Abstract

Overwhelming evidence suggests that physical activity among youth can prevent mental illness; however, few studies have explored its effects on mental healthcare utilization. This study aimed to examine the longitudinal associations between physical activity among Canadian adolescents and young adults (AYAs; 12–24 years) and incidence of psychiatric hospitalizations. Physical activity was measured in the 2001–2014 Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) and was linked to the Discharge Abstract Database. Negative binomial regression analyses were performed on each CCHS cycle to obtain incidence rate ratios (IRRs) for psychiatric hospitalizations by level of physical activity, which were subsequently meta-analyzed to obtain pooled estimates. In total, 96,100 participants were recruited across eleven cycles. Adolescents were more physically active (52%) compared to young adults (39%). The most common cause of hospitalization was mood or anxiety disorders (38%). Fully adjusted models found that moderately active (IRR = 1.30; 95% CI: 1.02–1.66; p = 0.01) and inactive (IRR = 1.33; 95% CI: 1.06–1.66; p = 0.01) participants had higher rates of psychiatric hospitalizations compared to active participants. Our findings suggest that lower levels of physical activity among AYAs were associated with an increased incidence of psychiatric hospitalizations, providing valuable insights for stakeholders and laying the groundwork for future research.

Keywords: Adolescents, Young adults, Physical activity, Mental disorders, Psychiatric hospitalizations

Subject terms: Epidemiology, Psychiatric disorders

Introduction

The consequences of mental illness are multifaceted; negatively impacting the economy, the healthcare system, and the lives of millions1–5. Approximately 6.7 million Canadians experience mental illness at a given time, costing the Canadian economy over $50 billion annually1,5. Mental illness carries a myriad of personal burdens through stigmatization, reduced quality of life, greater risk for morbidity and mortality, and negative familial impacts6–10. These issues are especially pronounced among adolescents and young adults (AYAs), who experience the highest rates of mental illness and are among the largest users of mental health services in Canada11–16. The high incidence of mental disorders among AYAs is particularly concerning as psychological problems tend to persist across an individual’s life course, potentially leading to high amounts of future personal and societal burdens5,17–19. Therefore, it is imperative to invest in early mental health promotion and mental illness prevention strategies20–23.

Over the past several decades, physical activity has emerged as a promising modifiable risk factor for the prevention of mental disorders in young people24–28. This rich body of evidence has produced several systematic reviews and meta-analyses demonstrating the many benefits of increased physical activity on quality of life, pro-social behaviours, and cognitive functioning, and decreases in mood and anxiety disorders, psychotic disorders, substance use, and emotional problems24–27. One review elucidated a causal link between increased adolescent physical activity and higher cognitive functioning, and a partial causal link with decreased depressive symptoms26. Similar benefits are observed in young adults; however, far fewer studies have examined this age group28–31. Furthermore, studies have found the relationship between physical activity and mental health to be bidirectional32–35. For instance, an analysis among adolescents found that lower levels of physical activity predicted depressive symptoms, while also revealing that prior depressive symptoms predicted future levels of physical activity35. Likewise, studies of this bidirectional relationship in adults have suggested that depressive symptoms in early adulthood may act as a barrier to future engagement in regular physical activity34. Nonetheless, several studies have indicated that the bidirectional relationship is more pronounced when examining the impact of physical activity on depressive symptoms32,34,35. Despite the many benefits, only approximately 40% of Canadian children and youth meet recommended levels of physical activity, which poses many concerns to the healthcare system36,37.

While a plethora of studies have established the mental health benefits of physical activity, far less is known about its ability to prevent the use of costly mental health services38–43. Thus, the objective of this study was to explore the longitudinal associations between physical activity during adolescence and young adulthood and incidence of psychiatric hospitalizations through the utilization of health survey data linked to administrative data in Canada. Generating evidence to demonstrate the effects of physical activity on mental healthcare utilization can provide decision makers with the policy-relevant information needed for implementing mental illness prevention strategies through physical activity.

Methods

Data sources

The Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) is a nationally representative cross-sectional survey reporting on health behaviours among the Canadian household population aged 12 and older in all provinces and territories44. CCHS cycles 1.1 (2001), 2.1 (2003), and 3.1 (2005) collected data over 2-year periods and recruited approximately 130,000 participants per cycle. Since 2007, the CCHS has been administered annually, recruiting approximately 65,000 participants per cycle45. The sampling procedure follows a multistage stratified cluster design, with data collected through online electronic questionnaires or computer-assisted telephone interviews44. Response rates for the CCHS have ranged from 69.8%−78.9%, with approximately 86% of all respondents agreeing to record linkages45. Exclusion criteria for the CCHS include the following: persons living on Indigenous reserves, full-time members of the Canadian Armed Forces, institutionalized populations, children living in foster care, and two remote health regions in Quebec; altogether, approximately 96% of Canadians are represented in this target population45.

