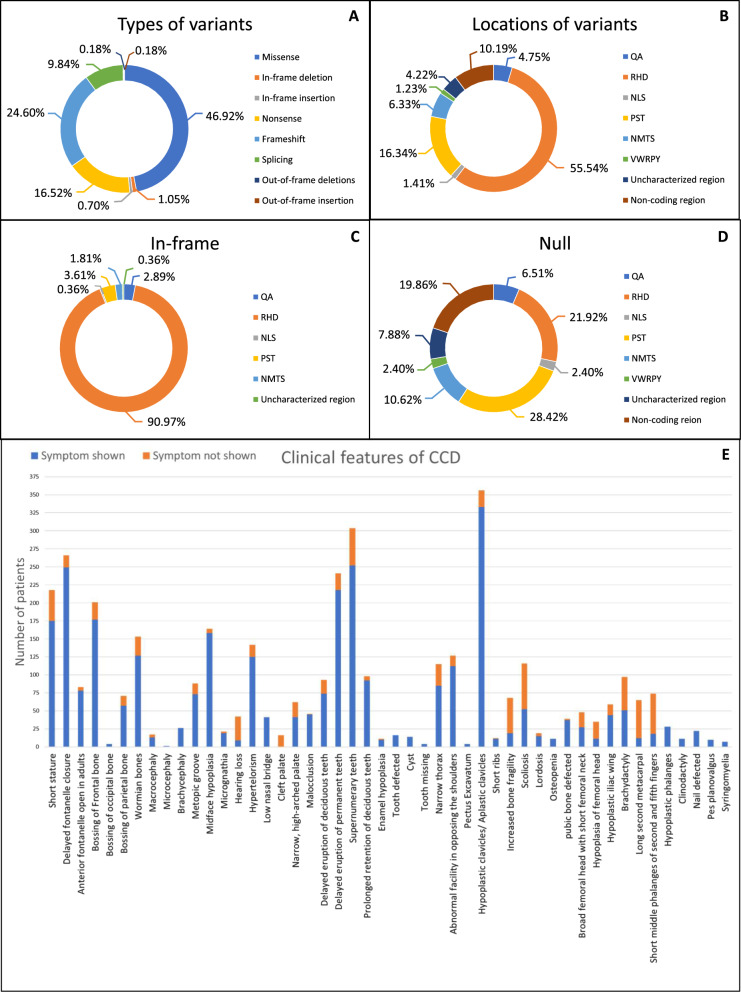

Fig. 2.

Prevalence of RUNX2 variants and clinical features in patients with CCD. A Variant types prevalence. B Region-specific variant distribution. C Prevalence of in-frame variants. D Prevalence of null variants. E A schematic diagram illustrating the incidence rates of individual phenotypic features in CCD

The 569 variants were predominantly located in the RHD (316/569, 55.54%), followed by the PST region (93/569, 16.34%), NMTS region (36/569, 6.33%), QA region (27/569, 4.75%), NLS region (8/569, 1.41%), and VWRPY region (7/569, 1.23%). Additionally, there were variants located in non-coding regions (58/569, 10.19%) and in uncharacterized regions (24/569, 4.22%) (Fig. 2B, Supplementary Table 5).

Considering the 277 in-frame variants group, the majority were found in the RHD region (252/277, 90.97%), with fewer instances observed in the PST (10/277, 3.61%), QA (8/277, 2.89%), NMTS (5/277, 1.81%), NLS (1/277, 0.36%), and uncharacterized regions (1/277, 0.36%) (Fig. 2C, Supplementary Table 6).

Conversely, 292 null variants were distributed across various regions, including the PST (83/292, 28.42%), RHD (64/292, 21.92%), NMTS (31/292, 10.62%), QA (19/292, 6.51%), NLS (7/292, 2.40%), and VWRPY (7/292, 2.40%). Variants were also identified in non-coding regions (58/292, 19.86%) and uncharacterized regions (23/292, 7.88%) (Fig. 2D, Supplementary Table 7).

Clinical features of CCD patients

Detailed phenotype data were retrieved for 453 CCD patients. Among these patients, 219 patients had in-frame variants and 234 cases had null variants. The three common symptoms observed across CCD patients consisted of delayed closure of cranial sutures, hypoplastic or aplastic clavicles, and dental abnormalities. Dental anomalies included delayed eruption of teeth, supernumerary teeth, enamel hypoplasia, and tooth defects such as dentin dysplasia, fusion tooth, microdontia, and impaired root development. Craniofacial features involved open anterior fontanelle, macrocephaly, bossing of the frontal, occipital, and parietal bones, midface hypoplasia, micrognathia, and hypertelorism. Skeletal presentations comprised short stature, narrow thorax, pectus excavatum, pes planovalgus, short ribs, increased bone fragility, scoliosis, brachydactyly, and defects in multiples bones including the pubic bone, femoral head, and iliac wing. Cleft palate, clinodactyly, nail defects, pectus excavatum, and syringomyelia were noted in a few CCD patients (Fig. 2E).

Genotypic characterization of the three classical CCD features: clavicle defects, delayed closure of the fontanelle, and supernumerary teeth

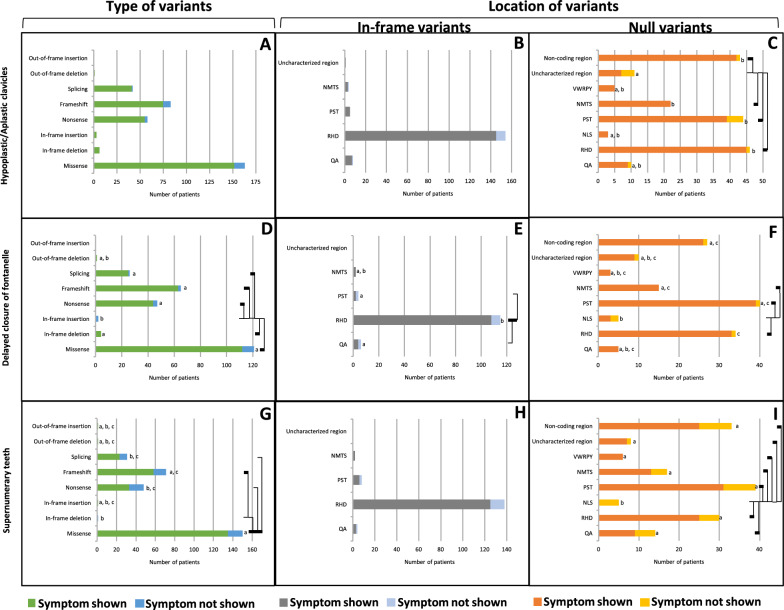

Clavicle defects (hypoplasia/aplasia) were observed in 333 CCD patients, demonstrating clear manifestations of symptoms in CCD. The defects showed no statistically significant difference in prevalence (p = 0.755, Table 1) among any types of variants, including in-frame deletion, in-frame insertion, out-of-frame deletion, splicing, nonsense, missense, and frameshift variants (100%, 100%, 100%, 97.6%, 94.8%, 93.3%, 90.4%, respectively) (Fig. 3A, Supplementary Table 8). The 161 CCD patients carrying in-frame variants exhibited no statistically significant difference in prevalence (p = 0.509, Table 1) across the regions including the PST, uncharacterized, RHD, QA, and NMTS (100%, 100%, 94.2%, 87.5%, and 75%, respectively) (Fig. 3B, Supplementary Table 9). Conversely, 172 cases with null variants showed significantly higher prevalence (p = 0.002, Table 1) in the NMTS, RHD, non-coding region, and PST (100%, 97.8%, 97.7%, and 88.6%, respectively), compared to the uncharacterized region (63.6%) (Fig. 3C, Supplementary Table 10).

