Abstract

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) comprises neurodevelopmental disorders with wide variability in genetic causes and phenotypes, making it challenging to pinpoint causal genes. We performed whole exome sequencing on a modest, ancestrally diverse cohort of 195 families, including 754 individuals (222 with ASD), and identified 38,834 novel private variants. In 68 individuals with ASD (~30%), we identified 92 potentially pathogenic variants in 73 known genes, including BCORL1, CDKL5, CHAMP1, KAT6A, MECP2, and SETD1B. Additionally, we identified 158 potentially pathogenic variants in 120 candidate genes, including DLG3, GABRQ, KALRN, KCTD16, and SLC8A3. We also found 34 copy number variants in 31 individuals overlapping known ASD loci. Our work expands the catalog of ASD genetics by identifying hundreds of variants across diverse ancestral backgrounds, highlighting convergence on nervous system development and signal transduction. These findings provide insights into the genetic underpinnings of ASD and inform molecular diagnosis and potential therapeutic targets.

Subject terms: Autism spectrum disorders, Medical genomics

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a collection of neurodevelopmental disorders manifested by impaired social communication, repetitive behaviors, and restricted interests1. In addition to these primary symptoms, individuals with ASD often experience comorbidities like intellectual disability, anxiety, depression, attention disorders, and epilepsy2. About 1 in 36 children has been identified with ASD according to the latest estimates from CDC’s Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring (ADDM) Network3.

ASD etiology includes a substantial genetic component, with a large population-based study including 2 million individuals suggesting that approximately 80% of the variation in the phenotype is attributable to genetic factors4. Recent genetic analyses have uncovered that rare variations disrupting gene function, identified through whole exome and whole genome sequencing, have large effect sizes on the disorder5–7. However, the genetic variants identified to date only account for a small fraction of the overall disease burden8, and each of the currently known ASD genes accounts for less than ~2% of cases9. Although hundreds of ASD susceptibility genes have been identified, research suggests that there may be 400–1000 genes associated with ASD susceptibility10,11. Thus, fully understanding the genetic architecture of ASD will require continuous efforts to sequence samples from ASD cohorts. Importantly, the majority of studies are focused on single ancestries—most frequently European ancestry—which limits genetic discovery, introduces bias, and misses ancestry-specific effects, reducing generalizability.

We enrolled a modest familial ASD cohort from diverse ancestral backgrounds and performed whole exome sequencing (WES) on a total of 754 individuals from 195 families, including 222 probands with ASD and their family members without ASD. We focused on spontaneous and inherited rare deleterious variants as pathogenic candidates. In total, we identified 92 potentially pathogenic variants in 73 genes that have been previously implicated in ASD or other neurodevelopmental disorders, and 158 potentially pathogenic coding variants in 120 candidate ASD genes. We also identified 34 copy number variants (CNVs) in all individuals with ASD that overlap with known loci. Through this study in a multi-ancestral ASD cohort, we identified potentially pathogenic variants in known ASD or neurodevelopmental disease genes enriched for nervous system development and neurogenesis and novel genes enriched for regulation of signal transduction. Our study underscores the significance of genetic diversity in ASD research and highlights the roles of the identified genes in brain development.

Results

Clinical characteristics of the ASD cohort

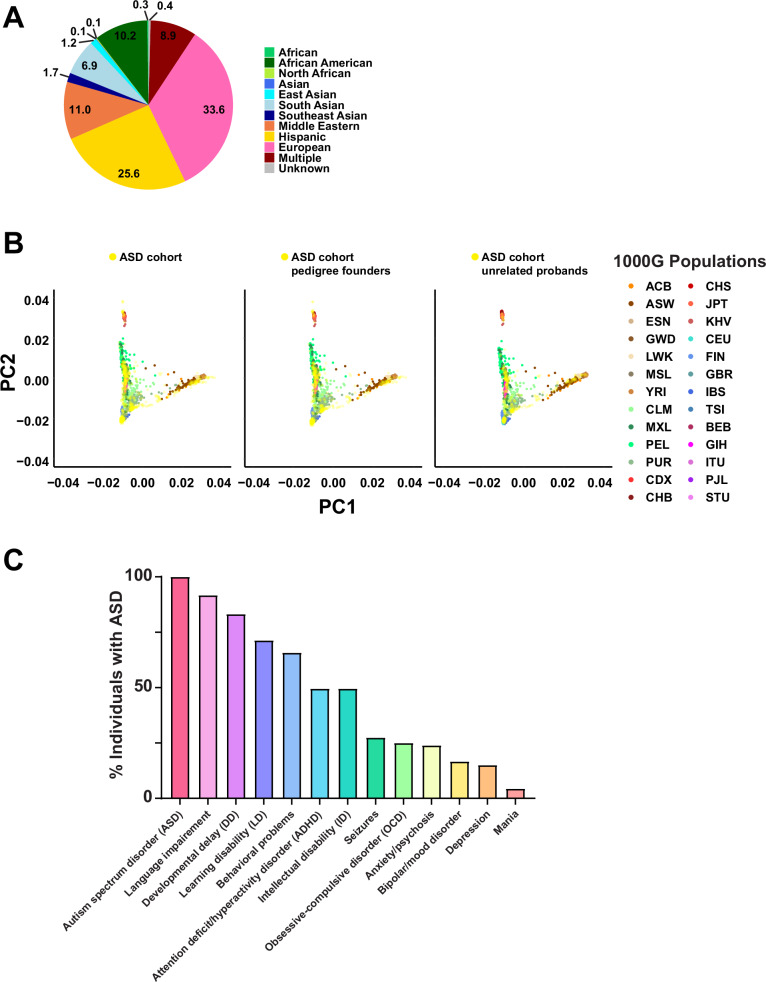

A total of 195 simplex and multiplex families who have at least one child diagnosed with ASD were enrolled in our study (Supplementary Data 1). The enrolled families represent diverse ancestral backgrounds, including African American, Asian, Hispanic, Middle Eastern, Native American, and European (Fig. 1A). We used principal component analysis (PCA) to explore the ancestry of the families in the cohort (Fig. 1B). Our cohort clustered across the different subpopulations of the 1000 Genomes project (1000G)12. Given that our cohort does not comprise a specific population, this finding is consistent with expectations. The cohort included a total of 222 individuals with ASD and their family members without ASD (165 fathers, 188 mothers, 5 grandmothers, and 174 siblings), and we observed a male-to-female ratio of 2.7:1 (162 males, 60 females) among individuals with ASD. This is slightly lower than the more recent estimates of ~3:113,14 or previous estimates of ~4:113. Parental age, which is a possible risk factor for ASD15, was not significantly different at the time of birth of individuals with ASD compared to offspring with no ASD (Supplementary Fig. 1). A standardized medical questionnaire was collected from each of the 195 participating families and reviewed along with available medical records for the presence of clinical comorbidities commonly associated with ASD and other neurodevelopmental disorders, including attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), language delay or impairment, cognitive impairment including intellectual disability, specific learning disability, aggression or challenging behaviors, mood disorders (i.e., anxiety, depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), bipolar disorder), seizures, and sleep problems. There were 222 individuals diagnosed with ASD and 532 participants without ASD. Of those individuals with ASD where complete information for a specific phenotype was available, 91.72% had language impairment, 83.21% had developmental delay, 71.31% had learning disability, 65.81% had behavioral problems, 49.55% had ADHD, 49.54% had intellectual disability, 27.45% had seizures, and 25% had OCD (Fig. 1C). Other medical comorbidities were seen at lower frequencies, including environmental and food allergies, and respiratory, gastrointestinal, and vision problems. Demographics and clinical information for the cohort are provided in Fig. 1, Table 1 and Supplementary Data 1.

Fig. 1. Ancestral diversity and phenotypic spectrum of the ASD cohort.

A Pie chart depicting the ancestral diversity of the ASD cohort. Multiple refers to individuals with multiple ancestries. B Principal component analysis (PCA) of the ASD cohort samples combined with the 1000G populations, using the entire ASD cohort (left), the pedigree founders (middle), or the unrelated probands (right). The ASD cohort is represented in yellow. The 1000G populations are: ACB African Caribbeans in Barbados, ASW Americans of African Ancestry in Southwest USA, ESN Esan in Nigeria, GWD Gambian in Western Divisions in Gambia, LWK Luhya in Webuye, Kenya, MSL Mende in Sierra Leone, YRI Yoruba in Ibadan, Nigeria, CLM Colombians from Medellin, Colombia, MXL Mexican Ancestry from Los Angeles, USA, PEL Peruvians from Lima, Peru, PUR Puerto Ricans from Puerto Rico, CDX Chinese Dai in Xishuangbanna, China, CHB Han Chinese in Beijing, China, CHS Southern Han Chinese, JPT Japanese in Tokyo, Japan, KHV Kinh in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, CEU Utah Residents (CEPH) with Northern and Western European Ancestry, FIN Finnish in Finland, GBR British in England and Scotland, IBS Iberian Population in Spain, TSI Toscani in Italia, BEB Bengali from Bangladesh, GIH Gujarati Indian from Houston, Texas, ITU Indian Telugu from the UK, PJL Punjabi from Lahore, Pakistan, STU Sri Lankan Tamil from the UK. Population abbreviations are also defined in Supplementary Data 11. C The prevalence of neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric conditions in the ASD cohort. ASD was diagnosed in all 222 probands (100%). Language impairment was the most commonly reported phenotype (91.72%).

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical information for the ASD cohort

| A. Demographics | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of individuals | All | Males | Females |

| Cohort (N) | 754 | 411 | 343 |

| Parents (N) | 353 | 165 | 188 |

| Age (mean, years) | 44.1 | 45.3 | 43.0 |

| Age (median, years) | 44 | 44 | 43 |

| Non-ASD siblings (N) | 174 | 82 | 92 |

| Age (mean, years) | 15.8 | 15.3 | 16.2 |

| Age (median, years) | 15 | 13.5 | 16 |

| Paternal age at birth (mean, years) | 31.5 | 31.4 | 31.5 |

| Maternal age at birth (mean, years) | 28.9 | 29.6 | 28.4 |

| Individuals with ASD (N) | 222 | 162 | 60 |

| Age (mean, years) | 14.5 | 14.3 | 15.1 |

| Age (median, years) | 13 | 12 | 14 |

| Paternal age at birth (mean, years) | 32.4 | 32.2 | 33.0 |

| Maternal age at birth (mean, years) | 30.0 | 30.2 | 29.4 |

| B. Ancestry | ||

|---|---|---|

| Ancestry | Number of individuals | % of individuals |

| African | 2 | 0.3 |

| African American | 77 | 10.2 |

| North African | 1 | 0.1 |

| Asian | 1 | 0.1 |

| East Asian | 9 | 1.2 |

| South Asian | 52 | 6.9 |

| Southeast Asian | 13 | 1.7 |

| Middle Eastern | 83 | 11.0 |

| Hispanic | 193 | 25.6 |

| European | 253 | 33.6 |

| Multiple | 67 | 8.9 |

| Unknown | 3 | 0.4 |

| C. Clinical information | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical symptoms | Number of individuals tested | Number of individuals with phenotype | % of individuals with ASD |

| Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) | 222 | 222 | 100.00 |

| Language impairment | 145 | 133 | 91.72 |

| Developmental delay (DD) | 137 | 114 | 83.21 |

| Learning disability (LD) | 122 | 87 | 71.31 |

| Behavioral problems | 117 | 77 | 65.81 |

| Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) | 111 | 55 | 49.55 |

| Intellectual disability (ID) | 109 | 54 | 49.54 |

| Seizures | 102 | 28 | 27.45 |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) | 96 | 24 | 25.00 |

| Anxiety/psychosis | 92 | 22 | 23.91 |

| Bipolar/mood disorder | 90 | 15 | 16.66 |

| Depression | 93 | 14 | 15.05 |

| Mania | 91 | 4 | 4.40 |

Age refers to current age in 2024. Multiple refers to individuals with multiple ancestries.

