Abstract

Three experiments (N = 943) tested whether men (but not women) responded to gender threats with increased concern about how one looks in the eyes of others (i.e., public discomfort) and subsequent anger that, in turn, predicted attitudes about sexual violence. Consistent with predictions, for men, learning that one is like a woman was associated with threat-related emotions (public discomfort and anger) that, in turn, predicted the increased likelihood to express intent to engage in quid-pro-quo sexual harassment (Study 1), recall sexually objectifying others (Study 2), endorse sexual narcissism (Study 2), and accept rape myths (Study 3). These findings support the notion that failures to uphold normative and socially valued embodiments of masculinity are associated with behavioral intentions and attitudes associated with sexual violence. The implications of these findings for the endurance of sexual violence are discussed.

Keywords: masculinity, sexual harassment, objectification, rape myths, sexual narcissism

Sexual violence is pervasive and has been suggested to be linked to masculinity. There are an estimated 433,648 U.S. residents aged 12 and older who are sexually assaulted or raped each year, with as many as two in three sexual assaults and rapes going unreported (Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network, 2022). Psychological theory and research have attributed sexual violence to the acts of atypical men who have internalized pathologized or extreme forms of masculinity. For instance, sexual violence has been found to be associated with sexual narcissism, a form of personality disorder narcissism characterized by feelings of entitlement, grandiosity, and lack of empathy in sexual contexts (Widman & McNulty, 2010). Sexual violence has also been linked to hypermasculinity, which has been operationalized as the endorsement of masculine ideals, hostile attitudes toward women, and acceptance of sexual violence (e.g., Locke & Mahalik, 2005; Murnen et al., 2002; Seabrook et al., 2018). By contrast, feminist theorists have suggested that sexual violence is a tool of patriarchy: a normal, quotidian consequence of embodiments of culturally valued notions of masculinity that functionally intimidate women, increasing women’s likelihood of accepting their lower social status (Brownmiller, 1975; de Beauvoir, 1949/2009). The present work uses social psychological methods to explore the feminist proposition that sexual violence is linked to culturally idealized forms of masculinity that most people accept and that many men seek to embody.

The goal of the present work is to examine whether situational threats to masculinity influence men’s intent to engage in sexual violence. To consider this possibility, we define hegemonic masculinity, which is the idealized conceptualization of masculinity within a given culture that is internalized by most men. We then discuss the precarious nature of masculinity for men, compared to femininity for women (Vandello et al., 2008), as well as the conditions that inspire threats to masculinity and the consequences of threats to masculinity. Finally, we turn attention to research that links (a) situational threats to masculinity to the sexualization of women and (b) extreme forms of masculinity to sexual violence, noting the array of attitudes and behaviors that comprise and support sexual violence.

Hegemonic Masculinity

Although conceptualizations of masculinity vary across groups and contexts, within each culture there is an idealized form of masculinity, hegemonic masculinity, which is a cultural ideology that is endorsed by most people (Connell, 1995). Hegemonic masculinity links men and masculinity (but not women and femininity) to power, status, and success, functionally justifying and reinforcing the gender binary, the othering of women, and the gender hierarchy (Vescio & Schermerhorn, 2021). Hegemonic masculinity contains prescriptions of what men should be and proscriptions of what men should not be (Prentice & Carranza, 2002), which reify the gender hierarchy (Rudman et al., 2012). In contemporary Western societies, hegemonic masculinity (a) prescribes that men should be high in power, status, dominance, and be emotionally, mentally, and physically tough and (b) proscribes that men should not be feminine or associated with low status (Brannon, 1976; Courtenay, 2000; Rudman et al., 2012; Thompson & Pleck, 1986; Vescio et al., 2010). Importantly, most men internalize and strive to embody hegemonic masculine ideals, although few men actually embody these ideals (Connell, 1995).

Because hegemonic masculine ideals are internalized by most men but are hard to consistently embody, masculinity is a cherished but precarious social identity for men in a way that femininity is not for women (Bosson et al., 2009; Vandello et al., 2008). Consistent with this notion and underscoring how the gender binary is foundational to conceptualizations of masculinity, masculinity can be easily threatened in experimental contexts by leading men to believe that they are like women. Threats to masculinity have been documented as a result of leading men to believe that they are like women in knowledge (Rudman & Fairchild, 2004), behavior (Bosson et al., 2005), gendered traits (Maass et al., 2003), personality (Weaver & Vescio, 2015), and ability (Dahl et al., 2015). Learning that one is similar to a gender to which one does not self-identify has been found to produce threat-related emotions in men, but not women (Vescio et al., 2021; c.f., Konopka et al., 2021, Study 1; Stanaland & Gaither, 2021). Among men, gender threats have been found to be associated with concern about how one looks in the eyes of others (or public discomfort) and anger (Dahl et al., 2015; Vescio et al., 2021), anxiety (Vandello et al., 2008, Study 4), general negative affect (Valved et al., 2021), and guilt and shame (Vescio et al., 2021). Following gender threats, unlike women, men also reported reductions in empathy, a prosocial emotion that facilitates helping and smoothing interpersonal and intergroup relations (Vescio et al., 2021). These findings show that (a) gender threats tend to produce emotions consistent with an identity threat in men but not women and (b) men experience these emotions in response to a gender threat but not a threat to other social identities (Vescio et al., 2021, Study 3).

Threats to masculinity have been found to inspire compensatory acts of dominance and aggression in men, which may functionally appease threats to masculinity and reestablish one as a powerful, dominant, and “good man” (Bosson et al., 2009; Vandello et al., 2008). These compensatory acts include status reinforcing and maintaining acts of aggression, dominance, sexism, or heterosexism. For instance, following gender threats, men (but not women) more strongly endorse aggressive war tactics (Willer et al., 2013) and are less supportive of transgender rights (Harrison & Michelson, 2019) and gender equality (Kosakowska-Berezecka et al., 2016). Because learning that one is similar to a gender to which one does not self-identify represents a gender threat for men, but not women, a great deal of research has focused exclusively on men. This work has shown that threats to masculinity inspire physical aggression (Bosson et al., 2009), ideological dominance and prejudice toward women (Dahl et al., 2015), denial of social inequities (Weaver & Vescio, 2015), anti-gay prejudice (Brown & Smith, 2021; Schermerhorn & Vescio, 2022), and violence toward gay men (Parrott & Zeichner, 2008), as well as the acceptance of and lack of intervention in violence toward gay men (Schermerhorn & Vescio, 2022).

Sexual Violence as Compensatory Masculinity

Like acts of dominance and physical aggression more generally, we hypothesized that situational threats to men’s internalized hegemonic masculine ideals would arouse men’s intent to engage in sexual violence. This hypothesis extends and integrates three lines of research, which we review below. First, we briefly discuss theory and research that links threats to masculinity to the sexual objectification of threatening women. Second, we note theoretical linkages that posit sexual objectification as a foundation for sexual violence. Third, we review prior work linking the participation in and acceptance of sexual violence to more extreme forms of masculinity to highlight the novel contribution of the present work.

The sexual objectification of threatening women has been suggested to provide men with a route to reestablish male dominance following threats to masculinity (Vescio & Kosakowska-Berezecka, 2020). The sexual objectification of threatening women may effectively appease threats to masculinity because traditional gender roles and heterosexual courtship rituals link dominance to men and masculinity and submission to women and femininity (Sanchez et al., 2012). These associations can be activated (consciously or unconsciously) to appease threats to masculinity by reinforcing and highlighting male dominance without requiring specific interpersonal actions, which dimishes women’s power and agency and leads to them being perceived more like objects than people (Cikara et al., 2011; Gervais et al., 2011, 2012). Consistent with this logic, prior work found that masculinity threats stemming from being outperformed by a woman in a masculine domain serially produced feelings of public discomfort (or concern about public image) and subsequent anger that, in turn, predicted the sexualization of threatening women (Dahl et al., 2015). These findings are consistent with the notion that the objectification of women is an act of compensatory masculinity that appeases threats to masculinity. However, objectification also produces adverse and status quo maintaining consequences for women. For instance, women who are objectified exhibit decrements in cognitive performance (Gervais et al., 2011; Wiener et al., 2013), which further temper ongoing threats (Vescio et al., 2010).

