Abstract

Introduction

Although cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) effectively treats obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), many patients refuse CBT or drop out prematurely, partly because of anxiety regarding exposure and response prevention (ERP) exercises. Inference-based cognitive behavioral therapy (I-CBT) focuses on correcting distorted inferential thinking patterns, enhancing reality-based reasoning, and addressing obsessional doubt by targeting underlying dysfunctional reasoning, without incorporating an ERP component. We hypothesized that I-CBT would be non-inferior to CBT. Additionally, we hypothesized that I-CBT would be more tolerable than CBT.

Methods

197 participants were randomly assigned to 20 sessions CBT or I-CBT and assessed at baseline, posttreatment, and 6 and 12 months’ follow-up. The primary outcome was OCD symptom severity measured using the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS; non-inferiority margin: 2 points). The secondary outcome, treatment tolerability, was assessed using the Treatment Acceptability/Adherence Scale (TAAS). A linear mixed-effects model was used to assess the non-inferiority of the primary outcome and superiority of secondary outcomes.

Results

Statistically significant within-group improvements in the primary and secondary outcomes were observed in both treatments. No statistically significant between-group differences in Y-BOCS were found at any assessment point, but the confidence intervals exceeded the non-inferiority threshold, making the results inconclusive. The estimated mean posttreatment TAAS score was significantly higher in the I-CBT group than in the CBT group.

Conclusion

While both CBT and I-CBT are effective for OCD, whether I-CBT is non-inferior to CBT in terms of OCD symptom severity remains inconclusive. Nevertheless, I-CBT offers better tolerability and warrants consideration as an alternative treatment for OCD.

Keywords: Inference-based cognitive behavioral therapy, Cognitive behavioral therapy, Obsessive-compulsive disorder, Treatment outcome, Psychiatric disorders

Introduction

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a severe mental condition characterized by the occurrence of intrusive thoughts, urges, or images (obsessions), and/or repetitive behaviors or mental acts in response to obsessions (compulsions). Its disturbing effects on the quality of life (QoL), coupled with a high rate of chronicity and high family burden, highlight the urgent need for effective treatment [1–5]. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) with exposure and response prevention (ERP) is the gold standard of treatment [6, 7]. Several meta-analyses of CBT for OCD have indicated large effect sizes when comparing CBT with waitlist controls (d = 1.13 to d = 1.31) [8, 9]. However, only 43–52% of patients achieve remission after treatment [8]. Nonresponders to CBT may potentially benefit from new treatment approaches with different mechanisms of action.

CBT with ERP is a challenging treatment, as patients are required to confront feared situations while refraining from compulsive or avoidant behaviors, which can generate significant anxiety. Although a definitive relationship has not been established [10], this may contribute to drop-out and refusal rates, which occur in approximately 15% of cases [11]. Mancebo et al. [12] reported that among those who discontinued CBT for OCD, fear and anxiety regarding CBT were reasons to refuse or terminate in more than 25% of cases. Therefore, a less anxiety-inducing yet effective treatment would be highly beneficial. One promising alternative is the inference-based cognitive behavioral therapy (I-CBT), also known as inference-based therapy (IBT), a cognitive behavioral treatment that focuses on addressing invalid reasoning processes that lead individuals to confuse possibilities with reality without incorporating an ERP component. I-CBT considers obsessional doubt to be a central problem in OCD [13]. This obsessional doubt arises from “inferential confusion” [14, 15], a dysfunctional reasoning process that entails excessive reliance on imagination and possibilities rather than actual evidence or sensory input [13]. I-CBT takes an “upstream” approach by addressing the inferential processes that give rise to obsessive doubts in the first place, reestablishing trust in the senses, self, and common sense, and relating to reality in a non-obsessive way, without any direct exposure component. Therefore, it is hypothesized that I-CBT does not provoke high levels of anxiety.

Data from a few studies have provided evidence for the effectiveness of I-CBT in OCD [13, 16–18]. A small RCT of 54 patients with OCD suggested similar outcomes for CBT and I-CBT [13]. These findings were further confirmed in a larger RCT on OCD involving 90 patients with poor insight, which found no statistically significant differences in treatment outcomes between I-CBT and CBT [16]. Furthermore, an open trial with 102 patients with OCD showed that I-CBT is effective across all major subtypes, as well as in treatment-resistant cases [18]. In addition, a recent RCT of 111 patients with OCD reported no statistically significant differences between I-CBT and CBT [17]. Despite these promising results, the non-inferiority of I-CBT when compared to CBT has to the best of our knowledge not been investigated.

The objectives of the current study were: (1) to assess the non-inferiority of I-CBT compared to CBT, (2) to evaluate the tolerability of I-CBT compared to CBT, and (3) to compare the effectiveness of I-CBT with CBT on secondary outcome measures, including QoL, functional impairment, insight in OCD, and depressive and anxiety symptoms. We hypothesized that I-CBT is non-inferior to CBT in reducing OCD symptom severity as measured by the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) at posttreatment, and at the 6 and 12 months’ follow-up. Additionally, we hypothesized that I-CBT is statistically significantly more tolerable than CBT. Other secondary outcomes were also assessed for superiority. This study adhered to the CONSORT guidelines for reporting RCTs.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

This study was a two-arm non-inferiority, multicenter RCT comparing 20 sessions of I-CBT to 20 sessions of CBT in patients with OCD, with 6-month and 12-month follow-ups (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT03929081). Outcome measures including neural correlates on brain structure and brain function will be analyzed and reported in a separate manuscript.

Participants were recruited from outpatient clinics in seven Dutch mental healthcare institutions, four of which were highly specialized in anxiety disorders and OCD, between March 2019 and October 2023. The primary eligibility criteria were as follows: (1) a minimum age of 18 years; (2) a primary diagnosis of OCD according to DSM-5; (3) moderate-to-severe OCD symptom severity expressed as a minimum score of 16 on the Y-BOCS; (4) no use of psychotropic medication, or use of a stable dose for at least 12 weeks preceding baseline and willingness to continue the dose for the duration of the study (monitored during the study); and (5) no receipt of CBT for OCD in the 6 months preceding baseline. Participants were excluded if they had a psychotic disorder, organic mental disorder, substance dependence, mental retardation, or insufficient comprehension of the Dutch language.

Randomization and Blinding

Participants were randomly assigned to either the CBT or I-CBT group after eligibility and baseline assessments. Randomization was conducted centrally by independent researchers using computerized random number generation (ratio 1:1). To maintain allocation concealment from research assessors, therapists received treatment assignments via email and informed participants about the treatment modality to which they had been allocated.

The research assessors were blinded to the treatment conditions; however, this was not always maintained until the final measurement. If blinding was unintentionally broken, participants were reassigned to a new blinded assessor, if feasible. In instances where this was not possible, assessors were not part of the research team, data analysis, or writing process to ensure impartiality. Therapists and participants were instructed not to disclose the treatment details to the assessors.