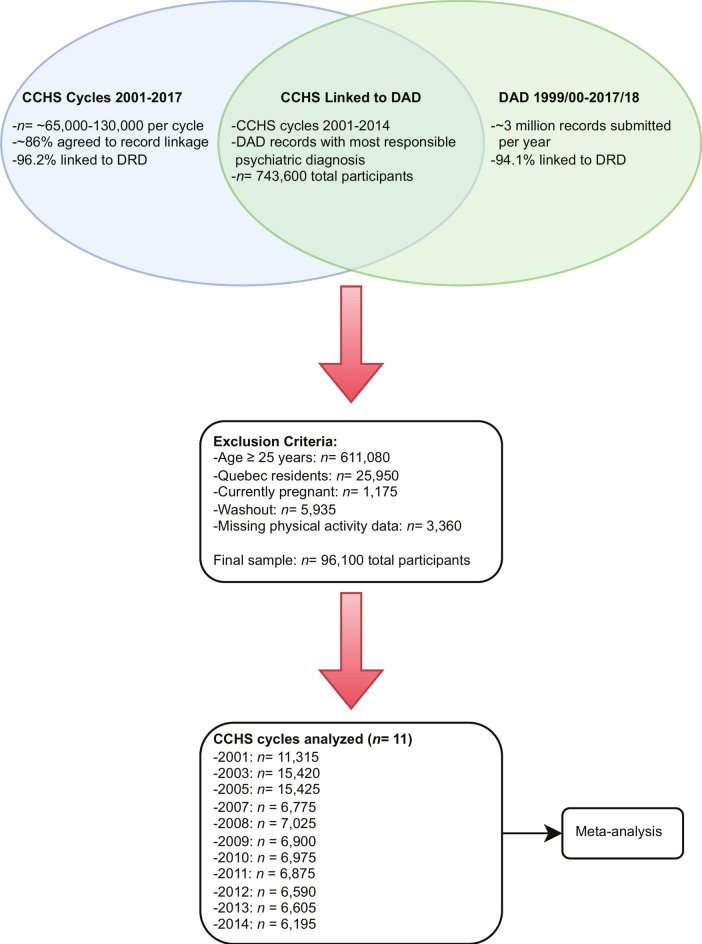

The Discharge Abstract Database (DAD) contains administrative, clinical, and demographic information recorded upon all discharges from acute inpatient care settings in all Canadian provinces and territories except Quebec46. Upon discharge from these care settings, patient’s health records are coded and abstracted before being sent to the Canadian Institute for Health Information to be recorded in the DAD46. Diagnostic codes found in the DAD are reported using the International Classification of Diseases- Nineth and Tenth revisions (ICD-9 and ICD-10)46. The Canadian Vital Statistics Database (CVSD) was used for censoring participants who had died to obtain more reliable estimates of person-time at risk. All data files were linked to the Derived Record Depository (DRD) at Statistics Canada using probabilistic (CCHS and CVSD) or deterministic (DAD) linkage methods; 96.2% of CCHS records, 94.1% of DAD records, and 99.8% of CVSD records were successfully linked to the DRD (Fig. 1)45.

Fig. 1.

Venn diagram combined with flow diagram to illustrate the linkage process between data sources, exclusion criteria, and sample sizes.

Study design and setting

This analysis follows a prospective cohort study design, wherein eligible participants from the CCHS were recruited, categorized by physical activity level, and followed for the outcome of psychiatric hospitalizations. Eligible participants in the 2001–2014 CCHS were identified and linked to the 1999/00–2017/18 DAD. The study period began January 1, 1999 and ended March 31, 2018, encompassing all available DAD records. Participants were followed from their CCHS interview date until the first of either the study end date or their date of death. Eleven CCHS cycles were linked to the DAD, independently analyzed, and subsequently meta-analyzed (Fig. 1). Approval for use of microdata linkages was provided by Statistics Canada and accessed through the Prairie Regional Research Data Centre located at the University of Calgary. According to the Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans – TCPS 2 (available at: https://ethics.gc.ca/eng/tcps2-eptc2_2018_chapter2-chapitre2.html#2) governed by the Government of Canada, research involving data that are publicly available through legislation protected by law and where dissemination of results do not generate identifiable information, as in the case for this study, is exempt from Research Ethics Board review. Respondents to the CCHS provided informed consent to participate in the survey and provided additional consent for linkage to administrative data records. Reporting of these findings were completed in accordance with the RECORD Checklist for health administrative data47.

Participants

Our sample consisted of respondents to the 2001–2014 CCHS cycles who were aged 12–24 years at the time of their interview and provided consent to record linkage (Fig. 1). Participants who resided in Quebec, were pregnant at time of their interview, or who had missing physical activity data were excluded (Fig. 1). A 2-year washout period was applied, wherein participants with a most responsible psychiatric diagnosis 2-years prior to their interview date, or whose interview date occurred within 2-years of the study start date, were excluded from analysis (Fig. 1).

Variables

The following CCHS variables were used to obtain demographic and covariate data: age, sex, body mass index (BMI), chronic conditions, smoking status, alcohol use, highest household education, household income, and race. Participants aged 12–17 years were categorized as adolescents, while participants aged 18–24 years were categorized as young adults. Adolescents were categorized as underweight, normal weight, overweight, or obese based on age- and sex-standardized Cole Classification cut-offs for children48,49. Young adults were similarly grouped into underweight (< 18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25–29.9 kg/m2), or obese (≥ 30 kg/m2) based on the World Health Organization adult BMI cut-offs50. Chronic conditions were dichotomized into having at least one or none of the following conditions: diabetes, cardiovascular disease, inflammatory bowel disease, or cancer. Smoking and alcohol use were both categorized as regular use (daily smoker; regular drinker), occasional use (former daily smoker or less than 100 lifetime cigarettes; occasional drinker), or never use (current non-smoker or never smoker; no drink in the past 12-months). Highest household education was categorized as lower than high school, lower than post-secondary, or higher than post-secondary. CCHS cycles 2001 and 2003 used a 5-level income adequacy variable based on total household income and number of people living in the household, while cycles 2005 and onwards used distribution of provincial income (deciles). Race was dichotomized as White or non-White.

Physical activity was measured using the Minnesota Leisure-Time Physical Activity Questionnaire (LTPAQ), which is a self-reported questionnaire used to estimate respondents’ metabolic equivalents (METs) during leisure-time physical activities (LTPA) based on type of activity, frequency, and bout duration over the past 3 months51. METs are then converted into average energy expenditure (AEE) measured in kilocalories per kilogram per day (KKD). Participants in the CCHS were categorized as inactive (< 1.5 KKD), moderately active (1.5 – 2.99 KKD), or active (≥ 3.0 KKD). Energy expenditure in the Minnesota LTPAQ were found to be highly correlated with values obtained from accelerometry and doubly labelled water51,52. All variables from the CCHS were measured at a single point-in-time in the year from which a participant was interviewed.

