Abstract

Background and aims

Injectable opioid agonist treatment (iOAT) is a valuable, patient-centred, evidence based intervention. However, limited information exists on contextual factors that may support or hinder iOAT implementation and sustainability. This study aims to examine existing research on iOAT using diacetylmorphine and hydromorphone, focusing on identifying the key barriers and facilitators to its successful implementation.

Methods

A systematic search was conducted in the MEDLINE and PsycInfo databases (via Ovid) from inception to February 2024, supplemented by a comprehensive grey literature search. No restrictions were applied regarding publication type, year, or geographic location. Articles were independently screened by two reviewers. Eligible articles described the feasibility, implementation, and/or evaluation of iOAT in one or more countries, presenting perspectives on receiving, administering, or governing iOAT.

Results

Forty-four publications were selected for inclusion. Barriers identified through thematic analysis included public acceptance concerns such as medication diversion, increased crime, and the Honey-Pot effect. Legal and ethical challenges identified involved enacting changes in law to make certain substances available as a medically controlled options for treatment, and addressing patient consent issues. Negative media coverage and public controversies were found to undermine acceptance, and high start-up costs especially for security, facility access, and economic feasibility were seen as additional obstacles. Regulatory barriers and stringent protocols were the most frequently cited limiting factors by patients and providers. Facilitators included the integration of trial prescriptions into comprehensive drug policy strategies and publishing data for evidence-based debates, together with ethics committees ensuring compliance with ethical standards. Developing information strategies and addressing opponents’ claims improved public perception. Cost-effectiveness evidence was found to support long-term implementation, while flexible treatment protocols, inclusive spaces, and affirming therapeutic relationships were seen as important facilitators to enhance patient engagement and treatment effectiveness.

Conclusions

Successful implementation of iOAT requires balancing political and social acceptability with scientific integrity, alongside strategic communication and public outreach. Further research is needed to enhance the transferability of findings across diverse socio-political contexts and address key influencing factors associated with iOAT programs.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12954-024-01102-x.

Keywords: Opioid agonist treatment, Intravenous, Injectable, Feasibility, Harm reduction, Heroin-assisted treatment, Hydromorphone, iOAT

Background

Opioid agonist treatment (OAT) is the most effective and best-established intervention in the treatment of opioid dependence [1], and holds significant importance for public health, providing opioid-dependent individuals access to the healthcare system and serving as a catalyst for improving the health status of this clientele [2]. It helps to stabilize patients socially and is enabling a regulated life with improved social conditions, and reducing infection and other health risks [3, 4].

The selection of the most effective or suitable medication is crucial, as well-tolerated and patient-accepted medications are pivotal factors for retention in treatment [5]. Some individuals are not achieving satisfactory treatment outcomes with an oral route of administration. There are several reasons for this, including side effects, persistent cravings despite optimal dosing, or failure to achieve a therapeutic dose [6–8]. This can lead to the discontinuation of treatment and other negative health and social consequences, including fatal and non-fatal overdoses [2]. While long-acting OAT preparations are considered optimal for providing stable blood levels without sedation or undue side effects and allowing for once-daily dosing, alternative methods—including the administration of original or similar substances via nasal, injectable, or inhalation routes—are crucial for patients who cannot or will not adhere to these regimens. Irregular application, particularly the intravenous use of oral preparations, is associated with increased risks of overdose, infectious complications, and thrombosis, due to inadequate filtration of certain oral excipients such as talc or microcrystalline cellulose [9–14].

Injectable OAT (iOAT), where patients regularly receive injectable diacetylmorphine (iDAM), pharmaceutical pure heroin, free from impurities, constitutes a significant component of the broad therapeutic landscape for individuals with opioid dependence. The treatment is provided in specialized clinics with integrated psychosocial supports and counselling aiming to address their overall health needs with higher levels of retention. This care ensures patient safety (e.g., intervention for on-site respiratory depression), and close contact with healthcare professionals facilitates building relationships with patients [3]. The aim of supervised iOAT is to improve the health of people who inject drugs (PWID) by reducing the risk of overdose and other impending health and social harms associated with continued injecting drug use. Another objective is to engage individuals in addiction treatment who have not benefited from standard OAT settings.

Although effectiveness and safety of this treatment modality is corroborated on several outcomes, it is not regulated and offered in most countries. Supervised iOAT has proven effective in several clinical studies concerning lower mortality than other OAT forms [15], improved health status and quality of life, substantial reduction in the acquisition and use of illegally obtained heroin and other substances [16, 17], reduction in drug-related delinquency, and improvement in social functionality (e.g., stable housing and higher employment rates) [6, 7, 18–20]. Given potential political and societal controversies surrounding supervised iOAT, using a medication already approved for pain treatment like the semi-synthetic opioid hydromorphone, for which initial findings exist, could reduce the barriers for nationwide approval (as required in Germany and Switzerland for DAM). Additionally, it can be assumed that an already approved medications would not attract the same kind of negative publicity as prescribing (pharmaceutical) heroin.

In Austria, the predominant use of slow-release oral morphine (SROM) in OAT highlights a distinctive context compared to other European countries [21]. The non-profit organization Suchthilfe Wien, located in Vienna, Austria, is currently undertaking a feasibility study regarding the implementation and safety of iOAT utilizing injectable hydromorphone (iHDM). Within this pilot study, the study team aims to investigate the feasibility of a patient-centred approach, tailored specifically to the needs of PWID in Vienna, and assess its potential to enhance engagement with healthcare services, support reintegration, and contribute to health stabilization. Additionally, it seeks to address the issue of unintended administration routes of oral OAT medications. This review was initiated to examine the international research landscape concerning iOAT with HDM or other opioids to inform the pilot study in Vienna. While alternative methods, such as nasal administration of original or similar substances, are employed in countries like Switzerland [22, 23], this review’s research questions are centred on the unique circumstances in Austria and the specific challenges addressed by iOAT:

Which studies have explored the feasibility and/or implementation of iOAT in individuals with long-term severe opioid dependence, and how are these aspects conceptualized?

Which perspectives related to receiving, administering, or regulating iOAT have been described, including public acceptance, costs, and public health outcomes?

Which barriers and facilitators have been identified in implementing iOAT, and what factors contribute to ongoing political resistance despite its proven benefits?

Methods

Search strategy

We conducted this scoping review using the Arksey and O’Malley [24] methodological approach as a framework. This is a five-stage framework that includes identifying the research question, identifying relevant studies, study selection, charting the data, and collating, summarizing, and reporting of results. We searched MEDLINE and APA PsycINFO (via Ovid) from inception to February 2024 to identify relevant studies. The central concepts incorporated into the search strategy were hydromorphone, diacetylmorphine, opioid use, and feasibility (see Table 1). The definition of feasibility studies by Bowen et al. [25] guided the selection of keywords, covering elements such as acceptability, service use, demand, implementation, practicality, adaptation, integration, expansion, and limited efficacy testing. Keywords and synonyms relevant to these two concepts were searched as both text words (title/abstract) and subject headings (e.g., MeSH), as appropriate. References of included articles and identified reviews were hand-searched for potentially relevant articles. To identify additional information sources and grey literature, we sought reports, working papers, government documents, white papers, and evaluations from cities, academia and health organizations. These were identified using citation searches (forward and backward) and keyword searches (e.g., “injectable/intravenous OAT,” “heroin-assisted treatment”) across platforms such as Google, Google Scholar, PubMed, ResearchGate, and relevant governmental and organizational websites (e.g., European Union Drugs Agency, Harm Reduction International, Pompidou Group, International Network of People Who Use Drugs) within the period of 15–21 March 2024. The PRIMSA-ScR reporting guidelines developed by Tricco et al. [26] were followed. The search strategy for each database is provided in the supplementary material.

Table 1.

