Abstract

Objective

This study aims to assess the robustness of cardiovascular disease randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with primary continuous outcomes from a clinical perspective, utilizing the concepts of continuous fragility index (CFI), reverse continuous fragility index (RCFI) and their corresponding quotients (CFQ, RCFQ).

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted, searching PubMed for cardiovascular RCTs published between January 1, 2018, to December 31, 2022, in eight high-impact journals. Inclusion criteria were phase III or IV trials with 1:1 randomization, reporting at least one primary continuous outcome. Data analysis involved altering each outcome until achieving the reversal of significance (ɑ = 0.05) to determine the CFI or RCFI. The fragility quotients were then calculated by dividing the CFI or RCFI by the sample size, and Spearman’s correlation assessed correlation analyses.

Results

Of 3983 records were screened, and 64 RCTs (76 outcomes) were included. The fragility index was analysed with 72 outcomes. The overall median CFI was 7, with an associated median CFQ of 0.032. Nonsignificant P values exhibited greater statistical instability (median RCFI = 5, RCFQ = 0.023) than significant P values (median CFI = 14, CFQ = 0.062). Interestingly, “fragile” values were found in 36% (9/25) of CFI or 46.7% (7/15) of RCFI. Additionally, fragility index showed a significant association with several variables.

Conclusions

The findings suggest that changing only a small number of interventions (median of 7) could alter outcome significance. Reporting the fragility index alongside P values is recommended to provide a clearer understanding of statistical findings’ robustness.

Highlights

The continuous fragility index (CFI) represents the minimum patient count needed to modify significance by altering their intervention.

Among 72 primary continuous outcomes in 64 cardiovascular RCTs, the overall median CFI was 7, with a corresponding CFQ of 0.032.

CFI demonstrated moderate to strong correlations with sample size, total dropouts, and patient numbers analyzed.

Keywords: Fragility index, reverse fragility index, continuous fragility index, robustness

1. Introduction

The importance of prevention and treatment for cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) cannot be ignored, as they are the leading cause of mortality and a significant contributor to global disability [1]. In 2021, CVDs resulted in approximately 20.5 million deaths, accounting for about one-third of all global deaths [2]. There has been an increase in the number of cardiovascular randomized controlled trials (RCTs) conducted, with over one hundred thousand trials found in PubMed. RCTs are generally recognized as the premier methodology for causal inference, with the evidence derived from these trials forming the foundation of decision-making in evidence-based medicine [3,4].

Nevertheless, despite the growing number of cardiovascular trials, there are concerns about the quality of evidence available for decision-making. Baasan et al. [5] conducted a survey which revealed that nearly two-thirds of cardiovascular RCTs published in 2017 had a high or ambiguous risk of bias (RoB). Additionally, relying solely on P values to determine the effectiveness of interventions in these trials is insufficient due to limitations and low precision estimates [6].

Over the past decade, the fragility index (FI) has been increasingly used as a quantitative tool to assess the robustness of clinical trial results in various specialties, such as cardiology, oncology, orthopaedics, neurology, paediatrics and critical care medicine [7–12]. Of course, the FI is not a substitute for the P value; instead, it complements the P value by offering a more intuitive understanding of the stability of trial outcomes [13]. However, previous studies have mainly focused on dichotomous outcomes of FI, excluding most continuous variables for traditional fragility calculations. Currently, the fragility index for cardiovascular diseases also focuses solely on dichotomous outcomes [7,14–16]. Although these studies have highlighted significant differences in the fragility of various conditions within cardiovascular diseases and provided a general understanding of fragility in the context of cardiovascular diseases. Nevertheless, there is a significant knowledge gap exists when it comes to applying the concept of fragility to continuous outcomes which are frequently encountered in cardiovascular trials. Combining dichotomous and continuous outcomes may offer a more comprehensive and precise evaluation of fragility within cardiovascular diseases.

Therefore, in this study, we conducted a cross-sectional analysis to investigate the inherent fragility of continuous outcomes in cardiovascular RCTs published in eight high-impact journals. We hypothesize that the robustness range may differ between continuous and dichotomous primary outcomes. However, similar to previous analyses of dichotomous outcomes, we expect to find that many studies with promising results may have findings that are susceptible to facile reversal.

2. Methods

2.1. Study sources

To identify relevant cardiovascular RCTs, we conducted a literature search on PubMed from January 1, 2018, to December 31, 2022, using the term ‘randomized controlled trial’ [publication type]. The target journals included five high-impact general medicine journals (The Lancet, the New England Journal of Medicine [NEJM], Journal of the American Medical Association [JAMA], The BMJ, and Annals of Internal Medicine [Ann Intern Med]), and three high-impact cardiovascular medicine journals (Circulation, European Heart Journal [EHJ], and Journal of the American College of Cardiology [JACC]). Factors such as impact factor, professional publication of cardiovascular RCTs, range of circulation of studies, and influential RCT publications over several decades were taken into consideration [7]. The search was carried out by an expert clinical epidemiologist, and the complete search strategy and details are outlined in the protocol (Appendix A).

2.2. Study selection

The selection criteria for the RCTs focus on cardiovascular diseases in any clinical setting, and have at least one primary continuous outcome. Secondary outcomes were given less emphasis due to their lower statistical power and limited reliability in gauging trial efficacy [17]. The patient inclusion criteria were based on the ICD-10-CM Code range I00-I99. We specifically targeted phase III or IV RCTs with two parallel intervention groups featuring a 1:1 allocation ratio were included. Exclusions encompassed quasi-randomized trials, factorial design, cluster randomization design, crossover design, and group sequential design trials. Furthermore, we excluded RCTs in the following situations: (1) non-inferiority or equivalence hypotheses; (2) pilot trials or involved post hoc analyses, sensitivity analyses, secondary analyses, subgroup analyses, sub-studies, or interim analyses; (3) retractions, duplications and corrections. The details are outlined in the protocol (Appendix A).