ASD autism spectrum disorder, DD developmental delay, LD learning disability, ADHD attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, ID intellectual disability, OCD obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Whole exome sequencing and variant discovery in the ASD cohort

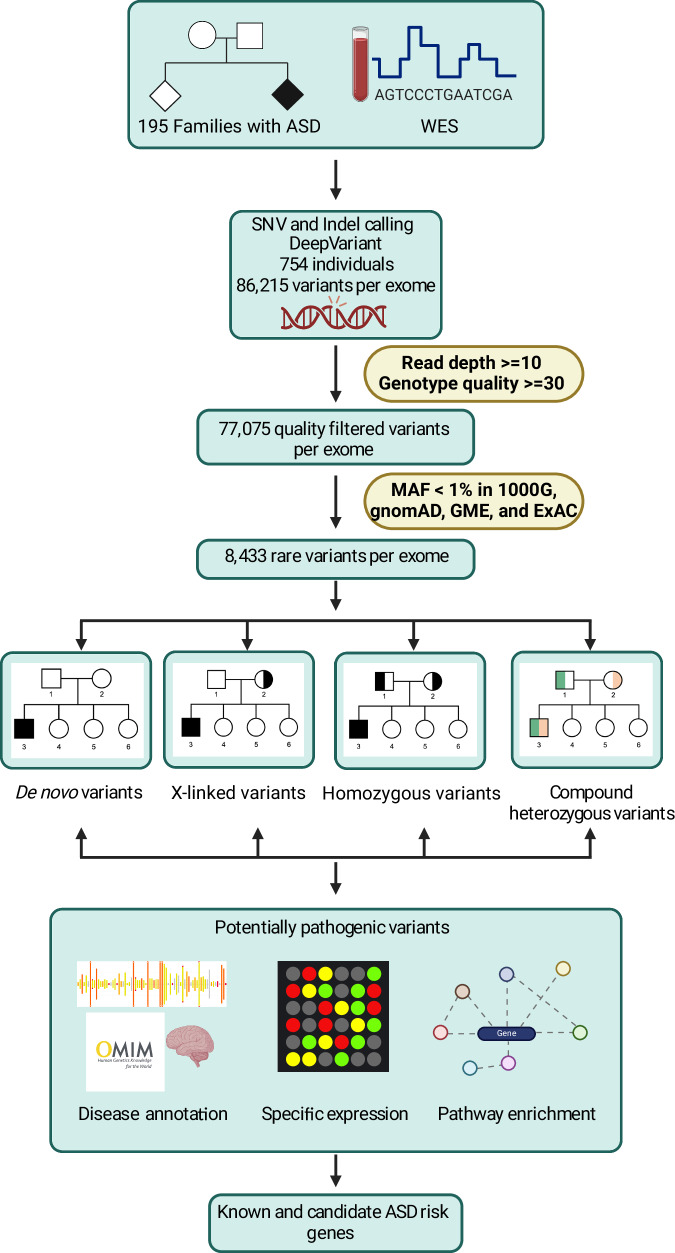

We performed WES on samples from 754 individuals, including 222 individuals with ASD. The average read depth was 46X, with no differences in depth of sequencing with respect to phenotypic status, sex, or family relationships (Supplementary Fig. 2A–C). On average, 99.29% and 93.9% of bases were covered at a mean read depth of at least 10X and 20X, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 2D). An average of 86,215 total variants were identified per exome, of which an average of 73,132 were single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and 13,083 were insertions or deletions (indels) (Supplementary Data 2). After applying read depth and quality filters, 77,075 variants per exome remained, of which an average of 65,907 were SNVs and 11,168 were indels (Supplementary Data 2). A detailed summary of our WES data processing and variant filtration pipeline is shown in Fig. 2. We filtered for rare variants with a minor allele frequency (MAF) < 1% in all annotated population databases ((1000G)12, Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD)16,17, the Greater Middle East Variome project (GME)18, and The Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC)19), identifying on average 8433 rare variants per exome, of which 7002 were heterozygous and 1431 were homozygous (Supplementary Data 2). We defined potentially damaging variants as the subset of rare exonic or splice site (referred to as coding) variants that are also predicted to be damaging by at least 1 of the 2 algorithms used: SIFT and PolyPhen-2 HumVar. There was no significant difference in the number of potentially damaging variants between sexes for individuals with ASD in the cohort (Supplementary Fig. 3). To assess for an excess of potentially damaging variants in individuals with ASD compared to individuals without ASD, we performed a burden analysis. We found no difference between individuals with or without ASD in the burden of rare variants with total coding, nondisrupting, missense damaging, or loss of function effects (Supplementary Fig. 4). This outcome is expected, given our modest sample size and the fact that ASD comprises individually rare diseases with genetic heterogeneity, caused by rare alleles of substantial impact. Therefore, observing an excess of these variations requires studying much larger cohorts capable of capturing this heterogeneity. We discovered an average of 5959 novel variants per exome that have not been reported in any of the populations in the public databases that we used for annotation (Supplementary Data 2). Furthermore, we found an average of 52 novel variants per individual that were private (71 for parents, 34 for offspring), meaning they have not been reported in any of the annotated populations and they were not present in any other individual in the cohort (Supplementary Data 3). In total, there were 38,834 novel private variants across all individuals in the cohort (Supplementary Data 3). As expected, more private variants were present in parents compared with offspring (Supplementary Fig. 5). We identified an average of 15 (20 for parents, 9 for offspring) private coding variants per exome, of which an average of 6 (8 for parents, 4 for offspring) per exome were nonsynonymous and predicted to be potentially damaging by at least 1 of the 2 algorithms used, SIFT and PolyPhen-2 HumVar (Supplementary Data 3).

Fig. 2. Overview diagram of study analyses.

Whole exome sequencing (WES) was performed on 754 individuals from 195 families, including 222 probands with ASD and their family members without ASD (165 fathers, 188 mothers, 5 grandmothers, and 174 siblings). Single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and small insertions or deletions (indels) were called using DeepVariant. Variant quality filtering was performed as described in the Materials and Methods. Rare de novo or inherited (X-linked, homozygous, and compound heterozygous) variants were annotated to identify potentially pathogenic variants. Risk genes were prioritized by disease annotation, specific expression, and pathway enrichment. MAF minor allele frequency. This figure was created with BioRender.com.

Identification of candidate ASD variants

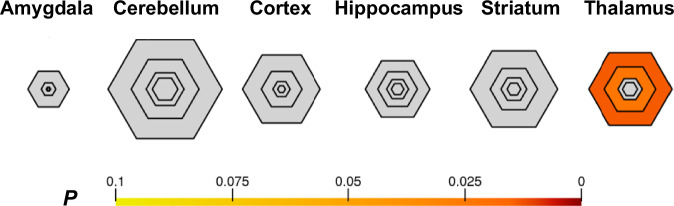

For candidate ASD variant discovery, we initially focused on rare nonsynonymous exonic or splice site variants that were either de novo or segregated with ASD in the family under homozygous, compound heterozygous, or X-linked inheritance. We identified an average of 4 de novo variants (2 coding) per offspring with ASD (Supplementary Data 4). In addition, we identified an average of 155 inherited homozygous variants (38 coding) and 10 compound heterozygous variants in 3 genes per offspring with ASD (Supplementary Data 4). We also identified an average of 16 recessive X-linked variants in male offspring with ASD (8 coding) (Supplementary Data 4). We did not find a significant correlation between the number of de novo variants and maternal or paternal age at birth of an offspring with ASD (Supplementary Fig. 6). In total, we identified 630 genes harboring 1503 rare nonsynonymous exonic or splice site variants that are predicted to be potentially damaging by at least 1 of the 2 algorithms used, SIFT and PolyPhen-2 HumVar (Supplementary Data 5). The shared symptoms among individuals with ASD suggest the existence of a functional convergence downstream of loci that contribute to the condition. To investigate if there is selective expression of at least some of these 630 genes in different brain regions, we conducted specific expression analysis (SEA) using human transcriptomics data from the BrainSpan collection20. We found that genes with variants detected in the individuals with ASD in our cohort were enriched in the thalamus (p = 0.014) (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Data 6), including AR, ATP1A3, SCN1A, and SLC7A3.

Fig. 3. Enrichment of the identified ASD genes in the thalamus.

Bullseye plot of specific expression analysis (SEA) of genes harboring the prioritized variants across brain regions and development. SEA revealed that genes with possibly damaging variants detected in the ASD cohort were enriched during young adulthood in the thalamus. The color bar shows Benjamini–Hochberg corrected p.

Variants in known ASD or neurodevelopmental disease genes

Table 2 summarizes the potentially pathogenic variants in 73 known ASD or neurodevelopmental disease genes for each individual with ASD after variant prioritization. Out of these genes, 40 are reported in the Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative (SFARI) Gene database21, and the rest are OMIM-annotated disease genes associated with relevant phenotypes, including neurodevelopmental disorder, intellectual disability, developmental delay, and epilepsy. These genes were significantly enriched in pathways involving nervous system development, neurogenesis, and neuronal differentiation (Supplementary Data 7). We identified 92 unique variants in 68 individuals with ASD (~1–3 per individual). Twenty-six individuals with ASD had coding variants in 19 syndromic ASD genes: CDKL5 (3 probands), DMD (3 probands), BCORL1 (2 probands), and SETD1B (2 probands). ARID1B, ATP1A3, CHAMP1, CNOT1, FRMPD4, HUWE1, KAT6A, KMT2C, MECP2, PACS2, PHF21A, SCN1A, SLC6A1, SMARCA2, TFE3, and ZMYM3 are other syndromic ASD genes harboring variants in single probands. Twenty-three individuals with ASD had coding variants in 21 nonsyndromic ASD genes having a SFARI Gene21 score of 1 or 2: NEXMIF (2 probands) and NLGN4X (2 probands). AR, ARHGEF10, ASTN2, AUTS2, BIRC6, CACNA1F, DLG4, DYNC1H1, IL1RAPL1, ITPR1, OPHN1, PCDHA5, SKI, SLC7A3, SYN1, TOP2B, WNK3, YEATS2, and ZC3H4 are other ASD genes harboring variants in single probands. Thirty-two probands had other coding variants in 33 neurodevelopmental disease genes, with 2 genes—ADGRV1 and ATP7A—having variants in 2 probands each. ACSL4, ARHGAP31, ARMC9, ATP2B3, ATP6AP2, BCAP31, CCDC22, CHD5, DBR1, DCTN1, DHX37, FGD1, HDAC6, IGBP1, KIF1C, MINPP1, MPDZ, NOTCH1, NRG1, OBSL1, PIGG, PLXNA1, SAMD9L, SCN3A, SLC13A3, SRPX2, TMEM151A, TNRC6A, TRIM71, TRNT1, and ZNF148 are other neurodevelopmental disease genes harboring variants in single probands. Three probands had coding variants in two neurodevelopmental genes each: MC-159-5 (ADGRV1 and KIF1C), MC-161-3 (MPDZ and NRG1), and MC-172-3 (OBSL1 and SAMD9L).

Table 2.

