Abstract

Folate receptor α (FRα) is a well-studied tumor biomarker highly expressed in many epithelial tumors such as breast, ovarian, and lung cancers. Mirvetuximab soravtansine (IMGN853) is the antibody-drug conjugate of FRα-binding humanized monoclonal antibody M9346A and cytotoxic maytansinoid drug DM4. IMGN853 is currently being evaluated in multiple clinical trials, in which immunohistochemical evaluation of archival tumor or biopsy specimen is used for patient screening. However, limited tissue collection may lead to inaccurate diagnosis due to tumor heterogeneity. Herein, we developed a zirconium-89 (89Zr)-radiolabeled M9346A (89Zr-M9346A) as an immuno-positron emission tomography (immuno-PET) radiotracer to evaluate FRα expression in triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) patients, providing a novel means to guide intervention with therapeutic IMGN853. In this study, we verified the binding specificity and immunoreactivity of 89Zr-M9346A by in vitro studies in FRαhigh cells (HeLa) and FRαlow cells (OVCAR-3). In vivo PET/computed tomography (PET/CT) imaging in HeLa xenografts and TNBC patient-derived xenograft (PDX) mouse models with various levels of FRα expression demonstrated its targeting specificity and sensitivity. Following PET imaging, the treatment efficiency of IMGN853, pemetrexed, IMGN853+pemetrexed, paclitaxel, and saline were assessed in FRαhigh and FRαlow TNBC PDX models. The correlation between 89Zr-M9346A tumor uptake and treatment response using IMGN853 in FRαhigh TNBC PDX model suggested the potential of 89Zr-M9346A PET as a noninvasive tool to prescreen patients based on the in vivo PET imaging for IMGN853 targeted treatment.

Keywords: folate receptor α, companion diagnostic, immuno-PET, antibody-drug conjugate, image-guided therapy

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

An emerging new paradigm in healthcare is precision medicine. Understanding individual genetic differences in patients with the same disease guides the transition from empirical therapy to personalized treatment.1–3 Characterization of a specific biomarker in each patient is essential to optimize the treatment strategy for personalized treatment. In addition to advances made by improved therapies, development of better diagnostics is imperative to not only identify appropriate patients for targeted treatment, but also monitor the dynamic response in real-time to optimize the treatment. To date, most biomarker analyses are done using tumor or blood samples, which are limited by scarcity in material, need for invasive procedures, tumor heterogeneity, temporal variation in expression and sampling error. In this regard, molecular imaging techniques have shown great potential as companion diagnostics with their capabilities to image and quantify activities of target molecules in vivo.4

Monoclonal antibodies have been one of the most effective targeted cancer diagnostics and therapeutics in precision medicine.5–7 Taking advantage of their high affinity to antigens specifically expressed on the surface of cancer cells, monoclonal antibody drugs work in various mechanisms such as stimulating immune systems, inhibiting biological activities of tumors, and delivering radiation treatment or chemotherapeutics. Among them, antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) are a fast-growing type of monoclonal antibody-based drugs for targeted treatment.8–10 Mirvetuximab soravtansine (IMGN853) is a folate receptor alpha (FRα)-targeting ADC comprised of humanized anti-FRα monoclonal antibody M9346A and the microtubule-disrupting maytansinoid, DM4.11 This allows targeted delivery of maytansinoid DM4 to FRα-expressing tumor cells and minimize the unacceptable systemic toxicity which led to failure of free-form maytansinoid drugs in previous clinical trials.12 Currently, multiple clinical trials of this promising ADC are in progress for triple negative breast cancer (TNBC), ovarian cancer, endometrial, fallopian tube, and primary peritoneal cancer, including the phase 3 FORWARD I trial.13–15 The participants for these clinical trials are currently screened by immunohistochemical (IHC) assessment of archival tumor tissues or biopsy samples. However, the main concern is that the archival tissues might not represent the current FRα levels of potential participants since receptor expression may vary over time. It was reported that FRα expression in biopsy tissues differed in 29% of archival tissues.15 In addition, biopsy accuracy may be affected by the heterogeneous nature of tumors and limited tissue collection. To address these clinical challenges, the goal of this study was to develop a M9346A antibody based molecular imaging agent to evaluate the expression of FRα in whole TNBC tumors, and more importantly to non-invasively guide the treatment using IMGN853 through 89Zr radiolabeling (89Zr-M9346A) and PET since the association between receptor expression and treatment response has been reported in preclinical and clinical studies.11, 16–17 89Zr-M9346A immuno-PET may be a useful, non-invasive molecular imaging tool to get a holistic view of FRα dynamic expression in the tumors. Herein, we reported the targeted PET imaging of FRα in multiple mouse TNBC models using 89Zr-M9346A. We demonstrated that tumor uptakes of 89Zr-M9346A correlated with FRα expression in TNBC tumors during the treatment, indicating its potential as a useful tool for image guided therapy of TNBC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

M9346A and IMGN853 were provided by ImmunoGen, Inc. (Waltham, MA). p-SCN-Bn-deferoxamine (p-SCN-DFO) was purchased from Macrocyclics, Inc (Plano, TX). 89Zr-oxalate and 18F-FDG were obtained from the Cyclotron Facility of the Washington University Medical Center. All other chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) and used as received. Water with a resistivity of 18.2 MΩ·cm was prepared by a Milli-Q® Integral 5 Water Purification System (Bedford, MA).

Cell Lines.

High FRα-expressing HeLa and low FRα-expressing OVCAR-3 cell lines were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and cultured in Eagle’s Minimum Essential Medium (EMEM) and RMPI media, respectively, and incubated under conditions (5% CO2 at 37 °C).

Mouse Models.

All animal studies were performed in compliance with guidelines set forth by the NIH Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare and approved by the institutional animal care and use committee of Washington University. For all experiments, mice at age 6–8 weeks were used after 5–7 days acclimation. For microPET/CT studies to evaluate tumor uptake of 89Zr-M9346A in HeLa xenografts, 5 × 107 HeLa cells in 100 μL with 50% Matrigel (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA) were subcutaneously inoculated into the right flank of individual female athymic nu/nu mouse (Charles River Laboratory, Wilmington, MA). The tumors were allowed to grow until average tumor volume reached approximately 100 mm3 for PET/CT imaging studies.

For breast cancer PET imaging studies, Washington University Human-in-Mouse (WHIM) lines were obtained from the Human and Mouse Linked Evaluation of Tumors (HAMLET) Core facility at Washington University. Six TNBC PDXs were engrafted subcutaneously into the flanks of male NSG™ mice (The Jackson Laboratory).

Preparation of 89Zr-Radiolabeled M9346A.

The FRα-binding M9346A antibody was radiolabeled with 89Zr (t1/2= 3.3 days) following previous reports.18 Briefly, the pH of M9346A solution (10.1 mg/mL) was adjusted to approximately pH 9 with 0.1 M Na2CO3, and mixed with 8 molar equivalents of p-SCN-DFO (8 mg/mL) in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). The resulting mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 1 h with gentle agitation (450 rpm). The crude DFO-M9346A conjugate was purified using PD MiniTrap G-25 desalting column (Sephadex G-25, GE Healthcare Life Sciences) with 1X PBS as an eluent.

The purified DFO-M9346A was radiolabeled with neutralized 89Zr-oxalate (pH 6.8–7.2 using 1 M HEPES buffer and 1 M NaOH) under a ratio of 296 kBq (8 μCi) to 1 μg at 37 °C for 1 h with gentle shaking (300 rpm). The radiochemical yields of 89Zr-M9346A were determined by instant radio-thin layer chromatography (radio-TLC) (Bioscan) using 50 mM DTPA (pH 6.9) as an eluent. Typical radiolabeling yield was >99%, and the specific activities of resulting 89Zr-M9346A were 222–296 kBq / μg (6–8 μCi / μg). Fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC) and radio-FPLC analysis were performed with a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL size exclusion column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences), using an ÄKTA FPLC system (GE Healthcare Bioscience) equipped with a Beckman 170 Radioisotope detector (Beckman Instruments, Fullerton, CA).

In Vitro Cell Binding Studies.

Cell binding assays were performed on high FRα expressing cells (HeLa) and low FRα expressing cells (OVCAR-3). Both HeLa and OVCAR-3 cells (0.5 × 106 cells in 500 μL of 1X PBS) were incubated with 18.5 kBq (0.5 μCi) of 89Zr-M9346A in microcentrifuge tubes at room temperature (triplicated). After 30 min, the cells were centrifuged (600 g × 2 min) and washed three times with 1 mL of ice-cold 1X PBS. Radioactivity bound to cells was measured using a 2480 automatic gamma counter WIZARD (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA). OVCAR-3 cells were used as a control. For blocking of FRα on HeLa cells, approximately 140-fold molar excess of non-radiolabeled DFO-M9346A was pre-incubated for 30 min before an addition of 89Zr-M9346A.

Competitive binding assays were conducted on HeLa cells. HeLa cells (0.5 × 106 cells in 500 μL of 1X PBS) were incubated with 7.8 × 10−10 M 89Zr-M9346A with different concentrations (7.8 × 10−12 – 7.8 × 10−6 M) of unlabeled M9346A in micro-centrifuge tubes at room temperature for 1 h (n=3). The cells were centrifuged (600 g × 2 min) and washed four times with 1 mL of ice-cold 1X PBS and measured in a gamma counter. The percentage of 89Zr-M9346A bound with / without competitor (B / B0 × 100) was plotted against log (concentrations of competitor) and fitted with nonlinear regression (dose-response curve) using GraphPad Prism v6 (La Jolla, CA).