Keywords for search strategy

| Search block | Example keywords (1) |

|---|---|

| 1: Opiods | opioid, opiate, heroin, diacetylmorphine, diamorphine, hydromorphone |

| 2: Addiction | addiction, dependence, disorder, use, misuse, abuse, OUD |

| 3: Intravenous use | inject, injecting, injectable, intravenous, parenteral |

| 4: Treatment | substitution, maintenance, agonist, heroin-assisted, OAT, OST, OMT, program |

| 5: Feasibility aspects | feasibility, acceptability, demand, implementation, practicality, barriers, facilitators |

| 6 | 1 AND 2 AND 3 AND 4 AND 5 |

(1) For detailed search strategies including all keywords and controlled vocabulary, see supplementary material

Study selection

Primary and secondary studies were included if they met all the following inclusion criteria: (1) described the feasibility, implementation, and/or evaluation of iHDM or iDAM for OAT in individuals with long-term severe opioid dependence, and intravenous opioid use, (2) presented perspectives that directly related to experience receiving (patients), administering (healthcare providers), or governing (policymakers and other stakeholder) iOAT. Case reports or series on specific subgroups, e.g., pregnant or breastfeeding women, or hospitalised individuals or studies that reported results on individuals with a severe substance dependence of substances other than opioids and/or without intravenous opioid use were excluded. All abstracts were reviewed in duplicate. Any study included by either reviewer proceeded to full text review. Full-text review was conducted in duplicate by two reviewers, with disagreements resolved through consensus.

Data extraction and synthesis

The aim of the data extraction was to collect and analyze information from included studies required to identify relevant themes and subthemes. We developed a data extraction form that allowed us to evaluate each article and to identify any relevant information. The following data from each eligible article was summarized and extracted: author(s); year of publication; publication type; country/countries discussed; the objective of the study; types of evidence from which the barriers/facilitators were derived; summary of methods; facilitators to the implementation of iOAT; and barriers to the implementation of iOAT. Extraction of descriptive data was completed by one reviewer and verified by a second reviewer, with discrepancies resolved though consensus. We applied thematic analysis using the Framework Analysis Approach by Ritchie et al. (2014) [27] to systematically organize the data. A thematic framework was developed based on recurring issues related to barriers and facilitators of iOAT implementation. The extracted data were indexed and charted into a matrix, enabling detailed comparison across studies and contexts. This approach allowed for the clear structuring of themes and subthemes, facilitating comprehensive cross-study comparisons within the review.

Results

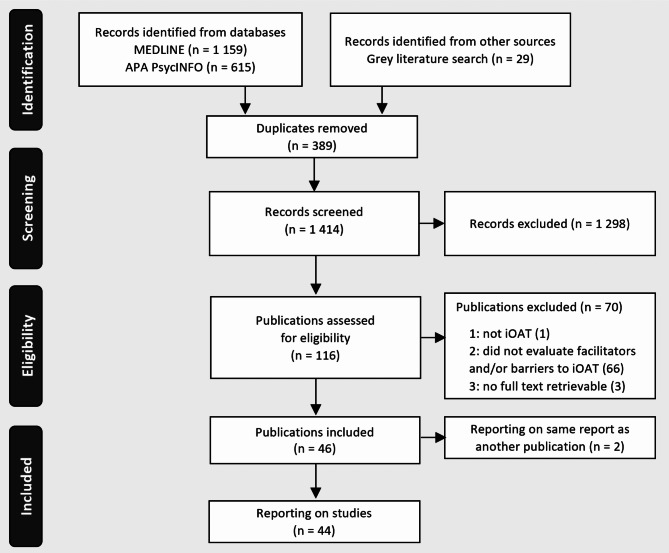

A total of 1 803 records were identified by database search, and additional grey literature searches and imported for screening. There were 389 duplicate records removed, resulting in 1 414 unique records. After title and abstract screening, the remaining 116 full texts were evaluated based on inclusion and exclusion criteria, resulting in the exclusion of 70 studies. Consequently, 46 publications reporting on 44 studies were included in the review (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for selection of studies. iOAT = injectable opioid agonist treatment. Source: Tricco et al. [26]

Study characteristics

The characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 2. Included publications were published between 1992 and 2024 in English and German, primarily originating from English-speaking countries (30 out of 44). Feasibility aspects of iOAT programs were predominantly explored within Canada (17 studies), followed by the UK (6 studies), and Australia (5 studies). Additionally, there were five studies from Germany; two each from the USA, the Netherlands, and Spain; and one each from Austria, France, and Switzerland. Furthermore, two studies with a broader international context were identified. Feasibility and implementation aspects were predominantly examined in relation to iDAM, which was the focus of 22 out of the 44 studies. Five studies specifically investigated iHDM, while 17 studies explored both substances. The included publications encompassed a diverse range of formats: 23 were research articles, nine were commentaries, and three each were methodology articles and policy case studies. Additionally, this review included a monograph, an editorial, a review, seminar proceedings, a study report, and one systematic review.

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies

| First author(s), publication year | Countries discussed | Substance discussed | Publication type | Study aim | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allen et al. (2023) [28] | Interest in treatment with injectable diacetylmorphine among people who use opioids in Baltimore City, Maryland (USA) | USA | iDAM | Research article | To examine factors associated with interest in treatment with iOAT with DAM among a sample of people who use opioids in the US. |

| Archambault et al. (2023) [29] | Implementing injectable opioid agonist treatment: a survey of professionals in the field of opioid use disorders | Canada | iDAM/iHDM | Research article | To describe the perspective of professionals in the field of OUD regarding appropriateness of iOAT for their patients, and the obstacles to its implementation. |

| Bammer et al. (1999) [30] | The Heroin Prescribing Debate: Integrating Science and Politics | Australia, UK, Switzerland | iDAM | Commentary | To evaluate the use of heroin prescription for treating OUD, highlighting the need for more research trials to inform clinical and policy decisions. |

| Bammer (1993) [31] | Should the controlled provision of heroin be a treatment option? Australian feasibility considerations | Australia | iDAM | Commentary | To explore the feasibility and implications of a proposed trial for controlled heroin provision, with relevance to drug policy debates and treatment services. |

| BammerMcDonald (1992) [32], Bammer & McDonald (1994) [33], Bammer & Gerrard (1992) [34] | Feasibility Research into the Controlled Availability of Opioids Stage 2; Heroin Treatment – New Alternatives, Proceedings of a one–day seminar | Australia | iDAM | Seminar proceedings | To propose and justify the initiation of two pilot studies in Canberra to evaluate the feasibility and potential benefits of including DAM in maintenance treatment for people who use opioids. |

| Beaumont et al. (2024) [35] | Shared decision-making and client-reported dose satisfaction in a longitudinal cohort receiving injectable opioid agonist treatment (iOAT) | Canada | iDAM/iHDM | Research article | To explore the differences between iOAT clients reporting dose satisfaction versus dissatisfaction and their perceptions of involvement in treatment decision-making. |

| Belackova et al. (2019) [36] | Learning from the past, looking to the future – Is there a place for injectable opioid treatment among Australia’s responses to opioid misuse? | Australia | iDAM | Research article | To explore the feasibility and implementation options for supervised iOAT in Australia, considering the current need for alternative treatments for OUD and addressing concerns related to delivery and sustainability. |

| Bertin et al. (2023) [12] | People who inject oral morphine favour experimentation with injectable opioid substitution | France | iDAM/iHDM | Research article | To collect data on field practices from PWID regarding the medications used, procurement, dissolution, and filtration techniques, injection equipment, and their expectations regarding a possible iOAT in France. |

| Blanken et al. (2010) [37] | Heroin-assisted treatment in the Netherlands: History, findings, and international context | The Netherlands | iDAM | Monograph | To summarize the history, findings, and international context of iOAT in the Netherlands, highlighting its safety and effectiveness. |

| Bowles et al. (2024) [38] | A qualitative assessment of tablet injectable opioid agonist therapy (TiOAT) in rural and smaller urban British Columbia, Canada: Motivations and initial impacts | Canada | iDAM/iHDM | Research article | To explore if tablet iOAT has reduced negative health outcomes (incl. overdose risk) among recipients and to explore recipient’s enrolment motivators, goals, and challenges in achieving them. |

