Abstract

Introduction

Cell-free DNA (cfDNA) is expected to contribute to the decision for treatment and prediction of effects with minimally invasion. We investigated the correlation between gene mutations before and after lenvatinib (LEN) treatment and its effectiveness, in order to find advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients who would benefit greatly from the therapy.

Methods

We analyzed cfDNA before and 6–8 weeks after the start of treatment in 20 advanced HCC patients who started LEN. A next-generation sequencer was used for CTNNB1 and TP53. Concerning TERT promoter, −124C>T and −146C>T mutations are researched using digital PCR. In addition, we examined liver tumor biopsy tissues by the same method. Computerized tomography evaluation was performed at 6–8 weeks and 3–4 months to assess the efficacy.

Results

Frequencies of TERT promoter, CTNNB1, and TP53 mutations in pretreatment cfDNA were 45%, 65%, and 65%, but 53%, 41%, and 47% in HCC tissues, respectively. There were no clear correlations between these gene mutations and the disease-suppressing effect or progression-free survival. Overall, there were many cases showing a decrease in mutations after LEN treatment. Integrating the reduction of CTNNB1 and TP53 genetic mutations increased the potential for disease suppression.

Conclusion

This study suggests that analysis of cfDNA in advanced HCC patients may be useful for identifying LEN responders and determining therapeutic efficacy. Furthermore, it has potential for selecting responders for other molecular-targeted drugs.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, Cell-free DNA, Next-generation sequencer, Lenvatinib, Liver tumor biopsy, CTNNB1, TP53, Telomerase reverse transcriptase promoter

Introduction

Liver cancer is increasing and is the fourth leading cause of cancer death worldwide with 865,269 new cases in 2022, and about 90% of these cases are hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [1]. The annual HCC incidence is 1–6% in patients with cirrhosis [2]. Treatment of HCC is generally selected based on Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging. Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization therapy is mainly selected in stage B, and systemic therapy, including molecular-targeted drugs, is standard in stage C [3]. In recent years, it has been reported that treatment with molecular-targeted drugs is more effective for stage B patients with more than 7 tumors and a tumor diameter greater than 7 cm [4, 5]. Atezolizumab and bevacizumab (ATZ/BV) were approved in Japan from September 2020, and the range of chemical treatment for HCC is expanding [6, 7]. Lenvatinib (LEN) is a multi-kinase inhibitor targeting receptor tyrosine kinase (KIT) and rearranged during transfection, as well as vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1–3, fibroblast growth factor receptor 1–4 and platelet-derived growth factor receptor A [8, 9]. The efficacy for patients with unresectable HCC was shown in the REFLECT trial. The inhibition of fibroblast growth factor receptor 4 by LEN is thought to be an important factor in its antitumor effect [10]. While ATZ/BV is the mainstream treatment, it is expected that LEN treatment will also be important for nonresponders of ATZ/BV. However, markers that can predict the therapeutic effect have not been found. One of the reasons for this might be diversity of the genetic background. It is known that HCC gene mutations are diverse and that the population of cancer nodules is heterogeneous [11–13]. Therefore, genetic analysis of some tissues of cancer nodules does not capture the entire information of HCC. According to previous reviews [12], Telomerase reverse transcriptase promoter (TERT promoter) mutations are among the most frequent HCC gene mutations (54–60%). Mutations in the tumor suppressor gene tumor protein 53 (TP53) are present in 12–48% of HCC patients. Homozygous deletions of CDKN2A (cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A) mutations (2–12%) and RB1 (RB transcriptional corepressor 1) mutations (3–8%) are also present. Genetic variants involved in the WNT/β-catenin pathway are important, with 11–37% of activating mutations in catenin beta-1 (CTNNB1), encoding β-catenin, and 5–15% inactivating mutations in AXIN1 (axis inhibition protein 1). Inactivating mutations in ARID1A (AT-rich interaction domain 1A) in 4–17% and ARID2 (AT-rich interaction domain 2) in 3–18% may be recognized as epigenetic modifiers. Inactivation of Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (KEAP1) is also found in 2–8% of cases as an oxidative stress pathway. Another reason may be that the diagnosis of HCC is often made by imaging tests since liver tumor biopsy is a highly invasive test with the risk of bleeding and organ damage. The origin of cancer is the accumulation of various gene mutations, and it is important to consider treatment based on these gene mutations, but it has not yet been used as an effective factor in clinical practice. Recently, attention has been focused on the analysis of gene mutations in cell-free DNA (cfDNA) in blood. It has been found that gene mutations in cancer tissues and samples can be collected safely with minimal invasion [14, 15]. It is expected that such detailed analysis will contribute to the determination of therapeutic agents and prediction of the effects. TERT promoter, TP53, and CTNNB1 mutations were reported frequently in previous studies [16–19]. In addition, Fujii et al. [20] reported that somatic alterations could be detected in most advanced HCC patients by circulating tumor DNA profiling during LEN treatment and are a useful marker of disease progression. Based on these previous reports, we examined whether it is possible to predict and select cases in which LEN is effective by analyzing these three representative mutations using next-generation sequencing (NGS) and digital polymerase chain reaction (digital PCR).