Chapter 5: Mental disorders (290–319) of ICD-9 and Chapter V: Mental and behavioural disorders (F00-F99) of ICD-10 reported as the most responsible diagnosis for each hospital discharge in the DAD were used to measure psychiatric hospitalizations occurring after each participant’s CCHS interview. For descriptive purposes, mental disorders were subclassified into mood and anxiety, substance related, psychosis, personality, organic, and other disorders. A person-time variable counted days between a participant’s CCHS interview date and whichever occurred first between the study end date or a participant’s death date.

Statistical analysis

Sample characteristics for each survey were calculated using sampling and replicate bootstrap weights, which were necessary to address the unequal selection probabilities arising from the complex sampling design in the CCHS. Descriptive estimates from each survey were pooled using random-effects meta-analysis and were represented as pooled percent proportions. Physical activity was analyzed in three levels, with the active participants used as the referent group. Psychiatric diagnoses were represented as count data, and due to over-dispersion, negative binomial regression models with log follow-up time offsets were used. To account for outliers, psychiatric diagnoses were Winsorized at the 99thpercentile. Cumulative incidence for each survey was calculated as the percent proportion of participants receiving at least one psychiatric hospitalization. Incidence rates for each cycle were calculated using unweighted counts of psychiatric hospitalizations and person-time denominators (psychiatric hospitalizations per 100,000 person-days). Models were built by assessing the Akaike information criterion values of several models that featured different covariates, interaction terms, and other count regression models for each survey. The following models were selected based on goodness-of-fit, parsimony, and consistency throughout all eleven survey cycles: crude models, age- and sex-adjusted models, and full models adjusting for all covariates. For cycles 2001–2005, additional age-stratified analyses of the full model were conducted. Cycles 2007–2014 could not support age-stratification due to their reduced sample sizes and low frequency of events. Regression coefficients and bootstrapped standard errors were used in subsequent random-effects meta-analyses using DerSimonian and Laird weighting. All analyses were performed using sample and bootstrap weights, significance levels of α = 0.05, and included 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata 16 and figures were generated using the tidyverse package in RStudio53,54.

Results

Descriptive analysis

The total sample size for all eleven surveys combined was 96,100. The mean follow-up time among all participants was 9.29-years (95% CI: 7.50–11.08) (Table 1.). This sample included fewer adolescents (43.60%) compared to young adults (56.40%) with similar proportions of males (51.46%) and females (48.53%) (Table 1.). The greatest number of participants were from Ontario (51.59%), British Columbia (16.29%), and Alberta (14.56%), with no other province or territory exceeding a proportion of 5% (Table 1.). A large proportion of this sample’s population were White (74.46%), had high levels of household education (76.51%), had no chronic conditions (97.50%), and were normal weight (65.42%) (Table 1.).

Table 1.

Pooled demographic characteristics for CCHS cycles 2001-2014.

| Characteristic | Percent Proportions (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Total sample size (n) | 96,100 | |

| Mean follow-up time in years (95% CI) | 9.29 (7.50–11.08) | |

| Age group | ||

| Adolescents (12–17 years) | 43.60 (42.60–44.60) | |

| Young adults (18–24 years) | 56.40 (55.40–57.39) | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 51.46 (51.00–51.92) | |

| Female | 48.53 (48.07–48.99) | |

| Province | ||

| Ontario | 51.59 (51.26–51.92) | |

| British Columbia | 16.29 (16.03–16.55) | |

| Alberta | 14.56 (14.26–14.86) | |

| Manitoba | 4.63 (4.51–4.75) | |

| Saskatchewan | 4.01 (3.92–4.10) | |

| Nova Scotia | 3.38 (3.19–3.57) | |

| New Brunswick | 2.63 (2.52–2.73) | |

| Newfoundland & Labrador | 1.88 (1.75–2.02) | |

| Prince Edward Island | 0.56 (0.54–0.59) | |

| Northwest Territories | 0.19 (0.18–0.20) | |

| Nunavut | 0.13 (0.11–0.15) | |

| Yukon | 0.13 (0.13–0.14) | |

| White/non-White | ||

| White | 74.46 (72.13–76.79) | |

| Non-White | 25.54 (23.21–27.87) | |

| Highest household education | ||

| Less than high school | 3.23 (2.84–3.63) | |

| Greater than high school, less than post-secondary | 20.26 (18.92–21.60) | |

| Post-secondary and higher | 76.51 (74.79–78.22) | |

| Household income- deciles a | ||

| 1 | 13.57 (12.82–14.31) | |

| 2 | 11.13 (10.68–11.57) | |

| 3 | 10.70 (10.38–11.03) | |

| 4 | 10.33 (9.88–10.79) | |

| 5 | 10.29 (9.76–10.81) | |

| 6 | 10.21 (9.84–10.59) | |

| 7 | 9.18 (8.67–9.69) | |

| 8 | 9.28 (8.85–9.71) | |

| 9 | 8.45 (7.93–8.97) | |

| 10 | 6.86 (6.50–7.22) | |

| Smoking status | ||

| Regular | 10.94 (9.58–12.29) | |

| Occasional | 6.37 (5.93–6.82) | |

| Not at all | 82.69 (81.08–84.29) | |

| Alcohol status | ||

| Regular drinker | 45.97 (44.62–47.32) | |

| Occasional drinker | 17.34 (16.48–18.21) | |

| Not at all | 36.69 (35.43–37.95) | |

| Chronic conditions | ||

| No | 97.50 (97.19–97.81) | |

| Yes | 2.50 (2.19–2.81) | |

| Body mass index | ||

| Underweight | 6.85 (6.55–7.14) | |

| Normal weight | 65.42 (64.60–66.24) | |

| Overweight | 19.20 (18.82–19.59) | |

| Obese | 8.54 (7.94–9.13) | |

| Physical activity level | ||

| Active | 44.92 (43.77–46.06) | |

| Moderately active | 22.89 (22.35–23.43) | |

| Inactive | 32.20 (31.27–33.13) | |

a CCHS cycles 2001–2003 omitted from pooled analyses due to different income measures used.