| Carnwath (2005) [39] | Heroin prescription: a limited but valuable role | UK | iDAM | Commentary | To counter criticism of the new guidelines on iDAM by providing evidence-based arguments in support of these guidelines, addressing concerns about treatment efficacy, dosage levels, historical context, and practical considerations. |

| Dobischok et al. (2023) [40] | “It feels like I’m coming to a friend’s house”: an interpretive descriptive study of an integrated care site offering iOAT (Dr. Peter Centre) | Canada | iDAM/iHDM | Research article | To capture what it means for service users and service providers to incorporate iOAT in an integrated care site and describe the processes that facilitate engagement. |

| Dobischok et al. (2023) [41] | Measuring the preferences of injectable opioid agonist treatment (iOAT) clients: Development of a person-centered scale (best-worst scaling) | Canada | iDAM/iHDM | Research article | To develop a person-centred scale that assesses current and former iOAT clients’ most and least wanted aspects of iOAT. |

| Eydt et al. (2021) [42] | Service delivery models for injectable opioid agonist treatment in Canada: 2 sequential environmental scans | Canada | iDAM/iHDM | Research article | To identify the number and location of iOAT programs, describe their service delivery models, characterize clinical and operational features of the programs, and document service delivery barriers and facilitators. |

| Fox et al. (2023) [43] | High Interest in Injectable Opioid Agonist Treatment With Hydromorphone Among Urban Syringe Service Program Participants | USA | iHDM | Research article | To determine whether PWID with severe OUD engaging in syringe services programs would be interested in iOAT with HDM. |

| Friedmann et al. (2023) [44] | Exploring Patients’ Perceptions on Injectable Opioid Agonist Treatment: Influences on Treatment Initiation and Implications for Practice | Germany | iDAM/iHDM | Research article | To explore patients’ perceptions on iOAT and how these influence therapy initiation in practice. |

| Friedmann et al. (2023) [45] | Supervised on-site dosing in injectable opioid agonist treatment-considering the patient perspective. Findings from a cross-sectional interview study in two German cities | Germany | iHDM/ iDAM | Research article | To investigate how patients experience on‑site application and derive strategies to enhance the acceptability and effectiveness of iOAT‑delivery. |

| Gartry et al. (2009) [46] | NAOMI: The trials and tribulations of implementing a heroin assisted treatment study in North America | Canada | iDAM | Policy case study | To determine whether the closely supervised provision of iOAT is more effective than methadone alone in recruiting, retaining, and benefiting PWID with OUD who are resistant to current standard treatment options. |

| Gilvarry (2005) [47] | Commentary on: New guidelines for prescribing injectable heroin in opiate addiction | UK | iDAM | Commentary | To address the controversy surrounding the prescription of iDAM, covering regulations, UK guidelines, government recommendations, and concerns regarding efficacy, cost, opposition, resistance, and ethics associated with this treatment. |

| Jackson et al. (2023) [48] | “They Talk to Me Like a Person” Experiences of People in an Injectable Opioid Agonist Treatment Program | Canada | iDAM/iHDM | Research article | To explore client experiences in a community-based iOAT program. |

| Krausz (2007) [49] | Heroingestützte Behandlung – Basisversorgung oder Ultima ratio im internationalen Vergleich | Germany | iDAM | Commentary | To support iDAM as an effective approach for individuals not reached by existing OAT programs, and to explore factors hindering its clinical implementation and potential future developments in OAT. |

| Lawrence et al. (2000) [50] | ‘Sending the wrong signal’: Analysis of print media reportage of the ACT heroin prescription trial proposal, August 1997 | Australia | iDAM | Research article | To analyze and compare newspaper coverage about heroin during a period spanning two government policy decisions to approve, and then prevent a trial of iDAM prescription to people with OUD. |

| Lintzeris (2009) [51] | Prescription of heroin for the management of heroin dependence: current status | UK | iDAM | Review | To review the prescription of iDAM for OUD, covering its pharmacology, program delivery, and evidence from trials. |

| Lintzeris et al. (2006) [52] | Methodology for the Randomised Injecting Opioid Treatment Trial (RIOTT): evaluating injectable methadone and injectable heroin treatment versus optimised oral methadone treatment in the UK | UK | iDAM | Methodology article | To outline the methodology of RIOTT, a prospective open-label RCT examining the effectiveness of supervised iOAT compared to optimized oral methadone treatment for managing OUD in patients not responding to conventional OAT. |

| Magel et al. (2024) [53] | How injectable opioid agonist treatment (iOAT) care could be improved? service providers and stakeholders’ perspectives | Canada | iDAM/iHDM | Research article | To explore stakeholder and expert perspectives on the delivery of iOAT care and how it can be improved to better meet service users’ needs. |

| Maghsoudi et al. (2020) [54] | Expanding access to diacetylmorphine and hydromorphone for people who use opioids in Canada | Canada | iHDM | Commentary | To explore the current state of policy and practice for DAM and HDM as OAT options in Canada, outlining the rationale for rapid expansion of access, and highlighting necessary clinical and policy changes. |

| March et al. (2006) [55] | Controlled trial of prescribed heroin in the treatment of opioid addiction | Spain | iDAM | Research article | To assess the efficacy of the prescription of iDAM versus oral methadone with medical and psychosocial support among socially excluded individuals with OUD for whom standard treatments have failed. |

| March et al. (2004) [56] | [The experimental drug prescription program in Andalusia (March et al.): procedure for recruiting participants] | Spain | iDAM | Methodology article | To describe the recruitment process for participants in the experimental iOAT program in Andalusia (PEPSA), focusing on reaching socially excluded individuals with OUD who have not benefited from other treatments. |

| Marchand et al. (2020) [57] | Building healthcare provider relationships for patient-centred care: A qualitative study of the experiences of people receiving injectable opioid agonist treatment | Canada | iDAM/iHDM | Research article | To explore participants’ experiences in iOAT and how these experiences affected participants’ self-reported treatment outcomes. |

| Mayer et al. (2020) [58] | Motivations to initiate injectable hydromorphone and diacetylmorphine treatment: A qualitative study of patient experiences in Vancouver, Canada | Canada | iDAM/iHDM | Research article | To examine peoples’ motivations for accessing iOAT and situating these within the social and structural context that shapes treatment delivery. |

| Mayer et al. (2023) [59] | Women’s experiences in injectable opioid agonist treatment programs in Vancouver, Canada | Canada | iDAM/iHDM | Research article | To examine how social context (e.g., gendered norms, income, housing) and structural aspects of program delivery (e.g., operations, rules, policies) impact women’s iOAT engagement. |

| McNair et al. (2023) [60] | Heroin assisted treatment for key health outcomes in people with chronic heroin addictions: A context-focused systematic review | International | iDAM/iHDM | Systematic Review | To evaluate the effectiveness of supervised iDAM and analyse the significance of context and implementation in the design of successful programmes. |

| Meyer et al. (2023) [61] | Intravenöse Opioid-Agonistentherapie (OAT) in Österreich? - Intravenous opioid agonist therapy (OAT) in Austria? | Austria | iHDM | Editorial | To advocate for a diversified approach to OAT in Austria and discuss the rationale for the current pilot study on iOAT with HDM in Vienna. |

| Oviedo-Joekes et al. (2010) [62] | Double-blind injectable hydromorphone versus diacetylmorphine for the treatment of opioid dependence: a pilot study | Canada | iHDM | Research article | To test if iHDM and iDAM differ in their safety and effectiveness for the treatment of opioid dependence. |

| Oviedo-Joekes et al. (2015) [63] | The SALOME study: recruitment experiences in a clinical trial offering injectable diacetylmorphine and hydromorphone for opioid dependency | Canada | iHDM | Methodology article | To describe the recruitment strategies in SALOME, which offered appealing treatments but had limited clinic capacity and no guaranteed post-trial continuation of the treatments. |