The sexualization and objectification of women in interpersonal contexts has also been suggested to normalize and strengthen the activation of gendered associations of dominance and submission, providing a foundation for more extreme forms of dominance over women (Gervais & Eagan, 2017). Sexual objectification occurs when a person’s, typically a woman’s, “sexual parts or functions are separated out from her person, reduced to the status of mere instruments, or else regarded as if they were capable of representing her” (Bartky, 1990, p. 35). Sexual objectification refers to treating someone as a sexual thing rather than a complex person (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997; Gervais & Eagan, 2017). Like sexual violence more generally, sexual objectification experiences range on a continuum from subtle to overt, including body gazes and body comments to unwanted explicit sexual advances (see Gervais & Eagan, 2017). Because even the subtle sexualization and objectification of others is associated with dehumanization (for a review see Heflick & Goldenberg, 2014), objectification likely paves the way for the perpetuation of violence (Gervais et al., 2014; Loughnan et al., 2013).

The relation between the sexual objectification of women, on one hand, and sexual violence, on the other hand, is clear in the definition of sexual harassment. Sexual harassment is generally defined as verbal or physical behavior of a sexual nature that is unwelcome by the victim (e.g., Maass et al., 2003). As such, the term sexual harassment covers a wide range of phenomenon, which falls into three general categories moving from implicitly threatening to explicitly violent (Fitzgerald et al., 1988). First, on the implicitly threatening end of the spectrum, gender harassment refers to verbal and nonverbal behaviors that convey insulting, hostile, or degrading attitudes toward women. Common examples of this form of harassment include the distribution of pornographic material, sexual epithets, and insults (Maass et al., 2003). The second category includes unwanted sexual attention (e.g., jokes, complements, sexual advances; see Fitzgerald et al., 1995) and unwanted experiences as the target of objectification (e.g., body gazes, comments; Gervais & Eagan, 2017). The third category includes the most extreme form of sexual harassment—sexual coercion—and is represented by the prototypic image of a boss using one’s position of power to sexually bully and/or blackmail a subordinate woman, or quid-pro-quo sexual harassment.

The self-reported likelihood to engage in quid-pro-quo sexual harassment (e.g., job assignments, promotions, Pryor, 1987) is associated with extreme forms of masculinity (e.g., sexual narcissism, hypermasculinity). For instance, authoritarianism predicted men’s self-reported likelihood to engage in quid-pro-quo sexual harassment, and that relation was mediated by men’s endorsement of rape myths and endorsement of hostile sexism (Begany & Milburn, 2002). Men high in beliefs that some groups should dominate others also reported a greater likelihood to engage in quid-pro-quo sexual harassment following an interaction with a feminist or after learning that one is more like a woman (vs. a man, Maass et al., 2003).

Extending prior work, we predict that quotidian experiences of threats to masculinity will be associated with men’s self-reported intent to engage in quid-pro-quo sexual harassment, consistent with the theorizing of feminist scholars (e.g., Brownmiller, 1975). In other words, if sexual objectification provides a foundation for more extreme forms of dominance over women (Gervais & Eagan, 2017), then situational threats to masculinity would be associated with parallel patterns of findings on men’s intent to engage in quid-pro-quo sexual harassment and their likelihood to sexually objectify women. Consistent with this logic, we predicted that gender threats in men (but not women) will lead to increased feelings of public discomfort and subsequent anger that, in turn, predict sexual dominance as a form of compensatory masculinity (Dahl et al., 2015). Whereas prior work showed that sexual dominance took the form of the sexualization of threatening women (Dahl et al., 2015), we here predict that threat (i.e., public discomfort and anger) will, in turn, predict the self-reported intent to engage in sexual violence.

Overview of the Hypotheses and Present Research

Three experiments tested our hypothesis that masculinity threats would lead to increased feelings of public discomfort and subsequent anger that, in turn, predict intent to engage in sexual violence and/or positive attitudes toward sexual violence. To test hypotheses, we used serial mediation, moderated by participant gender in Studies 1 and 2. As discussed above, masculinity threats inspire a host of negative emotions (e.g., Stanaland & Gaither, 2021; Valved et al., 2021; Vandello et al., 2008; Vescio et al., 2021). Building upon and replicating previous research (Dahl et al., 2015; Schermerhorn & Vescio, 2022), we predict that men will first experience increased public discomfort (or concern about one’s public image) following threats to their masculinity. This is because masculinity is performed by men for men and being seen as a “good man” requires the acknowledgment of others (Kimmel, 2008); therefore, failing to be seen as masculine has been found to lead to concern about how one is viewed by others (Dahl et al., 2015). We predict that public discomfort then leads to anger, consistent with research showing that the expression of anger assuages men’s feelings of discomfort associated with their threatened masculinity (Jakupk et al., 2005) and anger, in turn, leads to compensatory attitudes and behaviors meant to reestablish them as “good men” (Dahl et al., 2015; Schermerhorn & Vescio, 2022). Importantly, previous research testing this model has failed to produce evidence that anger may precede public discomfort (Dahl et al., 2015; Schermerhorn & Vescio, 2022).

Studies 1 and 2 recruited participants across the gender identification spectrum, while Study 3 only included men. As a result, Studies 1 and 2 tested a moderated mediation model, whereas Study 3 tested a serial mediation model. A priori power analyses are difficult to perform for tests of serial mediation given estimates of indirect effects are required to test hypotheses (Hayes, 2018). Therefore, we based our sample size on prior work testing both serial mediation (Ns = 96–194; Dahl et al., 2015) and moderated serial mediation (Schermerhorn & Vescio, 2022; Ns = 270–369). All studies were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the authors’ home institution. For each study, all measures and analyses are reported. All analyses were conducted upon completion of data collection. The data and syntax for all analyses and the preregistration for Study 2 are available at https://osf.io/9zf6s/.

Study 1

Method

Participants

Participants were men (N = 123) and women (N = 154) recruited from Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (N = 277). Participants had a mean age of 36.89 years (age range: 19–67) and self-identified as African American (10.5%), Asian (6.9%), Latino/a (6.1%), Native American (2.9%), White (79.4%), or other racial identity (0.7%). Percentages add up to more than 100% because participants could select multiple racial identities.

Procedure

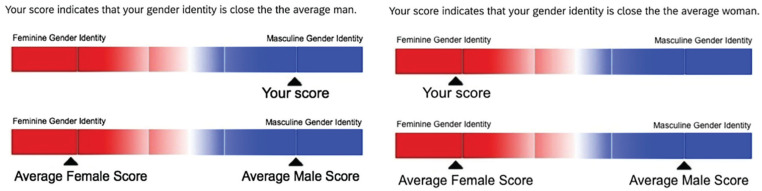

Study 1 used a participant gender (male, female) by gender feedback (like a man, like a woman) between-participants design. After providing consent, participants completed a gender knowledge test composed of 30 multiple-choice questions (Rudman & Fairchild, 2004). Half of the questions were about stereotypically feminine content (e.g., During pregnancy, morning sickness usually occurs in which trimester [second vs. first]?), and half about stereotypically masculine content (e.g., A dime is what kind of play in football [offensive vs. defensive]?). Participants received feedback that was varied to create gender threat and gender assurance conditions. As shown in Figure 1, participants learned of their own (false) scores, as well as the purported average scores of men and women in the United States by means of a visual spectrum anchored with endpoints “Feminine Gender Identity” and “Masculine Gender Identity.” Participants either learned their score was like the average woman or average man. Participants then completed measures of public discomfort, anger, and their self-reported likelihood to sexually harass someone of another gender.

Figure 1.

Gender Feedback for the Average Male (Left) and the Average Female (Right), Study 1.

Dependent Measures

Public Discomfort

As in prior work (Dahl et al., 2015), using a 7-point scale (1 = not at all; 7 = very), participants imagined that their scores on the gender test were made public and answered the following question for each of eight emotions: “When you think about your name and score being published, how _____ (anxious, nervous, defensive, depressed, calm, joyful, happy, and confident) do you feel?” After reverse scoring appropriate items, we averaged emotions to create a public discomfort variable (α = .90).