2.3. Study screening

All search records were imported into EndNote and duplicates were removed. The remaining records were screened for titles and abstracts using Rayyan Software [18], accessed via https://rayyan.qcri.org/. Blinding was on until after the screening process was completed. Two screeners conducted a preliminary screening of 50 records. The full texts were obtained using Zotero Software, which is accessible at https://www.zotero.org/. Any disagreements during the screening process were resolved by a senior reviewer, and reasons for exclusion were documented. With inter-rater agreement assessed using Cohen’s kappa coefficient (κ) [19]. A kappa in the range of 0.21-0.40 be considered fair agreement, 0.41-0.60 be considered moderate agreement, 0.61-0.80 be considered substantial agreement by Landis and Koch [20]. The details are outlined in the protocol (Appendix A).

2.4. Data collection

Data extraction was conducted by two independent reviewers using a standardized form in Microsoft Excel (Office 2016, Microsoft, USA). A pilot trial of 10 studies was conducted to guide the modification of the form, and any disagreements were resolved through discussion or consultation with an additional author. The extracted characteristics included basic study characteristics, trial designs, statistical analyses, and trial results. The details are outlined in the protocol (Appendix A).

2.5. Calculation of statistical fragility

Caldwell et al. [17] introduced an iterative substitution algorithm for calculating the continuous fragility index (CFI). This method avoids the necessity for raw data collection by creating representative synthetic datasets using mean, standard deviation (SD), and sample size. The CFI simulation construct is modelled to increase linearly with sample size, increase logarithmically with mean difference, and decrease exponentially with SD. The CFI algorithm begins by taking the summary statistics (sample size, mean, and SD) to produce two simulated datasets for every continuous outcome, then conducts a Welch’s t-test to compare the means of two datasets. If the p < 0.05, the algorithm identifies the dataset with the higher mean and move the data point closest to (but still greater than) the mean of that set to the other set. The Welch’s t-test is then repeated, until between the two updated datasets yields a nonsignificant P-value, the number of times moving the data points is the fragility index CFI for that outcome measure. In other words, a datapoint is chosen and moved from the higher-mean dataset to another dataset such that the means of the two sets slightly converge, until the P-value of the Welch’s t-test crosses a predefined alpha threshold (α = 0.05).

The CFI is reported as the number of iterations required to reach a nonsignificant P value. For stability, all continuous analyses in the current study were performed with n = 50 simulations of representative data, and then calculate the median of these 50 CFI values to determine the final median CFI.

Building upon the approach proposed by Caldwell et al. [17] and following the fundamental principles of fragility delineated by Feinstein et al. [21], we extended the CFI to initially nonsignificant outcomes (p > 0.05), known as the reverse continuous fragility index (RCFI). For these outcomes, the patient was selected such that shifting them would make the means of the two arms slightly diverge.

The CFI or RCFI is an absolute value used to evaluate fragility, with the sample size potentially affecting the assessment of fragility. Thus, we calculated the continuous fragility quotient (CFQ) or reverse continuous fragility quotient (RCFQ) for each outcome as a relative measure by dividing the CFI or RCFI by its respective sample sizes.

2.6. Computing estimates of effect

Continuous variables were generally presented as the means with standard deviations (SDs). In situations where the SD was missing or needed to estimate the mean and SD of corresponding changes from baseline, approximations were made using methods outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [22]. Hozo and colleagues [23] suggested that when only the median and interquartile range (IQR) were reported, the median might be a reasonable substitute for the mean. When continuous variables were presented graphically, the semi-automated software WebPlotDigitizer (Version 4.6) [24] was used to extract data for approximate estimation. If a study did not provide adequate data for computing the mean or standard deviation, it was omitted from the fragility index calculation and only included in the descriptive analysis.

2.7. Outcomes of interest

The primary aim of this study was to describe the median values of CFI and CFQ, along with their IQRs, for all continuous outcomes based on study characteristics. Additionally, the differences between groups were compared at a significance level of 0.05. We also investigated the correlation between CFI, RCFI, CFQ or RCFQ and various factors, including sample sizes (the total sample sizes of two groups at randomization), numbers of patient all dropouts, numbers of patients dropouts due to withdraw consent, numbers of patients lost to follow-up, numbers of patients analysed (the total sample size in the statistical analysis of the two groups), follow-up duration (months), and the journal impact factor (obtained from Clarivate Analytics in early July 2023).

Furthermore, we examined other outcomes, including: (1) determining the number of studies defined as ‘fragile’, if the values of CFI or RCFI was found to be less than or equal to the number of patients lost to follow-up; (2) providing a description of the median values of CFI, CFQ, RCFI, and RCFQ, paired with their IQRs, according to the reported P value.

2.8. Statistical analysis

We presented continuous variables as the median with IQR and categorical variables as the number of occurrences with proportions represented as percentages (%). As most data did not follow the normal distribution assumption, all statistical fragility measures were reported as median with IQR, or range. The overall fragility index and fragility quotient were calculated, and subgroup analyses were performed based on various study characteristics, such as RCT registration platform, randomization method and intervention. Group differences were assessed using the Mann–Whitney U-test for comparisons involving two groups and the Kruskal–Wallis test for comparisons involving more than two groups. The correlation was measured using Spearman’s correlation. Spearman’s correlation coefficient (Rs) values between 0.10 and 0.39 as weak, between 0.40 and 0.69 as moderate, between 0.70 and 0.89 as strong [25–27].

Two sensitivity analyses were conducted. The first involved calculating the statistical fragility only for outcomes reported as mean ± SDs for both groups. The second involved excluding outcomes with CFIs of 0 from the Spearman’s correlation analysis.