Materials and Methods

Patients and Treatment Regimens

From January 2020 to January 2022, 20 advanced HCC patients started LEN (Lenvima®; Eisai Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) treatment at Tohoku University Hospital. Patients with unresectable HCC with BCLC B or C who consented to have their blood test specimens at the start of treatment, 6–8 weeks, and 3–4 months after the start of treatment and their liver tumor biopsy specimens used in the study were included. The exception was 1 patient with BCLC A, whose HCC recurred very quickly after the surgery for HCC. This patient was promptly started on LEN because it was anticipated that he would likely require anticancer therapy later in life. Two patients chose treatment, taking into account social factors such as cognitive impairment or the absence of kinship guardianship. The patients weighing ≥60 kg initially started at an elevated dose of 12 mg once daily, while others started at 8 mg as the standard dose. If any adverse events occurred, treatment was discontinued or the LEN dose was reduced. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Tohoku University Hospital (2019-1-414) and conducted in accordance with the principals of the Declaration of Helsinki (Fortaleza revision, 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from patients prior to their participation in the study. Patients were evaluated for cirrhosis and HCC status according to several classifications before treatment. Specifically, the Child-Pugh classification, BCLC staging, and modified albumin-bilirubin grade (mALBI grade), which is a more refined version of the albumin-bilirubin (ALBI) score [21].

CfDNA and Liver Tumor Tissue Samples

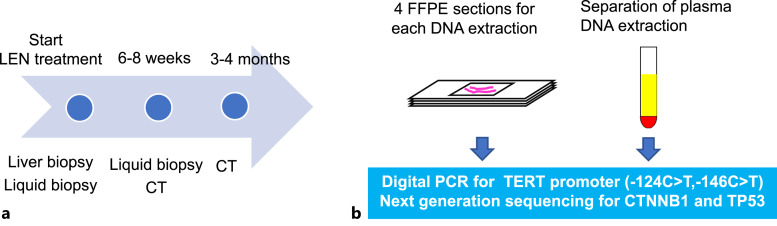

Liver biopsy and laboratory assessments were performed before the administration of LEN. Liquid biopsy was performed before the start of LEN treatment and 6–8 weeks later using a collection tube with heparin sodium. Evaluation with computerized tomography scan was performed 3–4 months later (Fig. 1a). The objective response was evaluated by the modified response evaluation criteria in solid tumors [11, 22, 23]. Plasma was separated in a centrifuge at 3,000 rpm for 10 min. Samples were kept at −30°C in a freezer (Fig. 1b). We chose the silica membrane method with NucleoSnap cfDNA (TaKaRa Bio., Shiga, Japan). We performed liver tumor biopsy before LEN treatment, and 4 formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue sections of 10 μm thickness for each patient were used for DNA extraction using QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany).

Fig. 1.

Time schedule and the process of DNA extraction to NGS or digital PCR. a Liver tumor biopsy and liquid biopsy were performed at the start of LEN treatment. 6–8 weeks later, liquid biopsy and computerized tomography evaluation were performed. 3–4 months later, final imaging evaluation was performed. Because patients 2 and 16 had discontinued the treatment, the final imaging evaluation was performed at 6–8 weeks. b Blood samples centrifuged at 3,000 × rpm for 10 min, and only the plasma was aliquoted into collection vials for DNA extraction. For liver tumors, DNA was extracted from four 10 µm FFPE sections. TERT promoter was subjected to digital PCR, while CTNNB1 and TP53 were analyzed by NGS.

Analysis of TERT Promoter with Digital PCR

It seemed difficult to analyze the TERT promoter with NGS because of the high guanine-cytosine (GC) content (>80%). It easily forms a secondary hairpin structure, resulting in poor amplification [24]. Therefore, we used ABI QuantStudio 3D (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) to run the digital PCR [25]. We ordered a dedicated master mix and assay in advance (TaqMan Liquid Biopsy dPCR Assay), then performed digital PCR on −124C>T and −146C>T mutations, which are the most common and well-known ones [16, 26, 27].

Analysis of CTNNB1 and TP53 with Next-Generation Sequencing

We chose Ion Torrent Next-Generation Sequencing Technology (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for analysis of the CTNNB1 and TP53 mutations. Specifically, according to the protocol of the AmpliSeq library, PCR was performed to amplify the required region first, the ligation next, and purification was performed using Agencourt AMPure XP Reagent. After that, we adjusted templates using Ion One Touch 2 system and Ion One Touch ES. Finally, we ran NGS on the Ion Personal Genome Machine (Ion PGM) system. Online supplementary Table 1 (for all online suppl. material, see https://doi.org/10.1159/000540438) shows information on amplicon regions amplified by NGS. For confirmation, we used the Integrative Genomics Viewer 2.12.3 to visualize the genomic data [28].

Definitions

Since genetic mutations with variant allele frequency (VAF) ≥ 50% are considered germline mutations and the detection limit of VAF in gene panel tests is 0.03% [29–31], we designated an allele frequency of 0.03%–50% as valid. Following a previous report [20], the means of VAFs of somatic mutated genes in each patient were defined as VAFmean. In accordance with this previous report, we defined VAFmean in this study as the VAF of CTNNB1 and TP53 divided by the number of mutated sites on the chromosome. The average of the VAFmean of each of CTNNB1 and TP53 was further calculated to obtain the total VAFmean. If no mutations were detected at any time point, they were excluded without counting. In our study, we examined the VAFmean for CTNNB1 and TP53.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using JMP Pro 16.0.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Progression-free survival (PFS) was estimated using Kaplan-Meier methods, and differences among subgroups were evaluated using the log-rank test. Cox regression analysis was performed for potential biomarkers to predict PFS. All comparisons were considered significant if the p value was <0.05.

