Abstract

Inhibiting prepotent responses in the face of external stop signals requires complex information processing, from perceptual to control processing. However, the cerebral circuits underlying these processes remain elusive. In this study, we used neuroimaging and brain stimulation to investigate the interplay between human brain regions during response inhibition at the whole-brain level. Magnetic resonance imaging suggested a sequential four-step processing pathway: initiating from the primary visual cortex (V1), progressing to the dorsal anterior insula (daINS), then involving two essential regions in the inferior frontal cortex (IFC), namely the ventral posterior IFC (vpIFC) and anterior IFC (aIFC), and reaching the basal ganglia (BG)/primary motor cortex (M1). A combination of ultrasound stimulation and time-resolved magnetic stimulation elucidated the causal influence of daINS on vpIFC and the unidirectional dependence of aIFC on vpIFC. These results unveil asymmetric pathways in the insular-prefrontal cortex and outline the macroscopic cerebral circuits for response inhibition: V1→daINS→vpIFC/aIFC→BG/M1.

Subject terms: Cognitive control, Neural circuits

Osada et al. used MRI and brain stimulation to outline the macroscopic cerebral circuits for response inhibition: visual cortex→dorsal anterior insula→inferior frontal cortex→basal ganglia/motor cortex, confirming the insula’s critical bridging role.

Introduction

The ability to inhibit a prepotent response, commonly referred to as response inhibition, constitutes a fundamental component of executive control mechanisms essential for adapting to a dynamic environment1. Response inhibition is characterized as the intentional suppression of an ongoing response that is inappropriate in a given context and impedes goal-directed behavior. When confronted with changing environments, individuals with the capacity for response inhibition exhibit behavioral flexibility. The orchestration of the response inhibition process involves intricate interactions in perceptual and control processing2,3. Perceptual processing originates from the sensory cortex, such as the primary visual cortex (V1) and other visual cortical areas (see also4,5 for various sensory modalities other than visual inputs in response inhibition). In contrast, control processing in response inhibition is known to be mediated by the neural circuitry of the prefrontal cortex, basal ganglia (BG), and primary motor cortex (M1)6,7. However, the cerebral pathway through which information travels from the V1 to the prefrontal cortex and subsequently to the BG/M1 remains elusive (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1. Experiment overview.

a The coordination of the response inhibition process involves intricate interactions between perceptual and control processing. Perceptual processing originates in the primary visual cortex (V1), whereas control processing is mediated by the inferior frontal cortex (IFC) of the prefrontal cortex, the basal ganglia, and the primary motor cortex (M1). The cerebral pathway through which information travels from the V1 to the prefrontal cortex and subsequently to the basal ganglia/M1 remains elusive. b Functional and diffusion magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were used to trace the upstream pathway relative to the ventral part of the posterior IFC (vpIFC), bridging the vpIFC and V1 (left). Subsequently, transcranial ultrasound stimulation (TUS) and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) were employed to investigate the behavioral causality of the identified region (right). c Functional and diffusion MRI were employed to track the downstream pathway to the basal ganglia (left). Subsequently, TUS and TMS were used to investigate the behavioral causality of the identified regions and the interaction among them (right). Elements in (b, c) are adapted from refs. 11,30.

Previous studies in neuropsychology, neuroimaging, and noninvasive brain stimulation have demonstrated the central role of the human right inferior frontal cortex (IFC) during response inhibition8–13, as well as the contribution of other areas such as the presupplementary motor area (preSMA) and intraparietal sulcus11,14,15. Specifically, the pars opercularis in the IFC is recognized to play a critical role in control processing of inhibitory control, as evidenced by a correlation between the extent of damage in the pars opercularis and the degree of impairment of response inhibition8. The IFC and the adjacently located anterior insula have also been reported to play perceptual/attentional roles during response inhibition16–18. Conversely, it has been suggested that the IFC is associated with the implementation of inhibitory control while the anterior insula is engaged in detecting behaviorally salient events19. Thus, the cerebrocortical pathway from sensory input in the V1 to the IFC remains controversial.

The IFC is known to interact with the BG to implement response inhibition as outputs6,20,21. In particular, the subthalamic nucleus (STN) is proposed to receive the inhibition-related command from the IFC via a hyperdirect pathway, subsequently relaying this information to the thalamus and M1 through other BG structures22–26. On the other hand, the striatum also contributes to response inhibition through an indirect pathway by the IFC–striatum connection27–30. Consequently, multiple cortical areas are postulated to serve as inputs to the BG, but the overall structure of the cortical output to the BG during response inhibition is unknown.

In the present study, we utilized neuroimaging and interventional brain stimulation to outline macroscopic whole-brain circuits for perceptual and control processing during response inhibition in humans, spanning from the V1 to the BG. Since the ventral part of the posterior IFC (vpIFC)31, a central node in the IFC8,11, lacks a direct structural connection with the V1, it is postulated that a relay point exists between the vpIFC and V1. To this end, we employed functional and diffusion magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to trace the upstream pathway bridging the vpIFC and V1 (Fig. 1b, left). We tracked the downstream pathway to the BG in a similar manner (Fig. 1c, left). Subsequently, we investigated the behavioral causality of the identified regions and the interactions among them by applying transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) targeting cerebrocortical surface regions11,14 and transcranial ultrasound stimulation (TUS) targeting deeper brain structures30,32–39 (Fig. 1b, right and 1c, right).

Results

Brain activation during response inhibition

Subjects performed the stop-signal task requiring the engagement of response inhibition in the MRI scanner to acquire brain activity (Supplementary Fig. 1). Behavioral performance was assessed by the stop-signal reaction time (SSRT), with subjects with shorter SSRTs being considered to be more efficient at response inhibition (see Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2 for the behavioral results). Prominent activation during response inhibition was found in the right hemisphere, including the vpIFC, anterior IFC (aIFC), and anterior insula (the ventral and dorsal parts of the anterior insula [vaINS and daINS, respectively]), which are of special interest in this study (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 1b).

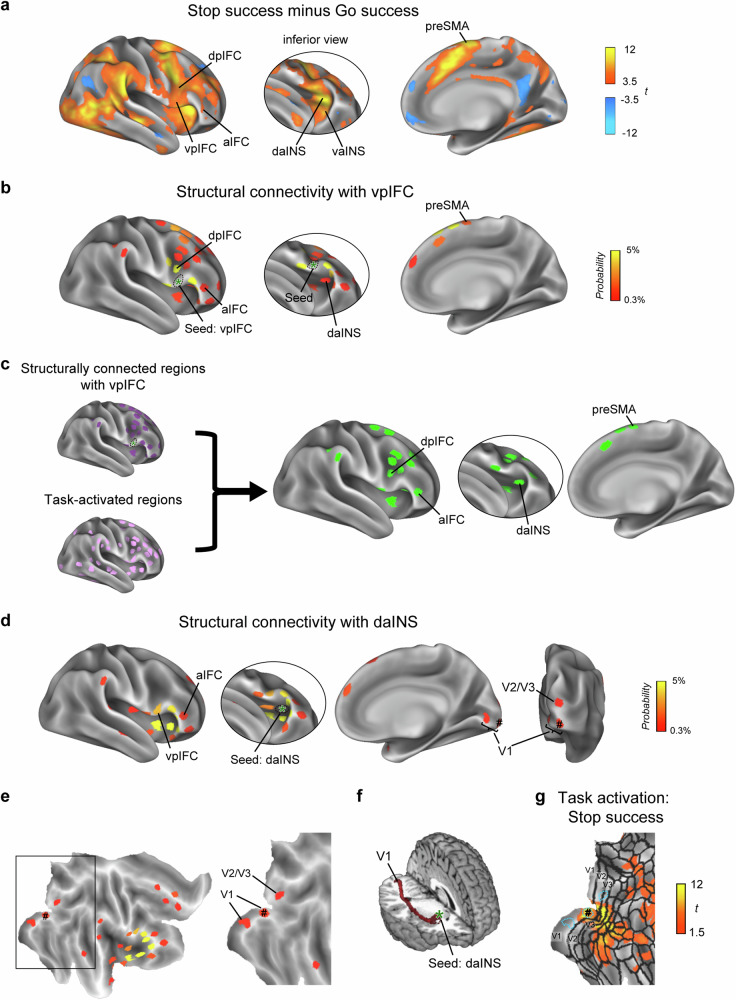

Fig. 2. Brain activity during response inhibition and structural connectivities between the vpIFC and cerebrocortical regions and between the daINS and V1.

a Group-level vertex-wise brain activity during response inhibition (Stop success vs. Go success) on an inflated surface of the right cerebral cortex. The data were calculated from 50 subjects in our experiment. Color scales indicate the t values in the vertices. Left: lateral view, middle: inferior view to show the inside of the lateral sulcus, right: medial view. vpIFC ventral posterior inferior frontal cortex, dpIFC dorsal posterior inferior frontal cortex, aIFC anterior inferior frontal cortex, daINS dorsal anterior insula, vaINS ventral anterior insula, preSMA presupplementary motor area. b The spatial distribution of the regions of interest (ROIs) of the cerebrocortical parcels (i.e., functional areas) for the structural connectivity when the right vpIFC was set as a seed using probabilistic tractography. The data were calculated from 50 subjects in the Human Connectome Project (HCP) database. Color scales indicate the probability of structural connectivity. c The tractography data were underwent thresholding based on the functional MRI task activation data. In total, 19 regions showed both structural connectivity with the vpIFC and task-related activation during response inhibition. d The spatial distribution of the ROIs of the cerebrocortical parcels for the structural connectivity when the right daINS was set as a seed. The data were calculated from 50 subjects in the HCP database. The foveal V1 region is indicated with #. e The distribution of structural connectivity is shown on a flat map of the right cerebral cortex. Left: a flat map of the right hemisphere, right: an enlarged view highlighting the occipital visual cortex. f Tracts connecting the daINS and V1 in the right hemisphere are shown in a 3D view from a representative subject. g Group-level vertex-wise brain activity during the stop-signal task on the flat map (Stop success). Blue dotted lines delineate ROIs of the cerebrocortical parcels for V1 and V2/V3. Black lines delineate the boundaries of the parcellated areas reported in ref. 40.