All data analysis was performed using R, version 4.2.3, software (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). All tests of significance were two-tailed, with a pre-specified significance level of α = 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Overall characteristics of included trials

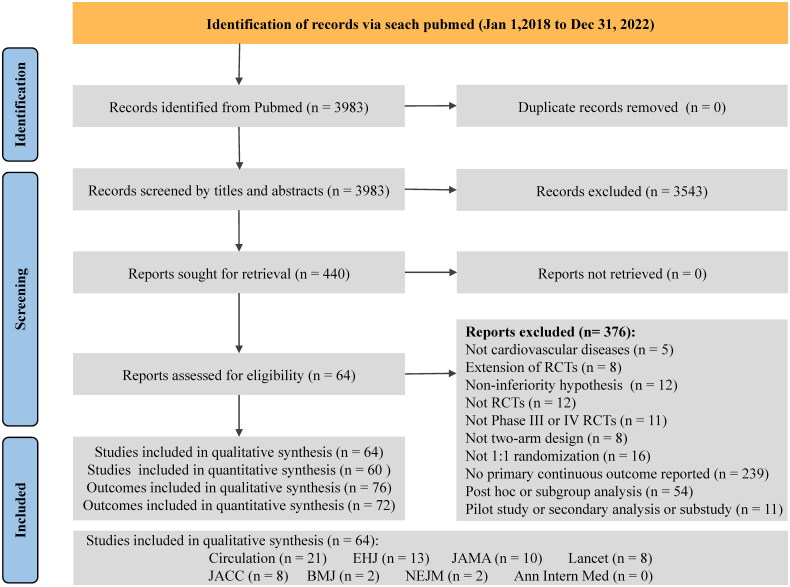

A total of 3983 records were identified, and out of these, 440 were eligible for full-text review. Eventually, 64 studies were included for the qualitative analysis, comprising 76 primary continuous outcomes. The Cohen’s κ coefficient for the agreement between reviewers was 0.675 (95% CI 0.638–0.712), indicating substantial agreement. Among the included studies, 32.8% (21/64) were published in Circulation, 20.3% (13/64) in EHJ, 15.6% (10/64) in JAMA, 12.5% (8/64) in Lancet, 12.5% (8/64) in JACC, 3.13% (2/64) in BMJ and 3.13% (2/64) in NEJM. The flowchart can be found in Figure 1, and the complete list of included studies is available in Appendix B.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for continuous outcomes.

Abbreviations: Ann Intern Med: Annals of Internal Medicine; EHJ: European Heart Journal; JACC: Journal of the American College of Cardiology; JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association; NEJM: the New England Journal of Medicine; RCT: randomized controlled trial.

The characteristics of all included RCTs are presented in Appendix C. Out of the 64 RCTs, 81.25% (52/64) were registered on ClinicalTrials.gov, 82.81% (53/64) were multi-center trials, and 70.31% (45/64) were conducted in a single country. 78.13% (50/64) of the RCTs used stratified blocked randomization, stratified randomization or block randomization. 48.44% (31/64) of the RCTs involved pharmaceutical intervention, and 35.94% (23/64) had placebo control. Regarding statistical analysis, 76.32% (58/76) of the primary outcomes were adjusted by covariates, 64.47% (49/76) were analysed based on the intention-to-treat principle, 3.95% (3/76) did not report an estimated sample size, and 34.94% (29/76) did not report how missing values were handled. Additionally, 90.79% (69/76) of the primary outcomes used a p < 0.05 as the threshold for statistical significance. Only 4.69% (3/64) of the RCTs involved public or patient involvement, 31.25% (20/64) posted their results online, and 40.63% (26/64) were funded by the industry.

We calculated the fragility indexes and fragility quotients for all outcomes. The overall CFI in continuous outcomes had a median of 7 (IQR 3.00–15.25), and the overall CFQ had a median of 0.032 (IQR 0.018–0.076). The RCTs registered on ClinicalTrials.gov had higher CFI compared to other platforms, with a median CFI of 7.00 (IQR 3.75–15.20). Similarly, multi-centre RCTs had higher CFI compared to single centre, with a median CFI of 7.00 (IQR 4.00–18.50). The overall CFI and CFQ based on other characteristics, such as the number of participating countries and randomization methods are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Fragility indexes and fragility quotients for all continuous outcomes based on the characteristics.

| Characteristics | No. | Overall CFI, Median (IQR) | P value | Overall CFQ, Median (IQR) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All outcomes | 72 | 7.00 (3.00–15.25) | — | 0.032 (0.018–0.076) | — |

| All outcomes excluded CFIs were 0 | 65 | 7 (4–17) | — | 0.038 (0.022–0.083) | — |

| RCT registration platform | |||||

| ClinicalTrials.gov | 60 | 7.00 (3.75–15.20) | 0.493 | 0.037 (0.019–0.088) | 0.080 |

| Other platforms | 11 | 4 (2–15) | 0.021 (0.016–0.029) | ||

| Not reported | 1 | 5 (5–5) | 0.071 (0.071–0.071) | ||

| No. of participating centres | |||||

| Multi-centres | 58 | 7.00 (4.00–18.50) | 0.253 | 0.032 (0.019–0.086) | 0.977 |

| Single centre | 10 | 4.00 (2.00–8.25) | 0.033 (0.020–0.069) | ||

| Not reported | 4 | 7.00 (5.25–25.50) | 0.035 (0.023–0.049) | ||

| No. of participating countries | |||||

| Single | 50 | 5.50 (3.00–9.00) | 0.094 | 0.030 (0.017–0.061) | 0.176 |

| 2 to 9 | 15 | 11.00 (5.00–37.50) | 0.057 (0.028–0.116) | ||

| 10 or more (max is 15) | 7 | 7 (6–104) | 0.028 (0.019–0.099) | ||

| Randomization methods | |||||

| Stratified blocked randomization | 32 | 7.50 (4.00–31.20) | 0.192 | 0.038 (0.021–0.088) | 0.162 |

| Stratified randomization | 14 | 7.50 (4.00–9.00) | 0.031 (0.021–0.039) | ||

| Block randomization | 11 | 3 (1–6) | 0.017 (0.005–0.035) | ||

| Other | 7 | 6 (3–102) | 0.054 (0.024–0.068) | ||

| Not reported | 8 | 7.50 (5.50–42.80) | 0.064 (0.030–0.140) | ||

| Intervention group | |||||

| Pharmaceutical | 34 | 6.50 (3.25–13.50) | 0.046* | 0.035 (0.021–0.069) | 0.037* |