Potentially pathogenic variants in known ASD and neurological disease genes identified in individuals with ASD from the cohort

| Individual with ASD | Inheritance | Variant(s) | Variant type | Gene | Mutation | Relevant OMIM Phenotype | SFARI score | pLI score | LOEUF score | Z score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JC_19_3 | De novo | chrX:154030912-154030912:G:A | nonsynonymous SNV | MECP2 | p.R318C | Rett syndrome, Encephalopathy, Intellectual developmental disorder | 1S | 0.89382 | 0.407 | 2.893 |

| JC_20_3 | X-Linked | chrX:32389610-32389610:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | DMD | p.R129H | – | S | 1 | 0.154 | 10.694 |

| JC_22_4 | De novo | chr3:125233501-125233501:G:A | stopgain | ZNF148 | p.Q409X | Global developmental delay, absent or hypoplastic corpus callosum | – | 0.99997 | 0.103 | 4.9945 |

| JC_24_3 | Inherited homozygous | chr12:124952446-124952446:C:G | nonsynonymous SNV | DHX37 | p.R940S | Neurodevelopmental disorder | – | 0.99252 | 0.289 | 5.8911 |

| JC_25_3 | De novo | chr3:4733157-4733157:A:T | nonsynonymous SNV | ITPR1 | p.S1701C | Gillespie syndrome, Spinocerebellar ataxia | 2 | 1 | 0.134 | 9.9326 |

| JC_27_3 | Inherited homozygous | chr16:58543412-58543412:-:A | frameshift insertion | CNOT1 | p.L1544Sfs*22 | Vissers-Bodmer syndrome, Holoprosencephaly | 2S | 1 | 0.038 | 10.279 |

| JC_32_3 | De novo | chr3:11025863-11025863:A:G | clinvar AN | SLC6A1 | p.N136D | Intellectual developmental disorder | 1S | 0.99993 | 0.15 | 5.0491 |

| MC_003_3 | De novo | chr1:6142418-6142418:T:C | nonsynonymous SNV | CHD5 | p.K744R | Parenti-Mignot neurodevelopmental syndrome | – | 1 | 0.157 | 8.4428 |

| MC_004_3 | De novo | chr19:41986183-41986183:C:G | nonsynonymous SNV | ATP1A3 | p.C146S | Alternating hemiplegia, CAPOS syndrome | 2S | 1 | 0.062 | 6.3973 |

| MC_005_3 | X-Linked | chrX:47574709-47574709:G:C | nonsynonymous SNV | SYN1 | p.Q458E | – | 1 | 0.99216 | 0.251 | 3.8157 |

| MC_005_3 | X-Linked | chrX:18595364-18595364:A:G | nonsynonymous SNV | CDKL5 | p.H254R | Developmental and epileptic encephalopathy | 1S | 0.99932 | 0.226 | 4.9513 |

| MC_014_3 | Inherited homozygous | chr4:539215-539215:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | PIGG | p.T800M | Neurodevelopmental disorder | – | 5.4258E−15 | 0.988 | 1.615 |

| MC_017_3 | De novo | chr2:165991869-165991872:CTCA:- | frameshift deletion | SCN1A | p.S1801Rfs*56 | Developmental and epileptic encephalopathy, Dravet syndrome | 1S | 1 | 0.071 | 8.5198 |

| MC_019_3a | De novo | chr3:32890881-32890881:G:C | nonsynonymous SNV | TRIM71 | p.S1801Rfs*56 | Hydrocephalus | – | 0.99969 | 0.172 | 4.6883 |

| MC_022_3a | X-Linked | chrX:70134643-70134643:G:T | nonsynonymous SNV | IGBP1 | p.Q103H | Impaired intellectual development | – | 0.98274 | 0.242 | 3.2578 |

| MC_024_3 | Inherited homozygous | chr3:25664257-25664257:C:G | nonsynonymous SNV | TOP2B | p.G14A | – | 2 | 0.99989 | 0.247 | 6.9742 |

| MC_024_3 | X-Linked | chrX:78014707-78014707:A:G | nonsynonymous SNV | ATP7A | p.T740A | Occipital horn syndrome, Menkes disease | – | 0.99983 | 0.216 | 5.468 |

| MC_025_3 | X-Linked | chrX:130016202-130016202:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | BCORL1 | p.H1144Y | Shukla-Vernon syndrome | S | 0.99999 | 0.152 | 5.6731 |

| MC_025_4 | X-Linked | chrX:130016202-130016202:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | BCORL1 | p.H1144Y | Shukla-Vernon syndrome | S | 0.99999 | 0.152 | 5.6731 |

| MC_027_3 | X-Linked | chrX:29955423-29955423:A:C | nonsynonymous SNV | IL1RAPL1 | p.E565A | Intellectual developmental disorder | 2 | 0.99886 | 0.197 | 4.3584 |

| MC_027_3 | X-Linked | chrX:49248232-49248232:G:C | nonsynonymous SNV | CCDC22 | p.E378D | Ritscher-Schinzel syndrome | – | 0.99979 | 0.123 | 4.5588 |

| MC_028_3 | X-Linked | chrX:49222958-49222958:A:C | nonsynonymous SNV | CACNA1F | p.F686V | – | 2 | 1.2337E−05 | 0.448 | 5.4046 |

| MC_032_3 | Inherited homozygous | chr2:165090971-165090971:G:A | nonsynonymous SNV | SCN3A | p.P1679S | Developmental and epileptic encephalopathy | – | 1 | 0.174 | 7.6338 |

| MC_042_3 | Compound heterozygous | chr14:101988835-101988835:G:A | nonsynonymous SNV | DYNC1H1 | p.G951R | – | 1 | 1 | 0.08 | 13.319 |

| MC_042_3 | Compound heterozygous | chr14:102018473-102018473:G:A | nonsynonymous SNV | DYNC1H1 | p.V2734M | – | 1 | 1 | 0.08 | 13.319 |

| MC_044_3 | X-Linked | chrX:153723526-153723526:G:A | nonsynonymous SNV | BCAP31 | p.H47Y | Cerebral hypomyelination | – | 0.43366 | 0.65 | 2.2884 |

| MC_045_3 | X-Linked | chrX:153556212-153556212:G:A | nonsynonymous SNV | ATP2B3 | p.R741H | Spinocerebellar ataxia | – | 0.99945 | 0.222 | 4.9998 |

| MC_053_3 | Inherited homozygous | chr20:46613719-46613719:G:C | nonsynonymous SNV | SLC13A3 | p.R40G | Leukoencephalopathy | – | 9.4522E−07 | 0.834 | 2.2133 |

| MC_060_3 | X-Linked | chrX:71249094-71249094:G:A | nonsynonymous SNV | ZMYM3 | p.R516C | Intellectual developmental disorder | S | 1 | 0.106 | 6.0468 |

| MC_063_4 | Compound heterozygous | chr3:119414252-119414252:G:A | nonsynonymous SNV | ARHGAP31 | p.G775S | Adams-Oliver syndrome | – | 0.99999 | 0.192 | 6.2345 |

| MC_063_4 | Compound heterozygous | chr3:119415525-119415525:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | ARHGAP31 | p.A1199V | Adams-Oliver syndrome | – | 0.99999 | 0.192 | 6.2345 |

| MC_064_3 | X-Linked | chrX:18625233-18625233:G:C | nonsynonymous SNV | CDKL5 | p.D828H | – | 1S | 0.99932 | 0.226 | 4.9513 |

| MC_069_3a | De novo | chr11:66295148-66295148:G:A | nonsynonymous SNV | TMEM151A | p.R301H | Episodic kinesigenic dyskinesia | – | 0.0029247 | 0.943 | 1.7136 |

| MC_070_5 | X-Linked | chrX:74743416-74743416:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | NEXMIF | p.D381N | Intellectual developmental disorder | 1 | – | – | – |

| MC_073_3 | Compound heterozygous | chr3:3147641-3147641:G:C | nonsynonymous SNV | TRNT1 | p.D312H | Developmental delay | – | 0.00015886 | 0.876 | 1.9533 |

| MC_073_3 | Compound heterozygous | chr3:3148141-3148141:-:A | frameshift insertion | TRNT1 | p.K413Efs*34 | Developmental delay | – | 0.00015886 | 0.876 | 1.9533 |

| MC_081_4 | X-Linked | chrX:74742674-74742674:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | NEXMIF | p.R628Q | Intellectual developmental disorder | 1 | – | – | – |

| MC_088_4 | Compound heterozygous | chr2:32467973-32467973:A:G | nonsynonymous SNV | BIRC6 | p.H1881R | – | 2 | 1 | 0.104 | 12.544 |

| MC_088_4 | Compound heterozygous | chr2:32597936-32597936:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | BIRC6 | p.R4600C | – | 2 | 1 | 0.104 | 12.544 |

| MC_099_3a | De novo | chr17:7218589-7218589:G:T | nonsynonymous SNV | DLG4 | p.P24T | Intellectual developmental disorder | 1 | 0.99954 | 0.238 | 5.4593 |

| MC_102_3a | De novo | chr1:2229037-2229037:T:G | nonsynonymous SNV | SKI | p.F91V | Shprintzen-Goldberg syndrome | 1 | 0.99901 | 0.194 | 4.3963 |

| MC_103_3 | Compound heterozygous | chr9:116425970-116425970:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | ASTN2 | p.E353K | – | 2 | 0.99971 | 0.246 | 6.1231 |

| MC_103_3 | Compound heterozygous | chr9:116426065-116426065:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | ASTN2 | p.R321Q | – | 2 | 0.99971 | 0.246 | 6.1231 |

| MC_110_3 | X-Linked | chrX:54250099-54250099:G:A | nonsynonymous SNV | WNK3 | p.R870W | – | 2 | 0.99999 | 0.191 | 6.2565 |

| MC_111_3 | De novo | chr7:70766248-70766248:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | AUTS2 | p.H535Y | Intellectual developmental disorder | 1 | 0.99934 | 0.253 | 5.7821 |

| MC_112_3a | De novo | chr8:41933512-41933512:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | KAT6A | p.D1570N | Arboleda-Tham syndrome | 2S | 1 | 0.069 | 8.6737 |

| MC_116_3 | De novo | chr2:74370632-74370632:A:T | nonsynonymous SNV | DCTN1 | p.I212N | Neuronopathy, Perry syndrome | – | 0.084251 | 0.364 | 5.8791 |

| MC_117_3 | X-Linked | chrX:31121880-31121880:T:A | nonsynonymous SNV | DMD | p.M608L | – | S | 1 | 0.154 | 10.694 |

| MC_117_4 | X-Linked | chrX:31121880-31121880:T:A | nonsynonymous SNV | DMD | p.M608L | – | S | 1 | 0.154 | 10.694 |

| MC_118_3 | X-Linked | chrX:68053801-68053801:T:C | nonsynonymous SNV | OPHN1 | p.D723G | Intellectual developmental disorder | 2 | 0.99985 | 0.161 | 4.8611 |

| MC_120_3 | Compound heterozygous | chr6:156778045-156778045:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | ARID1B | p.S39F | Intellectual developmental disorder | 1S | 1 | 0.102 | 8.4054 |

| MC_120_3 | Compound heterozygous | chr6:157201357-157201357:C:G | nonsynonymous SNV | ARID1B | p.P878R | Intellectual developmental disorder | 1S | 1 | 0.102 | 8.4054 |

| MC_120_3 | X-Linked | chrX:48814732-48814732:G:A | nonsynonymous SNV | HDAC6 | p.A331T | Hydrocephaly | – | 1 | 0.072 | 5.9451 |

| MC_124_6 | De novo | chr13:114324638-114324638:G:T | stopgain | CHAMP1 | p.E266X | Neurodevelopmental disorder | 1S | 0.99197 | 0.271 | 4.0836 |

| MC_126_3 | X-Linked | chrX:54455715-54455715:G:A | nonsynonymous SNV | FGD1 | p.R638C | Intellectual developmental disorder | – | 0.9997 | 0.196 | 4.9187 |

