Abstract

Sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors are a class of drugs used in the clinical management of patients with type 2 diabetes, and their prescriptions have been increasing in recent years. Herein, we performed a retrospective analysis of seasonal variation in SGLT2 inhibitor-associated adverse events recorded in the Japanese Adverse Drug Event Report (JADER) database, an adverse event reporting database which reflects real-world clinical practice. To this end, seasonal variations in SGLT2 inhibitor-related dehydration, cerebral infarction, urinary tract infection, and ketoacidosis were analyzed. Six SGLT2 inhibitors prescribed in Japan (ipragliflozin, empagliflozin, luseogliflozin, canagliflozin, dapagliflozin, and tofogliflozin) were included. The reporting ratio (RR) for SGLT2 inhibitor adverse events per month in the JADER database from April 2014 to December 2023 was determined. The RR for dehydration-related adverse events was highest in the summer months of July and August, as well as in the winter months of December, January, and February. The highest RR for cerebral infarction was in February. No association with seasonal variations in the occurrence of ketoacidosis related to dehydration was observed. Healthcare providers should take adequate precautions against dehydration caused by SGLT2 inhibitors, not only in summer but also in winter. These findings are instructive and informational for health care professionals involved in diabetes care.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-81698-z.

Keywords: Sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors, Adverse events, Seasonal variation, Dehydration, Type 2 diabetes mellitus

Subject terms: Risk factors, Lifestyle modification

Introduction

Sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors lower blood glucose levels independent of insulin by inhibiting glucose reabsorption in the proximal tubules and increasing urinary glucose excretion1,2. Their antihyperglycemic effects are generally not adequate for use as monotherapy; however, their insulin-independent mechanism make them effective as adjunctive therapy when monotherapy with metformin is ineffective1. SGLT2 inhibitors are approved for the treatment of type 2 diabetes when glycemic control is not improved by diet or lifestyle modifications. In addition, they have recently been approved by both the European Medicines Agency and U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of heart failure with a reduced ejection fraction with or without diabetes3. Therefore, SGLT2 inhibitors have clinical significance in treating patients with type 2 diabetes, especially those with underlying cardiovascular or fatty liver disease, and their prescription volumes are increasing worldwide.

The adverse events of SGLT2 inhibitor administration include diabetic ketoacidosis, acute kidney injury, pyelonephritis, volume depletion, genital fungi, and urinary tract infection3–7. The Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA), an institution responsible for ensuring the efficacy, safety, and quality of pharmaceuticals and medical devices in Japan, stated that a causal relationship between SGLT2 inhibitors and dehydration cannot be ruled out. In 2015, the PMDA ordered that the package inserts for six SGLT2 inhibitors be revised to include the following information in the [cautious administration] section: “patients prone to dehydration (patients with extremely poor glycemic control, elderly patients, patients on diuretics, etc.).” In addition, the following information for healthcare professionals was to be clearly stated in the package insert: (1) instruct patients to maintain adequate hydration and observe them closely; (2) if symptoms such as thirst, polyuria, frequent urination, or decreased blood pressure are suspected to indicate dehydration, take appropriate measures such as withdrawal of medication or replacement of fluids; and (3) since there have been reports of thromboembolism, including stroke, following dehydration, take extra care to avoid such events. Although healthcare providers are likely to be aware of SGLT2 inhibitor-induced dehydration, the effect of the season on dehydration-related adverse events in real-world clinical practice remains unclear. This study aimed to verify whether dehydration-related adverse events associated with SGLT2 inhibitors are adequately managed, and to alert the public of the possible occurrences when necessary.