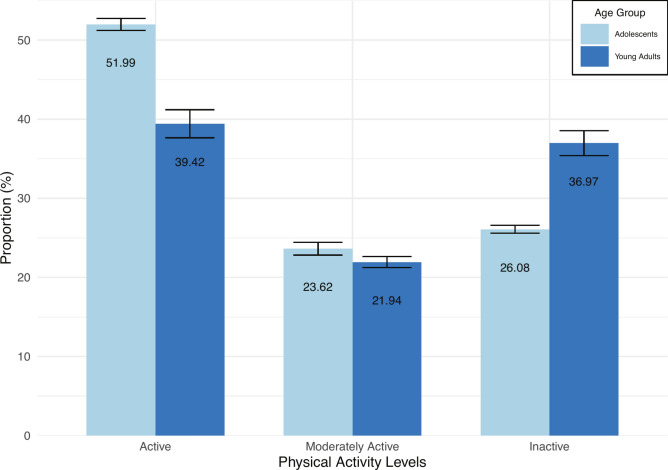

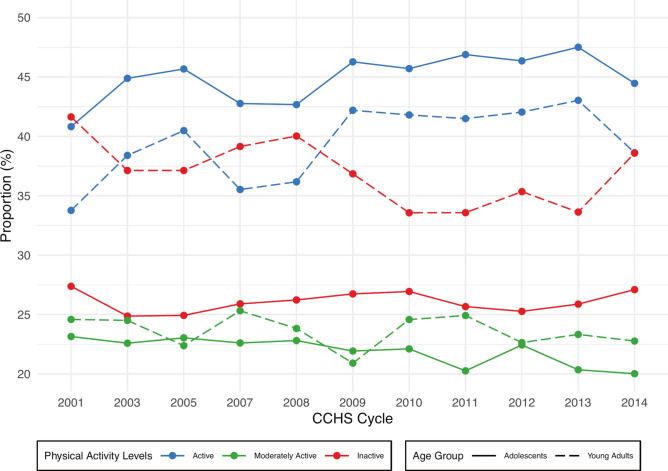

Overall, most participants were classified as being active (44.92%), followed by inactive (32.2%) and moderately active (22.89%) (Table 1.). By age group, adolescents had a higher proportion of active participants versus young adults (51.99% vs. 39.42%), similar proportions of moderately active participants (23.62% vs. 21.94%) and fewer inactive participants (26.08% vs. 36.97%) (Fig. 2). Comparing the first and last cycles, 40.82% (2001) to 44.47% (2014) of adolescents were active, 23.15% (2001) to 20.02% (2014) were moderately active, and 27.38% (2001) to 27.10% (2014) were inactive (Fig. 3). Among young adults, 33.77% (2001) to 38.63% (2014) were active, 24.59% (2001) to 22.77% (2014) were moderately active, and 41.64% (2001) to 38.59% (2014) were inactive (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Pooled percent proportion of physical activity levels between adolescents and young adults.

Fig. 3.

Percent proportion of physical activity levels among adolescents and young adults across all CCHS cycles.

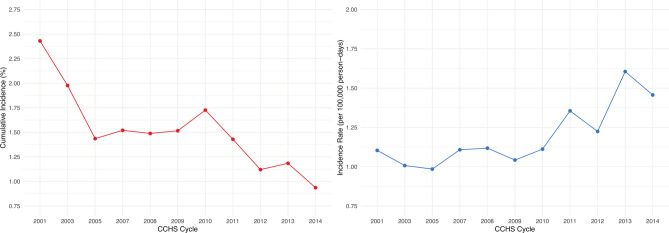

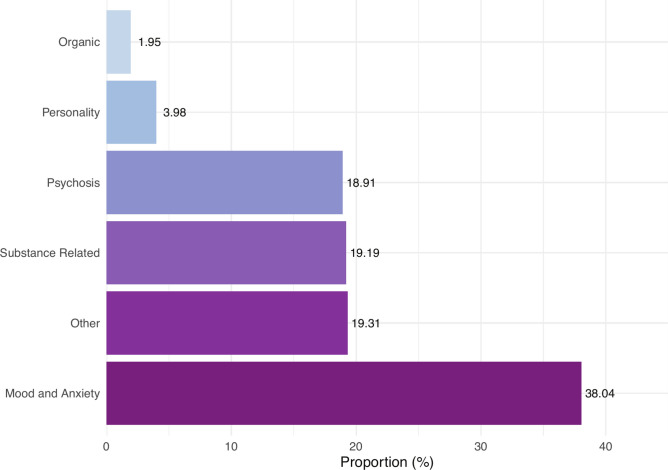

The cumulative incidence and incidence rates of psychiatric hospitalizations are shown in Fig. 4. Due to longer follow-up periods, earlier cycles had a higher cumulative incidence of psychiatric hospitalizations (2.43%; 2001) compared to later years (0.94%; 2014) (Fig. 4a). Incidence rates showed the opposite, with earlier cycles showing lower rates (1.10 per 100,000 person-days; 2001) compared to later cycles (1.46 per 100,000 person-days; 2014) (Fig. 4b). The most prevalent mental diagnosis reported was for mood and anxiety disorders (38.04%), followed by other (19.31%), substance related (19.19%), psychosis (18.91%), personality (3.98%), and organic (1.95%) disorders (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

(a) Cumulative incidence of psychiatric hospitalizations for each cycle of the CCHS. (b) Incidence rate of psychiatric hospitalizations for each cycle of the CCHS.