Table 1.

Chi-Square analysis of CCD features associated with the type and location of RUNX2 variants

| Types of variants | Locations | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| In-frame | Null | ||

| p-value | p-value | p-value | |

| Key CCD features | |||

| Hypoplastic/aplastic clavicles | 0.755 | 0.509 | 0.002** |

| Delayed fontanelle closure | < 0.001*** | 0.002** | 0.013* |

| Supernumerary teeth | 0.007* | 0.379 | 0.004** |

| Growth | |||

| Height | |||

| Short stature | 0.626 | 0.247 | 0.028* |

| Head and neck | |||

| Head | |||

| Open anterior fontanelle reported in adults | 0.406 | 0.933 | 0.214 |

| Bossing of frontal bone | 0.611 | 0.117 | 0.043* |

| Bossing of occipital bone | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Bossing of parietal bone | 0.170 | 0.745 | 0.206 |

| Wormian bones | 0.238 | 0.266 | 0.045* |

| Macrocephaly | 0.042* | 0.753 | 0.171 |

| Microcephaly | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Brachycephaly | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Face | |||

| Metopic groove | 0.002** | < 0.001*** | 0.012* |

| Midface hypoplasia | 0.061 | N/A | 0.692 |

| Micrognathia | 0.352 | 0.124 | N/A |

| Ears | |||

| Hearing loss | 0.807 | 0.029* | 0.719 |

| Eyes | |||

| Hypertelorism | 0.775 | < 0.001*** | 0.310 |

| Nose | |||

| Low nasal bridge | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Mouth | |||

| Cleft palate | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Narrow, high-arched palate | 0.322 | 0.268 | 0.562 |

| Malocclusion | 0.949 | 0.966 | N/A |

| Teeth | |||

| Delayed eruption of deciduous teeth | 0.245 | 0.675 | 0.217 |

| Delayed eruption of permanent teeth | 0.063 | 0.797 | 0.362 |

| Prolonged retention of deciduous teeth | 0.611 | 0.966 | 0.328 |

| Enamel hypoplasia | 0.517 | N/A | 0.072 |

| Tooth defected | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Cyst | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Tooth missing | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Chest | |||

| External features | |||

| Narrow thorax | 0.266 | 0.862 | 0.070 |

| Abnormal facility in opposing the shoulders | 0.640 | 0.018* | 0.003** |

| Pectus Excavatum | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Short ribs | 0.017* | N/A | 0.029* |

| Skeletal | |||

| Bone | |||

| Increased bone fragility | 0.749 | 0.432 | 0.520 |

| Spine | |||

| Scoliosis | 0.451 | 0.583 | 0.488 |

| Lordosis | 0.266 | N/A | 0.049* |

| Osteopenia | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Pelvis | |||

| Pubic bone defected | 0.965 | < 0.001*** | 0.485 |

| Broad femoral head with short femoral neck | 0.163 | 0.147 | 0.067 |

| Hypoplasia of femoral head | 0.078 | 0.298 | 0.032* |

| Hypoplastic iliac wing | < 0.001*** | 0.044* | 0.005** |

| Hands/feet | |||

| Brachydactyly | 0.516 | 0.547 | 0.217 |

| Long second metacarpal | 0.076 | 0.867 | 0.217 |

| Short middle phalanges of second and fifth fingers | 0.055 | 0.578 | 0.110 |

| Hypoplastic phalanges | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Clinodactyly | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Nail defected | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Pes planovalgus | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Neurologic | |||

| Peripheral nervous system | |||

| Syringomyelia | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Significant denotes specific differences: *p < .05, **p < .01, and ***p < .001

Fig. 3.

Classical phenotype of CCD patients carrying variants in RUNX2. A–C Clavicle defects. D–F Delayed fontanelle closure. G–I Supernumerary teeth. A, D, G Prevalence of variant types. B, E, H Prevalence of In-frame variants. C, F, I Prevalence of null variants. Connecting lines show statistical differences

Delayed fontanelle closure, detected in 249 CCD patients, showed a significantly higher prevalence (p < 0.001, Table 1) in patients with in-frame deletion, out-of-frame deletion, frameshift, splicing, nonsense, and missense variants (100%, 100%, 96.9%, 96.2%, 93.6%, and 92.6%, respectively) compared to in-frame insertion (0%) (Fig. 3D, Supplementary Table 11). Among 116 CCD patients with in-frame variants, delayed fontanelle closure showed significantly higher prevalence (p = 0.002, Table 1) in the RHD (93.9%) compared to the QA and PST (66.7% and 50%, respectively) (Fig. 3E, Supplementary Table 12). Moreover, in 133 CCD patients with null variants, the prevalence of delayed fontanelle closure was significantly higher (p = 0.013, Table 1) in the NMTS, PST, RHD, non-coding, and uncharacterized regions (100%, 97.5%, 97.1%, 96.3%, and 90%, respectively) compared to the NLS (60%) (Fig. 3F, Supplementary Table 13).

Supernumerary teeth, observed in 252 CCD patients, showed a significantly higher prevalence (p = 0.007, Table 1) with missense variants (90%) compared to splicing, nonsense, and in-frame deletion (74.2%, 68.8%, and 0%, respectively). Moreover, the frameshift variants (81.7%) exhibited a higher prevalence than the in-frame deletion (0%) (Fig. 3G, Supplementary Table 14). Among 136 patients with in-frame variants, no statistically significant difference was observed (p = 0.379, Table 1) among different locations, including NMTS, RHD, QA, and PST (100%, 90.6%, 75%, and 75%, respectively) (Fig. 3H, Supplementary Table 15). Conversely, 116 patients with null variants showed a significantly higher prevalence (p = 0.004, Table 1) in the VWRPY, uncharacterized region, RHD, PST, NMTS, non-coding regions, and QA (100%, 87.5%, 83.3%, 79.5%, 76.5%, 75.8%, and 64.3%, respectively) compared with NLS (0%) (Fig. 3I, Supplementary Table 16).