| MC_134_3a | De novo | chr5:140823339-140823339:C:A | nonsynonymous SNV | PCDHA5 | p.L522M | – | 2 | 5.8373E−08 | 0.879 | 2.0539 |

| MC_136_3 | X-Linked | chrX:70928613-70928613:T:C | nonsynonymous SNV | SLC7A3 | p.S184G | – | 2 | 0.99614 | 0.182 | 3.7525 |

| MC_138_3 | X-Linked | chrX:5893394-5893394:G:A | nonsynonymous SNV | NLGN4X | p.T625I | Intellectual developmental disorder | 1 | 0.99267 | 0.249 | 3.8359 |

| MC_138_4 | X-Linked | chrX:5893394-5893394:G:A | nonsynonymous SNV | NLGN4X | p.T625I | Intellectual developmental disorder | 1 | 0.99267 | 0.249 | 3.8359 |

| MC_140_3 | De novo | chr16:24776966-24776966:C:A | nonsynonymous SNV | TNRC6A | p.P66H | Epilepsy | – | 1 | 0.159 | 8.3756 |

| MC_146_3 | Compound heterozygous | chr9:136509800-136509800:T:C | nonsynonymous SNV | NOTCH1 | p.T968A | Adams-Oliver syndrome | – | 1 | 0.097 | 9.1999 |

| MC_146_3 | Compound heterozygous | chr9:136522960-136522960:G:A | nonsynonymous SNV | NOTCH1 | p.T211I | Adams-Oliver syndrome | – | 1 | 0.097 | 9.1999 |

| MC_146_3 | De novo | chr12:121806064-121806064:C:- | frameshift deletion | SETD1B | p.V169Sfs*46 | Intellectual developmental disorder | 2S | 1 | 0.151 | 6.7395 |

| MC_148_3 | De novo | chr14:105381945-105381945:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | PACS2 | p.R434W | Developmental and epileptic encephalopathy | S | 0.99583 | 0.279 | 5.4113 |

| MC_148_3 | X-Linked | chrX:67546365-67546365:C:G | nonsynonymous SNV | AR | p.R407G | Neuropathy | 2 | 0.98837 | 0.291 | 4.2459 |

| MC_154_3a | X-Linked | chrX:109674452-109674452:T:C | nonsynonymous SNV | ACSL4 | p.S359G | Intellectual developmental disorder | – | 0.98103 | 0.306 | 4.1113 |

| MC_154_3a | X-Linked | chrX:18604102-18604102:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | CDKL5 | p.T393I | Developmental and epileptic encephalopathy | 1S | 0.99932 | 0.226 | 4.9513 |

| MC_155_3 | X-Linked | chrX:77989260-77989260:T:C | nonsynonymous SNV | ATP7A | p.I213T | Occipital horn syndrome, Menkes disease | – | 0.99983 | 0.216 | 5.468 |

| MC_156_3a | De novo | chr2:231270991-231270991:C:- | frameshift deletion | ARMC9 | p.L344Ffs*46 | Joubert syndrome | – | 6.2032E−17 | 1.053 | 1.2891 |

| MC_158_3a | De novo | chr19:47081616-47081616:A:G | nonsynonymous SNV | ZC3H4 | p.F446S | – | 2 | 1 | 0.054 | 6.8501 |

| MC_158_3a | De novo | chr9:2056699-2056699:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | SMARCA2 | p.R401C | Nicolaides-Baraitser syndrome | 1S | 1 | 0.203 | 7.6947 |

| MC_159_3 | Inherited homozygous | chr5:90694224-90694224:G:A | nonsynonymous SNV | ADGRV1 | p.A2490T | Usher syndrome | – | – | – | – |

| MC_159_5 | De novo | chrX:49038391-49038391:G:C | nonsynonymous SNV | TFE3 | p.R91G | Intellectual developmental disorder | S | 0.97985 | 0.29 | 3.5174 |

| MC_159_5 | Inherited homozygous | chr17:5004866-5004866:G:A | nonsynonymous SNV | KIF1C | p.R344H | Spastic ataxia | – | 0.71767 | 0.341 | 5.5201 |

| MC_159_5 | Inherited homozygous | chr5:90694224-90694224:G:A | nonsynonymous SNV | ADGRV1 | p.A2490T | Usher syndrome | – | – | – | – |

| MC_160_3 | De novo | chr3:183715186-183715186:-:A | frameshift insertion | YEATS2 | p.E10Rfs*5 | Epilepsy | 2 | 0.99639 | 0.28 | 6.5648 |

| MC_160_3 | De novo | chr3:127012021-127012021:A:T | nonsynonymous SNV | PLXNA1 | p.T726S | Dworschak-Punetha neurodevelopmental syndrome | – | 0.99951 | 0.262 | 7.2148 |

| MC_161_3a | De novo | chr9:13192219-13192219:G:T | nonsynonymous SNV | MPDZ | p.T627K | Hydrocephalus | – | 5.8009E−38 | 0.89 | 2.4713 |

| MC_161_3a | De novo | chr8:32763319-32763319:A:T | nonsynonymous SNV | NRG1 | p.H303L | Schizophrenia | – | 0.99665 | 0.258 | 4.5687 |

| MC_162_3a | De novo | chr8:1898505-1898505:C:G | nonsynonymous SNV | ARHGEF10 | p.Q506E | – | 2 | 6.7739E−30 | 0.976 | 1.7165 |

| MC_163_3 | Compound heterozygous | chr7:152145253-152145253:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | KMT2C | p.G4692S | Kleefstra syndrome | 1S | 1 | 0.122 | 12.592 |

| MC_163_3 | Compound heterozygous | chr7:152311917-152311917:G:C | nonsynonymous SNV | KMT2C | p.S207C | Kleefstra syndrome | 1S | 1 | 0.122 | 12.592 |

| MC_166_3a | De novo | chr3:138163793-138163793:A:T | nonsynonymous SNV | DBR1 | p.H260Q | Encephalitis | – | 1.1785E−08 | 1.016 | 1.4986 |

| MC_166_3a | De novo | chr12:121814182-121814182:G:T | nonsynonymous SNV | SETD1B | p.C656F | Intellectual developmental disorder | 2S | 1 | 0.151 | 6.7395 |

| MC_170_3 | X-Linked | chrX:100665351-100665351:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | SRPX2 | p.A214V | Rolandic epilepsy, impaired intellectual development | – | 0.04812 | 0.538 | 3.2685 |

| MC_171_3 | De novo | chr10:87505073-87505073:A:G | nonsynonymous SNV | MINPP1 | p.Y53C | Pontocerebellar hypoplasia | – | 0.00045482 | 0.76 | 2.3797 |

| MC_171_3 | X-Linked | chrX:32463545-32463545:T:A | nonsynonymous SNV | DMD | p.N1101I | – | S | 1 | 0.154 | 10.694 |

| MC_172_3a | De novo | chr2:219562001-219562001:G:C | stopgain | OBSL1 | p.Y987X | 3-M syndrome | – | 9.9902E−26 | 0.878 | 2.4208 |

| MC_172_3a | De novo | chr7:93134087-93134087:G:A | nonsynonymous SNV | SAMD9L | p.R629W | Ataxia-pancytopenia syndrome, Spinocerebellar ataxia | – | 5.5651E−15 | 0.783 | 2.8638 |

| MC_173_3 | X-Linked | chrX:12716341-12716341:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | FRMPD4 | p.R588W | Intellectual developmental disorder | S | 1 | 0.083 | 5.536 |

| MC_174_3 | X-Linked | chrX:40599599-40599599:G:A | nonsynonymous SNV | ATP6AP2 | p.R199H | Intellectual developmental disorder | – | 0.87089 | 0.429 | 2.8047 |

| MC_174_3 | X-Linked | chrX:53583851-53583851:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | HUWE1 | p.G1743R | Intellectual developmental disorder | S | 1 | 0.060 | 11.175 |

All variants are exonic. For SFARI score, S denotes syndromic genes. LOEUF loss-of-function observed/expected upper bound fraction.

aSamples with a missing parent sample where compound heterozygous variant calling was not possible and de novo, inherited homozygous, and X-linked variant calling relied on one parent only.

Variants in new candidate ASD genes

We identified 158 potentially pathogenic coding variants in 120 candidate ASD genes after variant prioritization (Table 3). Gene ontology analysis revealed that several of the candidate ASD genes are involved in signal transduction and synaptic activity such as DLG3, GABRQ, KALRN, KCTD16, P2RX4, PKP4, SLC8A3, and TENM2 (Supplementary Data 7). Multiple variants were observed in candidate genes: ATG4A, CNGA2, CROCC, FAM47C, FRMPD3, GABRQ, GPRASP1, MAGEC3, MXRA5, OR5H1, PWWP3B, SLITRK4, TRPC5, TSPYL2, and ZNF630. Since we observed more than one potentially pathogenic variant (in known and/or novel genes) in some probands, we also ranked them according to their likelihood of causing the disease in the proband (Supplementary Data 8). In proband MC-017-3, there were two variants found in SCN1A and RBMX2. The SCN1A variant was prioritized over the RBMX2 variant as SCN1A is a known ASD gene, according to the SFARI Gene database21. Similarly, in proband MC-174-3, a variant in HUWE1, a known neurodevelopmental disease gene22,23, was ranked above a variant in another known neurodevelopmental disease gene ATP6AP224,25 based on AlphaMissense scores, and above a variant in the novel gene MTM1.

Table 3.

Potentially pathogenic variants in novel candidate ASD genes identified in individuals with ASD from the cohort

| Individual with ASD | Inheritance | Variant | Variant type | Gene | Mutation | pLI score | LOEUF score | Z score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JC_17_3 | X-Linked | chrX:8795197-8795197:C:A | stopgain | FAM9A | p.E238X | 3.0977E−12 | 1.907 | −1.2931 |

| JC_18_3 | De novo | chr12:14478361-14478361:T:C | nonsynonymous SNV | ATF7IP | p.S995P | 0.99993 | 0.213 | 5.852 |

| JC_18_3 | X-Linked | chrX:105949622-105949622:C:G | nonsynonymous SNV | NRK | p.C1467W | 0.99274 | 0.289 | 5.7027 |

| JC_20_3 | Compound heterozygous | chr1:16938440-16938440:A:G | nonsynonymous SNV | CROCC | p.E444G | 1.2656E−24 | 0.71 | 3.9469 |

| JC_20_3 | Compound heterozygous | chr1:16971564-16971564:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | CROCC | p.R1962C | 1.2656E−24 | 0.71 | 3.9469 |

| JC_20_3 | X-Linked | chrX:152945428-152945428:C:A | nonsynonymous SNV | ZNF185 | p.S95Y | 6.3026E−13 | 1.139 | 0.98434 |

| JC_20_3 | X-Linked | chrX:51744210-51744210:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | GSPT2 | p.P195L | 0.98321 | 0.24 | 3.2676 |

| JC_21_3 | X-Linked | chrX:16786504-16786504:A:G | nonsynonymous SNV | TXLNG | p.E6G | 0.99845 | 0.158 | 4.0223 |

| JC_22_3 | X-Linked | chrX:3321790-3321790:T:G | nonsynonymous SNV | MXRA5 | p.T1299P | 0.043013 | 0.398 | 5.1219 |

| JC_22_4 | Inherited homozygous | chr14:21670348-21670348:-:GT | frameshift insertion | OR4E1 | p.H197Pfs*14 | – | – | – |

| JC_22_4 | X-Linked | chrX:3321790-3321790:T:G | nonsynonymous SNV | MXRA5 | p.T1299P | 0.043013 | 0.398 | 5.1219 |