| Surgical | 10 | 5.00 (3.25–8.50) | 0.034 (0.017–0.075) | ||

| Medical devices | 4 | 123 (41–210) | 0.109 (0.099–0.156) | ||

| Other | 24 | 6.50 (3.00–23.00) | 0.027 (0.013–0.064) | ||

| Control group | |||||

| Placebo | 25 | 7 (4–15) | 0.360 | 0.041 (0.023–0.083) | 0.389 |

| Other inactive control | 23 | 9 (4.00–31.50) | 0.038 (0.014–0.082) | ||

| With an active control | 24 | 5.00 (2.75–8.25) | 0.029 (0.018–0.039) | ||

| Covariates adjustment | |||||

| Yes | 54 | 7.00 (3.00–14.20) | 0.450 | 0.032 (0.016–0.076) | 0.635 |

| No | 18 | 5.50 (4.00–22.80) | 0.034 (0.025–0.078) | ||

| Analyzed principle | |||||

| ITT | 47 | 7.00 (4.00–17.50) | 0.435 | 0.038 (0.023–0.076) | 0.389 |

| FAS | 9 | 4 (3–17) | 0.023 (0.019–0.083) | ||

| MITT | 2 | 5.50 (3.75–7.25) | 0.022 (0.018–0.026) | ||

| PPS | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Not reported | 13 | 5 (3–14) | 0.031 (0.015–0.075) | ||

| Sample size estimation | |||||

| Less than 100 (min is 40) | 18 | 3.00 (1.25–6.50) | 0.001* | 0.038 (0.015–0.076) | 0.781 |

| 101-500 | 39 | 7.00 (4.00–14.50) | 0.030 (0.021–0.086) | ||

| More than 500 (max is 3500) | 12 | 33.50 (8.75–87.50) | 0.034 (0.014–0.058) | ||

| Not reported | 3 | 195 (97.50–224.00) | 0.088 (0.044–0.102) | ||

| Sample size | |||||

| Less than 100 (min is 40) | 14 | 2.00 (0.25–4.50) | <0.001* | 0.025 (0.003–0.074) | 0.539 |

| 101-500 | 44 | 6.50 (4.00–12.50) | 0.032 (0.021–0.085) | ||

| More than 500 (maxi is 3959) | 14 | 47 (9–172) | 0.046 (0.015–0.068) | ||

| The threshold for statistical significance | |||||

| p<.05 (two sided or one sided) | 65 | 6 (3-15) | 0.307 | 0.030 (0.017–0.076) | 0.948 |

| Other (p<.025 or .048, two sided) | 3 | 7.00 (4.50–7.50) | 0.040 (0.025–0.064) | ||

| Not reported | 4 | 33.50 (18.20–62.00) | 0.035 (0.031–0.047) | ||

| Public or patient involvement | |||||

| Yes | 4 | 8.50 (6.75–17.80) | 0.614 | 0.017 (0.015–0.032) | 0.253 |

| No | 68 | 6.50 (3.00–15.20) | 0.035 (0.020–0.078) | ||

| Posted results online | |||||

| Yes | 23 | 11 (6–128) | 0.002* | 0.057 (0.029–0.109) | 0.007* |

| No | 49 | 5 (3–9) | 0.029 (0.014–0.060) | ||

| Funding | |||||

| Industry | 28 | 7.00 (4.00–15.50) | 0.187 | 0.045 (0.027–0.092) | 0.048* |

| Non-profit funding | 35 | 6 (2–9) | 0.025 (0.014–0.039) | ||

| Combination | 7 | 190 (4–206) | 0.054 (0.031–0.075) | ||

| No funding | 1 | 3 (3–3) | 0.075 (0.075–0.075) | ||

| Not reported | 1 | 85 (85–85) | 0.276 (0.276–0.276) | ||

Numbers reported as median [interquartile range].

Significance noted by (*).

Abbreviations: CFI, continuous fragility index; CFQ, continuous fragility quotient; FAS, full analysis set; IQR, interquartile range; ITT, intention to treat; MITT, modified intention to treat; PPS, per protocol set.

Simultaneously, the degree of robustness was associated with some aspects of the study design. We observed statistically significant differences in the overall CFI and CFQ due to different intervention measures (p = 0.046 and p = 0.037, respectively) and posting results online or not (p = 0.002 and p = 0.007, respectively). Sample size estimation (p = 0.001) and actual sample size (p < 0.001) also displayed significant correlations with the overall CFI. Furthermore, the overall CFQ exhibited a significant association with the funding source (p = 0.048). RCTs with a higher CFI score (less fragile) were more often international, multi-centre, involved medical device interventions, had inactive control except for placebo, had sample sizes ranging from 101–500, conducted intention-to-treat analysis, and were funded by non-profit sources. (Table 1).

3.2. Continuous fragility index and quotient in positive or negative outcomes

Table 2 provides an overview of the primary continuous outcomes recorded in all studies included in the analysis. Out of the 76 outcomes, 56.6% (43/76) were initially reported as statistically significant, while 43.4% (33/76) were initially nonsignificant. The median sample size for initially significant outcomes was 164 patients (IQR 101–479), with a median follow-up duration of 6 months (IQR 3–12). Conversely, for initially nonsignificant outcomes, the median sample size was 200 patients (IQR 129–331), with a median follow-up duration of 4 months (IQR 3–10.5).

Table 2.

Characteristics, fragility indexes and quotients for continuous outcomes in included RCTs, stratified by statistically significant or nonsignificant.

| Reported P value, p < 0.05& (n = 43) |

Reported P value, p > 0.05 (n = 33) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Median (IQR) | Range | No. | Median (IQR) | Range | |

| Sample size estimation | 40 | 150 (86–385) | 40–3500 | 33 | 210 (120–320) | 40–2262 |

| Sample size | 43 | 164 (101–479) | 40–3959 | 33 | 200 (129–331) | 40–2441 |

| No. of patients dropout | 15 | 18 (4–137) | 0–315 | 6 | 3 (1–13.25) | 1-24 |

| No. of patients dropout (withdraw consent) | 22 | 5 (1.5–22) | 0–191 | 12 | 3.5 (2–9.25) | 0-49 |

| No. of patients lost to follow-up | 27 | 3 (1–36) | 0-357 | 17 | 3 (2–13) | 0-124 |

| No. of patients analysed | 43 | 150 (91–451.5) | 40–3921 | 33 | 197 (129–315) | 32-2346 |

| Follow-up (months) | 42 | 6 (3–12) | 0.003–36 | 31 | 4 (3–10.5) | 0.03-36 |

| CFI or RCFI* | 41 | 14 (3–51) | 0–254 | 31 | 5 (3.50–7.00) | 2-9 |

| CFQ or RCFQ* | 41 | 0.062 (0.028–0.105) | 0–0.424 | 31 | 0.023 (0.015–0.036) | 0.002-0.075 |

| CFI or RCFI# | 23 | 8 (2–35) | 0–254 | 11 | 5 (3.50–6.50) | 2–9 |

| CFQ or RCFQ# | 23 | 0.076 (0.017–0.109) | 0–0.424 | 11 | 0.022 (0.015–0.030) | 0.002–0.048 |

Values are presented as median [interquartile range].