The immunoreactive fraction of 89Zr-M9346A was determined using the Lindmo assay in HeLa cells.19

In Vivo Tumor Growth Inhibition Studies.

When average tumor volumes were approximately 250–400 mm3, WHIM mice were randomized by tumor volume into 5 treatment groups (6–8 mice/group). Each group received treatment doses of IMGN853 (5 mg/Kg, IV), pemetrexed (200 mg/Kg, IP), IMGN853 (5 mg/Kg, IV) plus pemetrexed (200 mg/Kg, IP), saline (IV or IP), or PTX (10 mg/Kg, IV) on days 1 and 8 (QW×2).20–21 Tumor volumes and animal weights were measured twice a week.

Animal Biodistribution Studies.

Wildtype female C57BL/6 mice (Charles River Laboratory, Wilmington, MA) were used for the biodistribution studies. The average mouse weight was 19.9 g, and the average age was 8 weeks. About 333 kBq (9 μCi) of 89Zr-M9346A (1.1 μg / mouse) in 100 μL saline (APP pharmaceuticals, Schaumburg, IL) was injected via the tail vein. The mice were anesthetized with inhaled isoflurane and re-anesthetized before euthanasia by cervical dislocation at each time point (4 h, 24 h, 48 h, 72 h, and 144 h post injection (p.i.), n = 5 / time point). Organs of interest were collected, weighed, and counted in a Beckman 8000 gamma counter (Beckman, Fullterton, CA). Standards were prepared and measured along with the samples to calculate percentage of the injected dose per gram of tissue (%ID/g).

Radiation Dosimetry.

The animal biodistribution in %ID/g at the various time points were integrated to provide the organ residence times for each harvested organ by numerical integration. No biological excretion was assumed to occur beyond the last measured time point and that radioactivity only decreased due to physical decay. The animal organ residence times were then scaled to human organ weight by the “relative organ mass scaling” method.22 The cumulative urine and feces activity (in percent injected) were plotted as a function of time and an uptake function was fitted to the data (F(t) = A0 (1-exp(-A1 t)). Analytical integration, accounting for radioactive decay, yielded to an excreted residence time of 11.5 h in the feces. Analytical integration of the excreted urine data resulted in a urine residence times of 5.86 h. The filling fraction of 5.9% and the filling half-life of 8.15 h (=ln(2)/0.085h-1) was used in the MIRD voiding model23 along with a voiding interval of 2 h to yield a bladder residence time of 0.054 h in the female animal group. The amount of excreted activity is therefore equal to 17.4 h (or ~15% of the injected activity). The remainder of the body residence time was calculated from the maximum theoretical residence time minus the excreted residence time minus the sum of all residence times measured in the organ above at the exception of blood. This resulted in a residence time associated to the remainder of the body of 52.2 h. The adult female blood volume was assumed to be 3900 mL.24 The errors bars on the measured residence times were determined from the standard deviation of the biodistribution data points. Organ radiation dose and Effective Dose were calculated using the determined residences times and the OLINDA/EXM v1.1 software for the adult female model.

Clearance Studies.

The clearance profile of 89Zr-M9346A was evaluated by measuring the radioactivity in urine and feces samples collected during the study. A group of mice (n = 5 / group) were housed in a metabolism study cage where the urine and feces were separately collected at 4 h, 24 h, 48 h, 72 h, and 144 h p.i. (370 kBq/animal). The gamma counting results were calculated as mean percentage of injected dose (%ID) for the group of mice.

Small Animal PET/CT Imaging.

Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and injected with approximately 2.2 MBq (60 μCi) of 89Zr-M9346A (approximately 8 μg/mouse) in 100 μL of saline via the tail vein. Small animal PET scans were performed on either microPET Focus 220 (Siemens, Malvern, PA) or Inveon PET/CT system (Siemens, Malvern, PA) at 48 h or 72 h p.i. The microPET images were corrected for attenuation, scatter, normalization, and camera dead time and co-registered with CT images. All of the PET scanners were cross-calibrated periodically. The microPET images were reconstructed with the maximum a posteriori (MAP) algorithm and analyzed by Inveon Research Workplace. The tumor uptake was calculated in terms of the standardized uptake value (SUV) of tumor tissue in three-dimensional regions of interest (ROIs) without correction for partial volume effect. For 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging, the mice were fasted for 4 h prior to injection of approximately 7.4 MBq (200 μCi) of 18F-FDG. Small animal PET scans were conducted at 1 h p.i.

Histopathology and Immunohistochemistry.

Tumor serial sections (5 μm thick) were cut from paraformaldehyde-fixed (24 h), paraffin-embedded specimens. The sections were deparaffinized and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. For immunohistochemistry, the sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated through a series of xylenes and graded alcohols before undergoing antigen retrieval pretreatment (10 mM Tris, 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 0.05% polysorbate, pH 9.0, for 10 min). They were incubated in blocking serum for 1 h to prevent nonspecific binding (Vectastain; Vector Laboratories). The sections were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibody (anti-FOLR1, 1:400 in blocking serum; Creative Biolabs). Secondary antibody was applied (Vector Laboratories), and color development was activated by diaminobenzidine to give a brown color. The sections were counterstained with Hematoxylin to reveal the tissue architecture (blue). Digital images of the stained sections were obtained using a scanning light microscope (NanoZoomer; Hamamatsu).

RT-PCR.

RNAs isolated from WHIM tumors were used for real time RT-PCR. Tissue RNA was isolated using TRIzol (Invitrogen) per the manufacturer’s instruction. Reverse transcription reactions used 1 μg of total RNA, random hexamer priming, and Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). Expression of FOLR1 and β-actin were determined using Taqman assays (Invitrogen) and an EcoTM Real-Time PCR System (Illumina) in duplicate in 48-well plates. PCR cycling conditions were as follows: 50 °C for 2 min, 95 °C for 21 sec and 60 °C for 20 sec. β-actin expression was used as a comparator using ΔΔ Ct calculations.

Statistical Analysis.

Prism 5, version 5.04 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA), was used for all statistical analyses. Group variation is described as mean ± SD or SEM. Unpaired two-tailed Student t test was used to compare difference between two groups. Nonparametric one-way ANOVA with the Tukey test was employed to compare multiple groups. The significance level in all tests was P ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

Synthesis and Characterization of 89Zr-M9346A

The anti-FRα antibody M9346A was radiolabeled with 89Zr via established methods with slight modifications (Figure S1A). We selected 89Zr due to its radioactive half-life (t1/2= 3.3 days) close to the biological half-life of IMGN853 (biological half-life = ca. 5 days in mice). First, 89Zr chelator, p-SCN-DFO, was introduced to the M9346A by the formation of a stable thiourea linkage between the primary amine groups of lysine on M9346A and isothiocyanate of the bifunctional chelator p-SCN-DFO. Native mass spectrometry (Native MS) analysis determined up to six DFO moieties per antibody conjugate, and the average number of chelators was calculated to be approximately 2.15 DFO per each M9346A. Then, the resulting conjugate (DFO-M9346A) was radiolabeled with neutralized 89Zr-oxalate. The specific activities of resulting 89Zr-M9346A were 222–296 kBq / μg (6–8 μCi / μg) or 32.6–43.5 GBq / μmol (882–1176 mCi / μmol) with quantitative radiolabeling yield (Figure S1B). FPLC analysis also showed the good radiolabeling efficiency with minimal free 89Zr and less than 10% of antibody aggregation (Figure S1C).

Cell binding Studies of 89Zr-M9346A In Vitro.