The Japanese Adverse Drug Event Report (JADER) database, made public by the PMDA, is a collection of spontaneous adverse event reporting data from actual clinical practice in Japan, in which information on the date of occurrence of adverse events is entered. Sakaeda et al. used the JADER database to suggest an association between the SGLT2 inhibitor ipragliflozin and severe skin disorders8. Nakao et al. revealed seasonal variations in drug-induced photosensitivity using the JADER database9. Marrero et al. analyzed various adverse event reports using the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) to identify seasonal and regional variations, including photosensitivity10. In the current study, the JADER database was used to analyze seasonal variations in the adverse events of SGLT2 inhibitors, including dehydration and urinary tract infections, adverse events characteristic of SGLT2 inhibitors, ketoacidosis related to dehydration, and cerebral infarction, of which dehydration is known to be an adverse factor.

Materials and methods

Data source

Adverse event reports are collected and fully anonymized by the PMDA to form the JADER database (www.pmda.go.jp). The database consists of four data tables: patient demographic information (DEMO), drug information (DRUG), adverse events (REAC), and primary disease (HIST). In the “drug” table, each drug is assigned a code of “suspected,” “concomitant,” or “interaction.” In this retrospective study, data identified as “suspected” were analyzed as drug involvement. A relational database was constructed by integrating the four tables using FileMaker Pro Advanced 13 (FileMaker Inc. Santa Clara, CA).

In Japan, the SGLT2 inhibitors ipragliflozin, empagliflozin, luseogliflozin, canagliflozin dapagliflozin, and tofogliflozin were launched in April 2014, February 2015, May 2014, September 2014, May 2014, and May 2014, respectively; therefore, the study period was from April 2014 to March 2023.

Drug selection

Six SGLT2 inhibitors (ipragliflozin, empagliflozin, luseogliflozin, canagliflozin, dapagliflozin, and tofogliflozin) and a combination of SGLT2 and dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4) inhibitors (ipragliflozin and sitagliptin, empagliflozin and linagliptin, canagliflozin and teneligliptin) used in Japan as of 2023 were included.

Adverse events selection

Adverse events in the JADER database were defined based on the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA; www.meddra.org/how-to-use/support-documentation/japanese) version 27.0. For the extraction of cases from the JADER database, the preferred term (PT) of dehydration (PT code: 10012174), cerebral infarction (PT code: 10008118), urinary tract infection (PT code: none), and i_ketoacidosis [diabetic ketoacidosis (PT code: 10012671), euglycaemic diabetic ketoacidosis (PT code: 10080061), ketoacidosis (PT code: 10023379)] were analyzed.

Time series analysis

The reporting ratio (RR) was calculated as the number of adverse events reported for each target drug in each month divided by the total number of adverse event reports in each month. JMP Pro version 17 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used to visualize time-series data.

Results

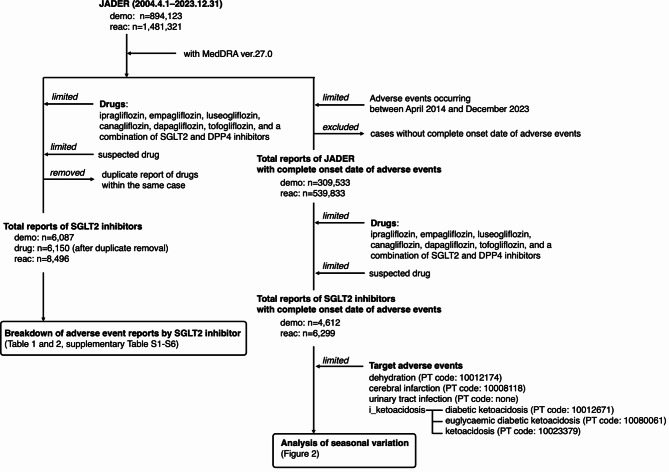

The total number of JADER reports between April 2014 and December 2023 was 539,833 (Fig. 1). The number of reports by sex, age, adverse events, and reporting month are summarized in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2. Since information on age is entered every 10 years in the JADER database, it is not possible to obtain an exact average age. The adverse events associated with SGLT2 inhibitors are summarized in Table 1. The number of adverse events for ipragliflozin, empagliflozin, luseogliflozin, canagliflozin, dapagliflozin, and tofogliflozin was 2130, 998, 489, 803, 1279, and 451, respectively (Table 1). The reports for dehydration, i_ketoacidosis, cerebral infarction, and urinary tract infection for the six SGLT2 inhibitors were 415, 1049, 474, and 213 respectively (Table 2, Supplementary Table S3–S8).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of analysis.