Abbreviations: CFI, continuous fragility index; CFQ, continuous fragility quotient; IQR, interquartile range; RCFI, reverse continuous fragility index; RCFQ, reverse continuous fragility quotient.

&The specific P values for the three outcomes were not reported, however, based on the corresponding 95% CIs that exclude null values, it can be inferred that the P values are less than 0.05.

*Four studies failed to report adequate data for computing the mean or standard deviation, and were omitted from the fragility index and quote calculation.

#A sensitivity analysis was performed only considering cases where the studies provided information on means, standard deviations, and sample sizes.

For the calculation of CFI or RCFI, four RCTs were excluded due to inadequate data. In the case of the 41 initially significant outcomes, the median CFI was 14 (IQR 3–51), with the median CFQ was 0.062 (IQR 0.028–0.105). For the 31 initially nonsignificant outcomes, the median CFI was 5 (IQR 3.50–7.00), with the median CFQ was 0.023 (IQR 0.015–0.036). Further details are available in Table 2.

A sensitivity analysis was also conducted, and the results can be found in Table 2. For the 23 initially significant outcomes, the median CFI was 8 (IQR 2–35), and the median CFQ was 0.076 (IQR 0.017–0.109). For the 11 initially nonsignificant outcomes, the median CFI was 5 (IQR 3.50–6.50), and the median CFQ was 0.022 (IQR 0.015–0.030). It is worth noting that the initially significant outcomes revealed that 17.1% (7/41) had a calculated CFI of 0. More detailed information on these outcomes can be found in Appendix D.

Furthermore, among the studies that reported the number of patients lost to follow-up, 36.0% (9/25) of primary significant outcomes had a reported number of patients greater than their CFI. Moreover, 46.7% (7/15) of primary nonsignificant outcomes had a greater number of patients than their RCFI. Therefore, we considered these outcomes as “fragile”. More detailed information can be found in Appendix D.

3.3. Correlation of characteristics with fragility index

The analysis revealed significant correlations between the CFI and several variables. Specifically, there was a strong positive correlation with sample size (Rs = 0.77, p = 3.74e − 09), number of patients all dropout (Rs = 0.79, p = 4.85e − 04), and number of patients analyzed (Rs = 0.78, p = 1.64e − 09). Additionally, there was a moderate positive correlation with number of patients dropout due to withdraw consent (Rs = 0.58, p = 5.78e − 03), number of patients lost to follow-up (Rs = 0.55, p = 4.50e − 03). Similarly, the RCFI also showed a associations with these variables. It had a strong positive correlation with number of patients all dropout (Rs = 0.89, p = 0.02). Additionally, there was a moderate positive correlation with sample size (Rs = 0.57, p = 7.85e − 04), and number of patients analysed (Rs = 0.55, p = 1.41e − 03). In contrast, the RCFQ demonstrated a negative strong correlation with sample size (Rs = −0.76, p = 8.76e − 07) and number of patients analysed (Rs = −0.77, p = 5.09e − 07). Furthermore, it had a negative moderate correlation with journal impact factor (Rs = −0.52, p = 3.00e − 03). Importantly, these trends remained consistent even when excluding outcomes where the CFIs or CFQs were 0. These associations were indicated in Table 3 (Figures in Appendix E).

Table 3.

The correlation between continuous fragility index or quotient, reverse continuous fragility or quotient, and study characteristics.

| Study characteristics | CFI (n = 41) |

RCFI (n = 31) |

CFI (n = 34)# |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rs | P | Rs | P | Rs | P | |

| Sample size | 0.77 | 3.74e − 09* | 0.57 | 7.85e − 04* | 0.85 | 1.84e − 10* |

| No. of patients dropout | 0.79 | 4.85e − 04* | 0.89 | 0.02* | 0.86 | 7.15e − 05* |

| No. of patients dropout (withdraw consent) | 0.58 | 5.78e − 03* | 0.24 | 0.48 | 0.6 | 6.82e − 03* |

| No. of patients lost to follow-up | 0.55 | 4.50e − 03* | −0.38 | 0.16 | 0.68 | 1.48e − 03* |

| No. of patients analyzed | 0.78 | 1.64e − 09* | 0.55 | 1.41e − 03* | 0.85 | 2.20e − 10* |

| Follow-up (months) | 0.26 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.12 | 0.49 |

| Journal impact factor | 0.27 | 0.08 | 0.1 | 0.61 | 0.17 | 0.34 |

| Study characteristics | CFQ (n = 41) | RCFQ (n = 31) | CFQ (n = 34)* | |||

| Rs | P | Rs | P | Rs | P | |

| Sample size | 0.25 | 0.11 | −0.76 | 8.76e − 07* | 0.06 | 0.73 |

| No. of patients dropout | 0.16 | 0.58 | 0.03 | 0.95 | 0.16 | 0.59 |

| No. of patients dropout (withdraw consent) | −0.12 | 0.61 | −0.06 | 0.87 | −0.24 | 0.31 |

| No. of patients lost to follow-up | −0.05 | 0.79 | −0.31 | 0.27 | −0.32 | 0.18 |

| No. of patients analyzed | 0.26 | 0.1 | −0.77 | 5.09e − 07* | 0.05 | 0.77 |

| Follow-up (months) | 0.09 | 0.59 | −0.31 | 0.1 | −0.11 | 0.53 |

| Journal impact factor | 0.21 | 0.19 | −0.52 | 3.00e − 03* | 0.08 | 0.67 |

Significance noted by (*).