Result

Clinical Characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the clinical characteristics of the patients. As their background of liver disease, 1 patient had HBV infection, 5 patients had HCV infection, and 14 patients had other diseases including nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, alcoholic liver disease, and Fontan-associated liver disease. The median age was 73 years. Concerning BCLC stage of HCC, stage B was the most common with 11 patients. When the liver function was evaluated with mALBI grade, 8, 8, and 4 patients showed grade 1, 2a, and 2b, respectively. Seventeen patients were previously treated for any type of HCC.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the patients

| Variable | LEN (n = 20) |

|---|---|

| Age | 73 (65–79) |

| Sex (male:female) | 16:4 |

| Etiology (HBV:HCV:others) | 1:5:14 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 9/20 (45.0) |

| Child-Pugh (A:B:C) | 19:1:0 |

| BCLC stage (A:B:C) | 3:11:6 |

| mALBI grade (1:2a:2b:3) | 8:8:4:0 |

| AFP, ng/mL | 22.1 (9.8–200.0) |

| DCP, AU/mL | 208.0 (33.0–3,865.5) |

| Lymph node metastasis, n (%) | 2/20 (10.0) |

| Distant or portal vein invasion, n (%) | 5/20 (25.0) |

| Maximum tumor size, mm | 37.0 (18.0–66.5) |

| Tumor numbera (1:2:3:4≦) | 5:4:0:10 |

| Differentiation (poor-moderate:well:obscure) | 14:4:2 |

| Past treatment, n (%) | |

| RFA | 7/20 (35.0) |

| TACE | 9/20 (45.0) |

| Operation | 10/20 (50.0) |

| Chemotherapyb | 4/20 (20.0) |

| Radiation | 4/20 (20.0) |

Numbers in parentheses are interquartile range.

HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; BCLC stage, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage; mALBI grade, modified albumin-bilirubin grade; AFP, α-fetoprotein; DCP, des-γ-carboxy prothrombin; RFA, radiofrequency ablation; TACE, transcatheter arterial chemoembolization; SOR, sorafenib; REG, regorafenib; ATZ/BV, atezolizumab and bevacizumab.

aPatient 12 had only lymph node metastasis.

bPatient 7, patient 9, patient 17, and patient 20 experienced hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy (HAIC), SOR and REG, investigational drug, and ATZ/BV, respectively.

Genomic Profiling of Tissues and cfDNA

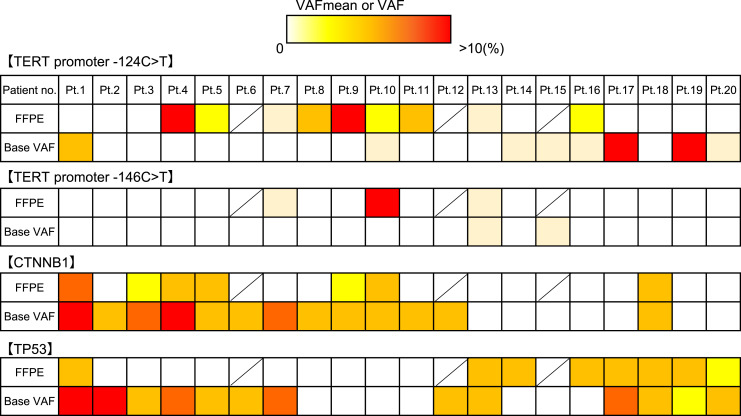

The mutations (124C>T and 146C>T) of the TERT promoter were found in HCC tissue of 53% and 18% and in cfDNA of 40% and 10%, respectively. The mutation frequencies of CTNNB1 and TP53 were 41% and 47% in HCC tissue samples and 65% for both genes in cfDNA. In CTNNB1 and TP53 mutations, 99 single nucleotide polymorphisms, 13 insertions, 2 deletions, 5 complexes, and 1 multiple nucleotide polymorphism were observed. Further, 158 single nucleotide polymorphisms, 3 insertions, and 11 complexes were shown in cfDNA. The locations of those mutations did not correspond between HCC tissues and cfDNAs (Fig. 2). The relationship between maximum tumor size and tumor markers with the presence of each gene mutation is shown in Table 2. No significant correlations were observed.

Fig. 2.

Mutation motif between tissue and cfDNA. VAFmean in FFPE at the top and the baseline cfDNA at the bottom for the three genes were compared. For the TERT promoter, VAFs of −124C>T and −146C>T are represented. Patients 6, 12, and 15 had not undergone liver tumor biopsy.

Table 2.

Correlation of tumor size and tumor markers with VAFmean

| Maximum tumor size, mm | p value | AFP, ng/mL | p value | DCP, AU/mL | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tissues (n = 17) | |||||||

| TERT promoter mutation | |||||||

| (+) | 33.0 (25.0–66.5) | 0.2546 | 12.0 (2.6–50.4) | 0.5138 | 91.0 (37.0–3,865.5) | 0.9311 | |

| (−) | 55.0 (29.3–82.3) | 126.4 (36.7–1,943.8) | 1,440.5 (182.8–8,234.8) | ||||

| CTNNB1 VAFmean | |||||||

| High | 33.0 (13.0–71.0) | 0.2320 | 27.2 (12.0–83.8) | 0.3213 | 2,039.0 (44.0–4,338.0) | 0.3756 | |

| Low | 55.0 (29.3–86.0) | 40.5 (1.9–16,023.8) | 208.0 (51.0–12,781.5) | ||||

| TP53 VAFmean | |||||||

| High | 55.0 (30.8–75.5) | 0.3387 | 69.5 (1.6–210.5) | 0.5011 | 662.0 (103.8–8,234.8) | 0.8842 | |

| Low | 33.0 (24.0–77.0) | 16.9 (10.6–1,300.9) | 91.0 (51.0–3,865.5) | ||||

| cfDNA (n = 20) | |||||||

| TERT promoter mutation | |||||||

| (+) | 42.0 (13.0–61.0) | 0.6300 | 65.1 (1.7–489.5) | 0.5308 | 325.0 (24.5–3,996.5) | 0.7209 | |

| (−) | 33.0 (23.0–80.0) | 16.9 (11.4–221.0) | 91.0 (36.0–4,338.0) | ||||

| CTNNB1 VAFmean | |||||||

| High | 30.0 (13.0–90.2) | 0.2355 | 16.9 (11.0–152.4) | 0.6859 | 91.0 (40.0–3,865.5) | 0.9831 | |

| Low | 50.0 (27.0–62.0) | 65.1 (1.4–800.0) | 325.0 (19.0–7,151.0) | ||||

| TP53 VAFmean | |||||||

| High | 42.0 (19.0–81.5) | 0.2668 | 65.1 (11.7–1,369.5) | 0.3857 | 842.0 (25.5–7,873.5) | 0.2277 | |

| Low | 30.0 (13.0–50.0) | 9.1 (2.0–83.8) | 91.0 (44.0–482.0) | ||||

Numbers in parentheses are interquartile range.

