Abstract

Background and aim

Insulin resistance and other metabolic risk factors are associated with increased cardiovascular diseases in animals fed with high fat diets (HFD). L-arginine is a semi-essential amino acid produced both endogenously and taken in the diet as supplements. It has been documented to possess antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties and has been considered a plausible candidate for the management of metabolic disorders. Therefore, this study is aimed to determine the effects of L-arginine on lipid dysregulation and insulin resistance in high fat-fed male Wistar rats.

Methods and results

Twenty-four (24) male Wistar rats randomly selected into 4 groups, mean weight 110 ± 5 and, (n = 6) were fed rat chow + distilled water (vehicle); CTR, rat chow + L-arginine (150 mg/kg), HFD + vehicle, HFD + L-Arginine (150 mg/kg) for 6 weeks. The animals were anesthetized with 50 mg/kg pentobarbital sodium intraperitoneally, blood sample was taken via cardiac puncture and thereafter collected into a heparinized tube. Data were expressed as means ± SEM. HFD increased body weight gain, serum Insulin, Homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), area under the curve (AUC), leptin, Lipoprotein(a) or Lp(a), triglyceride-glucose index (TYG), triglycerides (TG), free fatty acids (FFAs), total cholesterol (TC), low density lipoprotein (LDL-C), TC/HDL-C, Log TG/HDL-C, TC-HDL-C)/HDL-C but decreased phospoinositide-3-kinase (PIK3) when compared with control. L-arginine, resulted in significant reduction in weight gain, fasting blood sugar (FBS), insulin, AUC, HOMA-IR, leptin, while increasing PIK3, Lp(a), TG, TC and FFA when compared with HFD.

Conclusion

The amelioration of lipid and glucose accumulation by L-arginine supplementation in high fat diet-fed male Wistar rats is accompanied by reduced leptin levels and PIK3 augmentation.

Keywords: Atherogenic markers, Insulin resistance, L-Arginine, Leptin, Phosphoinositide 3-kinase

Introduction

There is evidence from several studies that a high-fat diet leads to obesity and a dysregulated lipid profile with increased LDL-c and reduced HDL-c, increased circulating free fatty acids, and atherosclerotic activities [1, 2]. A study, however, showed that saturated fatty acids are the culprit in the genesis of dyslipidemia caused by a high-fat diet [3]. The mechanisms involved in HFD-induced obesity and dyslipidemia are complex. In order to simplify the process, it is good to consider the glucoregulatory and lipo-regulatory mechanisms that are directly or indirectly affected by HFD. Among these are the insulin and leptin pathways.

L-arginine is an amino acid known to possess antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties that is beginning to find relevance in the management of metabolic disorders. Apart from its endogenous secretion, many food sources such as fish, red meat, dairy, eggs, pumpkin seeds, soybeans, lentils, and chickpeas are rich in L-arginine [4, 5]. In a study carried out for 12 weeks on patients with metabolic syndrome, supplementation with 5 g/day of L-arginine reduced fasting blood glucose, circulating triglycerides, and the total cholesterol to high density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio (TC/HDL-c) [6]. The benefits of L-arginine on cardiac, hepatic, pancreatic, and inflammatory obesity-related alterations in high fat diet-fed rats have been studied by Alam et al. [7] and it was found that L-arginine supplementation suppressed derangement in the left ventricle, improved the functions and structure of the liver, glucose tolerance, and blood pressure. However, the mechanisms by which L-arginine regulates glucose and lipid balance are not clear [8]. Nevertheless, lipid homeostasis is found to be significantly affected by diets and endogenous factors.