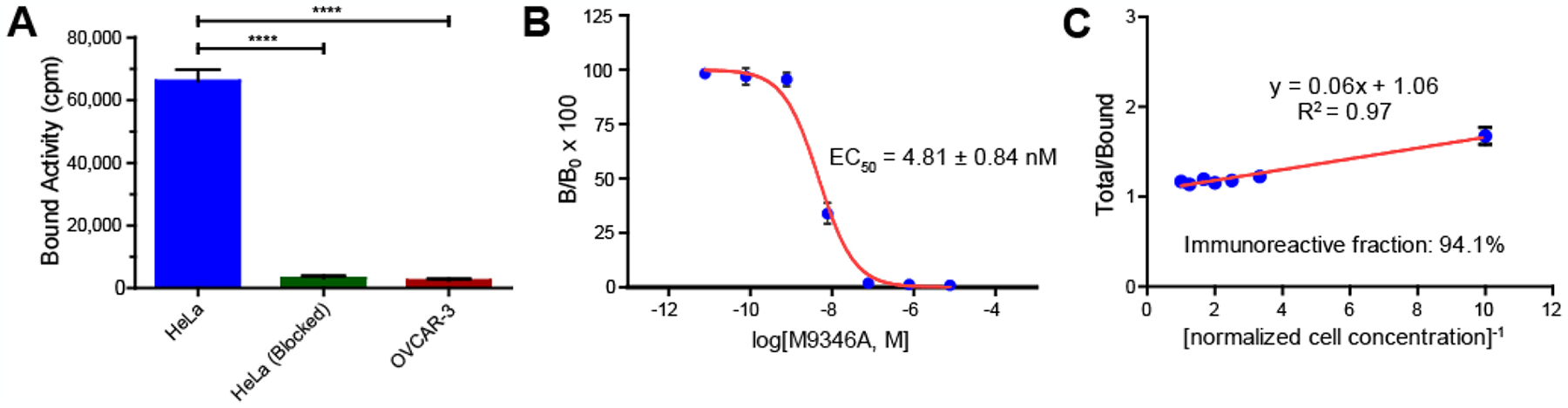

The binding specificity of radiolabeled M9346A to FRα was first examined in vitro by comparing its binding to high FRα expressing cells (HeLa) and low FRα expressing cells (OVCAR-3). As shown in Figure 1A, the binding of 89Zr-M9346A on HeLa cells was 20-fold more than that associated with OVCAR-3 cells (n = 3 / group). With competitive blocking of non-radiolabeled DFO-M9346A (approximately 140-fold excess), the tracer bound to HeLa cells was significantly blocked to a level similar to those acquired in the control OVCAR-3 cells. Competitive binding assay showed that uptake of the 89Zr-M9346A was reduced by increasing concentrations of unlabeled M9346A (Figure 1B). A half maximal effective concentration (EC50) was determined as 4.81 ± 0.84 nM, comparable to other radiolabeled antibodies.25–27 In addition, immunoreactivity of the radiotracer was determined using Lindmo assay in HeLa cells. As shown in Figure 1C, the immunoreactive fraction was approximately 94%, indicating preservation of antigen-binding capability after radiolabeling.

Figure 1.

In vitro cell binding studies demonstrated the binding specificity and immunoreactivity of 89Zr-M9346A to FRα. (A) Cell binding studies in HeLa (FRαhigh) and OVCAR-3 (FRαlow) showed >20-fold higher binding of 89Zr-M9346A on the FRαhigh cell line compared to the FRαlow one. Competitive blocking with non-radioactive DFO-M9346A showed significantly decreased tracer binding. (B) Competitive binding assay of 89Zr-M9346A with non-labeled M9346A revealed the EC50 of 4.81 ± 0.84 nM. (C) The immunoreactive fraction of 89Zr-M9346A was 94.1% determined by Lindmo assay in HeLa cells. [****: p ≤ 0.0001]

Biodistribution, Clearance, and Radiation Dosimetry

Biodistribution and clearance studies were conducted in wildtype female C57BL/6 mice to obtain information on the pharmacokinetics and organ distributions of 89Zr-M9346A. As shown in Figure S2, 89Zr-M9346A displayed high blood retention with 57.7 ± 3.92 %ID/g present in the blood at 4 h p.i. Although it gradually decreased over time, there was still 17.8 ± 1.33 %ID/g in the blood after 6 days p.i., as well as significant retention in other blood pool organs (lung: 8.40 ± 1.19 %ID/g and heart: 6.52 ± 1.88 %ID/g). The blood clearance of 89Zr-M9346A was characterized by a bi-exponential function with a fast biological half-life of 13 h and a slow biological clearance half-life of 454 h, which was similar to the biphasic pharmacokinetics of IMGN853 reported in mice and cynomolgus monkeys.28–29 The accumulations of 89Zr-M9346A in liver and spleen were comparable during the 144 h, ranging from 6 %ID/g to 13 %ID/g. Interestingly, there was a high uptake in bone marrow with 15.8 ± 1.91 %ID/g at 4 h p.i., which gradually decreased to 8.16 ± 1.10 %ID/g at 144 h p.i. Metabolism studies indicated that the tracer was mainly excreted through the hepatobiliary system. At 6 days p.i., the total excretion through feces was approximately 32.6 %ID, which was two times more than that through renal system (10.4%ID).

Based on the animal biodistribution data, radiation exposure was extrapolated to human using the standard MIRD methodology (Figures S3,4 and Tables S1,2). The largest radiation dose is observed in the uterus with values of 0.0792 rad/MBq injected for males and females and the effective doses is calculated at 0.0557 rem/MBq, suggesting approximatively 74 MBq (2 mCi) maximum injection into humans for PET imaging, which is consistent with other 89Zr-labeled antibody tracers.30–31

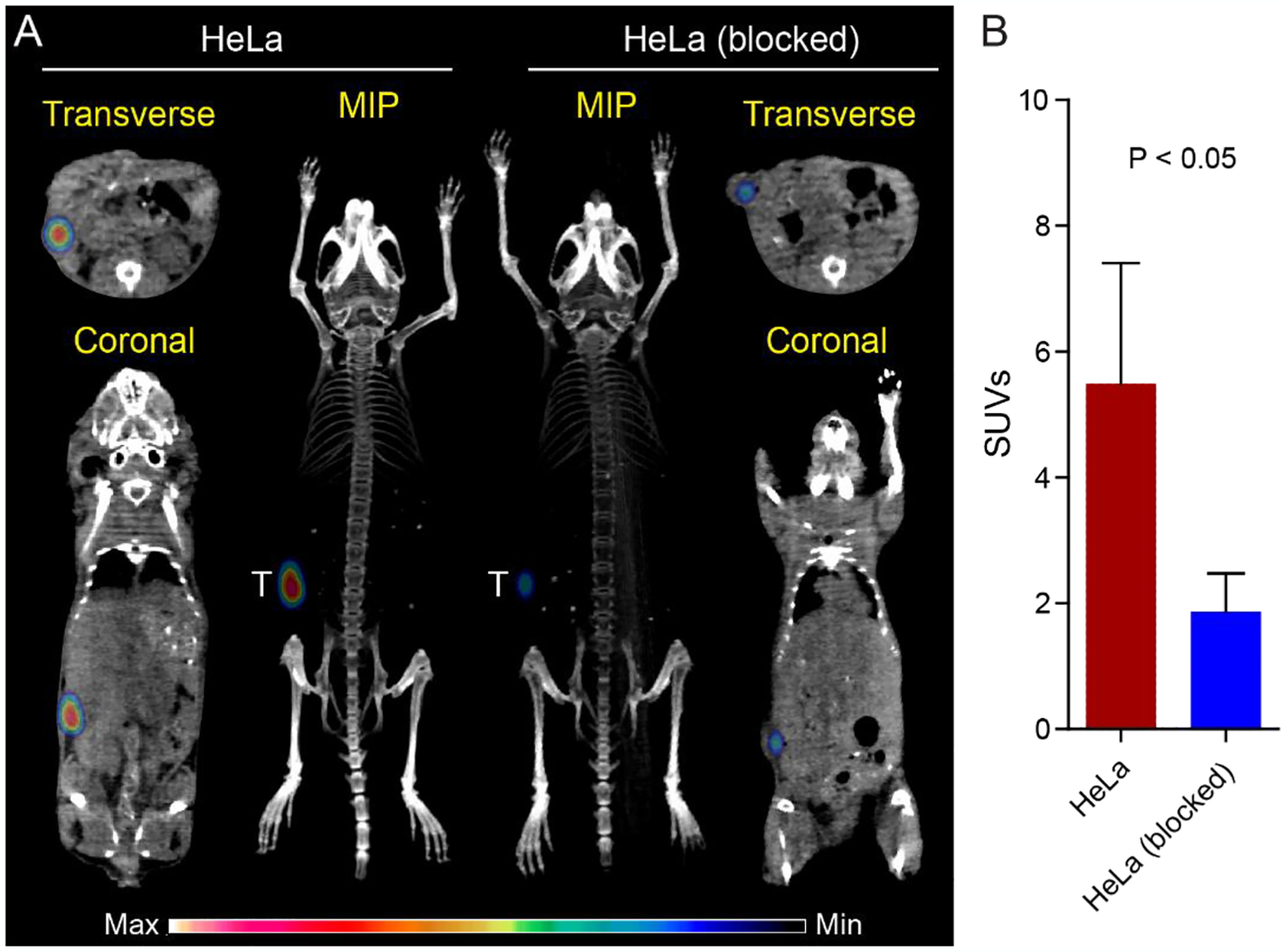

Evaluation of 89Zr-M9346A in the HeLa Xenograft Model

Due to the high expression of FRα, the HeLa xenograft model in female athymic nu/nu mice was employed to determine the imaging specificity of 89Zr-M9346A using PET/CT. As shown in Figure 2A, significant tumor uptake of 89Zr-M9346A was observed in HeLa tumors at 72 h post administration. Through competitive receptor blocking using excess amount of non-radiolabeled M9346A ([M9346A] : [89Zr-M9346A] molar ratio = 100 : 1), the tumor uptake was significantly decreased. Quantitative uptake analysis showed that the tumor uptake of 89Zr-M9346A (SUV = 5.49 ± 1.92) was approximately two times higher (p< 0.05, n=3) than that determined with blockade (SUV = 1.87 ± 0.61, p < 0.05) (Figure 2B), indicating the tumor targeting specificity.

Figure 2.