Structural connectivity from the V1 to the vpIFC

To outline the cortical pathway for response inhibition, we traced the pathways based on the cortical “parcels”, where the cerebral cortex was subdivided into distinct functional units calculated from the resting-state functional connectivity patterns40–42. Specifically, for subsequent analyses, we defined 330 regions of interest centered at 330 cerebrocortical parcels based on ref. 11.

We explored the cerebrocortical regions structurally connected with the vpIFC31, the central node in the stop-signal task (MNI coordinates of the centroid: [52, 14, 8]). Diffusion MRI data from the Human Connectome Project (HCP)40,43 were used for this analysis and the results are presented in Fig. 2b. Importantly, the vpIFC lacked a direct structural connection with the V1. Subsequently, the structural connectivity data were thresholded using the task-related activation data from functional MRI (t > 3.5, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2c). A total of 19 regions, including the aIFC and daINS, showed both structural connectivity with the vpIFC and task-related activation during response inhibition.

We then tested whether the identified 19 regions were structurally connected with the V1. Each of these regions was again seeded in the diffusion MRI analysis. Only the daINS was found to be structurally connected with the foveal region in the V1 (Fig. 2d–f, see Supplementary Fig. 3 for the connectivity patterns of the remaining 18 regions). We confirmed that the foveal V1 region showed activation during Stop success in the stop-signal task (Fig. 2g, see also Supplementary Fig. 4), suggesting that visual input during the task was routed from the foveal V1 region to the daINS. Together with previous literature on perceptual/attentional aspects of response inhibition for the anterior insula18,19, the connectivity analyses suggest the V1–daINS–vpIFC pathway as one of the shortest ones bridging the V1 and vpIFC to be tested in subsequent investigations.

Causal contribution of the daINS to response inhibition

We investigated the essentiality of the identified daINS for response inhibition. As the daINS was located deep in the lateral sulcus, we employed TUS as an interventional brain stimulation method (Fig. 3a). The vaINS was also examined as a control, where task-related activation was observed but no structural connection with the vpIFC was observed (MNI coordinates of the centroids: [34, 24, 12] for the daINS and [30, 26, −2] for the vaINS) (Fig. 2b). In addition, Infomap-based cortical network analysis revealed that the daINS and vpIFC belonged to the cingulo-opercular network, whereas the vaINS belonged to a different network (the fronto-parietal network) (Supplementary Fig. 5). To perturb the target region, a train of pulsed ultrasound was delivered to the target. The stimulation is recognized for its capability to induce sustained suppression of the target region30,33. Performance in the stop-signal task was monitored before and after TUS (pre- and post-TUS, respectively) (Fig. 3b). Estimation of ultrasound intensity based on numerical acoustic simulations confirmed the effective targeting of the daINS and vaINS for each stimulation condition (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Figs. 6a, b).

Fig. 3. TUS effects on the anterior insula during response inhibition.

a The dorsal anterior insula (daINS) was targeted by transcranial ultrasound stimulation (TUS) while the ventral anterior insula (vaINS) was examined as a control. b Experimental procedures. Subjects performed the stop-signal task before and after TUS. Three and five runs were conducted before and after TUS, respectively (pre- and post-TUS). c Simulated intracranial intensity for the daINS and vaINS in horizontal and coronal slices in the normalized MNI space from a representative subject. ls, lateral sulcus. d Time courses of the stop-signal reaction times (SSRTs) before and after TUS (n = 20 subjects). A dashed line indicates baseline SSRTs in pre-TUS. Error bars indicate the standard error of means (SEM) of the subject. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, paired t-test, two-sided. e SSRTs before and after TUS (n = 20 subjects). Gray lines indicate data from each subject. Error bars indicate SEM. The daINS showed the sustained disruption of response inhibition performance after TUS (mean difference in SSRT: 12.1 ms, 95% confidence interval (CI) = [6.6, 17.7], t(19) = 4.5, P = 2.2 × 10−4, paired t-test). The vaINS did not exhibit significant disruption of response inhibition performance (mean difference: 4.7 ms, 95% CI = [−0.3, 9.7], t(19) = 2.0, P = 0.06, paired t-test). The significance level of the daINS overcame the multiple comparisons by Bonferroni correction by 2 fold (number of areas). Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Elements in (b) are adapted from refs. 11,30.

Figure 3d, e shows the behavioral changes after TUS (see also Supplementary Fig. 7 for other behavioral results). The daINS showed the sustained disruption of response inhibition performance after TUS (mean difference in SSRT: 12.1 ms, 95% confidence interval (CI) = [6.6, 17.7], t(19) = 4.5, P = 2.2 × 10−4, paired t-test). In contrast, the vaINS did not exhibit significant disruption of response inhibition performance (mean difference: 4.7 ms, 95% CI = [−0.3, 9.7], t(19) = 2.0, P = 0.06, paired t-test). The significance level of the daINS overcame the multiple comparisons by Bonferroni correction by 2-fold (number of areas). These results suggest that the daINS showed a causal contribution to response inhibition, whereas the vaINS did not.

Two IFC areas as intermediaries between the daINS and basal ganglia

The vpIFC plays an essential role in response inhibition and is postulated to be positioned downstream of the daINS. Given that the vpIFC is known to interact with the STN through a hyperdirect pathway22,44, it is proposed that the vpIFC functions as an intermediary node between the daINS and BG. We next investigated the presence of alternative regions, apart from the vpIFC, that serve as intermediaries between the daINS and BG.

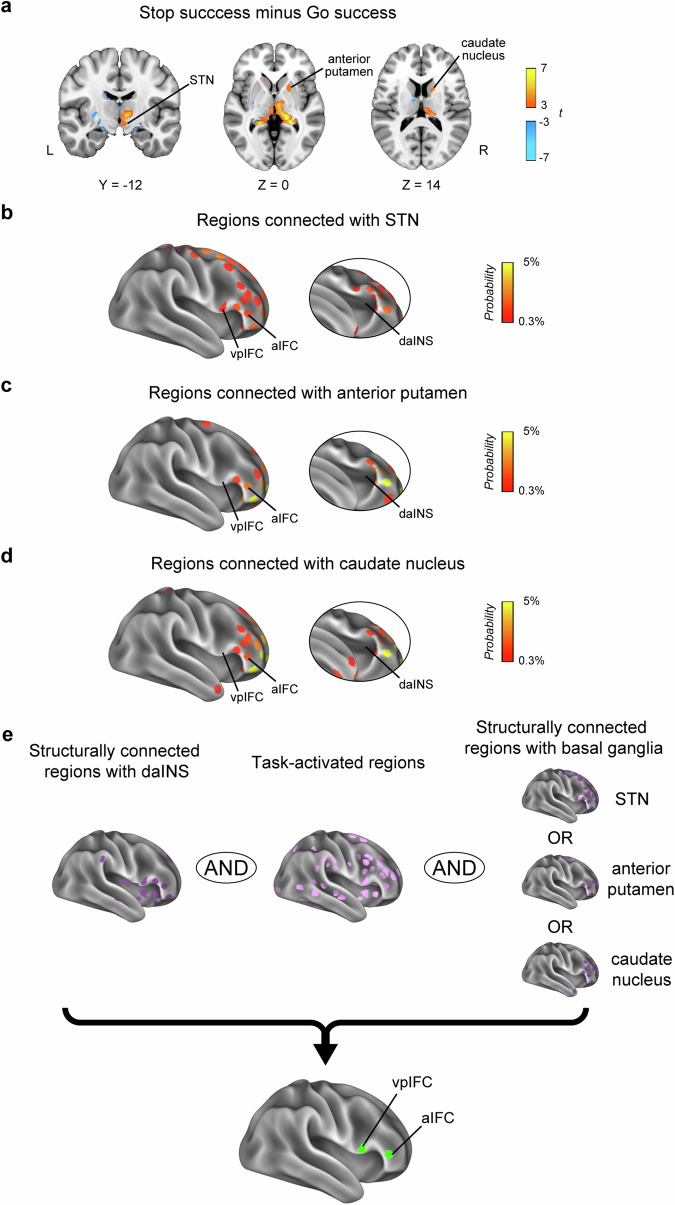

Task-related functional MRI activation in the BG was observed in the STN, the anterior part of the putamen, and the caudate nucleus (Fig. 4a). Using diffusion MRI data, we explored the cerebrocortical regions structurally connected with each of the three identified BG regions (MNI coordinates: [10, −12, −8] for the STN, [20, 6, 0] for the anterior putamen, and [16, 6, 14] for the caudate nucleus) (Fig. 4b–d). We then identified cerebrocortical regions that met the following three criteria (Fig. 4e): (i) structural connectivity with the daINS, (ii) task-related functional MRI activation (t > 3.5, P < 0.001), and (iii) structural connectivity with any of the three BG regions. Along with the expected vpIFC, the aIFC fulfilled these criteria (MNI coordinates of the centroids: [48, 38, 4]), indicating that both the vpIFC and aIFC are downstream areas of the daINS, providing prefrontal output to the BG. It should also be noted that the daINS showed no structural connectivity with any of the BG regions (Supplementary Table 2).

Fig. 4. Brain activity in the basal ganglia and structural connectivity between the basal ganglia and IFC areas.

a Group-level voxel-wise brain activity during response inhibition (Stop success vs. Go success) in the basal ganglia. Only activation with the subcortical regions is shown for display purposes. STN, subthalamic nucleus. The spatial distributions of the ROIs of the cerebrocortical parcels for the structural connectivity when the right STN (b), anterior putamen (c), and caudate nucleus (d) were set as a seed using probabilistic tractography. e Cerebrocortical regions were explored that met the following three criteria: (i) structural connectivity with the daINS, (ii) task-related functional MRI activation, and (iii) structural connectivity with any of the three basal ganglia regions. Two regions were found to meet these criteria: the vpIFC and aIFC.