The hormone leptin is predominantly produced from adipose tissues, and its primary function is to regulate adiposity. Leptin regulates energy balance by inhibiting hunger in the hypothalamus, which in turn reduces food intake (including fat), leading to a reduction in adiposity [9]. Whereas, insulin, which is arguably the most important anabolic hormone in the body [10], regulates fats, carbohydrates, and protein metabolism. It controls the deposition of glucose into the adipocytes, myocytes, and hepatocytes from the blood [11]. A study showed that chronic HFD caused hyperleptinemia, which was associated with visceral fat accumulation [12]. Another study established that hyperleptinemia occurs at the third stage of the impact of HFD due to leptin resistance [13]. In leptin resistance, sensitivity to the hormone has drastically reduced, leading to hyperphagia despite high levels of the hormone in circulation. Several studies have linked chronic ingestion of HFD with its deleterious consequences to insulin resistance [14, 15]. Insulin resistance leads to hyperinsulinemia and associated lipid dysregulation as a result of adipose and hepatic insulin resistance, which are characterized by increased lipolysis and de novo lipogenesis respectively [16]. More precisely, among the diverse mechanisms of insulin resistance, downregulation of phosphoinositide-3-kinase (PIK3) is very important.

Although diseases engendered by HFD are preventable, the prevalence of obesity-related diseases worldwide is alarming. It is therefore expedient that management or treatment measures with fewer adverse effects be developed. Hence, the aim of the present study was to investigate the effect of L-arginine supplementation on lipid dysregulation and insulin resistance in HFD-fed male Wistar rats.

Materials and methods

Study design, and grouping

Animals

Twenty-four (24) male Wistar rats, aged 4–5 weeks and weighing between 100 and 115 g were housed in separate cages and kept at constant environmental conditions of temperature (22–26 °C), relative humidity (50–60%) and 12-h dark/light cycle. The rats were fed on a constant ration, and fresh, clean drinking water was supplied. All the rats were also acclimatized for a period of one week prior to the commencement of the study. The study was carried out in accordance with the world accepted best practices as written in the European Commission guidelines (Directives of 2010/63/EU as amended by Regulation (EU) 2019/1010) as well as the Animal Research Reporting of In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines and was approved by the Ethical Review Committee, University of Ilorin, Ilorin, Nigeria (UERC/ASN/2018/357).

Chemicals

All the chemicals were of analytical grade. The chemicals used in the study include L-arginine, which was purchased from Bridge Biotech Laboratory, Ilorin, Kwara State. The L-arginine was dissolved in distilled water. It was prepared freshly and administered orally at a dose of 150 mg/kg body weight [17] for a period of 6 weeks (42 days).

High fat diet

A special high fat feed was formulated using the composition provided by Abdul Kadir et al. [18]. The high fat diet contains 414.0 kcal/100 g with 43% as carbohydrate, 17% as protein, and 40% as fat. The diet consists of 17,000 g of powdered rat feed, 1500 g of maize oil, 1500 g of ghee, and 5000 g of milk powder, giving a total of 25,000 g (25 kg) of high fat feed. The composition table is shown in (Table 1).

Table 1.

Composition of high fat diet and normal rat chow diet

| High fat diet (%/100 g) | Normal chow (%/100 g) | % of total (25 kg) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbohydrate | 43 | 48.8 | |

| Protein | 17 | 21 | |

| Fat | 40 | 3 | |

| Calcium | 0.8 | ||

| Phosphorus | 0.4 | ||

| Fiber | 5 | ||

| Ash | 8 | ||

| Powdered rat chow | 17,000 | ||

| Maize oil | 1500 | ||

| Ghee | 1500 | ||

| Milk powder | 5000 | ||

| Powdered rat chow | 17,000 |

Animal grouping

After acclimatization to the laboratory conditions, the animals were randomly divided into four groups of six rats, placed in individual cages, and classified as follows; Control (CTR), rats received normal rat chow and 0.5 ml of distilled water daily, high fat diet-fed (HFD), rats received high fat feed only, high-fat diet and arginine (HFD + ARG), rats received a high fat diet and 150 mg/kg arginine orally, and arginine only (ARG), rats received a high fat diet and 150 mg/kg arginine orally, all for 6 weeks [18].

Collection of blood sample

After 6 weeks of treatment, animals were anesthetized with 0.8 mg Pentobarbital sodium intraperitoneally (50 mg/kg ip) and blood was collected by cardiac puncture. Blood was collected by cardiac puncture into plain tube, left for 30 min to clot in the tube and thereafter was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 min at room temperature. Serum was stored frozen until needed for biochemical assay.