| JC_22_5 | X-Linked | chrX:3321790-3321790:T:G | nonsynonymous SNV | MXRA5 | p.T1299P | 0.043013 | 0.398 | 5.1219 |

| JC_23_3 | X-Linked | chrX:10459690-10459690:T:C | nonsynonymous SNV | MID1 | p.Q468R | 0.97967 | 0.304 | 3.8121 |

| JC_24_3 | Inherited homozygous | chr12:64875644-64875644:C:A | nonsynonymous SNV | TBC1D30 | p.S690R | 0.88919 | 0.353 | 4.4099 |

| JC_24_3 | Inherited homozygous | chr12:96324082-96324082:G:A | nonsynonymous SNV | CDK17 | p.T50M | 0.99947 | 0.222 | 5.0072 |

| JC_24_3 | Inherited homozygous | chr12:124332336-124332336:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | NCOR2 | p.R2286Q | 1 | 0.169 | 8.6249 |

| JC_24_3 | X-Linked | chrX:107601697-107601697:T:A | nonsynonymous SNV | FRMPD3 | p.F1253I | 0.00019028 | 0.476 | 4.6328 |

| JC_24_3 | De novo | chr5:139380289-139380289:G:T | nonsynonymous SNV | SLC23A1 | p.T189N | 0.023504 | 0.537 | 3.3723 |

| JC_25_3 | Inherited homozygous | chr20:53575768-53575768:C:A | nonsynonymous SNV | ZNF217 | p.C999F | 0.99995 | 0.147 | 5.0971 |

| JC_27_3 | De novo | chr3:52842931-52842931:-:A | frameshift insertion | STIMATE;STIMATE-MUSTN1 | p.L217Pfs*10 | – | – | – |

| JC_30_3 | Inherited homozygous | chr5:113433762-113433762:G:A | stopgain | TSSK1B | p.Q360X | 0.00013409 | 1.711 | 0.17385 |

| JC_30_3 | Inherited homozygous | chr15:90916239-90916239:C:T | stopgain | MAN2A2 | p.R993X | 1.4995E−10 | 0.619 | 3.9582 |

| MC_001_3 | X-Linked | chrX:141838402-141838402:T:A | stopgain | MAGEC3 | p.Y29X | 7.6566E−16 | 1.722 | −0.8259 |

| MC_001_3 | X-Linked | chrX:102657809-102657809:T:C | nonsynonymous SNV | GPRASP1 | p.M1299T | 0.31099 | 0.416 | 4.2 |

| MC_001_3 | X-Linked | chrX:70492240-70492240:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | DLG3 | p.H69Y | 0.99999 | 0.09 | 5.3454 |

| MC_001_4 | X-Linked | chrX:102657809-102657809:T:C | nonsynonymous SNV | GPRASP1 | p.M1299T | 0.31099 | 0.416 | 4.2 |

| MC_001_4 | X-Linked | chrX:70492240-70492240:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | DLG3 | p.H69Y | 0.99999 | 0.09 | 5.3454 |

| MC_009_2a | De novo | chr12:109769169-109769169:A:G | nonsynonymous SNV | FAM222A | p.N414D | 0.85124 | 0.446 | 2.7374 |

| MC_009_2a | X-Linked | chrX:143629175-143629175:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | SLITRK4 | p.R645H | 0.79447 | 0.422 | 3.3262 |

| MC_012_3 | X-Linked | chrX:106207495-106207495:G:A | nonsynonymous SNV | PWWP3B | p.R688Q | – | – | – |

| MC_014_3 | Inherited homozygous | chr15:41857344-41857344:-:T | frameshift insertion | SPTBN5 | p.A2840Gfs*5 | 8.222E−118 | 1.062 | 0.77177 |

| MC_014_3 | Inherited homozygous | chr12:49494879-49494879:A:G | nonsynonymous SNV | SPATS2 | p.N135D | 0.97239 | 0.319 | 4.2735 |

| MC_014_3 | Inherited homozygous | chr1:183553005-183553005:G:A | nonsynonymous SNV | SMG7 | p.G1114E | 0.99998 | 0.219 | 6.6005 |

| MC_014_3 | X-Linked | chrX:112811368-112811368:G:A | nonsynonymous SNV | AMOT | p.S473L | 0.99666 | 0.266 | 4.8052 |

| MC_015_3a | De novo | chr2:17781754-17781757:AAAG:- | frameshift deletion | GEN1 | p.E849Lfs*26 | 3.7299E−15 | 0.951 | 1.8067 |

| MC_015_3a | De novo | chr1:155765155-155765158:GACC:- | frameshift deletion | GON4L | p.G1439Sfs*58 | 0.9515 | 0.299 | 7.1272 |

| MC_015_3a | De novo | chr11:92761948-92761948:C:A | nonsynonymous SNV | FAT3 | p.F1254L | 0.99995 | 0.253 | 8.9265 |

| MC_016_3 | X-Linked | chrX:53082872-53082872:G:T | nonsynonymous SNV | TSPYL2 | p.G125V | 0.87393 | 0.405 | 3.1839 |

| MC_017_3 | X-Linked | chrX:130409298-130409298:A:C | nonsynonymous SNV | RBMX2 | p.K72T | 0.93892 | 0.337 | 2.7594 |

| MC_019_3a | De novo | chr11:110137378-110137378:G:A | nonsynonymous SNV | ZC3H12C | p.R246K | 0.99838 | 0.252 | 4.9736 |

| MC_022_3a | De novo | chr14:90304095-90304095:C:T | stopgain | NRDE2 | p.W282X | 2.7953E−15 | 0.768 | 2.9904 |

| MC_022_3a | X-Linked | chrX:3320746-3320746:C:G | nonsynonymous SNV | MXRA5 | p.E1647Q | 0.043013 | 0.398 | 5.1219 |

| MC_024_3 | Inherited homozygous | chr2:98822021-98822021:C:G | nonsynonymous SNV | KIAA1211L | p.R751P | 0.99694 | 0.244 | 4.3461 |

| MC_024_4 | Inherited homozygous | chr1:109717382-109717382:C:T | stopgain | GSTM5 | p.R205X | 1.1942E−07 | 1.545 | 0.18805 |

| MC_024_4 | Inherited homozygous | chr2:209694400-209694400:G:A | nonsynonymous SNV | MAP2 | p.D740N | 1 | 0.105 | 6.9461 |

| MC_025_3 | Inherited homozygous | chr20:3045704-3045704:-:GCCCC | frameshift insertion | GNRH2 | p.S116Rfs*11 | 1.3359E−07 | 1.918 | −0.9844 |

| MC_025_3 | X-Linked | chrX:48059415-48059415:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | ZNF630 | p.G343R | 0.000119 | 1.101 | 1.3081 |

| MC_025_4 | X-Linked | chrX:48059415-48059415:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | ZNF630 | p.G343R | 0.000119 | 1.101 | 1.3081 |

| MC_027_3 | X-Linked | chrX:106206166-106206166:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | PWWP3B | p.S245L | – | – | – |

| MC_032_3 | Inherited homozygous | chr1:24652527-24652527:G:T | nonsynonymous SNV | SRRM1 | p.K190N | 1 | 0.146 | 6.3753 |

| MC_034_3a | De novo | chr7:1746707-1746707:G:A | nonsynonymous SNV | ELFN1 | p.R704Q | 0.99882 | 0.153 | 4.1 |

| MC_038_3 | Inherited homozygous | chr19:47375602-47375602:G:- | frameshift deletion | DHX34 | p.R734Pfs*38 | 6.5588E−13 | 0.768 | 2.8842 |

| MC_039_3 | X-Linked | chrX:108153670-108153670:G:T | nonsynonymous SNV | ATG4A | p.E323D | 0.98953 | 0.262 | 3.7272 |

| MC_042_3 | X-Linked | chrX:111847345-111847345:G:A | nonsynonymous SNV | TRPC5 | p.S490L | 0.99973 | 0.17 | 4.7221 |

| MC_043_3a | X-Linked | chrX:141907158-141907159:AG:- | frameshift deletion | MAGEC1 | p.Q585Rfs*61 | 0.079896 | 1.913 | −0.2768 |

| MC_045_3 | Compound heterozygous | chr14:31113108-31113108:A:G | nonsynonymous SNV | HECTD1 | p.I2049T | 1 | 0.158 | 9.8105 |

| MC_045_3 | Compound heterozygous | chr14:31121482-31121482:T:A | nonsynonymous SNV | HECTD1 | p.Q1713H | 1 | 0.158 | 9.8105 |

| MC_045_3 | X-Linked | chrX:107597521-107597521:G:A | nonsynonymous SNV | FRMPD3 | p.E581K | 0.00019028 | 0.476 | 4.6328 |

| MC_047_3 | De novo | chr19:12015095-12015095:-:C | frameshift insertion | ZNF433 | p.E591Gfs*3 | 0.012227 | 1.691 | 0.50362 |

| MC_050_3 | Inherited homozygous | chr1:16958675-16958675:G:C | nonsynonymous SNV | CROCC | p.E1319D | 1.2656E−24 | 0.71 | 3.9469 |

| MC_051_4 | De novo | chr4:176150054-176150054:-:TATA | stopgain | WDR17 | p.E687Vfs*2 | 9.6547E−25 | 0.85 | 2.6234 |

| MC_053_3 | Inherited homozygous | chr6:47682450-47682450:C:T | stopgain | ADGRF2 | p.R631X | – | – | – |

| MC_053_3 | Inherited homozygous | chr9:18928536-18928548:GGGCATGTGTAAT:- | frameshift deletion | SAXO1 | p.H245Lfs*58 | – | – | – |

| MC_053_4 | De novo | chr2:241690632-241690632:C:T | stopgain | ING5 | p.R8X | 0.61851 | 0.482 | 3.0217 |

| MC_053_4 | De novo | chr8:113314689-113314689:T:C | nonsynonymous SNV | CSMD3 | p.I95V | 0.057105 | 0.299 | 9.9645 |

| MC_055_3a | De novo | chr19:53353471-53353472:TC:- | stopgain | ZNF845 | p.H933* | 0.00095913 | 1.9 | −0.3907 |

| MC_055_3a | De novo | chr10:26511804-26511804:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | APBB1IP | p.R197W | 0.85443 | 0.371 | 4.0617 |

| MC_055_3a | De novo | chr17:42295746-42295746:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | STAT5A | p.T138I | 0.99994 | 0.202 | 5.6916 |

| MC_055_3a | X-Linked | chrX:102653932-102653932:G:T | stopgain | GPRASP1 | p.E7X | 0.31099 | 0.416 | 4.2 |

| MC_060_3 | X-Linked | chrX:108137147-108137147:A:T | nonsynonymous SNV | ATG4A | p.N98I | 0.98953 | 0.262 | 3.7272 |

| MC_063_4 | X-Linked | chrX:37009816-37009816:C:G | nonsynonymous SNV | FAM47C | p.T469S | – | – | – |

| MC_063_5 | X-Linked | chrX:151671121-151671121:A:C | nonsynonymous SNV | PASD1 | p.E385D | 0.82307 | 0.379 | 3.9976 |

| MC_063_5 | X-Linked | chrX:37009816-37009816:C:G | nonsynonymous SNV | FAM47C | p.T469S | – | – | – |

| MC_066_3 | De novo | chr7:50400256-50400256:T:C | nonsynonymous SNV | IKZF1 | p.S167P | 0.9986 | 0.156 | 4.0515 |

| MC_077_3a | X-Linked | chrX:141896926-141896926:A:G | nonsynonymous SNV | MAGEC3 | p.S92G | 7.6566E−16 | 1.722 | −0.8259 |