#Excluding the outcomes of CFIs or CFQs were 0.

Abbreviations: CFI, continuous fragility index; CFQ, continuous fragility quotient; P, P values; RCFI, reverse continuous fragility index; RCFQ, reverse continuous fragility quotient; Rs, Spearman’s correlation coefficient.

4. Discussions

The concept of fragility index was first proposed by Feinstein et al. [21] in 1990. Walsh et al. [13] further developed this concept in 2014, giving a simplified and intuitive connotation. The fragility index measures the minimum number of events needed to alter the results of a study from significant to nonsignificant, for binary outcomes with a 2 × 2 contingency table of two parallel arms in a 1 to 1 ratio. A lower fragility index indicates that a smaller number of events could potentially change the conclusion of the trial. It offers a quantitative measure of RCT robustness and provides a more nuanced understanding of the stability of their results beyond the traditional P value. In 2021, Caldwell et al. [17] introduced an iterative substitution algorithm to compute the CFI, an extension of the fragility index to continuous outcomes. However, to our knowledge, only a few study have used this method to assess the fragility of studies with continuous outcomes [28–32]. It is important to recognize that like the P value, the fragility index primarily focuses on statistical significance, not clinical significance.

Our cross-sectional study, we provides an in-depth analysis of the robustness of the primary continuous outcomes from cardiovascular RCTs published in eight high-impact journals. We employed several robustness indicators, including the CFI, CFQ, RCFI, and RCFQ to evaluate the ease with which statistical significance may be changed based on the pre-specified P value threshold. This study is the first fragility analysis of continuous outcomes in the cardiovascular field. We have reported several key findings from this analysis.

First, the current study of 64 cardiovascular RCTs, including 72 primary continuous outcomes published from 2018 to 2022, we observed a considerable number of outcomes with a low overall fragility index. Approximately 43.1% (31/72) of these outcomes indicated that a small shift of five or fewer patients in the intervention group could lead to a statistically significant reversal of the results. The overall median CFI was 7, with an associated median CFQ of 0.032. This suggests that changing the intervention of 7 patients (or 3.2 out of 100 patients) would have been required to reverse the trial’s significance. Similar findings of common fragility in trials have been observed in several diseases such as plantar fasciitis, chronic noninsertional achilles tendinopathy, adolescent idiopathic scoliosis, and pulmonary arterial hypertension [28–31]. Specifically, studies analyzing continuous outcomes have yielded median CFIs ranging from 5 to 13, with associated CFQs ranging from 0.141 to 0.177 [28–31].

There was a difference range with prior studies assessing statistical fragility in cardiovascular trials with discontinuous outcomes. For instance, Khan et al. [7] evaluated cardiovascular RCTs with sample sizes over 500 participants that had a statistically significant primary outcome and showed a median FI of 13 (IQR 5–26). They found a similar result with Murad et al. [16], who investigated the FI of modern and likely influential cardiovascular RCTs that enrolled 500 or more participants, were published in high impact journals and had a statistically significant primary outcome. The median FI of the 201 included cardiovascular trials was 13 (range 1–172). It is important to note that the quantitative results from our study cannot be directly compared to these values, due to inherent differences between the CFI and the traditional FI for dichotomous outcomes. The FI refers to the number of patients needed to change their results to impact significance, while the CFI refers to the number of patients required to modify significance by altering their intervention [13,17].

Additionally, our study found that outcome events with nonsignificant P values showed greater statistical instability (median RCFI = 5, RCFQ = 0.023) compared to events with significant P values (median CFI = 14, CFQ = 0.062). These results were consistent across sensitivity analyses. These findings are in line with the trends observed in the study by Gupta et al. [28] but differ from those reported by Xu et al. [29] and Gupta et al. [30]. A lower CFI or RCFI indicates less stability based on the ability of intervention changes to reverse statistical significance. Currently, there is no universally accepted cutoff for fragility. It is worth noting that the concept of fragility can be extended to studies with nonsignificant results, but it is possible that nonsignificant studies may never be altered to achieve significance.

A second important finding of this study is that 36% (9/25) CFI or 46.7% (7/15) RCFI values was lower than the number of patients lost to follow-up in reported outcomes, and defined as “fragile”. This larger proportion was also found in other dichotomous and continuous outcomes. For instance, Xu et al. [29] reported that 23.1% (12/52) of outcomes had their number of patients lost to follow-up exceeding the FI or CFI values. Murad et al. [16] found that in 22.89% (46/201) of trials, the FI values exceeded the number of patients lost to follow-up. Remarkably, Gonzalez-Del-Hoyoet al. [33] indicated that 47.0% (62/132) RCTs, the number of patients lost to follow-up exceeded the FI values.

The number of patients lost to follow-up was frequently greater than the calculated CFIs and RCFIs, indicating a potential reversal of significance if all patients had completed the protocol as designed [34,35]. Consequently, the results of such trials were considered even more fragile and less robust, warranting the need for improvement in patient follow-up.

Currently, there is no standardized threshold value to declare a result as “robustness” or ‘fragility’. However, it is worth noting that lower CFI or RCFI suggests less statistical robustness. A few studies have explored FI thresholds for dichotomous outcomes in cardiology. Vukadinović et al. [36] categorized discontinuous findings into three groups based on FI or RFI. According to their analysis, an FI or RFI < 20 was considered fragile, an FI or RFI from 20 to 40 was considered moderately robust, and an FI or RFI equal to or exceeding 40 was considered robust. In a meta-epidemiologic study conducted by Murad et al. [16], they estimated the area under the curve to determine the FI value that best predicts whether the treatment effect was precise. They found that the FI values in the range of 19–22 may meet various definitions of precision and can be used as a rule of thumb to suggest that a treatment effect is likely precise and less susceptible to random error. They defined precision as adequately powered for a plausible relative risk reduction (RRR) of 25% or 30%, or having a CI that is sufficiently narrow to exclude a risk reduction that is too small (close to the null, <0.05).