Anger

Using a 9-point scale (1 = not at all; 9 = extremely), participants then reported the extent to which—“at this moment”—they felt four emotions that tap anger (i.e., angry, frustrated, hostile, and mad), which were intermixed with six filler items (i.e., relaxed, competent, happy, anxious, depressed, proud); we averaged across the four anger emotions to create an anger variable (α = .92).

Likelihood to Sexually Harass

Participants read and responded to six scenarios from the Likelihood to Sexually Harass Scale (Pryor, 1987). For each scenario, participants imagined themselves as the protagonist in a situation where someone of their gender had power over someone of the other gender. In other words, men read about other men having power over women and women read about other women having power over a man. Using a 7-point scale (1 = not at all likely, 7 = very likely), and considering each scenario, participants then indicated: (a) how likely they would be to offer an opportunity to the subject, (b) how likely they would be to exchange the opportunity for “sexual favors,” and (c) how likely they would be to offer to meet for dinner to discuss the topic in the scenario. Responses of (b) to each scenario, which indicate quid-pro-quo sexual harassment (see Pryor, 1987), were averaged across the six scenarios (α = .97); higher scores indicated a greater likelihood to engage in quid-pro-quo sexual harassment.

Results

We predicted moderated serial mediation that may involve the absence of significant direct and/or total effects. In fact, when effects sizes are small, significant indirect effects demonstrate the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable even when total effects are insignificant (Kenny et al., 1998; LeBreton et al., 2009; Preacher & Hayes, 2008; Shrout & Bolger, 2002; Zhao et al., 2010). However, evidence of direct effects of feedback (like a man, like a women) and participant gender (man, woman) resulting from between-participants analyses of variance (ANOVAs) performed on each dependent variable and are reported in Supplemental Materials (see Supplemental Table S1).

To test predictions, we conducted a series of moderated mediation analyses using PROCESS Model 83 for SPSS (Hayes, 2018). We used 5,000 bootstrap samples to create 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Feedback (−1 = like men, 1 = like women) was entered as the dependent variable while participant gender (1 = male, −1 = female) was entered as the moderator. Public discomfort and anger were entered as the mediators and the likelihood to sexually harass was entered as the dependent variable. We tested for moderation of the path leading from threat to public discomfort and examined the index of moderated mediation to test the conditional indirect effect separately for men and women (Hayes, 2018; see also Hayes, 2015).

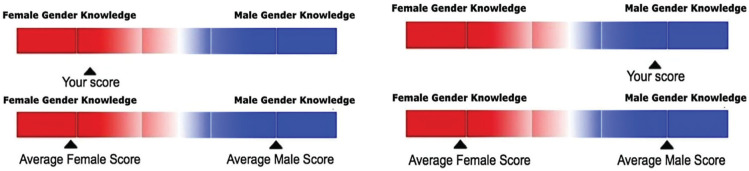

Consistent with hypotheses, as shown in Figure 2, participant gender interacted with feedback in predicting public discomfort while neither participant gender nor gender feedback independently predicted public discomfort. Receiving feedback that one was like women was associated with more public discomfort in men, b = .52, SE = .11, t(273) = 4.56, p < .001, 95% CI = [.2971, .7493], and less public discomfort for women, b = −.44, SE = .10, t(273) = −4.35, p < .001, 95% CI [−.6458, −.2431]. Public discomfort, in turn, predicted increased anger and anger predicted a greater likelihood to sexually harass. As hypothesized, the index of moderated mediation was significant (Index = .2322, SE = .0799, 95% CI = [.0890, .4024]). However, because the conditional indirect effect was significant for both men, IE = .1256, SE = .0488, 95% CI = [.0430, .2322], and women, IE = −.1067, SE = .0402, 95% CI = [−.1942, −.0373], we conducted mediation analyses separately for men and women to probe the moderated mediation.

Figure 2.

Moderated Mediation of Gender Threatening Feedback on Likelihood to Sexually Harass (Pryor, 1987), Study 1.

Note. *<.05. **<.01. ***<.001.

Consistent with hypotheses, when mediation analyses were performed separately for men and women (using PROCESS Model 6; Hayes, 2018), the indirect effect was significant for men, IE = .1754, SE = .0786, 95% CI = [.0435, .3489], but not women, IE = −.0371, SE = .0290, 95% CI = [−.0978, .0171]. As shown in Figure 3 (Panel A), among men, gender threat predicted more public discomfort and public discomfort predicted anger that was, in turn, associated with a greater likelihood to sexually harass. By contrast, for women (see Figure 3, Panel B), gender threat predicted more public discomfort and public discomfort predicted more anger, but anger did not predict a greater likelihood to sexually harass.

Figure 3.

Serial Mediation of Gender Threatening Feedback on Likelihood to Sexually Harass (Pryor, 1987) for Men (Panel A) and Women (Panel B).

Note. *<.05. **<.01. ***<.001.

Discussion

As predicted, the findings of Study 1 show that threats to masculinity inspire unique compensatory acts of sexual dominance in men that threats to femininity do not inspire in women. Specifically, after learning that one’s gender knowledge was like that of the average woman (vs. man), men reported greater feelings of public discomfort and subsequent anger that, in turn, predicted men’s greater self-reported likelihood to engage in quid-pro-quo sexual harassment. By contrast, although women also felt more public discomfort and subsequent anger in the gender threat conditions, anger did not, in turn, predict a greater likelihood that women would sexually harass men.

The findings of Study 1 replicated and extended two prior works. First, Study 1 findings replicated prior findings, which showed that threats to masculinity serially inspired public discomfort, anger, and the subsequent sexualization of threatening women (Dahl et al., 2015). However, whereas previous work showed that threats to masculinity predicted subtle forms of sexualization (i.e., how scantily clad participants chose to dress avatars representing their female teammates, Dahl et al., 2015), the findings of Study 1 showed that the predicted patterns of serial mediation predicted men’s explicitly stated intent to engage in quid-pro-quo sexual harassment. The findings of Study 1 also replicated and extended the work of Maass and her colleagues (2003). Whereas Maass et al. (2003) found that threats to masculinity inspired sexual violence among men who were high (but not low) in social dominance orientation, the present findings link threats to masculinity generally to sexual harassment. The present findings also shed light on the threat-related emotions that may inspire elevated intentions to engage in the quid-pro-quo sexual harassment of women, which may inform questions about the kind of men (e.g., high social dominance oriented) and the kind of situations (e.g., masculinity-threatening situations) that encourage sexual harassment. We will return to this point in the general discussion.

Interestingly, although the predicted pattern of serial mediation emerged was significant for men and not women, as we predicted, both men and women displayed a threat response in contrast to predictions. Following the receipt of gender-atypical (vs. typical) feedback, both men and women reported increased public discomfort and subsequent anger. We predicted that men (but not women) would feel threatened, as evidenced by increased public discomfort and anger. In hindsight, we suspect that women, like men, in Study 1 felt public discomfort given how we inadvertently linked feedback on the gender knowledge test to “gender identity” and internal characteristics of participants. As shown in Figure 1, participants learned that their scores were located either closer to a masculine gender identity or a feminine gender identity. Interestingly, fears of backlash are experienced in result to confrontation with gender proscriptions; for men, low status behaviors that embody weakness are proscribed, whereas for women, high status agentic and dominance behaviors are proscribed (Rudman et al., 2012). In tying our feedback to gender identity, we may have inadvertently implied personality or dispositional attributes in women that arouse fears of backlash. By contrast, for men, hegemonic masculinity proscribes being feminine, unmanly, or low status and learning that one is like a woman would arouse threat regardless of the specific anchoring of the feedback.

As noted, research has generally documented that men, but not women, experience gender threats. In fact, to the best of our knowledge, there are only two exceptions to that general finding. Interestingly, the two exceptions are studies that used experimental materials that may have also focused on personality and dispositional attributes (Konopka et al., 2021; Stanaland & Gaither, 2021). To address this possibility, in Study 2, we changed the labels that anchored the feedback to the gender knowledge test.