| MC_077_3a | X-Linked | chrX:65502089-65502089:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | ZC3H12B | p.S464L | 0.99835 | 0.206 | 4.2592 |

| MC_088_5 | X-Linked | chrX:73563448-73563448:A:G | nonsynonymous SNV | CHIC1 | p.E55G | 0.85254 | 0.476 | 2.3226 |

| MC_099_3a | De novo | chr1:241639950-241639954:CAGGA:- | frameshift deletion | OPN3 | p.S101Pfs*18 | 0.0012801 | 0.894 | 1.8617 |

| MC_100_4a | De novo | chr12:18562854-18562855:AG:- | frameshift deletion | PIK3C2G | p.R1207Sfs*12 | 9.5013E−40 | 1.136 | 0.60465 |

| MC_101_3 | X-Linked | chrX:136349791-136349791:G:T | nonsynonymous SNV | ADGRG4 | p.V2029F | – | – | – |

| MC_106_4 | De novo | chrX:152652679-152652679:A:G | nonsynonymous SNV | GABRQ | p.S433G | 0.0042977 | 0.736 | 2.3834 |

| MC_109_3 | X-Linked | chrX:48058815-48058815:A:G | nonsynonymous SNV | ZNF630 | p.Y543H | 0.000119 | 1.101 | 1.3081 |

| MC_113_3 | Compound heterozygous | chr12:121233045-121233046:CT:- | frameshift deletion | P2RX4 | p.Y339Lfs*7 | 4.9835E−12 | 1.282 | 0.54494 |

| MC_113_3 | Compound heterozygous | chr12:121229057-121229057:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | P2RX4 | p.T254I | 4.9835E−12 | 1.282 | 0.54494 |

| MC_115_4 | X-Linked | chrX:27747991-27747991:A:G | nonsynonymous SNV | DCAF8L2 | p.K366E | 0.81931 | 0.474 | 2.6395 |

| MC_116_4 | De novo | chr3:98133091-98133091:T:C | nonsynonymous SNV | OR5H1 | p.Y132H | 4.6874E−05 | 1.874 | −0.3953 |

| MC_116_4 | De novo | chr12:1646012-1646013:TG:- | frameshift deletion | WNT5B | p.V281Gfs*34 | 0.58535 | 0.494 | 2.9706 |

| MC_117_3 | X-Linked | chrX:151744343-151744343:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | CNGA2 | p.R614C | 0.00098232 | 0.787 | 2.2373 |

| MC_117_3 | X-Linked | chrX:55003032-55003032:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | APEX2 | p.P165S | 0.97302 | 0.268 | 3.0929 |

| MC_117_3 | X-Linked | chrX:143629851-143629851:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | SLITRK4 | p.V420I | 0.79447 | 0.422 | 3.3262 |

| MC_117_4 | X-Linked | chrX:151744343-151744343:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | CNGA2 | p.R614C | 0.00098232 | 0.787 | 2.2373 |

| MC_117_4 | X-Linked | chrX:55003032-55003032:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | APEX2 | p.P165S | 0.97302 | 0.268 | 3.0929 |

| MC_117_4 | X-Linked | chrX:143629851-143629851:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | SLITRK4 | p.V420I | 0.79447 | 0.422 | 3.3262 |

| MC_120_3 | Inherited homozygous | chr13:113084912-113084912:T:G | stopgain | MCF2L | p.Y656X | 2.7178E−07 | 0.504 | 4.8643 |

| MC_124_6 | X-Linked | chrX:152991384-152991385:GT:- | frameshift deletion | PNMA5 | p.T72Cfs*25 | – | – | – |

| MC_125_4 | X-Linked | chrX:37009783-37009783:G:T | nonsynonymous SNV | FAM47C | p.R458L | – | – | – |

| MC_129_5a | De novo | chr5:850480-850480:-:AA | frameshift insertion | ZDHHC11 | p.Q42Sfs*4 | 1.1047E−15 | 1.541 | −0.3378 |

| MC_130_3a | Inherited homozygous | chr11:57380702-57380702:A:- | frameshift deletion | PRG3 | p.C3Afs*28 | 0.00033439 | 1.143 | 1.2307 |

| MC_135_3 | X-Linked | chrX:53084603-53084603:G:A | nonsynonymous SNV | TSPYL2 | p.R289H | 0.87393 | 0.405 | 3.1839 |

| MC_138_3 | X-Linked | chrX:151743323-151743323:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | CNGA2 | p.R274C | 0.00098232 | 0.787 | 2.2373 |

| MC_138_3 | X-Linked | chrX:107602115-107602115:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | FRMPD3 | p.S1392F | 0.00019028 | 0.476 | 4.6328 |

| MC_138_4 | X-Linked | chrX:151743323-151743323:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | CNGA2 | p.R274C | 0.00098232 | 0.787 | 2.2373 |

| MC_138_4 | X-Linked | chrX:107602115-107602115:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | FRMPD3 | p.S1392F | 0.00019028 | 0.476 | 4.6328 |

| MC_144_3a | De novo | chr6:70528348-70528348:G:A | nonsynonymous SNV | FAM135A | p.S995N | 0.99893 | 0.265 | 6.2502 |

| MC_144_3a | Inherited homozygous | chr19:54813219-54813219:-:A | frameshift insertion | KIR2DL4;LOC112268354 | p.M271Nfs*108 | – | – | – |

| MC_146_3 | Inherited homozygous | chr6:78885392-78885393:TG:- | frameshift deletion | IRAK1BP1 | p.V111Dfs*5 | 1.449E−06 | 1.398 | 0.55995 |

| MC_146_3 | X-Linked | chrX:53085669-53085669:A:G | nonsynonymous SNV | TSPYL2 | p.D426G | 0.87393 | 0.405 | 3.1839 |

| MC_146_3 | X-Linked | chrX:53085670-53085670:C:A | nonsynonymous SNV | TSPYL2 | p.D426E | 0.87393 | 0.405 | 3.1839 |

| MC_149_3 | X-Linked | chrX:15479743-15479743:G:A | stopgain | PIR | p.R59X | 5.3402E−10 | 1.799 | −0.6034 |

| MC_149_3 | X-Linked | chrX:3317781-3317781:G:T | nonsynonymous SNV | MXRA5 | p.T1967N | 0.043013 | 0.398 | 5.1219 |

| MC_150_3 | Compound heterozygous | chr12:131915950-131915950:G:A | nonsynonymous SNV | ULK1 | p.A557T | 0.99318 | 0.288 | 5.5149 |

| MC_150_3 | Compound heterozygous | chr12:131917030-131917030:C:A | nonsynonymous SNV | ULK1 | p.T717K | 0.99318 | 0.288 | 5.5149 |

| MC_151_3 | Inherited homozygous | chr7:151195598-151195598:C:- | frameshift deletion | IQCA1L | p.E459Kfs*4 | – | – | – |

| MC_154_3a | De novo | chr12:113105758-113105776:GCCAGACGTAGCGCTTCTT:- | frameshift deletion | RASAL1 | p.K589Sfs*17 | 1.2135E−14 | 0.953 | 1.7907 |

| MC_156_3a | De novo | chr1:52274480-52274480:T:A | nonsynonymous SNV | ZFYVE9 | p.F822Y | 0.90244 | 0.325 | 5.5725 |

| MC_156_3a | Inherited homozygous | chr17:16353365-16353372:GGGGGCCG:- | frameshift deletion | CENPV | p.A22Gfs*20 | 0.33194 | 0.736 | 2.0766 |

| MC_156_3a | X-Linked | chrX:154716292-154716292:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | GAB3 | p.R37H | 0.9536 | 0.341 | 3.5492 |

| MC_158_3a | De novo | chr5:16694505-16694505:T:- | frameshift deletion | MYO10 | p.G1225Afs*22 | 3.1562E−05 | 0.374 | 7.1688 |

| MC_159_3 | Compound heterozygous | chr6:7576422-7576422:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | DSP | p.S920F | 0.99978 | 0.26 | 8.6089 |

| MC_159_3 | Compound heterozygous | chr6:7579763-7579763:G:C | nonsynonymous SNV | DSP | p.E1191D | 0.99978 | 0.26 | 8.6089 |

| MC_159_3 | Compound heterozygous | chr6:7579771-7579771:A:G | nonsynonymous SNV | DSP | p.K1194R | 0.99978 | 0.26 | 8.6089 |

| MC_159_3 | De novo | chr1:20773459-20773459:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | HP1BP3 | p.A130T | 0.98422 | 0.3 | 4.1625 |

| MC_159_3 | Inherited homozygous | chr5:112145946-112145946:A:T | stopgain | EPB41L4A | p.L662X | 3.5133E−21 | 1.015 | 1.4643 |

| MC_159_5 | Inherited homozygous | chr5:112145946-112145946:A:T | stopgain | EPB41L4A | p.L662X | 3.5133E−21 | 1.015 | 1.4643 |

| MC_159_5 | Inherited homozygous | chr14:70167414-70167414:C:A | stopgain | SLC8A3 | p.E337X | 0.00073391 | 0.592 | 3.3014 |

| MC_160_3 | De novo | chr5:144473681-144473681:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | KCTD16 | p.P285L | 0.99329 | 0.2 | 3.5785 |

| MC_160_3 | De novo | chr3:124699950-124699950:A:T | nonsynonymous SNV | KALRN | p.Y940F | 1 | 0.152 | 8.2551 |

| MC_160_3 | Inherited homozygous | chr4:682207-682222:TCCTGCTCCCCCTCGG:- | frameshift deletion | SLC49A3 | p.D354Efs*22 | – | – | – |

| MC_160_3 | De novo | chrX:111776849-111776849:T:A | nonsynonymous SNV | TRPC5 | p.S796C | 0.99973 | 0.17 | 4.7221 |

| MC_161_3a | De novo | chr19:56160179-56160179:T:G | nonsynonymous SNV | ZNF444 | p.F320C | 0.8667 | 0.454 | 2.3789 |

| MC_161_3a | De novo | chr15:88527714-88527714:G:T | nonsynonymous SNV | DET1 | p.L386I | 0.67903 | 0.432 | 3.4607 |

| MC_161_3a | De novo | chr2:158631756-158631756:-:A | frameshift insertion | PKP4 | p.R387Tfs*6 | 5.269E−13 | 0.641 | 3.9671 |

| MC_161_3a | De novo | chr1:226736927-226736927:A:G | nonsynonymous SNV | ITPKB | p.C178R | 0.99994 | 0.148 | 5.0848 |

| MC_161_3a | De novo | chr1:94174411-94174411:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | ARHGAP29 | p.D1018N | 0.99964 | 0.249 | 6.0875 |

| MC_161_3a | De novo | chr1:113973345-113973345:G:C | nonsynonymous SNV | HIPK1 | p.V762L | 1 | 0.121 | 6.4165 |

| MC_161_3a | De novo | chr7:43492124-43492124:G:T | nonsynonymous SNV | HECW1 | p.G1061V | 0.99982 | 0.253 | 7.2151 |

| MC_161_3a | Inherited homozygous | chr7:101557440-101557450:GGGTGGCGCCC:- | frameshift deletion | COL26A1 | p.G413Tfs*38 | 2.9274E−06 | 0.832 | 2.2022 |

| MC_164_3 | Compound heterozygous | chr3:98132875-98132875:T:A | nonsynonymous SNV | OR5H1 | p.Y60N | 4.6874E−05 | 1.874 | −0.3953 |

| MC_164_3 | Compound heterozygous | chr3:98132997-98132997:-:T | frameshift insertion | OR5H1 | p.S103Ffs*19 | 4.6874E−05 | 1.874 | −0.3953 |