Essentiality and critical timing for the aIFC in response inhibition

To investigate the temporal dynamics of the aIFC during response inhibition and its association with the vpIFC (Fig. 5a), we employed single-pulse TMS (spTMS) during the stop-signal task, taking advantage of the high temporal resolution of spTMS11,14,45. The target region was stimulated in half of the Go and Stop trials, and the trials with and without stimulation (spStim and no-spStim trials, respectively) were intermixed within runs (Fig. 5b). Critical timing was systematically explored across four 30-ms time windows (−120 to −90 ms; −90 to −60 ms; −60 to −30 ms; and −30 to 0 ms, where the endpoint of the SSRT for no-spStim trials was defined as zero) within each run. SSRT was separately computed for both spStim and no-spStim trials in each run, and the stimulation timing was pseudorandomly updated in each run.

Fig. 5. Effects of single-pulse TMS on the areas in the IFC.

a The anterior IFC (aIFC) and the ventral posterior IFC (vpIFC). b Experimental design. Single-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation (spTMS) was applied to half of the Go and Stop trials. The timing of TMS in spStim trials was derived based on the stop-signal reaction time (SSRT) in no-spStim trials. ΔSSRT: difference in the SSRT between spStim and no-spStim trials. c ΔSSRT across different time windows for spTMS to the aIFC (n = 20 subjects). Error bars indicate SEM. Circles indicate data from each subject. ***P < 0.001, paired t-test, two-sided. Significant ΔSSRT was specifically observed in the time window of −90 to −60 ms (mean: 19.1 ms, 95% CI = [12.9, 25.4], t(19) = 6.4, P = 4.0 × 10−6, paired t-test). The significance level overcame the multiple comparisons by Bonferroni correction by 4-fold (number of time windows). d Reaction times for Go success in spStim and no-spStim trials in each time window (n = 20 subjects). Error bars indicate SEM. Gray lines indicate data from each subject. Note that reaction time for Go success was prolonged in the time window of −90 to −60 ms (mean difference: 12.6 ms, 95% CI = [6.0, 19.2], t(19) = 4.1, P = 6.4 × 10−4, paired t-test). ΔSSRT analyses with reduced time windows of 15 ms for spTMS to the aIFC (e) and to the vpIFC (f). Error bars indicate SEM. Circles indicate data from each subject. *P < 0.05, paired t-test, two-sided. Significant ΔSSRT was were observed in the −90 to −75 ms and −75 to −60 ms time windows for the aIFC (mean: 20.8 ms, 95% CI = [13.8, 27.9], t(11) = 6.5, P = 4.4 × 10−5, paired t-test; mean: 16.6 ms, 95% CI = [2.6, 30.6], t(7) = 2.8, P = 0.03, paired t-test) and the vpIFC (mean: 18.5 ms, 95% CI = [9.2, 27.9], t(8) = 4.6, P = 1.8 × 10−3, paired t-test; mean: 22.2 ms, 95% CI = [7.7, 36.6], t(10) = 3.4, P = 6.6 × 10−3, paired t-test). Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Elements in (b) are adapted from refs. 11,30.

Figure 5c shows the behavioral changes following spTMS to the aIFC across the four time windows. A transient disruption effect, denoted as ΔSSRT (the prolonged SSRT induced by spTMS), was specifically observed in the time window of −90 to −60 ms (mean: 19.1 ms, 95% CI = [12.9, 25.4], t(19) = 6.4, P = 4.0 × 10−6, paired t-test). The significance level overcame the multiple comparisons by Bonferroni correction by 4-fold (number of time windows). Basically, no significant changes were observed in Go reaction time (RT) or in Go and Stop response rates (spStim vs. no-spStim trials) (Fig. 5d, Supplementary Fig. 8), except that Go RT was prolonged in the time window of −90 to −60 ms (mean difference: 12.6 ms, 95% CI = [6.0, 19.2], t(19) = 4.1, P = 6.4 × 10−4, paired t-test).

Importantly, the critical time window of −90 to −60 ms for the aIFC coincided with that previously reported for the vpIFC11. For a more detailed comparison of critical timing, the size of each time window was reduced to 15 ms. Transient disruption effects were observed in the −90 to −75 ms and −75 to −60 ms time windows for the aIFC (mean: 20.8 ms, 95% CI = [13.8, 27.9], t(11) = 6.5, P = 4.4 × 10−5, paired t-test; mean: 16.6 ms, 95% CI = [2.6, 30.6], t(7) = 2.8, P = 0.03, paired t-test) (Fig. 5e) and the vpIFC (mean: 18.5 ms, 95% CI = [9.2, 27.9], t(8) = 4.6, P = 1.8 × 10−3, paired t-test; mean: 22.2 ms, 95% CI = [7.7, 36.6], t(10) = 3.4, P = 6.6 × 10−3, paired t-test) (Fig. 5f). A two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) on ΔSSRT revealed no significant main effect of area (aIFC/vpIFC) or time window (−90 to −75 ms/−75 to −60 ms) (area: F(1, 36) = 0.1, P = 0.75; time window: F(1, 36) = 0.004, P = 0.95), nor a significant interaction effect (F(1, 36) = 0.6, P = 0.44). Taken together, these results indicate that there was no discernible difference in critical timing between the aIFC and vpIFC.

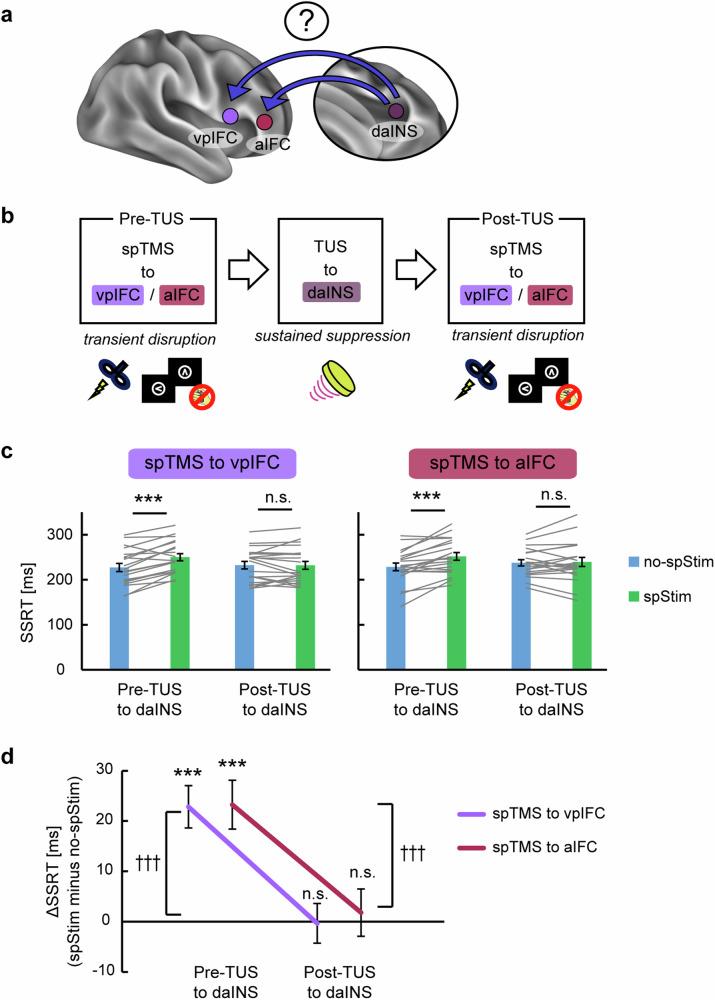

Insular-prefrontal interactions revealed by combined spTMS and TUS

We investigated the hierarchical positioning of the daINS relative to the vpIFC and aIFC during response inhibition (Fig. 6a). To this end, we applied TUS to the daINS, inducing sustained suppression, and compared the transient disruption effects by spTMS to the vpIFC and aIFC before and after TUS (Fig. 6b). If the daINS is at an upstream position, then suppression of the daINS should negatively affect the vpIFC and aIFC, thereby reducing the transient disruption effects. Figure 6c shows the transient disruption effects when spTMS was targeted to the vpIFC (Fig. 6c, left) or the aIFC (Fig. 6c, right) before or after TUS (see also Supplementary Fig. 9 for other behavioral results). Before TUS to the daINS, a significant SSRT prolongation was observed for spTMS to the vpIFC (mean: 22.8 ms, 95% CI = [14.1, 31.6], t(19) = 5.5, P = 2.9 × 10−5, paired t-test) and to the aIFC (mean: 23.3 ms, 95% CI = [13.1, 33.4], t(19) = 4.8, P = 1.3 × 10−4, paired t-test). However, after TUS to the daINS, spTMS to the vpIFC did not elicit a significant prolongation of SSRT (mean: −0.3 ms, 95% CI = [−8.6, 7.9], t(19) = −0.1, P = 0.93, paired t-test), and the same was observed for the aIFC (mean: 1.8 ms, 95% CI = [−8.0, 11.6], t(19) = 0.4, P = 0.70, paired t-test). Both spTMS to the vpIFC and aIFC resulted in a significant decrease in ΔSSRT after TUS application (mean difference: −23.2 ms, 95% CI = [−33.7, −12.7], t(19) = −4.6, P = 1.8 × 10−4, paired t-test; mean difference: −21.5 ms, 95% CI = [−36.0, −6.9], t(19) = −3.1, P = 6.0 × 10−3, paired t-test) (Fig. 6d). Task-related connectivity analyses in functional MRI using generalized psychophysiological interaction (gPPI)46 also confirmed significant connectivity in the vpIFC and aIFC when the seed was set to the daINS (Supplementary Fig. 10a). These results collectively affirm the causal influence of the daINS on both the vpIFC and aIFC.