Table 1.

The number of adverse event reports of SGLT2 inhibitors.

| Type of SGLT2 inhibitors | Drugs | Case (n) | Reporting ratio (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 6150 | - | |

| Canagliflozin | Canagliflozin Hydrate | 661 | 10.75 |

| Canagliflozin Hydrate/Teneligliptin Hydrobromide Hydrate | 142 | 2.31 | |

| Dapagliflozin | Dapagliflozin Propylene Glycolate Hydrate | 1279 | 20.80 |

| Empagliflozin | Empagliflozin | 919 | 14.94 |

| Empagliflozin/Linagliptin | 79 | 1.29 | |

| Ipragliflozin | Ipragliflozin L-Proline | 1984 | 32.26 |

| Ipragliflozin L-Proline/Sitagliptin Phosphate Hydrate | 143 | 2.33 | |

| Ipragliflozin L-Proline | 2 | 0.03 | |

| Ipragliflozin | 1 | 0.02 | |

| Luseogliflozin | Luseogliflozin Hydrate | 489 | 7.95 |

| Tofogliflozin | Tofogliflozin Hydrate | 451 | 7.33 |

Table 2.

The number of adverse events of SGLT2 inhibitors (total).

| Preferred term code | Preferred term name | Case (n) | Reporting ratio (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 8496 | - | |