| MC_166_3a | De novo | chr1:30738992-30738992:C:G | nonsynonymous SNV | LAPTM5 | p.S153T | 0.90044 | 0.4 | 2.9211 |

| MC_166_3a | De novo | chr3:195381926-195381926:A:C | nonsynonymous SNV | ACAP2 | p.S70A | 0.92325 | 0.324 | 5.4197 |

| MC_166_3a | De novo | chr5:167375332-167375332:G:A | nonsynonymous SNV | TENM2 | p.G121R | 1 | 0.191 | 8.4851 |

| MC_166_3a | De novo | chr3:68739137-68739137:T:A | stopgain | TAFA4 | p.K117X | – | – | – |

| MC_166_3a | Inherited homozygous | chr10:115171344-115171345:TT:- | stoploss | ATRNL1 | p.*468delinsIKSSYEF | 0.99915 | 0.266 | 6.8065 |

| MC_166_3a | X-Linked | chrX:16869523-16869523:G:A | nonsynonymous SNV | RBBP7 | p.P40L | 0.98393 | 0.28 | 3.5915 |

| MC_170_3 | X-Linked | chrX:152651603-152651603:G:T | nonsynonymous SNV | GABRQ | p.A327S | 0.0042977 | 0.736 | 2.3834 |

| MC_172_3a | De novo | chr2:219330807-219330807:G:- | frameshift deletion | RESP18 | p.H101Ifs*25 | 8.716E−10 | 1.747 | −0.4376 |

| MC_172_3a | De novo | chr14:58353693-58353693:A:C | nonsynonymous SNV | ARID4A | p.E564A | 1 | 0.139 | 7.0648 |

| MC_172_3a | Inherited homozygous | chr1:120436639-120436640:AG:- | frameshift deletion | NBPF8 | p.R41Mfs*20 | 1.4181E−07 | 1.967 | −2.0676 |

| MC_173_3 | X-Linked | chrX:118975203-118975207:GGGGG:- | frameshift deletion | LONRF3 | p.G142Rfs*14 | 0.41779 | 0.463 | 3.4438 |

| MC_173_3 | X-Linked | chrX:149594688-149594688:G:A | stopgain | HSFX1;HSFX2 | p.R5X | – | – | – |

| MC_174_3 | X-Linked | chrX:150671531-150671531:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | MTM1 | p.S546F | 0.99961 | 0.176 | 4.6289 |

| MC_175_3a | De novo | chr15:70679628-70679628:T:- | frameshift deletion | UACA | p.R278Gfs*16 | 3.2462E−29 | 0.973 | 1.7364 |

| MC_175_3a | De novo | chr9:128735367-128735367:T:G | nonsynonymous SNV | ZER1 | p.T640P | 0.99992 | 0.178 | 5.2057 |

| MC_175_3a | De novo | chr11:32934995-32934995:C:T | nonsynonymous SNV | QSER1 | p.S1246F | 0.99999 | 0.208 | 6.822 |

| MC_175_3a | De novo | chr10:73792722-73792722:A:G | nonsynonymous SNV | ZSWIM8 | p.D728G | 1 | 0.133 | 7.7289 |

| MC_175_3a | De novo | chr17:44356020-44356020:T:C | nonsynonymous SNV | FAM171A2 | p.Y278C | 0.90848 | 0.381 | 3.309 |

| MC_175_3a | De novo | chr10:100487650-100487650:G:- | frameshift deletion | SEC31B | p.A1169Vfs*19 | 2.5856E−29 | 1.05 | 1.2242 |

All variants are exonic.

LOEUF loss-of-function observed/expected upper bound fraction.

aSamples with a missing parent sample where compound heterozygous variant calling was not possible and de novo, inherited homozygous, and X-linked variant calling relied on one parent only.

Copy number variant analysis

Since CNVs are known to play an important role in ASD26, we analyzed CNVs in the ASD cohort. We called CNVs in individuals with ASD using individuals from the cohort who did not have ASD as controls, utilizing CNVkit27. In total, we identified 539 CNVs across all individuals with ASD, including 276 deletions and 263 duplications (Supplementary Data 9 and 10). The average size of a CNV was 243 kb, and there were 15 CNVs encompassing regions that did not include any genes. Out of the identified CNVs, 34 overlapped with known ASD CNVs as defined by the SFARI Gene database21, including the 3q29, 17p11.2, and 22q13.3 loci. Of the called CNVs, 23 also overlapped with syndromic CNVs from the DECIPHER database28. Some of these syndromes, such as Potocki-Lupski syndrome29 and Smith-Magenis syndrome30, are associated with neurodevelopmental phenotypes. Although our data demonstrate an overlap between CNVs and specific genomic regions, this does not imply that the CNVs are causal. Further investigation is needed to establish the pathogenicity of these variants.

Discussion

We performed WES in a modest familial cohort consisting of 754 individuals from 195 families, with at least one child in each family diagnosed with ASD by a neurologist, child psychiatrist, or psychologist. It is important to note that the source of patient ascertainment can introduce bias; for example, recruitment through clinical centers may be skewed towards cases with comorbid conditions31. Furthermore, the difficulty in diagnosing ASD, particularly in patients with severe intellectual disability32, makes it challenging to determine whether the identified variants are exclusively associated with ASD or if they also contribute to broader neurodevelopmental disorders. The families enrolled in the cohort represented diverse ancestral backgrounds, including African American, Asian, Hispanic, Middle Eastern, Native American, and European. Sequencing a diverse cohort offered a broader genetic landscape, reduced bias, captured population-specific alleles, and provided wider global relevance. While our sample size limited in-depth ancestry-specific analyses5,33, future studies with larger samples can expand on this groundwork.

In total we discovered 38,834 novel private variants in the cohort that have not been previously reported. The lack of large public datasets for most of the ancestries represented in our cohort can affect the incidence of observed variants and could contribute to the number of novel private variants detected. We employed a variant filtration and prioritization pipeline that implements established practices in the field and aligns with other large-scale studies6,7,34, including implementing filtering strategies for all inheritance modes, utilizing deleteriousness prediction algorithms, and incorporating gene constraint scores. Due to the modest size of our cohort, we were unable to leverage more sophisticated methods like the Bayesian analysis framework. Our analysis identified 92 potentially pathogenic coding variants in 73 known neurodevelopmental disease genes. The known genes included ASD genes BCORL1, CDKL5, MECP2, and SETD1B, among other neurodevelopmental disease genes (e.g., ADGRV1, ATP7A, CHD5, and SCN3A). In addition, we compared our findings to data from large-scale cohorts6. Out of the 73 genes, we identified overlap with 11 high-confidence ASD genes identified by Fu et al.6, including ARID1B, ATP1A3, AUTS2, DLG4, DYNC1H1, KMT2C, PLXNA1, SCN1A, SKI, SLC6A1, and SMARCA2, strengthening our results. We also identified 158 potentially pathogenic coding variants in 120 candidate ASD genes (e.g., DLG3, GABRQ, KALRN, and NCOR2). For each of our candidate genes, we analyzed published data from Zhou et al.7 to obtain P values and transmission disequilibrium test (TDT) statistic values representing the contribution of de novo and rare inherited loss-of-function variants to ASD risk, respectively. Although the candidate genes did not reach study-wide significance by de novo variant enrichment (requiring p < 0.001), 4 of them—ATF7IP, ATRNL1, HECTD1, and QSER1—passed the Zhou et al.7 TDT filtering step (TDT statistic ≥ 1, within top 20% LOEUF, and A-risk ≥ 0.4). This is unsurprising, given the familial nature of the cohort in this study and the much larger case-control cohort in Zhou et al.7. In addition, 3 of the identified candidate genes—CENPV, HECTD1, and MAP2—overlapped with high-confidence neurodevelopmental disease genes reported by Fu et al.6.

Tables 2 and 3 summarize the variants we identified in each individual with ASD, specifically in known ASD and neurodevelopmental disease genes, as well as in new candidate genes, respectively. Our analysis revealed distinct sets of genes that merit further investigation. Out of 222 individuals with ASD, we identified at least one potentially pathogenic variant in 112 individuals (~50%), out of which 68 individuals have at least one potentially pathogenic variant in a known neurodevelopmental disease gene (~30%). One of the aims of this study was to aid in identifying causative variants in the probands. The broad phenotypic assessment of the probands limited the granularity of our phenotype-genotype correlations. Furthermore, complete phenotype information was not available for all probands. Nevertheless, our findings are consistent with previous reports on the association between mutations in the identified genes and the observed phenotypes in probands, with commonality in language impairment and developmental delay across variants and probands. For example, proband MC-005-3 presented with ASD, seizures, and learning disabilities, in line with phenotypes of patients with pathogenic CDKL5 mutations35. SETD1B mutations have been associated with intellectual developmental disorder with seizures and language delay (MIM # 611055)36–38. Probands with variants in SETD1B presented with language impairment (MC-146-3, MC-166-3) and seizures (MC-146-3). For proband MC-124-6, our analysis identified a de novo stopgain mutation in CHAMP1. Mutations in this gene are associated with neurodevelopmental phenotypes, including impaired language and speech (MIM # 616327)39, all of which are present in the proband. MC-106-4 and MC-170-3 have variants in GABRQ, associated with essential tremor and ASD40,41. DLG3 mutations were identified in MC-001-3 and MC-001-4, and have been associated with X-linked intellectual disability42,43. Other interesting genes included HECTD1 (MC-045-3) and HECW1 (MC-161-3), which encode proteins predicted to enable ubiquitin ligase activity44. NCOR2 (with a variant daintified in JC-24-3) encodes a nuclear receptor co-repressor 2 that mediates transcriptional silencing of target genes by promoting chromatin condensation, thus preventing access to basal transcription machinery45–47. Sequencing studies in larger cohorts and additional experimental validation will be required to establish causality for the candidate genes that have not been previously linked to ASD.

In conclusion, by sequencing a diverse ASD cohort of individuals from over ten ancestries, this study breaks away from the limitations of single-population analyses and contributes to the ongoing effort of identifying causative genes and variants. While further functional validation is necessary to pinpoint causal variants in probands, these findings provide a valuable roadmap for more targeted future research, which will ultimately deepen our understanding of this spectrum of disorders.

Methods

Subjects and specimens

All human studies were reviewed and approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (UTSW), the research committee at the University of Jordan School of Medicine, the ethics committee of the Jordan University Hospital, and the IRB of the Jordan University of Science and Technology. We have complied with all relevant ethical regulations, including the Declaration of Helsinki. Families were primarily recruited from the Dallas Fort Worth area, with some families recruited from Jordan, and written informed consent was obtained from all study participants. Inclusion criteria included a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) by a neurologist, child psychiatrist, or psychologist. Patients with genetically defined syndromes, specifically Fragile X syndrome, Angelman syndrome, Rett syndrome, or Tuberous sclerosis complex, were excluded from study participation. All patients enrolled in the study received a diagnosis of ASD from their referring clinicians, who performed physical and behavioral assessments and administered the following standard ASD diagnostic measures: (1) Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Second Edition (ADOS-2)—a semi-structured, standardized assessment of communication, social interaction, play, and restricted and repetitive behaviors; (2) The Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R)—this established assessment took ~1.5–3 h to administer, during which an experienced clinical interviewer interviewed a parent or caregiver familiar with the developmental history and current behavior of the individual being evaluated; (3) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V). Since the recruitment sources included multiple sites, there may be instances where not all three tests were performed. This, along with inter-site differences, may present potential sources of variance in our study. Blood samples were collected from all available family members by peripheral venipuncture and genomic DNA was isolated from circulating leukocytes using AutoPure (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Sample preparation and sequencing

All samples were prepared for sequencing using a custom automated sample preparation workflow developed at the Regeneron Genetics Center (RGC). Genomic DNA libraries were created by enzymatically shearing DNA to a mean fragment size of 200 base pairs using reagents from New England Biolabs. A common Y-shaped adapter (IDT) was ligated to all DNA libraries. Unique, asymmetric 10 base pair barcodes were added to the DNA fragments during library amplification with Kapa HiFi to facilitate multiplexed exome capture and sequencing. Equal amounts of sample were pooled prior to overnight exome/genotype capture with the Twist Comprehensive Exome panel, RGC developed Twist Diversity SNP panel, and additional spike-ins to boost coverage at selected CHIP sites and to cover the mitochondrial genome; all samples were captured on the same lot of oligos. The captured DNA was PCR amplified and quantified by qPCR. The multiplexed samples were pooled and then sequenced using 75 base pair paired-end reads with two 10 base pair index reads on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform on S4 flow cells.