Genotypic characterization of other CCD features

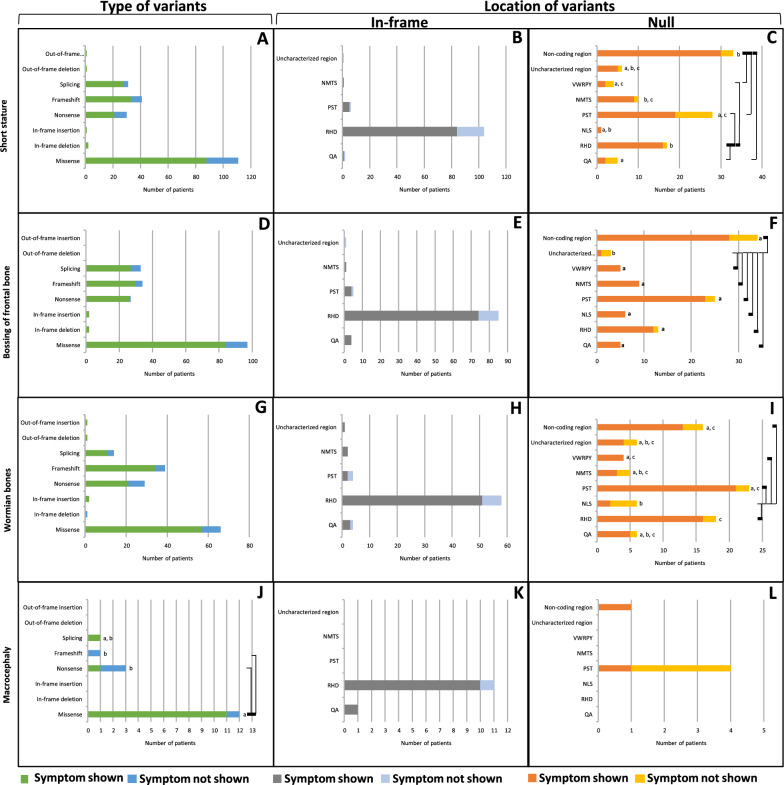

Short stature, a condition characterized by an individual's height significantly below the average for their age and gender, was observed in 175 patients. It demonstrated no statistically significant difference in prevalence (p = 0.626, Table 1) in any types of variants, including in-frame deletion, in-frame insertion, out-of-frame deletion, out-of-frame insertion, splicing, frameshift, missense, and nonsense (100%, 100%, 100%, 100%, 90.3%, 80.5%, 79.3%, 70%, respectively) (Fig. 4A, Supplementary Table 17). Ninety-one CCD patients with in-frame variants exhibited no statistically significant difference in prevalence (p = 0.247, Table 1) in the NMTS, PST, RHD, QA and uncharacterized regions (100%, 83.3%, 80.8%, 50%, 0%, respectively) (Fig. 4B, Supplementary Table 18). Conversely, 84 CCD patients with null variants showed a significantly higher prevalence (p = 0.028, Table 1) in the RHD and non-coding regions (94.1% and 90.9%, respectively) compared with the PST, VWRPY, and QA (67.9%, 50.0%, 40.0%, respectively). Moreover, the prevalence of NMTS (90.0%) was higher than that of QA (40.0%) (Fig. 4C, Supplementary Table 19).

Fig. 4.

Growth and craniofacial abnormalities of CCD patients carrying variants in RUNX2. A–C Short stature. D–F Bossing of Frontal bone. G–I Wormian bones. J–L Macrocephaly. A, D, G, J Prevalence of variant types. B, E, H, K Prevalence of In-frame variants. C, F, I, L Prevalence of null variants. Connecting lines show statistical differences as

Frontal bone bossing, a condition characterized by an abnormal protrusion of the forehead bone, was observed in 171 patients. The prevalence of this symptom showed no statistically significant difference (p = 0.611, Table 1) among different types of variants, including in-frame deletion, in-frame insertion, nonsense, frameshift, missense, and splicing (100%, 100%, 96.3%, 88.2%, 86.6%, and 81.8%, respectively) (Fig. 4D, Supplementary Table 20). In-frame variants, found in 83 CCD patients, exhibited no significantly difference in prevalence (p = 0.117, Table 1) across regions, including the QA, PST, RHD, and NMTS (100%, 100%, 87.1%, 80%, and 0%, respectively) (Fig. 4E, Supplementary Table 21). Conversely, null variants, found in 89 CCD patients, showed a significantly higher prevalence (p = 0.043, Table 1) in the QA, NLS, NMTS, VWRPY, RHD, PST, and non-coding regions (100%, 100%, 100%, 100%, 92.3%, 92%, and 82.4%, respectively) compared with the uncharacterized regions (33.3%) (Fig. 4F, Supplementary Table 22).

Wormian bones, small additional bones found within the skull sutures, were observed in 127 patients. Their prevalence exhibited no significant difference (p = 0.238, Table 1) across different types of variants, including in-frame insertion, out-of-frame deletion, out-of-frame insertion, frameshift, missense, splicing, nonsense, and in-frame deletion (100%, 100%, 100%, 87.2%, 86.4%, 78.6%, 72.4%, and 0%, respectively) (Fig. 4G, Supplementary Table 23). In-frame variants, found in 59 CCD patients, exhibited no significant difference in prevalence (p = 0.266, Table 1) across different regions, including NMTS, uncharacterized region, RHD, QA, and PST (100%, 100%, 87.9%, 75%, and 50%, respectively) (Fig. 4H, Supplementary Table 24). Conversely, null variants, detected in 68 CCD patients, showed a significantly higher prevalence (p = 0.045, Table 1) in the VWRPY, PST, RHD, and non-coding (100%, 91.3%, 88.9%, and 81.3%) compared with the NLS (33.3%) (Fig. 4I, Supplementary Table 25).

Macrocephaly, an abnormally large head size, was noted in 13 patients. Its prevalence was significantly higher (p = 0.042, Table 1) with missense variants (91.7%) compared to nonsense and frameshift variants (33.3% and 0%, respectively). (Fig. 4J, Supplementary Table 26). In contrast, in-frame variants, 11 CCD patients, exhibited no statistically significant difference in prevalence (p = 0.753, Table 1) in patients with QA, and RHD regions (100% and 90.9%) (Fig. 4K, Supplementary Table 27). Additionally, null variants, 2 CCD patients, demonstrated no statistically significant difference in prevalence (p = 0.171, Table 1) in patients with non-coding and PST region (100% and 25%) (Fig. 4L, Supplementary Table 28).