Study 2

In Study 2, we turn attention to the question of whether situational threats to masculinity may be linked to the explicit sexual objectification of others in ways that parallel the findings of Study 1. Because objectification is linked to dehumanization (Rudman & Mescher, 2012), sexual objectification may provide a foundation for more extreme forms of sexual violence (see Gervais & Eagan, 2017). Recent findings reveal that sexual objectification is associated with sexual violence or the self-reported involvement in forced sexual contact (Gervais et al., 2018). For instance, the frequency with which people self-report that they have sexually objectified others in interactions is correlated with self-reported instances of sexual violence (Gervais et al., 2018). Therefore, Study 2 tested the prediction that situational threats to masculinity would lead to parallel patterns of results as found in Study 1 but on sexual objectification; gender-atypical feedback would lead to threat responses in men, but not women (i.e., public discomfort and subsequent anger) that, in turn, would predict increases in reported past sexual objectification.

Study 2 was also designed to test whether sexual narcissism might vary as a function of masculinity threat condition. As we noted at the outset, prior research has linked sexual violence to pathologized and extreme masculine identities. For instance, sexual violence has been found to be associated with sexual narcissism, a personality disordered form of entitlement, grandiosity, and lack of empathy in sexual contexts (Widman & McNulty, 2010). While narcissism is typically viewed in dispositional terms, recent research shows that ego threats can result in state narcissism, which predicts aggression (Li et al., 2016). Therefore, we predicted that situational threats to masculinity would predict public discomfort and subsequent anger that, in turn, would predict the greater endorsement of sexual narcissism (Study 2).

Method

Participants

We based sample size on the effects found in Study 1 and previous work requiring 280 to 300 participants. However, because prior documented associations between the perpetration of sexual objectification and sexual narcissism, on one hand, and sexual violence, on the other hand, were small and because there are gender differences that have been documented on both sexual objectification (Gervais et al., 2018) and sexual narcissism (Widman & McNulty, 2010), we increased the desired sample size and recruited 250 men and 250 women to assure sufficient power. Participants (N = 501) were recruited from the Pennsylvania State University psychology subject pool and received partial course credit for their participation. Participants (Mage = 18.92, age range: 18–28) included 251 men (250 cisgender, 1 transgender) and 250 women (249 cisgender, 1 transgender) participants who self-identified as African American (6.2%), Asian (11.6%), White (76.9%), Biracial/Multiracial (2.6%), or other racial identity (1.4%).

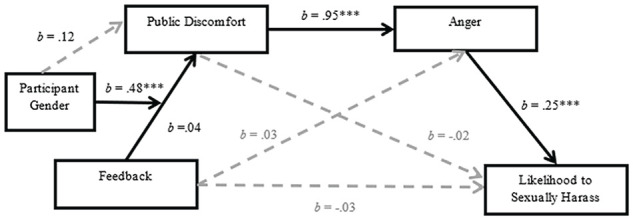

Procedure

The procedure was identical to that of Study 1 with two exceptions. First, feedback was provided using the graphic depicted in Figure 4, anchored with labels “Male Gender Knowledge” and “Female Gender Knowledge.” Second, participants completed measures of sexual objectification and narcissism rather than likelihood to sexually harass.

Figure 4.

Gender Feedback for the Average Male (Left) and the Average Female (Right), Study 2.

Dependent Measures

Public Discomfort

We used the same measure as in Study 1 (α = .84).

Anger

We used the same measure as in Study 1 (α = .90).

Sexual Objectification

Participants completed the Interpersonal Sexual Objectification Scale–Perpetration Version (Gervais et al., 2018). Using a 5-point scale (1 = never, 5 = almost always), participants indicated the frequency with which they engaged in 15 types of sexual objectification defined as body gazes (5 items, α = .80, for example, “stared at someone’s body”), body comments (6 items, α = .71, for example, “honked at someone when he/she was walking down the street”), and unwanted explicit sexual advances (4 items, α = .81, for example, “touch or fondled someone against his/her will”). We averaged across items to create a single sexual objectification score (α = .85). The same pattern of results emerged from analyses performed on overall objectification (reported in text) and the three subscales (reported in Supplemental Materials).

Sexual Narcissism

Participants also completed the Sexual Narcissism Scale (Widman & McNulty, 2010). Using a 5-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree), participants completed 20 items that assessed their sexual exploitation (5 items, α = .70, for example, “I would be willing to trick a person to get them to have sex with me”), sexual entitlement (5 items, α = .77, for example, “I should be permitted to have sex whenever I want”), sexual empathy (5 items, α = .69, for example, “I do not usually care how my sexual partner feels after sex”), and sexual skills (5 items, α = .88, for example, “I really know how to please a partner sexually”). After reverse scoring appropriate items, we averaged across all 20 items to create a single sexual narcissism score (α = .82). The same pattern of results emerged from analyses performed on overall sexual narcissism (reported in text) and the five subscales (reported in Supplemental Materials).

Results

As in Study 1, the results of feedback (like men, like women) × participant gender (male, female) ANOVAs performed on each proposed mediator and dependent variable are reported in the Supplemental Materials (see Supplemental Table S2). We then examined whether gender threat would lead to increased public discomfort, subsequent anger and, in turn, increased sexual objectification and sexual narcissism for men (but not women) by conducting a series of moderated mediation analyses using PROCESS Model 83 for SPSS (Hayes, 2018).

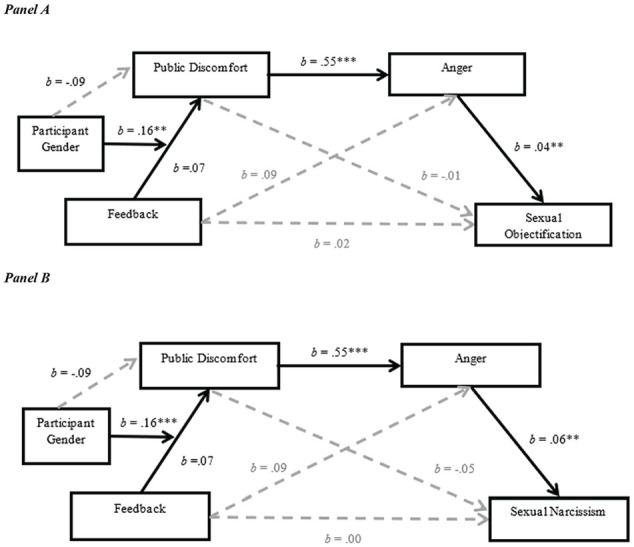

Consistent with predictions and replicating the findings of Study 1, participant gender interacted with feedback in predicted public discomfort while neither participant gender nor feedback independently predicted public discomfort (see Figure 5). Receiving feedback that one was like a woman was associated with more public discomfort in men, b = .23, SE = .07, t(497) = 3.20, p = .001, 95% CI = [.0883, .3680], but not women, b = −.08, SE = .07, t(497) = −1.18, p = .329, 95% CI = [−.2244, .0560]. Public discomfort, in turn, predicted increased anger and anger predicted increased sexual objectification (see Figure 5, Panel A) and sexual narcissism (see Figure 5, Panel B). As hypothesized, the index of moderated mediation was significant for both sexual objectification, Index = .0076, SE = .0040, 95% CI = [.0014, .0169], and sexual narcissism, Index = .0098, SE = .0048, 95% CI = [.0023, .0208]. The conditional indirect effect was significant for men (but not women) in both analyses (see Table 1). In addition, with one exception, these results held when examining individual subscales of both sexual objectification and sexual narcissism (see Table 1 for indirect effects, see Supplemental Materials, Figures S1 and S2).

Figure 5.

Moderated Mediation of Gender Threatening Feedback on Sexual Objectification (Panel A) and Sexual Narcissism (Panel B), Study 2.

Note. *<.05. **<.01. ***<.001.

Table 1.