Fig. 6. Combined single-pulse and TUS for the hierarchical structure of daINS–vpIFC and daINS–aIFC.

a The hierarchical positioning of the daINS relative to the vpIFC and aIFC during response inhibition was investigated. Specifically, the causal influence of the daINS to the vpIFC and aIFC was examined. b Experimental design. Transcranial ultrasound stimulation (TUS) was applied to the daINS, and changes in the transient disruption effects in the vpIFC or aIFC were examined by comparing the effects before and after TUS (pre- and post-TUS, respectively). spTMS, single-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation. c The stop-signal reaction time (SSRT) in spStim and no-spStim trials when spTMS was applied to the vpIFC or aIFC in pre- or post-TUS (n = 20 subjects). Error bars indicate SEM. Gray lines indicate data from each subject. ***P < 0.001, paired t-test, two-sided. In pre-TUS, SSRT was prolonged significantly for spTMS to the vpIFC (mean: 22.8 ms, 95% CI = [14.1, 31.6], t(19) = 5.5, P = 2.9 × 10−5, paired t-test) and to the aIFC (mean: 23.3 ms, 95% CI = [13.1, 33.4], t(19) = 4.8, P = 1.3 × 10−4, paired t-test). However, in post-TUS, a significant difference in SSRT was not observed (for the vpIFC, mean: −0.3 ms, 95% CI = [−8.6, 7.9], t(19) = −0.1, P = 0.93, paired t-test; for the aIFC, mean: 1.8 ms, 95% CI = [−8.0, 11.6], t(19) = 0.4, P = 0.70, paired t-test). d Differences in the SSRT between spStim and no-spStim trials (ΔSSRT) in pre- and post-TUS (n = 20 subjects). Error bars indicate SEM. †††P < 0.001, paired t-test for ΔSSRT (pre- vs. post-TUS), two-sided. Significant differences were observed both in the vpIFC and aIFC (for the vpIFC, mean difference: −23.2 ms, 95% CI = [−33.7, −12.7], t(19) = −4.6, P = 1.8 × 10−4, paired t-test; for the aIFC, mean difference: −21.5 ms, 95% CI = [−36.0, −6.9], t(19) = −3.1, P = 6.0 × 10−3, paired t-test). Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Elements in (b) are adapted from refs. 11,30.

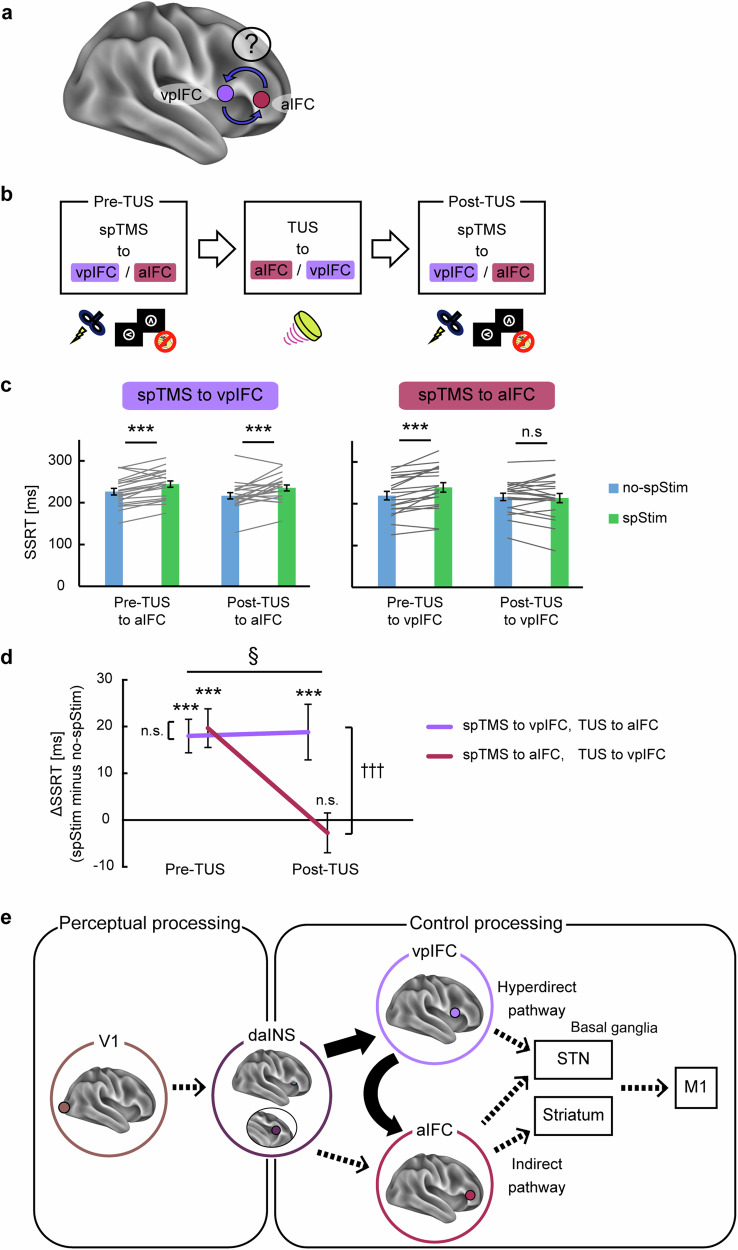

Asymmetric structure within the IFC for response inhibition

We next examined the relationship between the downstream areas in relation to the daINS: the vpIFC and aIFC (Fig. 7a). The results of the spTMS experiments indicated that both areas share the same critical timing (Fig. 5e, f). Several potential scenarios are postulated: (i) mutual dependence with bidirectional influence (from the vpIFC to the aIFC and vice versa), (ii) unidirectional dependence (either from the vpIFC to the aIFC or from the aIFC to the vpIFC), and (iii) no dependence. To address these possibilities, TUS was applied to the vpIFC for sustained suppression and the transient disruption effects by spTMS to the aIFC were compared before and after TUS. The configuration of the target areas was also reversed (Fig. 7b).

Fig. 7. Combined single-pulse and TUS for the relationship between the vpIFC and aIFC.

a The relationship between the vpIFC and aIFC, downstream areas of the daINS, was investigated. b Experimental design. Transcranial ultrasound stimulation (TUS) was applied to either the aIFC or vpIFC, and changes in the transient disruption effects in the vpIFC or aIFC, respectively, were investigated by comparing the effects in pre- and post-TUS. spTMS, single-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation. c The stop-signal reaction time (SSRT) in spStim and no-spStim trials when spTMS was applied to the vpIFC or aIFC in pre- or post-TUS (n = 20 subjects). Error bars indicate SEM. Gray lines indicate data from each subject. ***P < 0.001, paired t-test, two-sided. In pre-TUS, a significant increase in SSRT was observed for spTMS to the vpIFC (mean: 18.0 ms, 95% CI = [10.5, 25.5], t(19) = 5.0, P = 7.8 × 10−5, paired t-test) and to the aIFC (mean: 19.7 ms, t(19) = 4.7, 95% CI = [11.0, 28.3], P = 1.4 × 10−4, paired t-test). After TUS to the aIFC, the SSRT was still prolonged by spTMS to the vpIFC (mean: 18.8 ms, 95% CI = [6.4, 31.3], t(19) = 3.2, P = 5.1 × 10−3, paired t-test). In contrast, after TUS to the vpIFC, the SSRT was not prolonged by spTMS to the aIFC (mean: −2.7 ms, 95% CI = [−11.6, 6.1], t(19) = −0.6, P = 0.53, paired t-test). d Differences in the SSRT between spStim and no-spStim trials (ΔSSRT) in pre- and post-TUS (n = 20 subjects). Error bars indicate SEM. †††P < 0.001, paired t-test for ΔSSRT (pre- vs. post-TUS), two-sided; §P < 0.05, an interaction effect in a two-way ANOVA. A significant interaction effect was observed between the area (spTMS to vpIFC/aIFC) and the pre/post-TUS condition in a two-way ANOVA(F(1,19) = 10.0, P = 0.01). spTMS to the aIFC resulted in a significant decrease in ΔSSRT (mean difference: −22.2 ms, 95% CI = [−32.3, −12.2], t(19) = −4.6, P = 1.8 × 10−4, paired t-test), while spTMS to the vpIFC did not (mean difference: 0.8 ms, 95% CI = [−12.5, 14.1], t(19) = 0.1, P = 0.90, paired t-test). e Information processing during response inhibition. Perceptual information undergoes initial processing in the V1 before being subsequently relayed to the daINS. From the daINS, information is directed to either the vpIFC or aIFC and subsequently to the basal ganglia/M1. There exists a unidirectional dependence of the aIFC on the vpIFC. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Elements in (b) are adapted from refs. 11,30.

Figure 7c shows the transient disruption effects when spTMS was targeted to the vpIFC (Fig. 7c, left) or the aIFC (Fig. 7c, right) before or after TUS (see also Supplementary Fig. 6c–g for simulations of stimulations and Supplementary Fig. 11 for other behavioral results). Before TUS, a significant increase in SSRT was observed for spTMS to the vpIFC (mean: 18.0 ms, 95% CI = [10.5, 25.5], t(19) = 5.0, P = 7.8 × 10−5, paired t-test) and to the aIFC (mean: 19.7 ms, t(19) = 4.7, 95% CI = [11.0, 28.3], P = 1.4 × 10−4, paired t-test). After TUS to the aIFC, the SSRT was still prolonged by spTMS to the vpIFC (mean: 18.8 ms, 95% CI = [6.4, 31.3], t(19) = 3.2, P = 5.1 × 10−3, paired t-test), suggesting no causal influence from the aIFC to the vpIFC. In contrast, after TUS to the vpIFC, the SSRT was not prolonged by spTMS to the aIFC (mean: −2.7 ms, 95% CI = [−11.6, 6.1], t(19) = −0.6, P = 0.53, paired t-test), indicating the causal influence from the vpIFC to the aIFC. A two-way ANOVA on ΔSSRT revealed a significant interaction effect between the area (spTMS to vpIFC/aIFC) and the pre/post-TUS condition (F(1,19) = 10.0, P = 0.01) (Fig. 7d). spTMS to the aIFC resulted in a significant decrease in ΔSSRT after TUS application (mean difference: −22.2 ms, 95% CI = [−32.3, −12.2], t(19) = −4.6, P = 1.8 × 10−4, paired t-test), while spTMS to the vpIFC did not (mean difference: 0.8 ms, 95% CI = [−12.5, 14.1], t(19) = 0.1, P = 0.90, paired t-test). Task-related connectivity analyses in functional MRI also confirmed significant connectivity in the aIFC when the seed was set to the vpIFC (Supplementary Fig. 10b). These results suggest that, although both the vpIFC and the aIFC are downstream of the daINS, there exists a unidirectional dependence with one-way causal influence from the vpIFC to the aIFC (Fig. 7e).