| Oviedo-Joekes et al. (2023) [64] | Clients’ experiences on North America’s first take‑home injectable opioid agonist treatment (iOAT) program: a qualitative study | Canada | iDAM/iHDM | Research article | To explore the processes through which take‑home iOAT doses impacted clients’ quality of life and continuity of care in real‑life settings. |

| Poulter et al. (2024) [65] | Diamorphine assisted treatment in Middlesbrough: a UK drug treatment case study | UK | iDAM | Policy case study | To evidence outcomes from the first operational iOAT service in England outside of a research trial. |

| Riley et al. (2023) [66] | ‘This is hardcore’: a qualitative study exploring service users’ experiences of Heroin-Assisted Treatment (HAT) in Middlesbrough, England | UK | iDAM | Research article | To explore Middlesbrough iDAM service users’ experiences of treatment, with particular focus on tensions experienced around treatment initiation and ongoing treatment adherence. |

| Springer (2007) [67] | Heroingestützte Behandlung: drogenpolitische Aspekte | Germany/Austria | iDAM | Commentary | To provide an overview and analysis of the development, implementation, and implications of iDAM programs for OUD, with a focus on their effectiveness, ethical considerations, and prospects, based on international experiences and research findings. |

| Steel et al. (2017) [68] | Our Life Depends on This Drug: Competence, Inequity, and Voluntary Consent in Clinical Trials on Supervised Injectable Opioid Assisted Treatment | Canada | iDAM/iHDM | Commentary | To explore the ethical considerations surrounding voluntary consent in supervised iOAT research. |

| Uchtenhagen (2010) [69] | Heroin-assisted treatment in Switzerland: a case study in policy change | Switzerland | iDAM | Policy case study | To describe the intentions, the process, and the results of setting up the new treatment approach of prescribing iDAM to treatment resistant individuals with OUD, as an example of drug policy change. |

| van den Brink et al. (1999) [70] | Medical co-prescription of heroin to chronic, treatment‐resistant methadone patients in the Netherlands | The Netherlands | iDAM | Research article | To provide a detailed description of a RCT investigating the effectiveness of co-prescribed iDAM as a treatment option for OUD in the Netherlands, along with discussing its potential implications for future treatment approaches. |

| Wodak (1997) [71] | Public health and politics: the demise of the ACT heroin trial | Australia | iDAM | Commentary | To argue for the implementation of a iDAM trial in Australia based on evidence-based policy and practice, highlighting the benefits observed in similar trials abroad and critiquing the political interference and ideological basis of current drug policy decisions. |

| ZIS (2006) [72] | Das bundesdeutsche Modellprojekt zur heroingestützten Behandlung Opiatabhängiger – eine multizentrische, randomisierte, kontrollierte Therapiestudie. Abschlussbericht der klinischen Vergleichsstudie zur Heroin- und Methadonbehandlung | Germany | iDAM | Study report | To examine whether the medical prescription of iDAM in a structured and controlled treatment setting achieves outcomes comparable to standard addiction therapies for OUD. |

iDAM injectable diacetylmorphine, iHDM injectable hydromorphone, OAT opioid agonist treatment, iOAT injectable opioid agonist treatment, OUD opioid use disorder, PWID people who inject drugs, RCT randomized controlled trial

Findings from thematic analysis

Our synthesis identified several barriers and facilitators of iOAT piloting and (long-term) implementation, encompassing diverse stakeholders, including society at large, the scientific community, politics and policymakers, the media, cities/states, healthcare providers, and patients, community members, and peers. The findings extracted from this search were organized into the following themes: (1) Public acceptance, (2) Legal and ethical considerations, (3) Coverage in the media and interest groups, (4) (Long-term) implementation costs and benefits, and (5) Patients’ and providers’ perspectives, see Tables 3 and 4.

Table 3.

Summary of methods, types of evidence, barriers, and facilitators

| First author(s), publication year | Summary of methods and types of evidence | Barriers | Facilitators |

|---|---|---|---|

| Allen et al. (2023) [28] | The authors used data from the PROMOTE study, a cross-sectional study of people who used non-prescription opioids in Baltimore City (US), who were given a brief description of treatment with iDAM and then asked to rate their level of interest. | None discussed. | High level of interest among people who used non-prescription opioids; Past utilization of medications for OUD was also linked to increased interest in iOAT with DAM. |

| Archambault et al. (2023) [29] | The authors conducted a web-based convenience sample survey to describe the perspective of OUD professionals on iOAT implementation in Canada. | Difficulty to access appropriate facilities and equipment with enough space to provide an injection room and a post-injection room; Funding issues; Security in the workplace; Service organisation for iOAT in terms of referrals, admission criteria or schedules; Lack of available or qualified staff (‘complex expertise’); Low acceptability of iOAT implementation by professionals referring to ongoing prejudice and stigma against patients, the substance, and the route of administration; Large territories and lack of transportation in non-urban areas; Social barriers/acceptability; Managing disappointment for non-eligible patients. | Knowledge transfer regarding iOAT effectiveness and clinical implications in fostering engagement among healthcare professionals; Consideration of regional differences and local needs when implementing iOAT programs. |

| Bammer et al. (1999) [30] | The authors assess the effectiveness of iDAM prescription for OUD treatment by analyzing existing programs in the UK and Switzerland, discussing the need for new clinical trials, and addressing potential risks associated with iDAM prescription. | Concerns about promoting a more permissive attitude toward illegal drug use in young people; Influx of PWUD into the study city (Honey-Pot effect); Concerns about undermining the attractiveness and effectiveness of other/conventional treatments; High costs for the healthcare system. | Minimization of the Honey-Pot effect through strict residence criteria; Limiting the number of participants; Close collaboration with local police. |

| Bammer (1993) [31] | The author proposes a trial for providing iDAM to people with OUD in the Australian Capital Territory, based on feasibility investigations and discussions on therapeutic relationship and social control, with broader implications for treatment services and drug policy debates. | Concerns about promoting a more permissive attitude toward illegal drug use in young people; Influx of PWUD into the study city (Honey-Pot effect). | Information strategy: Study reports, publications in scientific journals, conference contributions, articles in community newsletters, and press releases; Engagement with main interest group and finding consensus to consider their concerns; Newsletters with current information related to the study and political events; Open and public research; Economic evaluation of the study. |

| BammerMcDonald (1992) [32], Bammer & McDonald (1994) [33], Bammer & Gerrard (1992) [34] | The report recommends conducting pilot studies in Canberra to evaluate adding iDAM to maintenance treatment for people with OUD. It addresses concerns about international treaties, changes in laws, community support, potential risks, and estimated costs and benefits, highlighting the significance of the proposed trials in strengthening treatment options for OUD. | More permissive attitude toward illegal drug use; Honey-Pot effect, coupled with increased visibility of the “scene;” Increased crime; Difficult law enforcement; Increased demand for drug-related and other health and social services; Possible pregnancies in study participants; Long-term costs of prescribing iDAM; Opportunity costs. | More staff due to iDAM distribution may lead to more use for counselling and social support than conventional treatments; Communication with the media should reinforce the decoupling between iDAM prescription and illegal drugs; Oversight by an independent committee. |

| Beaumont et al. (2024) [35] | The authors present a secondary retrospective analysis which examined iOAT clients’ self-reported dose-satisfaction while also examining other factors associated with participants’ dose-satisfaction status. | Restrictions on available medications impact treatment attractiveness and engagement; Inflexible restrictions on dose adjustments. | Involvement of clients in treatment decisions; Accommodating varying tolerance levels and responses; Balancing safety considerations with patient autonomy and treatment effectiveness. |