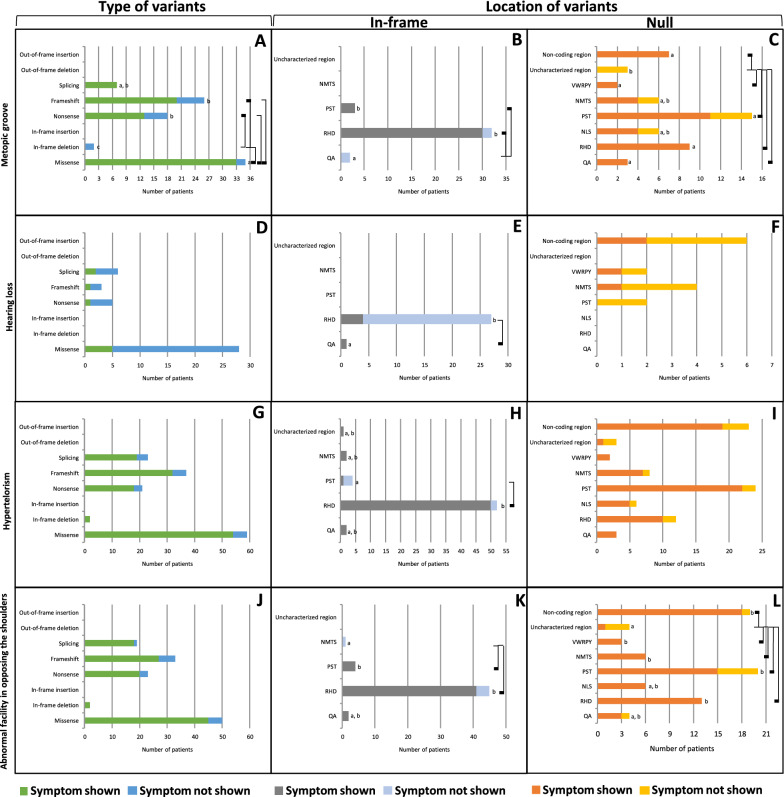

A metopic groove, a persistent midline furrow on the forehead bone found in 73 patients, showed a significantly higher prevalence (p = 0.002, Table 1) with splicing, missense, frameshift, and nonsense variants (100%, 94.3%, 76.9%, and 72.2%, respectively) compared with in-frame deletion (0%). Notably, missense variants showed a significantly higher prevalence than frameshift and nonsense (Fig. 5A, Supplementary Table 29). Furthermore, in-frame variants, observed in 33 CCD patients, exhibited a significantly higher prevalence (p < 0.001, Table 1) in the PST and RHD (100% and 93.8%, respectively) compared with the QA (0%) (Fig. 5B, Supplementary Table 30). Additionally, null variants, found 40 CCD patients, showed a significantly higher prevalence (p = 0.012, Table 1) the QA, RHD, VWRPY, non-coding region, and PST (100%, 100%, 100%, 100%, and 73.3%, respectively) compared with the uncharacterized regions (0%) (Fig. 5C, Supplementary Table 31).

Fig. 5.

Cranial and sensory abnormalities of CCD patients carrying variants in RUNX2. A–C Metopic groove. D–F Hearing loss. G–I Hypertelorism. J–L Abnormal facility in opposing the shoulders. A, D, G, J Prevalence of variant types. B, E, H, K Prevalence of In-frame variants. C, F, I, L Prevalence of null variants. Connecting lines show statistical differences as

Hearing loss, observed in 9 patients, demonstrated no significant difference in prevalence (p = 0.807, Table 1) across any types of variants, including frameshift, splicing, nonsense, and missense (33.3%, 33.3%, 20%, and 17.9%, respectively) (Fig. 5D, Supplementary Table 32). On the other hand, in-frame variants, found in 5 CCD patients, exhibited a significantly higher prevalence (p = 0.029, Table 1) in the QA (100%) compared with the RHD (14.8%) (Fig. 5E, Supplementary Table 33). However, null variants, found 4 CCD patients, showed no significant difference in prevalence (p = 0.719, Table 1) among different regions, including the VWRPY, non-coding, NMTS, and PST regions (50%, 33.3%, 25%, and 0%, respectively) (Fig. 5F, Supplementary Table 34).

Hypertelorism, a condition characterized by an abnormally increased distance between the orbits of the eyes, was observed in 125 patients. It showed no significant difference in prevalence (p = 0.755, Table 1) across any types of variants, including in-frame deletion, missense, frameshift, nonsense, and splicing (100%, 91.5%, 86.5%, 85.7%, and 82.6, respectively) (Fig. 5G, Supplementary Table 35). In-frame variants, found in 56 CCD patients, exhibited a significantly higher prevalence (p < 0.001, Table 1) in the RHD (96.2%) compared with the PST (25%) (Fig. 5H, Supplementary Table 36). Conversely, null variants, detected in 69 CCD patients, showed no significant difference in prevalence (p = 0.310, Table 1) across different regions, including the QA, VWRPY, PST, NMTS, RHD, NLS, non-coding region, and uncharacterized region (100%, 100%, 91.7%, 87.5%, 83.3%, 83.3%, 82.6% and 33.3%, respectively) (Fig. 5I, Supplementary Table 37).

Abnormal facility in opposing the shoulders, exhibited in 112 patients, showed no significant difference in prevalence (p = 0.640, Table 1) across any types of variants, including splicing, in-frame deletion, missense, nonsense, and frameshift (100%, 94.7%, 90.0%, 87%, and 81.8%, respectively) (Fig. 5J, Supplementary Table 38). In-frame variants, observed in 47 CCD patients, exhibited no significant difference in prevalence (p = 0.018, Table 1) in any regions including the QA, PST, RHD, and NMTS (100%, 100%, 91.1%, and 0%, respectively) (Fig. 5K, Supplementary Table 39). Moreover, null variants, found in 65 CCD patients, showed a significantly higher prevalence (p = 0.003, Table 1) in the RHD, NMTS, VWRPY, non-coding region, and PST (100%, 100%, 100%, 94.7%, and 75%, respectively) compared with the uncharacterized regions (25%) (Fig. 5L, Supplementary Table 40).

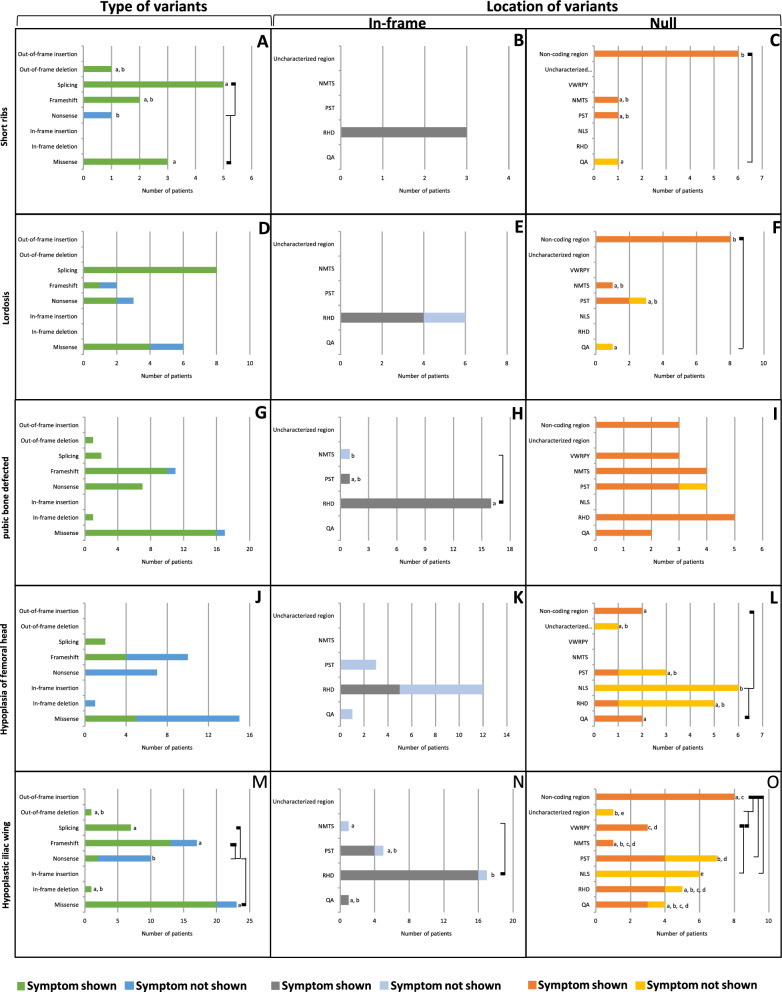

Short ribs, observed in 11 patients, exhibited a significantly higher prevalence (p = 0.017, Table 1) with missense and splicing variants (100%, 100%, respectively) compared with nonsense (0%) (Fig. 6A, Supplementary Table 41). In-frame variants, detected in 3 CCD patients, were observed in the RHD region exclusively (100%) (Fig. 6B, Supplementary Table 42). In contrast, null variants, found in 8 CCD patients, showed a significantly higher prevalence (p = 0.029, Table 1) in the non-coding region (100%) compared with the QA (0%) (Fig. 6C, Supplementary Table 43).