Fig. 5.

Pooled percent proportion of the most responsible diagnoses received for psychiatric hospitalizations.

Meta-analysis

All models meta-analyzed showed low heterogeneity (I2 < 25%), except for the age stratified models (I2 = 50.33%). As a result of the large samples sizes in the early CCHS, cycles 2001–2005 were the most strongly weighted in all meta-analyses performed. From the crude models, neither the moderately active (IRR = 1.18; 95% CI: 0.95–1.47; p = 0.14) nor inactive (IRR = 1.21; 95% CI: 0.99–1.47; p = 0.06) groups were significantly different from the active group (Table 2). When adjusted for age and sex, the moderately active group remained nonsignificant (IRR = 1.22; 95% CI: 0.98–1.51; p = 0.07), while the inactive group had a significantly higher IRR = 1.34 (95% CI: 1.07–1.69; p = 0.01) (Table 2). After adjustment for all covariates, both the moderately active group (IRR = 1.30; 95% CI: 1.02–1.66; p = 0.03) and the inactive group (IRR = 1.33; 95% CI: 1.06–1.66; p = 0.01) had significantly higher rates of hospitalizations compared to the active group (Table 2). In the age stratified analyses, adolescents showed no significant differences in either moderately active (IRR = 1.24; 95% CI: 0.69–2.25; p = 0.47) nor inactive (IRR = 1.02; 95% CI: 0.64–1.65; p = 0.93) groups, while in young adults, both moderately active (IRR = 1.83; 95% CI: 1.18–2.83; p = 0.01) and inactive (IRR = 1.63; 95% CI: 1.08–2.47; p = 0.02) groups had significantly higher rates of hospitalizations compared to active young adults (Table 2).

Table 2.

Calculated IRRs for physical activity levels and count of psychiatric diagnoses in CCHS cycles 2001–2014 with pooled overall estimates.

| CCHS Cycle | Crude Modelsb | Age- and Sex-Adjusted Models | Full Modelsbc | Full Models- Age Stratified | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescentsbc | Young Adultsbc | ||||

| Moderately Activea | |||||

| 2001 | 1.34 (0.76–2.38) | 1.37 (0.80–2.36) | 1.12 (0.63–1.97) | 0.68 (0.37–1.25) | 1.93 (0.94–3.99) |

| 2003 | 1.50 (0.78–2.91) | 1.47 (0.78–2.78) | 1.95 (1.03–3.68)d | 1.91 (1.04–3.52)d | 2.10 (1.01–4.37)d |

| 2005 | 1.01 (0.63–1.61) | 0.99 (0.60–1.61) | 1.24 (0.74–2.08) | 1.47 (0.84–2.56) | 1.42 (0.62–3.24) |

| 2007 | 1.28 (0.63–2.59) | 1.26 (0.64–2.52) | 1.34 (0.44–4.07) | – | – |

| 2008 | 1.02 (0.54–1.93) | 1.16 (0.59–2.28) | 1.38 (0.55–3.46) | – | – |

| 2009 | 0.95 (0.35–2.63) | 1.03 (0.42–2.58) | 1.18 (0.43–3.21) | – | – |

| 2010 | 1.32 (0.48–3.63) | 1.47 (0.50–4.36) | 1.09 (0.36–3.29) | – | – |

| 2011 | 0.89 (0.33–2.41) | 0.95 (0.34–2.65) | 1.20 (0.50–2.87) | – | – |

| 2012 | 1.20 (0.52–2.77) | 1.25 (0.52–3.00) | 1.67 (0.63–4.45) | – | – |

| 2013 | 1.98 (0.78–5.03) | 1.92 (0.79–4.65) | 2.19 (0.65–7.38) | – | – |

| 2014 | 0.93 (0.38–2.26) | 0.98 (0.41–2.33) | 0.59 (0.20–1.73) | – | – |

| Overall | 1.18 (0.95–1.47) | 1.22 (0.98–1.51) | 1.30 (1.02–1.66)d | 1.24 (0.69–2.25) | 1.83 (1.18–2.83)d |

| p-value | 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.47 | 0.01 |

| Inactivea | |||||

| 2001 | 1.67 (1.05–2.65) | 1.85 (1.16–2.94)d | 1.42 (0.91–2.21) | 1.22 (0.67–2.23) | 1.83 (0.89–3.78) |

| 2003 | 1.13 (0.70–1.84) | 1.27 (0.77–2.07) | 1.37 (0.72–2.60) | 1.68 (0.63–4.54) | 1.13 (0.57–2.25) |

| 2005 | 1.12 (0.70–1.78) | 1.36 (0.81–2.31) | 1.22 (0.72–2.09) | 0.71 (0.42–1.20) | 2.23 (1.05–4.71)d |

| 2007 | 2.91 (1.06–8.00)d | 4.36 (1.37–13.83)d | 1.92 (0.73–5.08) | – | – |

| 2008 | 1.38 (0.74–2.57) | 1.46 (0.81–2.65) | 1.82 (0.81–4.10) | – | – |

| 2009 | 0.97 (0.34–2.73) | 1.11 (0.42–2.91) | 1.28 (0.50–3.28) | – | – |

| 2010 | 0.74 (0.38–1.44) | 0.86 (0.43–1.72) | 1.17 (0.46–2.94) | – | – |

| 2011 | 0.64 (0.26–1.57) | 0.67 (0.25–1.80) | 0.93 (0.34–2.53) | – | – |

| 2012 | 0.77 (0.33–1.79) | 0.71 (0.29–1.74) | 1.03 (0.39–2.75) | – | – |

| 2013 | 1.58 (0.77–3.26) | 1.71 (0.80–3.66) | 1.83 (0.72–4.66) | – | – |

| 2014 | 1.43 (0.48–4.21) | 1.42 (0.54–3.79) | 0.75 (0.26–2.14) | – | – |

| Overall | 1.21 (0.99–1.47) | 1.34 (1.07–1.69)d | 1.33 (1.06–1.66)d | 1.02 (0.64–1.65) | 1.63 (1.08–2.47)d |

| p-value | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.93 | 0.02 |

a Compared to the active referent group.

b Incidence Rate Ratio (95% CI).

c Adjusted for age, sex, BMI, chronic conditions, smoking status, alcohol use, highest household education, household income, and race.

d Statistically significant (p < 0.05).