Treatment Conditions

Standardized treatment protocols were used for both treatment conditions. Both treatments consisted of 20 individual weekly 45-min sessions. Each session used a format starting with agenda setting and evaluating homework assignments, followed by in-session practice and planning of new homework. In both treatment conditions, homework was performed between sessions. Both treatments were delivered face to face. However, since this study was partially conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, some participants received their treatment partially or entirely via video conference due to restrictions.

Inference-Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

In I-CBT, people learn to observe the invalid reasoning process of OCD, gaining insight into how their reasoning leads to doubting the actual state of affairs [19]. This approach involves several steps: (1) illustrate the central role of obsessional doubt; (2) identify the “OCD-stories” that lead to the obsessional doubt and to expose its power; (3) develop alternative non-obsessive stories based on present reality, to show how changing the story affects feelings and behavior even when reality is unchanged; (4) understand that reasoning processes that occur in OCD situations are different from those that occur in non-OCD situations. With observation exercises, patients learn to recognize that their doubt always arises in the absence of any sensory proof in the here and now, and thus is 100% imaginary and that the obsession or doubt is therefore 100% irrelevant even though it may be possible; (5) learn to recognize the exact moment in which patients are still in touch with reality but are about to become absorbed in obsessive reasoning, leaving reality behind. Patients are trained to rely on the observable reality of that moment; (6) show patients how their typical OCD reasoning distracts them from the observable reality and therefore makes the feared situation seem real; (7) identify vulnerable self-themes in relation to obsessional doubt; (8) tolerate the void that arises when less time is spent on compulsive behavior; and (9) develop a relapse prevention plan.

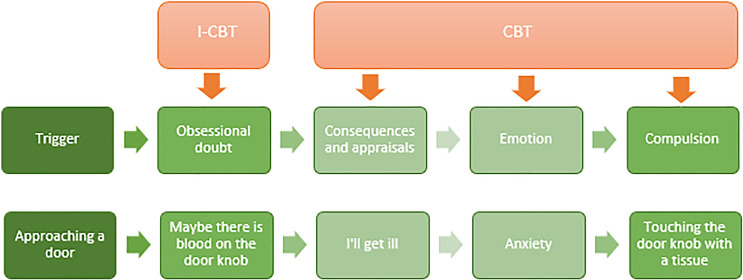

I-CBT differs from CBT. I-CBT focuses on obsessional thoughts, whereas CBT focuses primarily on feared consequences or appraisals of the obsession or on anxiety and compulsions [20]. In I-CBT, no restructuring of the content of obsessions takes place; instead, I-CBT primarily targets the underlying reasoning behind obsessional doubt and teaches patients to trust the senses, self, and common sense, as in other non-OCD situations. A key distinction between I-CBT and CBT is the absence of an ERP component and behavioral experiment in the I-CBT; there is no deliberate activation of fear involved. I-CBT is primarily a cognitive approach. A minor behavioral component of I-CBT is that patients pause to reflect on their reasoning when a spontaneous confrontation with their obsession occurs, and then focus their attention to observable reality. They refrain from their compulsion only when they can confidently determine that everything is fine here and now. A schematic representation of the difference between I-CBT and CBT is shown in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the difference between I-CBT and CBT.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Participants randomized to the CBT group underwent sessions consisting of self-guided and therapist-guided ERP [21] and cognitive therapy (CT) [20]. Treatment included (1) introductory sessions to establish a list of compulsions and explain the rationale behind ERP and CT; (2) at least 12 ERP sessions with exposure exercises during which patients faced their obsessional fears while refraining from compulsive or avoidant behaviors; (3) CT sessions to establish and challenge obsessions and (metacognitive) appraisals and conduct behavioral experiments to test a belief or prediction; and (4) sessions focusing on relapse prevention. Although ERP and CT had to be addressed fully, therapists were free to adjust the order of ERP and CT according to the patient’s needs.

E-Health Package

Psycho-education and homework assignments for both treatments were offered through an online platform specifically designed for this study. Therapists were not allowed to provide digital feedback on the homework assignments to prevent additional treatment beyond 20 sessions as per the study protocol, to prevent differences between the treatment conditions in the amount of treatment participants received, and to prevent blended care.

Therapists

All therapists had at least a master’s degree in psychology or medicine and were experienced in the treatment of patients with OCD. Therapists were allowed to provide both treatment conditions. Therapists providing I-CBT received a 4-day I-CBT workshop given by H.V. They subsequently treated at least 1 patient with OCD under bimonthly supervision by H.V. before the start of the study to allow the therapist to gain familiarity with the protocol. Bimonthly supervision by skilled supervisors was provided in both conditions during this study.

Therapists were extensively trained in compliance with the treatment protocol. Furthermore, treatment sessions were audio-recorded and a randomly selected sample was rated on compliance with the treatment protocol by an independent assessor using a 7-point scale (range 0–6).

Measures

Demographic variables (age, sex, education, and marital status) and history of OCD treatment were collected at baseline. Clinician-rated measures were administered at baseline, posttreatment (after 20 sessions), and at follow-up (6 and 12 months posttreatment). At each measurement point, research assessors systematically assessed serious adverse events. In addition to these measurements, all self-report measures were administered at mid-treatment (after 10 sessions).

Participants who dropped out of treatment were assessed immediately, regardless of the reason for dropout. These measurements were included in intention-to-treat (ITT) analyses, but participants were excluded from per-protocol (PP) analyses.

Clinician-Rated Measures

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (SCID-5) was used to confirm the diagnosis of OCD and comorbidity with other mental disorders, and remission was determined posttreatment [22]. The clinician-rated Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) was used to assess OCD severity and served as the primary outcome measure [23]. The Y-BOCS, a 10-item scale with scores ranging from 0 (no symptoms) to 40 (extreme symptoms), is the gold standard for measuring OCD severity and has a well-documented validity and reliability [23]. Y-BOCS was also used to determine the treatment response: a 35% reduction in Y-BOCS [24].

The Overvalued Ideas Scale (OVIS) was used to assess insight in OCD [25]. The OVIS is a 10-item scale that includes the following items: strength, reasonableness, and accuracy of belief; the extent to which others share beliefs; attribution of similar or differing views; the effectiveness of compulsions; the extent to which the disorder has caused the belief; and the strength of the resistance to the belief. Each item of the OVIS was rated from 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating poorer insight. The total score was the sum divided by 10.

Self-Report Measures

The Treatment Acceptability/Adherence Scale (TAAS) was used to assess treatment tolerability [26]. This 10-item questionnaire evaluates the acceptability of, and adherence to, psychological treatment for anxiety and related disorders. Participants rate their agreement with statement (e.g., “I would find this treatment exhausting,” “It was distressing to me to participate in this treatment”) on a 7-point scale (1 = “strongly disagree” to 7 = “strongly agree”). The TAAS scores range from 7 to 70, with higher scores indicating greater treatment tolerability. The baseline TAAS was administered after randomization, once participants had been informed whether they would receive CBT or I-CBT, but before the first treatment session.

