Abstract

Thyroid eye disease (TED) is the most common symptoms of Graves’ disease. This condition commonly manifests bilaterally and symmetrically. The most prominent symptoms are lid retraction, exophthalmos and diplopia. Rarely, individuals with Graves’ disease show asymmetrical or unilateral eye symptoms. Marine-Lenhart syndrome is a variant of Graves’ disease with occasional hyperactive nodules. A 36-year-old male patient presented to the endocrinology outpatient department at a tertiary care hospital in Muscat, Oman, in 2022 with unilateral eye proptosis and was subsequently found to have Graves’ disease. This case presents a rare Graves’ disease variant with unilateral goiter and orbitopathy.

Keywords: Graves’ Disease, Thyroid Eye Disease, Proptosis, Case Report, Oman

Graves’ disease is an autoimmune condition resulting in thyroid hyperactivity. It is usually associated with high levels of thyroid hormones and the presence of thyrotropin receptor antibodies.

Graves’ orbitopathy is an immune-mediated process that expands fibroblasts in the extraocular muscles within the constrained space of the bony orbits in patients with Graves’ disease.1,2 This condition is usually bilateral and symmetrical. The most dominant symptoms are lid retraction, exophthalmos and diplobia.3 Graves’ orbitopathy can occur without a hyperactive thyroid. The link between these 2 is supported by evidence suggesting an autoimmune link or a direct metabolic effect.4–7 Marine-Lenhart syndrome is a combination of Graves’ disease and hyperfunctioning nodules; this has been described in the literature mostly in case reports.8–10

Marine-Lenhart syndrome, which was first reported in 1911, is characterised by the following criteria: (1) enlarged thyroid with poorly functioning nodules; (2) the nodules demonstrate reduced radioiodine uptake; (3) the nodules are resistant to radioiodine treatment and may require higher doses; (4) after radioiodine treatment, there may be a return of function in the nodule; and (5) the nodule is benign.11 Marine-Lenhart syndrome is described as a subvariant of Graves’ disease.12 The condition has a prevalence of 0.8–2.7% in patients with Graves’ disease.13,14 The association of Marine-Lenhart syndrome with unilateral orbitopathy and Graves’ disease is uncommon. This report describes a case of Marine-Lenhart syndrome with unilateral thyroid orbitopathy and Graves’ disease.

Case Report

A 36-year-old Omani male patient presented to the endocrinology outpatient department of a tertiary care hospital in Muscat, Oman, in 2022 as a referral from the ophthalmology outpatient department with a 13-month history of isolated right eye proptosis and redness. He revealed that during the previous few months, he experienced sweating, non-frequent palpitations, tremors, shortness of breath, diarrhoea, along with generalised weakness. There was no weight loss or decrease in appetite. He had no other symptoms or signs suggestive of systemic disease or other autoimmune diseases and there was no family history of thyroid disease.

On physical examination, he was tachycardic (114 beats/min), had a blood pressure of (120/78), a respiratory rate of 18 breaths/min and oxygen saturation of 99% in ambient air. He was not restless and had no tremors. He was obese with a body mass index of 36 kg/m2. He had right eye proptosis, a normal pupil and erythematous conjunctive with intact intraocular muscles movement and reported double vision. The left eye examination was normal. He had a palpable right thyroid lobe with no palpable nodules. No cervical lymphadenopathy was noted. Cardiovascular examination revealed normal heart sounds with no added sounds or murmurs. The clinical picture was consistent with thyroid-associated orbitopathy.

Laboratory investigations showed a slight increase of C-reactive protein at 8 mg/L (normal range: 0–5 mg/L). The thyroid function test revealed free thyroxine (FT4) of 25.0 pmol/L (normal range: 13.1–21.3 pmol/L) and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) of 0.08 mIU/L (normal range: 0.27–4.20 mIU/L). The anti-thyroid receptor antibody was 2.94 IU/L (normal range: 0–1.75 IU/L).