Fasting blood sugar test and oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT)

After 8 h of an overnight fast, the tails of the rats were pricked with a lancet blade for the FBS. Thereafter, 200 g/l of glucose in water, after proper dissolution, was given by oral gavage at a dose of 2 g/kg of body weight, and blood glucose was obtained at the tail tip at 30, 60, 90 and 120 min for glucose concentration using a handheld On-Call glucometer. This test was carried out on all rats, and the results were recorded.

Biochemical assay

Serum insulin assay

Serum insulin concentrations were measured with an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (cat number:IS130D) procured from Ray Biotechnology, Inc. (Georgia, USA). The sensitivity of the assay was 0.5 mU/L, and the inter-assay coefficients of variation were < 7.5 and 9.3%, respectively.

Homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR)

This parameter was derived by using the formula.

Homeostasis model assessment of beta cell (homa-beta)

This parameter was derived by using the formula.

Triglyceride-glucose (TyG) index

This parameter was derived by using the formula.

Cardiac risk ratio

Atherogenic coefficient

Atherogenic index of plasma

LDL-c

Serum leptin assay

Serum leptin concentrations were measured by the sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) method on a DSX ELISA automated analyzer. Protocols were run according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The analytical sensitivity for the leptin kit was 0.7 ng/ml, specificity for human leptin was 100% and the assay dynamic range was 0.7–100 ng/ml.

Phosphotylinosital 3 kinase assay

Phosphotylinosital 3 Kinase (also known as PI3K), assay was done using the Sandwich-ELISA kit purchased from Elabscience® with Cat.NoE0438Ra.

Statistical analysis

The results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation using graph pad prism 8. The data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA. Post-hoc Tukey test was used to determine the significance of mean values among the groups. The P-value (P < 0.05) was used to determine significant differences.

Results

Arginine supplementation normalized absolute body weight and attenuated percentage body weight change in rats fed with HFD

Absolute body weight was increased after the experiment compared with control in HFD-fed animals. Nevertheless, absolute body weight did not change compared with control group in animals fed arginine supplementation with or without HFD. However, HFD significantly increased the percentage body weight change compared with control (92.1 ± 1.1% vs 25.4 ± 0.34%) which was also significantly attenuated by arginine supplementation compared with HFD (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of body weight percentage (%) change between CTR, ARG, ARG + HFD

| Body weight (g) | CTR | ARG | ARG + HFD | HFD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | 115.5 ± 2.3 | 105.1 ± 2.5 | 108.7 ± 2.1 | 114.5 ± 2.4 |

| Final | 144.8 ± 3.1 | 161.8 ± 4.1 | 157.2 ± 4.1 | 220 ± 5.1 |

| % Change | 25.4 ± 0.34 | 49.6 ± 0.6* | 48.9 ± 0.95# | 92.1 ± 1.1* |

*P < 0.05 versus control; #P < 0.05 versus HFD

Arginine supplementation improved insulin sensitivity in HFD-fed male Wistar rats

Fasting blood glucose, insulin and HOMA-IR were significantly raised in animals fed HFD, P < 0.05 (Fig. 1a, b, c).

Fig. 1.

Arginine (ARG) did not affect fasting blood glucose (A), but reduced insulin (B), HOMA-IR (C) and increased HOMA-β (D) in high fat diet-fed (HFD) animals. CTR: control. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 versus control; #P < 0.05 versus HFD

In addition, HFD significantly reduced HOMA-B, P < 0.05 (Fig. 1d). Arginine supplementation in HFD-fed animals caused reduction in fasting blood glucose levels compared with HFD without supplementation. Conversely, it significantly reduced insulin, HOMA-IR, P < 0.05 in HFD-fed animals to levels comparable to the control, while HOMA-B was augmented by arginine supplementation in HFD-fed animals (Fig. 1).