Discussion

The present study used neuroimaging to outline the cerebral pathway underlying response inhibition at the whole-brain level, originating from the V1, progressing through the daINS, subsequently involving the two essential IFC regions, namely the vpIFC and aIFC, and ultimately extending to the BG/M1. The pathway was subsequently tested for causality through noninvasive brain stimulation. The daINS was revealed to causally contribute to response inhibition and also to exert a causal influence on both the vpIFC and aIFC. Furthermore, a unidirectional dependence of the aIFC on the vpIFC was demonstrated. Collectively, these results suggest that the daINS plays a pivotal role in bridging perceptual processing and control processing and that response inhibition is achieved through interactions within the asymmetric pathways in the insula–IFC (Fig. 7e).

Diffusion MRI was utilized in this study to outline the cerebral pathway involved in response inhibition that can be used for subsequent causal testing through noninvasive brain stimulation. The delineation relied on robust structural connectivity, with the threshold set at 0.3% in the present dataset, where the established connectivity between the vpIFC and STN22,24,25,44 was confirmed. The delineation does not exclude the potential involvement of connectivity below the threshold. It should also be noted that this study demarcated the shortest tracts to outline the whole-brain pathway: the upstream pathway was identified as the shortest tracts bridging the V1 and vpIFC, while the downstream pathway was identified as the shortest tracts bridging the daINS and BG. Therefore, a well-known pathway connecting the vpIFC and STN via the preSMA22,24,25,27,47 was not included for analysis in this study. While acknowledging other possibilities, the finding that the delineated pathway was centered around the IFC/insula was corroborated by the previous report indicating that the extent of damage around the IFC correlated with the degree of impairment in response inhibition8. Consistent with anatomical literature on macaque monkeys48 and diffusion MRI research in humans47 reporting weaker anatomical connectivity between the IFC and STN, the vpIFC is suggested to be involved in response inhibition by modulating the main pathway from the preSMA to the STN25. A previous electrophysiological study in rodents49 demonstrated that the STN operates during both stop success and error, which is consistent with the horse race theory in that the STN activity may code stop processes that compete with go processes.

Widespread activation during response inhibition was observed in the anterior insula. However, this area exhibited heterogeneity based on the following aspects. First, prior studies implicated the anterior insula in various processing, including attentional, arousal, affective, and interoceptive functions18,50–52. Second, the network analyses in the present study unveiled distinct characteristics, with the daINS associated with the cingulo-opercular network and the vaINS associated with the fronto-parietal network (Supplementary Fig. 5). Third, TUS applied to the two distinct regions in the anterior insula revealed a dissociation in causal behavioral effects: TUS targeting the daINS induced behavioral impairment, while TUS targeting the vaINS did not (Fig. 3). Within this functional heterogeneity, the daINS was found to have direct connections with both the vpIFC and V1, while lacking a connection with the BG (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 2). The anterior insula is known to be involved in the integration of multiple modalities of sensory information including visual, auditory, and tactile inputs53–60. It has also been demonstrated that the right anterior insula, predominantly corresponding to the daINS, is engaged in detecting behaviorally salient events, whereas the right IFC, the main part of which corresponds to the vpIFC, is associated with the implementation of inhibitory control19. Collectively, the daINS is suggested to be involved in processing prior to the act of stopping and receives converging inputs of multimodal sensory signals before executive control is implemented via the IFC.

The aIFC, along with the vpIFC, was positioned downstream relative to the daINS (Fig. 6) and served as inputs to the BG (Fig. 4), suggesting that the aIFC functions as another central node within the IFC. Transient intervention via spTMS revealed a critical time window of −90 to −60 ms prior to stopping, which coincided with that observed for the vpIFC11. The congruence in these critical timings implies an online interactive control processing executed by both the vpIFC and aIFC. On the other hand, an asymmetric dependence structure supports hierarchical functional roles of the vpIFC and aIFC. More specifically, when the vpIFC was sustainedly suppressed by TUS, without sustained suppression to the daINS or aIFC, spTMS to the aIFC no longer deteriorated behavioral performance (Fig. 7d). The results raise the possibility that the influence of the daINS on the aIFC (Fig. 6d) was induced by polysynaptic tracts via the vpIFC rather than the direct tract from the daINS to the aIFC (Fig. 7e). It is to be noted, however, that the effectiveness of the direct tract from the daINS to the aIFC cannot be precluded since suppression of the vpIFC might induce a ceiling effect in behavioral changes.

During response inhibition, both reactive and proactive inhibitory controls are involved. In the former case, subjects rapidly stop a movement based on the presentation of an external signal, while in the latter case, subjects adjust responses to an upcoming event by preventing or slowing their actions. Specifically, although reactive inhibitory control is generally considered the main component, the stop-signal task also involves proactive mechanism, especially after stop error trials61. In the cerebral cortex, van Belle et al.62 showed that the aIFC is more suited toward proactive response inhibition than the vpIFC. The aIFC and vpIFC exhibit distinctive connectivity patterns with the BG. Specifically, the vpIFC exhibited a connection with the STN through a hyperdirect pathway, while the striatum, particularly the anterior putamen and caudate nucleus, was strongly connected with the aIFC via an indirect pathway22,24,25,30 (Figs. 4 and 7, Supplementary Table 2). Based on the proposed roles of the BG in response inhibition3,21, the STN and striatum are postulated to be involved in reactive and proactive response inhibition, respectively. These literatures collectively postulate that the neural circuitry of the vpIFC and STN participates more dominantly in reactive inhibitory control, whereas that of the aIFC and striatum participates more dominantly in proactive inhibitory control. The results of combined spTMS and TUS for the vpIFC and aIFC (Fig. 7) also suggest a hierarchical relationship between the vpIFC and aIFC, rather than simply a unidirectional dependence, with the vpIFC situated in a higher position. The implication of asymmetric insular-IFC pathways suggests the orchestration of fast and slow processes implemented by the prefrontal-BG interactions to achieve response inhibition.

Methods

Subjects

Fifty healthy right-handed subjects (23 men and 27 women, age: 23.4 ± 6.6 years [mean ± SD]) participated in the functional MRI (fMRI) experiment. Twenty healthy right-handed subjects (8 men and 12 women, age: 22.0 ± 3.5 years) participated in the TUS experiments to the daINS/vaINS. Twenty healthy right-handed subjects (7 men and 13 women, age: 21.5 ± 1.2 years) participated in the spTMS experiments to the aIFC. Twenty healthy right-handed subjects (11 men and 9 women, age: 22.6 ± 4.4 years) participated in experiments of TUS to the daINS and spTMS to the vpIFC/aIFC. Twenty healthy right-handed subjects (11 men and 9 women, age: 21.4 ± 0.7 years) participated in experiments of TUS to the vpIFC/aIFC and spTMS to the aIFC/vpIFC. Four other subjects failed to complete the TMS experiments due to stimulation discomfort63 and were not included in the analysis. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects according to the Declaration of Helsinki. The experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Juntendo University School of Medicine.

Behavioral procedures

In the fMRI experiment, the subjects performed a stop-signal task11,14,30,31,64–66 (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Task procedures followed the guidelines described in ref. 67. Online behavioral control was implemented in the Presentation software (Neurobehavioral Systems, Berkeley, CA, USA). The stop-signal task consisted of Go and Stop trials. Each trial began with the presentation of a warning circle at the center of the screen for 500 ms. In Go trials, a left- or right-pointing arrow (Go signal) was presented within the circle, and the subjects were instructed to press a button with their right thumb to indicate the direction of the arrow. In Stop trials, the Go signal was initially presented within the circle. After a stop-signal delay (SSD), the arrow was changed to an upward-pointing arrow, and the subjects were required to withhold their manual response. The SSD was dynamically adjusted using four staircases, with each Stop trial subject to a 50 ms increment/decrement tracking procedure. This procedure was designed to maintain ~50% accuracy on Stop trials. The intertrial interval ranged from 0.5 to 4 s (mean, 1 s). To assess response inhibition efficiency, the SSRT was estimated for each subject using an integration method68,69. Subjects with shorter SSRTs were considered to be more efficient at response inhibition. Two practice runs were performed prior to the test runs. Each fMRI run consisted of 96 Go trials and 32 Stop trials. All experiments analyzed in this study confirmed the presence of the following three assumptions67 to validate the independent race model in the stop-signal task: (i) RT in Stop failure trials is shorter than that in Go success trials; (ii) RT in Stop failure trials increases as a function of SSD; and (iii) the probability of Stop failure trials increases as a function of SSD.

In the TUS experiments targeting the daINS/vaINS, the stop-signal task was also used. The task procedures were the same as those in the fMRI experiments. One practice run was administered before the test runs. Three runs were administered before the TUS (pre-TUS) and five runs were administered after the TUS (post-TUS). In the TMS experiments (both spTMS-only and combined TUS and spTMS paradigms), the stop-signal task was used in a similar manner. The task procedures were basically the same as those in the fMRI experiment, except that the SSD was adjusted in 25 ms increments or decrements, the intertrial interval ranged from 1.5 to 4 s (mean, 2 s), and each TMS run consisted of 80 Go trials and 40 Stop trials. Four separate staircases were implemented for the SSDs to track the subjects’ performance in the trials with and without spTMS, with two staircases used for stimulation trials and two for no-stimulation trials.