| 10008118 | Cerebral infarction | 474 | 5.58 |

| 10012671 | Diabetic ketoacidosis | 430 | 5.06 |

| 10012174 | Dehydration | 415 | 4.88 |

| 10080061 | Euglycaemic diabetic ketoacidosis | 389 | 4.58 |

| 10023379 | Ketoacidosis | 230 | 2.71 |

| - | Urinary tract infection | 213 | 2.51 |

| 10020993 | Hypoglycaemia | 207 | 2.44 |

| - | Pyelonephritis | 191 | 2.25 |

| 10062237 | Renal impairment | 147 | 1.73 |

| 10000891 | Acute myocardial infarction | 131 | 1.54 |

| 10069339 | Acute kidney injury | 130 | 1.53 |

| 10028596 | Myocardial infarction | 99 | 1.17 |

| 10037844 | Rash | 97 | 1.14 |

| 10023676 | Lactic acidosis | 86 | 1.01 |

| 10007554 | Cardiac failure | 83 | 0.98 |

| 10013687 | Drug eruption | 81 | 0.95 |

| 10051078 | Lacunar infarction | 74 | 0.87 |

| - | Acute pyelonephritis | 74 | 0.87 |

| 10034277 | Pemphigoid | 70 | 0.82 |

| 10023391 | Ketosis | 69 | 0.81 |

| 10040047 | Sepsis | 66 | 0.78 |

| - | Death | 63 | 0.74 |

| - | Decreased appetite | 61 | 0.72 |

| 10002383 | Angina pectoris | 57 | 0.67 |

| 10019670 | Hepatic function abnormal | 54 | 0.64 |

| - | Others | 4505 | 53.02 |

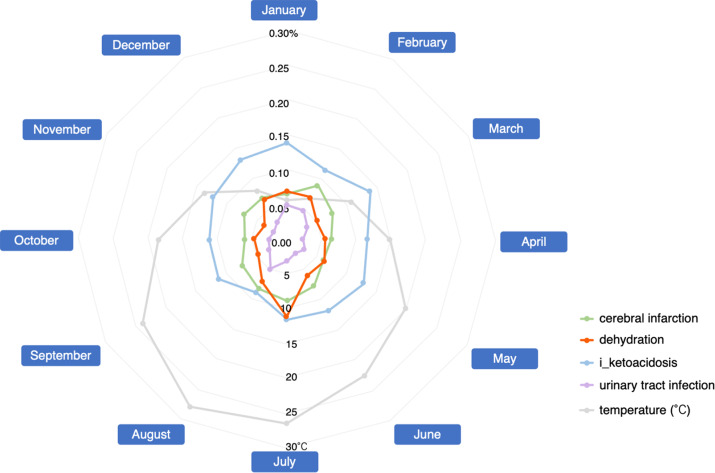

Figure 2 shows the monthly RR for SGLT2 inhibitor use (Fig. 2, supplementary Table S9). Dehydration was highest in the summer month of July, followed by August. High occurrences of dehydration were also reported during the winter months of December, January, and February. The highest RR for cerebral infarction was reported in February, followed by July. Ketoacidosis reports were constant throughout the year. The RR for urinary tract infection was lower than that for dehydration, cerebral infarction, and ketoacidosis, with higher percentages reported in August, January, and February.

Fig. 2.

Lader chart of the reporting ratio of SGLT2 inhibitor-related adverse events and average temperatures in Japan.

Discussion

In the JADER database, all SGLT2 inhibitors were associated with a high RR for cerebral infarction, dehydration, ketoacidosis, and urinary tract infection. Our results showed that the RR for SGLT2 inhibitor dehydration was highest in July. Average temperatures in Japan exceed 25 °C in summer, averaging 26.4 °C in July and 27.6 °C in August, and are as low as 5.7 °C and 6.8 °C in winter (January and February, respectively)11. The Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Ministry of the Environment, and Japan Meteorological Agency issued warnings to be aware of heat stroke and dehydration during the summer season. However, only a few detailed studies have been conducted on year-round dehydration in Japan. A retrospective study analyzed dehydration after overnight fasting in adults aged 65 years and older with less advanced kidney disease12. In the report, the spring group showed the highest levels of plasma osmolality (306.1 ± 3.9 mOsm/L), urine specific gravity (1.0172 ± 0.0058), and urine specific gravity prevalence ≥ 1.020 (34.0%). However, seasonal differences were clinically mild, with > 90% of participants showing plasma osmolality ≥ 300 mOsm/L and a tendency toward dehydration in all four seasons12. Therefore, it is reasonable to expect that the RR for dehydration, which is suspected to be related to taking SGLT2 inhibitors, would be higher in July and August which are the hot summer months.

Interestingly, the RR for dehydration tended to be relatively high in the winter months of December, January, and February, indicating a bimodal relationship between summer and winter. In Japan, people have been warned of hidden dehydration due to insufficient fluid intake during winter. In a study of seasonal changes in body water content in 23 residents of a care house, decreases in total, intracellular, and extracellular water content were observed in winter compared with summer13. Higher serum osmolality levels were observed in fall and winter than in summer in studies involving forestry workers14. The percentage of dehydrated workers with serum osmolality ≥ 290 mOsmol/kg H2O was significantly higher in winter than in summer14. In winter, dehydration is difficult to detect and awareness of fluid intake is lower than in summer. Therefore, it is necessary for healthcare providers to take adequate precautions against dehydration caused by SGLT2 inhibitors, not only in summer but also in winter.