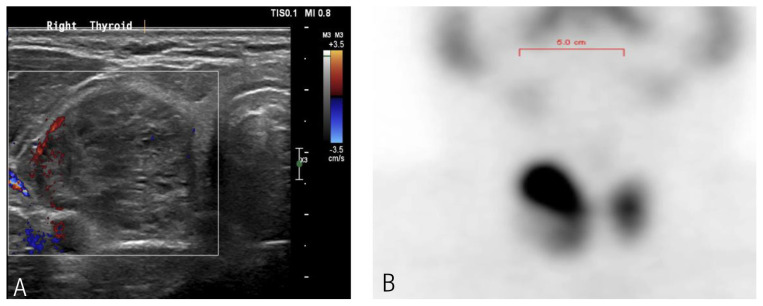

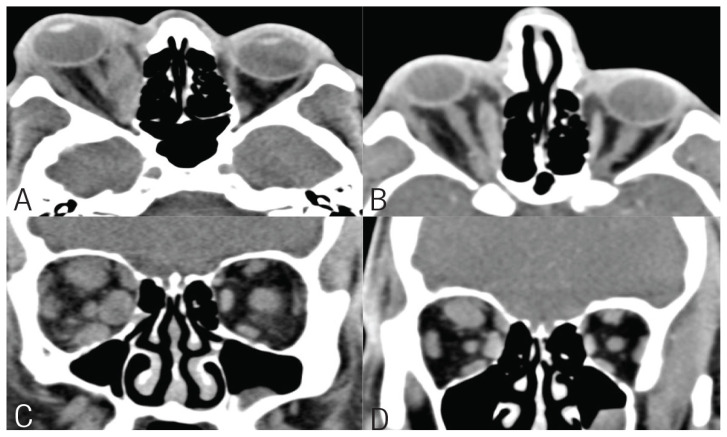

A thyroid ultrasound showed a right thyroid nodule with a TIRADS score of 3, measuring 3.9 cm [Figure 1A]. Fine needle aspiration of the right thyroid nodule showed atypia of undetermined significance/follicular lesion of undetermined significance. A Tc-99 test reported a single hot nodule inside the upper pole of the right thyroid lobe, coinciding with the ultrasound thyroid finding, with high total thyroid radiotracer uptake of 5.5% (normal range: 1–4%) [Figure 1B]. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the orbit without contrast was obtained, which showed severe right proptosis and a normal left orbit [Figure 2A and C] with moderate to severe enlargement of right orbital extraocular muscles predominately involving medial, superior rectus and, to a lesser extent, inferior rectus. Enlarged muscles with relative preservation of tendon resulted in the characteristic “coke bottle” morphology.

Figure 1.

Thyroid (A) ultrasound showing right thyroid nodule and (B) Tc-99 scan showing right hot nodule with increased total tracer uptake.

Figure 2.

Computed tomography scan of orbits showing good response to treatment (A & C) pretreatment and post-treatment (B & D).

He was initially managed with a tapering course of prednisone for a month with no improvements in Graves’ orbitopathy. Subsequently, he received 2 doses of intravenous rituximab (1,000 mg with 2 week intervals). He did not have a significant improvement and was started on a trial of high-dose intravenous (IV) glucocorticoids therapy because teprotumumab was not available in the country. The course consisted of 6 doses of IV methylprednisolone (0.5 g per week for 6 weeks) lead by 6 doses of 0.25 g per week, IV methylprednisolone for 6 weeks with total dosage of 4.5 g. He reported a noticeable improvement in his ophthalmopathy, in particular, his eye redness. Post-treatment CT scan of the orbits without IV contrast showed an interval improvement of the right eye proptosis and right extraocular muscles hypertrophy as well as an interval improvement in the size of the right orbital extraocular muscles [Figure 2B and D]. At the 6-month follow-up after IV rituximab and methylprednisolone, the eye symptoms and signs improved and his double vision resolved. Thyroid function test normalised (FT4 = 17.8, TSH = 1.81) and the TSH receptor antibodies became negative. Additionally, the patient was directed to a thyroid surgeon for total thyroidectomy for histopathological confirmation and definitive treatment.