Fig. 6.

Axial and appendicular skeletal anomalies of CCD patients carrying variants in RUNX2. A–C Short ribs. D–F Lordosis. G–I Pubic bone defected. J–L Hypoplasia of femoral head. M–O Hypoplastic iliac wing. A, D, G, J, M Prevalence of variant types. B, E, H, K, N Prevalence of In-frame variants. C, F, I, L, O Prevalence of null variants. Connecting lines show statistical differences

Lordosis, the forward curvature of the spine in the neck or lower back, was observed in 15 patients. Its prevalence showed no significant difference (p = 0.266, Table 1) across any types of variants, including splicing, missense, nonsense, and frameshift (100%, 66.7%, 66.7%, and 50%, respectively) (Fig. 6D, Supplementary Table 44). In-frame variants, found in 4 CCD patients, were observed exclusively in the RHD (66.7%) (Fig. 6E, Supplementary Table 45). Conversely, null variants, detected in 11 CCD patients, showed a significantly higher prevalence (p = 0.049, Table 1) in the non-coding region (100%) compared with the QA (0%) (Fig. 6F, Supplementary Table 46).

Pubic bone defects, observed in 37 patients, showed no significant difference in prevalence (p = 0.965, Table 1) across any types of variants, including nonsense, in-frame deletion, splicing, out-of-frame deletion, missense, and frameshift (100%, 100%, 100%, 100%, 94.1%, and 90.9%, respectively) (Fig. 6G, Supplementary Table 47). In-frame variants, detected in 17 CCD patients, exhibited a significantly higher prevalence (p < 0.001, Table 1) in the RHD (100%) compared with the NMTS (0%) (Fig. 6H, Supplementary Table 48). However, null variants, found in 20 CCD patients, showed no significant difference in prevalence (p = 0.485, Table 1) across different regions including the QA, RHD, NMTS, VWRPY, non-coding region, and PST regions (100%, 100%, 100%, 100%, 100%, 75%, respectively) (Fig. 6I, Supplementary Table 49).

Hypoplasia of femoral head, observed in 11 patients, exhibited no significant difference in prevalence (p = 0.078, Table 1) across any types of variants, including splicing, frameshift, missense, nonsense, and in-frame deletion (100%, 40%, 33.3%, 0%, 0%, respectively) (Fig. 6J, Supplementary Table 50). In-frame variants, found in 5 CCD patients, showed no significant difference in prevalence (p = 0.298, Table 1) across regions, including the RHD, QA, and PST regions (41.7%, 0%, and 0%, respectively) (Fig. 6K, Supplementary Table 51). In contrast, null variants, detected in 6 CCD patients, displayed a significantly higher prevalence (p = 0.032, Table 1) in the QA and non-coding regions (100% and 100%, respectively) compared with the NLS (0%) (Fig. 6L, Supplementary Table 52).

Hypoplastic iliac wing, present in 44 patients, was significantly higher (p < 0.001, Table 1) with the splicing, missense, and frameshift variants (100%, 87%, and 76.5%, respectively) compared with nonsense variants (20%) (Fig. 6M, Supplementary Table 53). In-frame variants, detected in 21 CCD patients, exhibited a significantly higher prevalence (p = 0.044, Table 1) in the RHD (100%) compared with the NMTS (0%) (Fig. 6N, Supplementary Table 54). Moreover, null variants, found in 23 CCD patients, showed a significantly higher prevalence (p = 0.005, Table 1) in the NMTS, VWRPY, non-coding region, RHD, QA, and PST (100%, 100%, 100%, 80%, 75%, 57.1%, respectively), compared with the NLS (0%). Additionally, the prevalence in the non-coding region was significantly higher than the PST and uncharacterized regions (0%). The VWRPY region also exhibited a significantly higher prevalence than the uncharacterized region (Fig. 6O, Supplementary Table 55).

Various anomalies reported in CCD patients did not show significant differences across different types of variants, locations for in-frame variants, or locations for null variants. These symptoms include an open anterior fontanelle in adults, bossing of the occipital bone, bossing of the parietal bone, microcephaly, brachycephaly, midface hypoplasia, micrognathia, low nasal bridge, cleft palate, narrow high-arched palate, malocclusion, delayed eruption of deciduous and permanent teeth, prolonged retention of deciduous teeth, enamel hypoplasia, tooth defects, cysts, missing teeth, narrow thorax, pectus excavatum, abnormalities in ribs and sternum, increased bone fragility, scoliosis, osteopenia, broad femoral head with short femoral neck, brachydactyly, long second metacarpal, short middle phalanges of the second and fifth fingers, hypoplastic phalanges, clinodactyly, nail defect, hypoplasia of the femoral head, hypoplastic iliac wing, pes planovalgus, and syringomyelia were (Supplementary Table 1).

Discussion

Our analysis of RUNX2 variants revealed a distinct distribution pattern, with in-frame missense variants predominantly concentrated within the RHD (90.97%), while null variants, leading to protein loss-of-function, were distributed throughout the gene [19]. Notably, missense variants were significantly more prevalent in individuals presenting with supernumerary teeth, macrocephaly, metopic groove, short ribs, and hypoplastic iliac wings compared to nonsense variants. Further analysis of in-frame variants within the RHD revealed a strong association with multiple anomalies, including delayed fontanelle closure, metopic synostosis, hypertelorism, limited shoulder abduction, pubic symphysis abnormalities, and hypoplastic iliac wings, compared to in-frame variants in other regions. These findings suggest a potential genotype–phenotype correlation, where the specific location of the variant within the RHD of RUNX2 may significantly influence the clinical manifestation. This enrichment of missense variants with specific phenotypes points to their potential functional significance. The observed clustering of missense variants within the RHD, a highly conserved domain across species [20], with established roles in DNA binding and protein–protein interactions [19, 20], highlights its critical importance for RUNX2 function. The RHD acts as a molecular conductor, facilitating RUNX2 activity by regulating its specific DNA binding and interactions with associated proteins. This enables RUNX2 to accurately discern and bind to specific sites on target genes. However, this process is not isolated. CBFβ, while not directly interacting with DNA, plays a crucial supporting role by stabilizing RUNX2 attachment to DNA and influencing its target gene specificity [11, 21]. This complex interplay between the RHD and CBFβ underscores the intricate nature of transcriptional regulation mechanisms. Variants that disrupt these interactions, particularly those enriched within the RHD, could potentially disrupt the precise molecular mechanisms critical for cellular differentiation and bone development. This, in turn, could explain the observed phenotype associations.

While null variants reduce RUNX2 function, missense variants within the RHD can exert a more severe phenotype due to their potential for dominant-negative effects. These missense variants, while not eliminating the protein entirely, might disrupt crucial interactions, leading to aberrant gene regulation and altered cellular function. By interfering with DNA binding, missense variants can disrupt an ability of RUNX2 to accurately recognize and bind to target gene sequences [3, 22]. This can result in inappropriate gene activation or repression, contributing to the observed phenotypic abnormalities. Furthermore, these variants can disrupt protein–protein interactions within the RHD, impacting the stability and functionality of RUNX2 complexes. Specifically, they can impair interactions with essential co-factors like CBFβ, leading to reduced stability, altered target specificity, and potentially interfering with the proper function of the wild-type protein [22, 23]. This disruption of critical interactions and potential dominant-negative effects contribute to the observed more severe phenotypes associated with missense variants within the RHD compared to null variants.