The percentage of SGLT2 inhibitor-related cerebral infarction was highest in February, followed by July. Dehydration is a common risk factor for thrombosis and embolism15. Ischemic stroke is caused by hypoperfusion, renal dysfunction, and hypercoagulability associated with dehydration16–18. Our results suggested a relationship between SGLT2 inhibitor-induced dehydration and cerebral infarction. The association between temperature (cold or hot) and cardiovascular mortality is well documented. In addition to water loss, electrolyte and acid-base imbalances due to dehydration have been suggested to contribute to increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality during hot and cold temperatures19. Temperature-related changes in hydration status have been suggested to be responsible for increased cardiovascular mortality and morbidity under hot or cold conditions. Risk factors for cerebral infarction include hypertension, arrhythmia, diabetes, smoking, and obesity, with hypertension being a particularly important factor15. It is known that blood pressure tends to decrease in spring and summer when temperatures rise and increase in the fall and winter when temperatures drop20. Thus, our results on cardiovascular disease and related cerebral infarction may be partially influenced by simple seasonal variations. However, statistical tests could not be presented in the present study. A more detailed study would require an accumulation of cases.

Although SGLT2 inhibitors lower blood glucose levels by inhibiting glucose reabsorption, they increase urinary glucose levels, which may be associated with the aforementioned urinary tract infection adverse event. The RR for urinary tract infection was higher in August, January, and February. Subgroup analysis of genital tract infections showed that being male, being aged 40–64 years, having ischemic heart disease, and concomitant use of biguanides increased the risk of developing this adverse event21. In contrast, cohort studies have shown that SGLT2 inhibitors do not influence the risk of developing a urinary tract infection22. In our study, urinary tract infections were reported less frequently monthly, and the effect of seasonal variation was not evaluated.

SGLT2 inhibitors decrease blood glucose and insulin levels and increase the glucagon/insulin ratio by increasing urinary glucose excretion. Consequently, the liver produces more glucose to compensate for the decrease in blood glucose, lipolysis is accelerated in adipose tissue, and the free fatty acids produced are converted to ketone bodies in the liver. Under these circumstances, triggers such as inappropriate insulin reduction or interruption, influenza-like symptoms, gastroenteritis, recent surgery, extreme carbohydrate deprivation, and dehydration can lead to a rapid increase in blood ketones and acidic substances and the development of ketoacidosis4. With the exception of dehydration, patient background was not considered to be affected by the season. We did not find any association between ketoacidosis and seasonal variations in the development of adverse events associated with dehydration. The reason for this is unknown; however, it may be because “diabetic ketoacidosis,” “euglycaemic diabetic ketoacidosis,” and “ketoacidosis” were evaluated together as i_ketoacidosis.

In Table 1, the number of adverse event reports for three SGLT2 inhibitors is higher than their combination with dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4) inhibitors. Canagliflozin, empagliflozin, and ipragliflozin were launched in 2014, 2015, and 2014 in Japan, respectively23–25. Combinations of these three SGLT2 inhibitors with DPP4 inhibitors were launched in 2017, 2018, and 2018, respectively26–28. The difference in the timing of the launch of SGLT2 inhibitor monotherapy and combination drugs was only 3–4 years, and the large difference in the number of reports of SGLT2 inhibitor monotherapy and combination drugs may be due to the fact that monotherapy continued to be prescribed in clinical practice even after the combination drugs were launched.

Spontaneous reporting system (SRS) is affected by over-reporting, under-reporting, missing data, exclusion of healthy subjects, and the presence of confounding factors29. In addition, external factors such as the release of safety information by regulatory authorities and market trends may influence adverse event reports, which should be interpreted with caution. Although there have been reports on the use of JADER data in analyzing trend variation in time series of adverse event reports using the Mann–Kendall test and Pettitt’s test30,31, it was difficult to apply this method to a cyclical time series analysis such as the present one. The autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) model is a unique method of time-series analysis that takes into account structural or cyclical variations over time and is therefore considered to be an analytical method that meets the objectives of the current study. However, we could not perform such an analysis in this study because of the small number of reports for each month in each year. Adopting this model would be of value in future studies. Despite these inherent SRS limitations, the present results are of value to healthcare providers and patients such as the elderly and those suffering from chronic kidney disease because the occurrence of SGLT2 inhibitor-related dehydration and cerebral infarction in real-world clinical practice is associated with seasonal variations.