The EuroQol five-dimensional questionnaire (EQ-5D) was used to assess QoL [27]. It includes dimensions of mobility, self-care, daily activities, pain/discomfort, and depression/anxiety, each rated at three levels (no problems, some problems, and major problems) and converted into an index score ranging from 0 (worst health) to 1 (best health).

The Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS) was used to assess functional impairment [28]. This 3-item scale measures the impact of symptomatology on work/school and social and family functioning. Each item was rated on a 10-point scale, with higher scores indicating more severe impairment (range 0–30).

The Beck Depression Inventory was used to assess the severity of depressive symptoms [29], and the Beck Anxiety Inventory was used to assess the severity of anxiety symptoms [30] (range: 0–63, with higher scores indicating greater severity). The Credibility/Expectancy Questionnaire (CEQ) was used to assess treatment credibility (range 3–27) and expectancy (range 3–27) for improvement, with higher scores indicating greater credibility and expectancy [31].

Statistical Analyses

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, version 28). Non-inferiority was tested using the confidence interval (CI) approach. If the upper limit of the two-sided 95% CI of the mean difference between treatments is less than the prespecified positive non-inferiority margin, non-inferiority is established with the associated alpha level [32]. A meta-analysis on the effectiveness of CBT for OCD [33] indicated a mean (95% CI) between-group effect size of CBT relative to placebo of 1.39 (1.04, 1.74). A fraction of 40% of the lower limit of the 95% CI (1.04) generated a non-inferiority margin of 0.42. This margin represents a 2 point difference in the primary outcome measure (Y-BOCS). The power analyses for our hypothesis that I-CBT is non-inferior to CBT showed that a sample size of 71 per treatment condition was required to obtain a power of 0.80 (alpha = 0.05, non-inferiority margin = 0.42). Anticipating a 30% dropout rate, we aimed to enroll 203 participants; however, we included 204 participants due to an administrative error. Non-inferiority was evaluated only for the primary outcome, whereas other outcomes were analyzed for superiority. This approach was adopted because the power calculation was based on a non-inferiority margin of the primary outcome measure, and no non-inferiority margins were established for the secondary outcome measures.

Linear mixed model (LMM) analyses were used to evaluate differences in OCD symptom severity (primary outcome) and secondary outcomes between the I-CBT and CGT groups. Depending on the frequency of the outcome measures, the fixed effects of the LMM included one to four time indicators and the same number of corresponding time-by-intervention interaction terms. For most analyses, the intervention indicator variable itself was not included in the fixed effects part of the model. Hence, the regression parameters of the time-by-intervention interaction terms estimated the intervention effect at different time points, correcting for baseline differences in the outcome variable. LMM analysis is able to address missing data resulting from dropout under the assumption that the missing data mechanism is missing at random [34]. The analyses were based on a modified ITT sample, excluding participants who were found to be ineligible after randomization. We also analyzed the primary and secondary outcomes in the PP sample, which consisted of participants who completed at least 12 sessions of CBT or I-CBT, or achieved remission before 12 sessions. PP analyses and analyses of the secondary outcome TAAS were not corrected for baseline differences, as the mean baseline scores could differ.

Results

Baseline Characteristics and Differences

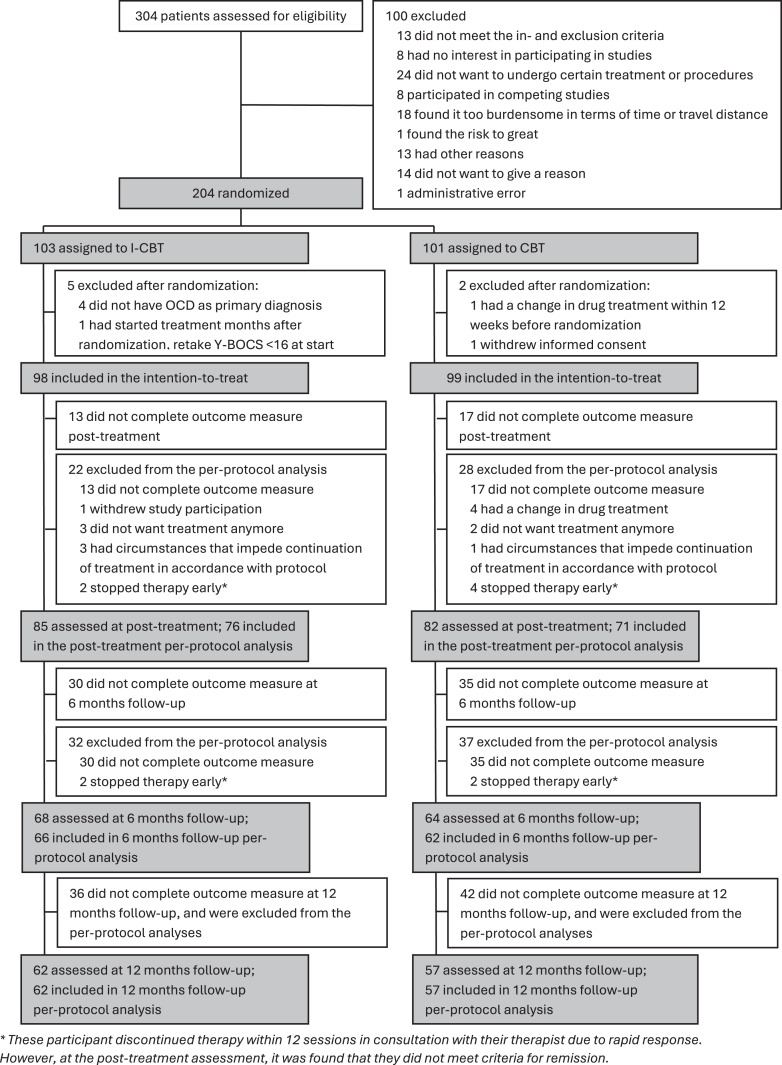

A total of 304 individuals were assessed for eligibility, of whom 204 were randomized to CBT or I-CBT (shown in Fig. 2). Six individuals were retrospectively identified as ineligible for the study, as subsequent information revealed that they did not meet the inclusion criteria, and one withdrew informed consent, resulting in 197 participants in the ITT sample (I-CBT: N = 98; CBT: N = 99). During treatment, 50 participants (25.4%) dropped out, leaving 147 in the PP sample posttreatment (I-CBT: N = 76; CBT: N = 71).

Fig. 2.

Flow diagram of a randomized controlled trial comparing I-CBT and CBT. *These participants discontinued therapy within 12 sessions in consultation with their therapist due to rapid response. However, at the posttreatment assessment, it was found that they did not meet criteria for remission.