Previous studies have indicated that missense variants in RUNX2, often affecting the RHD and its DNA-binding ability, tend to cluster within that specific domain, while nonsense and frameshift variants show a more widespread distribution across the gene [15]. Our analysis indicates a potential correlation between domain size and variant frequency. As expected, larger domains like the PST exhibit a higher raw count of identified variants. Conversely, smaller regions such as the NLS and VWRPY show a lower number of observed variants. While this suggests that domain size may be a contributing factor to variant distribution, rigorous statistical analysis comparing observed versus expected variant frequencies, is necessary to determine if there is significant enrichment within specific domains that cannot be solely attributed to their size.

We observed that patients with in-frame insertions and deletions in RUNX2 did not commonly exhibit typical CCD features, such as delayed fontanelle closure, supernumerary teeth, and metopic synostosis. In contrast to missense variants, which were enriched within the RHD, most in-frame insertions and deletions were found in the QA regions, which contain variable-length polyglutamine and polyalanine tracts. These variations were usually short-length expansions or contractions that may not significantly disrupt RUNX2 function [24].

Regarding null variants, those in the NLS region of RUNX2 showed less severe phenotypes particularly delayed fontanelle closure, supernumerary teeth, Wormian bones, and femoral head hypoplasia compared to null variants in other regions. The NLS is known as “nuclear localization signal” and plays role in directing the RUNX2 protein to the nucleus, where it exerts its transcriptional regulatory functions. However, previous studies have identified variants, such as c.199C>T and c.90insC, which result in a truncated RUNX2 protein lacking the entire NLS region. Surprisingly, despite the absence of a functional NLS, this truncated protein can still be detected in both the nucleus and cytoplasm compartments [25, 26]. This dual localization suggests that alternative mechanisms or compensatory signals for nuclear import may exist, allowing RUNX2 to partially function even in the absence of a canonical NLS. It is also important to consider the potential impact of heterozygosity in the NLS region. The presence of one wild-type allele might still lead to subtle or context-dependent alterations in nuclear localization. These nuances could contribute to the phenotypic variability observed in CCD patients. The milder phenotypes observed with NLS-affecting null variants further support this notion of functional redundancy or adaptability. It is plausible that RUNX2 utilizes additional, yet unidentified pathways for nuclear localization and function, effectively mitigating the impact of NLS mutations. This highlights the complexity of RUNX2 regulation and emphasizes the need to further investigate these alternative mechanisms. Understanding the nuanced roles of protein domains like the NLS in RUNX2 not only enhances our knowledge of molecular mechanisms underlying skeletal development but also informs potential therapeutic strategies for conditions associated with RUNX2 dysregulation. Exploring these molecular pathways holds promise for uncovering novel insights into gene regulation and cellular differentiation processes that are essential for skeletal morphogenesis and homeostasis.

Apart from the coding variants in RUNX2, non-coding variants may also influence phenotypic presentation of CCD. Non-coding variants can be categorized based on their genomic locations, including promoter regions, introns, 3ʹ Untranslated Region (3'UTR), and intergenic regions, which house critical regulatory elements like transcription factor binding sites, enhancers, silencers, and miRNA binding sites. Variants within these elements can modulate RUNX2 expression, mRNA stability, and translation efficiency. For example, variants in miRNA binding sites within the 3'UTR can alter mRNA degradation rates, impacting RUNX2 protein abundance. Additionally, motifs such as AU-rich elements (AREs) in non-coding regions are essential in regulating RNA stability, and variants affecting these motifs may influence RUNX2 mRNA half-life [27]. These molecular changes often have context-dependent phenotypic consequences, varying with factors such as the variant’s location and tissue specificity. A comprehensive understanding of the interactions between non-coding variants, their molecular effects, and phenotypic outcomes is essential for unraveling the complexities of RUNX2 regulation and the pathogenesis of CCD.

Significant phenotypic variability is a hallmark of CCD, even among individuals harboring the same pathogenic RUNX2 variant. This phenotypic heterogeneity, driven by allelic heterogeneity and likely influenced by additional genetic and environmental factors, underscores the complexity of genotype–phenotype correlations in CCD. For instance, while the c.674G>A (p.Arg225Gln) variant in the RHD is associated with delayed fontanelle closure, this feature was not consistently observed within a single family [28]. Similarly, the presence of supernumerary teeth, a common CCD manifestation, varied among individuals carrying the c.674G>A variant [14]. Likewise, while clavicle defects and delayed fontanelle closure were noted in patients with the c.1171C>T (p.Arg391Ter) variant, the presence of supernumerary teeth differed between reported cases [28, 29]. Intriguingly, even within a single family harboring the c.1171C>T variant, the presence of Wormian bones was not uniform [29]. Our own analysis identified both the c.674G>A and c.1171C>T variants as recurrent hotspots, further emphasizing their association with a spectrum of CCD phenotypes [19]. These observations underscore the need for personalized approaches to CCD diagnosis and management, as clinical presentations can vary significantly despite shared genetic etiology.

Conclusions

This comprehensive systematic review demonstrates the association between different types and regions of RUNX2 variants and specific features of CCD, thereby advancing our understanding of genotype–phenotype correlations within the RUNX2 gene. We show that missense variants in the RHD are associated with more severe CCD phenotypes compared to null variants and other in-frame variants in different protein regions. Additionally, we highlight the NLS region, which might not play a critical role in nuclear localization. This study underscores the importance of considering both the type and location of RUNX2 variants in predicting the clinical manifestations of CCD. Future investigations should aim to unravel the intricate molecular pathways governing RUNX2 function to enhance diagnostic precision and potentially inform targeted therapeutic strategies for CCD and related disorders.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Material 1: Supplementary Table 1. RUNX2 variants and associated CCD features. Supplementary Table 2. The type of RUNX2 variants associated with CCD. Supplementary Table 3. The in-fame variants of RUNX2 associated with CCD. Supplementary Table 4. The null variants of RUNX2 associated with CCD. Supplementary Table 5. The regions of RUNX2 variants associated with CCD. Supplementary Table 6. In-frame RUNX2 variants associated with CCD. Supplementary Table 7. Null RUNX2 variants associated with CCD.