Conclusion

In Japanese clinical practice, the RR for dehydration related to SGLT2 inhibitors is highest in the summer months of July and August, as well as in winter (December, January, and February). The highest RR for cerebral infarction is in February. These findings are instructive and informational for health care professionals involved in diabetes care.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge Dr Mayumi Yamamoto, Professor of Health Administration Center, Gifu University, for her help in interpreting the significance of the results of this study.

Author contributions

K.M., F.G., M.M., and M.N. contributed to the overall study concept and design. K.M., F.G., M.M., and M.N. wrote the manuscript. K.M., F.G., M.M., K.M, S.H., N.I., M.Y., Y.N, T.Y., and K.S. performed data extraction and statistical analysis. S.N., K.S., H.T., H.T., M.I., and K.I. revised the article to provide meaningful intellectual content. All authors have read and reviewed the manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not sought for this study because the study was a database-related observational study which did not directly involve any research subjects. All results were obtained from data openly available online from the PMDA website (www.pmda.go.jp). All data from the JADER database were fully anonymized by the relevant regulatory authority before we accessed them.

Our research does not fall within the purview of any of the following laws and guidelines: “Clinical Trials Act (Act No. 16 of April 14, 2017),” “Act on Securing Quality, Efficacy and Safety of Products Including Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices (Law number: Act No. 145 of 1960, Last Version: Amendment of Act No. 50 of 2015),” “Guideline for good clinical practice E6 (R1), https://www.pmda.go.jp/int-activities/int-harmony/ich/0076.html,” “Ethical guidelines for human genome and gene analysis research, https://www.mhlw.go.jp/general/seido/kousei/i-kenkyu/genome/0504sisin.html,” and “Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects, https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/hokabunya/kenkyujigyou/i-kenkyu/index.html.” Therefore, it is not subject to ethical examination. The study was an observational study without any research subjects. No consent to participate was required due to the retrospective nature of this study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bryce, S. & Gordon, M. Sodium-glucose cotranspoter-2(SGLT2) inhibitors: a clinician’s guide. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes.12, 2125–2136 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Komoroski, B. et al. Dapagliflozin, a novel SGLT2 inhibitor, induces dose-dependent glucosuria in healthy subjects. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther.85, 520–526 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caparrotta, T. M. et al. Sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) exposure and outcomes in type 2 diabetes: A systematic review of population-based observational studies. Diabetes Ther.12, 991–1028 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blau, J. E., Tella, S. H., Taylor, S. I. & Rother, K. I. Ketoacidosis associated with SGLT2 inhibitor treatment: analysis of FAERS data. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev.33, e2924 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fadini, G. P., Bonora, B. M. & Avogaro, A. SGLT2 inhibitors and diabetic ketoacidosis: data from the FDA adverse event reporting system. Diabetologia60, 1385–1389 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tuttle, K. R. et al. SGLT2 inhibition for CKD and cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes: Report of a scientific workshop sponsored by the national kidney foundation. Diabetes70, 1–16 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ueda, P. et al. Sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors and risk of serious adverse events: Nationwide register based cohort study. BMJ363, k4365 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sakaeda, T. et al. Susceptibility to serious skin and subcutaneous tissue disorder and skin tissue distribution of sodium-dependent glucose co-transporter type-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors. Int. J. Med. Sci.15, 937–943 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakao, S. et al. Evaluation of drug-induced photosensitivity using the Japanese adverse drug Event Report (JADER) database. Biol. Pharm. Bull.40, 2158–2165 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marrero, O., Hung, E. Y. & Hauben, M. Seasonal and geographic variation in adverse event reporting. Drugs Real. World Outcomes. 3, 297–306 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Japan Meteorological Agency. Tokyo (Japan) monthly average of daily mean temperature (°C), https://www.data.jma.go.jp/obd/stats/etrn/view/monthly_s3.php?prec_no=44_no=47662, cited 29 June, 2024.