At baseline, participants had a mean Y-BOCS score of 24.7 (SD = 4.6), indicating severe OCD. The mean OVIS score was 5.0 (SD = 1.4), reflecting medium insight in OCD. Depressive symptoms (BDI: mean = 16.0; SD = 9.5) and anxiety symptoms (BAI: mean = 16.6; SD = 9.7) were mild. The mean EQ-5D utility score was 0.7 (SD = 0.2), indicating a poor QoL [35]. The mean SDS score was 14.2 (SD = 7.6), indicating substantial functional impairment. Table 1 shows the baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the treatment groups. The mean TAAS score was statistically significantly higher in the I-CBT group than in the CBT group (t(187) = −3.30, p < 0.001), indicating that participants rated I-CBT as more tolerable than CBT before the treatment started. No statistically significant differences were found between the treatment groups with respect to other variables.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study sample

| Characteristics | CBT (n = 99) | I-CBT (n = 98) |

|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographics | ||

| Age, years | 33.7±11.8 | 33.9±11.6 |

| Sex, female, % | 62 | 62 |

| Partner, yes, % | 60 | 68 |

| Children, yes, % | 35 | 30 |

| Employment, yes, % | 65 | 76 |

| OCD | ||

| Age at onset | 16.9±9.8 | 15.1±8.2 |

| Duration of illness | 16.8±10.6 | 18.8±12.0 |

| Overall severity (Y-BOCS) | 24.9±4.4 | 24.5±4.9 |

| Obsessions (Y-BOCS) | 12.1±2.6 | 11.9±2.8 |

| Compulsions (Y-BOCS) | 12.9±2.6 | 12.7±2.9 |

| Treatment credibility and expectancy | ||

| Treatment credibility (CEQ) | 19.5±4.6 | 20.1±3.6 |

| Treatment expectancy (CEQ) | 16.1±5.2 | 16.7±4.3 |

| Secondary outcomes | ||

| Treatment tolerability (TAAS) | 47.7±7.7 | 51.0±6.0 |

| Insight (OVIS) | 5.0±1.4 | 5.0±1.4 |

| QoL (EQ-5D utility score) | 0.7±0.2 | 0.7±0.2 |

| Functional impairment (SDS) | 13.8±7.3 | 14.6±8.0 |

| Depression (BDI) | 16.6±9.5 | 15.4±9.6 |

| Anxiety (BAI) | 17.0±9.7 | 16.2±9.7 |

| Comorbidity, previous treatment, and current treatment with medication | ||

| Current comorbidity, yes, % | 59 | 47 |

| Current comorbid disorder, n | 1.0±1.2 | 0.7±1.1 |

| Current antidepressants, yes, % | 38 | 37 |

| Current benzodiazepines, yes, % | 8 | 10 |

| Current atypical antipsychotics, yes, % | 3 | 5 |

| Previous treatment for OCDa, yes, % | 36 | 38 |

Values represent means ± SD or n (%). TAAS was statistically significantly higher for IBA compared to CBT (t(187) = −3.30, p = <0.001). There were no statistically significant differences between the treatment groups on the other variables.

CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy; I-CBT, inference-based cognitive behavioral therapy; OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder; Y-BOCS, Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale; OVIS, Overvalued Ideation Scale; EQ-5D, EuroQol five-dimensional questionnaire; SDS, Sheehan Disability Scale; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory.

aAt least 600-min CBT.

The PP sample (N = 147) was compared with dropouts (N = 50) in terms of baseline variables. Statistically significant differences were found in previous treatment for OCD (at least 600 min of CBT for OCD) (χ2(1) = 6.5, p = 0.01; 42% of the PP sample received previous treatment for OCD compared to 22% of the dropouts) and treatment tolerability (PP: M = 49.9, SD = 7.4; dropouts: M = 47.5, SD = 5.7; t(187) = −2.1, p = 0.04). No statistically significant differences were found in the other variables at baseline.

Main Outcome and Non-Inferiority Analyses

The observed mean values of the primary and secondary outcomes of the ITT sample are presented in Table 2. Table 3 presents the results of LMM. The PP analyses are presented in the Supplementary Material (for all online suppl. material, see https://doi.org/10.1159/000541508).

Table 2.

Mean scores for primary and secondary outcomes of the ITT sample for CBT and I-CBT across different time points

| CBT | I-CBT | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | mean | SD | n | mean | SD | |

| Primary outcome | ||||||

| OCD severity (Y-BOCS) | ||||||

| Baseline | 99 | 24.91 | 4.37 | 98 | 24.53 | 4.93 |

| Posttreatment | 82 | 14.38 | 7.80 | 85 | 16.66 | 7.88 |

| FU 6 months | 64 | 10.47 | 7.08 | 68 | 12.37 | 7.97 |

| FU 12 months | 57 | 9.30 | 7.12 | 62 | 12.32 | 8.34 |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||

| Tolerability (TAAS) | ||||||

| Baseline | 94 | 47.66 | 7.69 | 95 | 50.97 | 6.00 |

| Mid-treatment | 80 | 50.25 | 7.81 | 81 | 55.58 | 6.63 |

| Posttreatment | 75 | 49.61 | 9.86 | 79 | 54.92 | 7.81 |

| Insight (OVIS) | ||||||

| Baseline | 99 | 5.02 | 1.40 | 98 | 5.03 | 1.40 |

| Posttreatment | 82 | 3.38 | 1.60 | 85 | 3.58 | 1.69 |

| FU 6 months | 64 | 2.60 | 1.31 | 68 | 3.00 | 1.33 |

| FU 12 months | 57 | 2.46 | 1.42 | 62 | 2.77 | 1.38 |

| QoL (EQ-5D) | ||||||

| Baseline | 98 | 0.65 | 0.23 | 98 | 0.65 | 0.22 |

| Mid-treatment | 80 | 0.68 | 0.24 | 81 | 0.70 | 0.23 |

| Posttreatment | 75 | 0.78 | 0.21 | 79 | 0.74 | 0.22 |

| FU 6 months | 55 | 0.85 | 0.18 | 65 | 0.82 | 0.16 |

| FU 12 months | 50 | 0.85 | 0.19 | 60 | 0.81 | 0.20 |

| Functional impairment (SDS) | ||||||

| Baseline | 78 | 13.81 | 7.31 | 87 | 14.57 | 7.95 |

| Mid-treatment | 62 | 10.98 | 7.70 | 61 | 12.26 | 8.24 |

| Posttreatment | 58 | 7.66 | 7.53 | 59 | 10.34 | 8.30 |

| FU 6 months | 45 | 4.42 | 5.45 | 50 | 7.60 | 7.33 |

| FU 12 months | 41 | 5.98 | 8.13 | 44 | 8.11 | 8.06 |

| Depression (BDI) | ||||||

| Baseline | 98 | 16.62 | 9.54 | 98 | 15.40 | 9.56 |

| Mid-treatment | 80 | 14.91 | 9.29 | 82 | 14.22 | 8.95 |

| Posttreatment | 75 | 11.49 | 10.55 | 79 | 11.48 | 8.01 |

| FU 6 months | 55 | 8.00 | 9.94 | 65 | 9.66 | 8.09 |

| FU 12 months | 50 | 7.02 | 9.28 | 60 | 9.25 | 7.99 |

| Anxiety (BAI) | ||||||

| Baseline | 98 | 16.96 | 9.73 | 98 | 16.16 | 9.68 |

| Mid-treatment | 80 | 16.56 | 10.02 | 81 | 14.68 | 8.11 |

| Posttreatment | 75 | 13.16 | 9.69 | 79 | 12.30 | 7.80 |

| FU 6 months | 55 | 9.95 | 10.52 | 65 | 10.62 | 7.91 |

| FU 12 months | 50 | 10.08 | 10.06 | 60 | 10.12 | 7.57 |

CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy; I-CBT, inference-based cognitive behavioral therapy; SD, standard deviation; Y-BOCS, Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale; TAAS, Treatment Acceptability/Adherence Scale; OVIS, Overvalued Ideas Scale; EQ-5D, EuroQol five-dimensional questionnaire; SDS, Sheehan Disability Scale; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; FU, follow-up.