| Belackova et al. (2019) [36] | The commentary discusses the potential implementation of supervised iOAT in Australia, citing support from State Health Ministers in the 1990s and recent evidence from RCTs, proposing a medium-duration treatment approach integrated into existing public OAT clinics. | Lack of a strategy for the termination of the pilot study (treatment completion/termination, options for further treatment); High costs for the health sector due to the indefinite adoption of iOAT, extended working hours of nursing staff, and investments in facilities. | Implementation of iOAT in existing facilities instead of establishing separate clinics; Patient-centred care, efficient transition of oral OAT patients to iOAT program due to shared accommodation/facility; Implementation of iOAT with an approved medication (HDM) to reshape this treatment modality and mitigate controversy over DAM prescription; Broad involvement of stakeholders in further discussions on the acceptance and feasibility of this treatment. |

| Bertin et al. (2023) [12] | The study present results of an anonymous online survey including all voluntary respondents residing in France and using oral morphine intravenously, conducted in partnership with the Psychoactif harm reduction organization. | Reluctance towards iOAT due to concerns about breaking glass vials, persistent infectious risks associated with injection, and attachment to the ritual of oral morphine administration. | Positive expectations such as safer injection practices, reduced risks associated with excipients, simplified handling due to an adapted formulation; Alternative treatment options may encourage transition away from illegal markets and engage in formalized treatment; Recognizing co-prescription of two opioids for OAT purposes, but with different routes of administration, as a valid form of care. |

| Blanken et al. (2010) [37] | The monograph describes the history, findings, and international context of iDAM in the Netherlands, covering aspects such as history, efficacy, safety, patient perspective, pharmacological basis, registration process, and international context of this treatment modality. | None discussed. | Recommendation of study implementation by the National Health Council, leading the government to prepare and conduct the proposed study in consultation with the parliament; Conducting naturalistic studies to examine whether the results of RCTs can be replicated in clinical routine practice. |

| Bowles et al. (2024) [38] | The study conducted semi-structured interviews among recipients of a tablet iOAT program in two sites in British Columbia, Canada to assess impact on health and wellbeing, including overdose risk. | Limited medication options; Adjusting doses necessary; Daily pick up of tablet iOAT medications; Daily social interactions with staff required and perceived burdensome. | Facilitated uptake of table iOAT by recommendations from peers or trusted medical professionals; Complementary treatment with first-line oral OAT medication. |

| Carnwath (2005) [39] | The author discusses the debate over iDAM guidelines, presenting arguments for and against their implementation based on evidence from studies in the Netherlands, Switzerland, and the UK, highlighting the effectiveness of iDAM in treatment-resistant individuals and the historical context of DAM prescribing practices. | None discussed. | Comprehensive supervision initially required to prevent diversion/problematic use, promote safe injection, facilitate the use of higher doses, and include patients with chaotic lifestyles. |

| Dobischok et al. (2023) [40] | The authors conducted semi-structured interviews with service users and service providers to investigate the addition of iOAT at an integrated care in Vancouver, British Columbia. | Regulatory barriers: restrictions on accessing medications and daily supervised doses; Requirement for daily supervised doses as a barrier to iOAT engagement; Need for additional healthcare services, including different iOAT medications and in-house GPs; Geographic accessibility for remote communities; iOAT strictly seen as a specialized treatment instead of part of the general continuum of care. | Incorporation of iOAT within an integrated care site, allowing for individualized treatment approaches; ‘De-medicalization’ of iOAT allows service users to experience the integrated care site as a “home or community;” Positive, non-judgmental, and trusting relationships between service users and providers; Food program as a pathway to service engagement; Location of integrated care site outside from triggering environments and street-entrenched substance use. |

| Dobischok et al. (2023) [41] | The authors developed a person-centered best-worst scale (BWS), a preference elicitation method from health economics, to assess iOAT clients’ treatment delivery preferences by conducting semi-structured individual interviews and semi-structured focus groups. | Resistance to integrate person-centered care into policy and practice despite general acceptance in the medical field. | Best-Worst Scaling to assess current and former iOAT clients’ treatment delivery preferences, providing data for decision-makers to expand iOAT programs effectively and cost-efficiently; Maximizing client autonomy; Facilitating adaptation of iOAT programs to engage unmet needs and improve continuation of care for current clients. |

| Eydt et al. (2021) [42] | The study conducted two environmental scans to identify and describe iOAT programs in Canada, finding 14 unique programs operating across urban centres with varied service delivery models and barriers and facilitators to implementation reported. | Lack of capacity; Operation of or collaborations with pharmacies; Lack of access to DAM. | Patient-centred care; Access to other health and social services; Employment of peers; Ease access to iOAT medications by producing DAM locally; Improving supply chains to reduce costs, reimburse HDM. |

| Fox et al. (2023) [43] | The authors conducted a cross-sectional survey recruiting PWID from syringe services programs in New York City to explore acceptability of iOAT with HDM by inquiring about participants’ preferences for treatment and perceptions of potential benefits that could result from iOAT with HDM. Moreover, they discuss potential benefits and downsides of introducing iOAT with HDM in the US context specifically. | Significant ideological resistance to adopting iOAT in the US (similar to methadone treatment); Resource-intensive and more expensive treatment form (concerns about its implementation in resource-limited settings and leading to it being chosen over less expensive, more established treatments). | Interest in iOAT with HDM, especially among PWID at high risk for overdose (severe OUD, frequently inject in public places); Incorporating iOAT into the broader response to the US overdose crisis to address gaps in the current treatment system. |

| Friedmann et al. (2023) [44] | The authors conducted semi-structured interviews with individuals currently in or eligible for iOAT in two German outpatient iOAT clinics. | Requirement for daily visits to the clinic; Conflicting perceptions of iOAT’s benefits and detriments; Stigma surrounding iOAT and the individuals receiving it. | Autonomy in healthcare decisions and individualized treatment approaches; Acknowledging patients’ diverse interpretations of recovery; Informed decision-making to differentiate between perceptions backed by evidence and those based on misconceptions or stigma. |

| Friedmann et al. (2023) [45] | The authors conducted semi-structured interviews and an inductive qualitative content analysis to investigate how patients experience on-site application of iOAT and to derive strategies to enhance the acceptability and effectiveness of iOAT delivery within and beyond Germany. | Daily visits for iOAT, impeding self-determination and quality of life; Stigma surrounding iOAT and intersecting stigmas related to employment. | Daily visits provide structure and stability and allow access to social support and long-term care; Collaboration with healthcare staff to customize medication (combining iOAT with oral OAT); Provision of multidimensional care in one place to reduce commuting time and address mental, physical, legal, and social aspects of health. |

| Gartry et al. (2009) [46] | The authors conducted a case study chronicling the challenges of initiating an iDAM trial in Canada, outlining the background, objectives, and logistics involved in setting up the NAOMI study, focusing on recruitment, media engagement, and the study’s status. | Risk of disrupting the balance between scientific integrity and public education; Concerns from residents due to a honey-pot effect; Extensive requirements for facility infrastructure and security measures. | None discussed. |

| Gilvarry (2005) [47] | The study explored the history and implementation of DAM prescription for OUD in the UK, highlighting inconsistencies and doctors’ reluctance, while discussing challenges and principles surrounding iOAT programs based on previous research and guidelines. | Prescription of iDAM as an exceptional treatment within a comprehensive care program, suitable only for a minority. | Consideration of iOAT as a special treatment modality requiring the development of new integrated treatment pathways. |

| Jackson et al. (2023) [48] | The authors conducted secondary interpretive description analysis on qualitative interview transcripts to explore client experiences in a community-based iOAT program in two cities in Alberta, Canada. | Time requirement for engaging in iOAT programs. | Trusting relationships with staff. |

| Krausz (2007) [49] | The author examined the scientific and clinical evidence of iDAM based on the completion of the third major European study, highlighting its effectiveness for target groups not reached by existing OAT modalities and its potential to improve health and social outcomes. | None discussed. | Importance of psychosocial treatment in addition to pharmacological intervention (psychoeducation and case management); Involvement of representatives from cities and states throughout the study; Personal, financial, and structural commitment from involved municipalities; Heroin-assisted treatment as part of a comprehensive strategy for dealing with drug dependence. |