Indirect Effects for Men and Women, Study 2.

| Subscales of Sexual Objectification & Sexual Narcissism | Indirect effects for men |

Indirect effects for women |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IE | SE | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | IE | SE | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | |

| Sexual objectification | .0056* | .0029 | .0012 | .0124 | −.0021 | .0021 | −.0070 | .0014 |

| Body comments | .0051* | .0028 | .0007 | .0116 | −.0019 | .0020 | −.0068 | .0013 |

| Body gazes | .0071* | .0040 | .0009 | .0161 | −.0026 | .0027 | −.0088 | .0018 |

| Sexual advances | .0039* | .0020 | .0009 | .0087 | −.0015 | .0015 | −.0050 | .0011 |

| Sexual narcissism | .0072* | .0033 | .0018 | .0149 | −.0026 | .0027 | −.0087 | .0022 |

| Sexual exploitation | .0098* | .0046 | .0027 | .0203 | −.0036 | .0035 | −.0114 | .0025 |

| Sexual entitlement | .0104* | .0051 | .0024 | .0221 | −.0038 | .0039 | −.0127 | .0029 |

| Sexual empathy | .0067* | .0039 | .0006 | .0154 | −.0025 | .0027 | −.0090 | .0017 |

| Sexual skills | .0018 | .0043 | −.0064 | .0109 | −.0007 | .0021 | −.0058 | .0032 |

Note. IE = indirect effect; CI = confidence interval.

Indicates a significant indirect effect.

Discussion

Consistent with predictions, men (but not women) who received gender-atypical feedback reported more public discomfort and subsequent anger that, in turn, predicted sexual objectification and sexual narcissism. These findings are consistent with predictions, as well as the pattern of findings that emerged in Study 1 on the self-reported likelihood to engage in quid-pro-quo sexual harassment. However, the findings of Study 2 are, to the best of our knowledge, the first to link threats to masculinity to overt intentions to sexually objectify others and increases in sexual narcissism.

As noted, everyday instances of objectification may provide a foundation for more extreme versions of violence (Gervais & Eagan, 2017). This may be particularly true when there is an explicit acceptance of the perpetration of sexual objectification and embracing of sexual narcissism, as in Study 2. As noted, feminists have suggested that the possibility of sexual violence is made salient by men to intimidate women, increasing the likelihood that women will accept their lower social status (Brownmiller, 1975). Although the present findings do not speak to our participants’ intent to intimidate women, our participants did explicitly report their intent to sexually harass (Study 1), as well as their intent to sexually objectify and use women as objects for their own sexual pleasure (Study 2). In other words, the present work documents conscious and explicit reports of intent regarding the sexualization, sexual objectification, and sexual harassment of women. Whether these explicit endorsements are motivated by a desire to intimidate women, or a masculine performance by men for men (Kimmel, 2008), there is a level of awareness involved that is worthy of subsequent research attention.

Finally, there is one important difference between the findings of Studies 1 and 2. Consistent with predictions, men but not women in Study 2 displayed a threat effect, as evidenced by increased public discomfort and subsequent anger in gender-atypical (vs. typical) feedback conditions. We attribute the difference across studies to the way in which feedback was provided, with women (like men) fearing backlash when concerned about the possible gender personalities and associated embodiment of gender proscribed attributes (Rudman et al., 2012). This possibility was removed in Study 2 by providing feedback in terms of gender knowledge rather than gendered identities. Importantly, however, future research should identify when and in which contexts men and women experience threat in response to gender-atypical (vs. typical) feedback, as well as articulating the conditions in which those threat responses are and are not associated with compensatory acts intended to ameliorate the threat.

Interestingly, there are two characteristics that distinguish convicted rapists from non-rapists: penile erection in response to sexual violence and callous attitudes toward rape (including endorsement of rape myths, see Pryor, 1987). Importantly, sexual violence continues to be associated with hostile attitudes toward women and endorsement of rape myths (Russell & King, 2020). However, inquiries examining the potential linkages to masculinity are limited and the handful of studies that have considered the role of masculinity in sexual violence have tended to focus on the potential role of problematic and/or extreme forms of masculinity. To extend this prior work, we predicted that situational threats to normative masculinity would result in increased endorsement of rape myths, which shifts the blame of rape from perpetrators to victims and is a well-established predictor of the acceptance of and perpetration of sexual violence (e.g., Fransher & Zedaker, 2020; Hust et al., 2019). We turn attention to this issue in Study 3.

Study 3

We recruited only male participants for Study 3; this change was made because the findings across Studies 1 and 2 revealed that gender threats in men (but not women) led to public discomfort and subsequent anger that, in turn, predicted compensatory responses. As in Studies 1 and 2, male participants were randomly assigned to receive feedback that they scored like the average man or like the average women. However, in Study 3, the dependent variable was endorsement of rape myths, which, as noted above, has been found to be strongly associated with the acceptance of sexual violence and personal participation in acts of sexual violence.

Method

Participants

Amazon’s Mechanical Turk was used to recruit 165 men who were residents of the United States and who were native English speakers. Participants had a mean age of 34.38 years (age range: 19–72) and self-identified as African American (8.5%), Asian (12.7%), White (65.5%), Latino/a (10.9%), or other racial identity (2.4%).

Procedure

The procedure of Study 3 was identical to the previous two studies; however, all participants were men, and the dependent variable was the endorsement of rape myths.

Dependent Measures

Public Discomfort

We used the same measure as in Studies 1 and 2 (α = .81). However, in Study 3, we inadvertently used a 9-point scale (1 = not at all, 9 = very).

Anger

We used the same measure as in Studies 1 and 2 (α = .95).

Rape Myths

After receiving their scores, participants completed the 45-item Illinois Rape Myth Acceptance Scale (IRMA; Payne et al., 1999) using a 7-point scale (1 = not at all agree, 7 = very much agree). The items are divided into seven subscales (with five filler items) which respectively measure the following attitudes about rape: she asked for it (eight items, α = .94, for example, “When women go around wearing low-cut tops or short skirts, they’re just asking for trouble”), it wasn’t really rape (five items, α = .93, for example, “If a woman doesn’t physically resist sex—even when protesting verbally—it really can’t be considered rape”), he didn’t mean to (five items, α = .84, for example, “When men rape, it is because of their strong desire for sex”), she wanted it (five items, α = .91, for example, “Many women secretly desire to be raped”), she lied (five items, α = .88, for example, “Women who are caught having an illicit affair sometimes claim that it was rape”), rape is a trivial event (five items, α = .91, for example, “Being raped isn’t as bad as being mugged and beaten”), rape is a deviant event (seven items, α = .90, for example, “Men from nice middle-class homes almost never rape”). We averaged across items to create an endorsement of rape myths variable (α = .98).

Results

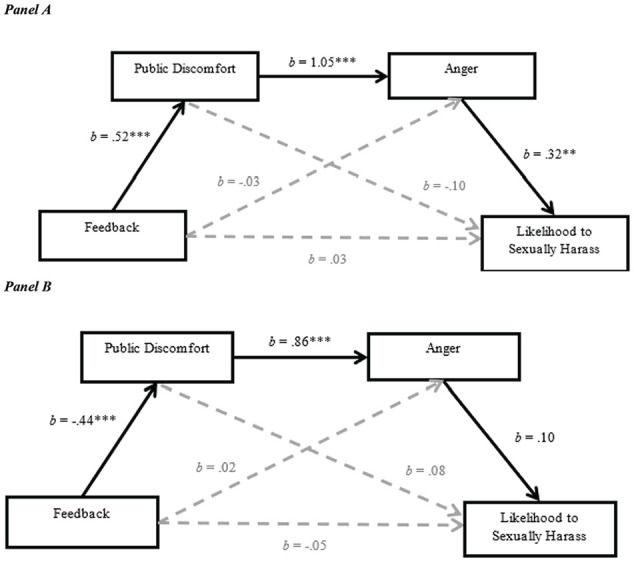

Analyses parallel those performed in Studies 1 and 2. The rape myths variable, as well as each subscale variable, was submitted to a one-way feedback (like a man, like a woman) ANOVA, the results of which are reported in the Supplemental Materials (see Supplemental Table S3). To test whether gender threat would sequentially lead to public discomfort, anger, and an increased endorsement of rape myths, we then conducted a serial mediation analysis using Process Model 6 for SPSS (Hayes, 2018) and 5,000 bootstrap samples to create 95% CIs. Gender feedback (−1 = like men, 1 = like women) was entered as the dependent variable, public discomfort and anger were entered as the mediators, and rape myths was entered as the dependent variable.