Discussion

Among this sample of Canadian adolescents and young adults, our fully adjusted models demonstrated a 30% increased rate of psychiatric hospitalizations in moderately active participants, and a 33% increased rate among inactive participants, compared to active participants. Additionally, the age-stratified models showed that these associations were strongest among young adults, with no significant associations found in adolescents. Contrary to our other models, moderately active young adults had higher relative rates of psychiatric hospitalizations (83%) than inactive young adults (63%). Two similar studies in Canada found significant reductions in the incidence of mental health visits by approximately 30–50% among physically active children38,39. A further two studies from Finland and Norway demonstrated reductions as high as 43% for psychosis-related hospitalizations among physically active adolescents, and another study showed 30–45% reductions in hypnotic drug prescription with increasing physical activity41–43. To our knowledge, these are the only studies to have examined the link between youth physical activity and any measure of mental healthcare utilization, with all showing some significant reductions.

This is the largest study to examine physical activity and psychiatric hospitalizations among adolescents, and the only to be conducted in young adults. Our study design allowed us to analyze eleven cycles of the same survey with high homogeneity of the sample population, sampling procedures, and measurement instruments. As shown in Table 2, few cycles alone would have been able to detect any significant associations, however, the increased precision gained through meta-analysis allowed us to elucidate this association. The CCHS employs robust sampling procedures, providing us with a highly representative sample of the Canadian population44,55. The DAD provides coverage in all acute inpatient settings in Canada, excluding Quebec, and has demonstrated high standards of data quality56,57.

Certain limitations exist within this analysis. Although the Minnesota LTPAQ has been validated for use in both adolescent and adult populations, several domains of physical activity behaviours such as active transportation, occupation, or household activities were not fully captured58. Furthermore, the categorization of active participants in the CCHS was defined using an AEE of 3.0 KKD. While this threshold may be appropriate for the adult population, it has been suggested that children and adolescents require at least 8.0 KKD to achieve health benefits59. This may partially explain the null finding observed among adolescents, as the “active” category may be over-represented by participants who were not sufficiently active, leading a diminished effect size in this age group. Additionally, adolescents also experience increased exposure to protective factors such as greater inter-personal relationships, intellectual development, sense of belonging, health literacy, social and emotional support, and access to mental health services compared to young adults18,60. As these added safety nets are no longer accessible to young adults, physical activity may be a larger component cause for protection against mental illness.

Since physical activity is a time-varying exposure that was measured only once at the time of a participant’s interview, movement between physical activity groups likely occurred, especially during the transition to early adulthood. This presents a potential source of non-differential misclassification bias, wherein participants classified as physically active may become less active, resulting in a dilution of the observed associations. Similarly, changes in time-varying confounders or the presence of unmeasured confounders could not be detected. For instance, we were unable to identify participants with early-stage or undiagnosed mental illness, which may confound the relationship between physical activity and psychiatric hospitalizations. As a result, we were unable to fully establish the directionality of this relationship and causal effects cannot be elucidated.

With the onset of mental illness overwhelmingly occurring before the age of 25, early mental illness prevention strategies are critical for fostering healthy development across the life course17,22,23. There is strong evidence to suggest that increased physical activity during adolescence and young adulthood is effective for preventing mental illness, however, levels of physical activity among Canadian children and youth have remained stable with the vast majority not meeting guidelines25,26,28,61,62. This has prompted several calls to action urging for increased cooperation between policy makers, governments, physical activity stakeholders, and communities to address the issue of persistent inactivity in Canada63. Among the barriers to decision making is a lack of policy-relevant evidence translating to economic benefits64. Within the physical activity and mental health literature, there is a disparity between studies measuring mental health through subjective scales and those assessing utilization of costly mental health services. The present study addresses this gap by demonstrating that physical activity is associated with reductions in psychiatric hospitalizations. Although hospitalizations represent a small portion of all mental healthcare utilization, the average daily cost of a mental health stay in Canada is $900, and the average hospital LOS is nearly twice in patients with a mental disorder11,12,65.

With the paucity of research on this topic, future studies exploring various sources of mental healthcare utilization, such as emergency department visits, outpatient mental health services, or prescription medications are needed. This is made possible through record linkage, allowing researchers to link readily collected data to health administrative data and examine the longitudinal impacts of physical activity on mental health services. Future studies should consider the various domains of physical activity and aim to better understand the mechanisms underlying this link. In addition, future analyses should attempt to examine outcomes by disorder type, which could provide greater insight into the levels of functional impairment experienced by individuals and lead to a greater understanding of the directionality of this relationship. With the importance of health promotion in young adults and lack of existing studies, more studies should incorporate this age group in future analyses. Although this study included a representative sample of the Canadian population, this sample was mostly homogenous with a high proportion of participants being healthy, white, and from high education households.

Overall, we found that lower levels of physical activity were associated with increased rates of psychiatric hospitalizations. The totality of prior literature suggests that physical activity among AYAs can be protective against depression and anxiety66,67; this study adds to current literature by demonstrating that mental health benefits may translate to reductions in hospitalizations as well. This study offers valuable insights for decision makers and stakeholders, but further investigation is necessary before policy recommendations can be made. Our findings lay important groundwork for future research in this area.