- 12.Tanaka, S. et al. Seasonal variation in hydration status among community-dwelling elderly in Japan. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int.20, 904–910 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsutsumi, M., Sato, M. & Kobayashi, T. A study on seasonal changes of the amount of body water of elderly people in a care house in summer and winter using the electrical impedance method. Bull. School Nurs. Yamaguchi Prefectural Univ.8, 19–23 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joanna, O., Magdalena, M. & Paweł, T. Hydration status in men working in different thermal environments: A pilot study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19, 5627 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fukunaga, A., Koyama, H., Fuse, T. & Haraguchi, A. The onset of cerebral infarction may be affected by differences in atmospheric pressure distribution patterns. Front. Neurol.14, 1230574 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhatia, K., Mohanty, S., Tripathi, B. K., Gupta, T. B. & Mittal, M. K. Predictors of early neurological deterioration in patients with acute ischemic stroke with special reference to blood urea nitrogen (BUN)/creatinine ratio and urine specific gravity. Indian J. Med. Res.41, 299–307 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jauch, E. C. et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: A guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke44, 870–947 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kelly, J. et al. Dehydration and venous thromboembolism after acute stroke. QJM97, 293–296 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lim, Y. H., Park, M. S., Kim, Y., Kim, H. & Hong, Y. C. Effects of cold and hot temperature on dehydration: A mechanism of cardiovascular burden. Int. J. Biometeorol.59, 1035–1043 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Narita, K., Hoshide, S. & Kario, K. Seasonal variation in blood pressure: Current evidence and recommendations for hypertension management. Hypertens. Res.44, 1363–1372 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Imai, T. et al. Risk of urogenital bacterial infection with sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors: A retrospective cohort study using a claims database. Diabetes Ther.15, 1821–1830 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dave, C. V. et al. Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors and the risk for severe urinary tract infections: A population-based cohort study. Ann. Intern. Med.171, 248–256 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency, Canaglu® (canagliflozin) (Approval. (2014). https://www.pmda.go.jp/PmdaSearch/iyakuDetail/ResultDataSetPDF/400315_3969022F1029_1_22, cited 14 September, 2024.

- 24.Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency, Jardiance® (empagliflozin) (Approval: 2015), (2024). https://www.pmda.go.jp/PmdaSearch/iyakuDetail/ResultDataSetPDF/650168_3969023F1023_1_17, cited 14.

- 25.Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency, Suglat® (ipragliflozin) (Approval: 2014), (2024). https://www.pmda.go.jp/PmdaSearch/iyakuDetail/ResultDataSetPDF/800126_3969018F1022_1_14, cited 14.

- 26.Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency, Canalia® (canagliflozin, teneligliptin) combination tablets (Approval: 2017), (2024). https://www.pmda.go.jp/PmdaSearch/iyakuDetail/ResultDataSetPDF/400315_3969106F1028_1_14, cited 14.

- 27.Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency, Tradiance® (empagliflozin, linagliptin) combination tablets (Approval: 2018), (2024). https://www.pmda.go.jp/PmdaSearch/iyakuDetail/ResultDataSetPDF/650168_3969108F1027_1_04, cited 14.

- 28.Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency, Sujanu® (ipragliflozin, sitagliptin) combination tablets (Approval: 2018), (2024). https://www.pmda.go.jp/PmdaSearch/iyakuDetail/ResultDataSetPDF/170050_3969107F1022_1_09, cited 14.

- 29.Evans, S. J., Waller, P. C. & Davis, S. Use of proportional reporting ratios (PRRs) for signal generation from spontaneous adverse drug reaction reports. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf.10, 483–486 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ichihara, N. et al. Analysis of metformin-associated lactic acidosis using Japanese adverse drug event report database. BPB Rep.7, 76–80 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sakurai, S. et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy analyzed using the Japanese adverse drug Event Report database. J. Neurol. Sci.455, 122789 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.