| Lawrence et al. (2000) [50] | The authors analyzed newspaper coverage of DAM prescription spanning two government policy decisions, collecting articles from major Australian newspapers, and examining content, orientation, and subtextual themes used by opponents and proponents to understand the influence on the policy reversal. | Reframing the debate: portrayal of the pilot study, its supporters, and people who use heroin in a way that elicited moral outrage; Conviction that the study would ultimately lead to the legalization of heroin; “Government as a drug dealer.” | Embedding arguments for a trial prescription of iDAM in a broader, coherent vision of drug policy; Portrayal of PWUD in the media: involving families of PWUD who share their stories; Emphasizing the moral responsibility and obligation of the government to all citizens, including individuals with OUD and other affected parties; Highlighting commonalities between OUD and other chronic illnesses. |

| Lintzeris (2009) [51] | The author reviews DAM treatment programs, assessing evidence from trials and cohort studies to evaluate safety, efficacy, and cost-effectiveness, suggesting that DAM treatment offers comparable benefits to methadone treatment but at higher costs. | Higher costs associated with iOAT than optimized oral methadone treatment. | Better outcomes and/or potential cost savings elsewhere (criminal activities, law enforcement). |

| Lintzeris et al. (2006) [52] | The authors describe the methodology for RIOTT, a prospective open-label RCT across England’s supervised injecting clinics, to assess the role of injectable opioids (methadone and heroin) in managing OUD among patients unresponsive to conventional OAT. | None discussed. | Surveying the expectations and satisfaction of study participants; No consideration of “compassionate grounds” for continuing treatment necessary, as injectable Methadone and iDAM are approved and available in the UK. |

| Magel et al. (2024) [53] | The authors conducted semi-structured interviews, email correspondence, focus groups, and regional meetings with iOAT stakeholders to receive feedback on how iOAT can better meet service users’ needs, and employed qualitative analysis to identify key themes. | Current strict limitations on iOAT (dosage, formulation, administration protocols), hindering the provision of more autonomous and individualized care; Providers often feel constrained by these regulations, creating tension between meeting clients’ needs and adhering to system requirements; Misconceptions about the necessity of specialized settings for iOAT; Stringent stipulations aimed at ensuring safety and preventing medication diversion; High-barrier protocols focusing on missed doses, titration, and medication restarts; Tensions arising from balancing client needs, program requirements, and public safety concerns; Resource-intensive and costly implementation of iOAT; Regional contexts necessitate tailored approaches to iOAT implementation, as no single model fits all areas. | Increasing client autonomy in iOAT, including the choice of medication and formulation; Personalized treatment plans to better accommodate individual client needs and preferences; Recognizing the importance of convenience in treatment access (hours of operation, location, environment); Establishing supportive and understanding relationships between clients and healthcare providers; Offering diverse medications (DAM, HDM) and formulations (injectable, oral) to suit distinct client characteristics; Greater fluidity in definitions of retention and engagement; creating inclusive spaces for women, gender-diverse individuals, and indigenous people. |

| Maghsoudi et al. (2020) [54] | The authors explore the current state of policy and practice for DAM and HDM as iOAT options in Canada, highlighting recent changes in accessibility and the need for rapid expansion to address the increasing incidence of fatal opioid overdoses. | Influence of prescription willingness by the fear of problematic use/diversion; Coverage of HDM as an iOAT medication in the required formulation. | Ensuring sustainable funding; Robust assessment approaches for healthcare providers to understand possible problematic use/diversion and collaborative development of ways to expand access and prevent problematic use/diversion. |

| March et al. (2006) [55] | The authors aimed to compare the efficacy of iDAM versus oral methadone, supplemented with medical and psychosocial support, among socially excluded, individuals with OUD for whom standard treatments have failed, using an open, RCT conducted in Granada, Spain. | None discussed. | High-threshold treatment and specific target group as reasons for the absence of the honey-pot effect; Legal and social support, psychiatric, psychotherapeutic, and medical treatments for co-occurring conditions of study participants. |

| March et al. (2004) [56] | The authors conducted an open, RCT in Granada, Spain, comparing the efficacy of iDAM plus oral methadone versus oral methadone alone among socially excluded, individuals with OUD, with outcomes including physical health, HIV risk behaviour, street heroin use, and involvement in crime. | Scepsis and reluctance in potential participants until first dose was administered; Prioritization of immediate reinforcement by potential participants posed challenges for trial engagement, emphasizing the need for “immediate rewards” to facilitate participation. | Incorporation of peers, aiding communication and contact with the target population; Knowledge of potential participant locations and individual recruitment efforts; Social and legal support providing additional assistance beyond the trial; Informing about harm reduction, and offering alternative services. |

| Marchand et al. (2020) [57] | The authors employed a qualitative design to explore participants’ experiences in iOAT with a focus on patient-centred care, conducting in-depth interviews and employing a constructivist grounded theory approach to analyze the data. | None discussed. | Therapeutic relationships for shared decision-making and personalized holistic care. |

| Mayer et al. (2020) [58] | The authors employed qualitative methods, including interviews and ethnographic fieldwork, to explore individuals’ motivations for accessing iHDM and iDAM treatment in the context of Canada’s overdose crisis and structural factors shaping treatment delivery. | None discussed. | Acknowledging structural weaknesses and negative experiences with conventional treatment modalities as the main motivation for iOAT. |

| Mayer et al. (2023) [59] | The authors conducted semi-structured qualitative interviews and ethnographic observations with women enrolled in iOAT programs in Vancouver, Canada to capture women’s perceptions of drug treatment generally, previous experiences accessing treatment before iOAT, and experiences with iOAT. | Lack of privacy and the requirement for daily attendance; Crowded treatment environments and programs’ inability to accommodate women’s social contexts (e.g., childcare, employment); Routine daily attendance and injection time limits; Lack of gender-attentive services; Lack of flexibility in iOAT dosing (e.g., take-home doses). | Building affirming and supportive relationships with iOAT care providers that contribute to women’s engagement and sense of support within the program; Women’s involvement in iOAT programs together with intimate partners to facilitate treatment access and engagement (shared goals); Emphasis on patient-centered care, responsive to clients’ goals and needs. |

| McNair et al. (2023) [60] | The systematic review included studies that evaluated supervised iDAM, and included illegal drug use and/or health as a primary outcome measure to explore questions related to the design and implementation of iDAM in addition to its effects. | Fears of HAT having a ‘honeypot effect’ and negatively impacting community safety influences local and national governments’ interest in and ability to fund and deliver iOAT; Use of DAM in research and clinical settings must be legalised prior to the implementation of iOAT programmes; Pushback from the local community and high start-up costs related to recruitment, staffing, and health and safety. | None discussed. |

| Meyer et al. (2023) [61] | The authors provide an overview of the initial situation in Austria and reasons for the current pilot study on iOAT with HDM in Vienna, highlighting its potential to reduce harm, attract patients, and respond to emerging challenges like the increase in high-potency opioid use. | Prevailing belief in the adequacy of prescribing oral OAT medications for successful OAT; Heightened security concerns regarding potential diversion of HDM or DAM into the black market, necessitating costly security measures and prompting unjustified transitions of patients from oral to iOAT; Public costs and stigma against opioid-dependent patients and OAT-prescribing physicians. | Well-organized treatment system with comprehensive psychosocial services and centralized monitoring through an OAT registry. |

| Oviedo-Joekes et al. (2010) [62] | This pilot study, utilizing data from the NAOMI study, compared the treatment response of iDAM to iHDM in individuals with long-term OUD over a 12-month period. | Stigmatization of medically prescribed heroin use, which can limit acceptance in many settings. | Consistent messages and information about the study in the media, informational materials, and within the team; Targeted yet uniform information for participants and healthcare providers; Supportive approach to study participants and understanding of their “daily struggles”. |