Table 3.

Test statistics and between-group effect sizes of the differences in primary and secondary outcomes of the ITT sample between CBT and I-CBT, from LMM analyses

| t | p value | Effect size (d) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | |||

| OCD severity (Y-BOCS) | |||

| Condition*posttreatment | 1.87 | 0.06 | 0.44 |

| Condition*FU 6 months | 0.88 | 0.38 | 0.23 |

| Condition*FU 12 months | 1.15 | 0.25 | 0.32 |

| Secondary outcomes | |||

| Tolerability (TAAS) | |||

| Condition + condition*mid-treatment | 4.78 | <0.001 | 0.74 |

| Condition + condition*posttreatment | 4.01 | <0.001 | 0.75 |

| Insight (OVIS) | |||

| Condition*posttreatment | 0.80 | 0.43 | 0.12 |

| Condition*FU 6 months | 1.76 | 0.08 | 0.27 |

| Condition*FU 12 months | 0.80 | 0.43 | 0.13 |

| QoL (EQ-5D) | |||

| Condition*mid-treatment | 1.12 | 0.26 | 0.14 |

| Condition*posttreatment | −1.17 | 0.24 | −0.14 |

| Condition*FU 6 months | 0.14 | 0.89 | 0.02 |

| Condition*FU 12 months | 0.16 | 0.88 | 0.02 |

| Functional impairment (SDS) | |||

| Condition*mid-treatment | −0.03 | 0.98 | −0.00 |

| Condition*posttreatment | 1.03 | 0.31 | 0.14 |

| Condition*FU 6 months | 0.78 | 0.44 | 0.12 |

| Condition*FU 12 months | −0.47 | 0.64 | −0.08 |

| Depression (BDI) | |||

| Condition*mid-treatment | −0.21 | 0.83 | −0.02 |

| Condition*posttreatment | 0.23 | 0.82 | 0.03 |

| Condition*FU 6 months | −0.01 | 0.99 | −0.00 |

| Condition*FU 12 months | 0.05 | 0.96 | 0.01 |

| Anxiety (BAI) | |||

| Condition*mid-treatment | −1.13 | 0.26 | −0.13 |

| Condition*posttreatment | −0.41 | 0.68 | −0.05 |

| Condition*FU 6 months | −0.22 | 0.83 | −0.03 |

| Condition*FU 12 months | −0.48 | 0.48 | −0.09 |

Bold indicates p < 0.05.

Y-BOCS, Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale; TAAS, Treatment Acceptability/Adherence Scale; OVIS, Overvalued Ideas Scale; EQ-5D, EuroQol five-dimensional questionnaire; SDS, Sheehan Disability Scale; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; FU, follow-up.

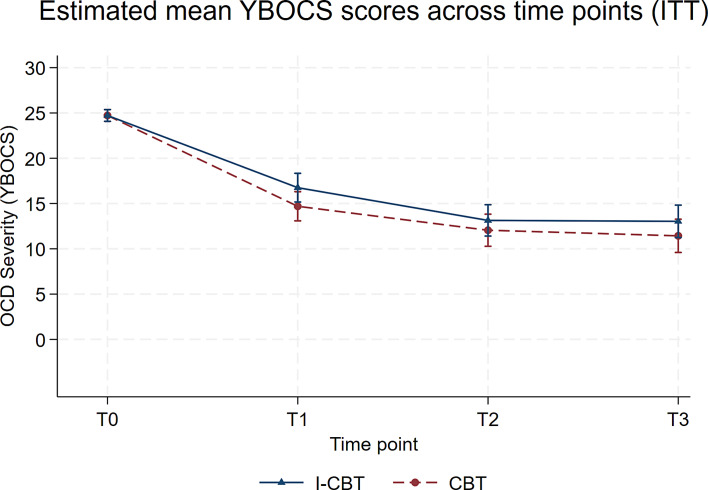

Both groups showed statistically significant improvements in OCD symptom severity during treatment. The CBT group showed an average improvement of 10.02 points on the Y-BOCS from baseline to posttreatment (95% CI: −11.57 to −8.48), while the I-CBT group improved by 7.97 points (95% CI: −11.68 to −4.26) (shown in Fig. 3). High within-group effect sizes were found for both CBT (d = −2.16, 95% CI: −2.49 to −1.82, p < 0.001) and I-CBT (d= −1.71, 95% CI: −2.51 to −0.92, p < 0.001).

Fig. 3.

Estimated mean Y-BOCS scores of the ITT sample from LMM correcting for pretreatment differences by treatment group at pretreatment (T0), posttreatment (T1) and 6 months’ (T2), and 12 months’ (T3) follow-up using standard deviation error bars.

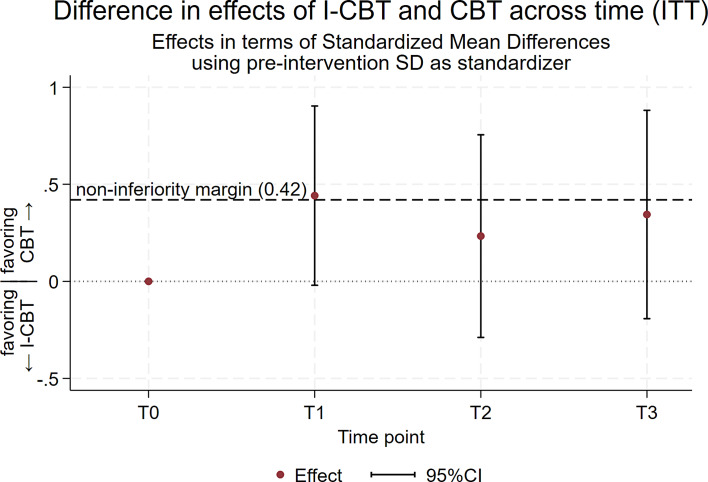

The between-group difference in OCD severity change was 2.05 on the Y-BOCS (95% CI: −0.11–4.22), corresponding to an effect size (Cohen’s d) of 0.44 (95% CI: −0.02–0.91) favoring CBT. This difference, however, was not statistically significant (p = 0.06). Since the 95% CI upper bound of d = 0.91 exceeds the non-inferiority margin of d = 0.42, but no statistically significant difference in Y-BOCS improvement between CBT and I-CBT was found, the I-CBT treatment cannot be conclusively considered inferior or non-inferior to CBT (shown in Fig. 4) [36]. This conclusion holds true at 6 months (d = 0.23; 95% CI: −0.29–0.76; p = 0.38) and 12 months (d = 0.32; 95% CI: −0.23–0.86; p = 0.25).