Patient consent for publication purposes was obtained.

Discussion

Graves’ disease is an autoimmune illness characterised by elevated levels of FT4 and triiodothyronine and a diffuse goiter.14 Thyroid nodules can accompany Graves’ disease; while most are hypoactive, a small percentage can be hyperactive.8 Consequently, patients may have thyrotoxicosis because of each Graves’ disease and hyperfunctioning nodular goiter or a single toxic nodule. This form of Graves’ disease is known as Marine-Lenhart syndrome.9,10,15 There are no clear criteria for the diagnosis. In terms of treatment, anti-thyroid medications were effective in treating 1 case of Marine-Lenhart syndrome with a solitary toxic nodule.3 In Japan, radioactive iodine (RAI) therapy was used to treat 18 patients, however there was a high prevalence of hypothyroidism due to the increase in RAI uptake.14

Another symptom of Graves’ disease is Graves’ orbitopathy, also known as thyroid-eye disease. An individual suffering from Graves’ orbitopathy may experience a number of physical and mental disabilities as well as loss of vision. The symptoms of which can start at the same time as the symptoms of hyperthyroidism.8 Though, Graves’ orbitopathy can develop even if the thyroid function is normal.

The disease is typically accompanied by exophthalmos, lid retraction and diplopia, and appears bilaterally and symmetrically.9 There are, however, some patients who show symptoms in an asymmetric or unilateral manner. There is a limited amount of literature available regarding actual unilateral Graves’ orbitopathy, and the information that does exist is quite diverse. Despite this, there is no definitive explanation or data available for this manifestation. It has been reported that a small percentage of patients, ranging from 9–15%, experience pure unilateral Graves’ orbitopathy.16–18 According to a recent cross-sectional study conducted by the European Group on Graves’ orbitopathy (EUGOGO), the severity and activity of Graves’ orbitopathy can be indicated by its asymmetry. This finding is important as it highlights the need for proper management and monitoring of the disease.19 The current patient was assessed and found to have moderate to severe thyroid eye disease based on EUGOGO classification for disease activity and severity.

The autoimmune process that causes the growth of the orbital contents in an asymmetric and unilateral Graves’ orbitopathy appears to be comparable to those that cause bilateral illness in terms of pathogenesis. However, structural variations, mechanical, circulatory and inflammatory variables may also play roles in the emergence of asymmetric disease. Soroudi et al. theorised that the asymmetrical expansion of orbital contents may be caused by the uneven distribution of antigen or inflammatory processes, albeit this was not investigated in any studies to date.16 Furthermore, there have been suggestions that there could be variances in structure that lead to distinct blood circulation or lymphatic drainage patterns.15 It has also been hypothesised that unilateral triggers such as infections or variances in the ability for adipogenesis may be caused by the flexibility of the orbital septum or other local variables.19 A previous study explored the effects of sleeping positions on asymmetric Graves’ orbitopathy, but there was no significant correlation.20 The precise mechanisms continue to be a mystery despite prior postulations. Therefore, more research is required to better understand asymmetric Graves’ orbitopathy and reveal the causes of asymmetry. This might offer additional insights into Graves’ orbitopathy development and management. Finally, a limitation of this case in availability of tissue diagnosis and repeat uptake scan after treatment.

Conclusion

Physicians should be aware of the potential link between unilateral orbitopathy and Graves’ disease, despite the lack of a robust pathophysiology explanation supported by strong evidence. Thyrotoxicosis should be treated along with orbitopathy as part of the overall therapy plan. Marine-Lenhart syndrome is a distinct variant of Graves’ disease that has been recognised by medical professionals, albeit it is quite rare. Moreover, it is discovered incidentally and usually does not impact the treatment.