| Oviedo-Joekes et al. (2015) [63] | The authors describe the methodology and recruitment strategies used in the SALOME study, which aimed to enrol individuals with chronic OUD in Vancouver, Canada, for a phase III trial comparing the effectiveness of iHDM and iDAM. | Recruitment: very high number of interested individuals; Concerns that patients may interrupt successful treatments to qualify for the study. | Access to basic care services, psychosocial support, and interdisciplinary services for study participants; Formal information sessions with various institutions, creation and distribution of information packages and materials, FAQs; Involvement of the community before and after the recruitment phase and for forming partnerships with key institutions; Consistent messages and information about the study in the media, informational materials, and within the team. |

| Oviedo-Joekes et al. (2023) [64] | The authors conducted semi‑structured qualitative interviews with participants receiving iOAT take‑home doses at a community clinic in Vancouver, Canada. | Regulatory barriers and clinic constraints hinder program expansion and limit client numbers; System-level concerns regarding medication diversion and safety risks during transportation. | Take-home doses address access barriers and promote equity in treatment by reducing the burden of frequent clinic visits; Client autonomy and shared decision-making in addiction care; Policies and regulations that empower prescribers to provide person-centred care. |

| Poulter et al. (2024) [65] | The case report details the outcomes of the Middlesbrough iOAT service using quantitative data from individuals who had engaged with the service in its first year of operation. | Funding insecurity due to political changes; Local policy changes and limited resources; Need for strategic funding allocation and support from policymakers. | Proactive approach to ensure sustainable funding for iOAT services, potentially through ringfenced funding or capacity building initiatives; Sharing best practices and lessons learned to inform future implementation. |

| Riley et al. (2023) [66] | The authors conducted interviews with service providers and users of the Middlesbrough iDAM service to detail the experiences of individuals with OUD accessing iDAM. | Funding insecurity; Ethical questions about discontinuing established medical care for vulnerable individuals; Twice-daily, clinic-based supervised injections restrict participants’ daily movements, limiting choice, autonomy, and freedom; Unwanted contact with individuals active in the illicit drug market when co-located within an existing drug treatment service. | Long-term or permanent funding for iOAT programs; Building trust with individuals through peer support and ‘treatment champions’; Both harm reduction and abstinence-focused treatment goals; Sense of community and support within the clinic environment; Flexibility in treatment delivery protocols (e.g., providing take-home doses for stable service users). |

| Springer (2007) [67] | The author conducted a review of clinical studies and policy initiatives across multiple countries to explore the introduction and expansion of iDAM as an evidence-based approach for individuals with OUD, aligning with harm reduction measures outlined in the European Drug Action Plan. | None discussed. | Demand for an adequate legal framework for treatment attempts or the establishment of a standardized method; Registration of DAM as a medication and the position of international drug control as central questions for planning the future use of iDAM; Application for European approval of DAM as a drug and especially for use in OAT as a practical approach. |

| Steel et al. (2017) [68] | The authors employ a combination of ethical analysis and argumentation supported by references to established ethical principles and literature. | Challenges for research ethics regarding voluntary consent in clinical research on supervised iOAT; Systemic issues of inequity in access to iOAT as a medical treatment. | Challenging the assumption that difficulties in obtaining voluntary consent stem from the incompetence of individuals with OUD; Drawing parallels with bioethics literature on nonexploitation in clinical research in developing countries to inform ethical approaches in supervised iOAT research. |

| Uchtenhagen (2010) [69] | The author analyzed a collection of relevant documents to describe the process and results of Switzerland’s national policy change, including the introduction of iDAM. | Resistance from many sides; Overflow of arguments against DAM prescription also onto established harm reduction measures; Anticipation and avoidance of unwanted side effects and claims: “Drug tourism,” diversion of prescribed DAM to the illegal drug market, multiple prescriptions, accidents under the influence of prescribed DAM, constant dose increases, prevention of abstinence/recovery, improvement of the image of heroin, alternative treatments no longer acceptable or neglected. | Inclusion of all key political and professional actors in national drug policy conferences; Public availability of trustworthy information about process and outcome data; Collection, analysis, and publication of a variety of process and outcome data and other findings from (inter)national studies as evidence for professional and public debates; Federal democratic structures simplify the integration of drug policy discussions into a process of political and professional debate with active participation of all stakeholders, including the media. |

| van den Brink et al. (1999) [70] | The authors provide an overview of the epidemiology of heroin addiction in the Netherlands, outline the history of the debate surrounding DAM prescription, and describe the ongoing RCT investigating the effectiveness of co-prescribed iDAM, drawing on experiences from Switzerland. | None discussed. | Positive reports from CH as the cornerstone for initiating the study; Intensive exchange of ideas and experiences with the Swiss study team. |

| Wodak (1997) [71] | The author outlines the failed attempt to conduct an iDAM trial in Australia, detailing the decision-making process and the political interference that led to its termination. | None discussed. | “Without such a study… we will never know if it is effective or not. As long as it is not tried, it is very difficult to move forward or consider alternative strategies.” |

| ZIS (2006) [72] | The report summarizes the findings of the German nationwide model project on iDAM, a multicentre RCT with over 1,000 participants. | None discussed. | Formation of local working groups at the regional level, with representatives from relevant local institutions to ensure maximum acceptance and practical implementation; Close cooperation and coordination with local scientific institutes and external monitoring; Establishment of a scientific advisory board with national and international experts due to the high scientific importance and expected attention from a critical (professional) public; Binding cooperation with the Ministry of Health, involved cities and states, as well as organization and supervision of the entire process; Additional conduct of special studies on criminological, program-related (health economics, implementation, cooperation), cognitive-motor and neuropsychological issues, and internal evaluation of psychosocial care within the framework of the pilot project. |

GP general practitioner, iDAM injectable diacetylmorphine, iHDM injectable hydromorphone, OAT opioid agonist treatment, iOAT injectable opioid agonist treatment, OUD opioid use disorder, PWUD people who use drugs, PWID people who inject drugs, RCT randomized controlled trial

Table 4.

Summary of barriers and facilitators across key themes

| Theme | Barriers | Facilitators |

|---|---|---|

| Public acceptance |

− Public safety concerns (e.g., influx of PWUD, visibility of ‘scene’) − Concerns about crime, “Honey-Pot effect” − Increased demand for drug services − Stigma surrounding injection drug use − Promotion of permissive drug use attitudes |

− Strict residency criteria for participants − Limited number of participants − Collaboration with local law enforcement − High-threshold treatment programs − Comprehensive drug policy frameworks (e.g., Switzerland) − Development of infrastructure and security measures |

| Legal and ethical considerations |

− Legal barriers to prescription (prohibition of DAM for iOAT in most countries) − Stringent legal and regulatory requirements (dosage, formulation, administration) − Ethical concerns about patient consent and transitioning back to oral OAT − Tension between client needs and system requirements |

− Changes in laws to allow DAM prescription − National ethics committees ensuring compliance with consent, autonomy, and protection protocols − Methodological standards imposed by ethics committees − Frameworks to reconcile patient autonomy with public acceptance concerns |

| Media coverage and interest groups |

− Negative media campaigns (e.g., defamation, misinformation) − Public fears over “drug tourism” and stigma around heroin use − Moral outrage in public discourse − Resistance from abstinence advocates and political groups |

− Comprehensive information strategies (e.g., publishing reports, organizing events) − Involvement of family members of people with an OUD and community in media strategies − Addressing opponents’ arguments proactively − Emphasizing moral responsibility and public health advocacy |

| Long-term implementation costs and benefits |

− High start-up costs (staffing, recruitment, infrastructure) − Limited long-term economic justification for iOAT − Structural challenges (space, equipment) − Limited resources and political decisions affecting sustainability |

− Demonstrated cost-effectiveness of iOAT (reduced crime, law enforcement costs) − Political support for long-term funding − Economic evaluations − Funding strategies, ringfenced funding, and capacity-building initiatives |

| Patients’ and providers’ perspectives |

− Structural weaknesses in conventional treatment − Regulatory barriers (e.g., daily supervision, dose restrictions) − Reluctance among PWID to switch to iOAT − Concerns about infection risks and attachment to oral OAT rituals |