Finally, our analysis robustly illustrated that the CFI and RCFI exhibited moderate to strong correlations with sample size, the number of total dropouts and the number of patients analysed. Moderate to strong correlations were also observed between the CFI and the number of patients withdrawing consent and those lost to follow-up. Conversely, the RCFQ displayed moderate to strong negative correlations with sample size, the number of patients analysed and journal impact factor. These significant relationships persisted in a sensitivity analysis. Previous studies have also examined similar factors in relation to dichotomous outcomes [14,15,33], further emphasizing the importance of these variables in assessing the fragility and robustness of cardiovascular randomized controlled trial outcomes. Consequently, our findings underscore the need for well-designed trials with appropriate sample sizes and the implementation of strategies to minimize dropouts. Meanwhile, these findings emphasize the necessity of designing trials with appropriate sample sizes and implementing strategies to minimize dropouts.

Additionally, in a few instances, we observed a calculated CFI was zero. This could indicate a possible discrepancy between the reported and reanalysed results, suggesting that the trial outcomes might not be reproducible using Welch’s t-test. It’s worth noting that the continuous data were reported as mean ± SD, which theoretically assumes a normal Gaussian distribution. However, some authors might have included non-parametric data in their mean ± SD reporting. The choice of the Welch t-test as the statistical test for calculating CFI or CRFI may be considered somewhat crude, especially since some of the included RCTs were analysed with models using covariates. Furthermore, our method assumed normality in the underlying data, and the simulated datasets may not precisely represent the true distribution of the original dataset, particularly for heavily skewed data. To compensate for this, we generated multiple simulated datasets and averaged the results, but this approach might not be adequate for all scenarios. These findings emphasize the critical importance of transparency and comprehensive reporting in clinical trials. Full disclosure of methodologies and data can aid in the accurate interpretation and replication of trial results, promoting greater reliability in research outcomes.

4.1. Limitations

Our study is the first to include fragility analyses of continuous outcomes that were initially nonsignificant (p > 0 .05) in cardiovascular, for which we are not aware of any other benchmark data. There were several inherent limitations. Firstly, our study lacked access to raw data. While we utilized available information to approximate missing data in the calculation of the fragility index, although conducted a sensitivity analysis which yielded similar results, this aspect could potentially introduce a level of uncertainty into our calculations. Secondly, there is currently no defined interpretation of CFI or RCFI, and there is also no standardized threshold value to declare a result as ‘fragile’. We defined as ‘fragile’ if the values of CFI or RCFI was found to be less than or equal to the number of patients lost to follow-up. Thirdly, in our analysis, the calculations of the CFI and RCFI did not include the covariate adjustments found in the original studies. This exclusion could potentially impact the precision of our outcomes. Nevertheless, in situations where the original data, inclusive of these adjustments, is unavailable, our approach offers an expedient means to assess the robustness of continuous outcomes. Yet, it is crucial to approach the interpretation of these results with a heightened level of caution. Finally, the cross-sectional survey we conducted only focused on high-impact journals, which may have underestimated the findings according to Kampman ea al. [37]. The RCTs in lower tier journals may even have lower CFI or RCFI values because they likely have smaller sample size.

5. Conclusion

Our study found that the range of robustness differs between continuous and dichotomous primary outcomes and similar observations have been made in previous studies across different medical specialties. This research underscores the importance of raising awareness among researchers, clinicians, and policymakers about the fragility of results in certain trials and involving patient involvement in future trials. Future research should incorporate measures of CFI, CFQ, RCFI, and RCFQ, alongside traditional P value, provides a more comprehensive interpretation of study results and higher quality evidence in cardiology. Considering recent proposals to lower the P value threshold, we recommend setting the threshold at 0.01 or 0.005 to explore the fragility of results. We suggest that future studies focus on developing guidelines for the application and interpretation of the fragility index in cardiovascular research. In addition, to promote better evidence-based decision-making, we suggest that the fragility index as one of the criteria considered for evidence synthesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Wenbo He from West China Hospital, Sichuan University, for her valuable methodological suggestions during the revision of this manuscript and for providing funding support through the Sichuan University Interdisciplinary Innovation Fund.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 72074161] and Sichuan University Interdisciplinary Innovation Fund.

Author’s contributions

Zhou Xiaoqin: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Software, Data Curation, Writing-Original Draft, Writing-Reviewing and Editing. Ruan Weiqing: Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing-Reviewing and Editing. Zhang Guiying: Investigation. Liu Huizhen: Investigation. Wang Ting: Investigation. Li Jing: Conceptualization, Writing-Reviewing and Editing. Du Liang: Conceptualization, Writing- Reviewing and Editing, Funding acquisition. Huang Jin: Conceptualization, Writing- Reviewing and Editing.

Ethics approval and patient consent

Not applicable. This cross-sectional study, which exclusively relied on publicly available data for analysis and did not involve patients, did not require institutional review board approval or informed consent.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. Extraction data are available on the Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/qxwd3?view_only=e021991734fd4be5ad523d8fb21f96ad.

Patient and public involvement

This research did not involve patients or the public in the design, conduct, reporting, or dissemination plans.