Fig. 4.

Plotted non-inferiority analyses of the ITT sample with differences (Cohen’s d) and 95% CIs between CBT and I-CBT conditions at posttreatment (T1), 6 months’ (T2) and 12 months’ (T3) follow-up.

For PP analyses, the results of non-inferiority were inconclusive as well. The between-group effect immediately after the intervention was estimated as d = 0.55, 95% CI: (0.04, 1.05), t = 2.120, p = 0.04. Note that the 95% CI shows that there is still some probability that the true treatment difference is less than the non-inferiority margin, even though I-CBT is statistically significantly worse than CBT according to the PP analysis.

Therapists and Compliance

A total of 54 therapists participated in the RCT. CBT was provided by 45 therapists, with an average of 7.5 years of experience in providing CBT for OCD, almost one-third (N = 16) were registered CBT supervisors. I-CBT was provided by 32 therapists, with an average of 0.9 years of experience. Three of them had experience with I-CBT prior to this RCT, 29 did not (except from practicing the treatment prior to participation). Due to the large number of therapists, nearly half of them (N = 24) delivered only one or two treatments during this study, regardless of whether they were offering CBT or I-CBT. The average number of treatments delivered by therapist was 2.2 in the CBT group and 3.1 in the I-CBT group. There were no statistically significant differences in compliance with the treatment protocol by therapists between the CBT and I-CBT groups (CBT: mean = 5.8, SD = 0.6; I-CBT: mean = 5.6, SD = 0.8).

Secondary Outcomes

Treatment Acceptability/Adherence Scale

There was a statistically significant difference between the treatment conditions on treatment tolerability as measured by TAAS in favor of I-CBT at mid-treatment (d= 0.74; 95% CI: 0.44–1.05; p < 0.001) and posttreatment (d = 0.75; 95% CI: 0.39–1.12; p < 0.001), indicating that I-CBT is more tolerable than CBT with a medium to large effect size (see Tables 2, 3). To gain more insight into this difference in tolerability between the treatment conditions, we also examined the individual items of TAAS (see online suppl. Table S4). We found that, compared to CBT, I-CBT was statistically significantly less exhausting (mid-treatment: p = 0.004; posttreatment: p = 0.001), less distressing to participate in (mid-treatment and posttreatment: p < 0.001), and less intrusive (mid-treatment: p = 0.002; posttreatment: p = 0.03). At mid-treatment, participants in the I-CBT group statistically significantly more often indicated that they could adhere to the treatment requirements (p = 0.005). At mid- and posttreatment, participants in the CBT group statistically significantly more often preferred another type of psychological treatment instead of CBT (mid-treatment: p = <0.001; posttreatment: p = 0.001). Posttreatment, participants in the CBT group statistically significantly more often indicated that they were likely to drop out during treatment (p = 0.01).

OVIS, EQ-5D, SDS, BDI, and BAI

Statistically significant within-group improvements were found in the OVIS, EQ-5D, SDS, BDI, and BAI scores. No statistically significant between-group differences were found for these secondary outcomes (see Tables 2, 3).

Response and Remission

Table 4 shows the treatment response and remission rates. No statistically significant differences were found between the two conditions at any time point except for a higher treatment response rate at 12 months’ follow-up in the CBT group (48.5% vs. 42.9%).

Table 4.

Treatment response and remission by treatment condition

| Variables | CBT, %a | I-CBT, %a | Comparison, p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment response | |||

| Posttreatment | 47.5 | 38.8 | 0.10 |

| FU 6 months | 47.5 | 50.0 | 0.86 |

| FU 12 months | 48.5 | 42.9 | 0.04 |

| Remission | |||

| Posttreatment | 21.4 | 37.4 | 0.32 |

| FU 6 months | 37.4 | 31.6 | 0.15 |

| FU 12 months | 33.3 | 35.7 | 0.88 |

CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy; I-CBT, inference-based cognitive behavioral therapy; FU, follow-up.

aPercentage of the ITT sample per condition.

Treatment Dropout

No statistically significant difference was found in the dropout rate, which was 28.3% (28/99) in the CBT group and 22.4% (22/98) in the I-CBT group (p = 0.35).

Serious Adverse Events

No serious adverse events occurred during treatment. During the 6- to 12-month follow-up period, one suicide attempt occurred in the I-CBT group.

Discussion

Both treatments effectively improved OCD symptoms, insight in OCD, QoL, functional impairment, and depressive and anxiety symptoms, persisting up to a year, with no statistically significant differences observed between CBT and I-CBT at posttreatment and at 6-month and 12-month follow-up. The hypothesis that I-CBT is non-inferior to CBT in reducing OCD symptom severity has not been confirmed. After treatment, there was a nonstatistically significant difference in OCD severity improvement between I-CBT and CBT of 2.05 points on the Y-BOCS, favoring CBT, but the 95% CI upper bound exceeded the non-inferiority margin (see Fig. 4), leading to the conclusion that it is inconclusive whether I-CBT is non-inferior to CBT. Furthermore, there was a nonstatistically significant difference in OCD severity change between treatment conditions of 1.09 on the Y-BOCS at 6 months’ follow-up and 1.47 at 12 months’ follow-up, favoring CBT, indicating a clinically marginal difference in symptom severity. Nonetheless, the upper limits of the CIs exceeded the non-inferiority margin of 2 points on the Y-BOCS, rendering the results inconclusive at all assessment points. These findings also indicated that CBT was not superior to I-CBT, which is consistent with the previous research [13, 16, 17]. Together these results may indicate that ERP, at least in some patients, is an important part of OCD treatment. However, another possible explanation for the lack of non-inferiority of I-CBT compared to CBT is that this study was conducted in specialized anxiety disorder and OCD centers with extensive CBT expertise by therapists who had substantially more experience in delivering CBT than I-CBT. Nearly all therapists had experience in providing CBT; in fact, almost 30% of therapists were registered as CBT supervisors, while only 5% had prior experience in delivering I-CBT. As a result, therapists could easily depend on their familiar CBT skills during CBT treatment, but this was not possible with I-CBT treatment. Additionally, it can be challenging for experienced CBT therapists to switch to a different treatment method. Another possible explanation for the inconclusive results is that a longer I-CBT treatment duration may be required to achieve a full effect. This study offered 20 I-CBT sessions, whereas previous studies included 24 to 26 sessions [13, 16, 17, 37]. A longer treatment duration may have led to different results. Taken together, these findings suggest that I-CBT is an effective treatment, even when therapists have minimal experience, without CBT and more experienced therapists showing superior results.