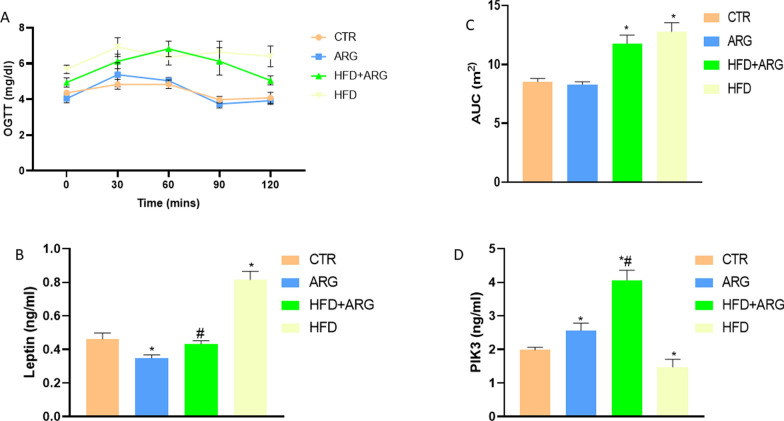

Arginine supplementation improved glucoregulation, attenuated leptin levels and augmented PIK3 in HFD-fed male Wistar rats

High-fat diet exposure led to a significant elevation of OGTT and AUC of OGTT, P < 0.05 (Fig. 2a, c).

Fig. 2.

Arginine (ARG) did not affect Area under the curve (AUC) of oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) (A and C), but reduced leptin (B), and increased phosphoinositol-3-kinase (PIK3) (D) in high fat diet-fed (HFD) animals. CTR: control. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 versus control; #P < 0.05 versus HFD

There was also an observed increase in leptin and decrease in PIK3 levels in the HFD group compared to the control group. The arginine-treated HFD-fed group showed improvement in AUC and OGTT compared with HFD-exposure without arginine. However, leptin level was significantly reduced and PIK3, P < 0.05 elevated in the HFD + arginine group compared with the HFD group (Fig. 2b, d).

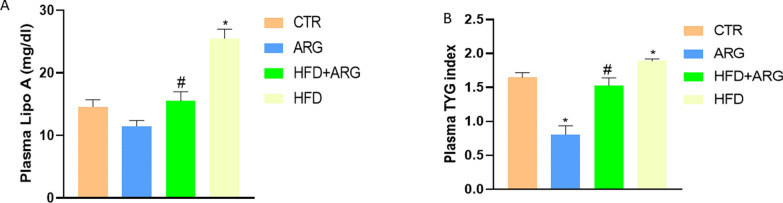

Arginine normalized lipid profile in male Wistar rats fed with HFD

There was an increase in Lp(a) level and triglyceride-glucose index (TyG) in HFD-fed animals compared with control and animals exposed to only arginine (Fig. 3a, b).

Fig. 3.

Arginine (ARG) reduced lipoprotein A (Lp(a)) (A) and triglyceride-glucose index (TyG) (B) in high fat diet-fed (HFD) animals. CTR: control. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 versus control; #P < 0.05 versus HFD

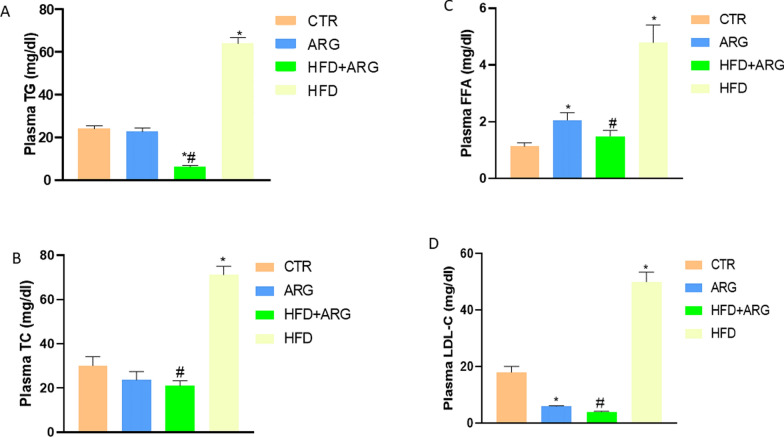

The arginine-treated group that was not exposed to HFD had a normal Lp(a) level but a reduced TyG index. However, arginine treatment in animals exposed to HFD significantly reduced both Lp(a) level and the TyG index P < 0.05. High-fat diet significantly increased plasma TG, FFA, TC and LDL-C, P < 0.05 compared with control and animals exposed to only arginine. Arginine treatment reduced TG, FFA, TC and LDL-C in the plasma of HFD-fed male Wistar rats (Fig. 4a, b, c, d).