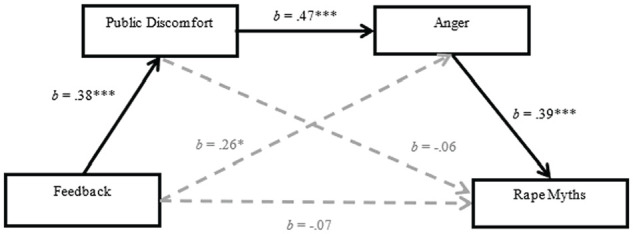

Consistent with predictions, and as shown in Figure 6, men who received feedback that they were like a woman (vs. man) reported increased public discomfort, and public discomfort predicted subsequent anger. Anger, in turn, predicted the greater endorsement of rape myths. The indirect effect of threat condition on the endorsement of rape myths was significant (IE = .0706, bootstrapped SE = .0258, 95% CI = [0.257, .1261]). These same effects emerged when looking at the individual subscales of the rape myths scale (see Table 2 and Supplemental Figure S3).

Figure 6.

Serial Mediation of Gender Threatening Feedback on Rape Myths, Study 3.

Note. *<.05. **<.01. ***<.001.

Table 2.

Indirect Effects for Rape Myths Subscales, Study 3.

| Rape Myths Subscales | IE | SE | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| She asked for it | .0661* | .0252 | .0233 | .1232 |

| It wasn’t really rape | .0793* | .0286 | .0294 | .1421 |

| He didn’t mean it | .0623* | .0246 | .0220 | .1186 |

| She wanted it | .0605* | .0249 | .0201 | .1156 |

| She lied | .0658* | .0254 | .0239 | .1212 |

| Rape is trivial | .0852* | .0299 | .0333 | .1503 |

| Rape is deviant | .0759* | .0274 | .0271 | .1345 |

Note. IE = indirect effect; CI = confidence interval.

Indicates a significant indirect effect.

Discussion

Consistent with predictions, the results of Study 3 revealed that men who were led to believe that they exhibited knowledge typical of the average woman (vs. man) experienced masculinity threats, as evidenced by increased public discomfort and subsequent anger; in turn, anger predicted the greater acceptance of rape myths. Following a masculinity threat (vs. assurance), men downplayed the severity of rape by endorsing myths that alleviate blame from men who rape, blame women who are raped, and trivialize the experience of consent and rape. These effects were significant when overall rape myth acceptance scores were analyzed, as well as when scores on each subscale were analyzed (see Supplemental Materials). To the best of our knowledge, the findings of Study 3 are the first to link situational threats to masculinity to the endorsement of rape myths, which is one of the strongest predictors of the acceptance of sexual violence and the participation in sexual violence (e.g., Fransher & Zedaker, 2020; Hust et al., 2019).

General Discussion

Three studies examined whether threats to masculinity serially predicted increases in public discomfort and subsequent anger that, in turn, were associated with expressed intent to engage in sexual violence and attitudes that support sexual violence. Across studies, we examined the indirect effects of gender-atypical (vs. typical) feedback on increases in men’s explicit expression of intent to engage in quid-pro-quo sexual harassment and objectify women. We also examined the effect of threats to masculinity on increased endorsement of sexual narcissism, or the lack of sexual empathy and elevated desire to use others for one’s own sexual gratification, and endorsement of rape myths, which shift the blame for sexual violence from perpetrators to victims.

Across three studies, the predicted pattern of serial mediation emerged on each variable. Men (but not women) displayed significant patterns of serial mediation; among men, gender threat led to public discomfort, subsequent anger, and an increased intent to engage in quid-pro-quo sexual harassment (Study 1) and sexual objectification (Study 2). Further consistent with predictions, men but not women responded to feedback that they were gender-atypical with increased public discomfort, subsequent anger, and elevated sexual narcissism (Study 2). The men in Study 3 also displayed the predicted pattern, with masculinity threat leading to greater endorsement of rape myths via public discomfort and subsequent anger.

As noted, however, women in Studies 1 and 2 responded differently. Women in Study 1 expressed threat (i.e., public discomfort and anger) while women in Study 2 did not. We attributed those divergent patterns to the differing labels used to anchor the feedback (see Figures 1 and 4), which may have differentially implied gendered personality and/or dispositions. While these speculations are post hoc, the differences point to the need to understand when women do and do not experience threat in response to gender atypicality and to examine whether aroused public discomfort and anger are associated with the same kind of threat for men and women.

The findings of Studies 1 through 3 extend prior work in several novel and important ways. First, the present findings show that situational threats to gender inspire men’s intent to engage in quid-pro-quo sexual harassment (Study 1), objectify women (Study 2), and use women for their own sexual pleasure without regard to women’s needs (Study 2). Because all dependent variables involve the explicit report, the present findings link situational threats to masculinity to men’s explicit intent to dominate women. This diverges from prior work (Dahl et al., 2015), which suggested that the sexualization of women would only occur following threats to masculinity on subtle measures of sexualization that allow for the operation of nonconscious processes.

Second, the present findings show that rather mundane, quotidian experiences of threats to masculinity inspire threat-related emotions (public discomfort and anger) that predict subsequent intentions to dominate women and minimize the severity of sexual violence. Importantly, most men in these studies did not strongly endorse sexual violence (for distributions see Supplemental Materials, Figures S4–S7). However, given the explicit nature of our dependent variables, it is concerning that men are self-reporting a greater likelihood to engage in sexual harassment and sexual objectification, as well as more strongly endorsing sexual narcissism and rape myths. As noted, these are all factors that are linked to more serious forms of sexual violence. Our current findings suggest that men who experience negative emotions (public discomfort and anger) following threats to their masculinity more strongly endorse sexual violence. It is possible that masculinity threats are experienced more strongly by some kinds of men (e.g., men high in social dominance orientation; Maass et al., 2003) or in some kinds of situations (e.g., male domains), contributing to possible mechanisms that may operate across situations and people.

The present findings are consistent with the notion that there is a continuum of sexual violence with one end of the continuum anchored by relatively subtle behaviors, like objectifying gaze and appearance remarks, and the other end anchored by more violent and blatant behaviors, like assault and harassment (Gervais et al., 2011). In addition, whereas prior work has linked the tendency to sexually objectify others to the self-reported engagement in sexual acts without consent (Gervais & Eagan, 2017, see also Riemer et al., 2022), the present findings highlight masculinity threat as a critical factor that may motivate sexual objectification, which has been suggested to provide a foundation for more extreme forms of sexual violence. These findings are striking when considered in relation to recent work showing that masculinity threat is also associated with decreases in empathy, a prosocial emotion that may prevent violence more generally (Vescio et al., 2021).

There are also limitations of the present set of studies that should be addressed in future work. First, across three studies, we relied on a single manipulation of gender threat: in all cases people were led to believe that they responded in a gender-atypical or gender-typical manner. Masculinity has also been shown to be threatened when men are outperformed by women in masculine domains (Dahl et al., 2015), when men perform gender-atypical tasks (hair braiding, Bosson et al., 2009), and when heterosexual men are targets of the sexual advance of a gay man (Schermerhorn & Vescio, 2022). Theoretically, threats to masculinity would also be expected to occur whenever men are relatively low in power, status, dominance, and/or toughness, particularly relative to a woman given heterosexual interdependencies.

Second, all the dependent variables in the present research were self-reported and we only measured two threat-related emotions. As noted, these measures were selected because they are explicit and have been directly linked to the enactment of sexual violence in past research. However, future research should examine actual behavior and the conditions under which and for what men self-reported intent leads to actual behavior. The present research measured two threat-related emotions (public discomfort and anger); however, research has shown masculinity threats lead to a host of other emotions including shame, guilt, and a reduction in empathy (Vescio et al., 2021). Recent research has also shown that extrinsic (vs. intrinsic) pressures to appear masculine lead men to behave in more aggressive ways following threats to their masculinity (Stanaland et al., 2023). Thus, future work should examine additional factors that lead men to behaviorally enact sexual violence following threats to their masculinity.

In the case of masculinity theory and research, this becomes a particularly important avenue for future research. It is possible that the findings documented represent a masculine posturing that does not map onto the actual enactment of sexual violence, instead suggesting that it may be better for men—at least young men who represent this sample—to behave badly, as dominant men than to be unmanly and weak. However, should future research document this tendency, the present findings are still critical to understanding the role of complicit masculinity in the perpetuation of male dominance and sexual violence. For instance, as Pascoe (2007) noted in her study of the socialization of masculinity in adolescence, few boys engage in the violence associated with forcible maintenance of the status quo, but many more boys remain silent and engage in banter that normalizes gender-based violence and sexual violence.