We hypothesized that I-CBT would be more tolerable than CBT because of the lack of an ERP component. Consistent with this, participants reported higher treatment tolerability during and after receiving I-CBT compared to CBT, with a medium to large effect size. Additionally, participants perceived I-CBT as more tolerable than CBT before treatment initiation. The higher treatment tolerability during and after I-CBT treatment was mainly reflected in the perception that I-CBT was less exhausting, less distressing, and less intrusive than CBT, and that participants in the CBT group more frequently expressed a preference to try another type of psychological treatment instead of CBT. These findings align with the fact that I-CBT does not involve deliberate fear activation. Given that I-CBT was not found to be inferior to CBT, this suggests that deliberate fear activation may not be necessary for OCD symptom reduction. However, it should be noted that despite higher tolerability, no better treatment outcome was found in the I-CBT group. Additionally, although I-CBT was better tolerated, a lower dropout rate was not observed in the I-CBT group. The latter is in line with previous studies [13, 16, 17]; nonetheless to gain a better understanding, we explored reasons for treatment dropout in both conditions. In the CBT group, there were 21 treatment dropouts (along with seven participants who were solely study participation dropouts, but continued with treatment), and in the I-CBT group, there were 18 treatment dropouts (next to four study participation dropouts). Among those in the CBT condition, 19% (4/21) of dropouts were attributed to refusing CBT or finding CBT too confronting compared to 0% in I-CBT. Additionally, within the CBT group, 38% (8/21) of dropouts were due to changes in medication, as opposed to 6% (1/18%) in the I-CBT group. This difference cannot be attributed to the severity of the symptoms, as this was equal after randomization. The higher percentage of medication changes in the CBT group may reflect a preference for treatment other than CBT. In the I-CBT group, 44% (8/18) of the participants dropped out due to external circumstances, such as life events or timing of treatment not being suitable, compared to 5% (1/21) in the CBT group. Therefore, while no lower dropout rate was found in the I-CBT group, it seems that there were different reasons for dropout. Future research should aim to qualitatively explore the specific reasons for dropping out of I-CBT. Together, these findings suggest that I-CBT is an effective treatment, which seems distinct from CBT, specifically in the sense that it does not involve any ERP components, and may be a suitable alternative treatment option for patients with OCD who are hesitant to start or continue CBT because of fear associated with exposure therapy.

The strengths of this study include adherence to CONSORT guidelines for non-inferiority trials, a large sample size, inclusion/exclusion criteria aimed at maximizing generalizability, the use of psychometrically sound measures, and a 12-month follow-up period. However, this study had several limitations. First, as mentioned before, therapists had far more experience with CBT than I-CBT, potentially impacting our findings. The novelty of I-CBT inevitably results in a scarcity of experienced therapists. To address this, new therapists in I-CBT should treat a minimum of 2 patients under supervision before participating in trials. Additionally, future research should limit the number of therapists in each group to allow for more experience with new treatments. Second, therapist allegiance was not considered, potentially introducing a bias. Therapist allegiance reflects therapists’ beliefs that one therapy is more effective than another and might introduce bias in a “crossed therapist” design (e.g., the same therapist delivering more than one treatment) [38]. Future research should assess therapist allegiance and assign therapists to the treatments they perceive as superior. Third, this study was conducted partly during the COVID-19 pandemic period. Consequently, some participants in I-CBT and CBT received face-to-face treatment and measurements in a non-COVID-19 period, while others were partially or fully treated and measured via video conference due to pandemic restrictions. It is unclear how this may have affected the outcome. Fourth, the assessors were not blinded to the assessment time points, which might have influenced their assessments of improvements. However, because they were blinded to the treatment conditions, the comparative ratings between the conditions were not affected. Finally, the current study did not include a control group, making it challenging to definitively determine the effectiveness of treatment interventions. However, since treatment as usual (including usual care/management, waiting list and no treatment) is largely ineffective for patients with OCD [39], this suggests that the improvements observed in both treatment groups during this study are unlikely to be due to the natural progression of OCD. Despite these limitations, to our knowledge, this study is the first to examine the non-inferiority of I-CBT to CBT for the treatment of OCD. Further research is needed to build upon our findings, including exploring the differences between CBT and I-CBT in their working mechanisms and clinical characteristics predicting treatment outcomes.

In conclusion, whether I-CBT is non-inferior to CBT in terms of OCD symptom severity remains inconclusive. I-CBT was found to be an effective treatment, even when therapists have minimal experience, being more tolerable and less distressing for patients compared to CBT, while achieving good results. This suggests that I-CBT might serve as an alternative for patients hesitant to begin or continue CBT because of fear of its anxiety-provocative exposure and response prevention component.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participating trial sites for their help with recruitment and all patients who participated in the trial. We also thank all dedicated therapists and research assessors who contributed to this study.

Statement of Ethics

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the VU University Medical Center, reported according to the CONSORT statement, and registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03929081). All the participants provided written informed consent.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

This research was supported by a grant from ZonMW (Grant No. 636310004). The funder had no role in the design, data collection, data analyses, interpretation, or reporting of the study.

Author Contributions

N.W. was responsible for the design and conduct of the study, training and supervision of the research assessors, and statistical analyses, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. P.O. was responsible for the concept and design of the study, funding acquisition, supervision of I-CBT therapists, coordination and supervision of the trial site, supervision of all study stages, and critical revision of the manuscript. A.W.H. was responsible for the design and statistical analysis and critically revised the manuscript. O.A.H. was responsible for the concept and design of the study, funding acquisition, coordinated and supervised the trial site, supervised all study stages, and critically revised the manuscript. H.J.G.M.M. critically revised the manuscript. M.K., D.C.C., K.R.J.S., S.M.E., and T.O. coordinated and supervised the trial sites and critically revised the manuscript. A.J.L.M.B. was responsible for the study concept and design, funding acquisition, coordinated and supervised the trial site, supervised all the study stages, and critically revised the manuscript. A.B. was responsible for conducting the study and for critically revising the manuscript. H.A.D.V. was the principal investigator and was responsible for the concept and design of the study, funding acquisition, training and supervision of I-CBT therapists, supervision in all study stages, and critical revision of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the interpretation, review, and editing of the manuscript and approved the submission of the final manuscript.

Funding Statement

This research was supported by a grant from ZonMW (Grant No. 636310004). The funder had no role in the design, data collection, data analyses, interpretation, or reporting of the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions but are available from the corresponding author (N.W.) upon reasonable request.

Supplementary Material.

Supplementary Material.

Supplementary Material.

Supplementary Material.

Supplementary Material.

Supplementary Material.