Quantitative PET/CT imaging of 89Zr-M9346A in the HeLa xenograft model at 72 h p.i. (A) Representative PET/CT images of maximum intensity projection (MIP) reconstituted PET/CT scans (center) and from indicated planes. T: tumor. (B) SUV quantification of 89Zr-M9346A tumor uptake and blocking (SUV: 5.49 ± 1.92 vs. 1.87 ± 0.61). (n = 3 / group)

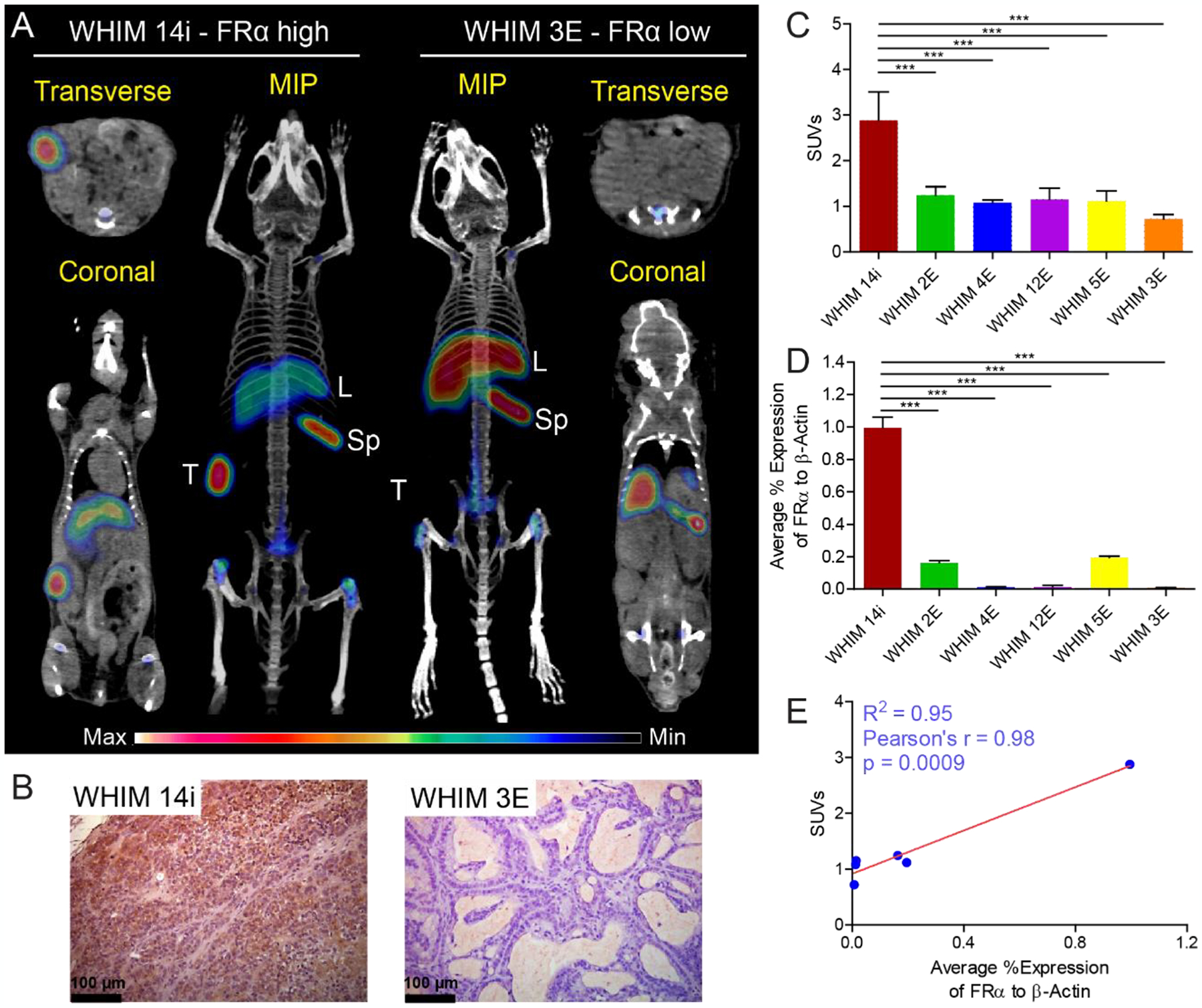

Assessment of FRα Expression in TNBC PDX Mouse Models Using 89Zr-M9346A Immuno-PET

To further assess the translational potential of 89Zr-M9346A in detecting FRα in vivo, TNBC PDX models (WHIM 2E, 3E, 4E, 5E, 12E, and 14i) expressing different levels of FRα were established based on the tumor microarray data (Figure S5). As shown in Figures 3A,C and S6, significant tracer accumulation was determined in the FRαhigh WHIM 14i PDX model while minimal tumor uptake was observed in the FRαlow WHIM 3E PDX model. Quantitative uptake analysis showed that the tumor uptake of 89Zr-M9346A in WHIM 14i (SUV = 2.88 ± 0.63) was approximately four times as much as (p< 0.001, n=3–4/group) the data acquired in WHIM 3E (SUV = 0.72 ± 0.10). Due to the low expression of FRα in other PDX models (Figure 3D), the tumor uptake was comparable among WHIM 2E, 3E, 4E, 5E and 12E but all statistically (p<0.001, n=3–4/group) lower than that of 14i (Figure 3C). Additionally, the tumor uptake of 89Zr-M9346A in these models correlated well with tumor RT-PCR data, indicating the specificity of this PET tracer detecting FRα (Figure 3C,D,E). Immunohistochemical staining showed dense expression of FRα in WHIM 14i tumors while low level of FRα was detected in WHIM 3E, confirming the PET imaging data (Figures 3B and S8). Taken together, the PET imaging in Hela xenografts and 6 TNBC PDX models demonstrated the specificity and sensitivity of 89Zr-M9346A for FRα detection in vivo. Thus, we chose WHIM 14i and 3E as model systems to further assess the potential of 89Zr-M9346A to determine the treatment response.

Figure 3.

Quantitative PET imaging of 89Zr-M9346A in TNBC PDX mouse models at 48 h p.i. (A) Representative PET/CT images of maximum intensity projection (MIP) reconstituted PET/CT scans (center) and from indicated planes. T: tumor, L: liver, Sp: spleen. (B) Immunohistochemical staining of FRα in WHIM 14i and WHIM 3E (FRα: brown). (C) SUV quantification of 89Zr-M9346A tumor uptake (n = 3–4 / group). (D) FRα mRNA expression by RT-PCR (n = 3–6 / group). (E) Correlation curve of SUVs vs FRα mRNA expression.