VAFmean, variant allele frequency mean; AFP, α-fetoprotein; DCP, des-γ-carboxy prothrombin.

Correlation of TERT Promoter Mutations, VAFmeans, and Response in Computerized Tomography Imaging

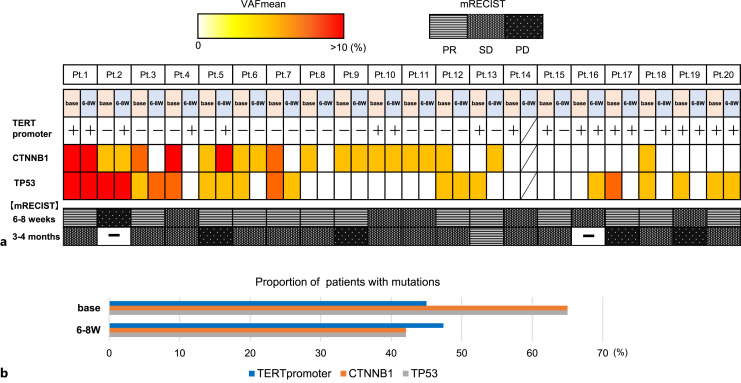

The percentages of each gene mutations and the changes in the objective imaging assessment in all patients are shown in Figure 3a. At the start of LEN and after 6–8 weeks, the redder VAFmean of CTNNB1 and TP53 indicates the higher value. It has been argued previously that CTNNB1 and TP53 are generally exclusive [32, 33], but our results showed that 45% (9/20) of patients had both mutations. Position 124 and/or 146 mutations of TERT promoter were represented as positive or negative. After the start of treatment, the mutation disappeared in 2 patients and became positive in 4 patients. The VAFmean of CTNNB1 and TP53 decreased after LEN in 11 and 9 patients, respectively. Figure 3b depicts the percentage of patients with mutations before and after the start of LEN treatment for each gene. The bottom part of Figure 3a represents modified response evaluation criteria in solid tumor results at 6–8 weeks and 3–4 months after the start of treatment. Because patient 14 was shifted to radiotherapy in the middle of the treatment, the latter half of the data were missing.

Fig. 3.

Sequential analysis of VAFmean. a The heatmap of each gene mutations at baseline and 6–8 weeks after treatment initiation. Position 124 and/or 146 mutations of TERT promoter were represented by positive or negative. Patient 14 discontinued treatment. The bottom row shows mRECIST evaluation. b The bar graph indicates the percentage of patients with genetic mutations at each time point.

Comparison with Tumor Markers

We performed Cox regression analysis for potential clinical biomarkers of prognostic factors to predict PFS. We performed univariate analysis on the tumor status, tumor markers, and the presence or absence and changes in each genetic mutation in addition to basic information such as age and gender. No significant differences were found for all factors (Table 3).

Table 3.

Result of Cox regression analysis for prognostic factors

| p value (univariate analysis) | |

|---|---|

| Sex | 0.3606 |

| Age | 0.0732 |

| Etiology (HBV:HCV:others) | 0.5276 |

| HBV past infection | 0.6100 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.5989 |

| mALBI grade | 0.1437 |

| AFP | 0.3794 |

| DCP | 0.3764 |

| Maximum tumor size | 0.1972 |

| Tumor number | 0.2529 |

| Lymph metastasis | 0.6245 |

| Distant/portal metastasis | 0.1181 |

| Mutations at baseline | |

| TERT promoter | 0.7482 |

| VAFmean at baseline | |

| CTNNB1 | 0.7546 |

| TP53 | 0.1789 |

| Disappearance of mutations | |

| TERT promoter | 0.2398 |

| VAFmean reduction | |

| CTNNB1 | 0.3787 |

| TP53 | 0.6265 |

HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; mALBI grade, modified ALBI grade; AFP, α-fetoprotein; DCP, des-γ-carboxy prothrombin; VAFmean, variant allele frequency mean.

The association between mutation loss or VAFmean change rate and treatment image assessment was investigated (Table 4). Cases with a VAFmean decrease of 1.0% or more were defined as cases with a decreased VAFmean. The change of TERT promoter was evaluated by whether it disappeared after treatment. Cases with a partial response or stable disease were referred to as treatment response group and progressive disease (PD) as nonresponse group in final evaluations. The sensitivity and specificity of the existing tumor markers α-fetoprotein (AFP) and des-γ-carboxy prothrombin (DCP), as well as the loss of a mutation or decrease in the VAFmean, to predict the treatment response group were examined. The percentage of the treatment response group among the cases with loss of mutation or the reduction of a marker and VAFmean is shown as the effectivity predictive value. The proportion of the treatment response group among the cases with no disappearance or decrease in VAFmean was expressed as the non-effectivity predictive value. The specificity and sensitivity for loss of TERT promoter mutation to predict treatment response group were 0.8 and 0.36. The specificity and sensitivity of the VAFmean reduction in CTNNB1 were 0.6 and 0.64. For TP53, they were 0.6 and 0.5. The reduction in the total VAFmean calculated from the mean of the VAFmean of CTNNB1 and TP53 was better than that of CTNNB1 and TP53 individually in terms of sensitivity, which were evaluated with an effective predictive value of the treatment response and a non-effective predictive value. For comparison, the relationship between changes in the existing tumor markers AFP and DCP and image assessment was also evaluated. The specificity and sensitivity of AFP were 0.2 and 0.57, respectively, and those of DCP were 0.4 and 0.36. In a comparison of the predictive ability of tumor markers and gene mutation loss or reduced mutation rate to predict treatment response groups, the specificity was higher for gene mutation changes than for the existing tumor markers. Similarly, the predictive ability of the treatment response by the TERT promoter loss, CTNNB1, and TP53 mutation reduction was better than that of the tumor markers.