MRI procedures

Image data were acquired using a 3-T MRI scanner and a 64-channel radiofrequency head coil (Siemens Prisma, Erlangen, Germany). T1- and T2-weighted structural images were acquired (resolution = 0.8 × 0.8 × 0.8 mm3). Functional images were then acquired using multi-band gradient-echo echo-planar sequences (TR = 1.0 s, TE = 30 ms, flip angle = 62 deg, FOV = 192 × 192 mm2, matrix size = 96 × 96, 78 contiguous slices, voxel size = 2.0 × 2.0 × 2.0 mm3, multi-band factor = 6, phase-encoding direction = posterior to anterior). For the resting-state scan, subjects were asked to fixate on a cross displayed on a screen70–76. One run consisted of 360 volumes, and 10 runs were administered. In the task scan, subjects performed the stop-signal task (see Behavioral procedures). One run consisted of 330 volumes, and 10 runs were administered. Before each run, a functional image was acquired with the opposite phase-encoding direction for subsequent topup distortion correction in image preprocessing.

Image analysis of functional MRI

Image preprocessing for the resting-state dataset was performed mainly following the HCP pipelines40,43 using the tools in FSL and Connectome Workbench (https://www.humanconnectome.org/software/connectome-workbench). Functional images were realigned, topup distortion corrected77, and spatially normalized to the MNI template. Time-series data were cleaned using the independent component analysis-based X-noiseifier (ICA-FIX) method78. Following volumetric preprocessing, image data were projected onto the 32k fs_LR surface space using the full version of the multimodal surface matching method (MSMAll)46,79.

Following the preprocessing of resting-state data, each vertex on the cortical surface of each subject was used as a seed for calculating its temporal correlation with all other vertices, after regressing out the mean cortical grayordinate signal and spatial smoothing with a 6 mm full-width-at-half maximum. Subsequently, after averaging vertex-wise functional connectivity patterns across subjects, the vertex-wise network organization was determined using the graph-theory-based Infomap algorithm for community detection, resulting in the assignment of the 17 cortical networks80–82.

For the task dataset, image preprocessing was similar to the resting-state dataset, except for the absence of ICA-FIX denoising. Data projection onto the 32k fs_LR surface space using MSMAll, which was defined with the resting-state data, was also performed. Task activation analysis was performed at each vertex and subcortical voxel, followed by spatial smoothing with a 6-mm kernel. A general linear model was applied to each vertex and subcortical voxel using SPM8 (https://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/). Two events of interest (Go success and Stop success) and two nuisance events (Go failure and Stop failure) were coded at the onset of the Go signal in each trial and modeled as transient events convolved with a canonical hemodynamic response function and its temporal derivative. The model incorporated six head motion parameters derived from realignment as covariates of no interest. The time-series data were high-pass filtered (cutoff: 64 s). Magnitude images for individual subjects were contrasted between Stop success and Go success trials. For a group analysis, the contrast images were entered into a one-sample t-test using a random effect model. Task-related connectivity analyses83–85 were also conducted using gPPI46.

Delineating distinct cortical areas solely from task-related activation peaks in functional MRI is difficult because activation patterns for response inhibition tend to be widespread, particularly within the IFC. Thus, we evaluated task-related activation based on the cortical parcels (i.e., functional units), where the cerebral cortex was subdivided into distinct units11,14,41,42,46. We utilized 330 cortical parcels based on ref. 11, where small parcels were removed from the original 360 parcels. This cortical parcellation relied on resting-state functional connectivity patterns71,86–94. The size of the parcel ranged from 35 to 960 (123.6 ± 106.3 vertices [mean ± SD]). For each parcel, a region of interest (ROI) was defined to mitigate nonuniform signal-to-noise ratios resulting from variations in vertex counts across parcels. The ROI consisted of the 40 vertices closest to the centroid of each parcel. If the parcel contained fewer vertices, all vertices were included in the ROI.

Image analysis of diffusion MRI

Diffusion MRI data were obtained from the HCP database (HCP WU-Minn 1200 data). Data were acquired with a multi-shell protocol (multi-band spin-echo echo-planar sequences, voxel size = 1.25 × 1.25 × 1.25 mm3, direction = 95/96/97, multi-shells of b-values = 1000, 2000, 3000 s/mm2, multi-band factor = 3). Data from 50 randomly selected subjects underwent comprehensive analysis. Preprocessing was performed based on the HCP pipelines43, including topup distortion correction, eddy current and motion correction, and probabilistic fiber tractography estimation with bedpostX.

For tracking the upstream pathway bridging the vpIFC and V1, tracts were first estimated from the vpIFC ROI (MNI coordinates of the centroid: [52, 14, 8]) to the ROIs in the 330 cerebrocortical parcels using probabilistic tractography. To quantify connectivity strength, streamline counts to the ROIs in the cerebrocortical parcels were normalized for each subject and subsequently averaged across subjects. The tractography data were then thresholded using the fMRI activation data. Cortical regions in the right hemisphere that showed both structural connectivity with the vpIFC (> 0.3%) and task activation (t > 3.5, P < 0.001) were identified. Since the cerebral pathways are generated for later causal testing via brain stimulation, the threshold for the structural connectivity (0.3 %) was set based on the established connectivity between the vpIFC and STN22,24,25,44. Each of the identified regions was then used as a seed for subsequent tracts and examined for structural connectivity with the V1. Since the V1 is known to be heavily connected with numerous neighboring extrastriate cortical regions, the tracts from the vpIFC to the V1 should be more sensitively traced than the tracts from the V1 to the vpIFC.

For tracking the downstream pathway to the BG, tracts were first estimated from the daINS ROI (MNI coordinates of the centroid: [34, 24, 12]) to the ROIs in the 330 cerebrocortical parcels. Conversely, tracts were also estimated from the BG regions (STN, anterior putamen, and caudate nucleus; MNI coordinates, [10, −12, −8] for the STN, [20, 6, 0] for the anterior putamen, and [16, 6, 14] for the caudate nucleus) to the ROIs in the 330 cerebrocortical parcels. The cerebrocortical regions in the right hemisphere meeting the following three criteria were identified: (i) structural connectivity with the daINS (> 0.3%), (ii) task-related activation (t > 3.5), and (iii) structural connectivity with any of the three BG regions (> 0.3%).

The size of the ROI (40 vertices) was close to the lower limit of the parcel size range (35–960 vertices). Consistently, no significant correlation was found between the strength of structural connectivity and the size of the ROIs for the seed of the vpIFC (r = 0.05, P = 0.40), indicating that the results of structural connectivity were not affected by the size of the ROI of the parcel.

TUS procedures

A four-element annular array TUS transducer (NeuroFUS CTX-500, Brainbox Ltd, Cardiff, UK), coupled with a programmable radiofrequency amplifier (Transducer Power Output System, TPO-203, Brainbox Ltd, Cardiff, UK), was used with a fundamental frequency of 500 kHz and diameter of 60 mm. The amplifier controlled the phasing of the four elements to adjust sonication depth. Aqueous gel pads (Echo Gel Pad, Yasojima, Kobe, Japan) were placed between the surface of the transducer and the subject’s scalp, and ultrasound gel (Aquasonic 100, Parker Laboratories, NJ, USA) was applied at the scalp-pad interface. An online navigator ensured that stimulation was targeted to planned regions. T1-weighted images were registered to the subjects’ heads in space using a tracking device and navigator software (TMS Navigator-SW, Localite, Sankt Augustin, Germany). The position and orientation of the transducer were also registered to the subjects’ heads in space, and were monitored and recorded in real time. The deviation of the TUS transducer position was 0.53 ± 0.26 mm (mean ± SD).

The ultrasound stimulation consisted of 30 ms pulse repeated every 100 ms, and the total sonication lasted for 40 s, which is known to induce sustained suppression of the target region30,33,95,96. The spatial-peak pulse-average intensity in water (free field) was ISPPA = 30.0 W/cm2 (for spatial-peak temporal-average intensity, ISPTA = 10.0 W/cm2). The attenuation by the skull lowers these values. k-Wave97 (http://www.k-wave.org/), an acoustic simulation toolbox, was used to calculate simulations of the acoustic focus for each subject based on transducer positions. 3D maps of the skin, scalp, skull, and brain tissues were estimated based on structural MRI of each subject and were used in the simulations. Intensity fields and temperature increase after sonication were mapped for each sonication condition (estimated intracranial intensities: ISPPA = 15.2 ± 1.7 W/cm2 [mean ± SD] and ISPTA = 4.5 ± 0.5 W/cm2 for TUS to the daINS, and ISPPA = 14.3 ± 3.9 W/cm2 and ISPTA = 4.3 ± 1.2 W/cm2 for TUS to the vaINS; estimated temperature increase: 0.2 ± 0.1 °C [brain] and 0.4 ± 0.2 °C [skull] for TUS to the daINS, and 0.2 ± 0.1 °C [brain] and 0.4 ± 0.2 °C [skull] for TUS to the vaINS). The subjects in this study reported no adverse effects after the TUS experiments. The stimulated regions (the daINS and vaINS) were pseudorandomly counterbalanced across subjects.

TMS procedures

TMS was administered to examine the effective timing of brain stimulation to the aIFC. Using a hand-held figure-of-eight coil (7-cm diameter; Magstim, Whitland, Dyfed, UK) and a monophasic stimulator (Magstim 2002, Magstim), monophasic spTMS was conducted to determine the resting motor threshold (RMT) for the right first dorsal interosseous (FDI) muscle by targeting the fMRI-based predetermined M1 spot30,98,99. The online navigator was used to stimulate the identified target region. Motor evoked potentials (MEP) were recorded from the right FDI muscle using Ag/AgCl sheet electrodes placed over the muscle belly (active) and metacarpophalangeal joint of the index finger (reference). The signals were sent to an amplifier through filters set at 5 Hz to 3 kHz. The RMT was defined as the lowest intensity that evoked a small response (>50 µV) in more than 5 of 10 consecutive trials when the subjects relaxed14. The stimulation intensity was set at 120% of the RMT. For three out of 20 subjects, the stimulation intensity was further adjusted to accommodate comfort63. The mean (±SD) stimulation intensity was 46.7 (±4.0) % of the maximum stimulator output (range: 39–50%), which corresponds to 117.3 (±4.2) % of the RMT (range: 106–120% of the RMT).