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

Study concept and design: M.F., S.P., P.R., and M.F.B. Data acquisition, analysis, and interpretations: M.F., S.P., and J.W. Drafting of manuscript: M.F. Revisions: S.P., P.E., and M.F.B.

Data availability

Data for this study are housed within secure facilities managed by Statistics Canada and can be accessed remotely through the Research Data Centres (https://www.statcan.gc.ca/en/microdata/data-centres/data/cphs).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was carried out in accordance with Statistics Canada Directive on Microdata Linkage and the TCPS-2 Ethical Guidelines. The methods and reporting of this manuscript were completed in accordance with the RECORD guidelines for the reporting of health administrative data.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-81273-6.

References

- 1.Lim, K. L., Jacobs, P., Ohinmaa, A. & Dewa, C. S. A new population-based measure of the economic burden of mental illness in Canada. Chronic Diseases in Canada28, (2008). [PubMed]

- 2.Sporinova, B. et al. Association of mental health disorders with health care utilization and costs among adults with chronic disease. JAMA Netw. Open2, e199910 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferrari, A. J. et al. Burden of depressive disorders by country, sex, age, and year: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease study 2010. PLoS Med.10, e1001547 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whiteford, H. A. et al. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet382, 1575–1586 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mental Health Commission of Canada. Making the Case for Investing in Mental Health in Canada. (2013).

- 6.Chartier, M. J. et al. Suicidal risk and adverse social outcomes in adulthood associated with child and adolescent mental disorders. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry67, 512–523 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen, H. et al. Impact of adolescent mental disorders and physical illnesses on quality of life 17 years later. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med160, 93–99 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Connell, J., Brazier, J., O’Cathain, A., Lloyd-Jones, M. & Paisley, S. Quality of life of people with mental health problems: A synthesis of qualitative research. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes10, (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Fekadu, W., Mihiretu, A., Craig, T. K. J. & Fekadu, A. Multidimensional impact of severe mental illness on family members: Systematic review. BMJ Open9, e032391 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lawrence, D., Kisely, S. & Pais, J. The epidemiology of excess mortality in people with mental illness. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry55, 752–760 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johansen, H., Sanmartin, C. & LHAD Research Team. Mental comorbidity and its contribution to increased use of acute care hospital services. www.statcan.gc.ca (2011).

- 12.Gandhi, S. et al. Mental health service use among children and youth in Ontario: Population-based trends over time. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry61, 119–124 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saunders, N. R. et al. Use of the emergency department as a first point of contact for mental health care by immigrant youth in Canada: A population-based study. CMAJ190, E1183–E1191 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chiu, M., Gatov, E., Fung, K., Kurdyak, P. & Guttmann, A. Deconstructing the rise in mental health–related ed visits among children and youth in Ontario. Canada. Health Affairs39, 1728–1736 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gill, P. J. et al. Prevalence, cost, and variation in cost of pediatric hospitalizations in Ontario. Canada. JAMA Network Open5, e2147447 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Twenge, J. M., Cooper, A. B., Joiner, T. E., Duffy, M. E. & Binau, S. G. Age, period, and cohort trends in mood disorder indicators and suicide-related outcomes in a nationally representative dataset, 2005–2017. Journal of Abnormal Psychology128, 185–199 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Solmi, M. et al. Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Molecular Psychiatry27, 281–295 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arnett, J. J., Žukauskiene, R. & Sugimura, K. The new life stage of emerging adulthood at ages 18–29 years: Implications for mental health. The Lancet Psychiatry1, 569–576 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson, D., Dupuis, G., Piche, J., Clayborne, Z. & Colman, I. Adult mental health outcomes of adolescent depression: A systematic review. Depression and Anxiety35, 700–716 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Compton, M. T. & Shim, R. S. Mental illness prevention and mental health promotion: when, who, and how. Psychiatric Services71, 981–983 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Purtle, J., Nelson, K. L., Counts, N. Z. & Yudell, M. Population-Based Approaches to Mental Health: History, Strategies, and Evidence. Annu. Rev. Public Health41, 201–221 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Waddell, C., McEwan, K., Shepherd, C. A., Offord, D. R. & Hua, J. M. A public health strategy to improve the mental health of Canadian children. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry50, 226–233 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malla, A. et al. Youth mental health should be a top priority for health care in Canada. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry63, 216–222 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahn, S. & Fedewa, A. L. A meta-analysis of the relationship between children’s physical activity and mental health. Journal of Pediatric Psychology36, 385–397 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Biddle, S. J. H. & Asare, M. Physical activity and mental health in children and adolescents: A review of reviews. British Journal of Sports Medicine45, 886–895 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Biddle, S. J. H., Ciaccioni, S., Thomas, G. & Vergeer, I. Physical activity and mental health in children and adolescents: An updated review of reviews and an analysis of causality. Psychology of Sport and Exercise42, 146–155 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodriguez-Ayllon, M. et al. Role of Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior in the Mental Health of Preschoolers, Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Medicine49, 1383–1410 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carter, T. et al. The effect of physical activity on anxiety in children and young people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders285, 10–21 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heinze, K. et al. Neurobiological evidence of longer-term physical activity interventions on mental health outcomes and cognition in young people: A systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews120, 431–441 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ströhle, A. et al. Physical activity and prevalence and incidence of mental disorders in adolescents and young adults. Psychological Medicine37, 1657–1666 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kwan, M., Bobko, S., Faulkner, G., Donnelly, P. & Cairney, J. Sport participation and alcohol and illicit drug use in adolescents and young adults: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Addictive Behaviors39, 497–506 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gunnell, K. E. et al. Examining the bidirectional relationship between physical activity, screen time, and symptoms of anxiety and depression over time during adolescence. Preventive Medicine88, 147–152 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Choi, K. W. et al. Assessment of Bidirectional Relationships Between Physical Activity and Depression Among Adults: A 2-Sample Mendelian Randomization Study. JAMA psychiatry76, 399–408 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pinto Pereira, S. M., Geoffroy, M.-C. & Power, C. Depressive Symptoms and Physical Activity During 3 Decades in Adult Life: Bidirectional Associations in a Prospective Cohort Study. JAMA Psychiatry71, 1373–1380 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stavrakakis, N., de Jonge, P., Ormel, J. & Oldehinkel, A. J. Bidirectional Prospective Associations Between Physical Activity and Depressive Symptoms. The TRAILS Study. Journal of Adolescent Health50, 503–508 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.ParticipACTION. The Role of the Family in the Physical Activity, Sedentary and Sleep Behaviours of Children and Youth. The 2020 ParticipACTION Report Card on Physical Activity for Children and Youth. (2020).