Table 4.

Diagnostic utility of VAFmean and tumor markers

| mRECIST | Diagnostic utility | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SD/PR | PD | sensitivity | specificity | effectivity | non-effectivity | |

| predictive value | predictive value | |||||

| VAFmean | ||||||

| TERT promoter | ||||||

| Non-disappearance | 4 | 9 | 0.36 | 0.8 | 0.83 | 0.31 |

| Disappearance | 1 | 5 | ||||

| CTNNB1 | ||||||

| Non-decrease | 3 | 5 | 0.64 | 0.6 | 0.82 | 0.38 |

| Decrease | 2 | 9 | ||||

| TP53 | ||||||

| Non-decrease | 3 | 7 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.78 | 0.3 |

| Decrease | 2 | 7 | ||||

| Total | ||||||

| Non-decrease | 3 | 1 | 0.93 | 0.6 | 0.87 | 0.75 |

| Decrease | 2 | 13 | ||||

| AFP | ||||||

| Non-decrease | 1 | 6 | 0.57 | 0.2 | 0.67 | 0.14 |

| Decrease | 4 | 8 | ||||

| DCP | ||||||

| Non-decrease | 2 | 9 | 0.36 | 0.4 | 0.63 | 0.18 |

| Decrease | 3 | 5 | ||||

mRECIST, modified response evaluation criteria in solid tumors; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease; VAFmean, variant allele frequency mean; AFP, α-fetoprotein; DCP, des-γ-carboxy prothrombin.

Correlation of TERT Promoter Mutation Loss, VAFmean Change, and PFS

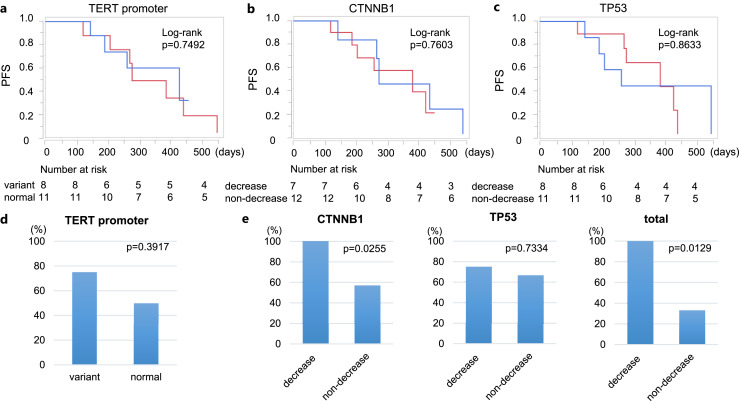

We drew the Kaplan-Meier curve to estimate PFS according to the presence of −124C>T and/or −146C>T mutations in the TERT promoter at baseline (Fig. 4a), but there were no significant differences. Also, we could not find a clear correlation with PFS due to the VAFmean reduction of CTNNB1 (Fig. 4b) and TP53 (Fig. 4c).

Fig. 4.

Analysis of PFS and disease control rate. a The relation with tumor progression and the presence of mutations in pretreatment cfDNA in the TERT promoter analyzed with Kaplan-Meier analysis. The blue line indicates patients with mutations and the red line indicates those without. The relation with tumor progression and VAFmean reduction in CTNNB1 (b) and TP53 (c). The blue lines indicate patients whose VAFmean was decreased; the red lines indicate whose VAFmean was not decreased. d The disease control rates due to the presence of base mutations in the TERT promoter. e Comparison of disease control rate in patients with VAFmean reduction and in those without.

Response to LEN Treatment according to Specific Mutations

The disease control rates were compared according to the presence or the change of gene mutations. Patients who showed no genetic mutation both before and after treatment were excluded as unanalyzable. There were no differences in disease control rates due to the presence of base mutations in the TERT promoter (Fig. 4d). In CTNNB1 and TP53, we compared the rate of disease control in cases with and without VAFmean reduction after treatment, grouping the imaging evaluation into PD and others (Fig. 4e). For CTNNB1, disease control rate was higher in patients with a decrease in the VAFmean (p = 0.0255). TP53 analysis showed no clear difference. When the VAFmean of CTNNB1 and TP53 mutations were aggregated, the disease control rate was higher in patients with a reduced VAFmean (p = 0.0129).

Discussion

The biomarker that can predict the favorable effects of LEN in advanced HCC treatment before or shortly after initiation is still unknown. In this study, in cases where the frequency of CTNNB1 mutations decreased early after treatment initiation, the possibility of achieving disease control was suggested. Additionally, when considering the total average frequency of mutations in CTNNB1 and TP53, cases with decreased mutation frequencies showed further enhanced disease control effects. These results highlight aspects not previously demonstrated in previous studies and represent data that can contribute to the development of future biomarker research.