IMGN853 and Chemotherapy Combination Studies

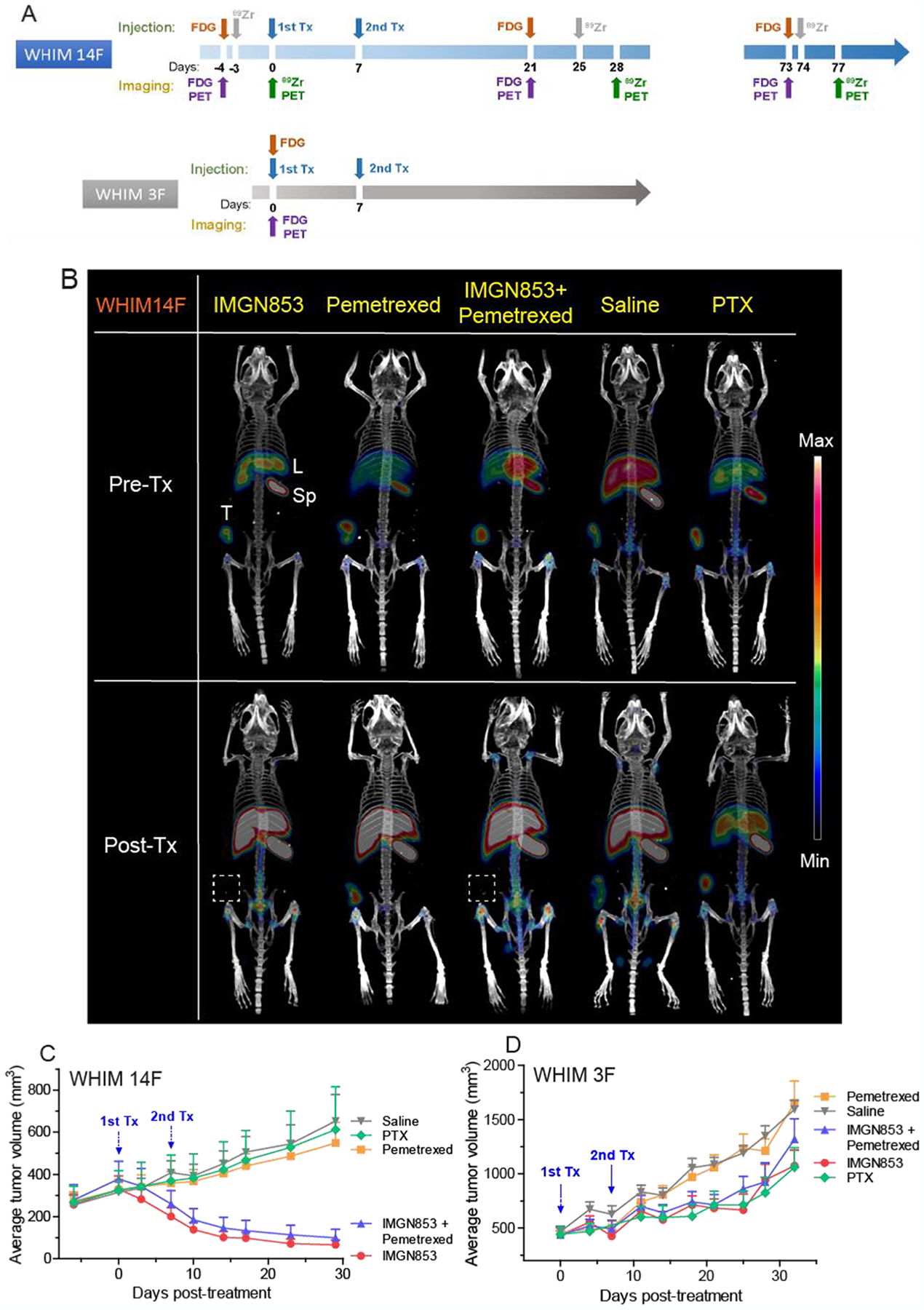

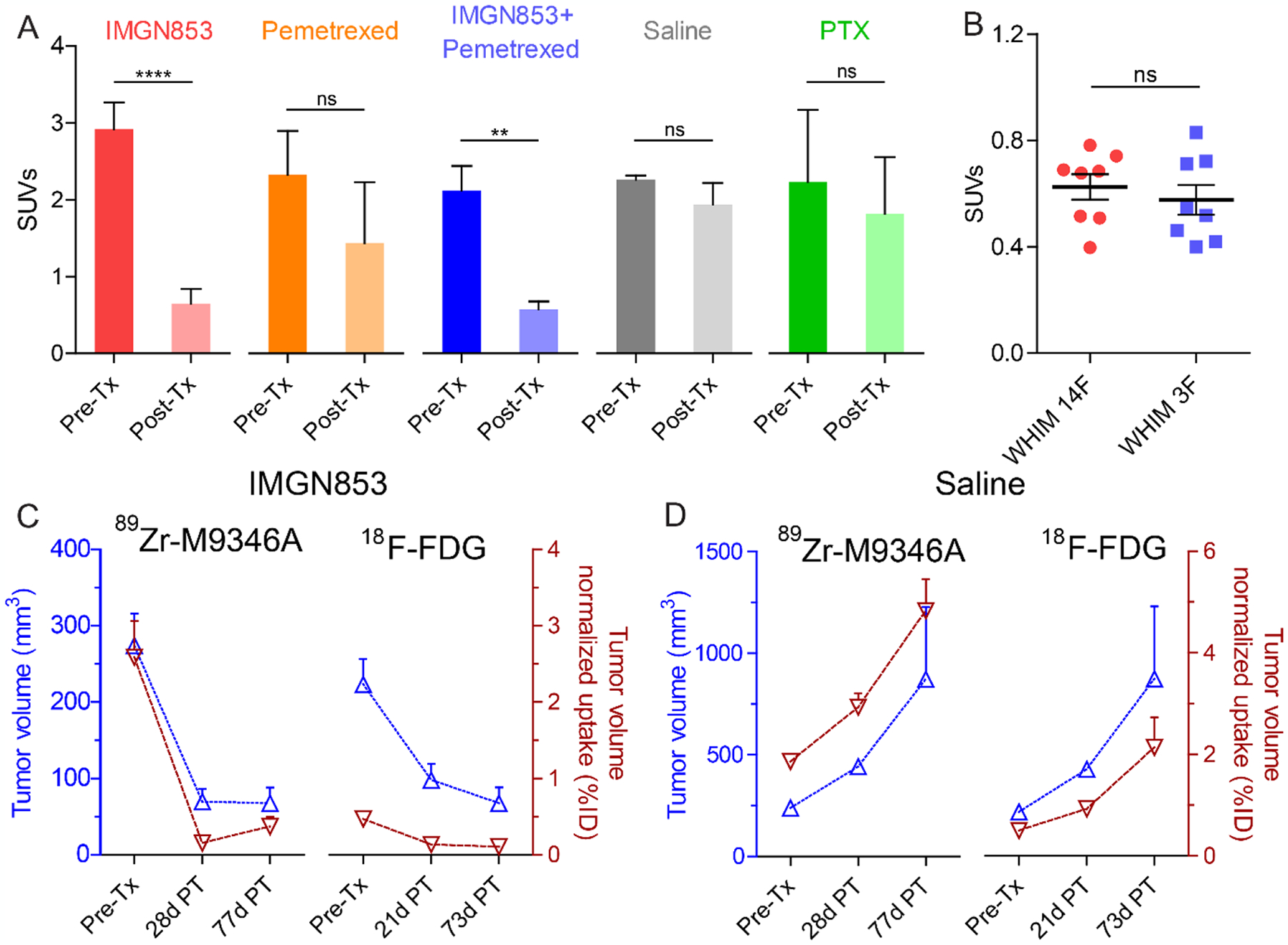

In order to evaluate the potential of immuno-PET as an in vivo companion diagnostic tool to not only prescreen patients for targeted treatment but also to monitor treatment responses to further optimize the therapy, FRα high and low TNBC PDX mice were assessed in treatment studies. Tumor treatment studies were performed in WHIM 14F (FRαhigh) and WHIM 3F (FRαlow) PDX models using IMGN853, Alimta® (pemetrexed for injection), IMGN853 plus pemetrexed, Taxol® (paclitaxel, PTX) and saline (Figure 4A). As shown in Figures 4B,E and S9–13, significant tumor uptake was determined in all WHIM 14F mice with no statistical difference among the 5 groups prior to the treatment. In the treatment study, WHIM 14F tumor sizes were rapidly reduced in the IMGN853 and IMGN853+pemetrexed groups after the first injection of drugs while no treatment response was observed in the other three groups (Figure 4C). After the injection of second treatment, the tumor sizes in the IMGN853 and IMGN853+pemetrexed groups were further decreased to approximately 100 mm3 at day 29, which were approximately 80% smaller than the tumors before the treatments. For the other three groups, the tumor sizes rapidly increased during the study in a similar pattern to approximately 550–650 mm3 at day 29, which were more than 5 times bigger than those in the IMGN853 and IMGN853+pemetrexed groups. Moreover, the difference in tumor volume variation between IMGN853+pemetrexed and pemetrexed alone groups demonstrated the treatment efficacy of IMGN853 in FRα positive TNBC mouse PDX models. Consistent with the variation of tumor volumes, PET imaging with 89Zr-M9346A at day 28 showed nearly 4 times less tumor uptake in both IMGN853 (SUV = 2.89 ± 0.65, p < 0.0001, n = 4) and IMGN853+pemetrexed (SUV = 2.08 ± 0.64, p < 0.01, n = 3) groups compared to the data acquired in the same mice prior to the treatment, suggesting the sensitivity of 89Zr-M9346A to determine FRα positive tumor variation (Figure 5A). Furthermore, the tumor uptake in the two groups were also significantly lower than those obtained in the PTX, saline or pemetrexed treated mice, indicating the potential of 89Zr-M9346A PET as a useful diagnostic tool to prescreen and optimize the IMGN853 targeted treatment.

Figure 4.

Summary of treatment studies. (A) Design of treatment studies. Animals (n = 6–7 / group) received two consecutive weekly doses of IMGN853 (5 mg/Kg, IV), pemetrexed (200 mg/Kg, IP), or PTX (10 mg/Kg, IV) as indicated. (B) Representative MIP reconstituted PET/CT images of 89Zr-M9346A in WHIM14F pre- and post-treatments at 72 h p.i. The variation of average tumor volumes of WHIM 14F (C) and WHIM 3F (D) after treatments. Data are expressed as mean and SEM for each time point.

Figure 5.

PET quantification of treatment studies. (A) Tumor SUVs of 89Zr-M9346A in WHIM 14F pre- and post-treatments at 72 h p.i. (B) Tumor SUVs of 18F-FDG in WHIM14F and WHIM 3F pre-treatments at 1 h p.i. (n = 8 / group) (C) Correlation between tumor volumes of Tx Group 1 (IMGN853) and tumor volume normalized uptake (%ID) of 89Zr-M9346A vs. 18F-FDG PET (n=4). (D) Correlation between tumor volumes of Tx Group 4 (saline) and tumor volume normalized uptake (%ID) of 89Zr-M9346A vs. 18F-FDG PET (n=3).

During the treatment studies of WHIM 14F, 18F-FDG PET was also performed before and at 21-day post treatment. As shown in Figure S14, in contrast to the comparable uptake in Pemetrexed, saline and PTX treated groups before and after the treatment, 18F-FDG tumor uptake in both IMGN853 (SUV = 0.37 ± 0.037, p < 0.01, n = 4) and IMGN853+pemetrexed (SUV = 0.20 ± 0.041, p < 0.001, n = 3) groups at day 21 was approximately 2 times less than the data acquired in the same mice prior to the treatment (Figures S14, S15), confirming the effectiveness of IMGN853 for FRα+ tumor treatment and usefulness of 18F-FDG monitoring treatment response. However, compared to the tumor uptake acquired with 89Zr-M9346A in WHIM 14F and 3F with different levels of FRα+, 18F-FDG PET did not show any difference in tumor uptake between the two models (Figure 5B), which demonstrated the potential of 89Zr-M9346A immuno-PET for FRα+ tumor imaging and pre-screening of patient for IMGN853 treatment. Due to the non-selectivity of 18F-FDG, the quantification in tumors was complicated by the surrounding organs in contrast to 89Zr-M9346A (Figure S15 vs Figures S9, S12), which further highlighted the superiority of immuno-PET.

In WHIM 3F tumor-bearing mice, though same treatments as in WHIM 14F group were applied, the tumor sizes of IMGN853 and IMGN853+pemetrexed treated mice increased from approximately 400 mm3 before treatment to 800–1200 mm3 at day 29 post treatment, confirming the specificity of IMGN853 in treating FRα positive tumors.

The capability of 89Zr-M9346A to track FRα positive tumor volume variations was further explored by extending the studies up to 77 days post treatment in WHIM 14F mice. As shown in Figures 5C,D, in IMGN853 treated mice, tumor volumes did not increase over the 50 days while the saline treated group showed significant tumor growth, suggesting the effectiveness of IMGN853 inhibiting tumor growth. Moreover, in IMGN853 treated group, the tumor volume normalized uptake of 89Zr-M9346A showed closer correlation with tumor volume than that of 18F-FDG while the correlations were comparable in saline treated group, indicating the potential of 89Zr-M9346A to track treatment response in FRα positive tumors to optimize the treatment regimen.

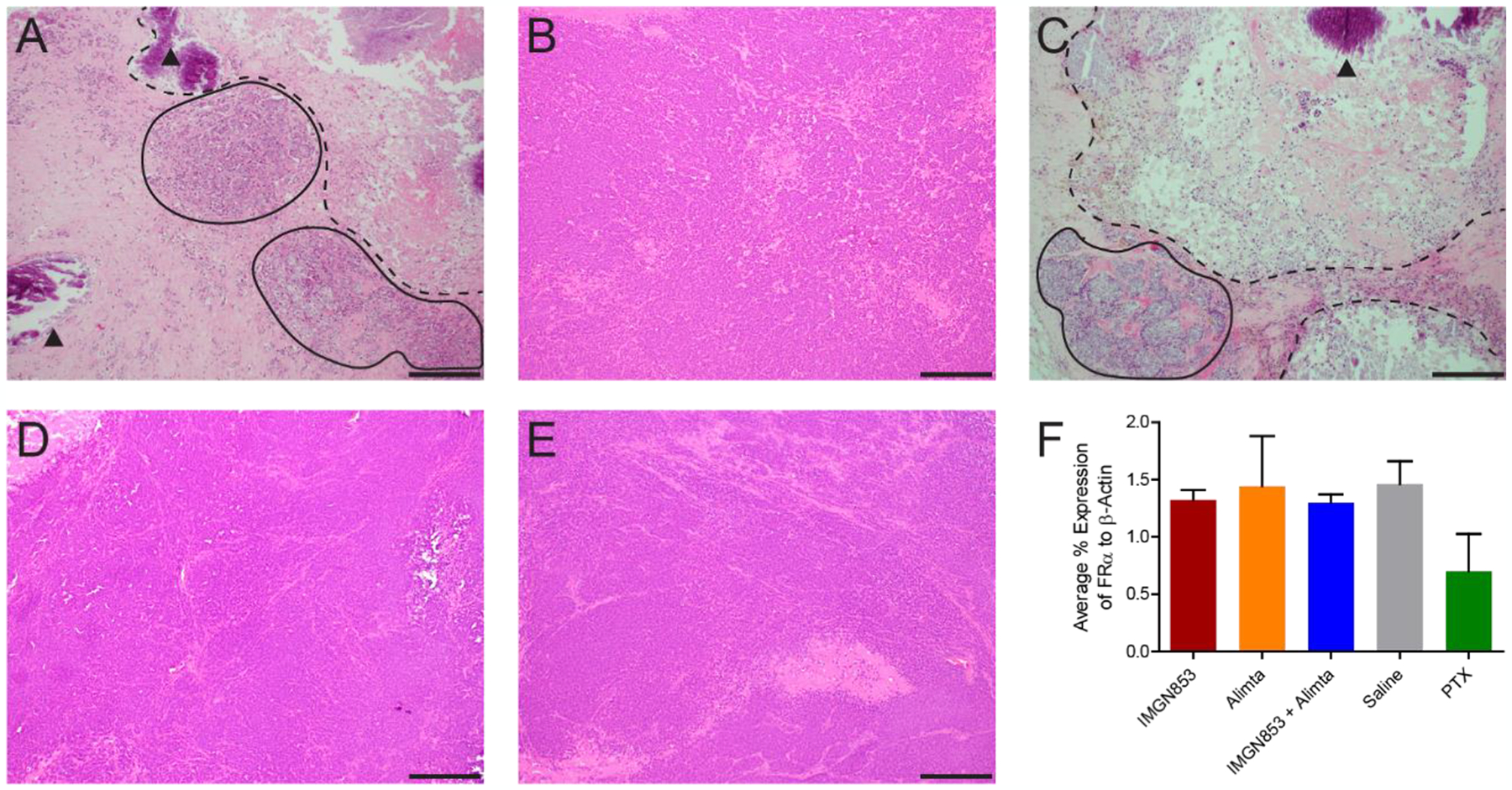

Histopathological Characterization of Treatment Effect in WHIM 14F Tumors

Histopathological examination of WHIM 14F tumors were performed at day 31 to assess the treatment effects. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining revealed IMGN853 treatment (Figure 6A,C) induces extensive tumor necrosis (dashed outlines) associated with areas of microcalcifications (black arrowhead) and scant nests of residual tumor cells (solid outlines), whereas pemetrexed and PTX treatment groups (Figure 6B,D) and saline control group (Figure 6E) showed solid sheets for proliferative tumor cells associated with focal central necrosis (pictures not shown). These results were well corroborated with heterogeneous radioactivity distributions within the tumors in immuno-PET (Figure 5B). Interestingly, RT-PCR analysis of the five groups showed comparable FOLR1 mRNA levels, indicating that the various treatment strategies did not change FRα expression, which is consistent with previous reports.15 The decreased tumor uptake in IMGN853 and IMGN853+pemetrexed groups was mainly due to cell death.

Figure 6.

Representative H&E staining of WHIM 14F tumors after treatments with IMGN853 (A), pemetrexed (B), IMGN853+pemetrexed (C), Saline (D), and PTX (E). Scale bar: 2 mm. (F) FOLR1 mRNA expression measured by RT-PCR

DISCUSSION

Many targeted therapeutics have been developed and approved for clinical use, especially for cancer treatment. In order to fully take advantage of targeted therapeutics, a precise characterization of molecular targets within individual patients is required. In this regard, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommends the co-development of therapeutic products and companion diagnostics. The FDA defines a companion diagnostic as “a medical device, often an in vitro device, which provides information that is essential for the safe and effective use of a corresponding drug or biological product.” Also, the FDA describes that “companion diagnostics can 1) identify patients who are most likely to benefit from a particular therapeutic product; 2) identify patients likely to be at increased risk for serious side effects as a result of treatment with a particular therapeutic product; or 3) monitor response to treatment with a particular therapeutic product for the purpose of adjusting treatment to achieve improved safety or effectiveness.” In this context, an IHC test has been used as an in vitro companion diagnostic for IMGN853 clinical trials.15 While IHC can determine the level of FRα expression, allowing for the identification of patients who would benefit from IMGN853 treatment, this method cannot assess a risk-benefit ratio for each patient. Also, the requirement of multiple biopsies makes it challenging for monitoring treatment response, which limits its use as a companion diagnostic. In addition to the inevitable sampling bias that was discussed in the introduction, IHC results may not associate with the functional activity of the target molecule in vivo.32 Functionally inactive mutants of FRα might still be positive on IHC, but do not interact with M9346A in vivo. Other than receptor expression, drug delivery can also be affected by tumor biology, such as blood flow, perfusion, permeability, and interstitial fluid pressure (IFP), which cannot be evaluated using IHC.33 In this regard, we prepared 89Zr-M9346A, and evaluated the potential of immuno-PET as an in vivo companion diagnostic. Since molecular imaging can visualize biological activities in vivo, allowing for quantification in both molecular and genomic levels,34–35 immuno-PET could potentially provide a clearer understanding of both delivery efficiency and biodistribution/pharmacokinetics of ADC, which are critical to determine a risk-benefit ratio, predict side-effects, and adjust dosage that cannot be evaluated in vitro.31

The first and second qualification of companion diagnostics, as defined by the FDA, can be summarized as the capability to assess the risk-benefit ratios of treatment options for individual patients. We first evaluated whether 89Zr-M9346A immuno-PET could predict treatment benefit by measuring FRα expression. In both clinical and preclinical studies, it has been demonstrated that the treatment benefit of IMGN853 correlates with higher tumor FRα expression levels.11, 16–17 IMGN853 has shown its efficacy in multiple tumor-bearing mouse models, including xenografts (IGROV-1, NCI H2110, END(K)265, and OV-90) and PDXs (LXFA-737, BIO(K)1, and platinum-resistant ovarian cancer).11, 16 In this study, TNBC tumors were selected based on previous data that showed 80% of TNBCs expressed FRα.36–37 Tumor uptake of 89Zr-M9346A was analyzed by SUV quantification in immuno-PET images, which showed good correlation between SUV and FOLR1 mRNA expression by RT-PCR. These results indicated that SUV analysis of immuno-PET imaging can be used to evaluate FRα expression on tumors in vivo.

The in vivo organ accumulation of IMGN853 during treatment cycles in patients may be reasonably represented by the non-invasive spatial/temporal biodistribution profile of 89Zr-M9346A. Similar pharmacokinetics of IMGN853 and 89Zr-M9346A have been demonstrated by comparing blood retention in female athymic nude mice and ex vivo biodistribution in OV-90 xenograft between 131I-radiolabeld IMGN853 and 89Zr-M9346A.38 Although further studies are required to confirm comparable pharmacokinetics of IMGN853 with the biodistribution of 89Zr-M9346A, an unquestionable benefit of immuno-PET is its ability to non-invasively display in vivo pharmacokinetics of the radiotracer. Thus, time-course imaging can also reveal the dynamic variation of FRα in various organs, which is useful to optimize the IMGN853 treatment for maximal efficacy and minimal off-target effect. To reduce undesirable toxicity to these organs, pre- or co-injection of M9346A antibody may be an effective approach to block FRα on non-target organs and further studies are needed to define proper doses without affecting tumor targeting efficiency.

The third qualification of companion diagnostics is the capability of monitoring treatment response. After internalization of FRα with the ADC to the cancer cells, FRα is known to be rapidly recycled to the cell surface.39–41 Also, constant FRα expression regardless of IMGN853 treatment15 makes it an ideal biomarker for both targeted delivery of the drug and monitoring treatment response. As we expected, our treatment studies showed that FRα expression determined by immuno-PET positively correlated to the treatment response of anti-FRα ADC, IMGN853. Comparison between 18F-FDG PET and immuno-PET revealed that 89Zr-M9346A is a superior radiotracer to monitor the treatment response of IMGN853. This is because immuno-PET enables the monitoring of FRα positive tumors via FRα specific interaction compared to FRα non-specific 18F-FDG PET which measures the rate of glucose metabolism. In metastatic setting, immuno-PET could assess FRα positivity within the lesions for potentially targeted treatment although the capability of 89Zr-M9346A for early detection of metastasis needs further investigation. Based on the correlation between tumor volume and %ID of 18F-FDG and 89Zr-M9346A, immuno-PET has potential to be a complementary imaging option to 18F-FDG PET for future clinical application. During IMGN853 treatment, FRα could be downregulated in tumors due to resistance.42 The non-invasive determination of FRα expression in the course of IMGN853 therapy will be useful to monitor the therapeutic efficacy in real time and optimize the treatment strategy to improve patient outcomes.

Although our results indicated that immuno-PET is a promising in vivo companion diagnostic for clinical trials of IMGN853, more studies are required to make this tool serviceable in both clinic and clinical trials. In order to determine eligibility for IMGN853 treatment, the minimum SUV (or %ID/g or %ID) has to be determined. Also, comparative studies between current standard protocol (FRα staining score via IHC) and SUV (or %ID/g or %ID) of immuno-PET are desirable to set enrollment criteria, predict treatment response, and determine prognosis. After initially pre-screening with IHC, immuno-PET can be employed to further confirm the eligibility of patients for clinical trials. Being able to minimize unnecessary treatment and improve a clinical trial design could rationalize the high cost of immuno-PET imaging. In this context, further studies will be necessary to develop a better scoring system using immuno-PET imaging to categorize FRα expression, which is associated with the outcome of the treatment. Biodistribution and pharmacokinetics of 89Zr-M9346A and IMGN853 need to be more thoroughly compared and assessed to determine the appropriate dosage for each patient. Different physicochemical properties between the 89Zr-DFO- and maytansinoid DM4-conjugated M9346A could lead to distinct in vivo behaviors. Even though a preliminary comparison study is already published,38 similar studies in different animal models including non-human primates will provide a better understanding. In addition, it would be beneficial to conduct further treatment studies with different study design that focuses more on the individual difference of FRα expression and treatment efficacy in each PDX or xenograft. Tumor uptake analyzed by immuno-PET could help predict treatment response by determining in vivo accessibility of radiotracer to tumors, revealing the in vivo delivery efficiency of IMGN853.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, we developed a FRα targeted PET tracer of 89Zr-M9346A and assessed its imaging sensitivity and specificity in multiple TNBC PDX tumors. Moreover, we compared the capability of 89Zr-M9346A monitoring treatment response under various therapeutic settings. These results clearly demonstrated the potential of 89Zr-M9346A immuno-PET as a complementary in vivo companion diagnostic to currently used in vitro immunohistochemical methods for clinical trials of IMGN853. Immuno-PET will be applicable to patient screening in clinical trials since it can non-invasively evaluate both FRα expression and biodistribution/pharmacokinetics of ADC. Although our study has some limitations such as radiation exposure, low spatial resolution of PET, access to cyclotron facility, and cost of radiotracer preparation, we envision that precise phenotyping of patients via 89Zr-M9346A immuno-PET will improve not only design of clinical trials but also patient-tailored care in future clinical settings.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was approved and funded in part by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Oncology Research Program from general research support provided by ImmunoGen, Inc. The animal imaging and radiation dosimetry work were performed at the Siteman Cancer Center (P30CA091842) Small Animal Imaging Core and Washington University Small Animal Imaging PET/CT Facility. We thank Dr. Weidong Cui and Dr. Liuqing (Rachel) Shi for native MS analysis. This study made use of the NIH / NIGMS Biomedical Mass Spectrometry Resource at Washington University in St. Louis, MO, which is supported by National Institutes of Health \ National Institute of General Medical Sciences Grant # 8P41GM103422.

ABBREVIATIONS

- FRα

folate receptor α

- IMGN853

mirvetuximab soravtansine

- 89Zr

zirconium-89

- immuno-PET

immuno-positron emission tomography

- TNBC

triple negative breast cancer

- PDX

patient-derived xenograft

- ADC

antibody-drug conjugate

- DFO

deferoxamine

Footnotes

Supporting Information. The Supporting Information file is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI:

Synthetic scheme of 89Zr-M9346A and characterization (Figure S1); Radiation dosimetry data; Biodistribution and clearance of 89Zr-M9346A (Figure S2); Urine and feces excretion data (Figure S3); Blood clearance time-activity curve (Figure S4); Organ residence times extrapolated to human (Table S1); Extrapolated human radiation dose estimates (Table S2); TNBC Tumor microarray data (Figure S5); Representative MIP reconstituted PET/CT images of 89Zr-M9346A in TNBC PDX mouse models (Figure S6); 89Zr-M9346A uptake ratios (tumor/blood and tumor/muscle) in 6 TNBC PDX mouse models (Figure S7); Immunohistochemical staining of FRα in 6 TNBC PDXs (Figure S8); Representative PET/CT images of 89Zr-M9346A in 5 treatment groups (Figure S9–S13); SUV comparison of 18F-FDG in WHIM 14F of each treatment group (Figure S14); Representative PET/CT images of 18F-FDG in WHIM14F (Figure S15)

REFERENCES

- 1.Peck RW, Precision Medicine Is Not Just Genomics: The Right Dose for Every Patient. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol 2018, 58, 105–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mendelsohn J, Personalizing Oncology: Perspectives and Prospects. J. Clin. Oncol 2013, 31, 1904–1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brock A; Huang S, Precision Oncology: Between Vaguely Right and Precisely Wrong. Cancer Res 2017, 77, 6473–6479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.European Society of, R., Medical Imaging in Personalised Medicine: A White Paper of the Research Committee of the European Society of Radiology (Esr). Insights Imaging 2015, 6, 141–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scott AM; Wolchok JD; Old LJ, Antibody Therapy of Cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2012, 12, 278–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weiner GJ, Building Better Monoclonal Antibody-Based Therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2015, 15, 361–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Larson SM; Carrasquillo JA; Cheung N-KV; Press OW, Radioimmunotherapy of Human Tumours. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2015, 15, 347–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lambert JM; Berkenblit A, Antibody–Drug Conjugates for Cancer Treatment. Annu. Rev. Med 2018, 69, 191–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beck A; Goetsch L; Dumontet C; Corvaïa N, Strategies and Challenges for the Next Generation of Antibody–Drug Conjugates. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 2017, 16, 315–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nasiri H; Valedkarimi Z; Aghebati-Maleki L; Majidi J, Antibody-Drug Conjugates: Promising and Efficient Tools for Targeted Cancer Therapy. J. Cell. Physiol 2018, 233, 6441–6457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ab O; Whiteman KR; Bartle LM; Sun X; Singh R; Tavares D; LaBelle A; Payne G; Lutz RJ; Pinkas J; Goldmacher VS; Chittenden T; Lambert JM, IMGN853, a Folate Receptor-A (FRα)–Targeting Antibody–Drug Conjugate, Exhibits Potent Targeted Antitumor Activity against FRα-Expressing Tumors. Mol. Cancer Ther 2015, 14, 1605–1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blum RH; Wittenberg BK; Canellos GP; Mayer RJ; Skarin AT; Henderson IC; Parker LM; Frei EI, A Therapeutic Trial of Maytansine. Am. J. Clin. Oncol 1978, 1, 113–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moore KN; Martin LP; O’Malley DM; Matulonis UA; Konner JA; Perez RP; Bauer TM; Ruiz-Soto R; Birrer MJ, Safety and Activity of Mirvetuximab Soravtansine (IMGN853), a Folate Receptor Alpha–Targeting Antibody–Drug Conjugate, in Platinum-Resistant Ovarian, Fallopian Tube, or Primary Peritoneal Cancer: A Phase I Expansion Study. J. Clin. Oncol 2017, 35, 1112–1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moore KN; Borghaei H; O’Malley DM; Jeong W; Seward SM; Bauer TM; Perez RP; Matulonis UA; Running KL; Zhang X; Ponte JF; Ruiz-Soto R; Birrer MJ, Phase 1 Dose-Escalation Study of Mirvetuximab Soravtansine (IMGN853), a Folate Receptor A-Targeting Antibody-Drug Conjugate, in Patients with Solid Tumors. Cancer 2017, 123, 3080–3087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin LP; Konner JA; Moore KN; Seward SM; Matulonis UA; Perez RP; Su Y; Berkenblit A; Ruiz-Soto R; Birrer MJ, Characterization of Folate Receptor Alpha (FRα) Expression in Archival Tumor and Biopsy Samples from Relapsed Epithelial Ovarian Cancer Patients: A Phase I Expansion Study of the Frα-Targeting Antibody-Drug Conjugate Mirvetuximab Soravtansine. Gynecol. Oncol 2017, 147, 402–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Altwerger G; Bonazzoli E; Bellone S; Egawa-Takata T; Menderes G; Pettinella F; Bianchi A; Riccio F; Feinberg J; Zammataro L; Han C; Yadav G; Dugan K; Morneault A; Ponte JF; Buza N; Hui P; Wong S; Litkouhi B; Ratner E; Silasi D-A; Huang GS; Azodi M; Schwartz PE; Santin AD, In Vitro and in Vivo Activity of IMGN853, an Antibody–Drug Conjugate Targeting Folate Receptor Alpha Linked to DM4, in Biologically Aggressive Endometrial Cancers. Mol. Cancer Ther 2018, 17, 1003–1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ponte JF; Ab O; Lanieri L; Lee J; Coccia J; Bartle LM; Themeles M; Zhou Y; Pinkas J; Ruiz-Soto R, Mirvetuximab Soravtansine (IMGN853), a Folate Receptor Alpha-Targeting Antibody-Drug Conjugate, Potentiates the Activity of Standard of Care Therapeutics in Ovarian Cancer Models. Neoplasia 2016, 18, 775–784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vosjan MJWD; Perk LR; Visser GWM; Budde M; Jurek P; Kiefer GE; van Dongen GAMS, Conjugation and Radiolabeling of Monoclonal Antibodies with Zirconium-89 for Pet Imaging Using the Bifunctional Chelate P-Isothiocyanatobenzyl-Desferrioxamine. Nat. Protoc 2010, 5, 739–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lindmo T; Boven E; Cuttitta F; Fedorko J; Bunn PA, Determination of the Immunoreactive Function of Radiolabeled Monoclonal Antibodies by Linear Extrapolation to Binding at Infinite Antigen Excess. J. Immunol. Methods 1984, 72, 77–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morfouace M; Shelat A; Jacus M; Freeman BB; Turner D; Robinson S; Zindy F; Wang Y-D; Finkelstein D; Ayrault O; Bihannic L; Puget S; Li X-N; Olson JM; Robinson GW; Guy RK; Stewart CF; Gajjar A; Roussel MF, Pemetrexed and Gemcitabine as Combination Therapy for the Treatment of Group3 Medulloblastoma. Cancer Cell 2014, 25, 516–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ishikura N; Yanagisawa M; Noguchi-Sasaki M; Iwai T; Yorozu K; Kurasawa M; Sugimoto M; Yamamoto K, Importance of Bevacizumab Maintenance Following Combination Chemotherapy in Human Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer Xenograft Models. Anticancer Res 2017, 37, 623–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stabin MG; Siegel JA, Physical Models and Dose Factors for Use in Internal Dose Assessment. Health Phys 2003, 85, 294–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomas SR; Stabin MG; Chen CT; Samaratunga RC, Mird Pamphlet No. 14 Revised: A Dynamic Urinary Bladder Model for Radiation Dose Calculations. Task Group of the Mird Committee, Society of Nuclear Medicine. J. Nucl. Med 1999, 40, 102s–123s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.ICRP, Radiation Dose to Patients from Radiopharmaceuticals. Addendum 3 to ICRP Publication 53. Icrp Publication 106. Approved by the Commission in October 2007. Ann. ICRP 2008, 38, 1–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marquez BV; Ikotun OF; Zheleznyak A; Wright B; Hari-Raj A; Pierce RA; Lapi SE, Evaluation of 89Zr-Pertuzumab in Breast Cancer Xenografts. Mol. Pharm 2014, 11, 3988–3995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheal SM; Punzalan B; Doran MG; Evans MJ; Osborne JR; Lewis JS; Zanzonico P; Larson SM, Pairwise Comparison of 89Zr- and 124I-Labeled Cg250 Based on Positron Emission Tomography Imaging and Nonlinear Immunokinetic Modeling: In Vivo Carbonic Anhydrase Ix Receptor Binding and Internalization in Mouse Xenografts of Clear-Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2014, 41, 985–994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharma SK; Pourat J; Abdel-Atti D; Carlin SD; Piersigilli A; Bankovich AJ; Gardner EE; Hamdy O; Isse K; Bheddah S; Sandoval J; Cunanan KM; Johansen EB; Allaj V; Sisodiya V; Liu D; Zeglis BM; Rudin CM; Dylla SJ; Poirier JT; Lewis JS, Noninvasive Interrogation of DLL3 Expression in Metastatic Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cancer Res 2017, 77, 3931–3941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gunderson C; Moore K, Mirvetuximab Soravtansine: FRα-Targeting ADC Treatment of Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. Drugs Future 2016, 41, 539–545. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moore KN; Martin LP; O’Malley DM; Matulonis UA; Konner JA; Vergote I; Ponte JF; Birrer MJ, A Review of Mirvetuximab Soravtansine in the Treatment of Platinum-Resistant Ovarian Cancer. Future Oncol 2018, 14, 123–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laforest R; Lapi SE; Oyama R; Bose R; Tabchy A; Marquez-Nostra BV; Burkemper J; Wright BD; Frye J; Frye S; Siegel BA; Dehdashti F, [(89)Zr]Trastuzumab: Evaluation of Radiation Dosimetry, Safety, and Optimal Imaging Parameters in Women with Her2-Positive Breast Cancer. Mol. Imaging Biol 2016, 18, 952–959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deri MA; Zeglis BM; Francesconi LC; Lewis JS, Pet Imaging with 89zr: From Radiochemistry to the Clinic. Nucl. Med. Biol 2013, 40, 3–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elliott S; Sinclair A; Collins H; Rice L; Jelkmann W, Progress in Detecting Cell-Surface Protein Receptors: The Erythropoietin Receptor Example. Ann. Hematol 2014, 93, 181–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ernsting MJ; Murakami M; Roy A; Li S-D, Factors Controlling the Pharmacokinetics, Biodistribution and Intratumoral Penetration of Nanoparticles. J. Control. Release 2013, 172, 782–794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Puranik AD; Kulkarni HR; Baum RP, Companion Diagnostics and Molecular Imaging. Cancer J 2015, 21, 213–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anderson CJ; Lewis JS, Current Status and Future Challenges for Molecular Imaging. Philos. Trans. Royal Soc. A 2017, 375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang Z; Wang J; Tacha DE; Li P; Bremer RE; Chen H; Wei B; Xiao X; Da J; Skinner K; Hicks DG; Bu H; Tang P, Folate Receptor A Associated with Triple-Negative Breast Cancer and Poor Prognosis. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med 2014, 138, 890–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Necela BM; Crozier JA; Andorfer CA; Lewis-Tuffin L; Kachergus JM; Geiger XJ; Kalari KR; Serie DJ; Sun Z; Moreno-Aspitia A; O’Shannessy DJ; Maltzman JD; McCullough AE; Pockaj BA; Cunliffe HE; Ballman KV; Thompson EA; Perez EA, Folate Receptor-Alpha (FOLR1) Expression and Function in Triple Negative Tumors. PloS one 2015, 10, e0122209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brand C; Sadique A; Houghton JL; Gangangari K; Ponte JF; Lewis JS; Pillarsetty NVK; Konner JA; Reiner T, Leveraging Pet to Image Folate Receptor A Therapy of an Antibody-Drug Conjugate. EJNMMI Res 2018, 8, 87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ledermann JA; Canevari S; Thigpen T, Targeting the Folate Receptor: Diagnostic and Therapeutic Approaches to Personalize Cancer Treatments. Ann. Oncol 2015, 26, 2034–2043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sega EI; Low PS, Tumor Detection Using Folate Receptor-Targeted Imaging Agents. Cancer Metastasis Rev 2008, 27, 655–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luyckx M; Votino R; Squifflet J-L; Baurain J-F, Profile of Vintafolide (EC145) and Its Use in the Treatment of Platinum-Resistant Ovarian Cancer. Int. J. Womens Health 2014, 6, 351–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guertin AD; O’Neil J; Stoeck A; Reddy JA; Cristescu R; Haines BB; Hinton MC; Dorton R; Bloomfield A; Nelson M; Vetzel M; Lejnine S; Nebozhyn M; Zhang T; Loboda A; Picard KL; Schmidt EV; Dussault I; Leamon CP, High Levels of Expression of P-Glycoprotein/Multidrug Resistance Protein Result in Resistance to Vintafolide. Mol. Cancer Ther 2016, 15, 1998–2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.