Third, the participants in the present work are predominantly White men and women and there are critical differences in the content of hegemonic masculinity within and across groups and cultures (hooks, 2004). In contemporary American society, hegemonic masculinity is racialized and, as a result, may be embodied with fewer barriers when men are White, straight, able-bodied, and middle class, versus members of marginalized masculinities (due to race, sexual orientation, religion, socio-economic status). It is not clear whether threats to masculinity would be similarly or differently associated with acts of compensatory dominance among men whose intersecting identities render them members of groups that are marginalized or subordinated masculinities. Participants also all identified as men or women, leaving questions about how non-binary people respond to gendered feedback and how binary people respond to non-binary feedback. Future research is needed to examine whether the content and consequences of sexual dominance, sexual harassment, and sexual violence vary as a function of the intersecting race, ethnicity, culture, and socio-economic status of women of focus.

Despite limitations, the present theory and research is timely and important. In 2017, the FBI received 135,755 reports of rape (Federal Bureau of Investigations, n.d.). For sexual violence to remain at such pervasive and unacknowledged levels, cultural ideologies that legitimate and justify sexual violence are likely to be imbedded in normative notions of masculinity and heterosexual intimacy (Dworkin, 1987), family (Millett, 1969), identity (Butler, 1989), society (Firestone, 1974), and the state (MacKinnon, 1989). This work documents the relation between threats to masculinity and the explicit intent to dominate, use, and blame women for sexual violence, which is critical to understanding the ongoing pervasiveness of sexual violence.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-psp-10.1177_01461672231179431 for Masculinity Threats Sequentially Arouse Public Discomfort, Anger, and Positive Attitudes Toward Sexual Violence by Theresa K. Vescio, Nathaniel E. C. Schermerhorn, Kathrine A. Lewis, Katsumi Yamaguchi-Pedroza and Abigail J. Loviscky in Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This material is based upon work supported by a National Science Foundation Grant awarded to the first author (BCS#1152147). This sponsor’s role was limited to funding the research.

ORCID iD: Nathaniel E. C. Schermerhorn  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7531-2194

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7531-2194

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material is available online with this article.

References

- Bartky S. L. (1990). Femininity and domination: Studies in the phenomenology of oppression. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Begany J. J., Milburn M. A. (2002). Psychological predictors of sexual harassment: Authoritarianism, hostile sexism, and rape myths. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 3(2), 119–126. 10.1037/1524-9220.3.2.119 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bosson J. K., Prewitt-Freilino J. L., Taylor J. N. (2005). Role rigidity: A problem of identity misclassification? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89(4), 552–565. https://10.1037/0022-3514.89.4.552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosson J. K., Vandello J. A., Burnaford R. M., Weaver J. R., Arzu Wasti S. (2009). Precarious manhood and displays of physical aggression. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 35(5), 623–634. 10.1177/0146167208331161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brannon R. (1976). The male sex role: Our culture’s blueprint for manhood, and what it’s done for us lately. In David D., Brannon R. (Eds.), The forty-nine percent majority: The male sex role (pp. 1–49). Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Brown T. L., Smith N. G. (2021). Experimentally testing the impact of status threat on heterosexual men’s use of anti-gay slurs: A precarious manhood and coalitional value perspective. Current Psychology. 10.1007/s12144-021-02489-7 [DOI]

- Brownmiller S. (1975). Against our will: Men, women, and rape. Secker and Warburg. [Google Scholar]

- Butler J. (1989). Gender trouble: Feminism and the subversion of identity. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cikara M., Bruneau E. G., Saxe R. R. (2011). Us and them: Intergroup failures of empathy. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20(3), 149–153. 10.1177/0963721411408713 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Connell R. (1995). Masculinities. University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Courtenay W. H. (2000). Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men’s well-being: A theory of gender and health. Social Science & Medicine, 50(10), 1385–1401. 10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00390-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl J., Vescio T., Weaver K. (2015). How threats to masculinity sequentially cause public discomfort, anger, and ideological dominance over women. Social Psychology, 46(4), 242–254. 10.1027/1864-9335/a000248 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Beauvoir S. (1949/2009). The second sex (Borde C., Malovany-Chevallier S., Trans.). Vintage Books. (Original work published 1949) [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin A. (1987). Intercourse. Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Bureau of Investigations. (n.d.). 2017 crime in the United States. https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2017/crime-in-the-u.s.-2017/topic-pages/rape

- Firestone S. (1974). The dialectic of sex: The case for a feminist revolution. Jonathan Cape. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald L. F., Gelfand M. J., Drasgow F. (1995). Measuring sexual harassment: Theoretical and psychometric advances. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 17(4), 425–445. 10.1207/s15324834basp1704_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald L. F., Shullman S. L., Bailey N., Richards M., Swecker J., Gold Y., . . . Weitzman L. (1988). The incidence and dimensions of sexual harassment in academia and the workplace. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 32(2), 152–175. 10.1016/0001-8791(88)90012-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fransher A. K., Zedaker S. B. (2020). The relationship between rape myth acceptance and sexual behaviors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(1–2), NP903–NP924. 10.1177/0886260520916831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson B. L., Roberts T. A. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21(2), 173–206. 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gervais S. J., Davidson M. M., Styck K., Canivez G., DiLillo D. (2018). The development and psychometric properties of the Interpersonal Sexual Objectification Scale—Perpetration Version. Psychology of Violence, 8(5), 546–559. [Google Scholar]

- Gervais S. J., DiLillo D., McChargue D. (2014). Understanding the link between men’s alcohol use and sexual violence perpetration: The mediating role of sexual objectification. Psychology of Violence, 4(2), 156–169. 10.1037/a0033840 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gervais S. J., Eagan S. (2017). The common thread connecting myriad forms of sexual violence against women. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 87, 226–232. 10.1037/ort0000257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gervais S. J., Vescio T. K., Allen J. (2011). When what you see is what you get: The consequences of the objectifying gaze for women and men. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 35(1), 5–17. 10.1177/0361684310386121 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gervais S. J., Vescio T. K., Föster J., Maass A., Suitner C. (2012). Seeing women as objects: The sexual body part recognition bias. European Journal of Social Psychology, 42, 743–753. 10.1002/ejsp.1890 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison B. F., Michelson M. R. (2019). Gender, masculinity threat, and support for transgender rights: An experimental study. Sex Roles, 80(1), 63–75. 10.1007/s11199-018-0916-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A. F. (2015). An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 50(1), 1–22. 10.1080/00273171.2014.962683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Heflick N. A., Goldenberg J. L. (2014). Seeing eye to body: The literal objectification of women. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23(3), 225–229. 10.1177/0963721414531599 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- hooks b. (2004). We real cool: Black men and masculinity. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hust S. J. T., Rodgers K. B., Ebreo S., Stefani W. (2019). Rape myth acceptance, efficacy, and heterosexual scripts in men’s magazines: Factors associated with intentions to sexually coerce or intervene. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34(8), 1703–1733. 10.1177/0886260516653752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakupk M., Tull M. T., Roemer L. (2005). Masculinity, shame, and fear of emotions as predictors of men’s expressions of anger and hostility. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 6(4), 275–284. 10.1037/1524-9220.6.4.275 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny D. A., Kashy D. A., Bolger N. (1998). Data analysis in social psychology. In Gilbert D., Fiske S., Lindzey G. (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (4th ed., Vol. 1. pp. 233–265). McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel M. S. (2008). Guyland: The perilous world where boys become men. Harper. [Google Scholar]