Recently, it has become known that the genetic information of cfDNA, which can be obtained by liquid biopsy, reflects the genetic profiling of malignant tumors [14, 34]. This technology has recently enabled the analysis of genetic mutations in tumors for liver cancer without undergoing the risk of liver tumor biopsy [15, 19, 35]. In this study, although the detection rate of mutations was similar to previously reported percentages in tumor samples and cfDNA, the specific location of each gene mutation before LEN treatment initiation was not consistent except in a few cases of the TERT promoter. Previous reports have claimed high homology between cfDNA and genetic mutations in liver tumors [35, 36]. However, other reports described that genetic mutations in cfDNA are not sensitive enough. In these reports, it was considered that intratumoral heterogeneity may be the underlying cause for the discrepancy in mutational status between plasma and tumor tissues [16, 19]. Even though we excluded them based on the percentage of mutations, we cannot be certain that all cfDNA mutations are derived from tumor cells since germline mutations can also be detected in plasma. In addition to the reasons mentioned above, it is necessary to improve the accuracy because there is a possibility of contamination of cfDNA from blood cells and other sites. Further accumulation and analysis of cases are needed.

Previous studies have reported that cases with decreased VAF in some genes after treatment initiation responded to treatment and, conversely, cases with increased VAF in some genes had PD [20, 35]. However, no single specific genetic mutation has yet been found to serve as a biomarker for determining therapeutic efficacy. In this report, there was no evidence of prolonged PFS or disease suppression for each of the three representative genetic mutations in HCC. However, as in previous reports, cases in which the mean of all gene mutations decreased after treatment tended to respond to treatment. Individually considered, patient 9 experienced sorafenib and regorafenib, while patient 20 used ATZ/BV before LEN treatment in our study. There were no features in the genetic profiling of these patients.

In other cancers, tyrosine kinase inhibitor has been reported to increase the gene mutation rates by inhibiting DNA repair or damaging DNA, leading to resistance to treatment [37, 38]. For HCC, sorafenib and LEN induced oxidative stress, which is thought to be one of the antitumor mechanisms [39]. From these facts, it can be predicted that an increase in genetic mutations caused by reactive oxygen species and oxidative stress would either lead to disease suppression or to treatment resistance. In fact, as previously reported, HCC tended to show disease suppression in cases where the mutation rate decreased after LEN treatment. This is because less cfDNA is expected to leak from the tumor into the bloodstream. Some kind of selective control mechanism may be at work, blocking the pathways or factors that cause genetic mutations. In this study, the mutation rate of TERT promoter increased after treatment. We investigated the major genetic variants 124C>T and 146C>T, and some previous studies have shown that both mutations activate TERT promoter activity and TERT gene transcription [40]. On the other hand, TERT promoter has been reported to be mutated even in the absence of overt malignant lesions with the progression of liver fibrosis [41, 42]. 15 of the 20 patients in this study had a FIB-4 index of 3.25 or higher, and it was conceivable that they might have been affected by changes in their cirrhotic status.

Recently, β-catenin pathway activation represented by CTNNB1 mutation was found to be associated with an immune-cold microenvironment and resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors in HCC patients [43, 44]. In our study, there were no differences in the effectiveness of LEN treatment from CTNNB1 mutation status at baseline. This result was the same as that in a report from Japan last year [20]. In HCC with Wnt/β-catenin pathway mutations, favorable effects of LEN treatment after immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment have been reported [45]. In this study, patients with reduced CTNNB1 gene mutations after treatment showed disease suppression. It is expected that further analysis will be able to discover cases in which LEN is most effective.

From multiple past reports, TERT promoter, CTNNB1, and TP53 have been identified as the most frequently mutated genes. However, there are numerous other genes with lower mutation frequencies reported in HCC. Investigating all of these genes across tumor biopsy samples and three rounds of blood tests was challenging. We also considered that low-frequency genetic variants were likely not to be significantly different even if analyzed. Furthermore, it was also difficult from a cost standpoint. Therefore, it seemed more beneficial to focus on examining genes with higher mutation frequencies, especially considering their potential utility. For this reason, we investigated these three genetic variants in this study.

Finally, our study had some limitations. First, we have a small number of cases. However, the adaptation of cfDNA in HCC to real clinical settings has not been widely practiced yet. While this study has a limited number of subjects, we believe that it provides valuable information to some extent. We intend to further our research by including more patients in the future. Second, validation for blood cells in plasma and contamination of germline mutations are lacked. A previous large study showed that cfDNA fragments harboring somatic tumor-derived mutations, confirmed absent in WBC, were shorter than fragments carrying wild-type alleles consistent with tumor origin [46]. Since we have not completed the analysis of the fragment size in this study, we plan to clarify it in future analyses. Third, TERT promoter was analyzed only in two representative mutations. Because of its genetic structure, as mentioned in Materials and Methods, TERT promoter is difficult to examine by NGS similarly as CTNNB1 and TP53. We decided to evaluate TERT promoter by dPCR in this study because it was particularly difficult to do so with the technology available at the start of this study. However, in recent years, attempts have been made and reported to detect TERT promoter mutations more accurately by NGS [47, 48]. We need to examine the validity of the analysis methods used in this study, as well as find the best method for investigating TERT promoter also by NGS and compare the results with those of other genetic variants under the same conditions. We have implemented NGS on our own, this time. It is necessary to verify how to process cfDNA, for example, using a centrifugation method that prevents blood cells from being mixed, an analysis depth that can detect gene mutations derived from HCC more specifically, and a DNA extraction method.

In conclusion, in this report, no clear correlation was found for the therapeutic effect or PFS with or without mutations in the well-known genes of HCC: TERT promoter, CTNNB1 and TP53. On the other hand, it was suggested that the disease-suppressing effect may be observed in cases in which the mutation frequency before and after treatment decreased. Overall, minimally invasive analysis of cfDNA may be a marker for the molecular-targeted therapy of HCC.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the technical and administrative support provided by Biomedical Research Unit of Tohoku University Hospital and all members of Tohoku University Hospital, Miyagi, Japan.