References

- 1. Eisen JL, Mancebo MA, Pinto A, Coles ME, Pagano ME, Stout R, et al. Impact of obsessive-compulsive disorder on quality of life. Compr Psychiatry. 2006;47(4):270–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Visser HA, van Oppen P, van Megen HJ, Eikelenboom M, van Balkom AJ. Obsessive-compulsive disorder; chronic versus non-chronic symptoms. J Affect Disord. 2014;152–154(1):169–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cicek E, Cicek IE, Kayhan F, Uguz F, Kaya N. Quality of life, family burden and associated factors in relatives with obsessive–compulsive disorder. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35(3):253–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Remmerswaal KCP, Batelaan NM, Hoogendoorn AW, van der Wee NJA, van Oppen P, van Balkom AJLM. Four-year course of quality of life and obsessive–compulsive disorder. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2020;55(8):989–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Remmerswaal KCP, Batelaan NM, Smit JH, van Oppen P, van Balkom AJLM. Quality of life and relationship satisfaction of patients with Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. J Obsessive Compuls Relat Disord. 2016;11:56–62. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Koran LM, Gregory Hanna CL, Hollander E, Nestadt G, Blair Simpson H. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. 2010. [Internet] Available from: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Clinical guideline [CG31] . Obsessive-compulsive disorder and body dysmorphic disorder: treatment. British Psychological Society; 2005. Available from: https: //www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg31 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Öst LG, Havnen A, Hansen B, Kvale G. Cognitive behavioral treatments of obsessive-compulsive disorder. A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies published 1993-2014. Clin Psychol Rev. 2015;40:156–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rosa-Alcázar AI, Sánchez-Meca J, Gómez-Conesa A, Marín-Martínez F. Psychological treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008;28(8):1310–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Spencer SD, Stiede JT, Wiese AD, Guzick AG, Cervin M, McKay D, et al. Things that make you go Hmm: myths and misconceptions within cognitive-behavioral treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Obsessive Compuls Relat Disord. 2023;37:100805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Leeuwerik T, Cavanagh K, Strauss C. Patient adherence to cognitive behavioural therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Anxiety Disord. 2019;68:102135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mancebo MC, Eisen JL, Sibrava NJ, Dyck IR, Rasmussen SA. Patient utilization of cognitive-behavioral therapy for OCD. Behav Ther. 2011;42(3):399–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. O’Connor KP, Aardema F, Bouthillier D, Fournier S, Guay S, Robillard S, et al. Evaluation of an inference-based approach to treating obsessive-compulsive disorder. Cogn Behav Ther. 2005;34(3):148–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Baraby LP, Wong S, Radomsky A, Aardema F. Dysfunctional reasoning processes and their relationship with feared self-perceptions and obsessive-compulsive symptoms: an investigation with a new task-based measure of inferential confusion. J Obsessive Compuls Relat Disord. 2021;28:100593. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Aardema F, O’Connor KP, Emmelkamp PMG. Inferential confusion and obsessive beliefs in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Cogn Behav Ther. 2006;35(3):138–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Visser HA, Van Megen H, Van Oppen P, Eikelenboom M, Hoogendorn AW, Kaarsemaker M, et al. Inference-based approach versus cognitive behavioral therapy in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder with poor insight: a 24-session randomized controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom. 2015;84(5):284–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Aardema F, Bouchard S, Koszycki D, Lavoie ME, Audet JS, O’Connor K. Evaluation of inference-based cognitive-behavioral therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a multicenter randomized controlled trial with three treatment modalities. Psychother Psychosom. 2022;91(5):348–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Aardema F, O’Connor KP, Delorme ME, Audet JS. The inference-based approach (IBA) to the treatment of obsessive–compulsive disorder: an open trial across symptom subtypes and treatment-resistant cases. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2017;24(2):289–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. O’Connor K, Koszegi N, Aardema F, van Niekerk J, Taillon A. An inference-based approach to treating obsessive-compulsive disorders. Cogn Behav Pract. 2009;16(4):420–9. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Clark DA, Beck AT. Cognitive therapy of anxiety disorders: science and practice. Cognitive therapy of anxiety disorders: science and practice. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 2010; p. 628–ix. [Google Scholar]

- 21. van Oppen P, van Balkom AJLM, Smit JH, Schuurmans J, van Dyck R, Emmelkamp PMG. Does the therapy manual or the therapist matter most in treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder? A randomized controlled trial of exposure with response or ritual prevention in 118 patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(9):1158–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wjbw FMB, Krs SRL. Structured clinical Interview for DSM‐5 disorders, clinician version (SCID‐5‐CV). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, Mazure C, Delgado P, Heninger GR, et al. The Yale–Brown obsessive compulsive scale II validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46(11):1012–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mataix-Cols D, Fernandez de La Cruz L, Nordsletten AE, Lenhard F, Isomura K, Simpson HB. Towards an international expert consensus for defining treatment response, remission, recovery and relapse in obsessive-compulsive disorder. World Psychiatr. 2016;15:80–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Neziroglu F, McKay D, Yaryura-Tobias JA, Stevens KP, Todaro J. The overvalued ideas scale: development, reliability and validity in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behav Res Ther. 1999;37(9):881–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Milosevic I, Levy HC, Alcolado GM, Radomsky AS. The treatment acceptability/adherence scale: moving beyond the assessment of treatment effectiveness. Cogn Behav Ther. 2015;44(6):456–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. EuroQol Group . EuroQol: a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16(3):199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sheehan DV. The sheehan disability scales. New York: Scribner; 1983; p. 151. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56(6):893–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Devilly GJ, Borkovec TD. Psychometric properties of the credibility/expectancy questionnaire. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2000;31(2):73–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schumi J, Wittes JT. Through the looking glass: understanding non-inferiority. Trials. 2011;12:106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Olatunji BO, Davis ML, Powers MB, Smits JAJ. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a meta-analysis of treatment outcome and moderators. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47(1):33–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. White IR, Carpenter J, Horton NJ. Including all individuals is not enough: lessons for intention-to-treat analysis. Clin Trials. 2012;9(4):396–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Szende A, Janssen B, Cabases J. Self-reported population health: an international perspective based on EQ-5D. 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Pocock SJ, Evans SJW, Altman DG, CONSORT Group . Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: extension of the CONSORT 2010 statement. JAMA. 2012;308(24):2594–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Aardema F, O’Connor KP, Delorme ME, Audet JS. The inference-based approach (IBA) to the treatment of obsessive–compulsive disorder: an open trial across symptom subtypes and treatment-resistant cases. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2017;24(2):289–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Falkenström F, Markowitz JC, Jonker H, Philips B, Holmqvist R. Can psychotherapists function as their own controls? Meta-analysis of the crossed therapist design in comparative psychotherapy trials. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(5):482–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gava I, Barbui C, Aguglia E, Carlino D, Churchill R, De Vanna M, et al. Psychological treatments versus treatment as usual for obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007(2):CD005333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions but are available from the corresponding author (N.W.) upon reasonable request.