Footnotes

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION: AF managed the patient and follow-up. ZSS and OSS collected the data and provided the images. AA and AO drafted the manuscript. FB and SKR edited the manuscript and arranged the references. AA and AO revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Kashkouli MB, Kaghazkanani R, Heidari I, Ketabi N, Jam S, Azarnia S, et al. Bilateral versus unilateral thyroid eye disease. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2011;59:363–6. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.83612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strianese D, Piscopo R, Elefante A, Napoli M, Comune C, Baronissi I, et al. Unilateral proptosis in thyroid eye disease with subsequent contralateral involvement: retrospective follow-up study. BMC Ophthalmol. 2013;13:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-13-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braga-Basaria M, Basaria S. Marine-Lenhart Syndrome. Thyroid. 2003;13:991. doi: 10.1089/105072503322511418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Panagiotou G, Perros P. Asymmetric Graves’ Orbitopathy. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2020;11:611845. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2020.611845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gontarz-Nowak K, Szychlińska M, Matuszewski W, Stefanowicz-Rutkowska M, Bandurska-Stankiewicz E. Current Knowledge on Graves’ Orbitopathy. J Clin Med. 2020;10:16. doi: 10.3390/jcm10010016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diana T, Ponto KA, Kahaly GJ. Thyrotropin receptor antibodies and Graves’ orbitopathy. J Endocrinol Invest. 2021;44:703–12. doi: 10.1007/s40618-020-01380-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bartalena L, Tanda ML. Current concepts regarding Graves’ orbitopathy. J Intern Med. 2022;292:692–716. doi: 10.1111/joim.13524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bartalena L, Tanda ML. Graves’ Ophthalmopathy. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:994–1001. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0806317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chin YH, Ng CH, Lee MH, Koh JWH, Kiew J, Yang SP, et al. Prevalence of thyroid eye disease in Graves’ disease: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2020;93:363–74. doi: 10.1111/cen.14296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wiersinga WM, Smit T, van der Gaag R, Mourits M, Koorneef L. Clinical presentation of Graves’s ophthalmopathy. Ophthalmic Res. 1989;21:73–82. doi: 10.1159/000266782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harisankar CN, Preethi GR, Chungath BB. Hybrid SPECT/CT evaluation of Marine-Lenhart syndrome. Clin Nucl. 2013;38:e89–90. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e31825ae860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neuman D, Kuker R, Vendrame F. Marine-Lenhart Syndrome: Case Report, Diagnosis, and management. Case Rep Endocrinol. 2018;2018:3268010. doi: 10.1155/2018/3268010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marine D, Lenhart CH. Pathological anatomy of exophthalmic goiter: the anatomical and physiological relations of the gland to the disease; the treatment. Arch Intern Med. 1911;8:265–316. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1911.00060090002001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Danno H, Nishihara E, Kousaka K, Nakamura T, Kasahara T, Kudo T, et al. Prevalence and Treatment Outcomes of Marine-Lenhart Syndrome in Japan. Eur Thyroid J. 2021;10:461–7. doi: 10.1159/000510312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bartalena L. Graves’ orbitopathy: imperfect treatments for a rare disease. Eur Thyroid J. 2013;2:259–69. doi: 10.1159/000356042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soroudi AE, Goldberg RA, McCann JD. Prevalence of asymmetric exophthalmos in Graves orbitopathy. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;20:224–5. doi: 10.1097/01.IOP.0000124675.80763.5A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cakir M. Diagnosis of Marine-Lenhart syndrome. Thyroid. 2004;14:555. doi: 10.1089/1050725041516995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Charkes ND. Graves’ disease with functioning nodules (Marine-Lenhart syndrome) J Nucl Med. 1972;13:885–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perros P, Žarković MP, Panagiotou GC, Azzolini C, Ayvaz G, Baldeschi L, et al. Asymmetry indicates more severe and active disease in Graves’ orbitopathy: results from a prospective cross-sectional multicentre study. J Endocrinol Invest. 2020;43:1717–22. doi: 10.1007/s40618-020-01258-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wiersinga WM, Bleumink M, Saeed P, Baldeschi L, Prummel MF. Is sleeping position related to asymmetry in bilateral Graves’ ophthalmopathy? Thyroid. 2008;18:541–4. doi: 10.1089/thy.2007.0302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]