Statement of Ethics

The study was executed according to the regulations of the Ethics Committee of Tohoku University Hospital (TUH-REC No.: 2019-1-414-16322, date of approval: September 17, 2019). The experiments conformed to the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from patients prior to their participation in the study.

Conflict of Interest Statement

All authors have no potential and real conflicts of interest in the subject of this study.

Funding Sources

No authors received any funding.

Author Contributions

M.T. contributed to the conception of the work, collected and analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. M.N. contributed to the study concept, the data analysis and interpretation, and critically revised the manuscript. J.I. and A.M. supervised the study and revised the manuscript. T.I., A.S., K.S., M.O., and S.S. collected the data and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript to be published.

Funding Statement

No authors received any funding.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the present study are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants but are available from the corresponding author (M.N.) on a reasonable request.

Supplementary Material.

References

- 1. Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74(3):229–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Trinchet JC, Bourcier V, Chaffaut C, Ait Ahmed M, Allam S, Marcellin P, et al. Complications and competing risks of death in compensated viral cirrhosis (ANRS CO12 CirVir prospective cohort). Hepatology. 2015;62(3):737–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. European Association for the Study of the Liver. Electronic address: easloffice@easloffice.eu; European Association for the Study of the Liver . EASL clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2018;69(1):182–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kudo M, Ueshima K, Chan S, Minami T, Chishina H, Aoki T, et al. Lenvatinib as an initial treatment in patients with intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma beyond up-to-seven criteria and Child-Pugh A liver function: a proof-of-concept study. Cancers. 2019;11(8):1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wang YY, Zhong JH, Xu HF, Xu G, Wang LJ, Xu D, et al. A modified staging of early and intermediate hepatocellular carcinoma based on single tumour >7 cm and multiple tumours beyond up-to-seven criteria. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49(2):202–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, Galle PR, Ducreux M, Kim TY, et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(20):1894–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kudo M, Kawamura Y, Hasegawa K, Tateishi R, Kariyama K, Shiina S, et al. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma in Japan: JSH consensus statements and recommendations 2021 update. Liver Cancer. 2021;10(3):181–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tohyama O, Matsui J, Kodama K, Hata-Sugi N, Kimura T, Okamoto K, et al. Antitumor activity of lenvatinib (e7080): an angiogenesis inhibitor that targets multiple receptor tyrosine kinases in preclinical human thyroid cancer models. J Thyroid Res. 2014;2014:638747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Al-Salama ZT, Syed YY, Scott LJ. Lenvatinib: a review in hepatocellular carcinoma. Drugs. 2019;79(6):665–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kudo M. Lenvatinib may drastically change the treatment landscape of hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Cancer. 2018;7(1):1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schulze K, Imbeaud S, Letouzé E, Alexandrov LB, Calderaro J, Rebouissou S, et al. Exome sequencing of hepatocellular carcinomas identifies new mutational signatures and potential therapeutic targets. Nat Genet. 2015;47(5):505–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zucman-Rossi J, Villanueva A, Nault JC, Llovet JM. Genetic landscape and biomarkers of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(5):1226–39.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhu S, Hoshida Y. Molecular heterogeneity in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepat Oncol. 2018;5(1):Hep10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chan KC, Jiang P, Zheng YW, Liao GJ, Sun H, Wong J, et al. Cancer genome scanning in plasma: detection of tumor-associated copy number aberrations, single-nucleotide variants, and tumoral heterogeneity by massively parallel sequencing. Clin Chem. 2013;59(1):211–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ono A, Fujimoto A, Yamamoto Y, Akamatsu S, Hiraga N, Imamura M, et al. Circulating tumor DNA analysis for liver cancers and its usefulness as a liquid biopsy. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;1(5):516–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Huang A, Zhang X, Zhou SL, Cao Y, Huang XW, Fan J, et al. Detecting circulating tumor DNA in hepatocellular carcinoma patients using droplet digital PCR is feasible and reflects intratumoral heterogeneity. J Cancer. 2016;7(13):1907–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bouattour M, Mehta N, He AR, Cohen EI, Nault JC. Systemic treatment for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Cancer. 2019;8(5):341–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. He G, Chen Y, Zhu C, Zhou J, Xie X, Fei R, et al. Application of plasma circulating cell-free DNA detection to the molecular diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Transl Res. 2019;11(3):1428–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Howell J, Atkinson SR, Pinato DJ, Knapp S, Ward C, Minisini R, et al. Identification of mutations in circulating cell-free tumour DNA as a biomarker in hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Cancer. 2019;116:56–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fujii Y, Ono A, Hayes CN, Aikata H, Yamauchi M, Uchikawa S, et al. Identification and monitoring of mutations in circulating cell-free tumor DNA in hepatocellular carcinoma treated with lenvatinib. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2021;40(1):215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hiraoka A, Michitaka K, Kumada T, Izumi N, Kadoya M, Kokudo N, et al. Validation and potential of albumin-bilirubin grade and prognostication in a nationwide survey of 46,681 hepatocellular carcinoma patients in Japan: the need for a more detailed evaluation of hepatic function. Liver Cancer. 2017;6(4):325–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lencioni R, Llovet JM. Modified RECIST (mRECIST) assessment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2010;30(1):52–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Llovet JM, Lencioni R. mRECIST for HCC: performance and novel refinements. J Hepatol. 2020;72(2):288–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mitas M, Yu A, Dill J, Kamp TJ, Chambers EJ, Haworth IS. Hairpin properties of single-stranded DNA containing a GC-rich triplet repeat: (CTG)15. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23(6):1050–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Colebatch AJ, Witkowski T, Waring PM, McArthur GA, Wong SQ, Dobrovic A. Optimizing amplification of the GC-rich TERT promoter region using 7-Deaza-dGTP for droplet digital PCR quantification of TERT promoter mutations. Clin Chem. 2018;64(4):745–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chen YL, Jeng YM, Chang CN, Lee HJ, Hsu HC, Lai PL, et al. TERT promoter mutation in resectable hepatocellular carcinomas: a strong association with hepatitis C infection and absence of hepatitis B infection. Int J Surg. 2014;12(7):659–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pezzuto F, Izzo F, De Luca P, Biffali E, Buonaguro L, Tatangelo F, et al. Clinical significance of telomerase reverse-transcriptase promoter mutations in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancers. 2021;13(15):3771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Thorvaldsdóttir H, Robinson JT, Mesirov JP. Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV): high-performance genomics data visualization and exploration. Brief Bioinform. 2013;14(2):178–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nance T, Helman E, Artieri C, Yen J, Slavin TP, Chudova D, et al. Abstract 4272: a novel approach to differentiation of somatic vs. germline variants in liquid biopsies using a betabinomial model. Cancer Res. 2018;78(13_Suppl):4272–2. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zill OA, Banks KC, Fairclough SR, Mortimer SA, Vowles JV, Mokhtari R, et al. The landscape of actionable genomic alterations in cell-free circulating tumor DNA from 21,807 advanced cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(15):3528–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nakamura Y, Taniguchi H, Ikeda M, Bando H, Kato K, Morizane C, et al. Clinical utility of circulating tumor DNA sequencing in advanced gastrointestinal cancer: SCRUM-Japan GI-SCREEN and GOZILA studies. Nat Med. 2020;26(12):1859–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rebouissou S, Franconi A, Calderaro J, Letouzé E, Imbeaud S, Pilati C, et al. Genotype-phenotype correlation of CTNNB1 mutations reveals different ß-catenin activity associated with liver tumor progression. Hepatology. 2016;64(6):2047–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Calderaro J, Couchy G, Imbeaud S, Amaddeo G, Letouzé E, Blanc JF, et al. Histological subtypes of hepatocellular carcinoma are related to gene mutations and molecular tumour classification. J Hepatol. 2017;67(4):727–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wan JCM, Massie C, Garcia-Corbacho J, Mouliere F, Brenton JD, Caldas C, et al. Liquid biopsies come of age: towards implementation of circulating tumour DNA. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17(4):223–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. von Felden J, Craig AJ, Garcia-Lezana T, Labgaa I, Haber PK, D’Avola D, et al. Mutations in circulating tumor DNA predict primary resistance to systemic therapies in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene. 2021;40(1):140–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ng CKY, Di Costanzo GG, Tosti N, Paradiso V, Coto-Llerena M, Roscigno G, et al. Genetic profiling using plasma-derived cell-free DNA in therapy-naïve hepatocellular carcinoma patients: a pilot study. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(5):1286–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Li L, Wang H, Yang ES, Arteaga CL, Xia F. Erlotinib attenuates homologous recombinational repair of chromosomal breaks in human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68(22):9141–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cao X, Zhou Y, Sun H, Xu M, Bi X, Zhao Z, et al. EGFR-TKI-induced HSP70 degradation and BER suppression facilitate the occurrence of the EGFR T790 M resistant mutation in lung cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2018;424:84–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zheng A, Chevalier N, Calderoni M, Dubuis G, Dormond O, Ziros PG, et al. CRISPR/Cas9 genome-wide screening identifies KEAP1 as a sorafenib, lenvatinib, and regorafenib sensitivity gene in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2019;10(66):7058–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bell RJ, Rube HT, Xavier-Magalhães A, Costa BM, Mancini A, Song JS, et al. Understanding TERT promoter mutations: a common path to immortality. Mol Cancer Res. 2016;14(4):315–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nault JC, Calderaro J, Di Tommaso L, Balabaud C, Zafrani ES, Bioulac-Sage P, et al. Telomerase reverse transcriptase promoter mutation is an early somatic genetic alteration in the transformation of premalignant nodules in hepatocellular carcinoma on cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2014;60(6):1983–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Akuta N, Kawamura Y, Kobayashi M, Arase Y, Saitoh S, Fujiyama S, et al. TERT promoter mutation in serum cell-free DNA is a diagnostic marker of primary hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Oncology. 2021;99(2):114–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pinyol R, Sia D, Llovet JM. Immune exclusion-wnt/CTNNB1 class predicts resistance to immunotherapies in HCC. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(7):2021–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ruiz de Galarreta M, Bresnahan E, Molina-Sánchez P, Lindblad KE, Maier B, Sia D, et al. β-Catenin activation promotes immune escape and resistance to anti-PD-1 therapy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2019;9(8):1124–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Aoki T, Kudo M, Ueshima K, Morita M, Chishina H, Takita M, et al. Exploratory analysis of lenvatinib therapy in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma who have failed prior PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint blockade. Cancers. 2020;12(10):3048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rose Brannon A, Jayakumaran G, Diosdado M, Patel J, Razumova A, Hu Y, et al. Enhanced specificity of clinical high-sensitivity tumor mutation profiling in cell-free DNA via paired normal sequencing using MSK-ACCESS. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):3770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gupta S, Vanderbilt CM, Lin YT, Benhamida JK, Jungbluth AA, Rana S, et al. A pan-cancer study of somatic TERT promoter mutations and amplification in 30,773 tumors profiled by clinical genomic sequencing. J Mol Diagn. 2021;23(2):253–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lee H, Lee B, Kim DG, Cho YA, Kim JS, Suh YL. Detection of TERT promoter mutations using targeted next-generation sequencing: overcoming GC bias through trial and error. Cancer Res Treat. 2022;54(1):75–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the present study are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants but are available from the corresponding author (M.N.) on a reasonable request.