Fig. 4.

Arginine (ARG) reduced plasma triglyceride (TG) (A), total cholesterol (TC) (B), free fatty acid (FFA) (C) and low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-c) (D) in high fat diet-fed (HFD) animals. CTR: control. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 versus control; #P < 0.05 versus HFD

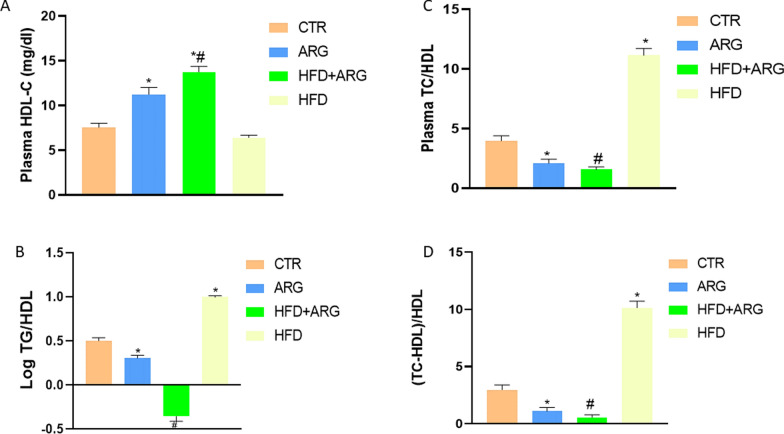

In addition, HDL-C was not affected by HFD compared with control, but it was significantly increased by arginine with or without HFD, P < 0.05 (Fig. 5a). However, plasma TC/HDL, the logarithm of TG/HDL and TC/HDL ratios were elevated in HFD-fed rats. Arginine treatment with or without HFD exposure reduced the ratios compared with both control and HFD without arginine treatment (Fig. 5b, c, d).

Fig. 5.

Arginine (ARG) increased high density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-C) (A), and reduced plasma total cholesterol/HDL ratio (B), log of triglyceride (TG)/HDL ratio (C) and atherogenic coefficient (TC-HDL)/HDL (D) in high fat diet-fed (HFD) animals. CTR: control. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 versus control; #P < 0.05 versus HFD

Discussion

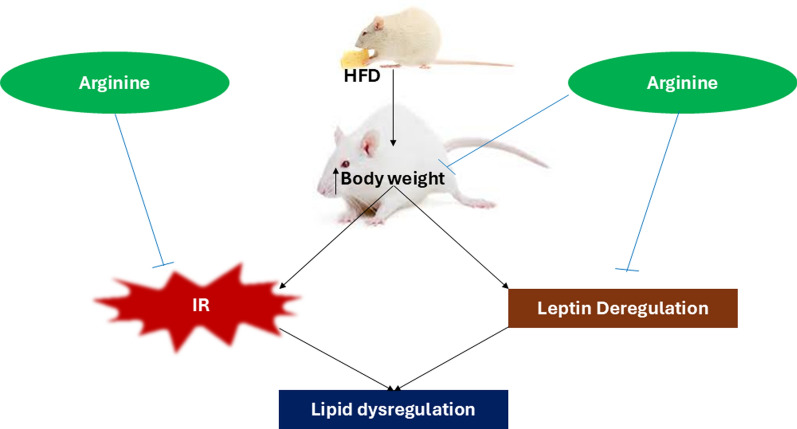

The findings of the present study demonstrated that high-fat diet increased body weight gain, insulin resistance, circulating leptin, and lipids to a profound degree. In addition, the elevated circulating lipid ratios (TG/HDL and TC/HDL) in HFD-fed animals are indicative of glucose dysregulation, lipid dysregulation, and athero-thrombotic conditions. Nevertheless, the elevated circulating leptin indicates leptin resistance and is associated with increased body weight gain observed in HFD-fed animals in this study. However, L-arginine administration to HFD-fed animals reduced body weight gain, improved insulin sensitivity, and corrected dysregulation of leptin and lipids (Fig. 6). This study also demonstrated that the effects of L-arginine are accompanied by enhancement of PIK3, a molecule located downstream of the insulin receptor.

Fig. 6.

Graphical abstract showing the effect of arginine on high fat diet (HFD) induced body weight gain, insulin resistance (IR), leptin deregulation

HFD-fed animals in this study had elevated body weight changes, which can be attributed to the probable fat accumulation due to chronic HFD exposure. Fat accumulation is the basis for the development of obesity and obesity-related diseases. Increase in body weight is a risk factor for metabolic syndrome and atherosclerotic diseases, and the high prevalence of metabolic diseases can be linked to increased consumption of western diets and processed foods [19]. Daily consumption of western diets and an increasingly sedentary lifestyle have caused a large increase in body weight among young adults in recent years, predisposing them to metabolic disease and atherosclerosis [20]. High fat diet exposure enhances lipotoxiticy which causes metabolic derangements as a result of free fatty acid accumulation leading to insulin resistance [21]. High fat diet in this study increases Lp(a) which is an important lipoprotein contributing to atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and this was attenuated with arginine supplementation (Fig. 3a). The association between Lp(a) and major cardiovascular disease (CVD) outcomes is highly predictive and a raised Lp(a) is a risk factor even at very low low-density lipoprotein (LDL-C) concentration.

From this study, HFD engendered insulin resistance (Fig. 1), elevated circulating leptin (Fig. 2B) and markers of atherosclerotic disease (Fig. 3, 4, 5). These findings are similar to the results of other studies in which rats fed HFD [22], a high fructose diet [23] and induced with type 2 diabetes [24] showed great metabolic impairments. The mechanisms of these three common models of metabolic syndrome are diverse but related. Whereas high fructose exposure mainly uses uric acid and related mechanisms to engender metabolic derangements, the induction of type 2 diabetes uses insulin deficiency to set up glucose dysregulation, which eventually leads to overt metabolic disease. However, HFD compromises insulin sensitivity via lipotoxicity and among the molecules that initiate insulin action, PI3K has been greatly implicated. The functions of PI3K include, but not limited to activation of protein kinase B (Akt) which initiates cell growth, cell trafficking, among others. The translocation of GLUT4 is among the actions that are engendered by PI3K which is usually the determinant step in insulin sensitivity. In this study, HFD significantly reduced PI3K levels compared to the control, meaning that the HFD-engendered derangement of insulin sensitivity is dependent on PI3K regulation. Once insulin sensitivity is compromised by HFD, the stage is set for other pathologies like leptin resistance, obesity, and atherosclerosis, which are precursors of metabolic disease complications.

Several pharmacological interventions used for management of the multifactorial metabolic diseases are usually associated with side effects and/or limitations. However, many research efforts are directed towards characterizing safe and effective treatments. One of the various considerations is dietary molecules. In this study, L-arginine, an amino acid and precursor for nitric oxide synthesis, was strategically studied for its ameliorative effect on lipid dysregulation in HFD-fed rats. It was found that L-arginine reduced weight gain and resolved the insulin resistance and leptin dysregulation associated with HFD. Nevertheless, these observations were associated with improved lipid regulation and the augmentation of PIK3. PIK3 pathways mediate the effects of insulin on vascular functions via increased nitric oxide production [25]. Enhanced vascular relaxation can increase blood flow and insulin action. Since L-arginine is a precursor of nitric oxide, increased bioavailability causes a compensatory elevated PIK3 expression through a neovascularization effect [26]. This elevated PIK3 increases the cells’ insulin sensitivity by up-regulating insulin receptor substrate activation of PIK3.

The mechanisms of insulin resistance promote the activation of immune responses via the ERK/MAPK/NFKB pathway, especially in adipose tissues [27]. High-fat diet has been shown to induce low-grade inflammation, which produces inflammatory cytokines in adipose tissues [28]. One of the proinflammatory cytokines that interact with the immune system in adipose tissues is leptin. High-fat diet may therefore induce hyperleptinaemia via the induction of proinflammatory cytokines in the adipose tissue. An important significance of this study is the fact that chronic HFD exposure in animal models depicts rampant diet-related metabolic disease in the western world, which is spreading wildly in low-income developing countries because of the disruptive adoption of western diets. In the present study however, arginine supplementation attenuated leptin levels in high fat diet-fed male Wistar rats. This outcome can be a pointer to the anti-inflammatory role of arginine and leptin modulation through enhanced insulin sensitivity.

Conclusion

In conclusion, L-arginine ameliorates lipid and glucose dysregulations by reducing leptin level and enhancing PIK3 signaling activities in high fat-fed male Wistar rats. Consumption of food rich in L-arginine may be of tremendous value to people suffering from metabolic disorders such as obesity and cardiovascular diseases and this can form an important component of lipid lowering agents.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledged the technical support of HOPE Cardiometabolic Research Team and Mr. Adebowale of Bridge Biotech is also appreciated for the laboratory analysis.

Author contributions

A.O., O.B., B.B.A. and A.M.A. conceived and designed the research. A.O.O. and B.B.A. conducted the experiments. A.O.O. and A.M.A. contributed to the new reagents and analytical kits. A.O.O., B.B.A. and A.M.A. analyzed and interpreted the data. A.O.O., B.B.A. and A.M.A. drafted the manuscript. A.O.O., B.B.A. and A.M.A. read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Adewumi Oluwafemi Oyabambi, Email: oyabambi.ao@unilorin.edu.ng.

Olubayode Bamidele, Email: olubayode.bamidele@bowen.edu.ng.