References

- 1.Vaduganathan M, Mensah GA, Turco JV, et al. The global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk: a compass for future health. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;80(25):2361–2371. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindstrom M, DeCleene N, Dorsey H, et al. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risks collaboration, 1990-2021. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;80(25):2372–2425. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, et al. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ. 1996;312(7023):71–72. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hariton E, Locascio JJ.. Randomised controlled trials - the gold standard for effectiveness research: study design: randomised controlled trials. BJOG. 2018;125(13):1716–1716. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.15199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baasan O, Freihat O, Nagy DU, et al. Methodological quality and risk of bias assessment of cardiovascular disease research: analysis of randomized controlled trials published in 2017. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:830070. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.830070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andrade C. The P value and statistical significance: misunderstandings, explanations, challenges, and alternatives. Indian J Psychol Med. 2019;41(3):210–215. doi: 10.4103/IJPSYM.IJPSYM_193_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khan MS, Ochani RK, Shaikh A, et al. Fragility Index in cardiovascular randomized controlled trials. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2019;12(12):e005755. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.119.005755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sidali S, Sritharan N, Campani C, et al. Fragility Index of positive phase II and III randomised clinical trials of treatments for hepatocellular carcinoma (2002-2022). JHEP Rep. 2023;5(7):100755. doi: 10.1016/j.jhepr.2023.100755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cordero JK, Lawrence KW, Brown AN, et al. The fragility of tourniquet use in total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Arthroplasty. 2023;38(6):1177–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2022.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hameed NUF, Zhang X, Sajjad O, et al. Robustness of randomized control trials supporting current neurosurgery guidelines. Neurosurgery. 2023;93(3):539–545. doi: 10.1227/neu.0000000000002463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayes J, Zuercher M, Gai N, et al. The fragility index of randomized controlled trials in pediatric anesthesiology. Can J Anaesth. 2024;7(1):165–166. doi: 10.1007/s12630-023-02513-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kampman JM, Sperna Weiland NH, Hermanides J, et al. Randomized controlled trials in ICU in the four highest-impact general medicine journals. Crit Care Med. 2023;51(9):e179–e183. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000005937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walsh M, Srinathan SK, McAuley DF, et al. The statistical significance of randomized controlled trial results is frequently fragile: a case for a fragility index. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(6):622–628. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dhingra NK, Li A, Lee G, et al. Reverse fragility index in negative cardiac procedural randomized controlled trials. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2023;35(3):493–496. doi: 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2022.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaudino M, Hameed I, Biondi-Zoccai G, et al. Systematic evaluation of the robustness of the evidence supporting current guidelines on myocardial revascularization using the fragility index. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2019;12(12):e006017. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.119.006017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murad MH, Kara Balla A, Khan MS, et al. Thresholds for interpreting the fragility index derived from sample of randomised controlled trials in cardiology: a meta-epidemiologic study. BMJ Evid Based Med. 2023;28(2):133–136. doi: 10.1136/bmjebm-2021-111858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caldwell JE, Youssefzadeh K, Limpisvasti O.. A method for calculating the fragility index of continuous outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021;136:20–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, et al. Rayyan - a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):210. Available from https://rayyan.qcri.org/. Retrieved on June 23, 2023. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tang W, Hu J, Zhang H, et al. Kappa coefficient: a popular measure of rater agreement. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2015;27(1):62–67. doi: 10.11919/j.issn.1002-0829.215010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Landis JR, Koch GG.. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–174. doi: 10.2307/2529310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feinstein AR. The unit fragility index: an additional appraisal of “statistical significance” for a contrast of two proportions. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43(2):201–209. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(90)90186-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jpt, T Jj. (editors). Chapter 6: choosing Effect Measures and Computing Estimates of Effect. In: higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.3 (updated February 2022). Cochrane, 2022. Available from Higgins Li Deeks www.training.cochrane.org/handbook. Retrieved on June 23, 2023.

- 23.Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I.. Estimating the Mean and Variance From the Median, Range, and the Size of a Sample. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005;5:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-5-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rohatgi A. WebPlotDigitizer (Version 4.6) [Computer software]. Avaliable from:https://automeris.io/WebPlotDigitizer. Retrieved on June 23, 2023.

- 25.Mukaka MM. Statistics corner: a guide to appropriate use of correlation coefficient in medical research. Malawi Med J. 2012;24(3):69–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Overholser BR, Sowinski KM.. Biostatistics primer: part 2. Nutr Clin Pract. 2008;23(1):76–84. doi: 10.1177/011542650802300176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schober P, Boer C, Schwarte LA.. Correlation coefficients: appropriate use and interpretation. Anesth Analg. 2018;126(5):1763–1768. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000002864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gupta A, Ortiz-Babilonia C, Xu AL, et al. The statistical fragility of platelet-rich plasma as treatment for plantar fasciitis: a systematic review and simulated fragility analysis. Foot Ankle Orthop. 2022;7(4):24730114221144049. doi: 10.1177/24730114221144049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu AL, Ortiz-Babilonia C, Gupta A, et al. The statistical fragility of platelet-rich plasma as treatment for chronic noninsertional achilles tendinopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Foot Ankle Orthop. 2022;7(3):24730114221119758. doi: 10.1177/24730114221119758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gupta A, Mo K, Movsik J, et al. Statistical fragility of ketamine infusion during scoliosis surgery to reduce opioid tolerance and postoperative pain. World Neurosurg. 2022;164:135–142. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2022.04.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garcia MVF, Coz-Yataco A, Al-Jaghbeer MJ.. Pulmonary arterial hypertension trials put to the test: using the fragility index to assess trials robustness. Heart Lung. 2023;61:147–152. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2023.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ho AK. The fragility index for assessing the robustness of the statistically significant results of experimental clinical studies. J Gen Intern Med. 2022; 37(1):206–211. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-06999-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gonzalez-Del-Hoyo M, Mas-Llado C, Blaya-Peña L, et al. The fragility index in randomized clinical trials supporting clinical practice guidelines for acute coronary syndrome: measuring robustness from a different perspective. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2023;12(6):386–390. doi: 10.1093/ehjacc/zuad021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baer BR, Fremes SE, Gaudino M, et al. On clinical trial fragility due to patients lost to follow up. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2021;21(1):254. doi: 10.1186/s12874-021-01446-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin L, Xing A, Chu H, et al. Assessing the robustness of results from clinical trials and meta-analyses with the fragility index. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2023;228(3):276–282. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2022.08.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vukadinović D, Abdin A, Emrich I, et al. Efficacy and safety of intravenous iron repletion in patients with heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Res Cardiol. 2023;112(7):954–966. doi: 10.1007/s00392-023-02207-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kampman JM, Turgman O, Sperna Weiland NH, et al. Statistical robustness of randomized controlled trials in high-impact journals has improved but was low across medical specialties. J Clin Epidemiol. 2022;150:165–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2022.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. Extraction data are available on the Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/qxwd3?view_only=e021991734fd4be5ad523d8fb21f96ad.