Monophasic spTMS was delivered to the target aIFC (MNI coordinates of the centroid: [48, 38, 4]). The stimulation target was determined based on the fMRI results of group data, and the coordinates from the group data were converted to each subject’s space. While stimulating the individual peak of fMRI will improve the effectiveness of simulation100, 101), it is virtually unfeasible to determine individual peaks in the association areas, unlike the M1, since there were several individuals who did not show clear activation peaks. To enhance the spatial specificity of the excitation effects, we employed optimal directions of the TMS coil when targeting the aIFC. The TMS coil was placed such that the short axis of the coil was parallel to the lateral sulcus to induce electric current along the posterior to anterior direction, unlike the case of the vpIFC where the TMS coil was placed such that the short axis of the coil was perpendicular to the lateral sulcus. Electric field elicited by spTMS was simulated by SimNIBS102.

spTMS was delivered in half of the Go and Stop trials (spStim Go and Stop trials), with no-spStim Go and Stop trials intermixed within a run. One run contained 80 Go (40 spStim Go and 40 no-spStim Go) trials and 40 Stop (20 spStim Stop and 20 no-spStim Stop) trials. The order of spStim and no-spStim trials was counterbalanced within runs such that spStim/no-spStim trials were followed by spStim and no-spStim trials with almost equal probability. The SSRT was calculated at every run for both spStim and no-spStim trials. To explore the critical timing of stimulation within the SSRT, each of four time windows of 30 ms (−120 to −90 ms; −90 to −60 ms; −60 to −30 ms; and −30 to 0 ms, where the endpoint of the SSRT for no-spStim trials was defined as zero) was investigated in each run. Since the SSRT in each run could only be determined after the run was completed, the SSRT in no-spStim trials of the last run was used to determine stimulation timing (for the first test run, the SSRT in the last practice run was referred).

To collect behavioral data for each time window in each subject, one run with stimulation delivered at the designated time window was required, and the sessions continued until data for all four time windows were collected. TMS sessions were administered typically for five runs per day. The planned order of time windows was counterbalanced across subjects. Since the SSRT was determined only after the run was completed, the time window for stimulation was also determined only after the run was completed. When stimulation was delivered outside the four time windows, the runs were discarded (13.0 ± 12.4% [mean ± SD]). In addition, when stimulation was delivered multiple times within the same time window, the second and later runs were discarded (12.9 ± 14.9%), and only the first run was kept for analyses (74.1 ± 15.8%).

For three out of 20 subjects, the stimulation intensity in spTMS to the aIFC was reduced from 120% of the RMT to mitigate discomfort63. No significant correlation was found between ΔSSRT in spTMS to the aIFC and the relative intensity to the RMT (r = −0.03, p = 0.89 for the time window of −120 to −90 ms; r = 0.19, P = 0.42 for the time window of −90 to −60 ms; r = −0.09, P = 0.72 for the time window of −60 to −30 ms; r = 0.13, P = 0.60 for the time window of −30 to 0 ms). These indicated that the result of spTMS was not affected by the variations in stimulation intensity.

Procedures of combined TMS and TUS

In the combined experiments of TUS to the daINS and spTMS to the vpIFC/aIFC, TUS was applied to the daINS for sustained suppression and spTMS was delivered to the vpIFC or aIFC for transient disruption before and after the TUS to the daINS (pre- vs. post-TUS). The experimental procedures for spTMS were the same as those in spTMS-only experiments. The time window of −100 to −50 ms was targeted for stimulation based on the previous results (−90 to −60 ms) but was slightly enlarged to ensure more efficient data collection. Approximately 5-min interval was maintained between the TUS and post-TUS sessions. In the combined experiments of TUS to the vpIFC/aIFC and spTMS to the aIFC/vpIFC, the procedures were similar to those described above. TUS was applied to the vpIFC or aIFC for sustained suppression and spTMS was delivered to the aIFC or vpIFC for transient disruption, respectively, before and after the TUS. The stimulated regions were pseudorandomly counterbalanced across subjects. Based on our previous study11, we postulated that when an upstream area is sustainedly suppressed, interventional effects to a downstream area should be ineffective. It is also to be noted that the ineffective behavioral effect might be due to rapid short-term reorganization of the large-scale network after stimulation through compensatory mechanisms103,104. The mean (±SD) stimulation intensity was: 44.9 ± 4.6 % for spTMS to the vpIFC (TUS to the daINS), 44.2 ± 4.5 % for spTMS to the aIFC (TUS to the daINS), 44.9 ± 4.9 % for spTMS to the vpIFC (TUS to the aIFC), and 43.7 ± 5.1 % for spTMS to the aIFC (TUS to the vpIFC). Ultrasound intensity fields and temperature increase after sonication were also simulated (estimated intracranial intensities: ISPPA = 13.5 ± 1.8 W/cm2 [mean ± SD] and ISPTA = 4.1 ± 0.6 W/cm2 for TUS to the daINS, ISPPA = 12.1 ± 2.6 W/cm2 and ISPTA = 3.6 ± 0.8 W/cm2 for TUS to the vpIFC, and ISPPA = 13.7 ± 2.6 W/cm2 and ISPTA = 4.1 ± 0.8 W/cm2 for TUS to the aIFC; estimated temperature increase: 0.2 ± 0.1 °C [brain] and 0.4 ± 0.2 °C [skull] for TUS to the daINS, 0.3 ± 0.2 °C [brain] and 0.5 ± 0.3 °C [skull] for TUS to the vpIFC, and 0.5 ± 0.2 °C [brain] and 0.8 ± 0.2 °C [skull] for TUS to the aIFC).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Source data

Acknowledgements

We thank T. Kamiya for technical assistance. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 21K07255 to T.O., 22K07334 to A.O., and 23H02783 to S.K., a grant from Brain Science Foundation to T.O., a grant from Takeda Science Foundation to S.K., and a Grant-in-Aid for Special Research in Subsidies for ordinary expenses of private schools from The Promotion and Mutual Aid Corporation for Private Schools of Japan.

Author contributions

T.O. and S.K. designed the study. T.O., K.N., T.S., A.O., S.O., K.K., S.A., Y.O., S.T., and S.K. conducted experiments. T.O. and S.K. analyzed the data. T.O. and S.K. wrote the manuscript, with comments from all authors.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Maximilian Friehs and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

The MRI data that support the findings of this study are available at Dryad (10.5061/dryad.c866t1ggj), except for raw image data. The raw image data cannot be deposited in a public repository because sharing raw image data was not included in the informed consent. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The data analyses were performed using freely available codes of HCP pipelines (https://github.com/Washington-University/HCPpipelines), FSL, and SPM.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Takahiro Osada, Email: tosada@juntendo.ac.jp.

Seiki Konishi, Email: skonishi@juntendo.ac.jp.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-024-54564-9.