- Konopka K., Rajchert J., Dominiak-Kochanek M., Roszak J. (2021). The role of masculinity threat in homonegativity and transphobia. Journal of Homosexuality, 68(5), 802–829. 10.1080/00918369.2019.1661728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosakowska-Berezecka N., Besta T., Adamska K., Jaśkiewicz M., Jurek P., Vandello J. A. (2016). If my masculinity is threatened I won’t support gender equality? The role of agentic self-stereotyping in restoration of manhood and perception of gender relations. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 17(3), 274–284. 10.1037/men0000016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- LeBreton J. M., Wu J., Bing M. N. (2009). The truth (s) on testing for mediation in the social and organizational sciences. In Lance C. E., Vandenberg R. J. (Eds.), Statistical and methodological myths and urban legends: Doctrine, verity, and fable in the organizational and social sciences (pp. 109–144). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Sun Y., Ho M. Y., Shaver P. R., Wang Z. (2016). State narcissism and aggression: The mediating roles of anger and hostile attributional bias. Aggressive Behavior, 42, 333–345. 10.1002/ab.21629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locke B. D., Mahalik J. R. (2005). Examining masculinity norms, problem drinking, and athletic involvement as predictors of sexual aggression in college men. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(3), 279–283. https://doi.org.ezaccess.libraries.psu.edu/10.1037/0022-0167.52.3.279 [Google Scholar]

- Loughnan S., Pina A., Vasquez E. A., Puvia E. (2013). Sexual objectification increases rape victim blame and decreases perceived suffering. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 37(4), 455–461. 10.1177/0361684313485718 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maass A., Cadinu M., Guarnieri G., Grasselli A. (2003). Sexual harassment under social identity threat: The computer harassment paradigm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(5), 853–870. 10.1037/0022-3514.85.5.853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon C. A. (1989). Toward a feminist theory of the state. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Millett K. (1969). Sexual politics. Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Murnen S. K., Wright C., Kaluzny G. (2002). If “boys will be boys,” Then girls will be victims? A meta-analytic review of the research that relates masculine ideology to sexual aggression. Sex Roles, 46(11/12), 359–375. 10.1023/A:1020488928736 [DOI]

- Parrott D. J., Zeichner A. (2008). Determinants of anger and physical aggression based on sexual orientation: An experimental examination of hypermasculinity and exposure to male gender role violations. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 37, 891–901. 10.1007/s10508-007-9194-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe C. J. (2007). Dude, you’re a fag: Sexuality and masculinity in high school. University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Payne D. L., Lonsway K. A., Fitzgerald L. F. (1999). Rape myth acceptance: Exploration of its structure and its measurement using the Illinois rape myth acceptance scale. Journal of Research in Personality, 33(1), 27–68. 10.1006/jrpe.1998.2238 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher K. J., Hayes A. F. (2008). Contemporary approaches to assessing mediation in communication research. In Hayes A. F., Slater M. D., Snyder L. B. (Eds.), The safe sourcebook of advanced data analysis methods for communication research (pp. 13–54). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Prentice D. A., Carranza E. (2002). What women and men should be, shouldn't be, are allowed to be, and don’t have to be: The contents of prescriptive gender stereotypes. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 26(4), 269–281. https://doi.org.ezaccess.libraries.psu.edu/10.1111/1471-6402.t01-1-00066 [Google Scholar]

- Pryor J. B. (1987). Sexual harassment proclivities in men. Sex Roles, 17(5), 269–290. 10.1007/BF00288453 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rape, Abuse, and Incest National Network. (2022). The criminal justice system: Statistics. https://www.rainn.org/statistics/criminal-justice-system

- Riemer A. R., Sáez G., Brock R. L., Gervais S. J. (2022). The development and psychometric evaluation of the Objectification Perpetration Scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 10.1037/cou0000607 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rudman L. A., Fairchild K. (2004). Reactions to counterstereotypic behavior: The role of backlash in cultural stereotype maintenance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(2), 157–176. https://doi.org.ezaccess.libraries.psu.edu/10.1037/0022-3514.87.2.157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudman L. A., Mescher K. (2012). Of animals and objects: Men’s implicit dehumanization of women and likelihood of sexual aggression. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38(6), 734–746. 10.1177/0146167212436401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudman L. A., Moss-Racusin C. A., Phalen J. E., Nauts S. (2012). Status incongruity and backlash effects: Defending the gender hierarchy motivates prejudice against female leaders. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48, 165–179. 10.1016/j.jesp.2011.10.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Russell T. D., King A. R. (2020). Distrustful, conventional, entitled, and dysregulated: PID-5 personality facets predict hostile masculinity and sexual violence in community men. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 35(3–4), 707–730. 10.1177/0886260517689887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez D. T., Fetterolf J. C., Rudman L. A. (2012). Eroticizing inequality in the United States: The consequences and determinants of traditional gender role adherence in intimate relationships. Journal of Sex Research, 49(2–3), 168–183. 10.1080/00224499.2011.653699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schermerhorn N. E. C., Vescio T. K. (2022). Perceptions of a sexual advance from gay men leads to negative affect and compensatory acts of masculinity. European Journal of Social Psychology, 52(2), 260–279. 10.1002/ejsp.2775 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seabrook R. C., Ward L. M., Giaccardi S. (2018). Why is fraternity membership associated with sexual assault? Exploring the roles of conformity to masculine norms, pressure to uphold masculinity, and objectification of women. Psychology of Men & Masculinities, 19(1), 3–13. https://doi.org.ezaccess.libraries.psu.edu/10.1037/men0000076 [Google Scholar]

- Shrout P. E., Bolger N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7(4), 422–445. 10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanaland A., Gaither S. (2021). “Be a man”: The role of social pressure in eliciting men’s aggressive cognition. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 47, 1596–1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanaland A., Gaither S., Gassman-Pines A. (2023). When is masculinity “fragile”? An expectancy-discrepancy-threat model of masculine identity. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 10.1177/10888683221141176 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Thompson E. H., Pleck J. H. (1986). The structure of male role norms. American Behavioral Scientist, 29(5), 531–543. 10.1177/000276486029005003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Valved T., Kosakowska-Berezecka N., Besta T., Martiny S. E. (2021). Gender belief systems through the lens of culture: Differences in precarious manhood beliefs and reactions to masculinity threat in Poland and Norway. Psychology of Men & Masculinities, 22(2), 265–276. [Google Scholar]

- Vandello J. A., Bosson J. K., Cohen D., Burnaford R. M., Weaver J. R. (2008). Precarious manhood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(6), 1325–1339. 10.1037/a0012453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vescio T. K., Kosakowska-Berezecka N. (2020). The not so subtle effects of everyday sexism. In Halpern D., Cheung F. M. (Eds.), The Cambridge international handbook on psychology of women (pp. 205–220). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vescio T. K., Schermerhorn N. E. C. (2021). Hegemonic masculinity predicts 2016 and 2020 voting and candidate evaluations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 118(2), Article e2020589118. 10.1073/pnas.2020589118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vescio T. K., Schermerhorn N. E. C., Gallegos J. M., Laubach M. L. (2021). The effects of threats to masculinity on perspective taking, empathy, guilt, and shame. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 97, Article 104195. 10.1016/j.jesp.2021.104195 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vescio T. K., Schlenker K. A., Lenes J. G. (2010). Power and sexism. In Guinote A., Vescio T. (Eds.), The social psychology of power (pp. 363–380). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver K. S., Vescio T. K. (2015). The justification of social inequality in response to masculinity threats. Sex Roles, 72(11), 521–535. 10.1007/s11199-015-0484-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Widman L., McNulty J. K. (2010). Sexual narcissism and the perpetration of sexual aggression. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39(4), 926–939. 10.1007/s10508-008-9461-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiener R. L., Gervais S. J., Allen J., Marquez A. (2013). Eye of the beholder: Effects of perspective and sexual objectification on harassment judgments. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 19(2), 206–221. 10.1037/a0028497 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Willer R., Rogalin C. L., Conlon B., Wojnowicz M. T. (2013). Overdoing gender: A test of the masculine overcompensation thesis. American Journal of Sociology, 118(4), 980–1022. 10.1086/668417 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X., Lynch J. G., Jr., Chen Q. (2010). Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(2), 197–206. 10.1086/651257 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-psp-10.1177_01461672231179431 for Masculinity Threats Sequentially Arouse Public Discomfort, Anger, and Positive Attitudes Toward Sexual Violence by Theresa K. Vescio, Nathaniel E. C. Schermerhorn, Kathrine A. Lewis, Katsumi Yamaguchi-Pedroza and Abigail J. Loviscky in Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin