Abstract

Background:

Hypercholesterolemia (HCL) is common among Emergency Department (ED) patients with chest pain but is typically not addressed in this setting. This study aims to determine whether a missed opportunity for Emergency Department Observation Unit (EDOU) HCL testing and treatment exists.

Methods:

We conducted a retrospective observational cohort study of patients ≥18 years old evaluated for chest pain in an EDOU from 3/1/2019-2/28/2020. The electronic health record was used to determine demographics and if HCL testing or treatment occurred. HCL was defined by self-report or clinician diagnosis. Proportions of patients receiving HCL testing or treatment at 1-year following their ED visit were calculated. HCL testing and treatment rates at 1-year were compared between white vs. non-white and male vs. female patients using multivariable logistic regression models including age, sex, and race..

Results:

Among 649 EDOU patients with chest pain, 55.8% (362/649) had known HCL. Among patients without known HCL, 5.9% (17/287, 95%CI 3.5-9.3%) had a lipid panel during their index ED/EDOU visit and 26.5% (76/287, 95%CI 21.5-32.0%) had a lipid panel within 1-year of their initial ED/EDOU visit. Among patients with known or newly diagnosed HCL, 54.0% (229/424, 95%CI 49.1-58.8%) were on treatment within 1-year. After adjustment, testing rates were similar among white vs. non-white patients (aOR 0.71, 95%CI 0.37-1.38) and men vs. women (aOR 1.32, 95%CI 0.69-2.57). Treatment rates were similar among white vs. non-white (aOR 0.74, 95%CI 0.53-1.03) and male vs. female (aOR 1.08, 95%CI 0.77-1.51) patients.

Conclusions:

Few patients were evaluated for HCL in the ED/EDOU or outpatient setting after their ED/EDOU encounter and only 54% of patients with HCL were on treatment during the 1-year follow-up period after the index ED/EDOU visit. These findings suggest a missed opportunity to reduce cardiovascular disease risk exists by evaluating and treating HCL in the ED or EDOU.

Keywords: hypercholesteremia, hyperlipidemia, prevention, emergency medicine, observation medicine, chest pain

INTRODUCTION

Hypercholesterolemia (HCL) affects nearly 30% of the United States (US) population and is a major risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), the composite of obstructive coronary artery disease, stroke, transient ischemic attack, and peripheral artery disease.1-3 Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) is the principle driver of ASCVD and is the primary therapeutic target for mitigating ASCVD risk.2,4-8 Traditionally, screening and treatment for HCL has been initiated in primary care or cardiology clinic settings but not in the Emergency Department (ED) or Emergency Department Observation Unit (EDOU).

Chest pain, the most common symptomatic manifestation of ASCVD, is responsible for over 6.5 million Emergency Department (ED) visits in the US each year.9-12 While these patients are being evaluated in the ED or EDOU, there may be an opportunity to reduce ASCVD risk by testing for HCL and initiating lipid lowering therapy.13-15 Currently, at the time of ED discharge, patients with acute chest pain are typically instructed to follow-up with their primary care physician or cardiologist with the assumption that lipid testing and therapy will be provided in the outpatient setting. However, it is unclear whether these patients ultimately receive HCL care in the outpatient setting. Recognizing this potential gap in care, the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM) and the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) recommend that emergency providers offer preventive care for cardiovascular disease.16-19 Despite these recommendations, it remains exceptionally uncommon for ED or EDOU providers to test for or treat HCL.20-22

The goal of this study is to determine if current ED and EDOU care practices for patients with chest pain miss a key opportunity to evaluate for and treat HCL. To address this key evidence gap, this study aims to determine the proportion of patients who receive HCL testing and treatment in the ED or EDOU and in the outpatient setting within 1-year of EDOU discharge. Additionally, because non-white and female patients are historically less likely to receive preventive cardiovascular care,23-26 a secondary objective was to determine if HCL testing and treatment rates vary by race or sex.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a retrospective observational cohort study of patients being evaluated for acute chest pain in the ED and EDOU of Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist from 3/1/2019 to 2/28/2020. The Wake Forest University Health Sciences Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol and granted a waiver of informed consent. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines helped direct the research and reporting processes.27

Study Setting and Population

Patients ≥18 years old being evaluated for acute chest pain and possible acute coronary syndrome in the EDOU at Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist were included. The Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist ED is located in the Piedmont Triad area of North Carolina and is staffed by board-certified or board-eligible emergency physicians 24 hours per day. It has an annual volume of approximately 110,000 encounters. To be eligible for EDOU care, the ED attending had to place the patient on the EDOU Chest Pain Protocol (Supplemental Appendix 1). Patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, hemodynamic instability (heart rate <40 or >120 beats per minute, systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg, or SpO2% <90% on room air or normal home oxygen flow rate) at any time during their ED encounter, high sensitivity cardiac troponin I (Beckman Coulter; Brea, CA) ≥100 ng/L, or trauma were not eligible for EDOU care. This EDOU is a protocol-driven (Type 1) observation unit. The EDOU is managed by emergency medicine physician assistants and nurse practitioners who are supervised by board-certified or board eligible emergency physicians. Patients undergo serial troponin testing, telemetry monitoring, and when appropriate, stress testing or coronary computed tomography angiography.

Data Collection and Variables

Index ED and EDOU encounter data and outpatient clinic follow-up data through 1-year of the index visit were abstracted from the electronic health record (EHR; Clarity-Epic Systems Corporation, Verona, WI) by trained data abstractors. HCL was defined by patient self-report to the treating ED clinical team or by clinician diagnosis either in the ED or during the 1-year follow-up period. Self-reported HCL was captured in the EHR as a structured risk stratification variable in the ED. Lipid panel measurements, including LDL-C, non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (non-HDL-C), total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and triglycerides, were extracted from the EHR. Data were entered into a Research Electronic Data CAPture (REDCap) database. Best practice guidelines for the chart review were used, including having trained data extractors, a data dictionary, digital extraction forms within REDCap, having regular performance review by the principal investigator (PI), and a random sample of entries reviewed by the PI.28,29 Training consisted of in-person instruction with the PI, where actual encounters were reviewed to ensure familiarity with where and how to access the relevant data in the EHR and how to input the data into REDCap.

Outcomes

Study outcomes were: 1) the proportion of patients with and without known HCL who were evaluated with a lipid panel in the ED/EDOU or in an outpatient clinic during the 1-year follow-up period and 2) the proportion of patients with known or newly diagnosed HCL who were on a lipid lowering medication in the ED/EDOU or at any time during the 1-year follow-up period. We evaluated the missed opportunity for EDOU-based HCL testing among all patients and among the subgroups of patients with and without known HCL. A missed testing opportunity was defined as a patient who did not receive a lipid panel during the ED/EDOU encounter or the 1-year outpatient follow-up period. We included patients with known HCL who did not receive a lipid panel in the ED/EDOU or 1-year follow-up period for this missed opportunity because response to therapy or medication compliance may be unknown. Similarly, a missed opportunity for EDOU-initiated HCL therapy was defined as a patient with known or newly diagnosed HCL who failed to receive any HCL therapy in the ED/EDOU or the 1-year outpatient period. Additional outcomes were LDL-C, non-HDL-C, total cholesterol, HDL-C, and triglycerides measures among patients with lipid panel testing. Known HCL was defined as HCL that was diagnosed before their index ED/EDOU encounter based on patient self-report or medical record review. Newly diagnosed HCL included patients with HCL diagnosed in the ED/EDOU or the 1-year outpatient follow-up period. Therapy for HCL was defined as being on any statin medication, ezetimibe, or PCSK9 inhibitor.

Statistical Analysis

Counts, percentages, and means with standard deviations were used to describe the study population. Rates of HCL testing and therapy during the ED and EDOU encounter, the 1-year follow-up period inclusive of the ED and EDOU encounter, and the missed opportunities for testing and therapy were calculated and reported with exact 95% confidence intervals (95%CI). Lipid panel results were reported with means and standard deviations or medians and interquartile ranges, as appropriate. The two-sample t-test (with the corresponding 95%CI for the difference) or the Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test (with the corresponding Hodges-Lehmann estimator and 95%CI) was used to compare lipid measures among patients receiving HCL therapy at 1-year to those who were not. Rates of HCL testing among white vs. non-white and male vs. female patients were compared at 1-year using Fisher’s exact tests. Similarly, HCL therapy rates among patients with a diagnosis of HCL at 1-year were also compared among these race and sex subgroups with Fisher’s exact test. To further evaluate the association of race and sex with receiving HCL testing and therapy, multivariable logistic regression was performed. Multivariable models included age (continuous), race (white vs. non-white), and sex (male vs. female). Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (aOR) with corresponding 95%CIs were calculated.

RESULTS

Among the 649 EDOU patients, 59.5% (386/649) were female and 43.8% (284/649) were non-white with a mean age of 59.8±12.3 years. At the time of the initial EDOU visit, 55.8% (362/649) had known HCL. During the 1-year follow-up period, 69.7% (452/649) were evaluated in an outpatient clinic for any reason. Table 1 describes the demographics of patients with and without known HCL at the time of the EDOU encounter.

Table 1.

Cohort characteristics.

| Patient Characteristics | No Known HCL n=287, n (%) |

Known HCL n=362, n (%) |

Total n=649, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean± SD) (years) | 57.5 (12.9) | 61.6 (11.6) | 59.8 (12.3) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 166 (57.8) | 220 (60.8) | 386 (59.5) |

| Race | |||

| White | 154 (53.7) | 211 (58.3) | 365 (56.2) |

| Non-white | 133 (46.3) | 151 (41.7) | 284 (43.8) |

| Black | 104 (36.2) | 120 (33.2) | 224 (34.1) |

| Other | 29 (10.1) | 31 (8.6) | 60 (9.2) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 22 (7.7) | 21 (5.8) | 43 (6.6) |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) | 136 (47.4) | 209 (57.7) | 345 (53.2) |

| Diabetes | 58 (20.2) | 145 (40.1) | 203 (31.3) |

| Hypertension | 191 (66.6) | 308 (85.1) | 499 (76.9) |

| Known CAD | 20 (7.0) | 61 (75.3) | 81 (12.5) |

| Stroke | 28 (9.8) | 40 (11.1) | 68 (10.5) |

SD – standard deviation, BMI – body mass index, CAD – coronary artery disease

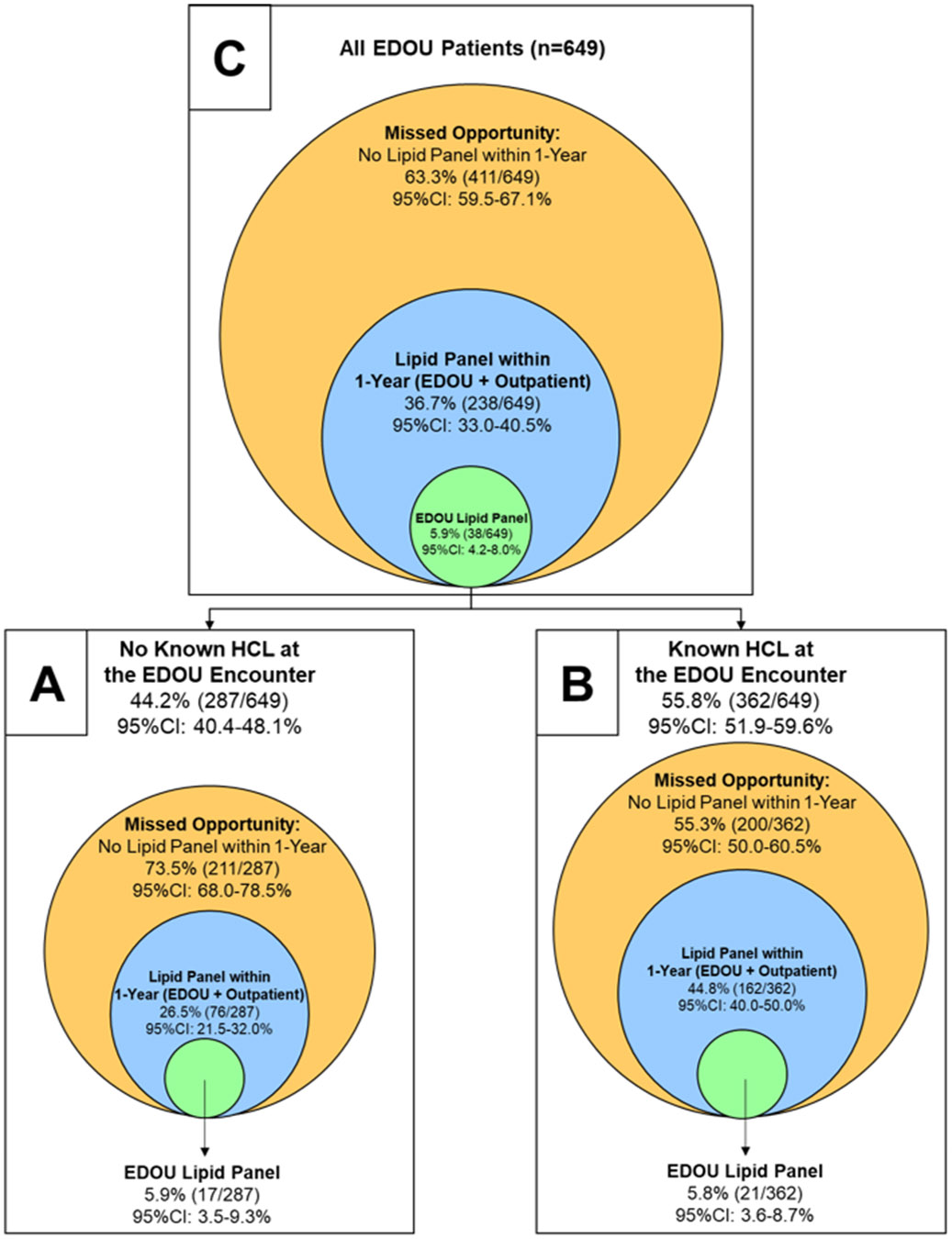

In patients without known HCL, just 26.5% (76/287, 95%CI 21.5-32.0%) were evaluated with a lipid panel in the ED/EDOU or outpatient setting within 1-year. This testing consisted of 5.9% (17/287) having a lipid panel in the ED/EDOU and 21.3% (61/287) in the outpatient setting. Among patients without known HCL, 21.6% (62/287) were given a new diagnosis of HCL, resulting in a total of 65.3% (424/649) of patients having a diagnosis of HCL at 1-year. Figure 1A demonstrates the missed HCL testing opportunities among patients without a known diagnosis of HCL.

Figure 1. Missed opportunity for EDOU HCL testing among patients with A) no known HCL, B) known HCL, and C) all patients.

HCL – Hypercholesterolemia, EDOU – Emergency Department Observation Unit

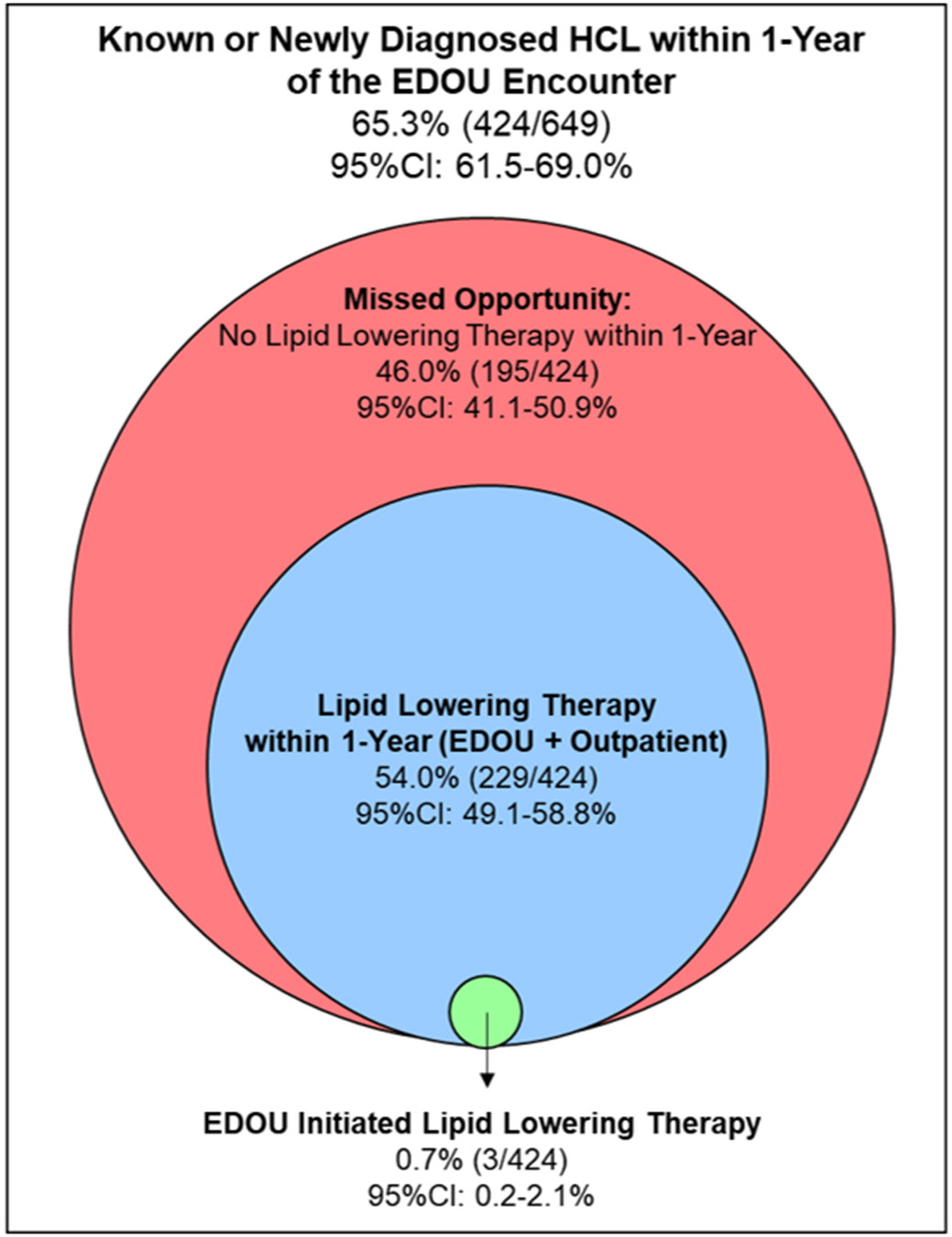

Among patients with known HCL, 44.8% (162/362, 95%CI 40.0-50.0%) were evaluated with a lipid panel in the ED/EDOU or outpatient setting. The ED/EDOU ordered a lipid panel in 5.8% (21/362) of these patients while outpatient providers ordered a lipid panel in 40.1% (145/362). Figure 1B shows the missed opportunity to evaluate patients with known HCL using a lipid panel. For patients with known HCL during the ED/EDOU encounter, 48.1% (174/362, 95%CI 36.3-45.9%) were not on a lipid lowering agent at any point during the ED/EDOU encounter or follow-up period. The EDOU prescribed HCL treatment to just 0.3% (1/362) of patients with known HCL. For patients with newly diagnosed HCL, the EDOU started 3.2% (2/62) on lipid lowering therapy while 66.1% (41/62) were on therapy within 1-year of EDOU discharge. Overall, 54.0% (229/424, 95%CI 49.1-58.8%) of patients with known or newly diagnosed HCL were on treatment within 1-year. Figure 2 describes the missed opportunity for initiating treatment among patients with known or newly diagnosed HCL.

Figure 2. Missed opportunity EDOU-initiated lipid lowering therapy among patients with known or newly diagnosed HCL.

HCL – Hypercholesterolemia, EDOU – Emergency Department Observation Unit

At 1-year, 36.7% (238/649, 95%CI 33.0-40.5%) of all patients were tested with a lipid panel, including 5.9% (38/649) in the EDOU and 31.7% (206/649) in the outpatient setting. Among these, 0.9% (6/649) were tested in both care settings. Figure 1C demonstrates the missed testing opportunity among all patients. Testing rates at 1-year were similar for white vs. non-white patients (36.2% [132/365] vs. 37.3% [106/284]; OR 0.95, 95%CI 0.69-1.31; p=0.81) and men vs. women (32.7% [86/263] vs. 39.4% [152/386]; OR 0.75, 95%CI 0.54-1.04; p=0.10). In the adjusted model, testing rates remained similar among white vs. non-white patients (aOR 0.91, 95%CI 0.65-1.27) and men vs. women (aOR 0.79, 95%CI 0.57-1.11). Rates of HCL therapy at 1-year among patients with known or newly diagnosed HCL were similar among white vs. non-white (50.6% [123/243] vs. 58.6% [106/181]; OR 0.73, 95%CI 0.49-1.07; p=0.12) and male vs. female (55.7% [93/167] vs. 52.9% [136/257]; OR 1.12, 95%CI 0.76-1.65; p=0.62) patients. After adjusting, therapy rates at 1-year remained similar among white vs. non-white (aOR 0.74, 95%CI 0.53-1.03) and male vs. female (aOR 1.08, 95%CI 0.77-1.51) patients.

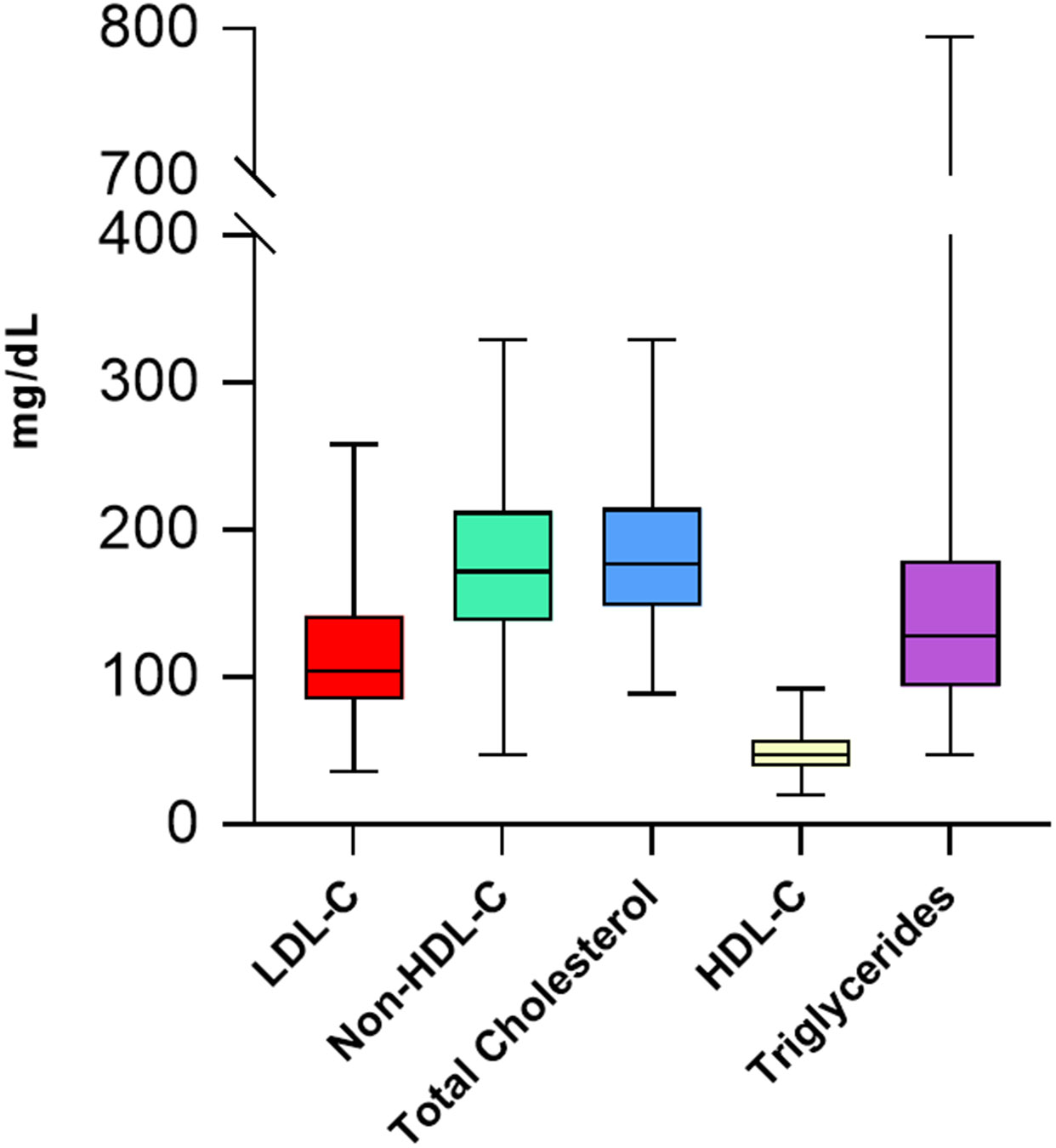

Among the 36.7% (238/649) of patients with lipid panel testing in the ED/EDOU or within 1-year of follow-up, full lipid panel results were available for 83.6% (199/238). Lipid panel results are summarized in Table 2. Patients on lipid lowering therapy during the ED/EDOU encounter or within 1-year of the encounter had lower LDL-C measurements compared to patients not on therapy (106.6±42.8mg/dL vs. 122.0±40.3 mg/dL; p=0.02). Figure 3 shows the overall lipid measurement distributions.

Table 2.

Lipid measurements among patients with a lipid profile within 1-year after the EDOU encounter.

| Measure | Any Therapy (n=92) |

No Therapy (n=107) |

Overall (n=199) |

Absolute Difference (95%CI) |

p-value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDL-C (mg/dL) (mean±SD) | 106.6±42.8 | 122.0±40.3 | 113.0±42.3 | 15.4 (2.1-28.6) | 0.02 |

| Non-HDL-C (mg/dL) (mean±SD) | 172.4±51.8 | 174.9±58.9 | 173.5±55.1 | 2.5 (−13.0-18.0) | 0.75 |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) (mean±SD) | 178.5±49.6 | 187.8±49.2 | 182.8±49.5 | 9.3 (−4.6-23.1) | 0.19 |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) (mean±SD) | 48.4±14.0 | 50.4±14.8 | 49.3±14.3 | 1.9 (−2.1-6.0) | 0.34 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) (median, IQR) | 123.0 (92.0-176.0) | 139.5 (101.0-181.5) | 127.5 (94.0-178.0) | 9.0 (−9.0-26.0)* | 0.33 |

LDL-C – low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, Non-HDL-C – non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, HDL-C – high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

Comparisons between groups made with the two-sample t-test, except for triglycerides, which were compared using the Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test

Difference calculated using the Hodges-Lehmann estimator

Figure 3. Lipid measurement distributions.

LDL-C – low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, Non-HDL-C – non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, HDL-C – high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

DISCUSSION

Current ED and EDOU care practices among patients with acute chest pain miss a large opportunity to reduce ASCVD risk by failing to evaluate for HCL or initiate lipid lowering therapy. Among patients without known HCL, more than 70% had not been evaluated for HCL at any point during the 1-year outpatient follow-up period. Similarly, among patients with known HCL, nearly 50% were not on any form of lipid lowering therapy in the 1-year follow-up window. These findings suggest that the EDOU chest pain patient population is at high risk for undiagnosed and unmanaged HCL, a key contributor to ASCVD risk.

Addressing HCL is a leading priority for the US Department of Health and Human Services’ (DHHS) in its “Healthy People 2030” initiative.30 An ED- or EDOU-based preventive care model for HCL directly addresses two key Healthy People 2030 objectives: “Increase cholesterol treatment in adults” and “Reduce cholesterol in adults.” Furthermore, the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM) and the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) have adopted policy statements encouraging emergency providers to initiate preventive cardiovascular care.16-19 However, neither SAEM nor ACEP specifically address HCL testing or management. However, an ED- or EDOU-based HCL testing and treatment program meets these high-priority DHHS objectives, aligns with national emergency medicine organization preventive care policies, and may have the ability to drastically reduce ASCVD risk among patients with undiagnosed or unmanaged HCL.

Multiple lipid lowering drugs exist, which the ED or EDOU could use to treat HCL. Statins are by far the most commonly prescribed lipid lowering medication.31 A large meta-analysis found that statins are effective in lowering LDL-C and that for every 38.7 mg/dL reduction in LDL-C, five-year ASCVD risk is reduced by 24% and cardiac death by 20%.32 Furthermore, the US Preventive Services Task Force found that statins are safe, well-tolerated, and associated with decreased all-cause mortality (RR 0.86), stroke (RR 0.71), and myocardial infarction (RR 0.64).33 Additionally, statins are largely affordable and available for less than $20 for a 30-day supply.34 Given the unmet need for HCL therapy and the safety, effectiveness, minimal side effects, and affordability of statin medications, the ED and EDOU are likely in a prime position to initiate statin therapy for patients with HCL.

An ED- or EDOU-based approach to HCL diagnosis and management may help reduce cardiovascular care disparities. Black, female, and uninsured patients are less likely to have a source for primary care.23 These subgroups are also traditionally thought to be less likely to be prescribed HCL therapy.24,35,36 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey literature suggests that black patients are up to 40% less likely to be prescribed a statin than white patients.36,37 Given the barriers associated with accessing outpatient primary care, no required co-pays in the ED or EDOU, and 24/7/365 ED availability, economically and socially disadvantaged patients may use the ED or EDOU for primary care instead of a traditional outpatient care team.38 However, within our cohort, the rates of testing for HCL at 1-year were similarly low among men vs. women and white vs. non-white patients. However, 8% more non-white patients received HCL therapy at 1-year than white patients. Although this finding was not statistically significant, it suggests that. among this select patient population, a race-based disparity in HCL therapy may not exist. However, this inference is limited by sample size.

Historically, LDL-C levels have been used to guide the initiation of lipid lowering therapy. However, current preventive cardiovascular care guidelines generally recommend assessing 10-year ASCVD risk rather than just LDL-C levels before initiating therapy for primary prevention.39-41 As anticipated, we found that patients on lipid lowering therapy during the 1-year follow-up period had lower levels of LDL-C compared to patients not on lipid lowering therapy. However, non-HDL-C, total cholesterol, HDL-C, and triglyceride levels were similar among groups. It is likely that this analysis was underpowered to detect a difference in these measures. Multiple previous high-quality randomized controls trials have demonstrated that statins lower non-HDL-C, total cholesterol, and triglyceride levels while raising HDL-C.42,43

LIMITATIONS

This study has limitations. The generalizability of this study may be limited because it was conducted at a single academic site and among a select group of patients being evaluated for possible acute coronary syndrome in the EDOU. Data were retrospectively collected using the EHR of a single healthcare system. It is possible that patients received HCL testing or therapy in an outside healthcare system. However, previous studies have demonstrated high health system brand loyalty among our patients, making this source of misclassification bias less likely.44 HCL was defined by self-report or clinician diagnosis in the EHR, possibly contributing to misclassification bias. Furthermore, lifestyle interventions for HCL were not recorded. Finally, precision and power to detect differences were limited by the sample size.

CONCLUSION

Among ED patients with acute chest pain who were evaluated in the EDOU, we found a large missed opportunity to reduce ASCVD risk by failing to assess for HCL and initiate lipid lowering therapy. The lack of outpatient preventive cardiovascular care for HCL following the initial EDOU visit suggests that the ED or EDOU setting may be the only preventive cardiovascular care option accessible for many patients. These findings suggest that it may be reasonable for ED and EDOU providers to routinely screen patients with chest pain for HCL with a lipid panel and initiate safe and effective pharmacotherapy when indicated. Future research should test ED- and EDOU-based HCL diagnosis and treatment strategies.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Gregory Noe, Ian Kinney, Ryan Morgan, Weston Colbaugh, Ravenna Chhabria, Benjamin Brendamour, James Black, Harris Cannon, and Philip Kayser for their assistance with data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Ashburn receives funding from NHLBI (T32HL076132).

Dr. Snavely receives funding from Abbott and HRSA (1H2ARH399760100).

Dr. Rikhi receives funding from NHLBI (T32HL076132).

Dr. Shapiro has participated in scientific advisory boards with Amgen, Novartis, Ionis, Precision BioSciences and has served as a consultant for Regeneron, Ionis, Novartis, and EmendoBio.

Dr. Stopyra receives research funding from NCATS/NIH (KL2TR001421), HRSA (H2ARH39976-01-00), Roche Diagnostics, Abbott Laboratories, Pathfast, Genetesis, Cytovale, Forest Devices, Vifor Pharma, and Chiesi Farmaceutici.

Dr. Mahler receives funding/support from Roche Diagnostics, Abbott Laboratories, QuidelOrtho, Siemens, Grifols, Pathfast, Genetesis, Cytovale, and HRSA (1H2ARH399760100). He is a consultant for Roche, Abbott, Beckman Coulter, Siemens, Genetesis, Inflammatix, Radiometer, and Amgen and is the Chief Medical Officer for Impathiq Inc.

The other authors report no conflicts.

Footnotes

CRediT Statement:

Nicklaus P. Ashburn MD, MS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing (Original Draft), Writing (Review and Editing), Visualization, Project Administration

Anna C. Snavely PhD: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing (Original Draft), Writing (Review and Editing), Visualization,

Rishi Rikhi MD, MS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing (Review and Editing)

Michael D. Shapiro DO, MCR: Methodology, Investigation, Writing (Review and Editing), Supervision

Michael A. Chado MD: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing (Review and Editing)

Alexander P. Ambrosini MD: Investigation, Writing (Review and Editing)

Amir A. Biglari: Investigation, Writing (Review and Editing)

Spencer T. Kitchen: Investigation, Writing (Review and Editing)

Marissa J. Millard: Investigation, Writing (Review and Editing)

Jason P. Stopyra MD, MS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Resources, Writing (Review and Editing), Supervision

Simon A. Mahler MD, MS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Resources, Writing (Original Draft), Writing (Review and Editing), Visualization, Supervision

REFERENCES

- 1.Virani SS, Alonso A, Aparicio HJ, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2021 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021;143(8):e254–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ference BA, Ginsberg HN, Graham I, et al. Low-density lipoproteins cause atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. 1. Evidence from genetic, epidemiologic, and clinical studies. A consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. Eur Heart J 2017;38(32):2459–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vassy JL, Lu B, Ho Y-L, et al. Estimation of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Risk Among Patients in the Veterans Affairs Health Care System. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3(7):e208236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boekholdt SM, Arsenault BJ, Mora S, et al. Association of LDL cholesterol, non-HDL cholesterol, and apolipoprotein B levels with risk of cardiovascular events among patients treated with statins: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2012;307(12):1302–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration, Di Angelantonio E, Sarwar N, et al. Major lipids, apolipoproteins, and risk of vascular disease. JAMA 2009;302(18):1993–2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prospective Studies Collaboration, Lewington S, Whitlock G, et al. Blood cholesterol and vascular mortality by age, sex, and blood pressure: a meta-analysis of individual data from 61 prospective studies with 55,000 vascular deaths. Lancet 2007;370(9602):1829–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johannesen CDL, Mortensen MB, Langsted A, Nordestgaard BG. Apolipoprotein B and Non-HDL Cholesterol Better Reflect Residual Risk Than LDL Cholesterol in Statin-Treated Patients. J Am Coll Cardiol 2021;77(11):1439–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charlton-Menys V, Betteridge DJ, Colhoun H, et al. Targets of statin therapy: LDL cholesterol, non-HDL cholesterol, and apolipoprotein B in type 2 diabetes in the Collaborative Atorvastatin Diabetes Study (CARDS). Clin Chem 2009;55(3):473–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.CDCTobaccoFree. Tobacco-Related Mortality [Internet]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020. [cited 2022 Aug 15];Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/health_effects/tobacco_related_mortality/index.htm [Google Scholar]

- 10.CDCTobaccoFree. Health Effects [Internet]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2022. [cited 2022 Aug 15];Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/health_effects/index.htm [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martha Gulati, Levy Phillip D., Debabrata Mukherjee, et al. 2021 AHA/ACC/ASE/CHEST/SAEM/SCCT/SCMR Guideline for the Evaluation and Diagnosis of Chest Pain. J Am Coll Cardiol 2021;78(22):e187–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2017 emergency department summary tables [Internet]. National Center for Health Statistics.; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhamcs/web_tables/2017_ed_web_tables-508.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katz DA, Vander Weg MW, Holman J, et al. The Emergency Department Action in Smoking Cessation (EDASC) trial: impact on delivery of smoking cessation counseling. Acad Emerg Med 2012;19(4):409–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katz DA, Graber M, Birrer E, et al. Health beliefs toward cardiovascular risk reduction in patients admitted to chest pain observation units. Acad Emerg Med 2009;16(5):379–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katz DA, Graber M, Lounsbury P, et al. Multiple Risk Factor Counseling to Promote Heart-healthy Lifestyles in the Chest Pain Observation Unit: Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Acad Emerg Med 2017;24(8):968–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rhodes KV, Gordon JA, Lowe RA. Preventive care in the emergency department, Part I: Clinical preventive services--are they relevant to emergency medicine? Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Public Health and Education Task Force Preventive Services Work Group. Acad Emerg Med 2000;7(9):1036–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Babcock Irvin C, Wyer PC, Gerson LW. Preventive care in the emergency department, Part II: Clinical preventive services--an emergency medicine evidence-based review. Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Public Health and Education Task Force Preventive Services Work Group. Acad Emerg Med 2000;7(9):1042–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lowenstein SR, Koziol-McLain J, Thompson M, et al. Behavioral risk factors in emergency department patients: a multisite survey. Acad Emerg Med 1998;5(8):781–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bernstein SL, Boudreaux ED, Cydulka RK, et al. Tobacco control interventions in the emergency department: a joint statement of emergency medicine organizations. Ann Emerg Med 2006;48(4):e417–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaddy JD, Davenport KTP, Hiestand BC. Cardiovascular Conditions in the Observation Unit: Beyond Chest Pain. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2017;35(3):549–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borawski JB, Graff LG, Limkakeng AT. Care of the Patient with Chest Pain in the Observation Unit. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2017;35(3):535–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ross MA, Aurora T, Graff L, et al. State of the art: emergency department observation units. Crit Pathw Cardiol 2012;11(3):128–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levine DM, Linder JA, Landon BE. Characteristics of Americans With Primary Care and Changes Over Time, 2002-2015. JAMA Intern Med 2020;180(3):463–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Safford MM, Gamboa CM, Durant RW, et al. Race-sex differences in the management of hyperlipidemia: the REasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke study. Am J Prev Med 2015;48(5):520–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mital R, Bayne J, Rodriguez F, Ovbiagele B, Bhatt DL, Albert MA. Race and Ethnicity Considerations in Patients With Coronary Artery Disease and Stroke: JACC Focus Seminar 3/9. J Am Coll Cardiol 2021;78(24):2483–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balla S, Gomez SE, Rodriguez F. Disparities in Cardiovascular Care and Outcomes for Women From Racial/Ethnic Minority Backgrounds. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med 2020;22(12):75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies ∣ The EQUATOR Network [Internet]. Available from: http://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/strobe/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Worster A, Bledsoe RD, Cleve P, Fernandes CM, Upadhye S, Eva K. Reassessing the methods of medical record review studies in emergency medicine research. Ann Emerg Med 2005;45(4):448–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaji AH, Schriger D, Green S. Looking through the retrospectoscope: reducing bias in emergency medicine chart review studies. Ann Emerg Med 2014;64(3):292–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heart Disease and Stroke [Internet]. [cited 2022 Sep 1];Available from: https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/heart-disease-and-stroke

- 31.Gu Q, Paulose-Ram R, Burt VL, Kit BK. Prescription cholesterol-lowering medication use in adults aged 40 and over: United States, 2003-2012. NCHS Data Brief 2014;(177):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration, Baigent C, Blackwell L, et al. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet 2010;376(9753):1670–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.US Preventive Services Task Force, Mangione CM, Barry MJ, et al. Statin Use for the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2022;328(8):746–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jackevicius CA, Choi K, Krumholz HM. Access to Evidence-Based Statins in Low-Cost Generic Drug Programs. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2016;9(6):785–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schroff P, Gamboa CM, Durant RW, Oikeh A, Richman JS, Safford MM. Vulnerabilities to Health Disparities and Statin Use in the REGARDS (Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke) Study. J Am Heart Assoc [Internet] 2017;6(9). Available from: 10.1161/JAHA.116.005449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mann D, Reynolds K, Smith D, Muntner P. Trends in statin use and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels among US adults: impact of the 2001 National Cholesterol Education Program guidelines. Ann Pharmacother 2008;42(9):1208–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gao Y, Shah LM, Ding J, Martin SS. US Trends in Cholesterol Screening, Lipid Levels, and Lipid-Lowering Medication Use in US Adults, 1999 to 2018. J Am Heart Assoc 2023;e028205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vogel JA, Rising KL, Jones J, Bowden ML, Ginde AA, Havranek EP. Reasons Patients Choose the Emergency Department over Primary Care: a Qualitative Metasynthesis. J Gen Intern Med 2019;34(11):2610–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goff DC Jr, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2014;129(25 Suppl 2):S49–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2019;139(25):e1082–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;74(10):e177–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Davidson M, Ma P, Stein EA, et al. Comparison of effects on low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol with rosuvastatin versus atorvastatin in patients with type IIa or IIb hypercholesterolemia. Am J Cardiol 2002;89(3):268–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nicholls SJ, Ballantyne CM, Barter PJ, et al. Effect of two intensive statin regimens on progression of coronary disease. N Engl J Med 2011;365(22):2078–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mahler SA, Lenoir KM, Wells BJ, et al. Safely Identifying Emergency Department Patients With Acute Chest Pain for Early Discharge [Internet]. Circulation. 2018;138(22):2456–68. Available from: 10.1161/circulationaha.118.036528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.