Supplementary Material 2: Supplementary Table 8. Distribution of different types of variants based on hypoplastic or aplastic clavicles. Supplementary Table 9. Distribution of in-frame variants based on hypoplastic or aplastic clavicles. Supplementary Table 10. Distribution of null variants based on hypoplastic or aplastic clavicles. Supplementary Table 11. Distribution of different types of variants based on delayed fontanelle closure. Supplementary Table 12. Distribution of in-frame variants based on delayed fontanelle closure. Supplementary Table 13. Distribution of null variants based on delayed fontanelle closure. Supplementary Table 14. Distribution of different types of variants based on supernumerary teeth. Supplementary Table 15. Distribution of in-frame variants based on supernumerary teeth. Supplementary Table 16. Distribution of null variants based on supernumerary teeth. Supplementary Table 17. Distribution of different types of variants based on short stature. Supplementary Table 18. Distribution of in-frame variants based on short stature. Supplementary Table 19. Distribution of null variants based on short stature. Supplementary Table 20. Distribution of the different types of variants based on bossing of frontal bone. Supplementary Table 21. Distribution of in-frame variants based on the bossing of frontal bone. Supplementary Table 22. Distribution of null variants based on bossing of frontal bone. Supplementary Table 23. Distribution of the different types of variants based on the Wormian bones. Supplementary Table 24. Distribution of in-frame variants based on Wormian bones. Supplementary Table 25. Distribution of null variants based on Wormian bones. Supplementary Table 26. Distribution of the different types of variants based on macrocephaly. Supplementary Table 27. Distribution of in-frame variants based on macrocephaly. Supplementary Table 28. Distribution of null variants based on macrocephaly. Supplementary Table 29. Distribution of the different types of variants based on metopic groove. Supplementary Table 30. Distribution of in-frame variants based on metopic groove. Supplementary Table 31. Distribution of null variants based on metopic groove. Supplementary Table 32. Distribution of the different types of variants based on hearing loss. Supplementary Table 33. Distribution of in-frame variants based on hearing loss. Supplementary Table 34. Distribution of null variants based on hearing loss. Supplementary Table 35. Distribution of the different types of variants based on hypertelorism. Supplementary Table 36. Distribution of in-frame variants based on hypertelorism. Supplementary Table 37. Distribution of null variants based on hypertelorism. Supplementary Table 38. Distribution of the different types of variants based on abnormal facility in opposing the shoulders. Supplementary Table 39. Distribution of in-frame variants based on abnormal facility in opposing the shoulders. Supplementary Table 40. Distribution of null variants based on abnormal facility in opposing the shoulders. Supplementary Table 41. Distribution of the different types of variants based on the short ribs. Supplementary Table 42. Distribution of in-frame variants based on the short ribs. Supplementary Table 43. Distribution of null variants based on the short ribs. Supplementary Table 44. Distribution of the different types of variants based on lordosis. Supplementary Table 45. Distribution of in-frame variants based on lordosis. Supplementary Table 46. Distribution of null variants based on lordosis. Supplementary Table 47. Distribution of the different types of variants based on pubic bone defects. Supplementary Table 48. Distribution of in-frame variants based on the pubic bone defects. Supplementary Table 49. Distribution of null variants based on pubic bone defects. Supplementary Table 50. Distribution of the different types of variants based on hypoplasia of femoral head. Supplementary Table 51. Distribution of in-frame variants based on the hypoplasia of femoral head. Supplementary Table 52. Distribution of null variants on hypoplasia of femoral head. Supplementary Table 53. Distribution of the different types of variants based on hypoplastic iliac wing. Supplementary Table 54. Distribution of in-frame variants based on hypoplastic iliac wing. Supplementary Table 55. Distribution of null variants based on hypoplastic iliac wing.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the use of ChatGPT (OpenAI, https://chat.openai.com) for checking English grammar in the preparation of this manuscript.

Abbreviations

- CCD

Cleidocranial dysplasia

- HGVS

Human Genome Variation Society

- NLS

Nuclear localization signal

- NMTS

Nuclear matrix targeting signal

- PTS

Proline–serine–threonine rich region

- RHD

Runt homologous domain

- RUNX2

Runt-related transcription factor 2

- QA

Poly-glutamine and poly-alanine repeat region

- VWRPY

VWRPY pentapeptide sequence

Author contributions

SP, TP contributed to conception, data analysis, drafted and critically revised the manuscript. KT, SW, SC contributed to data analysis. All authors read and gave their final approval and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This research was supported by the Ratchadapisek Sompoch Endowment Fund (2023), Chulalongkorn University (Meta_66_005_3200_002), Health Systems Research Institute, National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT) (N42A650229), and Thailand Science Research and Innovation Fund Chulalongkorn University (HEA_FF_68_008_3200_001). ST was supported by the Faculty of Dentistry and the Ratchadapisek Somphot Fund for Postdoctoral Fellowship, Chulalongkorn University.