Whole exome sequencing and data processing

Sequencing reads from both exome and genotyping assays in FASTQ format were generated from Illumina image data using bcl2fastq program (Illumina). Following the OQFE (original quality functional equivalent) protocol48, sequence reads were mapped to the human reference genome version GRCh38 using BWA MEM49 in an alt-aware manner, read duplicates were marked, and additional per-read tags were added. For exome data, single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and short insertions and deletions (indels) were identified using a Parabricks accelerated version of DeepVariant v0.10 with a custom WES model and reported in per-sample genome variant call format (gVCF) files. These exome gVCFs were aggregated with GLnexus v1.4.3 using the pre-configured DeepVariantWES setting50 into joint-genotyped multi-sample project-level VCF (pVCF), which was converted to bed/bim/fam format using PLINK 1.951. Depth was calculated using mosdepth52 and coverage was assessed using custom scripts. The percent coverage was calculated as the number of base pair positions sequenced to a given depth divided by the total number of bases sequenced.

VCF files for SNVs and indels were annotated with ANNOVAR53 using allele frequencies from the 1000 Genomes project (1000G)12, the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD)16,17, the Greater Middle East Variome project (GME)18, and the Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC)19. The variants were also annotated using the Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Database (dbSNP)54, the database of Human Non-synonymous SNVs and Their Functional Predictions and Annotations (dbNSFP)55, and ClinVar56. Annotated VCF files were uploaded into an SQL database for working storage and analysis. Exome data was stored, and analyses were performed on the Texas Advanced Computing Center (TACC) high-performance computing servers, a resource of the University of Texas (Austin, TX).

Variant filtration

Variants having a read depth of ≥ 10 and a genotype quality (GQ) score of ≥ 30 were retained as quality filtered. Rare variants were defined as those with minor allele frequencies (MAF) < 1% in 1000G12, gnomAD v2.116,17, GME18, and ExAC19. When filtering for rare variants, we used the overall population frequency data from the previously mentioned databases. We further refined the analysis by applying the same cutoffs to each sub-population within the dataset as well. Novel variants were defined as variants that are not found in the four aforementioned public datasets. Private variants were defined as novel variants that occurred only in a single individual in our cohort. De novo variants were defined as heterozygous private variants present in individuals with ASD (absent from the exome of the father, the mother, and the sibling(s) when available). To minimize potential false positive de novo calls, we applied additional filtering steps, requiring that de novo variants have the following criteria: (1) GQ ≥ 99, (2) alternate allele depth (AD-Alt) ≥ 10, (3) reference allele depth (AD-Ref) ≥ 10, (4) 0.3 ≤ AD-Alt/read depth (DP) ≤ 0.7, (5) Allele Quality score ≥ 999, (6) length(Alt) ≤ 50 and length(Ref) ≤ 50. Compound heterozygous variants in offspring were defined as inherited heterozygous variants that occurred within the same gene and that were present in heterozygous form in one parent but not the other. All compound heterozygous variants were filtered for AD-Alt ≥ 10, AD-Ref ≥ 10, and 0.3 ≤ AD-Alt/DP ≤ 0.7. Inherited homozygous variants were required to be present in heterozygous form in both the father and the mother, excluding variants that are homozygous in either one of the parents or siblings with no ASD when available, on the assumption of full penetrance. X-linked variants were X chromosome-specific and were required to be present in a male offspring and heterozygous in the mother.

Variant prioritization

Rare variants that are de novo, compound heterozygous, inherited homozygous, or X-linked, were considered to be possibly damaging if they met the following criteria: (1) splice site variants, (2) exonic variants with a predicted protein effect of frameshift indels, nonframeshift indels, stopgain, stoploss, or unknown effect, (3) exonic nonsynonymous SNVs that were predicted to be damaging by at least 1 of the 2 algorithms used: SIFT57,58 and PolyPhen-2 HumVar59. PolyPhen-2 HumVar was chosen over PolyPhen-2 HumDiv because the former is more appropriate for Mendelian variants with drastic effect as we expect for ASD, while the latter is appropriate for common variants of smaller effect size. Possibly damaging variants were compared to the list of genes implicated in ASD from the Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative (SFARI) Gene 2018 database (using the 2023 Q2 release)21. Variants were also screened for any phenotypic association in the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) database60. Gene constraint was assessed using pLI, LOEUF, and Z scores from gnomAD v2.116,17. To help assess a variant’s potential pathogenicity, the variants were also annotated with ClinVar data and the number of homozygous carriers in gnomAD v4.116,17. To prioritize candidate disease variants (potentially pathogenic variants), we performed the following steps: (1) If the exact same variant was present in more than one unrelated person, it was excluded; (2) Variants within genes that had a SFARI Gene21 score of 1, 2, or S, or were associated with a neurological phenotype as annotated by OMIM were considered as “known” and the rest were considered as “novel”; (3) Within the “known” and “novel” lists, genes having multiple different variants in different people were prioritized; (4) We prioritized loss-of-function (LoF) variants and nonsynonymous SNVs with high probability of deleteriousness based on scores from prediction tools, including SIFT, PolyPhen-2 HumVar, VEST61,62, CADD63, and phyloP64; (5) We prioritized variants within genes with higher pLI (> 0.5) and lower LOEUF (< 0.5) scores. Steps 3-5 were performed sequentially, therefore, a variant was not required to satisfy all subsequent steps if it passed the initial ones; (6) We filtered out variants with ClinVar significance value as benign or likely benign; (7) We filtered out variants having one or more homozygous carriers in gnomAD v4.116,17. The gene TTN is classified as an ASD gene in the SFARI Gene database21 with a score of 2. However, due to the large size of TTN (coding sequence of 108 kb), we calculated the missense mutation rate for TTN in each of the five probands with prioritized TTN variants (JC-21-3, JC-33-3, MC-014-3, MC-053-3, and MC-061-4) to account for its size. This rate was determined by dividing the total number of base pairs carrying missense mutations in TTN in each proband by the total length of the TTN coding region. Subsequently, we compared this ratio for each proband to the TTN missense mutation rate obtained from gnomAD v4.116,17 (1.23 × 10−5). We found that the TTN missense mutation rate in each of the 5 probands (1.57 × 10−4, 2.50 × 10−4, 2.78 × 10−4, 3.33 × 10−4, and 3.70 × 10−4, respectively) exceeded the gnomAD rate. Consequently, we filtered out the TTN variants from the list of prioritized variants in “known” genes, but they are retained in the list of potentially damaging coding variants (Supplementary Data 5).

Since we observed more than one potentially pathogenic variant (in known and/or novel genes) in some probands, we also ranked them according to their likelihood of causing the disease in the proband. We followed the guidelines issued by the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology for the Interpretation of Sequence Variants65. We prioritized variants in known genes over novel genes. Stopgain/stoploss and frameshift variants were ranked over nonsynonymous SNVs, and de novo variants were ranked over other inherited variants. We also annotated the variants with AlphaMissense scores66 and prioritized those with higher scores.

Copy number variant (CNV) analysis

We used CNVkit27 to detect CNVs based on the read depth in ASD samples relative to the average read depth in non-ASD samples in the cohort, using default parameters. Sample MC-064-3 was deemed as an outlier and removed from further analysis for having an unusually high number of CNVs (174 CNVs). The CNV calls segmentation file was filtered to include variants with p < 0.05 and copy number = 0, 1, 3, or 4. Variants were considered deletions if their log2 read depth ratio between the sample and control was ≤ −0.5. Variants were considered duplications if their log2 read depth ratio was ≥ 0.5. If the exact same CNV existed in more than one unrelated proband, it was filtered out. The filtered variants were annotated with known SFARI Gene21 CNVs and DECIPHER28 CNVs. The gnomAD structural variants v4.116,17 frequencies were used to filter out common CNVs with a frequency >1% if the detected CNV completely overlapped with the gnomAD structural variant.

Burden analysis

Nondisrupting variants were defined as exonic synonymous SNVs or exonic nonframeshift indels. The burden of rare LoF and predicted damaging missense variants was analyzed by comparing categories of variants identified in ASD versus non-ASD samples. LoF variants were defined as variants that are exonic or splice site predicted to result in a frameshift indel, a stopgain or stoploss, or splicing error. Missense variants were defined as nonsynonymous exonic or splice site. Missense damaging variants were defined as nonsynonymous SNVs that were predicted to be damaging by at least 1 of the 2 algorithms used: SIFT and PolyPhen-2 HumVar. Comparisons were made between ASD and non-ASD exomes in the above categories for all rare variants.

Principal component analysis

Principal component analysis (PCA) was carried out in PLINK version 1.967 using Phase 3 1000G12 data (populations shown in Supplementary Data 11). PCA input files from our samples were pruned for variants in linkage disequilibrium (LD) with an r2 > 0.2 in a 50 kb window. The LD-pruned dataset was generated using plink –indep-pairwise flag to compute the LD variants. Variants with chromosome mismatches, position mismatches, possible allele flips, and allele mismatches were identified and filtered out. The set of variants that remained was extracted from the 1000 G12 dataset and these were merged with our cohort dataset. PCA was run in PLINK using the –pca flag and the first two principal components were plotted in R. Analysis was performed for the entire cohort, pedigree founders, and probands.

Specific expression analysis

We performed specific expression analysis (SEA) with human transcriptomics data from the BrainSpan collection20 to identify particular human brain regions and/or developmental windows potentially related to ASD pathophysiology along with candidate genes identified in individuals with ASD in this study. For each cell type or brain region, transcripts specifically expressed or enriched were identified at a specificity index (pSI) threshold of pSI < 0.0568. These analyses were performed using the Dougherty lab server (http://genetics.wustl.edu/jdlab/). Lists of candidate genes that overlapped with lists of transcripts enriched in a particular cell type or brain region were finalized using Fisher’s exact test with Benjamini–Hochberg correction. The significance level was set at Q-value < 0.05.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the families for participating in our study and to our clinical colleagues at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and the Children’s Medical Center Dallas and our colleagues in Jordan for referring participants to our study. We thank the Regeneron Genetics Center for sequencing the samples. Additionally, we thank Emma Bergman for her assistance in preparing the Figures. The schematic in Fig. 2 was created with BioRender.com. This work was supported by the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and the Walter and Lillian Cantor Foundation. The funders played no role in the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, or the writing of this manuscript.

Author contributions

M.H.C. conceived the study, acquired funds, and oversaw the project. A.G., K.K., and M.H.C. designed and performed experiments and analyzed data. R.K., M.B., M.A.M., K.G., and P.E. referred subjects and reviewed clinical data. A.G. and M.H.C. wrote the manuscript. All authors participated in reviewing and editing the manuscript.

Data availability