- 37.Colley, R. C. et al. Physical activity of Canadian children and youth, 2007 to 2015. Health Reports28, 8–16 (2017). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu, X. Y., Bastian, K., Ohinmaa, A. & Veugelers, P. Influence of physical activity, sedentary behavior, and diet quality in childhood on the incidence of internalizing and externalizing disorders during adolescence: a population-based cohort study. Annals of Epidemiology28, 86–94 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Loewen, O. K. et al. Lifestyle behavior and mental health in early adolescence. Pediatrics143, e20183307 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fimland, M. S. et al. Leisure-time physical activity and disability pension: 9 years follow-up of the HUNT Study, Norway. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports25, e558–e565 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Okkenhaug, A. et al. Physical activity in adolescents who later developed schizophrenia: A prospective case-control study from the Young-HUNT. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry70, 111–115 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sormunen, E. et al. Effects of childhood and adolescence physical activity patterns on psychosis risk - A general population cohort study. Schizophrenia3, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Kleppang, A. L., Hartz, I., Thurston, M. & Hagquist, C. Leisure-time physical activity among adolescents and subsequent use of antidepressant and hypnotic drugs: a prospective register linkage study. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry28, 177–188 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Béland, Y. Canadian Community Health Survey- Methodological overview. Health Reports13, 9–14 (2002). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Statistics Canada. User Guide: Canadian population health survey data (CCHS Annual and Focus Content) integrated with mortality (CVSD), hospitalization (DAD, NACRS, OMHRS), historical postal codes (HIST-PC), cancer (CCR), tax data (T1FF) and Census short form (CEN)- Public version. (2020).

- 46.Canadian Institute for Health Information. Data Quality Documentation, Discharge Abstract Database— Multi-Year Information. https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/dad_multi-year_en_0.pdf.

- 47.Benchimol, E. I. et al. The REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) Statement. PLoS Medicine12, e1001885 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cole, T. J., Bellizzi, M. C., Flegal, K. M. & Dietz, W. H. Papers Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ320, 1240 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vidmar, S. I., Cole, T. J. & Pan, H. Standardizing anthropometric measures in children and adolescents with functions for egen: Update. Stata Journal13, 366–378 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 50.World Health Organization. Obesity: Preventing and managing the global epidemic. (2000). [PubMed]

- 51.Richardson, M. T., Leon, A. S., Jacobs, D. R. Jr., Ainsworth, B. E. & Serfass, R. Comprehensive evaluation of the Minnesota Leisure Time Physical Activity Questionnaire. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology47, 271–281 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Slinde, F., Arvidsson, D., Sjöberg, A. & Rossander-Hulthén, L. Minnesota leisure time activity questionnaire and doubly labeled water in adolescents. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise35, 1923–1928 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 16. Preprint at (2019).

- 54.Wickham, H. et al. Welcome to the Tidyverse. Journal of Open Source Software4, 1686 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Patten, S. B. Epidemiology for Canadian Students: Principles, Methods, & Critical Appraisal- Second Edition. (Brush Education, 2018).

- 56.Roos, L. L., Gupta, S., Soodeen, R.-A. & Jebamani, L. Data Quality in an Information-Rich Environment: Canada as an Example. Canadian Journal on Aging24, 153–170 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hinds, A., Lix, L. M., Smith, M., Quan, H. & Sanmartin, C. Quality of administrative health databases in Canada: A scoping review. Canadian Journal of Public Health107, e56–e61 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Katzmarzyk, P. T. & Tremblay, M. S. Limitations of Canada’s physical activity data: Implications for monitoring trends. Applied Physiology, Nutrition and Metabolism32, S185–S194 (2007). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Canadian Fitness and Lifestyle Research Institute. Meeting guidelines. (1998).

- 60.New Brunswick Health Council. Protective factors as a path to better youth mental health. (2016).

- 61.Colley, R. C. et al. Trends in physical fitness among Canadian children and youth. Health Reports30, 3–13 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Doyon, C. Y. et al. Trends in physical fitness among Canadian adults, 2007 to 2017. Health Reports32, 3–15 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Public Health Agency of Canada. A common vision for increasing physical activity and reducing sedentary living in Canada: Let’s get moving. (2018).

- 64.van de Goor, I. et al. Determinants of evidence use in public health policy making: Results from a study across six EU countries. Health Policy121, 273–281 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Canadian Institute for Health Information. Trends in Hospital Spending, 2005–2006 to 2019–2020 — Data Tables — Series C: Average Direct Cost per Patient by Selected Functional Centre. (2021).

- 66.Schuch, F. B. et al. Physical Activity and Incident Depression: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. The American journal of psychiatry175, 631–648 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schuch, F. B. et al. Physical activity protects from incident anxiety: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Depression and anxiety36, 846–858 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data for this study are housed within secure facilities managed by Statistics Canada and can be accessed remotely through the Research Data Centres (https://www.statcan.gc.ca/en/microdata/data-centres/data/cphs).