Data availability

Original data generated and analyzed during this study are included in this published article or in the supplementary material.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Mundlos S. Cleidocranial dysplasia: clinical and molecular genetics. J Med Genet. 1999;36(3):177–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matthews-Brzozowska T, Hojan-Jezierska D, Loba W, Worona M, Matthews-Brzozowski A. Cleidocranial dysplasia-dental disorder treatment and audiology diagnosis. Open Med (Wars). 2018;13:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gao X, Li K, Fan Y, Sun Y, Luo X, Wang L, et al. Identification of RUNX2 variants associated with cleidocranial dysplasia. Hereditas. 2019;156:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper SC, Flaitz CM, Johnston DA, Lee B, Hecht JT. A natural history of cleidocranial dysplasia. Am J Med Genet. 2001;104(1):1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hordyjewska-Kowalczyk E, Sowinska-Seidler A, Olech EM, Socha M, Glazar R, Kruczek A, et al. Functional analysis of novel RUNX2 mutations identified in patients with cleidocranial dysplasia. Clin Genet. 2019;96(5):429–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quack I, Vonderstrass B, Stock M, Aylsworth AS, Becker A, Brueton L, et al. Mutation analysis of core binding factor A1 in patients with cleidocranial dysplasia. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65(5):1268–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thaweesapphithak S, Saengsin J, Kamolvisit W, Theerapanon T, Porntaveetus T, Shotelersuk V. Cleidocranial dysplasia and novel RUNX2 variants: dental, craniofacial, and osseous manifestations. J Appl Oral Sci. 2022;30: e20220028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gomathi K, Akshaya N, Srinaath N, Moorthi A, Selvamurugan N. Regulation of Runx2 by post-translational modifications in osteoblast differentiation. Life Sci. 2020;245: 117389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ding B, Li C, Xuan K, Liu N, Tang L, Liu Y, et al. The effect of the cleidocranial dysplasia-related novel 1116_1119insC mutation in the RUNX2 gene on the biological function of mesenchymal cells. Eur J Med Genet. 2013;56(4):180–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hojo H. Emerging RUNX2-mediated gene regulatory mechanisms consisting of multi-layered regulatory networks in skeletal development. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(3):2979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thirunavukkarasu K, Mahajan M, McLarren KW, Stifani S, Karsenty G. Two domains unique to osteoblast-specific transcription factor Osf2/Cbfa1 contribute to its transactivation function and its inability to heterodimerize with Cbfbeta. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18(7):4197–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ogawa E, Maruyama M, Kagoshima H, Inuzuka M, Lu J, Satake M, et al. PEBP2/PEA2 represents a family of transcription factors homologous to the products of the Drosophila runt gene and the human AML1 gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90(14):6859–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zaidi SK, Javed A, Choi JY, van Wijnen AJ, Stein JL, Lian JB, Stein GS. A specific targeting signal directs Runx2/Cbfa1 to subnuclear domains and contributes to transactivation of the osteocalcin gene. J Cell Sci. 2001;114(Pt 17):3093–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berkay EG, Elkanova L, Kalayci T, Uludag Alkaya D, Altunoglu U, Cefle K, et al. Skeletal and molecular findings in 51 Cleidocranial dysplasia patients from Turkey. Am J Med Genet A. 2021;185(8):2488–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaruga A, Hordyjewska E, Kandzierski G, Tylzanowski P. Cleidocranial dysplasia and RUNX2-clinical phenotype–genotype correlation. Clin Genet. 2016;90(5):393–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372: n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Intarak N, Tongchairati K, Termteerapornpimol K, Chantarangsu S, Porntaveetus T. Tooth agenesis patterns and variants in PAX9: a systematic review. Jpn Dent Sci Rev. 2023;59:129–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.den Dunnen JT, Dalgleish R, Maglott DR, Hart RK, Greenblatt MS, McGowan-Jordan J, et al. HGVS recommendations for the description of sequence variants: 2016 update. Hum Mutat. 2016;37(6):564–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thaweesapphithak S, Theerapanon T, Rattanapornsompong K, Intarak N, Kanpittaya P, Trachoo V, et al. Functional consequences of C-terminal mutations in RUNX2. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):12202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vimalraj S, Arumugam B, Miranda PJ, Selvamurugan N. Runx2: structure, function, and phosphorylation in osteoblast differentiation. Int J Biol Macromol. 2015;78:202–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Komori T. Roles of Runx2 in skeletal development. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;962:83–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Puppin C, Pellizzari L, Fabbro D, Fogolari F, Tell G, Tessa A, et al. Functional analysis of a novel RUNX2 missense mutation found in a family with cleidocranial dysplasia. J Hum Genet. 2005;50(12):679–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qin X, Jiang Q, Matsuo Y, Kawane T, Komori H, Moriishi T, et al. Cbfb regulates bone development by stabilizing Runx family proteins. J Bone Miner Res. 2015;30(4):706–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Newton AH, Pask AJ. Author Correction: Evolution and expansion of the RUNX2 QA repeat corresponds with the emergence of vertebrate complexity. Commun Biol. 2021;4(1):133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang X, Liu Y, Wang X, Sun X, Zhang C, Zheng S. Analysis of novel RUNX2 mutations in Chinese patients with cleidocranial dysplasia. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(7): e0181653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang Y, Song Y, Zhang C, Chen G, Wang S, Bian Z. Novel RUNX2 frameshift mutations in Chinese patients with cleidocranial dysplasia. Eur J Oral Sci. 2013;121(3 Pt 1):142–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Turner M, Galloway A, Vigorito E. Noncoding RNA and its associated proteins as regulatory elements of the immune system. Nat Immunol. 2014;15(6):484–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dincsoy Bir F, Dinckan N, Guven Y, Bas F, Altunoglu U, Kuvvetli SS, et al. Cleidocranial dysplasia: clinical, endocrinologic and molecular findings in 15 patients from 11 families. Eur J Med Genet. 2017;60(3):163–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kalayci Yigin A, Duz MB, Seven M. Rare findings in cleidocranial dysplasia caused by RUNX mutation. Glob Med Genet. 2022;9(1):23–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material 1: Supplementary Table 1. RUNX2 variants and associated CCD features. Supplementary Table 2. The type of RUNX2 variants associated with CCD. Supplementary Table 3. The in-fame variants of RUNX2 associated with CCD. Supplementary Table 4. The null variants of RUNX2 associated with CCD. Supplementary Table 5. The regions of RUNX2 variants associated with CCD. Supplementary Table 6. In-frame RUNX2 variants associated with CCD. Supplementary Table 7. Null RUNX2 variants associated with CCD.

Supplementary Material 2: Supplementary Table 8. Distribution of different types of variants based on hypoplastic or aplastic clavicles. Supplementary Table 9. Distribution of in-frame variants based on hypoplastic or aplastic clavicles. Supplementary Table 10. Distribution of null variants based on hypoplastic or aplastic clavicles. Supplementary Table 11. Distribution of different types of variants based on delayed fontanelle closure. Supplementary Table 12. Distribution of in-frame variants based on delayed fontanelle closure. Supplementary Table 13. Distribution of null variants based on delayed fontanelle closure. Supplementary Table 14. Distribution of different types of variants based on supernumerary teeth. Supplementary Table 15. Distribution of in-frame variants based on supernumerary teeth. Supplementary Table 16. Distribution of null variants based on supernumerary teeth. Supplementary Table 17. Distribution of different types of variants based on short stature. Supplementary Table 18. Distribution of in-frame variants based on short stature. Supplementary Table 19. Distribution of null variants based on short stature. Supplementary Table 20. Distribution of the different types of variants based on bossing of frontal bone. Supplementary Table 21. Distribution of in-frame variants based on the bossing of frontal bone. Supplementary Table 22. Distribution of null variants based on bossing of frontal bone. Supplementary Table 23. Distribution of the different types of variants based on the Wormian bones. Supplementary Table 24. Distribution of in-frame variants based on Wormian bones. Supplementary Table 25. Distribution of null variants based on Wormian bones. Supplementary Table 26. Distribution of the different types of variants based on macrocephaly. Supplementary Table 27. Distribution of in-frame variants based on macrocephaly. Supplementary Table 28. Distribution of null variants based on macrocephaly. Supplementary Table 29. Distribution of the different types of variants based on metopic groove. Supplementary Table 30. Distribution of in-frame variants based on metopic groove. Supplementary Table 31. Distribution of null variants based on metopic groove. Supplementary Table 32. Distribution of the different types of variants based on hearing loss. Supplementary Table 33. Distribution of in-frame variants based on hearing loss. Supplementary Table 34. Distribution of null variants based on hearing loss. Supplementary Table 35. Distribution of the different types of variants based on hypertelorism. Supplementary Table 36. Distribution of in-frame variants based on hypertelorism. Supplementary Table 37. Distribution of null variants based on hypertelorism. Supplementary Table 38. Distribution of the different types of variants based on abnormal facility in opposing the shoulders. Supplementary Table 39. Distribution of in-frame variants based on abnormal facility in opposing the shoulders. Supplementary Table 40. Distribution of null variants based on abnormal facility in opposing the shoulders. Supplementary Table 41. Distribution of the different types of variants based on the short ribs. Supplementary Table 42. Distribution of in-frame variants based on the short ribs. Supplementary Table 43. Distribution of null variants based on the short ribs. Supplementary Table 44. Distribution of the different types of variants based on lordosis. Supplementary Table 45. Distribution of in-frame variants based on lordosis. Supplementary Table 46. Distribution of null variants based on lordosis. Supplementary Table 47. Distribution of the different types of variants based on pubic bone defects. Supplementary Table 48. Distribution of in-frame variants based on the pubic bone defects. Supplementary Table 49. Distribution of null variants based on pubic bone defects. Supplementary Table 50. Distribution of the different types of variants based on hypoplasia of femoral head. Supplementary Table 51. Distribution of in-frame variants based on the hypoplasia of femoral head. Supplementary Table 52. Distribution of null variants on hypoplasia of femoral head. Supplementary Table 53. Distribution of the different types of variants based on hypoplastic iliac wing. Supplementary Table 54. Distribution of in-frame variants based on hypoplastic iliac wing. Supplementary Table 55. Distribution of null variants based on hypoplastic iliac wing.

Data Availability Statement

Original data generated and analyzed during this study are included in this published article or in the supplementary material.