References

- 1.Verbruggen, F. & Logan, G. D. Response inhibition in the stop-signal paradigm. Trends Cogn. Sci.12, 418–424 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bari, A. & Robbins, T. W. Inhibition and impulsivity: behavioral and neural basis of response control. Prog. Neurobiol.108, 44–79 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hannah, R. & Aron, A. R. Towards real-world generalizability of a circuit for action-stopping. Nat. Rev. Neurosci.22, 538–552 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ikarashi, K. et al. Response inhibitory control varies with different sensory modalities. Cereb. Cortex32, 275–285 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friehs, M. A. et al. A touching advantage: cross-modal stop-signals improve reactive response inhibition. Exp. Brain Res.242, 599–618 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chambers, C. D., Garavan, H. & Bellgrove, M. A. Insights into the neural basis of response inhibition from cognitive and clinical neuroscience. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev.33, 631–646 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aron, A. R., Robbins, T. W. & Poldrack, R. A. Inhibition and the right inferior frontal cortex: one decade on. Trends Cogn. Sci.18, 177–185 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aron, A. R., Fletcher, P. C., Bullmore, E. T., Sahakian, B. J. & Robbins, T. W. Stop-signal inhibition disrupted by damage to right inferior frontal gyrus in humans. Nat. Neurosci.6, 115–116 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chambers, C. D. et al. Executive “brake failure” following deactivation of human frontal lobe. J. Cogn. Neurosci.18, 444–455 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verbruggen, F., Aron, A. R., Stevens, M. A. & Chambers, C. D. Theta burst stimulation dissociates attention and action updating in human inferior frontal cortex. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA107, 13966–13971 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Osada, T. et al. Parallel cognitive processing streams in human prefrontal cortex: parsing areal-level brain network for response inhibition. Cell Rep.36, 109732 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choo, Y., Matzke, D., Bowren, M. D. Jr., Tranel, D. & Wessel, J. R. Right inferior frontal gyrus damage is associated with impaired initiation of inhibitory control, but not its implementation. Elife11, e79667 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fine, J. M., Mysore, A. S., Fini, M. E., Tyler, W. J. & Santello, M. Transcranial focused ultrasound to human rIFG improves response inhibition through modulation of the P300 onset latency. Elife12, e86190 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Osada, T. et al. An essential role of the intraparietal sulcus in response inhibition predicted by parcellation-based network. J. Neurosci.39, 2509–2521 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.He, Q., Geißler, C. F., Ferrante, M., Hartwigsen, G. & Friehs, M. A. Effects of transcranial magnetic stimulation on reactive response inhibition. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev.157, 105532 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hampshire, A., Chamberlain, S. R., Monti, M. M., Duncan, J. & Owen, A. M. The role of the right inferior frontal gyrus: inhibition and attentional control. Neuroimage50, 1313–1319 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharp, D. J. et al. Distinct frontal systems for response inhibition, attentional capture, and error processing. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA107, 6106–6111 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Erika-Florence, M., Leech, R. & Hampshire, A. A functional network perspective on response inhibition and attentional control. Nat. Commun.5, 4073 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cai, W., Ryali, S., Chen, T., Li, C. S. & Menon, V. Dissociable roles of right inferior frontal cortex and anterior insula in inhibitory control: evidence from intrinsic and task-related functional parcellation, connectivity, and response profile analyses across multiple datasets. J. Neurosci.34, 14652–14667 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aron, A. R. From reactive to proactive and selective control: developing a richer model for stopping inappropriate responses. Biol. Psychiatry69, e55–e68 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jahanshahi, M., Obeso, I., Rothwell, J. C. & Obeso, J. A. A fronto-striato-subthalamic-pallidal network for goal-directed and habitual inhibition. Nat. Rev. Neurosci.16, 719–732 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aron, A. R., Behrens, T. E., Smith, S., Frank, M. J. & Poldrack, R. A. Triangulating a cognitive control network using diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and functional MRI. J. Neurosci.27, 3743–3752 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li, C. S., Yan, P., Sinha, R. & Lee, T. W. Subcortical processes of motor response inhibition during a stop signal task. Neuroimage41, 1352–1363 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Forstmann, B. U. et al. Cortico-subthalamic white matter tract strength predicts interindividual efficacy in stopping a motor response. Neuroimage60, 370–375 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rae, C. L., Hughes, L. E., Anderson, M. C. & Rowe, J. B. The prefrontal cortex achieves inhibitory control by facilitating subcortical motor pathway connectivity. J. Neurosci.35, 786–794 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wessel, J. R., Diesburg, D. A., Chalkley, N. H. & Greenlee, J. D. W. A causal role for the human subthalamic nucleus in non-selective cortico-motor inhibition. Curr. Biol.32, 3785–3791.e3 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duann, J. R., Ide, J. S., Luo, X. & Li, C. S. Functional connectivity delineates distinct roles of the inferior frontal cortex and presupplementary motor area in stop signal inhibition. J. Neurosci.29, 10171–10179 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zandbelt, B. B. & Vink, M. On the role of the striatum in response inhibition. PLOS ONE5, e13848 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jahfari, S. et al. Effective connectivity reveals important roles for both the hyperdirect (fronto-subthalamic) and the indirect (fronto-striatal-pallidal) fronto-basal ganglia pathways during response inhibition. J. Neurosci.31, 6891–6899 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakajima, K. et al. A causal role of anterior prefrontal-putamen circuit for response inhibition revealed by transcranial ultrasound stimulation in humans. Cell Rep.40, 111197 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suda, A. et al. Functional organization for response inhibition in the right inferior frontal cortex of individual human brains. Cereb. Cortex30, 6325–6335 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Legon, W. et al. Transcranial focused ultrasound modulates the activity of primary somatosensory cortex in humans. Nat. Neurosci.17, 322–329 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Verhagen, L. et al. Offline impact of transcranial focused ultrasound on cortical activation in primates. Elife8, e40541 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fomenko, A. et al. Systematic examination of low-intensity ultrasound parameters on human motor cortex excitability and behavior. Elife9, e54497 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kubanek, J. et al. Remote, brain region-specific control of choice behavior with ultrasonic waves. Sci. Adv.6, eaaz4193 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Darmani, G. et al. Non-invasive transcranial ultrasound stimulation for neuromodulation. Clin. Neurophysiol.135, 51–73 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zeng, K. et al. Induction of human motor cortex plasticity by theta burst transcranial ultrasound stimulation. Ann. Neurol.91, 238–252 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yaakub, S. N. et al. Transcranial focused ultrasound-mediated neurochemical and functional connectivity changes in deep cortical regions in humans. Nat. Commun.14, 5318 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Osada, T. & Konishi, S. Noninvasive intervention by transcranial ultrasound stimulation: modulation of neural circuits and its clinical perspectives. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci.78, 273–281 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Glasser, M. F. et al. A multi-modal parcellation of human cerebral cortex. Nature536, 171–178 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gordon, E. M. et al. Generation and evaluation of a cortical area parcellation from resting-state correlations. Cereb. Cortex26, 288–303 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schaefer, A. et al. Local-global parcellation of the human cerebral cortex from intrinsic functional connectivity MRI. Cereb. Cortex28, 3095–3114 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Glasser, M. F. WU-Minn HCP Consortium et al. The minimal preprocessing pipelines for the Human Connectome Project. Neuroimage80, 105–124 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen, W. et al. Prefrontal-subthalamic hyperdirect pathway modulates movement inhibition in humans. Neuron106, 579–588.e3 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Desrochers, T. M., Chatham, C. H. & Badre, D. The necessity of rostrolateral prefrontal cortex for higher-level sequential behavior. Neuron87, 1357–1368 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McLaren, D. G., Ries, M. L., Xu, G. & Johnson, S. C. A generalized form of context-dependent psychophysiological interactions (gPPI): a comparison to standard approaches. Neuroimage61, 1277–1286 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lambert, C. et al. Confirmation of functional zones within the human subthalamic nucleus: patterns of connectivity and sub-parcellation using diffusion weighted imaging. Neuroimage60, 83–94 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nambu, A., Tokuno, H. & Takada, M. Functional significance of the cortico-subthalamo-pallidal ‘hyperdirect’ pathway. Neurosci. Res.43, 111–117 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schmidt, R., Leventhal, D. K., Mallet, N., Chen, F. & Berke, J. D. Canceling actions involves a race between basal ganglia pathways. Nat. Neurosci.16, 1118–1124 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Critchley, H. D., Tang, J., Glaser, D., Butterworth, B. & Dolan, R. J. Anterior cingulate activity during error and autonomic response. Neuroimage27, 885–895 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Menon, V. & Uddin, L. Q. Saliency, switching, attention and control: a network model of insula function. Brain Struct. Funct.214, 655–667 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cocchi, L. et al. Functional alterations of large-scale brain networks related to cognitive control in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Hum. Brain Mapp.33, 1089–1106 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mesulam, M. M. & Mufson, E. J. Insula of the old world monkey. I. Architectonics in the insulo-orbito-temporal component of the paralimbic brain. J. Comp. Neurol.212, 1–22 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Butti, C. & Hof, P. R. The insular cortex: a comparative perspective. Brain Struct. Funct.214, 477–493 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nieuwenhuys, R. The insular cortex: a review. Prog. Brain Res.195, 123–163 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moore, C. I. et al. Neocortical correlates of vibrotactile detection in humans. J. Cogn. Neurosci.25, 49–61 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hampshire, A. & Sharp, D. J. Contrasting network and modular perspectives on inhibitory control. Trends Cogn. Sci.19, 445–452 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Allen, M. et al. Anterior insula coordinates hierarchical processing of tactile mismatch responses. Neuroimage127, 34–43 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cai, W., Chen, T., Ide, J. S., Li, C. R. & Menon, V. Dissociable fronto-operculum-insula control signals for anticipation and detection of inhibitory sensory cue. Cereb. Cortex27, 4073–4082 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Grund, M., Forschack, N., Nierhaus, T. & Villringer, A. Neural correlates of conscious tactile perception: an analysis of BOLD activation patterns and graph metrics. Neuroimage224, 117384 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Verbruggen, F. & Logan, G. D. Models of response inhibition in the stop-signal and stop-change paradigms. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev.33, 647–661 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.van Belle, J., Vink, M., Durston, S. & Zandbelt, B. B. Common and unique neural networks for proactive and reactive response inhibition revealed by independent component analysis of functional MRI data. Neuroimage103, 65–474 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Han, S. et al. More subjects are required for ventrolateral than dorsolateral prefrontal TMS because of intolerability and potential drop-out. PLOS ONE14, e0217826 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yamasaki, T., Ogawa, A., Osada, T., Jimura, K. & Konishi, S. Within-subject correlation analysis to detect functional areas associated with response inhibition. Front. Hum. Neurosci.12, 208 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fujimoto, U. et al. Network centrality reveals dissociable brain activity during response inhibition in human right ventral part of inferior frontal cortex. Neuroscience433, 163–173 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fujimoto, U. et al. Network centrality analysis characterizes brain activity during response inhibition in right ventral inferior frontal cortex. Juntendo Med. J.68, 208–211 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Verbruggen, F. et al. A consensus guide to capturing the ability to inhibit actions and impulsive behaviors in the stop-signal task. Elife8, e46323 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Logan, G. D. & Cowan, W. B. On the ability to inhibit thought and action: a theory of an act of control. Psychol. Rev.91, 295–327 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- 69.Verbruggen, F., Chambers, C. D. & Logan, G. D. Fictitious inhibitory differences: how skewness and slowing distort the estimation of stopping latencies. Psychol. Sci.24, 352–362 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hirose, S. et al. Lateral-medial dissociation in orbitofrontal cortex-hypothalamus connectivity. Front. Hum. Neurosci.10, 244 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Osada, T. et al. Functional subdivisions of the hypothalamus using areal parcellation and their signal changes related to glucose metabolism. Neuroimage162, 1–12 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ogawa, A. et al. Striatal subdivisions that coherently interact with multiple cerebrocortical networks. Hum. Brain Mapp.39, 4349–4359 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ogawa, A. et al. Connectivity-based localization of human hypothalamic nuclei in functional images of standard voxel size. Neuroimage221, 117205 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tanaka, M. et al. Dissociable networks of the lateral/medial mammillary body in the human brain. Front. Hum. Neurosci.14, 228 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ogawa, A. et al. Hypothalamic interaction with reward-related regions during subjective evaluation of foods. Neuroimage264, 119744 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Oka, S. et al. Diurnal variation of brain activity in the human suprachiasmatic nucleus. J. Neurosci.44, e1730232024 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Andersson, J. L., Skare, S. & Ashburner, J. How to correct susceptibility distortions in spin-echo echo-planar images: application to diffusion tensor imaging. Neuroimage20, 870–888 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Salimi-Khorshidi, G. et al. Automatic denoising of functional MRI data: combining independent component analysis and hierarchical fusion of classifiers. Neuroimage90, 449–468 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Robinson, E. C. et al. MSM: a new flexible framework for multimodal surface matching. Neuroimage100, 414–426 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rosvall, M. & Bergstrom, C. T. Maps of random walks on complex networks reveal community structure. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA105, 1118–1123 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Power, J. D. et al. Functional network organization of the human brain. Neuron72, 665–678 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gordon, E. M. et al. Precision functional mapping of individual human brains. Neuron95, 791–807.e7 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Friston, K. et al. Psychophysiological and modulatory interactions in neuroimaging. Neuroimage6, 218–229 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]