− Patient-centered care (e.g., incorporating patient preferences in treatment decisions) − Flexibility in delivery protocols (e.g., take-home doses) − Peer support networks to engage harder-to-reach individuals − Inclusive spaces for women and gender-specific services − Interdisciplinary support |

OAT opioid agonist treatment, iOAT injectable opioid agonist treatment, OUD opioid use disorder, PWUD people who use drugs, PWID people who inject drugs

Public acceptance

In the included studies, concerns regarding public acceptance and the potential diversion of study medications or sending “wrong signals” were frequently expressed. This manifested particularly in concerns about the influx of people who use drugs into the study city (the so-called Honey-Pot effect), an increased visibility of the ’scene‘, and the promotion of a more permissive attitude toward illegal drug use, especially among young people. Additionally, there were apprehensions about an increase in crime, hindered law enforcement due to the study setting, and paradoxically, an increased demand for drug-related and other health and social services [30–32, 46, 60, 61, 64]. To minimize concerns about the Honey-Pot effect, the Australian Feasibility Study formulated strict residency criteria and limited the number of participants. Additionally, close collaboration with local law enforcement was established [30]. March et al. [55] attribute the absence of the Honey-Pot effect in Canadian study cities to the high-threshold treatment and the specific target group. The included Canadian studies also describe the specific requirements of the Canadian Ministry of Health concerning the facility’s infrastructure and extensive security measures. These include the development of a dedicated system for logging and monitoring every milligram of heroin from delivery to administration, daily delivery of study medications with an armoured vehicle to study sites, and mandatory security training covering scenarios like hostage situations [46].

Embedding a trial prescription, where medication is provided exclusively within the context of a clinical study, into a comprehensive, coherent vision and strategy of drug policy was deemed essential to achieve the necessary acceptance for this treatment modality [43, 50], all while combatting societal stigma surrounding patients, the substance, and the route of administration by injection [29, 44, 45, 59, 62]. Fox et al. [43] discuss the substantial ideological resistance to adopting iOAT in the context of the US, drawing parallels to the historical controversy surrounding methadone treatment, and despite the devastating North American opioid crisis. Local policy changes and limited resources can jeopardize the sustainability of iOAT services, highlighting the need for strategic funding allocation and support from policymakers [65]. Only in Switzerland was this integration of all relevant political and professional actors achieved within a national drug policy framework [69]. The collection, analysis, and publication of a variety of process and outcome data and other insights from (inter)national studies formed the evidence basis for professional and public debates. Federal democratic structures, such as those in Switzerland, facilitate according to Uchtenhagen [69] the integration of drug policy discussions into a process of political and professional debate with active participation from all stakeholders, including the media. In the Netherlands, positive reports from Switzerland and the recommendation for the study’s implementation by the National Health Council significantly contributed to an approving attitude. Based on this recommendation, the Dutch government decided to conduct the proposed scientific study, which involved an intensive exchange of ideas and experiences with the Swiss study team [37].

To enhance acceptance of study trials within the general population, Bammer [31] advocates for the development and implementation of a comprehensive “information strategy.” This includes publishing current information, press releases, study reports and conference contributions in scientific journals and publicly accessible media, and organising events and seminars related to the study to inform key political decision-makers [31]. Oviedo-Joekes et al. [63] also describe holding formal informational events and creating and distributing informational materials and FAQs during the NAOMI study. Intensive involvement of the community before and after the recruitment phase, along with forming partnerships with key institutions, is considered a facilitating factor [63]. In Germany, establishing a scientific advisory board with national and international experts was considered particularly relevant due to the high scientific significance and expected attention from a critical (professional) public. The sustainability of the German study trial is also supported by the binding cooperation and direct involvement of the German Ministry of Health and the participating cities and federal states in organizing and accompanying the entire process [49]. The high scientific significance of the German pilot project is further justified by additional special studies on criminological, supply-related (health economics, implementation, cooperation), cognitive-motor and neuropsychological issues, as well as the internal evaluation of psychosocial care [72].

Legal and ethical considerations

In all countries covered in the included publications, the initial circumstances were similar; the prescription of DAM for iOAT was prohibited, necessitating adaptation to legal conditions. Studies examined legal and regulatory aspects associated with the planning, conduct, and ultimately the success or failure of (pilot) studies; others specifically reported on ethical considerations. Challenges identified for the introduction of this treatment modality primarily revolve around meeting legal requirements [46, 63] and enacting changes in laws to make DAM available as a medically controlled source of heroin [31, 42, 60, 67, 69]. For established iOAT programs, providers reported that stringent limitations on dosage, formulation, and high-barrier administration and treatment delivery protocols (e.g., supervision, missed doses, titration, medication restarts) create tension between meeting clients’ needs and adhering to system requirements [40, 53, 66]. These stringent stipulations, designed to ensure safety and prevent medication diversion, underscore the need for reconciling public acceptance concerns with increasing patient autonomy in iOAT, including choices in medication and formulation [38, 40, 44, 45, 53, 64, 66].

Regarding the ethical dimensions of this treatment modality at large, several studies within our review highlighted the pivotal role of national, and academic ethics committees in overseeing research endeavours universally. These committees have imposed rigorous methodological standards, ensuring compliance with principles of informed consent, autonomy, and participant protection [32, 36, 49, 67, 72]. However, discussions were described regarding the termination of studies due to medication approval issues, with implications for participants’ treatment continuity [36, 46, 66], as well as considerations regarding the extent to which patients can and should be encouraged to transition to non-intravenous treatment modalities [51, 55, 61]. In light of these concerns, one may question the ethical justification of obtaining voluntary consent from individuals with OUD and of conducting a pilot study if participants may be required to revert to oral OAT should iOAT not receive approval. Steel et al. [68] extensively addressed the topic of voluntary consent in clinical research on supervised iOAT and argue that framing it solely as a question of individual competence overlooks systemic issues of substantial inequity in access to iOAT as a medical treatment. They suggest drawing parallels with bioethics literature on nonexploitation in clinical research in developing countries to inform ethical approaches in supervised iOAT research.

Coverage in the media and interest groups

The significant media interest, negative campaigns, and publicly aired controversies over the prescription of DAM have, in the past, led to the failure of iOAT despite meticulous scientific work. In the case of the planned Australian pilot study, the unsuccessful implementation is largely attributed to an ongoing campaign of defamation and misinformation by the media [50, 71]. Although the Australian Feasibility Study [32] recognized and analyzed the inevitable risk of increased (negative) media interest, it could not resist the “reframing of the debate,” and the decoupling between medically prescribed “heroin” and illegal drugs was not achieved. Based on an analysis of reports in Australian print media, Lawrence et al. [50] describe that in retrospect, the Australian pilot study, its advocates, and people who use opioids were portrayed in a way that elicited moral outrage. Negative campaigns by the tabloid press and letters from abstinence advocates contributed to the widespread belief that the pilot study would ultimately lead to the legalization of heroin, with the “government acting as a drug dealer” [50]. The authors argue that opponents’ claims should not only be refuted but that their arguments must be recognized, even anticipated, and redirected, to dominate public opinion and (political) discourses. Accordingly, a sensitive portrayal of individuals with OUD and the involvement of the families of PWUD in the media or public sphere should have taken place. Additionally, emphasizing the government’s moral responsibility and obligation to all citizens – including individuals dependent on heroin and other affected parties (e.g., victims of property crimes/drug-related crimes) – and highlighting the commonalities between heroin dependence and other chronic illnesses could have been effective strategies [50].

The extensive attention in local, national, and international media, coupled with resistance from various quarters, is also described by Uchtenhagen [69]. Before and during the Swiss pilot studies, false claims, and concerns about potential “drug tourism,” an improvement in the image of heroin, the impossibility of abstinence/recovery, or the diversion of prescribed DAM to the illegal drug market had to be debunked. It was also crucial to anticipate and prevent arguments against heroin prescription from spilling over onto established harm reduction measures [69].

(Long-term) Implementation costs and benefits