References

- 1.Hariri N, Thibault L. High-fat diet-induced obesity in animal models. Nutr Res Rev. 2010;2010(23):270–99. 10.1017/S0954422410000168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jia YJ, Liu J, Guo YL, Xu RX, Sun J, Li JJ. Dyslipidemia in rat fed with high-fat diet is not associated with PCSK9-LDL-receptor pathway but ageing. J GeriatrCardiol. 2013;10(4):361–8. 10.3969/j.issn.1671-5411.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Montoya MT, Porres A, Serrano S, Fruchart JC, Mata P, Gerique JA, et al. Fatty acid saturation of the diet and plasma lipid concentrations, lipoprotein particle concentrations, and cholesterol efflux capacity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;75:484–91. 10.1093/ajcn/75.3.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pano MA, Kruskall LJ, Thomas DT. Nutrition for Sport, Exercise, and Health. Champaign: Human Kinetics; 2017. p. 240. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watson RR, Zibadi S. Bioactive Dietary Factors and Plant Extracts in Dermatology. Berlin: Springer; 2012. p. 75. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bahrami D, Mozaffari-Khosravi H, Zavar-Reza J. The effect of oral L-arginine supplementation on lipid profile, glycemic status, and insulin resistance in patients with metabolic syndrome: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Mediterr J Nutr Metab. 2019;12:79–90. 10.3233/MNM-180233. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alam MA, Kauter K, Withers K, Sernia C, Brown L. Chronic l-arginine treatment improves metabolic, cardiovascular and liver complications in diet-induced obesity in rats. Food Funct. 2013;4(1):83–91. 10.1039/c2fo30096f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Szlas A, Kurek JM, Krejpcio Z. The potential of L-arginine in prevention and treatment of disturbed carbohydrate and lipid metabolism—a review. Nutrients. 2022;14(5):961. 10.3390/nu14050961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Hussaniy HA, Alburghaif AH, Naji MA. Leptin hormone and its effectiveness in reproduction, metabolism, immunity, diabetes, hopes and ambitions. J Med Life. 2021;14(5):600–5. 10.25122/jml-2021-0153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Voet D, Voet JG. Biochemistry. 4th ed. New York: Wiley; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stryer L. Biochemistry. 4th ed. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company; 1995. p. 773–4. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Handjieva-Darlenska T, Boyadjieva N. The effect of high-fat diet on plasma ghrelin and leptin levels in rats. J PhysiolBiochem. 2009;65(2):157–64. 10.1007/BF03179066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin S, Thomas T, Storlien L, et al. Development of high fat diet-induced obesity and leptin resistance in C57Bl/6J mice. Int J Obes. 2000;24:639–46. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mary HB, Richard MW, Enrique T, Miwa T, Jean ML, Thomas AB, et al. High-fat diet is associated with obesity-mediated insulin resistance and β-cell dysfunction in mexican americans. J Nutr. 2013;143(4):479–85. 10.3945/jn.112.170449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.von Frankenberg AD, Marina A, Song X, Callahan HS, Kratz M, Utzschneider KM. A high-fat, high-saturated fat diet decreases insulin sensitivity without changing intra-abdominal fat in weight-stable overweight and obese adults. Eur J Nutr. 2017;56(1):431–43. 10.1007/s00394-015-1108-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Avramoglu RK, Basciano H, Adeli K. Lipid and lipoprotein dysregulation in insulin resistant states. Clin Chim Acta. 2006;368(1–2):1–19. 10.1016/j.cca.2005.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moustafa MZ, Ahmed AA, Khalid AA, Yasser RH, Mohamed MM, Kheir EE, et al. L-arginine supplementation alters maternal blood biochemical attributes and milk composition relative to neonatal traits of Najdi Ewes. Open J Anim Sci. 2019;09(03):341–54. 10.4236/ojas.2019.93028. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abdul Kadir NA, Rahmat A, Jaafar HZ. Protective effects of tamarillo (Cyphomandrabetacea) extract against high fat diet induced obesity in sprague-dawley rats. J Obes. 2015;2015:846041. 10.1155/2015/846041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rakhra V, Galappaththy SL, Bulchandani S, Cabandugama PK. Obesity and the western diet: how we got here. Mo Med. 2020;117(6):536–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Christ A, Latz E. The Western lifestyle has lasting effects on metaflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2019;19:267–8. 10.1038/s41577-019-0156-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oyabambi AO, Saliu SB, Abena E, Zainab A. Role of high-density lipoprotein in the ameliorative activity of Bryophyllumpinnatum in male Wistar rats fed a high fat diet. LASU J Med Sci. 2020;4(2):38–43. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moreno-Fernández S, Garcés-Rimón M, Vera G, Astier J, Landrier JF, Miguel M. High fat/high glucose diet induces metabolic syndrome in an experimental rat model. Nutrients. 2018;10(10):1502. 10.3390/nu10101502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oyabambi AO, Michael OS, Areola ED, Saliu SB, Olatunji LA. Sodium acetate ameliorated systemic and renal oxidative stress in high-fructose insulin-resistant pregnant Wistar rats. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2021;394(7):1425–35. 10.1007/s00210-021-02058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hussein AA, Abdel-Aziz A, Gabr M, Hemmaid KZ. Myocardial and metabolic dysfunction in type 2 diabetic rats: impact of ghrelin. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2012;90(1):99–111. 10.1139/y11-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Michell BJ, Griffiths JE, Mitchelhill KI, Rodriguez-Crespo I, Tiganis T, Bozinovski S, de Montellano PR, Kemp BE, Pearson RB. The Akt kinase signals directly to endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Curr Biol. 1999;9:845–8. 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80371-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oyabambi AO, Michael OS, Imam-Fulani AO, Babatunde SS, Oni KT, Sanni DO. Corn silk (Stigma maydis) aqueous extract attenuates high-salt induced glucose dysregulation and cardiac dyslipidemia: involvement of phosphoinositide 3-kinase activities. J Afr Ass Physiol Sci. 2021;9(1):105–12. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Makhijani P, Basso PJ, Chan YT, Chen N, Baechle J, Khan S, Furman D, Tsai S, Winer DA. Regulation of the immune system by the insulin receptor in health and disease. Front Endocrinol. 2023;14:1128622. 10.3389/fendo.2023.1128622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mattace RG, Simeoli R, Russo R, et al. Effects of sodium butyrate and its synthetic amide derivative on liver inflammation and glucose tolerance in an animal model of steatosis induced by high fat diet. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(7):e68626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.